Exhibition dates: 24th November, 2009 – 8th April, 2010

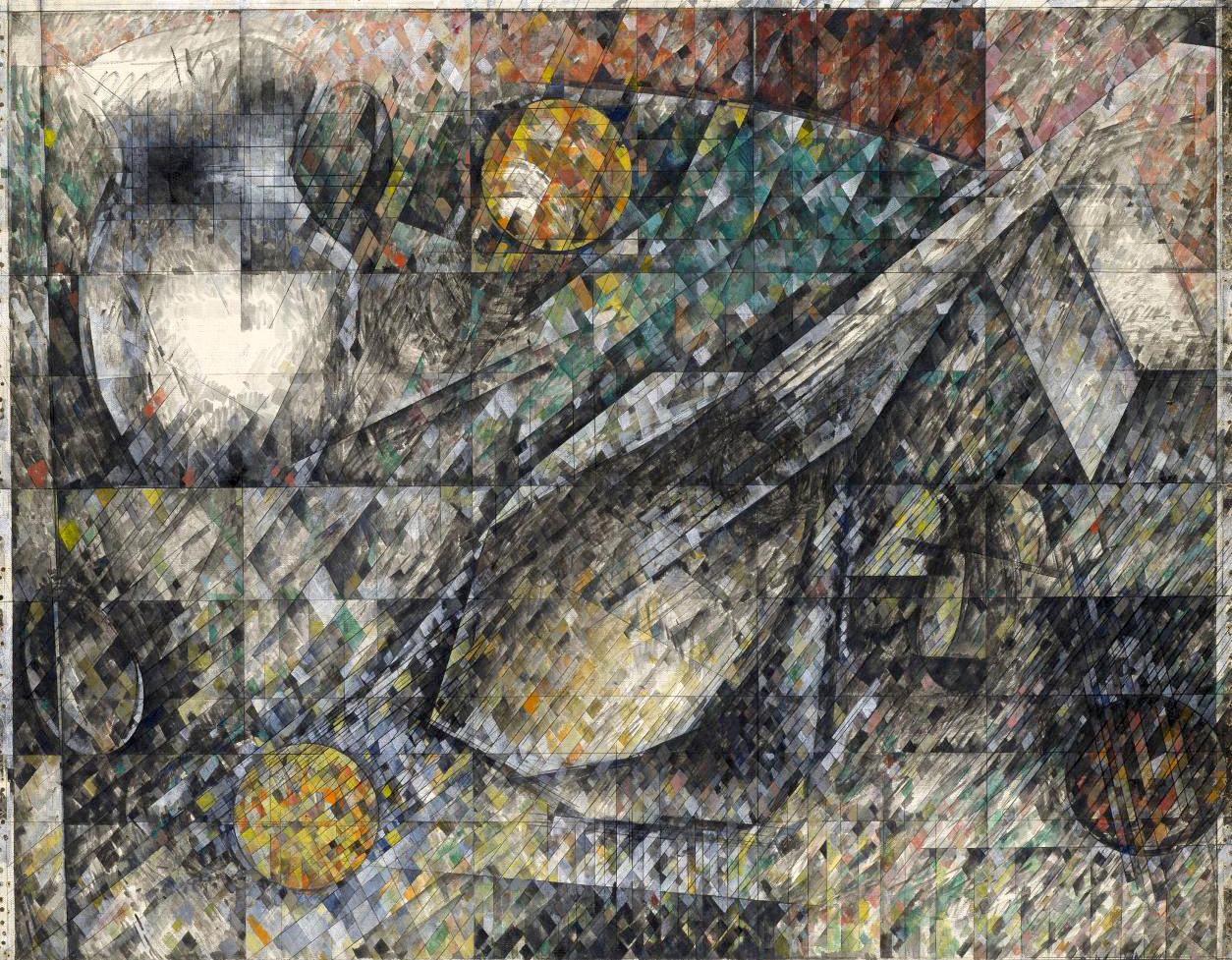

Jean Appleton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Painting IX

1937

Whitworth/Bruce Collection

Perfect summer fare out at Heide at the moment – relax with a lunch at the new Cafe Vue followed by some vibrantly fresh art in the galleries. In a nicely paced exhibition, Cubism & Australian Art takes you on a journey from the 1920s to the present day, the art revealing itself as you move through the galleries.

There are too many individual works to critique but some thoughts and ideas do stand out.

Cezanne’s use of passage (A French term (pronounced “pahsazh”) for a painting technique characterised by small, intersecting planes of patch-like brushwork that blend together to create an image), the transition between adjacent shapes, where solid forms are fused with the surrounding space was an important starting point for the beginnings of Cubism. Simultaneity – movement, space and the dynamism of modern life – was matched to Cubism’s new forms of pictorial organisation. The geometries of the Section d’Or (or the Gold Mean), that magical ratio found in all forms, also sounds an important note as it flows through the rhythmic movement and the sensations of temporal reality.

In the work from the 1920s/30s presented in the exhibition the palette of most of the works is subdued, the form of circles and geometrics. There are some beautiful paintings by one of my favourite Australian artists Roy de Maistre and others by Eric Wilson, Sam Atyeo and Jean Appleton (see image above). The feeling of these works is quiet and intense.

Following

There are some evocative works from the 1940s/50s including Godfrey Miller’s Still Life with Musical Instruments (1958, below), Graham King’s Industrial Landscape (1959) and Ralph Balson’s Constructive painting (1951). The Charcoal Burner (1959) by Fred Williams (see image below) is the Australian landscape seen through Cubist eyes, surface and space perfectly commingled in reserved palette, delineated planes. Grace Crowley’s Abstract Painting (1947, see image below) is a symphony of colour, plane and form that I would willingly take home any day of the week!

