Exhibition dates: 9th July – 5th October 2014

Curators: Felicity Grobien, curatorial assistant, Modern Art Department, Städel Museum; Dr Felix Krämer, head of the Modern Art Department at the Städel Museum

Roger Fenton (British, 1819-1869)

London: The British Museum

1857

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

32.2 x 43cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

There are some absolutely stunning images in this posting. It has been a great pleasure to put the posting together, allowing me the chance to sequence Roger Fenton’s elegiac London: The British Museum (1857, below) next to Werner Mantz’s minimalist masterpiece Cologne: Bridge (c. 1927, below), followed by Carlo Naya’s serene Venice: View of the Marciana Library (c. 1875, below) and Albert Renger-Patzsch’s sublime but disturbing (because of the association of the place) Buchenwald in November (c. 1954, below). What four images to put together – where else would I get the chance to do that? And then to follow it up with the visual association of the Royal Prussian Institute of Survey Photography’s Cologne: Cathedral (1889, below) with Otto Steinert’s Luminogram (1952, below). This is the stuff that you dream of!

The more I study photography, the more I am impressed by the depth of relatively unknown Eastern European photographers from countries such as Hungary, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Bulgaria and Turkey. In this posting I have included what details I could find on the artists Václav Jíru, Václav Chochola and the well known Czech photographer František Drtikol. The reproduction of his image Crucified (before 1914. below) is the best that you will find of this image on the web.

I would love to do more specific postings on these East European photographers if any museum has collections that they would like to advertise more widely.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. Lichtbilder = light images.

Many thankx to the Städel Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation view of the exhibition Lichtbilder. Photography at the Städel Museum from the Beginnings to 1960 at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt

Installation view of the exhibition Lichtbilder. Photography at the Städel Museum from the Beginnings to 1960 at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing Nadar’s George Sand (1864, below)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin)' c. 1864 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin)' c. 1864](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/nadar-george-sand.jpg)

Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910)

George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin)

c. 1864

Installation view of the exhibition Lichtbilder. Photography at the Städel Museum from the Beginnings to 1960 at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing

(left)

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Country girls

1925

(right)

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Portrait of Anton Räderscheidt

1927

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Country Girls

1925 (print 1980 von by Gunther Sander)

Gelatin silver print

27.4 x 20cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Der Maler Anton Räderscheidt (Painter Anton Räderscheidt)

1926

Gelatin silver print

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Dora Maar (France, 1907-1997)

Mannequin With Perm (installation view)

