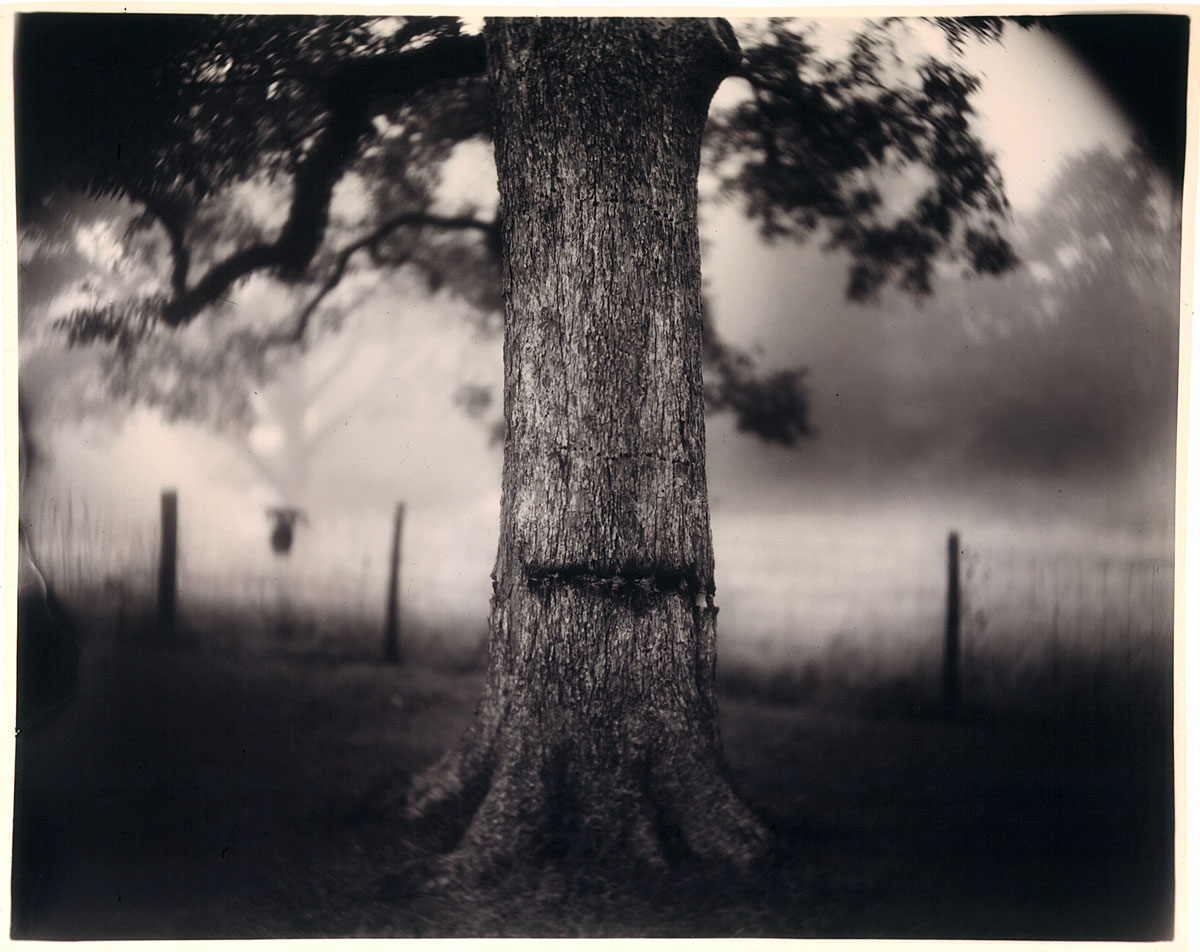

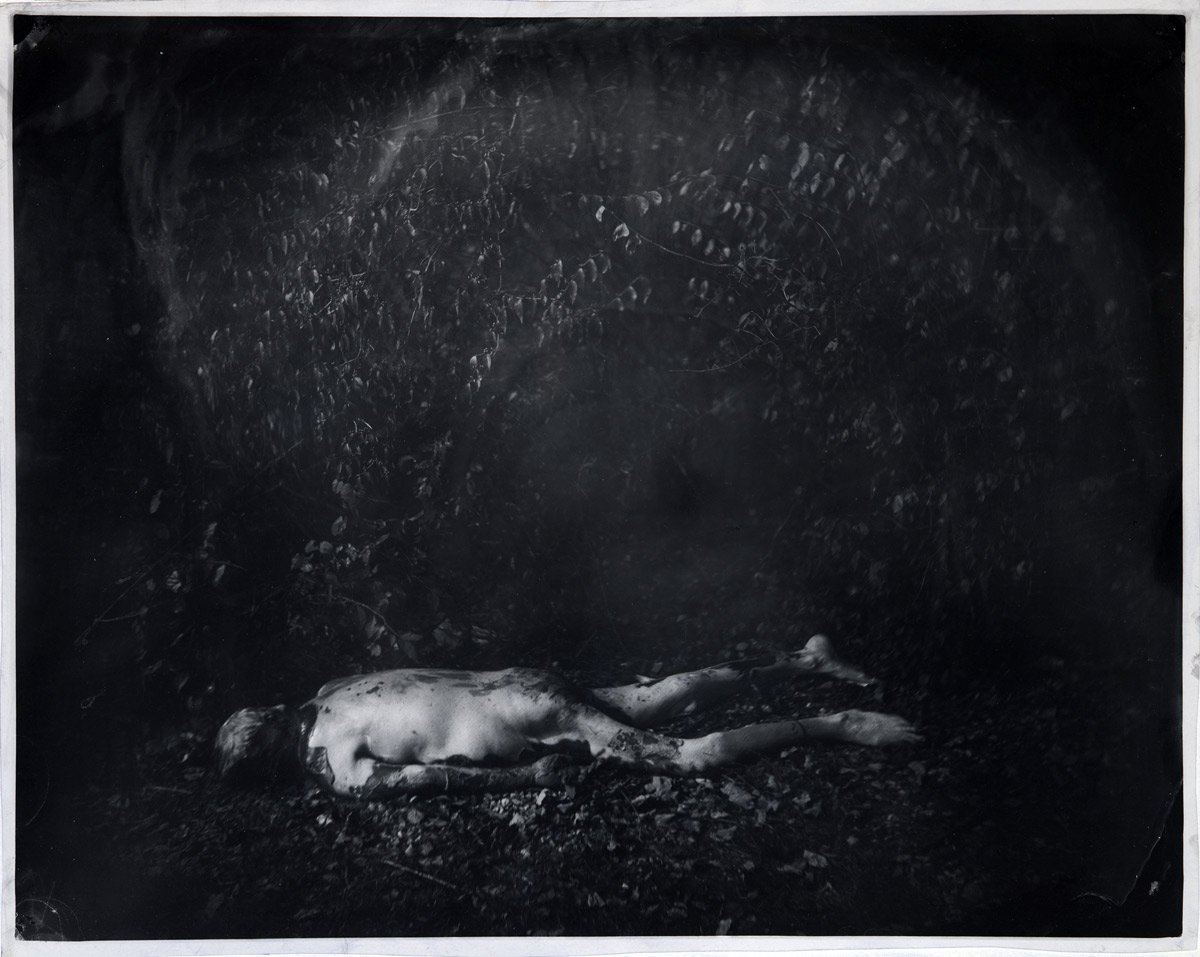

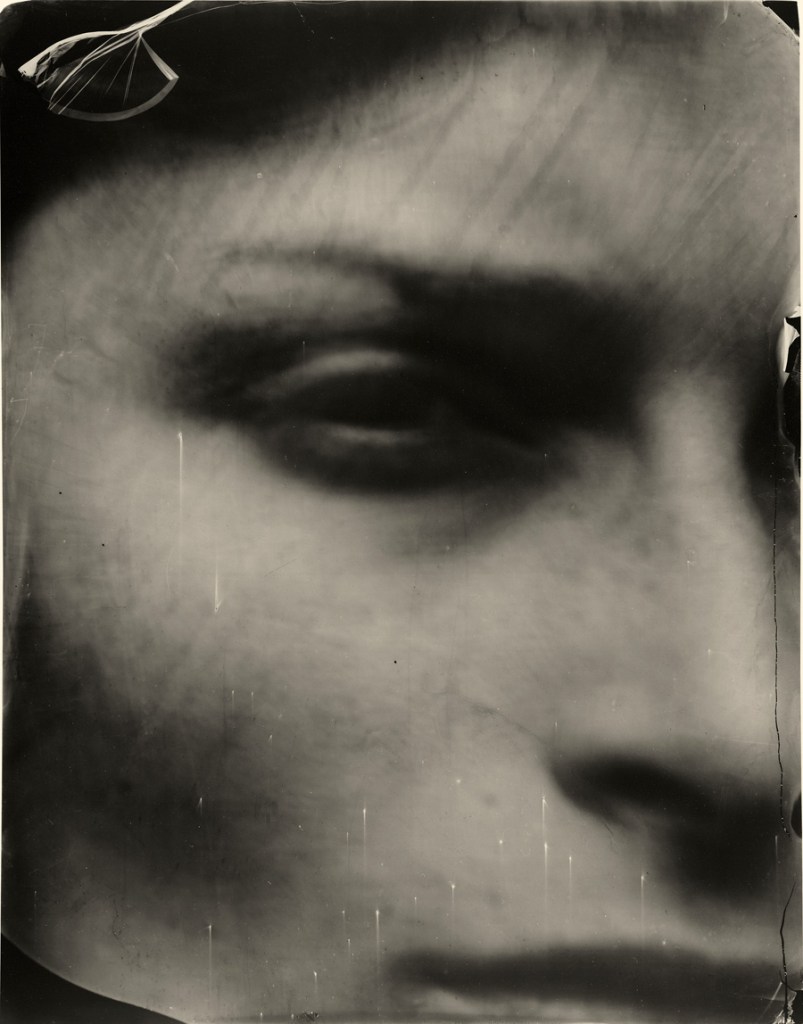

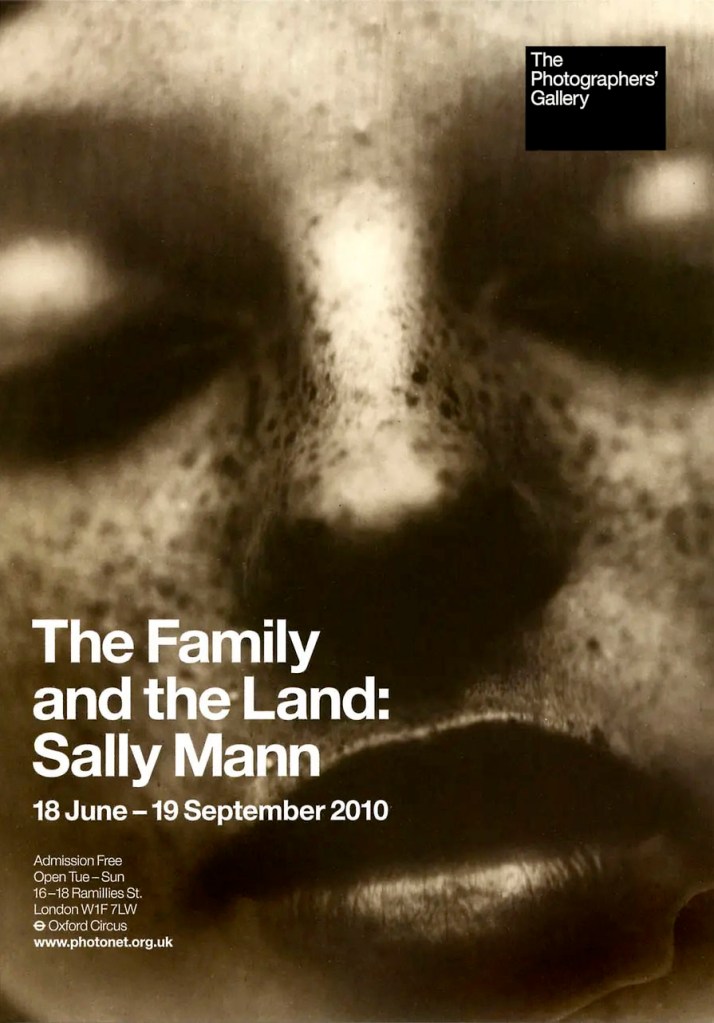

Exhibition dates: 1st August – 1st November 2010

A huge posting of wonderful photographs!

Many thankx to the Museum of Modern Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Rubber Dummies, Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studios, Hollywood

1939

Gelatin silver print

7 9/16 x 9 5/8″ (19.3 x 24.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Edward Steichen

© 1981 Collection Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

David Goldblatt (South African, 1930-2018)

Monument to Karel Landman, Voortrekker Leader, De Kol, Eastern Cape

April 10, 1993

Gelatin silver print

10 15/16 x 13 11/16″ (27.9 x 34.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase

© 2010 David Goldblatt. Courtesy David Goldblatt and the Goodman Gallery

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Saint-Cloud

1923

Albumen silver print

6 7/8 x 8 3/8″ (17.5 x 21.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Anonymous gift

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

Midnight – Rodin’s Balzac

1908

Pigment print

12 1/8 x 14 5/8″ (30.8 x 37.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the photographer

Permission of Joanna T. Steichen

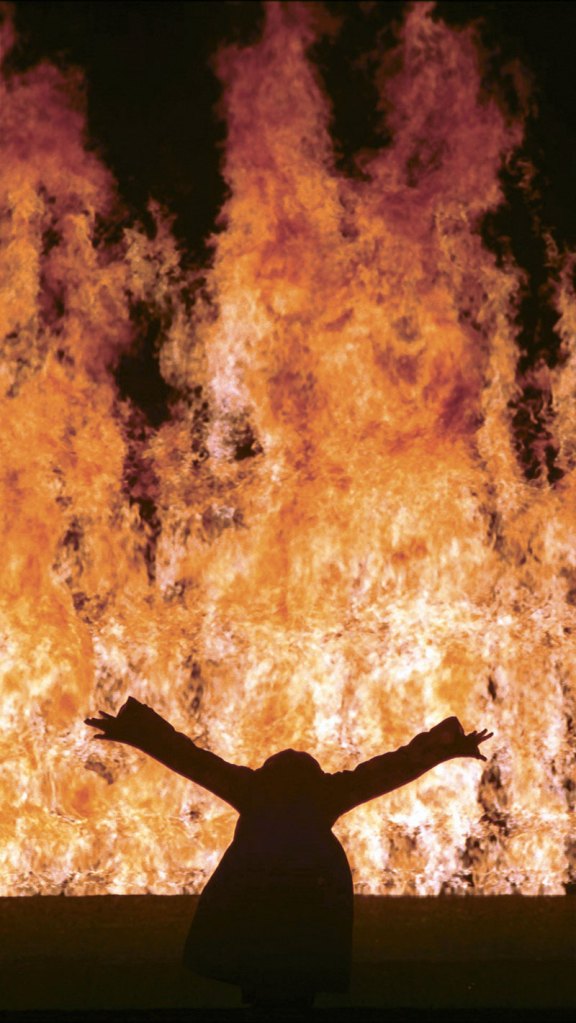

Bruce Nauman (American, b. 1941)

Waxing Hot from the portfolio Eleven Color Photographs

1966-1967/1970/2007

Inkjet print (originally chromogenic colour print)