Now

It is the contemporary work that is of most interest in this exhibition. Spatio-temporal reality is distorted as artists push the boundaries of dimensionality. The parameters of reality are blurred and extended through the use of multiple viewpoints and lines of sight. Fresh and spatially aware (like an in joke because everyone recognises the fragmented ‘nature’ of contemporary existence) we have the sublime Milky Way (1995, see image below) by Rosalie Gascoigne and for me the two standout pieces in the exhibition, Bicycles (2007, below) by James Angus and Static No.9 (a small section of something larger) (2005, below) by Daniel Crooks.

Though difficult to see in the photograph of the work (below), Bicycles fuses three bicycles into one. “A photo finish made actual, a series of frames at the conclusion of a race transferred permanently into three dimensions.” You look and then look again: three frames into one, three tyres into one, three stands into one, three chains the only singular – like a freeze frame of a motor drive on a camera

Snap

Snap

Snap

or the slight difference of the two images of a Victorian stereoscope made triumvirate (the 3D world of Avatar comes to mind). Static, the bicycle can never work, is redundant, but paradoxically moves at the same time.

Even more mesmerising is the video work Static No.9 (a small section of something larger) by Daniel Crooks. Unfortunately I cannot show you the video but a still from the video can be seen below as well as a link to a trailer of the work. Imagine this animated like swirling DNA (in actual fact it is people walking across an intersection at different distances and speeds to the camera – and then sections taken out of the video and layered). Swirling striations through time and space fragment identity so that people almost become code, the sound track the distorted beep beep beep of the buzzer at the crossing. I could have sat there for hours watching the performance as it crackles with energy and flow – with my oohs and aahs! The effect is magical, beautiful, hypnotic.

A great summer show – fresh, alive and well worth the journey if only to see that static in all its forms has never looked so good.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Heide Museum of Modern Art for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

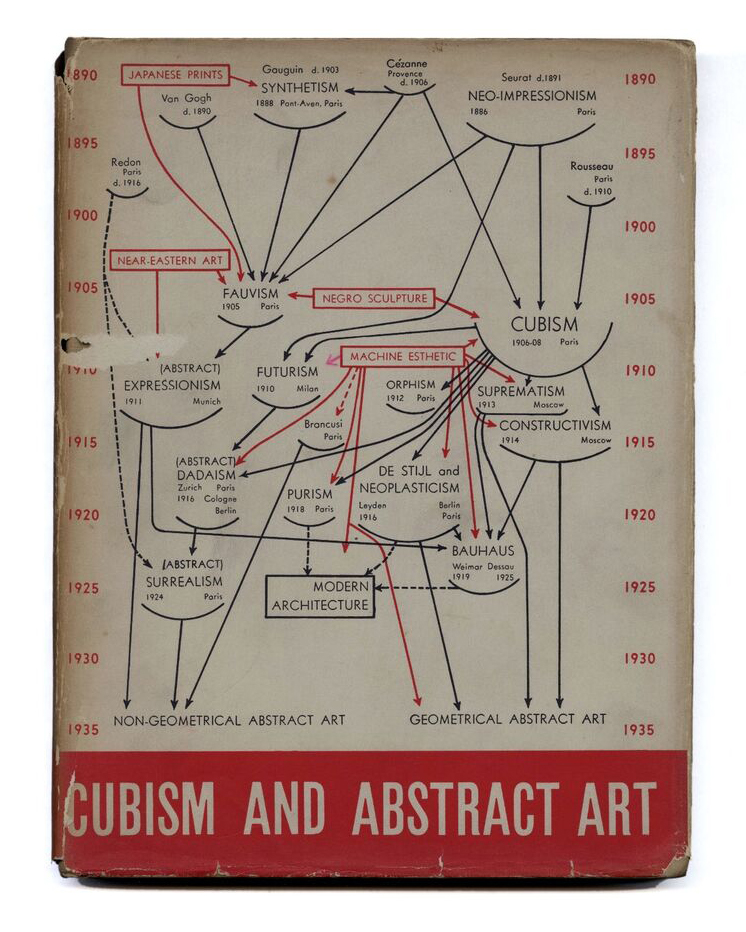

Alfred Barr’s Cubism diagram – original cover of Cubism and Abstract Art, Museum of Modern Art, New York, exhibition catalogue, 1936

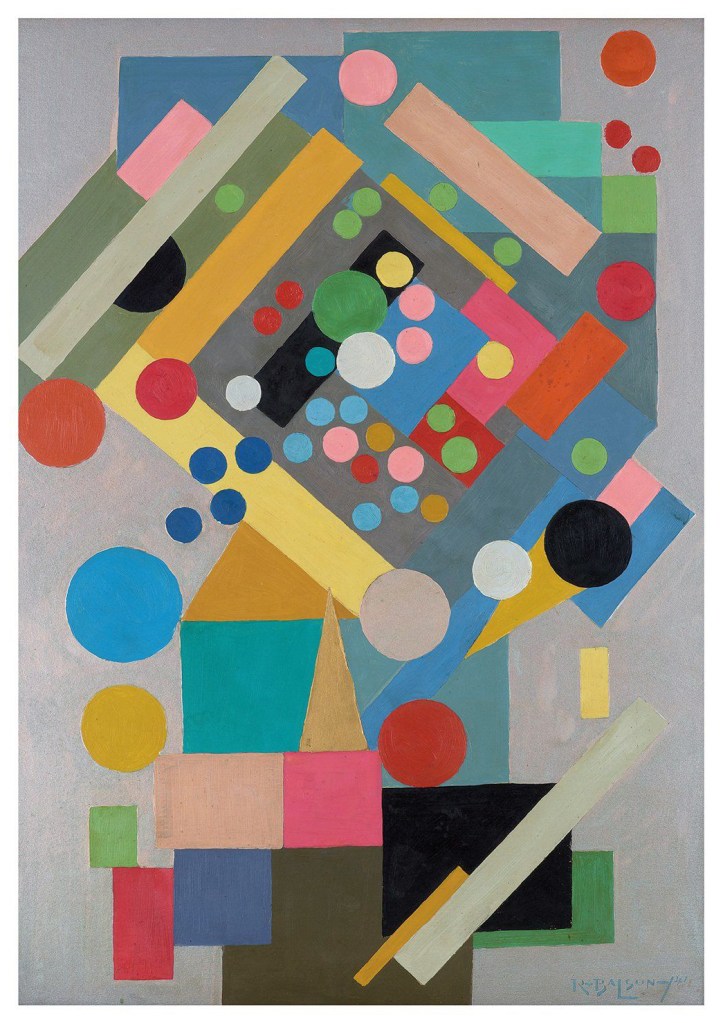

Ralph Balson (Australian, 1890-1964)

