Exhibition dates: 21st March – 16th June 2024

Curator: Magdalene Keaney

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

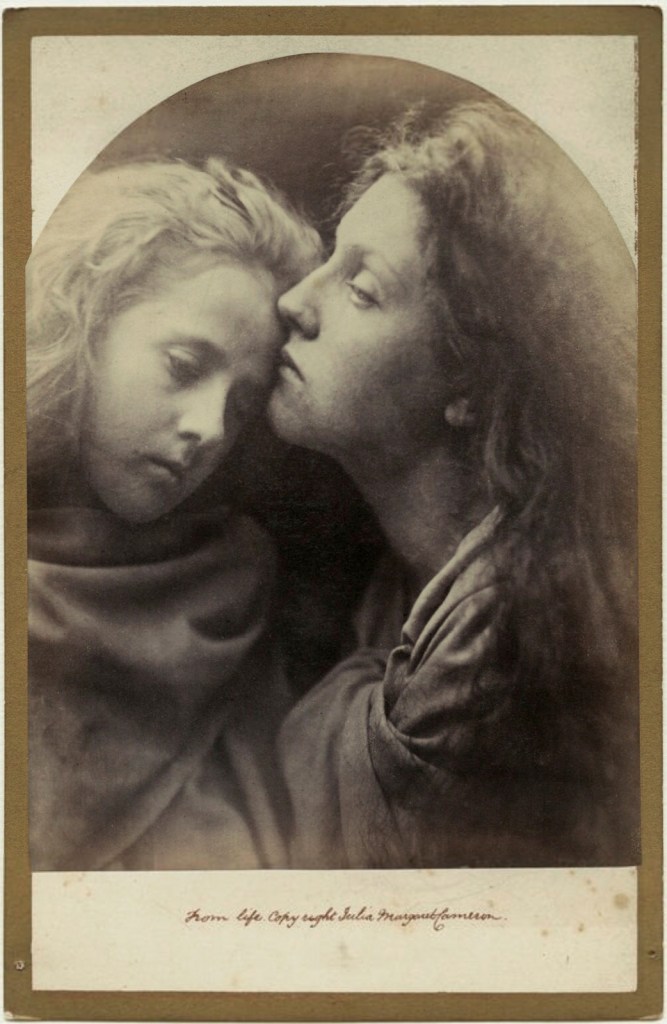

The Dream (Mary Hillier)

1869

Albumen silver print

Wilson Centre for Photography

Mary Ann Hilliar was born on the Isle of Wight, and as well as being Julia Margaret Cameron’s favourite model was employed by her as a house maid. She often poised in religious themed photos looking noble and melancholy. As well as modelling for Mrs Cameron she was painted by G F Watts.

She married Thomas Gilbert and had 8 children, descendants of whom still live on the Isle of Wight. Mary Ann lived to the age of 88, although in her later years she suffered badly from rheumatism and was almost blind due to cataracts. She is buried just a few feet away from the Tennyson grave.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

Otherworldy beings: the materialisations and transformations of Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron

To pair these two artists together is curatorial inspiration from the gods!

In both artist’s work the notion of materialisation (the process of coming into being) and transformation is a powerful creative tool.

Cameron‘s photographs are exterior to the artist, outward facing creations which capture in the sitter an emanation of spirit. These ethereal creatures mainly based on biblical, mythological, or literary figures … these beautiful apparitions who seem to hover before us were, at the time, seen as radical photographs. Their striking presences and emotive sensibility create a psychological connection with the viewer, photographs imaged / imagined as if they were seen in a dream.

“Cameron’s portraits are famously a pictorialist stagecraft: a pantomime of Christian archetypes, Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics, and the influence of contemporary poets such as Shelley, Keats and Tennyson. What would be considered as potential subject matter for this nascent thirty-year-old medium was formative and cautious, and the conventions of beauty and gender, static” opines Stephen Frailey in an article commenting on the exhibition on the Aperture website (see below). Nothing could be further from the truth.

The artist envisions CHIMERICAL CREATURES. At the time of their production, Cameron’s shimmering portraits were seen as anything but cautious, they were seen as radical and ephemeral: a unique vision, different from everyone else: “directed light, soft focus, and long exposures that allowed the sitters’ slight movement to register in her pictures, instilling them with a sense of breath and life.”1 And, despite their soft focus, I believe that they are never “Pictorialist” photographs – they are “modern” photographs of a radical nature which may have later influenced the Pictorialist aesthetic. As I have commented before,

“She has, of course, been seen as a precursor to Pictorialism, but personally I do not get that feeling from her photographs, even though the artists are using many of the same techniques. Her work is based on the reality of seeing beauty, whereas the Pictorialists were trying to make photography into art by emulating the techniques of etching and painting. While the form of her images owes a lot to the history of classical sculpture and painting, to Romanticism and the Pre-Raphaelites, she thought her’s was already art of the highest order. She did not have to mask its content in order to imitate another medium. Others, such as the curator of the exhibition Marta Weiss, see her as a proto-modernist, precursor to the photographs of Stieglitz and Sander and I would agree. There is certainly a fundamental presence to JMC’s photographs, so that when you are looking at them, they tend to touch your soul, the eyes of some of the portraits burning right through you; while others, others have this ambiguity of meaning, of feeling, as if removed from the everyday life.”2

Contemporary commentators condemned Cameron’s photographs for sloppy craftsmanship (they were out of focus, the plates contained fingerprints, dust, debris, streak marks and swirls of collodion on her negatives). Others mocked her for claiming to have photographed a historical figure ‘from the life’. The kinds of images being made at the time did not interest Cameron. The artist would focus her lens until she thought the subject was beautiful “instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon.” (JMC) “Her photographic vision was a rejection of ‘mere conventional topographic photography – map-making and skeleton rendering of feature and form’ in favour of a less precise but more emotionally penetrating form of portraiture.”3

Woodman‘s photographs are interior to the artist, inward facing creations which capture her/self and the female form in space as a flux or metamorphosis of spirit.

“Francesca Woodman’s photographs explore issues of gender and self, looking at the representation of the body in relation to its surroundings. She puts herself in the frame most often, although these are not conventional self-portraits as she is either partially hidden, or concealed by slow exposures that blur her moving figure into a ghostly presence.”4

They promote in the attentive viewer a ghostly insistence that you could be her – in vulnerability, in presence, in fear of suffering, for our death. Who are we that is represented, what is our place in this lonely world, how do we interact with our shadow? They offer glimpses of another, dream-like world, the microcosm of a life focusing a lens on (her) infinite spirit.

