Exhibition dates: 26th April – 14th August, 2017

Curator: Mnam/Cci, Clément Cheroux

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Stamped Tin Relic

1929

Gelatin silver print

23.3 x 28cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris Achat en 1996

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Centre Pompidou / Dist.RMN-GP

The un/ordinariness of ordinariness

What a pleasure.

I’ve never liked the term ‘”vernacular” photography’ because, for me, every time someone presses the shutter of the camera they have a purpose: to capture a scene, however accidental or incidental. That context may lie outside recognised networks of production and legitimation but it does not lie outside performance and ritual. As Catherine Lumby observes, what the promiscuous flow of the contemporary image culture opens up, “is an expanded and abstracted terrain of becoming… whereby images exceed, incorporate or reverse the values that are presumed to reside within them in a patriarchal social order.”1 Pace Evans.

His art of an alternate order, his vision of a terrain of becoming is so particular, so different it has entered the lexicon of America culture.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Lumby, Catharine. “Nothing Personal: Sex, Gender and Identity in The Media Age,” in Matthews, Jill (ed.,). Sex in Public: Australian Sexual Cultures. St. Leonards: Allen and Unwin, 1997, pp. 14-15.

Walker Evans: “The passionate quest to identify the fundamental features of American vernacular culture… the term “vernacular” designates those popular or informal forms of expression used by ordinary people for everyday purposes – essentially meaning all that falls outside art, outside the recognised networks of production and legitimation, and which in the US thus serves to define a specifically American culture. It is all the little details of the everyday environment that make for “Americanness”: wooden roadside shacks, the way a shopkeeper lays out his wares in the window, the silhouette of the Ford Model T, the pseudo-cursive typography of Coca-Cola signs. It is a crucial notion for the understanding of American culture.”

Text from press release

Many thankx to the Centre Pompidou for allowing me to publish the artwork in the posting. Please click on the art work for a larger version of the image.