Painting no. 17

1941

Oil and metallic paint on cardboard

91.7 x 64.8cm

Hassall Collection

By 1941 Ralph Balson had abandoned the figure for a completely abstract style. He announced this breakthrough in a solo exhibition at the Fine Art Galleries at Anthony Hordern and Sons in Sydney with paintings that evolved in part out of Albert Gleizes’s style of Cubism: uninflected surfaces, essential forms, respect for the two-dimensionality of the picture surface and the sense of a search for a deeper, universal truth.

Though at the time unusual for Australian art, such developments were concurrent with advancements in abstraction in the UK and US. This new mode of painting was to preoccupy Balson and Crowley, and to a lesser extent Frank Hinder, for the rest of the decade.

Balson’s ‘constructive’ pictures became sophisticated and intricate, characterised by Constructive painting (1945), with its overlapping translucent planes and array of discs, squares and rectilinear shapes in an animated state of flux, and perhaps culminating in Constructive painting (1951). This work has a different kind of luminosity, as if the picture has an inner light. As Balson himself said of such images, they are ‘abstract from the surface, but more truly real with life’.

Heide Education Resource p. 15.

Dorrit Black (Australian, 1891-1951)

The bridge

1930

Oil on canvas on board

60 x 81cm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Bequest of Dorrit Black, 1951

Roy de Maistre (Australian, 1894-1968)

The football match

1938

Oil on canvas

71.5 x 92cm

The Janet Holmes à Court Collection

Eric Wilson (Australian, 1911-1946)

Theme for a mural

1941

Oil on plywood on corrugated iron

53.2 x 106.8cm

National Gallery of Victoria, purchased 1958

Sidney Nolan (Australian, 1917-1992)

Rimbaud royalty

1942

Synthetic polymer paint on composition board

59.5 x 90cm

Heide Museum of Modern Art

Bequest of John and Sunday Reed

Ralph Balson (Australian born England, 1890-1964; worked in Australia 1913-1964)

Constructive painting

1948

Oil on cardboard

106.8 × 71.0cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Bequest of Grace Crowley, 1981

© Ralph Balson Estate

Grahame King (Australian 1915-2008)

Industrial Landscape

1960

Oil on board

91.00 x 122.00cm

Charles Nodrum Gallery

Daniel Crooks (New Zealand, b. 1973)

Portrait #2 (Chris)

2007

Lambda photographic print

102 cm x 102cm

Heide Museum of Modern Art

Purchased with funds from the Robert Salzer Foundation 2012

“With these portraits I’m attempting to make large detailed images of people in their own surroundings, images of people very much in and of their time that are both intriguing and beautiful. As with a lot of my work the portraits also seek to render the experience of time in a more tangible material form, blurring the line between still and moving images and looking to new post-camera models of spatiotemporal representation.”

Daniel Crooks

Portrait #2 (Chris) forms part of Daniel Crooks’s Scanlines, a series of moving image works and prints made using digital collage techniques. This involves digitally slicing images then reassembling them sequentially, across the screen or picture plane, to create rhythmic and spatial effects through which Crooks seeks to explore ideas and themes related to our understandings of time and motion.

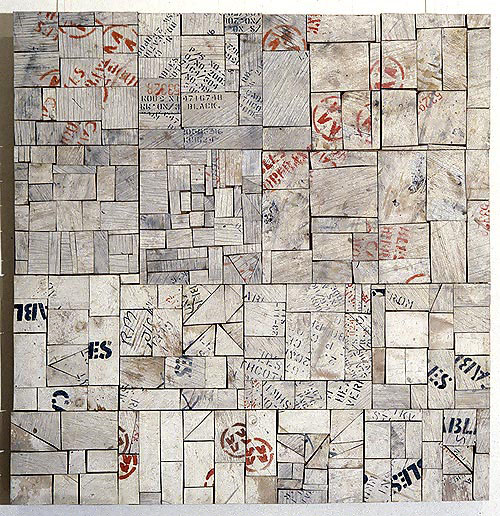

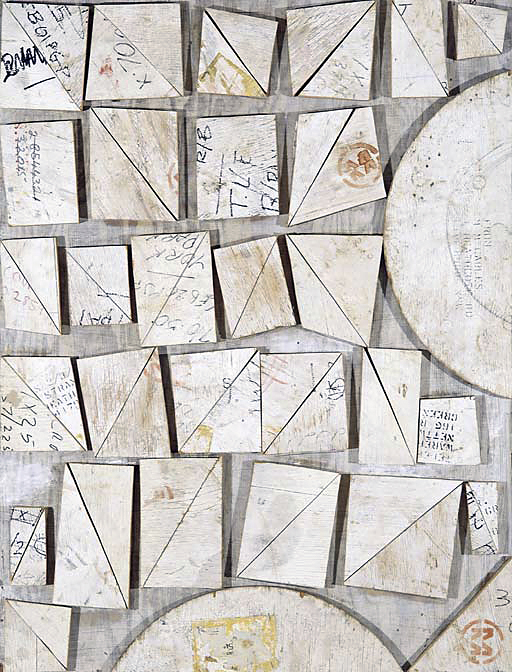

Elizabeth Gower (Australian, b. 1952)

City Series

1982-1984

Acrylic on paper

© Courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

Elizabeth Gower (Australian, b. 1952)

Transient

1979

Synthetic, polymer paint and resin on rice paper, newsprint and garment patterns

© Courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

Elizabeth Gower found a new relevance for Cubism in her abstract series Shaped works (1978-1984) … Cubist collage combined with feminist ideas to inspire her use of everyday materials such as newsprint and garment patterns. Transparent rice paper adds a delicacy and lightness to the work. The dynamic overlap of flat planes and juxtaposition of contrasting shapes, textures and patterns relates directly to the legacy of Synthetic Cubism. The work of Sonia Delaunay was also a particular inspiration for Gower.

