Exhibition dates: 25th November 2011 – 4th March 2012

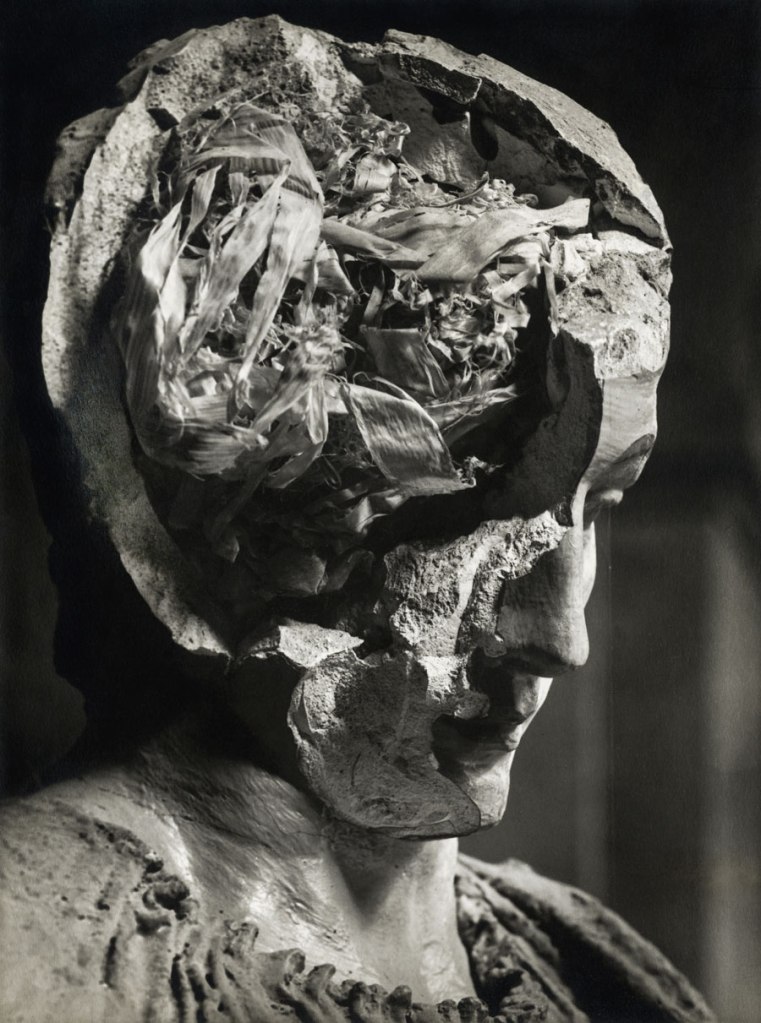

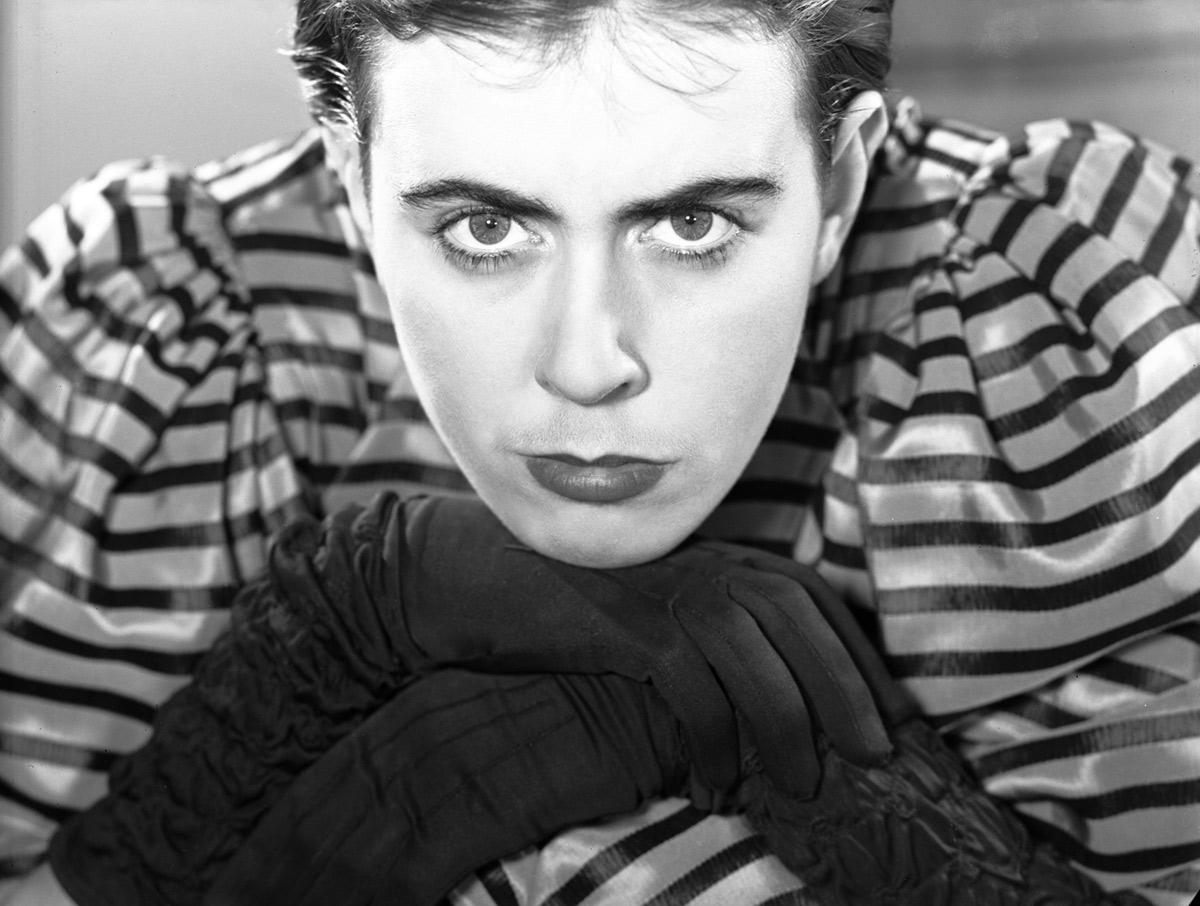

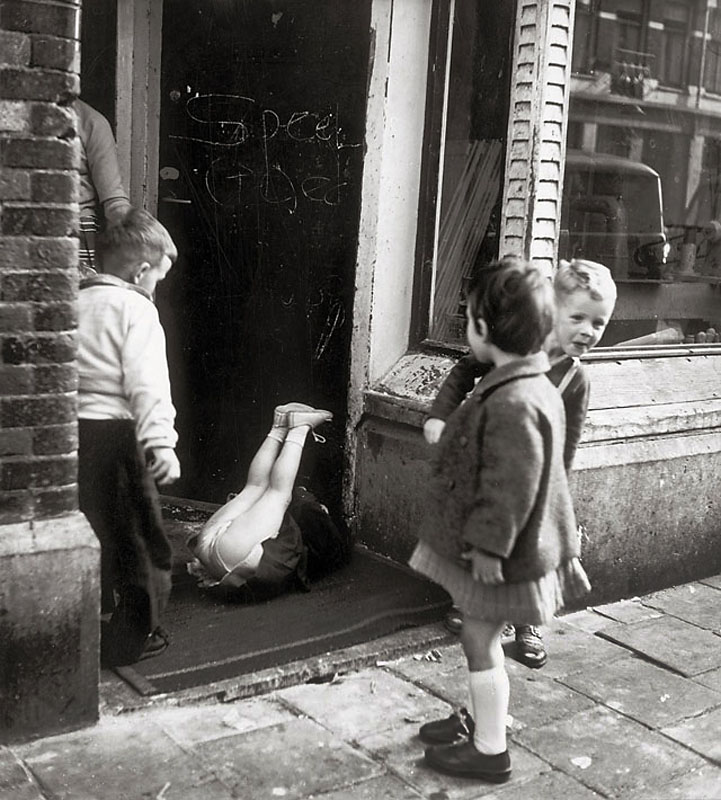

Irene Bayer (American, 1898-1991)

No title (Man on stage)

c. 1927

Gelatin silver photograph

Printed image 10.6 h x 7.6 w cm

Purchased 1983

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

This is one of the best exhibitions this year in Melbourne bar none. Edgy and eclectic the work resonates with the viewer in these days of uncertainty: THIS should have been the Winter Masterpieces exhibition!

The title of the exhibition, The mad square (Der tolle Platz) is taken from Felix Nussbaum’s 1931 painting of the same name where “the ‘mad square’ is both a physical place – the city, represented in so many works in the exhibition, and a reference to the state of turbulence and tension that characterises the period.” The exhibition showcases how artists responded to modern life in Germany in the interwar years, years that were full of murder and mayhem, putsch, revolution, rampant inflation, starvation, the Great Depression and the rise of National Socialism. Portrayed is the dystopian, dark side of modernity (where people are the victims of a morally bankrupt society) as opposed to the utopian avant-garde (the prosperous, the wealthy), where new alliances emerge between art and politics, technology and the mass media. Featuring furniture, decorative arts, painting, sculpture, collage and photography in the sections World War 1 and the Revolution, Dada, Bauhaus, Constructivism and the Machine Aesthetic, Metropolis, New Objectivity and Power and Degenerate Art, it is the collages and photographs that are the strongest elements of the exhibition, particularly the photographs. What a joy they are to see.

