Exhibition dates: 22nd November, 2008 – 8th March, 2009

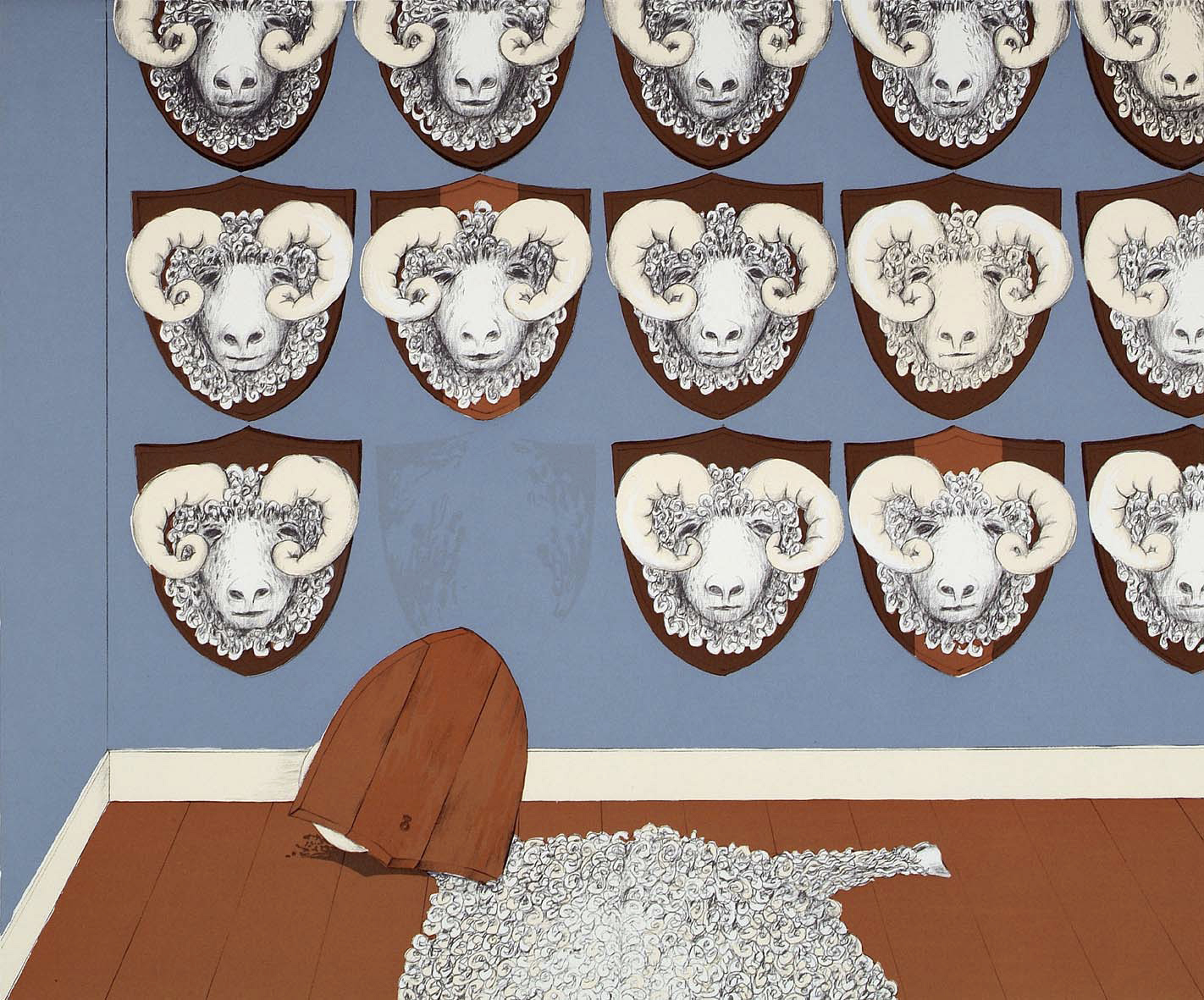

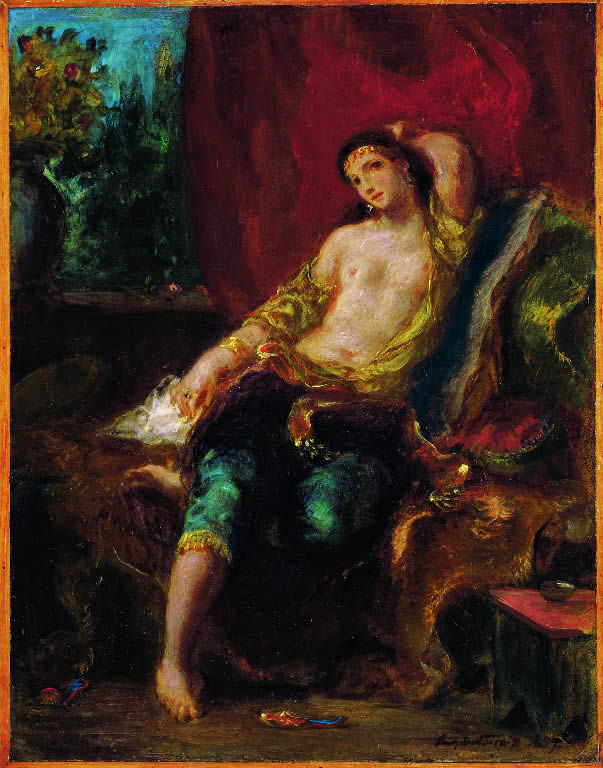

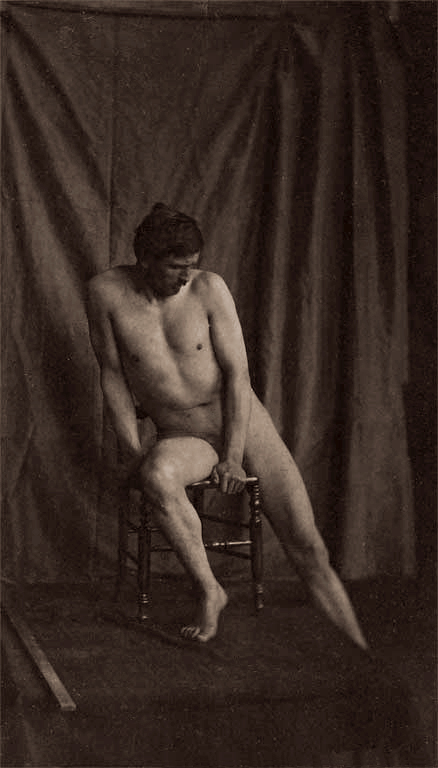

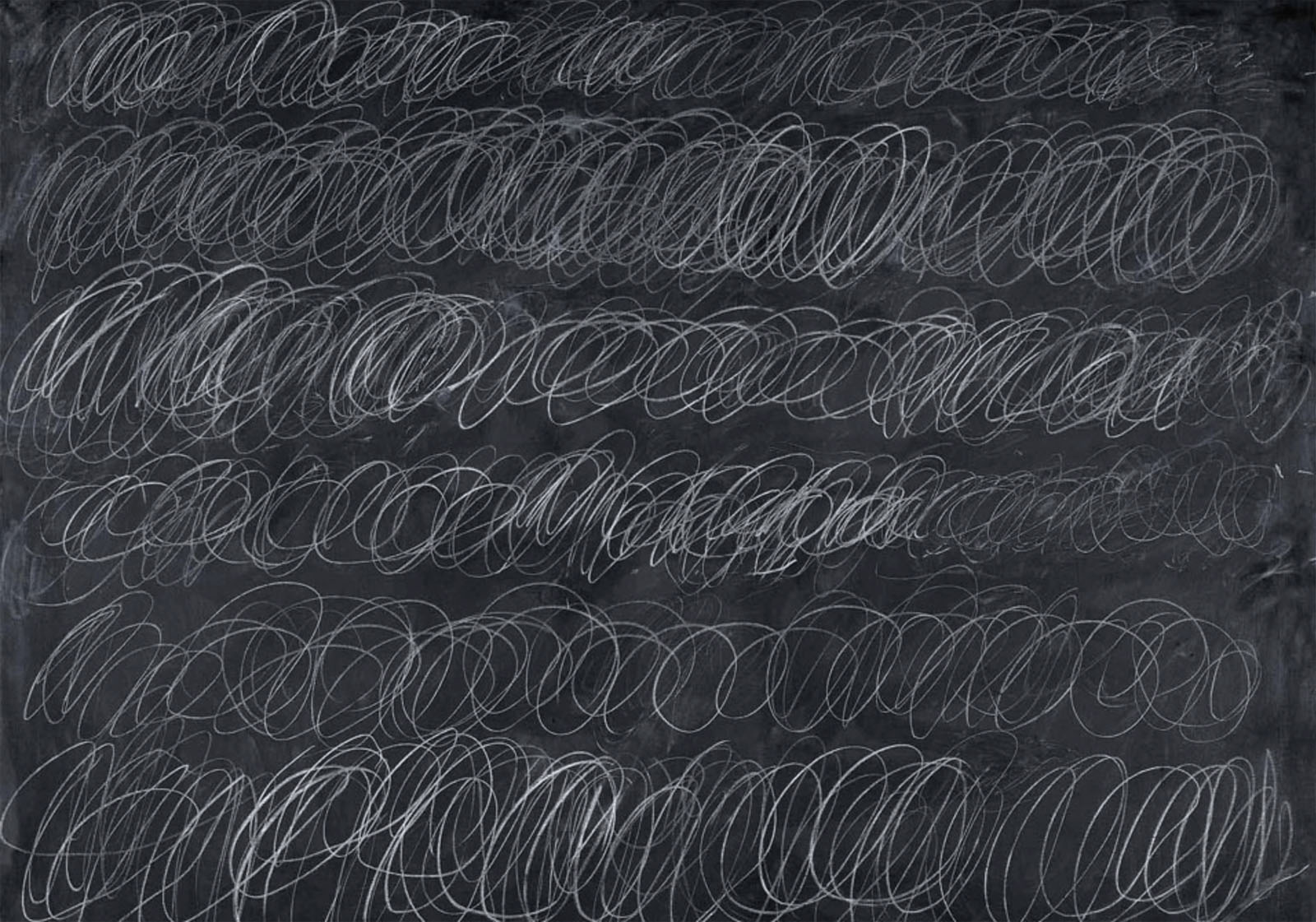

Les Kossatz (Australian, 1943-2011)

Digger’s glory box

1965

Silk, felt, canvas, cardboard, wood, brass, ink, fibre-tipped pen and synthetic polymer paint

106.0 x 76.0 x 7.0cm

Courtesy the artist

Photographer: Viki Petherbridge

© Les Kossatz

Heide Museum of Modern Art has brought together nearly 100 pieces of work by the Australian artist Les Kossatz in an eclectic survey show, appropriately titled The Art of Existence. Featuring sculpture, painting and mixed media from the 1960s to the present the exhibition is appropriately titled because Kossatz’s work addresses certain archetypal themes that affect human existence:

