Exhibition dates: 28th April – 28th August 2011

Many thankx to The Arts Décoratifs Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the images for a larger version of the image.

Mercedes Benz SSK “Count Trossi”

1930

Ralph Lauren collection

© Photo Michael Furman

The notion of line in a car echoes that of the perfectly harmonious line of trajectory. The design is never far from this line, even in those coachworks designed without drawing boards, of which some of the most marvellous examples are seen here. It is interesting to see that in the French language at least, cars have taken on board the concept of ligne (or “line”), a word with many meanings. Yet the term ligne, taken in the sense that it is used nowadays in reference to coachwork, is classified by French lexicographer Littré within the sphere of fine art, and defined by him as: “the general effect produced by the coming together and combination of different parties of either a natural object or a composition.” The natural development of language thus shows us the relationship between cars and fine art.

Excerpt from the catalog, Editions Les Arts Décoratifs, Paris 2011

In 1970, Les Arts Décoratifs presented a selection of competition cars, “Bolides Design.” To compile the exhibition, a special jury was assembled, featuring designers Joe Colombo, Roger Tallon and Pio Manzu, and the artists Jean-Paul Riopelle, Jean Tinguely and Victor Vasarely, as well as Robert Delpire and François Mathey. The jury chose the models with the idea of the car as a design object, a work of art, showing that “art and technique, each at their own level, are the expression of man and his relationship with design.”

The Ralph Lauren collection can be seen from the same perspective. Patiently assembled over several decades by the fashion designer in a quest for speed and performance, it includes some of the most extraordinary jewels in the crown of European automobile history, with beauty as its common denominator.

Within the collection are some of the most elegant and innovative cars in automotive history, from the “Blower” Bentley (1929), the Ferrari 250 GTO (1962), the famous Mercedes 300 SL (1955) and the unforgettable Jaguar “D type,” whose shark fin blazed a triumphant trail at Le Mans in 1955, 1956 and 1957. But the grand tourer, the Bugatti Atlantic (1938) of which only four models were produced, represents the ultimate in luxury while showcasing the evolution of styles and techniques on the road. Each of these exceptional vehicles was designed as a masterpiece blending technological innovation and boldness of style.

For its first presentation in Europe, the Ralph Lauren collection will be put on display by Jean-Michel Wilmotte, who has opted for an intimate visual approach as these vehicles stand out both for their overall design and detail, as well as for bodywork, chassis and engines.

The kinetic and sound of the vehicles will be reproduced by means of several films and recordings. A seminar on automobile design will also be held during the exhibition.

Press release from The Arts Décoratifs Museum website

Mercedes Benz SSK “Count Trossi”

1930

Ralph Lauren collection

© Photo Michael Furman

Chassis number SSK 36038, currently owned by Ralph Lauren, remained unsold by the Mercedes-Benz factory in 1928, but was then sent out to Japan in 1930, before being brought back to Europe. This car was put together by the young British coach builder, Willy White, based on a design suggested by its aristocratic owner-cum-industrialist, Count Carlo Felice Trossi, himself a racing driver. The SSK, the archetypal Mercedes of the 1920s, built on a short chassis, is dominated by a colossal hood with a trio of exhaust pipes emerging from each side – a hood encompassing over half the car’s length with a radiator projecting out front as a windbreak. Its flamboyant rear end, dramatically tapered, adds a touch of civility to this extraordinary model, contrasting with the hieratic image of its front end. The supercharging gives the Mercedes SSK its fiery temperament, as well as the legendary noise of its seven litre straight 6 cylinder engine producing 300 CV and enabling a flat-out speed of 235kph!

Bugatti 57 SC Atlantic

1938

Collection Ralph Lauren

© Photo Michael Furman

According to Paul Bracq, “the Atlantic is a monument in the history of French coach building! More than any other car, it expresses a French-Italian look. An incredible sense of lightness is given off by this sculpture.” Powered by a straight 8 cylinder engine fitted with twin overhead camshafts and a compressor, this beauty is also incredibly fast, capable of reaching 200 kph. As the aluminium alloy used for the coachwork did not lend itself to shaping and soldering, Jean Bugatti was obliged to make the wings and roof in two parts and then assemble them with rivets. His talent lay precisely in the art of transforming this inconvenient technique into a stylistic advantage. Power and speed are suggested by the doors which are cut out of the roof and the ellipsoidal windows reminiscent of airplanes. Chassis number 57591 was the last of the four examples originally produced, a masterpiece embodying sport and luxury at their height – in short, the automobile exception.

