Exhibition dates: 25th September – 22nd November 2015

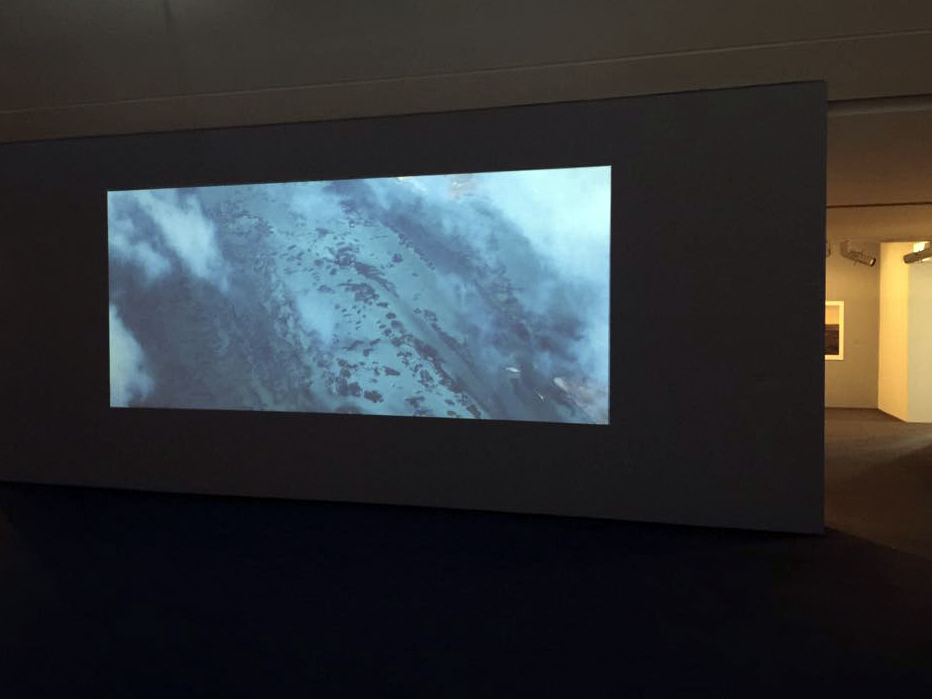

Installation photograph of the William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize 2015 at the Monash Gallery of Art

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Reality, passing

In terms of the professional quality of work, the pristine printing and framing, and the “less is more” nature of the hang, this is the best William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize I have seen at the Monash Gallery of Art. The surprise about the nature of this year’s finalists is the surfeit of landscape work and the weakness of the portrait photographs. Key words when looking at the landscape work are: the sublime, internal terrain, elision, fear, darkness, constructed landscapes, aesthetic hyper reality, unreachable worlds, presence and absence, layering, pigment prints.

There is a heavy sense of un/reality about all of the landscape work, as though there is no such thing as the unmediated, straight landscape photograph any more. Reality passes (passing itself off for something else), and the viewer is left to tease out what is constructed (or not), how many layers (both mental and physical) are involved, and what the possible outcomes might be. In this post-landscape photography even straight digital photographs or analogue photographs of the landscape take on this desiccated view complete with surface flatness and “air” of unreality.

For example, look at Murray Fredericks’ North Stradbroke (2014), Silvi Glattauer’s Altiplano 1 (2015) Anne Algar’s Eruption (2015) and numerous others throughout the exhibition. These places exist in real life yet feel so un/real in these photographs – through scale, through colour, through surface – that you are left wondering what’s it all about. There is certainly no link to traditional notions of the sublime and little connection to the elemental (as in the object as itself). As I have said before about contemporary photography, these photographs are all about the photographers ideas and desires, not about the world itself. The photographs are flat are rather uninteresting with no depth of feeling or ambiguity of meaning. I found it hard to get excited about any of the landscape photographs.

And when photographers do use traditional techniques, such as black and white printing, silver gelatin prints or the analogue / digital combo, the results are similarly underwhelming. It is as if the aesthetic of the digital realm, this aesthetic hyper reality, has taken over how people use analogue photography as well. Robert Ashton’s Opening (2015) (analogue/digital), David Bibby’s Untitled #1 (2014) (black and white digital) and Virginia Cummins’ Gone tender, river’s edge (2015) (silver gelatin print) all evidence this cut-up, layering, obscure non-seeing where the magic of the traditional print has been lost.

