Exhibition dates: 2nd December, 2017 – 11th February, 2018

Curator: Victoria Lynn

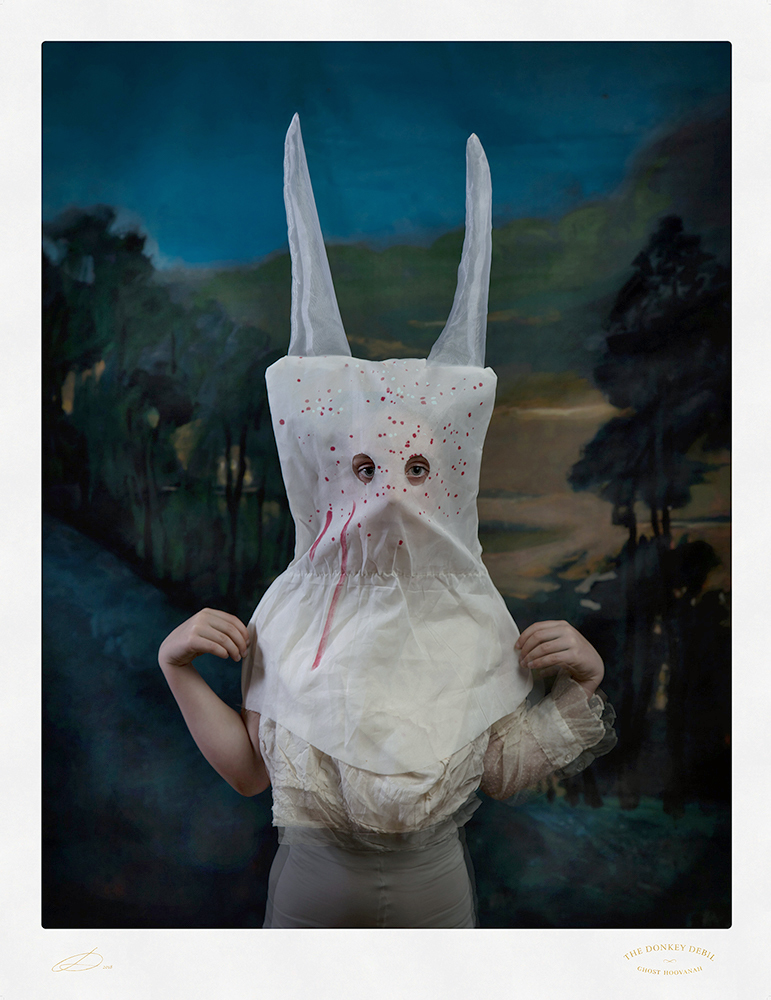

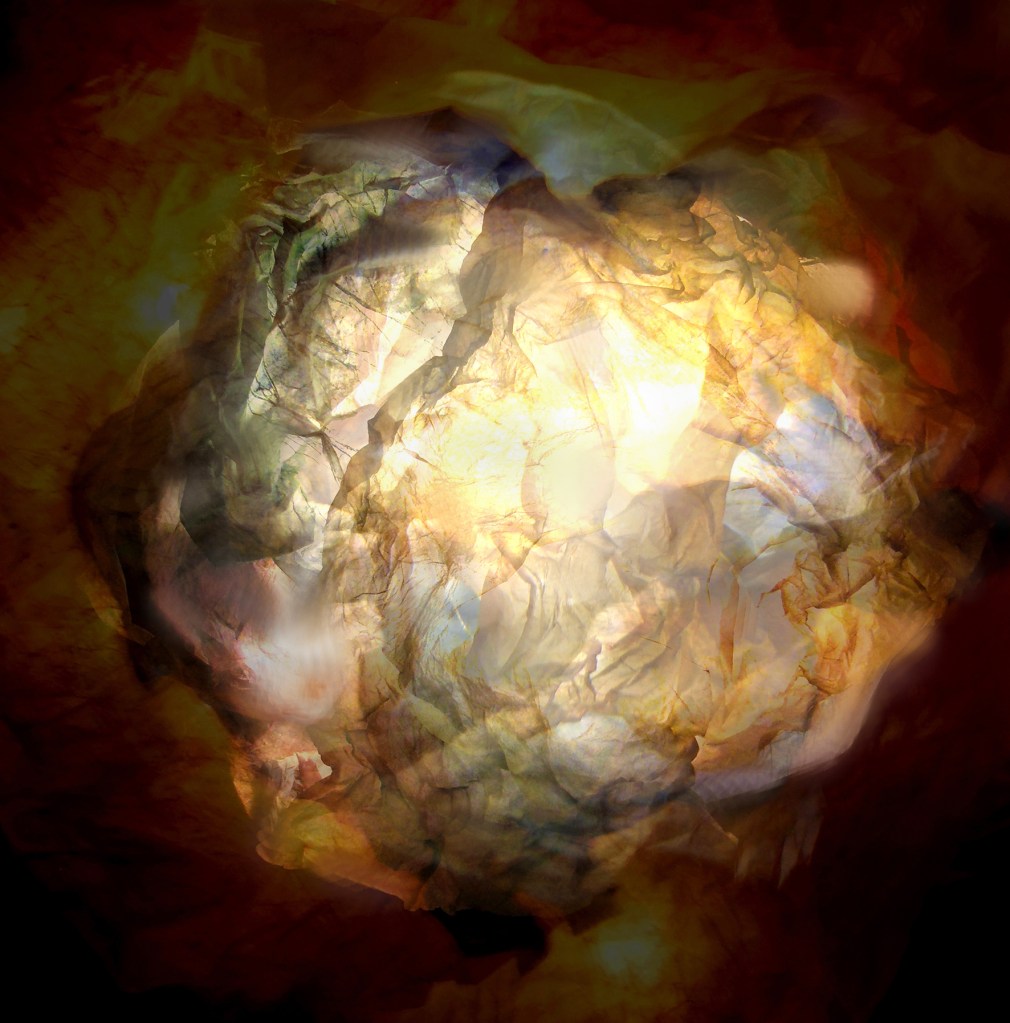

Rosemary Laing (Australian, 1959-2024)