Alfa Romeo 8C 2900 Mille Miglia

1938

Collection Ralph Lauren

© Photo Michael Furman

This racing model fitted out with a straight 8 cylinder 2.9 litre engine with twin overhead camshafts supercharged by two compressors is equipped with fully independent suspension and a four speed rear transaxle. The whole thing is perfectly balanced, resulting in the most extraordinary roadholding. The hydraulic brakes are an additional bonus, enabling it to outclass its rivals at over 185 kph. The Turin factory called upon Carrozzeria Touring to design a small series of four two-seater roadsters intended to take part in the 1938 Mille Miglia, the first example of which is the car exhibited here. Driven by the Pintacuda-Mambelli team, the car came in an incredible second under the number 142. The tear drop shaped wings add the final touch to this extraordinary car which is considered to be one of the most prestigious pre-War Grand Touring Alfa Romeos.

Ferrari 375 Plus

1954

Collection Ralph Lauren

© Photo Michael Furman

The Ferrari known as the 375 Plus was an extrapolation of the Type 375 MM, a model powered by a V12 engine with three carburettors, a gearbox with four speeds plus reverse that increased its engine size to nearly 5 litres, giving it more power and enabling it to reach 340 CV, and attain 250 kph. Because Ferrari did not have its own design department, the 375 Plus, an absolute masterpiece, was created by highly qualified, talented artisans under the guidance of Pinin Farina, Ferrari’s official coach builder. Only five examples of the Type 375 Plus were made, including a spyder version which won the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1954. Ralph Lauren’s car, chassis number 0398 AM – the last of the series – left the factory in 1954 and had a relatively illustrious career in Argentina, often driven by Valiente.

Jaguar XKD

1955

Collection Ralph Lauren

© Photo Michael Furman

In order to find a worthy successor to the brilliant Jaguar Type XKC, winner on two occasions of the Le Mans 24 Hours, the aeronautic aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer came up with a non-conformist vehicle. The D-Type has a long hood with no radiator grille, opening away from the block and a slender, extremely graceful rear, easily recognisable thanks to the highly original fin that extends the driver’s head-rest, providing greater stability at high speeds. With the classic straight 6 cylinder 3.4 litre engine, the D-Type, built on a monocoque structure, also has disk brakes. The “long-nosed” version (only 10 examples of which left the factory, including Ralph Lauren’s 505/601) gained an additional 15 kph at maximum speed, pushing it to 260 kph. No other car from the 1950s embodies speed better than this Jaguar D, with three consecutive victories in the Le Mans 24 Hours between 1955 and 1957 and another at Nurburgring in 1956. It was the most successful racing car of its generation.

Jaguar XKSS

1958

Collection Ralph Lauren

© Photo Michael Furman

Following on from Jaguar’s magnificent victories in the 1955 and 1956 Le Mans 24 Hours, demand from its enthusiastic clients was such that the company decided to make a road version of the XKD (straight 6 cylinder 3.4 litre engine with a 250 CV output capable of propelling the car to nearly 250 kph) which was named the XKSS. Principally aimed at the American market, it differed from the racing model in having a windscreen, a convertible roof, bumpers and a more civilised interior, and the famous fin was removed. Only 16 examples were constructed between January and February 1957, and a further two examples of the D-Type were transformed by the factory in 1958. Ralph Lauren’s car is one of these, created from the XKD 533 in 1956. It participated in the Six Heures du Forez in 1957, driven by Monnoyeur and Dupuy, finishing 7th, behind a fleet of Jaguar Ds which took the three first places.

Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa

1958

Collection Ralph Lauren

© Photo Michael Furman

The 250 Testa Rossa (red head) owes its name to the red camshaft covers of its V12 3 litre engine. Made by Carrozzeria Scaglietti, adapted from a design by Pinin Farina introducing a torpedo shaped body, the car had a headrest that stuck out above the bodywork and integrated headlights behind protruding Plexiglas protection. The very particular line of this vehicle proved to be primarily functional, rather than aesthetic. Indeed, the originality of the pontoon fenders enabled the wheels to remain partially uncovered, to allow for a sufficient supply of cold air to the drum brakes. Equipped with a light body that allowed it to attain 270 kph, its 300 CV engine carried it to victory on numerous occasions, including in the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1958, 1960 and 1961. Ralph Lauren’s car is the 14th of 34 similar examples produced by Ferrari.

Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta SWB

1960

Collection Ralph Lauren

© Photo Michael Furman

While the name 250 GT appeared in the Maranello catalog in 1955, the 1959 Paris Motor Show presented a short chassis Berlinetta version, with a wheelbase 20 cms shorter than other versions of the line – a thoroughbred equipped for the road, with aluminium coachwork designed by Pinin Farina and made in the Scaglietti workshops in Modena. Compared to the grand tourer version, intended for road use, the racing version was devoid of all luxury interior trimmings and bumpers, but equipped with disk brakes and a 280 CV engine that enabled this flagship model to masterfully dominate the legendary Tour de France automobile for three consecutive seasons (1960-1962) and the GT category of the Le Mans 24 Hours. Its sensual line, unequalled handling and performance (250kph), and list of victories, all combined to make the short chassis 250 GT Berlinetta one of Ferrari’s most popular models. Ralph Lauren’s car was the 31st example to leave the factory out of the 165 produced.

Ferrari 250 GTO

1962

Collection Ralph Lauren

© Photo Michael Furman

Designed in the utmost secrecy, the 250 GTO is considered by aficionados today to be the quintessential vintage Ferrari model, both technically and aesthetically, embodying one of the most famous and most expensive sports cars of all time. This Grand Tourer, of which only 39 examples were produced, clocked up an impressive list of victories, including the International Championship for GT Manufacturers in 1962, 1963 and 1964, thanks to its V12 300 CV engine situated up front, but also because of the lightness of its aluminium body, enabling it to attain 280 kph flat out! With its Scaglietti coachwork and its long hood, stocky cockpit and truncated rear, it symbolised the Grand Tourer par excellence. Ralph Lauren’s car was the 21st out of 36 Series I GTOs produced, and won many races driven by Pedro and Ricardo Rodriguez, Roger Penske, Augie Pabst and Richie Ginther.

