Exhibition dates: 9th June – 20th October, 2024

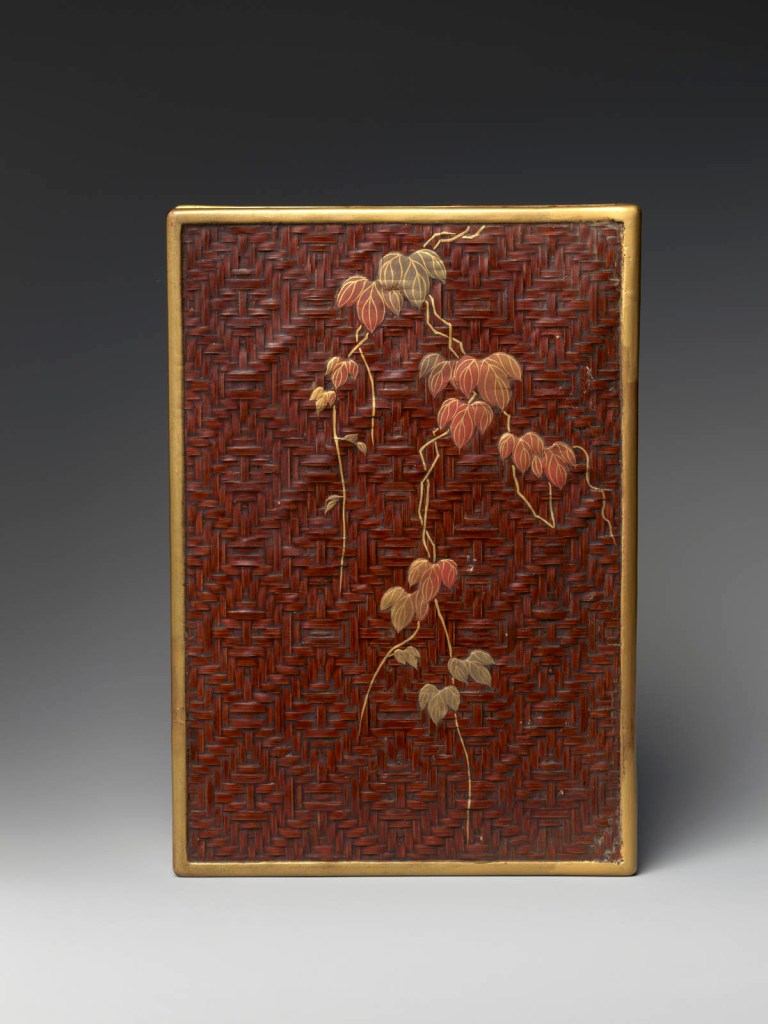

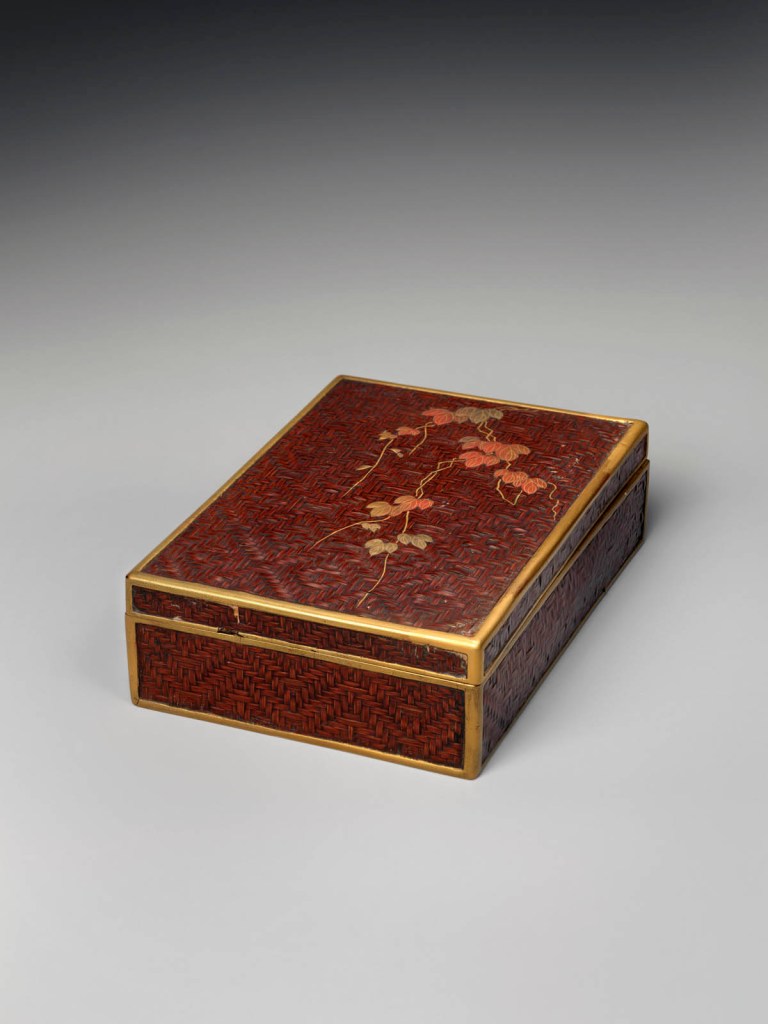

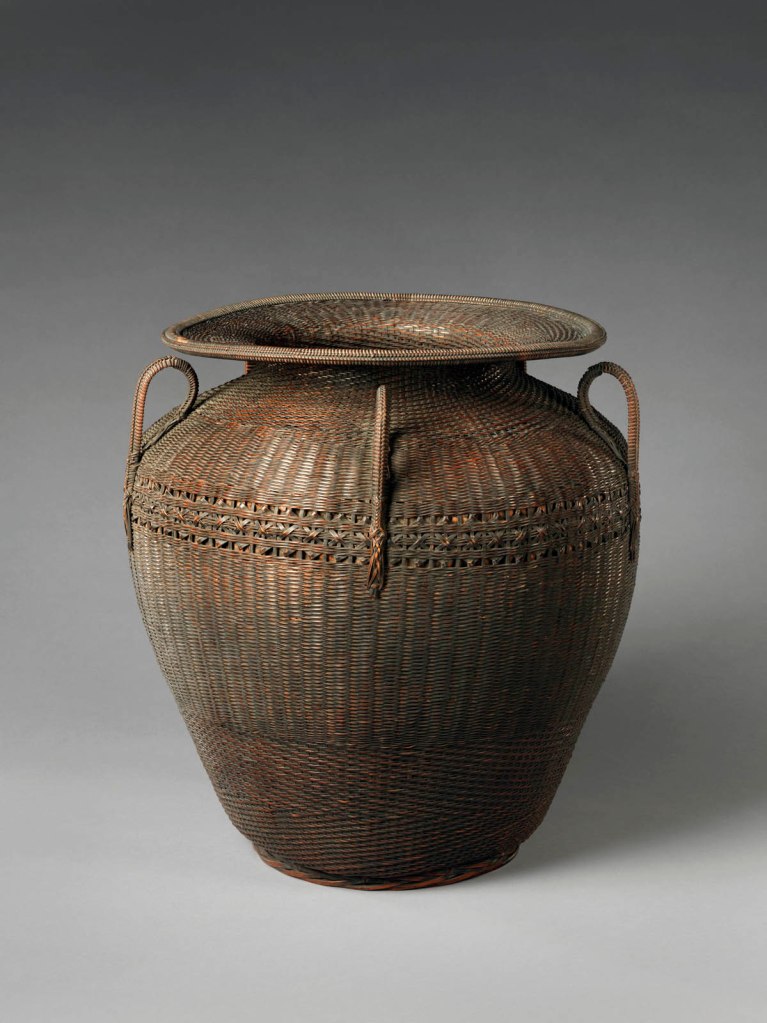

Edo period (1615-1868)

Group of Inrō

18th century

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Inrō are small, light, tightly nested boxes worn hanging from a man’s obi sash, as a Japanese kimono had no pockets. The term’s literal meaning, “seal basket,” probably refers to an early function, but later they held small amounts of medicine. Once they became fashion items, inrō were carefully selected according to the season or occasion and coordinated with the attached ojime (sliding bead) and netsuke (toggle) as well as with the kimono and obi. Moore and his team surely studied the rich motifs and sophisticated production methods of the inrō he collected.

A change of pace this weekend.

Just because… I love beautiful things; I am a collector of antiques and object d’art; and I have a wonderful standing Tiffany picture frame at home.

Roman glass, Italian Murano glass, Austrian and German glass, Arabic and Persian metalwork, glass and earthenware, Japanese lacquer, wicker, metalware and pottery, Chinese glass and porcelain. All used as inspiration by Edward C. Moore, “the creative force who led Tiffany & Co. to unparalleled originality and success during the second half of the 19th century.”

Enjoy!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to The Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. All the text in the posting is from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Exhibition Tour – Collecting Inspiration: Edward C. Moore at Tiffany & Co. | Met Exhibitions

Edward C. Moore (1827-1891) – the creative force who led Tiffany & Co. to unparalleled originality and success during the second half of the 19th century – amassed a vast collection of decorative arts of exceptional quality and in various media, from Greek and Roman glass and Japanese baskets to metalwork from the Islamic world. These objects were a source of inspiration for Moore, a noted silversmith in his own right, and the designers he supervised. The exhibition Collecting Inspiration: Edward C. Moore at Tiffany & Co. will feature more than 180 extraordinary examples from Moore’s personal collection, which was donated to the Museum, alongside 70 magnificent silver objects designed and created at Tiffany & Co. under his direction.

Overview

Edward C. Moore (1827-1891) – the creative force who led Tiffany & Co. to unparalleled originality and success during the second half of the 19th century – amassed a vast collection of decorative arts of exceptional quality and in various media, from Greek and Roman glass and Japanese baskets to metalwork from the Islamic world. These objects were a source of inspiration for Moore, a noted silversmith in his own right, and the designers he supervised. The exhibition Collecting Inspiration: Edward C. Moore at Tiffany & Co. will feature more than 180 extraordinary examples from Moore’s personal collection, which was donated to the Museum, alongside 70 magnificent silver objects designed and created at Tiffany & Co. under his direction. Drawn primarily from the holdings of The Met, the display will also include seldom seen examples from a dozen private and public lenders. A defining figure in the history of American silver, Moore played a pivotal role in shaping the legendary Tiffany design aesthetic and the evolution of The Met’s collection.

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Edward C. Moore (American, New York 1827 – 1891 New York)

Cup

1853

Silver and silver-gilt

3 3/4 x 3 1/4 x 4 3/4 in. (9.5 x 8.3 x 12.1cm); 6 oz. 14 dwt. (208.2 g)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of Jerome B. Dwight, in memory of Charles Noyes de Forest and Henry Wheeler de Forest Jr., 2005

Public domain

This cup is an early example of Moore’s sophisticated design sensibilities and technical skills. While it was first thought to be the work of his father, a recently discovered sketch signed “E. C. M.” confirms the twenty-six-year-old Edward as its designer. Characteristic of his inventive eye and hand are the fluidity of the fuchsia vine and the dynamic play between the high-relief flowers and smooth, undecorated ground, which lend it a compositional coherence and show his understanding of the power of negative space. Engraved as a baby gift for Julia Brasher de Forest, sister of artist Lockwood de Forest, and marked “Moore,” the cup appears to have been a commission he considered a personal project.