19 15/16 x 19 15/16″ (50.6 x 50.6cm)

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Gerald S. Elliott Collection

© 2010 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

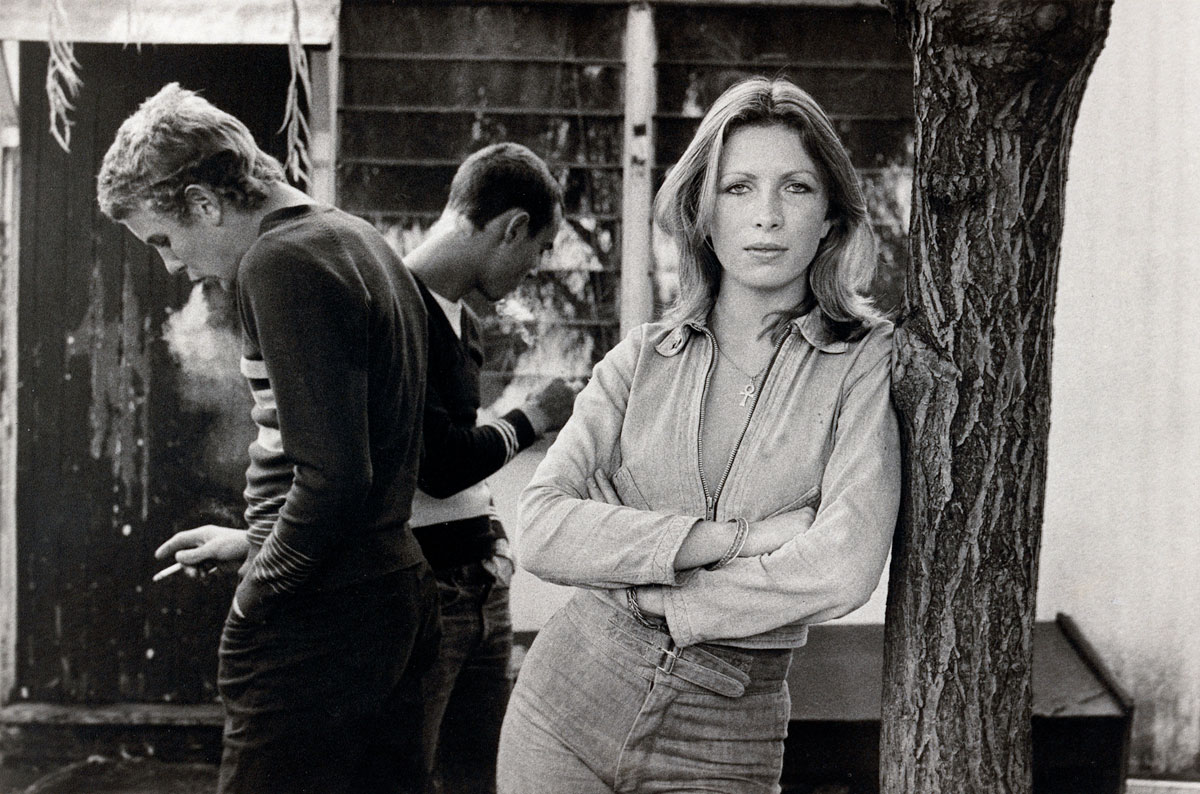

Gilbert & George (Gilbert Proesch. British, b. Italy 1943. George Passmore. British, b. 1942)

Great Expectations

1972

Dye transfer print

11 9/16 x 11 1/2″ (29.4 x 29.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Art & Project/Depot VBVR

© 2010 Gilbert & George

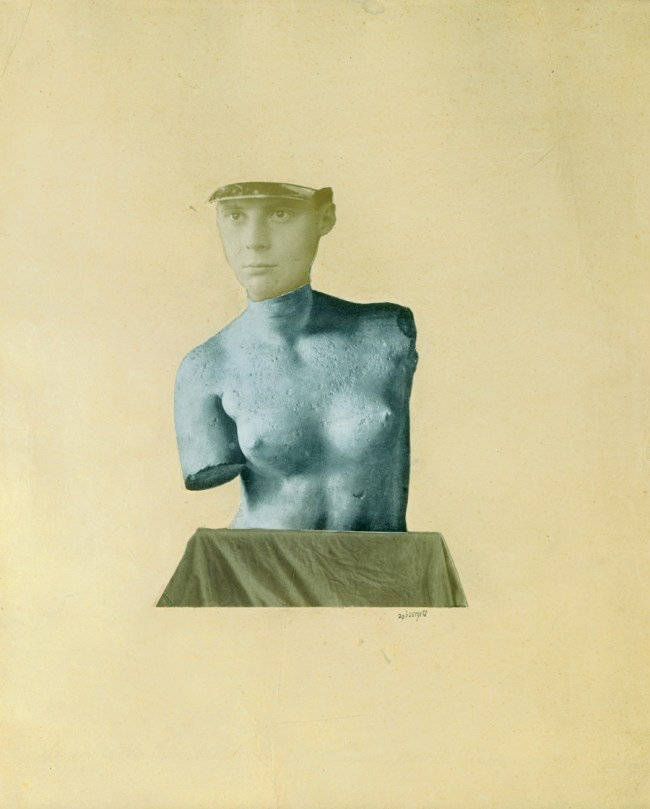

Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975)

The Doll

1935-1937

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 x 9 5/16″ (24.1 x 23.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Samuel J. Wagstaff, Jr. Fund

© 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today presents a critical examination of the intersections between photography and sculpture, exploring how one medium informs the analysis and creative redefinition of the other. On view at The Museum of Modern Art from August 1 through November 1, 2010, the exhibition brings together over 300 photographs, magazines, and journals, by more than 100 artists, from the dawn of modernism to the present, to look at the ways in which photography at once informs and challenges the meaning of what sculpture is. The Original Copy is organised by Roxana Marcoci, Curator, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art. Following the exhibition’s presentation at MoMA, it will travel to Kunsthaus Zürich, where it will be on view from February 25 through May 15, 2011.