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Coney Island Beach

c. 1929

Gelatin silver print

22.5 x 31cm

The J.Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

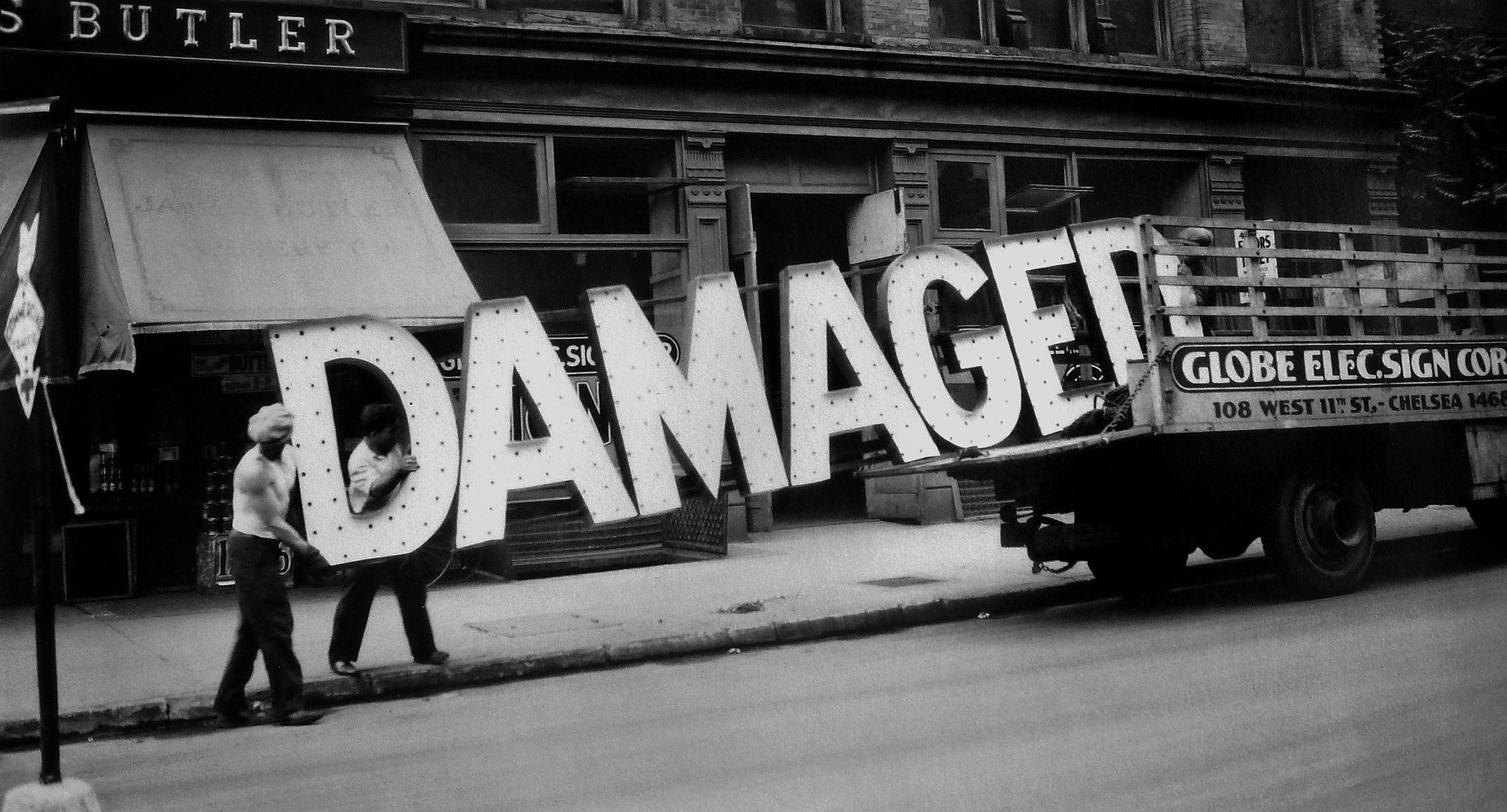

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Truck and Sign

1928-1930

Gelatin silver print

16.5 x 22.2cm

Collection particulière, San Francisco

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Fernando Maquieira, Cromotex

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

New York City Street Corner

1929

Gelatin silver print

18.4 x 12.7cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Self-Portrait in Automated Photobooth

1930

Gelatin silver print

18.3 x 3.8cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist-RMN-GP/Image of the MMA

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Self-Portrait in Automated Photobooth (details)

1930

Gelatin silver print

18.3 x 3.8cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist-RMN-GP/Image of the MMA

Walker Evans (1903-1975) was one of the most important of twentieth-century American photographers. His photographs of the Depression years of the 1930s, his assignments for Fortune magazine in the 1940s and 1950s, and his “documentary style” influenced generations of photographers and artists. His attention to everyday details and the commonplace urban scene did much to define the visual image of 20th-century American culture. Some of his photographs have become iconic.

Conceived as a retrospective of Evans’s work as a whole, the Centre Pompidou exhibition presents three hundred vintage prints in a novel and revelatory thematic organisation. It highlights the photographer’s recurrent concern with roadside buildings, window displays, signs, typography and faces, offering an opportunity to grasp what no doubt lies at the heart of Walker Evans’ work: the passionate quest to identify the fundamental features of American vernacular culture. In an interview of 1971, he explained the attraction as follows: “You don’t want your work to spring from art; you want it to commence from life, and that’s in the street now. I’m no longer comfortable in a museum. I don’t want to go to them, don’t want to be ‘taught’ anything, don’t want to see ‘accomplished’ art. I’m interested in what’s called vernacular. For example, finished, I mean educated, architecture doesn’t interest me, but I love to find American vernacular”.

In the English-speaking countries, and in America more notably, the term “vernacular” designates those popular or informal forms of expression used by ordinary people for everyday purposes – essentially meaning all that falls outside art, outside the recognised networks of production and legitimation, and which in the US thus serves to define a specifically American culture. It is all the little details of the everyday environment that make for “Americanness”: wooden roadside shacks, the way a shopkeeper lays out his wares in the window, the silhouette of the Ford Model T, the pseudo-cursive typography of Coca-Cola signs. It is a crucial notion for the understanding of American culture. It is to be found in the literature as early as the 19th century, but it is only in the late 1920s that it is first deployed in a systematic study of architecture. Its importance in American art would be theorised in the 1940s, by John Atlee Kouwenhoven, a professor of English with a particular interest in American studies who was close to Walker Evans himself.

After an introductory section that looks at Evans’s modernist beginnings, the exhibition introduces the subjects that would fascinate him throughout his career: the typography of signs, the composition of window displays, the frontages of little roadside businesses, and so on. It then goes on to show how Evans himself adopted the methods or visual forms of vernacular photography in becoming, for the time of an assignment, an architectural photographer, a catalogue photographer, an ambulant portrait photographer, while all the time explicitly maintaining the standpoint of an artist.

This exhibition is the first major museum retrospective of Evans’s work in France. Unprecedented in its ambition, it retraces the whole of his career, from his earliest photographs in the 1920s to the Polaroids of the 1970s, through more than 300 vintage prints drawn from the most important American institutions (among them the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.) and also more than a dozen private collections. It also features a hundred or so other exhibits drawn from the post cards, enamel signs, print images and other graphic ephemera that Evans collected his whole life long.

