Exhibition dates: 13th March – 28th September, 2025

Curator: Patricia Sorroche, Head of Exhibitions at the Museu Tàpies

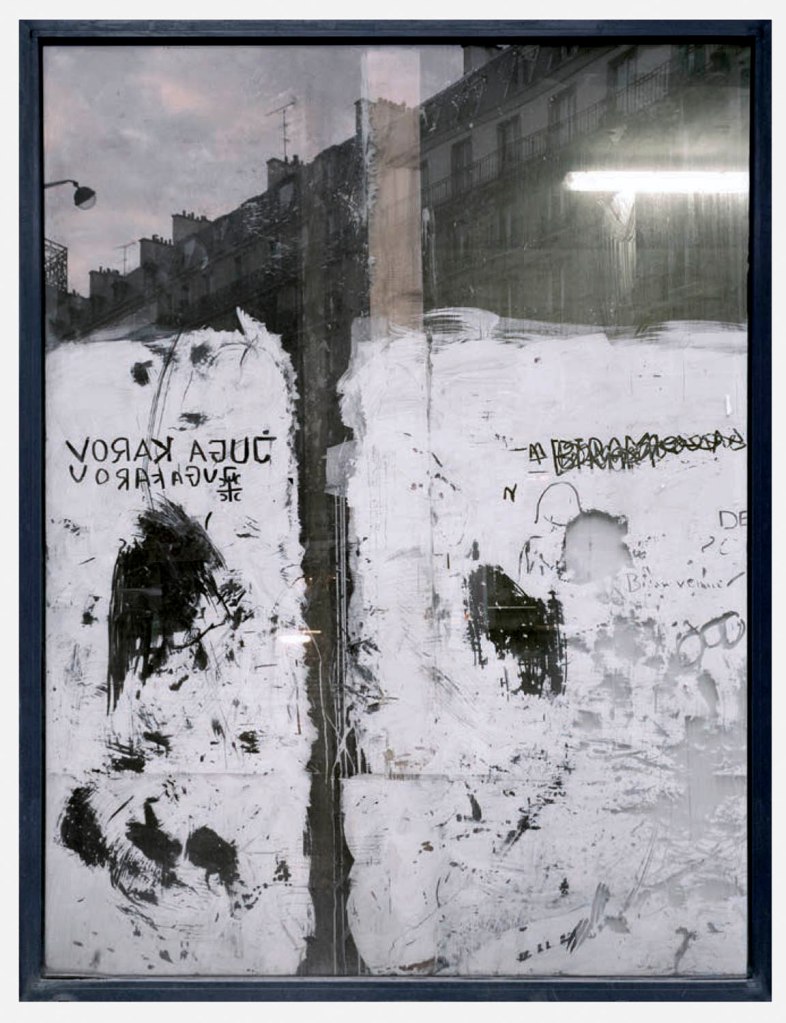

Anna Malagrida (Spanish, b. 1970)

Rue de Charenton

2008-2009

Photographic print on Dibond

Contradicting the hobgoblin of little minds

I love the conceptualisation of these photographs: interstitial spaces of the city, liminal spaces that ‘stand between’ one place and another.1

I love the abstract nature of these photographs, abstract paintings of the city which occlude symbols and signs, capture traces and gestures, where nothing is fixed and everything is fluid, up for interpretation through the imagination.

Unfortunately, the digital online reproductions make the spaces seem very flat and one-dimensional, in a liminal and spiritual sense.

I would have loved to have stood in the gallery to breathe in the presences of the photographs, their energy and spirit. Would they have held me? Is there enough for me to hang my hat on? Would they have reverberated in my soul. I don’t know. I can’t feel them through the digital reproductions.

I think of sitting in front of Monet’s massive curved paintings of Water Lillies at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris and being surrounded by these beautiful, shifting, elemental / alchemical abstract works of art. And being spell bound.

How would I feel surrounded by these representations, surfaces, depths of the city, these whitewashed absences (with all the connotations of race, power, money, and coverups that the name implies) that proffer different ways of seeing the world, places of the visible and the invisible.

