Exhibition dates: 11th March – 4th August 2024

Curator: Virgina McBride, Research Associate in the Department of Photographs at The Met

Anton Bruehl (American born Australia, 1900-1982)

Four Roses Whiskey: Worth Reaching For

1949

Laminated photomechanical printer’s proof

26.1 x 27.4cm (10 1/4 x 10 13/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© Estate of Anton Bruehl

Meticulously staged by the pioneering colour photographer Anton Bruehl, this work was part of a series showing the whiskey in many exciting scenarios: the glass appeared to travel by train and cruise liner, as well as hot air balloon. Bruehl’s pictures ran as ads in LIFE and Newsweek, conjuring worldly associations for his client, the Kentucky distiller Four Roses.

Against all odds, these eye-catching scenes were not darkroom fabrications – Bruehl arranged them by hand, with the help of miniaturists, set dressers, and a celebrity florist.

Testing appetites for novelty, illusion, and abundance against the limits of good taste, he wagered that this crisp construction would quench your thirst, then melt into hot air.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art Instagram page

Anton Bruehl was born in 1900 of German émigré parents in the small town of Hawker, Australia. By 1919, when he moved to the United States to work as an electrical engineer, he was a skilled amateur photographer. A show of student work from the Clarence H. White School of Photography at the Art Center, New York, in 1923 convinced Bruehl to quit his engineering job to become a photographer. White taught Bruehl privately for six months and then asked him to teach at his school, including its summer sessions in Maine. White’s sudden death, in 1925, prompted Bruehl to open a studio, at first partnering with photographer Ralph Steiner and then with his older brother, Martin Bruehl; it was immediately successful. Specializing in elaborately designed and lit tableaux, Bruehl won top advertising awards throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s. A favourite of Condé Nast Publications, he developed the Bruehl-Bourges colour process with colour specialist Fernand Bourges, which gave Condé Nast a monopoly on colour magazine reproduction from 1932 to 1935.

Text from the MoMA Object: Photo website

What a thoughtful, stimulating and well presented exhibition which contains some absolutely beautiful product photographs. These photographs awaken in the consumer a desire to possess the object of the camera’s attention, the aesthetisication of the object as a form of “readymade” available for immediate consumption.

It’s such a pity that for some of sections – such as “The Array”, “The Montage”, and “The Ideal user” – I only have one or two media image to illustrate the theme.

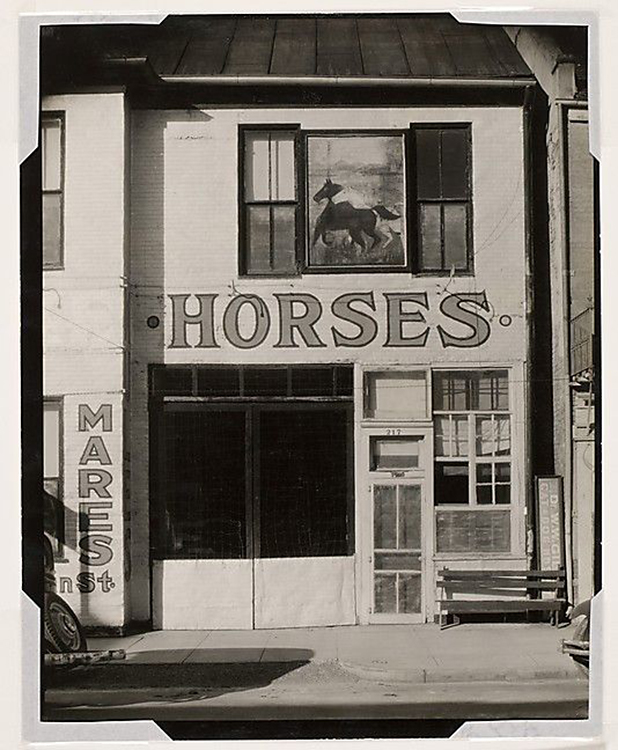

I have included in the posting a wonderful photograph from my own collection – a postcard with a real photograph on the front by an unknown photographer, showing a proprietor standing by the front door of his shop advertising the wares for “Howard, Watchmaker & Jeweller”, no date – probably British from 1890s-1910s due to his attire, the typeface on the front of the shop, and how “jewellery” is spelt. In the window there is an effusive display of clocks, watches, rings and Prince Albert watch chains.

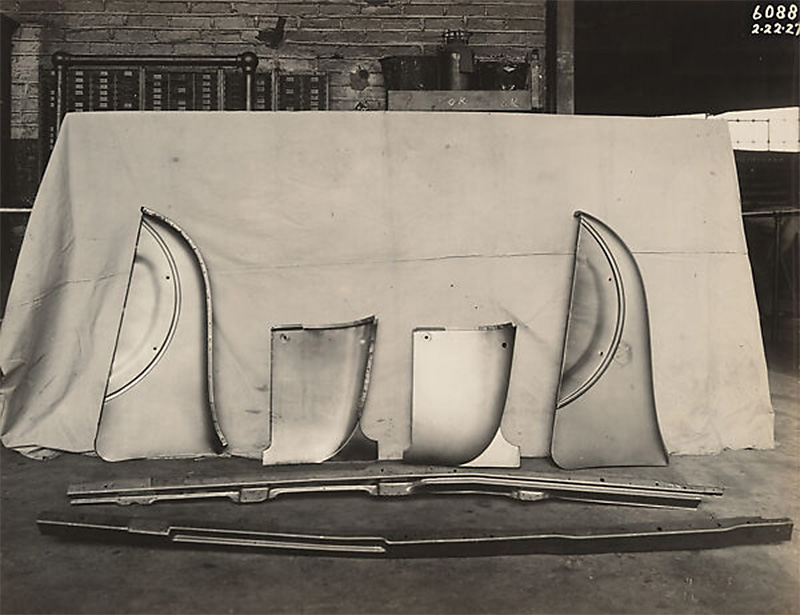

My favourite photographs in the posting are the portrait of The Silver Merchants (c. 1850, below); the photograph of a tombstone from the Vermont Marble Tombstone Catalogue (1880s, below); the hand-coloured photograph by the Schadde Brothers of High Grade Jelly Eggs, from a Brandle & Smith Co. Catalogue (c. 1915, below); and the sublime Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Co. photograph Automotive Component (February 22, 1927, below)

Through these product photographs we begin to understand how, “The conventions of the past inform these norms and explain the advertisements that we see in our daily lives.” And how we have lost that spark of creativity, use of colour and form and appreciation of beauty in product photography that was the essence of what has gone before.

For those that are interested, I have included some expressive quotations on the complexity of the relationship between the construction of the self, commodities and consumer culture at the bottom of the posting.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Consumer capitalism, with its efforts to standardise consumption and to shape tastes through advertising, plays a basic role in furthering narcissism. The idea of generating an educated and discerning public has long since succumbed to the pervasiveness of consumerism, which is a ‘society dominated by appearances’. Consumption addresses the alienated qualities of modern social life and claims to be their solution: it promises the very things the narcissist desires – attractiveness, beauty and personal popularity – through the consumption of the ‘right’ kinds of goods and services. Hence all of us, in modern social conditions, live as though surrounded by mirrors; in these we search for the appearance of an unblemished, socially valued self.”

Anthony Giddens. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. California: Stanford University Press, 1991, p. 172.

Unknown photographer (Brtish?)

Howard – Watchmaker and Jeweller (front and verso)

1890s-1910s?

Silver gelatin photograph on postcard

Collection of Marcus Bunyan

This photograph is not in the exhibition

“”Product photography is, now, completely inescapable – it follows you around and stalks you on social media – and that condition is very interesting,” said [curator] McBride. The conventions of the past inform these norms and explain the advertisements that we see in our daily lives…

When I visited the exhibition, I was lucky enough to meet Drew, an advertisement photographer who spoke to me about her impressions of The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography. “As someone who works in advertising photography, I find it quite interesting how I think we’ve lost some of the creativity that I see here in this imagery, as far back as the 1920s. It makes me wonder about how I could implement or think about new ways of composition or exploring basic objects in a more exciting way. I’m curious about how these objects were received as advertisements back then. Now, I think we see them more as fine art, so it is interesting to think about what our advertising images could look like twenty years from now.” Drew was strong in her belief that much of the beauty and wonder of advertisement photography has been lost over the decades.

