Exhibition dates: 5th April – 9th July 2012

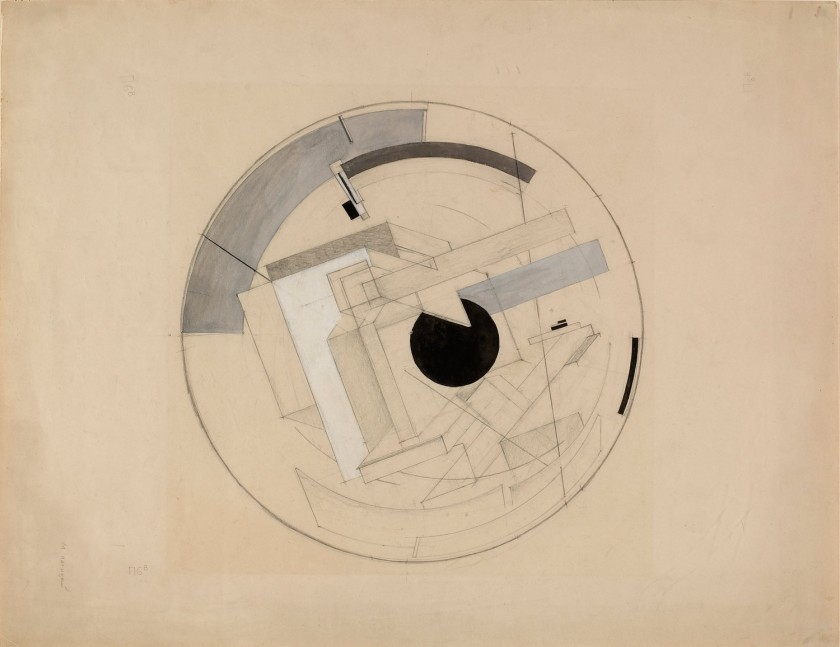

El Lissitzky (Russian, 1890-1941)

Sketch for Proun 6B

1919-1921

Pencil and gouache on paper

34.6 x 44.7cm

© Courtesy the State Museum of Contemporary Art

Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

Ooh, ooh, ooh, I’m in love with the design and the photograph of the Gosplan Garage! The garage survived the Second World War but, like the Cathedral Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, it is now hemmed in and surrounded by cars and apartments (see the YouTube video GosPlan Garage (1934-1936) by Konstantin Melnikov). Looking at early photographs of both buildings – in the basement of the Sagrada Familia if you go, the Cathedral surrounded by green fields and cows – you realise what wonderful space they had to breathe, to exist in the world. Unfortunately, no more!

Marcus

.

Many thankx to Martin-Gropius-Bau for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Photographer unknown

Gosplan Garage: general view

c. 1936

Archival Index Card and photographs(s)

13.6 x 20cm

Architects: Konstantin Melnikov with V. I. Kurochkin, 1936

© Courtesy the Department of Photographs, Schusev

State Museum of Architecture, Moscow

Melnikov, Konstantin Stepanovich (1890-1974)

Born on the outskirts of Moscow into a poor family of peasant origin, Melnikov served a short apprenticeship as an icon painter and was then apprenticed to an engineering firm, one of whose owners noticed his talent for drawing and sent him to the Moscow Institute for Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. He graduated initially in painting and then in 1917 in architecture. From 1918 he worked in a Mossovet architectural studio under Aleksei Schusev and Ivan Zholtovskii but his early projects for housing schemes show him abandoning the Classicism of his teachers. In his pavilion for the Makhorka tobacco firm at the 1923 All-Union Agricultural Exhibition Melnikov developed this exuberant angularity by giving different parts of the pavilion different heights and setting the sloping roofs at right angles to each other. Irregular fenestration and an external staircase – crowded with visitors in some photographs – add to the sense of animation. The construction is entirely of timber, the first evidence of Melnikov’s abiding interest in combining traditional materials with avant-garde design. His Soviet Pavilion for the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris would also feature timber construction, an animated roofscape and an external staircase. However, it achieved a more logical design by simplifying the plan into a rectangle bisected by stairs rising and descending across its centre. During the second half of the 1920s Melnikov completed five workers’ clubs in the Moscow region for the Rusakov (1927), Frunze, Kauchuk, Pravda and Burevestnik trades unions. He favoured interiors with large flexible spaces, sometimes using movable panels, and opposed the Functionalist tendency to create a large number of highly specialised areas. This gave him the freedom to mould bold internal volumes and create dramatic exteriors. His own house, consisting of two interlocking cylinders, was designed on the same principles (1927-1931). His garages – Bahkmetevskaia, Novo Ryanskaia and Gosplan (1936) – on the other hand, though still characterised by dramatic exteriors, are based on a careful analysis of vehicular movement. Despite being briefly associated with ASNOVA, Melnikov appears a rather solitary figure, his beliefs about the design process differing from the main groupings of 1920s architects. Heavily criticised in the 1930s for his ‘Formalism’, he was largely excluded from employment and teaching and no significant buildings were constructed to his design during the last 40 years of his life.

