Exhibition dates: 30th May – 25th August 2024

Curators: Judy Ditner, Leslie M. Wilson and Matthew S. Witkovsky

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Yaksha Modi, the daughter of Chagan Modi, in her father’s shop before its destruction under the Group Areas Act, 17th Street, Fietas, Johannesburg

1976

From the series Fietas

Gelatin silver print

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised donation of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt writing history

To keep this archive relevant I am constantly refreshing the postings to make sure all the links work, all the videos are still available, and all the bibliographic information about the photographers is up to date.

With the switch to the new template I am having to refresh every page that I have published since 2008 which is a mammoth task. Every time I search the Internet for an artist and their dates I say a little “thank you” when I find an artist is still living… for their creativity and energy is still present in the world. Unfortunately what I have found is that so many photographers have passed away since I started Art Blart in 2008, many within the last 8-10 years.

This is not surprising, people die! But we seem to be loosing that generation of photographers who were born in the 1920s-1940s who actually made a difference to the world and how we live in it. How they viewed the world in their own unique way and used photography to advocate for a fairer world free from war, discrimination and injustice. Photographs making a difference. As Lewis Hine observed, “Photography can light up darkness and expose ignorance.”

I find it very sad that every time a creative person dies you can no longer have a conservation with that person about their passion, their vision, their understanding of the world around them and how they photographed it. All we have left are their photographs, their lived consciousness if you like, as to what was important for them to photograph during their lifetime: family, friends, people, environment, spirit, protest, war, whatever … and what values they held fast to in order to picture the “improvised realities of everyday life.”

We are loosing a generation of photographers.

We are loosing a generation of photographers that captured an image of human existence as a reflection of reality, a truth lived in the world (rather than postmodern fragmentation, posthuman or AI).

At a time when the last fighter pilot who fought in the Battle of Britain in 1940 just turned 105 in July 2024 (Group Captain John Allman Hemingway, DFC, AE – one of the few that saved Britain), a large proportion of the artists listed below were born before or in the shadow of the cultural and ideological conflict that was the global conflagration of the Second World War. The grew up suffering the vicissitudes of war, bombing, death, rationing, deprivations, genocide and mass migration. They grew up knowing of the threat to their freedom and survival. They grew up with a heightened sense of the value of human life and the need to record that humanity. As my friend and photographer Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019) eloquently said:

“We believed we had an obligation, neither social nor political, to make a difference. We were brought up as children to believe that we had an obligation to make that difference.

If we can find out what we are… that is the artist. This goes to the core element of your being, and the core element of your enquiry remains the same.

If the core part of your life is the search for the truth then that becomes a core part of your identity for the rest of your life. It becomes embedded in your soul.”1

I suggest that David Goldblatt was one such artist who was brought up to believe that he had a obligation to make a difference. And it was through the truth of his photographs that he made that difference.

Goldblatt was “the grandson of Lithuanian-Jewish migrants, who left Europe for South Africa in the 1890s to escape religious persecution. Goldblatt was born in the small gold-mining town of Randfontein in 1930 and later lived and worked in Johannesburg.”2

“In 1910 Chinese indentured labourers were repatriated and replaced by migrant black labour, many recruited from neighbouring territories. In 1921-1922 The Rand Rebellion/ Revolt saw white mine workers protest the industry’s attempt to replace semi-skilled white men with cheap black labour leaving about 200 people dead, more than 1,000 injured, 15,000 men out of work and a slump in gold production. The government came under pressure to protect skilled white workers in mining and three Acts were passed that gave employment opportunities to whites and introduced a plan for African segregation. In 1948 apartheid was legislated.”3

During the Second World War, “South Africa made significant contributions to the Allied war effort. Some 135,000 white South Africans fought in the East and North African and Italian campaigns, and 70,000 Blacks and Coloureds served as labourers and transport drivers… The war proved to be an economic stimulant for South Africa, although wartime inflation and lagging wages contributed to social protests and strikes after the end of the war. Driven by reduced imports, the manufacturing and service industries expanded rapidly, and the flow of Blacks to the towns became a flood. By the war’s end, more Blacks than whites lived in the towns. They set up vast squatter camps on the outskirts of the cities and improvised shelters from whatever materials they could find. They also began to flex their political muscles. Blacks boycotted a Witwatersrand bus company that tried to raise fares, they formed trade unions, and in 1946 more than 60,000 Black gold miners went on strike for higher wages and improved living conditions.”4

Goldblatt was a first generation migrant who grew up surrounded by the oppression of blacks in a small gold-mining town. He lived through the Second World War and as a human being and a Jew would know of the atrocities of the concentration camps. He started taking photographs when he was a teenager in the late 1940s after the war ended and just after the beginning of apartheid. All of these events – black oppression, Jewish genocide, and apartheid – would have affected his outlook on life and his values. He is quoted as saying, “Apartheid became very much the central area of my work, but my real preoccupation was with our values … how did we get to be the way we are?”5

How does any human being believe that their values are “right” and more valuable than those of another culture? that then leads them into conflict with other people who have different values? or to a belief that they are superior to another race? Such is the case with white supremacy and apartheid, a word used to describe a racist program of tightened segregation and discrimination.

Early in his career, to get subjects for his photographs, David Goldblatt posted “classified advertisements in local newspapers requesting sitters for his portraits. Goldblatt’s ads for his personal work often included a note of reassurance, one of which gave [this] exhibition its title: “I would like to photograph people in their homes in Johannesburg, Randburg and Sandton. There will be no charge and one free print will be supplied. Further copies at cost price. There is no catch and no ulterior motive.””6

The phrase “no ulterior motive” is part misnomer.

Leslie Wilson and Yechen Zhao have observed that while “Goldblatt’s use of “no ulterior motive” was supposed to allay concerns that he was trying to take advantage of his sitters,” Goldblatt was also fully aware of the use he wanted to put his photographs. “Even as he positioned himself as a photographer without an ulterior motive, Goldblatt certainly had an intention for the resulting photographs: to use them in service of understanding and representing South African social relations.”7

Goldblatt was fully aware, fully attentive and informed about the history his country – “the history of South Africa’s mining industry, white middle class, forced segregation of black and Asian communities into townships under the Group Areas Act” – and he used his photographs to objectively document social conditions in South Africa, photographs which were then published in magazines and books for wider distribution.

Unlike the more overtly activist photographs of the legendary Ernest Cole (which led to Cole fleeing South Africa after the publication of his book House of Bondage in 1967), Goldblatt’s photographs are quieter and more insidious in their criticism of the structures of the apartheid system. Through the quietness of everyday photographs, through the dignity of his subjects and through the elision of violence, Goldblatt subtly chisels away at the foundations of oppression and injustice in South African society. As Susan Aurinko observes, “One might argue that in his own silent way, he was an activist, using his camera to expose things that should never have been allowed to happen.”8

With the waning of a generation of social documentary photographers around the world who wrote history through their photographs, we leave ourselves open and vulnerable to the duplicity and misinformation of current media trends (including the viral promulgation of images).9 Photographs of truth and substance can still make a difference. I repeat the quote from Lewis Hine earlier in this text: “Photography can light up darkness and expose ignorance.”

With the rise of the far right around the contemporary world, the forces of darkness must be opposed; truth and justice must, can and will be upheld. Ignorance is not strength.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Here are some of the artists that I have had to update their details:

Abbas (Iranian, 1944-2018)

John Baldessari (American, 1931-2020)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Richard Benson (American, 1943-2017)

James Bidgood (American, 1933-2022)

Geta Brâtescu (Romanian, 1926-2018)

Anna Blume (German, 1937-2020)

Jimmy Caruso (Canadian, 1926-2021)

Christo (Bulgaria, 1935-2020)

John Cohen (American, 1932-2019)

Joan Colom (Spanish, 1921-2017)

Marie Cosindas (American, 1923-2017)

Barbara Crane (American, 1928-2019)

Bill Cunningham (American, 1929-2016)

Destiny Deacon (Australian, Kuku/Erub/Mer, 1957-2024)

Maggie Diaz (American Australian, 1925-2016)

Elliott Erwitt (American, 1928-2023)

Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019)

Larry Fink (American, 1941-2023)

Robert Frank (Swiss, 1924-2019)

Vittorio Garatti (Italian, 1927-2023)

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Arlene Gottfried (American, 1950-2017)

F. C. Gundlach (German, 1926-2021)

Károly Halász (Hungarian, 1946-2016)

Dave Heath (American, 1931-2016)

Fred Herzog (Canadian born Germany, 1930-2019)

Ken Heyman (American, 1930-2019)

Thomas Hoepker (German, 1936-2024)

Frank Horvat (Italian, 1928-2020)

Hillert Ibbeken (German, 1935-2021)

Vo Anh Khanh (Vietnamese, 1936-2023)

Jean Mohr (Swiss, 1925-2018)