“His life-long fascination with the natural world and desire to understand both its human and animal inhabitants; exploration of the systems of knowledge and codes of behaviour that structure individual and communal life; and his critical and playful reflections on contemporary behaviour and the mysteries of existence.”1

Strong symbolic paintings are the focus of the work in the 1960s, paintings that address the shocking brutality of war and its aftermath, when soldiers return home. To the observation that these are of the ‘pop-style’ school of painting suggested by the Heide website I feel these works are also influenced by the collage of Cubism, the boxes of Joseph Cornell and the dismembered bodies of Francis Bacon. They engage with the symbolism of war and remembrance: memory, myth, and the banality of heroism and sacrifice.

The key work in this series is the painting Diggers throne (1966). This is a powerful disturbing image, effervescent and unnerving at the same time. It features a disembodied arm on the hand of a throne, surrounded by a wonderful kaleidoscopic assemblage of pictorial planes, artefacts and memories – an English flag, the flag of St George, a crown, medals and the words RSL. The arm reminds me of the Francis Bacon painting Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953) as it rests, roughly drawn in pencil on the arm of the throne, drawing the eye back up into nothingness.

The Diggers throne painting also features these prophetic words:

“throne slow to rot

and twisted the memory

becomes sacred.

Bloody was the truth

And this a chair.”