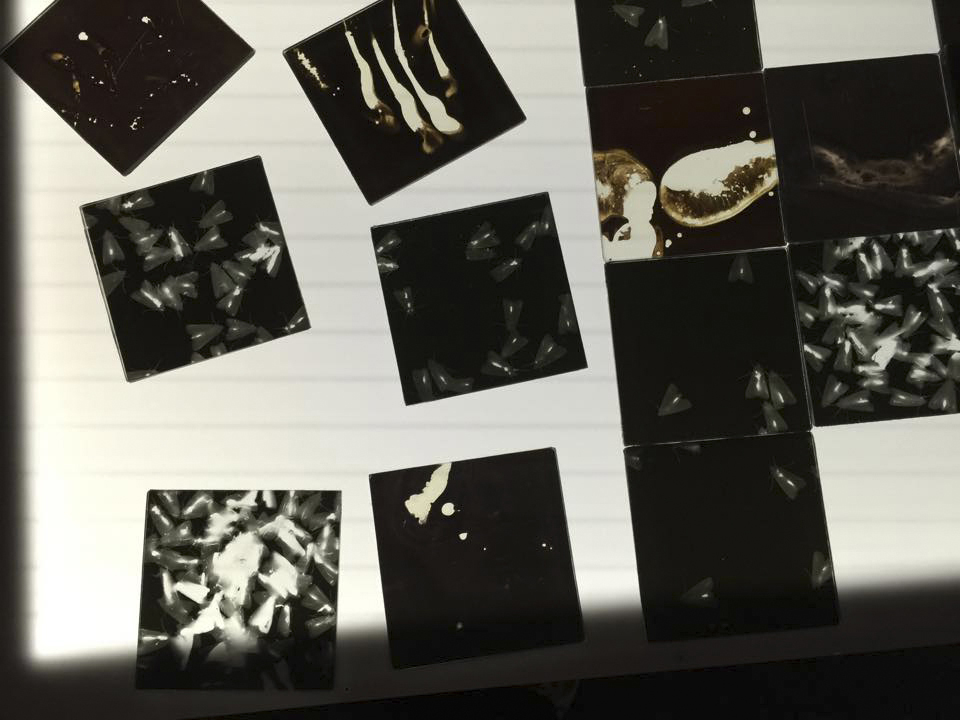

Another surprise to me was that the two works that I found most successful in the exhibition were two of the most heavily conceptual. These images were both beautiful and intellectually stimulating. Brook Andrew’s Possessed II (2015) left me wondering about the original slides, marvelling at the technique used to create the image and wanting to see the rest of the series and interrogate further the artist’s background and “the tradition of the psychological in depiction and stories of the Australian alien landscape.” There was ambiguity and feeling here!

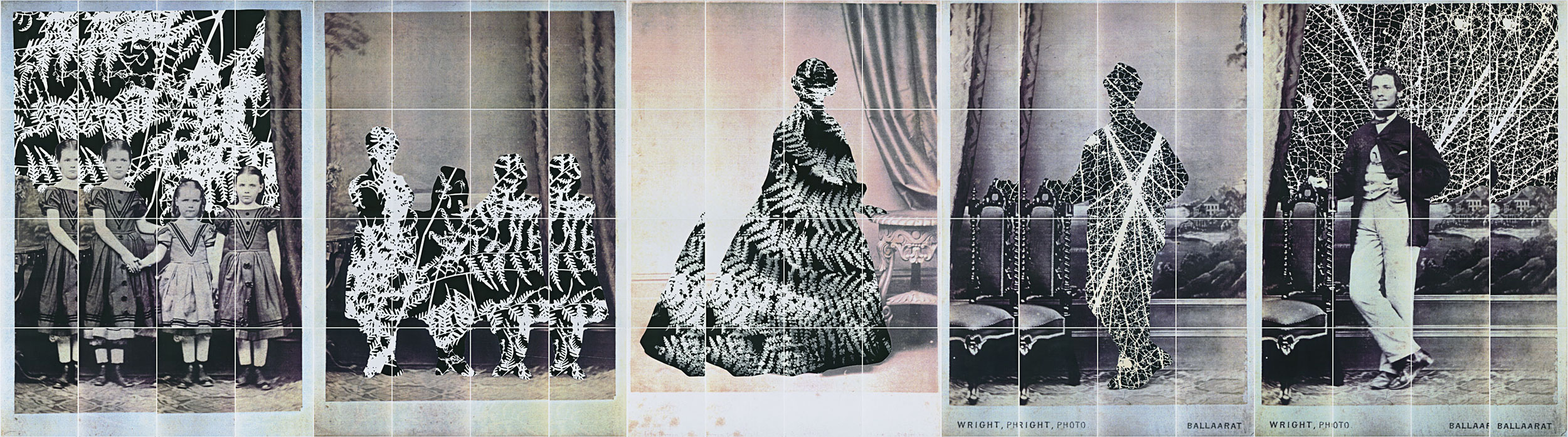

The work that I thought should have won was Peta Clancy’s She carries it all like a map on her skin (2014-2015). I have always liked Clancy’s work for there is so much sensitivity to subject matter embedded in her work. Clancy probes the boundaries of the photograph and the skin through punctures made using a fine silver needle to create a lace-like effect or ‘internalised landscape’ which is visible from both the emulsion and non-emulsion sides of the print. She then re-photographs the photograph and punctures the print again, the print becoming a palimpsest of punctures, of wounds, of the journey of life (with the needles link to woman’s work and the lips relation to desire). The installation of the work then emphasises the physicality of the print, Clancy “activating the materiality of the photographic medium by exploring photographs in terms of what the image content depicts as well as three-dimensional objects that exist in space and time.” Such a wonderfully tactile, sensual and conceptual work of negative / positive, presence / absence that kept drawing me back to hidden worlds.