1935

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Mannequin With Perm

1935

Gelatin silver print on baryta paper mounted on cardboard

23.4 x 17.7cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

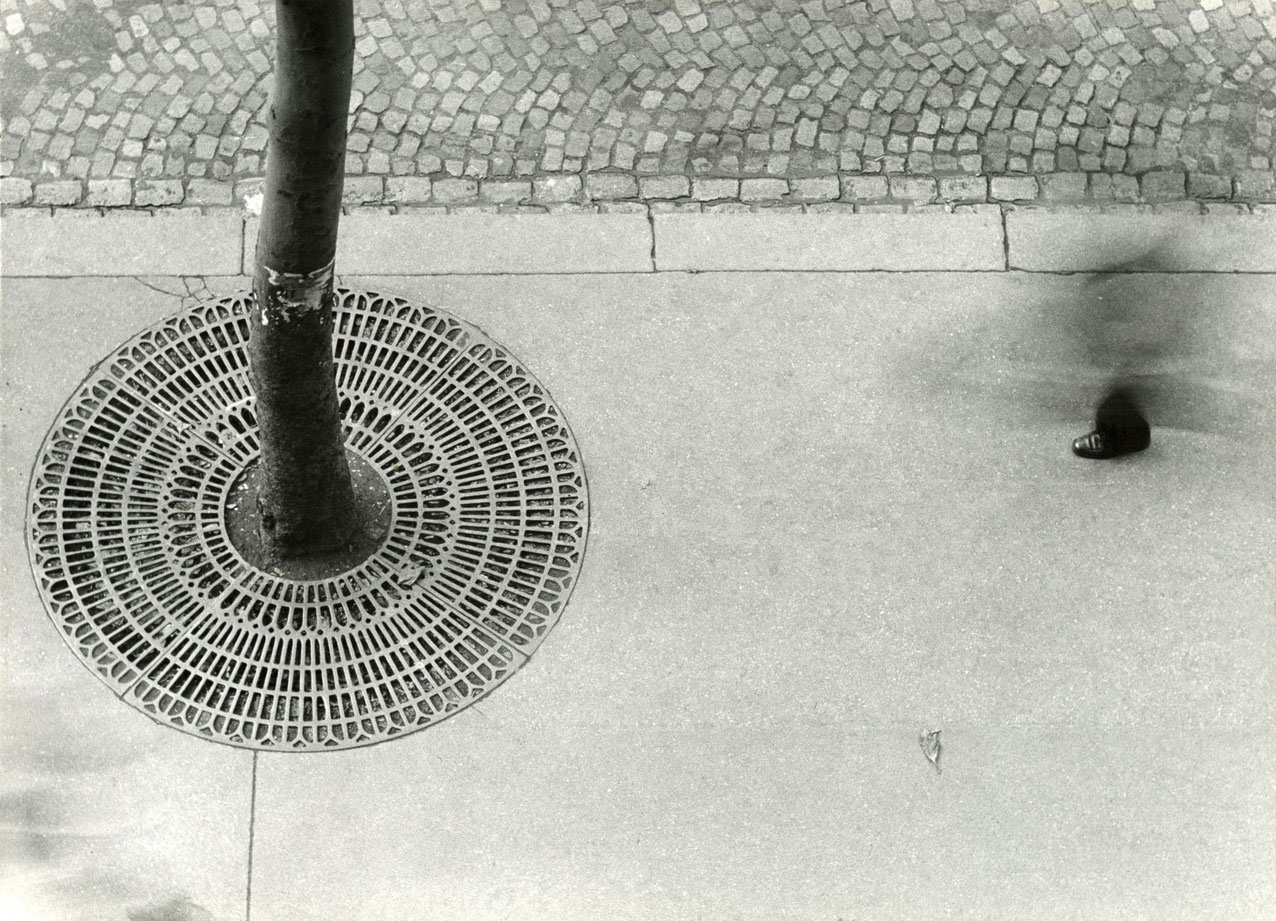

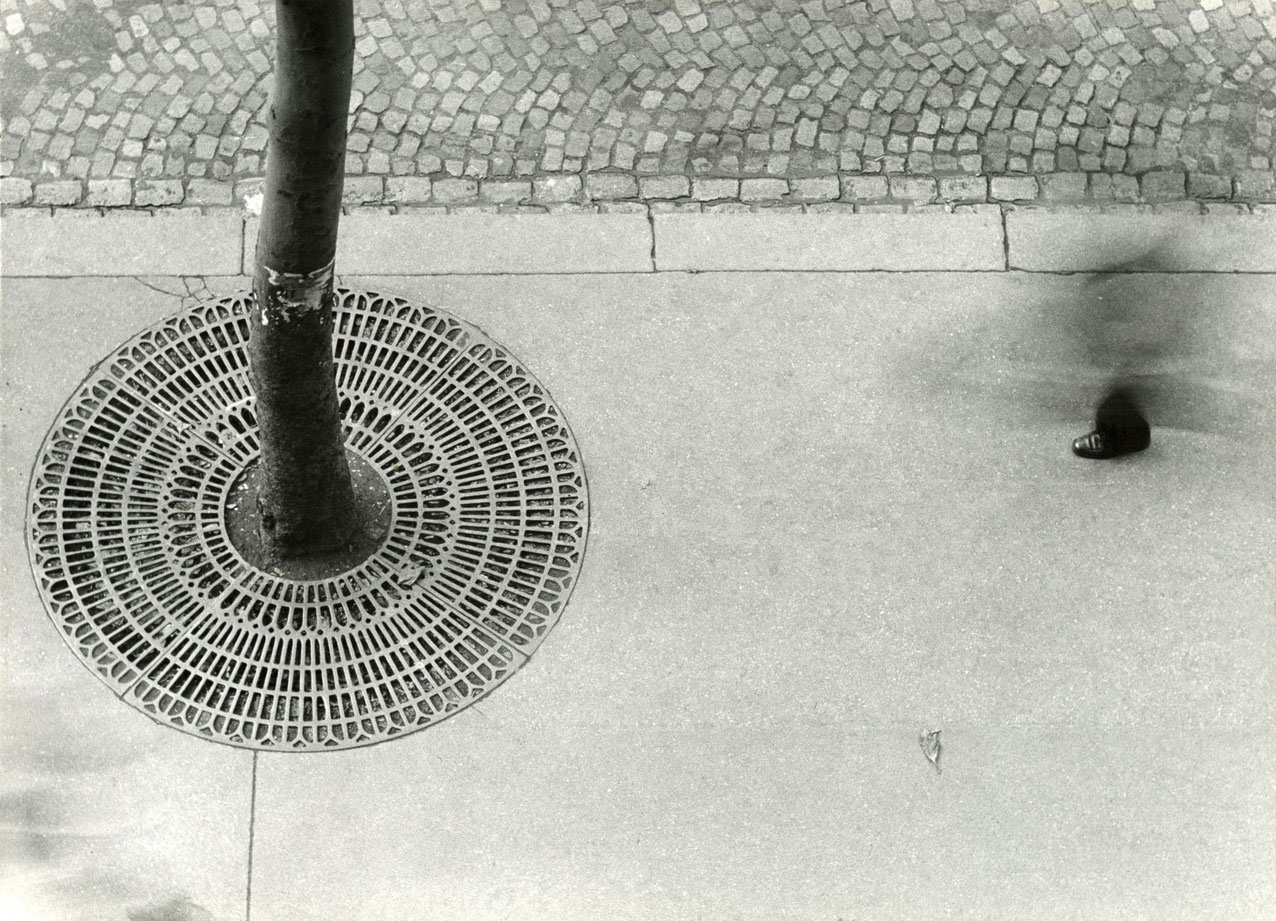

Otto Steinert (1915-1978)

Ein-Fuß-Gänger (installation view)

1950

The Subjective Gaze

After the Second World War a young generation took an innovative approach to the medium of photography. Distancing themselves from the propaganda and heroic photography of the National Socialist era, they looked at the avant grade photography of the 1900s. Among those innovators were the six photographers who founded the fotoform group in 1949: Peter Keetman, Siegfried Lauterwasser, Wolfgang Reisewitz, Toni Schneiders, Otto Steinert and Ludwig Windstosser. Emphasising formal issues they focused on the artist potential of photography and a free and experimental way of working. Abstract and minimal images as well as de-familiarised and dreamlike compositions were the results.

Otto Steinert, who taught art photography initially in Saarbrücken and later in Essen, was soon perceived as the key figure of the movement. In the years to come his exhibitions and publications stood for ‘subjective photography’. He underlined the photographer’s role as artist. By arguing that the camera is inevitably handled by a subjective and calculating author, Steinert weakened the notion of photographic objectivity.

Wall text from the exhibition

Otto Steinert (German, 1915-1978)

Ein-Fuß-Gänger

1950

Gelatin silver print

28.5 × 39cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

Installation view of the exhibition Lichtbilder. Photography at the Städel Museum from the Beginnings to 1960 at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt

Rudolf Koppitz (Austrian, 1884-1936)

Head of a Man with Helmet (installation view)

c. 1929

Carbon print, printed c. 1929

49.8 × 48.4cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt a. M., donated by Annette and Rudolf Kicken 2013

Installation view of the exhibition Lichtbilder. Photography at the Städel Museum from the Beginnings to 1960 at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing at right, Otto Steinert’s La Comtesse de Fleury (1952, below)

Otto Steinert (German, 1915-1978)

La Comtesse de Fleury

1952

Gelatin silver print on baryta paper mounted on hardboard

39.2 x 29.1cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© Nachlass Otto Steinert, Museum Folkwang, Essen

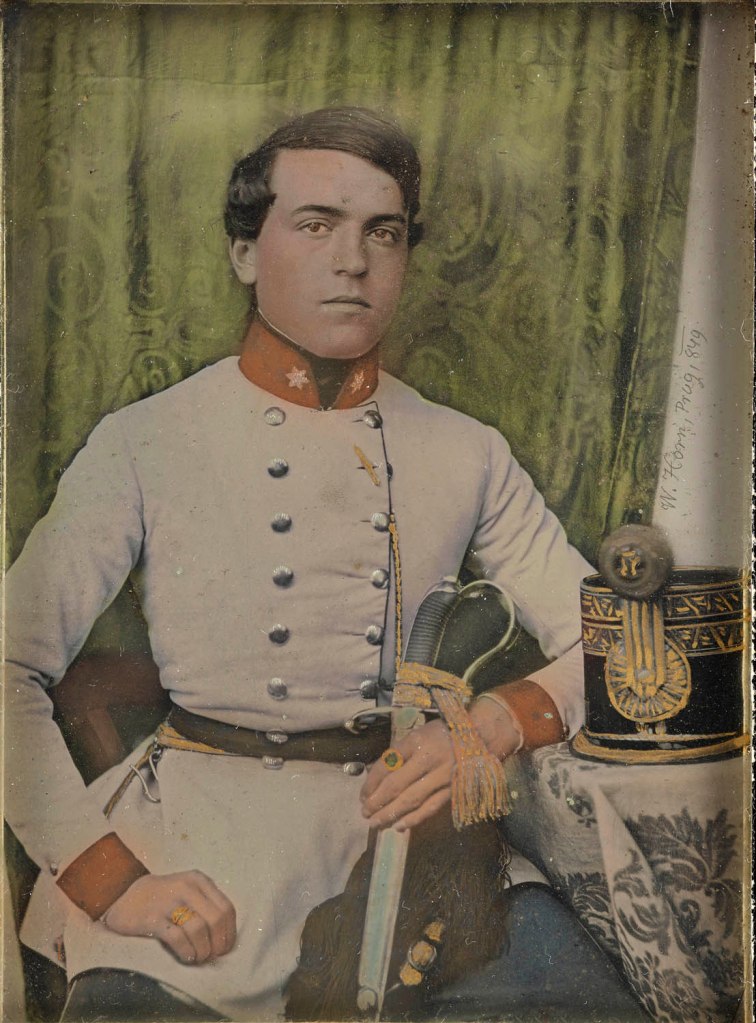

In 1845, the Frankfurt Städel was the first art museum in the world to exhibit photographic works. The invention of the new medium had been announced in Paris just six years earlier, making 2014 the 175th anniversary of that momentous event. In keeping with the tradition it thus established, the Städel is now devoting a comprehensive special exhibition to European photo art – Lichtbilder. Photography at the Städel Museum from the Beginnings to 1960 – presenting the photographic holdings of the museum’s Modern Art Department, which have recently undergone significant expansion. From 9 July to 5 October 2014, in addition to such pioneers as Nadar, Gustave Le Gray, Roger Fenton and Julia Margaret Cameron, the show will feature photography heroes of the twentieth century such as August Sander, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Man Ray, Dora Maar or Otto Steinert, while moreover highlighting virtually forgotten members of the profession. While giving an overview of the Städel’s early photographic holdings and the acquisitions of the past years, the exhibition will also shed light on the history of the medium from its beginnings to 1960.

“Even if we think of the presentation of artistic photography in an art museum as something still relatively new, the Städel already began staging photo exhibitions in the mid 1840s. We take special pleasure in drawing attention to this pioneering feat and – with the Lichtbilder exhibition – now, for the first time, providing insight into our collection of early photography, which has been decisively expanded over the past years through new purchases and generous gifts,” comments Städel director Max Hollein. Felix Krämer, one of the show’s curators, explains: “With Lichtbilder we would like to stimulate a more intensive exploration of the multifaceted history of a medium which, even today, is often still underestimated.”