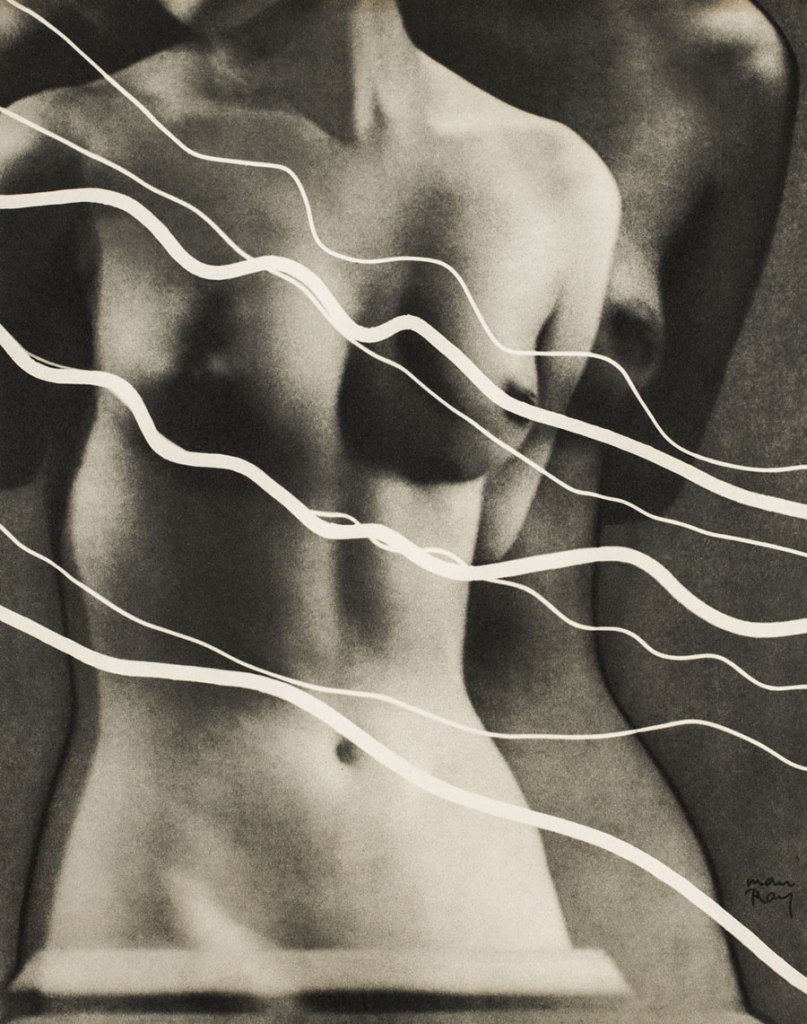

There is a small 2″ x 3″ contact print portrait of Hanna Höch by Richard Kauffmann, Penetrate yourself or: I embrace myself (1922) that is an absolute knockout. Höch is portrayed as the ‘new women’ with short bobbed hair and loose modern dress, her self-image emphasised through a double exposure that fragments her face and multiplies her hands, set against a contextless background. The ‘new women’ fragmented and broken apart (still unsure of herself?). The photograph is so small and intense it takes your breath away. Similarly, there is the small, intimate photograph No title (Man on Stage) (c. 1927) by Irene Bayer (see above) that captures performance as ‘total art’, a combination of visual arts, dance, music, architecture and costume design. In contrast is a large 16 x 20″ photograph of the Bauhaus balconies (1926) by László Moholy-Nagy (see below) where the whites are so creamy, the perspective so magnificent.

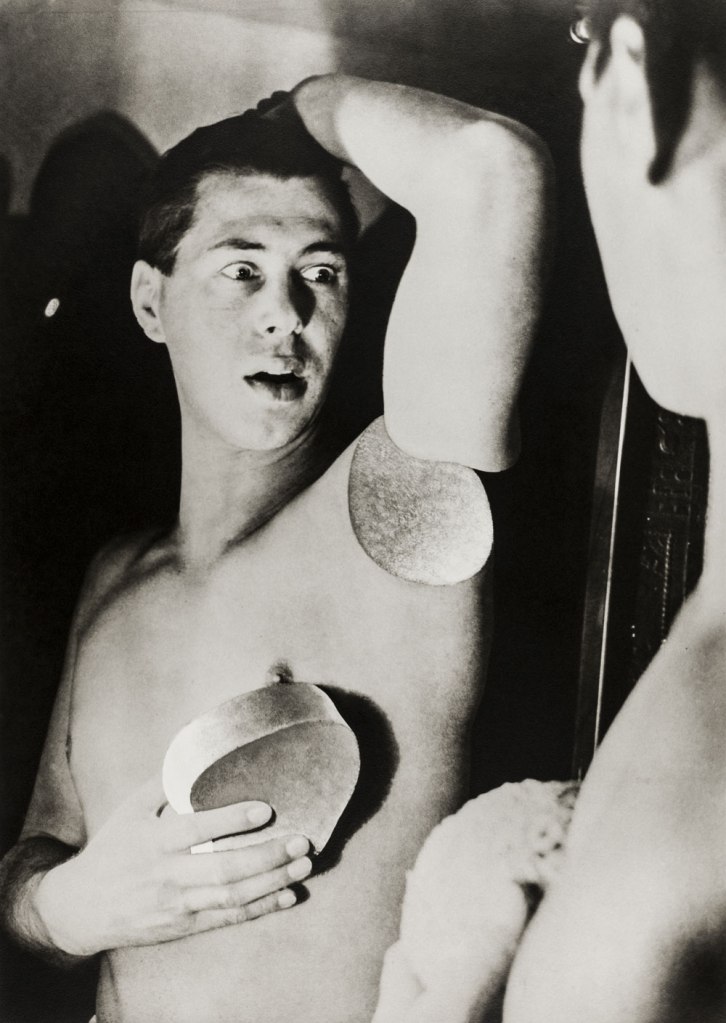

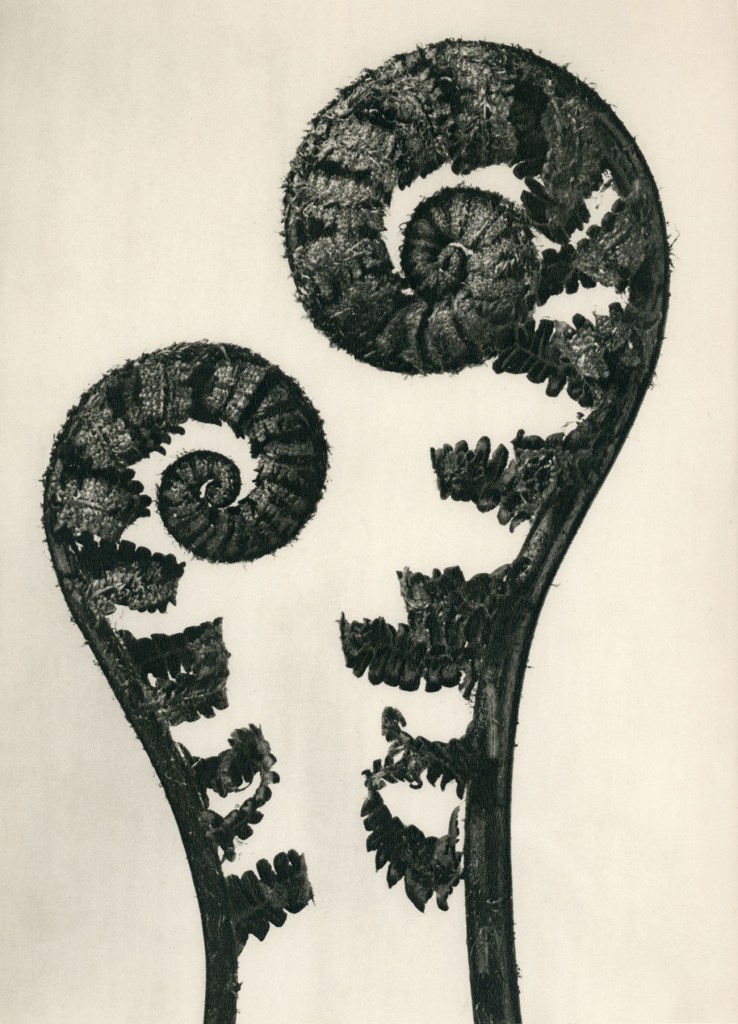

No title (Metalltanz) (c. 1928-1929) by T. Lux Feinenger, a photographer that I do not know well, is an exceptional photograph and print. Again small, this time dark and intense, the image features man as dancer performing gymnastics in front of reflective, metal sculptures. The metal becomes an active participant in the Metalltanz or ‘Dance in metal’ because of its reflective qualities. The print, from the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles is luminous. In fact all the prints from the Getty in this exhibition are of the most outstanding quality, a highlight of the exhibition for me. Another print from the Getty that features metal and performance is Untitled (Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet) by T Grill c. 1926-1927 (see below) where the spiral costume becomes an extension of the body, highlighting its form. Also highlighting form, objectivity and detachment is a wonderful 3 x 5″ photograph of the New Bauhaus Building, Dessau (1926) by Lucia Moholy from the Getty collection, the first I have ever seen in the flesh by this artist. Outstanding.

