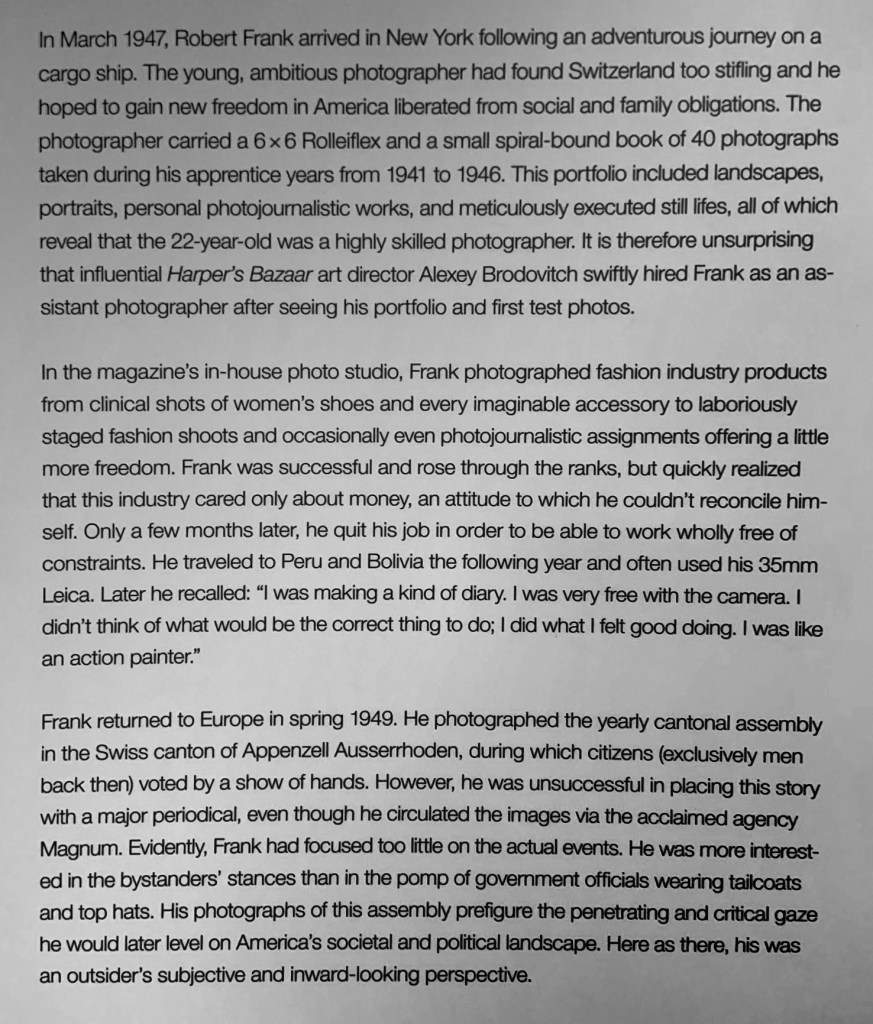

Exhibition dates: 2nd July – 3rd October, 2021

Curators: The New Woman Behind the Camera is curated by Andrea Nelson, Associate Curator in the Department of Photographs, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The Met’s presentation is organised by Mia Fineman, Curator, with Virginia McBride, Research Assistant, both in the Department of Photographs.

Marion Post Wolcott (American, 1910-1990)

[Haircutting in Front of General Store and Post Office on Marcella Plantation, Mileston, Mississippi]

1939

Gelatin silver print

9 13/16 × 12 11/16 in. (25 × 32.2cm)

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

This is the first of two postings on this exhibition, this first one when it is taking place at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The second posting will be its iteration at the National Gallery of Art, Washington starting on 31st October, with many more images. I will write more about the exhibition in the second posting.

The only thing you really need to know is… I bought the catalogue. Rarely do I buy catalogues, but that’s how important I think this exhibition is.

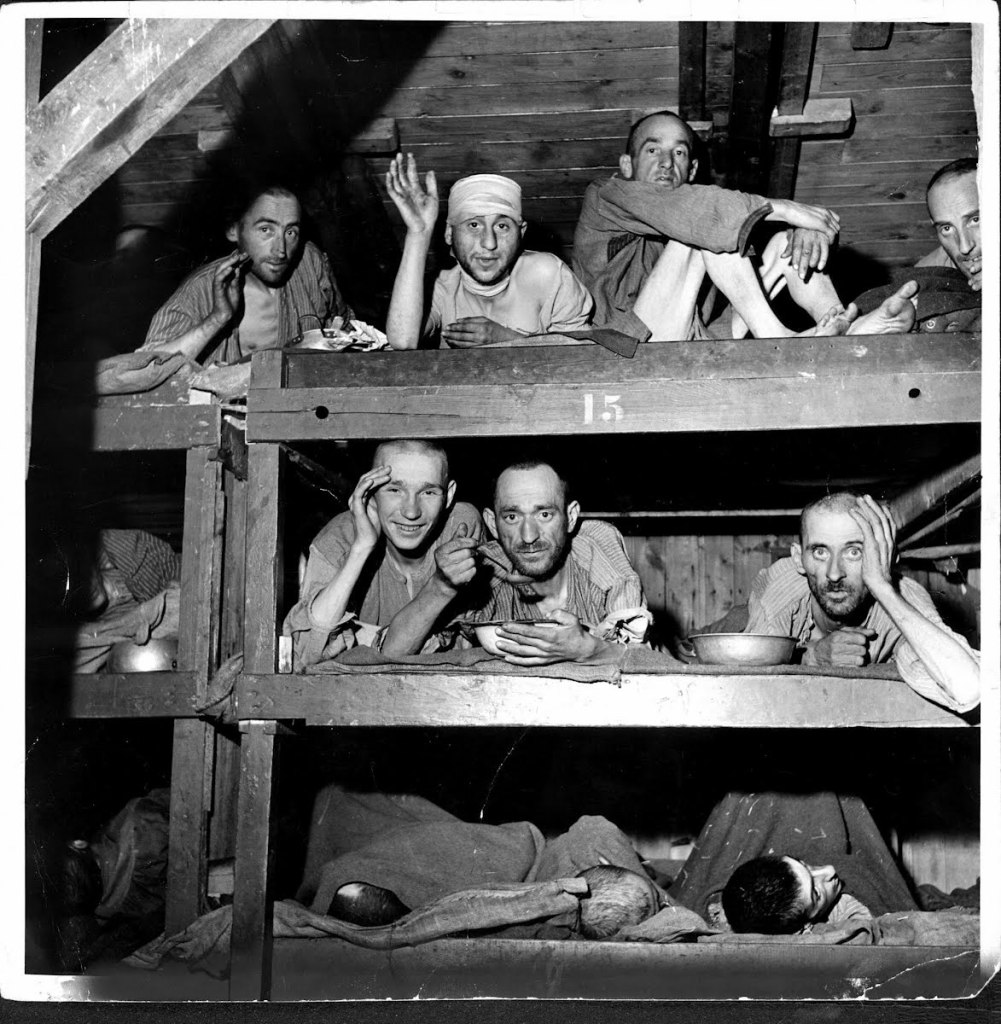

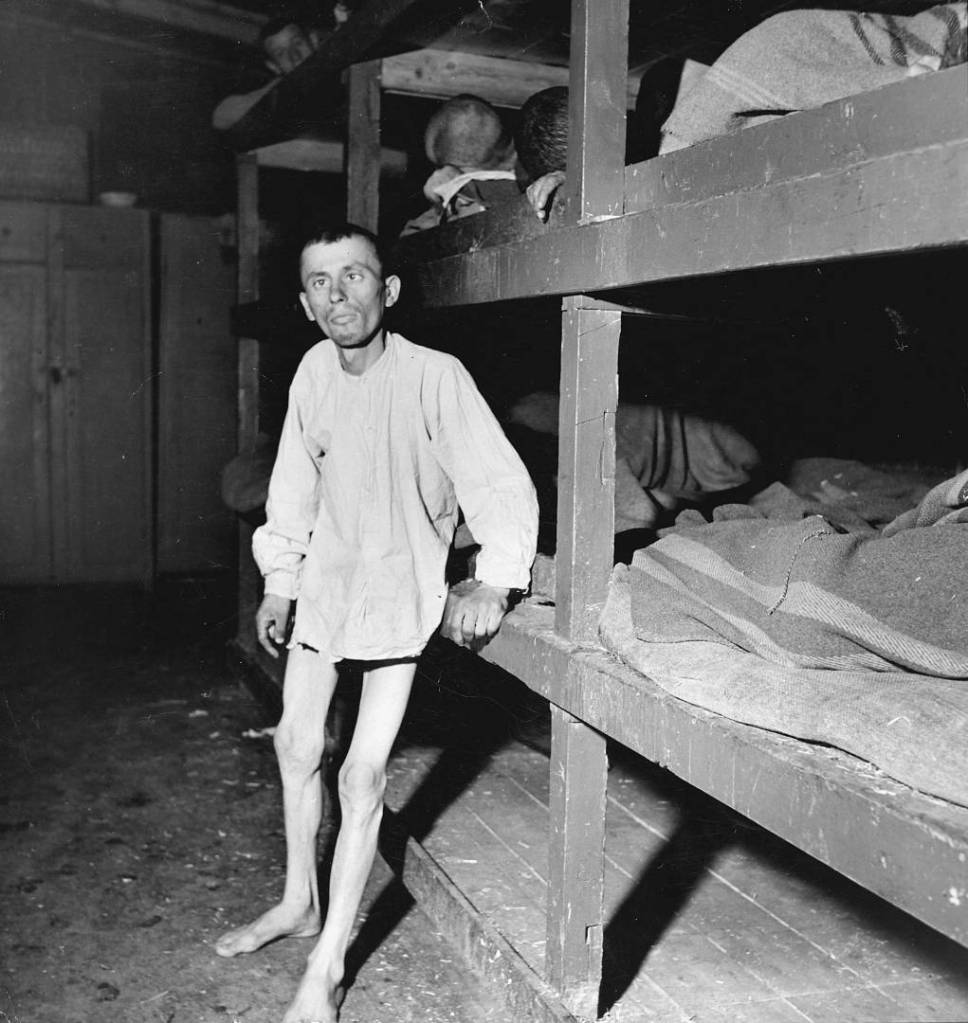

My favourite photographs in this posting are two atmospheric self-portraits: Gertrud Arndt’s Masked Self-Portrait (No. 16) (1930, below) and Marta Astfalck-Vietz’s Self-Portrait (nude with lace) (c. 1927, below). The most disturbing but uplifting are Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs of the liberation of Buchenwald concentration camp: after all that he had gone through, how the young man can smile at the flash of the camera is miraculous.

But really, there is not a dud photograph in this posting. They are all strong, intelligent, creative images. I admire them all.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

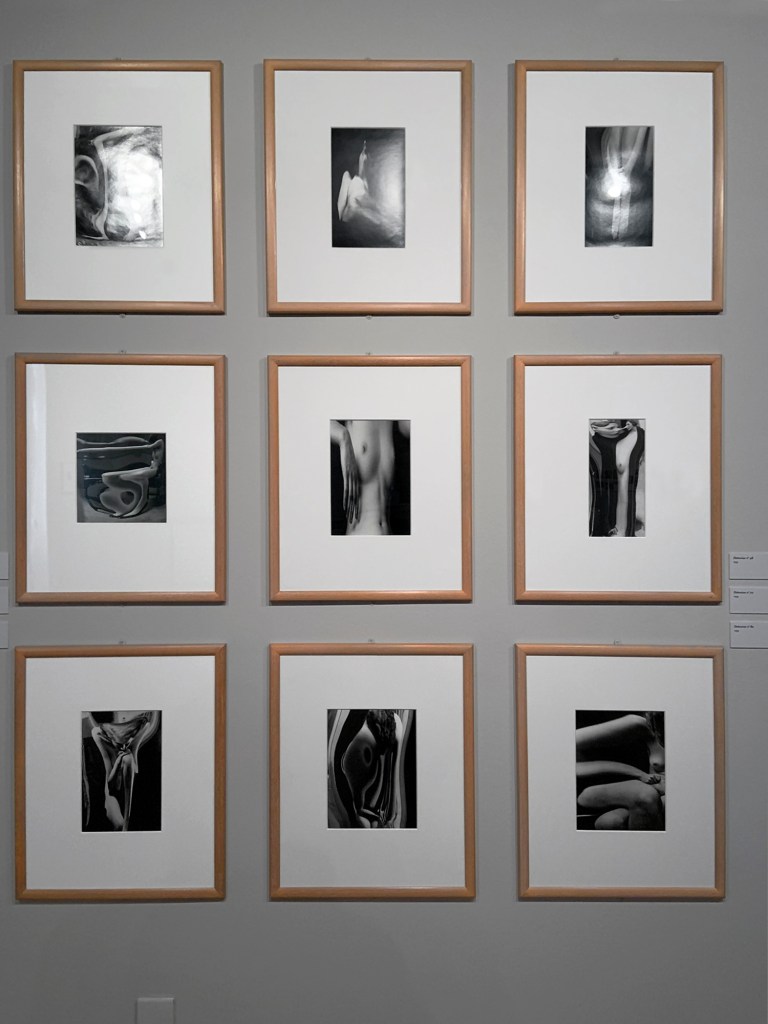

The New Woman of the 1920s was a powerful expression of modernity, a global phenomenon that embodied an ideal of female empowerment based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art. Featuring more than 120 photographers from over 20 countries, this groundbreaking exhibition explores the work of the diverse “new” women who embraced photography as a mode of professional and artistic expression from the 1920s through the 1950s. During this tumultuous period shaped by two world wars, women stood at the forefront of experimentation with the camera and produced invaluable visual testimony that reflects both their personal experiences and the extraordinary social and political transformations of the era.

The exhibition is the first to take an international approach to the subject, highlighting female photographers’ innovative work in studio portraiture, fashion and advertising, artistic experimentation, street photography, ethnography, and photojournalism. Among the photographers featured are Berenice Abbott, Ilse Bing, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Florestine Perrault Collins, Imogen Cunningham, Madame d’Ora, Florence Henri, Elizaveta Ignatovich, Consuelo Kanaga, Germaine Krull, Dorothea Lange, Dora Maar, Tina Modotti, Niu Weiyu, Tsuneko Sasamoto, Gerda Taro, and Homai Vyarawalla. Inspired by the global phenomenon of the New Woman, the exhibition seeks to reevaluate the history of photography and advance new and more inclusive conversations on the contributions of female photographers.

The New Woman Behind the Camera Virtual Opening

The New Woman of the 1920s through the 1950s was a powerful expression of modernity, a global phenomenon that embodied an ideal of female empowerment based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art. During this tumultuous period shaped by two world wars, women stood at the forefront of experimentation with the camera and produced invaluable visual testimony that reflects both their personal experiences and the extraordinary social and political transformations of the era.

Join Mia Fineman, Curator in the Department of Photographs, for a tour of The New Woman Behind the Camera, a groundbreaking exhibition, which features more than 120 photographers from over 20 countries and explores the work of the diverse “new” women who embraced photography as a mode of professional and artistic expression.

New Woman Behind the Camera

The New Woman of the 1920s was a powerful expression of modernity, a global phenomenon that embodied an ideal of female empowerment based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art. Featuring more than 120 photographers from over 20 countries, this groundbreaking exhibition explores the work of the diverse “new” women who embraced photography as a mode of professional and artistic expression from the 1920s through the 1950s. During this tumultuous period shaped by two world wars, women stood at the forefront of experimentation with the camera and produced invaluable visual testimony that reflects both their personal experiences and the extraordinary social and political transformations of the era.

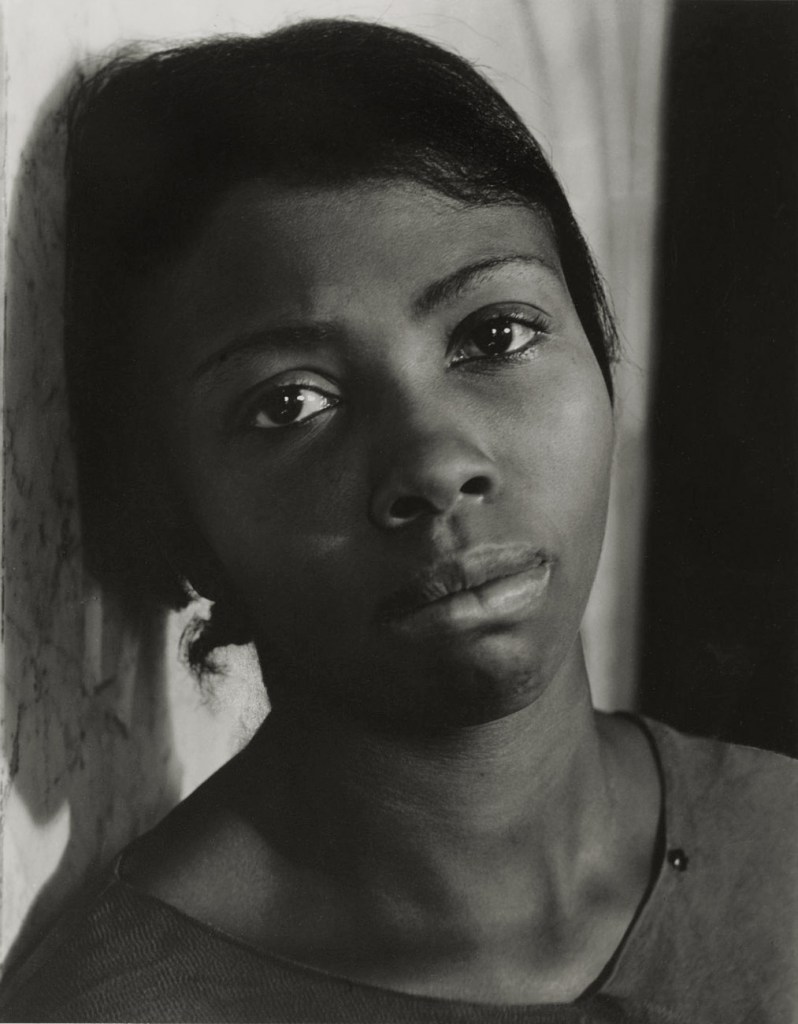

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Annie Mae Merriweather

1935

Gelatin silver print

32.9 × 24.8cm (12 15/16 × 9 3/4 in.)

Purchase, Dorothy Levitt Beskind Gift, 1974

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Consuelo Kanaga photographed Annie Mae Merriweather for the October 22, 1935 issue of New Masses (vol. 17, no. 4). This portrait accompanies a Merriweather’s account of a lynch mob in Lowndes County, Alabama. In response to a strike of the Sharecropper’s Union, members of the mob terrorised demonstrators, attacking Merriweather and murdering her husband.

The artist created this portrait of Annie Mae Meriwether for New Masses magazine, an Marxist periodical published in the United States from 1926 to 1948. The picture was commissioned to accompany an account of Meriwether’s escape from the lynch mob that had murdered her husband as retribution for his involvement with an Alabama sharecroppers’ union.

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Born in Astoria, Oregon, Consuelo Kanaga came from a family that valued ideals of social justice. After completing high school, she began writing for the San Francisco Chronicle in 1915. Within three years, she had learned darkroom technique from the paper’s photographers and become a staff photographer. She met Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, and Dorothea Lange through the California Camera Club, and was interested in the fine-art photography in Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work. A series of three marriages and one canceled engagement precipitated Kanaga’s periodic relocations between New York and San Francisco, where she established a portrait studio in 1930. While not an official member of the f/64 group, her images were exhibited in its first exhibition at San Francisco’s M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in 1932. Kanaga was involved in West Coast liberal politics, and when she returned to New York in 1935, she was associated with the leftist Photo League; she lectured there in 1938 with Aaron Siskind, then occupied with his Harlem Document. Her photography was championed by Edward Steichen, who included her in ‘The Family of Man’ exhibition in 1955. Kanaga’s work was featured in the 1979 ICP exhibition “Recollections: Ten Women of Photography,” and she was the subject of a retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1992.

In terms of photographic technique and depiction of subjects, romantic instincts characterise Kanaga’s work. An advocate for the rights of African-Americans and other people of colour, Kanaga distinguished her portraits from the documentary images of the Farm Security Administration by conveying her subject’s physical comfort and personal pride. The tactile sense of volume in her work is reinforced by strong contrasts in printing light and dark forms.

Meredith Fisher in Handy et al. Reflections in a Glass Eye: Works from the International Center of Photography Collection, New York: Bulfinch Press in association with the International Center of Photography, 1999, p. 219 published on the International Center of Photography website [Online] Cited 16/07/2021.

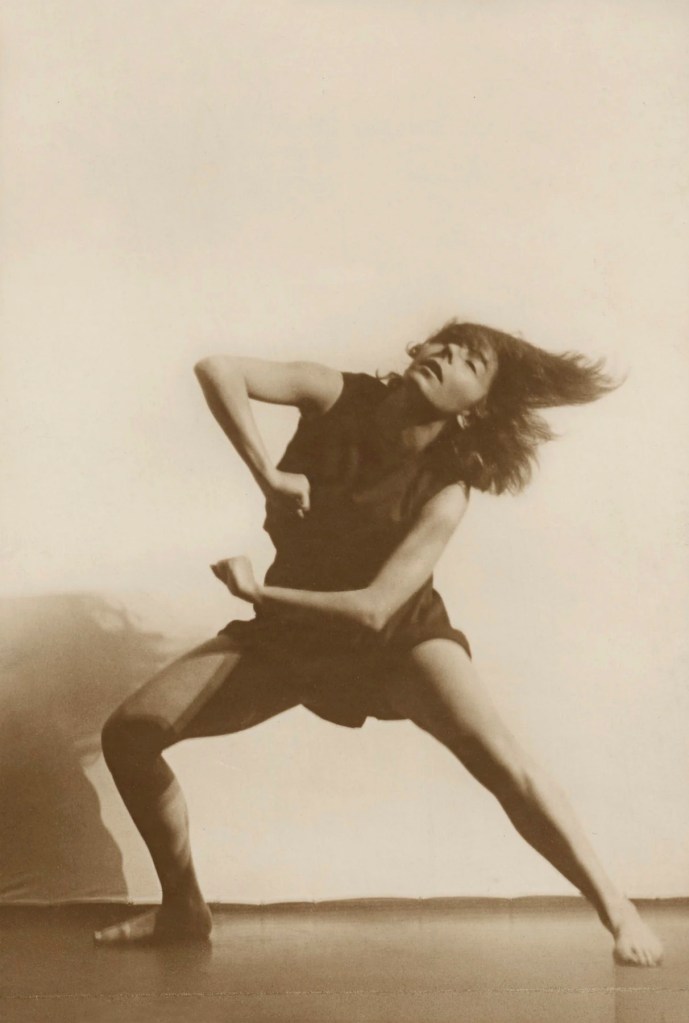

Barbara Morgan (American, 1900-1992)

Martha Graham – Lamentation

1935

Gelatin silver print

12 5/16 × 10 9/16 in. (31.2 × 26.9cm)

Purchase, Dorothy Levitt Beskind Gift, 1974

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Barbara Morgan (American, 1900-1992)

Barbara Morgan (July 8, 1900 – August 17, 1992) was an American photographer best known for her depictions of modern dancers. She was a co-founder of the photography magazine Aperture.

Morgan is known in the visual art and dance worlds for her penetrating studies of American modern dancers Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Erick Hawkins, José Limón, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman and others. Morgan’s drawings, prints, watercolours and paintings were exhibited widely in California in the 1920s, and in New York and Philadelphia in the 1930s. …

In 1935 Barbara attended a performance of the young Martha Graham Dance Company. She was immediately struck with the historical and social importance of the emerging American Modern Dance movement:

“The photographers and painters who dealt with the Depression, often, it seemed to me, only added to defeatism without giving courage or hope. Yet the galvanising protest danced by Martha Graham, Humphrey-Weidman, Tamiris and others was heartening. Often nearly starving, they never gave up, but forged life affirming dance statements of American society in stress and strain. In this role, their dance reminded me of Indian ceremonial dances which invigorate the tribe in drought and difficulty.”

Morgan conceived of her 1941 book project Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs – the year she met Graham. From 1935 through the 1945 she photographed more than 40 established dancers and choreographers, and she described her process:

“To epitomise… a dance with camera, stage performances are inadequate, because in that situation one can only fortuitously record. For my interpretation it was necessary to redirect, relight, and photographically synthesise what I felt to be the core of the total dance.”

Many of the dancers Morgan photographed are now regarded as the pioneers of modern dance, and her photographs the definitive images of their art. These included Valerie Bettis, Merce Cunningham, Jane Dudley, Erick Hawkins, Hanya Holm, Doris Humphrey, José Limón, Sophie Maslow, May O’Donnell, Pearl Primus, Anna Sokolow, Helen Tamiris, and Charles Weidman. Critics Clive Barnes, John Martin, Elizabeth McCausland, and Beaumont Newhall have all noted the importance of Morgan’s work.

Graham and Morgan developed a relationship that would last some 60 years. Their correspondence attests to their mutual affection, trust and respect. In 1980, Graham stated:

“It is rare that even an inspired photographer possesses the demonic eye which can capture the instant of dance and transform it into timeless gesture. In Barbara Morgan I found that person. In looking at these photographs today, I feel, as I felt when I first saw them, privileged to have been a part of this collaboration. For to me, Barbara Morgan through her art reveals the inner landscape that is a dancer’s world.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

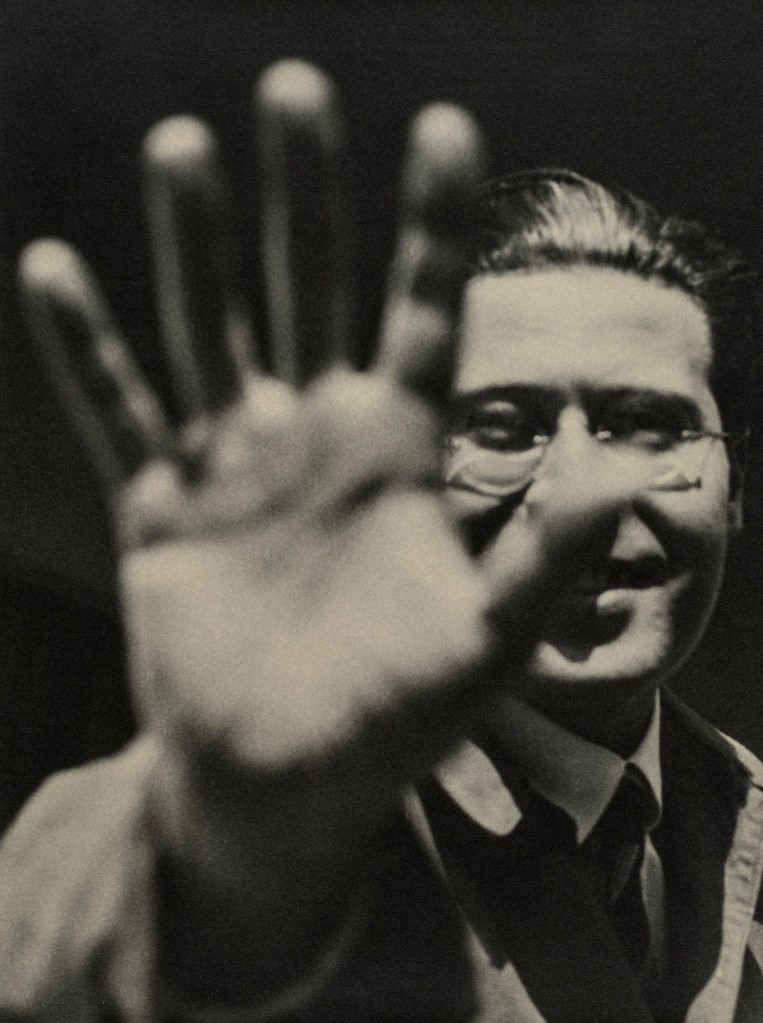

Lucia Moholy (British born Austria-Hungary, 1894-1989)

László Moholy-Nagy

1925-1926

10 3/16 × 7 15/16 in. (25.8 × 20.1cm)

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

Metropolitan Museum of Art

© 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lucia Moholy (British born Austria-Hungary, 1894-1989)

