Exhibition dates: 9th Dec 2022 – 10th April 2023

Curator: Dr. Markus Bertsch

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882)

Helen of Troy

1863

Oil on mahogany

32.8 x 27.7cm

© Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk

Foto: Elke Walford

What a fascinating and inspired concept for an exhibition!

In order to understand the myth and construction of the femme fatale stereotype the exhibition investigates, through art and representation, concepts such as sexuality and its demonisation, the male and female gaze, white ideals of beauty, racism, Orientalism, anti-Semitism, power relations, hate, non-binary gaze, gender roles, myth and religion and black feminism. Such areas of breath are needed to examine the myth of the femme fatale.

I just wish the media images had included some photographs from the interwar avant-garde period by photographers such as Claude Cahun, Dora Maar, Eva Besnyö, Ilse Bing, Lotte Jacobi, Yva, Grete Stern, Ellen Auerbach, Aenne Biermann and Florence Henri for example – all of whom photographed the “New Woman” of the 1920s, an image which embodied an ideal of female empowerment based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art. I hope the exhibition contains images by some of these photographers.

“The femme fatale is a myth, a projection, a construction. She symbolises a visually coded female stereotype: the sensual, erotic and seductive woman whose allegedly demonic nature reveals itself in her ability to lure and enchant men – often leading to fatal results. It is this likewise dazzling and clichéd image, long dominated by a male and binary gaze, that is in the focus of the exhibition Femme Fatale. Gaze – Power – Gender at the Hamburger Kunsthalle. Beyond exploring a range of artistic approaches to the theme from the early 19th century to the present, the show aims to critically examine the myth of the femme fatale in its genesis and historical transformation.” (Text from the Hamburger Kunsthalle website)

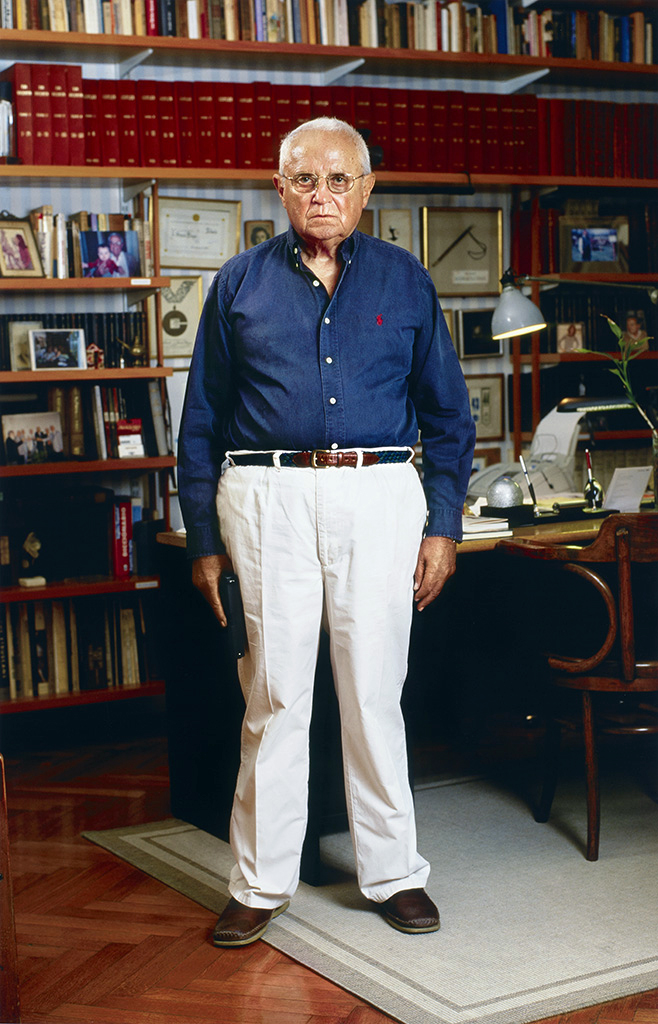

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. I have added further images and bibliographic information about the artists to the posting.

Many thankx to the Hamburger Kunsthalle for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The male gaze places women in the context of male desire, essentially portraying the female body as eye candy for the heterosexual man. By valuing the desires of the male audience, the male gaze supports the self-objectification of women.

According to the Theory of Gender and Power (Robert Connell), the sexual division of power reproduces inequities in power between men and women which are maintained by social mechanisms such as the abuse of authority and control in relationships.

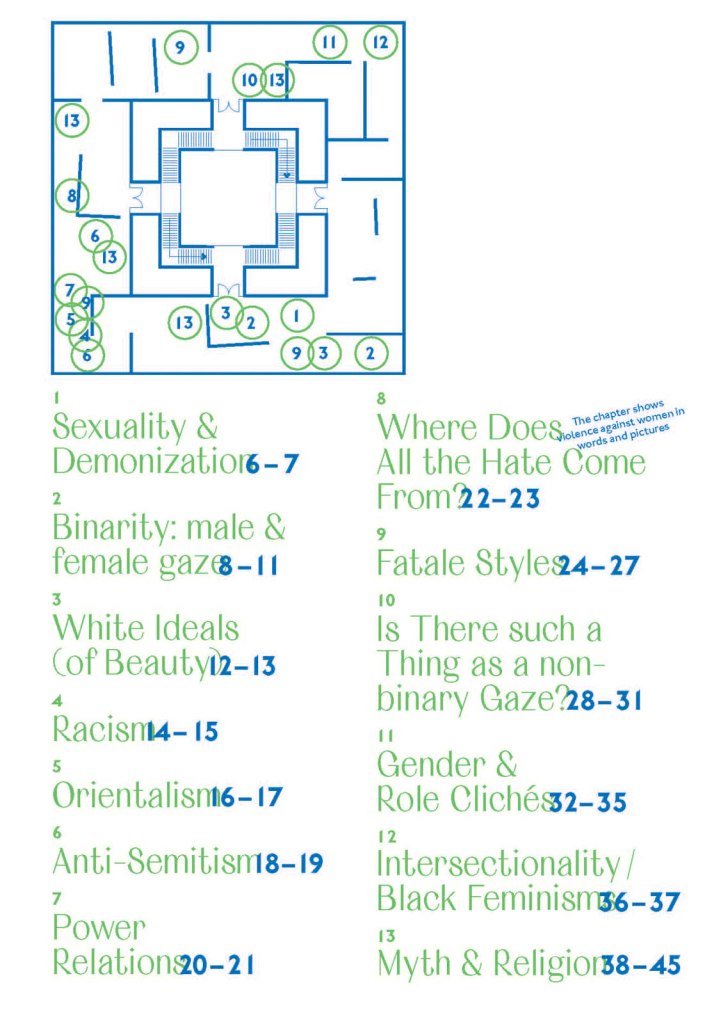

Pages from Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition Femme Fatale. Gaze – Power – Gender showing in the bottom posting, the room layout with sections to the exhibition

The femme fatale is a myth, a projection, a construction. She symbolises a visually coded female stereotype: the sensual, erotic and seductive woman whose allegedly demonic nature reveals itself in her ability to lure and enchant men – often leading to fatal results. It is this likewise dazzling and clichéd image, long dominated by a male and binary gaze, that is in the focus of the exhibition Femme Fatale. Gaze – Power – Gender at the Hamburger Kunsthalle. Beyond exploring a range of artistic approaches to the theme from the early 19th century to the present, the show aims to critically examine the myth of the femme fatale in its genesis and historical transformation.

The “classical” image of the femme fatale feeds above all on biblical and mythological female figures such as Judith, Salome, Medusa or the Sirens, who were widely portrayed as calamitous women in art and literature between 1860 and 1920. Characteristic of the femme fatale figure is the demonisation of female sexuality associated with these narratives. Around 1900, the femme fatale image was frequently projected onto real people, mainly actors, dancers or artists such as Sarah Bernhardt, Alma Mahler or Anita Berber. What is striking here is the simultaneity of important achievements of women’s emancipation and the increased appearance of this male-dominated image of women. In the sense of a counter-image that playfully picks up on aspects of the femme fatale figure, the New Woman, an ideal emerging well into the 1920s, also becomes important for the exhibition. A decisive caesura was set in the 1960s by feminist artists concerned with deconstructing the myth of the femme fatale – along with the corresponding viewing habits and pictorial traditions. Current artistic positions, in turn, deal with traces and appropriations of the archetypic image or establish explicit counter-narratives – often with reference to the #MeToo movement, questions of gender identities, female corporeality and sexuality, and by addressing the topic of the male gaze.

To investigate the constellations of gaze, power and gender that are constitutive for the image of the femme fatale and its transformations over time, the exhibition has assembled around 200 exhibits spanning a broad range of media and periods. On display will be paintings by Pre-Raphaelite artists (including Evelyn de Morgan, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John William Waterhouse) alongside Symbolist works (such as Fernand Khnopff, Gustave Moreau, Edvard Munch and Franz von Stuck), works of Impressionism (including Lovis Corinth, Max Liebermann, Édouard Manet, Max Slevogt), of Expressionism and New Objectivity (Dodo, Jeanne Mammen, Gerda Wegener, among others). The featured positions of the early feminist avant-garde (including VALIE EXPORT, Birgit Jürgenssen, Ketty La Rocca, Maria Lassnig, Betty Tompkins) along with current works based on queer and intersectional feminist perspectives (Nan Goldin, Mickalene Thomas, Zandile Tshabalala, among others), build a bridge all the way to the present.

Text from the Hamburger Kunsthalle website

Chapters of the exhibition

Carl Joseph Begas (German, 1794-1854)

Die Lureley

1835

Oil on canvas

124.3 × 135.3cm

© Begas Haus – Museum für Kunst und Regionalgeschichte Heinsberg

Dangerous waters – Lorelei and her ‘fatal’ sisters

During the Romantic era, the element of water was often associated with the idea of dangerous femininity. The figure of Lorelei, in particular, was widely and diversely interpreted in numerous works of art, music and literature. Clemens Brentano laid the foundation for the legend of Lorelei with his ballad Zu Bacharach am Rheine…, written in 1801. Here, for the first time, a female figure was linked to the Lorelei – a large slate rock on the bank of the river Rhine that was known for producing an unusual echo. The broad popular appeal of this legend began with the publication of Heinrich Heine’s poem Die Lore-Ley in 1824 and continued to grow throughout the century. Although neither Brentano nor Heine stylised Lorelei as a femme fatale, many 19th-century artistic representations of this myth reduced the female figure to her siren-like, demonic qualities. The legend of Lorelei also has a remarkable resonance in contemporary art: in her video work “das Schöne muss sterben!”, for example, Gloria Zein transfers the narrative into the urban present, giving it an ironic twist and reflecting critically on the power of beauty; Aloys Rump traces the myth that surrounds this famous rock in the Rhine back to its material origins, exposing the Lorelei legend as pure invention and projection.

Aestheticized, demonized, sexualized: the femme fatale in the Victorian age

The 19th-century image of the femme fatale was largely shaped by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This group of English artists around Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones was founded in 1848. Drawing on ancient myths and works of English literature, the Pre-Raphaelites (as they were later known) established a very specific ideal of beauty. Their depictions above all featured female figures to whom destructive or even fatal qualities had traditionally been attributed, such as Lilith, Medea, Circe and Helen of Troy. The Pre-Raphaelites deliberately emphasised the contrast between the subjects’ mythological demonisation and their visualisation as sensual beings of ethereal beauty. Later artists who were influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites created increasingly eroticised depictions of women, portraying them as both an ideal and a vision of fear. John William Waterhouse’s painting of Circe, for example, explicitly links her power to her both enchantingly and threateningly seductive nature. John Collier’s highly sexualised interpretation of Lilith, meanwhile, presents the mythic figure primarily as an object of male desire. This white, Victorian ideal of femininity and beauty, along with its (re-)presentation in a museum context, is reflected by Sonia Boyce in her video installation Six Acts. This work emerged from a critical intervention she performed at Manchester Art Gallery in 2018.

Sexuality & Demonisation

The term femme fatale originally describes a sensual, erotically seductive woman who puts men in danger and plunges them into their misfortune – not seldom with deadly consequences. In his painting Lilith, John Collier also illustrated such a prototype of a femme fatale. Here, the woman’s body is excessively sexualised and her sexuality demonised. This narrative also suggests: a woman’s lust is something dangerous. Even today, women are often morally condemned when they live out their sexuality openly. How can that be? Female lust is declared taboo, while male lust is celebrated? That is indeed problematic. However: the figure of the femme fatale is by now often appropriated by women as an instrument for self-empowerment.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917)

Circe offering the cup to Ulysses

1891

Oil on canvas

148 cm × 92cm

© Gallery Oldham

John William Waterhouse RA (6 April 1849 – 10 February 1917) was an English painter known for working first in the Academic style and for then embracing the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s style and subject matter. His artworks were known for their depictions of women from both ancient Greek mythology and Arthurian legend.

Born in Rome to English parents who were both painters, Waterhouse later moved to London, where he enrolled in the Royal Academy of Art. He soon began exhibiting at their annual summer exhibitions, focusing on the creation of large canvas works depicting scenes from the daily life and mythology of ancient Greece. Many of his paintings are based on authors such as Homer, Ovid, Shakespeare, Tennyson, or Keats. Waterhouse’s work is displayed in many major art museums and galleries, and the Royal Academy of Art organised a major retrospective of his work in 2009.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Binarity: male & female gaze

What is the male gaze actually all about?

The male gaze refers to the concept of a predominant masculine perspective; it represents the systematic use of male control in our society and its impact on us. The term was coined by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey who in the 1970s drew attention to how women in films were mostly portrayed as objects catering to the fantasies of heterosexual males. It was soon applied to other genres such as fashion, literature, music and art – and widely adopted in the everyday world. Whether in film, advertising, in novels, on the street, at school, during training or at university: the male gaze is omnipresent. It condemns, objectifies, defines standards and ideals, oppresses and classifies: male= active, female=passive. We all grew up with the phenomenon and are confronted with it on an everyday basis. As a result, all of us, including women and non-binary people, have more or less internalised it. Whether consciously or unconsciously, especially these groups tend to see themselves through a kind of mirror, anticipating the male gaze. But: understanding the male gaze also means being able to unlearn it.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

John Collier (English, 1850-1934)

Lilith

1887

Oil on canvas

194 × 104cm (76 × 41 in)

Atkinson Art Gallery and Library, Southport, Merseyside, England

© The Atkinson

Public domain

Lilith is an 1889 painting by English artist John Collier, who worked in the style of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The painting of the Jewish mythic figure Lilith is held in the Atkinson Art Gallery in Southport, England. It was transferred from Bootle Art Gallery in the 1970s.

Collier portrayed Lilith as a golden-haired, porcelain-skinned beautiful nude woman who fondles on her shoulder the head of a serpent, coiled around her body in a passionate embrace. Against the background of a dark, brown-green jungle, stands a naked female figure, whose pale skin and long blond hair falling down her back form a stark contrast with the forest. The head position and gaze of Lilith are turned away from the viewer, concentrating on the snake’s head resting on her shoulder. The snake encircles her body in several coils, starting around its closely spaced ankles, past the knee, to her lower abdomen, where it thereby conceals. Lilith supports the snake’s body with her hands in the area of her upper body, so that the snake’s head can lie over her right shoulder up to her throat. Lilith’s head is bent towards the snake, her cheek nestles against the animal. The brown tones of the snake’s body stand out in contrast with the pale woman’s body, but take up the colour scheme of the surrounding jungle. Collier presented his painting inspired by fellow painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1868 poem Lilith, or Body’s Beauty, which describes Lilith as the witch who loved Adam before Eve. Her magnificent tresses gave the world “its first gold,” but her beauty was a weapon and her charms deadly.