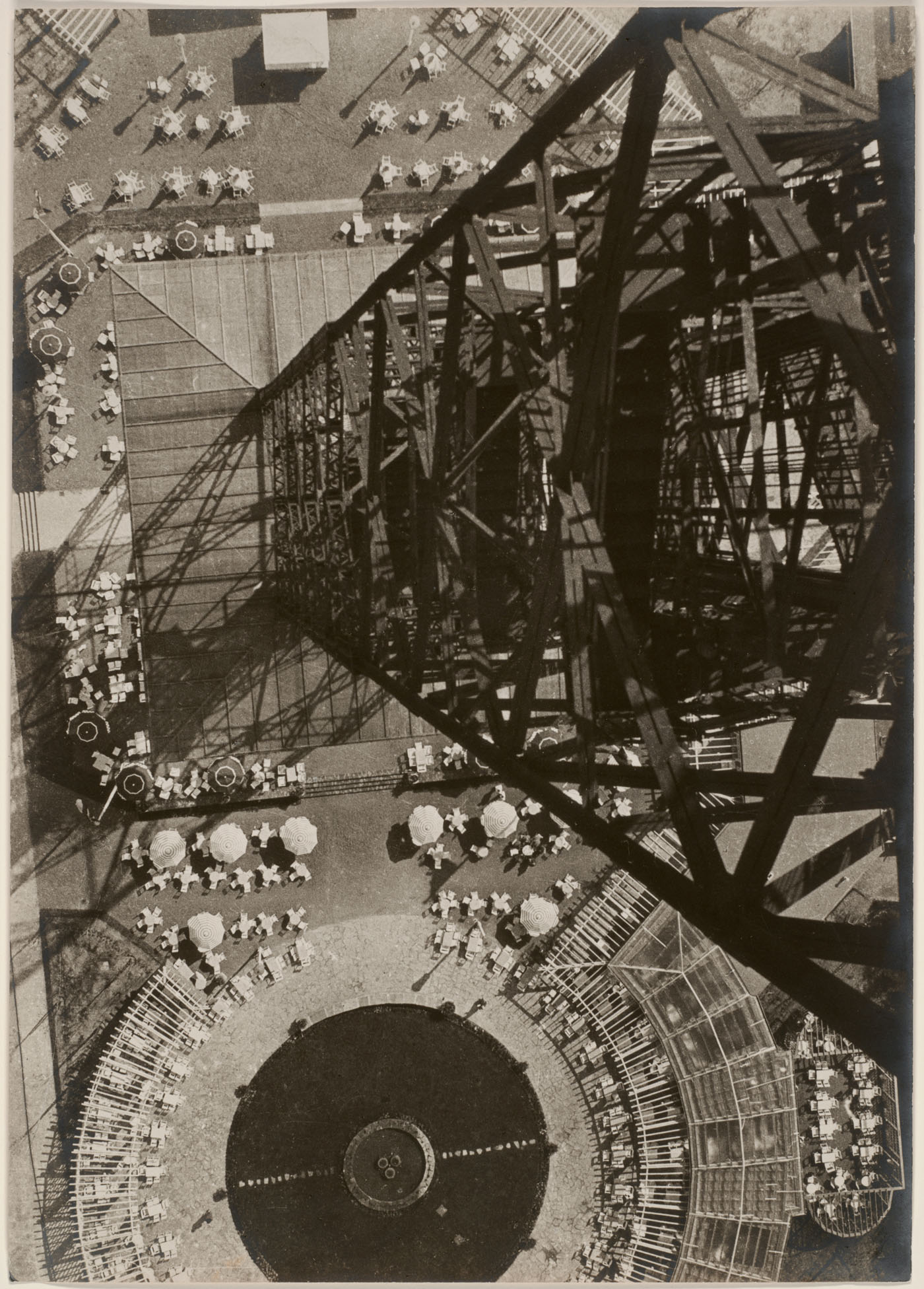

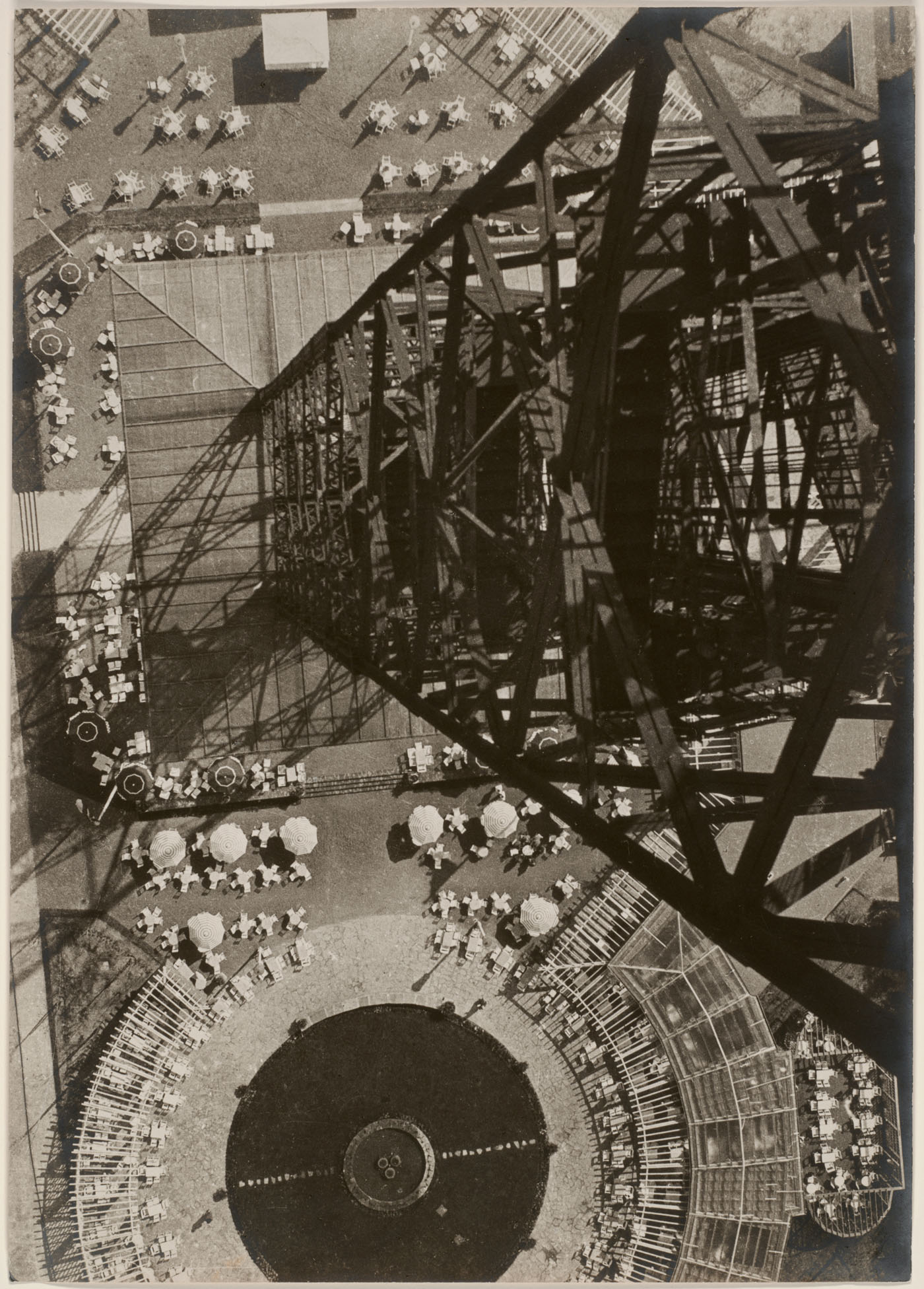

Following, we have 4 photograms by Lucia’s husband, László Moholy-Nagy which display formalist experimentation “inspired by machine aesthetic, exploring a utopian belief that Constructivism and abstract art could play a role in the process of social reform.” Complimenting these photograms is a row of six, yes six! Moholy-Nagy including Dolls (Puppen) 1926-1927 (Getty), The law of the series 1925 (Getty), Lucia at the breakfast table 1926 (Getty), Spring, Berlin 1928 (George Eastman House), Berlin Radio Tower 1928 (Art Institute of Chicago) and Light space modulator 1930 (Getty). All six photographs explore the fascinating relationship between avant-garde art and photography, between they eye and perspective, all the while declaiming what Moholy-Nagy called the “new vision”; angles, shadows and geometric patterns that defy traditional perspective “removing the space from associations with the real world creating a surreal, disjointed image.” This topographic mapping flattens perspective in the case of the Berlin radio tower allowing the viewer to see the world in a new way.