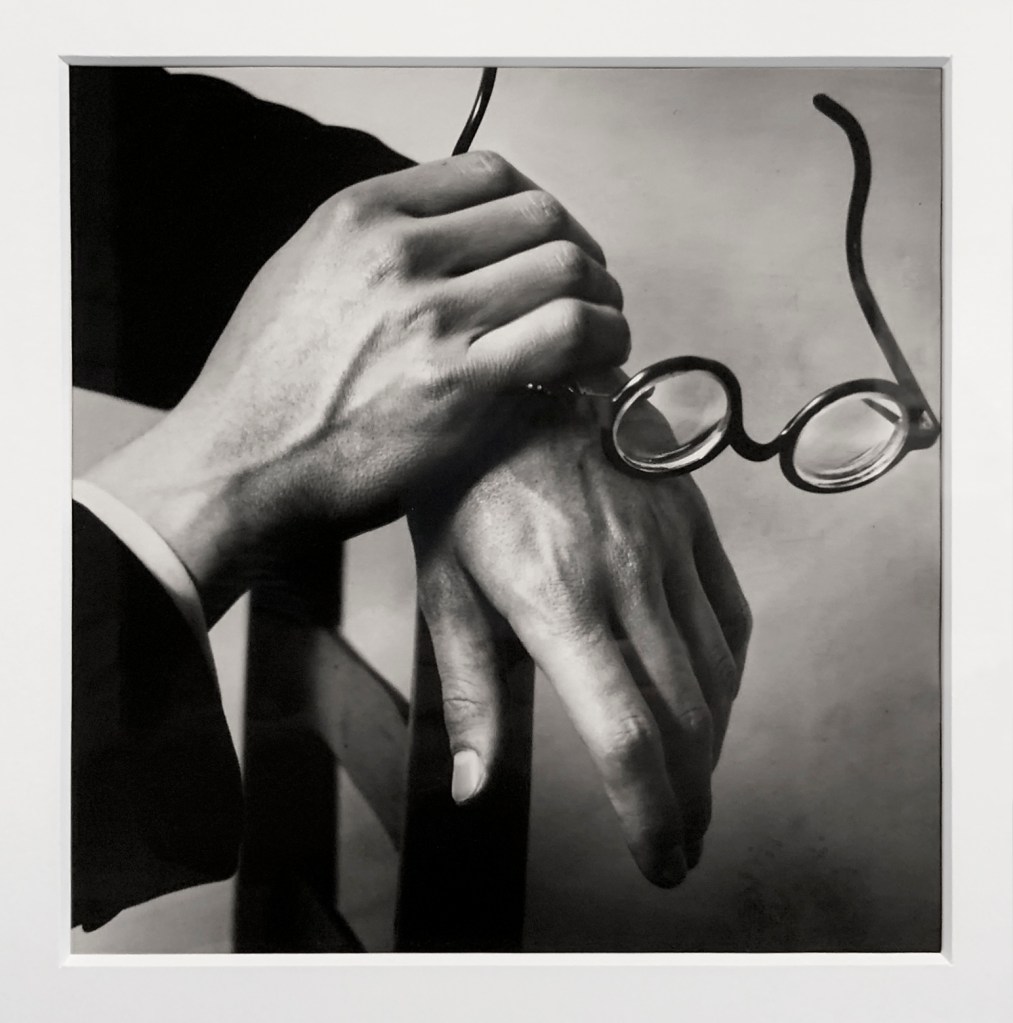

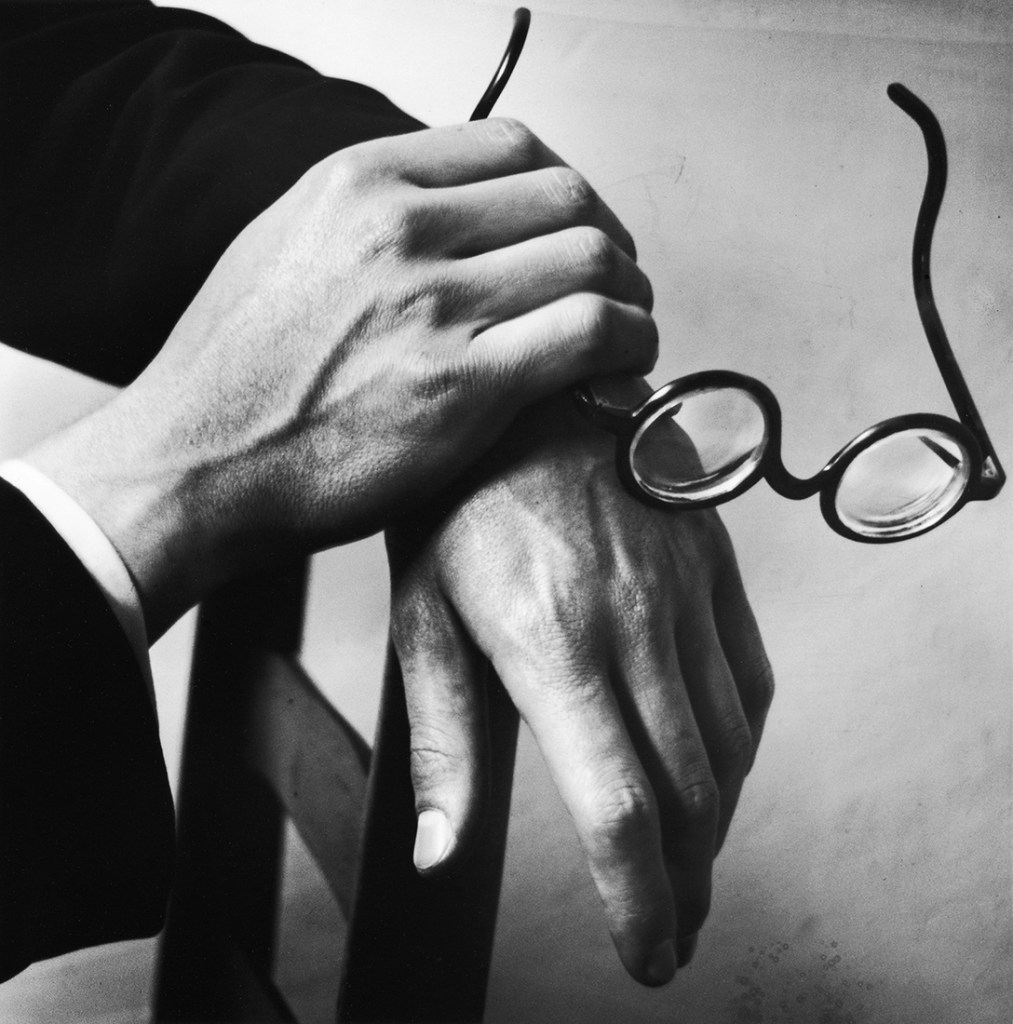

Lucia Moholy was one of the most prolific photographers at the Bauhaus between 1923 and 1928, while her husband, László Moholy-Nagy, was an instructor there. For both, photography was not simply a transparent window onto objective reality but a specific technology to be systematically explored in the modern spirit of exuberant experimentation. Here, illustrating the effect of selective focus, Moholy imprints his hand against the invisible picture plane that separates viewer and subject-a playful, disorienting gesture that collapses illusionistic depth into the concrete reality of the photographic image.

Lucia Moholy’s 1925-26 image of her celebrated photographer husband, László Moholy-Nagy, extending his hand in front of the camera was long assumed to be his own self-portrait, but research has led scholars to conclude that his wife shot the image. A wall label calls it “a striking example of the tendency to attribute the work of women artists to their male partners”.

Text from Nancy Kenney. “Triumphant in their time, yet largely erased later: a Met exhibition explores ‘The New Woman Behind the Camera’,” on The Art Newspaper website 1st July 2021 [Online] Cited 22/07/2021

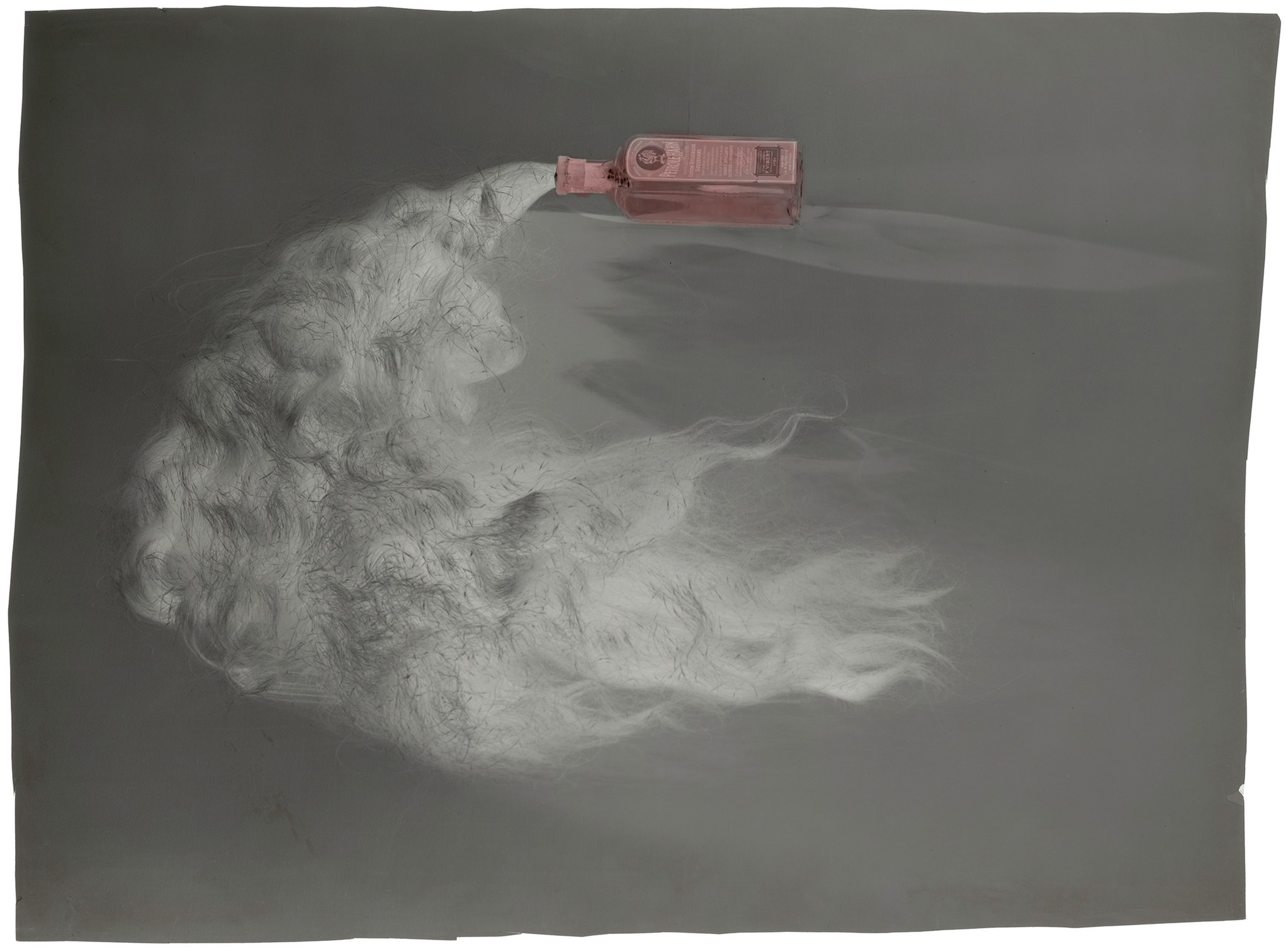

Ringl and Pit (German, active 1930-1933)

Grete Stern (Argentinian born Germany, 1904-1999)

Ellen Auerbach (German, 1906-2004)

Pétrole Hahn

1931

Gelatin silver print

9 7/16 × 11 1/8 in. (23.9 × 28.2cm)

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

Metropolitan Museum of Art

© 2021 VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Wanda Wulz (Italian, 1903-1984)

Io + gatto (Cat + I)

1932

Gelatin silver print

11 9/16 × 9 1/8 in. (29.4 × 23.2cm)

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

Metropolitan Museum of Art

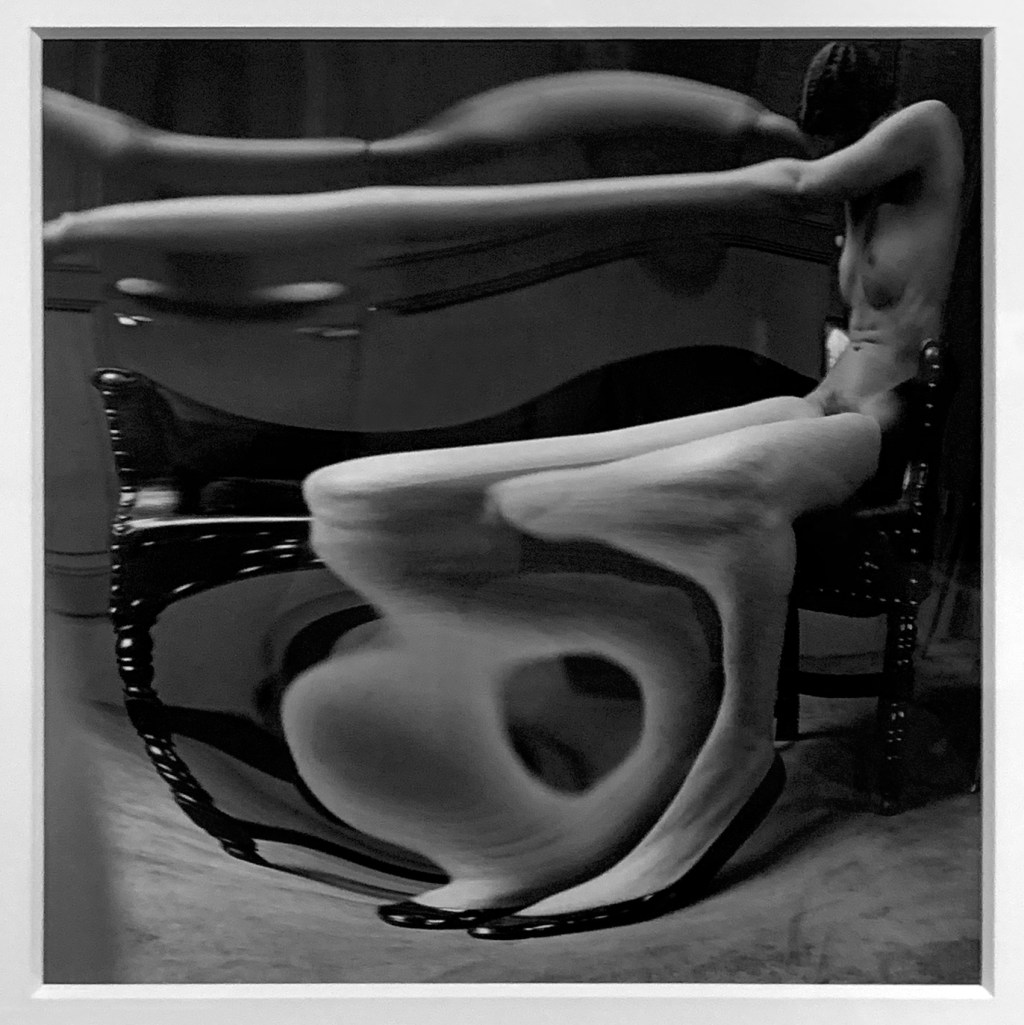

Wulz, a portrait photographer loosely associated with the Italian Futurist movement, created this striking composite by printing two negatives – one of her face, the other of the family cat – on a single sheet of photographic paper, evoking by technical means the seamless conflation of identities that occurs so effortlessly in the world of dreams.

![Lucy Ashjian (American, 1907-1993) '[Savoy Dancers]' 1935-1943 Lucy Ashjian (American, 1907-1993) '[Savoy Dancers]' 1935-1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/lucy-ashjian-savoy-dancers.jpg?w=845)

Lucy Ashjian (American, 1907-1993)

[Savoy Dancers]

1935-1943

Gelatin silver print

24 × 18.8cm (9 7/16 × 7 3/8 in.)

Gift of Gregor Ashjian Preston, 2004

Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Lucy Ashjian Estate

Lucy Ashjian (1907-1993) was an American photographer best known as a member of the New York Photo League. Her work is included in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona and the Museum of the City of New York.

Groundbreaking Exhibition to Explore How Women Photographers Worldwide Shaped the Medium from the 1920s to the 1950s

The New Woman of the 1920s was a powerful expression of modernity, a global phenomenon that embodied an ideal of female empowerment based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art. Opening July 2, 2021 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The New Woman Behind the Camera will feature 185 photographs, photo books, and illustrated magazines by 120 photographers from over 20 countries. This groundbreaking exhibition will highlight the work of the diverse “new” women who made significant advances in modern photography from the 1920s to the 1950s. During this tumultuous period shaped by two world wars, women stood at the forefront of experimentation with the camera and produced invaluable visual testimony that reflects both their personal experiences and the extraordinary social and political transformations of the era.

The exhibition is made possible in part by the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, The Daniel and Estrellita Brodsky Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. It is organised by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Max Hollein, Marina Kellen French Director of The Met, commented, “The international scope of this project is unprecedented. Though the New Woman is often regarded as a Western phenomenon, this exhibition proves otherwise by bringing together rarely seen photographs from around the world and presenting a nuanced, global history of photography. The women featured are responsible for shifting the direction of modern photography, and it is exhilarating to witness the accomplishments of these extraordinary practitioners.”

The first exhibition to take an international approach to the subject, The New Woman Behind the Camera will examine women’s pioneering work in a number of genres, from avant-garde experimentation and commercial studio practice to social documentary, photojournalism, ethnography, and sports, dance, and fashion photography. It will highlight the work of photographers such as Ilse Bing, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Claude Cahun, Florestine Perrault Collins, Elizaveta Ignatovich, Dorothea Lange, Lee Miller, Niu Weiyu, Tsuneko Sasamoto, Gerda Taro, and Homai Vyarawalla, among many others.

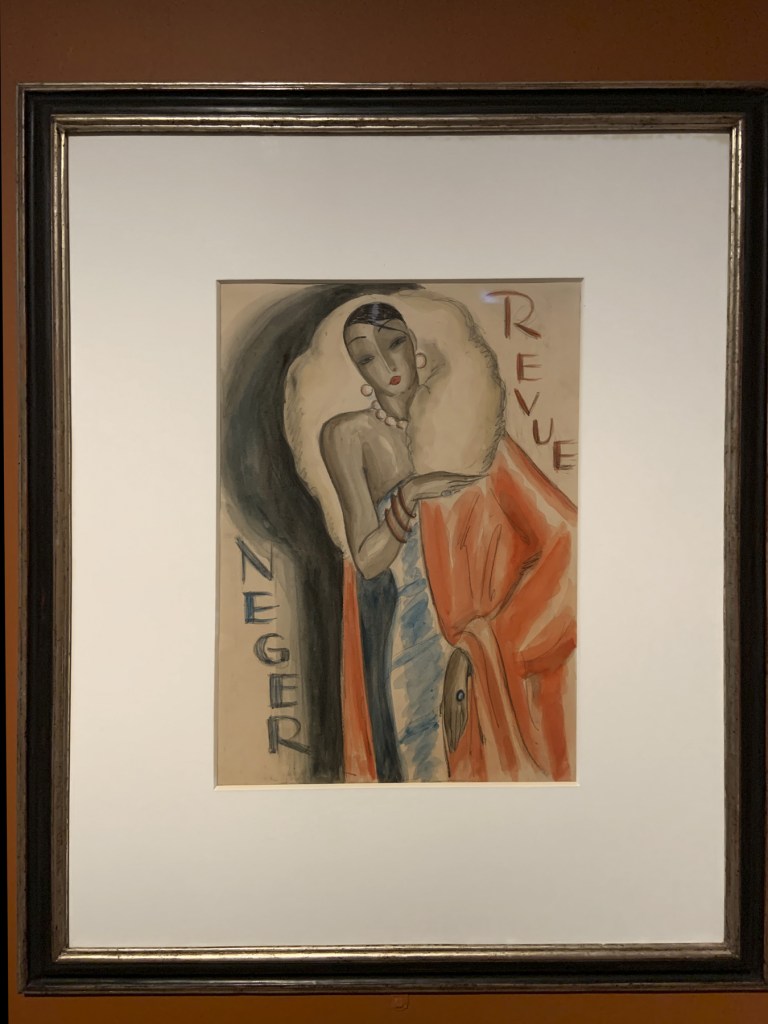

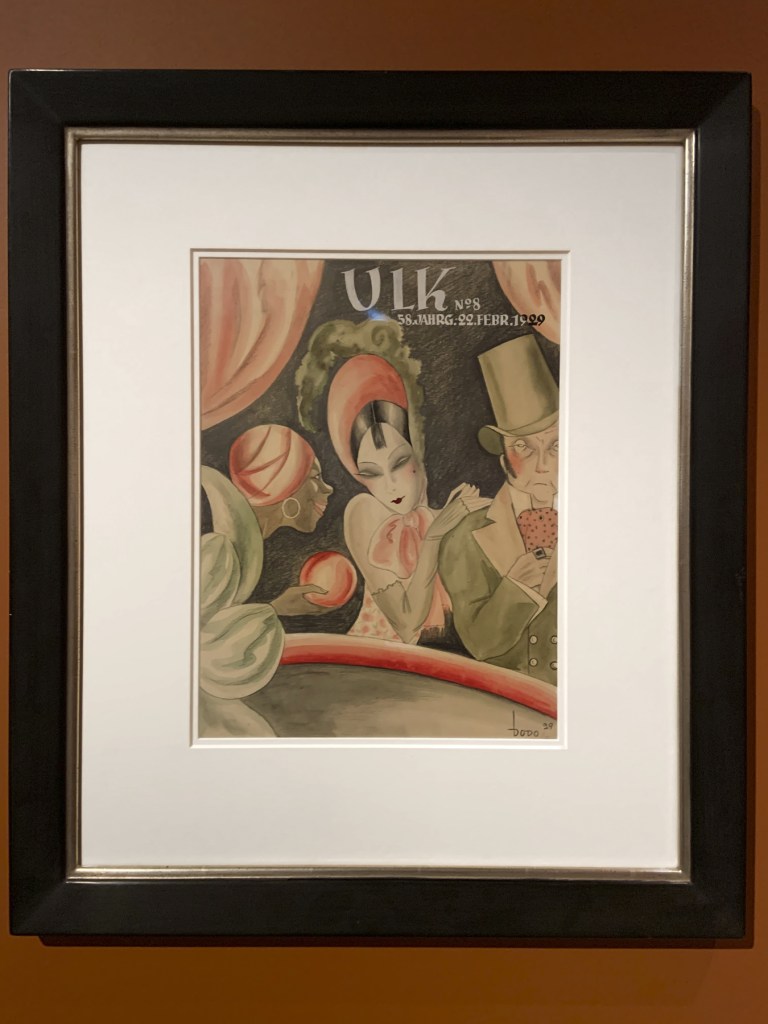

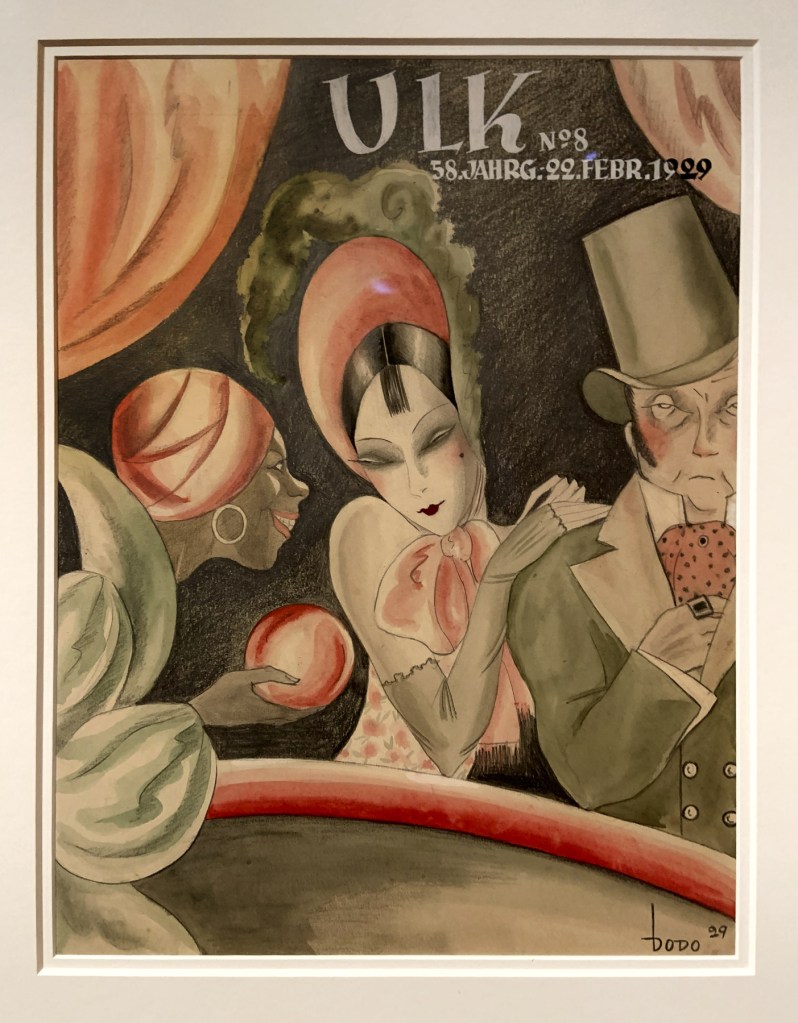

About the exhibition

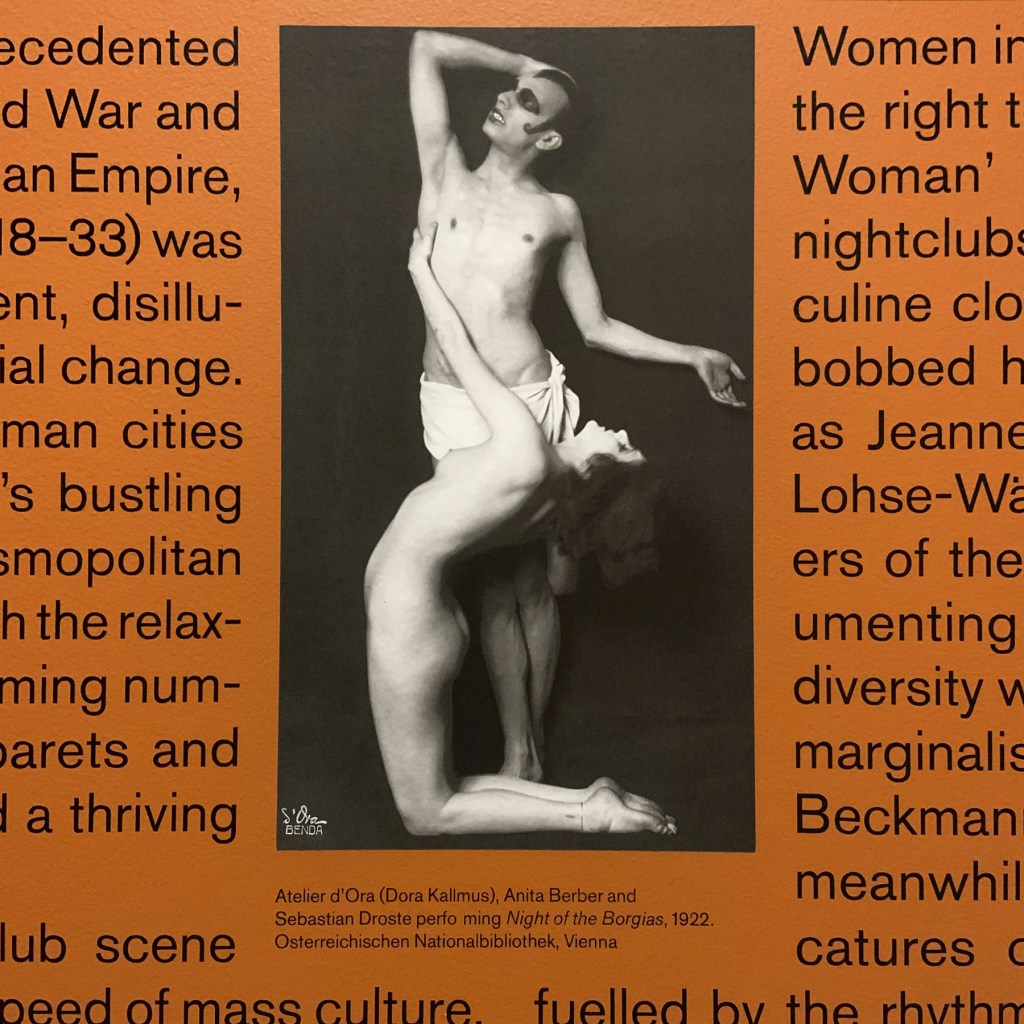

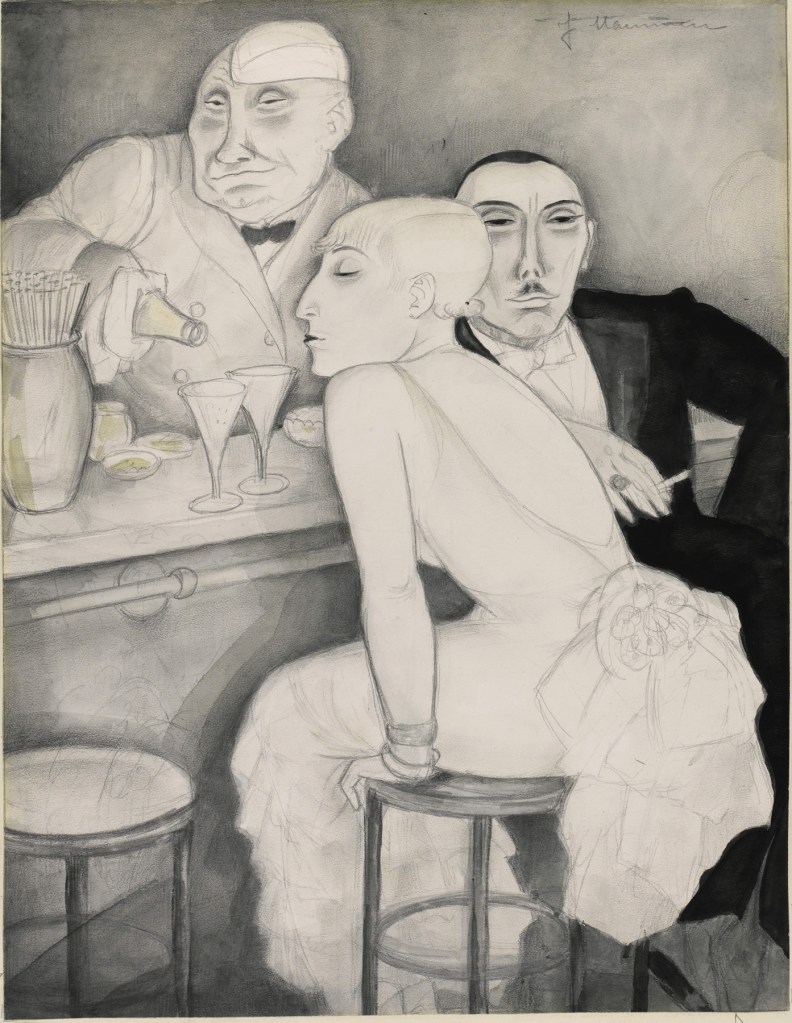

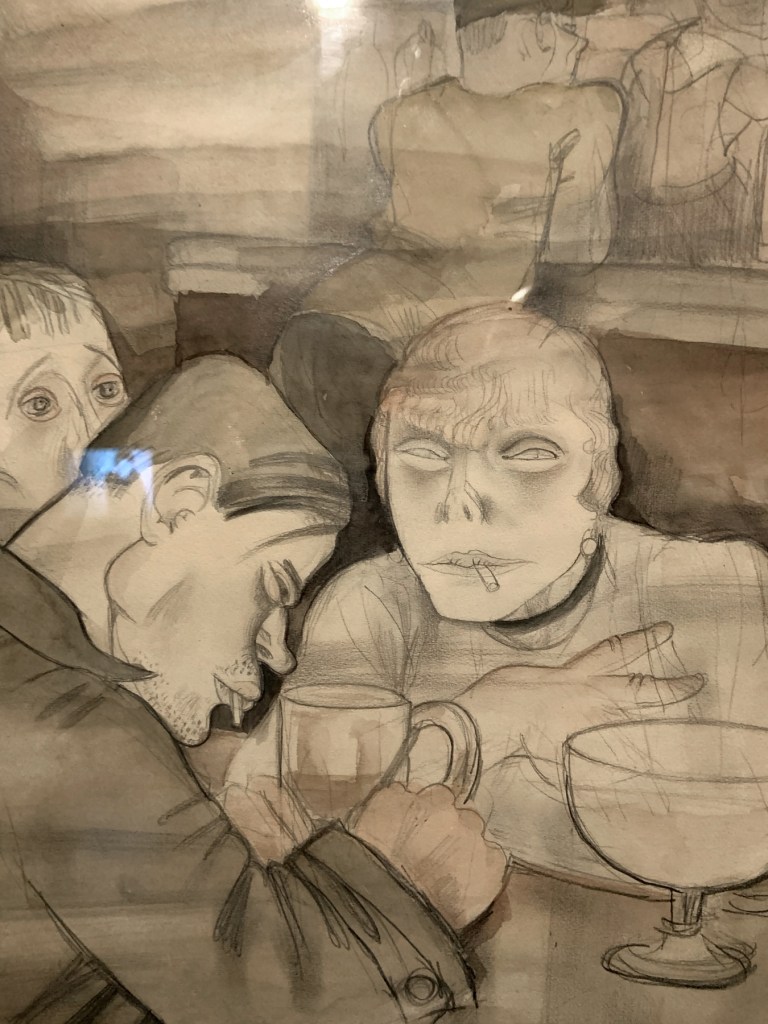

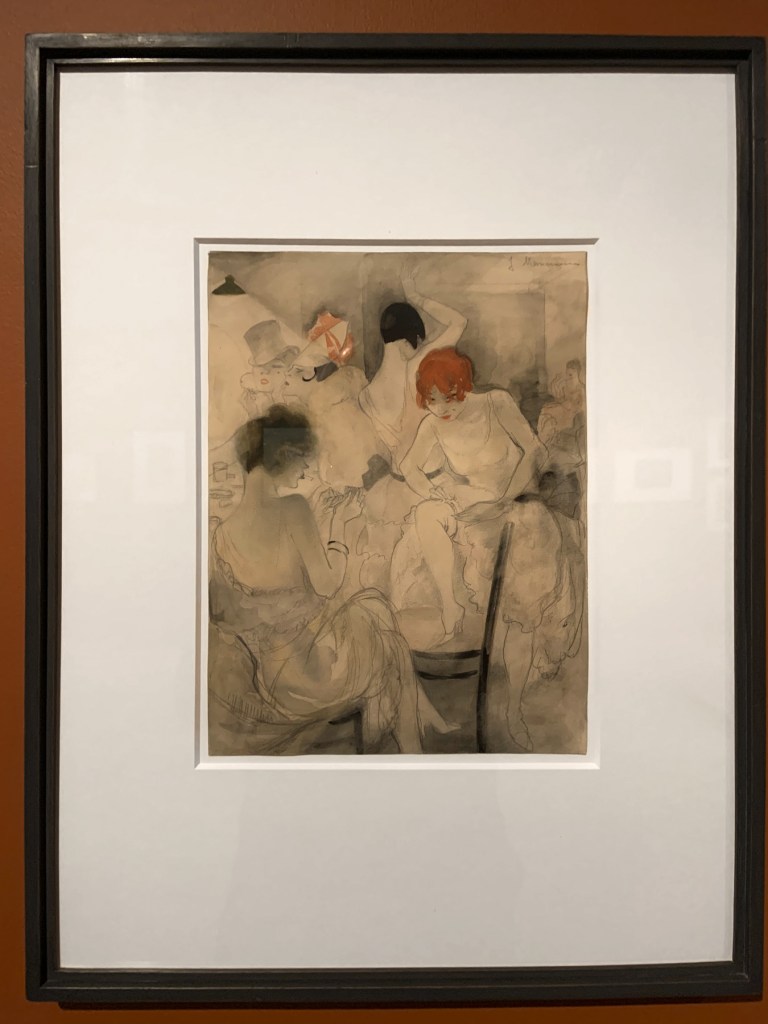

Known by different names, from nouvelle femme and neue Frau to modan gāru and xin nüxing, the New Woman of the 1920s was easy to recognise but hard to define. Her image – a woman with bobbed hair, stylish dress, and a confident stride – was everywhere, splashed across the pages of magazines and projected on the silver screen. A symbol that broke down conventional ideas of gender, the New Woman was inspiring for some and controversial for others, embraced and resisted to varying degrees from country to country.

