Exhibition dates: 3rd October – 3rd November 2013

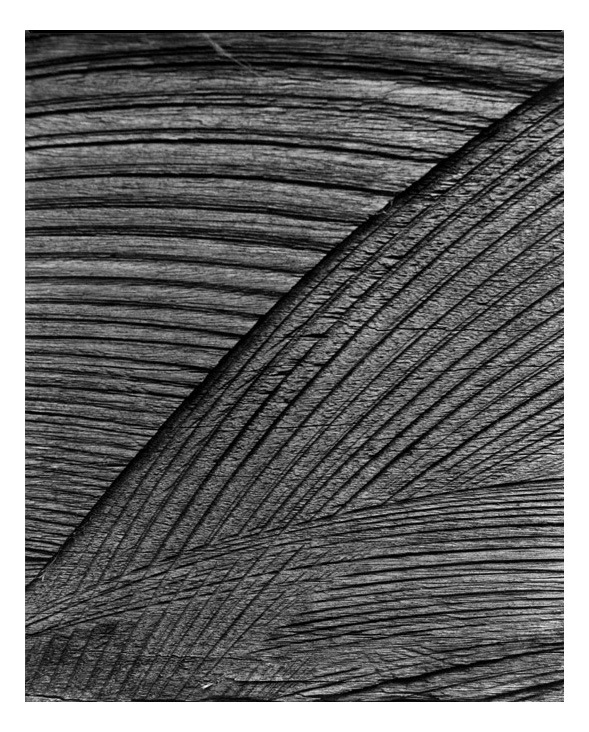

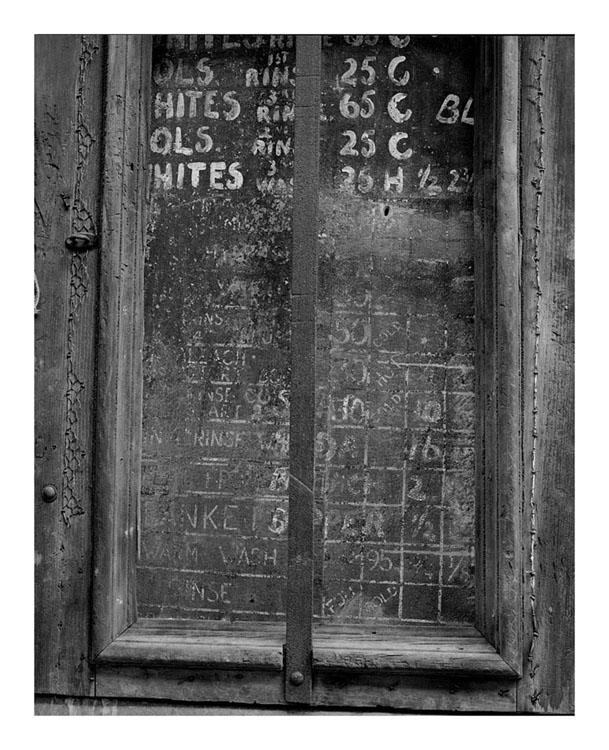

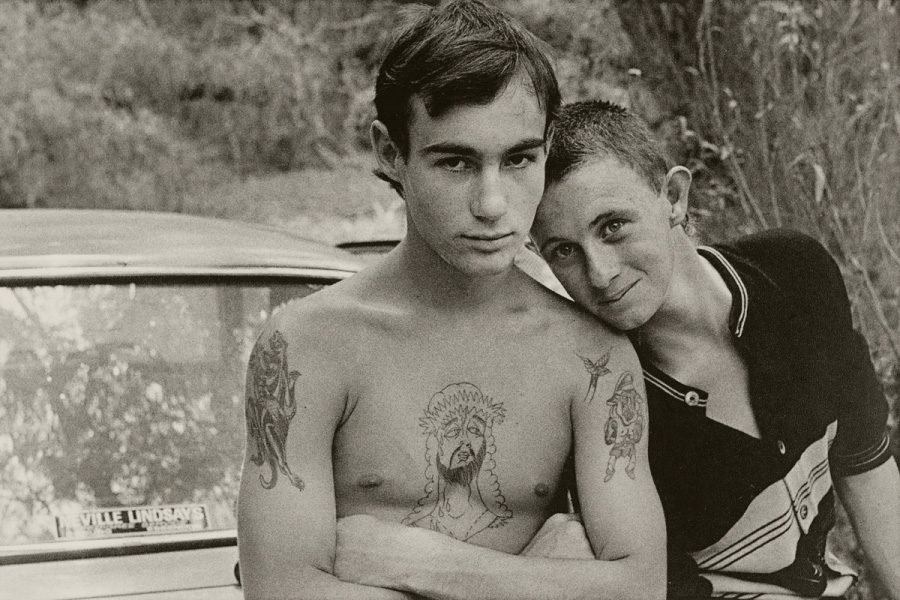

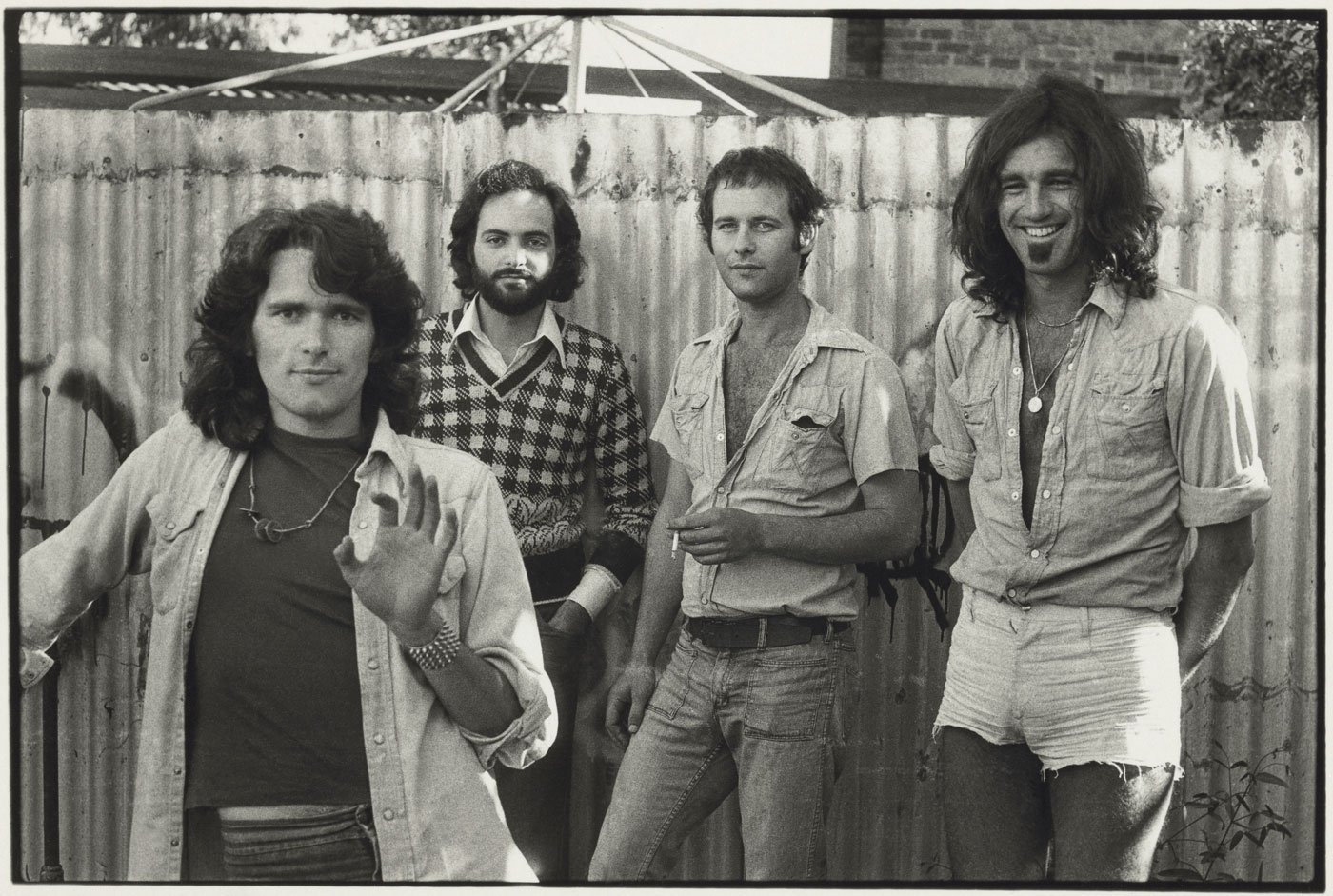

Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019)

Wilcannia, New South Wales

1990

Silver gelatin photograph

© Joyce Evans

At close range

This exhibition at the Monash Gallery of Art features the series Edge of the road by Melbourne photographer Joyce Evans. It is an intense, if less than fully successful, presentation of a body of work completed between 1988 and 1996. The photographs were made with a Widelux F7 35mm panoramic camera, a camera that has a rotating fixed focus lens (see images of the camera below). Rather than the normal horizontal panoramic orientation, Evans has mostly used the camera in a vertical orientation to shoot these images. At the same time she has twisted the camera along unfamiliar axes, sometimes on a diagonal line, which has produced unexpected distortion within the final images.