Heide Education Resource p. 23.

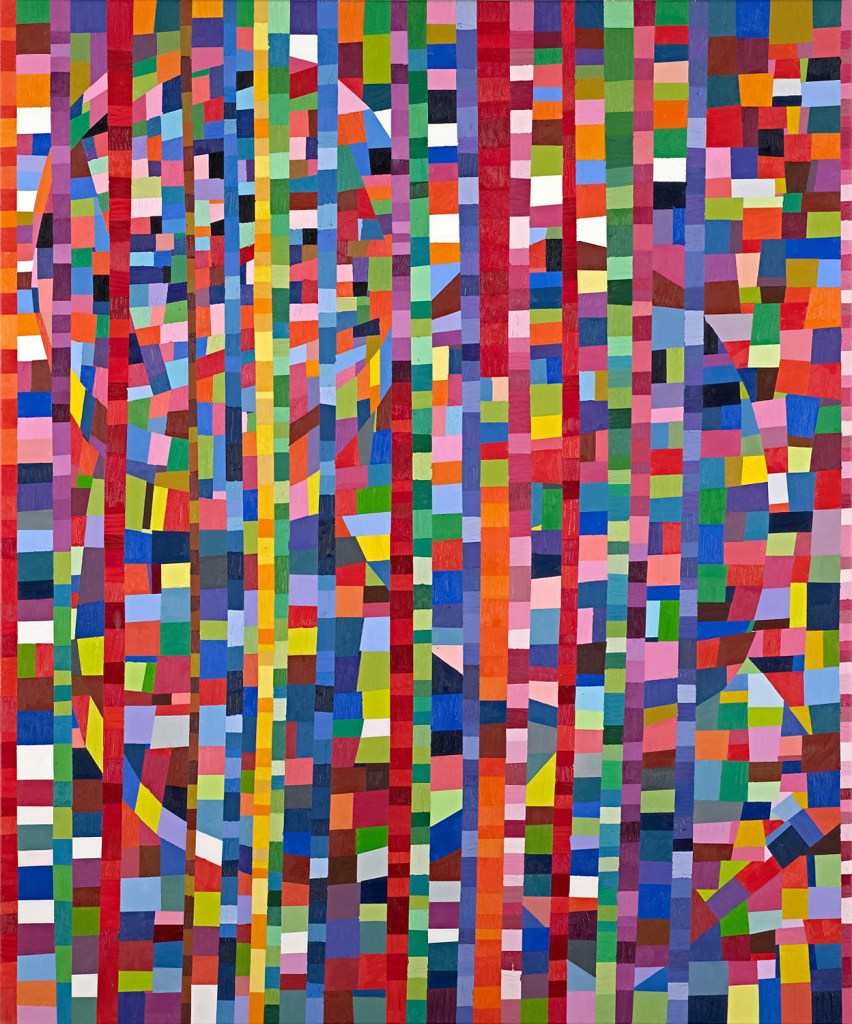

Melinda Harper (Australian, b. 1965)

Untitled

2000

Oil on canvas

183.0 × 152.3cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented through the NGV Foundation by Robert Gould, Founder Benefactor, 2004

© Melinda Harper/Licensed by Copyright Agency, Australia

Cubism & Australian Art, one of the most ambitious and extensive exhibitions Heide has undertaken, shows the impact of the revolutionary and transformative movement of Cubism on Australian art from the early twentieth century to the present day. It uncovers a little-known yet compelling history through works by over eighty artists, including key examples of international Cubism drawn from Australian collections – by André Lhote, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Alexander Archipenko, Ben Nicholson and others – and nine decades of Australian modern and contemporary art that demonstrate a local evolution of cubist ideas.

The exhibition documents the earliest incorporation of cubist principles in Australian art practice in the 1920s, when artists such as Grace Crowley and Anne Dangar, who studied overseas under leading cubist artists, began to transform their art in accordance with late cubist thinking. It examines the influence of Cubism on artists associated with the George Bell School in Melbourne and the Crowley-Fizelle School in Sydney; and on those who participated in the cubist movement abroad including James Cant and John Power.

While its distortions and unconventional perspectives served individual styles such as the expressionism of Albert Tucker or the experimental landscapes of Sidney Nolan and Fred Williams, Cubism’s most enduring influence on postwar Australian art has been in abstraction. This exhibition traces its reverberations in 1950s abstract art by Roger Kemp, Robert Klippel and Ron Robertson-Swann and others, through to works by younger artists such as Stephen Bram, Gemma Smith and Justin Andrews.

Cubism’s formal and conceptual innovations and its investigations into the representation of time, space and motion have continuing relevance for artists today, who variously adapt, develop, quote and critique aspects of cubist practice. In this exhibition, Cubism’s shifting, multi-perspectival view of reality takes on new form in moving-image works by John Dunkley-Smith and Daniel Crooks, in paintings by Melinda Harper and sculptures by James Angus. The use of found objects and recycled materials by Madonna Staunton, Rosalie Gascoigne and Masato Takasaka extends ideas originating in cubist sculpture and collage. Other artists are critical of Cubism, bringing Indigenous and non-european perspectives to bear on its modernist history, particularly its appropriation of so-called ‘primitive art’.