Press release from the Centre Pompidou

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Westchester, New York, farmhouse

1931

Gelatin silver print pasted on cardboard

18 x 22.1cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris

© W. Evans Arch., The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Centre Pompidou / Dist. RMN-GP

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Main Street, Saratoga Springs, New York

1931

Gelatin silver print

18.73 x 16.19cm

Collection particulière, San Francisco

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Fernando Maquieira, Cromotex

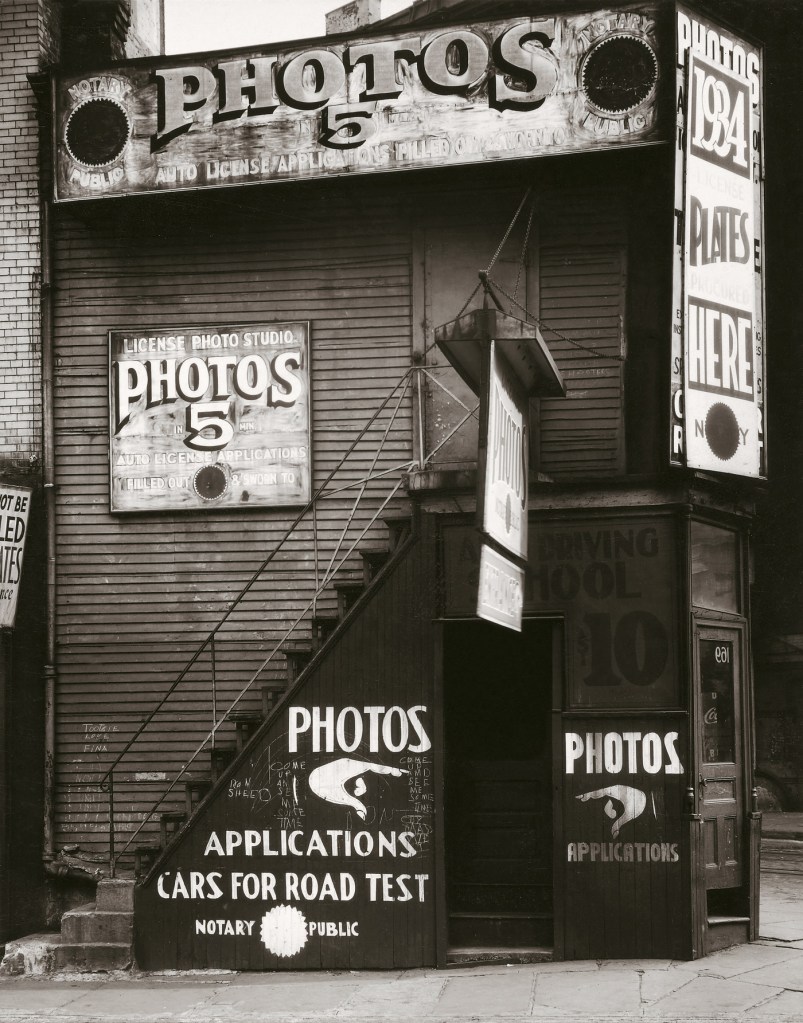

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

License Photo Studio, New York

1934

Gelatin silver print

27.9 x 21.6cm (image: 18.3 x 14.4cm)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