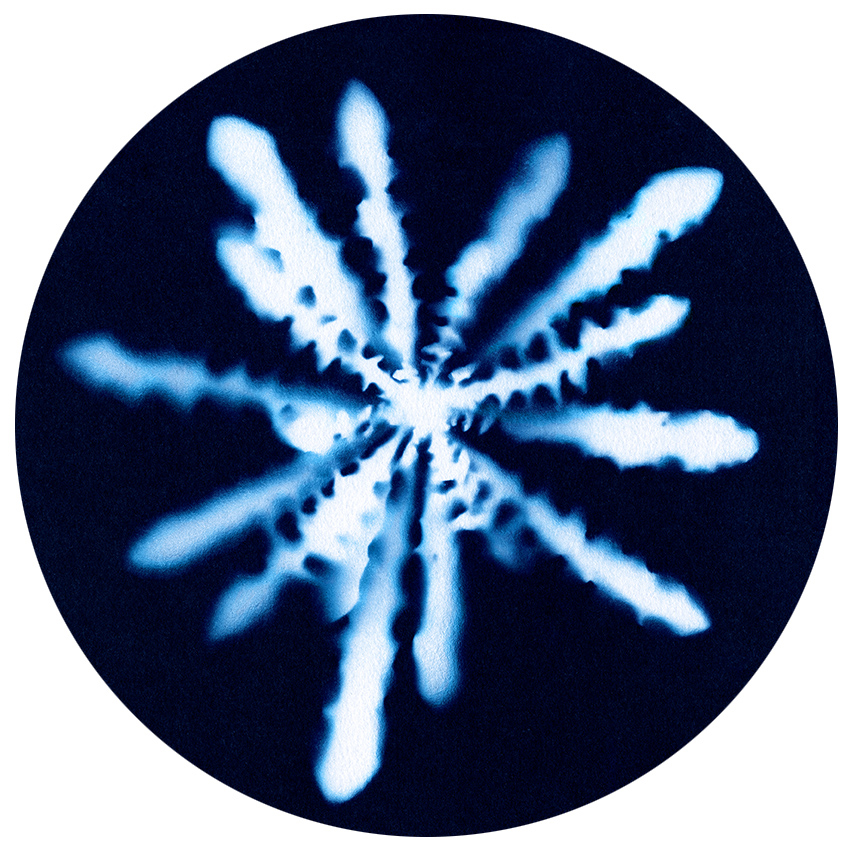

weather (Eden) #1

2006

From the series weather

C Type photograph

110 x 221.5cm

Private Collection

© Rosemary Laing, Courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Disjunction and displacement in the Australian landscape

On a suitably apocalyptic day – in terms of our relationship to landscape, environment, elements and shelter – I drove up the Yarra Valley to the beautiful TarraWarra Museum of Art to see an exhibition of the works of Rosemary Laing. Through teeming rain, headlights gleaming, windshield wipers at full bore listening to Beethoven symphonies, I undertook an epic drive up to that most beautiful part of Victoria. The slightly surreal, disembodied experience of the drive continued once I stepped inside the gallery to view Laing’s work.

Laing’s work has always been a favourite, whether it be the floating brides, the carpet laid through the forest, or the melting newsprint after rain. I have always thought of her sensitive conceptual, performative work as evidenced through large, panoramic photographs as strong and focused, effective in challenging contemporary cultural cliché relating to the land, specifically the possession and inhabitation of it. As such, perhaps I was expecting too much of this exhibition but to put it bluntly, the presentation was a great disappointment.

There are various contributing factors that do not make this exhibition a good one.

Firstly, as the curator Victoria Lynn observes, “Laing’s photographs are conceived in series, so that each photograph is part of a larger cluster of images that are often arrange in specific sequences.” This exhibition, “includes 28 large-scale works selected from ten series over a thirty-year period” that focus on the themes of land and landscape in Laing’s oeuvre. The problem with this approach to Laing’s work is that the photographs from the different series sit uncomfortably together. The transitions between the photographs and different bodies of work as evidenced in this exhibition, simply do not work. Minor White’s ice / fire – that frisson of intensity between two disparate images that makes both images relevant to each other – is non-existent here. What might have more successful in displaying Laing’s work would have been a larger selection from a more limited number of series. It would have given the viewer a more holistic sense of belonging and investment in the work. This is the problem working in series and specific sequences… once the work leaves that cluster of energy, that magical place of nurture, nature and conceptualisation, how does it reintegrate itself into other states of being and display?

Secondly, the light levels in the gallery were so low the photographs seemed drained of all their energy. I understand that the “lux levels are quite particular according to museum requirements considering many works are lent from various institutions around Australia,” having done a conservation subject during my Master of Art Curatorship, but this is where the surreal experience from the drive continued: upon entering the gallery it was like navigating a stygian gloom, as can be seen in the installation photographs of the exhibition below. This is a museum of art situated in the most beautiful landscape and these are photographs, captured with light! that need light to bring them alive. I remember seeing Laing’s work leak at Tolarno galleries in Melbourne, and being amazed by their presence, their energy. Not here. Here the blues of the sky and the reds of the carpet seemed drained of energy, the vibrations of being of the forest and land victim to overzealous preservation.

Thirdly, and this relates to the first point, there was one work How we lost poor Flossie (fires) (1988, below) from Laing’s early series Natural Disasters. The work appeared out of nowhere at the end of the exhibition, had nothing that it related to around it, and had no explanation as to why it was there. I really would have liked to have known more about how Laing got from this work to the later series in the exhibition. What was her process of discovery, of change and experimentation. How did Laing go from Flossie – slicing together the spectacle and graphic imagery from media coverage of the Ash Wednesday fires – to the embeddedness [definition: the dependence of a phenomenon on its environment, which may be defined alternatively in institutional, social, cognitive, or cultural terms] of performances within the landscape of the later work? This would have been a more cogent, pungent and relevant investigation into the rigours of Laing’s art practice.

I emerged into the world and it was still pouring with rain. I rejoiced. It was as though I was alive again. Laing’s work is always strong and interesting. It was just such a pity that this iteration of it, specifically its closeted choreography, was not as restless as the landscape the works imagine.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the TarraWarra Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photograph for a larger version of the image. All installation images © Dr Marcus Bunyan and TarraWarra Museum of Art.

Installation view of the exhibition Rosemary Laing at the TarraWarra Museum of Art featuring the works welcome to Australia (2004, C Type photograph, Collection of the University of Queensland) from the series to walk on a sea of salt

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

“… the detention centre images, so that you’ve got the Heysen, you know, trees that you want to belong to, and then you’ve got this endless vista – though it be a difficult journey across a horizon that never ends – and then you have the raised wire fence, completely closing off access to that land, and that place, and those images of belonging and heritage.”

Art Talk with Rosemary Laing

Installation view of the exhibition Rosemary Laing at the TarraWarra Museum of Art featuring the works after Heysen (2004) at left, and to walk on a sea of salt (2004) at right, from the series to walk on a sea of salt

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s after Heysen (2004, C Type photograph, Collection of Carey Lyon and Jo Crosby) from the series to walk on a sea of salt

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

The question of how to belong in Australia permeates Laing’s work. Australia has one of the highest immigrant populations in the world so that the question of arrival, and of making oneself at home, continues to be part of the everyday reality. We also have one of the world’s harshest policies for asylum seekers so that – in the political imaginary of contemporary Australia – land is conceived as a border that has to be protected.

The artist’s most potent response to the contested issue of being at home in Australia is the 2004 series to walk on a sea of salt, where images of Woomera detention centre, combined with photographs inspired by quintessential Australian imagery and stories, remind us that home does not travel with the asylum seeker. In after Heysen, Laing photographs the trees that Hans Heysen transformed into an Arcadian image of the Australian bush, but bleaches the image to invoke a sense of nationalistic nostalgia. By contrast, the spatial potential and magnitude of the Australian landscape is invoked by the image to walk on a sea of salt.