Photographer unkown

Bakery: exterior showing the four production levels

1938

Archival Index Card and photographs(s)

9.3 x 14.6cm

Engineer: Georgii Marsakov, 1931

© Courtesy the Department of Photographs, Schusev

State Museum of Architecture, Moscow

In 1931 the engineer Georgii Marsakov designed a mass-production bakery in Moscow and the Narvskii Factory Kitchen opened in St Petersburg to provide communal eating facilities for local residents. Rapid expansion of motorised transport called for a significant reappraisal of the garage, for which Konstantin Melnikov produced four highly innovative designs in Moscow.

Photographer unknown

Havsko-Shabolovskii residential block and Shabolovska Radio tower viewed from the walls of the Donskoy Monastery

1929

Archival Index Card and photographs(s)

11.5 x 16.9cm

© Courtesy the Department of Photographs, Schusev

State Museum of Architecture, Moscow

Liubov Popova (Russian, 1889-1924)

Spatial Force Construction

1921

Oil and marble dust on plywood

71 x 63.9cm

© Courtesy the State Museum of Contemporary Art

Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

Photographer unknown

DneproGES: dam under construction

1931

Archival Index Card and photographs(s)

12.3 x 17.3cm

Aleksandr Vesnin, Nikolai Kolli, Georgii Orlov, Sergei Andrievskii, 1927-32

© Courtesy the Department of Photographs, Schusev

State Museum of Architecture, Moscow

The DneproGES Dam and Hydroelectric Power Station (designed with Nikolai Kolli, Georgii Orlov and Sergei Andrievskii, 1927-32) represents not only Vesnin’s first important industrial project but also a major achievement of Stalin’s First Five Year Plan.

The exhibition Building the Revolution sheds light on an area of the Soviet avant-garde that has remained relatively unknown in Europe and beyond: architecture. Even in Russia and the other successor states of the former Soviet Union the names of most of the architects have been largely forgotten. Their structures have not become part of the collective cultural memory to the extent that the “New Building” movement in the West has.

The exhibition presents this impressive chapter in the history of the avant-garde in an unusual way in that it binds together three thematic strands. Selected works of the early avant-garde, such as those of El Lissitzky, Gustav Klutsis, Liubov Popova, Alexander Rodchenko or Vladimir Tatlin, show the artists’ intense preoccupation from 1915 onwards with questions of form, space and texture. After the Revolution they were active in the various bodies concerned with the implementation of these ideals, such as the Commission for the Synthesis of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (1919-1920). It was there that the architects Nikolai Ladovskii, Vladimir Krinsky and the painter Rodchenko created the first designs for town planning and communal housing. In 1919 Tatlin produced his famous design for a “Monument to the Third International” – a complex engineering structure with moving spaces. Although never built, its visionary potential, and dynamic formal language influenced the later architecture of Constructivism. Whereas the impressive pictures and drawings of the Costakis Collection in Thessaloniki make clear what a role was played by architectural themes in the early artistic designs, vintage prints from the Shchusev State Museum of Architecture in Moscow give an idea of the unleashing of architectural energies which took place a few years later. The historical photographs show that the new structures embodied a new age, not only in a typological sense, but in terms of scale. They towered above the old urban buildings and acted as a torch signalling the coming industrialisation and transformation of the country. The photographs of the renowned British architectural photographer, Richard Pare, on the other hand, lead the viewer back to the present. Pare had begun to rediscover this lost avant-garde in 1993. In the course of several trips to Moscow and St. Petersburg, as well as to the former Soviet republics, he documented what remained of the buildings. His shots bring out their beauty and the inventiveness of their creators while at the same time tracing the course of their decay. In that sense they draw a picture of a post-Soviet society that is unaware of its extraordinary heritage.

What was new about this architecture was not only the formal idiom, but also the tasks it was supposed to perform. With the building of the new society workers’ clubs, trade union houses, communal apartments, sanatoria for the workers, state-owned department stores, party and administrative buildings, as well as power stations and industrial plants to modernise the country.