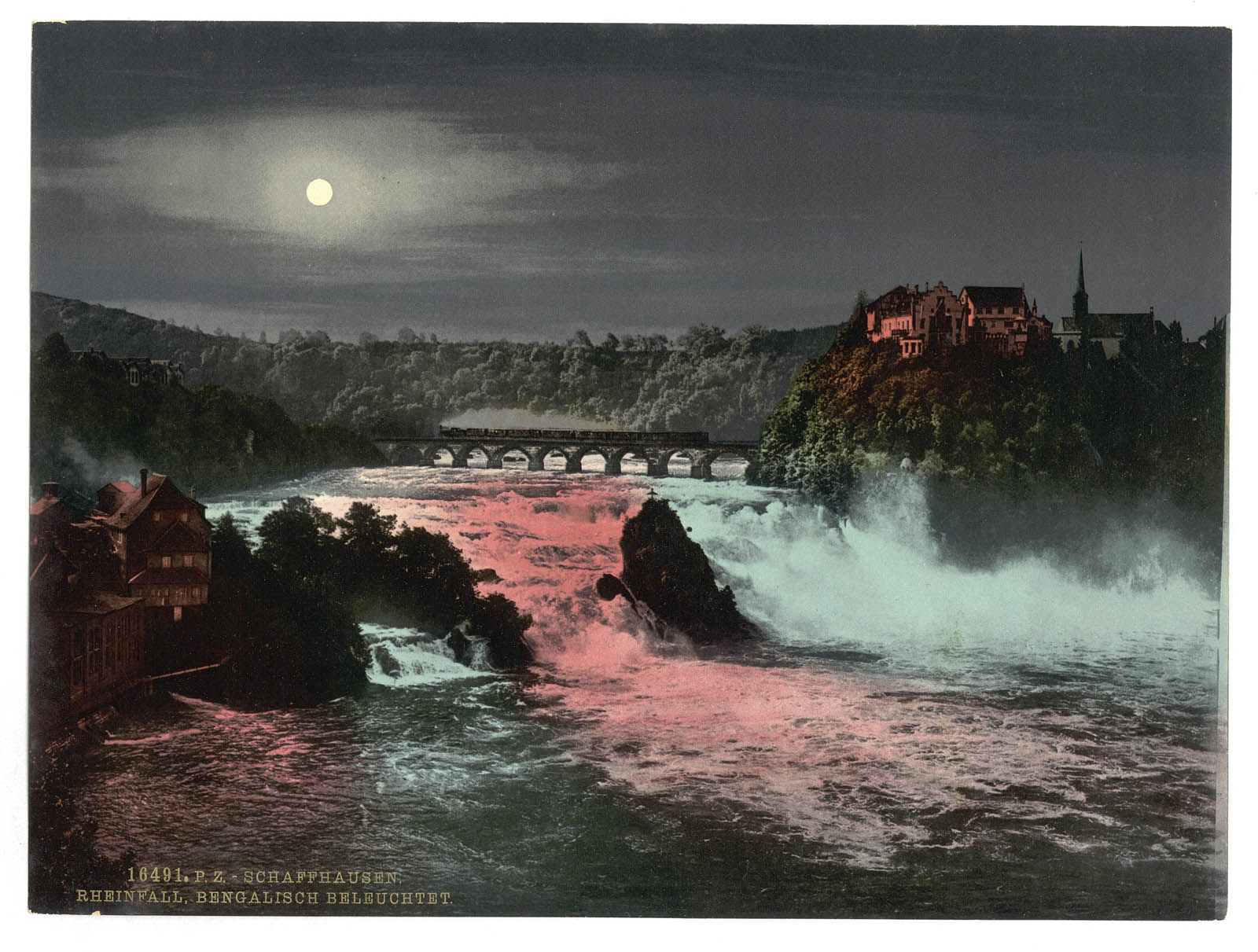

The first mention of a photo exhibition at the Städel Museum dates from all the way back to 1845, when the Frankfurt Intelligenz Blatt – the official city bulletin – ran an ad. This is the earliest known announcement of a photography show in an art museum worldwide. The 1845 exhibition featured portraits by the photographer Sigismund Gerothwohl of Frankfurt, the proprietor of one of the city’s first photo studios who has meanwhile all but fallen into oblivion. Like many other institutions at the time, the Städel Museum had a study collection which also included photographs: then Städel director Johann David Passavant began collecting photos for the museum in the 1850s. In addition to reproductions of artworks, the photographic holdings comprised genre scenes, landscapes and cityscapes by such well-known pioneers in the medium as Maxime Du Camp, Wilhelm Hammerschmidt, Carl Friedrich Mylius or Giorgio Sommer. An 1852 exhibition showcasing views of Venice launched a tradition of presentations of photographic works from the Städel’s own collection.

Whereas the photos exhibited in the Städel in the nineteenth century were contemporary works, the show Lichtbilder will focus on the development of artistic photography. The point of departure will be the museum’s own photographic holdings, which were significantly expanded through major acquisitions from the collections of Uta and Wilfried Wiegand in 2011 and Annette and Rudolf Kicken in 2013, and which continue to grow today through new purchases. The exhibition’s nine chronologically ordered sections will span the history of the medium from the beginnings of paper photography in the 1840s to the photographic experiments of the fotoform Group in the 1950s.

In the entrance area to the show, the visitor will be greeted by a selection of Raphael reproductions presented by the Städel in exhibitions in 1859 and 1860. They feature full views and details of the cartoons executed by Raphael to serve as reference images for the Sistine Chapel tapestries. The art admirer was no longer compelled to travel to London to marvel at the Raphael cartoons at Hampton Court, but could now examine these masterworks in large-scale photographs right at the Städel. The following exhibition room is devoted to the pioneers of photography of the 1840s to ’60s. No sooner had the invention of the new medium been announced in 1839 than enthusiasts set about conquering the world with the photographic image. The aspiration of the bourgeoisie for self-representation in accordance with aristocratic conventions soon rendered photographic portraiture a lucrative business; to keep up with the growing demand, the number of photo studios in the European metropolises steadily increased. Works of architecture and historical monuments, art treasures and celebrities were all recorded on film and made available to the public. Quite a few photographers – for example Édouard Baldus, the Bisson brothers, Frances Frith, Wilhelm Hammerschmidt and Charles Marville – set out on travels to take pictures of the cultural-historical sites of Europe and the Near East, and thus to capture these testimonies to the past on film.