Sigrid Neubert (German, 1927-2018)

Floris Neusüss (German, 1937-2020)

Ranjith Kally (South African, 1925-2017)

Sy Kattelson (American, 1923-2018)

Chris Killip (British, 1946-2020)

William Klein (French born America, 1926-2022)

Karl Lagerfeld (German, 1933-2019)

Rosemary Laing (Australian, 1959-2024)

Ian Lobb (Australian, 1948-2023)

Ulrich Mack (German, 1934-2024)

Mary Ellen Mark (American, 1940-2015)

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Sonia Handelman Meyer (American, 1920-2022)

Santu Mofokeng (South African, 1956-2020)

Floris Neusüss (German, 1937-2020)

Marvin E. Newman (American, 1927-2023)

Terry O’Neill (British, 1938-2019)

Polixeni Papapetrou (Australian, 1960-2018)

Marlo Pascual (American, 1972-2020)

Peter Peryer (New Zealand, 1941-2018)

Marc Riboud (French, 1923-2016)

Robert Rooney (Australian, 1937-2017)

Lucas Samaras (American born Greece, 1936-2024)

Jurgen Schadeberg (South African born Germany, 1931-2020)

Michael Schmidt (German, 1945-2014)

Malick Sidibé (Malian, 1935-2016)

Michael Snow (Canadian, 1928-2023)

Frank Stella (American, 1936-2024)

Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016)

Charles H. “Chuck” Stewart (American, 1927-2017)

Jerry N. Uelsmann (American, 1934-2022)

Bill Viola (American, 1951-2024)

John F Williams (Australian, 1933-2016)

Michael Wolf (German, 1954-2019)

Ida Wyman (American, 1926-2019)

George S. Zimbel (American-Canadian, 1929-2023)

Footnotes

1/ Joyce Evans in conversation with Marcus Bunyan 2019

2/ Anonymous. “David Goldblatt,” on the MCA website October 2018 [Online] Cited 06/08/2024

3/ Anonymous. “Brief History of Gold Mining in South Africa,” on the Mining for Schools website 2022 [Online] Cited 06/08/2024

4/ Alan S. Mabin and Julian R.D. Cobbing. “World War II in South Africa,” on the Britannica website last updated Aug 5, 2024 [Online] Cited 06/08/2024

5/ David Goldblatt quoted in Anonymous. “David Goldblatt,” on the MCA website October 2018 [Online] Cited 06/08/2024

6/ Leslie Wilson and Yechen Zhao. “In the Room with David Goldblatt,” on the Art Institute of Chicago website December 19, 2023 [Online] Cited 11/07/2024

7/ Ibid.,

8/ Susan Aurinko. “Painful Truths: A Review of David Goldblatt at the Art Institute of Chicago,” on the New City Art website December 22, 2023 [Online] Cited 07/07/2024

9/ “… the French philosopher and critic, Paul Virilio, speaking of contemporary images, described them as ‘viral’. He suggests that they communicate by contamination, by infection. In our ‘media’ or ‘information’ society we now have a ‘pure seeing’; a seeing without knowing.”

Paul Virilio. “The Work of Art in the Electronic Age,” in Block No. 14, Autumn, 1988, pp. 4-7 quoted in Roberta McGrath. “Medical Police”, in Ten.8 No. 14, 1984 quoted in Simon Watney and Sunil Gupta. “The Rhetoric of AIDS,” in Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta (eds.,). Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology. London: Rivers Osram Press, 1990, p. 143.

Many thankx to Fundación MAPFRE for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“… the kind of photography that I am interested in is much closer to writing than to painting. Because making a photograph is rather like writing a paragraph or a short piece, and putting together a whole string of photographs is like producing a piece of writing in many ways. There is the possibility of making coherent statements in an interesting, subtle, complex way.”

David Goldblatt

“Apartheid became very much the central area of my work, but my real preoccupation was with our values … how did we get to be the way we are?”

David Goldblatt

“While Goldblatt’s style and method vary from one series to the next, the constant impartiality and benevolence of his gaze are perhaps what best describe his unique approach to social documentary photography at the crossroads with fine art. He never judges his subjects, but seeks to expose the most insidious dynamics of discrimination in the everyday – that is, in the simple ways people and their surroundings present themselves before his eyes. His work is all the more subtle in that it doesn’t always engage head-on with politics, or at least at first glance.”

Violaine Boutet de Monvel. “David Goldblatt and the Legacy of Apartheid,” on the Aperture website March 2018 [Online] Cited 30/04/2024

One of Goldblatt’s early methods for accessing such intimate spaces, in addition to word of mouth and fortuitous encounters, was to post classified advertisements in local newspapers requesting sitters for his portraits. Goldblatt’s ads for his personal work often included a note of reassurance, one of which gave our exhibition its title: “I would like to photograph people in their homes in Johannesburg, Randburg and Sandton. There will be no charge and one free print will be supplied. Further copies at cost price. There is no catch and no ulterior motive.”

In the most practical sense, Goldblatt’s use of “no ulterior motive” was supposed to allay concerns that he was trying to take advantage of his sitters. But this message also conveys the promise of a transparent and straightforward photographic encounter, a working method that cuts across his body of work. …

Even as he positioned himself as a photographer without an ulterior motive, Goldblatt certainly had an intention for the resulting photographs: to use them in service of understanding and representing South African social relations. He applied his analysis, captions, and sequencing to the pictures and presented them to a broad public audience. At first, much of Goldblatt’s work appeared in magazines and journals, but he labored to publish his photographs in books, finding them the ideal format to crystallize his perspective on South African people, history, and land.

Leslie Wilson and Yechen Zhao. “In the Room with David Goldblatt,” on the Art Institute of Chicago website December 19, 2023 [Online] Cited 11/07/2024

The renowned South African photographer David Goldblatt (Randfontein, Union of South Africa, British Empire 1930 – Johannesburg, 2018, South Africa) dedicated his life to documenting his country and its people. His photography focused on capturing issues related to South African society and politics, subjects that are essential today for a visual understanding of one of history’s most painful processes: apartheid.

David Goldblatt: No Ulterior Motive, organised in collaboration with the Art Institute of Chicago and the Yale University Art Gallery, is the first exhibition to delve into the connections and dialogues Goldblatt established with other photographers from different geographical and generational backgrounds who, like him, focused on representing the social and environmental changes taking place in their respective countries. Moreover, this ambitious project abounds in rare, old or unpublished material, and is exceptional in that it presents some series in their entirety. For all these reasons, the exhibition is intended as a fitting tribute to David Goldblatt, as well as the beginning of a new chapter in the study of his work.

Exhibition co-organised by The Art Institute of Chicago and the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, in collaboration with Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE

Installation views of the exhibition David Goldblatt: No Ulterior Motive at Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid

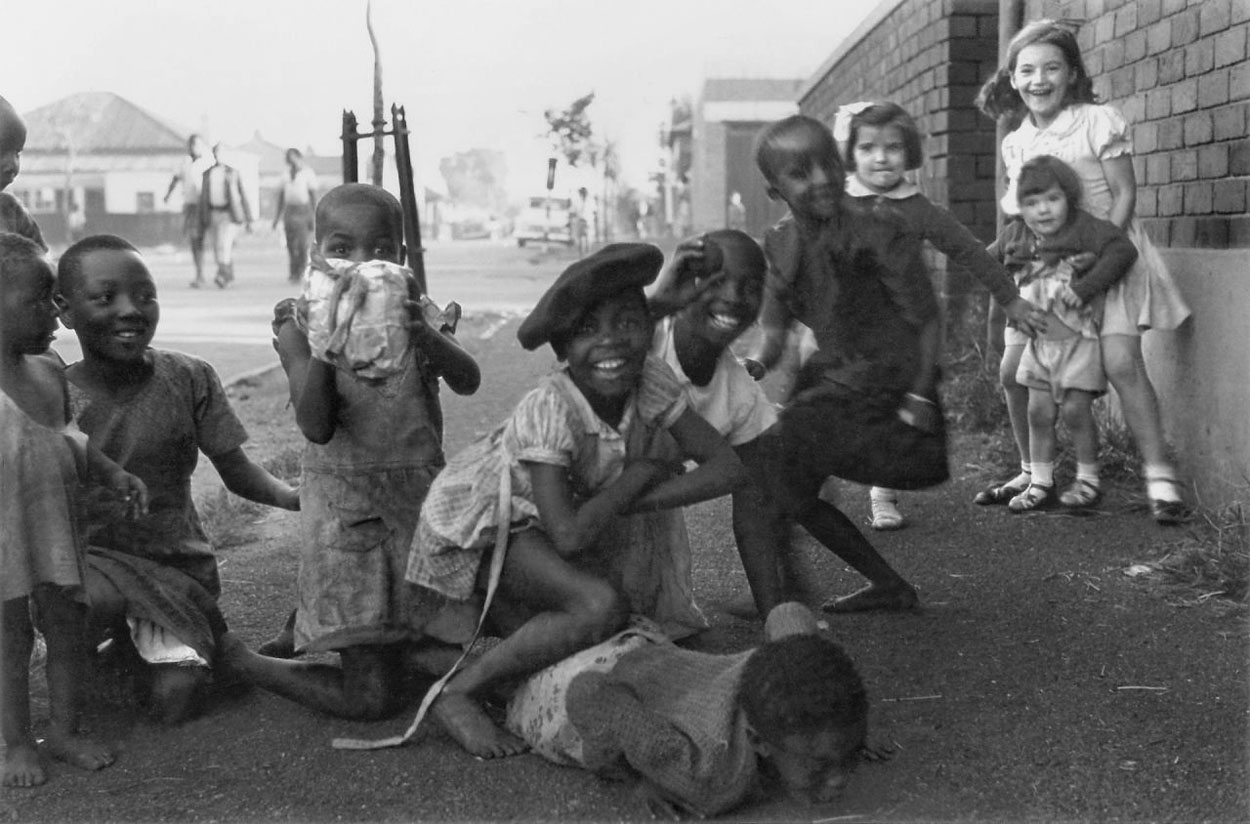

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Children on the border between Fietas and Mayfair, Johannesburg