When photography was introduced in 1839, aesthetic experience was firmly rooted in Romanticist tenets of originality. In a radical way, photography brought into focus the critical role that the copy plays in art and in its perception. While the reproducibility of the photograph challenged the aura attributed to the original, it also reflected a very personal form of study and offered a model of dissemination that would transform the entire nature of art.

“In his 1947 book Le Musée Imaginaire, the novelist and politician André Malraux famously advocated for a pancultural ‘museum without walls,’ postulating that art history, and the history of sculpture in particular, had become ‘the history of that which can be photographed,'” said Ms. Marcoci.

Sculpture was among the first subjects to be treated in photography. There were many reasons for this, including the desire to document, collect, publicise, and circulate objects that were not always portable. Through crop, focus, angle of view, degree of close-up, and lighting, as well as through ex post facto techniques of dark room manipulation, collage, montage, and assemblage, photographers have not only interpreted sculpture but have created stunning reinventions of it.

Conceived around ten conceptual modules, the exhibition examines the rich historical legacy of photography and the aesthetic shifts that have taken place in the medium over the last 170 years through a superb selection of pictures by key modern, avant-garde, and contemporary artists. Some, like Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, Lee Friedlander, and David Goldblatt, are best known as photographers; others, such as Auguste Rodin, Constantin Brancusi, and David Smith, are best known as sculptors; and others, from Hannah Höch and Sophie Taeuber-Arp to such contemporaries as Bruce Nauman, Fischli/Weiss, Rachel Harrison, and Cyprien Gaillard, are too various to categorise but exemplify how fruitfully and unpredictably photography and sculpture have combined.

The Original Copy begins with Sculpture in the Age of Photography, a section comprising early photographs of sculptures in French cathedrals by Charles Nègre and in the British Museum by Roger Fenton and Stephen Thompson; a selection of André Kertész’s photographs from the 1920s showing art amid common objects in the studios of artist friends; and pictures by Barbara Kruger and Louise Lawler that foreground issues of representation to underscore photography’s engagement in the analysis of virtually every aspect of art. Eugène Atget: The Marvelous in the Everyday presents an impressive selection of Atget’s photographs, dating from the early 1900s to the mid 1920s, of classical statues, reliefs, fountains, and other decorative fragments in Paris, Versailles, Saint-Cloud, and Sceaux, which together amount to a visual compendium of the heritage of French civilisation at the time.

Auguste Rodin: The Sculptor and the Photographic Enterprise includes some of the most memorable pictures of Rodin’s sculptures by various photographers, including Edward Steichen’s Rodin – The Thinker (1902), a work made by combining two negatives: one depicting Rodin in silhouetted profile, contemplating The Thinker (1880-82), his alter ego; and one of the artist’s luminous Monument to Victor Hugo (1901). Constantin Brancusi: The Studio as Groupe Mobile focuses on Brancusi’s uniquely nontraditional techniques in photographing his studio, which was articulated around hybrid, transitory configurations known as groupe mobiles (mobile groups), each comprising several pieces of sculpture, bases, and pedestals grouped in proximity. In search of transparency, kineticism, and infinity, Brancusi used photography to dematerialise the static, monolithic materiality of traditional sculpture. His so-called photos radieuses (radiant photos) are characterised by flashes of light that explode the sculptural gestalt.

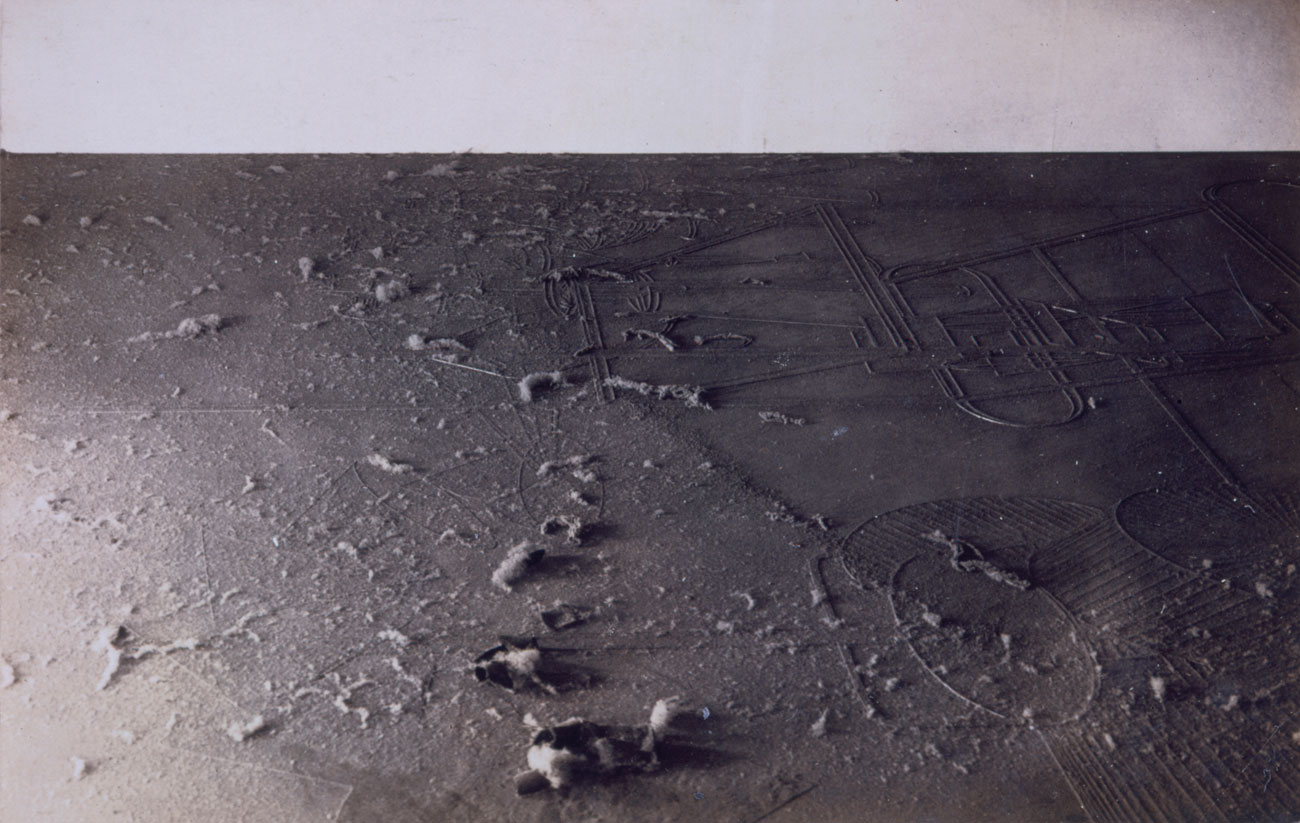

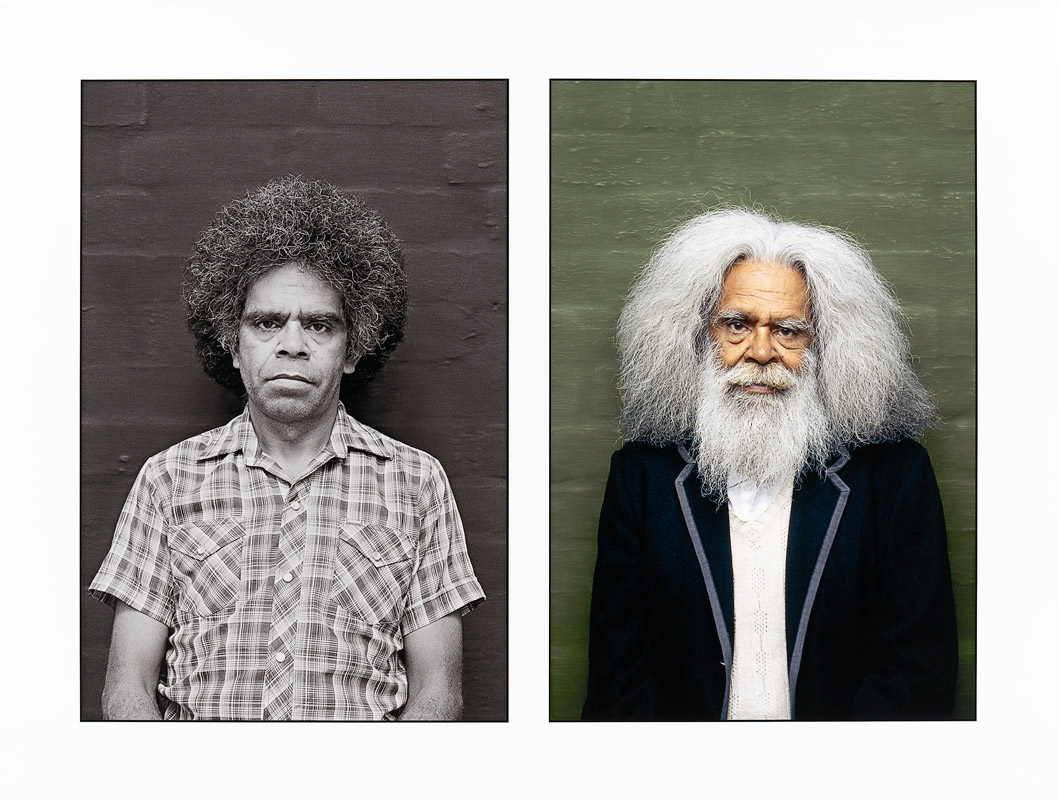

Marcel Duchamp: The Readymade as Reproduction examines Box in a Valise (1935-41), a catalogue of his oeuvre featuring 69 reproductions, including minute replicas of several readymades and one original work that Duchamp “copyrighted” in the name of his female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy. Using collotype printing and pochoir – in which colour is applied by hand with the use of stencils – Duchamp produced “authorised ‘original’ copies” of his work, blurring the boundaries between unique object, readymade, and multiple. Cultural and Political Icons includes selections focusing on some of the most significant photographic essays of the twentieth century – Walker Evans’s American Photographs (1938), Robert Franks’s The Americans (1958), Lee Friedlander’s The American Monument (1976), and David Goldblatt’s The Structure of Things Then (1998) – many of which have never before been shown in a thematic context as they are here.