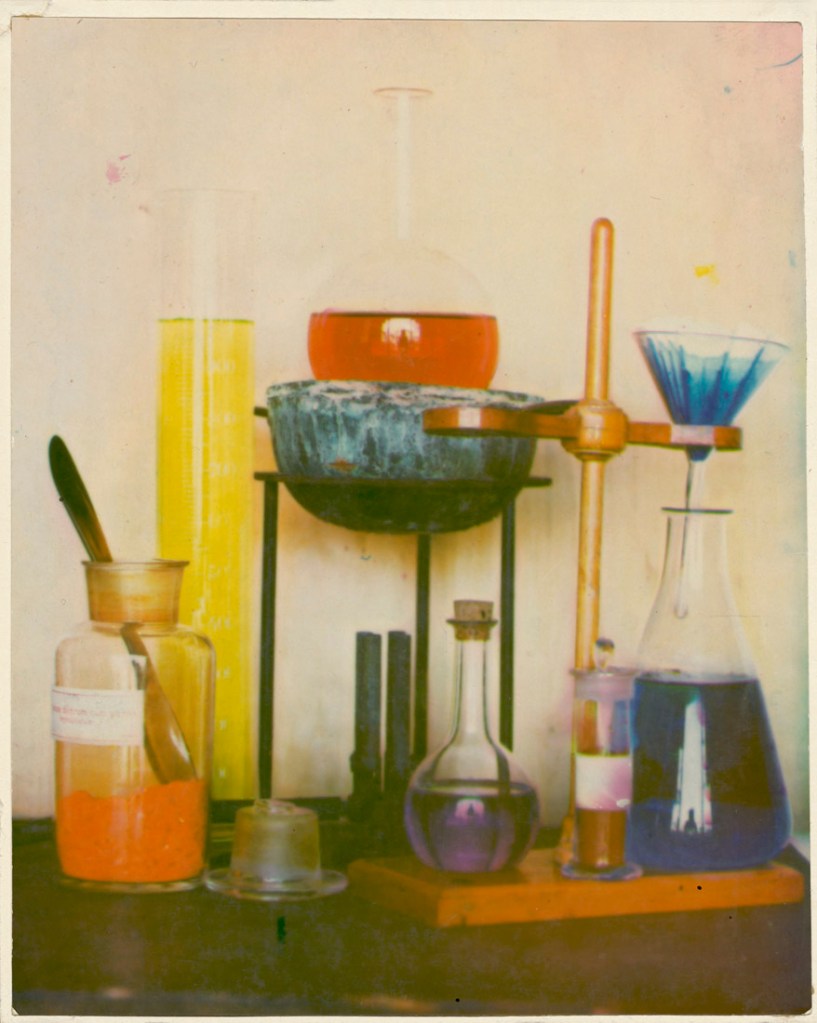

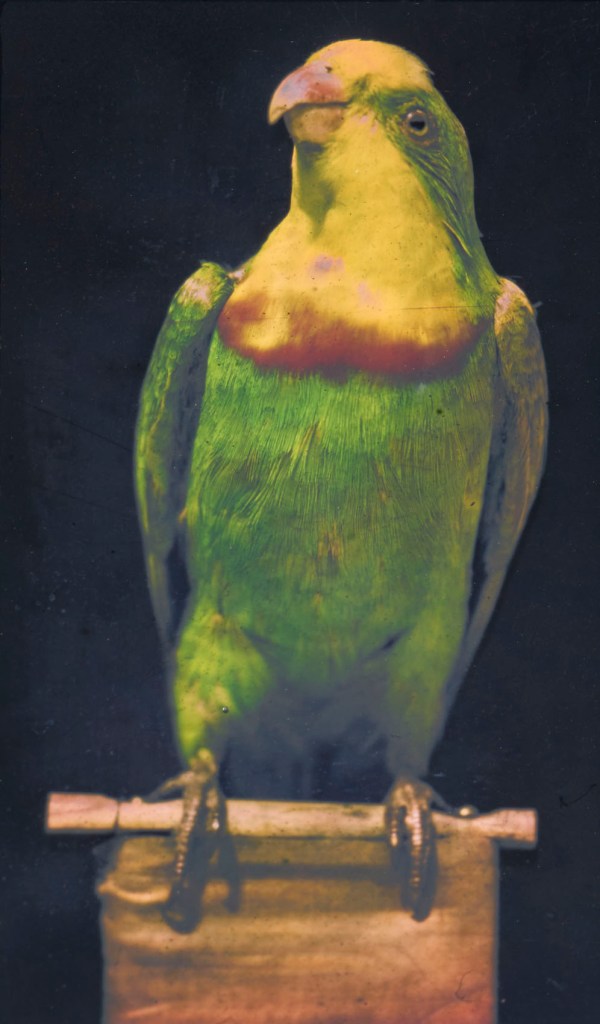

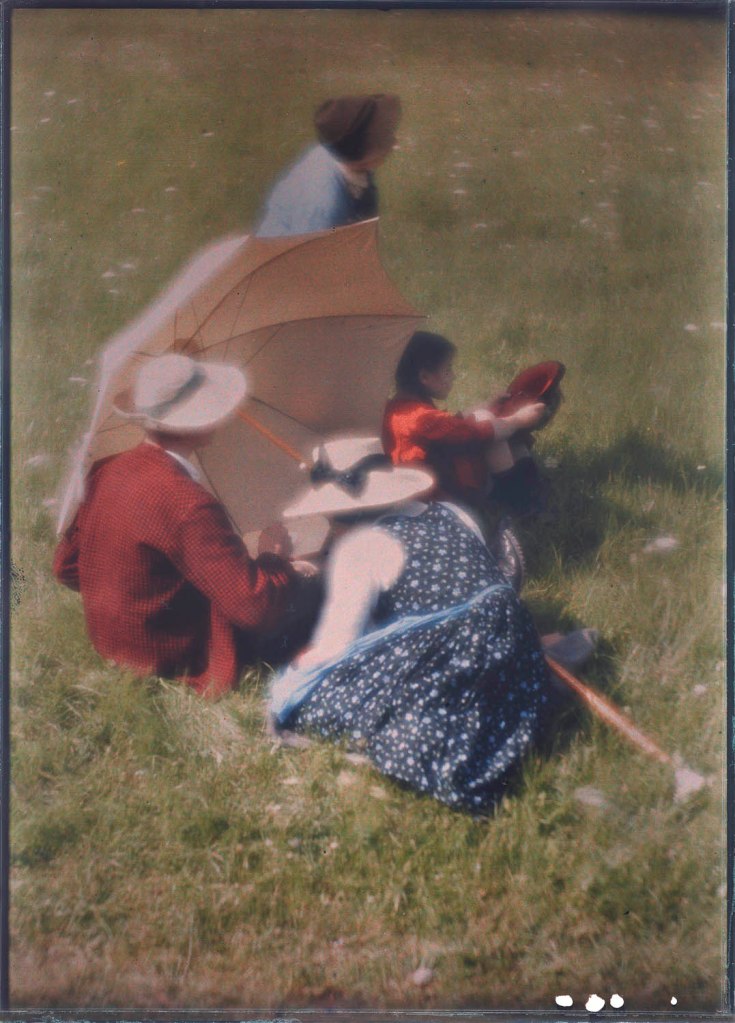

Among the most successful exponents of this genre was Georg Sommer, a native of Frankfurt who emigrated to Italy in 1856 and made a name for himself there as Giorgio Sommer. The second section of the show will revolve around the image of Italy as a kind of paradise on Earth characterised by the Mediterranean landscape and the legacy of antiquity. That image, however, would not be complete without views of the simple life of the Italian population. These genre scenes – often posed – were popular as souvenirs because they fulfilled the travellers’ expectations of encountering a preindustrial, and thus unspoiled, way of life south of the Alps. Faced with the challenges presented by the climate, the long exposure times and the complex photographic development process, photographers were constantly in search of technical improvements – as illustrated in the third section of the presentation. Léon Vidal and Carlo Naya, for example, experimented with colour photography, Eadweard Muybridge with capturing sequences of movement, and the Royal Prussian Photogrammetric Institute with large-scale “mammoth photographs.”