For many of these daring women, the camera was a means to assert their self-determination and artistic expression. The exhibition begins with a selection of compelling self-portraits, often featuring the photographer with her camera. Highlights include innovative self-portraits by Florence Henri, Annemarie Heinrich, and Alma Lavenson.

For many women, commercial studios were an important entry point into the field of photography, allowing them to forge professional careers and earn their own income. From running successful businesses in Berlin, Buenos Aires, and Vienna to earning recognition as one of the first female photographers in their respective country, women around the world, including Karimeh Abbud, Steffi Brandl, Trude Fleischmann, Annemarie Heinrich, Eiko Yamazawa, and Madame Yevonde, reinvigorated studio practice. Photography studios run by Black American women, such as Florestine Perrault Collins, not only preserved likenesses but also countered racist images then circulating in the mass media.

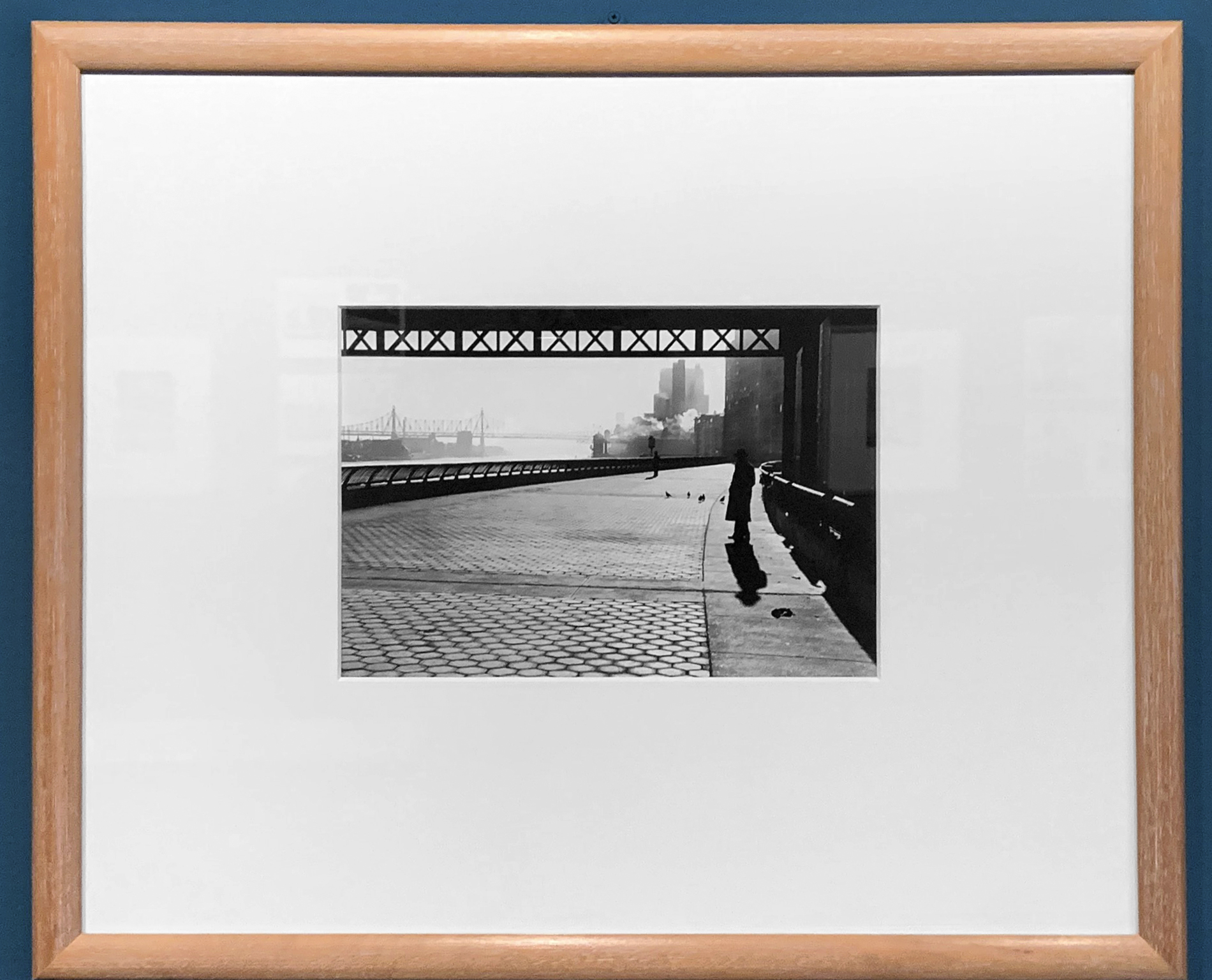

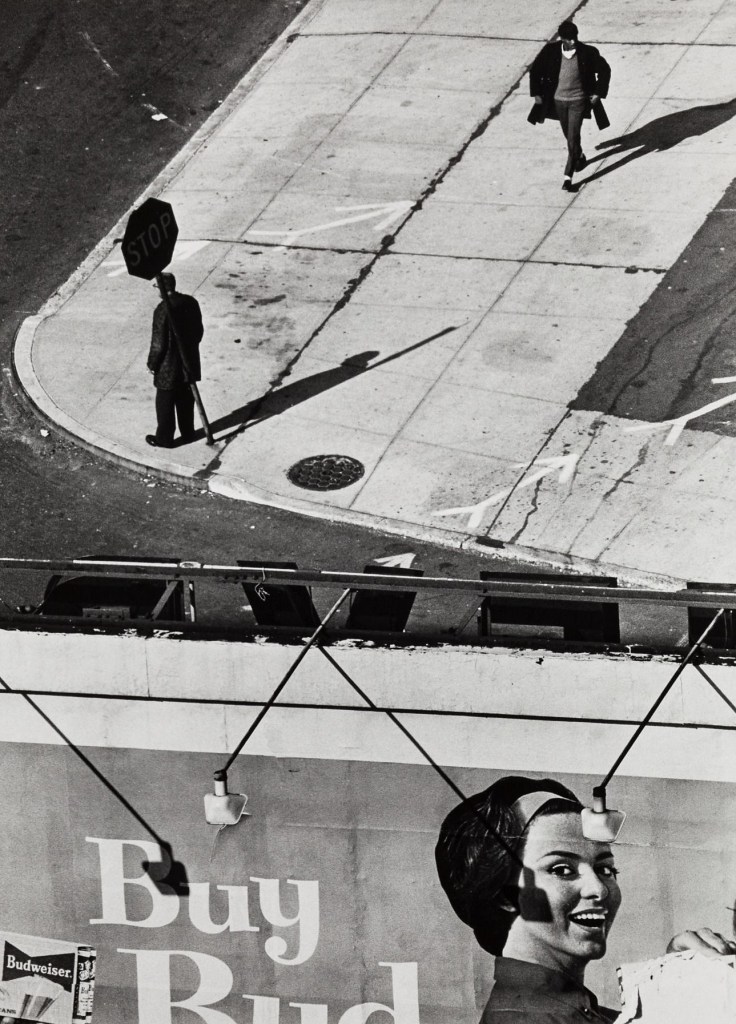

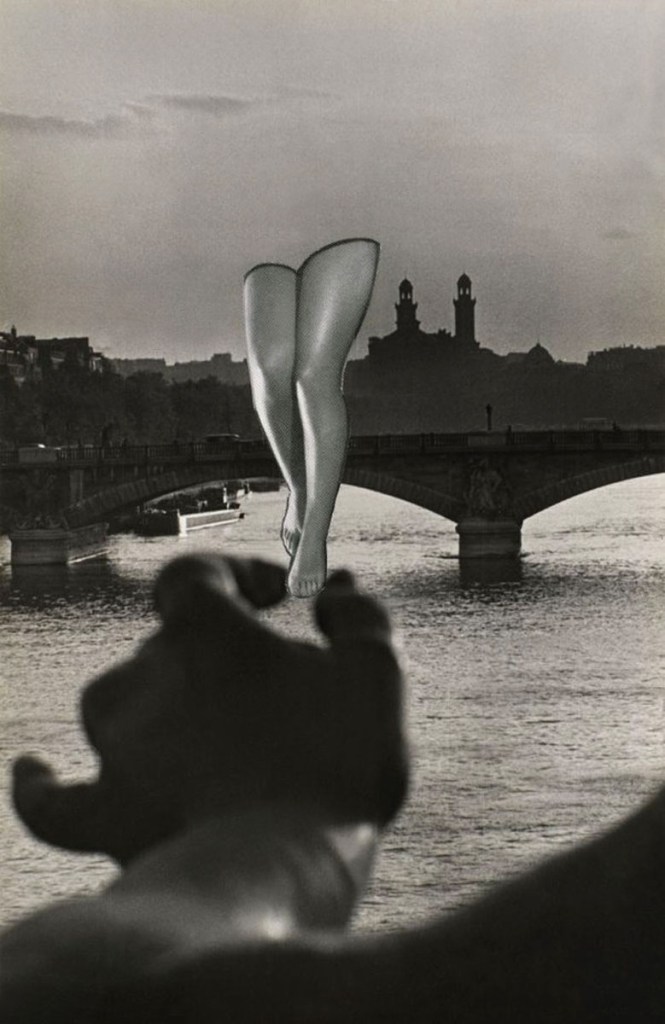

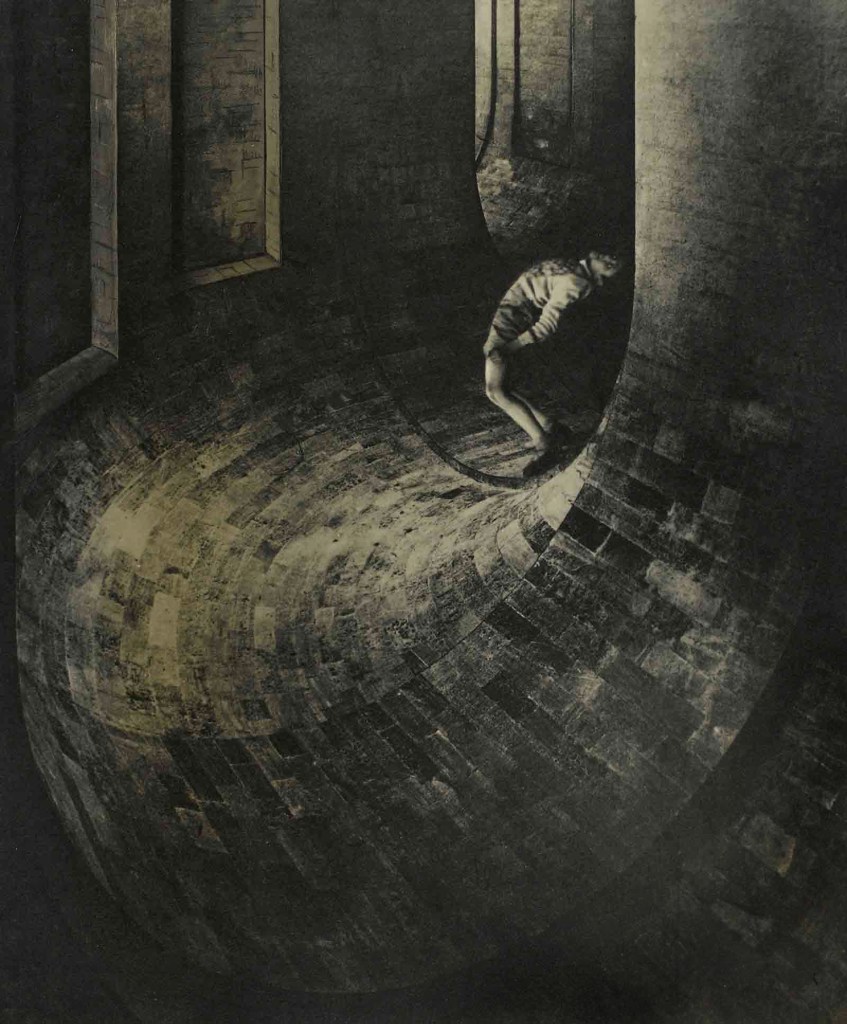

The availability of smaller, lightweight cameras spurred a number of women photographers to explore the city and the diversity of urban experience outside the studio. The exhibition features stunning street scenes and architectural views by Alice Brill, Rebecca Lepkoff, Helen Levitt, Lisette Model, Genevieve Naylor, and Tazue Satō Matsunaga, among others. Creative formal approaches – such as photomontage, photograms, unconventional cropping, and dizzying camera angles – came to define photography during this period. On view are experimental works by such artists as Valentina Kulagina, Dora Maar, Tina Modotti, Lucia Moholy, Toshiko Okanoue, and Grete Stern, all of whom pushed the boundaries of the medium.

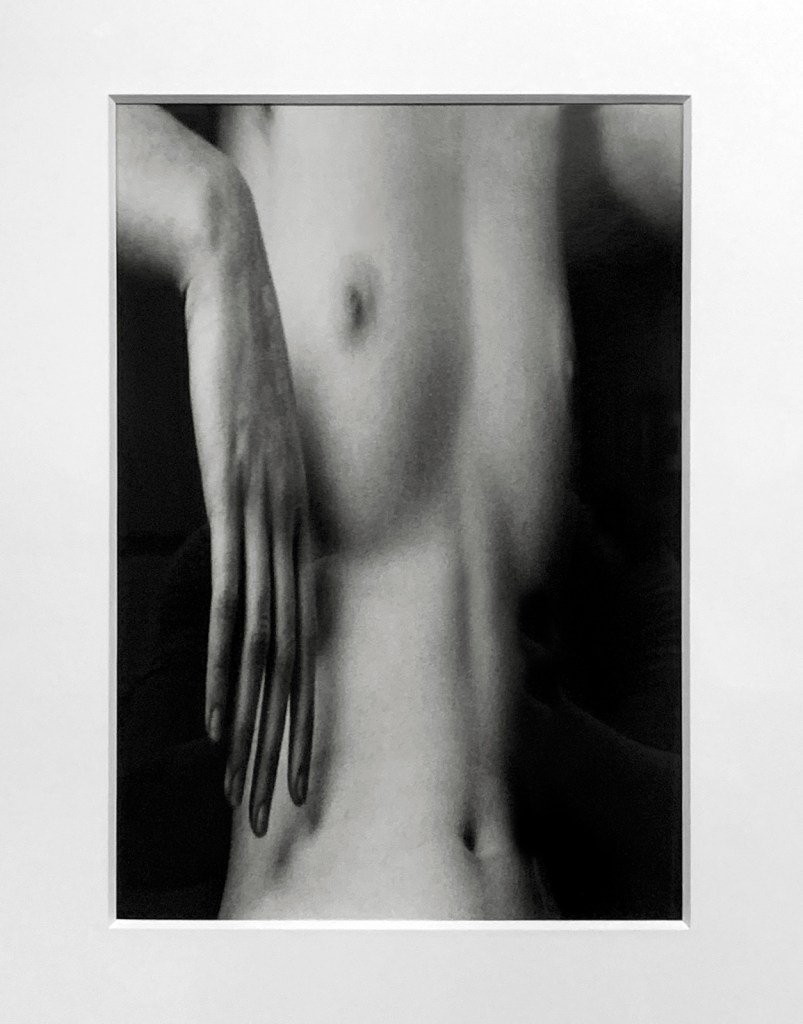

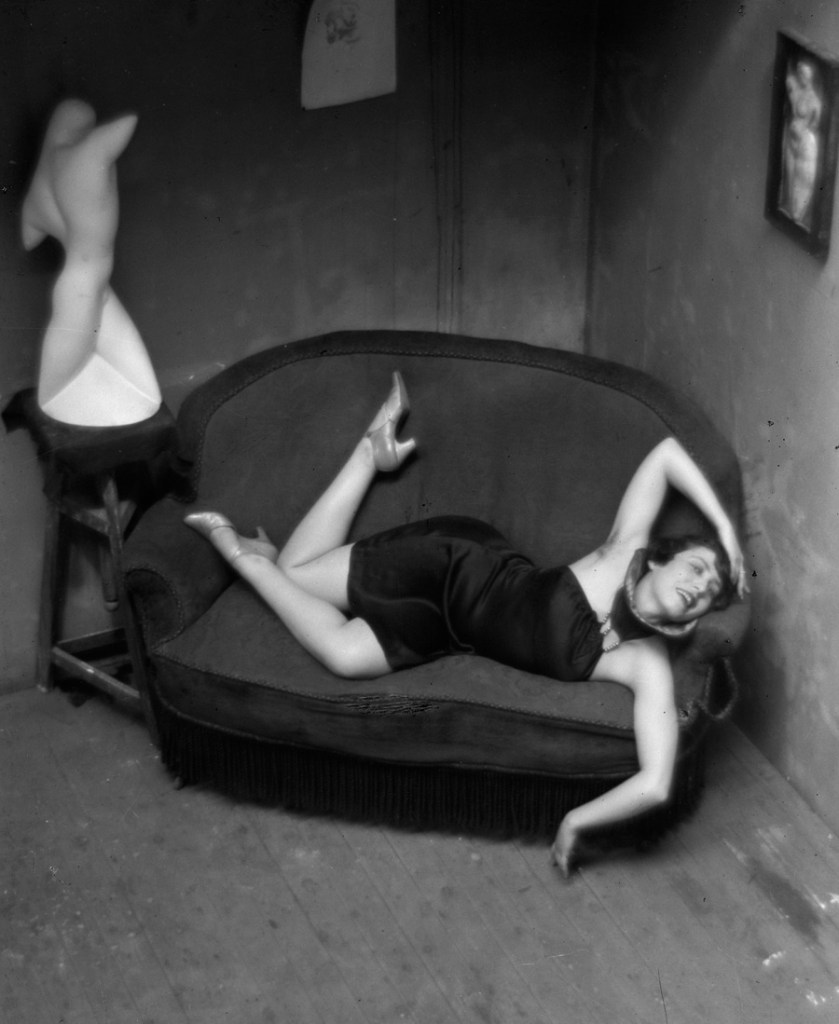

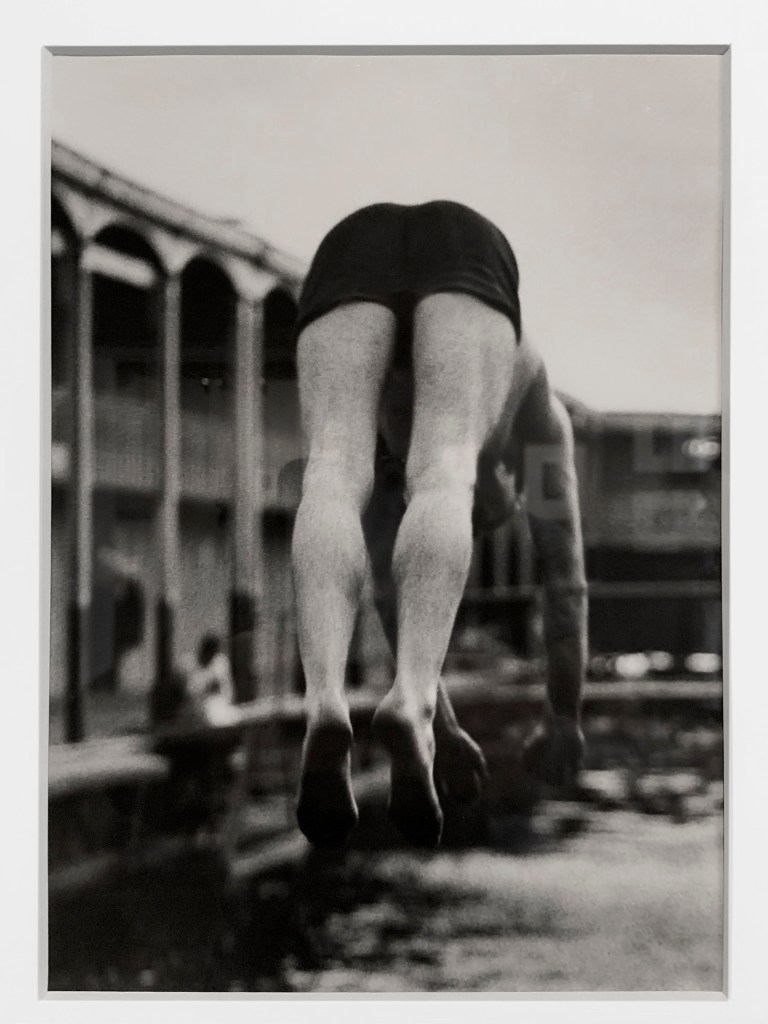

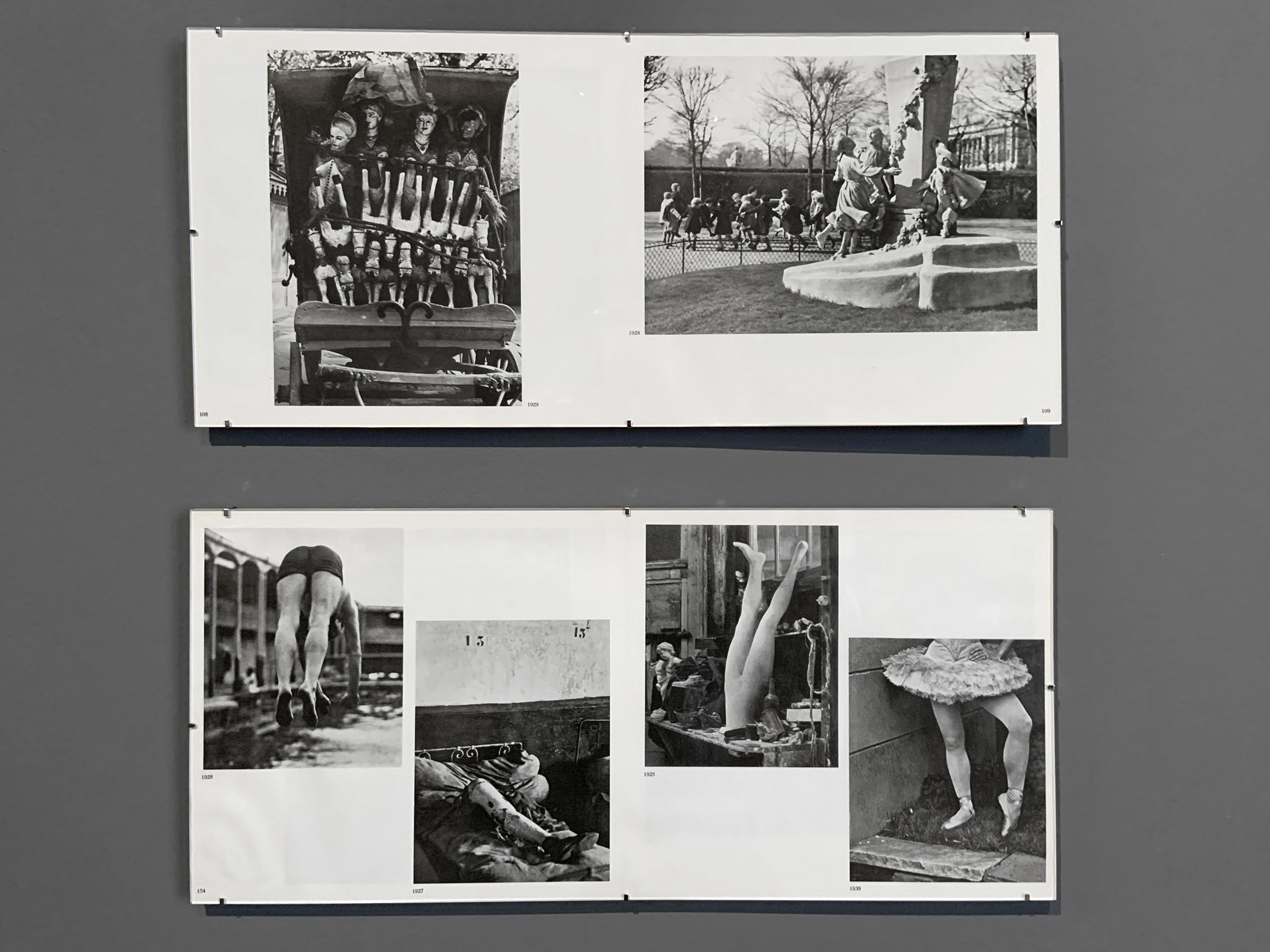

During this period, many women traveled extensively for the first time and took photographs documenting their experiences abroad in Africa, China, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. Others, including Marjorie Content, Eslanda Goode Robeson, and Anna Riwkin, engaged in more formal ethnographic projects. This period also gave rise to new ideas about health and sexuality and to changing attitudes about movement and dress. Women photographers such as Lotte Jacobi, Jeanne Mandello, and Germaine Krull produced images of liberated modern bodies, from pioneering photographs of the nude to exuberant pictures of sport and dance.

The unprecedented demand for fashion and advertising pictures between the world wars provided new employment opportunities for many female photographers, including Lillian Bassman, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Toni Frissell, Frances McLaughlin-Gill, Margaret Watkins, Caroline Whiting Fellows, and Yva. Fashion magazines such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar visually defined the tastes and aspirations of the New Woman and offered a space in which women could experiment with pictures intended for a predominantly female readership.

The rise of the picture press also established photojournalism and social documentary photography as dominant forms of visual expression. Galvanised by the effects of a global economic crisis and growing political unrest, many women photographers, including Lucy Ashjian, Margaret Bourke-White, Kati Horna, Dorothea Lange, and Hansel Mieth, created powerful images that exposed injustice and swayed public opinion. While women photojournalists often received so-called “soft assignments” on the home front, others risked their lives on the battlefield. The exhibition features combat photographs by Thérèse Bonney, Galina Sanko, and Gerda Taro, as well as unsparing views of the liberation of Nazi concentration camps by Lee Miller. Views of Hiroshima by Tsuneko Sasamoto and photographs of the newly formed People’s Republic of China by Hou Bo and Niu Weiyu underscore the global complexities of the postwar era.

Credits

The New Woman Behind the Camera is curated by Andrea Nelson, Associate Curator in the Department of Photographs, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The Met’s presentation is organised by Mia Fineman, Curator, with Virginia McBride, Research Assistant, both in the Department of Photographs.