Wall text from the exhibition

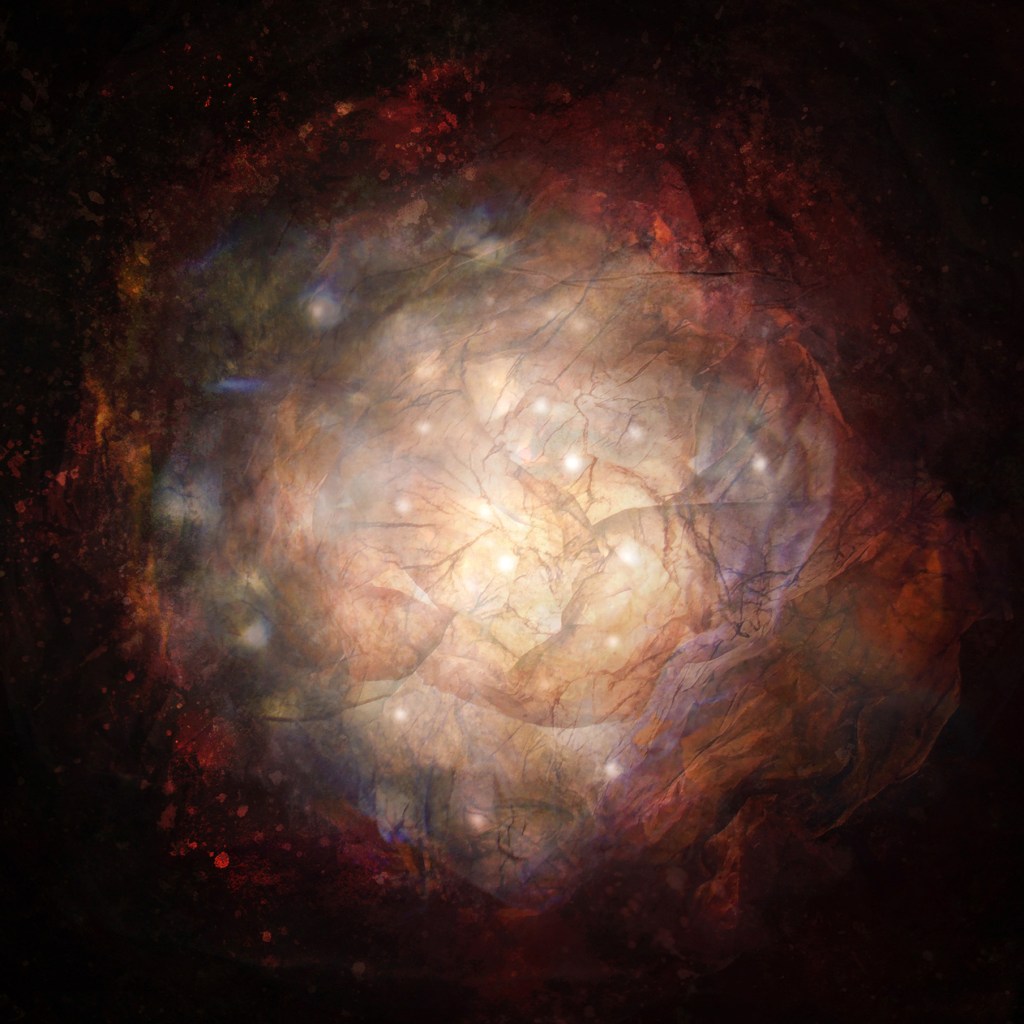

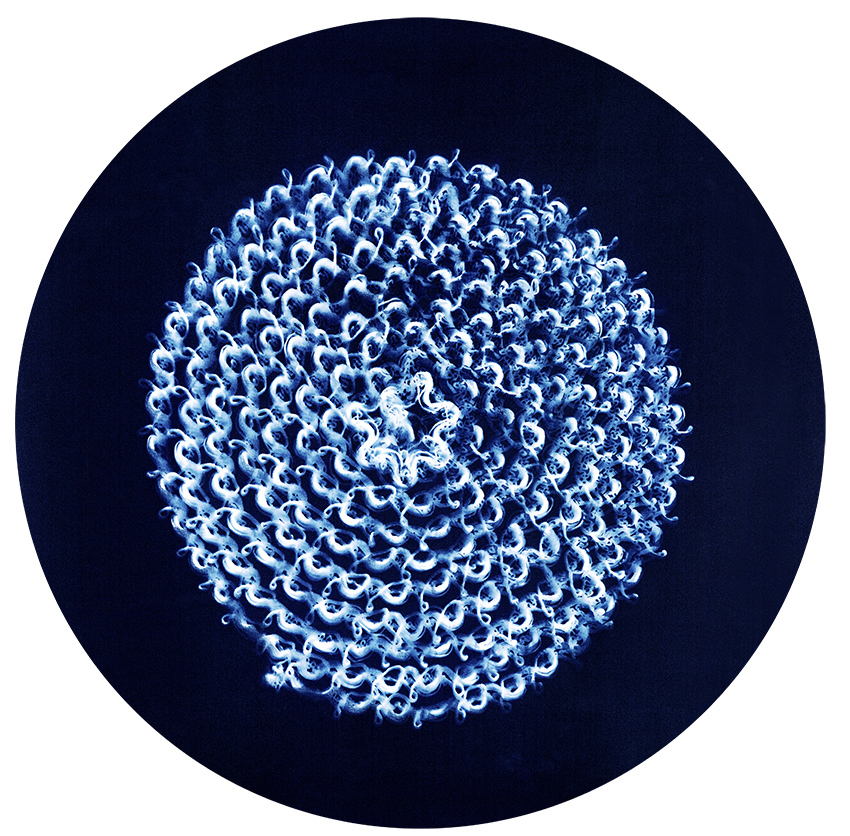

Installation view of the exhibition Rosemary Laing at the TarraWarra Museum of Art featuring works from the series The Paper (2013)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work The Paper, Tuesday (2013, C Type photograph, Monash University Collection) from the series The Paper (2013)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work The Paper, Thursday (2013, C Type photograph, Monash University Collection) from the series The Paper (2013)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Laing choreographs situations in the landscape, invoking a unique set of circumstances that reflect upon historic, social, environmental, economic and material conditions. Incongruous items are carefully positioned to flow with the compositional logic of a place.

On a hillside in Bundanon, New South Wales is a Casuarina forest sprinkled with Burrawang (cycads), an ancient plant that dates back to the Palaeozoic. The series The Paper was created on this hillside. The forest floor is covered in newspaper and photographed after the rains. The paper has literally been pressed into the forest floor by the torrent. It has been weathered. The sensationalism, headlines, imagery and opinion of the newspaper merge into a feathery ground cover of soft white, cream and beige hues. It is as if the area has flooded, not with water, but with paper. Words, colour and dates are dissolved into a tonal carpet. There is no light and shadow. This misalignment suggests the death of the daily paper, and here it inevitably returns to its natural habitat, its original ‘home’.