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Mustard Pot

c. 1879

Silver, copper, gold, patinated copper-gold alloy, patinated copper-platinum-iron alloy, and niello

3 3/16 × 2 1/2 × 2 in. (8.1 × 6.4 × 5.1cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Friends of the American Wing Fund and Emma and Jay A. Lewis Gift, 2016

Public domain

Following the opening of Japan to the West in the 1850s and the subsequent display of Japanese art at international expositions, the Japanese taste began to captivate American consumers. In response, designers such as Edward C. Moore at New York’s Tiffany & Co. introduced a range of objects inspired by Japanese art works, including ceramics, metalwork, textiles, prints, lacquerware, and netsuke. The decoration on this mustard pot is particularly unusual and innovative. Its baluster form is completely transformed by the asymmetrical inset panels of mixed metal alloys – one of patinated copper and gold (a direct attempt to imitate Japanese Shakudō), and another of patinated copper, platinum, and iron – enclosed by scrolled “Snake Skin” borders. The mottled, multicoloured surface also evokes the swirling array of colours observed in Moore’s collection of ancient mosaic and core-formed glass. Labeled in the Tiffany & Co. Archives as “Mustard to go with Pepper 5493,” this is one of only six decorated versions produced. The Tiffany Archives also retains the Hammering & Inlaying Design drawings for this particular version (#853), which at a cost of $35 was the most expensive iteration.

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Cup and saucer

c. 1881

Silver, patinated copper, patinated copper-platinum-iron alloy, and gold

Cup: 2 1/8 × 2 1/2 × 1 7/8 in. (5.4 × 6.4 × 4.8cm)

Saucer: 1/2 × 4 in. (1.3 × 10.2 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Friends of the American Wing Fund and Emma and Jay A. Lewis Gift, 2016

Public domain

This cup and saucer represent a rare aspect of Tiffany & Co.’s production. As early as 1845 Tiffany & Co. was selling items they promoted as “Indian Goods,” including pipes, belts, pouches, moccasins, and “various fancy articles, made of Birch Bark.” Native American imagery and decorative vocabulary also appeared in Tiffany silver designs, particularly in works conceived by Eugene Soligny (1832-1901) and Paulding Farnham (1859-1927), two of the firm’s leading designers. Here the pattern of alternating red and black triangles is reminiscent of Navajo blankets. During the later decades of the nineteenth century, Tiffany & Co. designers drew inspiration from a diverse array of sources. They had access to the vast collection of books and objects from around the world assembled by the head of the silver division, Edward C. Moore. The decorative pattern on this cup and saucer bears striking similarity to a rendering of floor patterns in one of Moore’s books, The Basilica of San Marco in Venice. Whether referencing Navajo blankets, Venetian floors, or both, the cup and saucer are testaments to the fertile environment in which Tiffany & Co. designers and craftsmen created their innovative work.

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Cup and saucer

c. 1881

Silver, patinated copper, patinated copper-platinum-iron alloy, and gold

Cup: 2 1/8 × 2 1/2 × 1 7/8 in. (5.4 × 6.4 × 4.8cm)

Saucer: 1/2 × 4 in. (1.3 × 10.2 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Friends of the American Wing Fund and Emma and Jay A. Lewis Gift, 2016

Public domain

![Camillo Boito (editor) Ferdinando Ongania (1842-1911) (publisher) 'La Basilica di San Marco in Venezia illustrata nella storia e nell'arte da scrittori veneziani: [volume 3]' 1881 Camillo Boito (editor) Ferdinando Ongania (1842-1911) (publisher) 'La Basilica di San Marco in Venezia illustrata nella storia e nell'arte da scrittori veneziani: [volume 3]' 1881](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/la-basilica-di-san-marco-in-venezia-illustrata.jpg?w=799)

Camillo Boito (editor)

Ferdinando Ongania (1842-1911) (publisher)

La Basilica di San Marco in Venezia illustrata nella storia e nell’arte da scrittori veneziani: [volume 3]

1881

41.3 x 34.1 x 3cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Public domain

Moore assembled an extensive library, which includes a rare, lavish fourteen-volume publication on the Basilica of San Marco in Venice. Produced between 1881 and 1888 under the direction of Italian restoration architect and art historian Camillo Boito, it documents in text and chromolithograph illustrations virtually every detail of the centuries-old basilica. The volume on view here is devoted to the mosaic floors. The image replicates multicoloured geometric patterns from borders that frame some of the floors’ rectangular fields. Their variety and rhythmic energy would have resonated with Moore’s aesthetic sensibilities. Figure IX, in the lower right, bears striking similarities to the Tiffany cup and saucer displayed nearby.

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Two cups and saucers from the Mackay Service

1878

Silver-gilt and enamel

2 1/4 × 2 × 2 3/4 in. (5.7 × 5.1 × 7cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Cranshaw Corporation Gift, 2017

Public domain

These gilded and enamelled cups and saucers are part of one of the most renowned and lavish dinner services ever created in America.

Commissioned in 1877 by John W. (1831-1902) and Marie Louise Hungerford (1843-1928) Mackay, the dinner service for twenty-four consisted of over 1,250 pieces. A poor Irish immigrant with little education, John W. Mackay became one of the wealthiest men in America when he and three partners, James Fair, James Flood, and William O’Brien, struck a silver deposit known as “The Big Bonanza” at Nevada’s Comstock Lode in 1873. During a visit to the mine, Marie Louise asked her husband for a silver dinner service “made by the finest silversmith in the country.” Her husband responded, “You shall have it. I like the notion of eating off silver brought straight from the Comstock.” He proceeded to have a half ton of silver delivered from the mine to Tiffany & Co., where two hundred men worked for almost two years to complete the commission. After being snubbed by New York City society, the Mackays established themselves in Paris. In 1878 the service was sent to be featured in Tiffany’s award-winning display at the Paris Exposition Universelle before being delivered to the Mackay’s home at 9 Rue de Tilsitt near the Arc de Triomphe. In an era of extravagant social affairs, Mrs. Mackay’s dinners and balls were legendary. The Mackay dinner service would have been at the centre of banquets that included royalty, aristocracy, President and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant, and one of the most prominent celebrities of the day, Buffalo Bill. Identified in firm records as “Indian” in style, the Mackay service reflects the sophisticated and innovative design sensibilities of Edward C. Moore, the head of Tiffany’s silver division, and the team of designers, chasers, and craftsmen who conceived and realised this commission. The exquisite cloisonné enamelled decoration on these cups embodies Gilded Age extravagance and would have offered a dazzling finale to a meal served on a sea of elaborately chased silver wares in an “exotic” Indian and Near Eastern taste.

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Two cups and saucers from the Mackay Service

1878

Silver-gilt and enamel

2 1/4 × 2 × 2 3/4 in. (5.7 × 5.1 × 7cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Cranshaw Corporation Gift, 2017

Public domain

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Ice Cream Dish from Mackay Service

1878

Silver, silver gilt

6 × 15 3/8 in. (15.2 × 39.1cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 2023

Public domain

This silver ice cream dish and accompanying plates are part of one of the most renowned and lavish dinner services ever created in America. Commissioned in 1877 by John W. (1831-1902) and Marie Louise Hungerford (1843-1928) Mackay, the dinner service for twenty-four consisted of over 1,250 pieces.

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Ice Cream Dish from Mackay Service

1878

Silver, silver gilt

6 × 15 3/8 in. (15.2 × 39.1cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 2023

Public domain

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Pitcher

1874-1875

Silver

9 3/8 × 7 × 8 3/8 in. (23.8 × 17.8 × 21.3cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sansbury-Mills Fund, 2018

Public domain

This pitcher exemplifies the technical virtuosity and creativity that characterised Tiffany & Co.’s finest silver during the 1870s and 1880s. Under the direction of Edward C. Moore (1827-1891), the silver division at Tiffany & Co. produced a diverse array of exquisitely wrought and highly original work. Created in 1874 or 1875, this pitcher is an early example of Tiffany & Co.’s engagement with Near Eastern and Indian works of art. Edward C. Moore was a passionate and discerning collector of metalwork, glass, ceramics, and textiles from the Islamic world and the Indian subcontinent, and these objects had a profound impact on his creative vision and deigns. The elephant head draped with garlands and the surrounding panels of dahlias, lotus flowers, and other exotic vegetation reflect careful study of Indian and Near Eastern sources and attest to the masterful chasing skills of Eugene Soligny (1832-1901). Together with a matching pitcher that was made several years later, this pitcher was presented in 1883 by Julia Rhinelander (d. 1890) to her niece Mary Rhinelander Stewart (1859-1949) on the occasion of her wedding to Frank Spencer Witherbee (1852-1917).

This pitcher is an especially dynamic and successful example of Tiffany’s engagement with works of art from the Islamic world and the Indian subcontinent. The firm produced numerous versions of this form, most of which feature dahlias and other “Persian” motifs like those seen here. The exquisitely rendered details, particularly the elephant head, attest to the skills of Eugene Soligny, one of Tiffany’s most accomplished chasers. They also reflect ideals promoted by the silver workshop supervisor, Charles Grosjean, who urged careful consideration of the relationship between form and decoration: the pitcher’s curves define the swirling panels of ornament, and the scale and shape of the floral motifs have been carefully calibrated to complement and conform to the undulations.

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Pitcher (detail)

1874-1875

Silver

9 3/8 × 7 × 8 3/8 in. (23.8 × 17.8 × 21.3cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sansbury-Mills Fund, 2018

Public domain

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Charles Osborne (1847-1920) (designer)

Pitcher

c. 1880

Silver

6 × 4 5/8 × 4 1/4 in. (15.2 × 11.7 × 10.8cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Friends of the American Wing Fund and Emma and Jay A. Lewis Gift, 2016

Public domain

Ceramic vessels may have inspired the organic form of this pitcher, which was described in company records as “Pitcher Top thrown over.” Between 1878 and 1889, Tiffany offered variations of it in at least three decorative schemes. The crabs and crayfish scuttling across this version likely owe their lifelike detail to the designers’ careful study of living creatures alongside Japanese objects and books such as Katsushika Hokusai’s Manga. The silversmith Charles Osborne joined Tiffany around the time this pitcher was made, and similar animal forms and spirals appear on many of the designs produced during his collaboration with Moore: see, for example, the chocolate pot on view nearby, which features spirals and identical crayfish castings.

Tiffany & Co. began retailing and producing silver early in its history, quickly establishing itself as the preeminent silversmithing firm in the United States. This pitcher exemplifies the unprecedented innovation and creativity that characterised Tiffany & Co.’s work during the 1870s and 1880s. Under the direction of Edward C. Moore (1827-1891), the silver division at Tiffany & Co. produced a diverse array of exquisitely wrought and highly original silver, which in turn attracted many of the finest craftsmen and designers to the firm. Indeed, Charles Osborne (1847-1920), who is credited with designing this pitcher, left his position as the chief designer at one of Tiffany’s competitors, the Whiting Manufacturing Company, in order to learn from and work with Moore at Tiffany & Co. The silver that resulted from this mentorship and collaboration is among the finest produced during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Vase

1877

Made in New York, New York, United States

Silver

8 1/8 x 4 1/4 x 4 1/4 in. (20.6 x 10.8 x 10.8cm); 14 oz. 19 dwt. (464.5 g)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. H. O. H. Frelinghuysen Gift, 1982

Public domain

Although largely inspired by Japanese art, this group of objects demonstrates that Tiffany’s designers looked to a variety of sources when creating innovative designs. Manufacturing ledgers describe the creamer and sugar bowl as having “Persian Pierced Handles,” while the splayed feet on the vase mimic those seen on a thirteenth-century Iranian brass casket in Moore’s collection. The firm’s staff also devoted significant time to studying the natural world. The silver workshop supervisor, Charles Grosjean, recorded in his diary that he visited the city’s aquarium and also purchased fish from the Fulton Market, which he then had a colleague sketch. This dedication to close observation resulted in the highly accurate depictions of sunfish, pickerel, and yellow perch on the creamer and sugar bowl and Chinese Brama fish on the vase.