1949, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

Goldblatt caught this raucous scene during his initial foray into photography just after high school. The spontaneous interaction of children of different races on a city street clashed with the country’s emerging politics at mid-century. The year before Goldblatt made this image, a white nationalist movement fomented by Afrikaners – an ethnic group descended predominantly from Dutch settlers – had come to political power as the National Party. In 1949 the government passed legislation to authorise new racial classifications and urban racial segregation. They subsequently allocated the neighbourhoods of Fietas (known officially as Pageview) and Mayfair as areas for white residents only, enforcing segregation by fines and compulsory resettlement.

Wall text from the exhibition

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

A plot-holder, his wife, and their eldest son at lunch, Wheatlands, Randfontein

1962, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

The artistic career of South African artist David Goldblatt (1930, Randfontein – 2018, Johannesburg) embraced both a wide geographical spread of his country and a wide variety of human situations portraying the day-to-day life of his fellow citizens during and after apartheid. From his beginnings in 1950, his work – which he has progressively reflected in numerous books – has gone hand in hand with the historical, political, social and economic evolution of South Africa. From 1999 onwards, Goldblatt adopted colour for his work, which focused on the harsh living conditions of the post-apartheid period.

Goldblatt photographed with great objectivity the “watchmen”, dissidents, settlers and victims of that regime, the cities they lived in, their buildings, the inside of their homes… His images provide an extensive and touching visual record of the racist apartheid regime, a record that never explicitly shows its violence but clearly reveals all that it represented, as he himself pointed out: […] I avoid violence. And I wouldn’t know how to handle it as a photographer if I found myself caught up in a violent scene […] But then I’ve long since realised – it took me a few years to realise – that events in themselves are not so interesting to me as the conditions that led to the events. These conditions are often quite commonplace, and yet full of what is imminent. Immanent and imminent.

David Goldblatt. No ulterior motive gathers together nearly 150 works that show the continuity and strength of his work and also offers, for the first time, connections to other South African photographers from one to three generations later who acknowledge their debt to Goldblatt as a mentor who believed deeply in the value of exchange and debate, as well as in the importance of expressing one’s own opinions.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE website

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

A plot holder with the daughter of his servant, Wheatlands, Randfontein

1962

Gelatin silver print

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised donation of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

The son of an ostrich farmer waits with a labourer for the day’s work to begin, near Oudtshoorn, Cape Province (Western Cape) [El hijo de un criador de avestruces espera junto a un jornalero a que comience la jornada de trabajo, cerca de Oudtshoorn, Provincia del Cabo Occidental]

1966

Gelatin silver print

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised donation of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

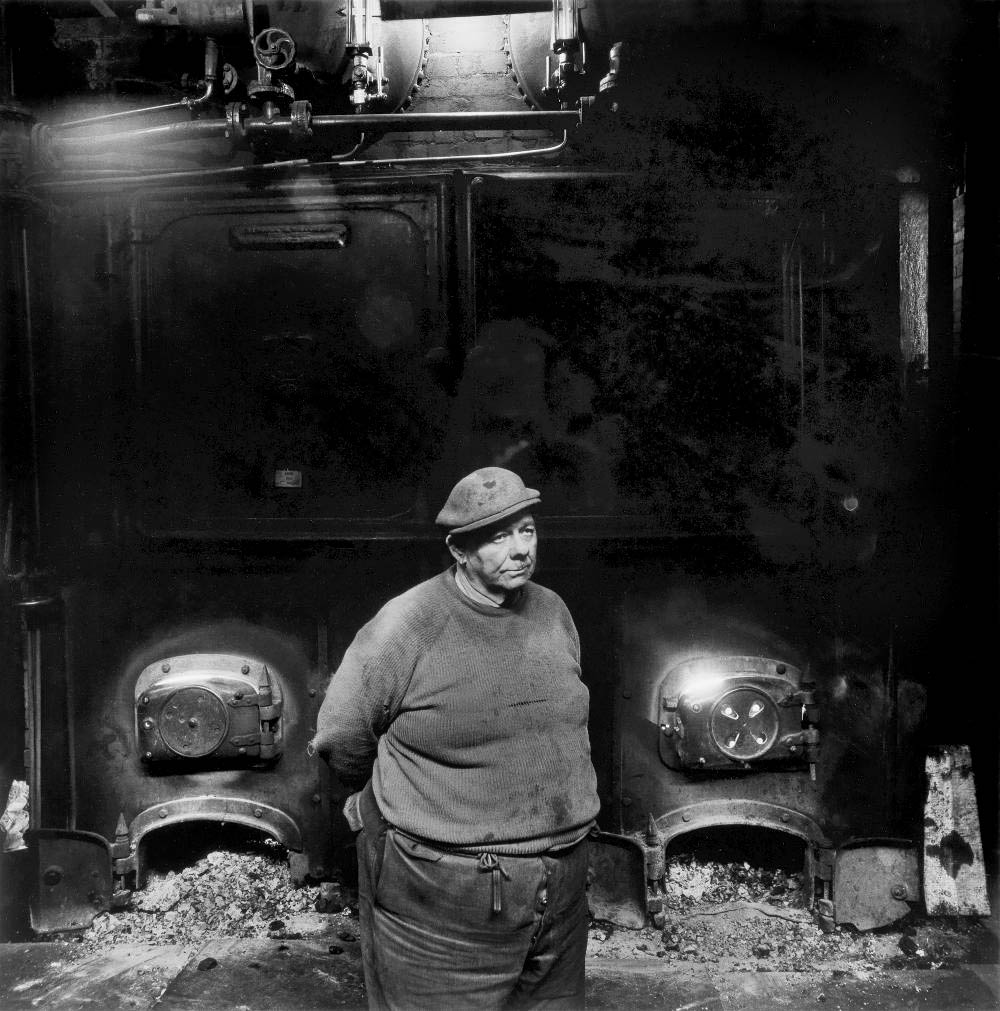

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Joe Maloney, boiler-hose attendant, City Deep Gold Mine

1966

Gelatin silver print

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised donation of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