Wall text from the exhibition

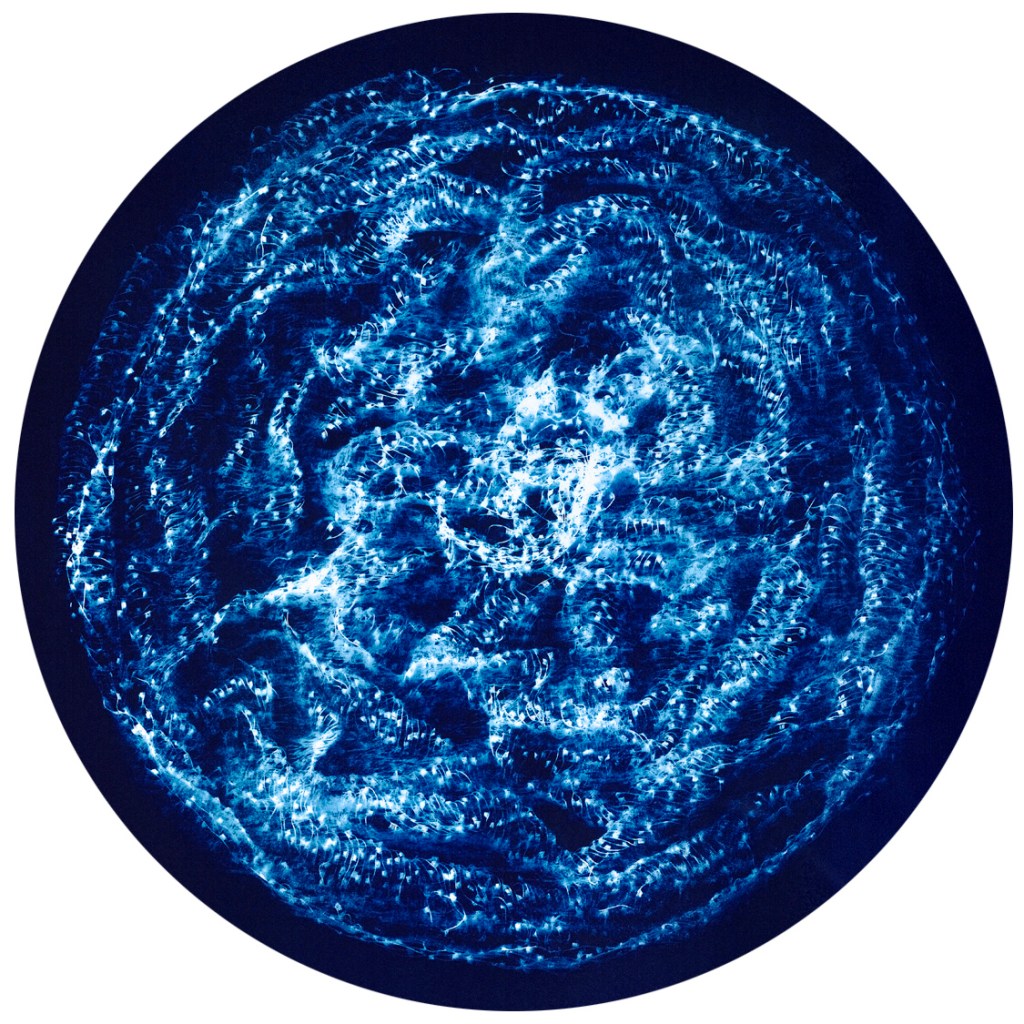

Installation views of the exhibition Rosemary Laing at the TarraWarra Museum of Art

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work weather (Eden) #1 (2006, C Type photograph, Collection of Peter and Anna Thomas) from the series weather

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

The idea of a natural disaster in the Australian landscape occupies the same intensity for Laing as the human or ‘unnatural’ disasters. The each speak of the endless transformation of the landscape, its unfolding stories and its capacity to conjure anxiety and fear.

the series weather, located on the south coast of New South Wales, was inspired by the impact of natural phenomena – coastal storms – on the area. The flash of red fish netting snagged unawares by the battered grey melaleucas in weather (Eden) #1 also signals the historic Indigenous and colonial whaling in the area and the more recent slow demise of the fishing industry. These images seem haunted.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s works The Flowering of the Strange Orchid (2017) left, from the series Buddens, and at right weather (Eden) #2 from the series weather

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Detail of Rosemary Laing’s work The Flowering of the Strange Orchid (2017)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Rosemary Laing at the TarraWarra Museum of Art showing the work Walter Hood (2017) from the series Buddens