The Studio without Walls: Sculpture in the Expanded Field explores the radical changes that occurred in the definition of sculpture when a number of artists who did not consider themselves photographers in the traditional sense, such as Robert Smithson, Robert Barry, and Gordon Matta-Clark, began using the camera to document remote sites as sculpture rather than the traditional three-dimensional object. Daguerre’s Soup: What Is Sculpture? includes photographs of found objects or assemblages created specifically for the camera by artists, such as Brassaï’s Involuntary Sculptures (c. 1930s), Alina Szapocznikow’s Photosculptures (1970-1971), and Marcel Broodthaers’s Daguerre’s Soup (1974), the last work being a tongue-in-cheek picture which hints at the various fluid and chemical processes used by Louis Daguerre to invent photography in the nineteenth century, bringing into play experimental ideas about the realm of everyday objects.

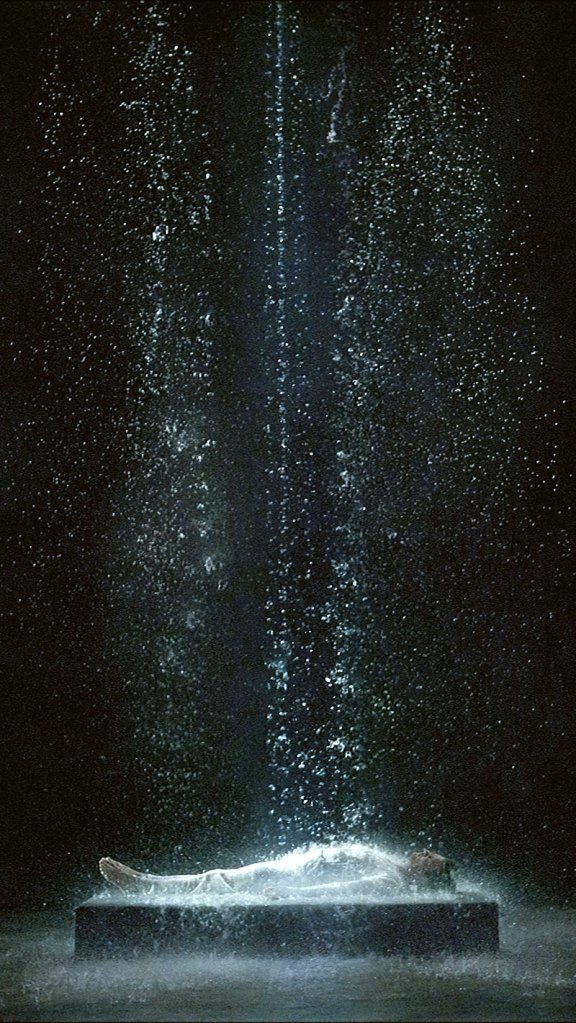

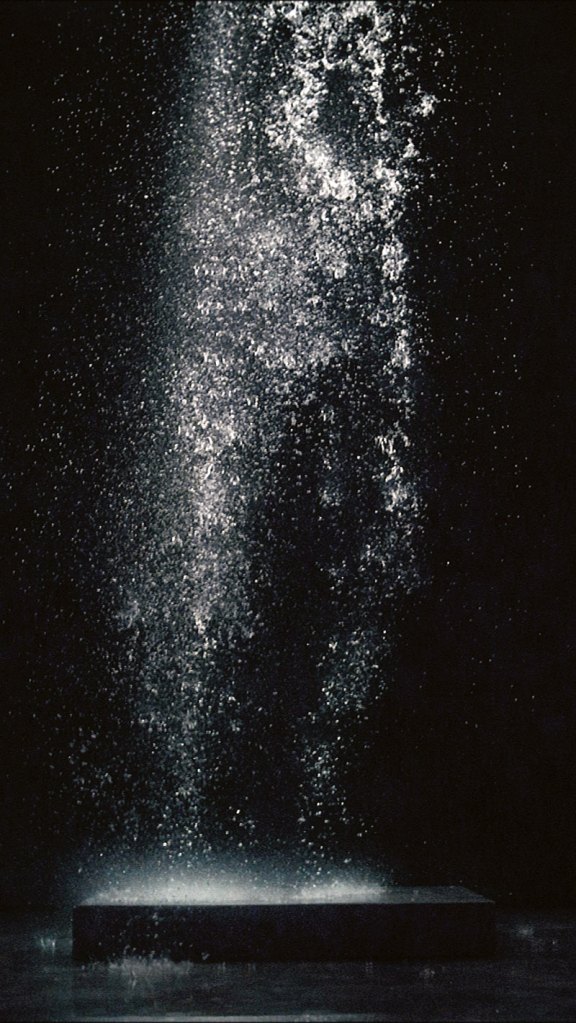

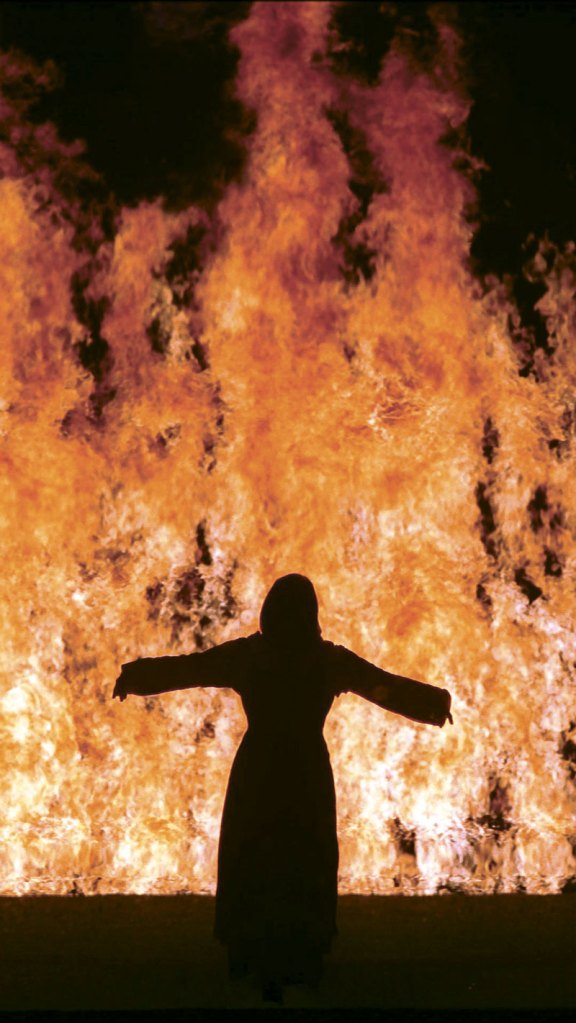

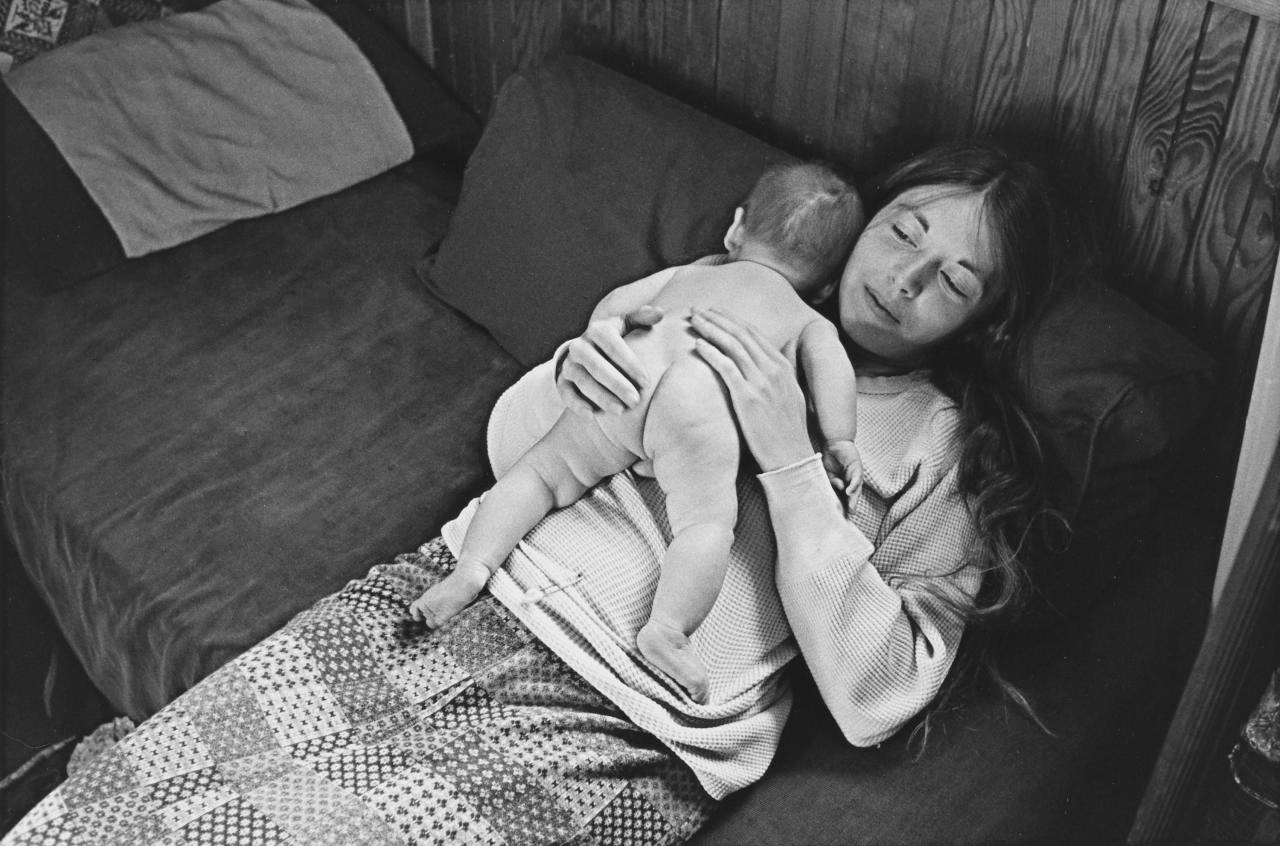

The Pygmalion Complex: Animate and Inanimate Figures looks at Dada and Surrealist pictures and photo-collages by artists, including Man Ray, Herbert Bayer, Hans Bellmer, Hannah Höch, and Johannes Theodor Baargeld, who focused their lenses on mannequins, dummies, and automata to reveal the tension between living figure and sculpture. The Performing Body as Sculptural Object explores the key role of photography in the intersection of performance and sculpture. Bruce Nauman, Charles Ray, and Dennis Oppenheim, placing a premium on their training as sculptors, articulated the body as a sculptural prop to be picked up, bent, or deployed instead of traditional materials. Eleanor Antin, Ana Mendieta, VALIE EXPORT, and Hannah Wilke engaged with the “rhetoric of the pose,” using the camera as an agency that itself generates actions through its presence.