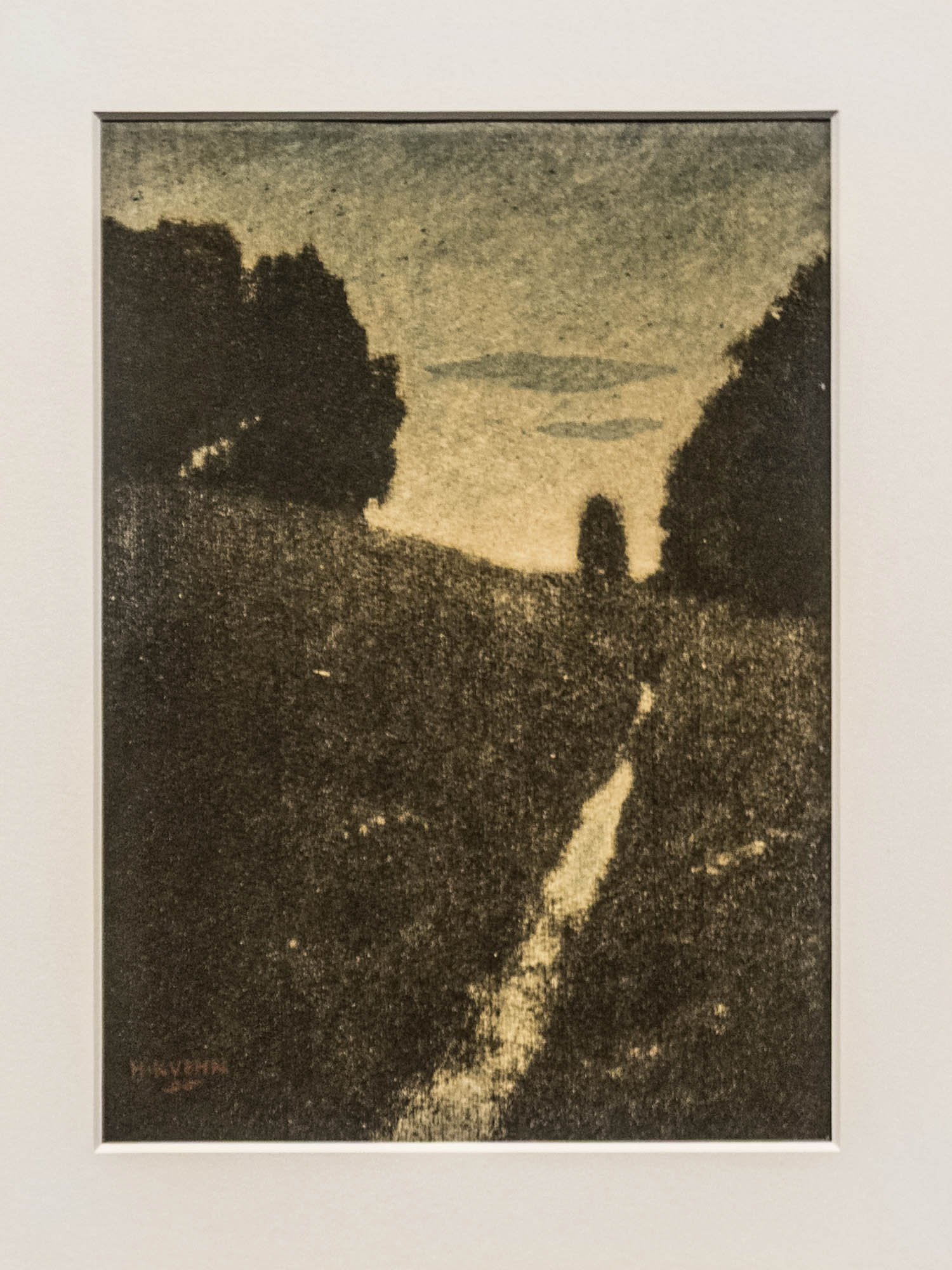

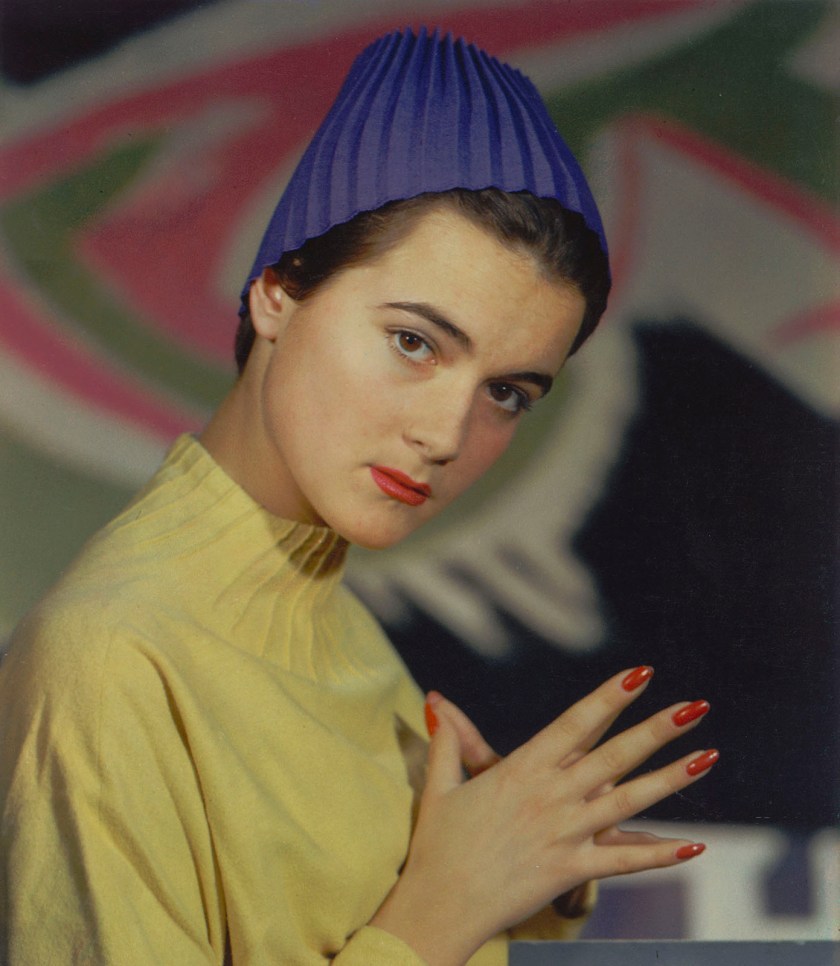

While the pictorial language of professional photography hardly advanced, increasing emphasis was placed over the years on its technical aspects. The section of the show on artistic photography demonstrates how, at the end of the nineteenth century, enthusiastic amateur photographs worked to develop the medium with regard to aesthetics as well. Whereas until that time, professional photographers had given priority to genre scenes and other motifs popular in painting, the so-called Pictorialists set out to strengthen photography’s value as an artistic medium in its own right. Atmospheric landscapes, fairy-tale scenes and stylised still lifes were captured as subjective impressions. While Julia Margaret Cameron very effectively staged dialogues between sharp and soft focus, Heinrich Kühn employed the gum bichromate and bromoil techniques to create painterly effects.

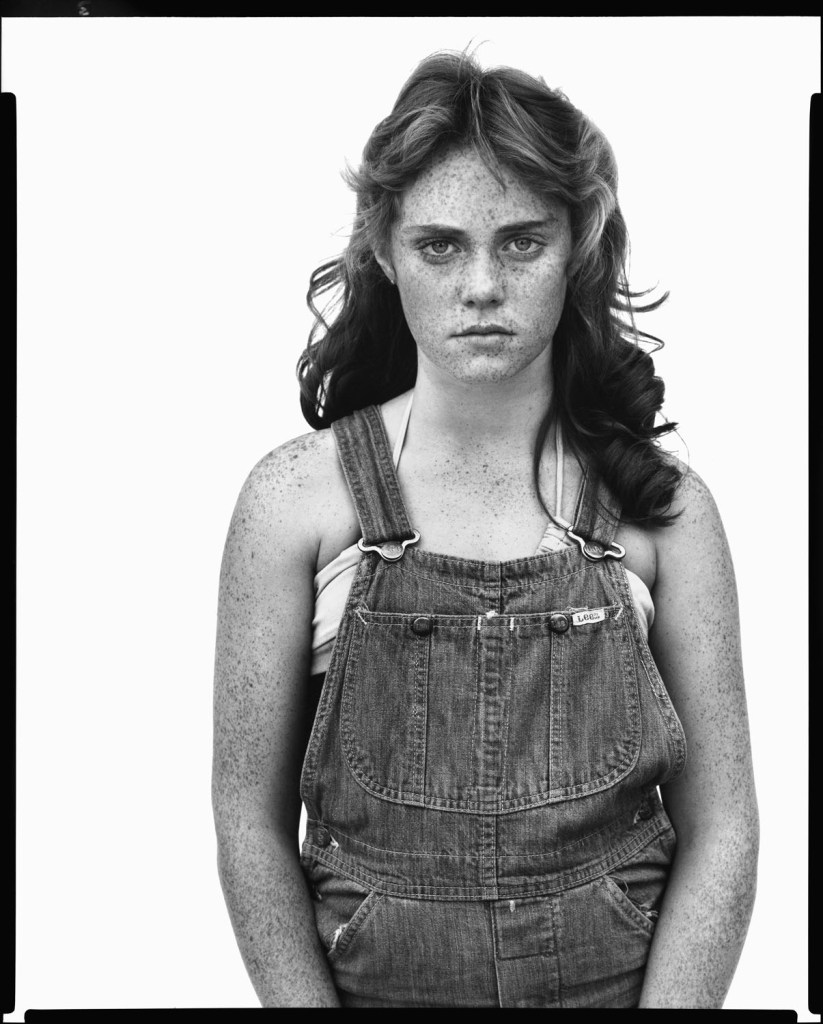

After World War I, a new generation of photographers emerged who questioned the standards established by the Pictorialists. Their works are highlighted in the following room. Rather than intervening in the photographic development process, the adherents to this new current – who pursued interests analogous to those of the New Objectivity painters – devoted themselves to austere pictorial design and sought to establish a “new way of seeing.” The gaze was no longer to wander yearningly into the distance, but be confronted directly and immediately with the realities of society. The prosaic and rigorous images of August Sander and Hugo Erfurth satisfy the demands of this artistic creed. The exhibition moreover directs its attention to early photojournalism and the development of the mass media. Apart from documentary photographs by the autodidact Erich Salomon, Heinrich Hoffmann’s portraits of Adolf Hitler – purchased for the Städel collection in 2013 – will also be on view. Although it was Hitler himself who had commissioned them, he later prohibited the portraits’ reproduction. For in actuality, Hoffmann’s images expose the hollowness of the dictator’s demeanour. The show devotes a separate room to the work of Albert Renger-Patzsch, whose formally rigorous scenes are distinguished by uncompromising objectiveness in the depiction of nature and technology.