In the 1920s, rising industrial output and consumer demand led executives to seek ways to make their products stand out in a crowded market. Applied psychology shifted managers’ focus to the consumer’s mind, emphasizing the need to persuade consumers that they could find individuality and personal meaning in standardized goods. Consumers “believe what the camera tells them because they know that nothing tells the truth so well.” …

The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography exposes the truth in an entirely new way. It exposes the secrets of photography and how the truth shifted through years of capitalism and consumerism, demanding different sales strategies from producers… [By the 1950s] As the American capitalist market demanded printed ads and mass consumption increased, photographers lost their creative control, with advertisement directors taking up the mantle. There is a straightforward appeal and very little left to the imagination.”

Ayana Chari. “A Review of the Met Museum’s ‘The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography’,” on The Science Survey website July 10, 2024 [Online] Cited 26/07/2024

The photographs in this exhibition do not depict rare or special things. They show toothpaste, tombstones, and hats. But these familiar trappings of everyday life will be, at times, unrecognisable – so altered by the camera as to constitute something entirely new. Enticing consumers with increasingly experimental approaches to the still life genre, the photographs featured transform everyday objects into covetable commodities. The camera abstracts them from functional use, at times distorting them through dizzying perspectives and modulations of scale. Spanning the first century of photographic advertising, the exhibition will illustrate how commercial camerawork contributed to the visual language of modernism, suggesting new links between the promotional strategies of vernacular studios and the tactics of the interwar avant-garde. Corporate commissions by celebrated innovators, including Paul Outerbridge, August Sander, and Piet Zwart, will appear alongside obscure catalogues and trade publications, united by a common cause: to snatch the ordinary out of context, and sell it back at full price.

The exhibition is made possible by The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Installation views of the exhibition The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York showing at right in the bottom image, introductory wall text to the exhibition (below) and F. D. Hampson’s Panama Hats, from a Sloan-Force Co. Catalogue (c. 1916, below)

Introduction to the exhibition

The photographs in this exhibition do not depict rare or special things. They show toothpaste, tombstones, and hats. But here these familiar trappings of everyday life are, at times, unrecognisable – so altered by the camera as to constitute something entirely new. The Real Thing charts these tactics across the first century of photographic advertising.

If functional objects can be difficult to see, the camera is uniquely equipped to bring them into focus. Excised from mundane contexts and ushered into the studio, they assume new allure, independent of their value or means of production. For early retailers and ad agencies, photography bolstered consumer confidence; the medium offered unprecedented realism, and better still, an aura of truth. Beginning in the late 1850s, new demand for manufactured goods subsidised commercial photography, and the industry grew quickly, spurred by evolving technologies of image reproduction. In the decades that followed, photographers’ increasingly experimental still lives adapted modernism for the mass market.

In the spirit of early photo manuals and how-to guides, the exhibition unfolds thematically, exploring a range of approaches to what is today termed product photography. Pictures from across the commercial section – made in storerooms, corporate studios, and avant-garde ateliers – entice buyers and invent needs, transforming everyday objects into covetable commodities. Works by celebrated innovators appear here alongside obscure catalogues and trade publications, united by a common cause to snatch the ordinary out of context and sell it back at full price.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation views of the exhibition The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York showing at right, Irving Penn’s Theatre Accident, New York (1947)

The Inventory

Installation view of the exhibition The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York showing the section The Inventory including at second left, Fashions 1837-1887, by William Charles Brown (1888, below); and at third right, Vermont Marble Tombstone Catalogue (1880s, below)

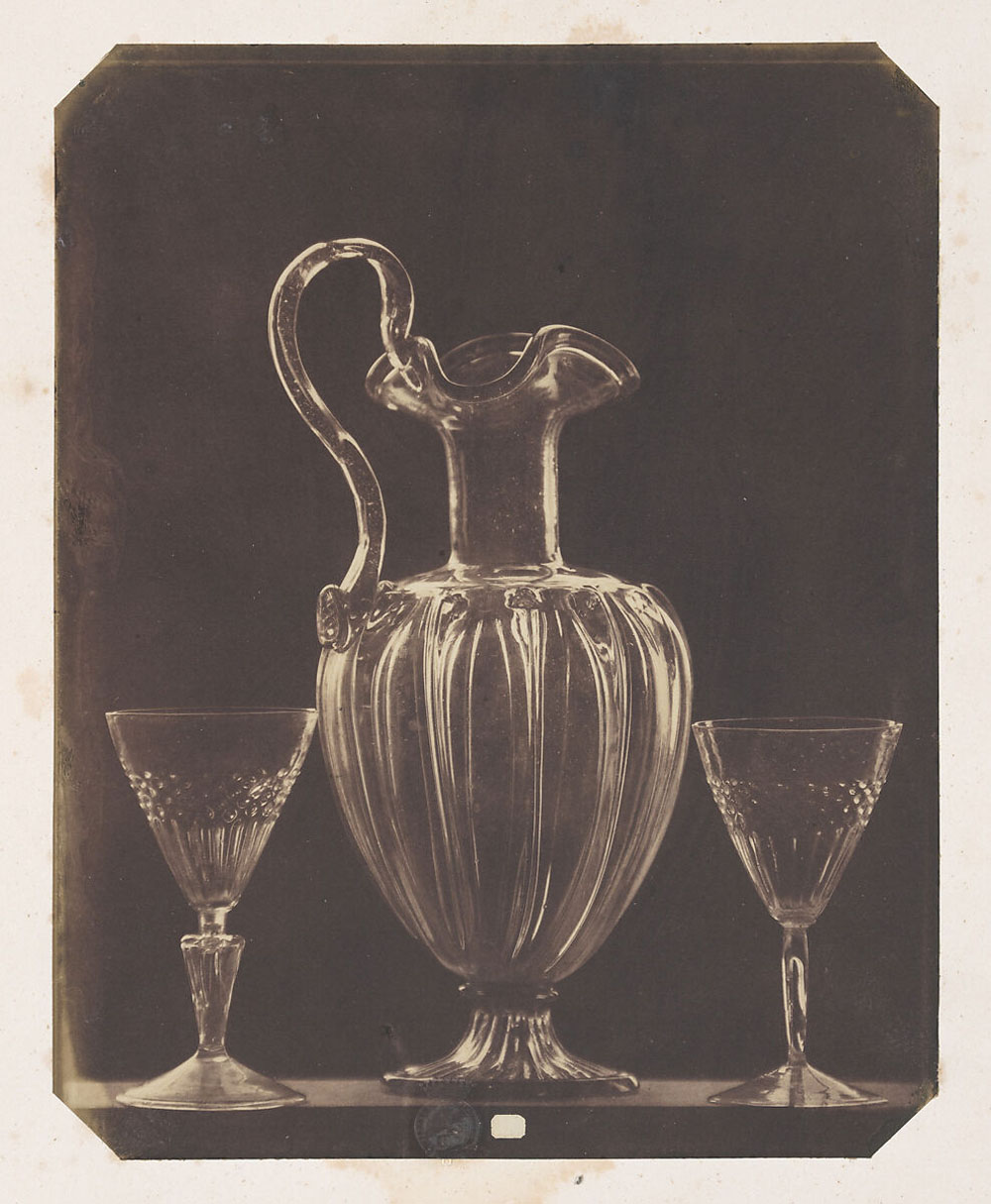

William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877)

Articles of Glass

before June 1844

Salted paper print from paper negative

Image: 13.2 x 15.1 cm. (5 3/16 x 5 15/16 in.)

Frame: 14 3/4 x 14 3/4 in.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, and Harrison D. Horblit Gift, 1988

Public domain

Talbot’s negative-positive photographic process, first made public in 1839, would change the dissemination of knowledge as had no other invention since movable type. To demonstrate the paper photograph’s potential for widespread distribution – its chief advantage over the contemporaneous French daguerreotype – Talbot produced The Pencil of Nature, the first commercially published book illustrated with photographs. With extraordinary prescience, Talbot’s images and brief texts proposed a wide array of applications for the medium, including portraiture, reproduction of paintings, sculptures, and manuscripts, travel views, visual inventories, scientific records, and essays in art.

This photograph and the plate preceding it, “Articles of China,” were offered as examples of photography’s usefulness as a tool for creating visual inventories of unprecedented accuracy. Talbot wrote: “The articles presented on this plate are numerous: but, however numerous the objects – however complicated the arrangement – the Camera depicts them all at once.”