The magazine The British Architect described the work in 1887: “Here is a nude woman, whose voluptuous, round form is most gracefully represented, surrounded by a great serpent, the thickest part of which crosses it horizontally and cuts it in half; her head slides down her chest and she seems to be pulling it in tighter coils. The background is a coarse kind of green, repulsive and abominable.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (British, London 1828 – 1882 Birchington-on-Sea)

Henry Treffry Dunn (British, Truro 1838 – 1899 London)

Lady Lilith

1867

Watercolour and gouache

20 3/16 X 17 5/16 in. (51.3 x 44cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fascinated by women’s physical allure, Rossetti here imagines a legendary femme fatale as a self-absorbed nineteenth-century beauty who combs her hair and seductively exposes her shoulders. Nearby flowers symbolise different kinds of love. In Jewish literature, the enchantress Lilith is described as Adam’s first wife, and her character is underscored by lines from Goethe’s Faust attached by Rossetti to the original frame, “Beware … for she excels all women in the magic of her locks, and when she twines them round a young man’s neck, she will not ever set him free again.” The artist’s mistress, Fanny Cornforth, is the sitter in this watercolour, which Rossetti and his assistant Dunn based on an oil of 1866 (Delaware Art Museum).

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Lady Lilith is an oil painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti first painted in 1866-1868 using his mistress Fanny Cornforth as the model, then altered in 1872-1873 to show the face of Alexa Wilding. The subject is Lilith, who was, according to ancient Judaic myth, “the first wife of Adam” and is associated with the seduction of men and the murder of children. She is shown as a “powerful and evil temptress” and as “an iconic, Amazon-like female with long, flowing hair.” …

A large 1867 replica of Lady Lilith, painted by Rossetti in watercolour, which shows the face of Cornforth, is now owned by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It has a verse from Goethe’s Faust as translated by Shelley on a label attached by Rossetti to its frame:

“Beware of her fair hair, for she excels

All women in the magic of her locks,

And when she twines them round a young man’s neck

she will not ever set him free again.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

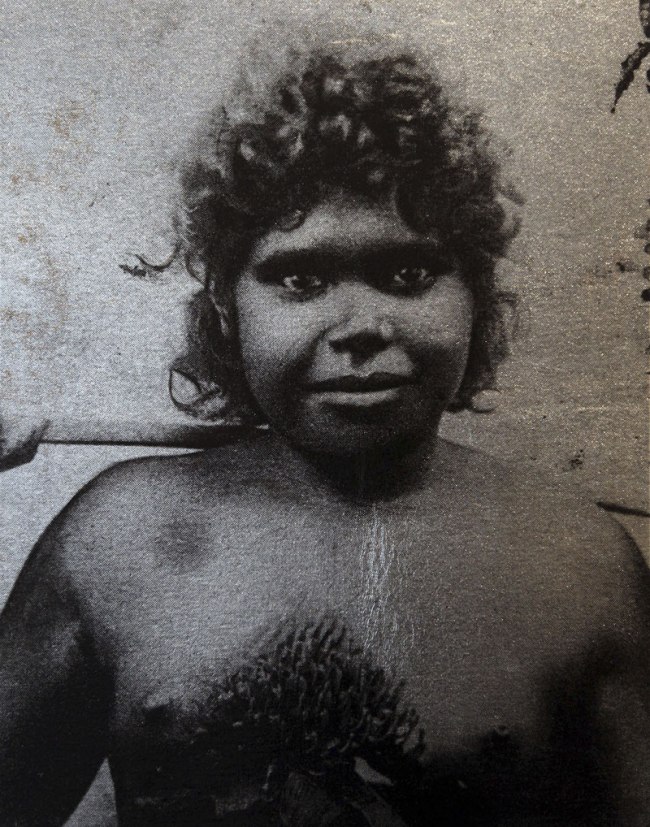

White Ideals (of Beauty)

Apparently, the ideal is the white woman. She is thought to be pure, innocent and therefore endearing. This racist idea reaches from colonial times all the way to the present day. In 2022 alone, it can be found in several social media trends. One of them is the clean girl look on TikTok.

But what is behind all this and who is the trend actually for? The clean girl aesthetic gone viral is rather minimalistic: simple clothes, subtle make-up with delicate lip gloss and small gold creole earrings. With this look, young women want to represent themselves as so-called “girl bosses”, meaning women who have everything under control. This, however, is no more than a male fantasy. It has nothing to do with real people. The clean girl image also reinforces perceptions of which kind of women are more socially accepted. Namely, those who, like the clean girl, have “smooth and porcelain-like skin”. This Eurocentric ideal of beauty can already be detected in the nineteenth-century work Lady Lilith by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Lady Lilith‘s skin is ivory white; she is combing her hair smooth, which is still wavy at the hairline. In the clean girl look hair is also straight, usually tied into a tight braid or chignon. Curly hair is excluded – and along with it especially Black people with Afro hair. Their natural appearance is thus portrayed as dirty in contrast to the allegedly pure clean girl look – a racist narrative that continues to try to position Black women in particular as inferior in society. Whereas, some of those characteristics appearing in the clean girl look originally were appropriated from Black Culture and then minimised: big gold creoles and gel-combed hairdos are just two of many examples. The clean girls with the most TikTok views represent this kind of standard beauty: thin, white and wearing expensive clothes. On the social media schoolyard, they are the ones who are considered as cool. But what they are doing while they are at it is bowing to racist, classist ideals that need to be made visible and discussed.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

Evelyn de Morgan (English, 1855-1919)

Medea

Nd

Oil on canvas

148 × 88cm

© Williamson Art Gallery and Museum, Birkenhead; Wirral Museums Service

Purchased 1927

Evelyn De Morgan (30 August 1855 – 2 May 1919), née Pickering, was an English painter associated early in her career with the later phase of the Pre-Raphaelite Movement, and working in a range of styles including Aestheticism and Symbolism. Her paintings are figural, foregrounding the female body through the use of spiritual, mythological, and allegorical themes. They rely on a range of metaphors (such as light and darkness, transformation, and bondage) to express what several scholars have identified as spiritualist and feminist content.

De Morgan boycotted the Royal Academy and signed the Declaration in Favour of Women’s Suffrage in 1889. Her later works also deal with the themes of war from a pacifist perspective, engaging with conflicts like the Second Boer War and World War I.

Text from the Wikipedia website

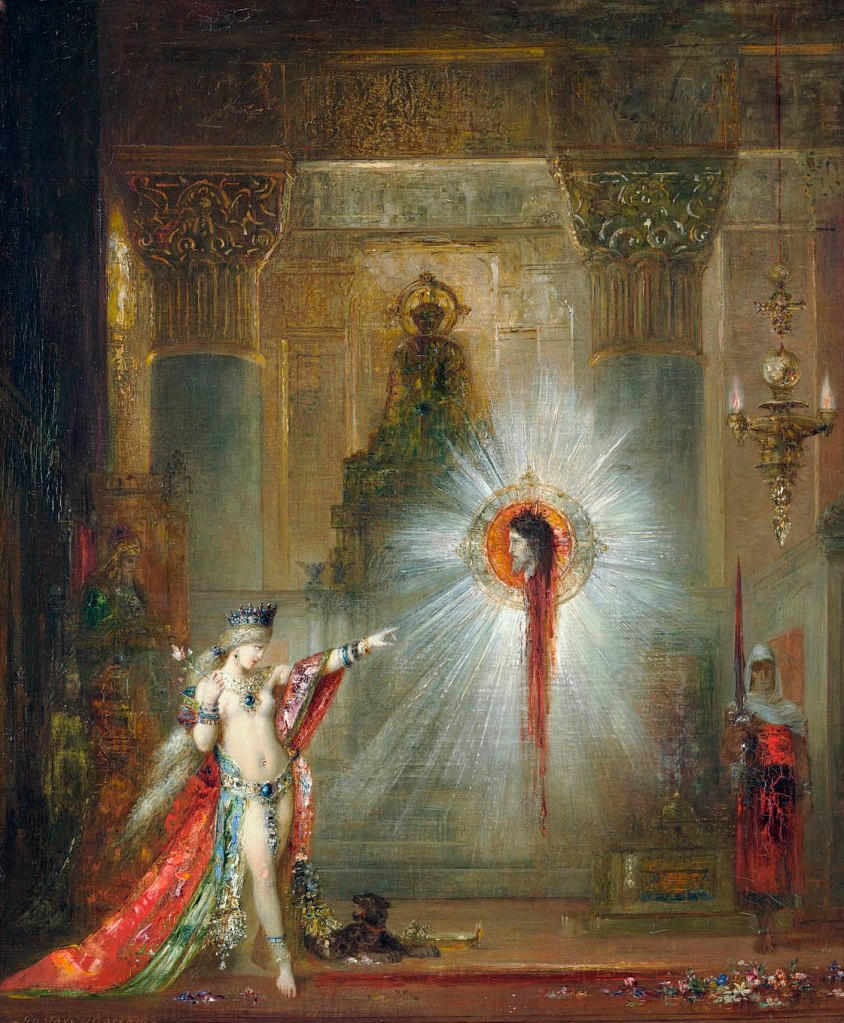

Gustave Moreau (1826-1898)

Oedipus and the Sphinx

1864

Oil on canvas

206 x 104.8cm

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Bequest of William H. Herriman, 1920

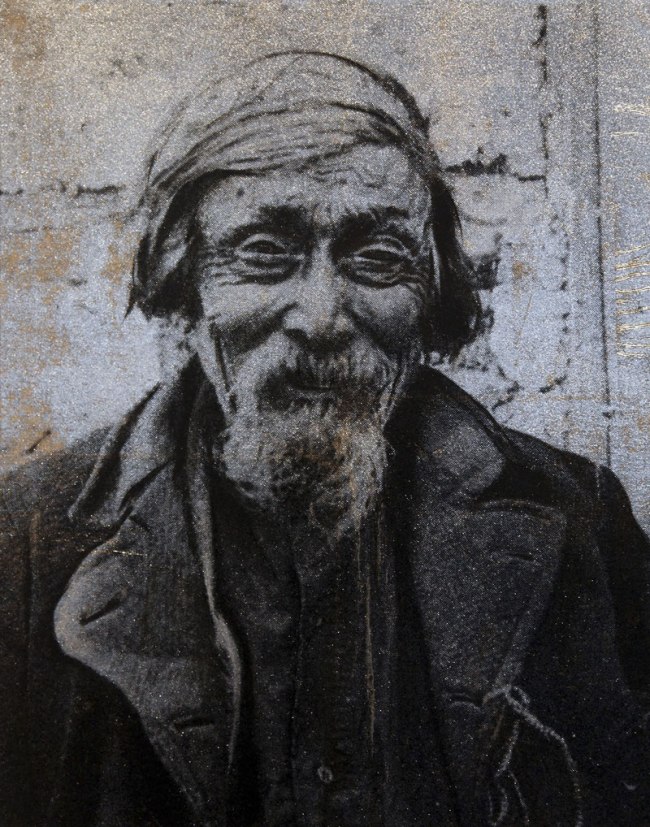

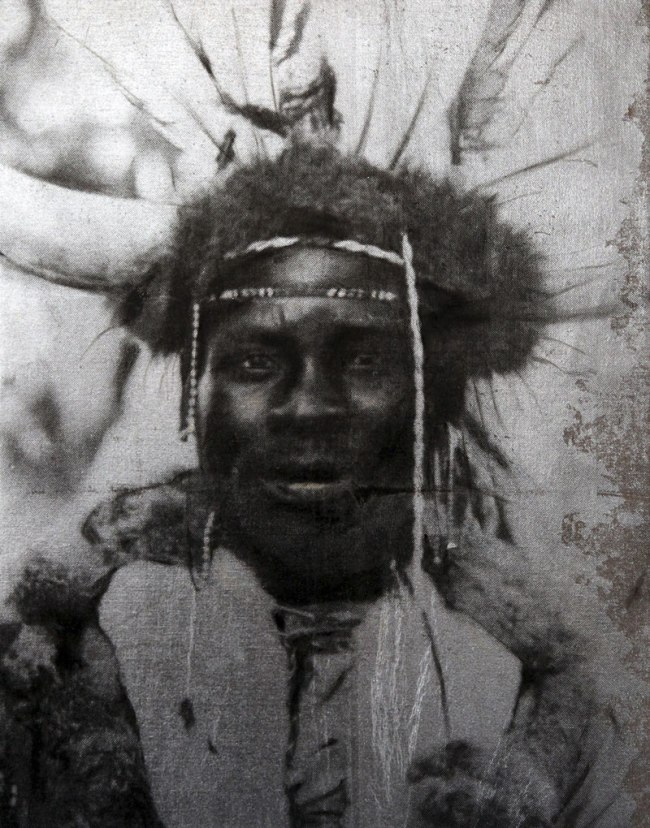

Racism

Racism means that people are subjected to depreciation exclusion or even to experiencing violence due to their origin, skin colour or religion. Racism comes in many forms. There is, for example, anti-Muslim, anti-Black or anti-Asian racism which is particularly directed against these groups. While such group based hostility was formerly justified above all by the “wrong” religious affiliation, from the 16th century on, allegedly scientific explanations became established. People were divided into different “races” from the time white people started enslaving Black people to then exploit them for economic profit in the new colonies. Today, most people are aware that there is no such thing as different “human races”. Instead, it is the different “social background” or “culture” that now is often used as an argument to racially stigmatise people. The ‘others’ may be described as ‘primitive’ and ‘uncultivated’, sometimes exoticised or sexualised. Men are portrayed as libidinous, women as erotic and, quite often, as their victims. The Indian postcolonialism theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak critically pinpointed this colonial perspective with the sentence: “White men are saving brown women from brown men.” This ironic statement emphasises the sense of civilisational superiority of white colonisers who saw themselves as “saviours”, but often came to the country as rapists and, on top of that, oppressed the female population in their countries of origin.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

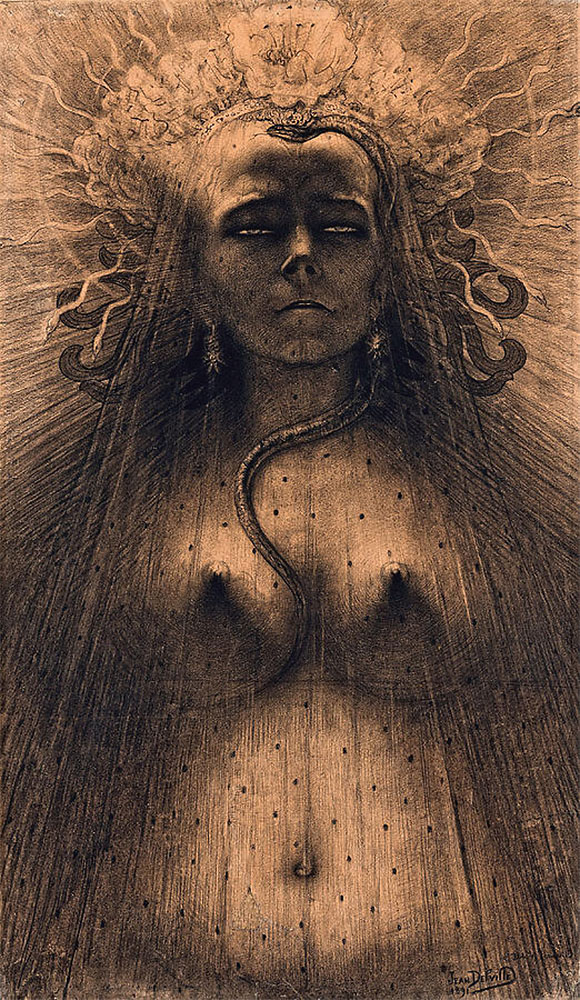

Jean Delville (Belgian, 1867-1953)

The Idol of Perversity (L’idole de la perversite)

1891

Jean Delville, The Idol of Perversity (L’idole de la perversite), 1891. Delville was a Belgian symbolist painter, author, poet and Theosophist, studying mystical and occultist philosophies. Such philosophies concentrate mainly on seeking the true origins of the universe, specifically of the divine and natural kind, believing that knowledge of ancient pasts offers a path to true enlightenment and salvation. Delville was the leading patron of Belgian Idealist movement, specifically in art circa the 1890s, having a belief system that upheld art to higher standards of substance, believing that it should express higher spiritual truth, based on principles of Ideal, or spiritual Beauty. …

The goal of the living body is to spiritualise itself and to refine our material selves, meaning to elevate ourselves to the level of not requiring or wanting things that are just of material value. Without a spiritual path or goal, men and women that walk the earth become slaves to their material possessions, forever destined to succumb to the desires, passions, greed, and egotistic need to always seek power over one another. Under this belief, the physical world we live in becomes the land of Satan, and those without a spiritual goal become merely his slaves. According to Delville, the first step to true enlightenment is to gain power over earthly temptations, such as promiscuity and erotic temptation. Truly enlightened soul is one that can use the power of his mind to rise above the temptations of, what was believed “unquenched bestial desires of a woman”. In late nineteenth century femme fatale embodied the kind of misogynistic idea that women were lower on the evolutionary scale, and female sex was that of animalistic, monstrous and aggressive, hence, the femme fatale characterisation, meaning that women’s grotesque sexual desires led men away from their spiritual goals, and thus driving them to live a life in sin, forever slaves to the Devil. In this painting Delville portrays the femme fatale as an almost demonic entity, with the bellow angel as to show her looming over the viewer, with an almost phallic snake, reminiscent of Franz von Stuck’s Sin, slithering between her pointed breasts. This image is a direct representation of Delville’s esoteric ideologies of material versus spiritual.