Finally two groups of photographs that are simply magnificent.

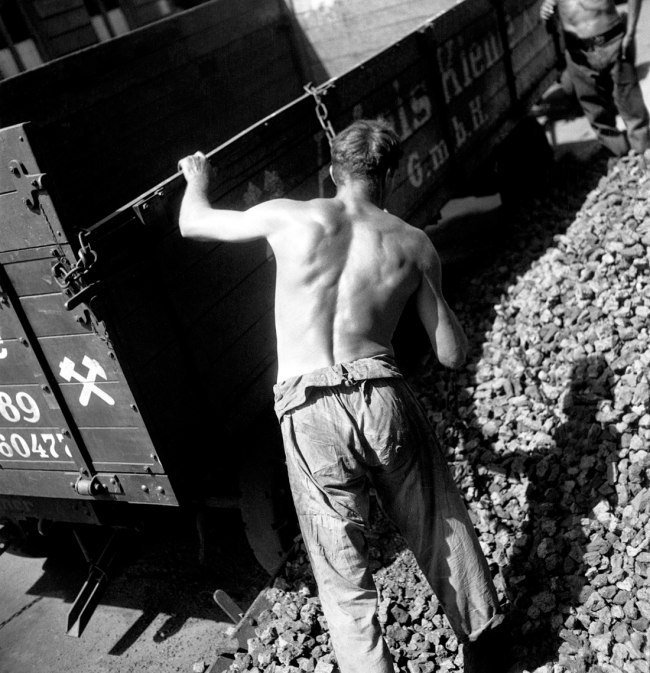

First 8 photographs in a row that focus on the order and progressive nature of the modern world, the inherent beauty of technology captured in formalist studies of geometric forms. The prints range from soft pictorialist renditions to sharp clarity. The quality of the prints is amazing. Artists include the wonderful E. O. Hoppé, Albert Renger-Patzsch (an outstandingly beautiful photograph, Harbour with cranes 1927 that is my favourite photograph in the exhibition, see below), Two Towers 1937-1938 by Werner Mantz and some early Wolfgang Sievers before he left Germany for Australia in 1938 (Blast furnace in the Ruhr, Germany 1933, see below). These early Sievers are particularly interesting, especially when we think of his later works produced in Australia. Lucky were many artists who survived in Germany or fled from Nazi persecution at the last moment, including John Heartfield who relocated to Czechoslovakia in 1933 and then fled to London in 1938 and August Sander whose life and work were severely curtailed under the Nazi regime and whose son died in prison in 1944 near the end of his ten year sentence (Wikipedia).

August Sander. Now there is a name to conjure with. The second magnificent group are 7 photographs that are taken from Sander’s seminal work People of the 20th Century. All the photographs have soft, muted tones of greys with no strong highlights and, usually, contextless backgrounds. The emphasis is on archetypes, views of people who exist on the margins of society – circus performers, bohemians, artists, the unemployed and blind people. In all the photographs there is a certain frontality (not necessarily physical) to the portraits, a self consciousness in the sitter, a wariness of the camera and of life. This self consciousness can be seen in the two photographs that are the strongest in the group – Secretary at West German radio in Cologne, 1931 and Match seller 1927 (see below).

There is magic here. Her face wears a somewhat quizzical air – questioning, unsure, vulnerable – despite the trappings of affluence and fashionability (the smoking of the cigarette, the bobbed hair). He is wary of the camera, his face and hands isolated by Sander while the rest of his body falls into shadow. His right hand is curled under, almost deformed, his shadow falling on the stone at right, the only true brightness in this beautiful image the four boxes of matches he clutches in his left hand: as Sander titles him ironically, The Businessman.

Working as I do these days with lots of found images from the 1940s-1960s that I digitally restore to life, I wonder what happened to these people during the dark days of World War 2. Did they survive the cataclysm, the drop into the abyss? I want to know, I want to reach out to these people to send them good energy. I hope that they did but their wariness in front of the camera, so intimately ‘taken’ by Sander, makes me feel the portent of things to come. How differently we see images armed with the hindsight of history!

In conclusion, this is a fantastic exhibition that will undoubtedly be in my top ten of the year for Melbourne in 2011.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Michael Thorneycroft for his help and The National Gallery of Victoria for allowing me to publish the accredited photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Felix Nussbaum (German, 1904 – after September 1944)

The mad square (Der tolle Platz)

1931

Oil on canvas

97 x 195.5cm

Berlinische Galerie

Public domain

László Moholy-Nagy (American born Hungary, 1895-1946)

Berlin Radio Tower

1928

Gelatin silver print

36 × 25.5cm

Julien Levy Collection, Special Photography Acquisition Fund

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Over the winter and spring of 1927-1928, Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy took a series of perhaps nine views looking down from the Berlin Radio Tower, one of the most exciting new constructions in the German capital. Moholy had already photographed the Eiffel Tower in Paris from below, looking up through the tower’s soaring girders. In Berlin, however, Moholy turned his camera around and pointed it straight down at the ground. This plunging perspective showed off the spectacular narrowness of the Radio Tower, finished in 1926, which rose vertiginously to a height of 450 feet from a base seven times smaller than that of its Parisian predecessor (which opened in 1889). Moholy attached exceptional importance to this, his boldest image: he hung it just above his name in a room devoted to his work at the Berlin showing of Film und Foto, a mammoth traveling exhibition that he had helped to prepare. Moholy also chose this view and one other to offer Julien Levy, the pioneering art dealer, when Levy visited him in Berlin in 1930. The following year the pictures went on view at the Levy Gallery in New York, in Moholy’s first solo exhibition of photographs.