“Her work forces us to confront our social and political condition of being, but from a poetic, liminal space, where contradiction is a symbol of the dualities of the human condition in the postmodern world.”2

Contradiction is NEVER a symbol for that would mean contradiction becomes a conventional representation of an object, function, or process. And the human condition in the postmodern world is far more than a duality … it is an intertextual multiplicity of points of view and nexus (the nexus between industry and political power, the nexus between business and government, the nexus between public space and private space, etc…)

“Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

~ Walt Whitman from Leaves of Grass

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ A liminal space is a transitional place or state, like a hallway or adolescence, that is “in-between” two distinct stages or locations, creating a sense of unease or disorientation. The word comes from the Latin for “threshold,” and these spaces, often devoid of people and eerily familiar yet subtly wrong, can evoke feelings of nostalgia, anxiety, and the potential for creativity or personal growth during periods of uncertainty.

AI summary from Google

2/ Patricia Sorroche. Anna Malagrida. (Trans)gazes of the sensible. Curatorial statement, 2025

Many thankx to Colin Vickery for alerting me to this exhibition. Many thankx to Museu Tàpies for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I’m interested in the intuited spaces on the other side, what isn’t in the image, but is imagined. What lies beyond, outside the frame, is the place that activates the imagination, inventing a story or imagining a space. The things we intuit, which are on the other side, belong to the story or to the space itself. Through the metaphor of the window, I’m trying to create a space of in-betweenness and uncertainty.”

Anna Malagrida in Álvaro de la Rica, “Las fronteras transparentes. A propósito de las fotos de Anna Malagrida,” published in Revisiones, No. 7, 2011, p. 129.

Opacitas: Veiling Transparency takes us on a journey through the work of Anna Malagrida (Barcelona, 1970) and presents a project that explores photography, video and installation. Her gaze focuses on the liminal spaces that unite and separate, bringing opposites into conversation.

Malagrida mainly situates us in the city and in a few constructed natural spaces. Through a play of perspectives, from the interior to the exterior and vice versa, her photographs and video installations become windows that reveal and conceal the tensions that run through society. Her polysemic gaze escapes a univocal interpretation of images in order to inhabit certain entropic spaces that she invites us to discover through her work.