Art Universal. “Jean Delville, The Idol of Perversity (L’idole de la perversite), 1891,” on the Art Universal website August 8, 2017 [Online] Cited 03/03/2023

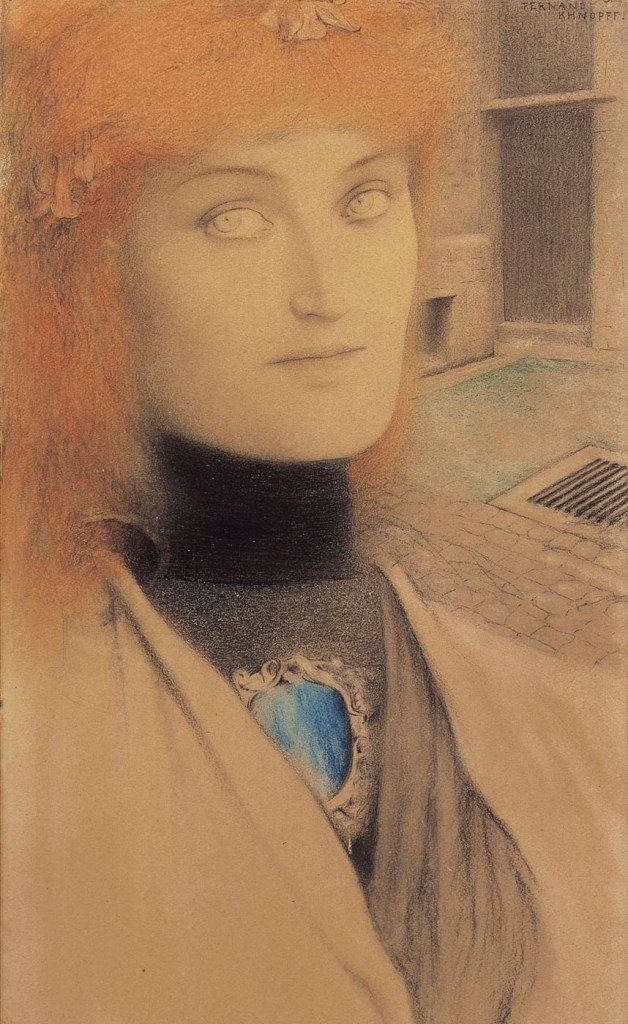

Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921)

Who Shall Deliver Me? (Christina Georgina Rossetti)

1891

Conté pen and coloured pencil on paper

21.9 x 13cm

© The Hearn Family Trust

Enigmatic images – the femme fatale in Symbolist art

Fantastical scenarios, imaginary dream worlds and psychological depths are the defining characteristics of Symbolism, a cultural movement that flourished throughout Europe from the 1880s onwards. The image of the femme fatale is also omnipresent in Symbolist art, but in these depictions, the female subjects often have an enigmatic, other-worldly appearance and their meaning is ambiguous. As the epitome of the cliché of ‘female mystery’, the sphinx is a prominent motif in Symbolist art. The image of this malevolent creature – a hybrid of woman, lion and bird – was strongly influenced by Gustave Moreau’s Oedipus and the Sphinx, an important early work by the painter. Moreau’s orientalised and eroticised interpretation of Salome as an ornamental figure also shaped the perception of her as a femme fatale. A similar composition featuring a vision of John the Baptist’s floating head is found in Odilon Redon’s Apparition. His figures, however, are even further removed from objective representation and concrete corporeality. These kinds of mystifying depictions were also interpreted and elaborated by other Symbolist artists, above all in Belgium and the Netherlands. In Fernand Khnopff’s subtle drawings, the femme fatale appears as a mysterious, ambiguous projection, addressing the themes of stereotypical femininity and androgyny.

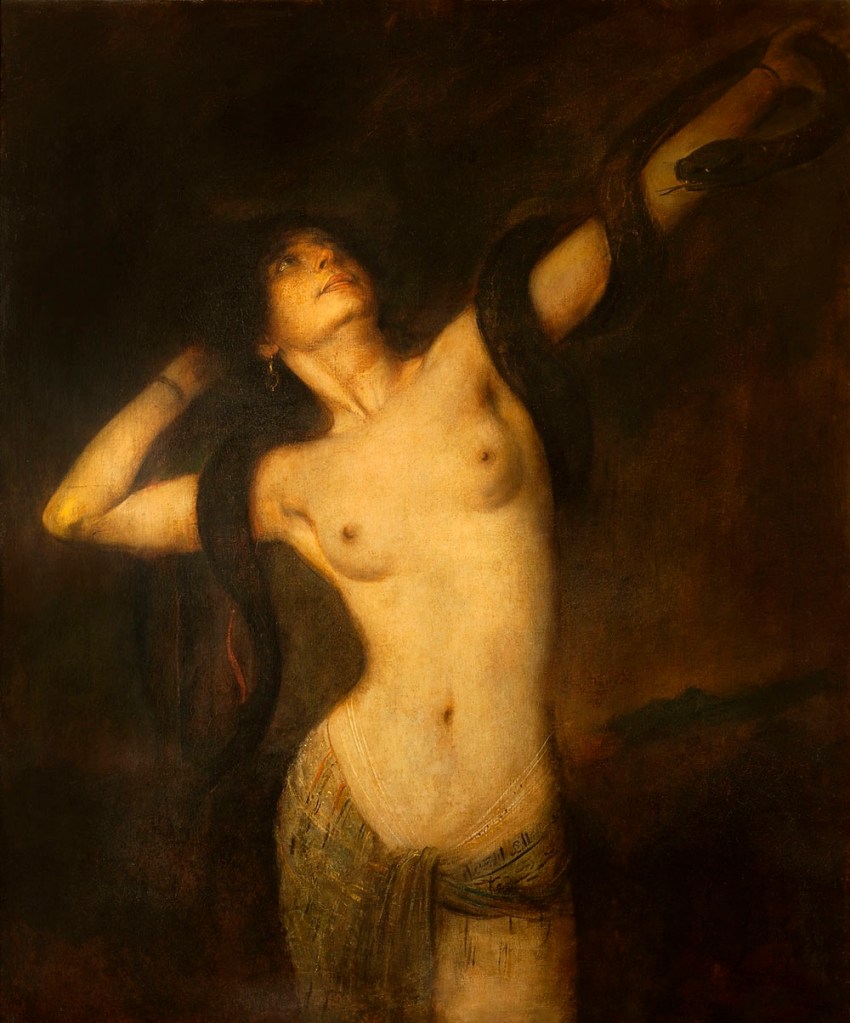

Focussing on the body – interpretations of the femme fatale in Munich

In contrast to the enigmatic dream worlds of French and Belgian Symbolism, the depictions of femmes fatales by artists of the Munich School focus more explicitly on women’s bodies. Carl Strathmann’s large-format interpretations of Gustave Flaubert’s historical novel Salammbô, which was frequently adapted in France, place the titular female figure in an ornamental Art Nouveau setting that is typical of the period. Franz von Stuck and Franz von Lenbach, on the other hand, focus on concrete physical realities; while their paintings are set in mythological and biblical contexts, they are mainly aimed at representing nudity. In Stuck’s interpretation of the Sphinx, for example, the subject is no longer depicted as a hybrid creature, but is a purely human, naked woman. Only the posture of the nude, who is reduced to her physicality and sensuality, recalls a sphinx. This kind of sexualization in images of femmes fatales often involves constructing a supposed ‘otherness’ of the depicted subject. Through the incorporation of orientalising elements and antisemitic attributions such as the stereotype of the ‘beautiful Jewess’, female subjects – above all Judith and Salome – are presented as alluring and desirable, but are at the same denigrated as ‘other’.

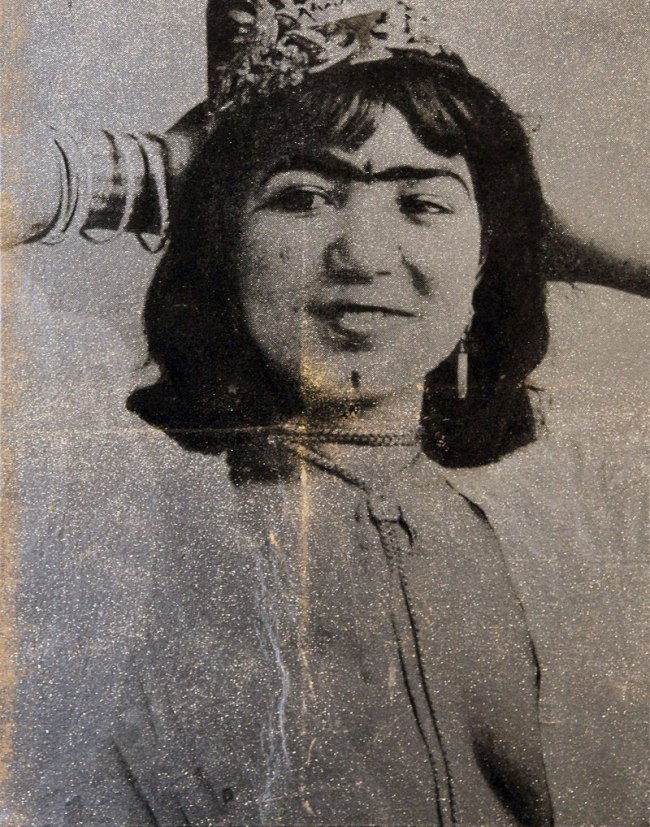

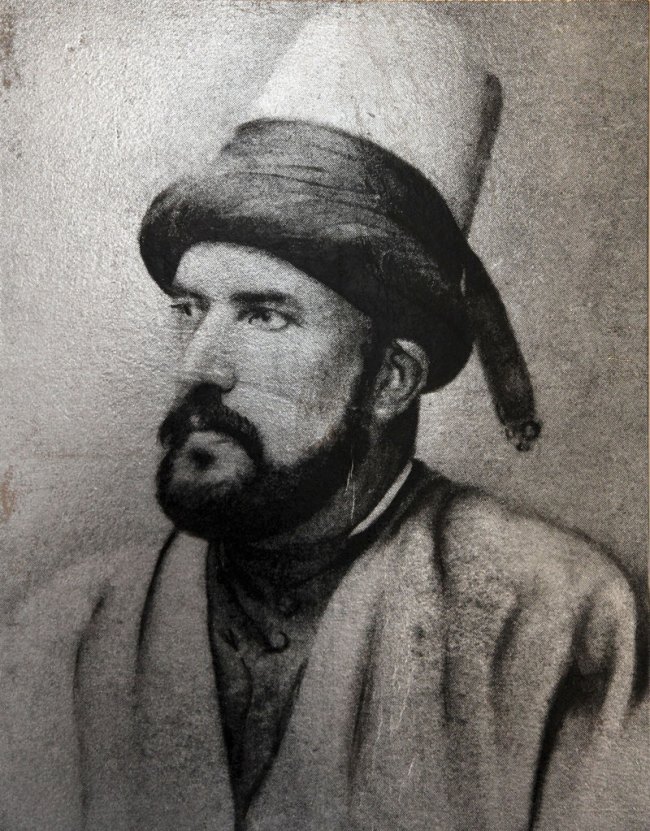

Orientalism

Turbans, veils, sabres, teacups, palm trees, colourful carpets and nude women in harems – this cliché-ridden image of the ‘Orient’ was spread in the West and was a major theme especially in nineteenth-century painting. In 1978, the Palestinian-American literature professor Edward Said published a book entitled Orientalism in which he characterised this image as a Western invention. By describing the ‘Orient’, meaning roughly those regions now called North Africa and the Near and Middle East, as ‘alien’ and ‘backward’, the West was able to present itself as culturally superior. This, at the same time, made it easier to justify imperialist ambitions to subjugate and exploit these regions. Orientalism has been typified by rejection and attraction alike: the people and customs of the region are portrayed as irrational, lazy and dishonest just as much as sensual, pleasure-oriented and seductive. A widespread symbol of this in painting was the figure of the “Odalisque”, a white slave girl, preferably drawn naked in the bath. She strikingly exemplifies the kind of fantasies that (mainly) white European men would live out in their depictions of the Orient: at once a ‘chaste’ victim of ‘Oriental’ tyrants and a ‘sinful’ seductress of Western conquerors. Many of these Orientalist clichés have survived to this day and can also be found, in anti-Muslim racisms, for example.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

Bruno Piglhein (1848-1894)

Egyptian Sword Dancer

1891

Oil on canvas

138 × 89cm

Private collection

© Courtesy Kunkel Fine Art, München

Franz Von Stuck (German, 1863-1928)

Judith and Holofernes

1926

Oil on canvas

157 × 83cm

Staatliche Schlösser, Gärten und Kunstsammlungen Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Schwerin

© Staatliche Schlösser, Gärten und Kunstsammlungen Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Staatliches Museum Schwerin

Foto: Elke Walford

Anti-Semitism

The term anti-Semitism describes a hostile attitude towards Jews. It manifests itself in various forms, from prejudice, to insults, to violence. Anti-Semitism, which has existed for thousands of years, is the oldest known form of group-specific hatred of people, regardless of gender. Its worst manifestation was during German National Socialism under Adolf Hitler when over six million Jewish people were murdered between 1933 and 1945 in Europe. What distinguishes anti-Semitism from other forms of discrimination is the idea of a cultural and economic superiority of the group being attacked, unlike, for example, racism or Islamophobia, where the counterpart is usually devalued. Instead of labelling Jews as backward, in stereotypes they often appear as representatives of a modern and sophisticated worldview, which is, however, portrayed as ‘decadent’ and ‘threatening’. Conspiracy theories also often contain anti-Semitic elements, as it is imagined that all Jewish people are wealthy, influential and well-connected and thus able to act as secret ‘string-pullers’ in international affairs. Anti-Semitic prejudices often refer to categories such as wealth and power, sexuality or external characteristics.