All other work in this period seems to flow through this painting – the other large paintings, the small canvases featuring individual medals and the less successful hanging banners. But it is to this work we return again and again as a viewer, trying to decipher and reconcile our inner conflicts about the painting.

As we move into the 1970s the work changes focus and direction. There emerges a concern with the desecration of the Australian landscape investigated in a series of large paintings and sculptures. In Packaged landscape 1 (1976) a steel suitcase with leather straps, slightly ajar, fulminates with artificial gum leaves trying to escape the strictures of the trap. In Caged landscape (1972) nature is again trapped behind steel wire, weighed in the balance on a set of miniature scales. The paintings feature trees that are surrounded by concrete and the rabbit becomes a powerful symbol for Kossatz – a suffering beast, strung up on fences, a plague in a pitted landscape of chopped down trees, erosion and empty holes.

Into this vernacular emerges the key symbol of the artist’s oeuvre – the sheep. In 1972 Kossatz began a series of sculptures of sheep, “initially inspired by the experience of nursing an injured ram.” For Kossatz “the sheep represent the hardship of pioneer existence, the grazing industries prosperity, environmental concerns and the sheep act as narrative devices, potent metaphors for human behaviour.”2

The first sheep presented ‘in show’ is Ram in Sling (1973, below). In this sculpture a metal bar is suspended in mid-air and from this bar heavy wire mesh drops to support the fleecy stomach and neck of the ram almost seeming to strangle it in the process, it’s metal feet just touching the ground. Again the scales of justice seem to weigh nature in the balance.

The themes life and death, order and chaos are further developed in the work Hard slide (1980, below) where a sheep emerges mid-air from a trapdoor, two more tumble down a wooden slide end over end and another disappears into the ground through a wooden trapdoor opening. Sacrifice seems to be a consistent theme with both the earlier paintings and the metallised sheep:

“The completed life cycle, down the trapdoor, down the chute, after sacrifice by shearing.” ~ Daniel Thomas 1994

Further sculptures of sheep, both small maquettes and large sculptures follow in the next room of the exhibition. This is the artist is full flow, featuring the inventive taking of 2D things into the round, investigating the key themes of his work: the contrast between nature and artifice, or humanity.

The small maquettes of sheep feature races, gantries, sluices, pens, trapdoors and paddocks. Sheep tumble in a cataclysmic maelstrom, falling with flailing legs into the darkness of the holding pen below. These are my favourite works – small, intimate, detailed, dark bronzes of serious intensity – the sheep becoming a theatre of the absurd, suspended, weighed and balancing in the performance of ritualised acts, a cacophony of flesh at once both intricate and unsettling. Their skins lay flayed and lifeless disappearing into the ‘unearth’ of the slated wooden floor of the shearing shed. The sheep “can be viewed metaphorically as a commentary of the existential situation of the individual and collective behaviour.”3 As Kossatz himself has noted, “It is hard to bring a piece of landscape inside and give it a living animated form. The sheep somehow gives me this quality of landscape.”

But we must also remember that this strictly a white man’s view of the Australian landscape. Nowhere does this work comment on the disenfranchisement of the native people’s of this land – the destruction of native habitats that the sheep brought about, the starvation that they caused to Aboriginal people just as they bought riches to the pastoralists and the country that mined the land with this amorphous mass of flesh.