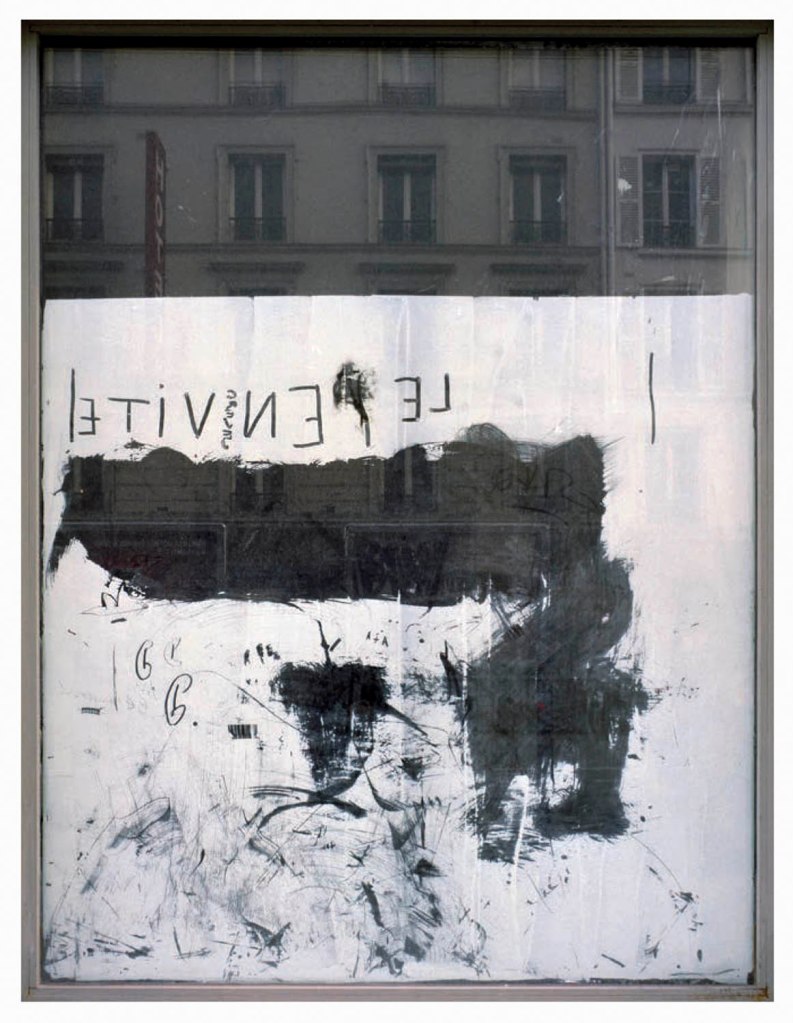

Malagrida’s images capture the remnants and the infralight traces, indexes, signs that refer to previous moments, social tensions or simple anonymous gestures. The visual ambiguity in her work is revealed through the texture of her images, which evoke pictorial references and dissolve the limits between appearance and reality. Images of closed shop windows painted with characteristic whitewash, an opaque veil that prevents us from looking inside and transforms these spaces into abstract surfaces, resembling large pictorial canvases. Poetic actions operate in her works with a multiplicity of meanings: the painter’s gesture is also that of the working body, and the city and the landscape are revealed from within. Said gestures are erased, cleansed or simply fixed by the passage of time, cyclical and mutable.

Her work, which transcends photography and painting, immerses the viewer in a visual experience with multiple meanings and invites them to look at the city and natural surroundings from a new perspective, one that reveals the vestiges of a landscape affected by social and economic change. Her practice is a space for reflecting on vulnerability, resistance and the possibility of reconstruction, both of the individual and the environment they inhabit.