Visually, anti-Semitic body stereotypes are sometimes expressed through the depiction of large, crooked noses (‘hooknose’), bulging lips, narrow eyes, hunched posture, bowlegs and flat feet. Somewhat more subtle, but no less problematic, is the stereotype of the “beautiful Jewess”. This cliché image from art and literature around 1900 often showed Jewish women as smart, beautiful and seductive, but at the same time marked them as ‘foreign’ and ‘different’, for example, based on orientalising elements such as jewellery, etc.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

Antonin Idrac (French, 1849-1884)

Salammbô

1882

Plaster

Height: 182cm (71.6 in); width: 53 cm (20.8 in); depth: 71cm (27.9 in)

Musée des Augustins

Public domain

Carl Strathmann (German, 1866-1939)

Salammbô

1894

Mixed media on canvas

187.5 x 287cm

Strathmann’s curious work occupies an intermediate position between the art of painting and the crafts. His paintings are strange concoctions studded with colored glass and artificial gems, foreshadowing similar extravagances by the Viennese Jugendstil painter Gustav Klimt. In Strathmann’s painting Salammbô, inspired by Flaubert’s novel, the Carthaginian temptress reclines on a carpet spread out on a flower-strewn meadow. Swathed in veils whose design is as complex as that of the harp beside her head, she submits to the kiss of the mighty snake that encircles her. Lovis Corinth described how Strathmann, while working on the large picture, gradually covered the originally nude model with “carpets and fantastic garments of his own invention so that in the end only a mystical profile and the fingers of one hand protruded from a jumble of embellished textiles. … coloured stones are sparkling everywhere; the harp especially is aglitter with fake jewels.” According to Corinth, Strathmann knew “how to glue and sew” these on the canvas “with admirable skill.”

Anonymous. “Carl Strathmann, Salammbô,” on the Dark Classics website 12/05/2011 [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

Arnold Böcklin (Swiss, 1827-1901)

Sirens

1875

Tempera on canvas

Height: 46cm (18.1 in); width: 31cm (12.2 in)

Alte Nationalgalerie

Public domain

Arnold Böcklin (16 October 1827 – 16 January 1901) was a Swiss symbolist painter. …

Influenced by Romanticism, Böcklin’s symbolist use of imagery derived from mythology and legend often overlapped with the aesthetic of the Pre-Raphaelites. Many of his paintings are imaginative interpretations of the classical world, or portray mythological subjects in settings involving classical architecture, often allegorically exploring death and mortality in the context of a strange, fantasy world.

Böcklin is best known for his five versions (painted 1880 to 1886) of the Isle of the Dead, which partly evokes the English Cemetery, Florence, which was close to his studio and where his baby daughter Maria had been buried. An early version of the painting was commissioned by a Madame Berna, a widow who wanted a painting with a dreamlike atmosphere.

Clement Greenberg wrote in 1947 that Böcklin’s work “is one of the most consummate expressions of all that is now disliked about the latter half of the nineteenth century.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Franz Von Stuck (German, 1863-1928)

Sphinx

1904

Oil on canvas

83 × 156.5cm

© Loan from the Federal Republic of Germany as a permanent loan to the Hessian State Museum in Darmstadt

Foto: Wolfgang Fuhrmannek, HLMD

Franz Ritter von Stuck (February 23, 1863 – August 30, 1928), born Franz Stuck, was a German painter, sculptor, printmaker, and architect. Stuck was best known for his paintings of ancient mythology, receiving substantial critical acclaim with The Sin in 1892. In 1906, Stuck was awarded the Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown and was henceforth known as Ritter von Stuck. …

Stuck’s subject matter was primarily from mythology, inspired by the work of Arnold Böcklin. Large forms dominate most of his paintings and indicate his proclivities for sculpture. His seductive female nudes are a prime example of popular Symbolist content. Stuck paid much attention to the frames for his paintings and generally designed them himself with such careful use of panels, gilt carving and inscriptions that the frames must be considered as an integral part of the overall piece.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Gustav Adolf Mossa (French, 1883-1971)

The Satiated Siren (Die gesättigte Sirene)

1905

Oil on canvas

81 × 54cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nizza

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Foto: Michel Graniou

Gustav-Adolf Mossa (28 January 1883 – 25 May 1971) was a French illustrator, playwright, essayist, curator and late Symbolist painter. …

Symbolist paintings

Mossa’s decade long Symbolist period (1900-1911) was his most prolific and began as a reaction to the recent boom of socialite leisure activity on the French Rivera, his works comically satirising or condemning what was viewed as an increasingly materialistic society and the perceived danger of the emerging New Woman at the turn of the century, whom Mossa appears to consider perverse by nature.

His most common subjects were femme fatale figures, some from Biblical sources, such as modernised versions of Judith, Delilah and Salome, mythological creatures such as Harpies or more contemporary and urban figures, such as his towering and dominant bourgeoise woman in Woman of Fashion and Jockey. (1906). His 1905 work Elle, the logo for the 2017 Geschlechterkampf exhibition on representations of gender in art, is an explicit example of Mossa’s interpretation of malevolent female sexuality, with a nude giantess sitting atop a pile of bloodied corpses, a fanged cat sitting over her crotch, and wearing an elaborate headress inscribed with the Latin hoc volo, sic jubeo, sit pro ratione voluntas (What I want, I order, my will is reason enough).

Many aspects of Mossa’s paintings of this period were also indictive of the decadent movement, with his references to Diabolism, depictions of lesbianism (such as his two paintings of Sappho), or an emphasis on violent, sadistic or morbid scenes.

Though these paintings are the subject of most present day exhibitions, scholarly articles and books on the artist, they were not released to the public until after Mossa’s death in 1971.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Inverted images – the femme fatale turns grotesque

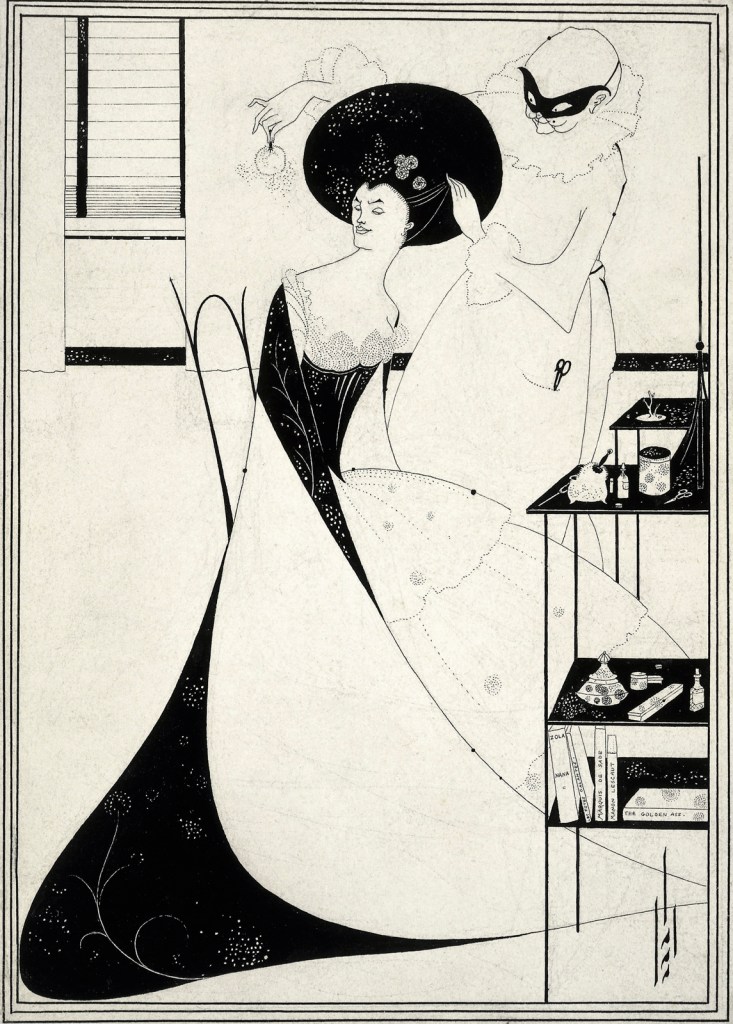

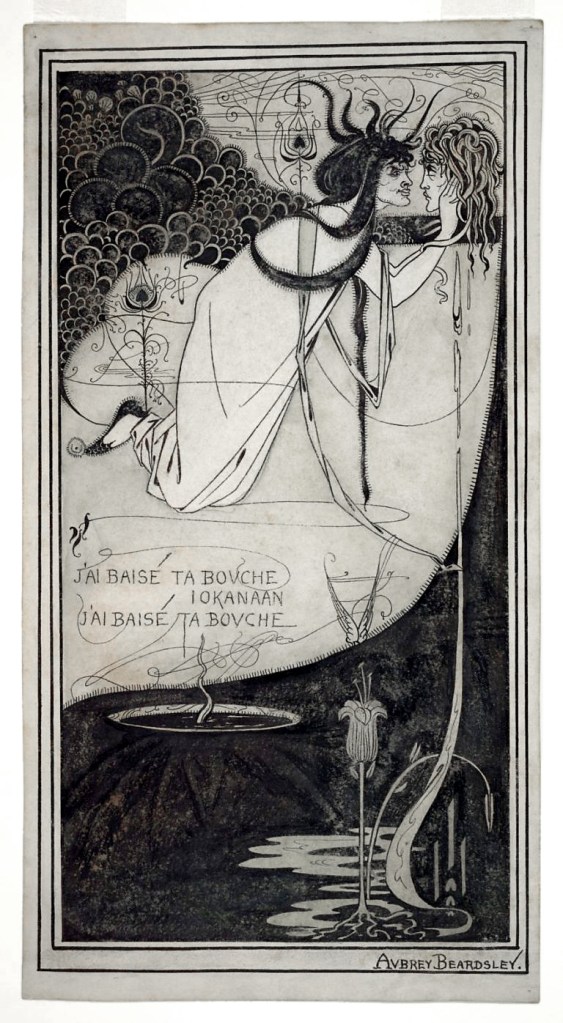

In the late 19th century, artists began using exaggeration and caricature to highlight the grotesque, bizarre and absurd qualities of the femme fatale motif, suggesting that the traditional image of the wickedly seductive enchantress had become redundant. While these inverted images of the femme fatale illustrate the constructed nature of this concept, they in turn employ clichés of demonic femininity. Arnold Böcklin gives an ironic, grotesque twist to a popular artistic motif in his painting Sirens, where the typically emphasised seductiveness of the hybrid creatures appears to have the opposite effect. In Gustav-Adolf Mossa’s The Satiated Siren, meanwhile, the siren’s outstanding feature is her bloodthirsty instinct. In Carl Strathmann’s almost humorously exaggerated depiction of the Head of Medusa, on the other hand, Medusa’s petrifying gaze is no longer intended to shock the viewer. Although ancient myths still provided the subject matter for these interpretations, they were increasingly losing their exemplary function and could often only be transposed to the present in a grotesque guise. Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations after Oscar Wilde’s play Salome (1893) were highly influential; while these also contained some vividly macabre motifs, the unmistakable ornamental aesthetic of defined lines and flat spatial planes made them appear less frightening.

Carl Strathmann (German, 1866-1939)

Head of Medusa

c. 1897

Watercolour and ink

69.8 cm x 69.5cm

Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung

CC BY-SA 4.0

Carl Strathmann (11 September 1866, Düsseldorf – 29 July 1939, Munich) was a German painter in the Art Nouveau and Symbolist styles.

His father, also named Carl Strathmann, was a merchant and manufacturer, who later served as consul in Chile. His mother, Alice, was originally from Huddersfield, England, and was an art enthusiast. From 1882 to 1886, he studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, with Hugo Crola, Heinrich Lauenstein and Adolf Schill. After being dismissed for a “lack of talent”, he enrolled at the Grand-Ducal Saxon Art School, Weimar where, from 1888 to 1889, he studied in the master class taught by Leopold von Kalckreuth.

When Kalckreuth left, he did as well; moving to Munich, where he lived a Bohemian lifestyle as a free-lance artist, and met the painter Lovis Corinth, who became a lifelong friend and associate. In 1894, he painted one of his best known works: “Salammbô”, inspired by a novel of the same name by Gustave Flaubert. In this monumental painting (6 x 9 feet) Salammbô, a high priestess of the Carthaginians, is shown caressing a snake, as part of a ritual sacrifice. Many were horrified, calling it a “sadistic fantasy”. The scandal made him immediately famous.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Toilette of Salome (second version)

1893

Please note: This drawing may not be in the exhibition but Beardsley’s drawings of Salome are mentioned in the exhibition text (below)

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

J’ai baisé ta bouche Iokanaan

1892-1893

Please note: This drawing may not be in the exhibition but Beardsley’s drawings of Salome are mentioned in the exhibition text (below)

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

John and Salome

1893

Please note: This drawing may not be in the exhibition but Beardsley’s drawings of Salome are mentioned in the exhibition text (below)

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Madonna

1895

Oil on canvas

90 × 71cm

Hamburger Kunsthalle, permanent loan of the Stiftung Hamburger Kunstsammlungen, acquired 1957

© SHK / Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk

Public domain

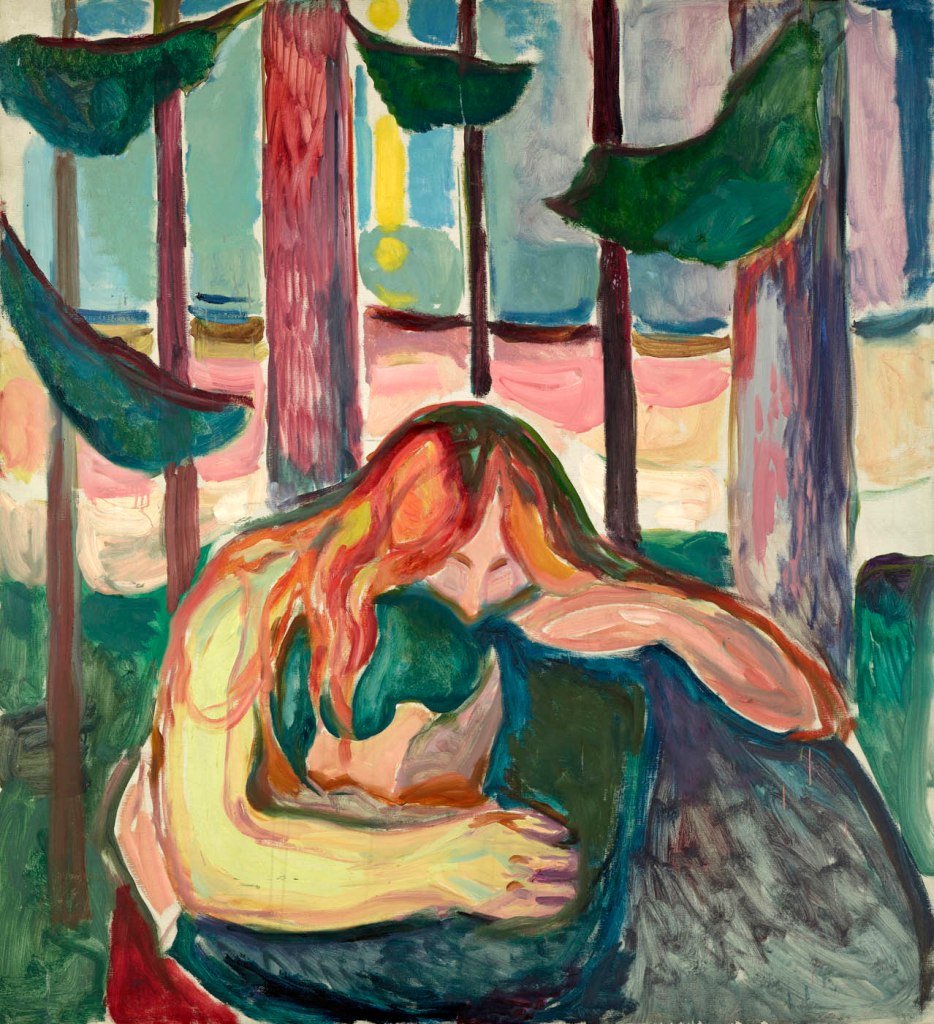

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Vampire in the forest

1916-1918

Oil on canvas

150 × 137cm

Munch Museet, Oslo

© Munchmuseet

Femme fatale, saint and vampire – the elevation and denigration of women in the art of Edvard Munch

Among the many images of the femme fatale that were created around 1900, Edvard Munch’s ambiguous, both positively and negatively connoted female figures occupy a place of their own. Existential questions and universal themes such as life, death, love, loss and grief are central to Munch’s art. Women are omnipresent in his compositions, appearing in a variety of roles and stereotypical depictions; at the same time, they are inseparably linked to the artist’s personal experience of life and love. The transfiguration of this experience often leads to the opposite extreme. Munch’s painting Madonna illustrates the contradictory aspects of his image of women: the depicted subject can be interpreted as a lustful femme fatale or as a saintly figure. The relationship and tension between the sexes is another leitmotif in Munch’s art. This is illustrated by his painting Vampire in the Forest, which leaves the viewer in doubt as to whether the depicted female figure is a loving woman or a bloodthirsty creature. Demonisations of femininity and female sexuality that threaten male existence appear throughout Munch’s oeuvre. They are as much an expression of his fears as of his self-stylisation as a victim – and once again reveal Munch’s image of the femme fatale to be a misogynistic projection.