The opening of Japan to the West in the 1850s and subsequent displays of Japanese art at world’s fairs inspired great demand for Japanese-style objects in the United States. Edward C. Moore, the director of Tiffany’s silver department, was an early proponent and collector of Japanese art. The decorative motifs on this vase and their asymmetrical arrangement were clearly inspired by Japanese design. Originally, the vase had a lightly pebbled ground and oxidised accents that emulated Japanese metalwork.

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Tray

1879-1880

Silver, copper, brass, gold-copper alloy, and copper-platinum-iron alloy

9 1/8 × 7/8 in., 544.3g (23.2 × 2.2cm, 17.5 oz.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Rogers Fund, 1966

Public domain

Buoyed by the phenomenal success of their Japanese-inspired wares at the 1878 Paris Exposition, Tiffany continued producing innovative designs featuring experimental mixed-metal techniques. A note on the meticulously annotated design drawing for this tray describes the sun or moon as “inlaid red gold, not coloured,” which according to the firm’s technical manual is a combination of “American Gold” and “Fine Copper.” Analysis of the metals reveals that each detail corresponds precisely with the formulas and techniques specified in the drawing. Moore had a particular penchant for objects depicting frogs. Reportedly frogs were kept in an aquarium at the studio for designers to study, so the one leaping and catching mosquitoes here may have been modelled from life.

This lively scene, featuring a frog leaping from the water to catch a mosquito in its open mouth, was part of a series of objects created by Tiffany & Co. in a distinctive Japanese style. The imagery both engraved and rendered in relief was derived from European print sources depicting the arts of Japan and art objects made in Japan collected by Edward C. Moore, head of the silver division and creative director at Tiffany. For example, the swarm of insects depicted on this tray mirrors a small mosquito printed as a page filler in L’Art Japonais, written by Louis Gonse and published in 1883 in Paris. The copy of this publication held in the Thomas J. Watson Library at the Met was Moore’s personal copy, donated in 1891.

Along with his copy of L’Art Japonais, Moore gave his collection of more than five hundred books and two thousand objects, collected from around the world, to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1891. His collection offers ample evidence of his interest in animal imagery, particularly frogs. Indeed, it included many objects depicting frogs and toads, including several small Japanese netsuke. Furthermore, live frogs were kept in the silver studio at Tiffany for designers to study. Rendering this frog from life rather than from a print source likely led to its dynamic pose and sense of movement.

The use of multiple metals and mixed-metal alloys to animate both the frog and rising sun were inspired by Japanese metalwork and Moore’s passion for innovative metalworking techniques and virtuosic craftsmanship. Looking closely at the body of the jumping frog, yellow, pink, and silver coloured metals have been used together to give the appearance of a lifelike, textured amphibian body. XRF (x-ray fluorescence) analysis was used to identify the metals and exact composition of the alloys used on this tray. This analysis, together with Tiffany’s design drawing for this tray and a surviving technical manual – allows for an understanding of what alloys Tiffany used to render certain colours and the shorthand for these mixtures. The rising sun was to be inlaid with “red gold,” determined to be a copper-gold alloy, the frog’s body was to be cast in “Y.M.;” (yellow metal), identified as an alloy of copper and zinc. The designer did not indicate what metal would comprise the pink coloured spots along the frog’s body and legs, but analysis revealed them to be an alloy of copper, platinum, and iron, which is similar to “Metal no, 47,” which the technical manual also describes as Japanese Gold #2 and “Shakado.”

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Charles Osborne (1847-1920) (designer)

Chocolate Pot

1879

Silver, patinated copper, gold, and ivory

11 5/8 × 7 × 5 1/2 in. (29.5 × 17.8 × 14cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Louis and Virginia Clemente Foundation Inc. and Emma and Jay A. Lewis Gifts, 2017

Public domain

The luminous red surface of this vessel, evoking Asian lacquer and ceramic glazes, established a new paradigm for silverwares. Tiffany records indicate that “Chocolate Pot Big Belly” was offered in two versions, the one seen here and another in silver with copper, gold, and “yellow metal” decoration. With a wholesale cost of $175, the copper version was more than twice as expensive to produce. The firm’s technical manual documents the painstaking experimentation undertaken to achieve red surfaces. References to Japanese sources include the inlaid silver pattern on the neck, which resembles the auspicious shippō pattern, as seen in a seventeenth-century incense box earlier in this exhibition, and the applied silver and gold kirimon (paulownia-tree crest), the emblem of the Japanese government.

This chocolate pot exemplifies the unprecedented innovation and creativity that characterised Tiffany & Co.’s work during the 1870s and 80s. Under the direction of Edward C. Moore (1827-1891), Tiffany’s produced exquisitely wrought and highly original silver, which in turn attracted many of the finest craftsmen and designers to the firm. Indeed, Charles Osborne (1847-1920), who is credited with designing this chocolate pot, left his position as chief designer at one of Tiffany’s competitors, the Whiting Manufacturing Company, in order to learn from and work with Moore at Tiffany’s. The silver that resulted from this mentorship and collaboration is among the finest produced during the second half of the nineteenth century. The spiral motifs accenting the pot’s body together with the masterfully chased leaves wrapping the spout are signatures of Osborne’s work. The lifelike cast ornaments of crawfish and crabs further demonstrate technical virtuosity and inventive aesthetic sensibilities, as does the rich red colour, the result of painstaking experimentation and innovative use of electrolytic technology to achieve new surface tones and effects. Moore and Osborne were inspired by Japanese objects; however, their work is in no way imitative. This striking chocolate pot makes clear why The Connoisseur celebrates Tiffany & Co. in an 1885 article entitled “Artistic Silverware” for having “raised the making of artistic silver to a height never reached to my knowledge by silversmiths in preceding ages.”

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Vase

1879

Silver, copper, gold, and silver-copper-zinc alloy

11 1/2 × 6 3/8 in. (29.2 × 16.2cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sansbury-Mills Fund, 2019

Public domain

An accomplished manifestation of Tiffany’s mastery of techniques to redden copper, this bold vase presents an imaginative take on East Asian art and sensibilities. Surviving design drawings reveal that each detail was carefully planned. The seemingly random splatters on the body are all meticulously noted, with an indication that they should be made with fine silver. The trompe-l’oeil effect of cascading liquid spilling over the lip of the vase and down the body references Asian bronzes in Moore’s collection. Charles Grosjean, the workshop supervisor, recorded in his diary, “E. C. M. showed me … a Bronze with ‘drip’ ornament,” which could well be the vase surrounded by waves displayed nearby. Thereafter, Grosjean proudly declared the firm’s designs with drip motifs to be great successes.

This vase exemplifies the creativity and innovation that characterised Tiffany & Co.’s work during the 1870s and 1880s. Under the direction of Edward C. Moore (1827-1891), the silver division at Tiffany & Co. produced a diverse array of exquisitely wrought and highly original work, and this vase is a bold example of their experimentation with novel techniques and Asian-inspired designs. First conceived and created in 1879, this vase was produced both in copper with silver drips, as seen here, and in silver with copper drips. Surviving drawings for the vase reveal that the seemingly random splotches on the red surface and the layered, cascading drips were meticulously planned. Notes on the drawings also specify that the fine gold was to be “inlaid by chasers,” while the copper and green gold ornament was to be “inlaid by battery,” evidence of Tiffany’s progressive engagement with innovative electrolytic processes. Inspired by the colours in Asian ceramics as well as glass and ceramics from the ancient and Islamic worlds that Moore collected and made available to his staff, Tiffany’s craftsmen worked tirelessly to produce coloured surfaces. As one of very few extant examples of Tiffany’s work with red surface treatments and the only significant object currently known that employs drip ornament inspired by Japanese works of art in Moore’s collection (see Japanese bronze vase amid waves), this vase is a rare and important illustration of the firm’s imaginative and technically sophisticated responses to Asian art.

Tiffany & Co. (1837–present)

Pair of Candelabra

1884

Silver

70 1/4 × 22 1/2 in. (178.4 × 57.2cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2024

Public domain

Ideas inspired by the full range of Moore’s collections inform the design of these monumental candelabra. Tiffany records describe the form as “Roman,” and the female figures, paw feet, and baluster-shaped stand all evoke ancient Roman art. Yet the decorative scheme is also manifestly non-Western – the dense floral and vegetal composition enlivening the surface draws on East and West Asian sources as well as close study of natural specimens. Commissioned by Mary J. Morgan, one of Tiffany’s most avid and progressive patrons, these candelabra are the grandest works produced during Moore’s tenure.

These dazzling, monumental candelabra are the most ambitious and virtuosic examples of nineteenth-century American silver known. Created at Tiffany & Co. under the direction of Edward C. Moore (1827-1891), they exemplify the technical and artistic preeminence the firm had achieved by the late nineteenth century. The dynamic decoration that enlivens the almost six-foot high forms incorporates masterfully executed sinuous floral and vegetal ornament, informed by Moore’s extensive collection of works of art from Ancient Greece and Rome, Europe, East Asia, and the Islamic world that Moore’s heirs donated to The Met in 1891. The candelabra were commissioned by one of Tiffany & Co.’s most enthusiastic and progressive patrons, Mary Jane (Sexton) Morgan (1823-1885), wife of railroad, steamship, and iron magnate Charles Morgan (1795-1878). Like Moore, Morgan was an avid collector, and they appear to have been kindred spirits with respect to their passion for Asian art and innovative silver design. Upon her husband’s death, Morgan was reported to have a net worth of over five million dollars, and she set about assembling a significant collection of fine and decorative arts that ranged from paintings by Delacroix to Tiffany silver, European ceramics, and East Asian bronzes, ceramics, lacquerwares, and jades. In an era dominated by men, Morgan was a rare, pioneering collector. The Tiffany silver made for her is among the firm’s most technically and artistically innovative work, suggesting she was a sophisticated connoisseur of silver with an eye for avant-garde designs. Surviving ledger books in the Tiffany & Co. archives indicate 3050 ounces of silver were used to create these candelabra and that the cost associated with producing them was far more than any other works Tiffany had created. After Morgan’s death in 1885, her collection was sold at an auction attended by thousands. At the time, The New York Times reported: “The more the collection is viewed the greater one’s regret that she should have been taken before willing her treasures in a block to some established museum or to one to be established.”