Text from the Art Institute of Chicago website

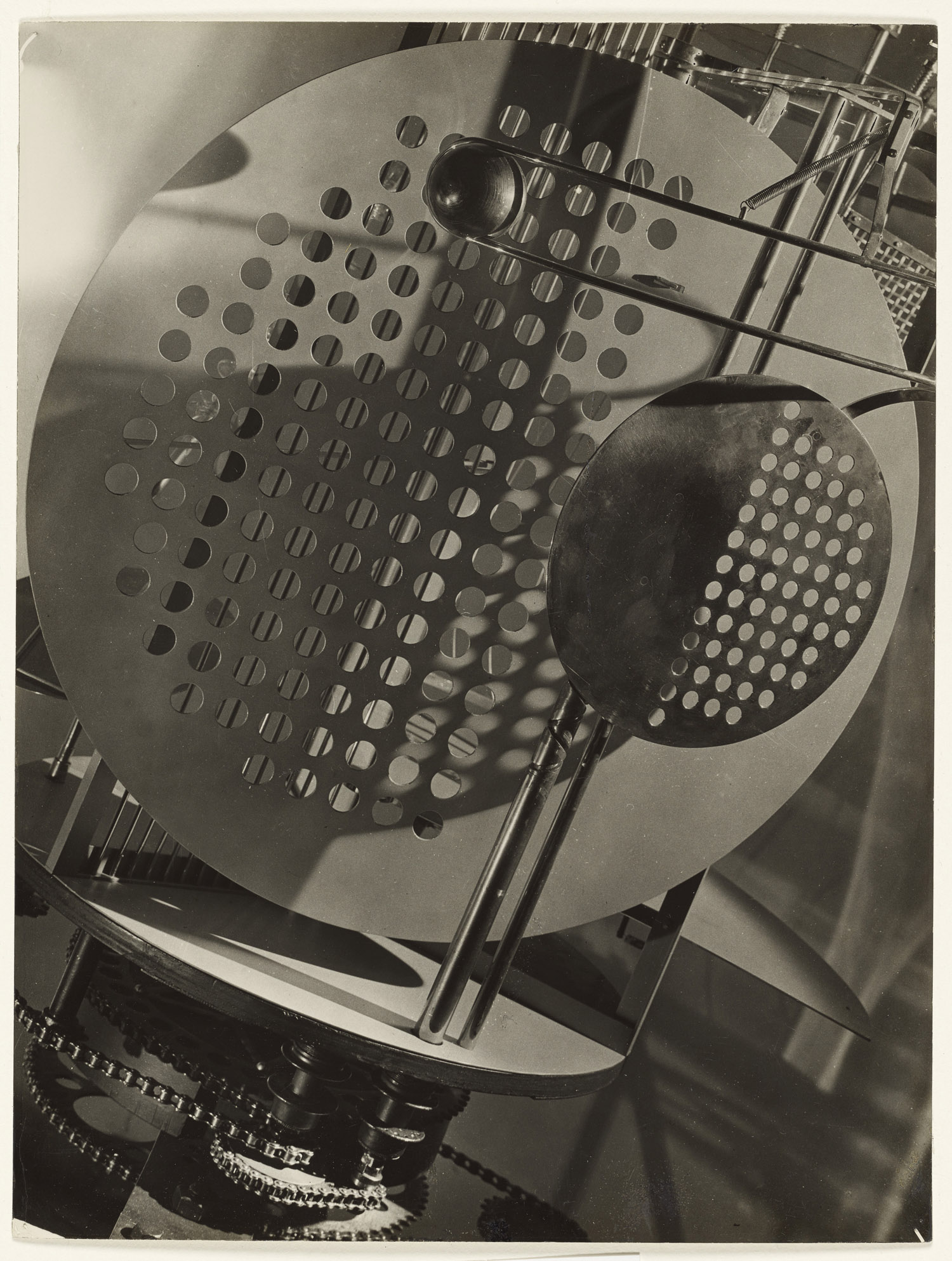

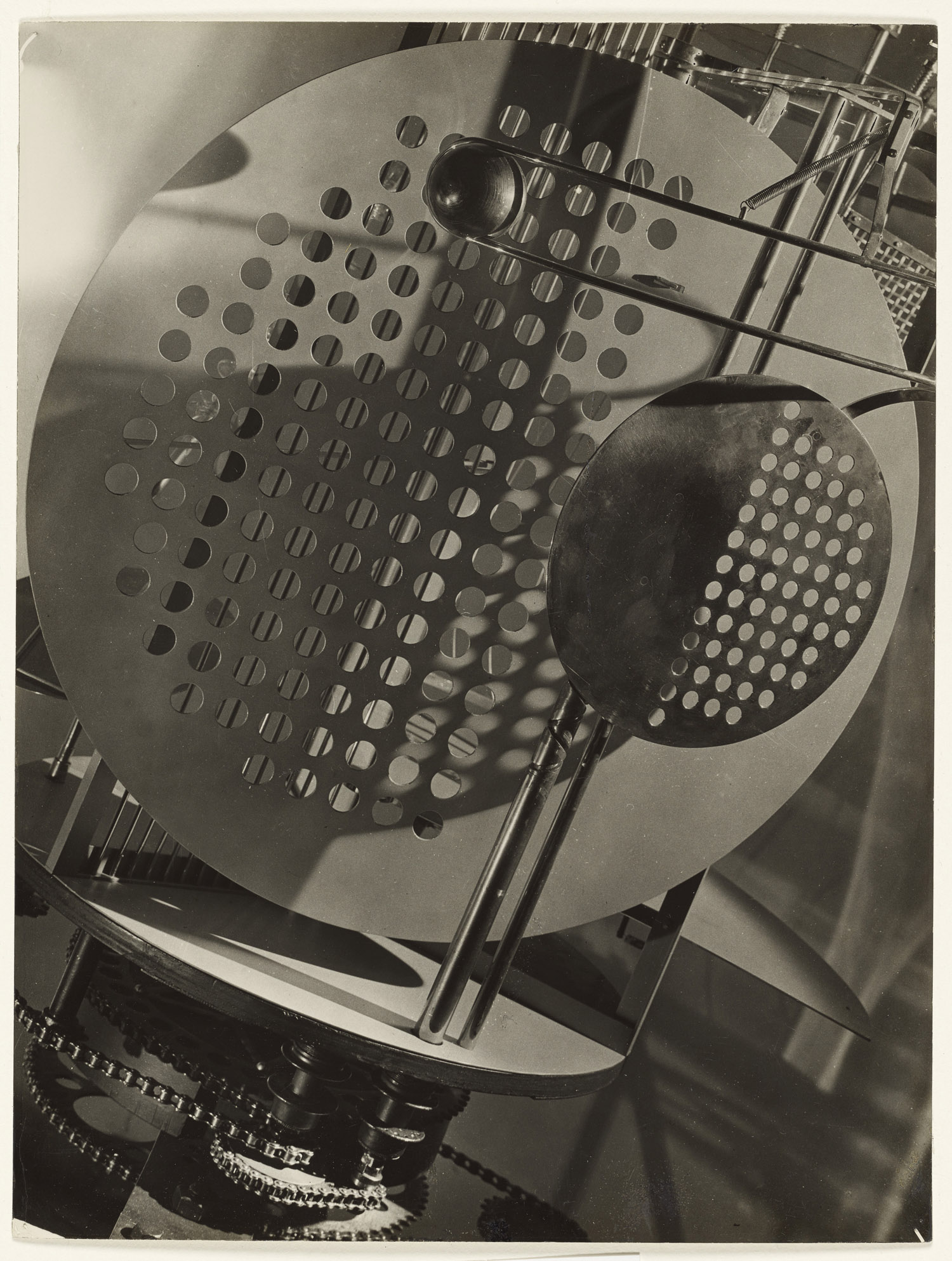

László Moholy-Nagy (American born Hungary, 1895-1946)

Das Lichtrequisit (The light prop)

1930

Gelatin silver print

24 × 18.1cm (9 7/16 × 7 1/8 in.)

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© 2014 Estate of László Moholy-Nagy / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Light-Space Modulator is the most spectacular and complete realisation of László Moholy-Nagy’s artistic philosophy. Machine parts and mechanical structures began to appear in his paintings after his emigration from Hungary, and they are also seen in the illustrations he selected for the 1922 Buch neuer Künstler (Book of new artists), which includes pictures of motorcars and bridges as well as painting and sculpture. Many contemporary artists incorporated references to machines and technology in their work, and some, like the Russian Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin, even designed plans for fantastic structures, such as the ambitious Monument to the Third International, a proposed architectural spiral of glass and steel with moving tiers and audiovisual broadcasts. (See Tatlin’s Tower.)

In the Light-Space Modulator, Moholy-Nagy was able to create an actual working mechanism. Although he censured capitalism’s inhumane use of technology, he believed it could be harnessed to benefit mankind and that the artist had an important role in accomplishing this. Moholy had made preliminary sketches for kinetic sculptures as early as 1922 and referred to the idea for a light machine in his writings, but it was not until production was financed by an electric company in Berlin in 1930 that this device was built, with the assistance of an engineer and a metalsmith. It was featured at the Werkbund exhibition in Paris the same year, along with the short film Light Display Black-White-Gray, made by Moholy-Nagy to demonstrate and celebrate his new machine.

The Light-Space Modulator is a Moholy-Nagy painting come to life: mobile perforated disks, a rotating glass spiral, and a sliding ball create the effect of photograms in motion. With its gleaming glass and metal surfaces, this piece (now in the collection of the Busch-Reisinger Museum at Harvard University) is not only a machine for creating light displays but also a sculptural object of beauty, photographed admiringly by its creator.

Katherine Ware, László Moholy-Nagy, In Focus: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1995), 80 © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum

Albert Renger-Patzsch (American born Hungary, 1895-1946)

Harbour with crane

c. 1927

Gelatin silver photograph

Printed image 22.7 h x 16.8 w cm

Purchased 1983

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Wolfgang Sievers (Germany 1913 – Australia 2007)

Blast furnace in the Ruhr, Germany

1933

Gelatin silver photograph

27.5 h x 23 w cm

Purchased 1988

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

The Ruhr region was at the centre of the German acceleration of industry in pre-war Germany, with rapid economic growth creating a heavy demand for coal and steel. In keeping with Modernist trends in photography, Sievers shot this blast furnace – the mechanism that transforms ore into metal – from an unusual, dynamic angle. It dominates the frame, appearing menacing and strange. Despite being imprisoned and beaten by the Gestapo, Sievers studied and taught at a progressive private art school until graduation in 1938. In that year he escaped Germany after being called up for military service, ending up in Australia.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Match seller

1927

From the portfolio People of the 20th century, IV Classes and Professions, 17 The Businessman

Robert Wiene, Director (German 1873-1938)

Still from from the Cabinet of Dr Caligari

1919

5 min excerpt, 35mm transferred to DVD, Black and White, silent, German subtitles

Courtesy Transit Film GmbH

Production still courtesy of the British Film Institute and Transit Film GmbH

Felix H Man (German, 1893-1985)