As for the winner, Joseph McGlennon’s Florilegium #1 (2014), according to gallery staff some people love it and some people don’t. I am of the latter camp. The photograph is beautiful and “pretty” in a superficial, constructed way but flat like a piece of Florence Broadhurst wallpaper in another. Basically it’s an illustrated plate from a 19th century colour plate book made out of multiple negatives and digitally rendered. These images are taken in the exotic locations of Madagascar, Tahiti and Singapore and one could apply the critique of “Orientalism” to this piece of work… the proposal of lush landscapes and unreachable worlds as ‘Other’ – the imitation or depiction of aspects in Middle Eastern, South Asian, African and East Asian landscapes and cultures evidenced by a patronising Western attitude towards them. Further, photographs such as Valerie Sparks’ Le vol 1 (2014) imagine this exotic ‘Other’ by pasting taxidermy birds into “hybrid” (in other words, artist made) environments, while work such as Carolyn Young’s Reference grassy woodland: spring (Bookham) (2014) topographically map a uniform, constructed, imagined terrain of becoming that will never exist.

Most of the landscape work could be associated with a de-territorialization and re-territorialization of meaning across locations and through technologies (Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis and London: University of Minneapolis Press, 1987), where moments of connectivity and the assemblages that form them, “are the processes by which various configurations of linked components function in an intersection with each other, a process that can be both productive and disruptive. Any such process involves a territorialization; there is a double movement where something accumulates meanings (re-territorialization), but does so co-extensively with a de-territorialization where the same thing is disinvested of meanings.”1 Unfortunately in this exhibition, the intensification of these processes around a particular site through a multiplicity of intersections in these landscape photographs, are mostly dead ends. They lead nowhere of much interest and they fail to speak to me, which is what I want art to do.

What I have picked up from all this viewing is another couple of insights. It’s a sad state of affairs to see “Collection of the artist” on most of these works. Hardly a single one is in a collection. It’s difficult to be a contemporary photographic artist in Australia. You will make no money at it, even if you are represented by commercial gallery for, unlike America, there are simply not the collectors in Australia for the art of contemporary photography. Even as I critique the work, I admire the artist’s for producing it, for I know the cost, courage and dedication needed to keep making work that hardly ever gets purchased.

And secondly, all of these “pigment” prints. A pigment is a colouring matter or substance which when suspended in a liquid vehicle becomes a paint, ink, etc. or whose presence in the tissues or cells of animals or plants colours them. In other words, it is an additive which has no real body of its own. No wonder all of these pigment prints look so flat and have the feeling of a lack of depth. Show me a Stephen Shore original photograph and I will show you more presence than all of these digital prints put together.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,220

1/ Wood, Aylish. “Fresh Kill: Information technologies as sites of resistance,” in Munt, Sally (ed.,). Technospaces: Inside the New Media. London: Continuum, 2001, p. 166.

Many thankx to the Monash Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. All photographs © Marcus Bunyan and the Monash Gallery of Art. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation photographs of the William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize 2015 at the Monash Gallery of Art

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Peta Clancy (Australian, b. 1970)

She carries it all like a map on her skin

2014-2015

From the series Punctures

Chromgenic prints

55 x 80cm (each)

Reproduction courtesy of the artist

The series Punctures which explores skin, mortality and ageing expands on my long-term preoccupation with probing the boundaries of the photograph and the skin. Comprised of images of a woman’s lips punctured with a fine silver needle to create a lace-like effect or ‘internalised landscape’ and visible from both the emulsion and non-emulsion sides of the print. I am interested in activating the materiality of the photographic medium by exploring photographs in terms of what the image content depicts as well as three-dimensional objects that exist in space and time.

Installation photographs of Peta Clancy’s She carries it all like a map on her skin (2014-2015)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

In 2006 the MGA Foundation established the William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize to promote excellence in contemporary Australian photography. The annual $25,000 non-acquisitive William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize is an initiative of the MGA Foundation.

MGA Senior Curator, Stephen Zagala was joined by two of Australia’s most notable art world figures, Bill Henson and Karen Quinlan, to select the finalists for this year. The prize is open to any Australian photographer, whether amateur or professional, and all genres of photography are eligible, provided that the work has been produced in the last 12 months. Each year a panel of three judges considers hundreds of entries and curates an exhibition of finalists, before settling on a single winner.

The panel selected the shortlist of 47 works to be exhibited, and will convene again when the exhibition has been installed to choose a winner, which will be announced on Thursday 1 October. Bill Henson said of the selection process: ‘In the end, it really just comes down to how compelling I find a work to be. Matters of subject, issue or agenda have to find a form which is their equal for without that we’re left with something that simply holds no interest for us.’

Finalists: Anne Algar, Brook Andrew, Robert Ashton, Svetlana Bailey, Del Kathryn Barton, Clare Bedford, David Bibby, Devika Bilimoria, Frederico Câmara, Peter Campbell, Danica Chappell, Che Chorley, Peta Clancy, Virginia Cummins, Rebecca Dagnall, Cherine Fahd, David Flanagan, Murray Fredericks, Silvi Glattauer, Wayne Grivell, Molly Harris, Kern Hendricks, Lyndal Irons, Mark Kimber, Courtney Krawec, Michael Krzanich, Cathy Laudenbach, Jon Lewis, David Manley, AHC McDonald, Joseph McGlennon, Rod McNicol, Bill Moseley, Ward Roberts, Daniel Shipp, Valerie Sparks, Rodney Stewart, Rebekah Stuart, Ian Tippett, Justine Varga, John Watson, Kim Westcott, Peter Whyte, Amanda Williams, Rudi Williams, Melissa Williams-Brown and Carolyn Young.