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Designer: Designed by James Horton Whitehouse (1833-1902)

Decorator: Chased by Eugene J. Soligny (1832-1901)

Designer: Medallions by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (American, Dublin 1848–1907 Cornish, New Hampshire)

The Bryant Vase

1876

Silver and gold

33 1/2 x 14 x 11 5/16 in. (85.1 x 35.6 x 28.7cm); Diam. 11 5/16 in. (28.7cm); 452 oz. 16 dwt. (14084.2 g)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of William Cullen Bryant, 1877

Public domain

To honour the poet and newspaper editor William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878) on his eightieth birthday, a group of his friends commissioned “a commemorative Vase of original design and choice workmanship” that would “embody … the lessons of [his] literary and civic career.” Its design, which combines Renaissance Revival sensibilities with those of the Aesthetic movement, consists of a Greek vase form ornamented with symbolic imagery and motifs. The fretwork of American flora covering the body of the vase, including apple branches and blossoms, represents the beauty and wholesome quality of Bryant’s poetry, while the scenes in the oval medallions allude to his life and works. From the moment the commission was announced until well after its completion, the vase was widely publicised and celebrated. After it was presented to Bryant in 1876, Tiffany & Co. displayed it at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The following year, the vase was presented to the Metropolitan Museum, making it the first acquisition of American silver to enter the Museum’s collection.

Manufactured by Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

Designer: Designed by James Horton Whitehouse (1833-1902)

Decorator: Chased by Eugene J. Soligny (1832-1901)

Designer: Medallions by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (American, Dublin 1848–1907 Cornish, New Hampshire)

The Bryant Vase (detail)

1876

Silver and gold

33 1/2 x 14 x 11 5/16 in. (85.1 x 35.6 x 28.7cm); Diam. 11 5/16 in. (28.7cm); 452 oz. 16 dwt. (14084.2 g)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of William Cullen Bryant, 1877

Public domain

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present) (manufacturer)

The Magnolia Vase

1893

Silver, enamel, gold, and opals

Overall: 30 7/8 x 19 1/2 in. (78.4 x 49.5cm); 838 oz. 11 dwt. (26081.6 g)

Foot Diameter: 13 1/2 in. (34.3cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of Mrs. Winthrop Atwill, 1899

Public domain

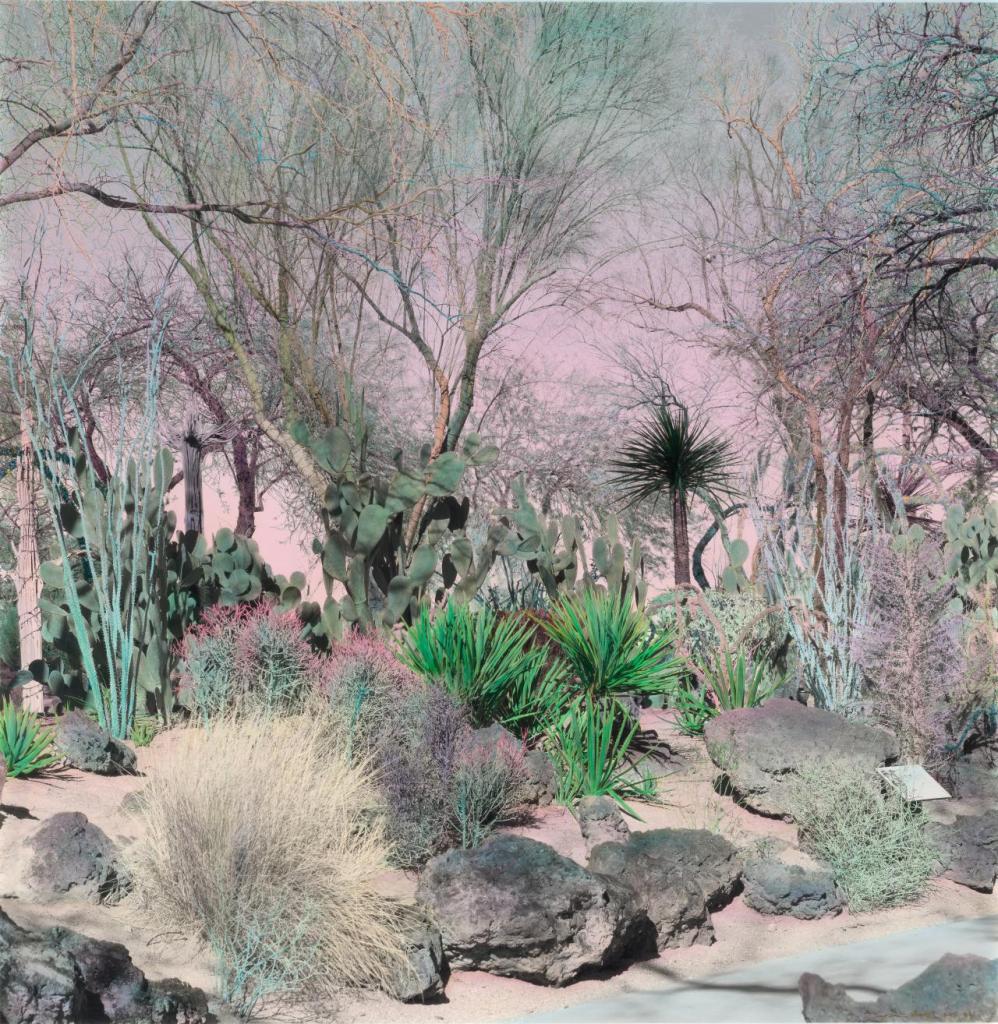

A triumph of enamelling that reflects Moore’s enduring legacy, this commanding vase presided over Tiffany’s celebrated display at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. In keeping with the event’s theme, the anniversary of Columbus’s voyage, Tiffany touted the work’s “American” materials and design. Pueblo pottery was cited as inspiration for the shape, and Toltec or Aztec objects for the handles. The decoration references different regions – pinecones and needles symbolise the North and East, magnolias the South and West, and cacti the Southwest, while the ubiquitous goldenrod unifies the composition. The enamelled blossoms captivated visitors, and one critic declared Tiffany’s display “the greatest exhibit in point of artistic beauty and intrinsic value that any individual firm has ever shown.”

The Magnolia Vase was the centrepiece of Tiffany & Co.’s display at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago – a display Godey’s Magazine described as “the greatest exhibit in point of artistic beauty and intrinsic value, that any individual firm has ever shown.” The design of the vase was a self-conscious expression of national pride. Pueblo pottery inspired the form, while Toltec motifs embellish the handles. The vegetal ornament refers to various regions of the United States: pinecones and needles symbolise the North and East; magnolias, the South and West; and cacti, the Southwest. Representing the country as a whole is the ubiquitous goldenrod, fashioned from gold mined in the United States. The exceptional craftsmanship and innovative techniques manifested in the vase – particularly the naturalism of the enamelled magnolias – were much discussed in the contemporary press. Indeed, the work was heralded by the editor of the New York Sun as “one of the most remarkable specimens of the silversmith … art that has ever been produced anywhere.”

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present) (manufacturer)

The Magnolia Vase (detail)

1893

Silver, enamel, gold, and opals

Overall: 30 7/8 x 19 1/2 in. (78.4 x 49.5cm); 838 oz. 11 dwt. (26081.6 g)

Foot Diameter: 13 1/2 in. (34.3cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of Mrs. Winthrop Atwill, 1899

Public domain

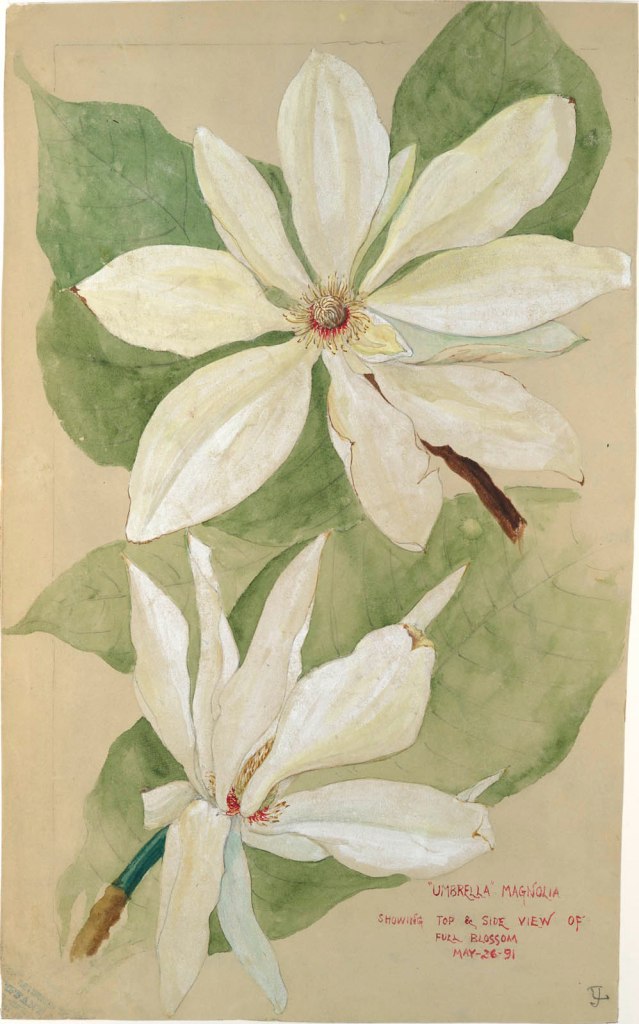

Tiffany & Co. (1837-present)

John T. Curran (1859-1933) (designer)

“Umbrella” Magnolia

1891

Opaque and transparent watercolour, and graphite on paper

Overall: 13 7/8 x 8 5/8 in. (35.2 x 21.9cm)

Design: 13 7/8 x 8 5/8 in. (35.2 x 21.9cm)

Matted: 19 1/4 x 14 1/4 in. (48.9 x 36.2cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of Tiffany & Co., 1985

Public domain

Introduction

Edward C. Moore was the creative force behind the magnificent and inventive silver produced at Tiffany & Co. during the second half of the nineteenth century. His is a tale of phenomenal artistry, ambition, innovation, and vision. In his drive to study and create beauty, Moore sought inspiration in diverse cultures and geographies. He amassed a vast collection of artworks from ancient Greece and Rome, Asia, Europe, and the Islamic world with the aim of educating and sparking creativity among artists and artisans in the United States, particularly those at Tiffany. He believed American design could be transformed through engagement with historical and international exemplars, and his collection not only revolutionised Tiffany’s silver but also came to influence generations of artists and craftspeople.

Moore’s commitment to education led him to designate that his collection be bequeathed to a museum. Upon his death in 1891, his family donated his more than two thousand objects and five hundred books to The Met so that they would continue to be available to all. The Museum displayed the works together in a dedicated gallery until 1942, after which they were dispersed to specialised departments that had developed in the intervening decades.

This exhibition reunites more than 180 works from Moore’s collection, presenting them alongside Tiffany silver created under his direction. The juxtapositions reveal that Moore and his team engaged with these objects in dynamic ways, producing hybrid designs with experimental techniques that endowed silver with new colours, textures, decorative vocabularies, and aesthetic sensibilities.

Early Years

Throughout his career, Edward C. Moore guided the design and manufacture of silver bearing the Tiffany mark. Trained in his family’s New York City silversmithing shop, he proved to be a gifted designer and silversmith at an early age, and in 1849 he joined his father in the partnership John C. Moore and Son. Two years later, Tiffany, Young & Ellis, the firm that would later become Tiffany & Co., secured an agreement to be the sole retail outlet for Moore silver. Edward soon took charge of the family business and served as Tiffany’s exclusive supplier; later, in 1868, his silver manufactory was transferred to Tiffany & Co. in exchange for cash and shares in the newly incorporated company.