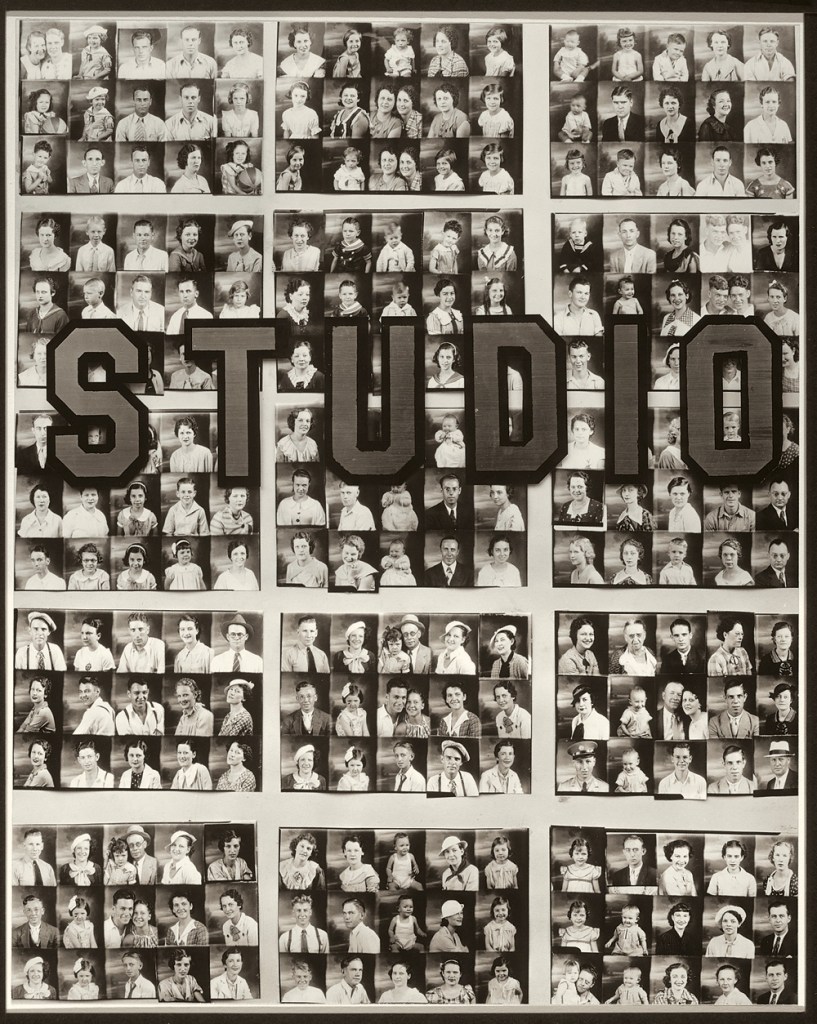

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Penny Picture Display, Savannah

1936

Gelatin silver print

21.9 x 17.6cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Willard Van Dyke

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © 2016. Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Joe’s Auto Graveyard

1936

Gelatin silver print

11.43 x 18.73cm

Collection particulière, San Francisco

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Ian Reeves

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Houses and Billboards in Atlanta

1936

Gelatin silver print

16.5 x 23.2cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © 2016. Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence

Curator’s point of view

“You don’t want your work to spring from art; you want it to commence from life, and that’s in the street now. I’m no longer comfortable in a museum. I don’t want to go to them, don’t want to be ‘taught’ anything, don’t want to see ‘accomplished’ art. I’m interested in what’s called vernacular.”

Walker Evans, interviewed by Leslie Katz (1971)

Through more than 400 photographs and documents, this retrospective of the work of Walker Evans (1903-1975) explores the American photographer’s fascination with his country’s vernacular culture. Evans was one of the most important of twentieth-century American photographers. His photographs of the Depression years of the 1930s, his “documentary style” and his interest in American popular culture influenced generations of photographers and artists. Bringing together the best examples of his work, drawn from the most important private and public collections, the exhibition also accords a large place to the artefacts that Evans himself collected throughout his life, to offer a fresh approach to the work of one of the most significant figures in the history of photography.

Study of his images – from the very first photographs of the 1920s to the Polaroids of his last years – reveals a fascination with the utilitarian, the domestic and the local. This interest in popular forms and practices emerged very early, when he started to collect postcards as a teenager. More than ten thousand items he had gathered by the time of his death are now held by the Metropolitan Museum, New York. Other everyday objects from his personal collection – enamel signs, handbills and adverts – are exhibited here.

Walker Evans’s attraction to the vernacular finds expression, above all, in his choice of subjects: Victorian architecture, roadside buildings, shopfronts, cinema posters, placards, signs, etc. His pictures also feature the faces and bodies of ordinary people, whether victims of the Depression or anonymous passers-by. Something else “typically American” was the underside of progress. During the 1930s in particular, the American landscape was strewn with ruin and waste. Evans kept an eye on them ever after. Industrial waste, building debris, automobile carcases, wooden houses in ruins, Louisiana mansions fallen in the world, antiques, garbage, faded interiors, bare patches in exterior render: these were the other face of America. Just as much as the towering skyscraper or the gleaming motor car, all this was an element of the modern. This concern with decline and obsolescence gave the photographer a critical edge and reveals a profound fascination with the mechanisms of overproduction and consumption characteristic of the age.