Impressionist digressions – staged presentations from the theatrical to the nude

The theme of the femme fatale is even addressed in Impressionist art, which aimed to create immediate and realistic depictions rather than idealised representations. Here, however, the image was presented in very different ways. Lovis Corinth’s stage-like scenario shows a dramatically made-up, bare-breasted Salome bending over the head of John the Baptist. The abysmal aspect of her power is visualised above all through the sexualization of her body. The female figures in Max Liebermann’s interpretations of the biblical theme of Samson and Delilah, on the other hand, are far less eroticised. The choice of this subject – an unusual one for the artist – reveals his awareness of the popularity of the femme fatale motif. The lack of historicising details and focus on the strength of the austere-looking female figures, however, situate Liebermann’s stark images more decisively in the present than those of Corinth. The French sculptor Auguste Rodin also portrayed a femme fatale figure – but was evidently using this theme as a justification for an explicit nude. In his drawing, which takes its title from Gustave Flaubert’s novel Salammbô, the female subject is reduced to her sex: the reference to the fictional character is, therefore, merely a pretext.

Power Relations

Smash the Patriarchy! Free the Nipple!

Women and many non-binary people are confronted with various dress codes and rules of conduct in their everyday lives. The skirt should not be too short. Breastfeeding in public is taboo. A woman has to wear a bra in the office, otherwise there may be professional consequences. Above all, bodies perceived as female are being eroticised. The Free the Nipple movement is fighting against this. It’s a matter of choice: whether it’s a long or short skirt, bra or not – everyone decides for themselves. The breast perceived as female is also censored in social media.

The Free the Nipple movement has been criticised for not paying enough attention to the nuances concerning Black people and People of colour, for not pursuing an intersectional approach, but rather for primarily reflecting a white feminism.

Fighting for Female Freedom

In Spain, it was decided in May 2022 that catcalling should be banned. Catcalling? Many women experience obtrusive looks, being whistled at or hearing disrespectful comments about their appearance on the streets every day. Verbal sexual harassment is harmful and leaves its mark. Yet it still is often presented as an alleged compliment, also in films. In the 1968 performance Tapp- und Tastkino (Tap and Touch Cinema), VALIE EXPORT strapped a ‘scaled-down cinema’ in front of her bare chest. Passers-by had ‘public access’ for thirty seconds at a time during which they were allowed to touch her breasts. Interestingly, it was not VALIE EXPORT and her (upper) body that were thus exposed, but rather the passers-by who accepted this offer in public. Who is being embarrassed here and who is a voyeur? How are power and gaze relationships reversed here?

The Bechdel Test was introduced in 1985 by writer and cartoonist Alison Bechdel, namely with her comic dykes to watch out for. The test focuses on the stereotyping of women in film has only three rules:

1/ The movie has to have at least two women in it,

2/ Who talk to each other,

3/ About something other than a man.

Pretty simple criteria that don’t say much about whether a film is sexist!? Yet many films do not fulfil the criteria of the Bechdel Test.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

VALIE EXPORT (Austrian, b. 1940)

Tapp- und Tastkino (Tap and Touch Cinema)

1968

Video: Digibeta PAL, B/W, Sound, 1:08 min

© VALIE EXPORT / Courtesy Electric Arts Intermix (EAI), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 / SAMMLUNG VERBUND, Wien

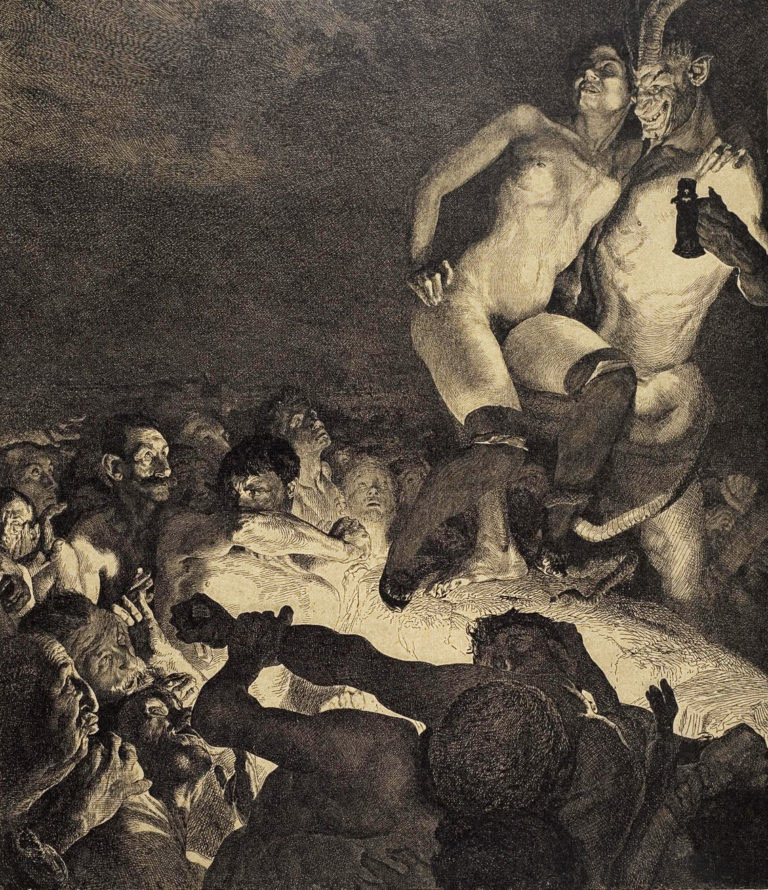

Otto Greiner (German, 1869-1916)

The Devil Showing Woman to the People

1898

From the five-part series Of Woman

Pen lithograph

70 × 55 cm

Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig

© bpk / Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig

Public domain

Otto Greiner (16 December 1869 – 24 September 1916) was a German painter and graphic artist. He was born in Leipzig and began his career there as a lithographer and engraver. He relocated to Munich around 1888 and studied there under Alexander Liezen-Mayer. Greiner’s mature style – characterised by unexpected spatial juxtapositions and a sharply focused, photographic naturalism – was strongly influenced by the work of Max Klinger, whom he met in 1891 while visiting Rome.

Where Does All the Hate Come From?

Hatecore

Misogyny is an attitude that refers to hatred of women (Ancient Greek: misos = hate, gyne = woman). It has existed for thousands of years all over the world. It can be seen in many historical works of art, in the extermination fantasies of Otto Greiner, for example, but also in our modern times. Since the emergence of the internet, misogyny has also increasingly manifested itself in the digital space, where people perceived as female are many times more likely than people perceived as male to be targeted, sexualised and threatened.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

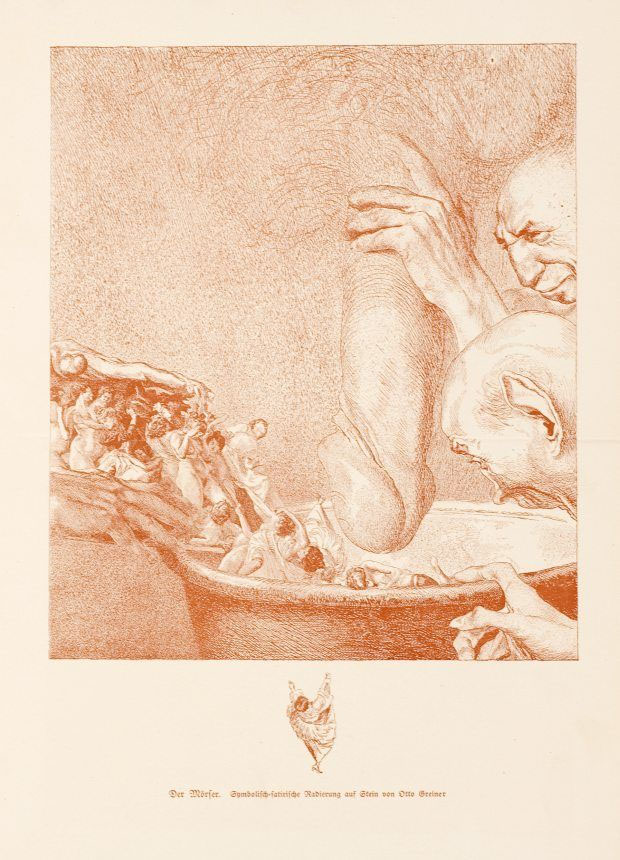

Otto Greiner (German, 1869-1916)

The Mortar

1900

From the five-part series Of Woman

Pen lithograph, crimson print

62 × 46cm

Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig

© bpk / Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig

Lovis Corinth (German, 1858-1925)

Salome II

1899/1900

Oil on canvas

127 × 147cm

Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig

© bpk / Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig / Ursula Gerstenberger

Lovis Corinth (21 July 1858 – 17 July 1925) was a German artist and writer whose mature work as a painter and printmaker realised a synthesis of impressionism and expressionism.

Corinth studied in Paris and Munich, joined the Berlin Secession group, later succeeding Max Liebermann as the group’s president. His early work was naturalistic in approach. Corinth was initially antagonistic towards the expressionist movement, but after a stroke in 1911 his style loosened and took on many expressionistic qualities. His use of colour became more vibrant, and he created portraits and landscapes of extraordinary vitality and power. Corinth’s subject matter also included nudes and biblical scenes.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Max Liebermann (German, 1847-1935)

Samson and Delila

1902

Oil on canvas

151.2 x 212cm

© Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Max Liebermann (20 July 1847 – 8 February 1935) was a German painter and printmaker, and one of the leading proponents of Impressionism in Germany and continental Europe. In addition to his activity as an artist, he also assembled an important collection of French Impressionist works.

The son of a Jewish banker, Liebermann studied art in Weimar, Paris, and the Netherlands. After living and working for some time in Munich, he returned to Berlin in 1884, where he remained for the rest of his life. He later chose scenes of the bourgeoisie, as well as aspects of his garden near Lake Wannsee, as motifs for his paintings. Noted for his portraits, he did more than 200 commissioned ones over the years, including of Albert Einstein and Paul von Hindenburg.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Becoming femme fatale: between projection and self-presentation

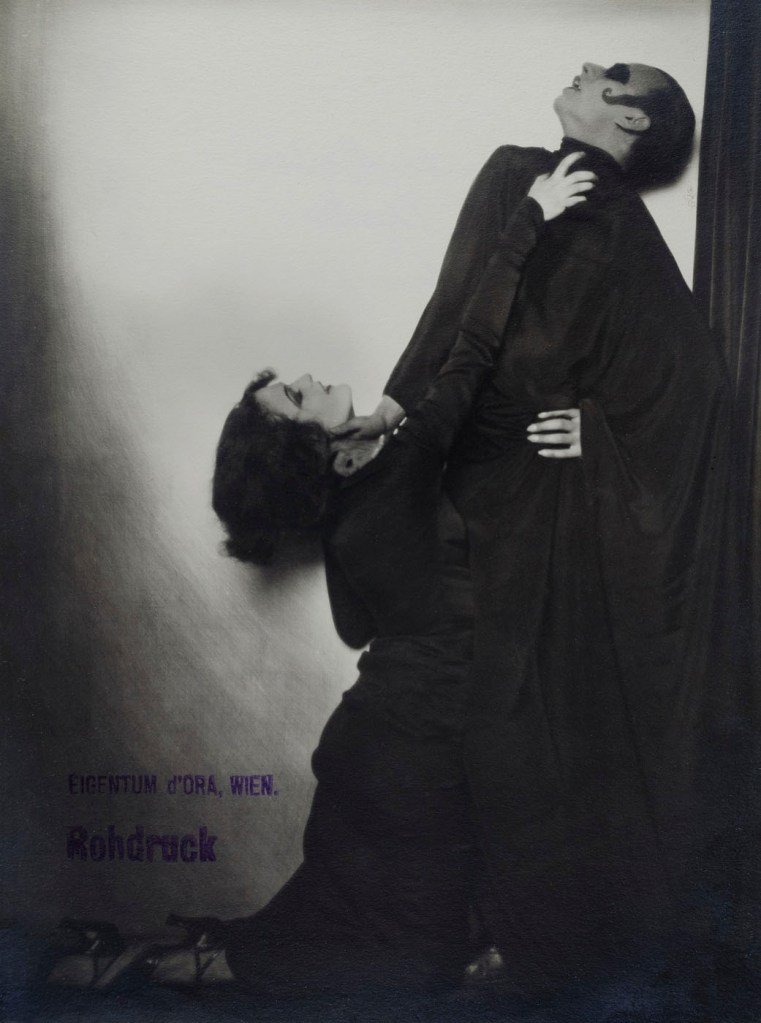

In the period around 1900, the image of the femme fatale was increasingly projected onto real people. A cult of female actors, dancers and artists emerged, above all in cities such as Paris, Vienna and Berlin. Femmes fatales were now also situated in the realm of theatre, cinema and variety entertainment. Male projection and active self-presentation both played their part in this development, and particular modern media served to disseminate corresponding depictions of women: Alfons Mucha’s posters of Sarah Bernhardt contributed significantly to the fact that in public perception, the image of Bernhardt as a person gradually merged with her theatrical roles – although the actress herself also cultivated her reputation as an eccentric figure. In the same way, many people in the public eye used the medium of photography to increase their popularity. Portrait photographs taken by Madame d’Ora, for example, were used to publicise Anita Berber and Sebastian Droste’s scandal-ridden show Dances of Vice, Horror and Ecstasy. The composer Alma Mahler was also among those who had their portraits taken at Atelier d’Ora. Her reputation as a femme fatale was, however, mainly shaped by Oskar Kokoschka. The painter developed an obsessive desire for Mahler during their affair and at the same time stylised her as a disastrous, destructive force – a demonisation that reached its climax in the destruction of a life-size fetish doll he had commissioned in his ex-lover’s likeness.