Moore’s position afforded him opportunities to travel and access to social and artistic circles that informed his collecting. His holdings became integral to the training and working methods of Tiffany designers and silversmiths; he set up a design room where a vast array of objects and an extensive library were made available to apprentices and staff. He created a collaborative work environment, and each exquisite piece reflects the contributions of many individuals. Their work soon attracted international attention, receiving awards and accolades at world’s fairs and enjoying avid patronage in the United States and around the globe.

Tiffany silver and Greek and Roman Art

Throughout the nineteenth century, Western collectors were captivated by the art of ancient Greece and Rome. Moore amassed an impressive assemblage of Greek and Roman glass vessels and fragments as well as terracotta vases, jugs, and lamps. Much of the silver produced under his direction reflects classical sources, as seen in the symmetrical forms, figural compositions inspired by black- and red-figure Greek vases, and distinctive decorative vocabulary such as helmets, shields, and stylised plant motifs.

Moore embraced the trend of collecting ancient glass; of the approximately 650 classical objects he left to The Met, 618 of them are glass. Spanning a range of manufacturing techniques from the late sixth century BCE through the sixth century CE, the exceptional collection features core-formed, cast, blown, and mold-blown vessels and fragments. Their lustrous surfaces and rich colours fuelled Moore’s experiments with mixed metal compositions and surface treatments for silver. Although Moore and his team were on the vanguard of looking beyond the canon that had defined Euro-American art for centuries – exploring more progressive and non-Western styles – Greek and Roman art remained foundational for Tiffany designers, and classically inspired silver continued to be a mainstay of the company’s production.

Tiffany silver and European Glass

Moore had a particular passion for glass. While his collection features a broad range of art forms, the modern European works are primarily glass. The selection on view here, drawn from the larger group of 116, conveys Moore’s fascination with the variety of colours and forms that could be realised through different glass working techniques.

Ranging in date from the 1500s to the mid-nineteenth century, Moore’s European glass collection is particularly strong in Venetian and façon de Venise (Venetian style) objects. The revival of the Venetian glass industry in the 1860s aligned with his own interest in invigorating contemporary design and artistic practice. He was clearly drawn to the dynamic hot-working techniques that exploited glass’s molten state to create new forms, integrate colours, and shape energetic decorative details. While some direct parallels in vessel shape and decoration exist between the glass and the silver produced at Tiffany, this part of the collection appears to have offered inspiration on a more abstract, visceral level, encouraging Moore and his designers to transcend silver’s traditionally monochromatic palette with the use of enamels, mixed metals, and tonal surface treatments.

Tiffany silver and Arts of the Islamic World

A pioneering American collector of art from the Islamic world, Moore created designs inspired by Islamic sources from his earliest days at Tiffany. He began acquiring outstanding examples of Islamic ceramics, glass, textiles, jewellery, and metalwork at a time when there was neither a U.S. market for this art nor notable domestic interest in it. His bequest of approximately four hundred works from Islamic lands remains the largest and most comprehensive collection of material of this type to have entered The Met.

This gallery reflects the quality and diversity of the objects he collected, marked by a chronological and geographic scope that ranges from the 1100s to the 1800s and from Spain to the Middle East and India. Sinuous forms, brilliant colours, and interlaced motifs appealed to Moore and reinvigorated Tiffany’s designs with new sensibilities and artistic vocabularies. The mixed-metal wares in Moore’s collection inspired experiments with what Tiffany called “chromatically decorated” silver, inlaid with reddish copper and black niello, while the firm’s success with enamelling techniques recalls the colourful enamelled glassware and Iznik ceramics. Inventive designs identified in company records as “Moresque,” “Persian,” and “Saracenic” brought Tiffany new patrons and critical acclaim.

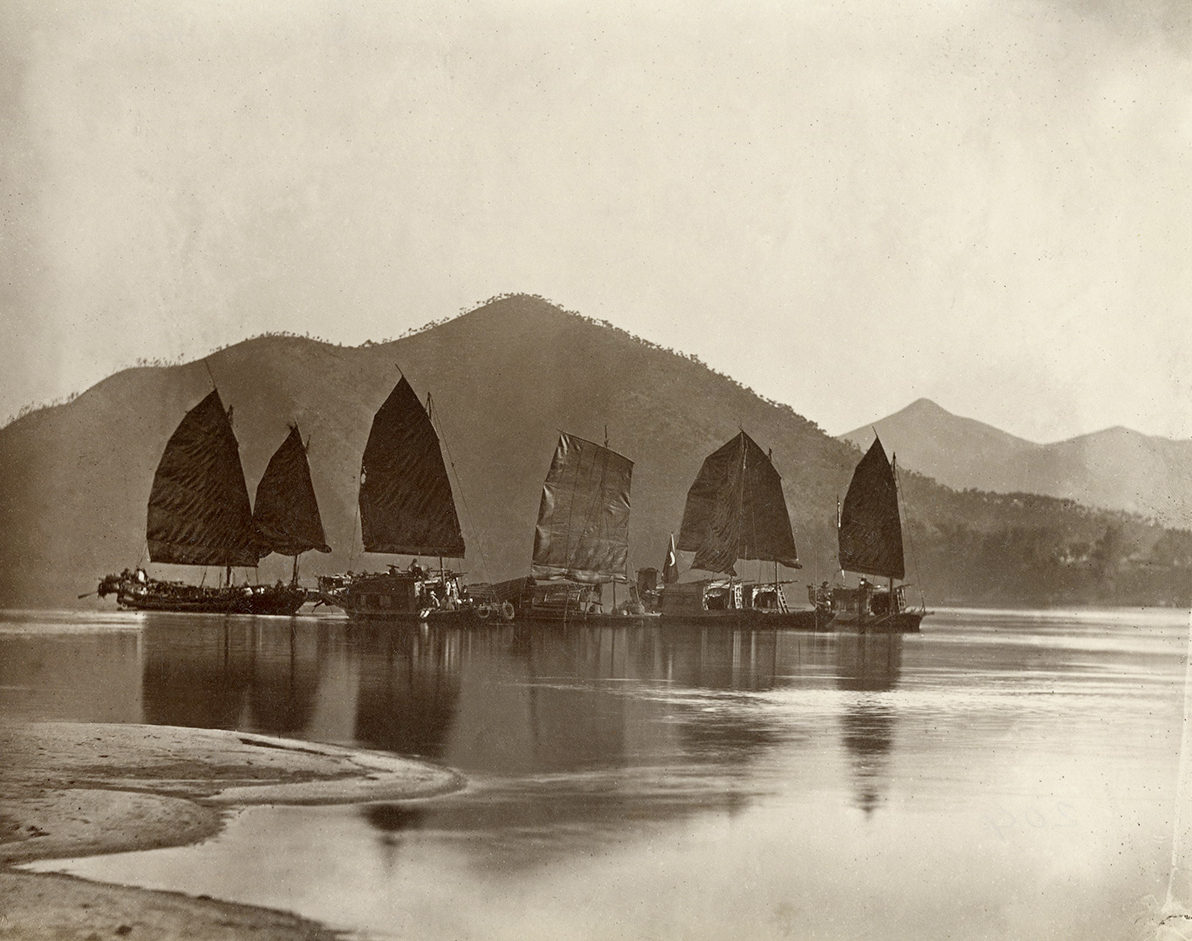

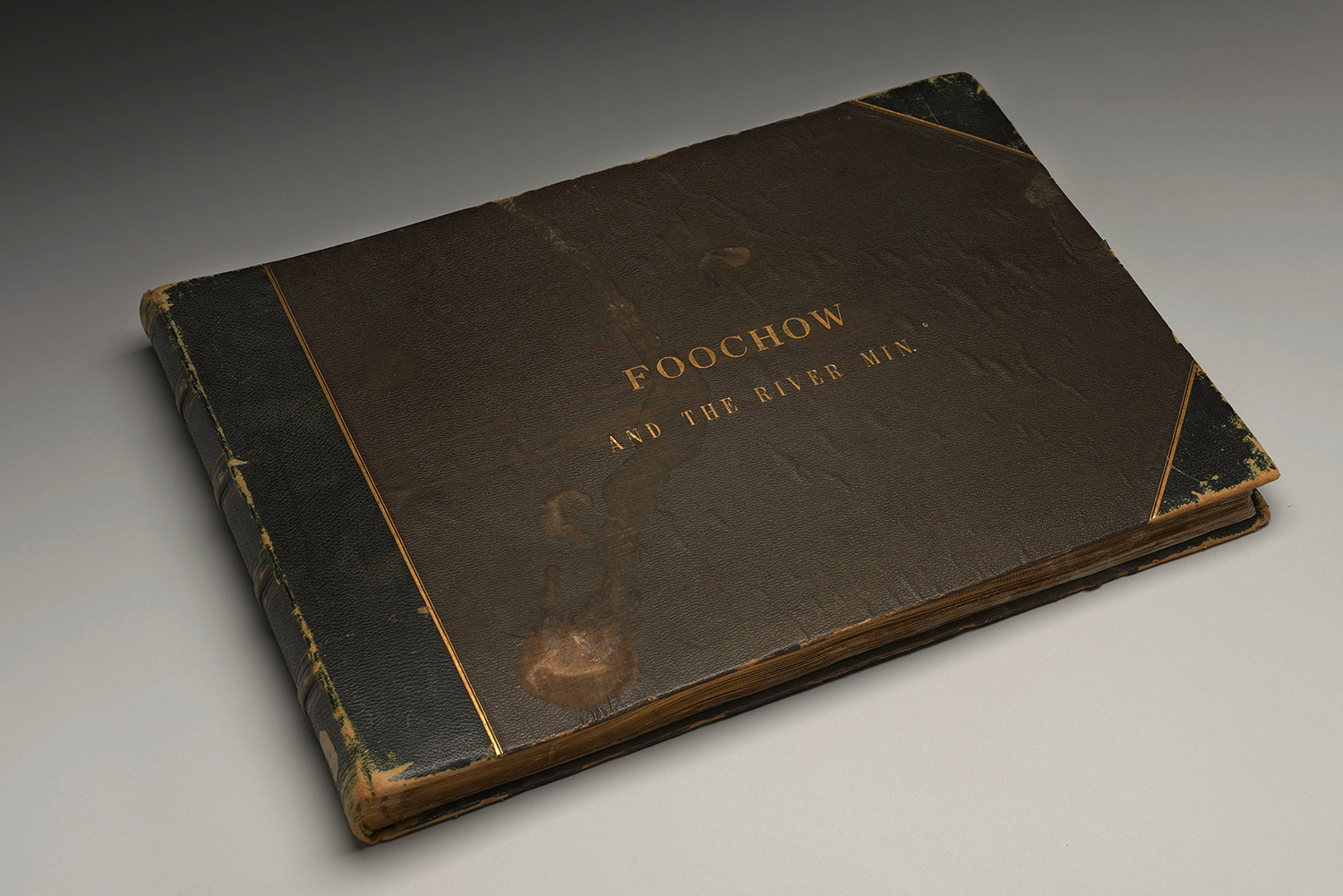

Tiffany silver and Arts of East Asia

The decorative arts of East Asia captured Moore’s imagination and inspired inventive flights of fancy from Tiffany designers and craftspeople. About eight hundred Japanese works of art that he collected are now at The Met, including metalwork, textiles, lacquerware, ceramics, bamboo basketry, and sword fittings, and he gave an equally varied group of more than one hundred Chinese works. A fashion for Japanese art, or “Japanism,” swept through Europe and the United States following the 1854 opening of several ports in Japan for trade with the West, and many regarded Japanese artistic practices as an exemplar for avant-garde design reform. Guided by his desire to spark creativity and innovation, Moore acquired a range of exceptional objects and relatively inexpensive collectibles from the Edo (1615-1868) and Meiji (1868-1912) periods.