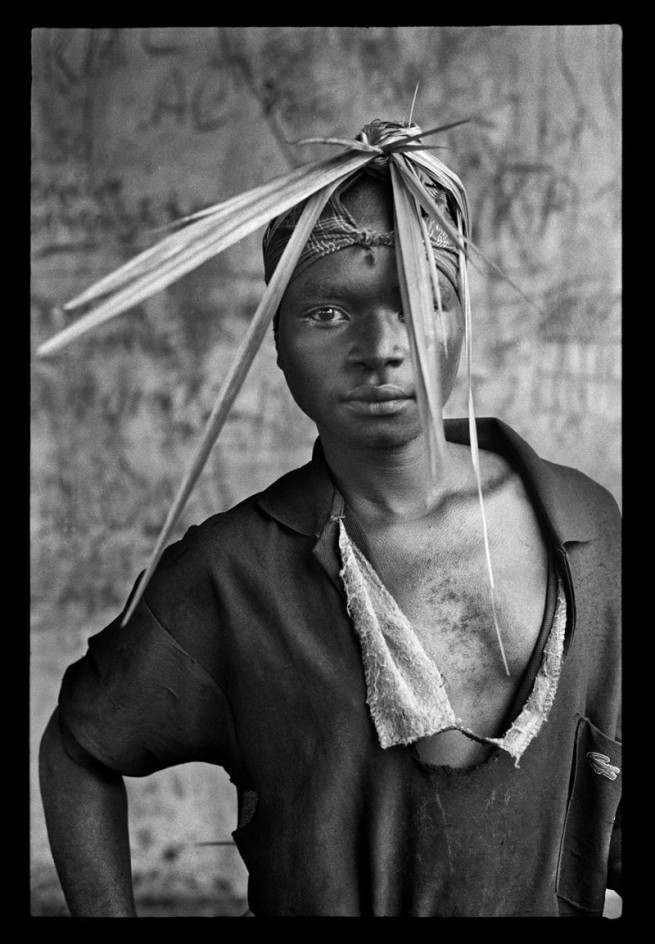

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

“Boss Boy” detail, Battery Reef, Randfontein Estates Gold Mine

1966, printed later

Platinum print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

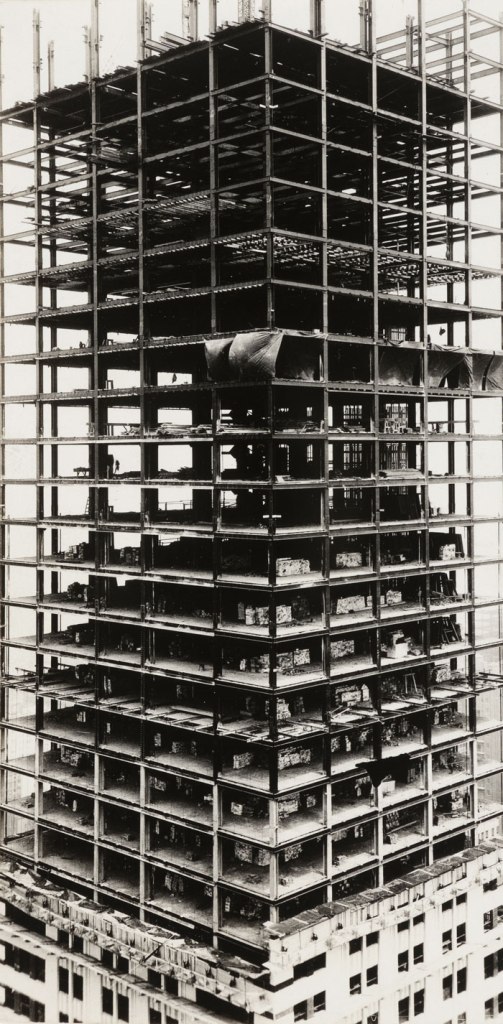

European settlement began at the Cape in 1652. The oldest modern structure still in existence is, appropriately, the Castle in Cape Town erected between 1666 and 1679 as a fortress to consolidate that settlement against growing opposition by indigenous people. The core of the history of this land in the 333 years since 1666 is its domination by white people, the subjection to them by force and institutionalised economic dependence of black people, and of sporadic and latterly of massively growing opposition by blacks and disaffected whites to the system of domination.

White hegemony approached its ultimate expression in the past thirty-nine years with the emergence of Afrikaner nationalism as the overwhelmingly ascendant social force in this society. The apotheosis of that force is the ideology of apartheid. There is hardly any part of life in this country that has not been profoundly affected by the quest for power, the determination to hold onto it, and the expression of that power through apartheid of the Afrikaner Nationalists and of their supporters and fellow travellers of other origins.

Innumerable structures of every imaginable kind and not a few ruins bear witness to the huge thrust of these movements across our land.

Now, Afrikaner nationalism, though by no means spent, is in decline. Change, probably convulsive, to something as yet unclear has begun. The first structures based in countervailing forces and ideology have made their tentative appearance.

David Goldblatt from the book “Structures,” 1987, p. 42

The fabric of this society permeates everything I do. I don’t know if this is the case with other photographers. I would dearly love to be a lyrical photographer. Every so often I try to branch out and rid myself of these concerns, but it rarely happens. You take your first breath of fresh air and you have compromised.

Recently I became very aware of the people thrown into detention. There is the elementary fact that is lost sight of in this country, that they are put in detention without trial, without recourse to the courts. Has become necessary here to remind ourselves of this fact. I have catalogued the faces fo some fo the people who have been in detention with something of their life and what happened to them in detention. I have also me with some who have been abused in detention. The photographs might in some small way, through their publication, act as a deterrent to further abuse or even to detention without trial itself. As the struggle for the survival of the apartheid system becomes more acute, so the system becomes more restrictive, especially with regard to the flow of information. We are going into a period of long darkness when the restrictions with become more severe. I am aware of photographing things that are disappearing and need to be documented, but in another sense I have a private mission to document what is happening in this country to form a record. There are many other photographers engaged in this. I regard this aspect of our work as very important, so that in the future, when the time comes, people will know what happened here, what transpired.

David Goldblatt from the book “Structures,” 1987, p. 68

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Gang on surface work, Rustenberg Platinum Mine, Rustenburg, North-West Province [Cuadrilla en trabajos de superficie, mina de platino de Rustenberg, Provincia del Noroeste]

1971

Carbon ink print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Young men with dompas (an identity document that every African had to carry), White City, Jabavu, Soweto

1972

Gelatin silver print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

Two men lean against one another tenderly as one holds up an identification document called a passbook. under the Pass Laws Act of 1952, all Black South Africans over the age of 16 were required to carry such identification at all times. Passbooks were also known as dompas, a term deriving from the phrase “dumb pass,” used to openly mock this hated tool for enforcing apartheid. Anyone stopped by police without a passbook or official permission to be in a given area could be penalised with arrest or fines. Policies that restricted the movement of Black people throughout the country have a long history in South Africa and were a key target of resistance movements.

Wall text from the exhibition

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

In the office of the funeral parlour, Orlando West, Soweto [En la oficina de la funeraria, Orlando West, Soweto]

1972

Gelatin silver print

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised donation of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

In his photographs of office and office workers, Goldblatt often teased out the continuities between professional and private identities. The two women in this photograph are dressed for winter on Earth, but the art on the walls hearkens to a journey to outer space. At this moment in 1972, apartheid was so firmly in place that, for many, change was almost unthinkable – perhaps akin to landing on the moon. The artwork brings the prospect of liberty and the sheer thrill of adventure into an otherwise ordinary setting. Of course, the art might not have been their choice at all, but the photograph holds open the possibility that these women have a stake in missions long thought impossible.

Wall text from the exhibition

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Lulu Gebashe and Solomon Mlutshana, who both worked in a record shop in the city, Mofolo Park [Lulu Gebashe y Solomon Mlutshana, que trabajaban en una tienda de discos de la ciudad, Mofolo Park]

1972

Carbon ink print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Miriam Diale, 5357 Orlando East, Soweto, 18 October 1972 [Miriam Diale, Orlando East n.º 5357, Soweto, 18 de octubre de 1972]

1972

Carbon ink print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Wedding photography at the Oppenheimer Memorial, Jabavu, Soweto

1972, printed later

Carbon ink print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

The grandson of Lithuanian refugees, David Goldblatt was born in Randfontein in 1930 and spent most of his life in Johannesburg. From a very young age he showed an interest in photography and took his first images when he was only eighteen. After the death of his father, in 1963 he decided to become a professional photographer.

David Goldblatt scrupulously examined the history and politics of South Africa, where he witnessed the rise of apartheid, its brutal segregationist policies and its eventual disappearance. His sensitive photographs offer a vision of daily life under this regime and in the complex period that followed, when he moved from black and white to colour in his work.

Employing great objectivity, Goldblatt photographed dissidents, settlers and victims of apartheid, the cities where they lived, their buildings, the interior of their homes, etc. His images configure a wide-ranging and moving visual record of this racist regime, a record which, while never explicitly showing its violence, clearly reveals everything it represented, as the artist himself pointed out: “I avoid violence. And I wouldn’t know how to handle it as a photographer if I found myself caught up in a violent scene […] But then I’ve long since realised – it took me a few years to realise – that events in themselves are not so interesting to me as the conditions that led to the events. These conditions are often quite commonplace, and yet full of what is imminent. Immanent and imminent.”

In 1998 David Goldblatt was the first South African to be the subject of a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. His work has been recognised with the Hasselblad (2006) and Henri Cartier-Bresson (2009) prizes and the International Center of Photography award (2013). In 2016 he was made a knight of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French government. He died in Johannesburg in 2018 at the age of eighty-eight.

David Goldblatt: No Ulterior Motive brings together around 150 works from several of the artist’s series with the aim of revealing the continuity of his work while also and for the first time establishing a dialogue with the work of other South African photographers of between one and three generations subsequent to Goldblatt, such as Lebohang Kganye, Ruth Seopedi Motau and Jo Ractliffe. Also on display are three mock-ups of books by Goldblatt, an aspect of his work to which he gave great importance.

The works on display are from the collections of The Art Institute of Chicago and Yale University Art Gallery and include important recent acquisitions of photographs by Goldblatt. Having been shown at The Art Institute of Chicago between December 2023 and March 2024, Fundación MAPFRE is now presenting the exhibition at its venue on Paseo de Recoletos, Madrid, until August this year. It will then be seen next year at Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven (Connecticut).