Evans professed aim in her artist statement (below) is to let go of control of what is captured by the camera, to let go of some previsualisation (what the photographer imagines that they want the photograph to be in their mind’s eye before they press the shutter) and rely on a certain amount of planning and chance. She cites the example of the American photographer Minor White (1908-1976) who popularised the idea of previsualisation as a means of aesthetically controlling the outcome of what the camera captures. Evans wants little of this and sees her photographs as using the camera’s inherent capabilities to image the minutiae of the world, using “the camera’s capacity to see detail, which in the 60th of a second of the firing of the shutter my subconscious may perceive, but may not fully know.” In this sense, the artist is appealing to Walter Benjamin’s idea of film serving as an optical unconscious, a medium that captures everyday objects of ordinary experience which are revealed as strange and unsettling, a “different” nature presenting itself to the camera than to the naked eye.1 As Richard Prouty has noted, “Film changed how we view the least significant minutiae of reality just as surely as Freud’s Psychopathology of Everyday Life changed how we look at incidental phenomenon like slips of the tongue.”2

This enrichment of human perception by a scientific technology, the camera, happens at a level below human recognition, for although the retina frequently receives these aspects, they are not transformed into information by the perceptive system.3 “These new technical images helped discover hitherto unknown – ie. unacknowledged and analysed by perception and therefore restricted to the space of the unconscious or, as he [Benjamin] called it, of an “optical unconscious” – movements and dimensions of reality.”4 In other words, these new technical images may include information that was not retained, processed or even intended by the operator (hence the hoped for serendipity of the images). These images then surprise with the unexpected. As François Arago has observed, “When observers apply a new instrument to the study of nature, what they had hoped for is always but little compared with the successions of discoveries of which the instrument becomes the source – in such matters it is on the unexpected that one can especially count.”5 This is evidenced in Evans photographs through the POTENTIAL of chance. Not chance itself, but the potential of chance of the optical unconscious (of film) to capture something unexpected.

I must disagree with Evans, however, about the photographic process of Minor White and the process of “letting go” that she proposes to adhere to in this body of work. In fact, I would go so far as to invert her rationalisation. Having studied the work of Minor White and visited his archive at Princeton University Museum of Art I understand that previsualisation was strong in White’s photographs, but there was an ultimate letting go of control when he opened the shutter to his camera. In meditation, he sought a connection from himself to the object, from the object back through the camera to form a Zen circle of connection which can be seen in one of his famous Canons: “Let the Subject generate its own Composition.” Then something (spirit?) might take over. This is the ultimate in paradoxical letting go of control for a photographer – to previsualise something, to see it on the ground glass, to capture it on film, to then print it out to find that there is something amorphous in the negative and in the print that you cannot quite put your finger on. Some indefinable element that is not chance, not the unexpected, but spirit itself. Evans photographs are not of this order.

What these photographs are about is an intimate view of the land and our relationship to it, an examination of something that is very close to the artist, but evidenced through the subjectivity of the artist’s control and the objectivity of the cameras optical unconscious. They are shot “at close range,” the picture being taken very close (both physically and psychologically) to the person who is taking the photograph. In their multifaceted perspectives – some images, such as Flood on Murray River on Wodonga side, Victoria (1996) have double horizon lines – the viewer is immersed in the disorientating sweep of the landscape. The photographs become almost William Robinson-esque in their panoramic distortion of both time and space. For example, the descent from the light of the trees, to ferns, to the mulch of paleontological existence in Mount Bulla Ferns, Victoria (1996, below) is particularly effective, as is the booted front prints of Anzses Trip, Talaringa Springs, Great Victorian Desert, South Australia (1993, below). The transition of time is further emphasised by the inclusion of the film sprocket holes in some of the works, such as Pine Barbed Wire Fence and Orchard, Tyabb, Mornington Peninsula (1992, below). However, out of the thirteen photographs presented from the series some photographs, such as Bin, Toorak, Victoria (1990, below) simply do not work, for the image is too didactic in its political and aesthetic definition.

At their best these photographs capture an intensity that is at the boundary of some threshold of understanding (edge of the road, no man’s land, call it whatever you will or the artist wills) of our European place in this land, Australia. There are no bare feet on the ground, only booted footprints, barbed wire, gravel roads, dustbins, tyre tracks and hub caps. The reproductions do not do the work justice. One has to stand in front of these complex images to appreciate their scale and impact on the viewer. They resist verbal description, for only when standing in front of the best of these images does one observe in oneself a sense of disorientation, as though you are about to step off the edge of the world. They do not so much attempt to capture the energy of the landscape but our fragmented and possessive relation to it.