Text from the Heide Museum of Modern Art website [Online] Cited 10/01/2010 no longer available online

Grace Crowley (Australian, 1890-1979)

Abstract painting

1947

Oil on board

63.2 x 79.0cm

Private Collection, Sydney

Godfrey Miller (New Zealand, 1893-1964; worked in England 1933-1939, Australia 1939-1964)

Still Life with Musical Instruments

1958

Pen and ink and oil on canvas

65.5 × 83.0cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Felton Bequest, 1963

© National Gallery of Victoria

Introduction

Cubism & Australian Art considers the impact of the revolutionary and transformative movement of Cubism on Australian art from the early twentieth century to the present day. Cubism was a movement that changed fundamentally the course of twentieth-century art, and its innovations – the shattering of the traditional mimetic relationship between art and reality and investigations into the representation of time, space and motion – have continuing relevance for artists today. Works by over eighty artists, including key examples of international Cubism drawn from Australian collections, are displayed in the exhibition.

The exhibition examines not only the period contemporaneous with Cubism’s influence within Europe, but also the decades from then until the present day, when its reverberations continue to be felt. In the first part of the century, Cubism appeared through a series of encounters and dialogues between individuals and groups resulting in a range of fascinating adaptations, translations and versions alongside other more programmatic or prescriptive adoptions of cubist ideas. The exhibition traces the first manifestations of Cubism in Australian art in the 1920s, when artists studying overseas under leading cubist artists began to transform their art in accordance with such approaches. It examines the transmission of cubist thinking and its influence on artists associated with the George Bell School in Melbourne and the Crowley-Fizelle School in Sydney. By the 1940s, artists working within the canon of modernism elaborated on Cubism as part of their evolutionary process, and following World War II Cubism’s reverberations were being felt as its ideas were revisited by artists working with abstraction.

In the postwar years and through to the 1960s, the influence of Cubism became more diffuse, but remained significant. In painting, cubist ideas provided an underlying point of reference in the development of abstract pictorial structures, though they merged with other ideas current at the time, relating in the 1950s, for example, to colour, form, musicality and the metaphysical. For many artists during this decade, Cubism provided the geometric basis from which to seek an inner meaning beneath surface appearances, to explore the spiritual dimension of painting and to understand modernism.

The shift from a Cubist derived abstraction in Australia in the 1950s to a mild reaction against Cubism in the Colour field and hard-edged painting of the mid to latter 1960s reflected a new recognition of New York as the centre of the avant-garde. Cubism’s shallow pictorial space, use of trompe l’oeil and fragmentation of parts continued to inform the work of certain individuals who adapted them in ways relevant to the new abstraction. Cubist ideas and precepts also found some resonance in an emphasis on the flatness of the canvas, particularly as articulated in the formalist criticism of Clement Greenberg.

The influence of Cubism on Australian art from 1980s to 2000s is subtle, varied and diffuse as contemporary artists variously quote, adapt, develop and critique aspects of cubist practice. Cubism’s decentred, shifting, multi-perspectival view of reality takes on new form, in moving-image works and installations, as well as being further developed in painting and sculpture. Post-cubist collage is used both as a method of constructing artworks – paintings, sculptures, assemblages – and as an intellectual strategy, that of the postmodern bricoleur. Several artists imagine alternative cubist histories and lineages, revisiting cubist art from an Indigenous or non-European perspective and drawing out the implications of its primitivism. Others pay homage to local versions of Cubism, or look through its lens at art from elsewhere.

Heide Education Resource p. 3.

Fred Williams (Australian, 1927-1982)

The Charcoal Burner

1959

Oil on composition board

86.3 × 91.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, purchased 1960

© Estate of Fred Williams

Cubism played a fundamental role in Fred Williams’s pictorial rethinking of the Australian landscape and through him, Cubism has affected the way Australians view their natural surroundings.

Patrick McCaughey writes in the catalogue for this exhibition:

The charcoal burner, with its reserved palette and briskly delineated planes, is one of his most accomplished essays in seeing the Australian landscape through cubist eyes. Already looking for the ‘bones’ of the landscape, Williams was drawn to the early phase of Cubism, as it gave structure to the unspectacular landscape – the bush in the Dandenongs; the coastal plain around the You Yangs.

Just as Braque in his cubist landscapes of 1908-1909 eschewed ‘view’ painting and disdained the picturesque, so Williams in turn generalised the landscape, constructing it and rendering it taut, modern and vivid. In his landscapes Braque made the important pictorial discovery of passage, fusing solid forms with the surrounding space. Williams exploits this innovation in The charcoal burner, where surface and space are perfectly commingled.

Heide Education Resource p. 1.