On Thursday 1 October Joseph McGlennon was announced as the $25,000 winner of the William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize. Colour Factory Honourable Mentions were awarded to Peter Campbell, Daniel Shipp and Valerie Sparks.

Text from the MGA website

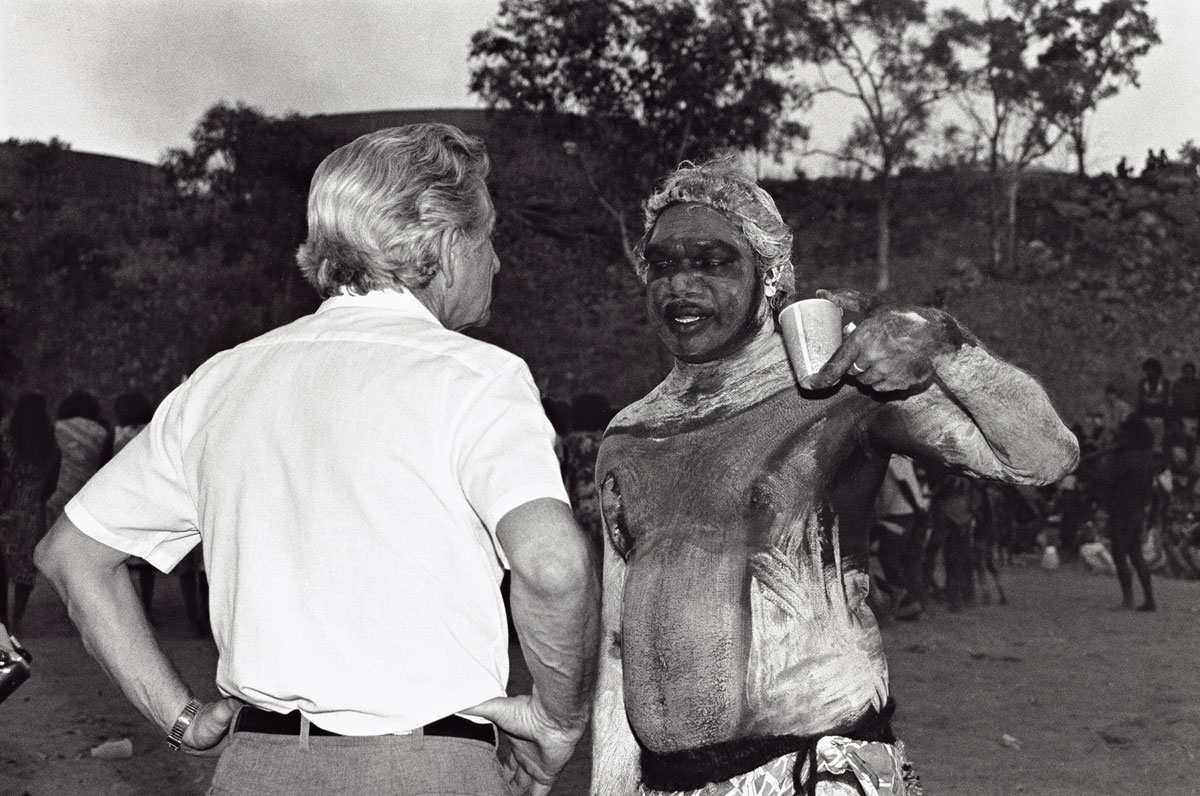

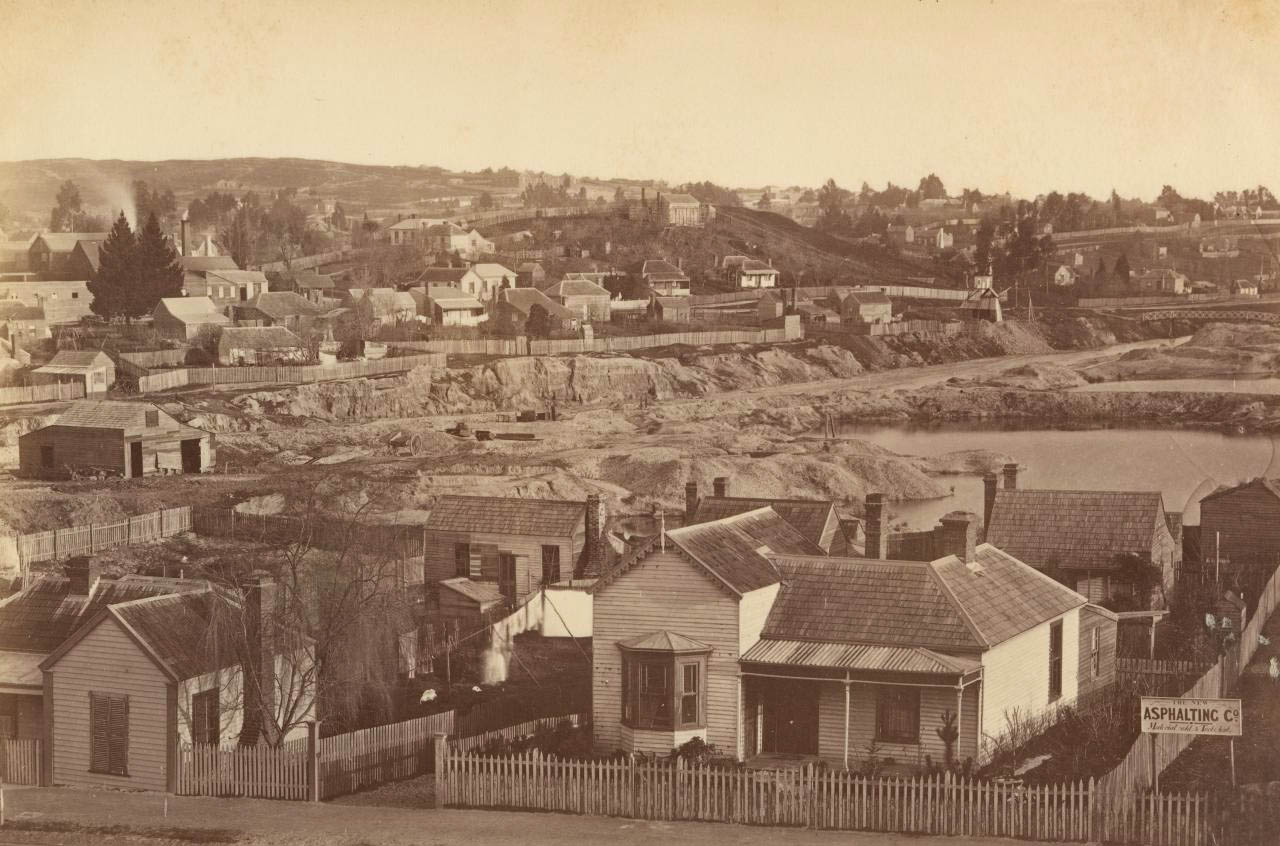

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Possessed II

2015

Gelatin silver print