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Unknown photographer (American)

Case manufactured by Hiram Studley (American, active 1840s)

The Silver Merchants

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

Image: 2 3/16 × 2 3/4 in. (5.5 × 7cm)

Case: 3 1/8 × 3 11/16 × 9/16 in. (8 × 9.3 × 1.5cm)

Approx. 6 1/2 x 3 1/2 in. open

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Joyce F. Menschel Gift, 2017

Public domain

The first product photographs doubled as portraits. Posing with their wares, peddlers demonstrated a standard of work and an assurance of quality. The daguerreotype, a direct-positive image on silver-plated copper, offered all manner of workers an increasingly affordable likeness. Here, silver dealers make the most of the medium, modelling careful attention to their inventory. They examine pocket watches, pendants, and fobs splayed in a sales case. Plying their trade before the camera, they mirror the work of the era’s newest silver merchants: photographers themselves.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Ludwig Belitski (German, 1830-1902)

Pitcher and Two Glasses, Venetian, 15th Century

1854

Salted paper print from glass negative

8 3/4 × 6 15/16 in. (22.2 × 17.7cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Fund, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2016

Public domain

Charles Nègre (French, 1820-1880)

[Plaster Casts of Bishops’ Miters, South Porch, Chartres]

c. 1855

Salted paper print from paper negative

Image: 22 x 32.5cm (8 11/16 x 12 13/16 in.)

Frame: 18 1/2 x 22 1/2 in.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Howard Gilman Foundation Gift, 2002

Public domain

When early photographers turned to the material world of things, it was often to document property or record cultural heritage. Their efforts reveal the camera’s remarkable capacity to abstract and transform the objects before its lens. In 1855, Charles Nègre accepted a commission to make architectural studies of Chartres Cathedral as part of a larger initiative to preserve and promote French patrimony. A complement to his sweeping views of sculpted facades, this still life monumentalises the site’s smaller details. It shows plaster replicas of ecclesiastical headgear, taken from the cathedral exterior. These are simulacra of simulacra, yet Nègre recasts them anew, registering their textured surfaces in a splendid study of shadow and mass.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Unknown maker (American)

Man Demonstrating Patent Model for Sash Window

Late 1850s-1860s

Tintype with applied colour

4.8 x 3.6cm (1 7/8 x 1 7/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bequest of Herbert Mitchell, 2008

Public domain

Pine & Bell (photographic studio) (American, active 1860s, Troy, New York)

William H. Bell (American born England, Liverpool 1831-1910 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

George W. Pine (American, active 1860s, Troy, New York)

[Display of Hats and Accessories of 1868]

1868

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Image: 3 9/16 × 2 1/8 in. (9 × 5.4 cm)

Mount: 3 11/16 in. × 2 3/8 in. (9.3 × 6 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

William L. Schaeffer Collection, Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

Unknown photographer

[E. Adkins Gun Merchant]

c. 1874

Ambrotype

6.3 x 7.5cm (2 1/2 x 2 15/16 in.) visible

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gift of Charles Wilkinson, 1965

Public domain

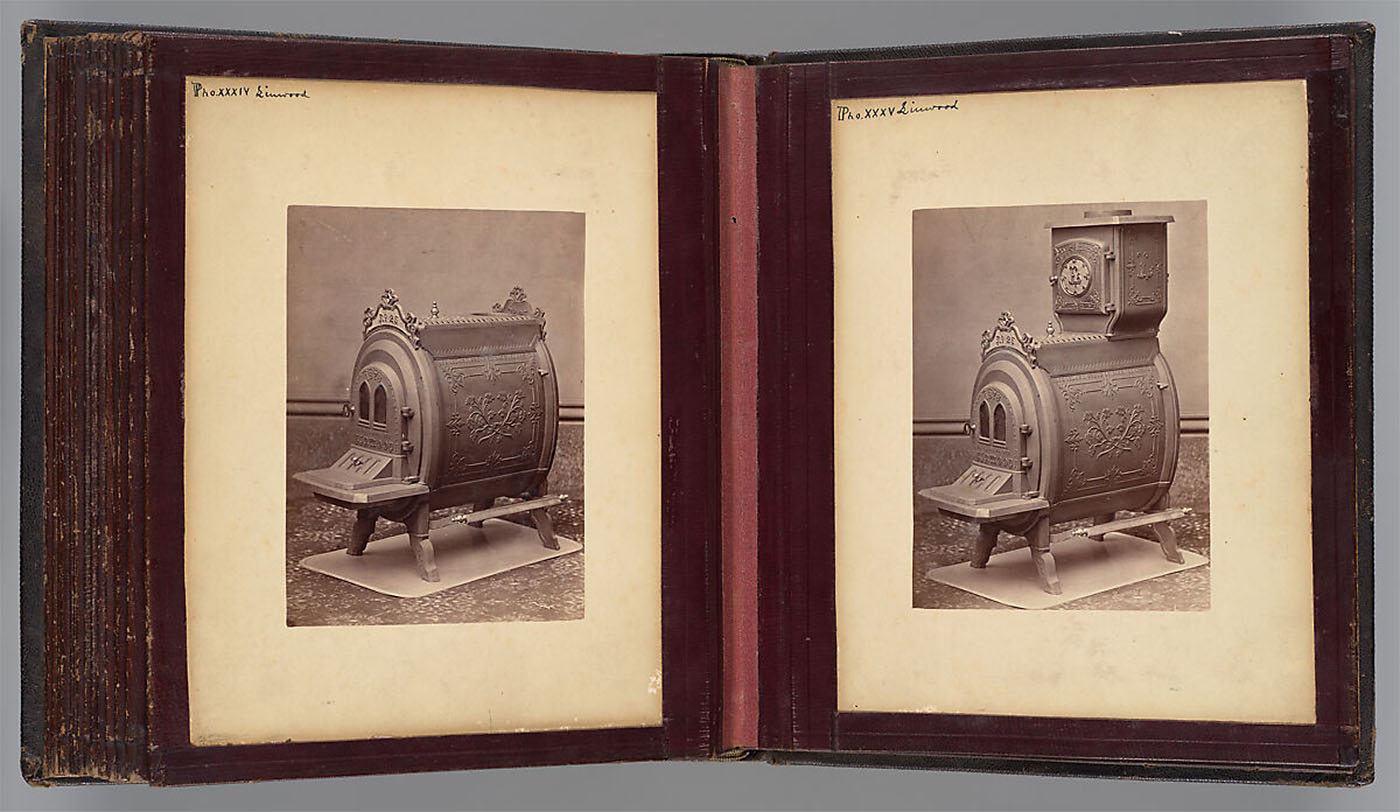

Unknown maker (American)

Rock Island Stove Company Catalogue

1878-1883

Albumen silver prints

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Joyce F. Menschel Photography Library Fund, 2003

Public domain

Unknown maker (British)

Fashions 1837-1887 by William Charles Brown (British, active late 19th century)

1888

Woodburytypes

22.5 x 17cm (8 7/8 x 6 11/16 in.)

Approx. 9 x 14 in. open

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Joyce F. Menschel Photography Library Fund, 2011

In the back of this catalogue from Queen Victoria’s milliner, a disclaimer confirms that no British songbirds were sacrificed for its production. Nevertheless, a flock of hats in fine feather fills this page spread, flaunting designs fit for the royal family. The deluxe volume is illustrated with woodburytypes, an early photomechanical process with a rich tonal range to register varied velvets, silks, straws, and plumes. Hatstands and supports have been edited out of these images to suspend the specimens midair. Surreal to modern eyes, the effect accentuates the hats’ commodity status and implies inventory soaring out of stock.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Frank M. Sutcliffe (British, 1853-1941)

[Display of Whitby Seascape Photographs]

c. 1888

Albumen silver print

Image: 4 1/4 × 5 1/2 in. (10.8 × 14 cm)

Sheet: 6 15/16 × 9 1/2 in. (17.7 × 24.1 cm)

Frame: 11 x 14 in.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 2023

Public domain

“Choose one subject, anything will do,” Frank Sutcliffe advised aspiring photographers. If his career-spanning preoccupation with the British seaside town of Whitby seemed myopic to some peers, it allowed him to cultivate a distinctive brand. This typology of seascapes testifies to his years of work along the town harbour, where he weathered storms and punishing wind in pursuit of the perfect view. Pinned up for purchase at an exhibition, his photographs here become products. This rudimentary style of display seems to have served him well; at one such showcase, he counted the Prince of Wales among his customers.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Unknown (American)