“The artist is a CHIMERICAL CREATURE. Imaginary, visionary. Woodman’s transformations, her interior elements, become part of the wall or the house. She vanishes “from the room, out of the picture, at any given second.”5 A preoccupation with the body / her own body, and the dichotomy of subject-object, also adds multiple meanings and complexity to Woodman’s work. Her many angel images (and also images of umbrellas – Mary Poppins was released in 1964 when Woodman was growing up) suggest movement and the ability to fly, a fascination that found its ultimate expression when she jumped off a building in lower Manhattan at the age of 22.”6

Both Cameron, a woman taking photographs for just fifteen years within the first twenty five years of the birth of commercial photography, using rudimentary technology and chemicals – and Woodman, a woman taking photographs for just eight years, whose practice of staging her body and her face in interior spaces so influenced a later generation of female artists – have left an indelible mark on the history of photography and identity formation.

Working “at times when women were marginal in the history of art and photography” both women are now regarded as important artists, in the upper echelons of photographers who have ever lived. The unique quality of their work shines through, each materialising a distinctive handwriting which could only ever be a Cameron or a Woodman (the atmospheric radiance of the one and a sense of vulnerability in the other). In their photographs I feel the transformative potential of that vision (it rumbles through my body, it impinges on my consciousness). Their ability to see things not as others see them, away from the too-rough fingers of the world.

Oh how I would like to see this exhibition in the flesh, to observe the synergies and differences between both artist’s works, to listen to the conversations across time and space through centuries of art practice. I will just have to buy the catalogue instead, but that is no substitute for physically standing in front of their “beautiful, subtle, intricate, and beguiling” prints.

To feel the vibrations of energy from these otherworldy beings…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Press release from the exhibition Julia Margaret Cameron at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, August 2013 – January 2014

2/ Marcus Bunyan. “The road less travelled,” on the exhibition ‘Julia Margaret Cameron: from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London’ at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Sydney on the Art Blart website 24th October 2015 [Online] Cited 11/06/2024

3/ Anonymous. “A Study of the Cenci,” on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 11/06/2024

4/ Text from the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art website [Online] Cited 25/06/2009. No longer available online

5/ Anna Tellgren. Francesca Woodman: On Being an Angel (50kb pdf). 2015, p. 11

6/ Marcus Bunyan. “The artist as chimerical creature,” on the exhibition ‘Francesca Woodman. On Being an Angel’ at Moderna Museet, Stockholm on the Art Blart website 4th December 2015 [Online] Cited 11/06/2024

Other exhibitions on Julia Margaret Cameron and Francesca Woodman on Art Blart

- Exhibition: ‘Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography’ at the National Portrait Gallery, London Part 1, March – May 2018

- Exhibition: ‘Julia Margaret Cameron’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, November 2015 – February 2016

- Exhibition: ‘Julia Margaret Cameron: from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London’ at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Sydney Part 2, August – October 2015

- Exhibition: ‘Julia Margaret Cameron: from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London’ at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Sydney Part 1, August – October 2015

- Exhibition: ‘Julia Margaret Cameron’ at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, August 2013 – January 2014

- Exhibition: ‘Francesca Woodman. On Being an Angel’ at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, September – December 2015

- Exhibition: ‘Francesca Woodman’ at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, March – June 2012

- Exhibition: ‘ARTIST ROOMS: Celmins, Gallagher, Hirst, Katz, Warhol, Woodman’ at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, March – November 2009

Many thankx to the National Portrait Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