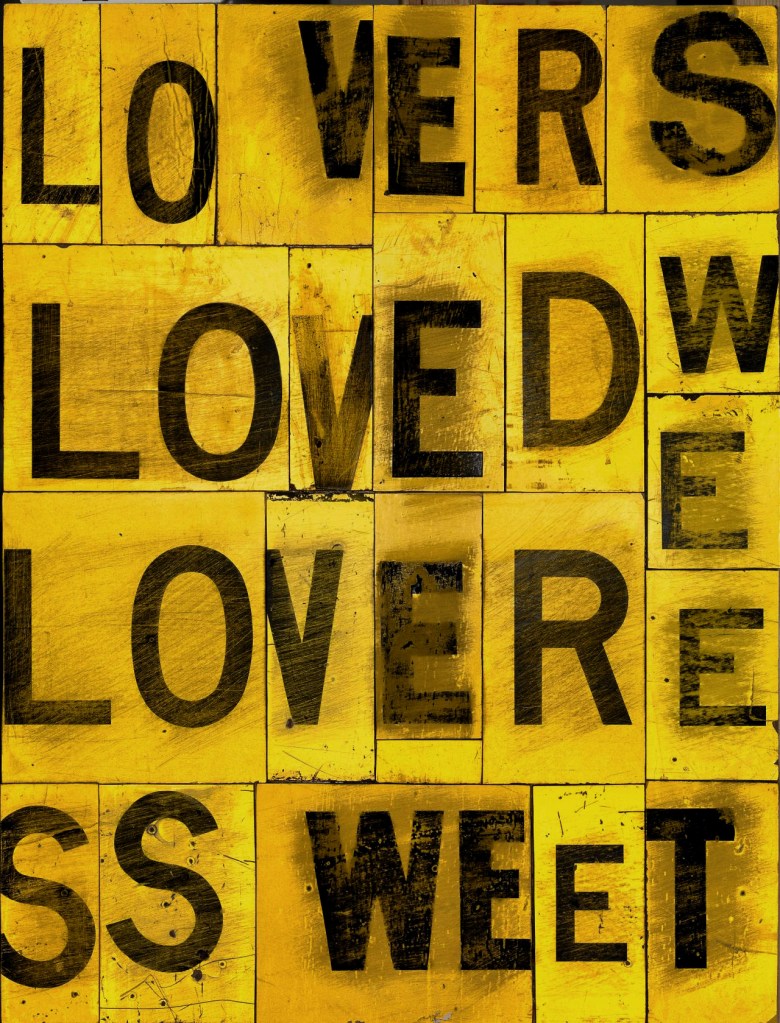

Robert Rooney (Australian, 1937-2017)

After Colonial Cubism

1993

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas

122 x 198.3cm

Heide Museum of Modern Art

Purchased through the Heide Foundation with the assistance of the Heide Foundation Collectors’ Group and the Robert Salzer Fund 2008. Courtesy of the artist

Robert Rooney’s painting After Colonial Cubism (1993) shows a vibrant streetscape rendered in deliberate and self-conscious cubist style that declares itself to be a second-hand quotation of Cubism, rather than an example of the original style. The streetscape has not been drawn from life but is a faithfully scaled-up version of a much earlier gouache sketch Buildings (1953) that Rooney did as a young student in Melbourne. The sketchbook page is indicated in the painting by the vertical bands on either side of the image which effectively serve as quotation marks.

In highlighting the second-hand nature of the image in his painting, Rooney more broadly comments on the dispersal of cubist ideas from Paris, Cubism’s place of origin, to more local contexts such as Australia. The painting carries with it the artist’s memories of his student days, of learning about Cubism through magazines and books. Rooney remembers visiting exhibitions of cubist works by Australian artists and being fascinated by how these ideas were translated locally. Further meaning in the work derives from its title which refers to the painting Colonial Cubism 1954, by Stuart Davis, an American artist whose cubist works are a further instance of the dispersal of the style to localities outside of France.

Heide Education Resource p. 29.