Press release from the Museum of Modern Art website

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky) (American, 1890-1976)

Noire et blanche (Black and white)

1926

Gelatin silver print

6 3/4 x 8 7/8″ (17.1 x 22.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of James Thrall Soby

2010 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Stamped Tin Relic

1929 (printed c. 1970)

Gelatin silver print

4 11/16 x 6 5/8″ (11.9 x 16.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Lily Auchincloss Fund

© 2010 Estate of Walker Evans

Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

Mount Rushmore, South Dakota

1969

Gelatin silver print

8 1/16 x 12 1/8″ (20.5 x 30.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the photographer

© 2010 Lee Friedlander

Sibylle Bergemann (German, 1941-2010)

Das Denkmal, East Berlin (The monument, East Berlin)

1986

Gelatin silver print

19 11/16 x 23 5/8″ (50 x 60cm)

Sibylle Bergemann/Ostkreuz Agentur der Fotografen, Berlin

© 2010 Sibylle Bergemann/Ostkreuz Agentur der Fotografen, Berlin

Marcel Duchamp (American, born France, 1887-1968)

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky) (American, 1890-1976)

Élevage de poussière (Dust breeding)

1920

Gelatin silver contact print

2 13/16 x 4 5/16″ (7.1 x 11cm)

The Bluff Collection, LP

© 2010 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Guy Tillim (South African, b. 1962)

Bust of Agostinho Neto, Quibala, Angola

2008

Pigmented inkjet print

17 3/16 x 25 3/4″ (43.6 x 65.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of the Contemporary Arts Council of The Museum of Modern Art

© 2010 Guy Tillim. Courtesy Michael Stevenson Gallery

Selected wall text from the exhibition

“The advent of photography in 1839, when aesthetic experience was firmly rooted in Romanticist tenets of originality, brought into focus the critical role that the copy plays in the perception of art. The medium’s reproducibility challenged the aura attributed to the original, but it also reflected a new way of looking and offered a model for dissemination that would transform the entire nature of art. The aesthetic singularity of the photograph, the archival value of a document bearing the trace of history, and the combinatory capacity of the image, open to be edited into sequences in which it mixes with others – all these contribute to the status of photography as both an art form and a medium of communication.

Sculpture was among the first subjects to be treated in photography. In his 1947 book Le Musée imaginaire, the novelist and politician André Malraux famously advocated for a pancultural “museum without walls,” postulating that art history, and the history of sculpture in particular, had become “the history of that which can be photographed.” There were many reasons for this, including the immobility of sculpture, which suited the long exposure times needed with the early photographic processes, and the desire to document, collect, publicise and circulate objects that were not always portable. Through crop, focus, angle of view, degree of close-up, and lighting, as well as through ex post facto techniques of dark room manipulation, collage, montage, and assemblage, photographers not only interpret sculpture but create stunning reinventions of it.

The Original Copy presents a critical examination of the intersections between photography and sculpture, exploring how the one medium has been implicated in the analysis and creative redefinition of the other. Bringing together 300 pictures, magazines and journals by more than 100 artists from the dawn of modernism to the present, this exhibition looks at the ways in which photography at once informs and challenges our understanding of what sculpture is within specific historic contexts.

Sculpture in the Age of Photography

If we consider photography a child of the industrial era – a medium that came of age alongside the steam engine and the railroad – it is not surprising that one of its critical functions was to bring physically inaccessible worlds closer by means of reproduction. Among its early practitioners, Charles Nègre photographed sculpture in the cathedrals of Chartres, Amiens, and, in Paris, Notre Dame, circling them at different levels to capture perspectives of rarely seen sculptural details, while in London Roger Fenton and Stephen Thompson documented the ancient statuary in the British Museum, making visible the new power of collecting institutions.

With the advent of the handheld portable camera in the early 1920s, photographers had the flexibility to capture contingent sculptural arrangements taken from elliptical viewpoints. André Kertész, for instance, recorded unexpected juxtapositions between art and common objects in the studios of artist friends, including Fernand Léger and Ossip Zadkine. His ability to forge heterogeneous materials and objects into visual unity inspired the novelist Pierre Mac Orlan to confer on him the title of “photographer-poet.”

Focusing on details in this way, photographers have interpreted not only sculpture itself, as an autonomous object, but also the context of its display. The results often show that the meaning of art is not fixed within the work but open to the beholder’s reception of it at any given moment. Taking a place in the tradition of institutional critique, Barbara Kruger’s and Louise Lawler’s pictures foreground issues of representation to underscore photography’s engagement in the analysis of virtually every aspect of art.

Eugène Atget

The Marvelous in the Everyday

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, Atget took hundreds of photographs of sculptures – classical statues, reliefs, fountains, door knockers, and other finely wrought decorative fragments – in Paris and its outlying parks and gardens, especially at Versailles, Saint-Cloud, and Sceaux. These images amount to a visual compendium of the heritage of French civilisation at that time.

At Versailles, most intensely between 1901 and 1906 and again between 1921 and 1926, Atget photographed the gardens that André Le Nôtre, the landscape architect of King Louis XIV, had designed in the second half of the seventeenth century. In a series of pictures of allegorical statues punctuating the garden’s vistas, Atget focused on the scenic organisation of the sculptures, treating them as characters in a historical play. The pantomimic effect of the statues’ postures clearly appealed to Atget, who in 1880, before turning to photography, had taken acting classes at the Conservatory of the Théâtre national de France. Depicting the white marble statues from low viewpoints, in full length, and against the dark, unified tones of hedges and trees, Atget brought them into dramatic relief, highlighting the theatrical possibilities of sculpture.

Among the pictures taken at Saint-Cloud is a series centred on a melancholy pool surrounded by statues whose tiny silhouettes can be seen from a distance. Atget’s interest in the variable play between nature and art through minute changes in the camera’s angle, or as functions of the effects of light and time of day, is underscored in his notations of the exact month and sometimes even the hour when the pictures were taken.

Auguste Rodin

The Sculptor and the Photographic Enterprise

Rodin never took pictures of his sculptures but reserved the creative act for himself, actively directing the enterprise of photographing his work. He controlled staging, lighting and background, and he was probably the first sculptor to enlist the camera to record the changing stages through which his work passed from conception to realisation. The photographers working with Rodin were diverse and their images of his work varied greatly, partly through each individual’s artistic sensibility and partly through changes in the photographic medium. The radical viewing angles that Eugène Druet, for instance, adopted in his pictures of hands, in around 1898, inspired the poet Rainer Maria Rilke to write: “There are among the works of Rodin hands, single small hands which without belonging to a body, are alive. Hands that rise, irritated and in wrath; hands whose five bristling fingers seem to bark like the five jaws of a dog of Hell.”

Among the most memorable pictures of Rodin’s sculptures is Edward Steichen’s Rodin – The Thinker (1902), a work made by combining two negatives: Rodin in dark silhouetted profile contemplating The Thinker (1880-1882), his alter ego, is set against the luminous Monument to Victor Hugo (1901), a source of poetic creativity. Steichen also photographed Rodin’s Balzac, installed outdoors in the sculptor’s garden at Meudon, spending a whole night taking varying exposures from fifteen minutes to an hour to secure a number of dramatic negatives. The three major pictures of the sculpture against the nocturnal landscape taken at 11 p.m., midnight, and 4 a.m. form a temporal series.

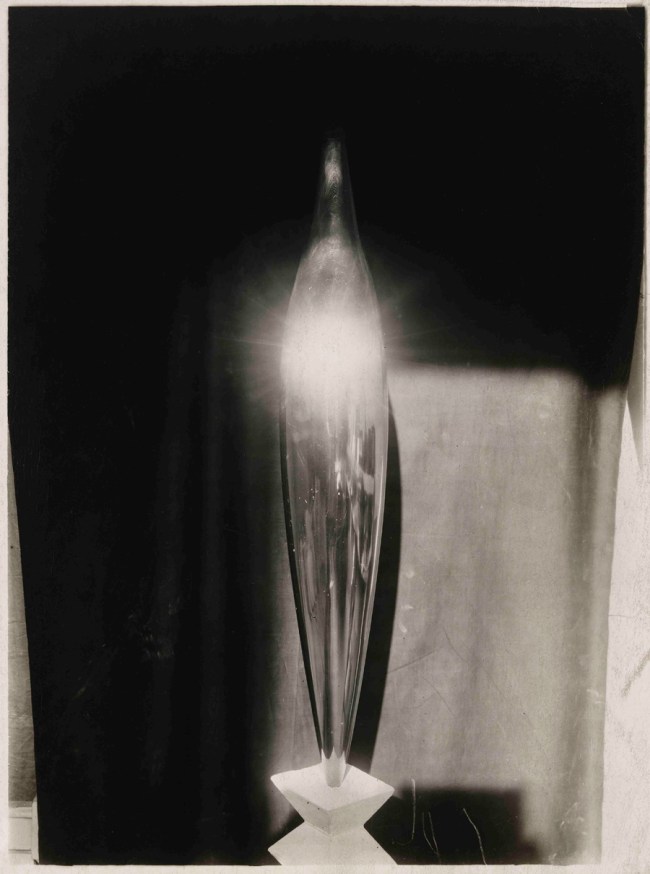

Constantin Brancusi

The Studio as Groupe Mobile

“Why write?” Brancusi once queried. “Why not just show the photographs?” The sculptor included many great photographers among his friends – Edward Steichen was one of his early champions in the United States; Alfred Stieglitz organised in 1914 his first solo exhibition in New York; Man Ray helped him buy photographic equipment; Berenice Abbott studied sculpture under him; and he was on close terms with Brassaï, André Kertész, and László Moholy-Nagy. Yet he declined to have his work photographed by others, preferring instead to take, develop, and print his own pictures.