Luna Park

1929

Gelatin silver photograph

18.1 x 24cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased, 1987

© Felix H Man Estate

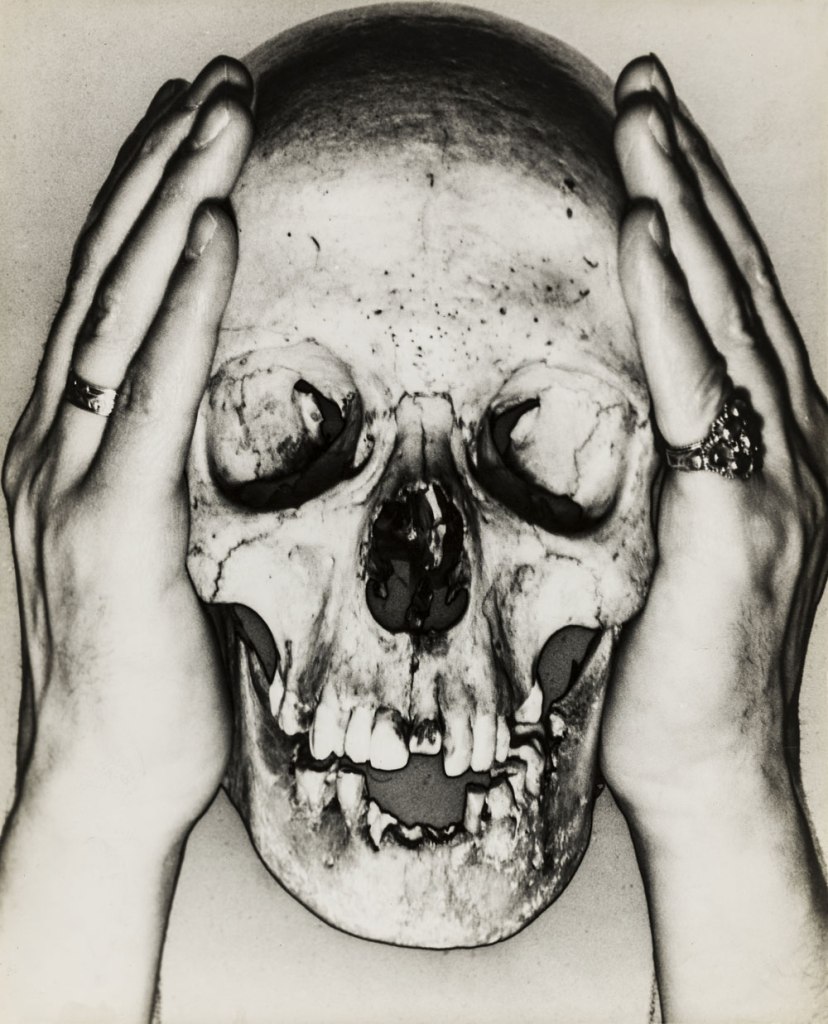

Hannah Höch (German, 1889-1978)

Love

1931

From the series Love

Photomontage

21.8 x 21cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased, 1983

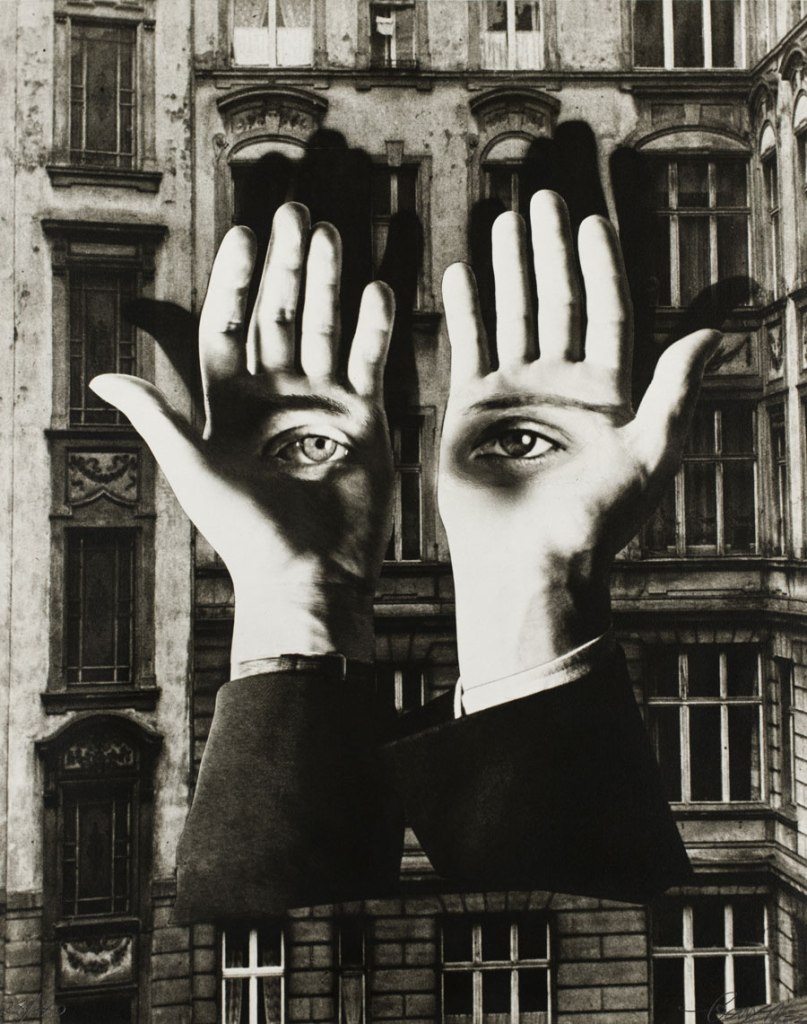

Hannah Höch made some of the most interesting Dada collages and photomontages, including Love, an image of two strange composite female. Höch’s technique of pasting images together from magazine clippings and advertisements was a response to the modern era of mass media, and a way of criticising the bourgeois taste for ‘high art’. In many of her works, Höch explores the identity and changing roles of women in modern society.

The Mad Square takes its name from Felix Nussbaum’s 1931 painting which depicts Berlin’s famous Pariser Platz as a mad and fantastic place. The ‘mad square’ is both a physical place – the city, represented in so many works in the exhibition, and a reference to the state of turbulence and tension that characterises the period. The ‘square’ can also be a modernist construct that saw artists moving away from figurative representations towards increasingly abstract forms.

The exhibition features works by Max Beckman, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Christian Schad, Kurt Schwitters and August Sander. This group represents Germany’s leading generation of interwar artists. Major works by lesser known artists including Karl Hubbuch, Rudolf Schlichter and Hannah Höch are also presented in the exhibition in addition to works by international artists who contributed to German modernism.

The Mad Square brings together a diverse and extensive range of art, created during one of the most important and turbulent periods in European history, offering new insights into the understanding of key German avant‐garde movements including – Expressionism, Dada, Bauhaus, Constructivism, and New Objectivity were linked by radical experimentation and innovation, made possible by an unprecedented freedom of expression.

World War 1 and the Revolution

The outbreak of war in 1914 was met with enthusiasm by many German artists and intellectuals who volunteered for service optimistically hoping that it would bring cultural renewal and rapid victory for Germany. The works in this section are by the generation of artists who experienced war first hand. Depictions of fear, anxiety and violence show the devastating effects of war – the disturbing subjects provide insight into tough economic conditions and social dysfunction experienced by many during the tumultuous early years of the Weimar Republic following the abdication of the Kaiser

Dada

The philosophical and political despair experienced by poets and artists during World War 1 fuelled the Dada movement, a protest against the bourgeois conception of art. Violent, infantile and chaotic, Dada took its name from the French word for a child’s hobbyhorse or possibly from the sound of a baby’s babble. Its activities included poetry readings and avant‐garde performances, as well as creating new forms of abstract art that subverted all existing conditions in western art. Though short‐lived, in Germany the Dada movement has profoundly influenced subsequent developments in avant-garde art and culture. The impact of the Dada movement was felt throughout Europe – and most powerfully in Germany from 1917-21.

Bauhaus

The Bauhaus (1919‐1933) is widely considered as the most important school of art and design of the 20th century, very quickly establishing a reputation as the leading and most progressive centre of the international avant‐garde. German architect Walter Gropius founded the school to do away with traditional distinctions between the fine arts and craft, and to forge an entirely new kind of creative designer skilled in both the conceptual aesthetics of art and the technical skills of handicrafts. The Bauhaus was considered to be both politically and artistically radical from its inception and was closed down by the National Socialists in 1933

Constructivism and the Machine Aesthetic

Having emerged in Russia after World War I, Constructivism developed in Germany as a set of ideas and practices that experimented with abstract or non-representational forms and in opposition to Expressionism and Dada. Constructivists developed works and theories that fused art and with technology. They shared a utopian belief in social reform, and saw abstract art as playing a central role in this process.

Metropolis

By the 1920s Berlin has become the cultural and entertainment capital of the world and mass culture played an important role in distracting a society traumatised by World War 1, the sophisticated metropolis provided a rich source of imagery for artists, it also come to represent unprecedented sexual and personal freedom. In photography modernity was emphasised by unusual views of the metropolis or through the representation of city types. The diverse group of works in this section portray the uninhibited sense of freedom and innovation experienced by artists throughout Germany during the 1920s

New Objectivity

By the mid 1920s, a new style emerged that came to be known as Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity. After experiencing the atrocities of World War 1 and the harsh conditions of life in postwar Germany, many artists felt the need to return to the traditional modes of representation with portraiture becoming a major vehicle of this expression, with its emphasis on the realistic representation of the human figure

Power and Degenerate Art

After the seizure of power by the National Socialists in 1933 modern artists were forbidden from working and exhibiting in Germany, with their works confiscated from leading museums and then destroyed or sold on the international art market. Many avant‐garde artists were either forced to leave Germany or retreat into a state of ‘inner immigration’.

The Degenerate art exhibition, held in Munich in 1937, represented the culmination of the National Socialists’ assault on modernism. Hundreds of works were selected for the show which aimed to illustrate the mental deficiency and moral decay that had supposedly infiltrated modern German art. The haphazard and derogatory design of the exhibition sought to ridicule and further discredit modern art. Over two million people visited the exhibition while in contrast far fewer attended the Great German art exhibition which sought to promote what the Nazis considered as ‘healthy’ art.