Madame d’Ora (Atelier d’Ora)

Anita Berber and Sebastian Droste

1922

From “The Dances of Vice, Horror and Ecstasy”

Dora Kallmus (Madame d’Ora) (Austrian, 1881-1963), Arthur Benda (German, 1885-1969)

Anita Berber and Sebastian Droste in their dance Märtyrer [Martyrs]

1922

Gelatin silver print

Albertina, Vienna

Dora Philippine Kallmus (20 March 1881 – 28 October 1963), also known as Madame D’Ora or Madame d’Ora, was an Austrian fashion and portrait photographer.

In 1907, she established her own studio with Arthur Benda in Vienna called the Atelier d’Ora or Madame D’Ora-Benda. The name was based on the pseudonym “Madame d’Ora”, which she used professionally. D’ora and Benda operated a summer studio from 1921 to 1926 in Karlsbad, Germany, and opened another gallery in Paris in 1925. She was represented by Schostal Photo Agency (Agentur Schostal) and it was her intervention that saved the agency’s owner after his arrest by the Nazis, enabling him to flee to Paris from Vienna.

Her subjects included Josephine Baker, Coco Chanel, Tamara de Lempicka, Alban Berg, Maurice Chevalier, Colette, and other dancers, actors, painters, and writers.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Arthur Benda (23 March 1885, in Berlin – 7 September 1969, in Vienna) was a German photographer. From 1907 to 1938 he worked in the photo studio d’Ora in Vienna, from 1921 as a partner of Dora Kallmus and from 1927 under the name d’Ora-Benda as the sole owner. …

In 1906, Arthur Benda met photographer Dora Kallmus, who also trained with Perscheid. When she opened the Atelier d’Ora on Wipplingerstrasse in Vienna in 1907, Benda became her assistant. The Atelier d’Ora specialised in portrait and fashion photography. Kallmus and Benda quickly made a name for themselves and soon supplied the most important magazines. The peak of renown was reached when Madame d’Ora photographed the present nobility in 1916 on the occasion of the coronation of Emperor Charles I as King of Hungary.

In 1921, Arthur Benda became a partner in Atelier d’Ora, which also ran a branch in Karlovy Vary during the season. In 1927 Arthur Benda took over the studio of Dora Kallmus, who had run a second studio in Paris since 1925, and continued it under the name d’Ora-Benda together with his wife Hanny Mittler. In addition to portraits, he mainly photographed nudes that made the new company name known in men’s magazines worldwide. A major order from the King of Albania Zogu I, who had himself and his family photographed in 1937 for three weeks by Arthur Benda in Tirana secured Arthur Benda financially. In 1938 he opened a new studio at the Kärntnerring in Vienna, which he continued to operate under his own name after the Second World War.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Anita Berber (10 June 1899 – 10 November 1928) was a German dancer, actress, and writer who was the subject of an Otto Dix painting. She lived during the time of the Weimar Republic. …

Her hair was cut fashionably into a short bob and was frequently bright red, as in 1925 when the German painter Otto Dix painted a portrait of her, titled “The Dancer Anita Berber”. Her dancer friend and sometime lover Sebastian Droste, who performed in the film Algol (1920), was skinny and had black hair with gelled up curls much like sideburns. Neither of them wore much more than low slung loincloths and Anita occasionally a corsage worn well below her small breasts.

Her performances broke boundaries with their androgyny and total nudity, but it was her public appearances that really challenged taboos. Berber’s overt drug addiction and bisexuality were matters of public chatter. In addition to her addiction to cocaine, opium and morphine, one of Berber’s favourites was chloroform and ether mixed in a bowl. This would be stirred with a white rose, the petals of which she would then eat.

Aside from her addiction to narcotic drugs, she was also a heavy alcoholic. In 1928, at the age of 29, she suddenly gave up alcohol completely, but died later the same year. She was said to be surrounded by empty morphine syringes.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Anita Berber (1899-1928), and to a lesser extent her husband / dance partner Sebastian Droste (1892-1927), have come to epitomise the decadence within Weimar era Berlin, their colourful personal lives overshadowing to a large extent their careers in dance, film and literature. Yet the couple’s daring and provocative performances are being re-assessed within the history of the development of expressive dance, and their extraordinary book ‘Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase’ (‘Dances of Vice, Horror and Ecstasy’-1922), is a ‘gesamkunstwerk’ (total work of art) of Expressionist ideology largely unrecognised outside a devoted cult following.

The book

Berber and Droste chose to express themselves almost exclusively through the Expressionist / Modernist ethos, which was in itself filtered through the angst of Germany during the Weimar period.

Expressionism had been in existence before Weimar and, like many art movements, it had no formal beginnings, as opposed to a ‘school’ of artists who might band together under a common technique. It was fundamentally a reaction against the Impressionists who were seen by the Modernists as merely portrayers of ‘reality’ but who had failed to add anything of the artists own interior processes such as intuition, imagination and dream. This new wave of artists found inspiration in painters such as Van Gogh and Matisse but also drew from writers such as Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and the Symbolists, together with the philosophy of Nietzsche and Freudian psychology.

Expressionists believed the artist should utilise “what he perceives with his innermost senses, it is the expression of his being; all that is transitory for him is only a symbolic image; his own life is his most important consideration. What the outside world imprints on him, he expresses within himself. He conveys his visions, his inner landscape and is conveyed by them”. Herwert Walden: Erster Deutscher Herbstsalaon (1913).

The image is the poem as portrayed in the book by D’Ora. Interestingly, it is doubted whether the dance was performed (at least in Vienna) topless. Once again, this would indicate that the book is to be considered as its own specific entity. The poems cite their inspirations: artists Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso and Matthias Grünewald and authors lsuch as Villiers De L’Isle Adam, Edgar Allan Poe, Paul Verlaine, E.T.A. Hoffman and Hanns Heinz Ewers.

Lapetitemelancolie. “Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923,” on the La Petite Melancolie website 14/09/2015 [Online] Cited 01/03/2023

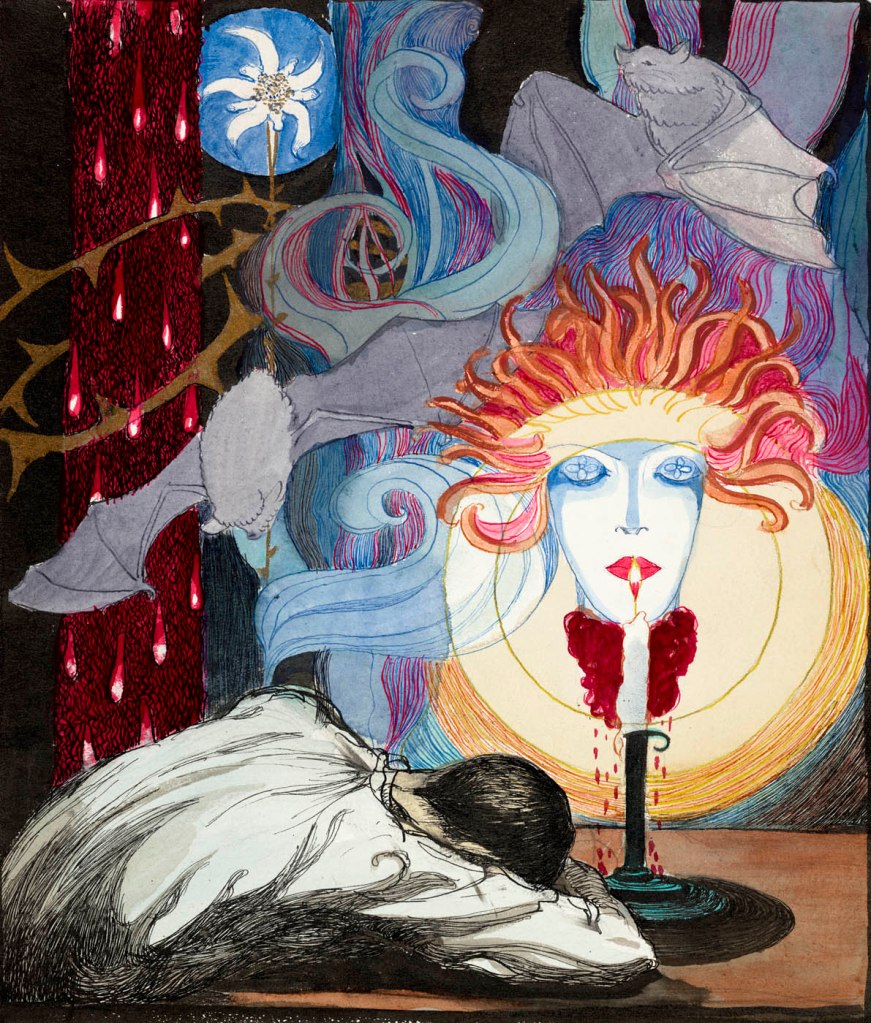

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890-1976)

Man and Medusa

1910-1914

Watercolour, pencil and ink drawing

24.7 x 21cm

Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Reproduction: Dorin Alexandru Ionita, Berlin

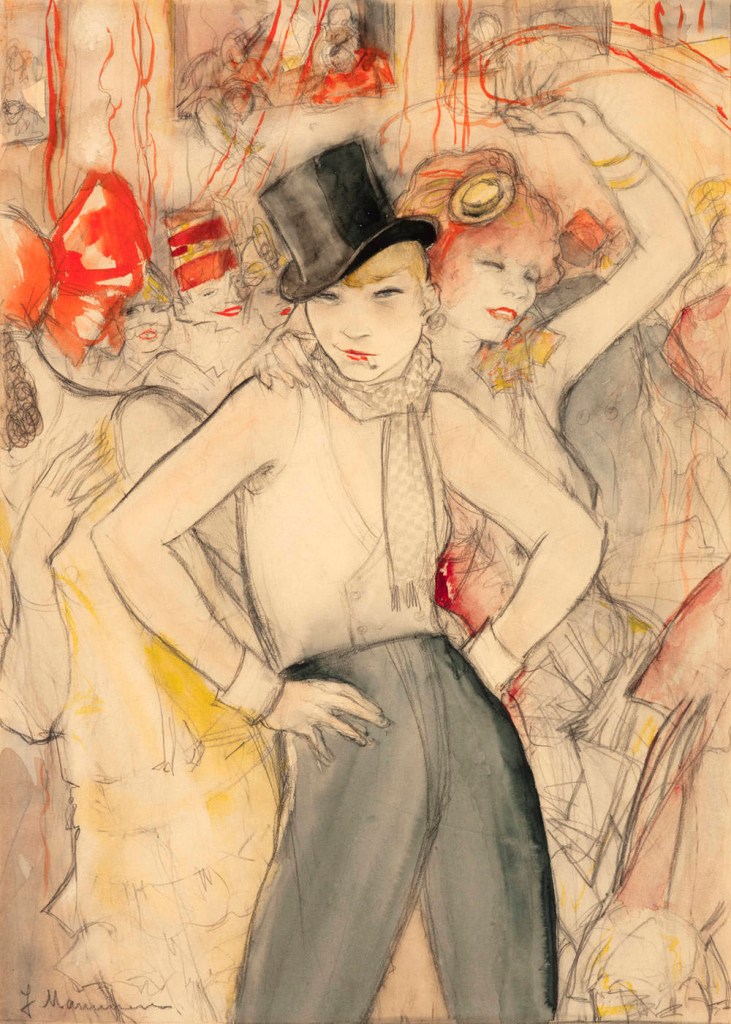

The New Woman – a counter-image to the femme fatale?

Strongly influenced by their experiences during the First World War, the artists associated with the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement focused on present-day themes and realities. Their works reflected a changing society and a new relationship between the sexes: women were no longer only active in the domestic roles of wife and mother, but were now also participating in political and social life outside the home, wearing clothes that would traditionally be read as masculine, and pursuing careers – as artists and office workers, but also as revue dancers, waitresses or sex workers. With their bobbed hair, painted red lips, trouser suits, hats and cigarettes, they represented a new ideal: the New Woman. The image of the New Woman was omnipresent in illustrated women’s magazines and satirical journals of the time. The artist Jeanne Mammen, whose early work was greatly inspired by Symbolism, articulated women’s growing self-awareness and a new understanding of sexuality and gender in her paintings, while Gerda Wegener’s portraits of Lili Elbe drew attention to the existence of gender identities beyond the binarism of male and female. The motif of the femme fatale was now countered by a contemporary, emancipated ideal of womanhood that replaced traditional gender roles and stereotypes.

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890-1976)

She represents!

1928

(In: Simplicissimus, 32, Nr. 47)

Three-colour print on paper

38.5 × 28cm

Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin, Jeanne Mammen Stiftung

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Reproduction: Mathias Schormann

Fatale styles

Garçonne style

Black top hat slanting one way, cigarette slanting the other, red lips, short hair, men’s suit, challenging pose: this is how Berlin artist Jeanne Mammen saw the “New Woman” in the wild 1920s, the “garçonne” (feminine form of the French “garçon”, boy). She got rid of the corset, and with it the expectations of how women should dress or behave.

Snakes

Snakes are the perfect accessory to signal danger and seduction at the same time. Pure sex appeal! Remember: in the Bible, it is the nasty snake that persuades Eve to nibble from the tree of knowledge, and afterwards Adam and Eve are suddenly ashamed of being naked but also find it somehow exciting … Women are called snakes when they are considered manipulative and use their sex appeal to seduce men who supposedly don’t really want that. The combination of the naked female figure and snakes is particularly popular in the 19th century, when women had hardly any social power or status, but started rebelling against that. Strange coincidence, isn’t it?

Long flowing hair

Long Flowing Hair is considered a symbol of absolute femininity and seduction par excellence in nineteenth-century paintings. If it is shaggy or even made of snakes (beware: Medusa head!), this is supposed to indicate that its wearer is morally depraved. Conversely, in the twentieth century, short hair usually stands for emancipation from outdated gender images and for a free, sometimes queer sexuality.

Mirrors

“Women see themselves being looked at,” wrote the English art critic John Berger. Women looking at themselves (narcissistically) in the mirror in paintings are meant to prove the vanity of the female sex. Yet these paintings rather prove the dominance of the male gaze that turns women into objects through its constant scrutiny or even surveillance. Some say that the mirror in the paintings has now been replaced by computer or smartphone screens, in which especially women are reflected for the male gaze on social media. Do you see it that way too?