David Goldblatt: No Ulterior Motive is curated by Judy Ditner (Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven), Leslie M. Wilson and Matthew S. Witkovsky (The Art Institute of Chicago).

Key themes in the exhibition

Apparent tranquility

Throughout his career Goldblatt avoided the most difficult and shocking incidents that were a daily reality under apartheid. Rather, he considered that depicting everyday life, “the quiet and commonplace where nothing ‘happened'”, allowed the viewer to draw their own conclusions. The content was implicit in the apparent tranquility and in the very precise captions that accompany these images, which show ongoing, daily expressions of racism and the economic, social and political exploitation of the Black population under white rule.

Goldblatt, No Ulterior Motive

Goldblatt’s status as a white man allowed him greater freedom of movement and he took advantage of that privilege to document life in South Africa in the most honest and direct way possible. In the early 1970s he published a classified ad which read: “I would like to photograph people in their homes […]. No ulterior motive.” Nonetheless, this impartiality concealed a critical perspective towards his country’s people, history and geography.

Apartheid

In 1948 the National Party, one of the most visible entities representing Afrikaners (a European, colonising ethnic group mainly comprising descendants of the Dutch, North Germans and French), came to power in South Africa. This minority of European origin then proceeded to institute apartheid as a State policy while promoting the ideology that people of different racial origins could not live together in equality and harmony. Successive governments reinforced the legacy of racist oppression against non-white peoples (indigenous Africans, people of Asian origin and those of mixed race), who made up more than 80% of the population. In 1990 segregation laws began to be eliminated, the activity of the African National Congress was legalised and its most important leader, Nelson Mandela, who was elected president of South Africa in 1993, was released from prison.

Press release from Fundación MAPFRE

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Sylvia Gibbert in her apartment, Melrose, Johannesburg [Sylvia Gibbert en su apartamento, Melrose, Johannesburgo]

1974

Gelatin silver print

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised donation of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Ozzie Docrat with his daughter Nassima in his shop before its destruction under the Group Areas Act, Fietas, Johannesburg [Ozzie Docrat con su hija Nassima en su tienda antes de ser destruida en virtud de la Ley de Agrupación por Áreas, Fietas, Johannesburgo]

1977

From the series Fietas

Carbon ink print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

“I feel as though my teeth are being pulled out one by one. I run by tongue over the spaces and I try to remember the shape of what was there.” These words, spoken to Goldblatt by shop owner Ozzie Docrat, express what many residents must have experienced during their forced removal from the Johannesburg suburb of Fietas in the 1970s. Throughout the mid-20th century, Fietas was exceptional for the endurance of it multiracial, interfaith community of working- and middle-class people in the face of encroaching segregationist housing policies. In 1977, however, the government forced out Indian families like the Docrats, along with other people of color, to make this area exclusive to whites.

Wall text from the exhibition

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Sunday morning: A not-White family living illegally in the “White” group area of Hillbrow, Johannesburg [Domingo por la mañana: una familia no blanca viviendo ilegalmente en la zona “blanca” de Hillbrow, Johannesburgo]

1978

Pigmented inkjet print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

“Over the course of a career that spanned more than six decades, Goldblatt went looking for scenes like this one – quiet and tender, while also deeply revealing of the structures and values that constituted South African society. Though the family appears to be right at home, Goldblatt’s title shares that they were living illegally in the Johannesburg neighborhood of Hillbrow, violating laws that, under the system of segregation known as apartheid, dictated where different racial groups were permitted to reside. The cozy scene is therefore profoundly fragile because the family faced the persistent threat of removal.

This image powerfully presents the tensions that were central to what Goldblatt pursued through photography: soft furnishings and brutal laws, proximity and distance, access and exclusion, and informality and formality.”

Leslie Wilson and Yechen Zhao. “In the Room with David Goldblatt,” on the Art Institute of Chicago website December 19, 2023 [Online] Cited 11/07/2024

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Methodists meet to find ways of reducing the racial, cultural, and class barriers that divide them, 3 July 1980

1980, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

Throughout South Africa and even across the continent, religion bears a complicated history embroiled in legacies of colonisation, oppression, and apartheid. Religion holds power. It was through the cross and the bullet that the continent was dissected by European powers. It was through the pages of the Bible that apartheid was theologically justified, and it was through the Dutch Reformed Church of white Afrikaners that “the races” were declared separate as mandated by God. Yet, it was also through the World Alliance of Reformed Churches that apartheid was acknowledged as heresy. It was through the Christian ethos and through ubuntu that Archbishop Desmond Tutu guided the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission through ways of healing in a society bifurcated into “European” and “Non-White;” “have” and “have-not;” “believer” and “unbeliever.” Religion has the power to both destroy and heal a nation.

In a discussion about life under apartheid, my South African friend designated as “Coloured” – a category in between “White” and “Black African” – revealed that his parents were once denied communion on Sunday morning due to their sin of attending a “white church” while being of color. Whiteness meant purity and closeness with God; anything less than was deemed as “separate,” “other,” “unworthy” – “impure.” The sharing of bread and wine in the Christian tradition is meant to signify connection between people and between the divine. The denial of such connection, of saying that one was unworthy to drink from the same chalice because of one’s race or ethnicity, is an ultimate denial of humanity. It is an affront to the very word “communion” and an insult to fellowship. Religion was co-opted to subjugate and enforce a system of racial hierarchy. Sunday morning saw no race-mixing amongst God’s children.

Trevor O’Connor. “Religion in South Africa: The Power to Destroy and Heal a Nation,” on the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs website November 16, 2018 [Online] Cited 11/07/2024

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Saturday morning at the hypermarket: Semifinal of the Miss Lovely Legs Competition, 28 June 1980 [Sábado por la mañana en el hipermercado: semifinal del concurso Miss Piernas Bonitas, 28 de junio de 1980]

1980

Carbon ink print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Apostolic Faith Mission (AGS), Birchleigh, Kempton Park, 28 December 1983 [Misión de la Fe Apostólica (AGS, en afrikáans), Birchleigh, Kempton Park, 28 de diciembre de 1983]

1983

Gelatin silver print

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised donation of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

Goldblatt’s photographs of churches were so beautiful. They were wonderful architectural images, but they were deep with meaning capturing the issues of a missionary religion in a nonnative land. They symbolise the conflicts within the country which mirrored issues throughout other parts of the world. When I thought about South Africa it was about apartheid and relationships between blacks and whites, I had not considered the impact of western religion on the indigenous population (I should have because it is an issue still in our country today), nor did I know about the issues with the Muslim population in the country. In researching the issue of religion further, it appears the conflicts and violence in South Africa related to it appear to be ongoing to this day.

William Carl Valentine. “David Goldblatt: No Ulterior Motive,” on the William Carl Valentine website June 15, 2024 [Online] Cited 06/07/2024

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Thirteen kilometres of this coastline were a White Group Area, Bloubergstrand, Cape Town, 9 January 1986 [Trece kilómetros de esta costa eran una zona reservada para blancos, Bloubergstrand, Ciudad del Cabo, 9 de enero de 1986]

1986

Carbon ink print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Assegais, shield, and 23-metre-high cross of the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk in Afrika, (Dutch Reformed Mission Church to Africans), which stands above Dingane’s destroyed capital, uMgungundlovu. The church was burnt down in 1985; Dinganestad, Natal

1989, printed later

Carbon ink print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt (1930-2018) scrupulously examined the history and politics of South Africa, where he witnessed the rise of apartheid, its divisive and brutal policies, and its eventual demise. His sensitive photographs offer a view of daily life under the apartheid system and its complex aftermath. Goldblatt was drawn, in his own words, “to the quiet and commonplace where nothing ‘happened’ and yet all was contained and immanent.” Accompanied by precise captions, his images expose everyday manifestations of racism and point to Black dispossession – economic, social, and political – under white rule.

The grandson of Lithuanian Jews who had fled Europe in the 1890s, Goldblatt spent most of his life in Johannesburg. Although not part of the ascendant Dutch Protestant community, his position as a white man allowed him greater freedom of movement and he leveraged this privilege to document life in South Africa as honestly and straightforwardly as possible. In the early 1970s, he placed a classified ad: “I would like to photograph people in their homes […]. No ulterior motive.” Yet this professed impartiality masked a critical perspective toward South Africa’s people, history, and geography.

Goldblatt first took up the camera in 1948, the year the apartheid system was introduced, and over the next seven decades he assiduously photographed South Africa’s people, landscape, and built environment. Recognising the layered connections in his oeuvre, this exhibition proceeds thematically rather than chronologically: here, black-and-white photographs taken during the period of institutionalised segregation are interwoven with his work in colour from the 1990s on. Six thematic sections explore Goldblatt’s engagement with apartheid, its contradictions, and its multifaceted legacy.