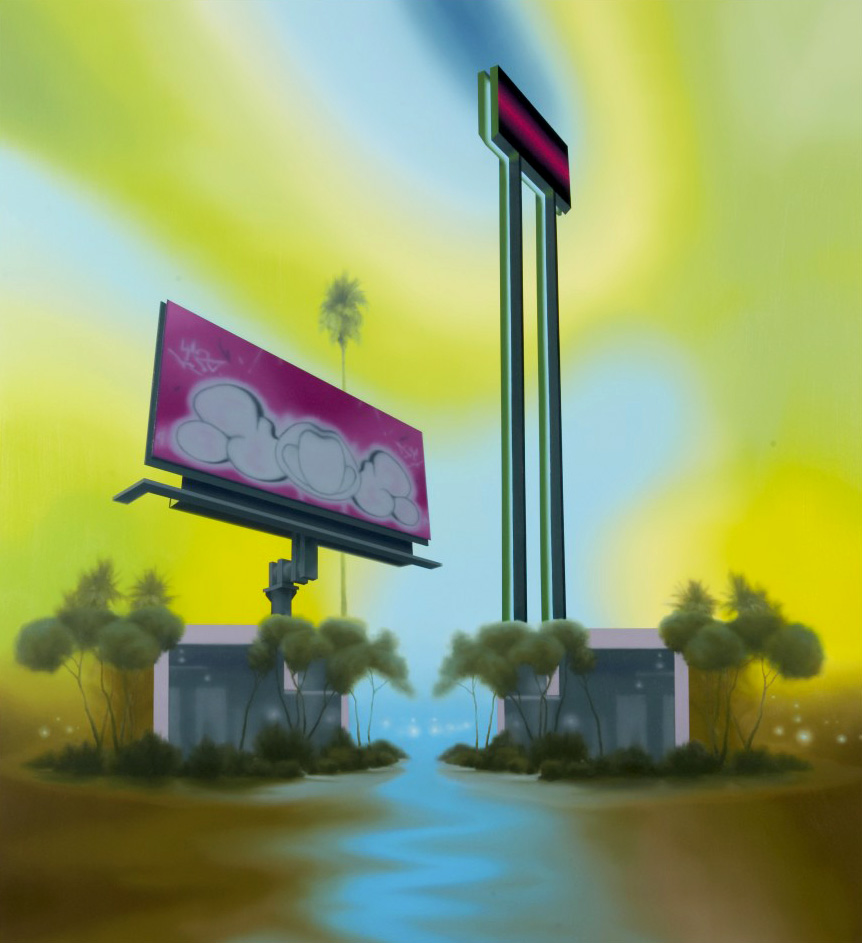

Recent work in the exhibition returns to the earlier social themes of memory, war, remembrance, religion, shrines, atomic clouds and temples but it is the work of the late 1970s-1980s that is the most cogent. As Kossatz ponders the nature of existence on this planet he does not see a definitive answer but emphasises the journey we take, not the arrival. Here is something that we should all ponder, giving time to the nature of our personal journey in this life, on this earth.

Here also is an exhibition worthy our time and attention as part of that journey. Go visit!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,074

1/ From the Heide website

2/ From wall notes to the exhibition

3/ From wall notes to the exhibition

Many thankx to Heide Museum of Modern Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Postscript 2018

The late Les Kossatz (1943-2011) was a well known Melbourne-based artist and academic whose work is represented in many regional and state galleries and the National Gallery of Australia. He studied art at the Melbourne Teachers’ College and the RMIT, and went on to teach at the RMIT and Monash University. Kossatz’s first significant commission was for the stained glass windows at the Monash University Chapel in Melbourne. Later commissions included works for the Australian War Memorial, the High Court, the Ian Potter Foundation at the National Gallery of Victoria and the Darling Harbour Authority, Sydney. His sculpture, Ainslie’s Sheep, commissioned by Arts ACT in 2000, is a popular national capital landmark in the centre of Civic. A major retrospective of Kossatz’s work was held in 2009 at the Heide Park and Art Gallery, Melbourne.

Text from the High Court of Australia website

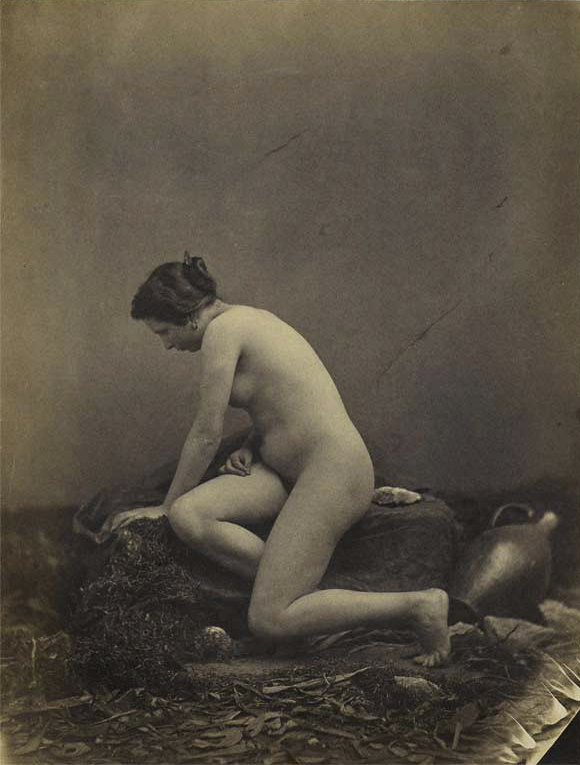

Francis Bacon (British born Ireland, 1909-1992)

Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X

1953

Oil on canvas

Les Kossatz (Australian, 1943-2011)

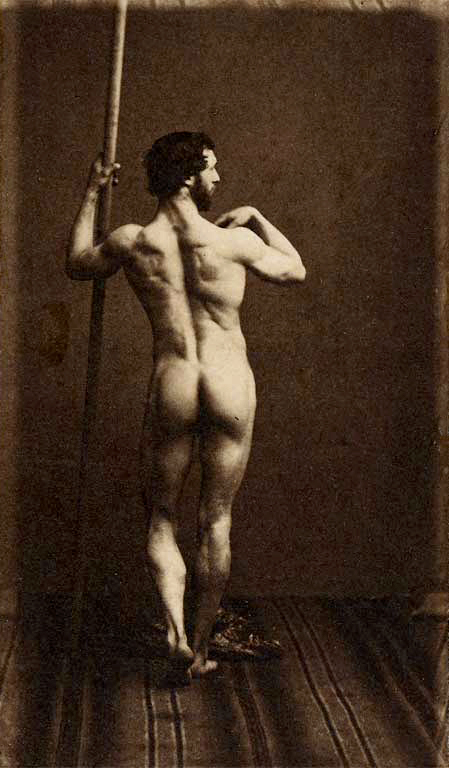

Ram in sling

1973

Cast and fabricated stainless steel and sheepskin

129.3 x 126.5 x 66.0cm

Heide Museum of Modern Art Collection

Purchased from John and Sunday Reed 1980

© Les Kossatz

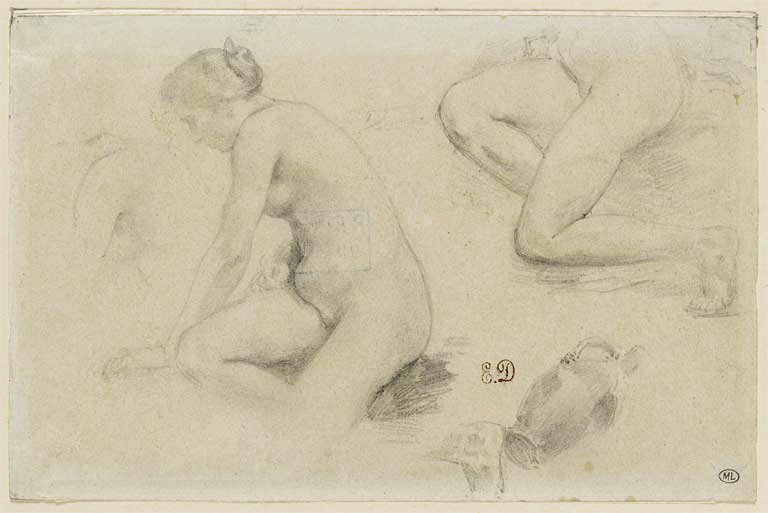

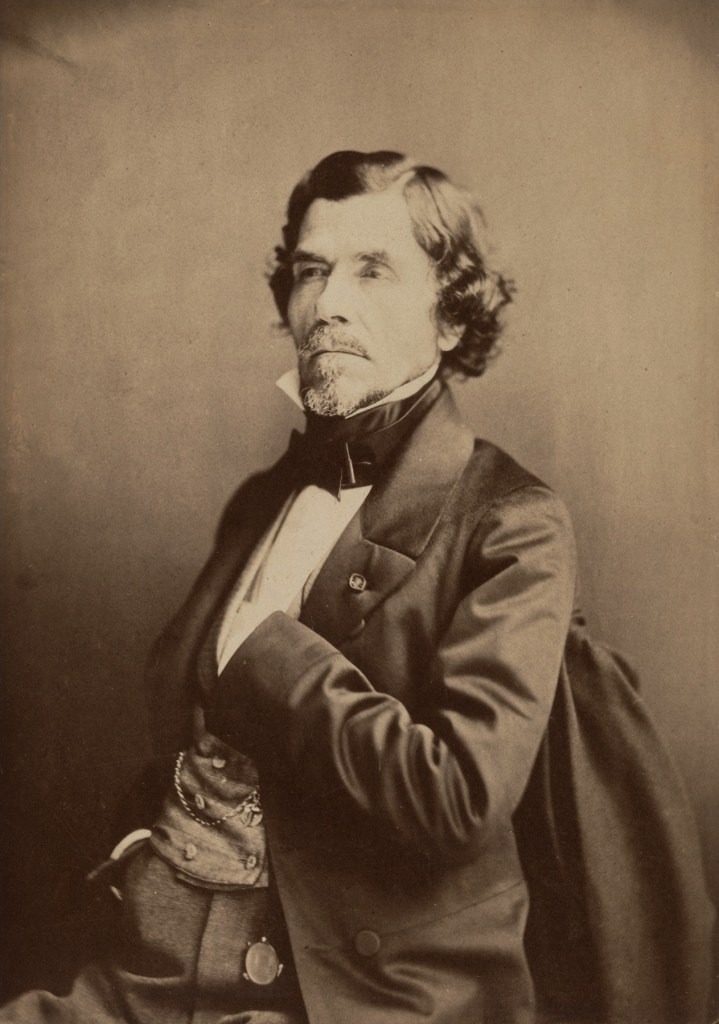

Les Kossatz (Australian, 1943-2011)

Trophy room

1975

Colour lithograph

74.0 x 76.0cm (sheet)

Courtesy the artist

Photographer: Viki Petherbridge

© Les Kossatz

The art of existence is the first exhibition to review Les Kossatz’s contribution to Australian art in a career that spans the 1960s to today. Kossatz’s consistently experimental approach to media and techniques is revealed in works that display a lifelong fascination with humanity and the interaction of man and nature. His paintings, sculptures and works on paper stimulate a questioning and exploration of such concerns, which form the basis of this artist’s practice.

Les Kossatz’s early works of the 1960s draw on his training and ability to work across a diversity of media, including painting, drawing, printmaking and glass. Early paintings and etchings on the theme of the emptiness of memorials to the Australian ‘digger’ or soldiers were succeeded by images and objects offering impressions of the world around the artist – the rural domain and interior life of St Andrews in Victoria where Kossatz lived and worked. Such works demonstrated his determination to pursue a figurative practice at a time when abstract art had been imported to Australia and was considered the avant garde.