Following its presentation at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the exhibition will travel to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., where it will be on view from October 31, 2021 through January 30, 2022. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue, published by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and distributed by DelMonico Books.

Press release from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

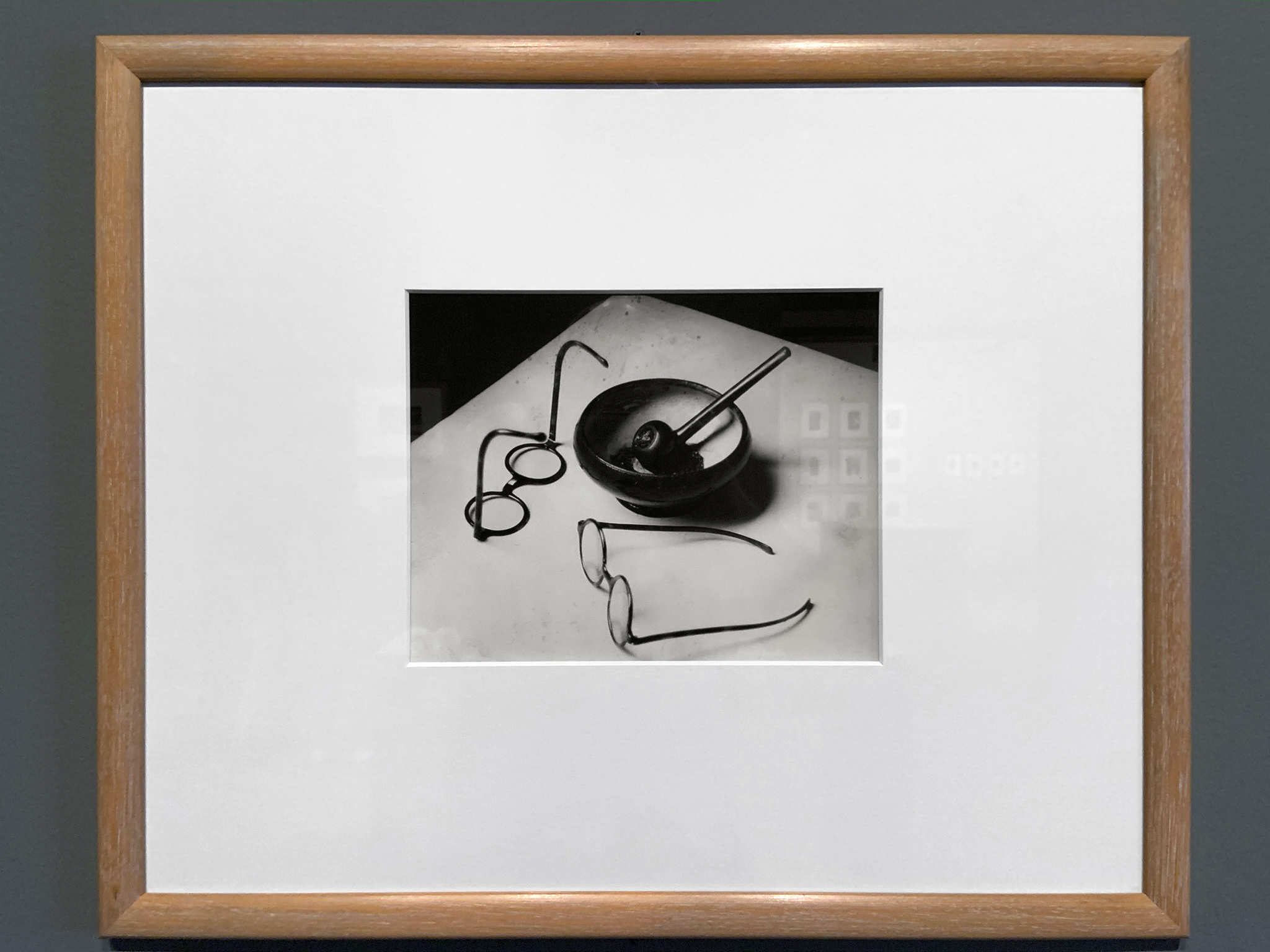

Elizabeth Buehrmann (American, 1886-1965)

Advertisement for Robert Burns Cigar

c. 1920

Gelatin silver print mounted in press book

Image: 19.69 x 18.42cm (7 3/4 x 7 1/4 in.)

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library

Elizabeth Buehrmann (1886-1965)

Elizabeth “Bessie” Buehrmann (1886-1965) was born June 13, 1886, in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. Elizabeth was an American photographer and artist who was one of the pioneers of taking formal portraits of people in their own homes rather than in a studio. …

At about the age of 15 she enrolled in painting and drawing classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. While she was still a teenager she began assisting Eva Watson-Schütze in her photography studio on West 57th Street, and it was there that she learned both the technical and aesthetic aspects of photography. She made such progress that by the time she was just 18 years old she was accepted as an Associate Member in Alfred Stieglitz’s important Photo-Secession.

Buehrmann specialised in taking portraits of clients in their homes, and she never used artificial scenery or props. She said “I have never had a studio at home but take my pictures in houses. A person is always much more apt to be natural, and then I can get different background effects.” She also did not pose her subjects; instead she would “spend several hours getting acquainted with her subjects before attempting to reproduce the character found in an interesting face.” Leading businessmen and diplomats commissioned her as well as prominent society women, and she was well known for both her artistry and her ability to capture “some of the soul along with the physical features of her sitters.”

In 1906-1907 she spent a year living in London and Paris in order to learn the latest techniques and styles of European photographers. As another sign of her prominence, she was invited to join the Photo-Club de Paris, where she worked for several months.

When she returned, the Art Institute of Chicago gave her a large exhibition of 61 prints, including portraits, landscapes and still lifes. Included among her portraits were photographs of Alvin Langdon Coburn, Robert Demachy, Russell Thorndike, Fannie Zeisler, Sydney Greenstreet and Helena Modjeska.

In 1909 Stieglitz included three of her prints in the prominent National Arts Club exhibition which he organised. Another photographer, Robert Demachy, insisted her prints be included in an important show he was organising in Paris the next year. She is shown as still living with her parents, in Chicago, in the 1910 census. She continued doing portraiture until the late 1910s when she began exploring the then relatively new market for advertising photography. She spent the next decade working on a variety of advertising commissions. Her last known commercial photography took place in the early 1930s.

Text from the Wikipedia website

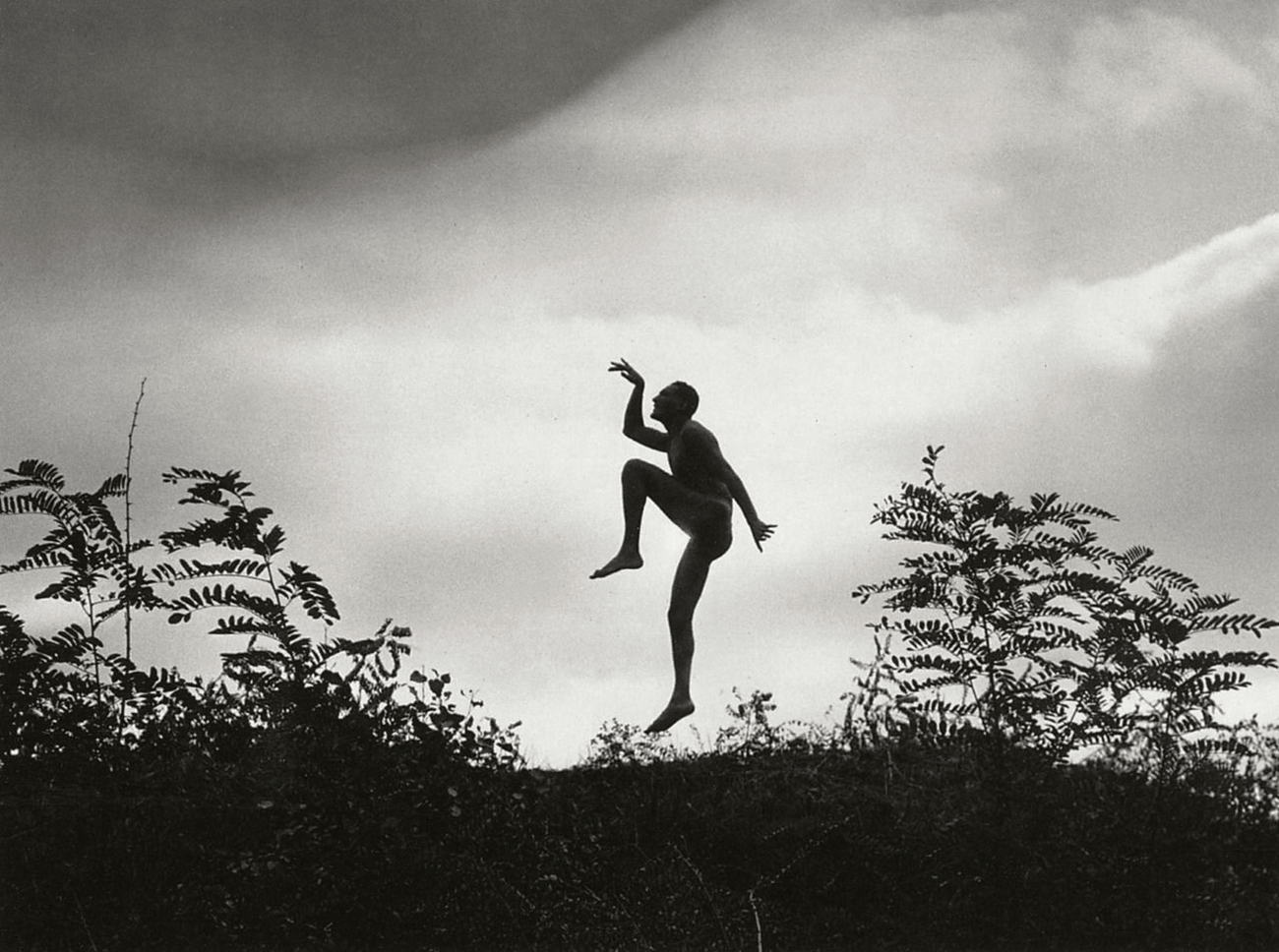

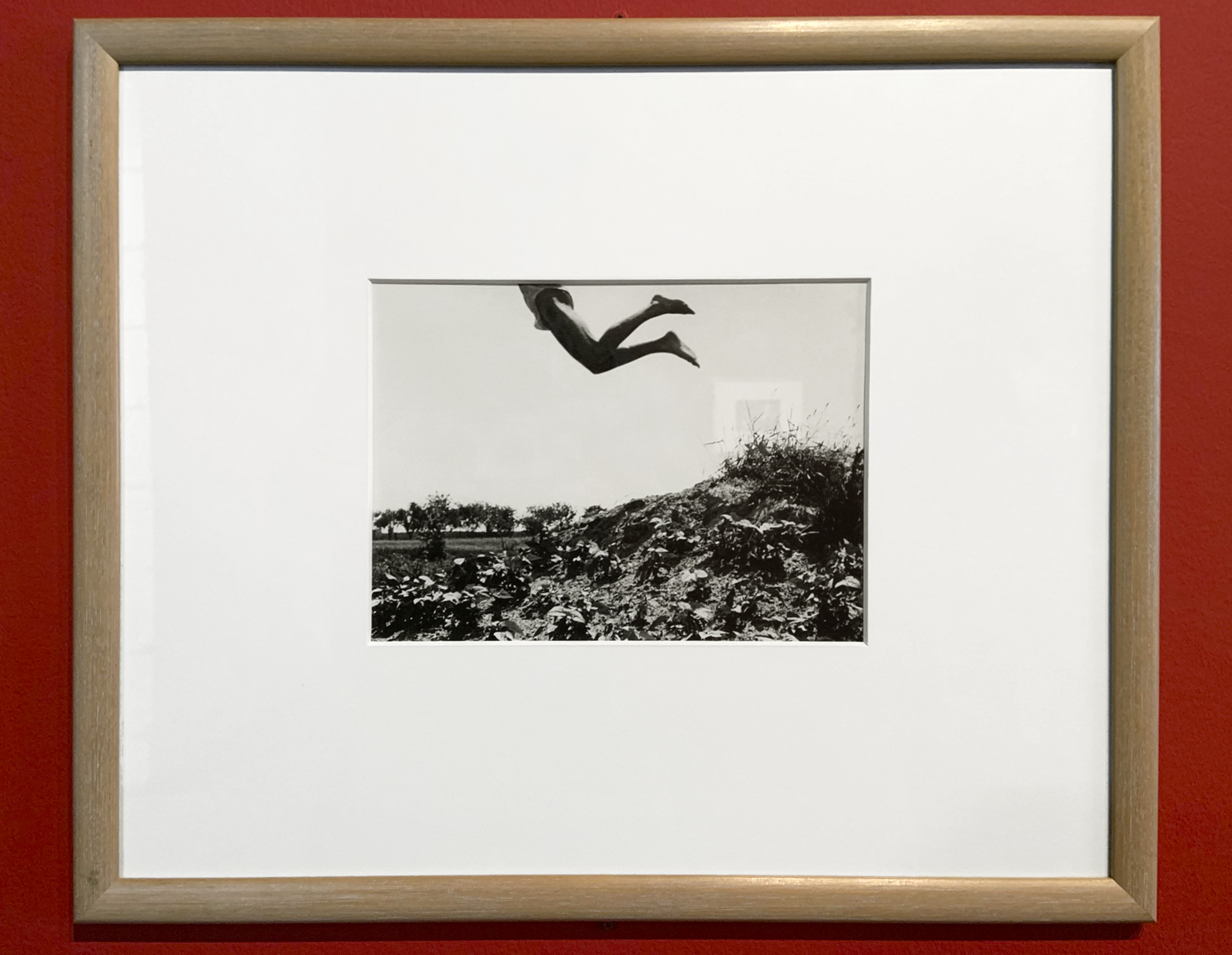

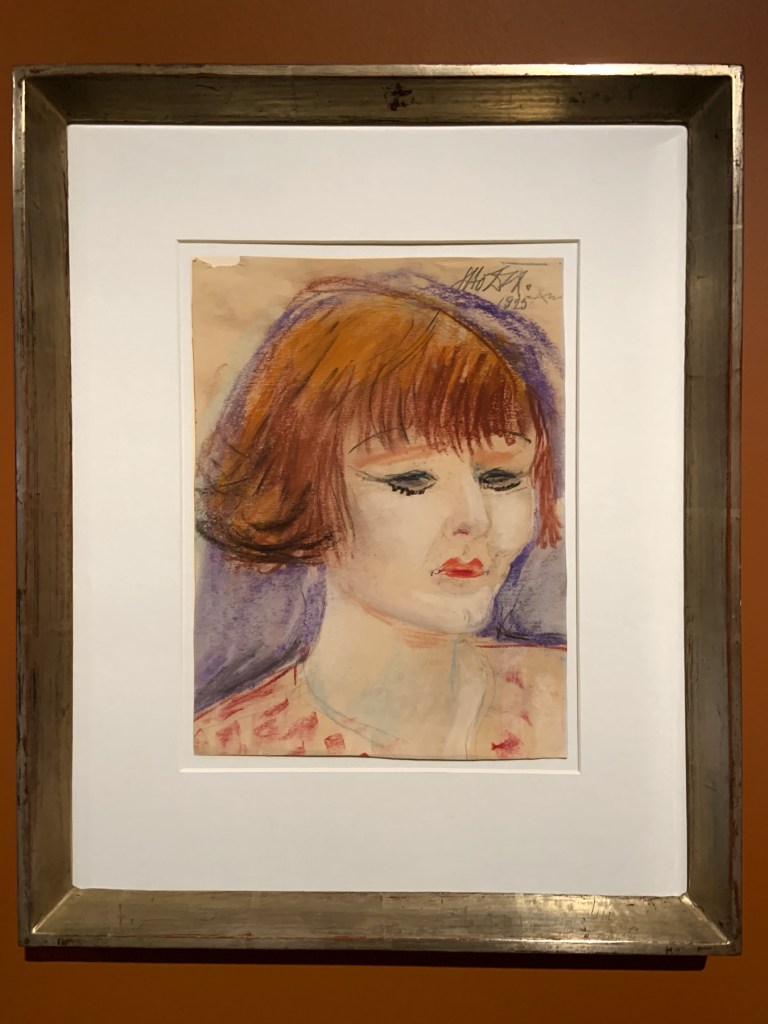

Charlotte Rudolph (German, 1896-1983)

Gret Palucca

1925

Gelatin silver print

8 13/16 × 6 9/16 in. (22.4 × 16.6cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

Charlotte Rudolph (German, 1896-1983)

Charlotte Rudolph (1896-1983) was a German photographer. After training with Hugo Erfurth, Charlotte Rudolph opened a photo studio in Dresden in 1924 and concentrated on portrait and dance photography. In particular, Rudolph became known through her photographs of dancers such as Gret Palucca, with whom she was friends, Mary Wigman , Vera Skoronel and countless Wigman students such as Chinita Ullmann.

Her photos of the avant-garde German dancers of the 1920s and 1930s are among the most important documents of expressive dance today. In contrast to other photographers, Charlotte Rudolph did not take the dancers in a pose, but in action. Her pictures of Gret Palucca’s jumps made a major contribution to Palucca’s international fame in 1924 and were also Charlotte Rudolph’s breakthrough. As a result, many women went to their studio because they were hoping for such jump pictures from Rudolph.

Charlotte Rudolph continued to work in Germany during the Nazi era, and temporarily also in the USA after the Second World War. Her archives and her studio in Dresden, which she took over in 1938 after the death of Genja Jonas, were destroyed in the Second World War when Dresden was bombed on February 13, 1945.

Text from the German Wikipedia website

Gret Palucca, born Margarethe Paluka (8 January 1902 – 22 March 1993), was a German dancer and dance teacher, notable for her dance school, the Palucca School of Dance, founded in Dresden in 1925.

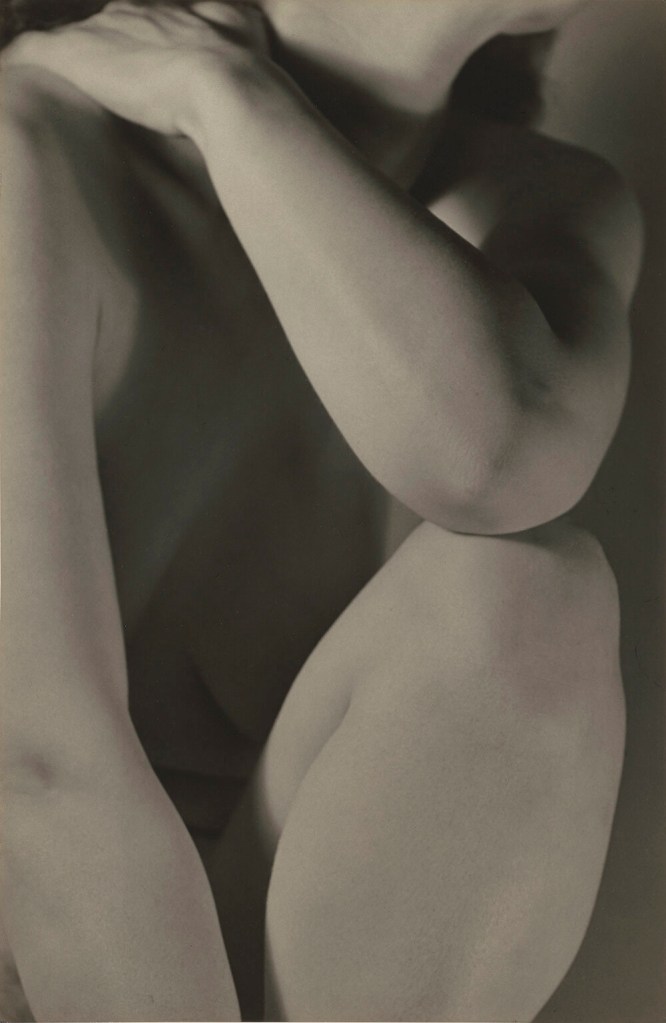

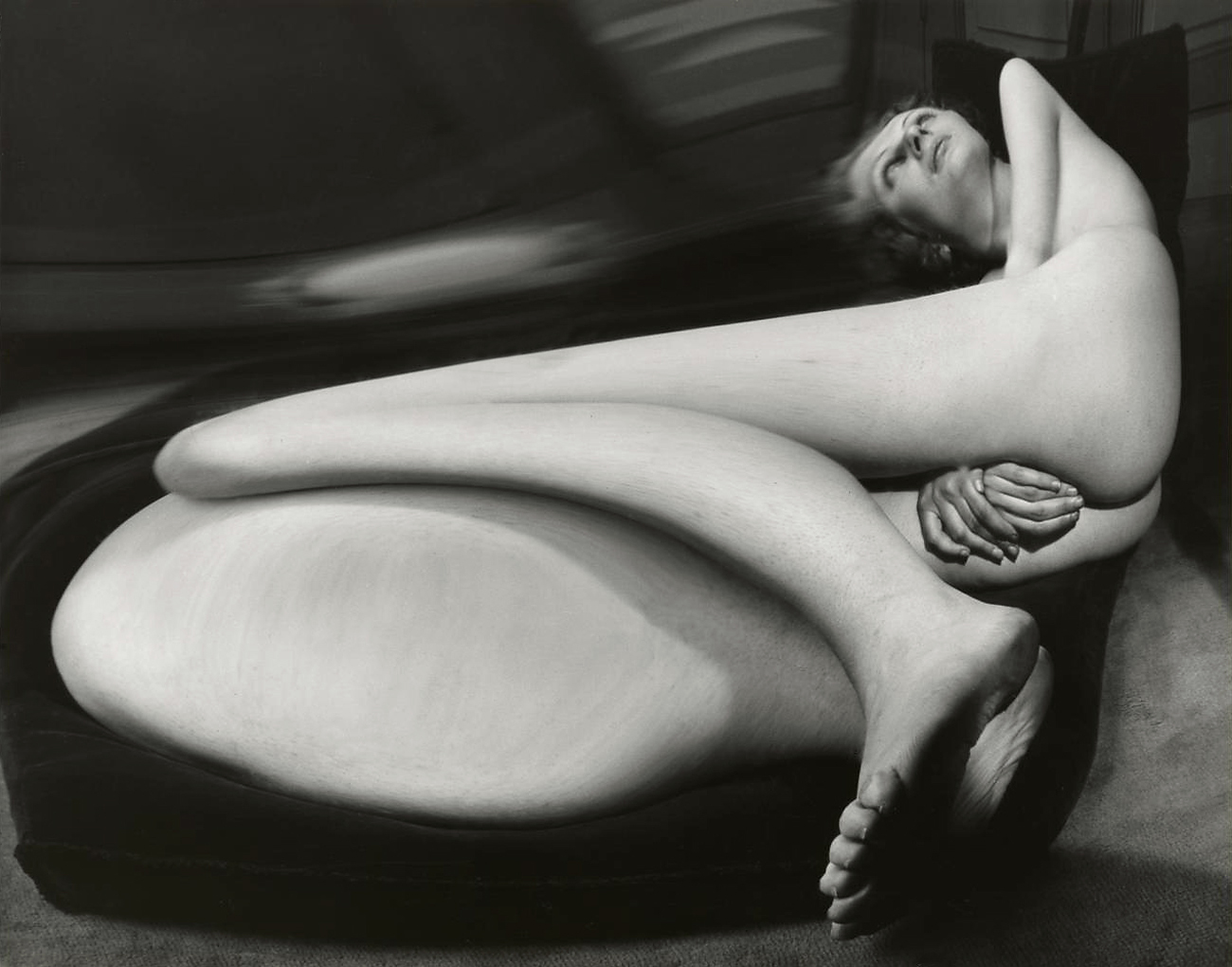

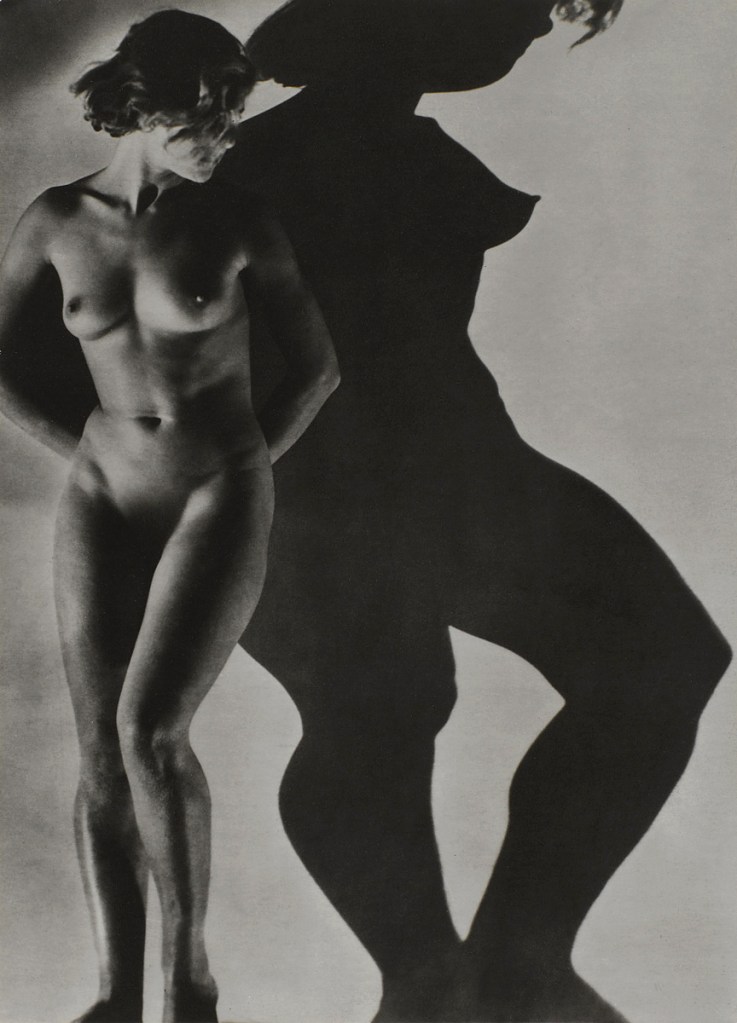

Yvonne Chevalier (French, 1899-1982)

Nu (Nude)

1929

Gelatin silver print

15 3/8 × 10 1/8 in. (39 × 25.7cm)

© National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

Yvonne Chevalier (French, 1899-1982)

Yvonne Chevalier (French, 1899-1982). Coming from a well-to-do background, Yvonne Chevalier went to study drawing and painting after high school. Her first photographs of seascapes and cliffs date back to 1909. She married a doctor in 1920, with whom she had a daughter the following year. She and her husband welcomed and socialised with many artists and writers, including her friends Colette (1873-1954), Adrienne Monnier (1892-1955) and Mariette Lydis (1887-1990), whom she photographed. In 1929 she devoted herself entirely to her art and in 1930 she opened a portrait studio which was a great success. She became the official photographer of painter Georges Rouault. In 1936 she joined the association of French illustrator and advertising photographers, Le Rectangle, founded by Emmanuel Sougez, René Servant and Pierre Adam, which demanded a return to classicism.

The artist exhibited her photos of nudes, architecture and landscapes during two solo exhibitions, in 1935 and 1937. She explored portraiture and photojournalism (Algeria and Southern France, 1937), worked on sculpture (Rodin, 1935), architecture (Thoronet Abbey, 1936) and objects, particularly musical instruments. She tightly framed images – hands, for example – and used high- and low-angle shots, close-ups, shadow and light effects. In 1932 her portrait of Colette submerged in almost total darkness left only the writer’s eye fully illuminated. Included in many group exhibitions, she also regularly published in various magazines, such as Arts et métiers graphiques, Cinégraph and Musica. Following the bombings of of the Second World War, the majority of her works disappeared in a fire.

In 1946 she became one of the founding members of the group XV, which wanted photography to be recognised as an art in and of itself. She exhibited with this group on several occasions. Together with the writer Marcelle Auclair, in 1949 she made a long report on the Spanish Carmelites to commemorate the foundation of the order by Teresa of Avila. She continued working extensively as a book illustrator, but stopped taking photographs in 1970. In 1980 the artist sorted and destroyed a large number of her prints.

Catherine Gonnard

Translated from French by Katia Porro.

From the Dictionnaire universel des créatrices

© 2013 Des femmes – Antoinette Fouque

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

Catherine Gonnard. “Yvonne Chevalier,” on the AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions website [Online] Cited 24/08/2021

Karimeh Abbud (Palestinian, 1893-1940)

Three Women

1930s

Gelatin silver print

3 1/2 × 5 1/2 in. (8.9 × 14 cm)

Issam Nassar

Gertrud Arndt (German born Poland, 1903-2000)

Masked Self-Portrait (No. 16)

1930

Gelatin silver print

8 15/16 × 6 15/16 in. (22.7 × 17.6cm)

Museum Folkwang, Essen

Costuming played a central role at the Bauhaus. From the very beginning, masquerade balls were celebrated regularly under a wide variety of mottoes. And the Bauhaus people rushed over, sometimes preparing for weeks in the workshops and privately the Bauhaus festivals that were popular beyond the walls of the school: Decorations, demonstrations, but above all their costumes – made of simple materials – transformed the Bauhaus people into miraculous figures, incarnate objects and masked beings. Gertrud Arndt’s mask photographs (a series of 43 self-portraits) derive directly from these Bauhaus festivals. …

Arndt’s mask photos are private photographs and were never intended for the public. The mask photographs were taken, rather, independently of viewers, as an experimental excursion into the possibilities and limits of one’s own face – and into the many different characters Arndt transformed herself into in her pictures. They are the record of an intimate conversation conducted between Arndt and her camera. The special thing about Gertrud Arndt’s mask photos is that they were taken in a comprehensive series. Within the 43 photos in the series, smaller picture series can be recognized. In her mask photos, Gertrud Arndt developed a kind of external image of herself, a “visual identity.”12 Arndt only rarely photographed herself once in the same costume. She often made two, three or four pictures in the same costume (or with minor changes). Here the pose, facial expression or picture detail change. In a series of three pictures within the series, Arndt shows herself in a high-necked top with a frill collar and hat, frontally with her eyes closed, then looking directly into the camera in a half-profile, and finally posing in a larger frame with a surprised facial expression. In another mini-series consisting of two photos, Arndt once photographed herself with her eyes closed, her head raised high, and in the next picture, squinting at her nose. The true woman behind the façade is not visible to the viewer. The pictures can illustrate the conflict women faced during the Weimar Republic: faced by entrenched, conservative notions of femininity on the one hand while opposed models for how a modern emancipated woman might act were also present, if to a lesser degree. The contradictory models available within society may be one source behind Arndt’s decision to use her mask photographs as a means to observe herself from the outside, as it were, and to investigate to what degree the many women into whom she transformed herself were actually part of her own feminine persona. At the same time, perhaps unconsciously, she may have also used her portrait project in the service of the traditionally feminine image expected of her, which also did not necessarily correspond to reality. Stereotypical ideas of womanhood with broad social currency circulating during the Weimar Republic included conservative images of women – such as the wife and mother, the widow and the naïve young girl – and these clichés are present in Arndt’s photographs. Or was it that she deliberately exaggerated these role models because she herself felt like a “non-doer” at the Bauhaus, was uncomfortable in this role and felt herself degraded by being thought thusly when her own self-image was that of an emancipated a modern woman? And then again, perhaps Gertrud Arndt’s mask photos are actually merely the result of her “boredom,” which she was desperately trying to alleviate, with role plays.