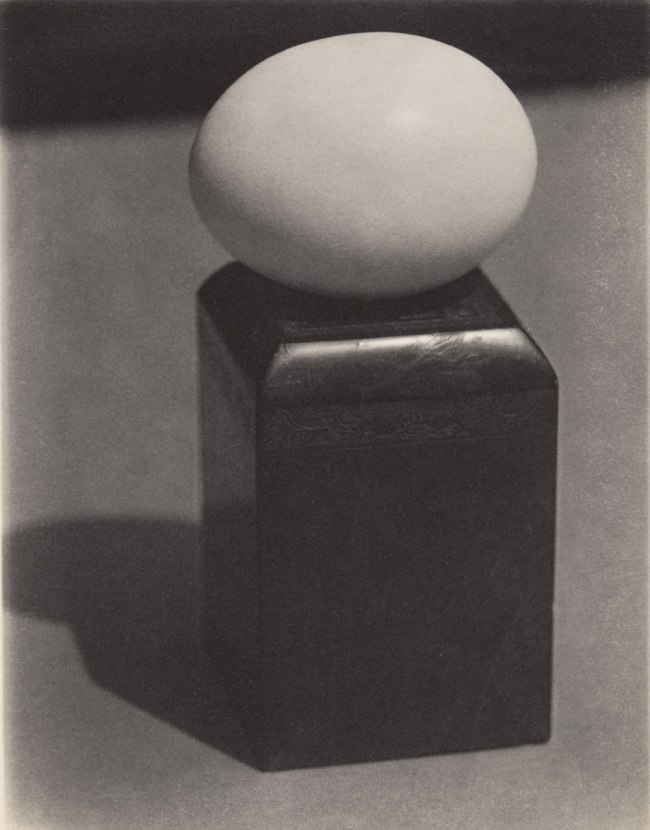

The photographers inspired by Surrealism pursued interests of a wholly different nature, as did the representatives of the Czech photo avant-garde – the focusses of the following two exhibition rooms. In the section on Surrealist photography, the works oscillate between fiction and reality, and photographic experiments unveil the world’s bizarre sides. Employing strange effects or unexpected motif combinations, artists such Brassaï, André Kertész, Dora Maar, Paul Outerbridge and Man Ray sought the unusual in the familiar. The Czech photographers of the interwar period, for their part, explored the possibilities of abstract and constructivist photography. Their works, many of which exhibit a symbolist tendency, are concerned with the aestheticisation of the world.

The final section of the show is dedicated to Otto Steinert and the fotoform Group. It sheds light on how Steinert and the members of the artists’ group took their cues from the experiments of the photographic vanguard of the 1920s, while at the same time dissociating themselves from the propagandistic and heroising use of photography during the National Socialist era. The six photographers who joined to found the fotoform Group in 1949 – Peter Keetman, Siegfried Lauterwasser, Wolfgang Reisewitz, Toni Schneiders, Otto Steinert and Ludwig Windstosser – coined the term “subjective photography” and emphasised the photographer’s individual perspective.

The show augments the joint presentation of photography, painting and sculpture practised at the Städel Museum since its reopening in 2011 and also to be continued during and after Lichtbilder. The aim of this exhibition mode is to convey the decisive role played by photography in art-historical pictorial tradition since the medium’s very beginnings. The presentation is being accompanied by a catalogue which – like the exhibition architecture – foregrounds the specific “palette” of photography as a medium conducted in black and white. The subtle tones of grey are mirrored not only in the works’ reproductions, but also in the colour design of the individual catalogue sections. When the visitor enters the exhibition space, he is surrounded by an architecture that is grey to the core, while at the same time making clear that no one shade of grey is like another. In the words of curator Felicity Grobien: “The exhibition reveals how multi-coloured the prints are, for in them – contrary to what we expect from black-and-white photography – we discover a vast range of subtle colour nuances that emphasise the prints; distinctiveness.

Press release from the Städel Museum

Édouard Baldus (French, 1813-1889)

Orange: The Wall of the Théâtre antique

1858

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

43.4 x 33.4cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

Werner Mantz (German, 1901-1983)

Cologne: Bridge

c. 1927

Gelatin silver print on baryta paper

16.7 x 22.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Werner Mantz began his career as a portrait and advertising photographer, later becoming known for his architectural photographs of the modernist housing projects in Cologne during the 1920s. This portfolio of photographs was selected by the artist towards the end of his life as representative of his finest work. These rare prints reveal Mantz’s mastery in still-life and architecture photography, and are considered some of the most influential works created in the period.

Text from the Tate website

Carlo Naya (Italian, 1816-1882)

Venice: View of the Marciana Library, the Campanile and the Ducal Palace

c. 1875

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

41.3 x 54.1cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

Carlo Naya (1816, Tronzano Vercellese – 1882, Venice) was an Italian photographer known for his pictures of Venice including its works of art and views of the city for a collaborative volume in 1866. He also documented the restoration of Giotto’s frescoes at the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Naya was born in Tronzano di Vercelli in 1816 and took law at the University of Pisa. An inheritance allowed him to travel to major cities in Europe, Asia, and northern Africa. He was advertising his services as portrait photographer in Istanbul in 1845, and opened his studio in Venice in 1857. He sold his work through photographer and optician Carlo Ponti. Following Naya’s death in 1882, his studio was run by his wife, then by her second husband. In 1918 it was closed and publisher Osvaldo Böhm bought most of Naya’s archive.

Text from Wikipedia website

Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966)