The Arts Décoratifs Museum

107 rue de Rivoli

75001 Paris

Phone: +33 01 44 55 57 50

Open Tuesday to Sunday 11am – 6pm

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall (A-Bomb Dome)] October 24, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall (A-Bomb Dome)]' October 24, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/3-hgz-2006_1_33-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[View of burned-over area with Hiroshima Kirin Beer Hall at far right]' October 16, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[View of burned-over area with Hiroshima Kirin Beer Hall at far right]' October 16, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/view-of-burned-over-area-with-hiroshima-kirin-beer-hall.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Shima Surgical Hospital, Hiroshima]' October 24, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Shima Surgical Hospital, Hiroshima]' October 24, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/ruins-of-shima-surgical-hospital.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Group of people near damaged trolley cars, Hiroshima]' October 31, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Group of people near damaged trolley cars, Hiroshima]' October 31, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/group-of-people-near-damaged-trolley-cars.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Distorted steel-frame structure of Odamasa Store, Hiroshima] November 20, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Distorted steel-frame structure of Odamasa Store, Hiroshima]' November 20, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/1-hgz-2006_1_68-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Reinforced-concrete fire shutter in cast wall of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' November 15, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Reinforced-concrete fire shutter in cast wall of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' November 15, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/reinforced-concrete-fire-shutter-in-cast-wall-of-yasuda-life-insurance-company.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Ruins of Chugoku Coal Distribution Company or Hiroshima Gas Company] November 8, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Chugoku Coal Distribution Company or Hiroshima Gas Company]' November 8, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/7-hgz-035_hiroshima-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Remains of a school building] November 17, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Remains of a school building]' November 17, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/6-hgz-065_hiroshima-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. ["Shadow" of a hand valve wheel on the painted wall of a gas storage tank; radiant heat instantly burned paint where the heat rays were not obstructed, Hiroshima] October 14 - November 26, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '["Shadow" of a hand valve wheel on the painted wall of a gas storage tank; radiant heat instantly burned paint where the heat rays were not obstructed, Hiroshima]' October 14 - November 26, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/4-hgz-2006_1_431-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Interior of Hiroshima City Hall auditorium with undamaged walls and framing but spalling of plaster and complete destruction of contents by fire] November 1, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Interior of Hiroshima City Hall auditorium with undamaged walls and framing but spalling of plaster and complete destruction of contents by fire]' November 1, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/8-hgz-031_hiroshima-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Sumitomo Fire Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' October 24, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Sumitomo Fire Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' October 24, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/ruins-of-sumitomo-fire-insurance-company.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Rooftop view of atomic destruction, looking southwest, Hiroshima] October 31, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Rooftop view of atomic destruction, looking southwest, Hiroshima]' October 31, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/10-hgz-006_hiroshima-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Burned-over landscape north of ground zero in the vicinity of Hiroshima Castle]' October 31, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Burned-over landscape north of ground zero in the vicinity of Hiroshima Castle]' October 31, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/burned-over-landscape-north-of-ground-zero-in-the-vicinity-of-hiroshima-castle.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Interior with heavy spalling of cement plaster by fire in combustiible floor of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' November 1, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Interior with heavy spalling of cement plaster by fire in combustiible floor of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' November 1, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/interior-with-heavy-spalling-of-cement-plaster.jpg)

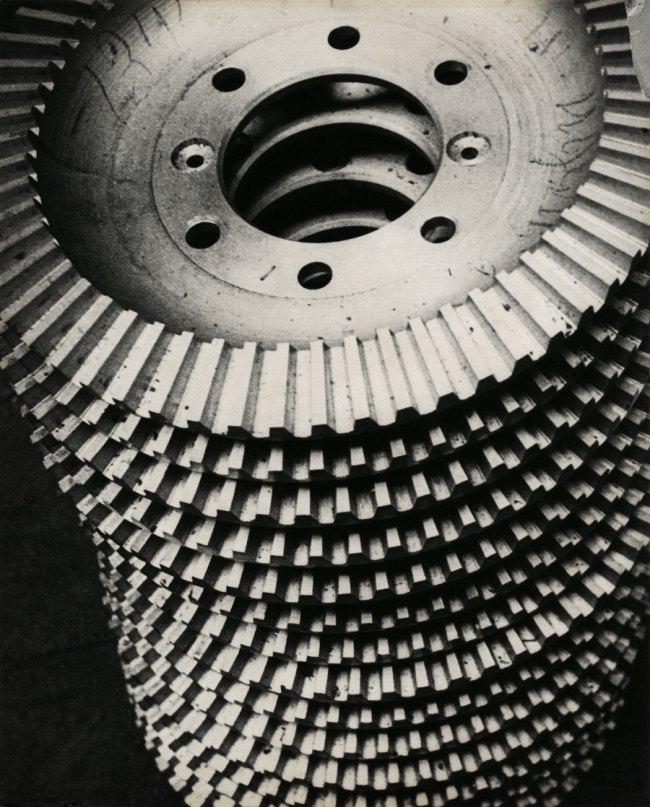

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Damaged turbo-generator and electrical panel of Chugoku Electric Company, Minami Sendamachi Substation, Hiroshima]' November 18, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Damaged turbo-generator and electrical panel of Chugoku Electric Company, Minami Sendamachi Substation, Hiroshima]' November 18, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/damaged-turbo-generator-and-electrical-panel.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Steel stairs warped by intense heat from burned book stacks of Asano Library, Hiroshima]' November 15, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Steel stairs warped by intense heat from burned book stacks of Asano Library, Hiroshima]' November 15, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/11-hgz-193_hiroshima-web.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.