Text from the Museu Tàpies website

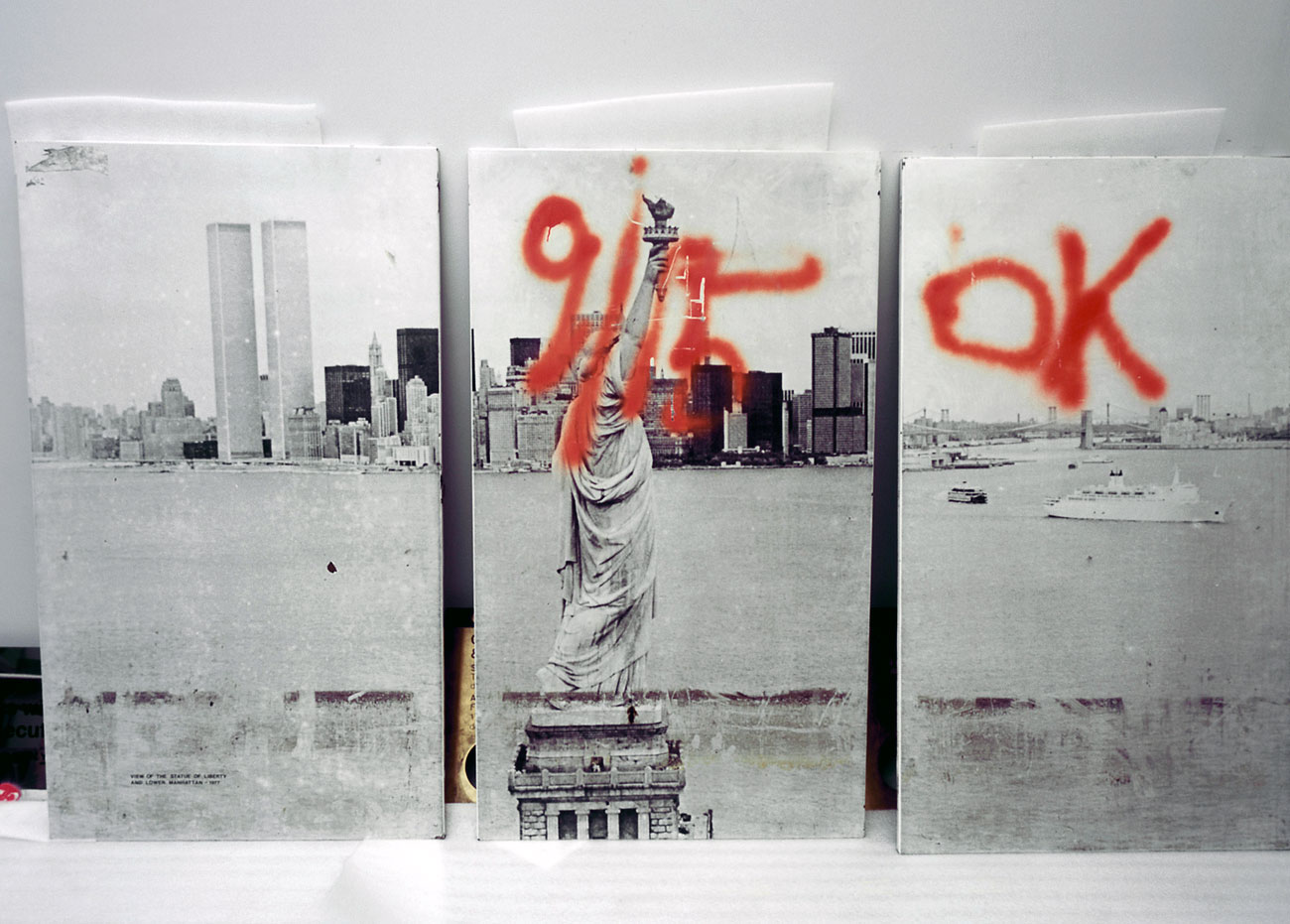

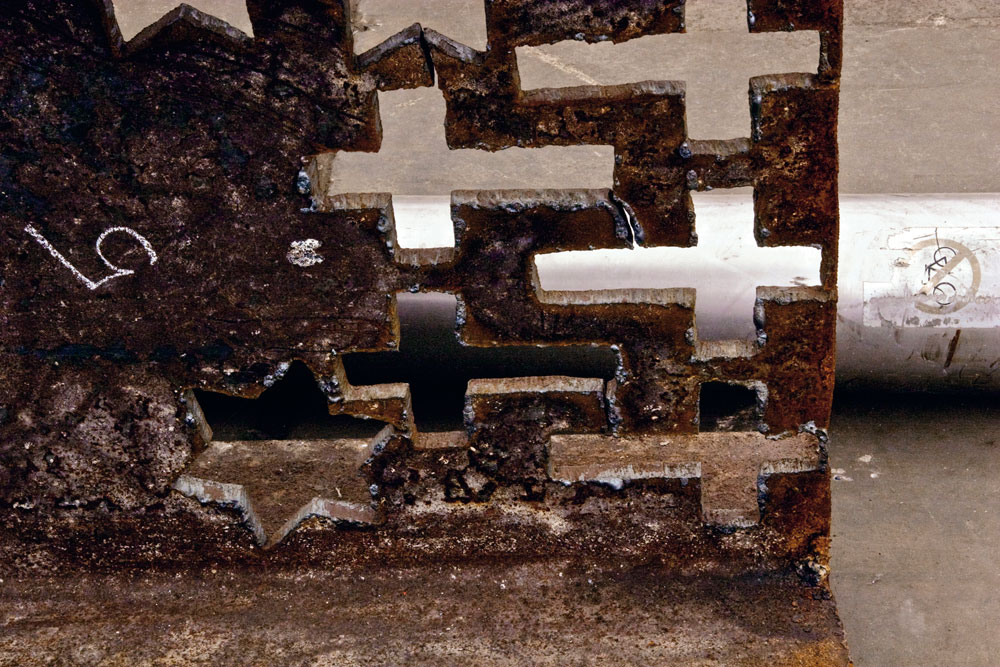

Installation views of the exhibition Anna Malagrida. Opacitas: Veiling Transparency at Museu Tàpies, Barcelona, March – September, 2025