Buchenwald in November

c. 1954

Gelatin silver print

16.5 x 22.4cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

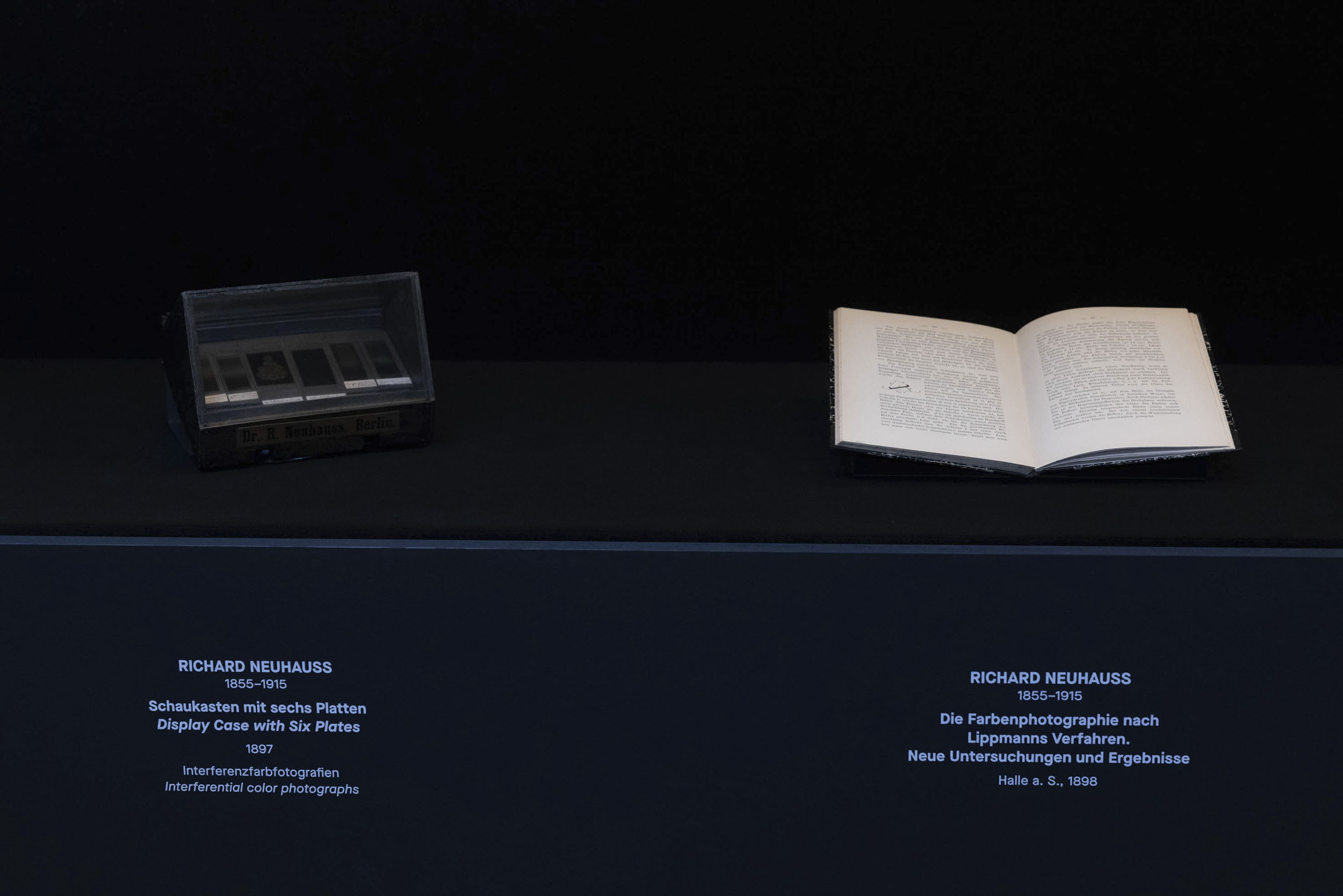

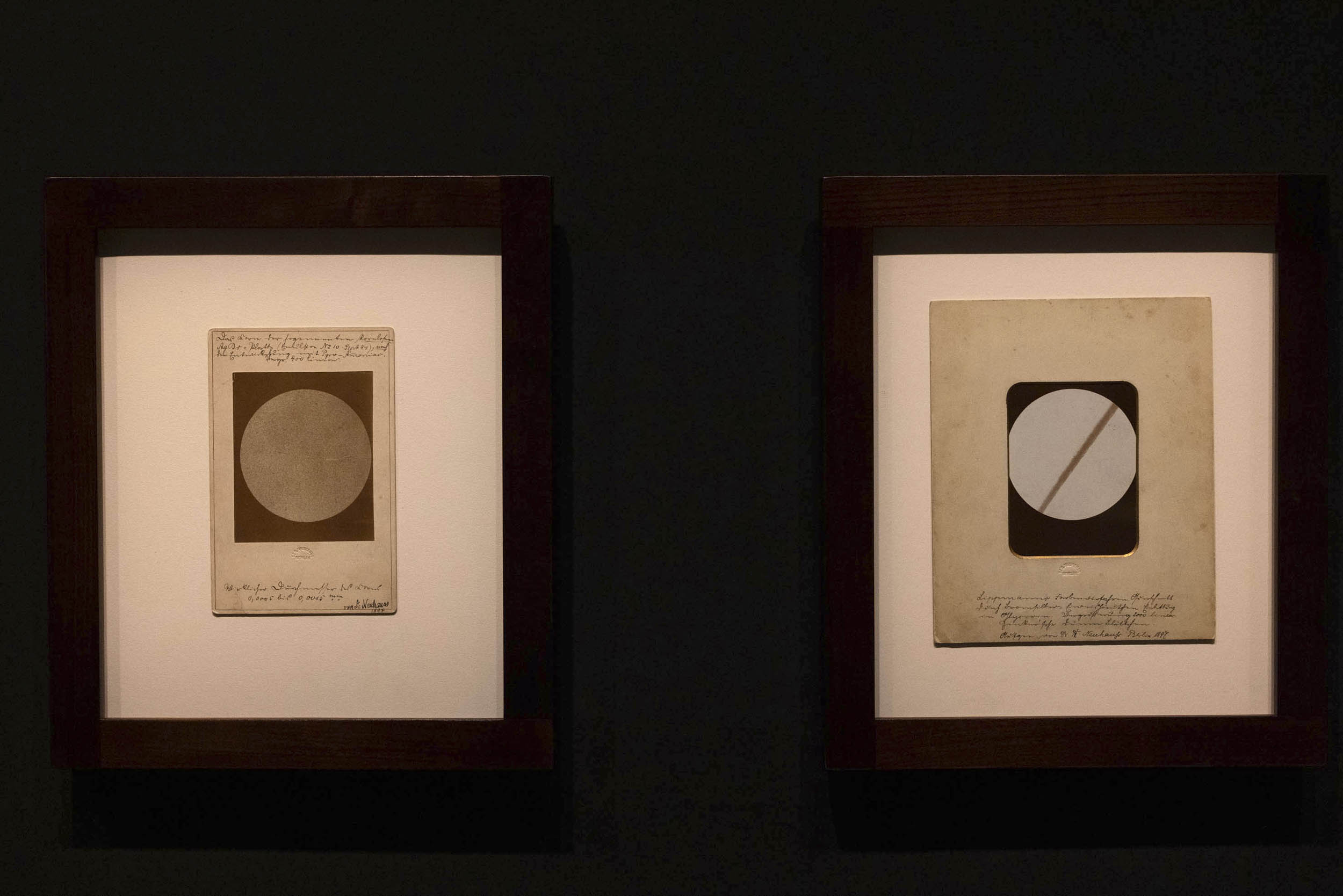

Royal Prussian Institute of Survey Photography (est. 1885)

Cologne: Cathedral

1889

Gelatin silver prints mounted on cardboard

79.8 x 64.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

Otto Steinert (German, 1915-1978)

Luminogram

1952

Gelatin silver print on baryta paper mounted on cardboard

41.5 x 59.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© Nachlass Otto Steinert, Museum Folkwang, Essen

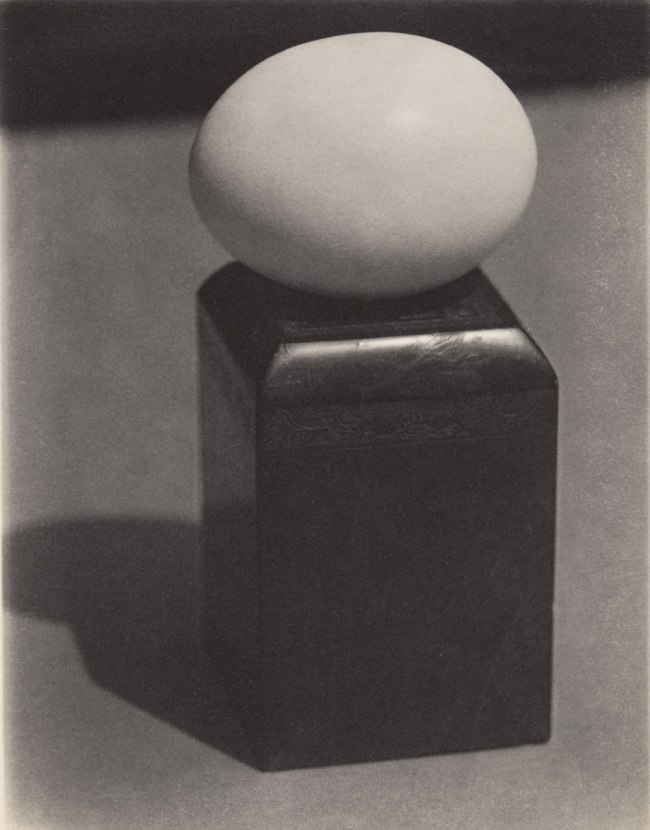

Paul Outerbridge (American, 1896-1958)

Egg on Block

1923

Platinum print

11.9 x 9.4cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© Paul Outerbridge, Jr., © 2014 G. Ray Hawkins Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA

Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966)

Untitled (Close-up of a Zip Fastener)

1928-1933

Gelatin silver print

23 x 16.9cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Mrs Herbert Duckworth

1867

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

35 x 27.1cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

Giorgio Sommer (European, 1834-1914)

Naples: Delousing

c. 1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

25.5 x 20.6cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Alexandra “Xie” Kitchin as Chinese “Tea-Merchant” (on Duty)

1873

Albumen print

19.8 x 15.2cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

Additional images

Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966)

Tropical Orchis, cattleya labiata

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print, printed c. 1930

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Schwarz und Weiß (Black and white)

1926 (printed 1993 by Pierre Gassmann)

Silver gelatin print

24.8 x 35.3cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Photo: Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Retour à la Raison (Return to Reason)

1923 (printed c. 1979 from Pierre Gassmann)

Gelatin silver print

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2013 as a gift from Annette and Rudolf Kicken

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2013

Václav Jíru (Czech, 1910-1980)

Untitled (Sunbath)

1930s

Gelatin silver print

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2013 as a gift from Annette and Rudolf Kicken

Jíru started to shoot as an amateur photographer, and since 1926 published photos and articles. He first exhibited in 1933 and collaborated with the Theatre Vlasta Burian, photographed in the Liberated Theatre, was devoted to advertising photography, and became well known in the international press (London News, London Life, Picture Post, Sie und Er, Zeit im Bild).