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

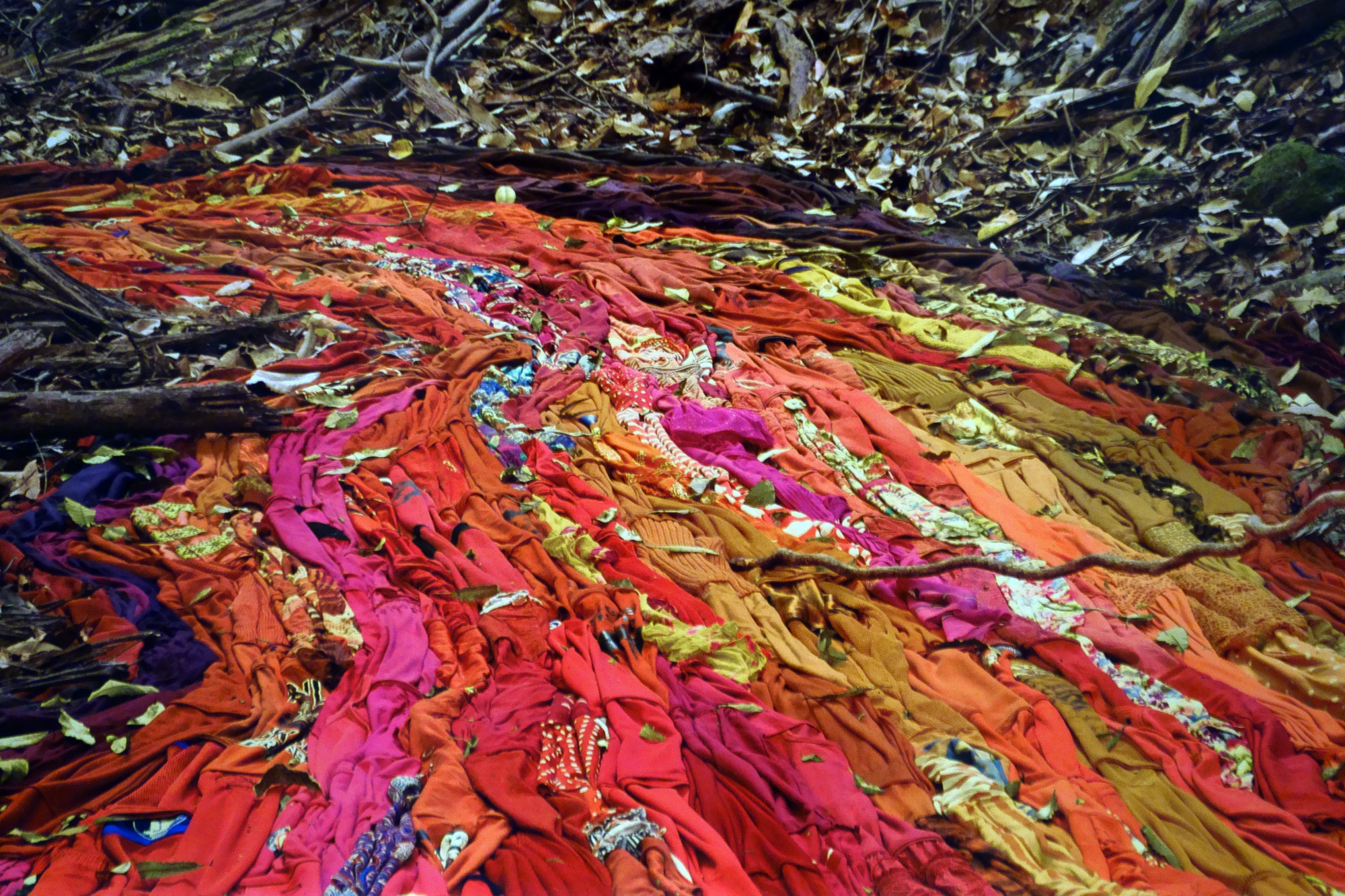

In the most recent series Buddens, Laing turns again to the ‘unnatural disasters’ that impact ‘country’. The stream is covered in rolls of discarded clothing. It leads down to Wreck Bay, on the south coast of New South Wales, and is the site of multiple ship disasters. Historically these waters were used to transport convicts, goods, troops and settlers up and down the coast and they are littered with relics from shipwrecks including those of the vessels ‘Rose of Australia’ and ‘Walter Hood’.

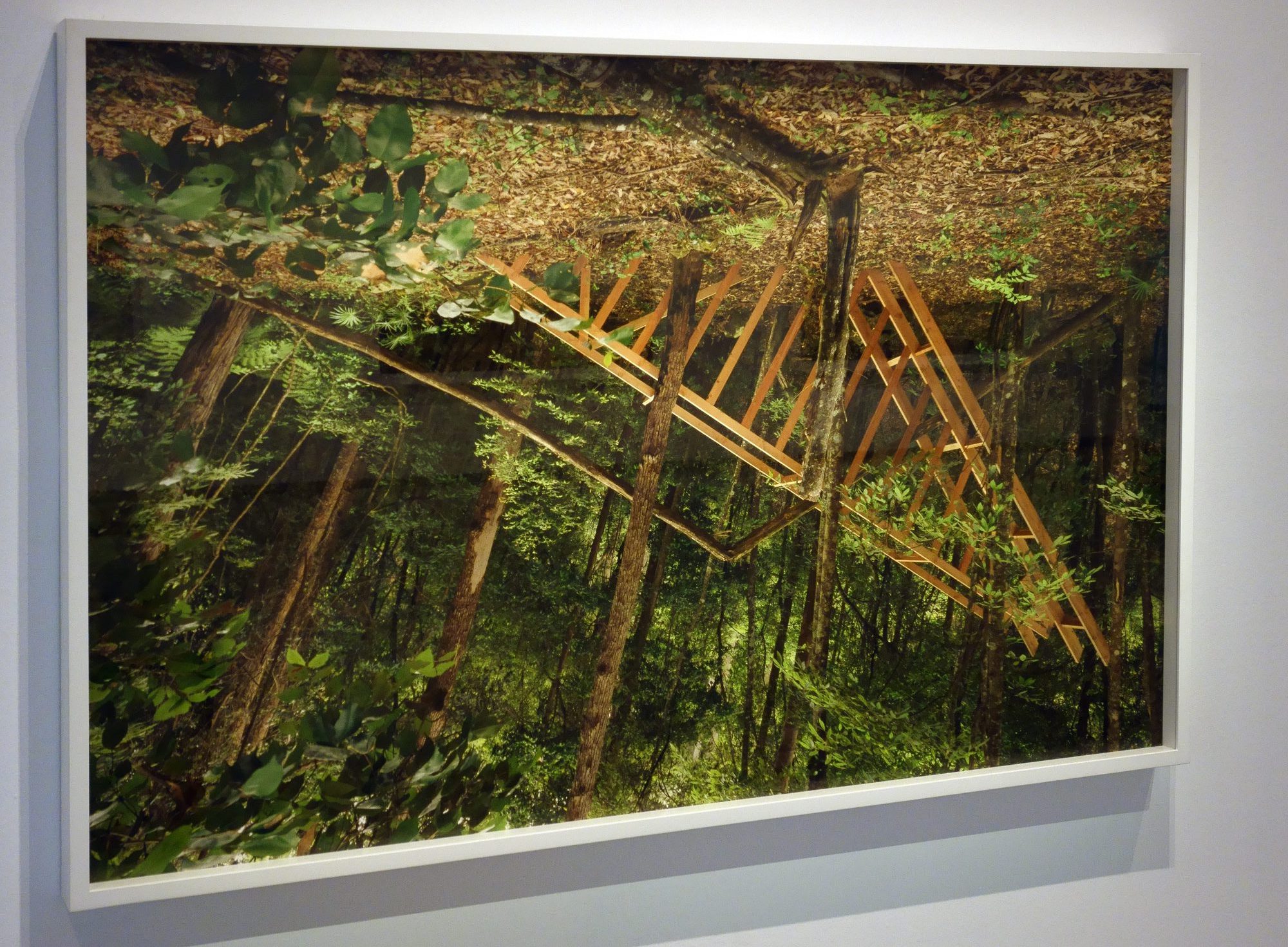

The roof truss is like a piece of wreckage in amongst the trees, as if torn by the winds from an urban development on the outskirts of a city. Recalling the upside down house in the series leak (2010), it meets a natural A-frame in the foliage, yet the two don’t make a safe house.

The clothes seem to push through the landscape, like the rush of a river, perhaps in search of a safe haven. There is a mixture of metaphors in Buddens, highlighting the delicate balance between nature and culture required for survival.