Extract from Anja Guttenberger. “Festive and Theatrical: The Mask Photos of Gertrud Arndt and Josef Albers as an Expression of Festival Culture,” on the Bauhaus Imaginista Journal website Nd [Online] Cited 16/09/2021

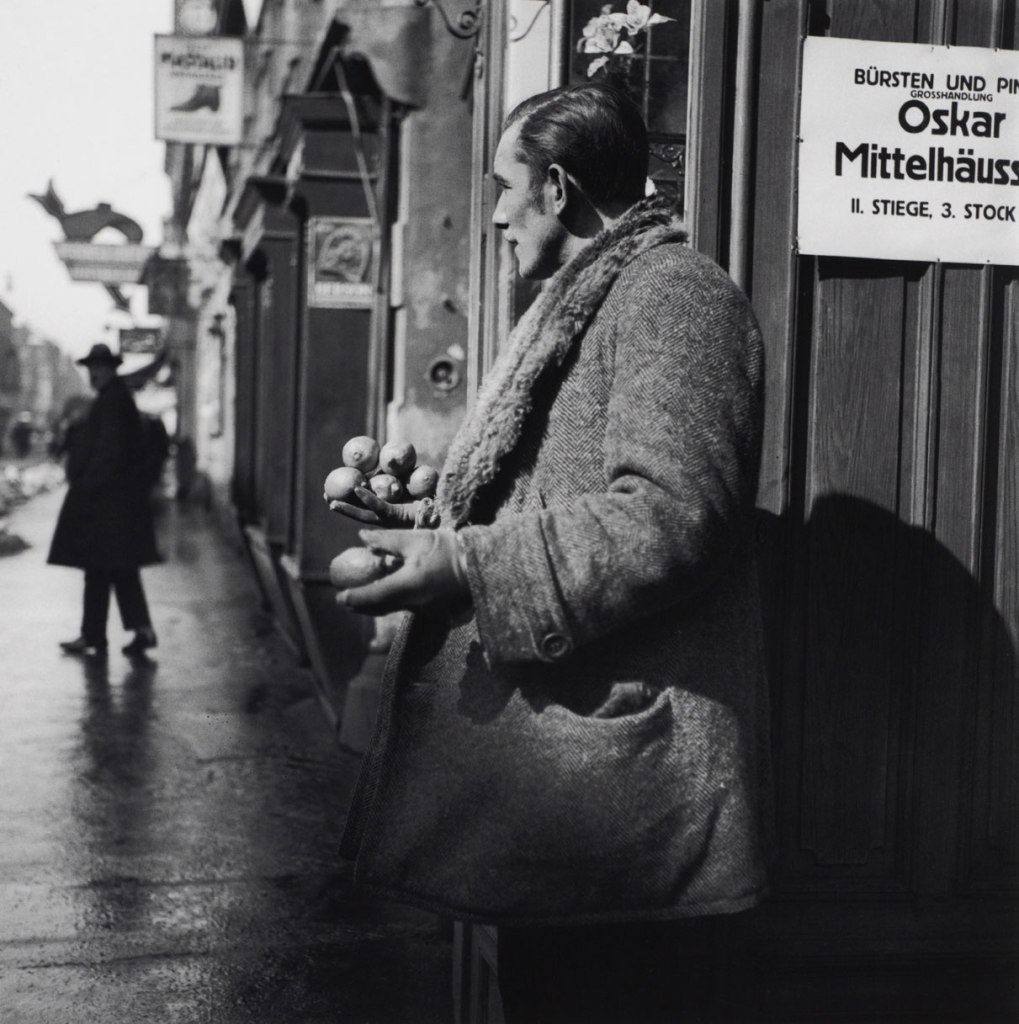

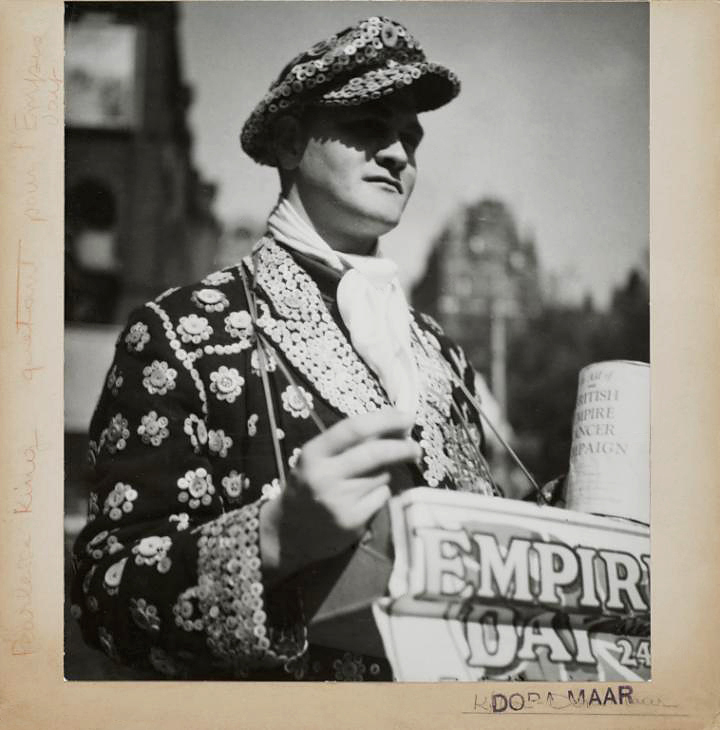

Edith Tudor-Hart (Austrian-British, 1908–1973)

Man Selling Lemons, Vienna

c. 1932, printed later

Gelatin silver print

9 1/16 × 9 7/16 in. (23 × 24cm)

Collection of Peter Suschitzky. Julia Donat and Misha Donat

Edith Tudor-Hart (née Suschitzky; 28 August 1908 – 12 May 1973) was an Austrian-British photographer and spy for the Soviet Union. Brought up in a family of socialists, she trained in photography at Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus in Dessau, and carried her political ideals through her art. Through her connections with Arnold Deutsch, Tudor-Hart was instrumental in the recruiting of the Cambridge Spy ring which damaged British intelligence from World War II until the security services discovered all their identities by the mid-1960s. She recommended Litzi Friedmann and Kim Philby for recruitment by the KGB and acted as an intermediary for Anthony Blunt and Bob Stewart when the rezidentura at the Soviet Embassy in London suspended its operations in February 1940.

Text from the Wikipedia website

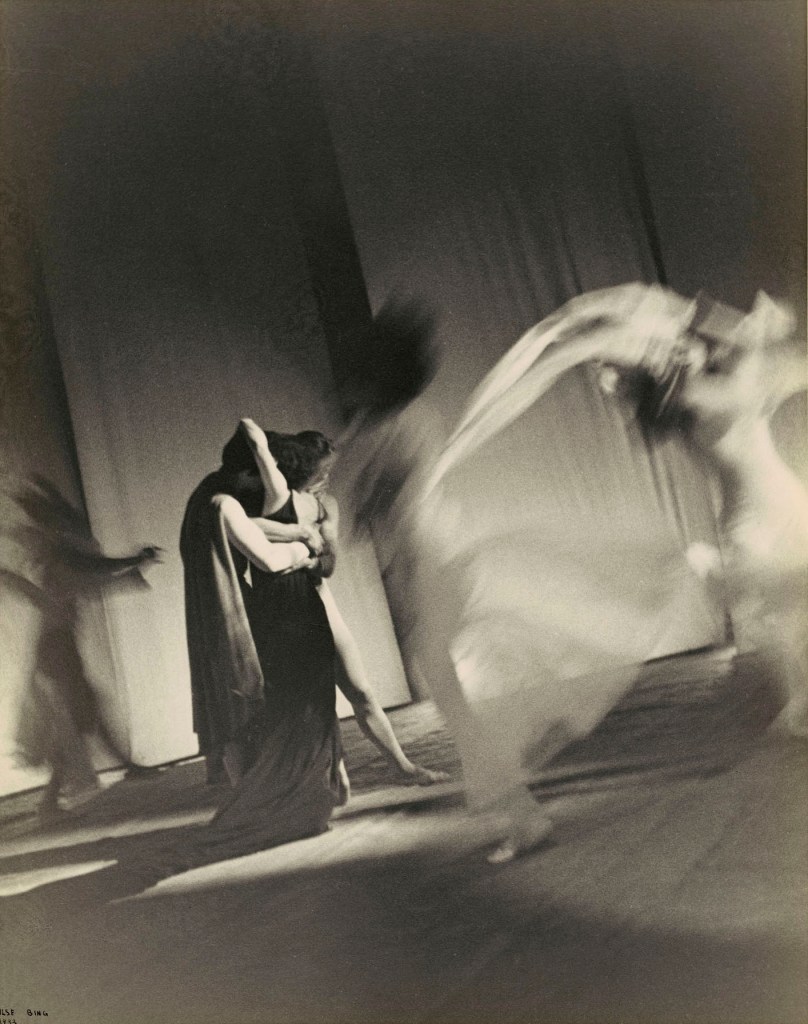

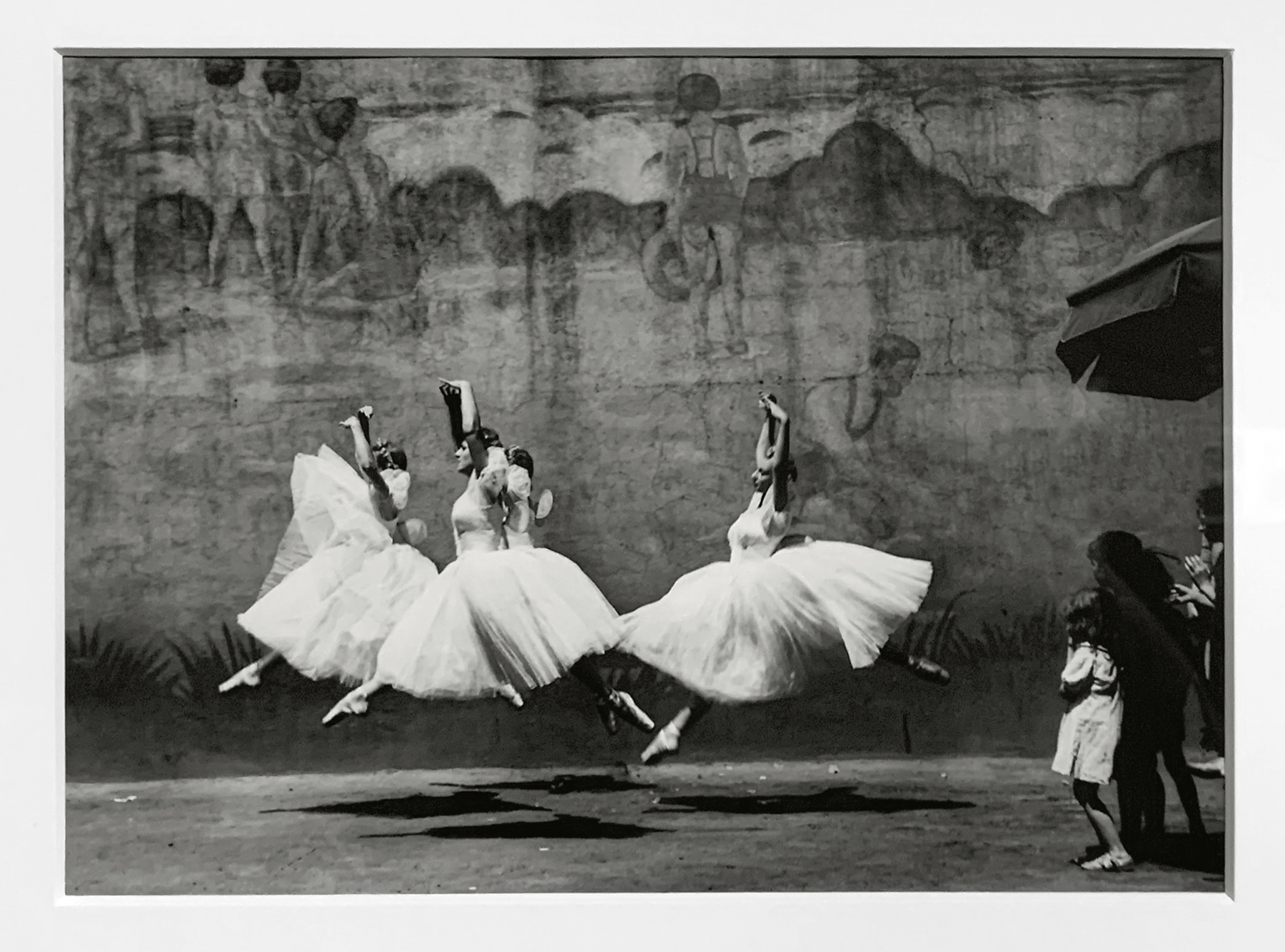

Ilse Bing (German, 1899-1998)

Ballet “L’Errante”, Paris

1933

Gelatin silver print

Image: 28.3 x 22.2 cm (11 1/8 x 8 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

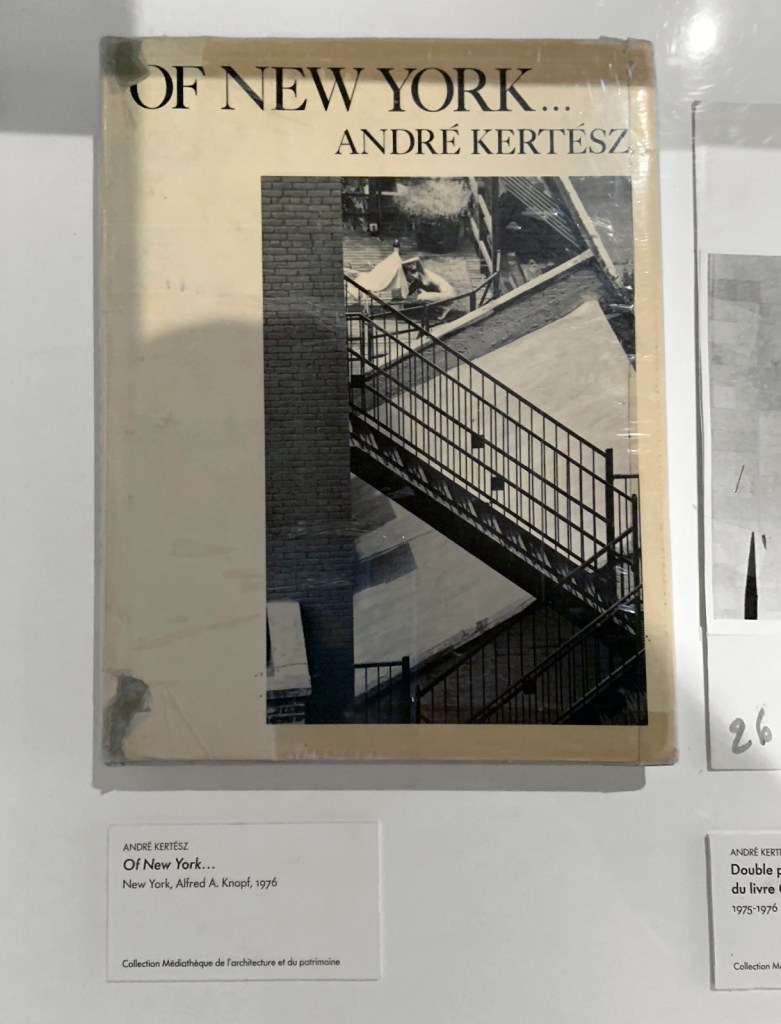

Andrea Nelson, an associate curator in the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC who conceived and organised the exhibition, says the idea for it arose after she was hired in 2010 and was ruminating about generating shows drawn from the NGA’s permanent collection. She was struck by a trove of 90 images by the interwar photographer Ilse Bing that were variously donated by the artist or left by her estate after Bing died in 1998. “She was actually one of the few women photographers that the National Gallery had collected in depth,” Nelson said in an interview. (The show, which was originally scheduled to open first at the NGA last September but was then deferred because of the coronavirus pandemic, travels there this autumn.)

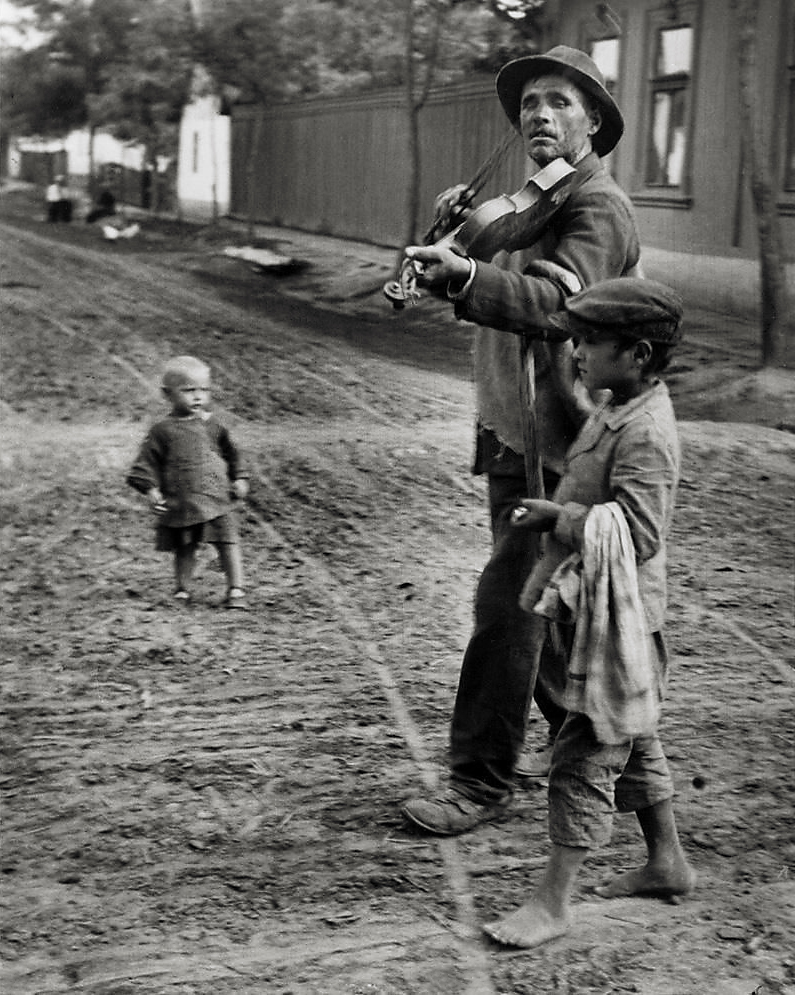

Born into a Jewish family in Frankfurt, Bing became interested in photography while creating architectural illustrations for her art history dissertation there, and eventually gave up her academic studies to pursue a career with the camera. She bought a Leica 35mm model in 1929 and moved the following year to Paris, where she met leading lights in avant-garde photography including Brassaï and André Kertész. Bing began experimenting compositionally and with light effects in self-portraits, images of Parisian streets and photographs of quotidian objects, followed by a striking series of pictures of dancers at the Moulin Rouge and other performers as well as commercial and fashion work in the burgeoning German and French magazine industry.

Known to the cognoscenti as “the Queen of the Leica”, she became a firmament in the constellation of Modernist photographers, included in important exhibitions in Paris and New York. Then the Second World War intervened, and Bing and her husband were both interned with other Jews in the south of France before fleeing to New York in 1941. Her photographic career gradually diminished after that, and she gave it up altogether in 1959.

Yet what she achieved from 1930 to 1940 remains a wonder to behold. “To me, she represents the established narrative of the interwar photographer,” says Nelson. “And as I began to dive deeper, I started to think about this larger community of women photographers who were entering the field, particularly in Germany and France. Did they have the same experiences as Bing, different experiences? But then I just started asking, wait a minute, was that true elsewhere [in the world]? What I really wanted to do was hopefully move beyond the Euro-American narrative that has really structured the history of photography.”

“I just felt that there wasn’t a look at the greater diversity of practitioners during the Modern period. So I took off down that road.”

Extract from Nancy Kenney. “Triumphant in their time, yet largely erased later: a Met exhibition explores ‘The New Woman Behind the Camera’,” on The Art Newspaper website 1st July 2021 [Online] Cited 22/07/2021

Germaine Krull (German, French, and Dutch (born Poland) 1897-1985 Wetzlar, Germany)

La Tour Eiffel (The Eiffel Tower)

c. 1928

Gelatin silver print

8 7/8 in. × 6 in. (22.5 × 15.2cm)

Museum Folkwang, Essen

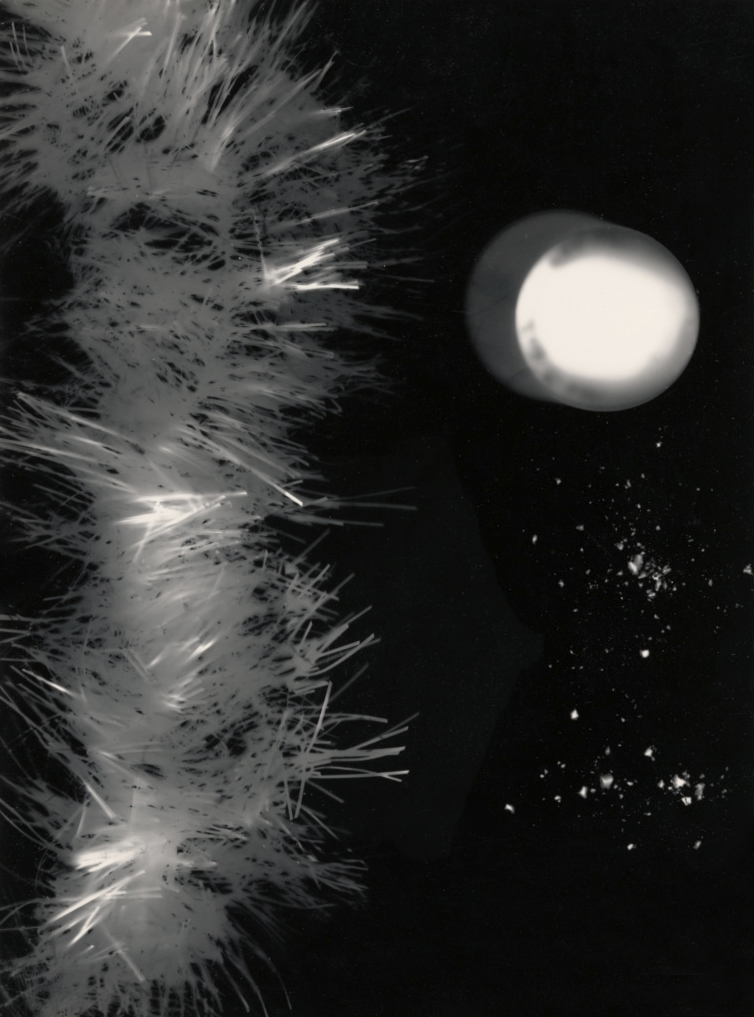

Elfriede Stegemeyer (German, 1908-1988)

Glühbirne, Spiralfeder, Quadrate und Kreise (Light Bulb, Spring, Squares, and Circles)

1934

Gelatin silver photogram

Image: 23.5 x 17.1cm (9 1/4 x 6 3/4 in.)

The Sir Elton John Photography Collection

From 1929 to 1932, Stegemeyer (German, 1908-1988) studied art in Berlin and Cologne. In Cologne she was involved in the activities of the Cologne Progressive art association together with Raoul Ubac, Heinrich Hoerle and others. From 1932 to 1938 Stegemeyer concentrated on photographic experiments such as cameraless photography, multiple exposure, photomontage and object studies. Meeting Raoul Hausmann in his Ibiza exile in 1935 nourished her photographic studies of landscape and rural architecture (also during travels in Eastern Europe in the late 1930s). Stegemeyer took part in underground political resistance activities in Nazi Germany, which led to her imprisonment in 1941. Her archive was destroyed during air raids in Berlin in 1943. After the war, Stegemeyer’s work shifted towards drawing, painting, writing and prize-winning animation. In her late work in the 1980s, the artist turned to montage work of different materials.

Text from the Kicken Berlin website [Online] Cited 16/09/2021

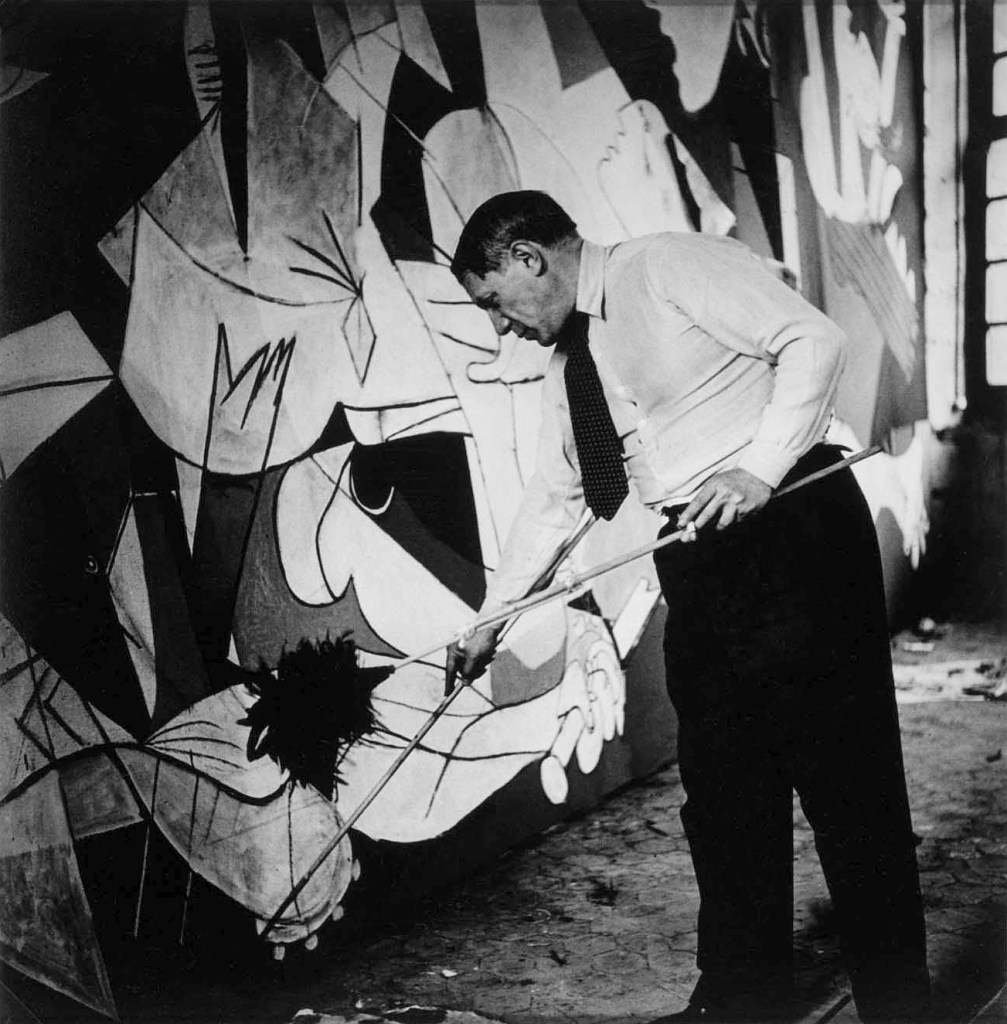

![Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997) '[Boy with a Cat]' 1934 Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997) '[Boy with a Cat]' 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/dora-maar-boy-with-a-cat.jpg?w=770)

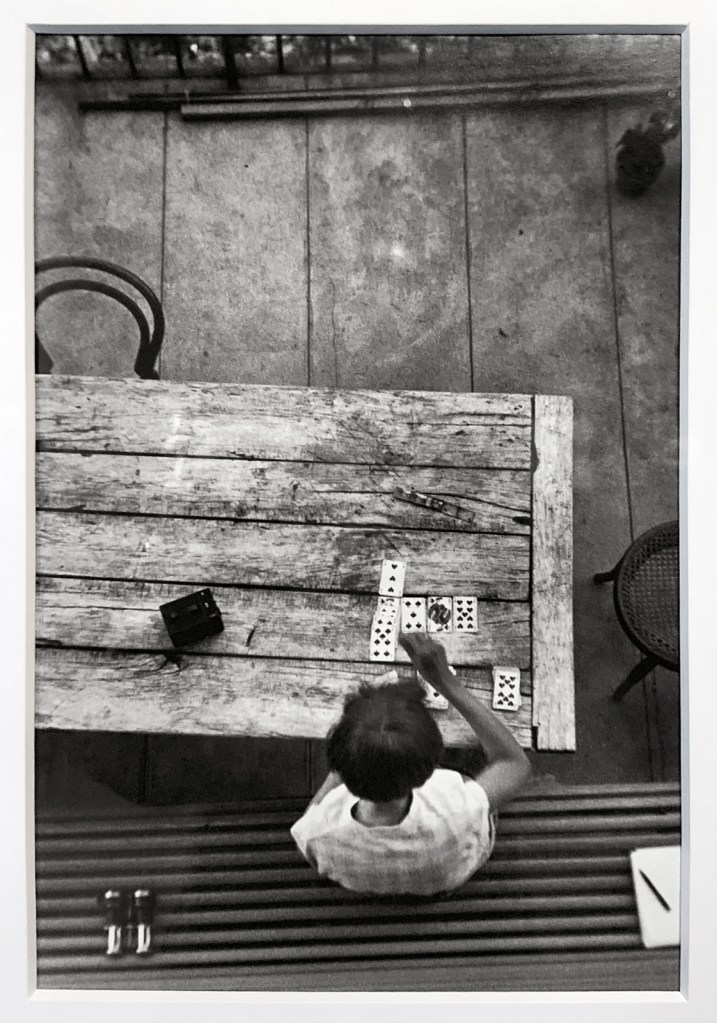

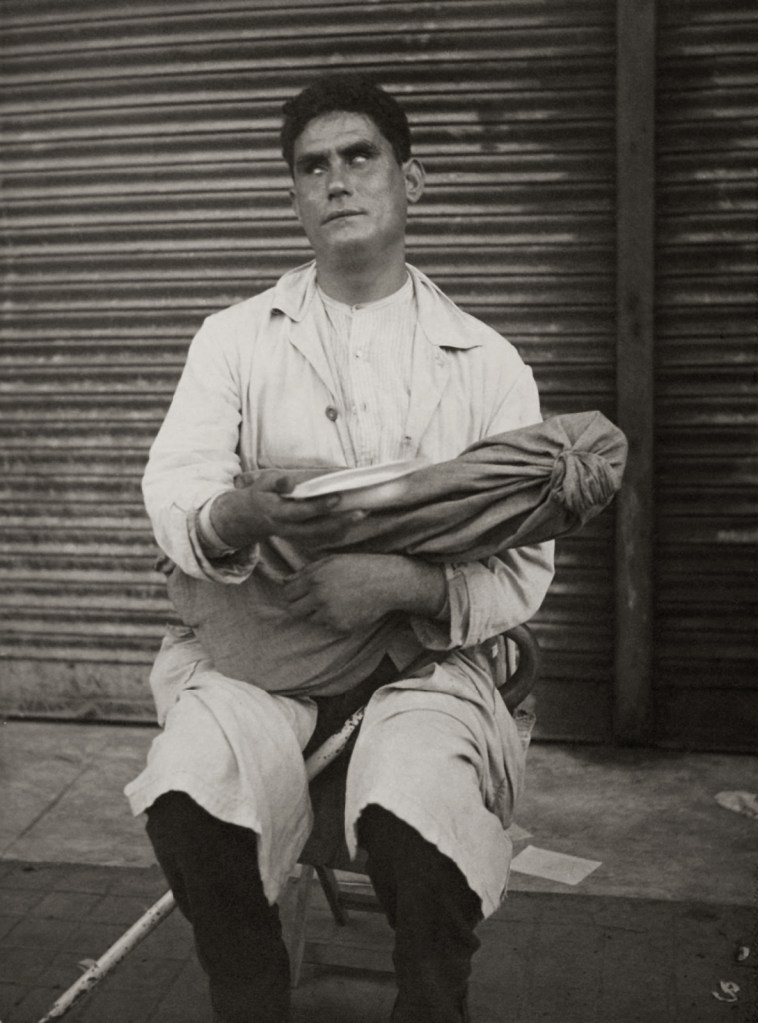

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

[Boy with a Cat]

1934

Gelatin silver print

16 5/16 × 11 7/16 in. (41.4 × 29cm)

Purchase, Twentieth-Century Photography Fund and Kurtz Family Foundation Gift, 2015

Metropolitan Museum of Art

© 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

From 1930 to 1934 Maar turned her camera to the inhabitants of the streets of Paris and London, blending documentary and Surrealist modes. Her photographs often focus on socially marginal figures such as the poor or disabled, revealing her own political engagement. In this striking image, an adolescent with rumpled hair protectively grasps a cat to his chest, his gaze challenging Maar’s camera. The boy’s expression and posture imbue this chance encounter – and the composition – with an arresting psychological dimension.