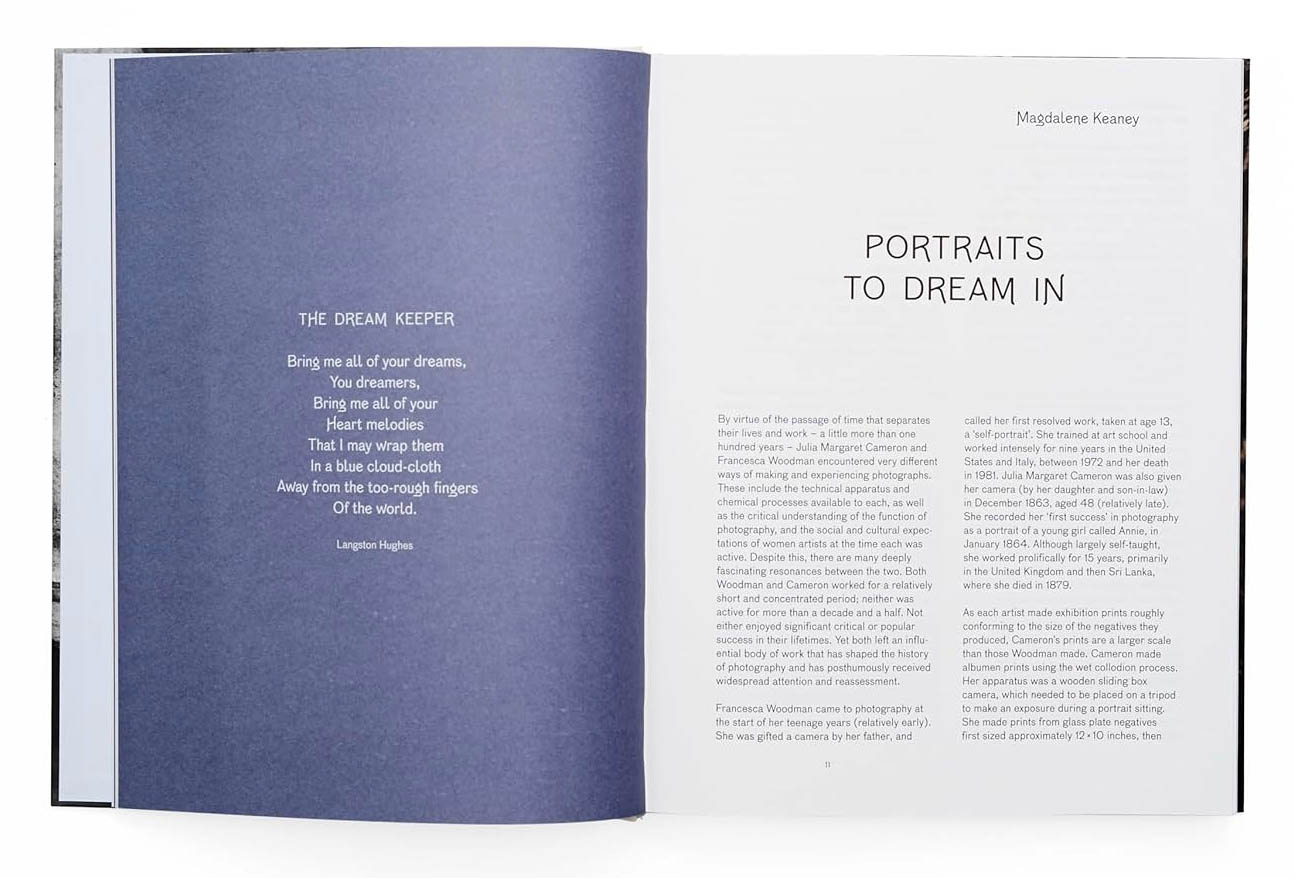

The Dream Keeper

Bring me all of your dreams,

You dreamers,

Bring me all of your

Heart melodies

That I may wrap them

In a blue cloud-cloth

Away from the too-rough fingers

Of the world

Langston Hughes

Major exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery to showcase rare vintage prints by two of art history’s most influential photographers – Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron

More than 160 rare vintage prints will be exhibited as part of Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, as the two photographers – who worked 100 years apart – are presented in parallel for the first time.

The exhibition will present a thematic exploration of the photographic work produced throughout both artists’ entire careers, including their best known and less familiar work. Artist’s books by Francesca Woodman, which have never been exhibited in the UK, will be on display.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

The Dream

1869

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Alan S. Cole, 19 April 1913

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

John Milton’s poem On his deceased Wife (about 1658) tells of a fleeting vision of his beloved returning to life in a dream.

L-R: The Dream (Mary Hillier) by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1869. Wilson Centre for Photography; Untitled, 1979 by Francesca Woodman. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London; Annie (My very first success in Photography), by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1864. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Self Portrait at Thirteen by Francesca Woodman, 1972. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

This spring, the National Portrait Gallery in London has staged an unexpected pairing of Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron, whose bodies of photographic work were made a hundred years apart. The lushly titled Portraits to Dream In, the result of a thoughtful and imaginative curatorial inquiry, provides a compelling guide to their posthumous resemblances and describes a cultural arc of Romanticism from the mid-nineteenth-century to the turn of the twentieth, from luminous and pastoral to haunted and opaque. Both artists were engaged with the past, and the exhibition places them in a shared classicism of figuration and myth – a revelatory insight for Woodman. Both practiced photography for less than fifteen years. Both of their biographies often eclipse their critical reception. At times their congruence feels magnetic; at times their differences are as illuminating as their similarities.

The exhibition is organised by curator Magda Keaney in tidy themes that support affinities between the two women, among them “Angels and Otherworldly Beings,” “Mythology,” “Doubling,” and “Nature and Femininity.” Much of this is informative and, indeed, suggests a universal lexicon beyond this survey of dual sensibilities. Some of the rhymes are less plausible: a section entitled “Men” fails to persuade that Cameron’s depictions of eminent male political and cultural figures mirror Woodman’s male portraits. Unclothed men make rare appearances in Woodman’s photographs, where they do little to diminish the images as self-portraits. Festooned with a seashell, egg, pomegranate, or dead bird, the men serve as playful surrogates for the photographer herself.

Portraits to Dream In is an occasion to revel in the sumptuous texture of the photographic print, born from technologies decades apart. For both photographers, darkroom manipulation and tactility contribute to the pictures’ emotional mood, however diametric. For Cameron, the shallow depth of field and long shutter speed of the glass plate negative and wet collodion process renders a picture that flutters as if provisional, a vision subject to light glinting off an immaterial surface. They are as ethereal and transparent as Woodman’s are submersed in shadow; a moth bounding away from flame. One body of work, despite its soft patina, feels rooted in a sense of presence, the other by absence: fraught and confessional without evident disclosure.

Extract from Stephen Frailey. “An Unexpected Pairing of Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron,” on the Aperture website May 16, 2024 [Online] Cited 03/06/2024

L-R: The Dream (Mary Hillier) by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1869. Wilson Centre for Photography; Untitled, 1979 by Francesca Woodman. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

L-R: Annie (My very first success in Photography), by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1864. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Self Portrait at Thirteen by Francesca Woodman, 1972. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

Untitled

1979

Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation

© Woodman Family Foundation/DACS London

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Annie (My very first success in Photography)

1864

Albumen silver print

A photographic portrait of Annie Wilhemina Philpot (1857-1936)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

A photographic portrait of Annie Wilhemina Philpot (1857-1936), taken by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) in 1864. This albumen print forms part of the Herschel Album, created by Cameron for her friend Sir John Herschel (1792-1871). Annie was the daughter of Rev. William Benamin Philpot, a poet and friend of Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892).

Julia Margaret Cameron is one of the most significant figures in nineteenth century photography. Born in Calcutta, she moved to Britain where she lived at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight. In 1863, aged forty-eight, she was given a camera by her daughter as a gift. From then on she took portraits of her family, friends and servants, as well as many eminent Victorians. Cameron was strongly influenced by classical art and many of her portraits are pictorial allegories based on religious or literary themes. In 1875 Cameron moved to Sri Lanka (Ceylon), where she died.

Text from the V&A website

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

Self Portrait at Thirteen

1972

Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation

© Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

L-R: Untitled, from the Caryatid series by Francesca Woodman, 1980. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London; House #3 by Francesca Woodman, 1976. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London; Untitled by Francesca Woodman, 1977-1978 Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

Untitled

1980

From the Caryatid series

Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation

© Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

House #3

1976

Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation

© Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

Untitled

1977-1978

Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation

© Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

From 21 March to 16 June 2024, the National Portrait Gallery will display a major retrospective exhibition of work by two of the most significant photographers in the history of the medium – Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) and Francesca Woodman (1958-1981). Bringing their work together for the first time in an exhibition of this scale, it will showcase more than 160 rare vintage prints from galleries, museums and private collections, including 96 works by Woodman and 71 by Cameron, spanning the entire careers of both photographers – who worked 100 years apart.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In will offer a new way to consider these two artists, by moving away from the biographical emphasis that has often been the focus of how their work is understood. The exhibition challenges this approach in its insistence on experiencing the physical print, taking the picture making of Woodman and Cameron as a starting point for consideration of their work. While neither artist aimed for technical perfection in their printing, for each it was a dynamic and essential aspect of their creative process used to explore and extend the possibilities of photographic image making.