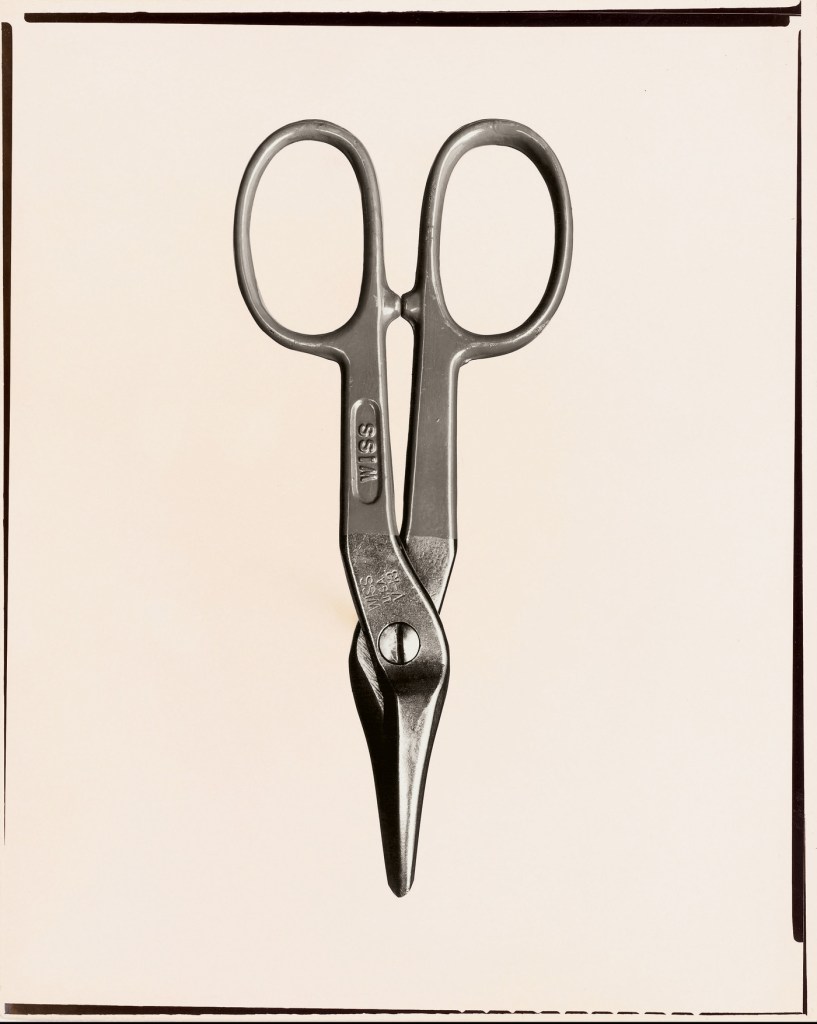

Evans didn’t just collect the forms of the vernacular, he also borrowed its methods. In many of his images, he adopts the codes of applied photography: the shots in series, the frontality, the apparent objectivity. Waiting, camera in hand on the corner of the street or in the subway, he accumulated portraits of city-dwellers by the dozen, releasing his shutter with the mechanical regularity of a photo booth. Working like a post-card photographer or architectural photographer, Evans built up, in surprisingly systematic fashion, a catalogue of churches, doors, monuments and small-town main streets. Sculptures, wrought-iron chairs, household tools: all seem to have been selected for their unique qualities as objects. The repetitivity, the apparent objectivity and the absence of emphasis in these images are typical of commercial photographs produced to order. In 1935, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, asked Evans to photograph the six hundred sculptures of the exhibition of “African Negro Art”. The method he adopted was that of the catalogue photographer, rigorously avoiding dramatic effects by eliminating shadow; tightly framed and set against a neutral background, the pieces find a new elegance. The photographer would often have recourse to this regime in the years that followed, notably for a portfolio entitled “Beauties of the Common Tool”, published in Fortune magazine in July 1955. This adoption of the forms and procedures of non-artistic photography even as Evans laid claim to art prefigures – some decades in advance! – the practices of the conceptual artists of the 1960s.