137 x 127cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist, Tolarno Galleries (Melbourne) and Galerie Nathalie Obadia (Paris and Brussels)

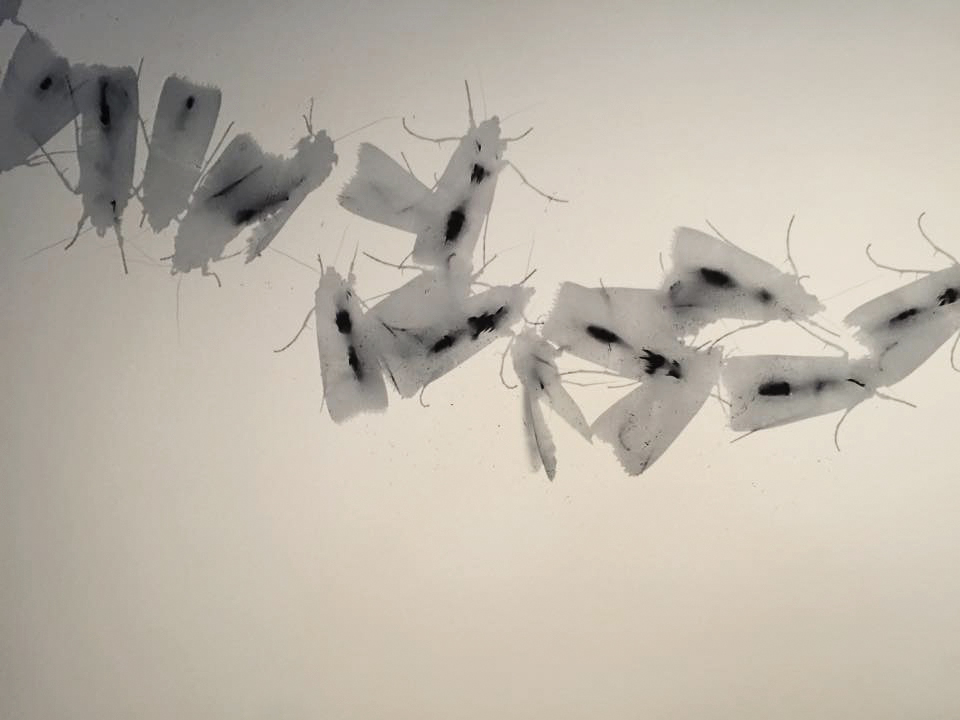

Possessed is a black-and-white photographic series inspired by a rare collection of late 19th-century glass lantern slides depicting images of landscapes from Tasmania and Victoria. Recreated in a trompe l’oeil visual effect – some aspects of this work are akin to Rorschach imagery practice and reference the tradition of the psychological in depiction and stories of the Australian alien landscape.