Pushing photography against its grain, Brancusi developed an aesthetic antithetical to the usual photographic standards. His so-called photos radieuses (radiant photos) are characterised by flashes of light that explode the sculptural gestalt. In search of transparency, kineticism, and infinity, Brancusi used photography and polishing techniques to dematerialise the static, monolithic materiality of traditional sculpture, visualising what Moholy-Nagy called “the new culture of light.”

Brancusi’s pictures of his studio underscore his scenographic approach. The artist articulated the studio around hybrid, transitory configurations known as groupes mobiles (mobile groups), each comprising several pieces of sculpture, bases, and pedestals grouped in proximity. Assembling and reassembling his sculptures for the camera, Brancusi used photography as a diary of his sculptural permutations. If, as it is often said, Brancusi “invented” modern sculpture, his use of photography belongs to a reevaluation of sculpture’s modernity.

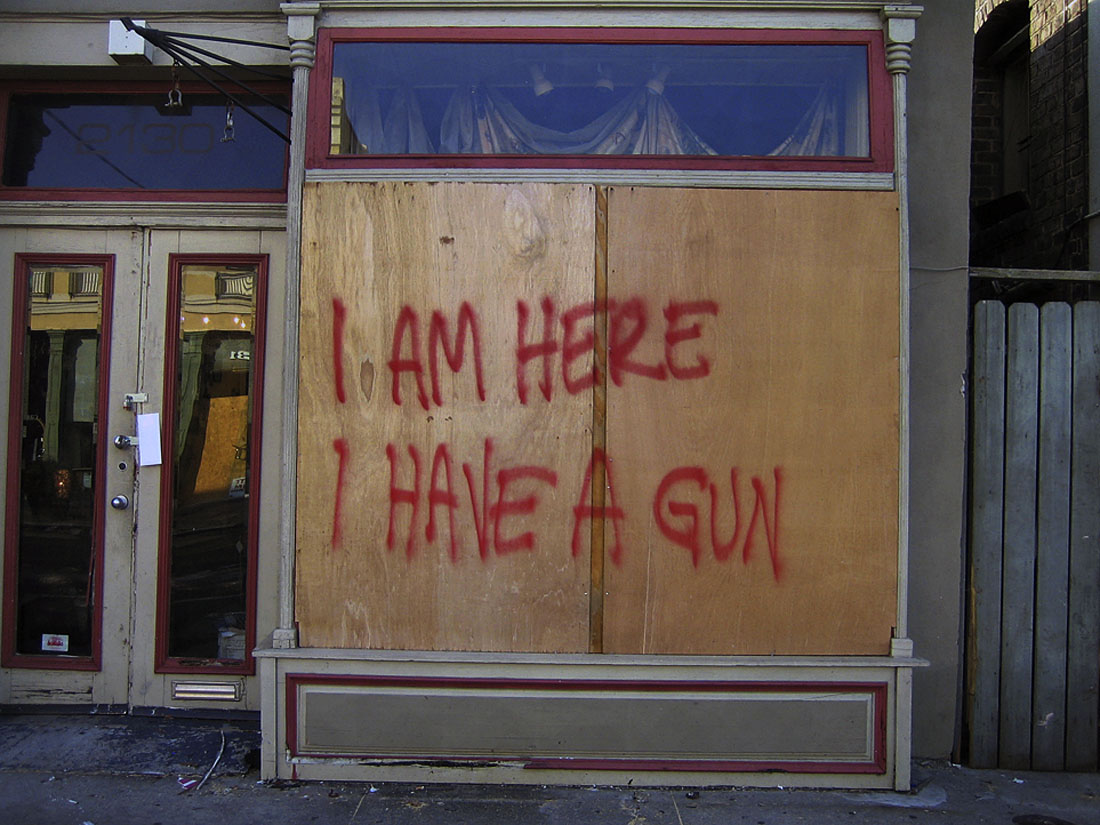

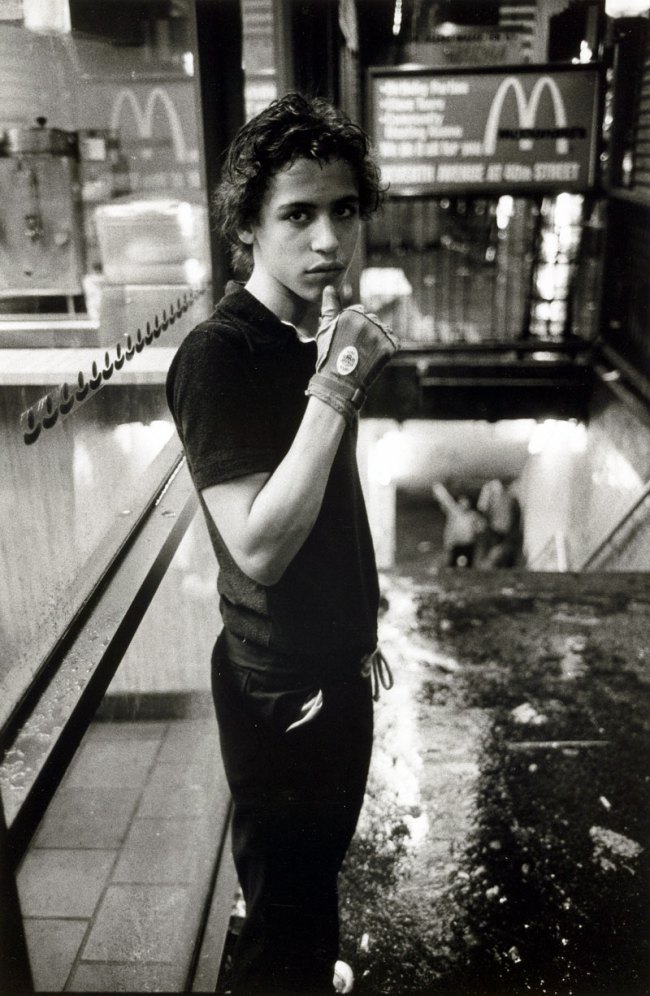

Cultural and Political Icons

How do we remember the past? What role do photographs play in mediating history and memory? In an era resonating with the consequences of two world wars, the construction and then dismantling of the Berlin Wall, the Vietnam War, and the after effects of the colonialist legacy in South Africa, commemoration has provided a rich subject for photographic investigation.

Some of the most significant photographic essays of the twentieth century – Walker Evans’s American Photographs (1938), Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958), Lee Friedlander’s The American Monument (1976), and David Goldblatt’s The Structure of Things Then (1998) – articulate to different degrees the particular value of photography as a means of defining the cultural and political role of monuments.

Evans’s emblematic image of a crushed Ionic column made of cheap sheet metal; Frank’s picture of a statue of St. Francis preaching, cross and Bible in hands, to the bleak vista of a gas station; Friedlander’s photograph of World War I hero Father Duffy, engulfed in the cacophony of Times Square’s billboards and neon, which threaten to jeopardise the sculpture’s patriotic message; and Goldblatt’s pictures of monuments to some of the most potent symbols of Afrikaner triumphalism – all take a critical look at the world that public statues inhabit.

The Studio without Walls

Sculpture in the Expanded Field

In the late 1960s a radical aesthetic change altered both the definition of the sculptural object and the ways in which that object was experienced. A number of artists who did not consider themselves photographers in the traditional sense began using the camera to rework the idea of what sculpture is, dispensing with the immobile object in favour of an altered site: the built environment, the remote landscape, or the studio or museum space in which the artist intervened.

This engagement with site and architecture – undoubtedly a function of early critiques of art’s institutional status – meant that sculpture no longer had to be a permanent three-dimensional object; it could, for instance, be a configuration of debris on the studio floor, a dematerialised vapour released into the landscape, a dissected home reconfigured as gravity-defying walk-through sculpture, or a wrapped-up building. Bruce Nauman, Robert Barry, Gordon Matta-Clark, and Christo respectively, as well as Michael Heizer, Richard Long, Dennis Oppenheim, and Robert Smithson made extensive use of photography, collecting and taking hundreds of pictures as raw material for other pieces, such as collages and photomontages.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, artists such as Zhang Dali, Cyprien Gaillard, and Rachel Whiteread have continued this dialogue through photographs contemplating examples of architecture and sculpture in states of dilapidation and entropy, remnants of a society in demise.

Daguerre’s Soup

What Is Sculpture?

In 1932, Brassaï challenged the established notions of what is or is not sculpture when he photographed a series of found objects – tiny castoff scraps of paper that had been unconsciously rolled, folded, or twisted by restless hands, strangely shaped bits of bread, smudged pieces of soap, and accidental blobs of toothpaste, which he titled Involuntary Sculptures. In the 1960s and ’70s artists engaging with various forms of reproduction, replication, and repetition used the camera to explore the limits of sculpture. The word “sculpture” itself was somewhat modified, no longer signifying something specific but rather indicating a polymorphous objecthood. For instance, in 1971 Alina Szapocznikow produced Photosculptures, pictures of a new kind of sculptural object made of stretched, formless and distended pieces of chewing gum.

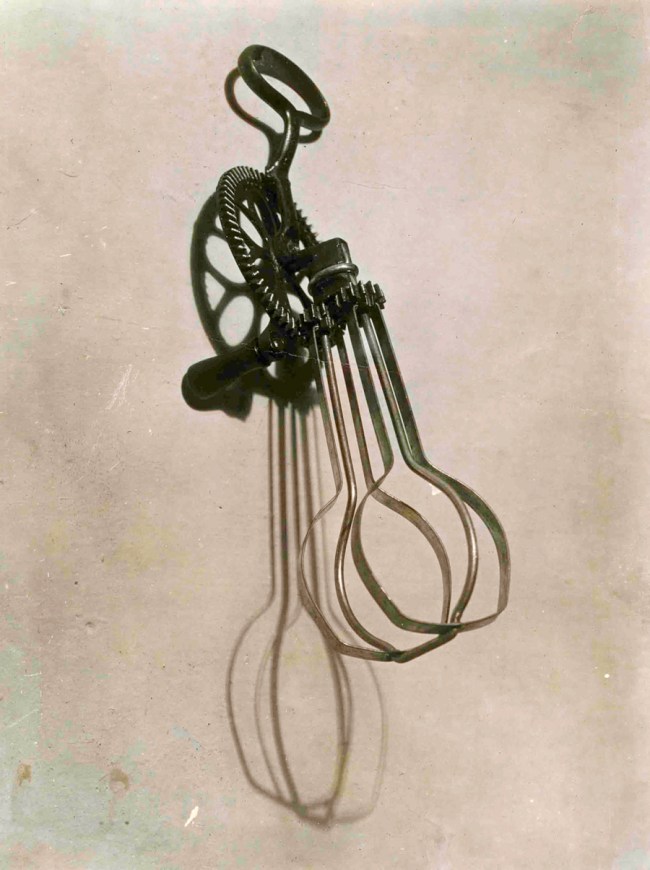

At the same time, Marcel Broodthaers concocted absurdist taxonomies in photographic works. In Daguerre’s Soup (1975), Broothaers hinted at the various fluids and chemical processes used by Louis Daguerre to invent photography in the nineteenth century by bringing into play experimental ideas about language and the realm of everyday objects. A decade later, the duo Fischli/Weiss combined photography with wacky, ingeniously choreographed assemblages of objects. Their tongue-in-cheek pictures of assemblages shot on the verge of collapse convey a sense of animated suspension and deadpan comedy.