[Vermont Marble Tombstone Catalogue]

1880s

Albumen silver prints

Approx. 17 1/4 x 4 in. open

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Jefferson R. Burdick Bequest, 1972

Public domain

“When you are met with a flood of tears, the best thing to do is politely say that you will call again,” advised one traveling salesman in the tombstone trade. For Cyrus Creigh, a thirty-something Virginian who sold stones from this annotated catalogue, such considerations were part of the job. In each new town, he might solicit names of bereaved families from undertakers and local cemetery staff. Slipped from a suit pocket and proffered door-to-door, his book of bluntly descriptive photographs sold surviving relatives a modicum of consolation. The stones, posed in a corporate studio and silhouetted in darkness, assume a solemn universality, as if any of their blank faces might soon bear a familiar name.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Schadde Brothers (American, active Minneapolis, 1890s-1910s)

Alvin J. Schadde (American, 1872-1937)

Herman T. Schadde (American, 1874-1937)

[High Grade Jelly Eggs, from a Brandle & Smith Co. Catalogue]

c. 1915

Gelatin silver print with applied colour

Image: 8 1/4 × 9 3/4 in. (21 × 24.8cm)

Frame: 18 x 20 in.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2013

Schadde Brothers (American, active Minneapolis, 1890s-1910s)

Alvin J. Schadde (American, 1872-1937)

Herman T. Schadde (American, 1874-1937)

[Satinettes, Filled Confections and Ye Old Style Stick Candy, from a Brandle & Smith Co. Catalogue]

c. 1915

Gelatin silver print with applied colour

Image: 8 1/2 × 10 5/8 in. (21.6 × 27cm)

Frame: 18 x 20 in.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2013

This trade catalogue tricks the eye to tempt the tongue. An artisan has coloured its black-and-white prints, illustrating each sugar stripe and speckled bean. Philadelphia confectioner Brandle & Smith understood that their candy was its own best advertisement, and at one point even induced a museum to accession it for display. Wider distribution was achieved by the salesmen who carried catalogues across the country, taking bulk orders from local shops. Here, the limitations of hand-colouring work to their advantage. Because sweets in jars proved too tricky to tint, the satinettes and candy sticks seem to burst into brilliant colour as they spill from their packaging, satiating the viewer and assisting the sale.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

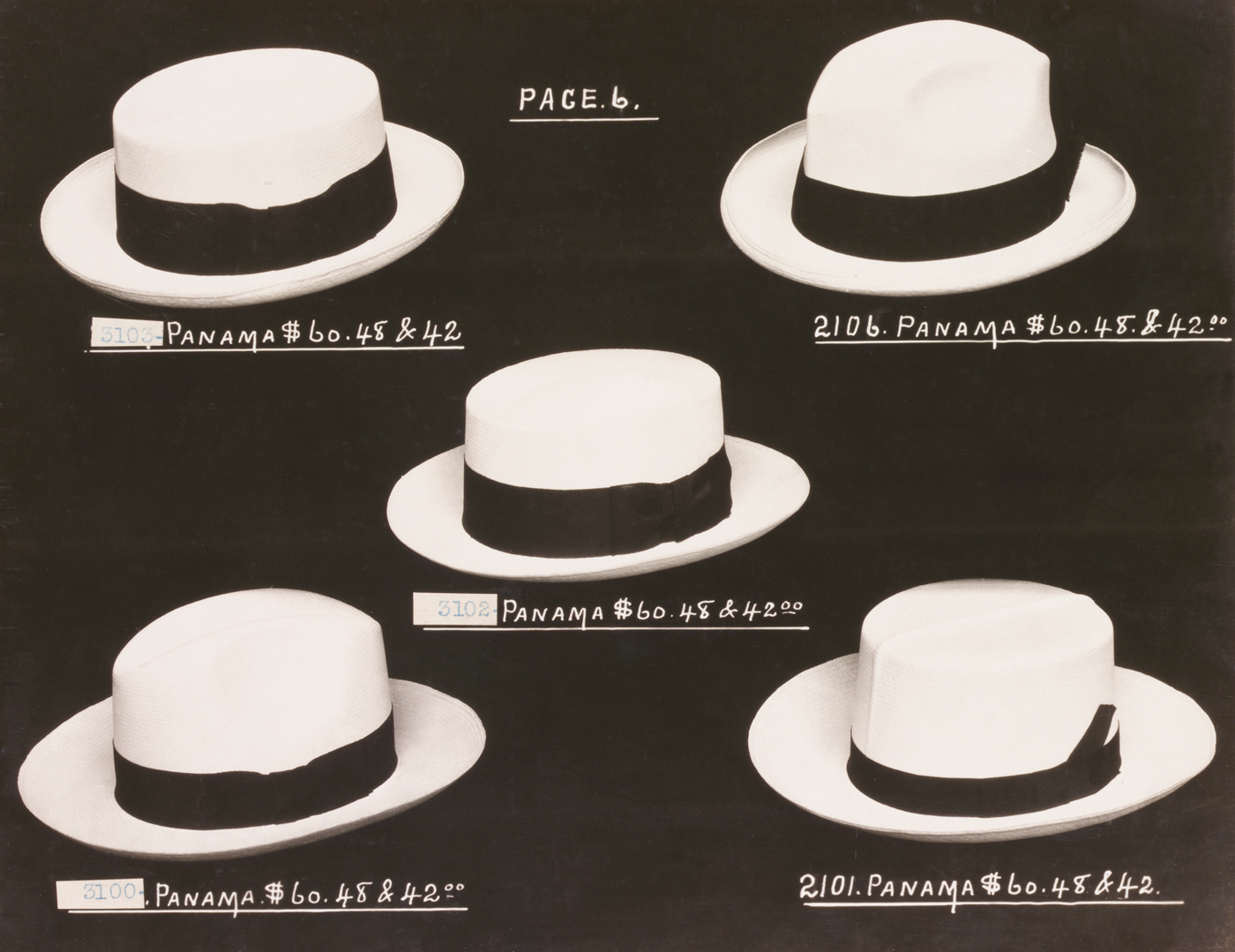

F. D. Hampson (American, 1871-1947)

Panama Hats, from a Sloan-Force Co. Catalogue

c. 1916

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18.5 x 23.4 cm (7 5/16 x 9 3/16 in. )

Frame: 16 x 20 in.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2001

Like satellites, these straw hats hover in a void. Their absence of context invites imaginative projection: how easy to envision this or that model touching down on one’s head. Popularised by association with the new Panama Canal, the hats were photographed for a St. Louis sales catalogue. Their spare, surreal configuration anticipates an avant-garde approach; in the coming years, disembodied hats would pop up in works by Max Ernst and Hans Richter, evoking the callous consumer – a bourgeois icon ripe for critique. Here, such premonitions of modernism serve practical ends. Suspended together, their varied brims and bands elicit comparison, demanding scrutiny. In an era of exponentially increasing consumer choice, such photographic displays could make anyone into a connoisseur.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Ralph Bartholomew Jr. (American, 1907-1985)

[Soap Packaging]

1936

Carbro print

32.8 x 25.7cm (12 15/16 x 10 1/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© Estate of Ralph Bartholomew, Courtesy Keith de Lellis Gallery, NY

If mouthwatering soap seems a contradiction in terms, commercial photographer Ralph Bartholomew Jr. confounds the senses with eye candy to rival the confections nearby. Photographed two decades later, this work did not depend on paint for its delectable palette. It is an example of the early carbro process – a complex tricolor printing technique that gained popularity in the 1930s, as art directors courted Depression-era audiences. Brilliant colour is essential here, in a photograph likely commissioned to sell not the soap but its packaging. Marketed to producers in an array of trade publications (including Modern Packaging, and the industry-specific standby Soap), fine paper wrappers were a booming industry unto themselves. Here, Bartholomew parades his bedecked bars across a page of newsprint showing stock prices to suggest that in this market, even cleanliness was a commodity.

Bartholomew was a successful commercial photographer best known for his innovative use of stop-action and multiple exposure techniques in advertising and editorial work. He made this photograph while he was a student at the Clarence H. White School of Photography.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

The Array

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

RCA Speakers

1933

Gelatin silver print

Image: 33.3 x 23.3 cm (13 1/8 x 9 3/16 in.)