Remaining a staunchly independent artist, at the start of the 1970s Kossatz painted images of rabbits and sheep from St Andrews. In addition, the practice of working in three dimensions was to become more significant. Kossatz continued to develop familiar themes in the creation of installations and cast objects. Although he has produced drawings and prints across his career, working with sculpture has, since the early 1970s, been his primary mode of art-making. Large scale cast and assembled objects show Kossatz pursuing related themes of caged and packaged landscapes, shrines to the harvest and the still life.

The art of existence surveys Kossatz’s monumental life-sized sheep sculptures, which he began making in 1972 from casts of animal parts, and for which he is best known. These include Hard slide (1980), his prize-winning commission in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. Kossatz has won numerous commissions for outdoor sculptures that employ the sheep as literal and metaphorical beings. Kossatz’s work across three decades reveals a number of ongoing engagements, such as his observations of human behaviour and at times its similar manifestation in animals; the beliefs that sustain individuals and communities (such as religion, music and politics); and the forms of the landscape and our understanding of these relationships.

Introduction to the exhibition written by Zara Stanhope, Guest Curator, Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2008

Les Kossatz (Australian, 1943-2011)

Hard slide

1980

Sheepskins, aluminium, Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga sp.), leather, steel

372.0 x 100.0 x 304.0cm (installation)

Les Kossatz (Australian, 1943-2011)

Guggenheim spiral

1983

Heide Museum of Modern Art

7 Templestowe Road

Bulleen Victoria 3105 Australia

Phone: +61 3 9850 1500

Opening hours:

(Heide II and Heide III)

Tuesday to Sunday and public holidays, 10am – 5pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.