In 1940 he was arrested by the Gestapo for resistance activities, and sentenced to life in prison by the end of the war. In the book Six Spring, where there are pictures taken shortly after liberation, he described his experience of prison and concentration camps. After the war he became a member of the Union of Czechoslovak Journalists and in 1948 a member of the Association of Czechoslovak Artists. He continued shooting, but also looking for new talented photographers. In 1957, he founded and led four languages photographic Revue Photography. By the end of his life he organised a photographic exhibition and served on the juries of photographic competitions.

The photographs of Václav Jírů, especially in the pre-war stage, was very wide: sports photography, theatrical portrait, landscape, nude, social issues, report. After the war he concentrated on the cycles of nature, landscapes and cities. A frequent theme of his photographs was Prague, which unlike many other photographers he photographed in its unsentimental everyday life (Prague mirrors, walls Poetry Prague, Prague ghosts).

Text translated from Czech Wikipedia website

Werner Mantz (German, 1901-1983)

Förderturm – Im Auftrag der Staatsmijnen Heerlen/Niederlande (Headframe – On behalf of the States Mine Heerlen / Netherlands)

1937

Gelatin silver bromide print

22.6 x 16.7cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2013

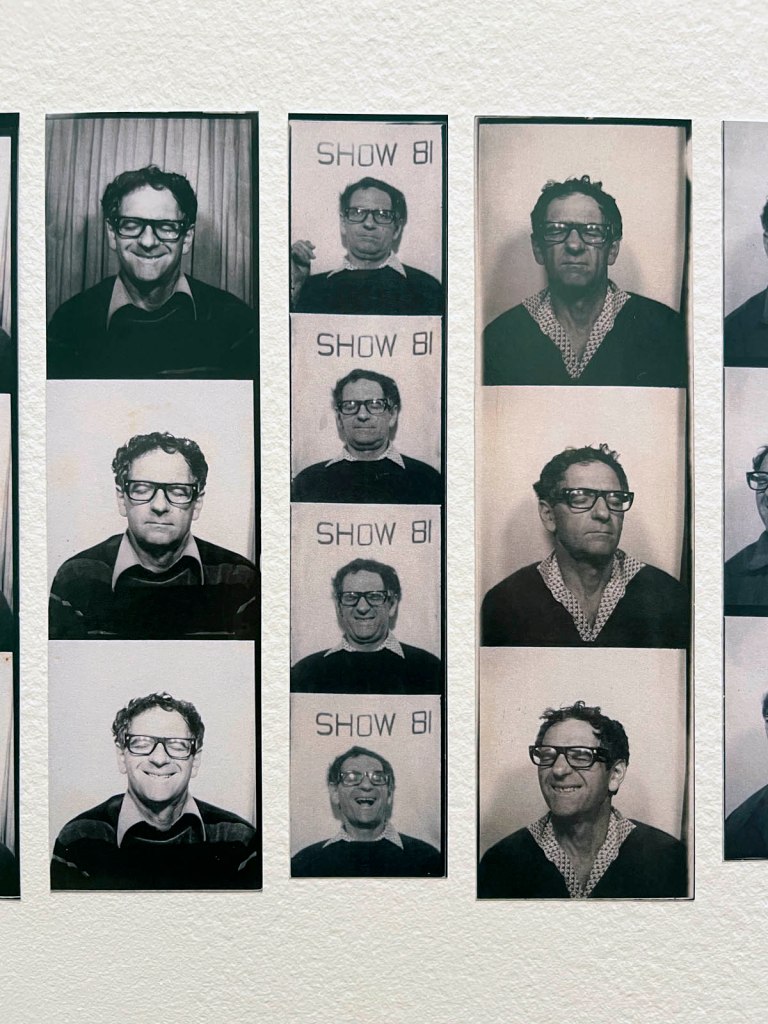

Václav Chochola (Czech, 1923-2005)

Kolotoc-Konieci (merry-go-round horse)

c. 1958

Gelatin silver print

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2013 as a gift from Annette and Rudolf Kicken

Chochola (January 31, 1923 in Prague – August 27, 2005) was a Czech photographer, known for classic Czech art and portrait photography. He began photography while studying at grammar school in Prague-Karlin. After leaving the photographer taught and studied at the School of Graphic Arts. He was a freelance photographer, photographed at the National Theatre and has collaborated with many other scenes. Chochol created a series of images using non-traditional techniques, creating photograms, photomontage and roláže.

In his extensive work Chochol was devoted to candid photographs, portraits of celebrities (famous for his portrait of Salvador Dali), acts or sports photography. His documentary images from the Prague uprising in May 1945 are invaluable. In 1970 Chochol spent a month in custody for photographing the grave of Jan Palach. He died after a brief serious illness in Motol Hospital in Prague.

Text translated from Czech Wikipedia website

Jde užasle světem, o kterém jako kluk na předměstí snil a od něhož byl vždy oddělen červenou šňůrou, a do něhož má najednou přístup. Skutečnost, že v tomto světě nikdy nebyl úplně doma, dokázal proměnit v nepřehlédnutelnou přednost: zbystřilo mu to oko a zahlédl detaily, které my oslněni jinými cíli ani nevidíme.

He walks in amazement through the world he dreamed of as a boy in the suburbs, and from which he was always separated by a red cord, and to which he suddenly has access. He was able to turn the fact that he was never quite at home in this world into an unmissable advantage: it sharpened his eye and he saw details that we, dazzled by other goals, don’t even see.

Frantisek Drtikol (Czech, 1883-1961)

Crucified

before 1914 (printed before 1914)

Gelatin silver print

22.7 x 17.3cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2013 as a gift from Annette and Rudolf Kicken

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2013

František Drtikol (3 March 1883, Příbram – 13 January 1961, Prague) was a Czech photographer of international renown. He is especially known for his characteristically epic photographs, often nudes and portraits.

From 1907 to 1910 he had his own studio, until 1935 he operated an important portrait photostudio in Prague on the fourth floor of one of Prague’s remarkable buildings, a Baroque corner house at 9 Vodičkova, now demolished. Jaroslav Rössler, an important avant-garde photographer, was one of his pupils. Drtikol made many portraits of very important people and nudes which show development from pictorialism and symbolism to modern composite pictures of the nude body with geometric decorations and thrown shadows, where it is possible to find a number of parallels with the avant-garde works of the period. These are reminiscent of Cubism, and at the same time his nudes suggest the kind of movement that was characteristic of the futurism aesthetic.

He began using paper cut-outs in a period he called “photopurism”. These photographs resembled silhouettes of the human form. Later he gave up photography and concentrated on painting. After the studio was sold Drtikol focused mainly on painting, Buddhist religious and philosophical systems. In the final stage of his photographic work Drtikol created compositions of little carved figures, with elongated shapes, symbolically expressing various themes from Buddhism. In the 1920s and 1930s, he received significant awards at international photo salons.

Text from Wikipedia website

Städel Museum

Schaumainkai 63

60596 Frankfurt

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 10.00am – 6.00pm

Thursday 10.00am – 9.00pm

Closed Mondays

Städel Museum website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010) 'Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969' [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969] 1969 Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010) 'Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969' [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969] 1969](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/2-typologien_heinrich-riebesehl_siae_sm.jpg)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin)' c. 1864 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin)' c. 1864](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/nadar-george-sand.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.