Wall text from the exhibition

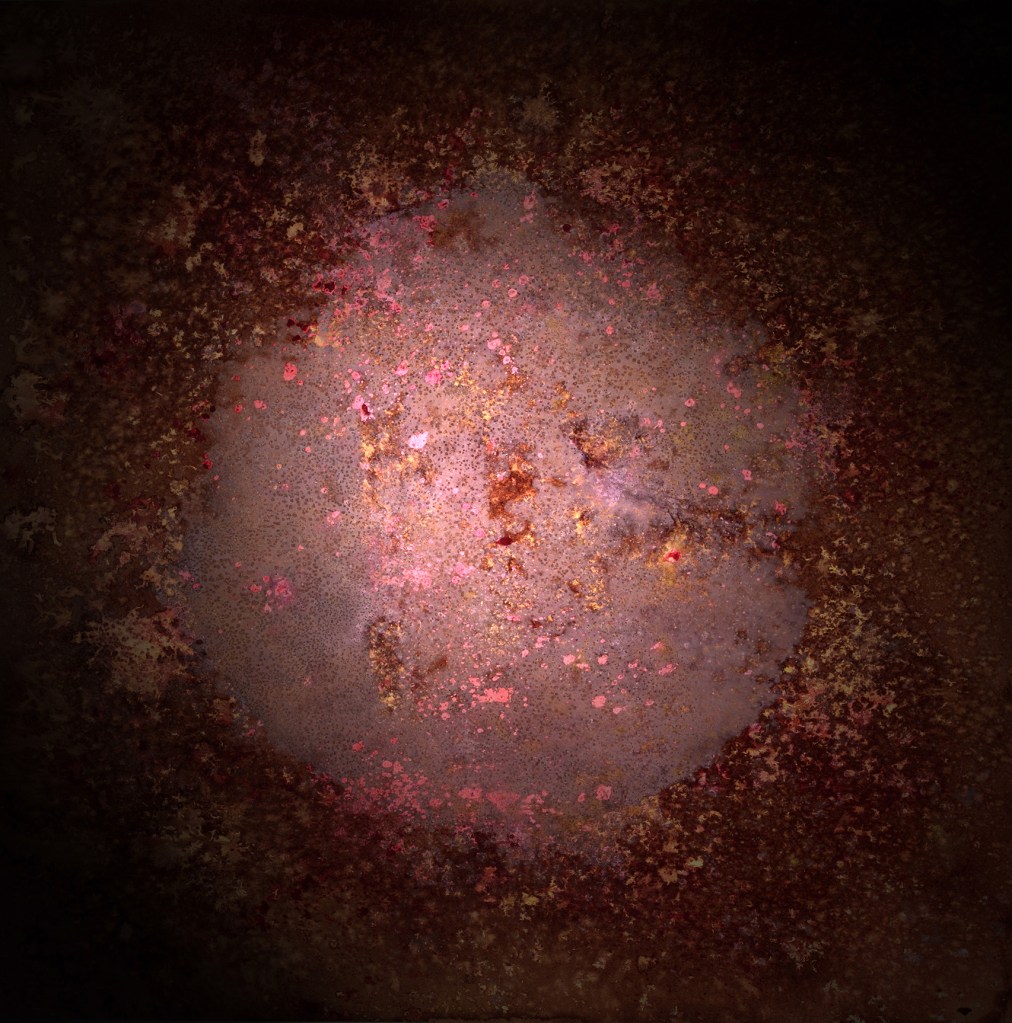

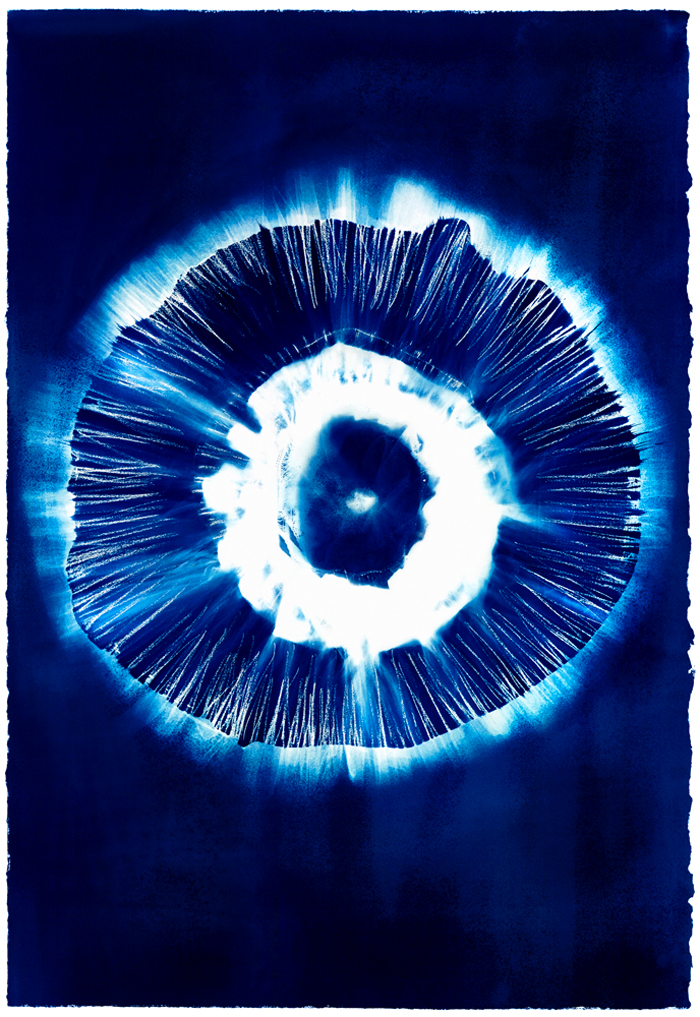

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work brumby mound #5 (2003, C Type photograph, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne) from the series one dozen unnatural disasters in the Australian landscape

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work brumby mound #6 (2003, C Type photograph, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne) from the series one dozen unnatural disasters in the Australian landscape

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Landscape has a past, present an future; it is never the same as it used to be. In the face of wars, wrecks, and both natural and ‘unnatural’ destruction, we build shelters. We fence and furnish these landscape as we try to impose order on the precariousness and relative insignificance of life. As can be seen in a number of Laing’s series, the introduction of elements from our ‘settled’ environment including carpet, clothing, architectural structures, newspapers and the like – creates a disjunction. Some thing is literally awry.

In the one dozen unnatural disasters in the Australian landscape series, red interior furniture occupies and unsuccessfully domesticates this landscape. Painted in red earth and glue, these items almost disappear in the desert landscape. they are both like relics of a lost civilisation, but also seem to have become attuned to the terrain.