Moore and his team carefully studied materials, techniques, decorative vocabularies, and compositions in East Asian art. The related silver designs incorporate novel methods for creating multicoloured alloys and mixed-metal laminates, as well as fresh combinations of imagery – and they made Tiffany an international sensation. One critic wrote in 1878 that the artists’ study of “Japanese forms and styles … has led not to imitation of those models, but to adaptations that have resulted in the creation of a new order of production.”

Legacy

Moore’s legacy of creativity and innovation endured well beyond his death in 1891, as exemplified by the famed Magnolia Vase. Toward the end of his life, he was deeply engaged in planning for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. One of his last designs would be the centrepiece of the Tiffany & Co. exhibit, a grand vase embellished with exquisitely rendered enamelled magnolia blossoms.

A newspaper account heralding the vase and Moore’s role in its design reported, “It is a triumph of the goldsmith’s art to have overcome the difficulty of representing a dull surface by means of enamel.” Moore had long been passionate about perfecting and advancing the art of enamelling, experimenting especially with ways to achieve naturalistic effects with matte enamels. After much trial and error, his staff succeeded in replicating the velvety texture of magnolia petals through the controlled use of fluoric acid fumes. In a remarkable technical feat, they managed to adhere the enamels to an undulating, convex metal surface, while enlivening the design with subtle tonal shifts in the blossoms. Guided by Moore’s protégé and successor John Curran, more than fifteen different craftspeople, including lead enamelist Godfrey Swamby, worked for nearly two years to create a tour de force that fulfilled Moore’s ambitious vision.

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

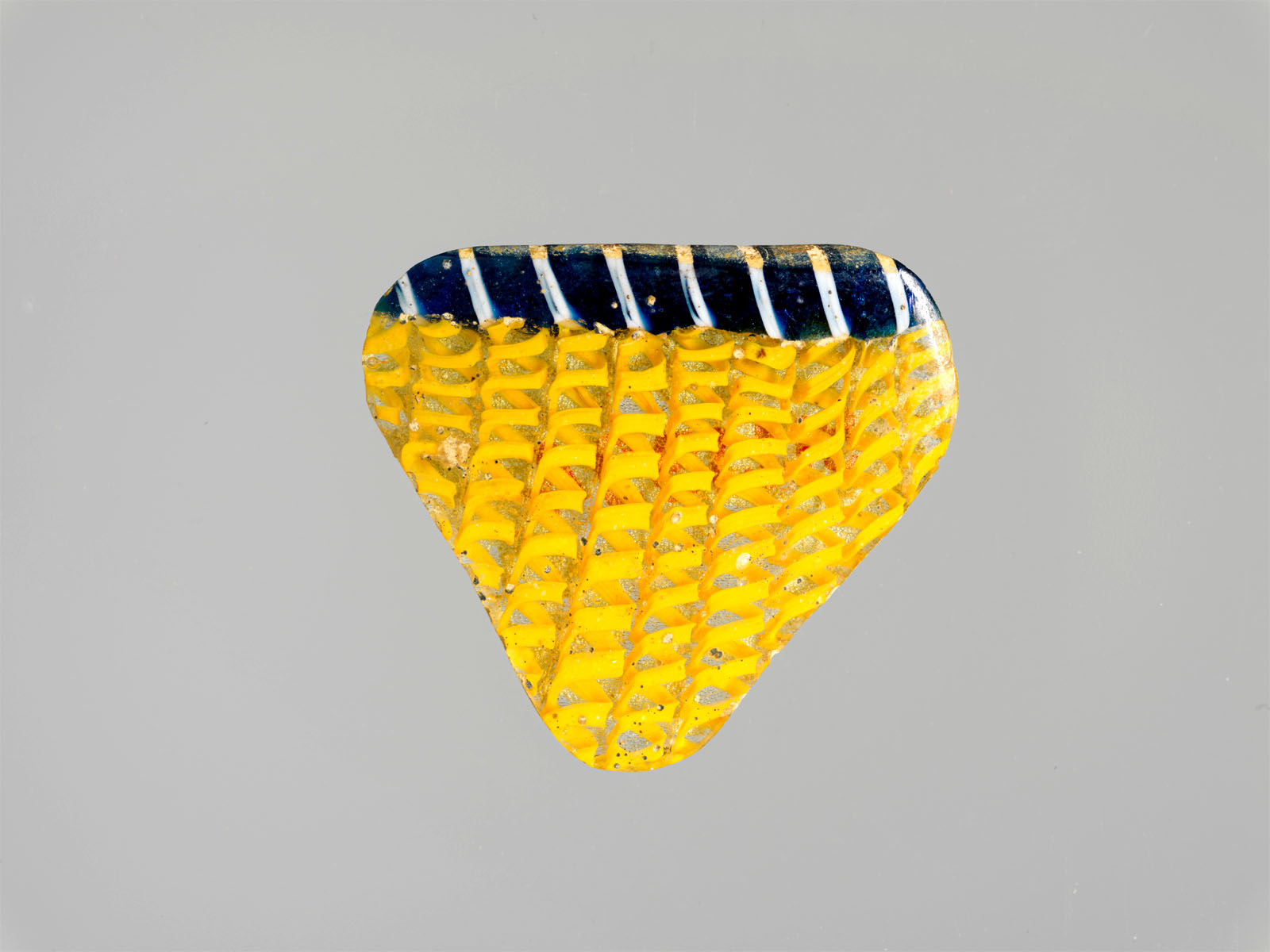

Roman

Fragments of ancient glass

Late 1st century BCE – early 1st century CE

In addition to collecting intact glass vessels, Moore acquired 410 fragments of ancient glass. These fifteen pieces from cast mosaic bowls display a delightful variety of colours, shapes, and techniques. Moore recognised the differences, though he was more likely enticed by the bright patterns and diverse hues than by their technical features. While many of the pieces are small, almost all were repolished to bring out the vibrant colours and motifs.

Glass mosaic ribbed bowl fragment

Period: Early Imperial

Late 1st century BCE – early 1st century CE

Culture: Roman

Glass; cast and tooled

1 15/16 x 1 3/16 in. (4.9 x 3cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Body fragment. Translucent cobalt blue, purple, and opaque white. Convex curving side tapering downward. Marbled mosaic pattern formed from sections of a single cane in blue ground with irregular white and purple threads and streaks; on exterior, vertical rib, tapering and becoming deeper with rounded outer edge. Polished exterior and edge along rib; pitting of surface bubbles on interior; pitting and dulling on interior; some weathering on jagged edges.

Glass mosaic ribbed bowl fragment

Period: Early Imperial

Late 1st century BCE – early 1st century CE

Culture: Roman

Glass; cast and tooled

2 3/8 x 1 7/16 in. (6.1 x 3.7cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Credit Line: Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Body fragment. Translucent honey brown, cobalt blue, and opaque white. Slightly outsplayed neck; straight side tapering downward and curving in at bottom. Ribbon mosaic pattern formed from sections of a single cane in brown ground with irregular wavy white and blue threads in parallel lines; on exterior, two broad vertical ribs, fairly widely spaced, with flattened tops and rounded outer edges. Polished interior; pitting of surface bubbles on interior; dulling and patches of creamy iridescent weathering on exterior; some weathering and chipping of jagged edges.

Glass striped mosaic bowl fragment

Period: Early Imperial

Late 1st century BCE – early 1st century CE

Culture: Roman

Glass; cast

1 9/16 x 1 1/4 in. (4 x 3.2cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Rim fragment. Translucent blue, turquoise blue, purple appearing opaque brick red, yellow, and white, with colourless glass. Applied coil rim with rounded, vertical lip; slightly convex side, curving inward at bottom. Rim in blue with white spiral thread; body decorated with bands slanting slightly from top right to bottom left, forming a pattern: yellow, colourless, yellow, blue with single spiral white thread, blue layered with white, blue, red, yellow, red, blue, blue layered with white, colourless with double spiral yellow threads, turquoise, colourless, and turquoise. Pinprick bubbles; exterior polished, with pitting of surface bubbles; creamy weathering on interior and some iridescent weathering on edges.

Glass mosaic ribbed bowl fragment

Period: Early Imperial

Late 1st century BCE – early 1st century CE

Culture: Roman

Glass; cast and tooled

1 11/16 x 2 3/16 in. (4.2 x 5.5cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Body fragment. Translucent cobalt blue, purple, and opaque white. Slightly outsplayed neck; deep, slightly convex curving side, tapering downward. Composite mosaic pattern formed from polygonal sections of a single cane in a blue ground with a circle of white rods around a white circle surrounding a purple ground with a central white rod; on exterior, two broad vertical ribs, fairly widely spaced, with flattened tops and rounded outer edges, tapering downward. Polished interior; pitting of surface bubbles and iridescent weathering in one chip on interior; dulling and iridescent weathering on exterior and jagged edges.

Glass network mosaic fragment

Period: Early Imperial

late 1st century BCE – early 1st century CE

Culture: Roman

Glass; cast

15/16 x 1 1/16 in. (2.4 x 2.7cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Rim fragment. Translucent blue, opaque yellow, and colourless. Applied coil rim with vertical rounded lip; slightly tapering side. Rim in blue with white spiral thread; body decorated with ten colourless vertical narrow canes, decorated with double spiral yellow threads. Pinprick bubbles; exterior polished, with slight pitting of surface bubbles; dulling and creamy iridescence weathering on interior; jagged, weathered edges.

Glass ribbed bowl and Glass ribbed bottle

1st century CE

Culture: Roman

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Glass ribbed bowl

Period: Early Imperial

Mid-1st century CE

Culture: Roman

Glass; blown, trailed, and tooled

Height: 2 9/16 in. (6.5cm)

Diameter: 3 5/8 in. (9.2cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Translucent deep purple; trail in opaque white. Outsplayed rim, with cracked off and ground lip; short concave neck; broad, globular body curving in to slightly convex and thicker bottom. Thick trail applied on bottom and wound spirally eleven times up side to neck, ending in a large blob; side tooled into fourteen widely-spaced, vertical ribs. Intact, except for one chip in rim, and short sections of trail on body missing through weathering; pinprick bubbles and one glassy inclusion on interior of bottom; some pitting, dulling, and iridescence, with creamy weathering covering most of trail on exterior, little weathering on interior.

Examples of this type of glass bowl are known from many sites across the Roman Empire. Those found in the eastern provinces are generally in pale, almost colourless, transparent glass, but those found in the West are made in rich, deep colours and usually have an opaque white trail decoration.

The ribs on these blown-glass vessels appear on earlier cast-glass versions and were likely added for decorative effect. Ribbed bowls and bottles reveal how shapes and styles of blown glass quickly spread throughout the Roman Empire in the first century CE, as a result of the invention of blowing and demand for glass vessels. The bowl is typical of examples found in Italy and the western provinces, while the rarer bottle has parallels from Cyprus.