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

Franz von Lenbach (German, 1836-1904)

Serpent Queen

1894

Oil on canvas

123 × 106cm

Kunstsammlung Züll, Sankt Augustin

© Kunstsammlung Züll, Sankt Augustin

Gerda Wegener (Danish, 1886-1940)

Lili Elbe

c. 1928

Watercolour

Please note: This watercolour may not be in the exhibition but Wegener’s paintings are mentioned in the exhibition text (above)

Gerda Wegener (Danish, 1886-1940)

Lili with a Feather Fan

1920

Please note: This art work may not be in the exhibition but Wegener’s paintings are mentioned in the exhibition text (above)

Gerda Wegener (Danish, 1885-1940)

Queen of Hearts (Lili)

1928

Please note: This art work may not be in the exhibition but Wegener’s paintings are mentioned in the exhibition text (above)

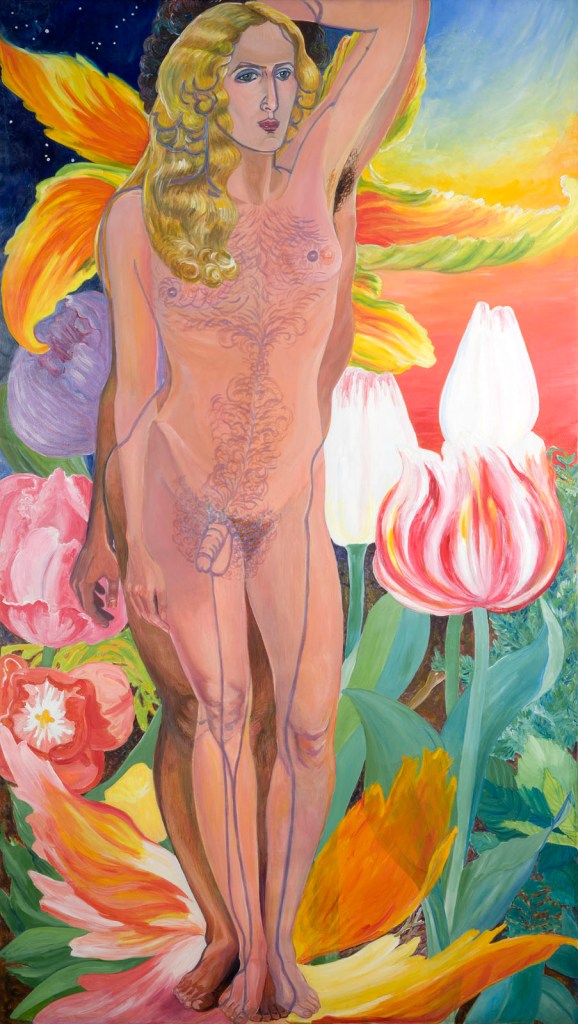

Sylvia Sleigh (American born Wales, 1916-2010)

Lilith

1967

Acrylic on canvas

274.6 × 152.4cm

Rowan University Art Gallery, Glassboro, New Jersey

© Estate of Sylvia Sleigh

Foto: Karen Mauch Photography/Rowan University Art Gallery

Is There such a Thing as a non-binary Gaze?

The non-binary gaze does not exist! As long as we are living in a society dominated by men, there can be no non-binary gaze. Because it is not our own gender identity that decides how we look at others, but the system in which we live. And that, all over the world, is still patriarchy. So as long as we are living in social structures in which humanity is divided binarily into male and female, we cannot escape this gaze. For this, it does not matter where on the gender scale we locate ourselves, whether we characterise ourselves as male, female, non-binary or whatever. To have a female gaze, we would have to live in matriarchy. Therefore, under the global domination of male capitalist structures, there can be no queer, no trans (siehe LGBTQIA), no Black Gaze, because all these identities continue to be marginalised and discriminated against. Gazes, especially in art, are always connected with power, with external determinations, with conditioning. There can be no non-binary gaze for the sole reason that it would not classify living beings into different sexes, would not categorise them. In the required non-binary form of society – which would be interested in the equality of the different – this form of exercising power would not even exist.

But there would still be gazing wouldn’t there? Or does it mean that for that reason alone there can be no non-binary gaze?

The non-binary gaze is the future!

The male gaze divides people into men and women, into those who look and those who are looked at, into the active and the passive, into subjects and objects. The non-binary gaze abolishes “gender” as a distinguishing feature altogether because it has no interest in this type of category. Neither living beings nor anything else like colours, styles or smells are assigned to a single gender, but exist only for and from themselves. Individual features such as lipstick, stubble or breasts are not read as indicators of gender, but are perceived impartially and without this filter in their specific properties, such as shape, colour, structure etc. Therefore, this gaze does not exert any power, because it does not classify and evaluate what is being looked at into any existing categories. It does not look from top to bottom, not from bottom to top, not at individual parts or the overall view, but it does all this simultaneously with everyone, the gazers as well as those gazed at. The non-binary gaze has the power to destabilise our entire world order, because qualities and characteristics can now be perceived in a completely new way, without prejudices and evaluations. For this concerns not only human bodies but all forms of being that we can imagine.

Actually, it is interesting that we not only classify people, but also, for example, shapes – angular vs round – or smells – tart vs sweet – according to gender.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

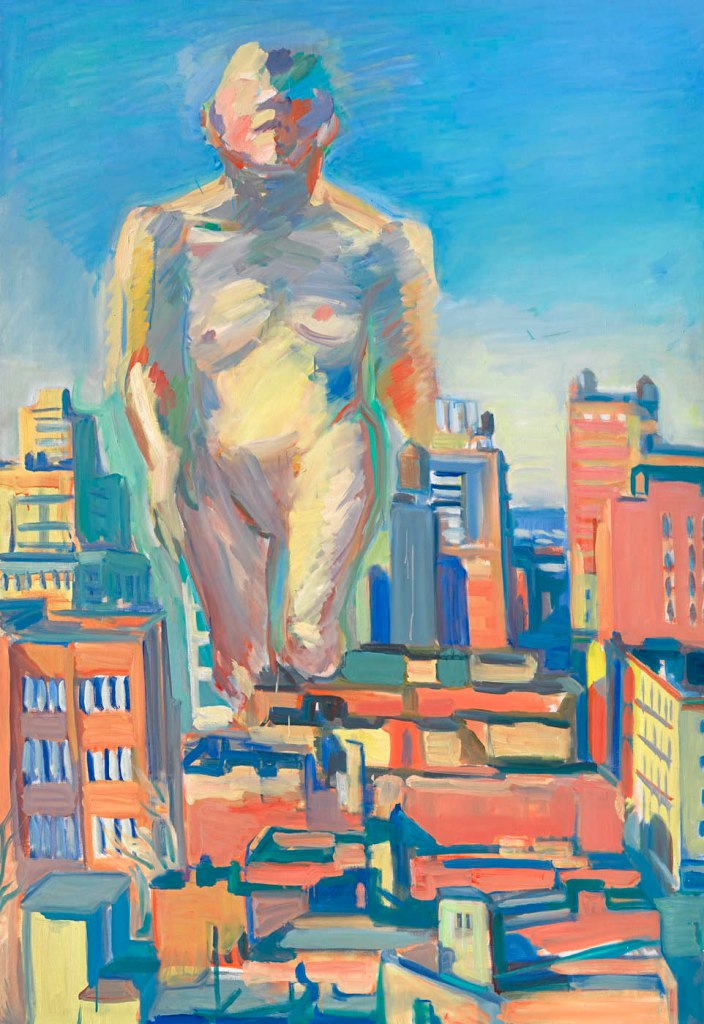

Maria Lassnig (Austrian, 1919-2014)

Woman Power

1979

Oil on canvas

182 x 126cm

Albertina Wien – The ESSL Collection

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Foto: Peter Kainz

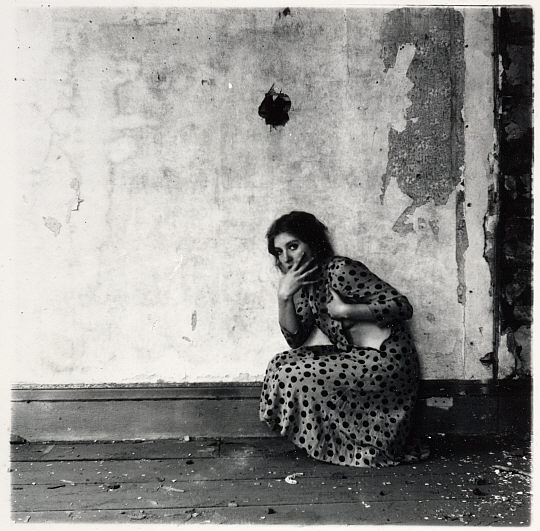

Deconstructing, appropriating and retelling: abolishing the image of the femme fatale

The fight against the traditional image of the femme fatale began at the latest with the emergence of feminist art in the 1960s: feminist avant-garde artists challenged such outdated notions of women and began creating their own new narratives of femininity, sexuality and physicality. Self-portraiture and self-presentation, especially in the medium of photography, takes on a particular significance in the creation of self-empowering images of one’s own body. Female artists find many different ways to deal with the clichéd image of the femme fatale. Deconstructive approaches by artists such as Ketty La Rocca have contributed a great deal to dismantling this image, as have ironic and subversive appropriations by the likes of Birgit Jürgenssen. Other female artists reimagine the mythological figures who were long depicted as femmes fatales, presenting them, as Francesca Woodman did, in subtly restaged scenarios; depicting them as powerful goddesses – as seen, for example, in the works of Mary Beth Edelson; or, like Sylvia Sleigh, situating them outside the boundary of binary gender. Arresting representations of female corporeality, meanwhile, such as those created by Maria Lassnig and Dorothy Iannone, provide positive images that leave the narrative of demonic, deadly female sexuality far behind them.

Gender & Role Clichés

What does gender mean?

Gender describes the social, lived, perceived sex of a person. Gender is an English term, but is also used in German, precisely when it comes to social characteristics and gender identity. Gender is not limited to what is assigned to us at birth on the basis of physical characteristics (sex) but rather refers to socially constructed attributes, opportunities and relationships.

The teacher who says to you: “Well, your handwriting doesn’t look like that of a girl.” The colour pink is for girls and women, just like dresses and skirts; the colour blue and trousers are for boys and men. The latter should not cry, that would be weak. So, better for them to suppress their feelings? But then there is the saying “Boys will be boys”, meaning that’s just the way they all are. Boys are seen as wild and rebellious, girls as calm and understanding. But these are not biological traits; it’s the way we were brought up in a system of patriarchy. So, boys are allowed to get away with more, while girls are expected to put up with a lot of things. Role stereotypes hurt and reduce us all and press us into categories. Because they say: all people in a group should behave in the same way – which is pretty absurd.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

Untitled, 1975-1980

1975-1980

Gelatin silver print

Please note: This image may not be in the exhibition but Woodman’s photographs are mentioned in the exhibition text (above)

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

House #4

Providence, Rhode Island, 1976

Gelatin silver print

Please note: This image may not be in the exhibition but Woodman’s photographs are mentioned in the exhibition text (above)

Nan Goldin (American, b. 1953)

C performing as Madonna, Bangkok

1992

Archival pigment print, ed. #2/25

76.2 × 114.3cm

Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

© Nan Goldin

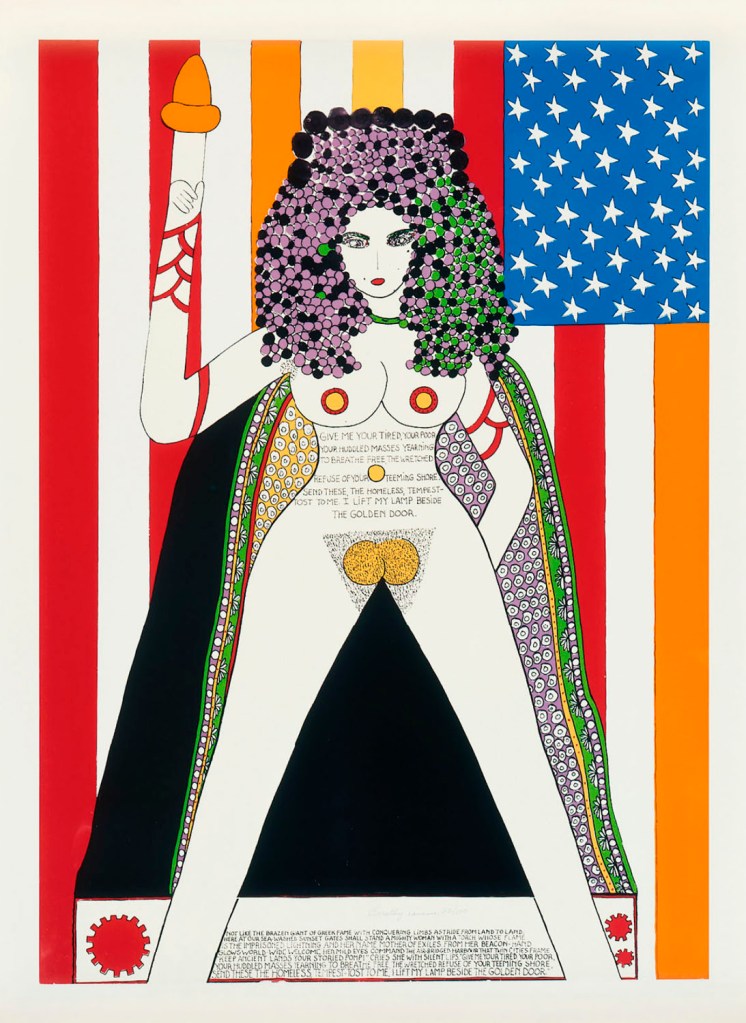

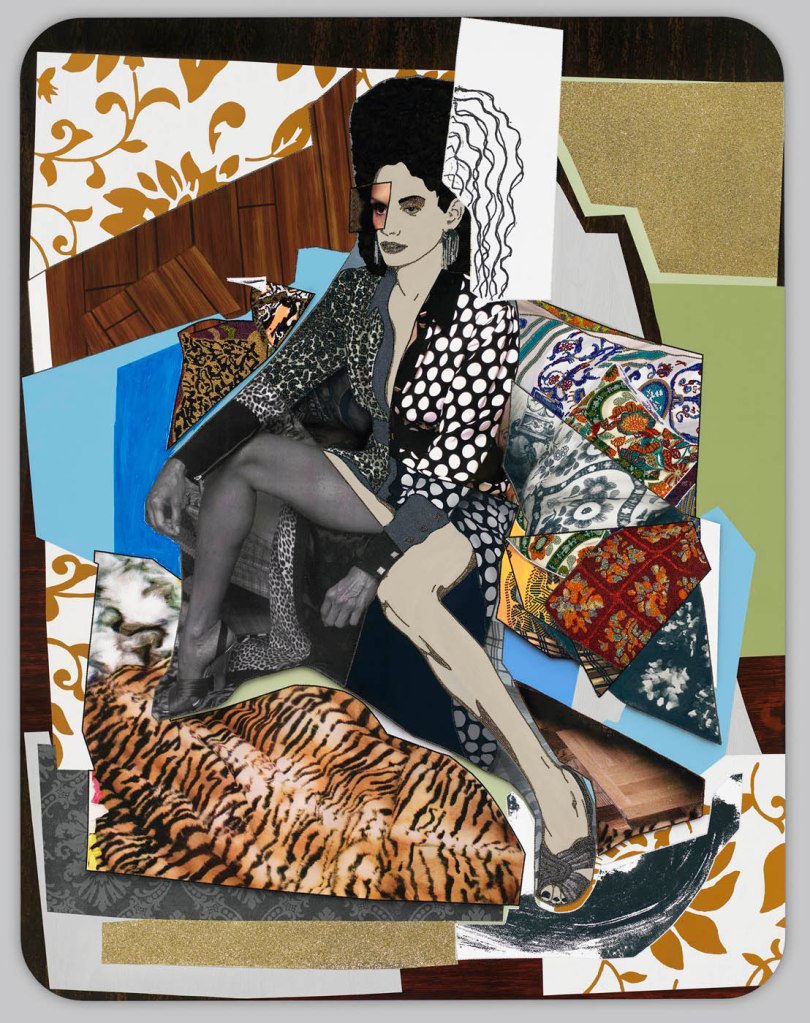

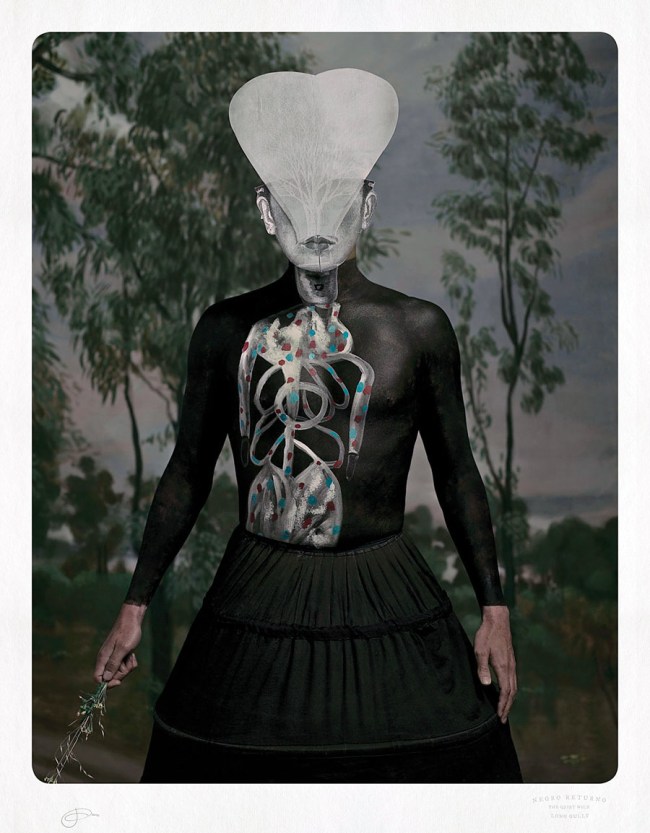

The varied afterlife of the femme fatale: contemporary (counter-)images

Nowadays there is no single, unambiguous vision of the femme fatale, and the counter-images are equally multifaceted. Artists examine traces of the clichéd concept, explore representations and adaptations of the femme fatale trope, reflect on the male gaze in art history, and consider gender identity, female physicality and sexuality from intersectional and queer feminist perspectives. In Jenevieve Aken’s work, for example, the ‘super femme fatale’ is a positively connoted, liberated (identificatory) figure who defies the constraints of a patriarchal society. Nan Goldin’s photographs show drag queens appropriating iconic figures who have long been stylised as femmes fatales, such as Marilyn Monroe or Madonna. In a similar way, Goldin’s video works place the mythological figures of Salome and the Sirens in new contexts. Betty Tompkins’ series of images highlight the fact that female sexuality is still being demonised today; her complex combinations of words and images reveal the continuities in a violently patriarchal art field, up to and including the #MeToo movement. Important counterpoints are also provided by artists such as Mickalene Thomas and Zandile Tshabalala, who deal with female beauty, physicality and sexuality through critical engagement with a white art canon.