Clément Chéroux

Julie Jones

in Code Couleur, No. 28, May – August 2017, pp. 14-17

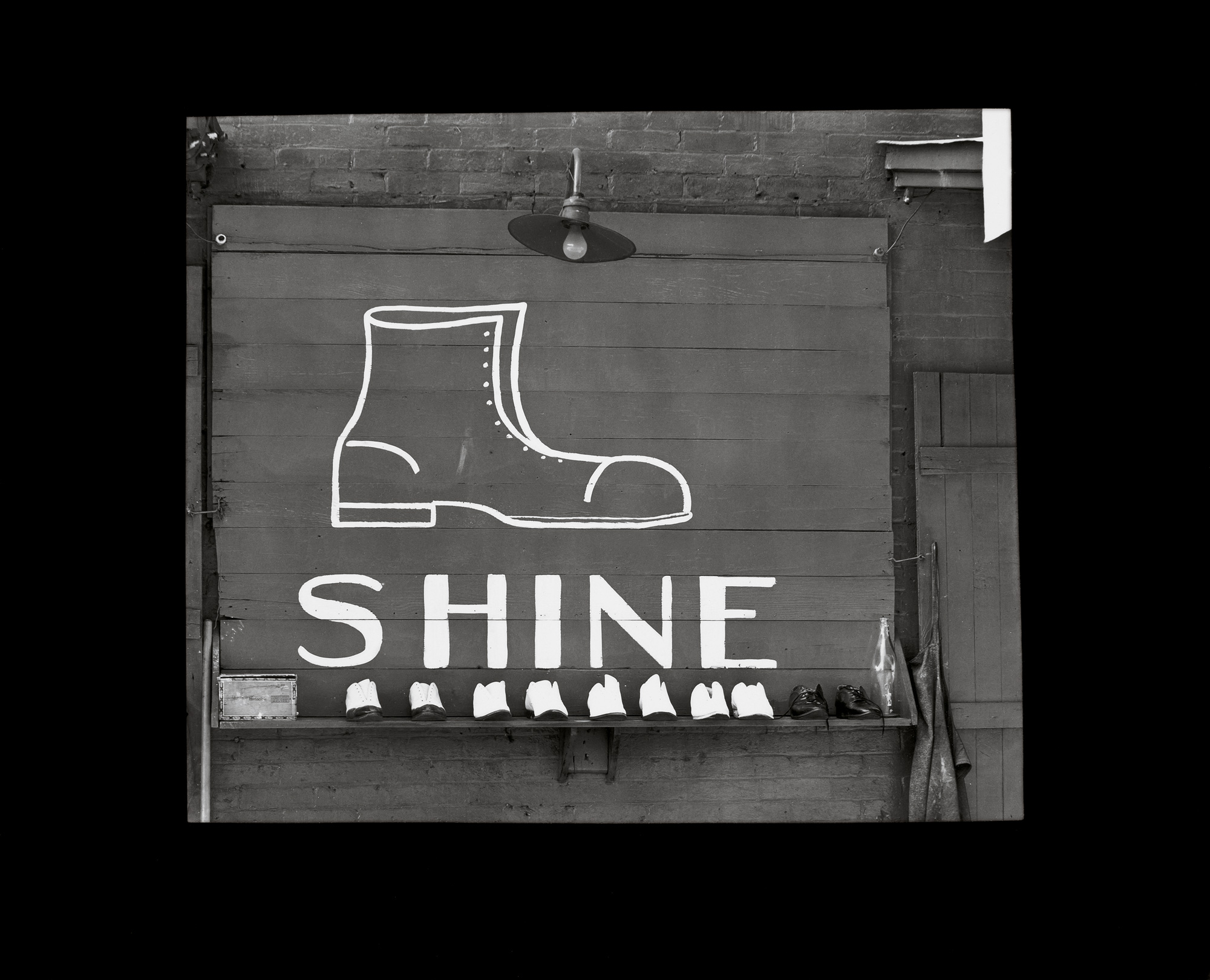

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Shoeshine Stand Detail in Southern Town

1936

Gelatin silver print

14.5 x 17cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Anonymous Gift

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist-RMN-GP/Image of the MMA

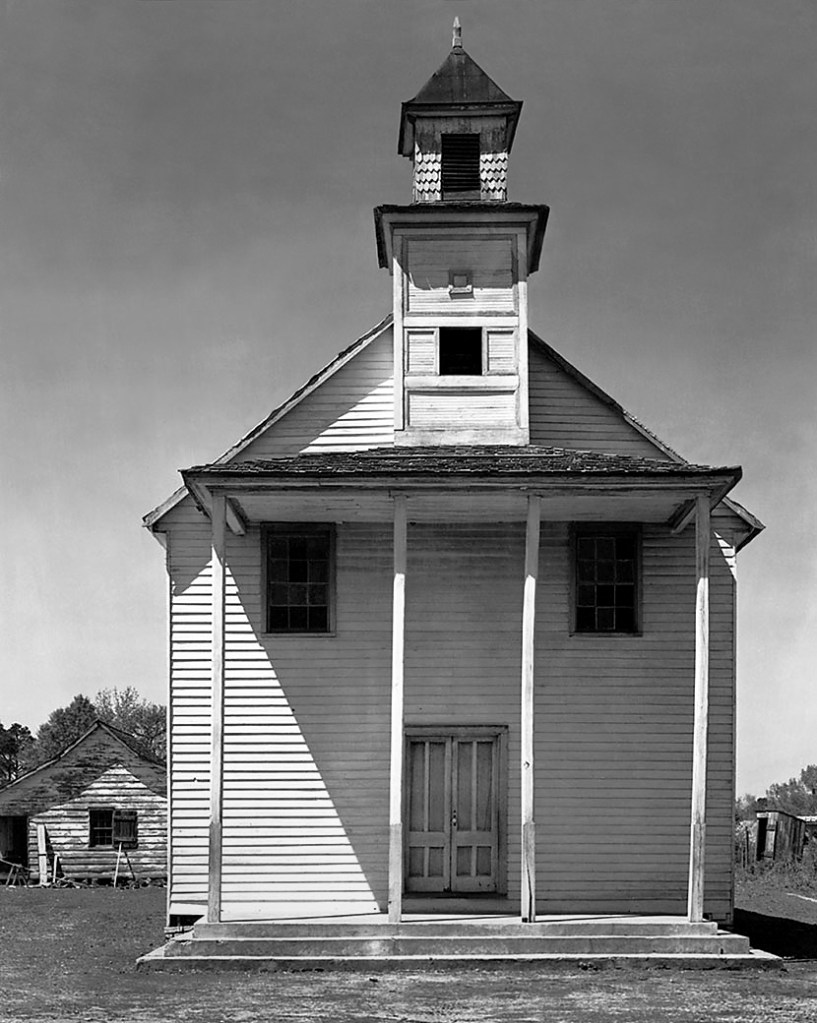

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Negroes’ Church, South Carolina