![Karl Grill (German active Donaueschingen, Germany 1920s) 'Untitled [Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet]' c. 1926-1927 Karl Grill (German active Donaueschingen, Germany 1920s) 'Untitled [Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet]' c. 1926-1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/grill-spiral-costume-from-the-triadic-ballet.jpg?w=650)

Karl Grill (German active Donaueschingen, Germany 1920s)

Untitled (Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet)

c. 1926-1927

Gelatin silver print

22.5 x 16.2cm

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In 1922, Oskar Schlemmer premiered his “Triadic Ballet” in Germany. He named the piece “Triadic” because it was literally composed of multiples of three: three acts, colours, dancers, and shapes. Concentrating on its form and movement, Schlemmer explored the body’s spatial relationship to its architectural surroundings. Although an abstract design, the spiral costume derived from the tutus of classical ballet.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Secretary at West German radio in Cologne

1931, printed by August Sander in the 1950s

From the portfolio People of the 20th century, III The woman, 17 The woman in intellectual and practical occupation

Gelatin silver photograph

29 x 22cm

Die Photographische Sammlung /SK Stiftung Kultur, August Sander Archiv, Cologne (DGPH1016)

© Die Photographische Sammlung /SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Timeline

1910

~ Berlin’s population doubles to two million people

1911

~ Expressionists move from Dresden to Berlin

1912

~ Social Democratic Party (SPD) the largest party in the Reichstag

1913

~ Expressionists attain great success with their city scenes

1914

~ World War I begins

~ George Grosz, Oskar Schlemmer, Otto Dix, Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Beckmann and Franz Marc enlist in the army

1915

~ Grosz declared unfit for service, Beckmann suffers a breakdown and Schlemmer wounded

1916

~ Marc dies in combat

~ Dada begins at Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich

1917

~ Lenin and Trotsky form the Soviet Republic after the Tzar is overthrown

1918

~ Richard Huelsenbeck writes a Dada manifesto in Berlin

~ Kurt Schwitters creates Merz assemblages in Hanover

~ Revolutionary uprisings in Berlin and Munich

~ Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicates and flees to Holland

~ Social Democratic Party proclaims the Weimar Republic

~ World War I ends

1919

~ Freikorps assassinates the Spartacist leaders, Karl Leibknecht and Rosa Luxemburg

~ Bauhaus established in Weimer by Walter Gropius

~ Cologne Dada group formed

~ Treaty of Versailles signed

1920

~ Berlin is the world’s third largest city after New York and London

~ Inflation begins in Germany

~ National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) founded

~ Kapp Putsch fails after right‐wing forces try to gain control over government

~ First International Dada fair opens in Berlin

1921

~ Hitler made chairman of the NSDAP

1922

~ Schlemmer’s Triadic ballet premiers in Stuttgart

~ Hyperinflation continues

1923

~ Hitler sentenced to five years imprisonment for leading the Beer Hall Putsch

~ Inflation decreases and a period of financial stability begins

1924

~ Hitler writes Mein Kampf while in prison

~ Reduction of reparations under the Dawes Plan

1925

~ New Objectivity exhibition opens at the Mannheim Kunsthalle

~ The Bauhaus relocates to Dessau

1926

~ Germany joins the League of Nations

1927

~ Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis released

~ Unemployment crisis worsens

~ Nazis hold their first Nuremburg party rally

1928

~ Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s The threepenny opera premieres in Berlin

~ Hannes Meyer becomes the second director of the Bauhaus

1929

~ Street confrontations between the Nazis and communists in Berlin

~ Young Plan accepted, drastically reducing reparations

~ Stock market crashes on Wall Street, New York

~ Thomas Mann awarded the Nobel Prize for literature

1930

~ Resignation of Chancellor Hermann Müller’s cabinet ending parliamentary rule

~ Minority government formed by Heinrich Brüning, leader of the Centre Party

~ Nazis win 18% of the vote and gain 95 seats in the National elections

~ Ludwig Miles van der Rohe becomes the third director of the Bauhaus

~ John Heartfield creates photomontages for the Arbeiter‐Illustrierte Zeitung (AIZ)

1931

~ Unemployment reaches five million and a state of emergency is declared in Germany

1932

~ Nazis increase their representation in the Reichstag to 230 seats but are unable to form a majority coalition

~ Miles van der Rohe moves the Bauhaus to Berlin

~ Grosz relocates to New York as an exile

1933

~ Hindenberg names Hitler as Chancellor

~ Hitler creates a dictatorship under the Nazi regime

~ The first Degenerate art exhibition denouncing modern art is held in Dresden

~ Miles van der Rohe announces the closure of the Bauhaus

~ Nazis organise book burnings in Berlin

~ Many artists including Gropius, Kandinski and Klee flee Germany

~ Beckmann, Dix and Schlemmer lose their teaching positions

1934

~ Fifteen concentration camps exist in Germany

1935

~ The swastika becomes the flag of the Reich

1936

~ Spanish civil war begins

~ Germany violates the Treaty of Versailles

~ Olympic Games held in Garmisch‐Partenkirchen and Berlin

~ Thomas Mann deprived of his citizenship and emigrates to the United States

1937

~ German bombing raids over Guernica in Spain in support of Franco

~ The Nazi’s Degenerate art exhibition opens in Munich and attracts two million visitors

~ Beckmann, Kirchner and Schwitters leave Germany

~ Purging of ‘degenerate art’ from German museums continues 1

1/ Timeline credit: Chronology compiled by Jacqueline Strecker and Victoria Tokarowski from the following sources:

~ Catherine Heroy ‘Chronology’ in Sabine Rewald, Glitter and Doom: German portraits from the 1920s, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, exh cat, 2006, pp. 39‐46

~ Anton Kaes, Martin Jay and Edward Dimendberg, eds, ‘Political chronology’, The Weimar Republic sourcebook, Berkely 1994, pp. 765‐71

~ Jonathan Petropoulos and Dagmar Lott‐Reschke ‘Chronology’ in Stephanie Barron, ‘Degenerate Art’: the fate of the avant‐garde in Nazi Germany, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, exh cat, 1991, pp. 391‐401

László Moholy-Nagy (American born Hungary, 1895-1946)

Bauhaus Balconies

1926

Silver gelatin photograph

John Heartfield (German, 1891-1968)

Adolf, the superman: swallows gold and spouts rubbish

1932

From the Workers Illustrated Paper, vol 11, no 29, 17 July 1932, p. 675

Photolithograph

38 x 27cm

John Heartfield Archiv, Akademie der Künste zu Berlin

Photo: Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Kunstsammlung, Heartfield 2261/ Roman März

© The Heartfield Community of Heirs /VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

John Heartfield’s photomontages expose hidden agendas in German politics and economics of the 1920s and 30s. This image was published six months before the National Socialist Party came to power, and shows Hitler with a spine made of coins and his stomach filled with gold. The caption says that he ‘swallows gold’, alluding to generous funding by right-wing industrialists, and ‘spouts rubbish’.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (German, 1880-1938)

Woman in hat

1911

Oil on canvas

Art gallery of Western Australia, Perth

George Grosz (German, 1893-1959)

Suicide (Selbstmörder)