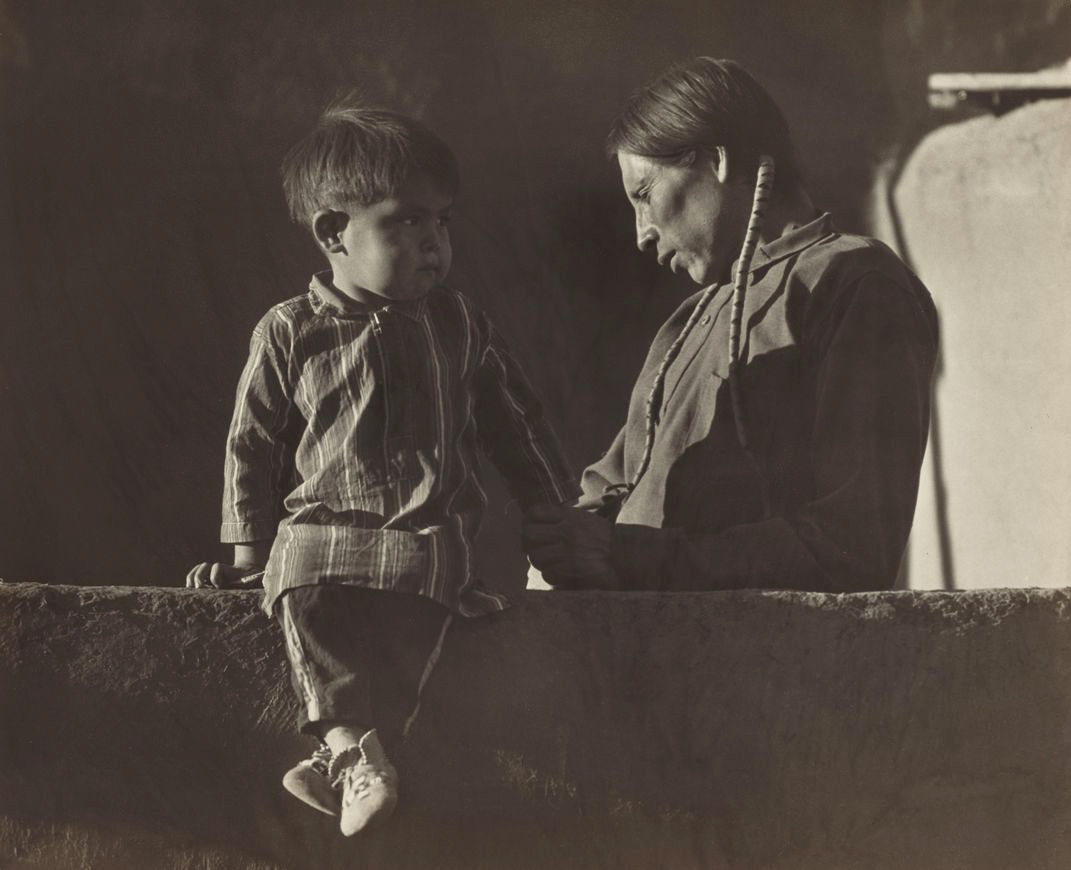

Marjorie Content (American, 1895-1984)

Adam Trujillo and His Son Pat, Taos

Summer 1933

Gelatin silver print

4 1/2 × 5 9/16 in. (11.5 × 14.2 cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Purchased as the Gift of the Gallery Girls

Marjorie Content (1895-1984) was an American photographer from New York City active in modernist social and artistic circles. Her photographs were rarely published and never exhibited in her lifetime. Since the late 20th century, collectors and art historians have taken renewed interest in her work. Her photographs have been collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Chrysler Museum of Art; her work has been the subject of several solo exhibitions.

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

Fort Peck Dam, Montana

1936

Gelatin silver print

12 15/16 × 10 13/16 in. (32.9 × 27.4cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Patrons’ Permanent Fund

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

World’s Highest Standard of Living

1937

Gelatin silver print

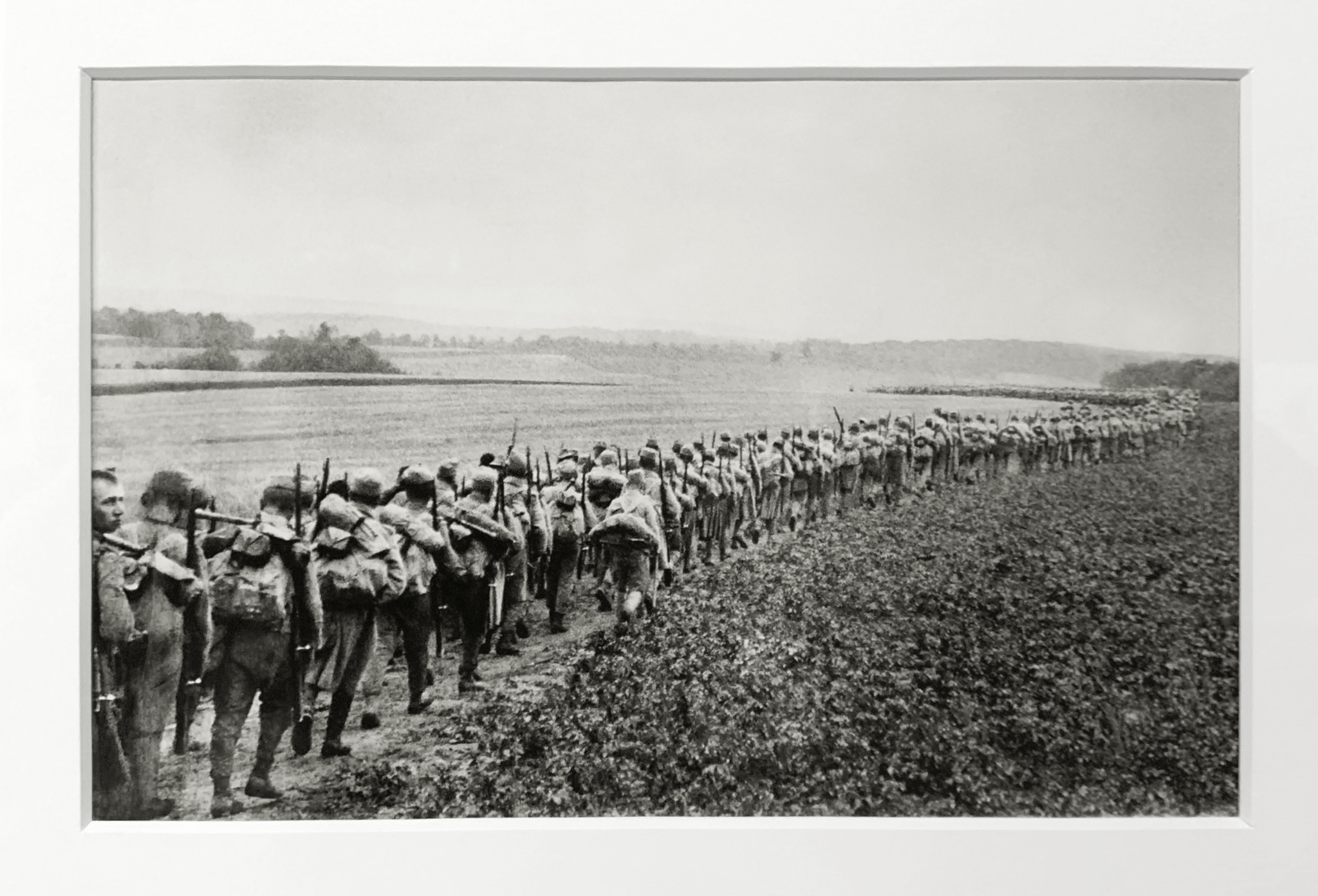

Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000)

Stairway to the Cathedral, Spain

1938

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 × 7 1/16 in. (24.1 × 17.9cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000)

Sin titulo (Milicianos en una trinchera/Militiamen in a trench)

1937-1938

Gelatin silver print

7 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (19 × 19cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, R. K. Mellon Family Foundation

Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000)

Kati Horna (May 19, 1912 – October 19, 2000), born Katalin Deutsch, was a Hungarian-born Mexican photojournalist, surrealist photographer and teacher. She was born in Budapest and lived in France, Berlin, Spain, and later was naturalised Mexican. Most of her work was lost during the Spanish Civil War. She was also one of the most influential women artists/photographers of her time. Through her photographs she was able to change the way that people viewed war. One way that Horna was able to do this was through the utilisation of a strategy called “gendered witnessing”. Gendered witnessing consisted of putting a more “feminine” view on the notion that war was a predominantly masculine thing. Horna became a legendary photographer after taking on a woman’s perspective of the war, she was able to focus on the behind the scenes, which led her to portraying the impact the war had on women and children. One of her most striking images is the Tête de poupée. Horna worked for various magazines including Mujeres and S.NOB, in which she published a series of Fétiches; but even her more commercial commissions often contained surreal touches. …

In 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, she moved to Barcelona, commissioned by the Spanish Republican government and the Confédération Générale du Travail, to document the war as well as record the everyday life of communities on the front lines, such as Aragón, Valencia, Madrid, and Lérida. She photographed elderly women, young children, babies and mothers, and was considered visionary for her choice of subject matter. She was editor of the magazine Umbral (where she me José Horna). Kati Horna collaborated with other magazines, most of which were anarchic, such as Tiempos Nuevos, Libre-Studio, Mujeres Libres and Tierra y Libertad. Her images of scenes from the civil war not only revealed her Republican sympathies but also gained her almost legendary status. Some of her photos were used as posters for the Republican cause.

Text from the Wikipedia website

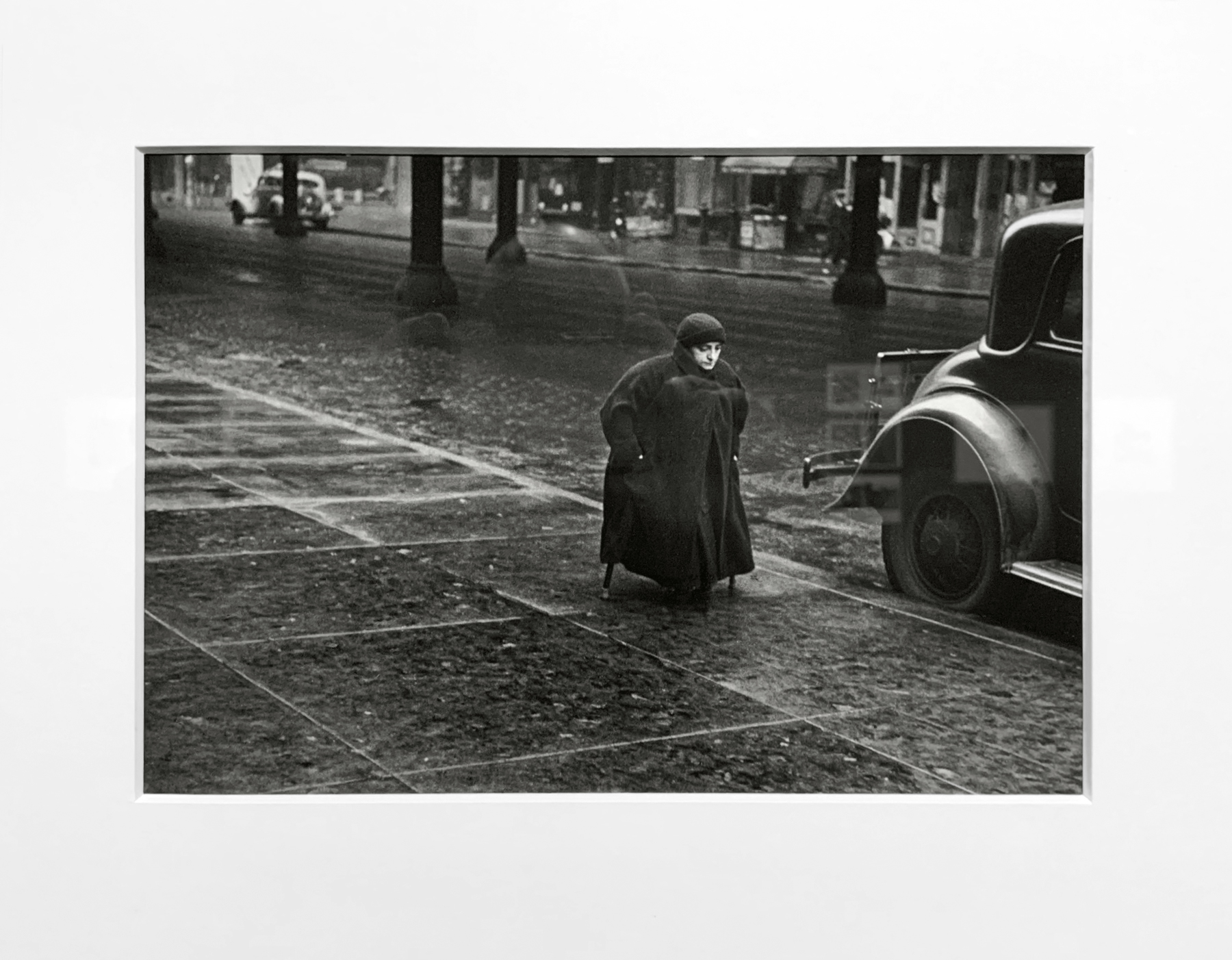

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Blind Man Walking, Paris

1933-1938

Gelatin silver print on newspaper mount

11 3/16 × 8 3/4 in. (28.4 × 22.3cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

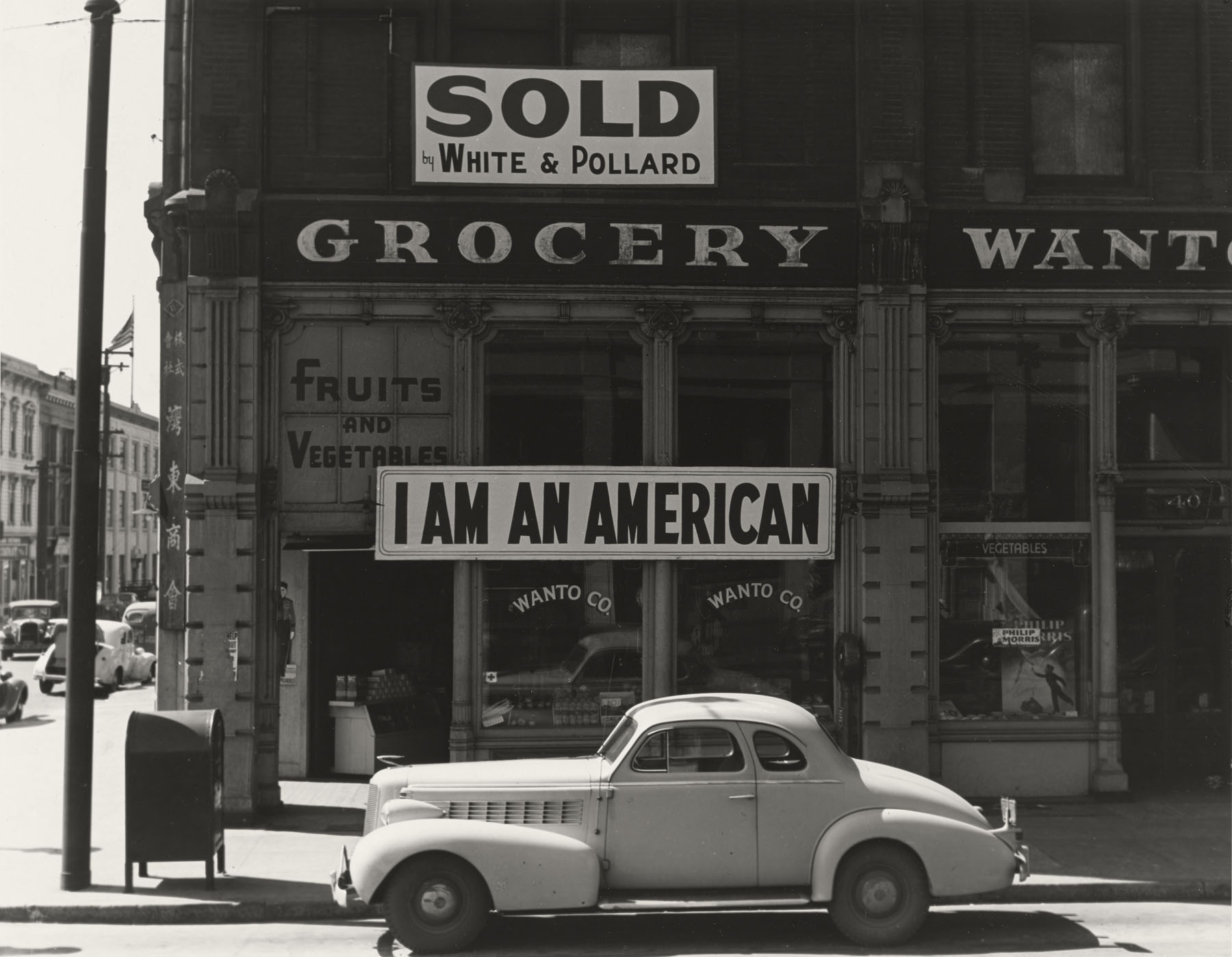

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Japanese-American owned grocery store in Oakland, California

March 1942

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Children of the Weill Public School shown in a flag pledge ceremony, San Francisco, California

April 1942, printed c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

9 1/4 × 6 7/8 in. (23.5 × 17.4cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Hansel Mieth (German, 1909-1998)

March of Dimes Dance

1943

Gelatin silver print

Collection of Ron Perisho

Homai Vyarawalla (Indian, 1913-2012)

The Victoria Terminus, Bombay

early 1940s, printed later

Inkjet print

11 9/16 × 11 13/16 in. (29.3 × 30cm)

Homai Vyarawalla Archive / The Alkazi Collection of Photography

Homai Vyarawalla (Indian, 1913-2012)

Homai Vyarawalla (9 December 1913 – 15 January 2012), commonly known by her pseudonym Dalda 13, was India’s first woman photojournalist. She began work in the late 1930s and retired in the early 1970s. In 2011, she was awarded Padma Vibhushan, the second highest civilian award of the Republic of India. She was amongst the first women in India to join a mainstream publication when she joined The Illustrated Weekly of India. …

Vyarawalla started her career in the 1930s. At the onset of World War II, she started working on assignments for Mumbai-based The Illustrated Weekly of India magazine which published many of her most admired black-and-white images. In the early years of her career, since Vyarawalla was unknown and a woman, her photographs were published under her husband’s name. Vyarawalla stated that because women were not taken seriously as journalists she was able to take high-quality, revealing photographs of her subjects without interference:

People were rather orthodox. They didn’t want the women folk to be moving around all over the place and when they saw me in a sari with the camera, hanging around, they thought it was a very strange sight. And in the beginning they thought I was just fooling around with the camera, just showing off or something and they didn’t take me seriously. But that was to my advantage because I could go to the sensitive areas also to take pictures and nobody will stop me. So I was able to take the best of pictures and get them published. It was only when the pictures got published that people realised how seriously I was working for the place.

~ Homai Vyarawalla in Dalda 13: A Portrait of Homai Vyarawalla (1995)

Eventually her photography received notice at the national level, particularly after moving to Delhi in 1942 to join the British Information Services. As a press photographer, she recorded many political and national leaders in the period leading up to independence, including Mohandas Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Indira Gandhi and the Nehru-Gandhi family.

The Dalai Lama in ceremonial dress enters India through Nathu La in Sikkim on 24 November 1956, photographed by Homai Vyarawalla. In 1956, she photographed for Life Magazine the 14th Dalai Lama when he entered Sikkim in India for the first time via the Nathu La.

Most of her photographs were published under the pseudonym “Dalda 13”. The reasons behind her choice of this name were that her birth year was 1913, she met her husband at the age of 13 and her first car’s number plate read “DLD 13”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

Buchenwald Prison

13th April 1945

Gelatin silver print

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

The Liberation of Buchenwald

April 1945

Gelatin silver print

Caption from LIFE. “Deformed by malnutrition, a Buchenwald prisoner leans against his bunk after trying to walk. Like other imprisoned slave labourers, he worked in a Nazi factory until too feeble.”

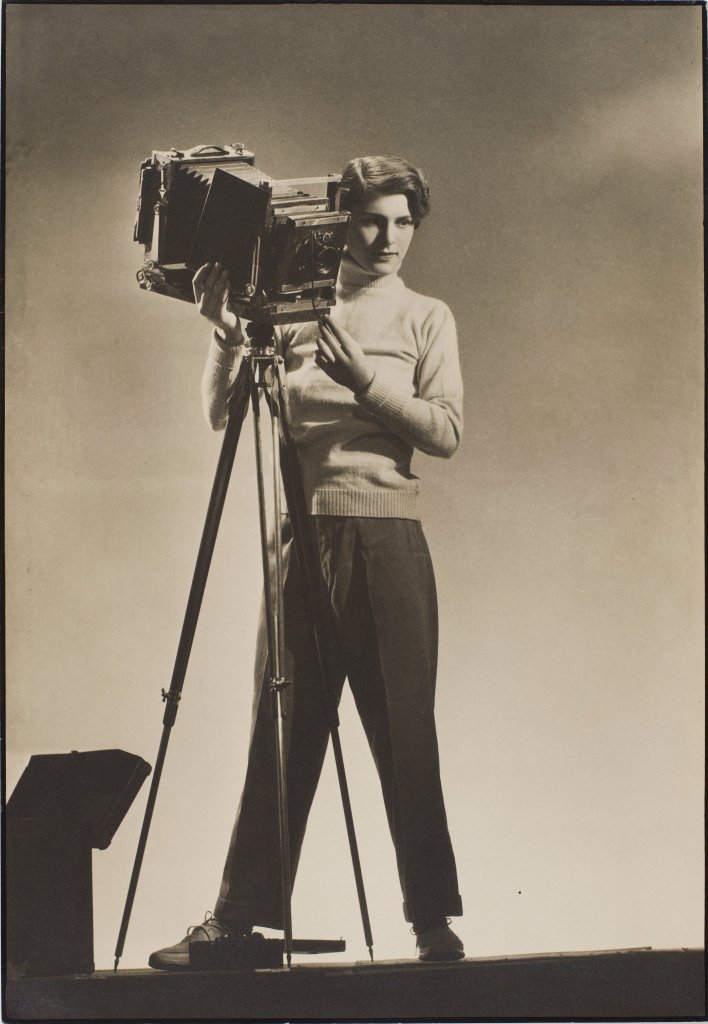

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

Self-Portrait with Camera

c. 1933

Gelatin-silver print, toned

13 1/4 × 9 1/8 in. (33.66 × 23.18cm)

Lee Miller (American, 1907-1977)

Dead SS Prison Guard Floating in Canal, Dachau, Germany

1945

Gelatin silver print

6 1/4 in. × 6 in. (15.9 × 15.2cm)

Lee Miller Archives

© Lee Miller Archives, England 2021

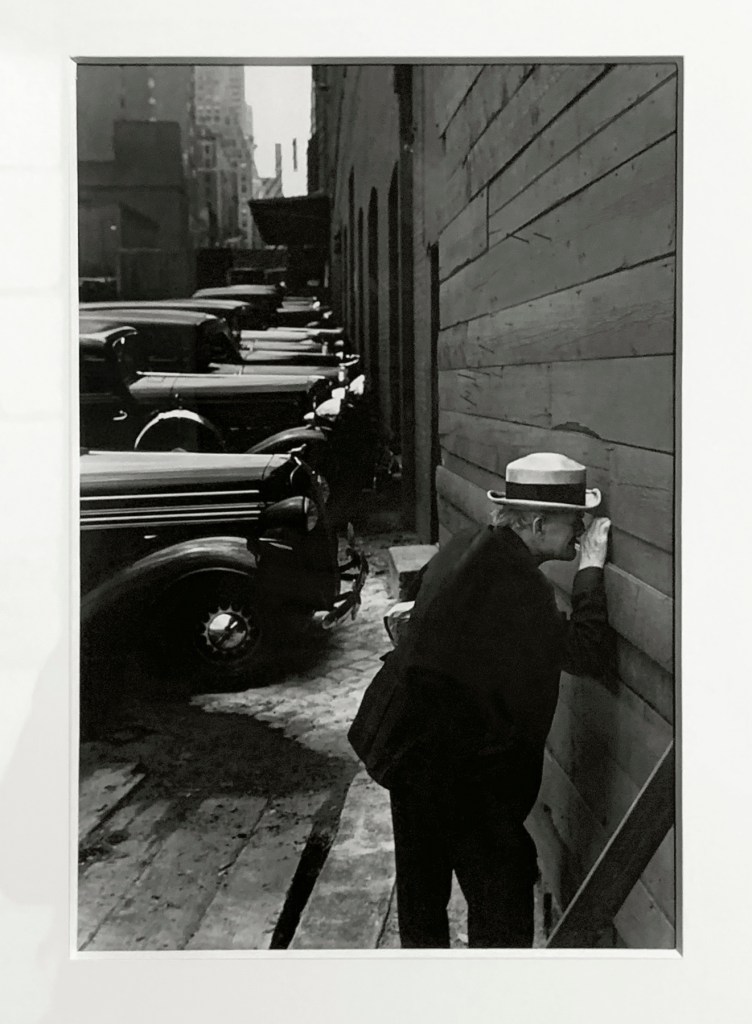

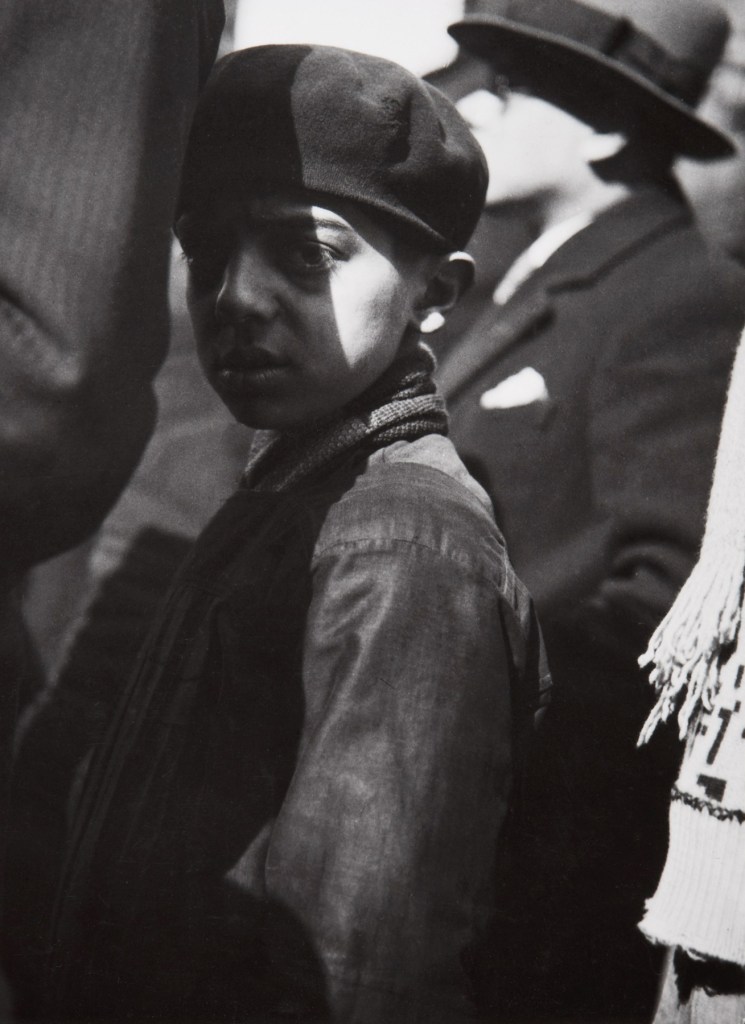

Sometime in the 1930s, Hungarian photographer Anna Barna shot “Onlooker,” a picture of a boy standing on a chair seen from behind as he peers over a palisade.