Robert Ashton (Australian, b. 1950)

Opening

2015

Pigment ink-jet print

60 x 95cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist

I have lived close to the scrubby coastal bush for many years and watched it continually transform through fire, drought and habitation. This landscape can be an unsettling place and I am continually drawn to it, trying to describe the beauty and menace. For these images I have used a 4 x 5 field camera to facilitate a slower and more concise way of working. Looking for the place where the literal meets the abstract. Taking only a couple of exposures, committing to the moment. Embracing the limitations of the medium and letting the result be defined by the practice. As a diptych the images form a complimentary pair. Each distinct but instructing the other, to make a series of fractured dioramas.

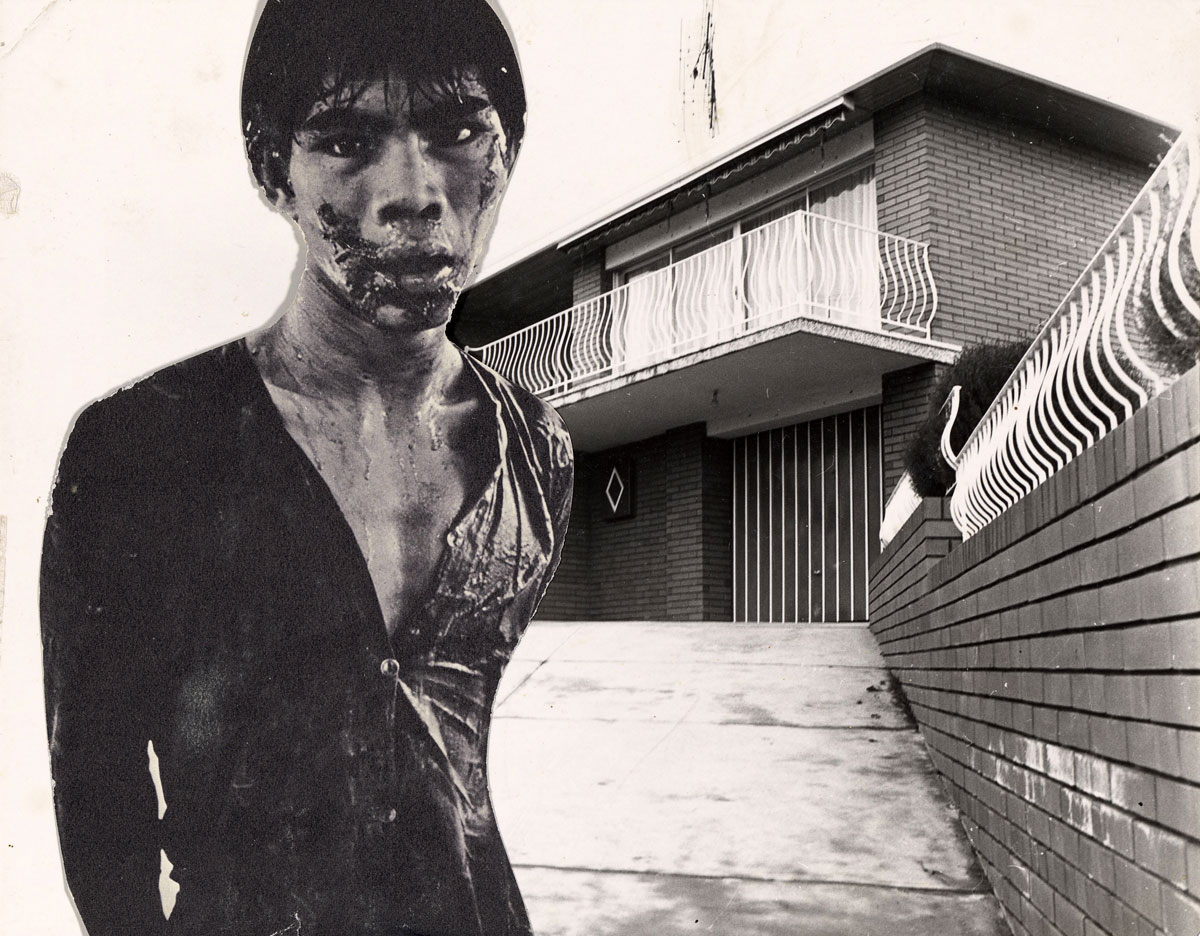

David Bibby (Australian, b. 1970)

Untitled #1

2014

From the series Darkness

Pigment ink-jet print

50 x 75cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist

Fear of dark places gave our ancient ancestors an evolutionary advantage, by priming brains and bodies for a fight-or-flight response when faced with the threat of danger or the unknown. These primal fears also had a strong influence on our cultures. Our fear of darkness and of forests, as dark places that conceal the unknown, has placed them at the centre of many of our myths, legends and folktales.

Despite, or perhaps because of our fear we seem to have an attraction to the darkness and there is something intrinsically beautiful in many dark images. Maybe the darkness has become a refuge in the modern world for those things we can’t control, including mystery and imagination.

Virginia Cummins

Gone tender, river’s edge

2015

From the series Spirit work

Gelatin silver print

70 x 70cm

reproduction courtesy of the artist

This image was shot in remote South Gippsland, where I grew up. It’s part of the Spirit work series, exploring the positive power of nature and how our immersion in this world can move and change us. This work calls on the old-world landscape tradition of Romanticism and the quest for ‘the sublime’. To acknowledge the strength and transformative qualities of nature seems vital right now, in light of society’s blinkered approach to environmental concerns and our preoccupation with communication through technology.