Installation view of the exhibition David Goldblatt: No Ulterior Motive at Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid showing at left, wall text from the section ‘Informality’ (see below)

1/ Informality

Goldblatt’s photographs, especially his portraits, ask us to consider the informal and often idiosyncratic ways people resist oppression. Attuned to how his status and relative freedom as a white man influenced all social encounters, Goldblatt gained access to intimate moments of South Africans’ everyday lives by thoughtfully avoiding behaviour that might suggest an exercise of authority. Instead, he observed how frequently people segregated by law engaged in unsanctioned social and economic exchanges. Whether photographing descendants of Dutch colonists farming in the rural Cape in the early 1960s for the series Some Afrikaners Photographed, or a young Black couple in Johannesburg, Goldblatt emphasised the improvised realities of everyday life. This interest shifted in later years to the housing and mercantile arrangements dubbed South Africa’s “informal economy,” as well as to unofficial monuments to historical figures and events.

2/ Working people

Even as the architects of apartheid sought to separate South Africans, the system functioned through an economic structure that placed people into tense proximity on a daily basis. White families hired Black workers to raise their children and clean their homes; mines owned and managed by whites depended on people of color to perform the most dangerous labor. Government-dictated racial categories profoundly shaped the jobs that people could hold, creating strict hierarchies in workplaces. Goldblatt highlighted these inequalities with pictures like one of a domestic worker rushing to meet her employer. At the same time, he attended to how people retained a sense of self and dignity in their labor, as in his portraits of mineworkers who chose to pose for his camera in their traditional clothing.

3/ Extraction

Born in the mining town of Randfontein, Goldblatt began his career by looking at the extractive economy built by colonial ventures to exploit its natural resources. Goldblatt created his earliest series, On the Mines (1964–73), while working as a photographer for the country’s biggest mining corporations. The series showed how a predominantly Black migrant labor force performed the most dangerous work in gold and platinum mines, work that primarily enriched their white bosses. Decades later, the photographer found similar manifestations of inequality while recording the toxic legacy of asbestos mining and its disproportionate impact on Black communities.

4/ Near/Far

The white supremacist National Party, led by Afrikaners (descendants of predominantly Dutch settlers) and English-speaking whites, attempted to impose distance between people of different racial categories in South Africa. Goldblatt looked at how the National Party government pulled people from their homes to realise its vision of racial segregation, dispossessing and dispersing Black and Indian residents to make room for new white neighbourhoods.

However, the exclusive urban centres the party sought to create could not function without a daily influx of labourers and domestic workers from the country’s diverse population. Goldblatt was interested in the ways closeness continued to manifest even when distance was dictated by law, a status quo that also affected his relationship with the people he photographed. These images wryly register the constant collision of segregated groups in public and private spaces throughout the country.

5/ Disbelief

The illogic of apartheid led to widespread skepticism and practices of self-delusion among those who actively perpetuated the system. The photographs in this section capture the sense of disbelief with the labyrinthine, endlessly rewritten laws intended to legitimise a morally bankrupt system of abuse and oppression. Goldblatt rendered this state of affairs in brilliant deadpan, giving visual form to the incredulity that all but the most cynical and opportunistic beneficiaries of apartheid must have felt. Fortress-like churches of the Dutch Reformed Protestant faith mix with absurd scenes of suburban leisure in whites-only areas, while stony or stoic gazes meet moments of sudden demolition. Even after the official end of apartheid, Goldblatt continued to photograph sites that inspired feelings of disbelief as seen in his photographs of incomplete housing developments.

6/ Assembly

How do people come together in a country divided by segregation? In everything, from the bench they could sit on to where they could live, South Africans were physically separated by race. In the 1950s, protests against these new policies were common, but in the decades that followed, the government introduced increasingly brutal tactics to repress dissent and severely curtailed the right to assemble.

Goldblatt avoided straightforward depictions of open rebellion, seeing his country’s political struggles as clearly in the routine occasions that brought people together by choice or necessity. In later decades, he engaged more with overtly political subjects, turning his camera to newly elected lawmakers and young South Africans openly protesting colonial legacies in their post-apartheid society.

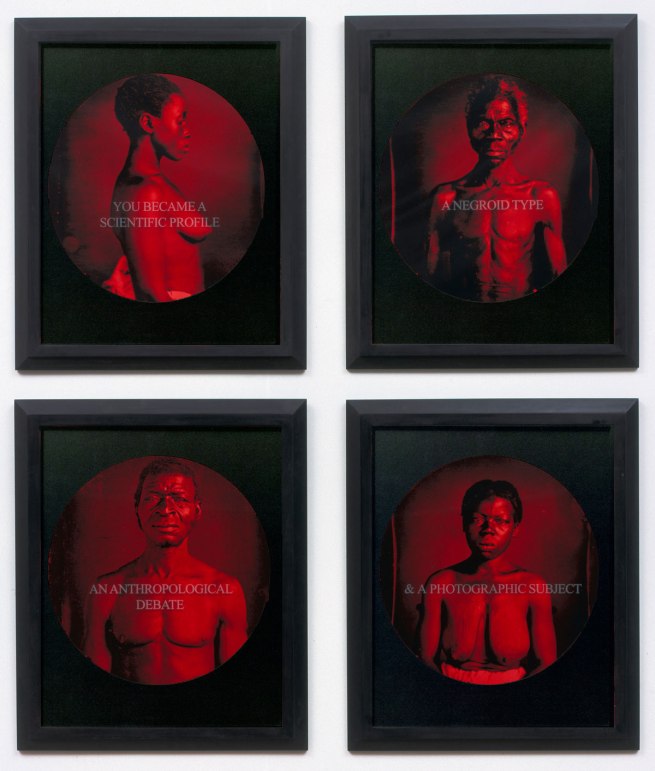

7/ Connections

Beyond his own work, Goldblatt was committed to aiding future generations of South African photographers. He helped found the Market Photo Workshop in 1989 to offer instruction and support to emerging, socially engaged photographers, hoping the school would be “a small counter to the ethnic surgery that had so successfully separated South Africans under apartheid.” Today, it remains a centre of education and community for photography in Johannesburg. Lebohang Kganye, Sabelo Mlangeni, Ruth Seopedi Motau, and Zanele Muholi are alumni with close ties to Goldblatt, who was a friend and mentor. All have explored themes of belonging, loss, memory, migration, and representation while uncovering original, often deeply personal ways to examine South Africa’s people, places, and policies.

Like Goldblatt, the artists in this gallery – Ernest Cole, Santu Mofokeng, and Jo Ractliffe – use the camera to reflect critically on their country’s society and politics. Cole used his camera to confront sweeping social, political, and environmental change from the 1950s to the 1980s. Mofokeng was a member of the Afrapix collective of South African documentary photographers throughout the 1980s. A former student of Goldblatt, he received his first long-term position in photography in part through Goldblatt’s recommendation. Ractliffe’s landscape photographs address issues of displacement and conflict, capturing the traces of often violent histories. She knew Goldblatt as a friend and colleague and has taught at the Market Photo Workshop, a vitally important school for photography in Johannesburg whose alumni are featured in gallery 3.

Text from the exhibition

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Victoria Cobokana, housekeeper, in her employer’s dining room with her son Sifiso and daughter Onica, Johannesburg, June 1999. Victoria died of AIDS on 13 December 1999, Sifiso dies of AIDS on 12 January 2000, Onica died of AIDS in May 2000, June 1999

1999

Pigmented inkjet print

The Art Institute of Chicago, Promised gift of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

One might argue that in his own silent way, he was an activist, using his camera to expose things that should never have been allowed to happen. A single color image seems to define the show – in it, a housekeeper sits in her employer’s dining room with her two children on her lap. Behind her a round window forms a halo around her wrapped head, Madonna-like. The didactic tells us that all three of them died of AIDS within months. Such is the inequity of South Africa, quietly portrayed by David Goldblatt over seven decades.