Frame: 22 1/2 x 18 1/2 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Warner Communications Inc. Purchase Fund, 1976

In a single voice, the assembled speakers broadcast the scope and influence of American radio. Commissioned by audio manufacturer RCA Victor, this photograph is one component of a monumental photomural for the NBC rotunda at Rockefeller Center. Amplified to a height of ten feet, this and other views of radio technology comprised a work of corporate propaganda to rival those public projects Margaret Bourke-White had recently seen on tours of the Soviet Union. She completed the mural at breakneck speed, often working through the night to photograph equipment at regional stations (lest she risk electrocution during daytime transmission hours). Seeking a visual analogue to audio, she captured the speakers in staccato sequence, their scalloped shapes reverberating beyond the frame.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

On March 11, 2024, The Metropolitan Museum of Art opened The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography, an exhibition exploring how commercial camerawork contributed to the visual language of modernism. The photographs featured depict the familiar trappings of everyday life – from toothpaste to tombstones to hats – but at times these subjects will be unrecognisable, so altered by the camera as to constitute an entirely new view.

Spanning the first century of photographic advertising, The Real Thing unites more than 60 works from across the commercial sector. In these photographs, artists – some famous, some forgotten – transform common objects into covetable commodities. Corporate commissions by celebrated innovators, such as Paul Outerbridge, August Sander, and Piet Zwart, appear alongside obscure catalogues and trade publications. Bringing these photographs together, the exhibition reveals links between the promotional strategies of vernacular studios and the radical tactics of the interwar avant-garde.

“This dynamic exhibition looks anew at the commercial history of photographs in the Museum’s collection,” said Max Hollein, The Met’s Marina Kellen French Director and Chief Executive Officer. “By embracing this discerning lens, we gain a renewed appreciation of the intricacies and aesthetics of our everyday surroundings.”

“Not many of the photographers in this exhibition would have identified as fine artists, but their inventive commercial work harnesses the artistic potential of the camera to persuade and enchant,” added the show’s curator, Virginia McBride, Research Associate in the Department of Photographs. “Now that photography’s place in museums no longer needs defending, The Real Thing considers how working photographers, in corporate studios and industrial storerooms, advanced modern art’s visual revolution.”

The first advertising photographs were published in albums and used to peddle products door to door. For early retailers and ad agencies, photography offered unprecedented realism and, better still, an aura of truth; the medium’s perceived objectivity bolstered consumer confidence. Beginning in the late 1850s, new demand for manufactured goods subsidised commercial photography, spurred by evolving technologies of image reproduction. In the decades that followed, increasingly inventive approaches to the still life, from dizzying perspectives to extreme modulations of scale, adapted modernism for the mass market. Historically framed as avant-garde experimentation, this work is rarely acknowledged in its original context of commercial enterprise. This exhibition resituates such innovation within the realm of advertising and investigate its unlikely origins.

Drawn entirely from The Met collection and featuring many photographs from The Ford Motor Company Collection of modernist European and American photography, the exhibition brings together a wide range of photographic media. Included are proof prints, tear sheets, and sample books used by travelling merchants, along with photomontages and rare examples of early colour printing. Such masterworks as André Kertész’s elegant study of a fork and Grete Stern and Ellen Auerbach’s surrealist-inflected advertisements for hair dye and gloves are presented together with the projects of overlooked studios and anonymous makers. Debuting dozens of objects from the Department of Photographs that have never before been shown, and introducing timely new acquisitions, the exhibition considers photography in an expanded field of commercial practice.

The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography is organised by Virgina McBride, Research Associate in the Department of Photographs at The Met.

Press release from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Grit Kallin-Fischer (German, 1897-1973)

KPM Ceramics

1930

Gelatin silver print

6 5/8 × 4 3/16 in. (16.8 × 10.7cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Funds from various donors, 2023

The Isolated Object

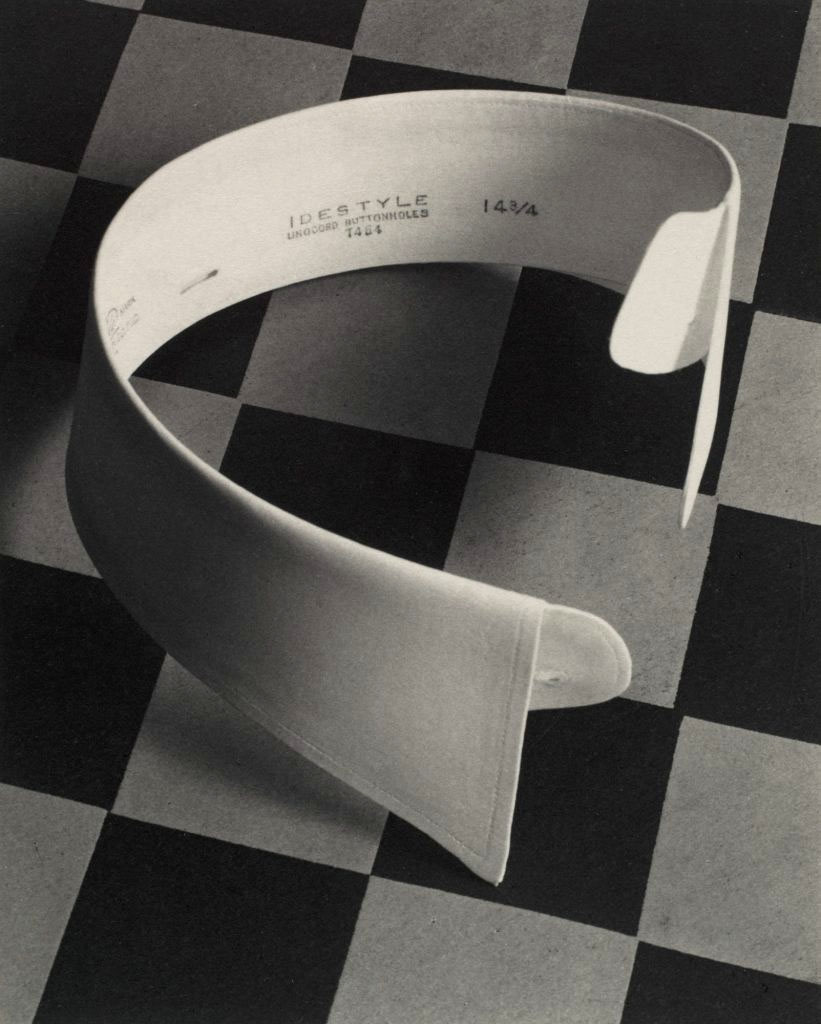

Paul Outerbridge Jr. (American, 1896-1959)

Ide Collar

1922

Platinum print

Image: 11.8 x 9.3 cm (4 5/8 x 3 11/16 in.)

Frame: approx. 14 x 17 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

“I have attempted to interpret the beauty of the simplest and humblest of objects,” Paul Outerbridge Jr. wrote in 1922. Inspired by his teacher Clarence H. White’s artistic vision for applied photography, Outerbridge regarded the aperture as a kind of canvas in which to arrange compositions with absolute balance. In this, his first commercial assignment, he achieved such equilibrium by custom-cutting a grid of linoleum squares to the scale of his subject. When published as an ad in Vanity Fair, the photograph was ensnared in a scrollwork frame. Such a Victorian flourish seems incongruous today, but at the time, a picture as stark as this seemed to need dressing up. Nevertheless, Marcel Duchamp was said to have clipped the ad and pinned it to his studio wall, apprehending the mass-market collar’s readymade style.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Co. (American)

Automotive Component

February 22, 1927

Gelatin silver print

7 1/2 × 9 1/2 in. (19 × 24.1 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, David Hunter McAlpin Fund, by exchange, 2024