Installation view of the exhibition Anna Malagrida. Opacitas: Veiling Transparency at Museu Tàpies, Barcelona, March – September, 2025 showing La laveur du carreau 2010 (video still)

The Museu Tàpies presents Anna Malagrida’s exhibition Opacitas. Veiling Transparency. Curated by Patricia Sorroche, Head of Exhibitions at the Museu Tàpies, the exhibition offers a survey of the artist’s work through photography, video and installation.

This exhibition provides an opportunity to see, for the first time in Barcelona, the work of this artist, who was born in the city, but has spent most of her career in France.

Anna Malagrida’s project responds to the Museu Tàpies’ current aim of enabling discourses that institutions have left out and that have not found a space for representation in our most immediate reality.

Anna Malagrida (Barcelona, 1970) works with photography to navigate between that which is public and private, based on a play of perspectives and visions that shuns the realistic image to draw us into a game of collective imaginaries. The idea of the city and its significance as a social agent are present in her photographs, which function as archaeological vestiges of the social crises of contemporary city life.

The exhibition Opacitas. Veiling Transparency, curated by Patricia Sorroche, Head of Exhibitions at the Museu Tàpies, offers a survey of Anna Malagrida’s work through projects that explore photography, video and installation. Focusing on the liminal spaces that unite and separate, her gaze brings opposites into conversation.

Malagrida mainly situates us in the city and in a few constructed natural spaces. Through a play of perspectives, from the interior to the exterior and vice versa, her photographs and video installations become windows that reveal and conceal the tensions that run through society. Her gaze escapes a univocal interpretation of images, in order to inhabit certain spaces that she invites us to discover through her work.

Her images capture remnants and traces, signs that refer to previous moments, social tensions or simple anonymous gestures. The visual ambiguity in her work is revealed through the texture of her photographs and videos, which evoke pictorial references and dissolve the limits between appearance and reality. This can be seen, for example, in the images of closed shop windows painted with characteristic whitewash, an opaque veil that prevents us from looking inside and transforms these spaces into abstract surfaces, resembling large pictorial canvases. Poetic actions operate in her works with a multiplicity of meanings: the painter’s gesture is also that of the working body, and the city and the landscape are revealed from within. These gestures are erased, cleaned or simply fixed by the passage of time, cyclical and mutable.

Malagrida’s work, which transcends photography and painting, immerses the spectator in a visual experience with multiple meanings and invites us to look at the city and natural surroundings from a new perspective, one that reveals the vestiges of a landscape affected by social and economic change. Her practice is a space for reflecting on vulnerability, resistance and the possibility of reconstruction, both of the individual and the environment they inhabit.

The exhibition Opacitas. Veiling Transparency allows visitors to explore and delve into Anna Malagrida’s career through a selection of her works. The itinerary of the exhibition begins with the piece Vitrines (Shop Windows, 2008-2009), in which the artist photographs the windows of shops on the streets of Paris that had to close down due to the economic crisis and concealed their interiors by coating their windows with whitewash. The exercise of gazing through shop windows is also present in Le laveur du carreau (The Window Cleaner, 2010), an audiovisual piece that allows us to observe how a worker lathers and cleans the windows, in a visual play between opacity and transparency that also situates us in the intermediate zones.

In Danza de mujer (Woman Dance, 2017), filmed in the Jordanian desert, ‘Malagrida puts into question, through the movement of the veil, certain social policies in relation to specific groups, and how narrow perspectives promote ways of seeing the world that exclude a large part of it,’ in the words of the exhibition’s curator, Patricia Sorroche. Finally, Point de vue (2006), produced in the architectural complex that housed the Club Med tourist resort inaugurated in 1962 in the protected natural area of Cap de Creus, presents the traces of the economic systems that defied sustainability.