The first important structure to be erected after the Revolution was Vladimir Shukhov’s Shabolovka Radio Tower, built in the years 1919-1922 and consisting of six hyperboloids mounted on top of one another. At 150 metres it was the tallest tower in the world of its kind at the time. Its elegant filigree structure became a symbol of how all that was old and ponderous could be surmounted. Rodchenko’s well-known photos of the radio tower – today seen as icons of avant-garde photography – stress the dynamics from above and below. Pare’s shots of the tower focus more on details, thus emphasising the construction techniques of the time.

The achievements of Russian engineers like Shukhov, with their novel technical designs, influenced the development of an architecture that used clear, geometrical forms that were in keeping with its functions. In the course of the 1920s there arose two clearly defined tendencies in architecture: Rationalism and Constructivism. In 1923 representatives of the first founded the Association of New Architects (ASNOVA), whose leading light was Ladovskii. Among the Constructivists Alexander Vesnin and Moisei Ginzburg played major roles. In 1925 the Constructivist architects of Moscow joined together to form the Society of Contemporary Architects (OSA). There were also other tendencies as well as outstanding individualists, such as Konstantin Melnikov. Despite polemical squabbles among the tendencies a modern style of building had consolidated itself by the end of the 1920s.

In the course of the industrialisation of the country under the first Five-Year Plan (1928-1932) the building of new towns proceeded apace. This gave rise to questions concerning the concept of the city, for which various solutions were proposed, such as the “horizontal skyscrapers” for Moscow or Ladovskii’s “parabola” as the basic pattern of urban development. Quite a few of the buildings photographed by Pare were developed for communal living. The Narkomfin (People’s Commissariat for Finance) residential block built in Moscow in 1930 by Ginzburg and Ignati Milinis was one of the most experimental projects of that era. In addition to two floors of apartments it contained a communal canteen, a crèche, a gymnasium and a scullery. Other types of construction designed to promote the collectivist way of life were canteen kitchens, three of which were built in what was then Leningrad by a group associated with Iosif Meerzon and representing Rationalism. Workers’ clubs and palaces of culture offered numerous educational opportunities, symbolising with their dynamic forms the role of the new class in the urban environment.

When in the mid-1930s the political climate in the Soviet Union underwent a fundamental change, and a monumental style of architecture based on Classical models found favour with the powers that be, this exciting chapter of avant-gardism came to an end and sank into oblivion.

El Lissitzky (Russian, 1890-1941)

Monument to Rosa Luxemburg

1919-1921

Pencil, ink and gouache on paper

9.7 x 9.7cm

© Courtesy the State Museum of Contemporary Art

Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

M.A. Ilyin (Russian)

Narkomfin Communal House: corner detail of residential block

1931

Archival Index Card and photographs(s)

11.6 x 8cm

Architects: Moisei Ginzburg, Ignatii Milinis, 1930

© Courtesy the Department of Photographs, Schusev

State Museum of Architecture, Moscow

Moisei Ginzburg

There was also the exchange with the Europeans. Le Corbusier came to Moscow and met and shared ideas with a number of architects including Moisei Ginzburg, the founder of the Constructivist movement and its chief theoretician. His 1924 treatise Style and Epoch was the most influential document of the Constructivist movement. Because he was Jewish, he was prevented from undertaking his architectural training in Russia and went to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and the Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan. Aleksandr Rodchenko travelled to Paris with Melnikov, who built the Soviet Pavilion at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. They were all very well versed in European culture of the time. Ginzburg’s Style and Epoch responds to Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture of the previous year, but Ginzburg takes the warship and the communal house rather than the luxury liner and the private villa as his examples.

Gustav Klutsis (Latvian, 1895-1938)

Design for Loudspeaker No.7

1922

Pencil, ink and gouache on paper

26.9 x 17.7cm

© Courtesy the State Museum of Contemporary Art

Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

Alexander Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1956)

Linearism

1920

Oil on canvas

110.5 x 78cm

© Courtesy the State Museum of Contemporary Art

Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

M.A. Ilyin (Russian)

Melnikov House: entrance façade

1931

Archival Index Card and photographs(s)

11.7 x 9cm

Konstantin Melnikov, 1927-31

© Courtesy the Department of Photographs, Schusev

State Museum of Architecture, Moscow

Martin-Gropius-Bau Berlin

Niederkirchnerstraße 7

Corner Stresemannstr. 110

10963 Berlin

Phone: +49 (0)30 254 86-0

Opening hours:

Wednesday to Monday 10 – 19 hrs

Tuesday closed

You must be logged in to post a comment.