Glass ribbed bottle

Period: Early Imperial

1st century CE

Culture: Roman

Glass; blown and tooled

Height: 3 1/2 in. (8.9cm)

Diameter: 3 1/4 in. (8.3cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Translucent blue. Everted rim, folded over and in; cylindrical neck, expanding downwards; pushed-in shoulder; squat, globular body; thick, slightly concave bottom. Twelve, regularly-spaced vertical ribs extending from rim down neck and body, ending above bottom, and forming projecting solid fins on side of body. Intact; pinprick bubbles; pitting, dulling, iridescence, and patches of limy encrustation and brownish weathering.

Glass perfume bottle

Period: Early Imperial

1st century CE

Culture: Roman

Glass; blown

Height: 4 1/4 in. (10.8cm)

Diameter: 2 1/2 in. (6.4cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Translucent purple. Thin, everted rim; slender cylindrical neck, with slightly bulging profile and tooled indent around base; horizontal shoulder, with rounded edge; carinated body, with side to long, upper body tapering downward and lower side curving in sharply; concave bottom. Body intact, but half of rim missing, with weathered edges; some bubbles; severe pitting and brilliant iridescence.

The free-blowing technique developed by the Romans made glass bottles relatively simple and quick to produce. Moore collected some unusual examples of this common type. The brightly striped container, made by fusing together slices of various colours before the bottle was shaped by blowing, resembles cast mosaic glass. The dark iridescent vessel imitates the shape of expensive cast bottles that incorporated gold leaf.

Glass garland bowl

Period: Early Imperial, Augustan

Late 1st century BCE

Culture: Roman

Glass; cast and cut

Height: 1 13/16 in. (4.6cm)

Diameter: 7 1/8 in. (18.1cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Colourless, translucent purple, translucent honey yellow, translucent cobalt blue, opaque yellow, and opaque white. Vertical, angular rim; convex curving side, tapering downwards; base ring and concave bottom.

Four large segments of colourless, purple, yellow, and blue, and applied to the interior of the bowl at the centre of each segment a hanging garland, comprising an inverted V-shaped white string above a U-shaped swag made up of a mosaic pattern formed from polgonal or circular sections of four different composite canes: one in a yellow ground with a white spiral, a second in a purple ground with yellow rods, the third in a colourless ground with white lines radiating from a central yellow rod, and the fourth in a blue ground a white spiral. The four different canes are arranged in pairs side by side but the order in which they are placed differs in each swag. On interior, a single narrow horizontal groove below rim.

Intact, except for one small chip in rim; pinprick and larger bubbles; dulling, pitting of surface bubbles, faint iridescence on interior, and creamy iridescent weathering on exterior.

This cast glass bowl is a tour-de-force of ancient glass production. It comprises four separate slices of translucent glass – purple, yellow, blue, and colourless – of roughly equal size that were pressed together in an open casting mold. Each segment was then decorated with an added strip of millefiori glass representing a garland hanging from an opaque white cord. Very few vessels made of large sections or bands of differently coloured glass are known from antiquity, and this bowl is the only example that combines the technique with millefiori decoration. As such it represents the peak of the glass worker’s skill at producing cast vessels.

With its exceptional workmanship and design, this cast bowl is the most important ancient glass vessel in Moore’s collection. Few vessels with large sections of coloured glass survive from antiquity, and this is the only intact example that combines the technique with mosaic-inlay decoration. Four separate pieces of translucent glass – purple, yellow, blue, and colourless – of roughly equal size were pressed together in an open casting mold. Each segment was then embellished with mosaic glass representing a garland hanging from a white cord. Glass canes (rods) of four different colour combinations arranged in pairs form the individual swags. Bowls decorated with garlands have been found in Italy, Cyprus, and Egypt.

Situla

Early 16th century

Culture: Italian, Venice (Murano)

Glass, enamelled and gilt

Dimensions: confirmed, glass bowl only: 3 13/16 × 8 × 8 in. (9.7 × 20.3 × 20.3cm)

Confirmed, as mounted, handle raised: 10 5/16 × 8 3/4 × 8 in. (26.2 × 22.2 × 20.3cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Influenced by Islamic craftsmen, Venetian glassblowers began making gilt and enamelled vessels as early as the fifteenth century. The decorative scales on this situla resulted from a multi-step process, which entailed reheating the piece a second time after the vessel was blown. The crudely finished handle is most likely not original.

Moore collected several examples of colourful enamelled glass from both the Islamic and Venetian worlds, seeking decorative inspiration for his silver production. Influenced by craftspeople from Islamic lands, Venetian glassblowers started making gilt and enamelled vessels as early as the fifteenth century. The decoration on this situla is the result of a multistep process, which entailed reheating the piece a second time in the furnace. The crudely finished handle is most likely not original.

Footed vase (Vasenpokal)

c. 1570-1590

Culture: Austrian, Innsbruck

Glass; blown, applied mold-blown, impressed, and milled decoration, engraved, cold-painted, and gilded

12 3/4 × 8 1/2 in. (32.4 × 21.6cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

This vase is ambitiously ornamented in the Venetian style with engraved decoration and gold, red, and green cold painting. It also shows key characteristics of pieces from the glassworks that served the Innsbruck court in the late sixteenth century. Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria secured skilled glassworkers and raw materials from Venice, famed for its thin and clear glass known as cristallo. Glass was valued for the technical artistry that transformed humble sand, soda ash, and lime into a nearly weightless, translucent object precious enough to be adorned with gold.

Glassware made outside of Venice but in the same style is known as façon de Venise. This incredibly ambitious Austrian example of a footed vase with engraved decoration and gold, red, and green cold-painting likely came from the Innsbruck court glasshouse of Archduke Ferdinand II. At the time Moore purchased this piece, it had several missing pieces and cracks, which are now restored. The cold-painting is extremely well preserved considering the inherently fragile nature of the technique.

Tankard

1716

Culture: probably South German

Glass; blown, applied and marvered decoration; pewter mount

7 9/16 × 5 1/2 × 4 5/8 in. (19.2 × 14 × 11.7cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

The shape of this tankard, with its bulbous bottom and flared foot, is typical of German pewter and stoneware vessels. The lid features a crudely engraved symbol of what appears to be carpenter’s tools, suggesting that the piece served as a guild vessel, possibly for a carpenters’ association. Its charm derives from the striking contrast between the rough-hewn pewter mounts and the calligraphic trails of white glass decorating the transparent purple glass body.

Beaker

Mid-19th century

Culture: Italian, Venice (Murano)

3 3/8 × 2 5/8 in. (8.6 × 6.7cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

One of the great Venetian innovations in glassblowing is filigrana. Drawn-out canes of colourless, white, and coloured glass were fused together to create the patterned structure of the vessel. Moore had several examples in his collection. This small beaker of more complex canes with multiple spiralling threads, referred to as filigrana a retorti, was made in Venice.

Tray Stand

Mid-14th century (after 1342)

Attributed to Egypt or Syria

Brass; hammered, turned, and chased, inlaid with silver, copper, and black compound

Height: 10 1/4 in. (26 cm)

Diameter: 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Similar stands were widely employed in the Mamluk period to host large rounded metal trays, on which fruits and other food were displayed.

The cup motif inlaid with copper stands out among the richly decoration of this tray. It was a blazon of the cupbearer, one of the differentiated offices of the court of the Mamluk sultans. The inscription reads Husain, son of Qawsun, who was cupbearer to Muhammad b. Qalawun (al-Malik al-Nasir) (1294-1340/41). Despite having been ousted after the sultan’s death, Qawsun’s prestige must have endured, as his sons continued to use his emblem of the ringed cup set within a divided shield.

This work consists of two truncated cones soldered together with a central ring and a flared foot and rim. It belongs to a group of medieval inlaid brass works from the Islamic world that are commonly identified as tray stands, and which supported circular metal platters that displayed and served food. French collectors introduced treasures like this one to the art market in Paris beginning in the 1860-1870s. Moore was likely drawn to them for the visual effects of the inlaid mixed metalwork.

Tray Stand (detail)

Mid-14th century (after 1342)

Brass; hammered, turned, and chased, inlaid with silver, copper, and black compound

Height: 10 1/4 in. (26 cm)

Diameter: 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

‘Umar ibn al-Hajji Jaldak (maker)

Ewer with Inscription, Horsemen, and Vegetal Decoration

Dated 623 AH/1226 CE

Brass; inlaid with silver and black compound

Height: 14 1/2 in. (36.8 cm)

Width: 12 1/16 in. (30.6 cm)

Diameter: 8 3/8 in. (21.3 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

This lavishly decorated object is inscribed around the neck: “Made by ‘Umar ibn al-Hajji Jaldak, the apprentice of Ahmad al-Dhaki al-Naqqash al-Mawsili in the year 623 [1226 A.D.].” Ahmad al-Mawsili, originally from Mosul in Upper Mesopotamia, was a famous metalworker who had a number of pupils.

Moore was particularly interested in lavish works made by mixing and inlaying metals, techniques that artists in the Middle East had developed to a high art centuries earlier for the upper echelons of society. Blending complex geometric and vegetal compositions with fine calligraphy or expressive imagery, they created polychromatic effects comparable to those achieved in painting. The objects here hail from three different Islamic regions around 1100-1400, when the art form flourished.

The ewer is among the earliest dated examples of a prominent school of inlaid metalwork known as “al-Mawsili” (from Mosul) that thrived during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, first in Mosul and later in centres such as Cairo and Damascus. Their work often features thin foils of precious metals inlaid on a gleaming brass body. This example includes detailed scenes of the courtly activities of an ideal ruler and interlacing medallions.

‘Umar ibn al-Hajji Jaldak (maker)

Ewer with Inscription, Horsemen, and Vegetal Decoration (detail)

Dated 623 AH/1226 CE

Brass; inlaid with silver and black compound

Height: 14 1/2 in. (36.8 cm)

Width: 12 1/16 in. (30.6 cm)

Diameter: 8 3/8 in. (21.3 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Inscribed Pen Box

Made in early – late 14th century; altered shortly before mid-15th century

Probably originally from Northern Iraq or Western Iran. Attributed to Afghanistan, probably Herat

Brass; engraved and inlaid with silver, gold, and black compound

Length: 11 1/2 in. (29.2cm)

Height: 2 3/8 in. (6cm)

Width: 2 1/2 in. (6.4cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Luxurious writing tools inlaid with precious metals reflected the literary culture of the upper classes from Cairo to Herat, including a respect for the transmission of knowledge. This pen box with its combination of techniques – filigree in relief on the lid and classical inlay on the body – made a fitting acquisition for a collector with a passion for inlaid metal.

This brass pen box was made in the late fourteenth century but significantly altered by the mid-fifteenth century. The interior decoration of a small-scale pattern of roundels with flying birds and running motifs provides a glimpse into the original decoration of the box. After the exterior surface was burnished to remove this original decoration, new patterns, including a series of interlocking medallions and cartouches and incised lotus blossoms, were set against a cross-hatched background. The inkwell and surrounding insert were added at a yet later date. The inscriptions in thuluth and naskh scripts include poetic verses and good wishes to the owner.

Inscribed Pen Box

Made in early – late 14th century; altered shortly before mid-15th century

Probably originally from Northern Iraq or Western Iran. Attributed to Afghanistan, probably Herat

Brass; engraved and inlaid with silver, gold, and black compound

Length: 11 1/2 in. (29.2cm)

Height: 2 3/8 in. (6cm)

Width: 2 1/2 in. (6.4cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Plate with Vegetal Decoration in a Seven-pointed Star

c. 1655-1680

Made in Iran, Kirman

Stonepaste; polychrome-painted under transparent glaze

H. 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm)

Diam. 18 1/4 in. (46.4cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Moore collected ceramics from Iran, which during the 1870s and 1880s were shipped in great quantities to London, as well as a few pieces from the Ottoman lands (Iznik), Egypt, Syria, and Spain. The large platter from seventeenth-century Kirman, Iran, combines a central star with densely applied Chinese-inspired motifs and colours, features that Moore favoured and incorporated into his own designs.