Sorroche concludes that ‘operating through opposites, through the decategorisation of traditional forms of representation and the overlapping of different languages, makes Anna Malagrida’s work move between textures, between the places of the visible and the invisible, to immerse us in a dialogue of opposites’. And she continues: ‘Her work multiplies our gazes, our ways of seeing the world, making it more porous, while at the same time enabling other ways of understanding, transmuting and transcending it. Her work forces us to confront our social and political condition of being, but from a poetic, liminal place, where contradiction is a symbol of the dualities of the human condition in a post-modern world. A space where we can come together to understand each other in possible societies of the common, based on a collective and communal view.’

The project Anna Malagrida. Opacitas. Veiling Transparency is completed with an exhibition booklet featuring texts by the curator and by art critic Marta Gili, as well as an interview with the artist. Malagrida and Gili will take part in the inaugural conversation of the exhibition, on 13 March at 6 pm, in an event that forms part of the project’s public programme, along with the talk by Morena Hanbury. Over the next few months, the Museu Tàpies’ Education Department will be offering a programme of tours and activities for all audiences.

Press release from Museu Tàpies

Anna Malagrida (Spanish, b. 1970)

Rue Laffitte I

2008-2009

Photographic print on Dibond

Anna Malagrida (Spanish, b. 1970)

Rue Laffitte II

2008-2009

Photographic print on Dibond

Anna Malagrida (Spanish, b. 1970)

Vitrines. Boulevard Sébastopol. Aparadors. Boulevard Sébastopol

2008-2009

Photographic print on Dibond

Curatorial statement

Anna Malagrida. (Trans)gazes of the sensible

Patricia Sorroche

“Photography is, above all, a way of looking, it is not the same look. It is a way of seeing that has become conscious of itself, that has become reflexive.”

~ Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977

What happens when we place ourselves in that intermediate space where the visible and the invisible intertwine? Anna Malagrida invites us to explore this question by delving into the dichotomy of opposites in her work, and by directing our gaze toward the space in-between, where our way of looking is amplified, expanded and transformed, blurring the boundaries between the perceptible and the imperceptible. Revisiting some of Malagrida’s works opens a path, a transmutation of our bodies and our drives as we move around her pieces. Like palimpsests, her works hold layers of memory for us to rewrite. Time, memory and narrative intertwine to confront us with a new perspective from which to observe the world.

Opacitas. Veiling Transparency takes as its starting point an apriorism where the poetic gesture reveals the political gesture. When Jacques Rancière speaks of the ‘distribution of the sensible’, what he offers us is the possibility of the gesture to modify and transform what is seen, felt or said within a society from a poetic space. Along the same lines, Martha Rosler maintains that poetry and art are spaces of resistance, as well as political and social reconfiguration. Based on this axiom, we can understand Malagrida’s photographs and works as a space where the poetic and the political intersect in a subtlety of visual nuances, allowing us to recodify ways of inhabiting space and time.

The journey begins with a hypallage, where the city is transformed into a text that is written and rewritten as we move forward. An accumulation of memories and desires, where each street, each wall, seems to tell a story waiting to be read. In the series Vitrines (Shop Windows, 2008-09), the city is highlighted as a place of tension, wherein Malagrida works on ‘the epidermal space of the city’.1 The financial crisis that devastated the economies of a global north during the early twenty-first century led to the bankruptcy of many businesses. The artist photographed and immortalised the shop windows of Parisian businesses forced to close as a consequence of the economic collapse. To conceal the view, the windows were painted or whitewashed, veiling the interior, creating absences. The photographs of these places, now hidden from view, place the postmodern subject in a liminal space, where the gaze is para-actional: we cannot see, but we can reinterpret the void. Here, the painted and erased surfaces invite us to draw upon the unconscious in order to activate these new visual paraphrases. Walking through those streets highlights the fragilities of being, the contemporary narratives marked by the strong tensions of a system alien to our daily lives.