After an extensive curatorial research period, works by Julia Margaret Cameron have been selected for loan from major museums internationally including the Getty, Los Angeles; the Metropolitan Museum, New York City; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford; the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; and the National Portrait Gallery’s own Collection. Prints made by Francesca Woodman in her lifetime, nearly 20 of which have not been previously published or exhibited, have been loaned primarily from the Woodman Family Foundation in New York, who have collaborated closely on the making of the exhibition and accompanying publication, with further loans from Tate and the Rhode Island School of Design

The exhibition’s title, Portraits to Dream In, suggests that when seen side by side, both artists conjure a dream state within their work as part of their shared exploration of appearance, identity, the muse, gender and archetypes. The title of the exhibition comes from an observation made by Woodman that photographs could be ‘places for the viewer to dream in’. Both Woodman and Cameron produced work that was deeply rooted in mythology and storytelling and each made portraits of those close to them to represent these narratives. Further, both women explored portraiture beyond its ability to record appearance.

Following a thematic approach, visitors will experience the work of Woodman and Cameron moving forward and back in time between the nineteenth and twentieth century; and also within the relatively short span of years that each artist was active – neither worked for more than fifteen years. Themes on display will comprise: Declaring intentions & claiming space; Angels & Otherworldly Beings; Mythology; Doubling; Nature & femininity; Caryatids & the classical form; Men and Models & Muses.

Key works on display will include the first forays both artists made into the medium of photography, as they began to portray their unique perspectives and carve out distinctive styles. These include Cameron’s self-declared ‘first success’, a portrait of Annie Wilhemina Philpot in 1864, accompanied by Woodman’s ‘Self-portrait at thirteen’, taken during a summer holiday in Antella, Italy in 1972. Photographs depicting angelic and otherworldly figures will be presented in a dense constellation with pieces from Woodman’s evocative and often abstracted Angels series contrasted against Cameron’s more direct representations of cherubic beings and winged cupids. Not to be missed images by Francesca Woodman will include Polka Dots #5 and House #3 both made in 1976, seen alongside ethereal portraits of the British actress Ellen Terry made by Julia Margaret Cameron in 1864.

Other defining works by Woodman include Caryatid pieces from a major photographic project developed in the last year of her life in which she experimented with large scale diazotype prints, including depictions of herself and other models as caryatids – carved female figures which take the place of columns in ancient Greek temples. The exhibition will be the first to draw significant attention to Woodman’s portraits of men as well as exploring the importance of her ongoing photographs of friends. Providing additional insight into her practice, contact sheets and examples of Woodman’s artist’s books will be on display, exhibited in the UK for the first time.

The exhibition will include many of Julia Margaret Cameron’s most famous and much loved portraits, including those of her niece and favourite model, Julia Jackson, who would later be the mother to Bloomsbury artists Virginia Wolf and Vanessa Bell; her striking depiction of Alice Liddell as the goddess Pomona; her portraits of prominent Victorian men including John Frederick William Herschel who she captured as he posed dramatically in The Astronomer (1867); and her frequent muses, May Prinsep and Mary Ann Hillier.

“It is a great pleasure to bring together the work of Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron for the first time in this innovative and imaginative exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. Though, of course, Cameron could not have known Woodman, and Woodman did not explicitly reference Cameron, they shared thematic and formal interests uncovered through the exhibition. Paired in this way, we see their work – individually and together – in a new light; one that feels contemporary and timeless. We are immensely grateful to our lead curator Magdalene Keaney for conceptualising this exhibition with great expertise and for the team at the Woodman Family Foundation in New York who have been wonderfully collaborative partners.”

Dr. Nicholas Cullinan OBE

Director, National Portrait Gallery

“Both Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron were utterly committed to the practice of photography and to their practice as artists without reservation. They both worked incredibly hard at times when women were marginal in the history of art and photography. I hope that visitors relish the physical experience of seeing such a large collection of prints that each artist made. They are beautiful, subtle, intricate, and beguiling. Then of course to come away knowing more about these two women artists who have defined the history of photography. I hope it poses questions about how we might think in new ways about relationships between 19th and 20th century photographic practice and what a portrait is and can be.”

Magdalene Keaney

Curator, Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In

The exhibition will be accompanied by the publication, Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In by curator Magdalene Keaney, which will include essays and contributions from the collections curator of the Woodman Family Foundation, Katarina Jerinic, and leading photography historian, Helen Ennis.

Press release from the National Portrait Gallery

All images National Portrait Gallery, London and © National Portrait Gallery, London unless otherwise stated

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

I Wait (Rachel Gurney)

1872

Albumen silver print

32.7 × 25.4cm (12 7/8 × 10 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

Untitled

1977

From the Angels series

Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation

© Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

Throughout her career, the young American photographer Francesca

Woodman revisited the theme of angels. In On Being an Angel (1976), she is

seen bending backward as light falls on her white body. A black umbrella is

in the distance. The following year she made a new version – an image with

a darker mood in which she shows her face. Woodman developed the angel

motif during a visit to Rome, where she photographed herself in a large,

abandoned building. In these images, she is wearing a white petticoat, but

her chest is bare. White pieces of cloth in the background are like wings. She

called these photographs From Angel series (1977) and From a series on

Angels (1977). There are also a number of pictures simply called Angels

(1977-1978), and among them is one where again she is bending backward, but this time in front of a graffitied wall. These angels are but a few examples of Francesca Woodman’s practice of staging her body and her face.