1916

Oil on canvas

100 × 77.5cm

Tate Modern

Public domain

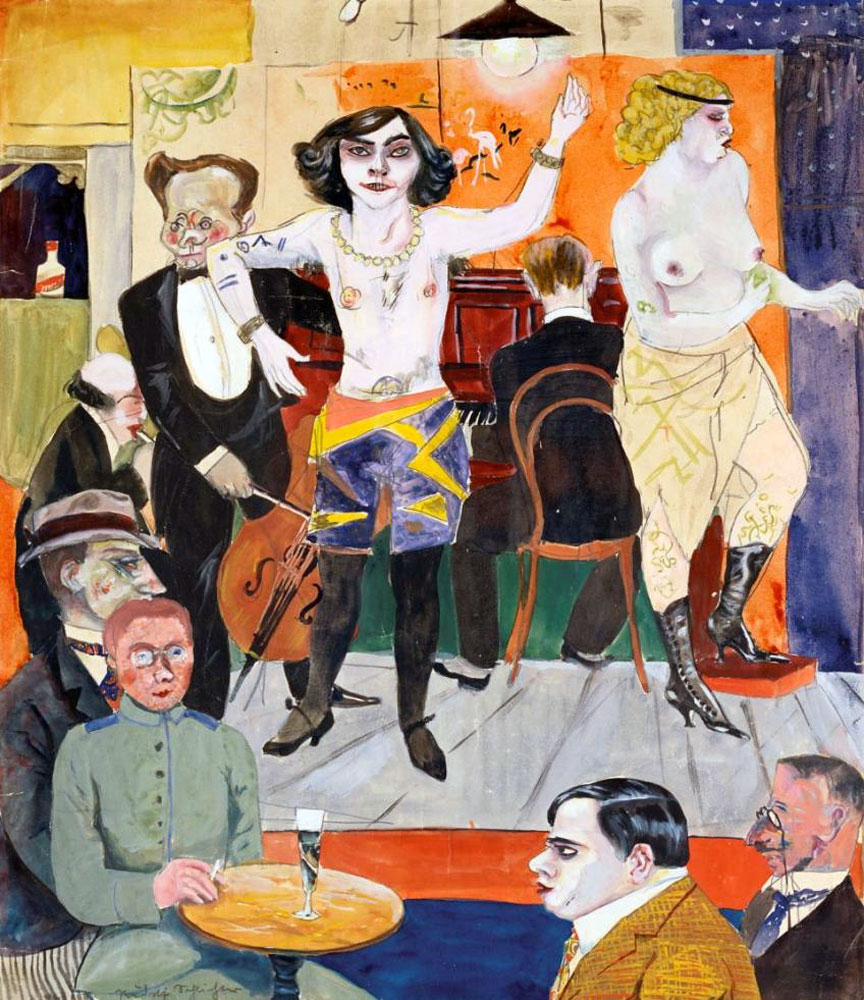

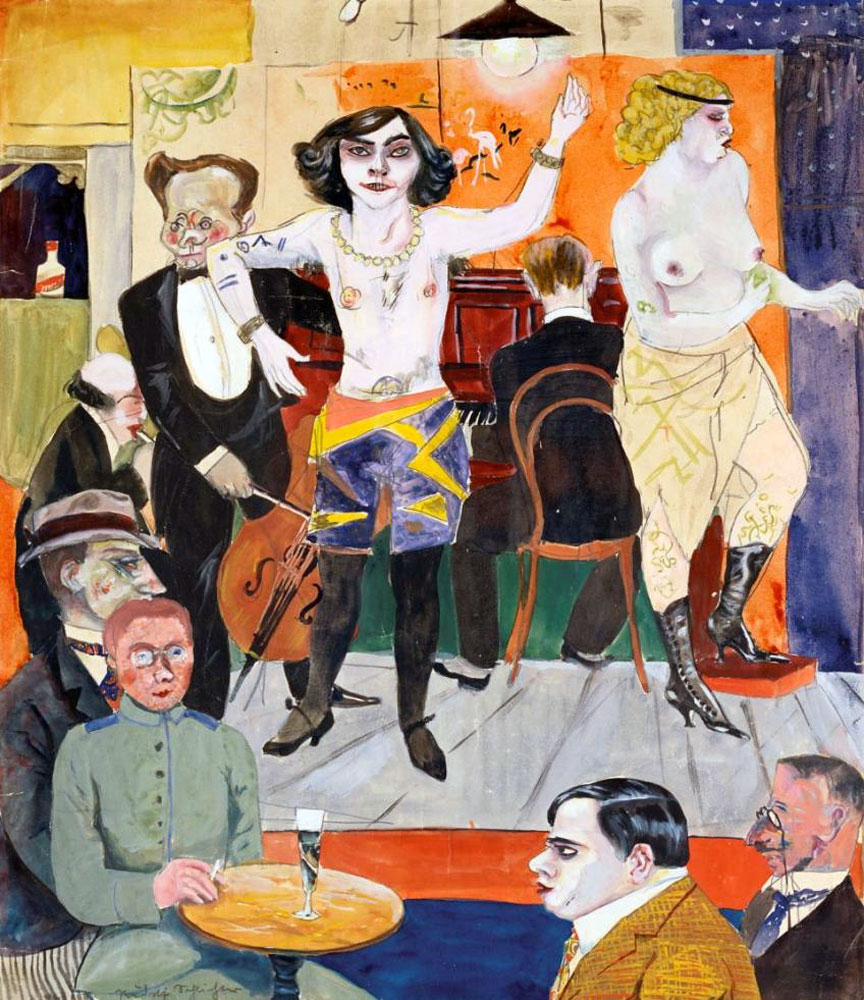

Rudolf Schlichter (German, 1890-1955)

Tingle tangel

1919-1920

Oil on canvas

George Grosz (German, 1890-1945)

Tatlinesque Diagram

1920

Watercolour, collage and ink on paper

41 x 29.2cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Dr Paul Ferdinand Schmidt

1921

Oil on canvas

63 x 82cm

Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart, Germany

El Lissitzky (Russian, 1890-1941)

New Man (Neuer)

1923

Color lithograph on wove paper

12 × 12 1/2 in. (30.5 × 31.8cm)

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

The trapeze

1923

Oil on canvas

196.5 x 84cm

Toledo Museum of Art

Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey

Photo: Photography Incorporated, Toledo

Werner Graul (German, 1905-1984)

UFA (Universum-Film-Aktiengesellschaft) (publisher)

Metropolis

1926

Lithographic poster

Christian Schad (German, 1894-1982)

Self-Portrait with Model (Selbstbildnis mit Modell)

1927

Oil on wood

29 15/16 x 24 3/16 in. (76 x 61.5cm)

Private collection, courtesy of Tate

© 2015 Christian Schad Stiftung Aschaffenburg/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Heinrich Hoerle (German, 1895-1936)

Three invalids

c. 1930

Oil on canvas

NGV International

180 St Kilda Road

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

National Gallery of Victoria website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Invierno en el patio' [Winter in the Courtyard] Paris, 1939 Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Invierno en el patio' [Winter in the Courtyard] Paris, 1939](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/invierno-en-el-patio-web.jpg)

![Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Subida a la catedral [Ascending to the Cathedral], Spanish Civil War' Barcelona 1938 Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Subida a la catedral [Ascending to the Cathedral], Spanish Civil War' Barcelona 1938](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/subida-a-la-catedral-web.jpg)

![Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Los Paraguas, mitin de la CNT' [Umbrellas, Meeting of the CNT], Spanish Civil War Barcelona, 1937 Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Los Paraguas, mitin de la CNT' [Umbrellas, Meeting of the CNT], Spanish Civil War Barcelona, 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/los-paraguas-mitin-de-la-cnt-web.jpg)

![Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Untitled, Oda a la necrofília series [Ode to Necrophilia]' Mexico 1962 Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Untitled, Oda a la necrofília series [Ode to Necrophilia]' Mexico 1962](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/necrophilia-web.jpg)

![Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'El botellón' [The Bottle] Mexico, 1962 Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'El botellón' [The Bottle] Mexico, 1962](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/el-botellc3b3n-web.jpg)

![Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Antonio Souza y su esposa Piti Saldivar' [Antonio Souza and his Wife Piti Saldivar] Mexico, 1959 Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Antonio Souza y su esposa Piti Saldivar' [Antonio Souza and his Wife Piti Saldivar] Mexico, 1959](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/souza-web.jpg)

![Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'José Horna elaborando la maqueta de la casa de Edward James' [José Horna Working on the Maquette for Edward James's House] Mexico, 1960 Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'José Horna elaborando la maqueta de la casa de Edward James' [José Horna Working on the Maquette for Edward James's House] Mexico, 1960](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/josc3a9-horna-elaborando-web.jpg)

![Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Mujer y máscara' [Woman with Mask] Mexico, 1963 Kati Horna (Mexican born Hungary, 1912-2000) 'Mujer y máscara' [Woman with Mask] Mexico, 1963](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/woman-with-mask-web.jpg)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled Untitled [boy with a violoncello, Balaton, Hungary]' 1931 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled Untitled [boy with a violoncello, Balaton, Hungary]' 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eva_besnyo_gypsy_boy-web.jpg)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Shadow play]' Hungary 1931 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Shadow play]' Hungary 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eva_besnyo_shadow_play-web.jpg?w=650)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [dockers on the Spree]' Berlin, 1931 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [dockers on the Spree]' Berlin, 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eva_besnyo_docks-web.jpg?w=650)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Vertigo #3]' Nd Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Vertigo #3]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/photo_by_eva_besnyo_vertigo3-web.jpg?w=650)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Summer house in Groet, North Holland. Architects Merkelbach & Karsten]' 1934 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Summer house in Groet, North Holland. Architects Merkelbach & Karsten]' 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb18-web.jpg)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Lieshout, The Netherlands]' 1954 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Lieshout, The Netherlands]' 1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb15-web.jpg?w=650)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [John Fernout with Rolleiflex at the Baltic seaside]' 1932 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [John Fernout with Rolleiflex at the Baltic seaside]' 1932](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb02-web.jpg?w=650)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Magda, Balaton, Hungary]' 1932 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [Magda, Balaton, Hungary]' 1932](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb04-web.jpg?w=650)

![Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [The shadow of John Fernhout, Westkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands]' 1933 Eva Besnyö (Dutch-Hungarian, 1910-2003) 'Untitled [The shadow of John Fernhout, Westkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands]' 1933](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/eb13-web.jpg?w=650)

![Karl Grill (German active Donaueschingen, Germany 1920s) 'Untitled [Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet]' c. 1926-1927 Karl Grill (German active Donaueschingen, Germany 1920s) 'Untitled [Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet]' c. 1926-1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/grill-spiral-costume-from-the-triadic-ballet.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.