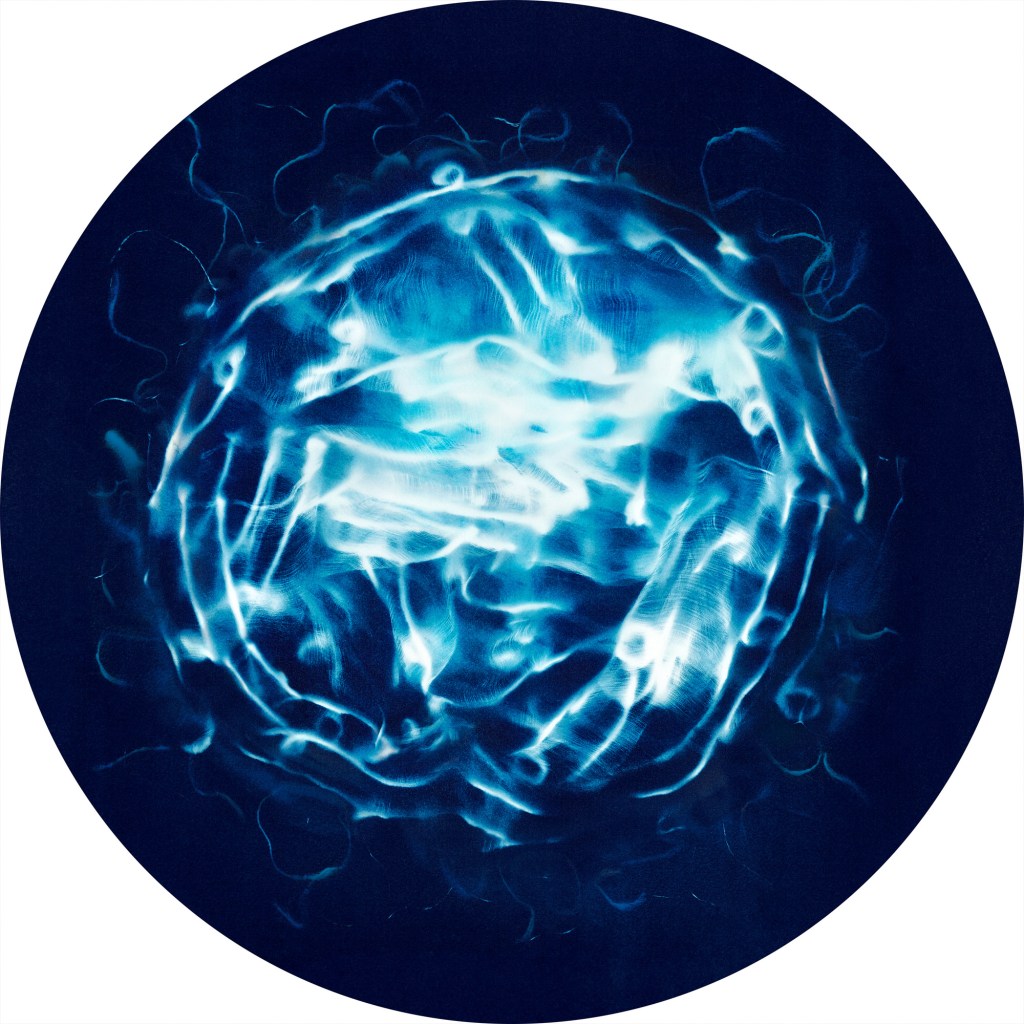

In the series leak, Laing continues her poetic and political engagement with the Australian landscape whereby powerful and dynamic tensions are elicited through the construction and insertion of foreign objects in the natural environment. Although the land depicted has already been altered through years of cleating and grazing practices, these works metaphorically signal that the continued ‘leak’ of residential development into both remnant bushland and farmland owned by generations of families is an unwelcome accident or breach that threatens to overturn the ecological balance between nature and culture.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work Aristide (2010, C Type photograph, Collection of the University of Queensland) from the series leak

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Landscape changes; its restless. It moves with the wind and rhymes with the seasons. It burns and floods. It is spatial, offering the visitor several perspectives that can be contradictory, paradoxical and durational. Landscape is also a ‘situation’, a complex interplay of historical and environmental conditions. Landscape has a past, present and future; it is never the same as it used to be. When we gaze out over a bay, or ponder and Indigenous site, we can’t help but wonder what it used to look like, how it used to be occupied, what tragedies and serendipities happened there. Landscape can be both a place of belonging and a destination, and depending on one’s perspective, it can embody the familiarity of home and the promise of adventure; the discomfort of displacement or the tragedy of invasion. Landscape is formed as much by natural forces as it is by human knowledge. …

Rosemary Laing introduces us to these histories by creating projects in the Australian landscape. These projects are sustained by her continuing search for understanding the multiple attitudes to belonging in the landscape. Miwon Kwon has argued that today ‘feeling out of place is the cultural symptom of late capitalism’s political and social reality’, so much so, that to be ‘situated’ is to be ‘displaced’. In Australia, the notion of displacement has a history that goes back to colonisation. Questions of who owns the land, how we inhabit it, and who feels displaced, are an intrinsic part of the Australian consciousness. Laing’s work also asks how we encounter the landscape; who or what is out of place; who or what does not belong; are ‘we’ the alien? …

Laing choreographs situations in the landscape, invoking a unique set of circumstances that reflect upon historic, social, environmental and material conditions…

Doherty argues that rather than being site specific, art has shifted from a fixed location, to one that, in the words of Kwon, is ‘constituted through social, economic, cultural and economic processes’. Such artworks are not located in a single place, but rather take the form of interactive activities, collective actions, and spatial experiences. They are constitutive rather than absolute; propositional rather than conclusive. Rosemary Laing’s mise-en-scènes are not public, events or performances, but they forge a compositional dialogue with the natural environment that provokes a social, economic and environmental conscience.

Laing’s photographs are conceived in series, so that each photograph is part of a larger cluster of images that are often arrange in specific sequences. Moreover, the spatial tableaux and the photographic outcome have an intrinsic connection. The installations cannot be seen without the photographic apparatus and yet each mise-en-scène is presented from a variety of perspectives and angles, so that we cannot necessarily rely on the photographic outcome to be ‘truthful’. The photograph is not simply documentation. It is an activator. In many respects Laing places us in the landscape, so that we fell part of the image. She does this through both the size and relative height of the image, along with the point of view and our relation with the horizon line. Laing tests the limits of the photograph, and also provokes the viewer to rearticulate their connection to landscape, and re-energise it. She comes to be the interlocutor between the histories and meanings embedded in landscape, the installation, the photograph and the viewer.

Victoria Lynn. “Rosemary Laing – Co-belonging with the Landscape,” in Rosemary Laing exhibition catalogue, TarraWarra Art Museum, 2017, pp. 7-9.

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work effort and rush #9 (swanfires) (2013-2015, C Type photograph, Collection of Alex Cleary) from the series effort and rush

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Detail of Rosemary Laing’s work effort and rush #9 (swanfires) (2013-2015)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work burning Ayer #12 (2003, C Type photograph, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney) from the series one dozen unnatural disasters in the Australian landscape

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

The fire in burning Ayer #12 gives us some clues to the relationship between fire and the artist’s quest to reimagine belonging in the Australian landscape. The earth-encrusted items of mass-produced domestic wooden furniture – a reference, once more, to the idea of ‘housing’, home and belonging. Their ashes fold back into the earth. The strength of the red desert plain holds its ground, as it were, as the stage for this enactment of both sacrifice and return. Fire comes to be a metaphor for the ways in which the Indigenous landscape refuses our presence and escapes from our control.

In effort and rush #9 (swanfires), the blur of movement across tall thin tree trunks, captured in a smoky black hue, considers both the rush of the fire, and the rush of escape. It is as if the camera has become a paintbrush.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work swanfires, Chris’s shed (2002-2004, C Type photograph, Monash Gallery of Art) from the series swanfires

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Detail of Rosemary Laing’s work swanfires, Chris’s shed (2002-2004)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work How we lost poor Flossie (fires) (1988, Gelatin silver photograph, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide) from the series Natural Disasters

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

When Laing first tackled disasters in her 1988 Natural Disasters series, it was from the point of view of the media phenomenon. Slicing together imagery from media coverage of the Ash Wednesday fires, the series, including works such as How we lost poor Flossie (fires) was more to do with the slipstream of spectacle in the wake of the bicentennial of Australia. At the time, competing propositions about our cultural identity jostled for attention: 200 years of settlement, Aboriginal calls for recognition, the tourist panorama, and the sensationalism of fire in the landscape.