Ultimately, Evans photographs are highly conceptual photographs. Despite protestations to the contrary her photographs are about the control of the photographer with the potential of chance (through the recognition of the process of the optical unconscious of the camera) used knowingly by the artist to achieve the results that she wants. They are about the control of humans over landscape. Evans knows her medium, she knows the propensities of her camera, she plans each shot and despite not knowing exactly what she will get, she roughly knows what they results will be when she tilts the lens of her camera along different axes. These are not emotionally evocative landscapes but, because of the optical unconscious embedded in their construction, they are intimate, political statements about our relationship to the land.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Marcus was a friend of Joyce Evans OAM (1929-2019). Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Footnotes

1/ Prouty, Richard. “The Optical Unconscious,” on the One-Way Street blog, October 16th 2009 [Online] Cited 20th October 2013. No longer available online

2/ Ibid.,

3/ Flores, Victor. “Optical unconscious,” on the Fundação Côa Parque website [Online] Cited 20th October 2013. No longer available online

4/ Ibid.,

5/ Arago, Francois. “Rapport sur le daguerréotype,” in AA.VV. Du Bon Usage de la Photographie: une anthologie de textes. Paris: Centre National de la Photographie, 1987, p. 14 quoted in Flores, op. cit.,

Many thankx to Joyce Evans and Monash Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