Text from the Hamburger Kunsthalle website

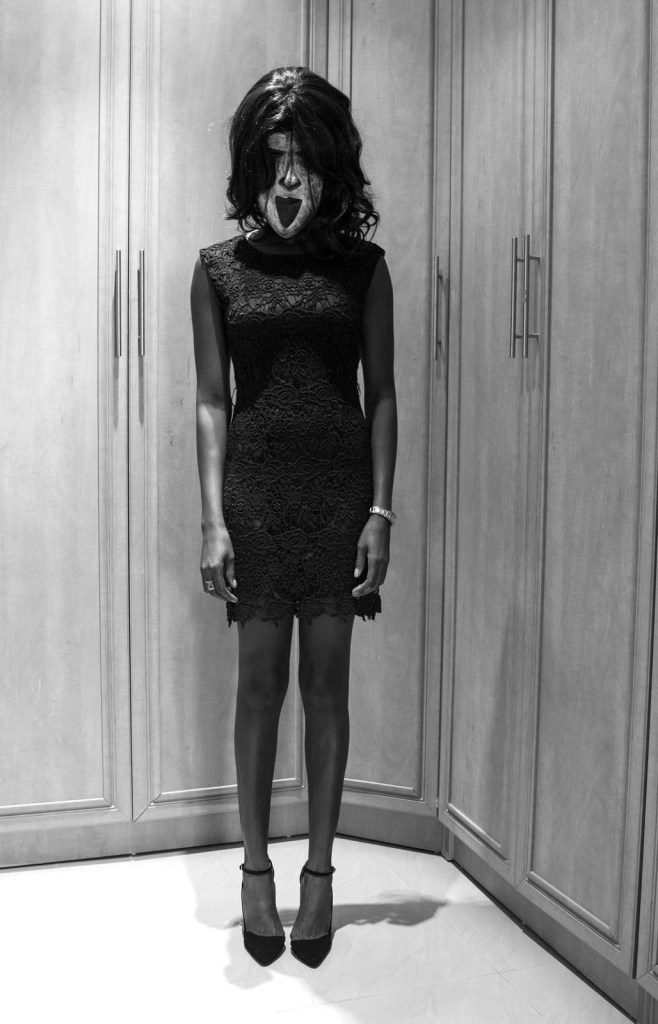

Insectionality / Black Feminisms

Black women who are simply portrayed leading their everyday lives, without being reduced to their suffering or racial trauma experiences – unfortunately, this is a rarely shown image. The woman in the painting Lounging 1: G fabulous [below] is unmistakably depicted as Black. Next to her is a soft bathrobe. She is relaxing in a room with pompous wallpaper, on a fluffy carpet in front of a glamorous couch. Her material possessions, together with the fact that she is resting, are markers of luxury. For in the system of white supremacy, Black women are expected to live in a “hustle and grind culture”, where they continually have to prove themselves and try twice as hard as their white counterparts. Resting as a form of resistance is thus understood as a counter-movement and a radical political practice against social injustice. The slogan “rest is resistance” became famous on social media through the organisation The Nap Ministry. Though the woman in Lounging 1: G fabulous is nude, she is not depicted in a voyeuristic or sexist way – as Black women are in many works of European and American art history. The power of the gaze no longer lies with a voyeur, but in this case emanates from the sitter. Despite her nakedness, the image is in no way about conforming to a male gaze. The woman in the work simply shows herself as she is.

Likewise, Jenevieve Aken’s series The Masked Woman [below] is about self-fulfilment. Her self-portrayals show everyday scenes from the life of a woman in Nigeria who has decided against the role of the subordinate housewife. Instead, she leads a contented solo life as a “super femme fatale” – as she writes herself. A decision for a lifestyle that is not nearly as socially prestigious as living in a bourgeois nuclear family. Both works create new self-designations and show how extensive and multi-layered Black female identities are.

Doing Feminism – With Art! booklet to the exhibition

Zandile Tshabalala (South African, b. 1999)

Lounging 1: G fabulous

2021

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

120 × 200cm

Courtesy Privatsammlung Saskia Draxler und Christian Nagel

© Zandile Tshabalala / Privatsammlung Köln / Galerie Nagel Draxler Berlin / Köln / München

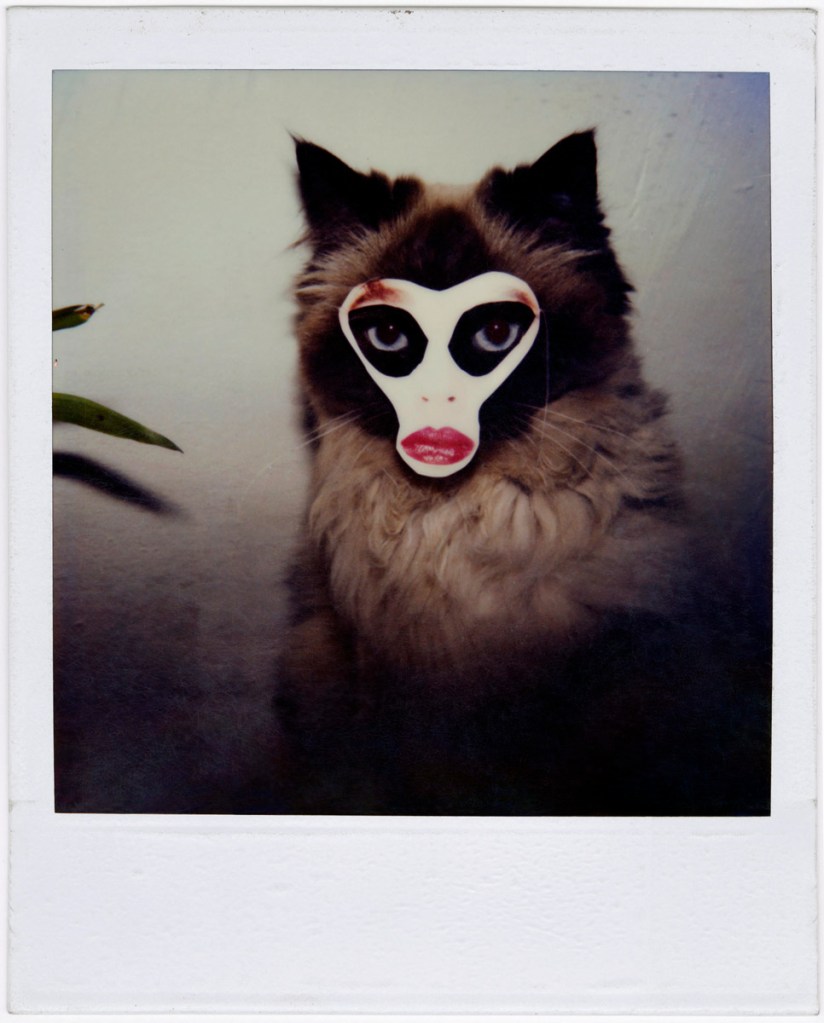

Jenevieve Aken (Nigeria, b. 1989)

The Masked Woman

2014

Photographs seven-part series

Courtesy of the artist

© Jenevieve Aken

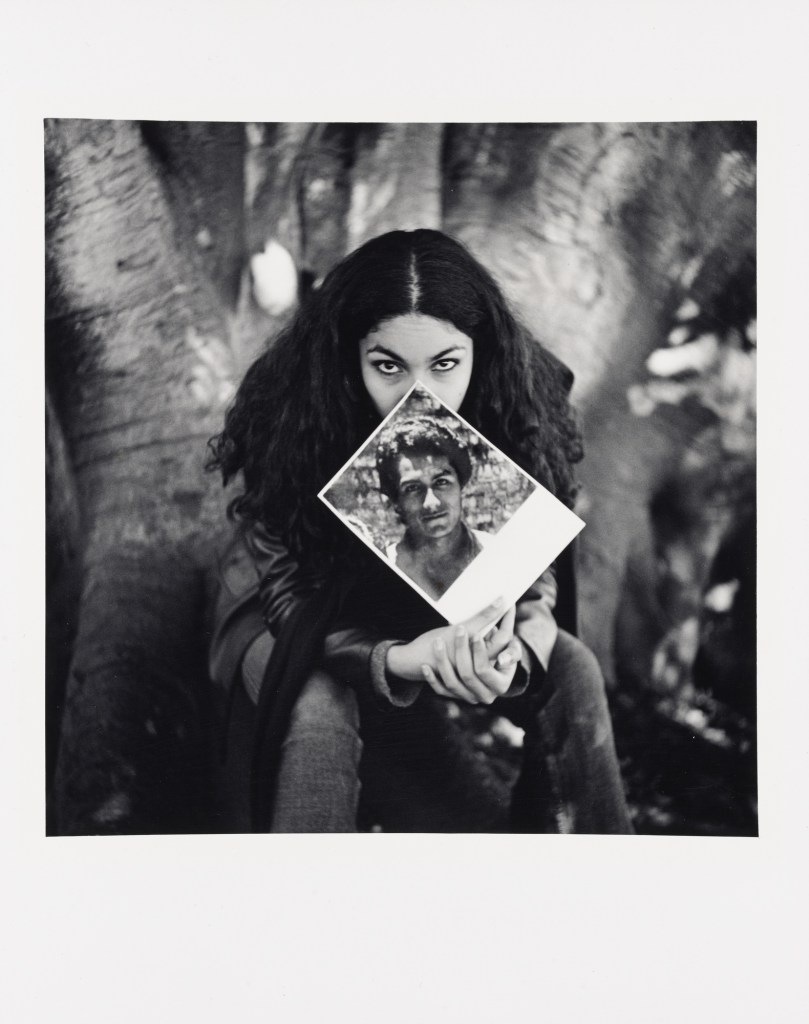

The Masked Woman is a self-portrait series that explores representation of gender in Nigeria society through a performative lens. It attempts to avert the overarching male gaze by facing it head on with the artist’s own actions and choices. The images portray the solitary lifestyle of the “super femme fatale” character, choosing to achieve pleasure and contentment through self-fulfilment that not dictated by the subservient role as a house wife or defined through a man’s affection. While depicting a confident and sexually free woman, the subject’s mask and body language also suggest a nuanced tone of isolation which speaks to her stigmatization in a society that has limiting and strictly defined roles of what the proper woman should be. By diverting the status-quo and exercising freedom of choice, such women are perceived as extreme, eccentric, and outside of polite society in Nigeria. The series personifies a growing number of independent, professional women in Nigeria who at once assert their autonomy while also being ostracized by cultural norms. Rather than waiting for the narrative to be told from the outside, I choose to give birth to my own freedom, in hope that it will inspires other women in Nigeria to express their independence and free-will.

Jenevieve Aken. “The Masked Woman,” on the Jenevieve Aken website Nd [Online] Cited 04/03/2023

Jenevieve Aken (born 1989) is a Nigerian documentary, self-portrait and urban portrait photographer, focusing on cultural and social issues. Her work often revolves around her personal experiences and social issues surrounding gender roles. …

The Masked Woman

This is a black and white, self-portrait series meant to depict women and their social roles in Nigerian culture. The images depict the peace and self-fulfilment of a woman without the stigmatised overarching views of women in a Nigerian culture. The images also explore how women can feel constrained by the stereotypes of what a “proper women” should act like in society. These photos are meant to exemplify women who have broken these stigmas but feel isolated by the norms of the society. In this series Aken hopes to inspire Nigerian women to practice their freedom regardless of external stereotypes.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Myth & Religion

Lilith

Lilith was the first in various respects. Apparently, not only the Adam’s first wife who lived equally with him in the Garden of Eden, but also the first feminist, because she simply flew away when he demanded submission from her. Conveniently, as recorded in older Babylonian accounts, she was a hybrid being and had wings. Others imagined her as a hybrid between a woman and a serpent. Unfortunately, as a woman who was sexually independent, she evidently did not have a good image among the patriarchy, for she was said to bring sickness and death, to seduce and kill men, be infertile and kill newborn babies with the poisonous milk from her breast. In Jewish feminist theology, however, she stands for wisdom and strength because she was the first being to convince God to tell her his name – granting her unlimited power.

Judith

Judith is described in the Old Testament as a beautiful, wealthy and, besides this, pious widow who defended her Jewish homeland against the seizure by the Assyrian general Holofernes. She saved her mountain village of Bethulia by trusting in God completely and impressing Holofernes with her charm and wise speeches, so that she was able to sneak into his confidence. On the 40th day of the occupation, there was a celebration in Judith’s honour at which Holofernes got so drunk that Judith was able to cut off his head with her sword. The Assyrians left in horror and Judith retired to her quiet widowhood. Thanks to her deed, the overall trust in God was so great that no one could shake the Israeli community for a long time. In the Western world, the figure of Judith was often used as a motif in art, from the nineteenth century onwards with an increasingly eroticising, orientalising and anti-Semitic undertone. Judy Chicago, on the other hand, showed her as a feminist icon in her famous installation Dinner Party in the 1970s.

Medusa

Today, Medusa is mainly known for her extravagant hairstyle consisting exclusively of live snakes. How did this come about? There exist several variants of her story in Greek mythology, but the best known says that Pallas Athena happened to witness her husband Poseidon raping the beautiful Medusa. Instead of helping her and imprisoning him, she disfigured the rape victim forever by conjuring up: snakes on her head, pigs’ teeth, scaly skin, arms made of bronze and a tongue hanging out. Anyone who caught sight of her would henceforth turn to stone in horror. The artistic representation of the terrifying snake’s head has fascinated artists since ancient times, and even today it plays a role in films, games or even the logo of the Versace fashion label. It appears to be the perfect antithesis to the Western ideal of women – evil, tough and ugly – and, according to some research, could represent the transition from matriarchy to patriarchy, which went hand in hand with the demonisation of female strength.

Salome