After every significant fire near her house in Swanhaven, on the south cost of New South Wales, Laing takes photographs in the aftermath of the blaze, like a marker of the irreconcilable yet continuing presence of natural and unnatural disasters.

In the series swanfires there is an overwhelming sense of loss. These two images speak of the abject disaster of fire, before the clean up. They depict situations that exceed our comprehension. In swanfires, John and Kathy’s auto services, the intersecting forms of corrugated iron – the quintessential material of rural Australia – are unexpectedly bathed in the softest of pink, their forms reflecting the tree line behind.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of Rosemary Laing’s work swanfires, John and Kathy’s auto services (2002-2004, C Type photograph,Courtesy of the artist and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne) from the series swanfires (see below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosemary Laing (Australian, b. 1959)

swanfires, John and Kathy’s auto services

2002-2004

From the series swanfires

C Type photograph

85 x 151cm

Courtesy the artist and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

© Rosemary Laing, Courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

TarraWarra Museum of Art will stage an exhibition of the works of Rosemary Laing, one of Australia’s most significant and internationally-renowned photo-based artists, 2 December 2017 – 11 February 2018.

Focusing on the theme of land and landscape in Laing’s oeuvre, the Rosemary Laing exhibition includes 28 large scale works selected from 10 series over a thirty-year period. The exhibition, which is the first large-scale showing of Laing’s work in Victoria, will be accompanied by an exhibition of works by Fred Williams focusing on a single year of the artist’s oeuvre, Fred Williams – 1974. Curated by Anthony Fitzpatrick, the Williams exhibition reveals the ways in which colour and human intervention in the landscape became a focus for the artist.

Born in Brisbane and based in Sydney, Laing has worked with the photographic medium since the mid-1980s. Her projects have engaged with culturally and historically resonant sites in the Australian landscape, as well as choreographed performances. TarraWarra director, Victoria Lynn, curator of the exhibition, says Laing’s work is highly representative of the Museum’s central interest in the exchange between art, place and ideas.

“This exhibition reveals Laing’s compositional and technical ingenuity. It shows that Laing can create images of dazzling luminosity as well as solemnly subdued light. Flickers of bright red catch our eye, while passages of verdant greens create an all-over intensity. Her images take us to open and infinite plains as well as the depths of entangled forest trails.

“The artist builds structures and installations in coastal, farming, forest and desert landscapes from which she then creates photographic images. Whether it is papering the floor of a forest in the 2013 series The Paper, or creating a river of clothes displacing the water of a flowing creek in the new series Buddens 2017, Laing’s images reflect upon the historical and contemporary stories of human engagement with our continent. More specifically, the artist draws on colonisation and the impact of waves of asylum seekers, suggesting that the landscape is forever transformed both physically and metaphorically. The exhibition also includes works depicting the aftermath of fire, and the ways it too transforms what we thought we knew of the landscape,” Ms Lynn said.

Rosemary Laing comments: “The arrival of people, throughout history, shifts what happens in land, challenging those who have left their elsewhere, and disrupting the continuum of their destination-place. A disruption causes a reconfiguration. It elaborates both the beforehand and the afterward. The works are somewhere between – a narrative for the movement of people, the condition of landforms with a changing peopled condition, expectations of home and haven, flow and flooding, and the effect and affect of these passages.” The exhibition is supported by major exhibition partner the Balnaves Foundation, and will be accompanied by a catalogue authored by Judy Annear, funded by the Gordon Darling Foundation.

Annear, writes: “How to make sense of what humanity does in and to their environment regardless of whether that environment appears to be natural or made? What is the spectrum, the temperature of that activity? Laing is an artist who grapples with these questions and how to reflect and interpret the times in which she lives.”

Neil Balnaves AO, Founder The Balnaves Foundation said, “The exhibitions Rosemary Laing and Fred Williams – 1974 will be the third year that The Balnaves Foundation have supported the TarraWarra Museum of Art to deliver exhibitions of note by Australian artists. The Foundation is proud to partner in these major endeavours, providing vital opportunities for important Australian artists to be showcased, whilst providing art lovers – including inner-regional audiences – access to outstanding arts experiences.”

Laing has exhibited in Australia and abroad since the late 1980s. She has participated in various international biennials, including the Biennale of Sydney (2008), Venice Biennale (2007), Busan Biennale (2004), and Istanbul Biennial (1995). Her work is present in museums Australia-wide and international museums including: the Museo Nacional Centro De Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, USA; 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan; Kunstmuseum Luzern, Lucerne, Switzerland; Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

Laing has presented solo exhibitions at several museums, including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; Kunsthallen Brandts Klædefabrik, Odense; Domus Artium 2002, Salamanca; Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville; and National Museum of Art, Osaka. A monograph, written by Abigail Solomon-Godeau has been published by Prestel, New York (2012).

Press release from the TarraWarra Museum of Art

Rosemary Laing (Australian, 1959-2024)

brumby mound #6

2003

From the series one dozen unnatural disasters in the Australian landscape

C Type photograph

109.9 x 225cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds from the Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2004

© Rosemary Laing, Courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Rosemary Laing (Australian, b. 1959)

The Paper, Tuesday

2013

From the series The Paper

C Type photograph

90 x 189cm

Monash University Collection

Purchased by the Faculty of Science, 2015

Courtesy of Monash University Museum of Art

© Rosemary Laing, Courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Rosemary Laing (Australian, b. 1959)

Aristide

2010

From the series leak

C Type photograph

110 x 223cm

The University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane

Collection of The University of Queensland, purchased 2011

© Rosemary Laing, Courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Rosemary Laing (Australian, 1959-2024)

Walter Hood

2017

From the series Buddens

Archival pigment print

100 x 200.6cm

Courtesy the artist and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

© Rosemary Laing, Courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Rosemary Laing (Australian, 1959-2024)

The Flowering of the Strange Orchid

2017

From the series Buddens

Archival pigment print

100 x 200cm

Ten Cubed Collection, Melbourne

© Rosemary Laing, Courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Rosemary Laing (Australian, 1959-2024)

Drapery and wattle

2017

From the series Buddens

Archival pigment print

100 x 152.6cm

Collection of Sally Dan-Cuthbert Art Consultant

© Rosemary Laing, Courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

TarraWarra Museum of Art

311 Healesville-Yarra Glen Road,

Healesville, Victoria, Australia

Melway reference: 277 B2

Phone: +61 (0)3 5957 3100

Opening hours:

Open Tuesday – Sunday, 11am – 5pm

Open all public holidays except Christmas day

Summer Season – open 7 days

Open 7 days per week from Boxing Day to the Australia Day public holiday

TarraWarra Museum of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.