Anna Tellgren. Francesca Woodman: On Being an Angel (50kb pdf). 2015, p. 9

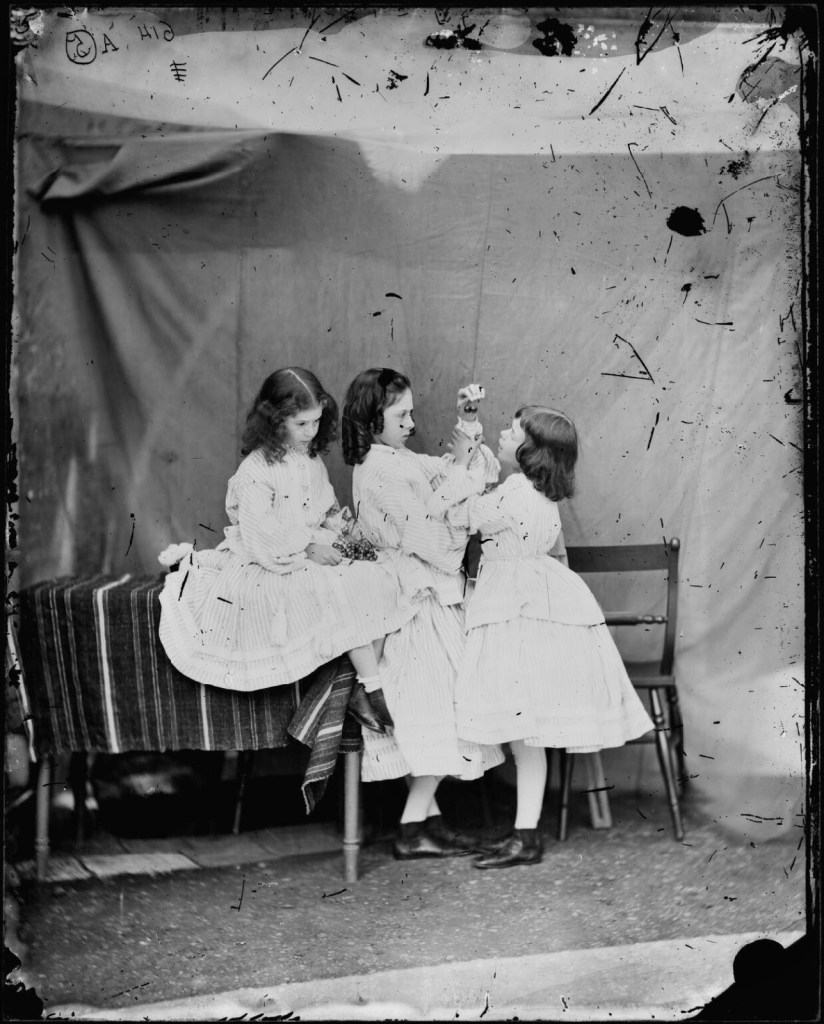

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Cherub and Seraph

1866

Albumen silver print

A photographic study of William Frederick ‘Freddy’ Gould (born 1861) and Elizabeth ‘Topsy’ Keown (born 1859)

National Science and Media Museum

A photographic study of William Frederick ‘Freddy’ Gould (born 1861) and Elizabeth ‘Topsy’ Keown (born 1859), taken by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) in 1866. This albumen print forms part of the Herschel Album, created by Cameron for her friend Sir John Herschel (1792-1871).

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Sadness (Ellen Terry)

1864

Albumen silver print

22.2 x 17.6cm (8 3/4 x 6 15/16 in.)

Albumen silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Dame Alice Ellen Terry GBE (27 February 1847 – 21 July 1928) was a leading English actress of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born into a family of actors, Terry began performing as a child, acting in Shakespeare plays in London, and toured throughout the British provinces in her teens. At 16, she married the 46-year-old artist George Frederic Watts, but they separated within a year. She soon returned to the stage but began a relationship with the architect Edward William Godwin and retired from the stage for six years. She resumed acting in 1874 and was immediately acclaimed for her portrayal of roles in Shakespeare and other classics.

In 1878 she joined Henry Irving’s company as his leading lady, and for more than the next two decades she was considered the leading Shakespearean and comic actress in Britain. Two of her most famous roles were Portia in The Merchant of Venice and Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing. She and Irving also toured with great success in America and Britain.

In 1903 Terry took over management of London’s Imperial Theatre, focusing on the plays of George Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen. The venture was a financial failure, and Terry turned to touring and lecturing. She continued to find success on stage until 1920, while also appearing in films from 1916 to 1922. Her career lasted nearly seven decades.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

Polka Dots #5

1976

Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation

© Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London

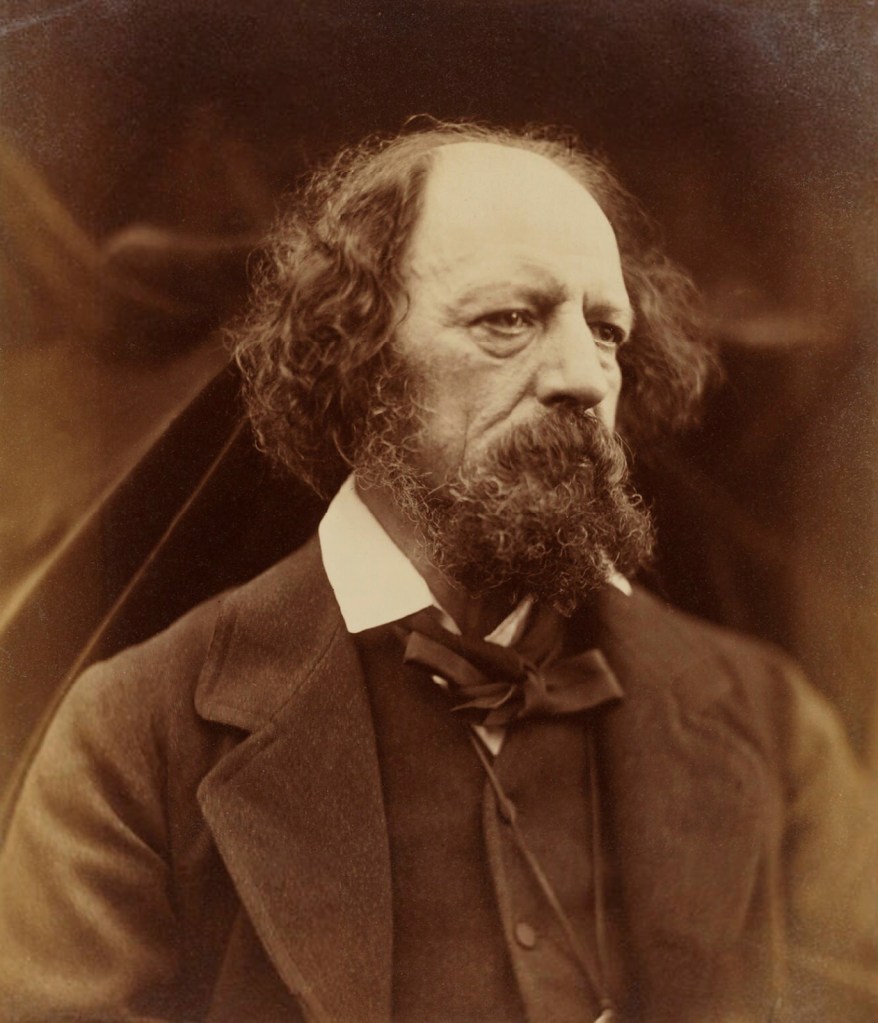

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Julia Prinsep Stephen (née Jackson, formerly Mrs Duckworth)

1867

Albumen silver print

National Portrait Gallery, London

Julia Prinsep Stephen (née Jackson; formerly Duckworth; 7 February 1846 – 5 May 1895) was an English Pre-Raphaelite model and philanthropist. She was the wife of the biographer Leslie Stephen and mother of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, members of the Bloomsbury Group.