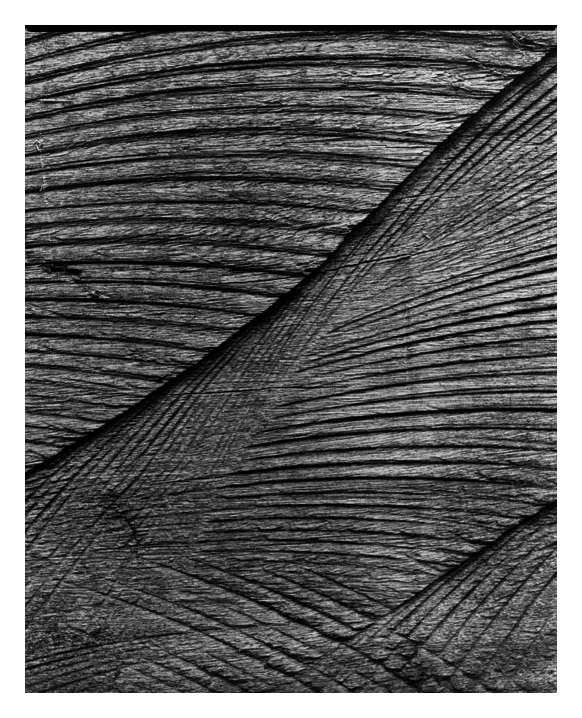

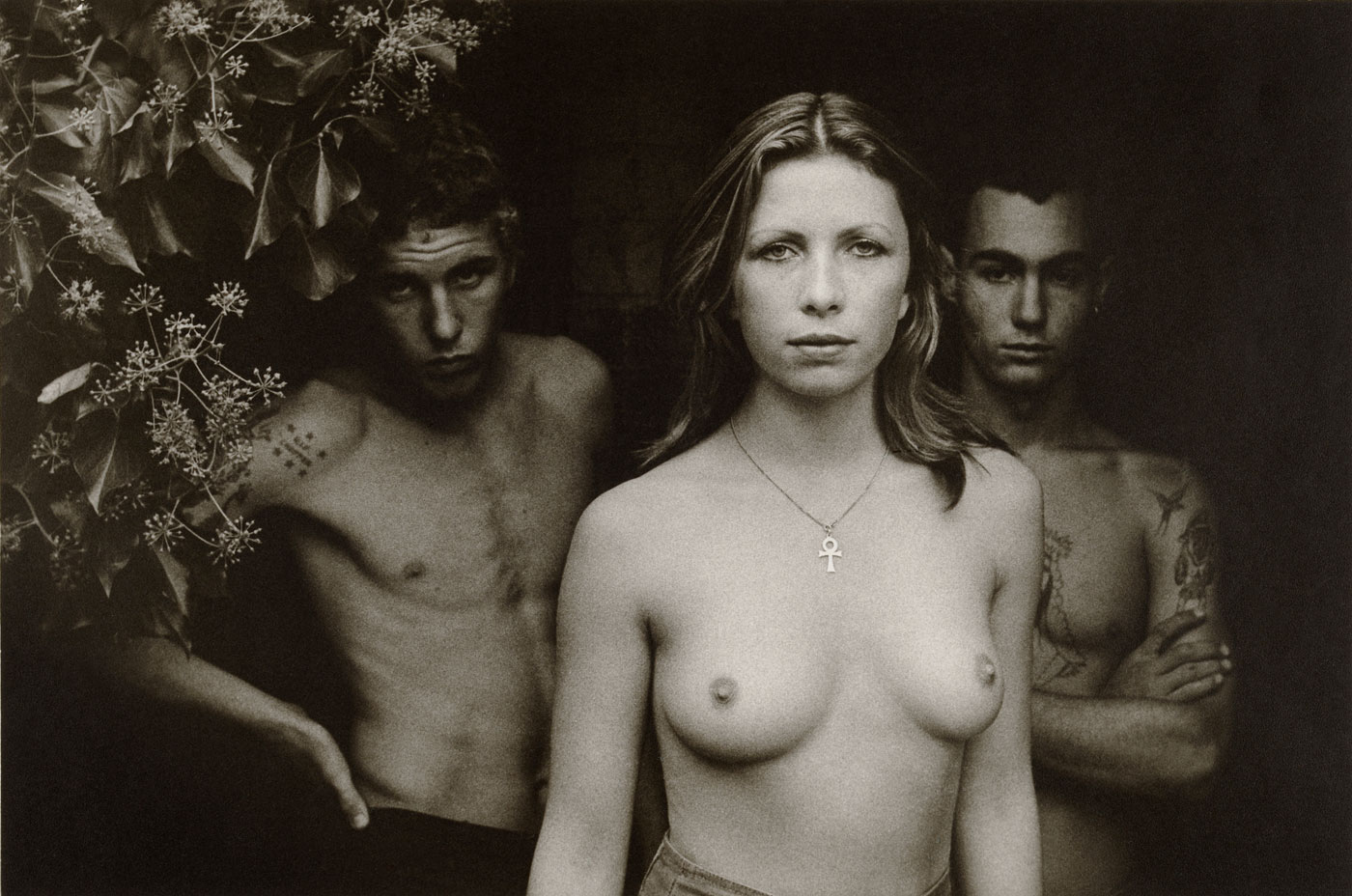

Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019)

Wilcannia, New South Wales

1990

Silver gelatin photograph

© Joyce Evans

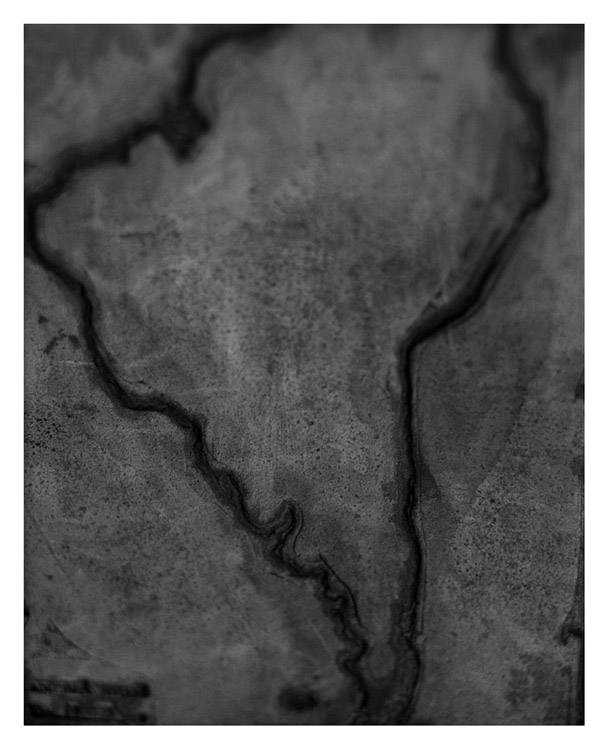

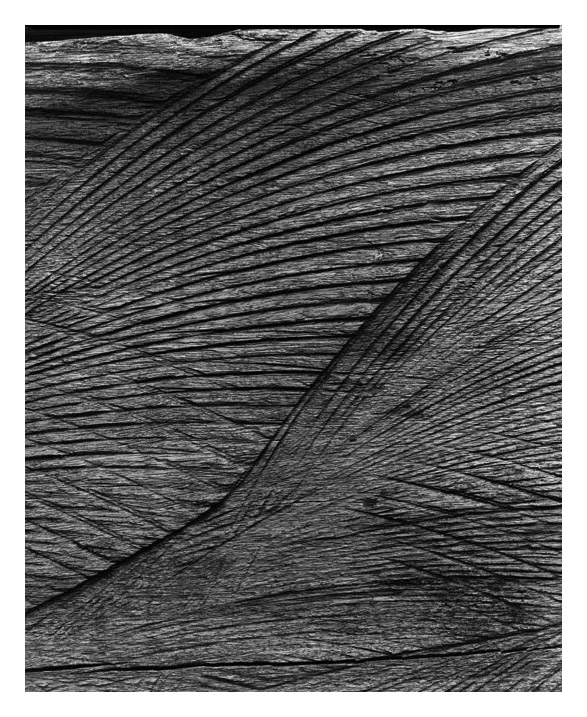

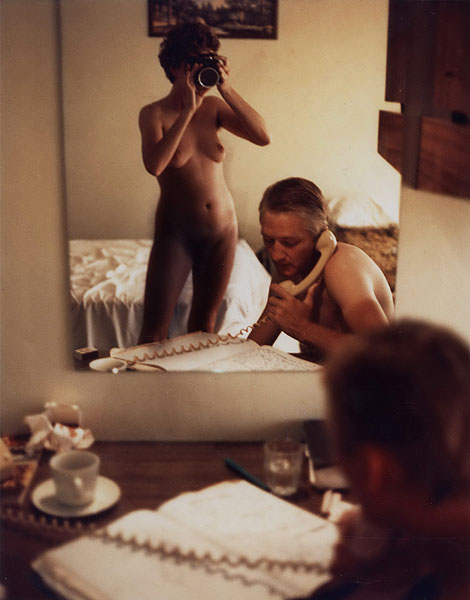

Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019)