As his shadow stretches out across the planks blocking his way, it takes the shape of a bearded profile that reads as a second “onlooker” in the shot. A bit further off stands yet a third “looker” who, though quite invisible in the image, was very much present in the mind of any prewar viewer who saw the shot’s photo credit: That looker is Anna Barna, a woman who has dared to pick up the camera that would normally have been held by a man. Like all the camera-wielding women of her era, Barna made a bold move that gave her a powerful cultural presence.

That presence is on display in “The New Woman Behind the Camera,” an inspired and inspiring exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through Oct. 3. In late October, it moves on to the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Curated by Andrea Nelson of the NGA, the show has been installed at the Met by Mia Fineman.

The more than 200 pictures on view, taken from the 1920s through the ’50s, let us watch as women everywhere become photo pros. I guess some of their shots could have been snapped by men, but female authorship shaped what these images meant to their contemporaries. It shapes what we need to make of them now, as we grasp the challenges their makers faced.

The Met shows women photographing everything from factories to battles to the oppressed, but also gowns and children and other traditionally “feminine” subjects. Sometimes the goal is straight documentation: Figures like Dorothea Lange in the United States and Galina Sanko in the Soviet Union recorded the worlds they moved through, often at the request of their governments. But many of their sisters prefer the aggressive viewpoints and radical lightings of what was then called the New Vision, as developed at the Bauhaus and other hot spots of modern style. It was to sight what jazz was to sound.

That made the New Vision a perfect fit for the New Woman, a term that went global early in the 20th century to describe all the many women who took on roles and responsibilities – new personas and even new powers – they’d rarely had before. When a New Woman took up photography, she often turned her New Vision on herself, as one of the modern world’s most striking creations.

A self-portrait by American photographer Alma Lavenson leaves out everything but her hands and the camera they’re holding; the only thing we need to know is that Lavenson is in control of this machine, and therefore of the vision it captures.

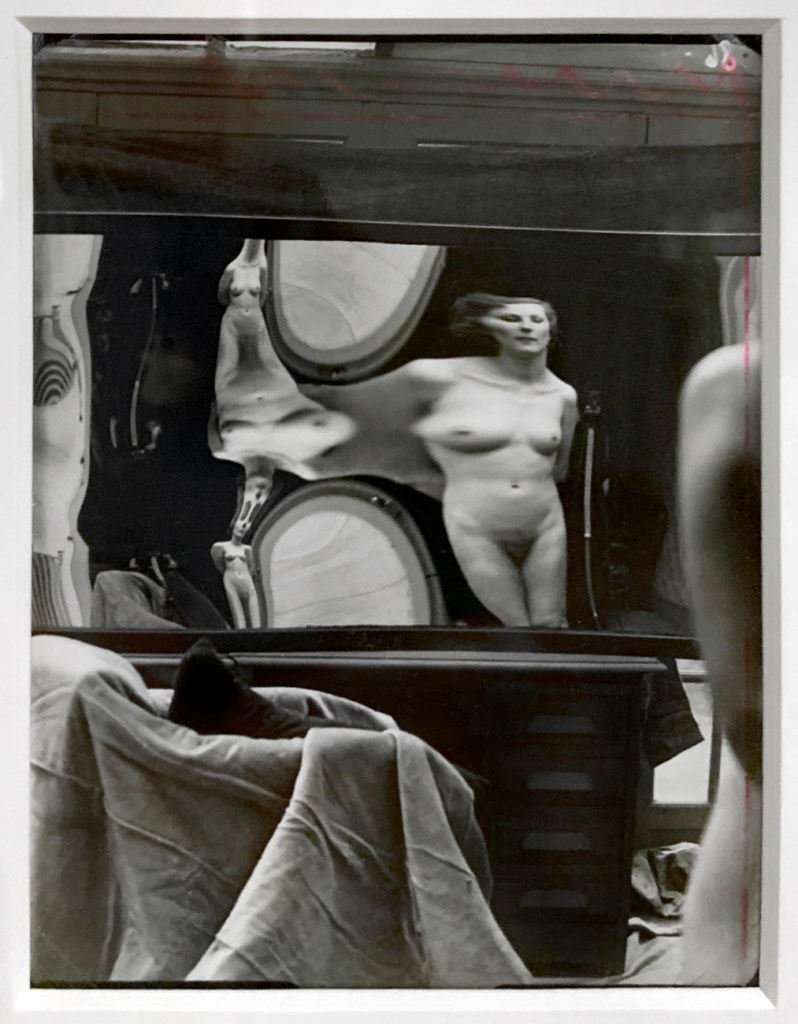

German photographer Ilse Bing shoots into the hinged mirrors on a vanity, giving us both profile and head-on views of her face and of the Leica that almost hides it. Since antiquity, the mirror had been a symbol of woman and her vanities; Bing claims that old symbol for herself, making it yield a new image.

The mirror deployed by the German Argentine photographer Annemarie Heinrich is a silvered sphere; capturing herself and her sister in it, she depicts the fun-house pleasures, and distortions, of being a woman made New.

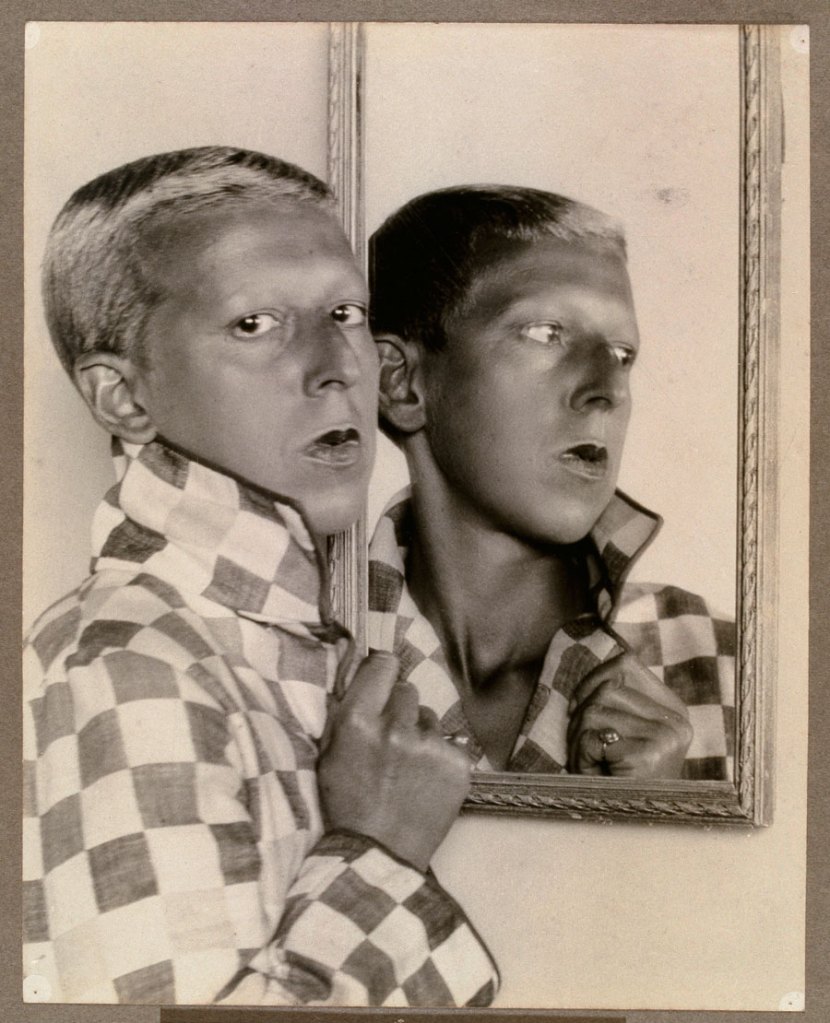

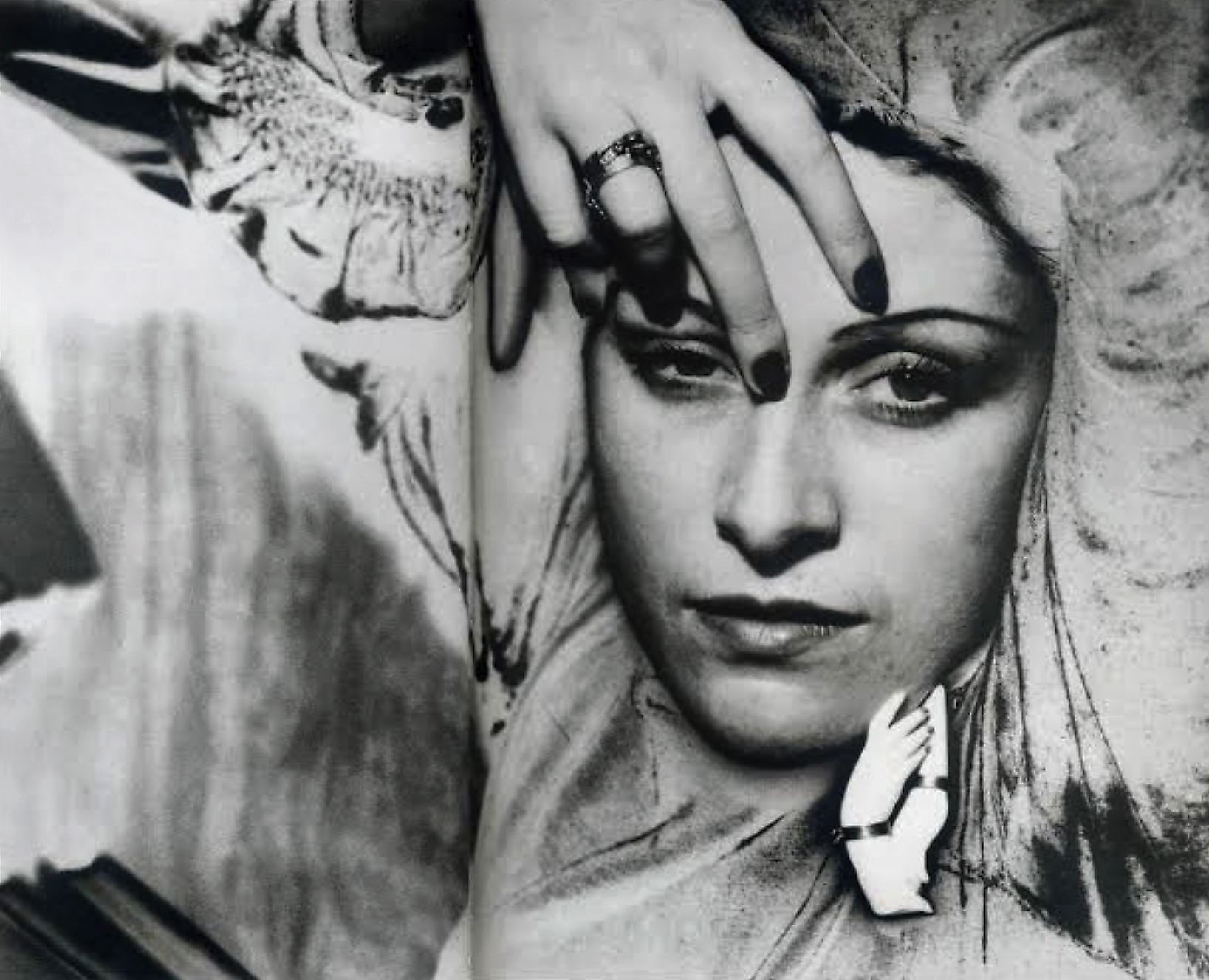

Heinrich’s European peers sometimes go further in disturbing their self-presentation. In “Masked Self-Portrait (No. 16),” Gertrud Arndt double- or maybe triple-exposes her face, as though to convey the troubled identity she’s taken on as a woman who dares to photograph. (Multiple exposure is almost a hallmark of New Woman photographers; maybe that shouldn’t surprise us.) In a collage titled “I.O.U. (Self-Pride),” French photographer Claude Cahun presents herself as 11 different masked faces, surrounded by the words “Under this mask, another mask. I’ll never be done lifting off all these faces.”

It’s as though the act of getting behind a camera turns any New Woman into an ancestor and avatar of Cindy Sherman, trying on all sorts of models for gender.

If there’s one problem with this show, it’s that it mostly gives us women who succeeded in achieving the highest levels of excellence, barely hinting at the much greater number of women who were prevented from reaching their creative goals by the rampant sexism of their era: talented women whose places in a photo school were given to men instead, or who were streamed into the lowest or most “feminine” tiers of the profession – retouching, or cheap kiddie portraits – or who were never promoted above studio assistant.

It’s a problem that bedevils all attempts at recovering the lost art of the disadvantaged: By telling the same stories of success that you do with white males, you risk making it look as though others were given the same chance to rise.

A quite straight shot of Chinese photojournalist Niu Weiyu may best capture what it really meant for the New Woman to start taking pictures. As snapped by her colleague Shu Ye, Niu stands perched with her camera at the edge of a cliff. Every female photographer adopted this daredevil pose, at least in cultural terms, just by clicking a shutter.

Several of the women featured at the Met actually took over studios originally headed by husbands or fathers. In the Middle East and Asia, this gave them access to a reality that men could not document: Taken in 1930s Palestine, a photo by an entrepreneur who styled herself as “Karimeh Abbud, Lady Photographer” shows three women standing before the camera with complete self-confidence – the youngest smiles broadly into the lens – in a relaxed shot that a man would have been unlikely to capture.

Gender was almost as powerfully in play for women in the West. If taking up a camera was billed as “mannish,” many a New Woman in Europe was happy to go with that billing: Again and again, they portray themselves coiffed with the shortest of bobs, sometimes so short they read as male styles. Cahun, who at times was almost buzz-cut, once wrote “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”

Margaret Bourke-White, an American photographer who achieved true celebrity, shoots herself in a bob long enough to just about cover her ears, but this almost girlish style is more than offset by manly wool slacks. (In the 1850s, Rosa Bonheur had to get a police license to wear pants when she went to draw the horse-breakers of Paris. As late as 1972, my grandmother, born into the age of the New Woman, boasted of the courage she’d recently mustered to start wearing pants to work.)

A New Woman clicking the shutter might seem almost as much on display as any subject before her lens. Bourke-White’s photo of the Fort Peck dam graced the cover of Life magazine’s first modern issue, in 1936, and it got that play in part because it had been shot by her: The editors go on about that “surprising” fact as they introduce their new magazine, and how they were “unable to prevent Bourke-White from running away with their first nine pages.”

When a subject is in fact another woman, shooter and sitter can collapse into one. Lola Álvarez Bravo, the great Mexican photographer, once took a picture of a woman with shadows crisscrossing her face, titling it “In Her Own Prison.” As a photographic Everywoman, Álvarez Bravo comes off as in that same jail.

To capture the predicament of women in Catholic Spain, Kati Horna double-exposed a girl’s face onto the barred windows beside a cathedral; it’s hard not to see the huge eye that looks out at us from behind those bars as belonging to Horna herself, peering through the viewfinder.

For centuries before they went New, women had been objectified and observed as few men were likely to be. Picking up the camera didn’t pull eyes away from a New Woman; it could put her all the more clearly on view. But thanks to photography, she could begin to look back, with power, at the world around her.

Blake Gopnik. “Women Who Shaped Modern Photography,” on The New York Times website July 11, 2021 [Online] Cited 16/07/2021

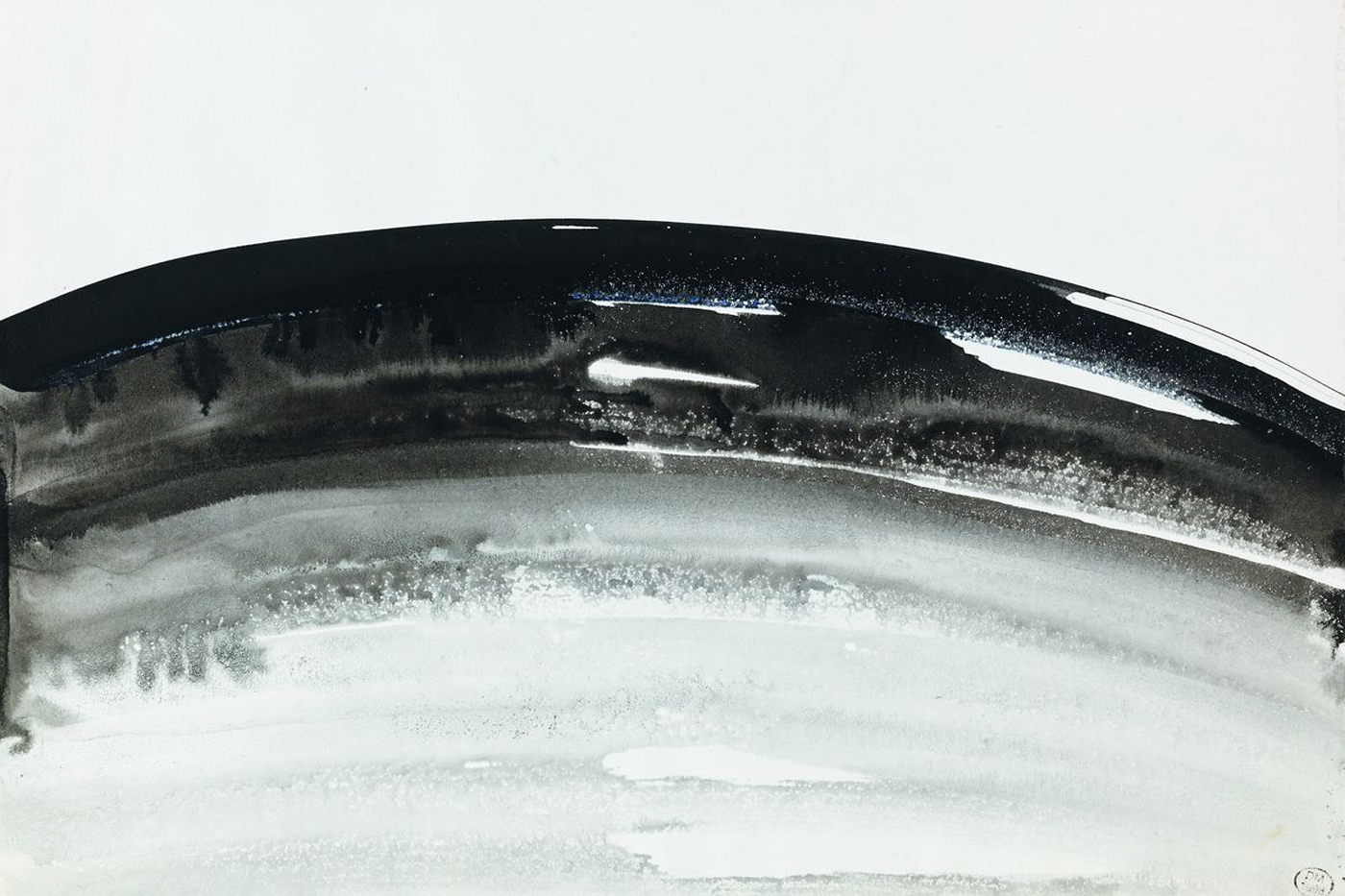

Bernice Kolko (American born Poland, 1905-1970)

Photogram

c. 1944

Gelatin silver print

9 3/4 × 11 1/2 in. (24.8 × 29.2cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

Bernice Kolko (American born Poland, 1905-1970)

Bernice Kolko (1905-1970) was a Polish-American photographer. During World War II, she joined the Women’s Army Corps as a photographer. In 1953 she became friends with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, who she had met when they visited Chicago. They invited her to Mexico, where she travelled, taking pictures of the women of Mexico. She and Kahlo travelled frequently, with Kolko taking photos of Kahlo in the two years before Kahlo’s death. In 1955 she became the first woman to exhibit at the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

Text from the Wikipedia website

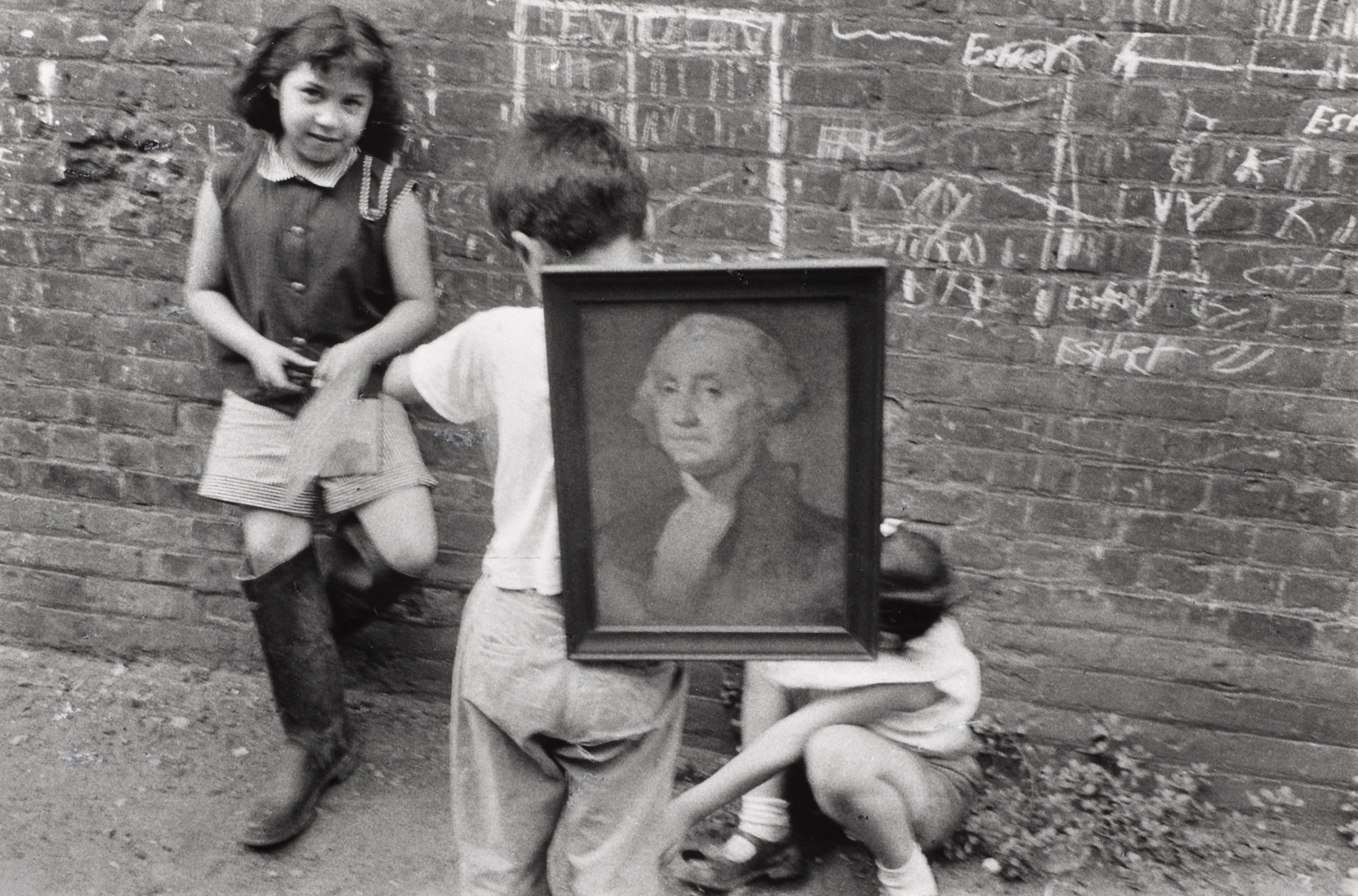

Rebecca Lepkoff (American, 1916–2014)

14th Street, New York City

1947-48

Gelatin silver print

10 5/8 × 12 9/16 in. (27 × 31.9cm)

Purchase, Phillip and Edith Leonian Foundation Gift, 2012

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rebecca Lepkoff (American, 1916-2014)

Rebecca Lepkoff (born Rebecca Brody; 1916-2014) was an American photographer. She is best known for her images depicting daily life in the Lower East Side neighbourhood of New York City in the 1940s. …

Fascinated by the area where she lived, she first photographed Essex and Hester Street which, she recalls, “were full of pushcarts.” They no longer exist today but then “everyone was outside: the mothers with their baby carriages, and the men just hanging out.” Her photographs captured people in the streets, especially children, as well as the buildings and the signs on store fronts.

In 1950, she also photographed people at work and play in Vermont. The images were used to illustrate the book Almost Utopia: The Residents and Radicals of Pikes Falls, Vermont, 1950, published by the Vermont Historical Society. They present the area before its character was changed with paved roads and vacationers. In the 1970s, she photographed the next generation of inhabitants in a series she called Vermont Hippies.

Rebecca Lepkoff was an active member of the Photo League from 1947 until 1951 when it was dissolved as a “communist organisation” in the McCarthy era.

Text from the Wikipedia website

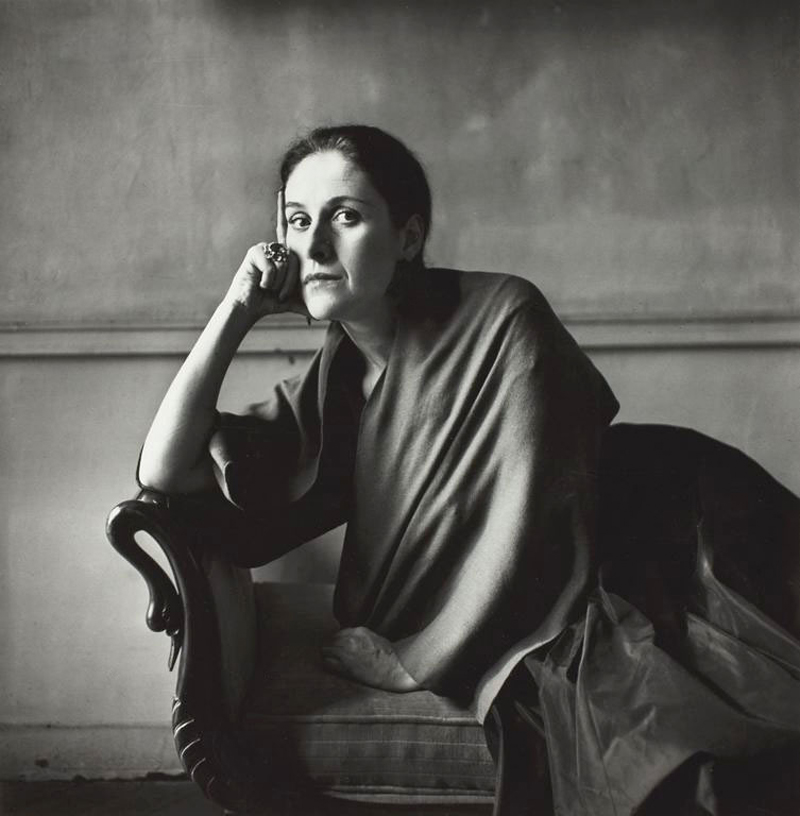

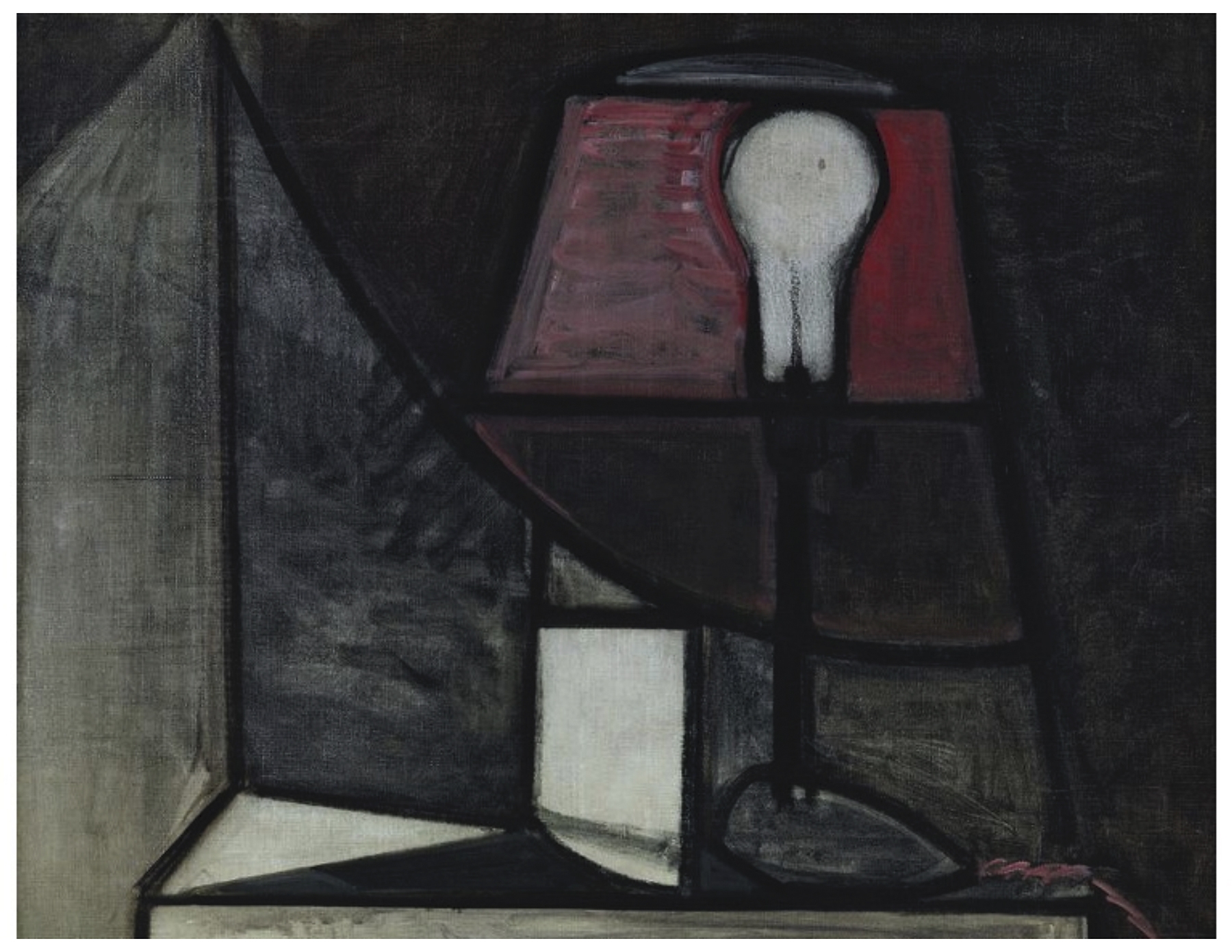

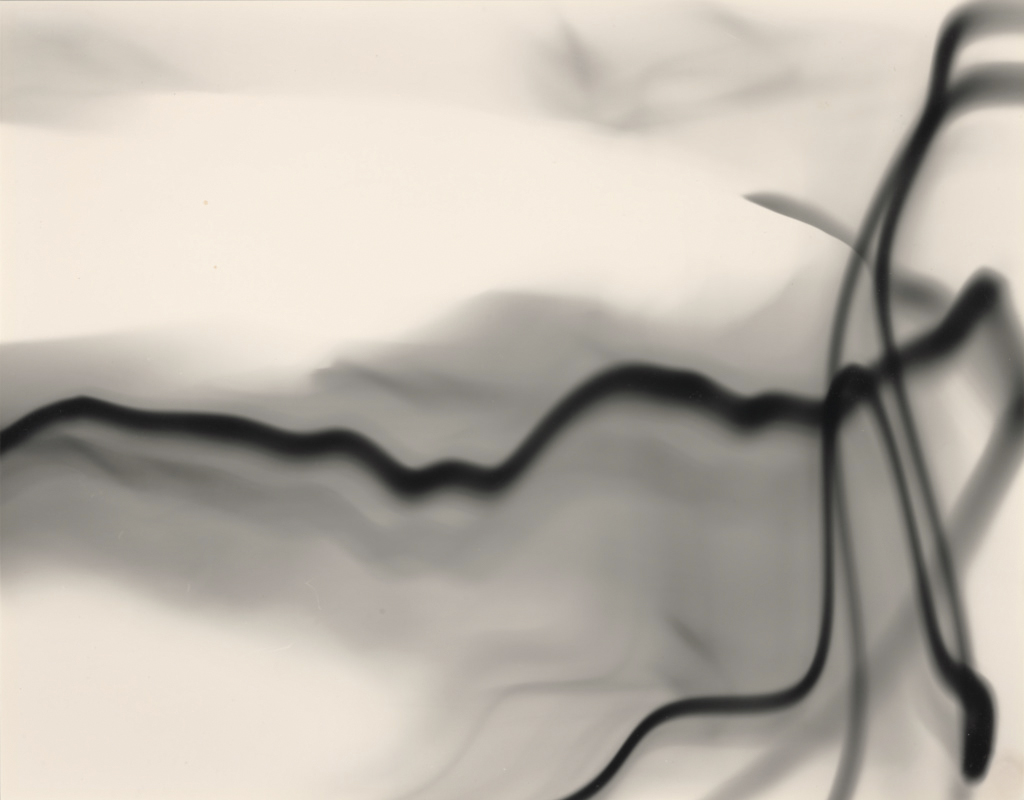

Grete Stern (Argentinian born Germany, 1904-1999)