In 2007, Rachel Harrison drew on Broodthaers’s illogical systems of classification and parodic collections of objects to produce Voyage of the Beagle, a series of pictures that collectively raise the question “What is sculpture?” Ranging from images of prehistoric standing stones to mass-produced Pop mannequins, and from topiaries to sculptures made by modernist masters, Harrison’s work constitutes an oblique quest for the origins and contemporary manifestations of sculpture.

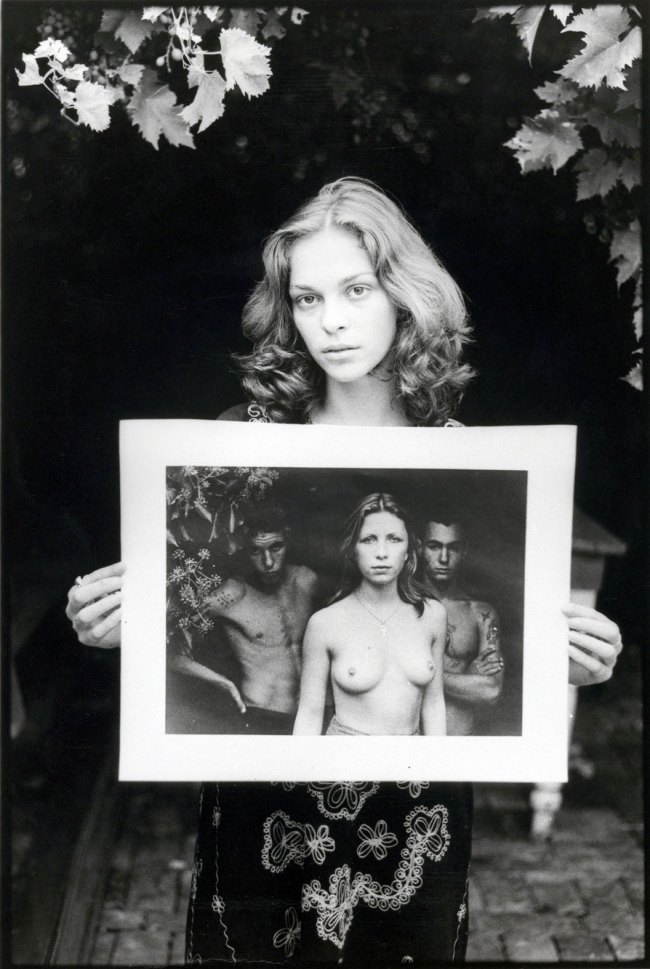

The Pygmalion Complex

Animate and Inanimate Figures

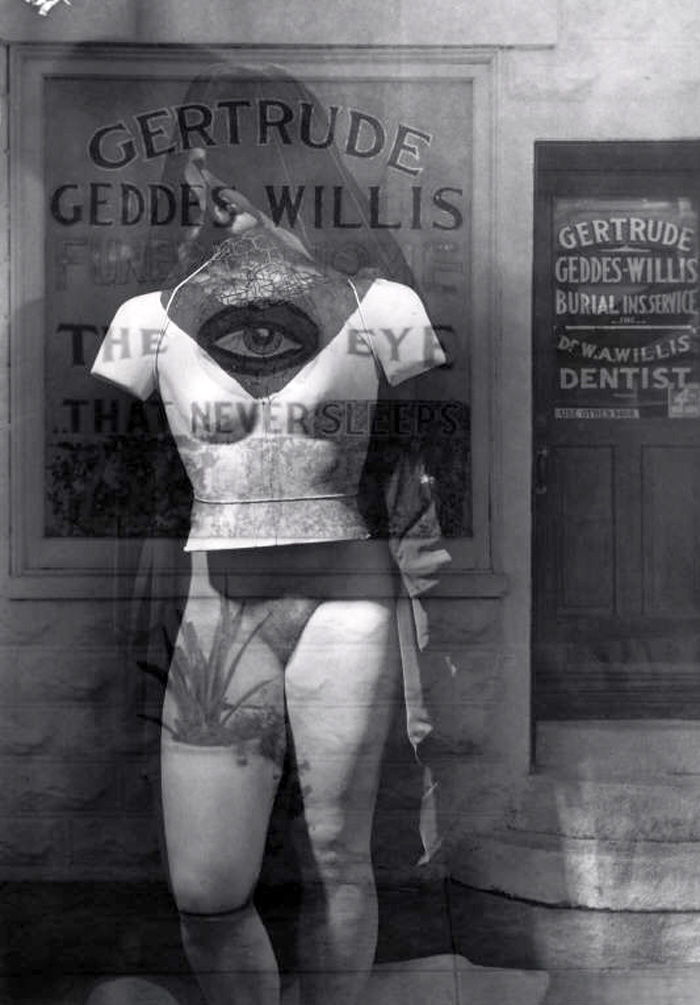

The subject of the animated statue spans the history of avant-garde photography. Artists interested in Surrealist tactics used the camera to tap the uncanniness of puppets, wax dummies, mannequins, and automata, producing pictures that both transcribe and alter appearances. Laura Gilpin explored this perturbing mix of stillness and living, alluring lifelikeness in her mysterious portrait George William Eggers (1926), in which Eggers, the director of the Denver Art Museum, keeps company with a fifteenth-century bust whose polychrome charm is enhanced by the glow of the candle he holds next to her face. So does Edward Weston, in his whimsical Rubber Dummies, Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studios, Hollywood (1939), showing two elastic dolls caught in a pas de deux on a movie-studio storage lot; and Clarence John Laughlin, in his eerie photomontage The Eye That Never Sleeps (1946), in which the negative of an image taken in a New Orleans funeral parlour has been overlaid with an image of a mannequin – one of whose legs, however, is that of a flesh-and-blood model.

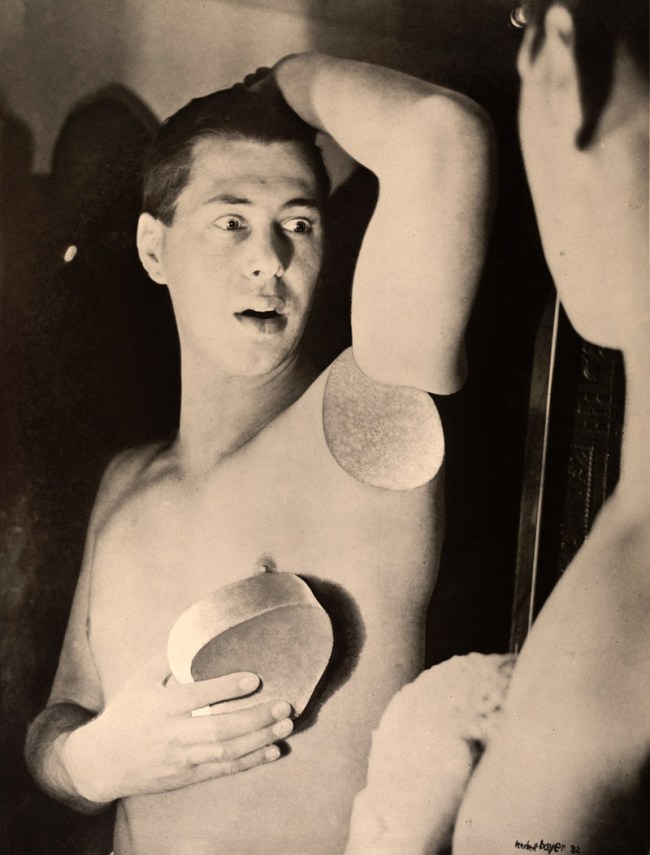

The tension between animate object and inanimate female form lies at the crux of many of Man Ray’s photographs, including Black and White (1926), which provocatively couples the head of the legendary model, artist, and cabaret singer Alice Prin, a.k.a. Kiki of Montparnasse, with an African ceremonial mask. Hans Bellmer’s photographs of dismembered dolls, and the critical photomontages of Herbert Bayer, Hannah Höch, and Johannes Theodor Baargeld, probe the relationship between living figure and sculpture by invoking the unstable subjectivity and breakdown of anatomic boundaries in the aftermath of the Great War.

The Performing Body as Sculptural Object

In 1969, Gilbert & George covered their heads and hands in metallic powders to sing Flanagan and Allen’s vaudeville number “Underneath the Arches” in live performance. Declaring themselves living sculptures, they claimed the status of an artwork, a role they used photography to express. Charles Ray and Dennis Oppenheim, placing a premium on their training as sculptors, articulated the body as a prop that could be picked up, bent, or deployed instead of more traditional materials as a system of weight, mass, and balance.

In the radicalised climate of the 1970s, artists such as Eleanor Antin, Ana Mendieta, VALIE EXPORT, and Hannah Wilke engaged with the “rhetoric of the pose,” underscoring the key role of photography in the intersection of performance, sculpture and portraiture.