Holden, Victoria

1990

Silver gelatin photograph

© Joyce Evans

“Evidenced in these photographs is one of the things that attracted me to photography – namely, its ability to capture the millisecond. While there are many schools of photography, the one popularised by the American photographer Minor White (1908-1976) suggests that the photographer pre-visualises the image prior to pressing the shutter. In other words, the photographer is in control and is the controller of what is captured by the camera. In terms of the resolution of the final image this is technically an important concept. However aesthetically, I enjoy the camera’s capacity to see detail, which in the 60th of a second of the firing of the shutter my subconscious may perceive, but may not fully know.

This appreciation of aesthetics goes back to my university days in 1969-1971 when I did a degree in fine arts at Sydney University. Here the ability to deconstruct imagery was passed on to us by Dr Anton Wilhelm and the understanding of the limits and potentials of two-dimensional imagery (with constant reference to the picture plane), was demonstrated by Professor Bernard Smith. This understanding was further enhanced when I painted at the Bakery Art School in Sydney, 1977-1978. Studying under the inspiring tutelage of John Olsen (b.1928) he made me aware of the power of the edge of the image to relate to what was not shown in the image.

This awareness is reflected in the exhibition through my fascination with, and imaging of, the Edge of the Road, that no man’s land which has a rarely noticed life of its own. I use the 180 degree vista of the Widelux camera, with its ability to capture elongated elements of the landscape, to conceptually explore the lack of control that is offered by the camera. The results are serendipitous: the cigarette butts, the spiders home, the intruding foot, the fecund compost under snow laden ferns. All of these elements combine with the time freeze of the camera to image places of survival and change.

While the images may not be fully visualised they rely on both planning and chance. I choose to point the camera at the subject and let the ‘snap’ of the shutter do the rest. The images that emerge from the flow of time are images that I have imagined in my mind but which the camera has interpreted through an (ir)rational act: the fixity of the image frame challenged by the very act of taking the photograph at the edge of consciousness. As such they ask the question of the viewer: what exactly is being imaged and did it really exist in the first place?”