Dish

c. 1500

Spanish, Valencia

Tin-glazed and luster-painted earthenware

Irregular diameter: 3 1/8 × 18 7/8 in. (7.9 × 47.9cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Moore clearly appreciated lusterware, with its distinctive shiny metallic surfaces. He owned a number of pieces; this dish and other examples from Spain are among the first works he collected. Braseros typically feature radial designs filled with dense patterns, and often present a heraldic emblem – here, a rising eagle, symbol of power and royalty across the Mediterranean.

Tin-glazed earthenware, of which lusterware is one type, was developed in the Middle East in the ninth and tenth centuries to imitate the porcelains produced in China. The opaque white glaze concealed the clay body, which could range from pale buff to brick red, allowing for brilliant effects created by painting the white surface with metal oxides that fired to a range of colours. This technique, as well as the use of metallic luster – an iridescent, coppery painted glaze – spread throughout the Muslim world, arriving among the potters of Valencia in the thirteenth century. The so-called Hispano-Moresque lusterware, with its fusion of Islamic and Gothic styles and motifs, often in shaped imitating those of metal vessels, was treasured by the elite in Spain during the fifteenth century and exported to the courts of Europe. The Valencian industry declined in the late sixteenth century, as colourful Italian Renaissance maiolica gained in popularity among the fashionable and as Spanish centres were founded to produce versions of its pictorial forms. Adding to this decline was the expulsion from Valencia in 1609 of all the remaining Moriscos (Muslims converted to Christianity), though Christian potters reestablished the industry shortly thereafter.

On the front of the dish, Manises lusterware braseros were decorated with radial designs and filled with dense, regularised vegetal motifs and other patterns, all organised around a central device. On the back, they were also luster-painted, usually with larger-scale designs and often with more exuberance. Puncture holes in the rims indicate that such dishes were sometimes displayed on walls when not in use.

Footed Bowl with Eagle Emblem

Mid-13th century

Attributed to probably Syria

Glass; dip-moulded, blown, enamelled, and gilded

Height: 7 3/16 in. (18.3cm)

Maximum Diameter: 8 in. (20.3cm)

Diameter of Base: 5 in. (12.7cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Along with gilded examples, the most treasured glass objects in the Islamic world were enamelled ones. Developed during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in Syria and Egypt under the Ayyubids and Mamluks, they were rediscovered in the 1800s and copied extensively by Western manufactories. When Moore was collecting, this vessel was already celebrated among collectors, dealers, and artists. It was displayed at the 1867 Paris Exposition together with a glass copy by renowned French glassmaker Philippe Joseph Brocard. Moore acquired it from a leading French collector and scholar of Islamic glass, Charles Schefer. After it entered The Met, the bowl was lauded as “the gem of the collection” and “the most beautiful as well as valuable” example of enamelled glass.

Vessels of this characteristic shape, a rounded bowl with a pronounced, tall foot, were sometimes called tazze and were thought to evoke Christian chalices. They became popular in the Islamic eastern Mediterranean during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a period of active exchange between the Islamic and Christian worlds. This piece is among the earliest known examples of enamelled glass. Its ornament and iconography is part of the “courtly cycle” referring to the lifestyle of the rulers and elites of medieval Islamic societies from Egypt to Anatolia.

The design features four circular medallions with a bird of prey. While no particular ruler or officer can be associated with the emblem, such birds of prey were common symbols of power, kingship, and to a certain extent, protection in both Muslim and Christian contexts. Flanking the inscription band and on the foot, rows of dogs chasing hares evoke the hunt, while a frieze of seated musicians and feasting figures replaces part of the inscription. Both the hunt and the feast pertain to the courtly cycle and evoke ideals of kingship.

Footed Bowl with Eagle Emblem (detail)

Mid-13th century

Attributed to probably Syria

Glass; dip-moulded, blown, enamelled, and gilded

Height: 7 3/16 in. (18.3cm)

Maximum Diameter: 8 in. (20.3cm)

Diameter of Base: 5 in. (12.7cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Mosque Lamp

14th century

Probably from Egypt (Cairo) or Syria

Glass; blown, enamelled, and gilded

Height: 12 1/2 in. (31.8cm)

Maximum Diameter: 8 13/16 in. (22.4cm)

Diameter with handles: 9 1/8 in. (23.2 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Enamelled and gilded glass objects from Syria and Egypt are among the most sophisticated crafts created during the Middle Ages. This example has a characteristic shape that was used for portable lamps from Iran to Egypt. During Mamluk rule, enamelled “mosque lamps” were commissioned for many mosques, madrasas (public schools), tombs, and other buildings in the capital city of Cairo. In the nineteenth century, French individuals established in Cairo introduced treasures like these to the European market. Moore was likely intrigued by the lamp’s colours, sheen, and detailed ornamentation.

One of the conventions of Mamluk mosque lamp decoration was to execute one inscription band in blue and the other in reserve against a blue ground. On this lamp, the neck and foot repeat the phrase al‑’alim (“The Wise”), punctuated by an as yet unassigned emblem, while the body bears a formulaic dedicatory inscription but no name.

Swan-Neck Bottle (Ashkdan)

Probably 19th century

Attributed to Iran

Glass; mold-blown, tooled

Height: 15 1/8 in. (38.4 cm)

Maximum Diameter: 4 7/16 in. (11.2cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

During Moore’s lifetime, European and American collectors were particularly drawn to glass made fairly recently in Iran or by the Ottomans at Beykoz in Istanbul. Moore and other collectors purchased many of these readily available and affordable wares and donated them to European and American museums. Moore’s eagerness to explore new shapes is evident in his later glass holdings. He often collected multiple examples of the same type, such as rosewater sprinklers, in different shapes and colours. Many were available for study at his Prince Street manufactory and a few directly inspired his designs.

The variety of forms and colours featured in this selection show the eclectic approach of Iranian glassmakers and their tendency to look both locally and globally for inspiration. The Qajar vessels’ shapes either follow Iranian metal and ceramic models or echo Venetian glass. For instance, the swan-neck bottle mimics Venetian glass, while the gulabpash and the ewer likely inherited their forms from long-standing design traditions in different media.

Two Rosewater Sprinklers

Late 18th – 19th century

Probably from Turkey, Beykoz, Istanbul

Glass; blown

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

Rosewater Sprinkler

Late 18th – 19th century

Probably from Turkey, Beykoz, Istanbul

Glass; blown

Height: 8 3/4 in. (22.2cm)

Width: 3 3/8 in. (8.5cm)

Diameter: 2 3/8 in. (6cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

This bottle is typical of the objects that were displayed in open niches in reception rooms of Ottoman-period upper-class Syrian homes.

During Moore’s lifetime, European and American collectors were particularly drawn to glass made fairly recently in Iran or by the Ottomans at Beykoz in Istanbul. Moore and other collectors purchased many of these readily available and affordable wares and donated them to European and American museums. Moore’s eagerness to explore new shapes is evident in his later glass holdings. He often collected multiple examples of the same type, such as rosewater sprinklers, in different shapes and colours. Many were available for study at his Prince Street manufactory and a few directly inspired his designs.

These two marbled Ottoman sprinklers reveal Moore’s keen eye for nuances in glassmaking techniques and patterns. In one, a mixture of red and brown opaque glass served as the base material, and the spiral marbling was created as the body was blown and turned into its distinctive onion-like form with cylindrical neck. In the other, a hot gather of greenish iridescent glass was rolled in crushed red glass and then blown into the final shape. This led to the patchy marbled pattern on the body that develops into alternating lines on the elongated neck.

Rosewater Sprinkler

Late 18th – 19th century

Probably from Turkey, Beykoz, Istanbul

Glass; blown

Height: 7 3/16 in. (18.2cm)

Maximum Diameter: in. 2 13/16in. (7.2cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

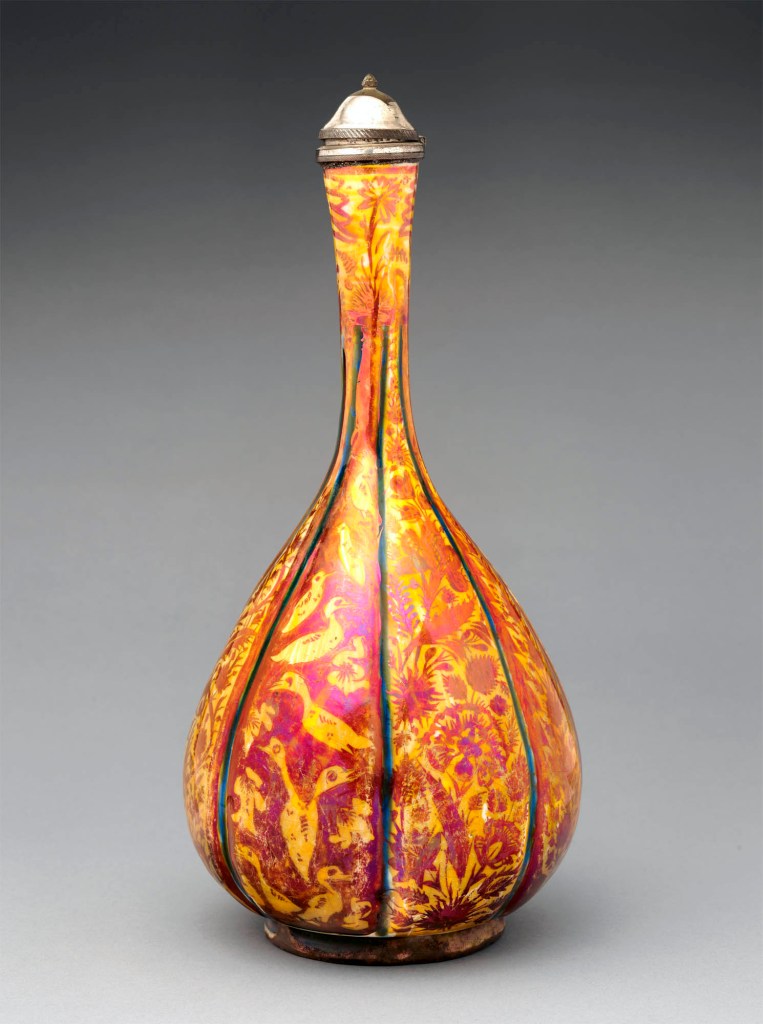

Jar

14th century

Attributed to Syria

Stonepaste; polychrome-painted under transparent glaze

Height: 13 1/4 in. (33.7cm)

Maximum Diameter: 9 1/4 in. (23.5cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

Public domain

This pear-shaped jar is characteristic of medieval ceramics from the eastern Mediterranean. The body is dominated by a cursive inscription wishing “Lasting glory, abundant power, and good fortune.” Messages on utilitarian vessels were intended to protect the owner as well as the contents. The blue-and-white colour palette derives from Chinese porcelain, which Mamluk rulers in Egypt and Syria collected for use during festive and ceremonial occasions or for diplomatic gifts. This jar thus reflects the taste of the elite, adjusted for a broader middle-class market.