This series was shot with obscure film cameras from the 1950s and 1960s. I enjoy the meditative qualities of traditional photographic practices and the potential for a bit of magic in these revelations.

Rebecca Dagnall (Australian, b. 1972)

Pioneer pool

2015

From the series In the presence of absence – states of being in the Australian landscape

Pigment ink-jet print

100 x 150cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist

There is certain darkness in the Australian imaginary of the landscape that is tangled in a history that holds both a presence and an absence, a knowledge and yet a denial of past colonial deeds. It is as though this history haunts the landscape, like a ‘ghost’ with unfinished business. My current work is an exploration of how the Australian Gothic informs our response to the Australian landscape. The images respond to myths and stories about the landscape that focus on an understanding of the things that we cannot see.

Svetlana Bailey (German born Russia, b. 1984)

Utah

2015

From the series All dreams come true

Pigment ink-jet print

114 x 91cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist

I work with images or artefacts that I find, such as on walls, billboards or shop window displays. They present an alternative reality, and I photograph them with their surroundings, and flatten these two spaces into one. Often the images I find are a montage, creating a reality that never truly existed. I collect them into a personal global album of images created by strangers in response to a common dream. Perhaps their makers considered place and interpreted its environment and beliefs, or were trying to shape our perception of reality. I wonder if these images exist for us or against us, if they beautify our life or mislead us, and if believing in their deception adds to our satisfaction.

Frederico Cãmara (Brazilian, b. 1971)

Sydney Sealife Aquarium, Sydney, Australia

2014

From the series Views of Paradise

Pigment ink-jet print

150 x 120cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist

Views of Paradise is a research project that aims to create a world atlas of the artificial environments of zoos and aquariums, as an investigation on the relations between the zoo and the concepts of paradise, utopia, dystopia and heterotopia. This project signals the possibility of a meaningful existence for the empty zoo, either as image or an actual site, by shifting the viewer’s gaze from the animal to humans, as principal agents in the destruction of the environment, and our failed attempt at its re-creation.

Currently, the focus of this project is Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and New Caledonia), where it will identify the characteristics that are related to this region’s natural and cultural environments.

Murray Fredericks (Australian, b. 1970)

North Stradbroke

2014

From the series Origins

Pigment ink-jet print

90 x 250cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist, ARC One (Melbourne) and Annandale Galleries (Sydney)

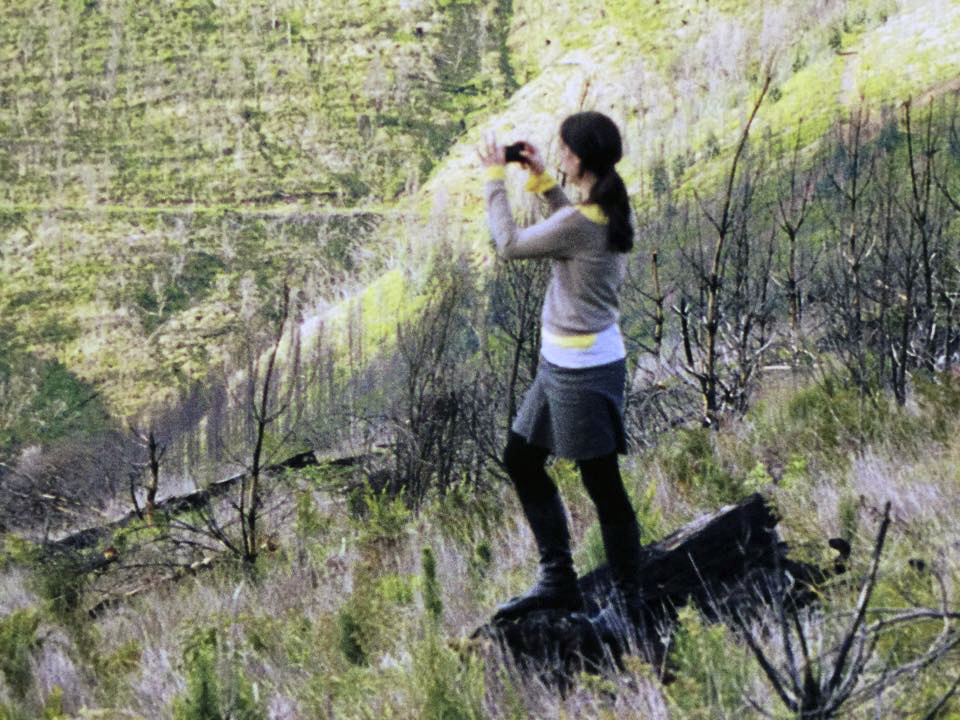

This work is drawn from my current series Origins. In Origins fire has become the central subject, specifically with regards to fire’s place in the social and cultural imagination of Australia. ‘North Stradbroke’ records the scene of a wildfire sparked by lightning, causing holidaymakers to flee their bush campsites under a thunderstorm as it moves up the coast.