Joyce Evans with Dr Marcus Bunyan

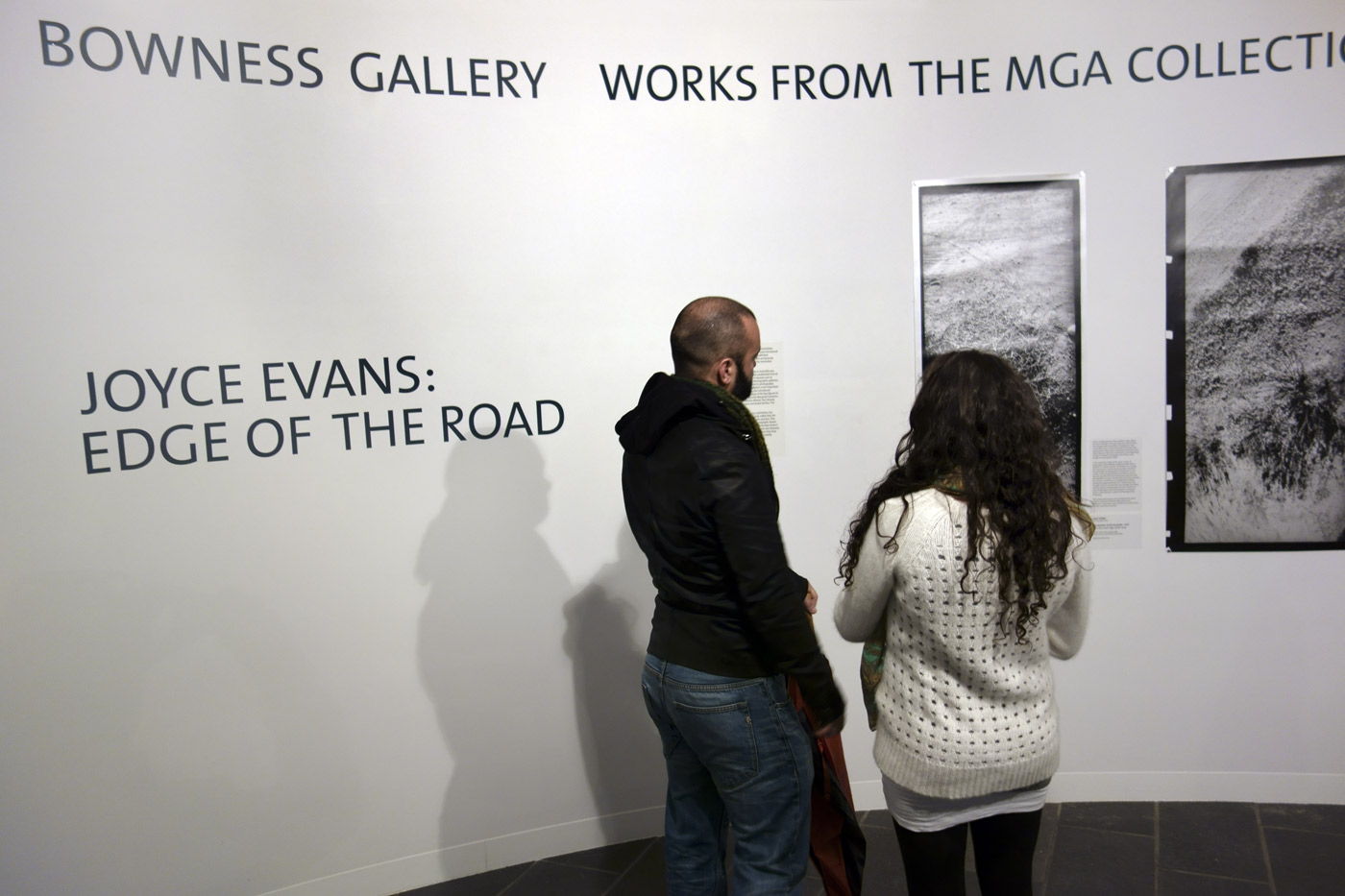

Joyce Evans Edge of the road installation photographs and artist talk at Monash Gallery of Art showing in the bottom image, Shaune Lakin, Director of the Monash Gallery of Art, speaking to the assembled

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Two views of the Widelux F7 camera

Shaune Lakin, Director of the Monash Gallery of Art, speaking to the photographer Joyce Evans OAM (Australian, 1929-2019)

Photo: Jason Blake

Joyce Evans [OAM, Australian, 1929-2019] has been a key figure in Australian photography for many decades. As a gallerist, Evans introduced audiences to the work of many young and established photographers, and as a photographer she has assiduously documented the Australian landscape and the Australian cultural scene.

Evans’s initial contribution to photography in Australia was largely as an advocate for the medium. She established Church Street Photographic Centre in 1976, which became one of Australia’s most significant commercial photographic galleries. Church Street encourage a broad interest in photography and assisted the careers of many of Australia’s most important photographers. At Church Street. Evans also introduced Melbourne audiences to the work of many of the key figures in international photography, including Julia Margaret Cameron, Eugène Atget, Alfred Steiglitz, Berenice Abbott, Paul Strand, Brett Weston, Henri Cartier-Bresson and André Kertész.

Evans devised to become a photographer well before she opened Church Street. But it was in the early 1980s that she began to focus more productively on her own practice. This exhibition includes a selection of colour photographs drawn from the MGA Collection, each of which demonstrates Evans’s quite formal interest in landscape. The exhibition mainly features the series Edge of the road, large panoramic prints that have only rarely been exhibited and which reflect a decidedly different photographic relationship to landscape.

Evans’s landscapes are often political. They reflect her keen interest in the way that we relate to land, and engage with the politics of Indigenous land ownership. Evans is also interested in the way that landscape has featured in Australian art history, and often draws on the work and lessons of the legendary painter of abstract landscapes John Olsen, who taught her during the 1960s.

A fine example is Edge of the road, a series of landscapes made between 1988 and 1996 with a Widelux F7 35mm camera. The Widelux is a swing-lens panoramic camera which provides only basic functionality. Its rotating lens is fixed focus at 3.3 metres. Evans embraced these limitations, and in fact played with them by introducing chance to the photographic process. During exposure Evans twisted her camera, sometimes on a diagonal line which produced unexpected distortion. Rather than the straight vertical or horizontal axis usually associated with panoramic photographs, the axis of some of these landscapes chops and changes. In doing so, Evans is attempting to capture the energy of the landscape. These large panoramas were printed by the artist and her assistant Christian Alexander in her darkroom.