An enormous pile of rubble in the middle of the gallery prevents the body from moving freely through the space. A ruin activated to challenge us directly, to make us reflect and think about our condition. It questions what remains as a memory of a past that projects us into the future; and it questions a present, as Andreas Huyssen recounted.2 In this way, the ruin takes on a double dimension: both of a past with its scars and wounds, and of a future that is being built, which rises and walks, opening up as a space that enables a society continually emerging and re-emerging.

Continuing with the idea of opposites and dualities, our path takes us to the next space, more intimate, more enclosed, darker. As if we were entering a camera obscura or a lens shutter, the viewer is immersed in darkness; but this is a darkness that reveals a transparency, opening windows and walls to the outside, and placing us in the active condition of looking out.

Danza de mujer (Woman Dance, 2007) invites us to enter into an experience where the body is exposed in its fragile condition, ‘reincorporating a sensitive look at that dialectical movement that, in part, the photographic device itself already deploys without imposing a reification of the world’.3 From a subtle artefact transporting us to a refuge in the Jordanian desert, a veil is swayed by the breeze entering through a small window. This simple poetic action condenses part of the characteristic axioms of Malagrida’s works. The darkness of the refuge, with the light filtering from the desert outside, the black veil fluttering synchronously and asynchronously. These opposites operate with determination, reminding us that what prevents us from looking transparently limits our ways of interpreting and thinking about the world.

The piece was made at a time of tension, when in France the veil was banned in all public places, and thus, Arab women were rendered invisible and blurred in a system that did not recognise the singularities of certain communities. Through the dance of the veil, Malagrida questions and puts into crisis the politics of the social in relation to certain specific groups, and how these narrow visions propose ways of seeing the world while excluding an important part of it.

From the symbolic and the poetic, Malagrida’s work opens up to the post-human condition of being, understood as a relational and concentric existence with its environment and communities. To understand this relational condition, Édouard Glissant referred to the poetics of relation, where the idea of time is cyclical, and societies can only be conceived in a structure of continuous relationships.

Another work encountered by the viewer is Le laveur de carreau (The Window Cleaner, 2010), where Malagrida draws a ‘parallel between the gesture of a sublimated painter and that of a worker carrying out an entrusted task’.4 Here, the idea permeating the artist’s work is established: the gesture becomes the subject of the action, the idea of genius as addressed by Walter Benjamin is made evident. The cleaner is a metaphor for the painter, who becomes blurred in his condition as a worker, in his social condition of being. In this video work, we find ourselves looking from inside a shop, while a worker lathers the window and then proceeds to remove the remains of water and soap with a squeegee. From the passive condition of the onlooker, we attend to the action happening before our eyes. In this way, we witness the moment of creation and also of destruction. The soapy water our cleaner spreads over the glass surface is a metonymy of the act of painting; a fleeting work, which disappearing shortly after, returns to the transparency of glass. As in previous works, Malagrida again operates from opposites, from the concepts of opacity and transparency. Just for an instant, she places us in an intermediate place, just as Marcel Broodthaers did in some of his most renowned films (for instance, in Abb. 1. Projection d’un film du Musée d’Art Moderne, 1971), where the camera was placed at the midpoint between the inside and the outside, in his case the gallery, but aiming at the same idea, at the place where art is conceived as a process in constant movement, a flow transcending the static to become transmutable.

Both the Vitrines series and Le laveur de carreau can be read as trompe l’oeil references to large Informalist canvases. As both John Berger and Antoni Tàpies remarked, art should allow us to discover the unknown, to enter into places where the tangible, the visible, cannot go. Art is the place of transformation, a place where the unknown emerges in its multiple and polysemic condition.