Julia Prinsep Jackson was born in Calcutta to an Anglo-Indian family, and when she was two her mother and her two sisters moved back to England. She became the favourite model of her aunt, the celebrated photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, who made more than 50 portraits of her. Through another maternal aunt, she became a frequent visitor at Little Holland House, then home to an important literary and artistic circle, and came to the attention of a number of Pre-Raphaelite painters who portrayed her in their work.

Married to Herbert Duckworth, a barrister, in 1867 she was soon widowed with three infant children. Devastated, she turned to nursing, philanthropy and agnosticism, and found herself attracted to the writing and life of Leslie Stephen, with whom she shared a friend in Anny Thackeray, his sister-in-law.

After Leslie Stephen’s wife died in 1875 he became close friends with Julia and they married in 1878. Julia and Leslie Stephen had four further children, living at 22 Hyde Park Gate, South Kensington, together with his seven-year-old mentally disabled daughter, Laura Makepeace Stephen. Many of her seven children and their descendants became notable. In addition to her family duties and modelling, she wrote a book based on her nursing experiences, Notes from Sick Rooms, in 1883.

She also wrote children’s stories for her family, eventually published posthumously as Stories for Children and became involved in social justice advocacy. Julia Stephen had firm views on the role of women, namely that their work was of equal value to that of men, but in different spheres, and she opposed the suffrage movement for votes for women. The Stephens entertained many visitors at their London home and their summer residence at St Ives, Cornwall. Eventually the demands on her both at home and outside the home started to take their toll. Julia Stephen died at her home following an episode of rheumatic fever in 1895, at the age of 49, when her youngest child was only 11. The writer Virginia Woolf provides a number of insights into the domestic life of the Stephens in both her autobiographical and fictional work.