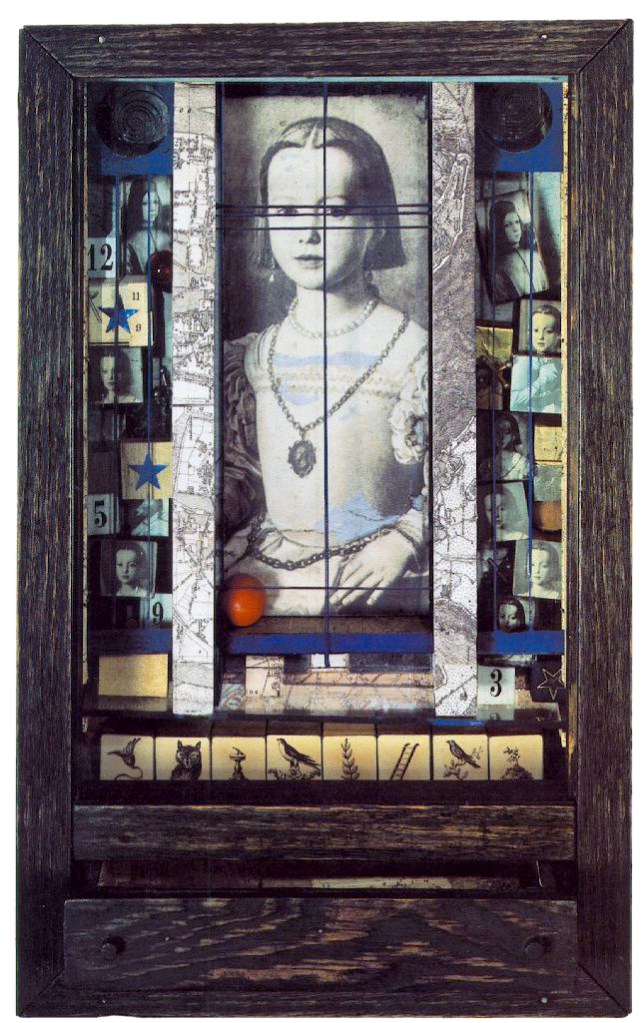

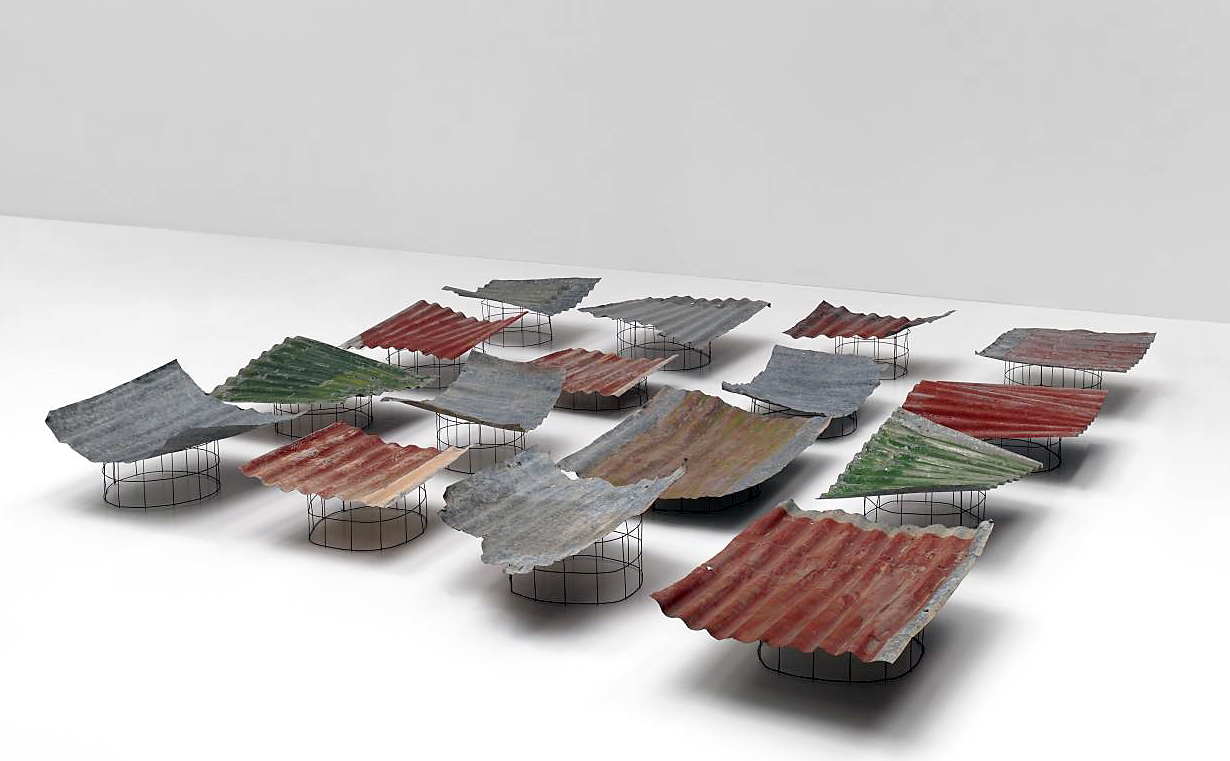

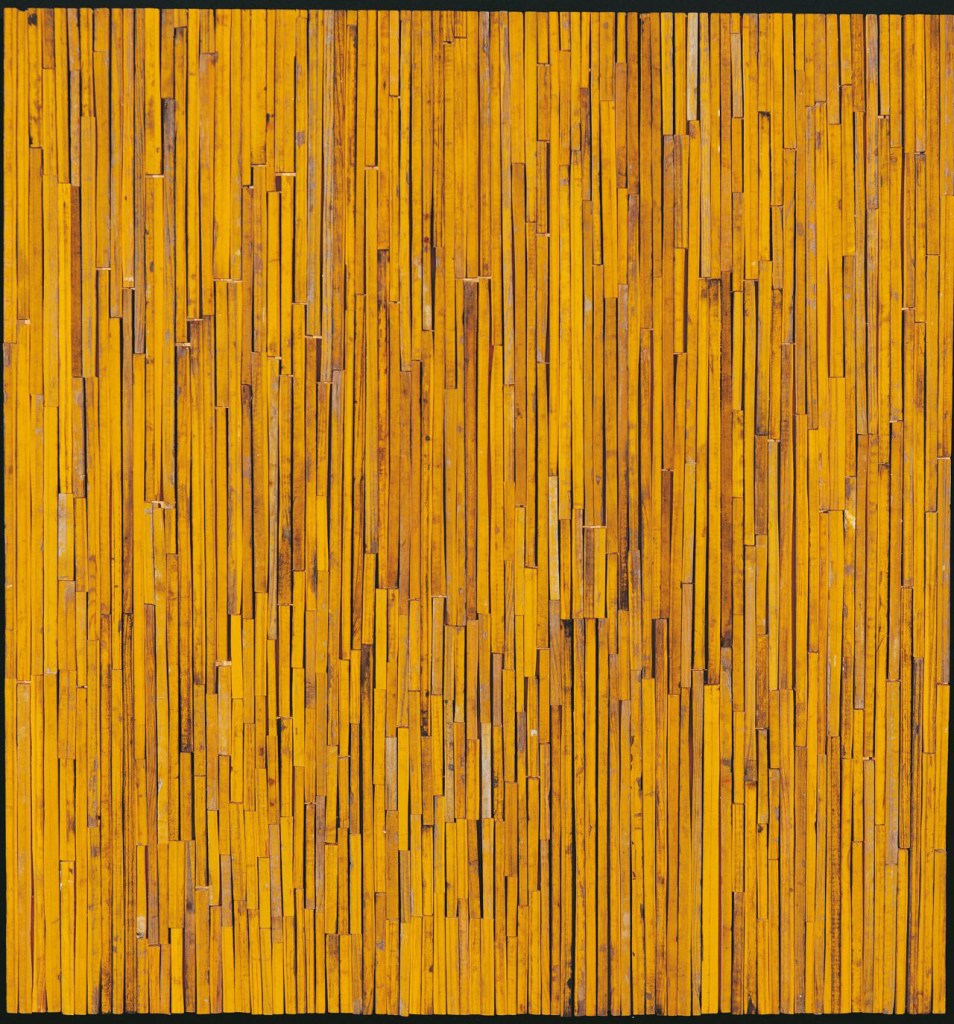

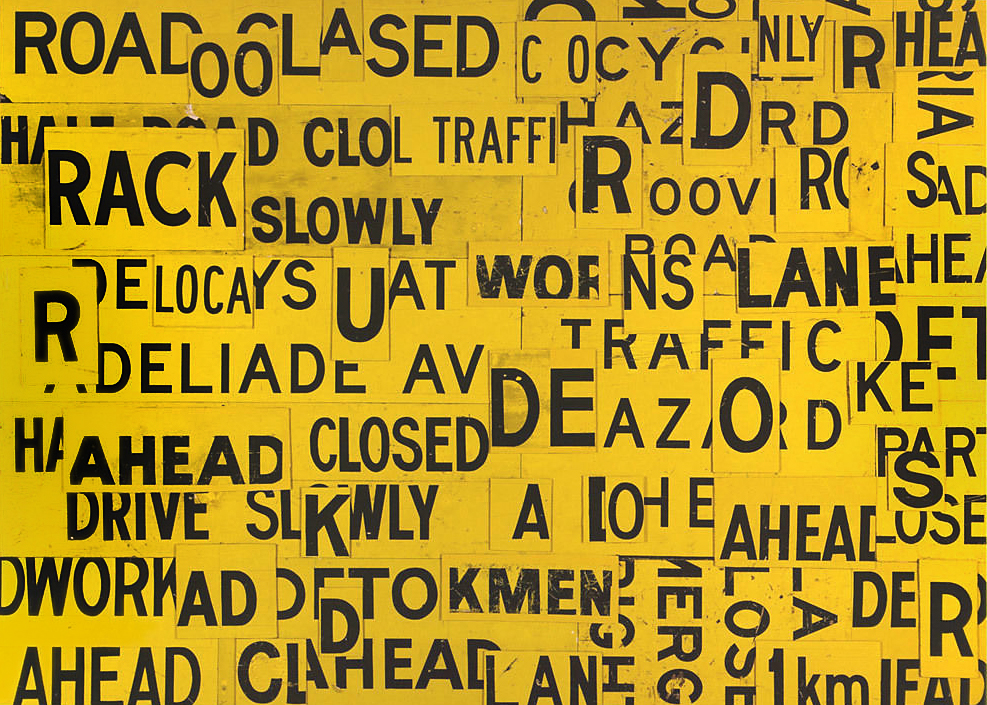

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian, born New Zealand 1917-1999)

Milky Way (detail)

1995

Mixed media

Rosalie Gascoigne is renowned for her sculptural assemblages of great clarity, simplicity and poetic power. Using natural or manufactured objects, sourced from collecting forays, that evoke the lyrical beauty of the Monaro region of New South Wales, her work radically reformulated the ways in which the Australian landscape is perceived. …

“My country is the eastern seaboard. Lake George and the Highlands. Land that is clean scoured by the sun and frost. The record is on the roadside grass. I love to roam around, to look and hear … I look for things that have been somewhere, done something. Second hand materials aren’t deliberate; they have had sun and wind on them. Simple things. From simplicity you get profundity. The weathered grey look of the country gives me a great emotional upsurge. I am not making pictures, I make feelings.”

Rosalie Gascoigne

Extract from Anonymous. “Biography (Roaslie Gascoigne),” on the Art Gallery of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 21/05/2019

Daniel Crooks (New Zealand, b. 1973)

Static No.9 (a small section of something larger) (still)

2005

Single channel digital video, colour, sound

Duration: 00:13:29 min, aspect ratio: 16:9

View a preview of the work: Static No.9 (a small section of something larger) from Daniel Crooks.

James Angus (Australian, b. 1970)

Bicycles

2007

Chromed steel, aluminium, polyeurethane, enamel paint

“An object which is entirely solid yet blurry; a sculpture-in-motion that vibrates between plural and singular.” ~ James Angus