Although there is no set itinerary for the viewer to follow, the last of the pieces in this exhibition is Point de vue (2006), where new agents appear in dialogue with those we have encountered before. This installation was made in Cap de Creus, in the north of Catalonia, in a protected natural area, close to the border with France. Thanks to the Law of Natural Heritage and Biodiversity, after a few decades the tourist complex built here by Club Med was forced to close. Malagrida installed her camera inside this architectural complex, which remained standing as a vestige and trace of economic systems that try to evade certain norms and sustainability policies. In so doing, Malagrida returns us to the intermediate and intersectional space, since we encounter the traces people have left on the windows, full of dust and sand; scratched phrases proclaiming their condition as the poetics of social archaeology. The dust becomes a ‘residue’5 containing the possibility of the new, of what is to come, and of the passage of time.

The piece is also an allusion, a synecdoche where perspective plays a leading role. Composed of three large photographs, the piece reveals a landscape behind the dust, a perspective revealing our form of representation, whose signs are linked to society’s power and knowledge structures. A theory influenced by Erwin Panofsky,6 who studied Renaissance perspective as a structure for representing time, place and society at a certain moment in history: something which structures the worldview. In this way, perspective becomes a space for representing socio-political systems, while in the Renaissance it adopted a homogeneous, infinite and ordered character, in contrast to the medieval or Romanesque vision where space was hierarchical. The classical and orthodox perspective proposed by this work invites us to think about how the forms of representation are ways of making the world visible and reproducing it. This idea points to the manner in which the telling of history is based on a structure, on a certain perspective that determines what is to be highlighted and ignores other events or facts running counter to historical hegemonies. It is also interesting to notice how the different layers are discovered to the viewer: first the dust, then the inscriptions and finally the landscape. And how, returning to the notion of distance and horizon, by way of passing through the glass we are led to reimagine the possibilities of the outside.

In conclusion, operating from opposites, from the decategorisation of traditional forms of representation and the overlapping of different languages, makes Malagrida’s work move between textures, between places of the visible and the invisible, to immerse us in a dialogue of opposites. This dialogical premise with which we enter her works does not seek to block our view or interpretation, but rather opens up the multiplicity of discourse, of the image. Her work leads us to multiply our views, our ways of seeing the world, to make it more porous, while enabling other ways of understanding it, of transmuting it and traversing it. Her work forces us to confront our social and political condition of being, but from a poetic, liminal space, where contradiction is a symbol of the dualities of the human condition in the postmodern world. A place where we can meet and understand each other in possible societies of the common, from a collective and community-based place.

Footnotes

1/ Muriel Barthou, “Entretien à Anna Malagrida,” in L’invisible photographique ; pour une histoire de la photographie, Paris: La lettre volée, 2019.

2/ Andreas Huyssen, Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of the Memory. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003.

3/ Marta Dahó, “Espacio de la continuidad. Lugares de la intersección. Algunas notas en torno a los trabajos de Anna Malagrida,” in (In)visibilidad (ex. cat.). La Coruña: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Gas Natural Fenosa, 2016.

4/ Étienne Hat, “Entretien. Anna Malagrida,” in Anna Malagrida, Vitrines, Paris: Éditions Filigranes, 2025; Paris barricadé, Paris: Éditions Filigranes, 2025; and Los muros hablan, Paris: Éditions Filigranes, 2025. (Author’s translation.)

5/ Nicolas Bourriaud, Estética relacional. Buenos Aires: Adriana Hidalgo, 2006.

6/ Erwin Panofsky, La perspectiva como forma simbólica. Barcelona: Tusquets, 1999 (1927).

Anna Malagrida (Spanish, b. 1970)

Rue Bleue

2008-2009

Photographic print on Dibond

Anna Malagrida (Spanish, b. 1970)

Rue Lecourbe I

2008-2009

Photographic print on Dibond

Anna Malagrida (Spanish, b. 1970)

Rue Riboutté

2008-2009

Photographic print on Dibond

Anna Malagrida (Spanish, b. 1970)

Rue de Châteaudun

2008-2009

Photographic print on Dibond

Museu Tàpies

Carrer d’Aragó 255

08007 Barcelona, Catalonia (Spain)

Phone: +34 934 870 315

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Saturday 10.00am – 7.00pm

Sunday 10.00am – 3.00pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.