Text from the Wikipedia website

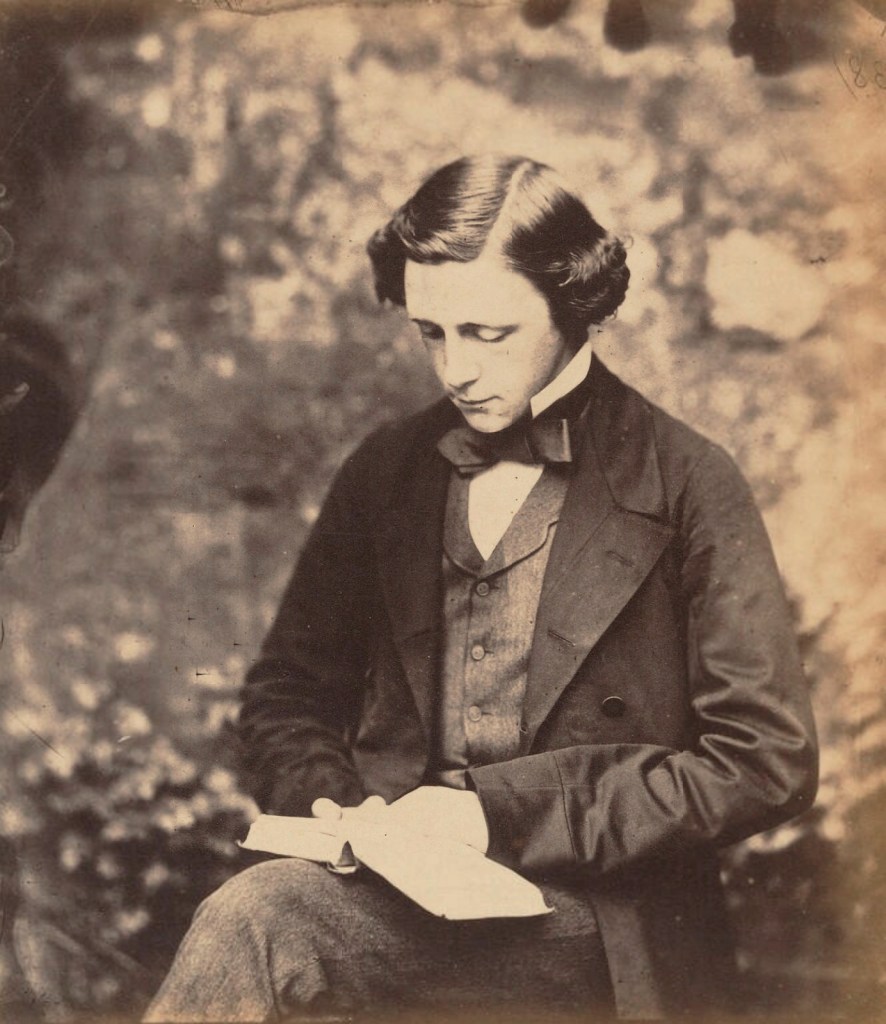

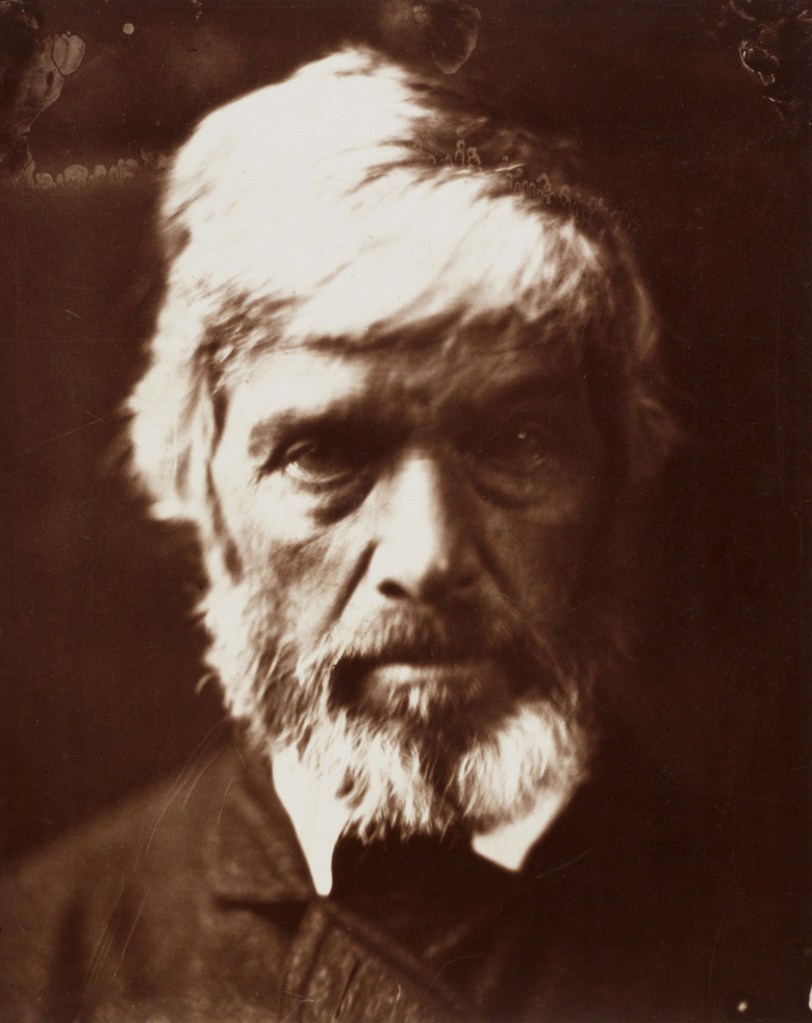

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

The Astronomer (Sir John Frederick William Herschel)

1867

Albumen silver print

Courtesy of the RISD Museum, Providence, RI

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet KH FRS (7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor, and experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical work.

Herschel originated the use of the Julian day system in astronomy. He named seven moons of Saturn and four moons of Uranus – the seventh planet, discovered by his father Sir William Herschel. He made many contributions to the science of photography, and investigated colour blindness and the chemical power of ultraviolet rays. His Preliminary Discourse (1831), which advocated an inductive approach to scientific experiment and theory-building, was an important contribution to the philosophy of science. …

Photography

Herschel made numerous important contributions to photography. He made improvements in photographic processes, particularly in inventing the cyanotype process, which became known as blueprints, and variations, such as the chrysotype. In 1839, he made a photograph on glass, which still exists, and experimented with some colour reproduction, noting that rays of different parts of the spectrum tended to impart their own colour to a photographic paper. Herschel made experiments using photosensitive emulsions of vegetable juices, called phytotypes, also known as anthotypes, and published his discoveries in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1842. He collaborated in the early 1840s with Henry Collen, portrait painter to Queen Victoria. Herschel originally discovered the platinum process on the basis of the light sensitivity of platinum salts, later developed by William Willis.

Herschel coined the term photography in 1839. Herschel was also the first to apply the terms negative and positive to photography.

Herschel discovered sodium thiosulfate to be a solvent of silver halides in 1819, and informed Talbot and Daguerre of his discovery that this “hyposulphite of soda” (“hypo”) could be used as a photographic fixer, to “fix” pictures and make them permanent, after experimentally applying it thus in early 1839.

Herschel’s ground-breaking research on the subject was read at the Royal Society in London in March 1839 and January 1840.

Text from the Wikipedia website

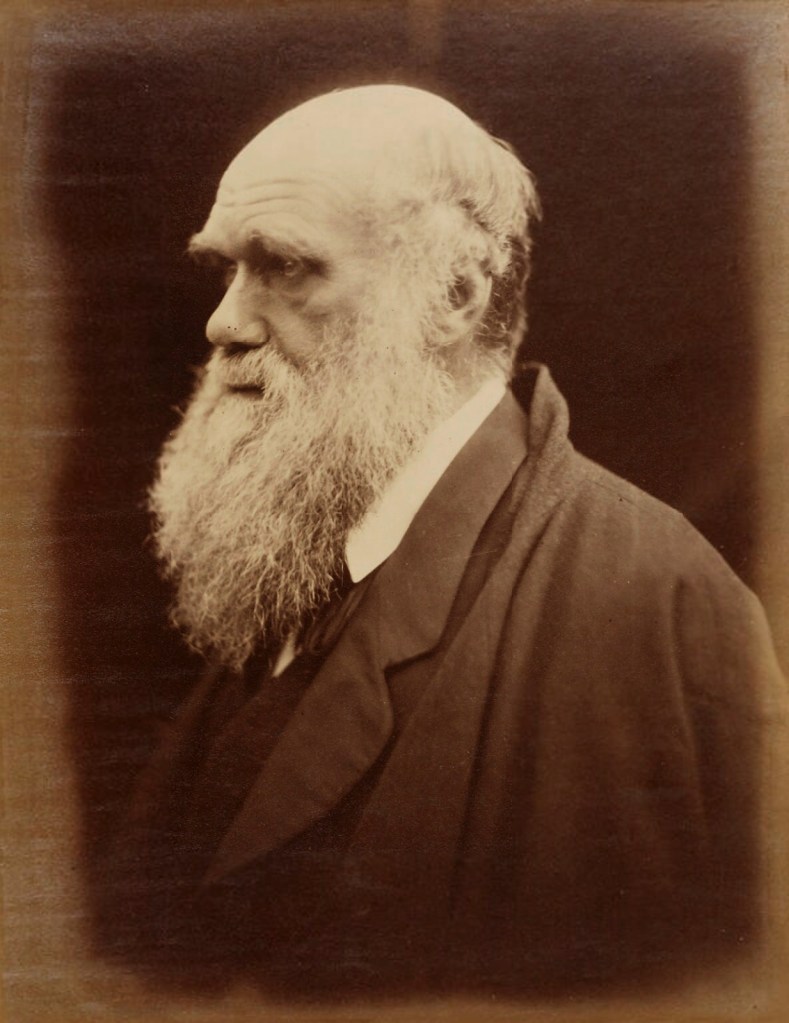

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Pomona (Alice Liddell)

1872

Albumen silver print

The Metropolitan Museum of Art., New York

David Hunter McAlpin Fund, 1963

Pomona was the goddess of fruit trees, gardens, and orchards. Unlike many other Roman goddesses and gods, she does not have a Greek counterpart, though she is commonly associated with Demeter. She watches over and protects fruit trees and cares for their cultivation.