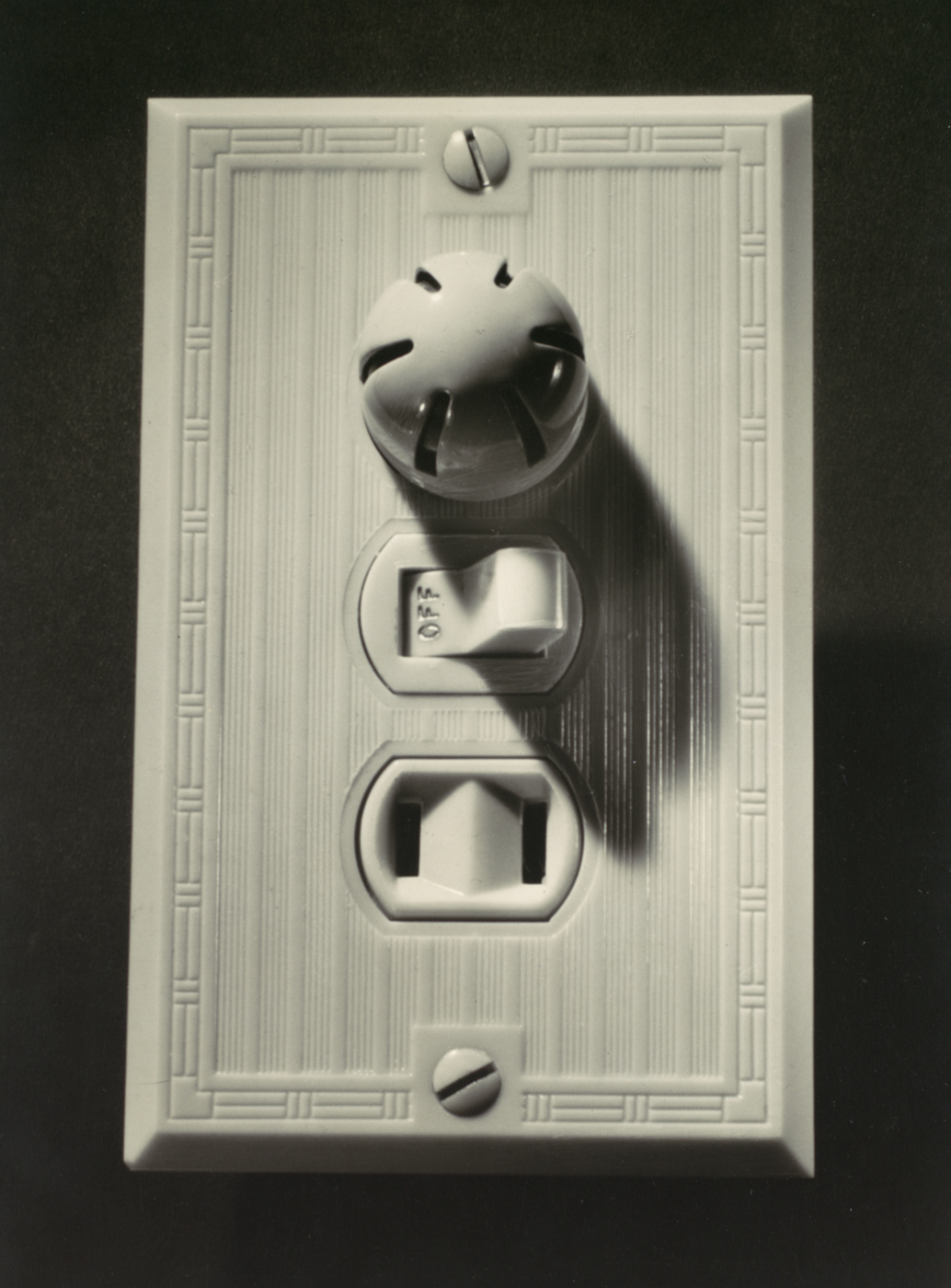

Fay Sturtevant Lincoln (American, 1894-1975)

Pass & Seymour Switch Plate

c. 1949

Gelatin silver print

Image: 23.8 x 17.9 cm (9 3/8 x 7 1/16 in.)

Frame: approx. 20 x 16 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

Please resist the urge to flip this light switch. Photographed at close range, the switch plate is so crisply articulated that it tempts touch. Fay Sturtevant Lincoln captures the sculptural quality of this mundane fixture, revealing a keen eye for the texture and detail of domestic life. Now coveted for their retro cachet, molded Bakelite furnishings like this one were ubiquitous in the late 1940s. Though Lincoln was better known for views of glamorous art deco interiors, his attention to the vernacular architecture of homes and offices offers an intimate view of everyday design.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Murray Duitz (American, 1917-2010)

A.S. Beck “Executive” Shoe

1957

Gelatin silver print

Image: 12 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (31.8 x 22.9cm)

Frame: 20 x 16 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gift of the artist, 1975

© Estate of Murray Duitz

The Unfamiliar Thing

Installation view of the exhibition ‘The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York showing the section The Unfamiliar Thing including at third left, August Sander’s Osram Light Bulbs (c. 1930, below); and at third right, H. Raymond Ball’s Pocket Comb (1930s, below)

Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 – 1973 West Redding, Connecticut)

[“Sugar Lumps” Pattern Design for Stehli Silks]

1927

Gelatin silver print

25.3 x 20.3cm (9 15/16 x 8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

For a project promoting not sugar but silk, Edward Steichen devised textile patterns from photographs of everyday objects. His arrangements of sugar cubes, matches, and mothballs were printed onto Stehli’s “Americana” line of dress fabrics. The success of these designs speaks to the proliferation and popularity of object photography – a genre so culturally ingrained that, by the late 1920s, it could become a fashion phenomenon. Steichen helped shape these conditions in his influential role as chief photographer for Condé Nast. The Stehli project reflected his populist vision for commercial photography, at least insofar as these chic silks ever reached the mainstream.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

[Osram Light Bulbs]

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Image: 29.5 x 22.9 cm (11 5/8 x 9 in.)

Frame: 22 1/2 x 18 1/2 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography itself makes the case for artificial light in this commission for the German manufacturer Osram. Leveraging the camera’s codependence on their products, the lightbulb company sought out experimental practitioners, including August Sander, to promote the transformative potential of illumination. Sander is best known as the great portraitist of German society between the wars, but the commercial projects that supported his studio remain obscure. With a simple shift in perspective, he radically reorients viewer and subject, abstracting a spiral staircase into a swirl of pearls. His hypnotic image reveals how the shock and pleasure of modernist aesthetics – of looking for its own sake – could seamlessly convey the joys of consumption.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