For this handcrafted sculpture, Angus melded the frames of three bicycles into one, creating a kind of platonic ideal of bike design which resolves slight differences in thickness of truss, angles of frame and fork, shape of saddle and handlebar position into an ideal form – one that seems to shift between the plural and the singular. Traces of all three bikes inhabit this final rendition, with its tripled wheel spokes and chain drive, contoured saddle and ridged handlebars.

Hovering between three sets of dimensions and proportions, the sculpture presents a visual experience akin to looking at lenticular imagery or to a stereoscopic gaze, in which two sets of slightly disparate visual information are resolved into the one three-dimensional image. These subtle differences, inhabiting the one object, speak of the slight variations between not only bikes but individual riders, for whom the bike is an extension of their body shape, size and movement. In keeping with his other works, which have distorted, shifted and played with elements of design from architecture to automobiles, Angus disrupts our expectations of an everyday object. By making us look again he reminds us that a bicycle, like a racing car, is a moving sculpture.

Text from the Museum of Contemporary Art website [Online] Cited 21 May 2019

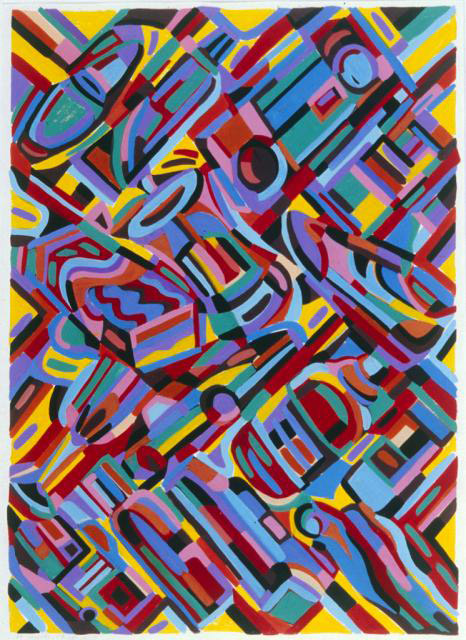

Justin Andrews (Australian, b. 1973)

Acid yellow 3

2008

Acrylic and enamel on composition board

75 x 60cm

Courtesy of the artist and Charles Nodrum Gallery, Melbourne

Masato Takasaka (Australian, b. 1977)

Return to forever (productopia)

2009

Cardboard, wood, plastic, mdf, acrylic, paint, paper, soft-drink cans, tape and discarded product packaging installation

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist

Heide Museum of Modern Art

7 Templestowe Road,

Bulleen, Victoria 3105

Opening hours:

(Heide II & Heide III)

Tuesday – Sunday, Public holidays 10am – 5pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.