Symbolically, Pomona and her fruit garden represent abundance, nurture and the simple pleasure derived from nature. She is often depicted in a garden full of life, colour and opulence, with her milky soft flesh on display and a cornucopia of fruit and flowers on her lap.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

The Gardener’s Daughter

1867

Albumen silver print

A photographic study of Mary Ryan (1848-1914)

National Science and Media Museum

A photographic study of Mary Ryan (1848-1914), taken by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) in 1867. This albumen print forms part of the Herschel Album, created by Cameron for her friend Sir John Herschel (1792-1871).

‘The Gardener’s Daughter’ was the title of a poem by Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892). Cameron’s photograph was inspired by the lines: ‘Gown’d in pure white, that fitted to the shape, Holding the bush, to fix it back, she stood.’

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Iago – study from an Italian

1867

Albumen silver print

A photographic portrait of the artist’s model, Angelo Colarossi (born about 1839)

National Science and Media Museum

A photographic portrait of the artist’s model, Angelo Colarossi (born about 1839), taken by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) in 1867. The print forms part of the Herschel Album, created by Cameron for her friend Sir John Herschel (1792-1871).

This is the only existing print known of ‘Iago’. The negative may have been destroyed intentionally by Cameron, and it is believed that the print was taken for George Frederic Watts (1817-1904) to work from for a painting.

Iago was the villain of Shakespeare’s play ‘Othello’.

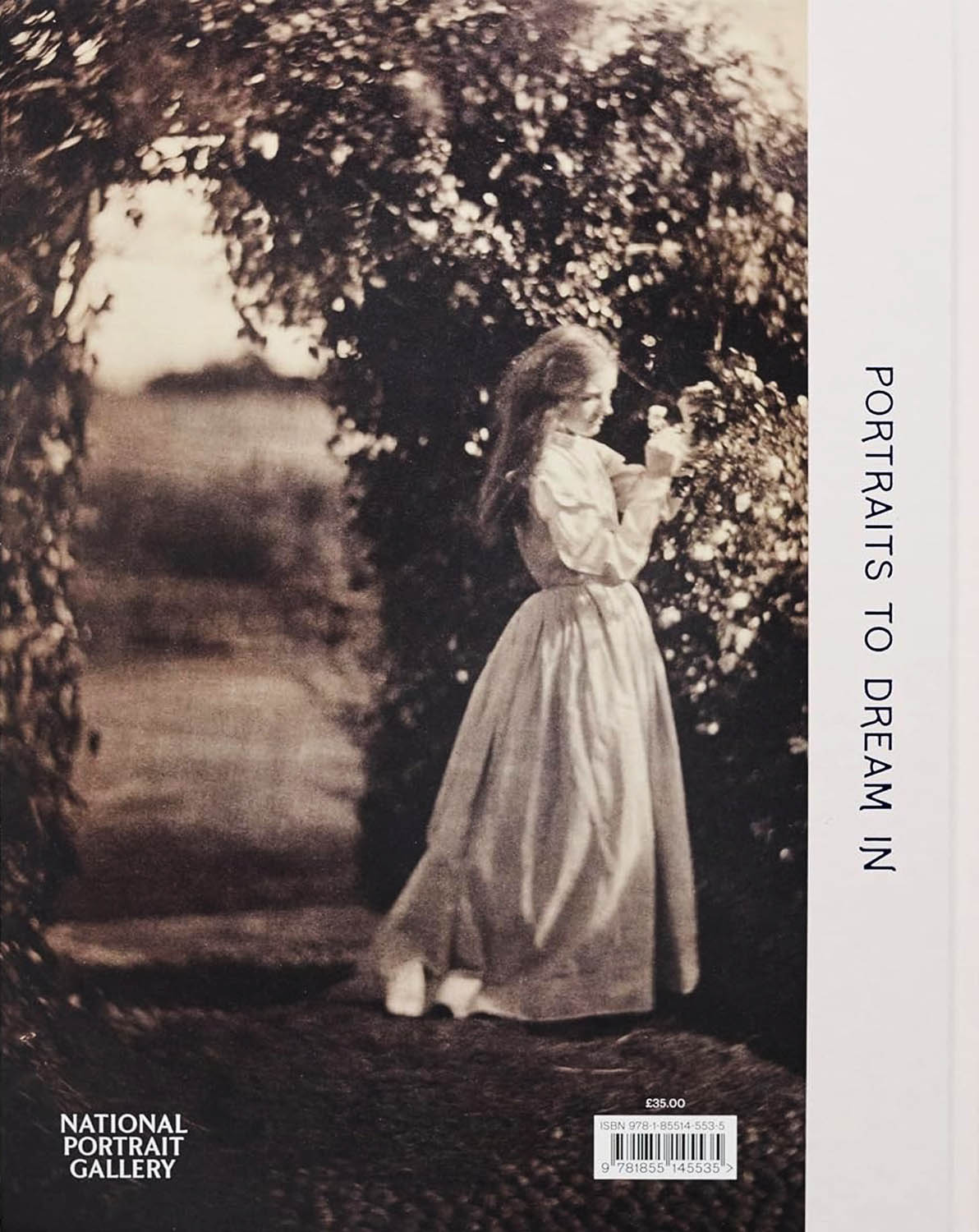

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In book front cover

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In book back cover

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In book p. 11

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In book back cover pp. 70-71

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In

Magdalene Keaney (Editor), Katarina Jerinic (Contributor), Helen Ennis (Contributor)

Hardcover – 26 June 2024

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In draws parallels between two of the most significant practitioners in the history of photography, presenting fresh research, rare vintage prints, and previously unseen archival works.

‘I feel that photographs can either document and record reality or they can offer images as an alternative to everyday life: places for the viewer to dream in.’

~ Francesca Woodman, 1980

Living and working over a century apart, Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) and Francesca Woodman (1958-1981) experienced very different ways of making and understanding photographs. Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In accompanies the exhibition of the same name opening at the National Portrait Gallery, London, in March 2024. Spanning the careers of both artists, the beautifully illustrated catalogue includes their best-known photographs as well as less familiar images. The exhibition works are arranged into eight thematic sections with feature essays, offering an accessible, engaging opportunity to consider both artists in a new light.

This publication presents the artists’ exploration of portraiture as a ‘dream space’. It makes new connections between their work, which pushed the boundaries of the photographic medium and experimented with ideas of beauty, symbolism, transformation and storytelling to produce some of art history’s most compelling and admired photographs.

National Portrait Gallery Publications

208 pages

Text from the Amazon Australia website

National Portrait Gallery

St Martin’s Place

London, WC2H 0HE

Opening hours:

Open daily: 10.30 – 18.00

Friday and Saturday: 10.30 – 21.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.