Silvi Glattauer (Australian born Argentina, b. 1977)

Altiplano 1

2015

From the series Altiplano

Pigment ink-jet print

100 x 140cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist

A personal narrative of identity that pendulates between Australia and South America. I am drawn to these elusive Altiplanic landscapes as abstract topographical storyboards that read like textural braille. The aesthetic hyper reality that is often associated with classical landscape photography is replaced here with a ‘visual text’.

Anne Algar

Eruption

2015

From the series Night sky

Pigment ink-jet print

60.0 x 90.0cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist

This image reflects my interest in low light landscape and night sky photography. We have scientific knowledge and understanding of the night sky but there is also an emotional element, whereby our human experience of it has no bearing on its material make up. For example many Indigenous Australians refer to the Milky Way as the ’emu’.

For me, there is a certain wonder, excitement and sometimes trepidation when photographing at night. What intrigues me is how objects, vistas and other things, only dimly visible to the human eye in darkness, can be captured in infinite detail by the camera, due to its greater light sensitivity and colour spectrum. It truly does open up another world.

Rebekah Stuart

Dreaming in reverse 2

2014

From the series Pictures of elision

Pigment ink-jet print

102 x 140cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist

I am a contemporary visual artist who explores an alternative aesthetic to the traditional and romantic landscape. Constructing fragments of nature via digital media I create landscapes that do not exist in reality. The images evolve in a similar fashion to painting, over long duration. I build and refine details for a new whole to emerge, disorientating the observer’s position in a subtle way to reflect on their own internal terrain. The landscapes are a reflection of the horizons carried within – an intimate sublime for a time when wilderness is perhaps uninhabitable.

Valerie Sparks (Australian, b. 1960)

Le vol 1

2014

From the series Le vol

Pigment ink-jet print

140 x 229cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY + dianne tanzer gallery (Melbourne)

I am interested in hybrid environments as a reflection of migration as an ongoing natural and cultural occurrence. The birds in this work were photographed at the Vienna and La Rochelle Natural History Museums. These extraordinary collections include birds collected on Cook’s voyages to the Pacific, as well as many collected from South East Asia, Indonesia, Brazil and other South and Central American locations as far back as the mid 1700s. The French term le vol translates as flight, flying, theft or burglary. For the birds in this work, life and flight have been stolen and yet reanimated by the taxidermist. Whereas collecting practices have changed dramatically, the work raises questions about early collecting practices as acts of theft.

Carolyn Young

Reference grassy woodland: spring (Bookham)

2014

From the series Grassy woodlands

Pigment ink-jet print

70 x 84.9cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist and Weswal Gallery (Tamworth)

For a number of years I have been documenting grassy woodlands in NSW and Victoria. Once common, these ecosystems have been reduced to small pockets amongst farmed land, along roadsides, across reserves and in tucked away cemeteries. Responding to ecologists and landholders, I return to the same sites and shoot seasonally. Represented in my photographs are intact (reference) grassy woodlands, and woodlands that have been altered by agriculture. The repetitive still life structure across my photographs highlights the change in plant diversity as land management changes. The images urge viewers to reflect on the past, present and future of these woodlands.

Joseph McGlennon (Australian born Scotland, b. 1957)

Florilegium #1

2014

From the series Florilegium

Pigment ink-jet print

127 x 100cm

Reproduction courtesy of the artist and Michael Reid (Sydney)

A Latin term reconfigured in the Middle Ages; florilegium (to gather flowers), had its early language roots in the gathering together of scholarly church writings, into the one tome. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Botanical Gardens emerged across Europe, privately hoarding exotic world flowers and animals, signalling the rise of the illustrated colour plate book. The growing desire to corral and record the world’s flora and fauna, alongside the growing confidence in science, all fused to produce a notion of the florilegium as a luxurious record of the rare; of important beauties to be viewed in the one vista.

Photographed in Madagascar, Tahiti and Singapore, in ‘Florilegium #1’, I have captured each bird, flower, vine and butterfly and created a florolegium landscape straight from the Age of Enlightenment. There is an enchanting clash of empirical scientific observation coupled with a deep romantically lush and diffused spotlight of compassion for something wild, observed for a brilliant moment before vanishing into the fog of time. This lush landscape dwells in a most complex, beautiful and sadly unreachable world.

$25,000 winner

Monash Gallery of Art

860 Ferntree Gully Road, Wheelers Hill

Victoria 3150 Australia

Phone: + 61 3 8544 0500

Opening hours:

Tue – Fri: 10am – 5pm

Sat – Sun: 10pm – 4pm

Mon/public holidays: closed

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Namandi spirit [Queensland, Australia]' 2002 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Namandi spirit [Queensland, Australia]' 2002](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/tersappen_namandi_spirit_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Cabbage trees [Queensland, Australia]' 2002 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Cabbage trees [Queensland, Australia]' 2002](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_cabbagetrees_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Full moon [France]' 1997 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Full moon [France]' 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_fullmoon_france_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Brazil]' 1991 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Brazil]' 1991](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_mountain_brazil_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Las Palmas, Spain]' 1992 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Las Palmas, Spain]' 1992](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_portugal_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Zion Park [USA]' 1996 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Zion Park [USA]' 1996](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_zion_park_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.