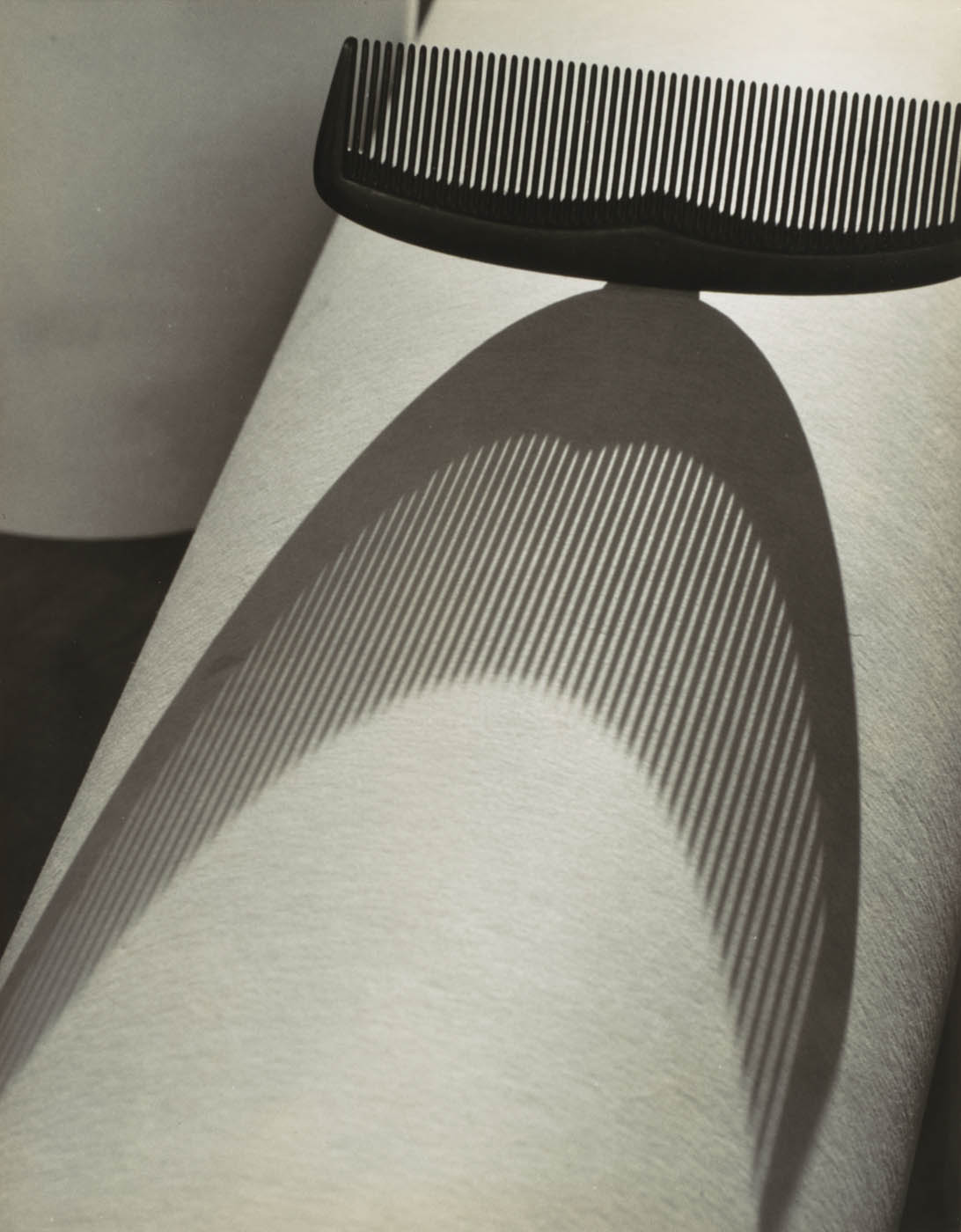

H. Raymond Ball (American, 1903-1983)

Pocket Comb

1930s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 25.2 x 19.8 cm (9 15/16 x 7 13/16 in.)

Frame: 20 x 16 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

The Montage

César Domela (Dutch, 1900-1992)

[Ruthsspiecher Tanks]

1928

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19.3 x 16.6 cm (7 5/8 x 6 9/16 in.)

Frame: 17 x 14 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Unknown (American)

[Montage for Packard Super Eight]

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

Image: 22.9 x 18.6 cm (9 x 7 5/16 in.)

Frame: 17 x 14 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

The Tableau

Installation view of the exhibition The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York showing photographs from the section The Tableau including at left, André Kertész’s Fork (1928, below); and at second and third right, ringl + pit’s Dents (c. 1934) and Komol (1931, below)

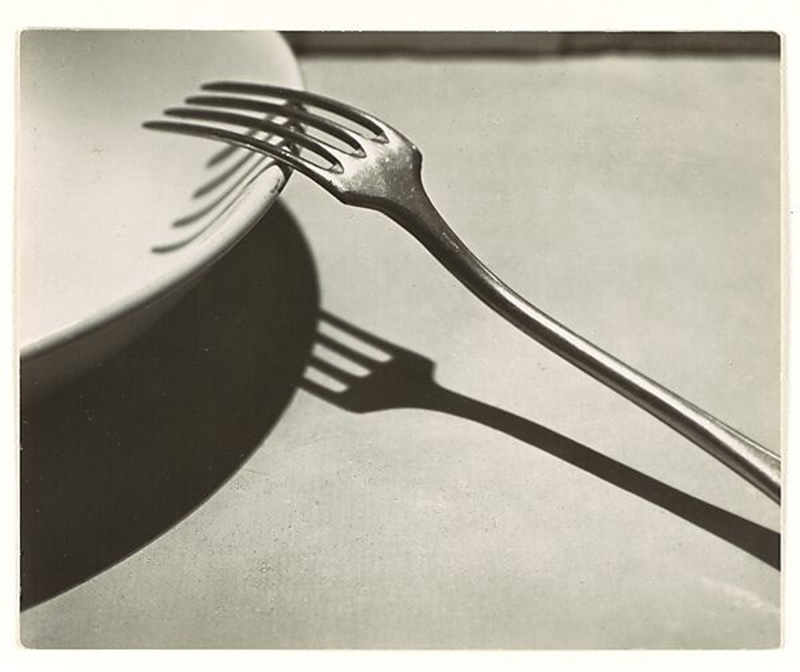

André Kertész (American born Hungary, 1894-1985)

Fork

1928

Gelatin silver print

7.5 x 9.2cm (2 15/16 x 3 5/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© The Estate of André Kertész / Higher Pictures

As a dinner party wound down in his friend Fernand Léger’s Paris studio, André Kertész found an unlikely tableau left on the table. In this chance encounter between fork and plate, he locates an incidental elegance. The photograph was never intended as an ad – Kertész instead chose it to represent his work in a series of European photography shows. On the exhibition circuit, it came to exemplify a strain of New Vision photography characterised by its clear-eyed reassessment of ordinary things. Only after this did Kertész grant permission for its use in a German silverware campaign. In the ad layout, the photograph was credited and uncropped – atypically presented as a true work of art. The truth of the ad was another question: despite its German rebranding, this fork remained a French department-store product.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

ringl + pit (German active 1930-1933)

Grete Stern (German, 1904-1999)

Ellen Auerbach (German 1906-2004)

Komol

1931

Gelatin silver print

Image: 35.9 x 24.4 cm (14 1/8 x 9 5/8 in.)

Frame: 20 x 15 5/8

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© ringl+pit, Courtesy Robert Mann Gallery

Grancel Fitz (American, 1894-1963)

Ipana Toothpaste

c. 1937

Gelatin silver print

Image: 12.9 x 32.5cm (5 1/16 x 12 13/16 in.)

Frame: approx. 12 x 20 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

The Ideal User

Paul Outerbridge Jr. (American, 1896-1959)

The Coffee Drinkers

1940

Carbro print

Image (overall): 27 x 38 cm (10 5/8 x 14 15/16 in.)

Mount: 40.7 x 50.7cm (16 x 19 15/16in.)

Frame: 18 1/2 x 22 1/2 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

With a background in staging and an unwavering belief in the power of images to inspire a better life, Paul Outerbridge Jr. was well suited to the directorial tasks of advertising photography. For A&P Grocery’s Eight O’Clock Coffee, he orchestrated this scene in the display kitchen of a department store, painstakingly diagramming the setup in advance.

“How’d you learn to make such swell coffee, Dick?” the copy teased, when the ad ran in LIFE magazine. Such work exceeds the sum of its parts, selling more than just a jolt of caffeine. The after-dinner air of repose courts camp, conjuring an intimate blend of leisure and power. With it, Outerbridge offers the consumer the chance to be a man among men, all for the price of a can of coffee.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Some expressive quotations about the construction of the self, commodities and consumer culture

“Although the value of commodities is materially embodied in them, it is not visible in the objects themselves as a physical property. The illusion that value resides in objects rather than in the social relations between individuals and objects Marx calls commodity fetishism. When the commodity is fetishized, the labour that has gone into its production is rendered invisible.”

Rosemary Hennessey. “Queer Visibility in Commodity Culture,” Chapter 6 in Nicholson, Linda and Seidman, Steven (eds.,). Social Postmodernism – Beyond Identity Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 161-162.

“When the commodity is dealt with merely as a matter of signification, meaning, or identities, only one of the elements of its production – the process of image making it relies on – is made visible. The exploitation of human labour on which the commodities appearance as an object depends remains out of sight.”

Rosemary Hennessey. “Queer Visibility in Commodity Culture,” Chapter 6 in Nicholson, Linda and Seidman, Steven (eds.,). Social Postmodernism – Beyond Identity Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 162.

“The processes of capitalist relationships reproduce themselves in the consciousness of man and, in turn, reproduce a society that reflects an image of man as the seller and buyer of work, talent, aspiration and fantasies.”

Frankl, G. The Failure of the Sexual Revolution. Hove: Kahn and Averill, 1974, p. 26 quoted in Evans, David. Sexual Citizenship, The Material Construction of Sexualities. London: Routledge, 1993, p. 47.

“What was achieved was unprecedented scientific and technical progress and, eventually, the subordination of all other values to those of a world market which treats everything, including people and their labour and their lives and their deaths, as a commodity.”

John Berger and Jean Mohr. Another Way of Telling. New York: Pantheon Books, 1982, p. 99.