Sueño No. 1: “Articulos eléctricos para el hogar” (Dream No. 1: “Electrical Household items”)

1949

Gelatin silver print

18 1/4 × 15 11/16 in. (46.4 × 39.8cm)

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2012

Metropolitan Museum of Art

In 1948 the Argentine women’s magazine Idilio introduced a weekly column called “Psychoanalysis Will Help You,” which invited readers to submit their dreams for analysis. Each week, one dream was illustrated with a photomontage by Stern, a Bauhaus-trained photographer and graphic designer who fled Berlin for Buenos Aires when the Nazis came to power. Over three years, Stern created 140 photomontages for the magazine, translating the unconscious fears and desires of its predominantly female readership into clever, compelling images. Here, a masculine hand swoops in to “turn on” a lamp whose base is a tiny, elegantly dressed woman. Rarely has female objectification been so erotically and electrically charged.

Alice Brill (Brazilian born Cologne, 1920-2013)

Street Vendor at the Chá Viaduct, São Paulo

c. 1953

Gelatin silver print

32 × 32cm (12 5/8 × 12 5/8 in.)

Instituto Moreira Salles

Alice Brill (Brazilian born Germany, 1920-2013)

Alice Brill (December 13, 1920 – June 29, 2013) was a German-born Brazilian photographer, painter, and art critic.

Alice Brill Czapski was born in Cologne, Germany, in 1920. She was Jewish, the daughter of the painter Erich Brill [de] and the journalist Martha Brill [de]. In 1934 she and her parents left Germany to escape the National Socialist (Nazi) regime; her mother, long divorced from Erich Brill, emigrated to Brazil, and in 1935 Alice Brill and her father also emigrated there. Influenced by a schoolteacher, she recorded in a diary the trips made during exile, with a photographic camera given to her by her father. She passed through Spain, Italy and the Netherlands before landing in Brazil. Her father returned alone to Germany in 1936. He was subsequently imprisoned and died, a Holocaust victim, in 1942 at the Jungfernhof concentration camp.

At age 16 she studied with the painter Paulo Rossi Osir, who influenced her production of photographs and batik paintings. She participated in the Santa Helena Group, an informal association of painters from São Paulo, maintaining contact with artists such as Mario Zanini and Alfredo Volpi. In 1946, she won a Hillel Foundation scholarship to study at the University of New Mexico and the Art Students League of New York where she studied photography, painting, sculpture, engraving, art history, philosophy and literature.

After returning to Brazil in 1948, she worked as a photographer for Habitat magazine, coordinated by architect Lina Bo Bardi. She documented architecture, fine arts and made portraits of artists, as well as recording works and exhibitions of the São Paulo Art Museum and Sao Paulo Museum of Modern Art He also participated in an expedition in Corumbá organised by the Central Brazil Foundation, photographing the Carajás people. In 1950, she performed the essay at the Psychiatric Hospital of Juqueri at the invitation of the plastic artist Maria Leontina da Costa, registering the wing of the Free Art Workshop. In the same year, Pietro Maria Bardi commissioned an essay on São Paulo for the city’s fourth centennial. It portrayed the process of modernisation of the city between 1953 and 1954, but the publication project was not completed.

In addition to being a photographer, she worked as a painter, participating in the I and IX Bienal de São Paulo (1951 and 1967 respectively), as well as several individual and collective exhibitions. Her subjects involved urban landscapes and abstractionism, performing watercolours and batik paintings. She graduated in philosophy from PUC-SP in 1976, graduating in 1982 and a doctorate in 1994 and worked as an art critic, writing articles for the culture section of the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo, which were later collected in the book “Da arte e da linguagem” (Perspectiva, 1988).

Text from the Wikipedia website

Frieda Gertrud Riess (German, 1890-1957)

The Sculptor Renée Sintenis

1925, printed 1925-1935

Gelatin silver print

8 7/8 × 6 13/16 in. (22.6 × 17.3 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Bequest of Gertrude Palmer, by exchange

Frieda Gertrud Riess (German, 1890-1957)

Frieda Gertrud Riess (1890 – c. 1955) was a German portrait photographer in the 1920s with a studio in central Berlin.

In 1918, she opened a business on the Kurfürstendamm in Berlin; it became one of the most popular studios in the city. Partly as a result of her marriage to the journalist Rudolf Leonhard in the early 1920s, she extended her clientele to celebrities such as playwright Walter Hasenclever, novelist Gerhart Hauptmann and actors and actresses including Tilla Durieux, Asta Nielsen and Emil Jannings. This group extended to include dancers, music-hall stars and fine artists: Anna Pavlova, Mistinguett, Lil Dagover, Renée Sintenis, Max Liebermann and Xenia Boguslawskaja. Other clients included representatives of the old aristocracy, diplomats, politicians and bankers. Boxers (and nudes thereof) were a notable group in which she specialised, including Erich Brandl, Hermann Herse, Max Schmeling, Ensor Fiermonte.

Such was her renown that she became known simply as Die Reiss. While on a trip to Italy in 1929, she was invited to photograph Benito Mussolini. In addition, she contributed to the journals and magazines of the day including Die Dame, Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, Der Weltspiegel, Querschnit and Koralle. In 1932, after falling in love with Pierre de Margerie, the French ambassador in Berlin (1922-1931). She moved to Paris with him, and he died in 1942. She disappeared from the public eye during the Occupation. Even the date of her death cannot be clearly established and her place of burial remains unknown.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Renée Sintenis (German, 1888-1965)

Renée Sintenis, née Renate Alice Sintenis (March 20, 1888, Glatz – April 22, 1965, West Berlin), was a German sculptor, medalist and graphic artist who worked in Berlin. She created mainly small-sized animal sculptures, female nudes, portraits (drawings and sculptures) and sports statuettes. …

In 1928 Sintenis won the bronze medal in the sculpture section of the art competition for the Summer Olympics in Amsterdam; she is thought to be the first LGBTQ+ Olympic medallist. Renée Sintenis took part in the 1929 exhibition of the German Association of Artists in the Cologne State House, with five small-format animal sculptures. In 1930 she met the French sculptor Aristide Maillol in Berlin. In 1931 she was appointed as the first sculptor, and second woman after Käthe Kollwitz, together with 13 other artists, to join the Berlin Academy of the Arts – Fine Arts section, although the National Socialists forced her to leave in 1934.

Due to her body size, slim figure, charisma, her self-confident, fashionable demeanor and androgynous beauty, she was often portrayed by artists like her husband, Emil Rudolf Weiß and Georg Kolbe, and by photographers, like Hugo Erfurth, Fritz Eschen and Frieda Riess. She embodied perfectly the type of the ‘new woman’ of the 1920s, even if she appeared rather reserved.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Renée Sintenis’ work was included in the Schwules Museum’s exhibition LESBIAN VISIONS – Artistic positions from Berlin, May – August 2018.

The exhibition conceptualised a utopian and melancholic gallery that follows the tracks of lesbian forms of pleasure and experience as well as lesbian identity constructions and lifestyles. In this context, the exhibition understood and recognised the term “lesbian” in its broadest sense, which is to say that desire and gender can be fluid.

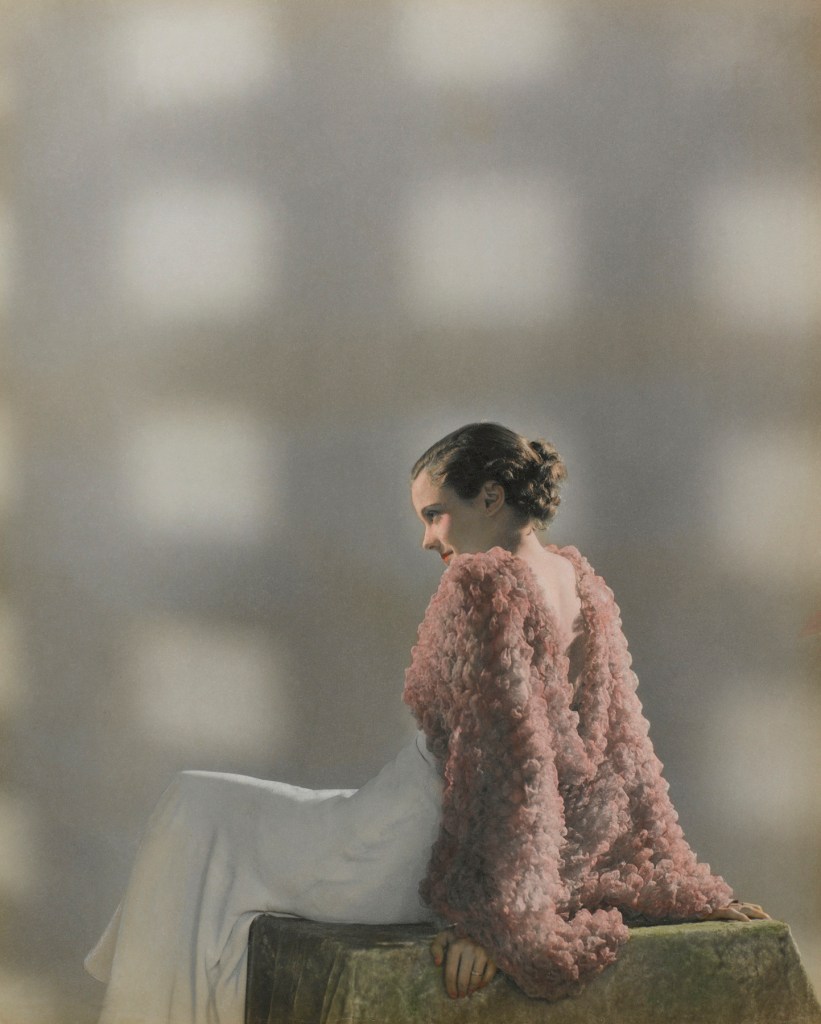

Yevonde Cumbers Middleton (British, 1893–1975)

Lady Bridget Poulett as ‘Arethusa’

1935

Vivex colour print

14 3/4 × 10 3/4 in. (37.5 × 27.3cm)

National Portrait Gallery, London, Given by Madame Yevonde, 1971

Yevonde Philone Middleton (English, 1893-1975)

Yevonde Philone Middleton (English, 1893-1975) was an English photographer, who pioneered the use of colour in portrait photography. She used the professional name Madame Yevonde. …

Cumbers sought, and was given, a three-year apprenticeship with the portrait photographer Lallie Charles. With the technical grounding she received from working with Charles, and a gift of £250 from her father, at the age of 21 Yevonde set up her own studio at 92 Victoria Street, London, and began to make a name for herself by inviting well-known figures to sit for free. Before long her pictures were appearing in society magazines such as the Tatler and The Sketch. Her style quickly moved away from the stiff “pouter pigeon” look of Lallie Charles, toward a still formal, but more creative, style. Her subjects were often pictured looking away from the camera, and she began using props to creative effect.

By 1921 Madame Yevonde had become a well-known and respected portrait photographer, and moved to larger premises at 100 Victoria Street. Here she began taking advertising commissions and also photographed many of the leading personalities of the day, including A.A. Milne, Barbara Cartland, Diana Mitford, Louis Mountbatten and Noël Coward.

In the early 1930s, Yevonde began experimenting with colour photography, using the new Vivex colour process from Colour Photography Limited of Willesden. The introduction of colour photography was not universally popular; indeed photographers and the public alike were so used to black-and-white pictures that early reactions to the new process tended toward the hostile. Yevonde, however, was hugely enthusiastic about it and spent countless hours in her studio experimenting with how to get the best results. Her dedication paid huge dividends. In 1932 she put on an exhibition of portrait work at the Albany Gallery, half monochrome and half colour, to enthusiastic reviews.

In 1933, Madame Yevonde moved once again, this time to 28 Berkeley Square. She began using colour in her advertising work as well as her portraits, and took on other commissions too. In 1936, she was commissioned by Fortune magazine to photograph the last stages in the fitting out of the new Cunard liner, the Queen Mary. This was very different from Yevonde’s usual work, but the shoot was a success. People printed twelve plates, and pictures were exhibited in London and New York City. One of the portraits was of artist Doris Zinkeisen who was commissioned together with her sister Anna to paint several murals for the Queen Mary. Another major coup was being invited to take portraits of leading peers to mark the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. She joined the Royal Photographic Society in 1933, and became a Fellow in 1940. The RPS Collection holds examples of her work.

Yevonde’s most famous work was inspired by a theme party held on 5 March 1935, where guests dressed as Roman and Greek gods and goddesses. Yevonde subsequently took studio portraits of many of the participants (and others), in appropriate costume and surrounded by appropriate objects. This series of prints showed Yevonde at her most creative, using colour, costume and props to build an otherworldly air around her subjects. She went on to produce further series based on the signs of the zodiac and the months of the year. Partly influenced by surrealist artists, particularly Man Ray, Yevonde used surprising juxtapositions of objects which displayed her sense of humour.

This highly creative period of Yevonde’s career would only last a few years. At the end of 1939, Colour Photographs Ltd closed, and the Vivex process was no more. It was the second major blow to Yevonde that year – her husband, the playwright Edgar Middleton, had died in April. Yevonde returned to working in black and white, and produced many notable portraits. She continued working up until her death, just two weeks short of her 83rd birthday, but is chiefly remembered for her work of the 1930s, which did much to make colour photography respectable.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Lady Bridget Elizabeth Felicia Henrietta Augusta Poulett (English, 1912-1975), was an English socialite, sometime model of Cecil Beaton.

![Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942) 'La técnica [or, Mella's Typewriter]' 1928 Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942) 'La técnica [or, Mella's Typewriter]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/tina-modotti-la-technica.jpg?w=821)

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

La técnica [or, Mella’s Typewriter]

1928

Gelatin silver print

24 × 19.2cm (9 7/16 × 7 9/16 in.)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Anonymous gift

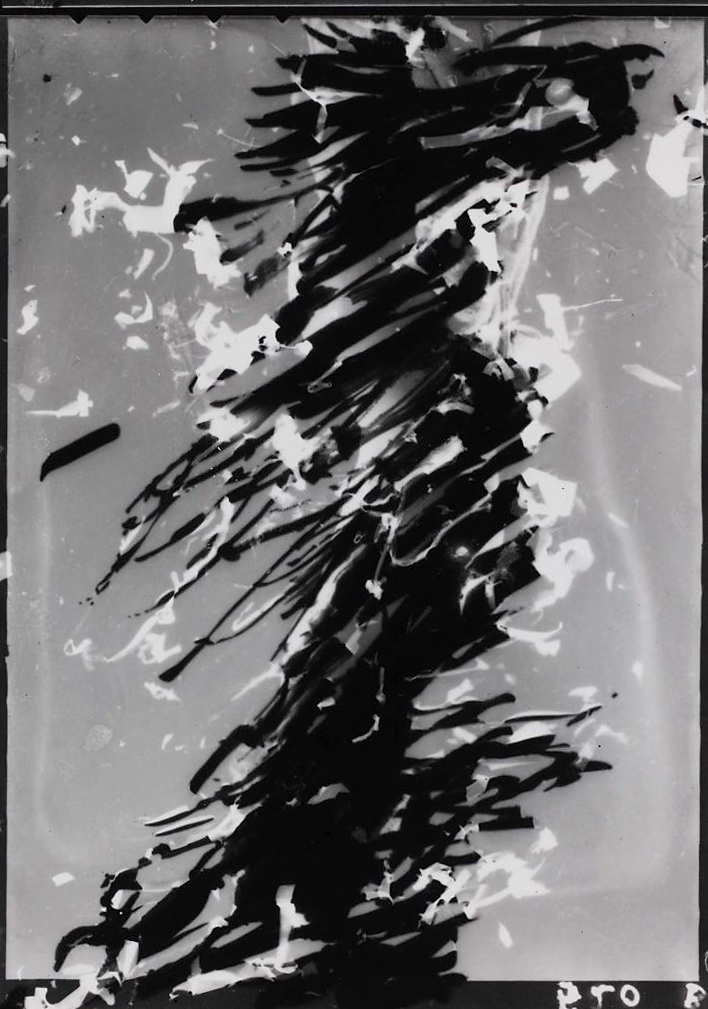

Irene Bayer-Hecht (American, 1898-1991)

Female Student with Beach Ball

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

4 1/8 × 3 1/16 in. (10.5 × 7.8cm)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Irene Bayer-Hecht (1898-1991) was an American born photographer involved in the Bauhaus movement. Her photographs “feature experimental approaches and candid views of life at the Bauhaus.”

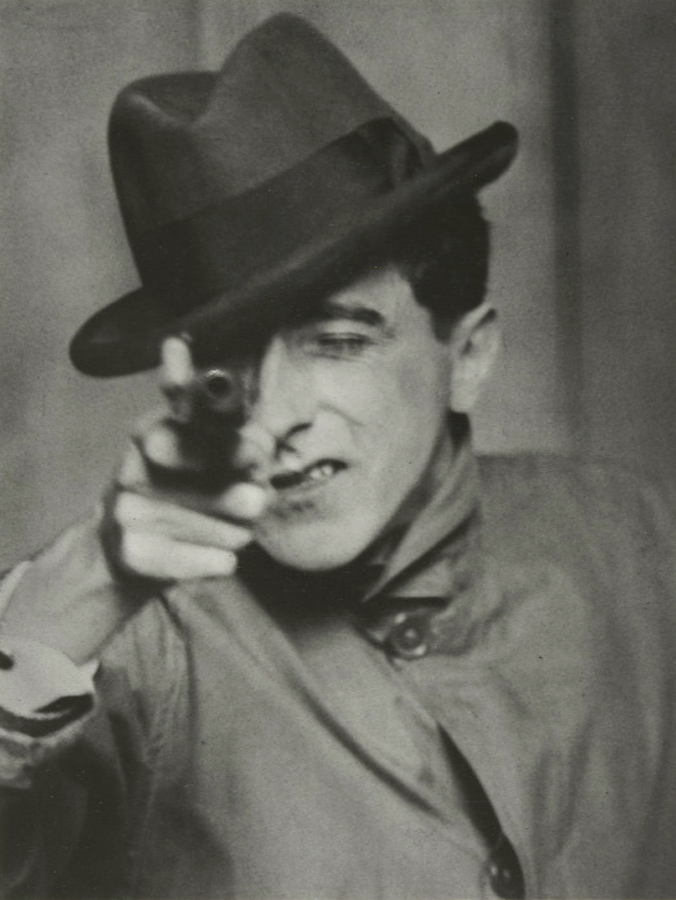

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

Jean Cocteau with Gun, Paris

c. 1926

From Faces of the 20’s

Gelatin silver print

34 x 25.5cm (13.4 x 10 in.)

Berenice Abbott in an undated photo. Photographer and source unknown 1930s

Public domain

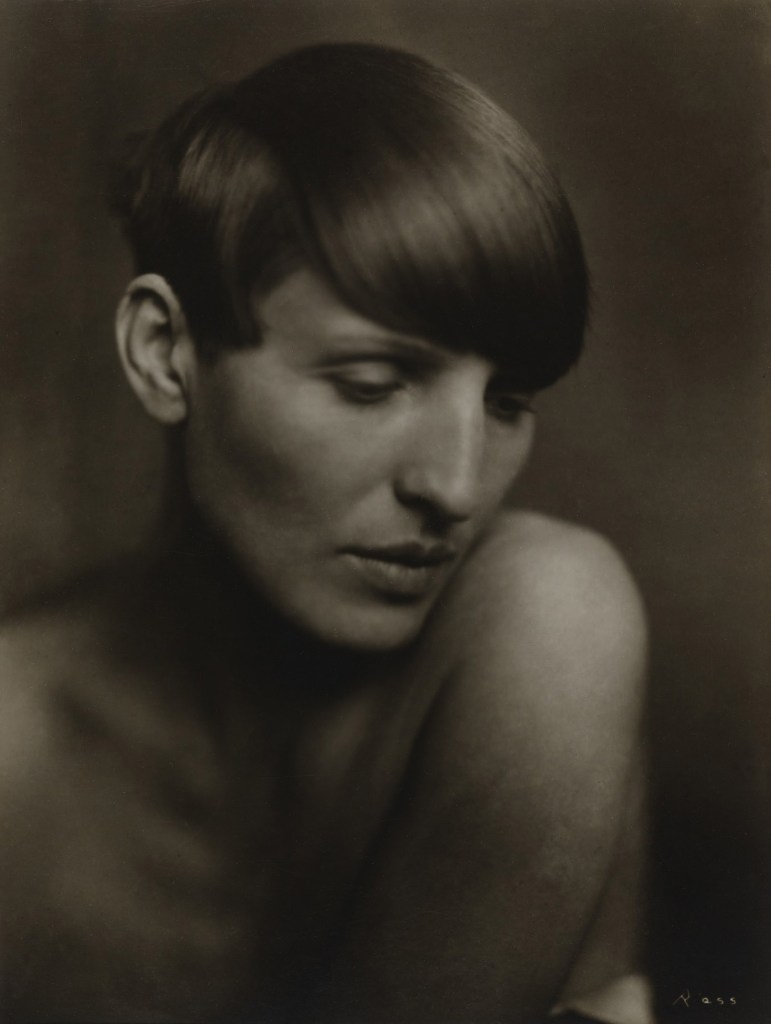

Annelise Kretschmer (German, 1903–1987)

Young Woman

1928

Gelatin silver print

18 3/8 × 15 11/16 in. (46.7 × 39.8cm)

Museum Folkwang, Essen

© Museum Folkwang Essen – ARTOTHEK

Annelise Kretschmer (1903-1987) was a German portrait photographer. Kretschmer is best known for her depictions of women in Germany in the early 20th century and is credited with helping construct the ‘Neue Frau’ or New Woman image of modern femininity.

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

I.O.U. (Self-Pride) in Aveux non avenus

1930

Book

Open: 8 3/4 × 12 1/2 in. (22.2 × 31.8cm)

Closed: 8 3/4 × 6 3/4 in. (22.2 × 17.2cm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC,

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait (reflected image in mirror with chequered jacket)

1927

Silver gelatin print

Ruth Harriet Louise (American, 1906-1944)

Carmel Myers

1925-1930

Gelatin silver print

12 7/16 × 9 1/4 in. (31.6 × 23.5cm)

The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Ruth Harriet Louise (American, 1906-1944)

Ruth Harriet Louise (born Ruth Goldstein, January 13, 1903 – October 12, 1940) was an American photographer. She was the first woman photographer active in Hollywood, and she ran Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s portrait studio from 1925 to 1930.

Ruth Harriet Louise was born Ruth Goldstein in New York City and raised in New Brunswick, New Jersey. She was the daughter of Klara Jacobson Sandrich Goldstein, who was born in Rajec, Hungary (present-day Slovakia) and Jacob Goldstein, who was a rabbi originally from England. Her brother was director Mark Sandrich, and she was a cousin of silent film actress Carmel Myers.

Louise began working as a portrait photographer in 1922, working out of a music store down the block from the New Brunswick temple at which her father was a rabbi. Most of her photographs from this period are of family members and members of her father’s temple congregation.

In 1925 she moved to Los Angeles and set up a small photo studio on Hollywood and Vine. Louise’s first published Hollywood photo was of Vilma Banky in costume for Dark Angel, and appeared in Photoplay magazine in September 1925. When Louise was hired by MGM as chief portrait photographer, she was twenty-two years old, and the only woman working as a portrait photographer for the Hollywood studios. In a career that lasted only five years, Louise photographed all the stars, contract players, and many of the hopefuls who passed through the studio’s front gates, including Greta Garbo (Louise was one of only seven photographers permitted to make portraits of her), Lon Chaney, John Gilbert, Joan Crawford, Marion Davies, Anna May Wong, Nina Mae McKinney, and Norma Shearer. It is estimated that she took more than 100,000 photos during her tenure at MGM. Today she is considered an equal with George Hurrell Sr. and other renowned glamour photographers of the era.

In addition to paying close attention to costume and setting for studio photographs, Louise also incorporated aspects of modernist movements such as Cubism, futurism, and German expressionism into her studio portraits.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Carmel Myers (American, 1899-1980)

Carmel Myers (American, 1899-1980) was an American actress who achieved her greatest successes in silent film.

Myers left for New York City, where she acted mainly in theatre for the next two years. She was signed by Universal, where she emerged as a popular actress in vamp roles. Her most popular film from this period – which does not feature her in a vamp role – is probably the romantic comedy All Night, opposite Rudolph Valentino, who was then a little-known actor. She also worked with him in A Society Sensation. By 1924, she was working for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, making such films as Broadway After Dark, which also starred Adolphe Menjou, Norma Shearer, and Anna Q. Nilsson.

In 1925, she appeared in arguably her most famous role, that of the Egyptian vamp Iras in Ben-Hur, who tries to seduce both Messala (Francis X. Bushman) and Ben-Hur himself (Ramón Novarro). This film was a boost to her career, and she appeared in major roles throughout the 1920s, including Tell It to the Marines in 1926 with Lon Chaney, Sr., William Haines, and Eleanor Boardman. Myers appeared in Four Walls and Dream of Love, both with Joan Crawford in 1928; and in The Show of Shows (1929), a showcase of popular contemporary film actors.

Myers had a fairly successful sound career, mostly in supporting roles, perhaps due to her image as a vamp rather than as a sympathetic heroine. Subsequently, she began giving more attention to her private life following the birth of her son in May 1932. Amongst her popular sound films are Svengali (1931) and The Mad Genius (1931), both with John Barrymore and Marian Marsh, and a small role in 1944’s The Conspirators, which featured Paul Henreid, Peter Lorre, and Sydney Greenstreet.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Hildegard Rosenthal (Brazilian born Switzerland, 1913-1990)

Street Scene, São Paulo

c. 1940, printed later

Gelatin silver print

24 × 36cm (9 7/16 × 14 3/16 in.)

Instituto Moreira Salles

Hildegard Rosenthal (Brazilian born Switzerland, 1913-1990)

Hildegard Baum Rosenthal (March 25, 1913 – September 16, 1990) was a Swiss-born Brazilian photographer, the first woman photojournalist in Brazil. She was part of the generation of European photographers who emigrated during World War II and, acting in the local press, contributed to the photographic aesthetic renovation of Brazilian newspapers.

Rosenthal was born in Zurich, Switzerland. Until her adolescence, she lived in Frankfurt (Germany), where she studied pedagogy from 1929 until 1933. She lived in Paris between 1934 and 1935. Upon her return to Frankfurt, she studied photography for about 18 months in a program led by Paul Wolff [de]. Wolff emphasised small, portable cameras that used 35 mm film. These were a recent innovation at the time, and could be used unobtrusively for street photography. She also studied photographic laboratory techniques at the Gaedel Institute.