March 1936, circulation April 1969

Gelatin silver print

25.2 x 20.2cm

Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa Acheté en 1969

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, Ottawa

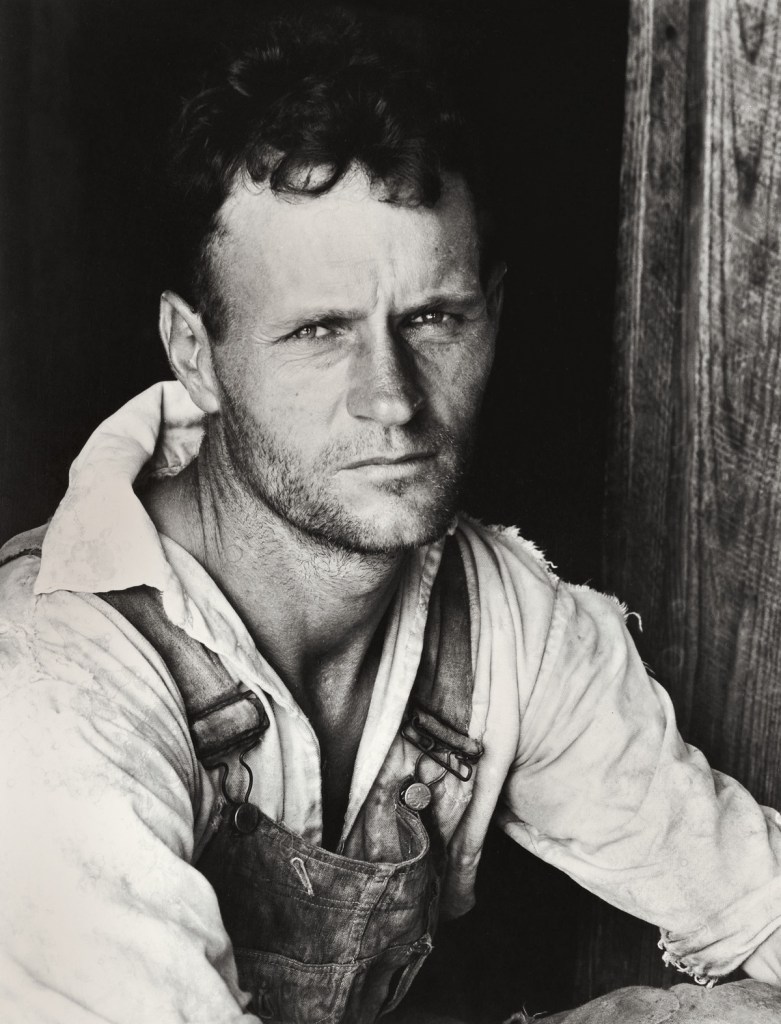

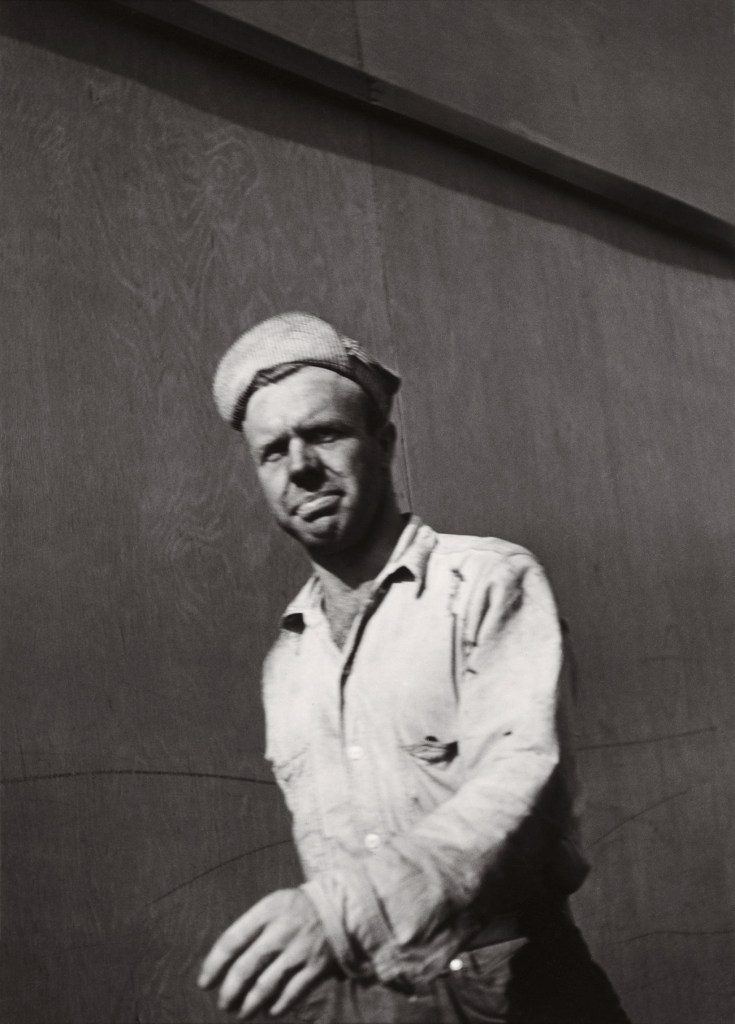

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Alabama Tenant Farmer Floyd Bourroughs

1936

Gelatin silver print

22.9 x 18.4cm

Collection particulière, San Francisco

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Fernando Maquieira, Cromotex

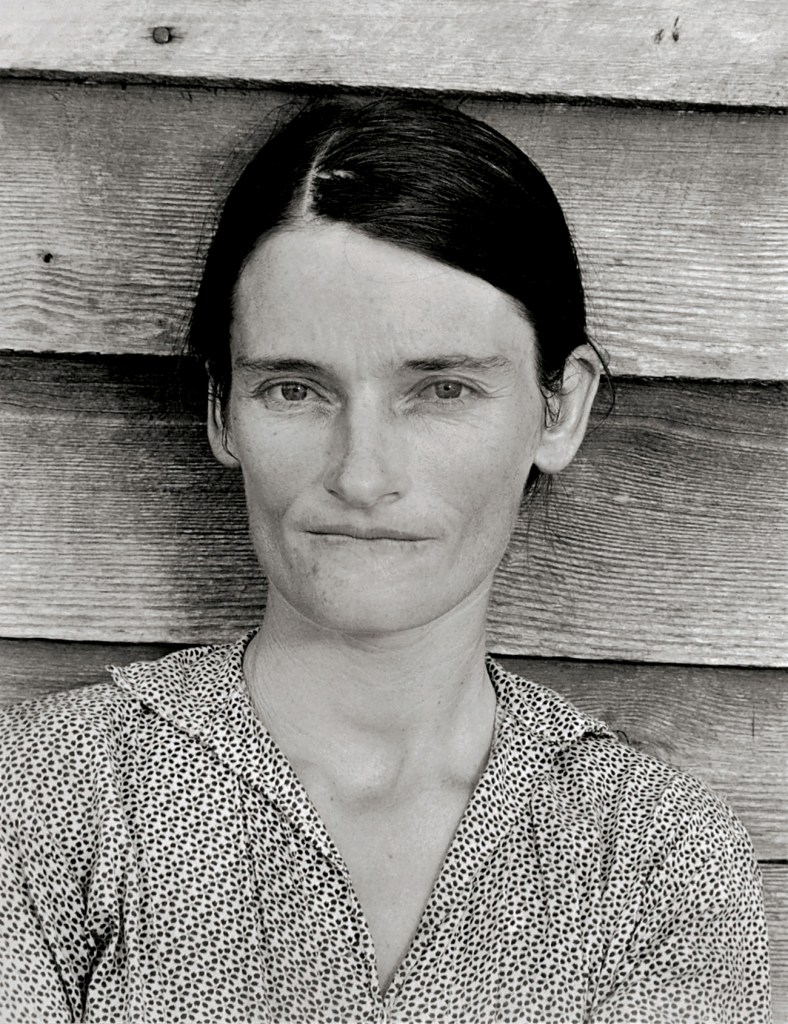

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Allie Mae Burroughs, Wife of a Cotton Sharecropper, Hale Country, Alabama

1936

Gelatin silver print

22.3 x 17.3cm

Collection particulière

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Collection particulière

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Subway Portrait

January 1941

Gelatin silver print

20.9 x 19.1cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington Gift of Kent and Marcia Minichiello, in Honour of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © National Gallery of Art, Washington

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Resort Photographer at Work

1941

Gelatin silver print, later print

15.9 x 22.4cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Anna Maria, Florida

October 1958

Oil on fibreboard

40 × 50.2cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Walker Evans Archive, 1994

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image of the MMA

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Untitled, Detroit

1946

Gelatin silver print

16 x 11.4cm

Fondation A.Stichting, Bruxelles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © Fondation A.Stichting, Bruxelles

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Tin Snips by J. Wiss and Sons Co., $1.85

1955

Gelatin silver print

25.2 x 20.3cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo: © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Centre Pompidou

75191 Paris cedex 04

Phone: 00 33 (0)1 44 78 12 33

Opening hours:

Exhibition open every day from 11am – 9pm except on Tuesday

Closed on May 1st

You must be logged in to post a comment.