“Consumption produces production … because a product becomes a real product only by being consumed. For example, a garment becomes a real garment only in the act of being worn; a house were no one lives is in fact not a real house; thus the product, unlike a mere natural object, proves itself to be, becomes, a product only through consumption. Only by decomposing the product does consumption give the product the finishing touch.”

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. On Literature and Art. New York: International General, 1973, p. 91 quoted in Wolff, Janet. The Social Production of Art. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1993, p. 95.

“… the propaganda of consumption turns alienation itself into a commodity. It addresses itself to the spiritual desolation of modern life and proposes consumption as the cure. It not only promises to palliate all the old unhappiness to which flesh is heir; it creates or exacerbates new forms of unhappiness – personal insecurity, status anxiety …”

Christopher Lasch. The Culture of Narcissism. New York: W.W.Norton and Company, 1978, p.73.

“Consumer culture is notoriously awash with signs, images, publicity. Most obviously, it involves an aestheticization of commodities and their environment …

Firstly, problems of status and identity … promote a new flexibility in the relations between consumption, communication and meaning. It is not so much that goods and acts of consumption become more important in signalling status (they were always crucial) but that both the structure of status and the structure of meaning become unstable, flexible, and highly negotiable. Appearance becomes a privileged site of strategic action in unprecedented ways.

Secondly, the nature of market exchange seems intrinsically bound up with aestheticization. As indicated above, commodities circulate through impersonal and anonymous networks: the split between producer and consumer extends beyond simple commissioning (where a personal relationship still exists) to the production for an anonymous general public … Haug (1986) theorizes this in the notion of ‘commodity aesthetics’: the producer must create an image of use value in which potential buyers can recognize themselves. All aspects of the product’s meaning and all channels through which its meaning can be constructed and represented become subject to intense and radical calculation.

This gives rise to some of the central issues of sociological debate on consumer culture. On the one hand, the eminently modern notion of the social subject as a self-creating, self-defining individual is bound up with self-creation through consumption: it is partly through the use of goods and services that we formulate ourselves as social identities and display these identities. This renders consumption as the privileged site of autonomy, meaning, subjectivity, privacy and freedom. On the other hand, all these meanings around social identity and consumption become objects of strategic action by dominating institutions. The sense of autonomy and identity in consumption is placed constantly under threat.”

Don Slater. Consumer Culture and Modernity. London: Polity Press, 1997, p. 31.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Thursday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Closed Wednesday

![Charles Nègre (French, 1820-1880) '[Plaster Casts of Bishops' Miters, South Porch, Chartres]' c. 1855 Charles Nègre (French, 1820-1880) '[Plaster Casts of Bishops' Miters, South Porch, Chartres]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/negre-plaster-casts.jpg)

![Pine & Bell (photographic studio) (American, active 1860s, Troy, New York) William H. Bell (American born England, Liverpool 1831-1910 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) George W. Pine (American, active 1860s, Troy, New York) '[Display of Hats and Accessories of 1868]' 1868 Pine & Bell (photographic studio) (American, active 1860s, Troy, New York) William H. Bell (American born England, Liverpool 1831-1910 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) George W. Pine (American, active 1860s, Troy, New York) '[Display of Hats and Accessories of 1868]' 1868](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/pine-bell-display-of-hats-and-accessories-of-1868.jpg)

![Unknown photographer. '[E. Adkins Gun Merchant]' c. 1874 Unknown photographer. '[E. Adkins Gun Merchant]' c. 1874](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/unknown-photographer-e.-adkins-gun-merchant.jpg)

![Frank M. Sutcliffe (British, 1853-1941) '[Display of Whitby Seascape Photographs]' c. 1888 Frank M. Sutcliffe (British, 1853-1941) '[Display of Whitby Seascape Photographs]' c. 1888](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/sutcliffe-display-of-whitby-seascape-photographs.jpg)

![Unknown (American) '[Vermont Marble Tombstone Catalogue]' 1880s Unknown (American) '[Vermont Marble Tombstone Catalogue]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/unknown-vermont-marble-tombstone-catalogue.jpg)

![Schadde Brothers (American, active Minneapolis, 1890s-1910s) Alvin J. Schadde (American, 1872-1937) Herman T. Schadde (American, 1874-1937) '[High Grade Jelly Eggs, from a Brandle & Smith Co. Catalogue]' c. 1915 Schadde Brothers (American, active Minneapolis, 1890s-1910s) Alvin J. Schadde (American, 1872-1937) Herman T. Schadde (American, 1874-1937) '[High Grade Jelly Eggs, from a Brandle & Smith Co. Catalogue]' c. 1915](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/schadde-brothers-high-grade-jelly-eggs.jpg)

![Schadde Brothers (American, active Minneapolis, 1890s-1910s) Alvin J. Schadde (American, 1872-1937) Herman T. Schadde (American, 1874-1937) '[Satinettes, Filled Confections and Ye Old Style Stick Candy, from a Brandle & Smith Co. Catalogue]' c. 1915 Schadde Brothers (American, active Minneapolis, 1890s-1910s) Alvin J. Schadde (American, 1872-1937) Herman T. Schadde (American, 1874-1937) '[Satinettes, Filled Confections and Ye Old Style Stick Candy, from a Brandle & Smith Co. Catalogue]' c. 1915](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/schadde-brothers-satinettes.jpg)

![Ralph Bartholomew Jr. (American, 1907-1985) '[Soap Packaging]' 1936 Ralph Bartholomew Jr. (American, 1907-1985) '[Soap Packaging]' 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/bartholomew_soap-packaging.jpg)

![Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 - 1973 West Redding, Connecticut) '["Sugar Lumps" Pattern Design for Stehli Silks]' 1927 Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 - 1973 West Redding, Connecticut) '["Sugar Lumps" Pattern Design for Stehli Silks]' 1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/steichen-sugar-lumps.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) '[Osram Light Bulbs]' c. 1930 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) '[Osram Light Bulbs]' c. 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/august-sander_osram-light-bulbs.jpg)

![César Domela (Dutch, 1900-1992) '[Ruthsspiecher Tanks]' 1928 César Domela (Dutch, 1900-1992) '[Ruthsspiecher Tanks]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/domela-ruthsspiecher-tanks.jpg)

![Unknown (American) '[Montage for Packard Super Eight]' c. 1940 Unknown (American) '[Montage for Packard Super Eight]' c. 1940](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/unknown_montage-for-a-packard-super-eight.jpg)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women14-web.jpg?w=748)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mullatin [Portrait of a Indigenous Brazilian woman wearing a cross]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mullatin [Portrait of a Indigenous Brazilian woman wearing a cross]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women1-web.jpg?w=698)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mestize [Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mestize [Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women2-web.jpg?w=717)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women15-web.jpg?w=614)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women12-web.jpg?w=661)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a maid holding an embroidered cloth]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a maid holding an embroidered cloth]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women13-web.jpg?w=690)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of wet nurse with infant]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of wet nurse with infant]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women11-web.jpg?w=677)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women3-web.jpg?w=717)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Hermann Kummler (compiler) (1863-1949) '[Kellnerinnen im Grand Hotel / Waitresses in Grand Hotel]' 1861-1862' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Hermann Kummler (compiler) (1863-1949) '[Kellnerinnen im Grand Hotel / Waitresses in Grand Hotel]' 1861-1862' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women6-web.jpg?w=725)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Lehrerin mit Schülerin im Bahia / Teacher with a schoolgirl in Bahia]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Lehrerin mit Schülerin im Bahia / Teacher with a schoolgirl in Bahia]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women4-web.jpg?w=688)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Native Brazilian lady-in-waiting and young child attend to a veiled aristocrat]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Native Brazilian lady-in-waiting and young child attend to a veiled aristocrat]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women5-web.jpg?w=785)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Negerin mit dem Knaben in schlechter Stimmung / Negress with a boy in a bad mood]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Negerin mit dem Knaben in schlechter Stimmung / Negress with a boy in a bad mood]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women10-web.jpg?w=694)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Brazilian woman servant and child]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Brazilian woman servant and child]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women18-web.jpg?w=666)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a young Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a young Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women17-web.jpg?w=560)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women8-web.jpg?w=565)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women19-web.jpg?w=642)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman with two children]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman with two children]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women16-web.jpg?w=733)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian mother and child]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian mother and child]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women9-web.jpg?w=525)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Mistress punishing a native child]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Mistress punishing a native child]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women7-web.jpg?w=792)

You must be logged in to post a comment.