Susan Aurinko. “Painful Truths: A Review of David Goldblatt at the Art Institute of Chicago,” on the New City Art website December 22, 2023 [Online] Cited 07/07/2024

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Swerwers, nomadic sheep shearers and farmworkers descended from the San hunter-gatherers and Khoi pastoralists. Without work for four months they lived in the gang, the corridor between farms, fences and roads, hunting, fishing when they could, and eating roadkill, near Nuwe Rooiberg, Northern Cape, 18 September 2002 [Swerwers, esquiladores de ovejas y trabajadores agrícolas nómadas, descendientes de los cazadores-recolectores san y de los pastores khoi. Sin trabajo durante cuatro meses, vivían en el paso, el corredor que hay entre las vallas de las granjas y las carreteras, cazando, pescando cuando podían y comiendo animales atropellados, cerca de Nuwe Rooiberg, Cabo Septentrional, 18 de septiembre de 2002]

2002, printed 2005

Pigmented inkjet print

The Art Institute of Chicago, Promised gift of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Highly carcinogenic blue asbestos waste on the Owendale Asbestos Mine tailings dump, near Postmasburg, Northern Cape. The prevailing wind was in the direction of the mine officials’ houses at right. 21 December, 2002

2002, printed 2005

Pigmented inkjet print

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

Installation view of the exhibition David Goldblatt: No Ulterior Motive at Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid showing at right, Goldblatt’s Near Brak Pannen on the Beaufort West-Fraserburg road, Nuweveld, Karoo, 30 May 2004 (2004, below)

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Near Brak Pannen on the Beaufort West-Fraserburg road, Nuweveld, Karoo, 30 May 2004

2004

Pigmented inkjet print

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised gift of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

Next to a road that shoots arrow-straight to the horizon, a pool of water evaporates from the intense sunlight of the Karoo, the semi-arid region that separates Cape Town from South Africa’s interior. The scarcity of water and the harsh climate in this enormous area impeded white settlers from centuries, an the lack of grand natural or manmade features confounded their desire to assimilate it into their idea of a beautiful landscape. From the 2000s onward Goldblatt made much of his new work by driving great distances through the Karoo. He appreciated the way it resisted easy aestheticisation, calling it the “fuck-all landscape.”

Wall text from the exhibition

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Incomplete houses, part of a stalled municipal development of 1,000 houses. The funding allocation was made in 1998, building started in 2003. Officials and a politician gave various reasons for the stalling of the scheme: Shortage of water, theft of materials, problems with sewage disposal, problems caused by the high clay content of the soil, and shortage of funds. By August 2006, 420 houses had been completed, Lady Grey, Eastern Cape, 5 August 2006 [Casas sin terminar, parte de una promoción municipal de 1.000 viviendas paralizada. La financiación se consignó en 1998 y la construcción empezó en 2003. Los funcionarios y un político dieron varias razones para la paralización del proyecto: escasez de agua, robo de materiales, problemas con la evacuación de aguas residuales, problemas causados por el alto contenido de arcilla del suelo y escasez de fondos. En agosto de 2006 se habían terminado 420 viviendas, Lady Grey, Cabo Oriental, 5 de agosto de 2006]

2006

Pigmented inkjet print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

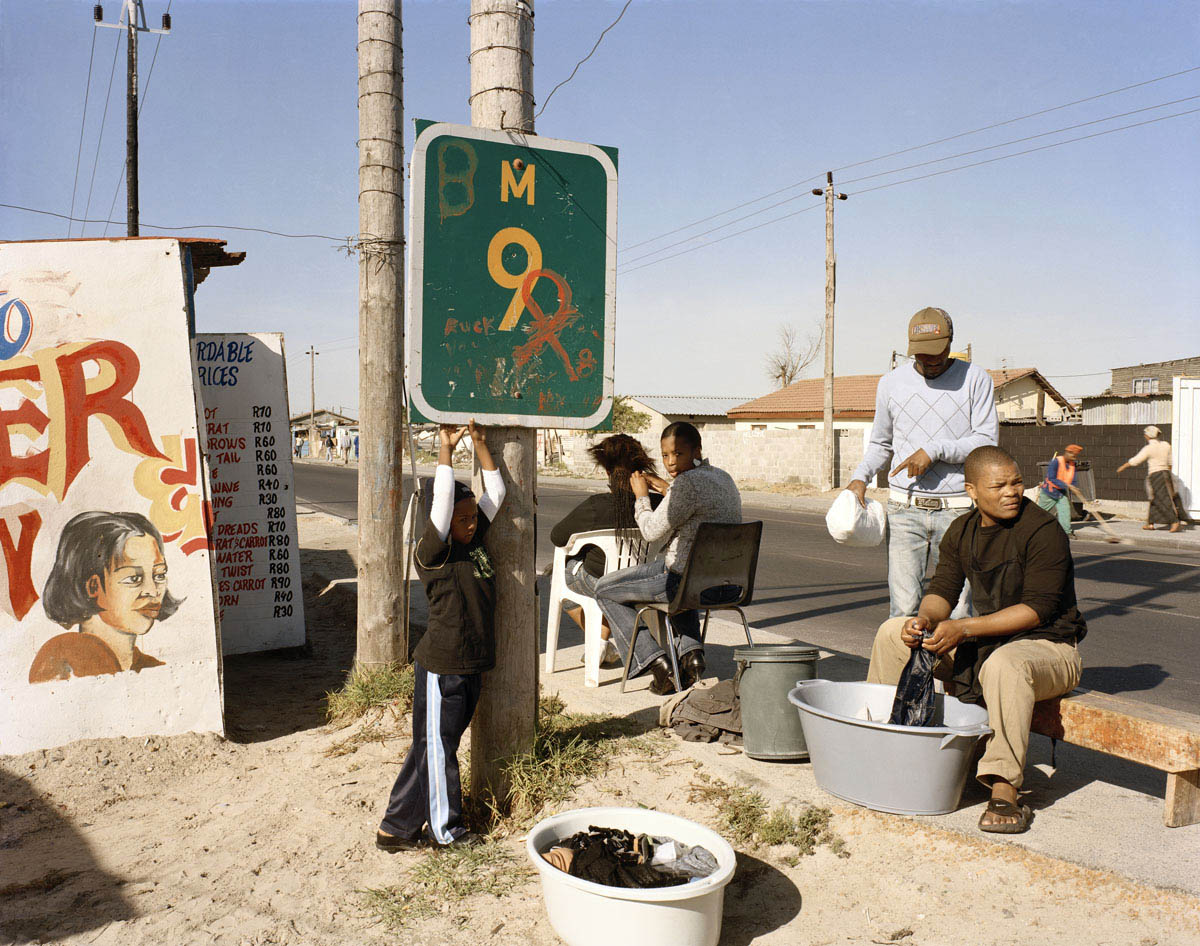

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

At Kewin Kwaneles Takwaito Barber, Landsdowne Road, Cape Town in the time of AIDS, 16 May 2007

2007

Pigmented inkjet print

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised gift of Cecily Cameron and Derek Schrier

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

The dethroning of Cecil John Rhodes, after the throwing of human feces on the statue and the agreement of the university to the demands of students for its removal, the University of Cape Town, 9 April 2015 [El derrocamiento de Cecil John Rhodes después de arrojar heces humanas contra la estatua y de que la universidad accediera a las demandas de los estudiantes para su retirada, Universidad de Ciudad del Cabo, 9 de abril de 2015]

2015

Carbon ink print

Yale University Art Gallery, New haven, Connecticut, purchased with a gift from Jane P. Watkins, M.P.H. 1979; with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund; and with support from the Reinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

Here, Goldblatt joined a mass of onlookers recording the removal of the statue of 19th-century British mining magnate Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town (UCT). Rhodes vastly expanded European colonial rule on the African continent and exploited local labour to amass immense wealth. Disgusted by what they viewed as a symbol of white supremacy, student activists successfully campaigned to take down the statue honouring Rhodes.

UCT responded to this and related student protests by forming a committee to evaluate art on campus, intending to remove or hide problematic works from view. While Goldblatt had promised his archive to the university, he became concerned that this committee might censor art ad free speech. He ultimately withdrew his offer in 2017, bequeathing his archive to Yale University instead. In response to this decision, scholar Njabulo S. Ndebele has asked. “Was Goldblatt worried that the photographs would not survive the tests of freedom, even after they had survived those of oppression?”

Wall text from the exhibition

Fundación MAPFRE

Recoletos Exhibition Hall

Paseo Recoletos 23, 28004 Madrid

Opening hours:

Mondays (except holidays): 2pm – 8pm

Tuesday to Saturday: 11am – 8pm

Sunday and holidays: 11am – 7pm

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'The son of an ostrich farmer waits with a labourer for the day's work to begin, near Oudtshoorn, Cape Province (Western Cape)' [El hijo de un criador de avestruces espera junto a un jornalero a que comience la jornada de trabajo, cerca de Oudtshoorn, Provincia del Cabo Occidental] 1966 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'The son of an ostrich farmer waits with a labourer for the day's work to begin, near Oudtshoorn, Cape Province (Western Cape)' [El hijo de un criador de avestruces espera junto a un jornalero a que comience la jornada de trabajo, cerca de Oudtshoorn, Provincia del Cabo Occidental] 1966](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/01.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Gang on surface work, Rustenberg Platinum Mine, Rustenburg, North-West Province' [Cuadrilla en trabajos de superficie, mina de platino de Rustenberg, Provincia del Noroeste] 1971 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Gang on surface work, Rustenberg Platinum Mine, Rustenburg, North-West Province' [Cuadrilla en trabajos de superficie, mina de platino de Rustenberg, Provincia del Noroeste] 1971](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/02.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'In the office of the funeral parlour, Orlando West, Soweto' [En la oficina de la funeraria, Orlando West, Soweto] 1972 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'In the office of the funeral parlour, Orlando West, Soweto' [En la oficina de la funeraria, Orlando West, Soweto] 1972](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/03.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Lulu Gebashe and Solomon Mlutshana, who both worked in a record shop in the city, Mofolo Park' [Lulu Gebashe y Solomon Mlutshana, que trabajaban en una tienda de discos de la ciudad, Mofolo Park] 1972 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Lulu Gebashe and Solomon Mlutshana, who both worked in a record shop in the city, Mofolo Park' [Lulu Gebashe y Solomon Mlutshana, que trabajaban en una tienda de discos de la ciudad, Mofolo Park] 1972](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/04.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Miriam Diale, 5357 Orlando East, Soweto, 18 October 1972' [Miriam Diale, Orlando East n.º 5357, Soweto, 18 de octubre de 1972] 1972 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Miriam Diale, 5357 Orlando East, Soweto, 18 October 1972' [Miriam Diale, Orlando East n.º 5357, Soweto, 18 de octubre de 1972] 1972](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/05.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) ;Sylvia Gibbert in her apartment, Melrose, Johannesburg; [Sylvia Gibbert en su apartamento, Melrose, Johannesburgo] 1974 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) ;Sylvia Gibbert in her apartment, Melrose, Johannesburg; [Sylvia Gibbert en su apartamento, Melrose, Johannesburgo] 1974](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/06.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Ozzie Docrat with his daughter Nassima in his shop before its destruction under the Group Areas Act, Fietas, Johannesburg' [Ozzie Docrat con su hija Nassima en su tienda antes de ser destruida en virtud de la Ley de Agrupación por Áreas, Fietas, Johannesburgo] 1977 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Ozzie Docrat with his daughter Nassima in his shop before its destruction under the Group Areas Act, Fietas, Johannesburg' [Ozzie Docrat con su hija Nassima en su tienda antes de ser destruida en virtud de la Ley de Agrupación por Áreas, Fietas, Johannesburgo] 1977](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/07.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Sunday morning: A not-White family living illegally in the "White" group area of Hillbrow, Johannesburg' [Domingo por la mañana: una familia no blanca viviendo ilegalmente en la zona "blanca" de Hillbrow, Johannesburgo] 1978 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Sunday morning: A not-White family living illegally in the "White" group area of Hillbrow, Johannesburg' [Domingo por la mañana: una familia no blanca viviendo ilegalmente en la zona "blanca" de Hillbrow, Johannesburgo] 1978](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/08.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Saturday morning at the hypermarket: Semifinal of the Miss Lovely Legs Competition, 28 June 1980' [Sábado por la mañana en el hipermercado: semifinal del concurso Miss Piernas Bonitas, 28 de junio de 1980] 1980 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Saturday morning at the hypermarket: Semifinal of the Miss Lovely Legs Competition, 28 June 1980' [Sábado por la mañana en el hipermercado: semifinal del concurso Miss Piernas Bonitas, 28 de junio de 1980] 1980](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/09.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Apostolic Faith Mission (AGS), Birchleigh, Kempton Park, 28 December 1983' [Misión de la Fe Apostólica (AGS, en afrikáans), Birchleigh, Kempton Park, 28 de diciembre de 1983] 1983 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Apostolic Faith Mission (AGS), Birchleigh, Kempton Park, 28 December 1983' [Misión de la Fe Apostólica (AGS, en afrikáans), Birchleigh, Kempton Park, 28 de diciembre de 1983] 1983](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/10.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Thirteen kilometres of this coastline were a White Group Area, Bloubergstrand, Cape Town, 9 January 1986' [Trece kilómetros de esta costa eran una zona reservada para blancos, Bloubergstrand, Ciudad del Cabo, 9 de enero de 1986] 1986 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Thirteen kilometres of this coastline were a White Group Area, Bloubergstrand, Cape Town, 9 January 1986' [Trece kilómetros de esta costa eran una zona reservada para blancos, Bloubergstrand, Ciudad del Cabo, 9 de enero de 1986] 1986](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/11.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Swerwers, nomadic sheep shearers and farmworkers descended from the San hunter-gatherers and Khoi pastoralists. Without work for four months they lived in the gang, the corridor between farms, fences and roads, hunting, fishing when they could, and eating roadkill, near Nuwe Rooiberg, Northern Cape, 18 September 2002' [Swerwers, esquiladores de ovejas y trabajadores agrícolas nómadas, descendientes de los cazadores-recolectores san y de los pastores khoi. Sin trabajo durante cuatro meses, vivían en el paso, el corredor que hay entre las vallas de las granjas y las carreteras, cazando, pescando cuando podían y comiendo animales atropellados, cerca de Nuwe Rooiberg, Cabo Septentrional, 18 de septiembre de 2002] 2002, printed 2005 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Swerwers, nomadic sheep shearers and farmworkers descended from the San hunter-gatherers and Khoi pastoralists. Without work for four months they lived in the gang, the corridor between farms, fences and roads, hunting, fishing when they could, and eating roadkill, near Nuwe Rooiberg, Northern Cape, 18 September 2002' [Swerwers, esquiladores de ovejas y trabajadores agrícolas nómadas, descendientes de los cazadores-recolectores san y de los pastores khoi. Sin trabajo durante cuatro meses, vivían en el paso, el corredor que hay entre las vallas de las granjas y las carreteras, cazando, pescando cuando podían y comiendo animales atropellados, cerca de Nuwe Rooiberg, Cabo Septentrional, 18 de septiembre de 2002] 2002, printed 2005](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/12.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Incomplete houses, part of a stalled municipal development of 1,000 houses. The funding allocation was made in 1998, building started in 2003. Officials and a politician gave various reasons for the stalling of the scheme: Shortage of water, theft of materials, problems with sewage disposal, problems caused by the high clay content of the soil, and shortage of funds. By August 2006, 420 houses had been completed, Lady Grey, Eastern Cape, 5 August 2006' [Casas sin terminar, parte de una promoción municipal de 1.000 viviendas paralizada. La financiación se consignó en 1998 y la construcción empezó en 2003. Los funcionarios y un político dieron varias razones para la paralización del proyecto: escasez de agua, robo de materiales, problemas con la evacuación de aguas residuales, problemas causados por el alto contenido de arcilla del suelo y escasez de fondos. En agosto de 2006 se habían terminado 420 viviendas, Lady Grey, Cabo Oriental, 5 de agosto de 2006] 2006 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'Incomplete houses, part of a stalled municipal development of 1,000 houses. The funding allocation was made in 1998, building started in 2003. Officials and a politician gave various reasons for the stalling of the scheme: Shortage of water, theft of materials, problems with sewage disposal, problems caused by the high clay content of the soil, and shortage of funds. By August 2006, 420 houses had been completed, Lady Grey, Eastern Cape, 5 August 2006' [Casas sin terminar, parte de una promoción municipal de 1.000 viviendas paralizada. La financiación se consignó en 1998 y la construcción empezó en 2003. Los funcionarios y un político dieron varias razones para la paralización del proyecto: escasez de agua, robo de materiales, problemas con la evacuación de aguas residuales, problemas causados por el alto contenido de arcilla del suelo y escasez de fondos. En agosto de 2006 se habían terminado 420 viviendas, Lady Grey, Cabo Oriental, 5 de agosto de 2006] 2006](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/13.jpg)

![David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'The dethroning of Cecil John Rhodes, after the throwing of human feces on the statue and the agreement of the university to the demands of students for its removal, the University of Cape Town, 9 April 2015' [El derrocamiento de Cecil John Rhodes después de arrojar heces humanas contra la estatua y de que la universidad accediera a las demandas de los estudiantes para su retirada, Universidad de Ciudad del Cabo, 9 de abril de 2015] 2015 David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018) 'The dethroning of Cecil John Rhodes, after the throwing of human feces on the statue and the agreement of the university to the demands of students for its removal, the University of Cape Town, 9 April 2015' [El derrocamiento de Cecil John Rhodes después de arrojar heces humanas contra la estatua y de que la universidad accediera a las demandas de los estudiantes para su retirada, Universidad de Ciudad del Cabo, 9 de abril de 2015] 2015](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/14.jpg)

![Samuel Baylis Barnard (English, 1841-1916) 'Hottentott S. Africa [Portait of /A!kunta]' South Africa, early 1870s Samuel Baylis Barnard (English, 1841-1916) 'Hottentott S. Africa [Portait of /A!kunta]' South Africa, early 1870s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/011_twcpress_barnard-web.jpg?w=655&h=919)

![William Moore (attr.), 'Macomo and his chief wife [Portrait of Maqoma and his wife Katyi]' South Africa, c. 1869 William Moore (attr.), 'Macomo and his chief wife [Portrait of Maqoma and his wife Katyi]' South Africa, c. 1869](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/017_twcpress_moore-web.jpg?w=489&h=789)

You must be logged in to post a comment.