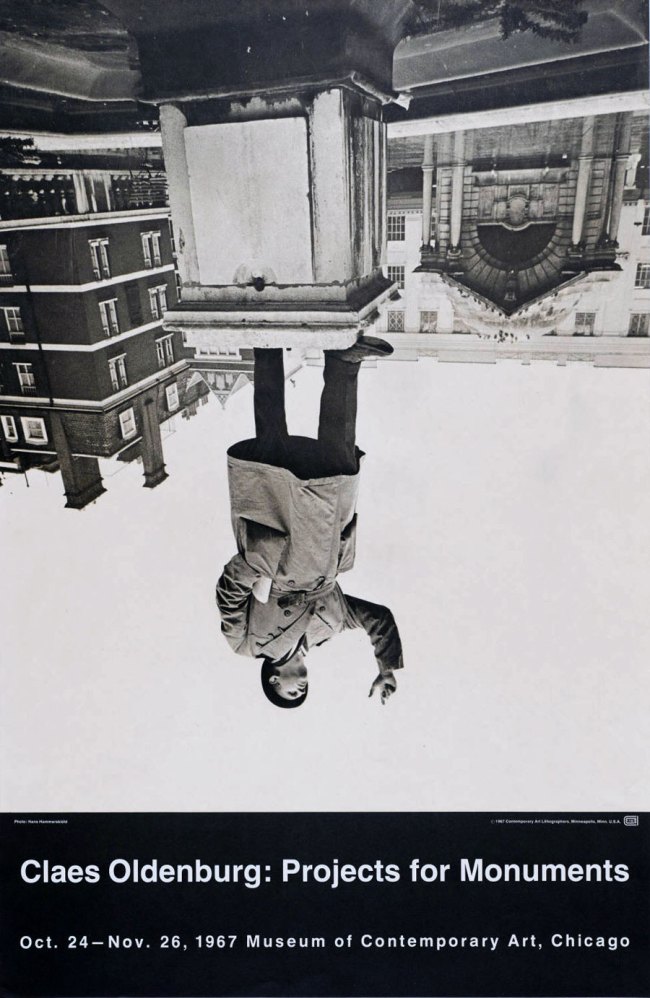

Other artists as diverse as Robert Morris, Claes Oldenburg, Otto Muehl, Bas Jan Ader, and Bruce Nauman, experimented with the plasticity of the body as sculptural material. Several of Nauman’s pictures from his portfolio Eleven Color Photographs (1966-1967 / 1970) spoof the classic tradition of sculpture. Yet the signature image of the group – Self-Portrait as a Fountain, in which a stripped-to-the-waist Nauman spews water from his mouth like a medieval gargoyle – is a deadpan salute to Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917). In this spirit, Erwin Wurm’s series of One Minute Sculptures (1997-98) evoke gestural articulations in which the artist’s body is turned into a sculptural form. Wurm, like the other artists presented in this exhibition, focuses attention on what one can do with and through photography, using the camera not to document actions that precede the impulse to record them but as an agency that itself generates actions through its own presence.

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905-1985)

The Eye That Never Sleeps

1946

Gelatin silver print

12 3/8 x 8 3/4″ (31.4 x 22.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase

© Clarence John Laughlin

Fischli/Weiss (Peter Fischli. Swiss, b. 1952. David Weiss. Swiss, b. 1946)

Outlaws

1984

Chromogenic colour print

15 ¾ x 11 13/16″ (40 x 30cm)

Courtesy the artists and Matthew Marks Gallery, New York

© Peter Fischli and David Weiss. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York

Claes Oldenburg (American born Sweden. b. 1929)

Claes Oldenburg: Projects for Monuments

1967

Offset lithograph

34 11/16 x 22 1/2″ (88.0 x 57.2 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Barbara Pine

© 2010 Claes Oldenburg

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky) (American, 1890-1976)

L’Homme (Man)

1918

Gelatin silver print

19 x 14 1/2″ (48.3 x 36.8cm)

Private collection, New York

© 2010 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Herbert Bayer (American born Austria, 1900-1985)

Humanly impossible

1932

Gelatin silver print

15 3/8 x 11 9/16″ (39 x 29.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Purchase

© 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Constantin Brancusi (French born Romania, 1876-1957)

L’Oiseau (Golden Bird)

c. 1919

Gelatin silver print

9 x 6 11/16″ (22.8 x 17cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Purchase

© 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Gillian Wearing (British, b. 1963)

Self-Portrait at 17 Years Old

2003

Chromogenic color print

41 x 32″ (104.1 x 81.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of The Contemporary Arts Council of The Museum of Modern Art

© 2010 Gillian Wearing. Courtesy the artist, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, and Maureen Paley, London

Johannes Theodor Baargeld (Alfred Emanuel Ferdinand Gruenwald) (German, 1892-1927)

Typische Vertikalklitterung als Darstellung des Dada Baargeld (Typical vertical mess as depiction of the Dada Baargeld)

1920

Photomontage

14 5/8 x 12 3/16″ (37.1 x 31cm)

Kunsthaus Zürich, Grafische Sammlung

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

Father Duffy, Times Square

April 14, 1937

Gelatin silver print

9 5/16 x 7 5/8″ (23.7 x 19.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Ronald A. Kurtz

© 2010 Berenice Abbott/Commerce Graphics, Ltd., New York

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

11, West Fifty-Third Street, New York

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5.30pm

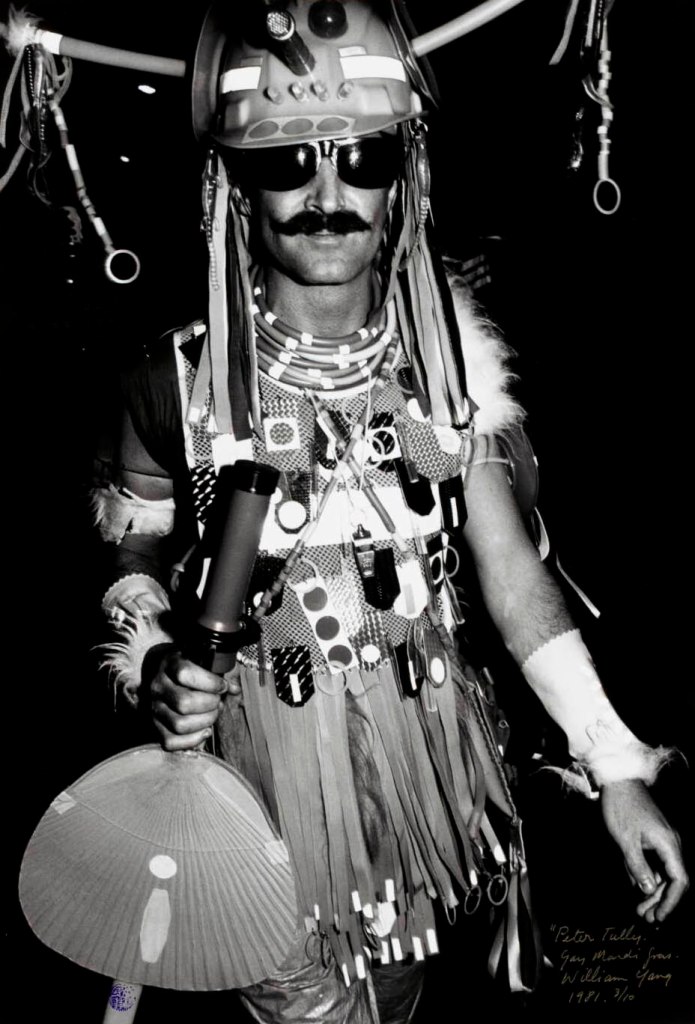

![Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Head of Man with Hat and Cigar]' c. 1960 from the exhibition 'Hipsters, Hustlers, and Handball Players: Leon Levinstein's New York Photographs, 1950-1980' at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, June - October, 2010 Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Head of Man with Hat and Cigar]' c. 1960 from the exhibition 'Hipsters, Hustlers, and Handball Players: Leon Levinstein's New York Photographs, 1950-1980' at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, June - October, 2010](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/leon-levinstein-head-of-man-with-hat-and-cigar.jpg)

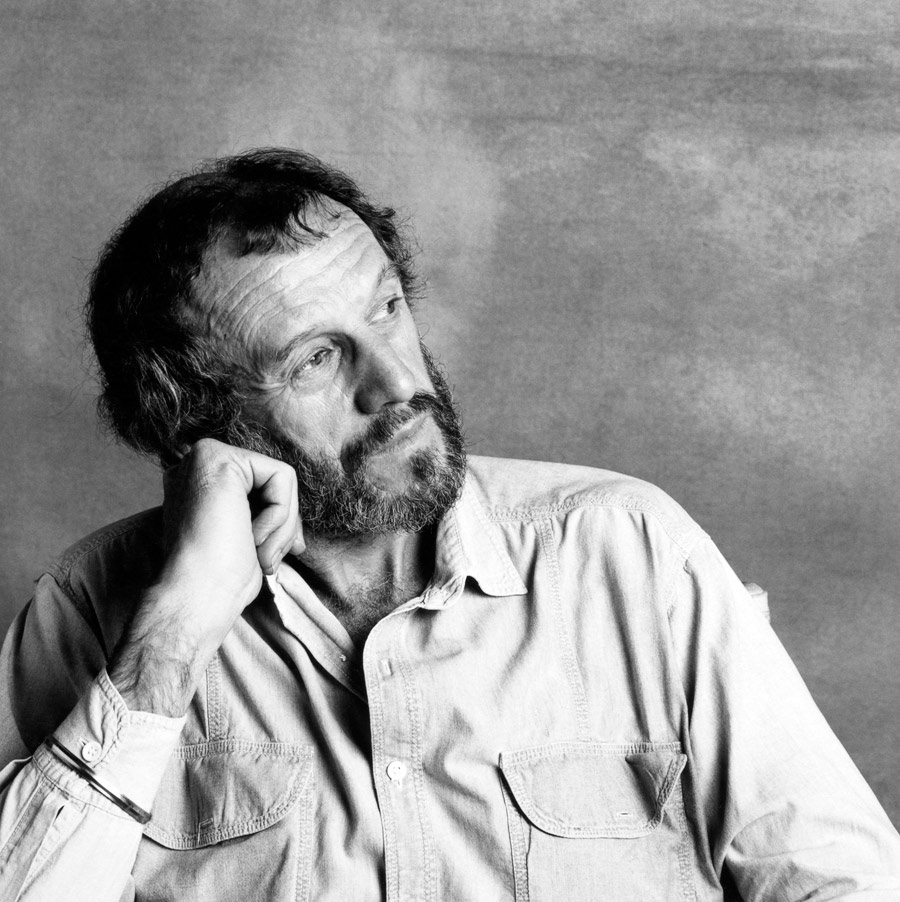

![Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Beach Scene: Woman Wearing Paper Bag Hat, Coney Island, New York]' 1950s Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Beach Scene: Woman Wearing Paper Bag Hat, Coney Island, New York]' 1950s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/leon-levinstein-beach-scene.jpg?w=809)

You must be logged in to post a comment.