Wall text from the exhibition

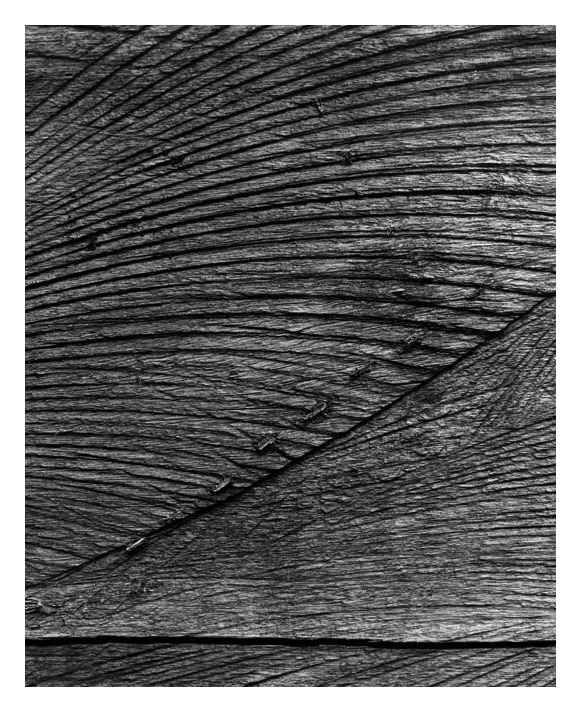

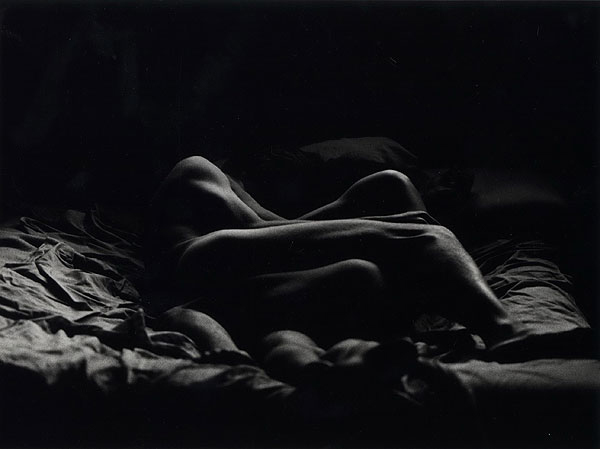

Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019)

Bin, Toorak, Victoria

1990

Silver gelatin photograph

© Joyce Evans

Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019)

Anzses Trip, Talaringa Springs, Great Victorian Desert, South Australia

1993

Silver gelatin photograph

© Joyce Evans

Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019)

Pine Barbed Wire Fence and Orchard, Tyabb, Mornington Peninsula

1992

Silver gelatin photograph

© Joyce Evans

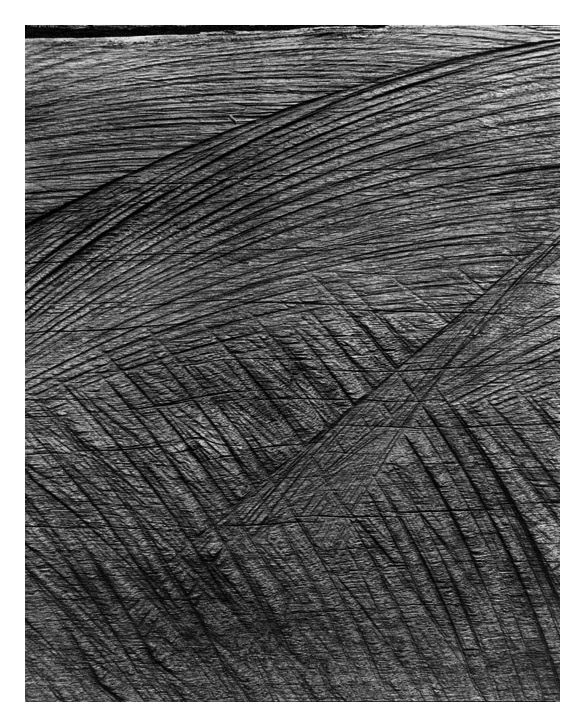

Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019)

Mount Bulla Ferns, Victoria

1996

Silver gelatin photograph

© Joyce Evans

Monash Gallery of Art

860 Ferntree Gully Road, Wheelers Hill

Victoria 3150 Australia

Phone: + 61 3 8544 0500

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 10am – 5pm

Saturday – Sunday 10am – 4pm

Closed Mondays

![Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980) 'Butterfly behind glass [Red Symons from Skyhooks]' 1975 Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980) 'Butterfly behind glass [Red Symons from Skyhooks]' 1975](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/butterfly_174882_web.jpg)

![Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980) 'Performers on stage,' Hair', Metro Theatre Kings Cross, Sydney, January 1970 [Jim Sharman Director cast included Reg Livermore]' 1970 Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980) 'Performers on stage,' Hair', Metro Theatre Kings Cross, Sydney, January 1970 [Jim Sharman Director cast included Reg Livermore]' 1970](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/jerrems_performers-on-stage-hair-web.jpg?w=650&h=818)

You must be logged in to post a comment.