Exhibition dates: 20th May – 28th August, 2011

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall (A-Bomb Dome)]

October 24, 1945

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

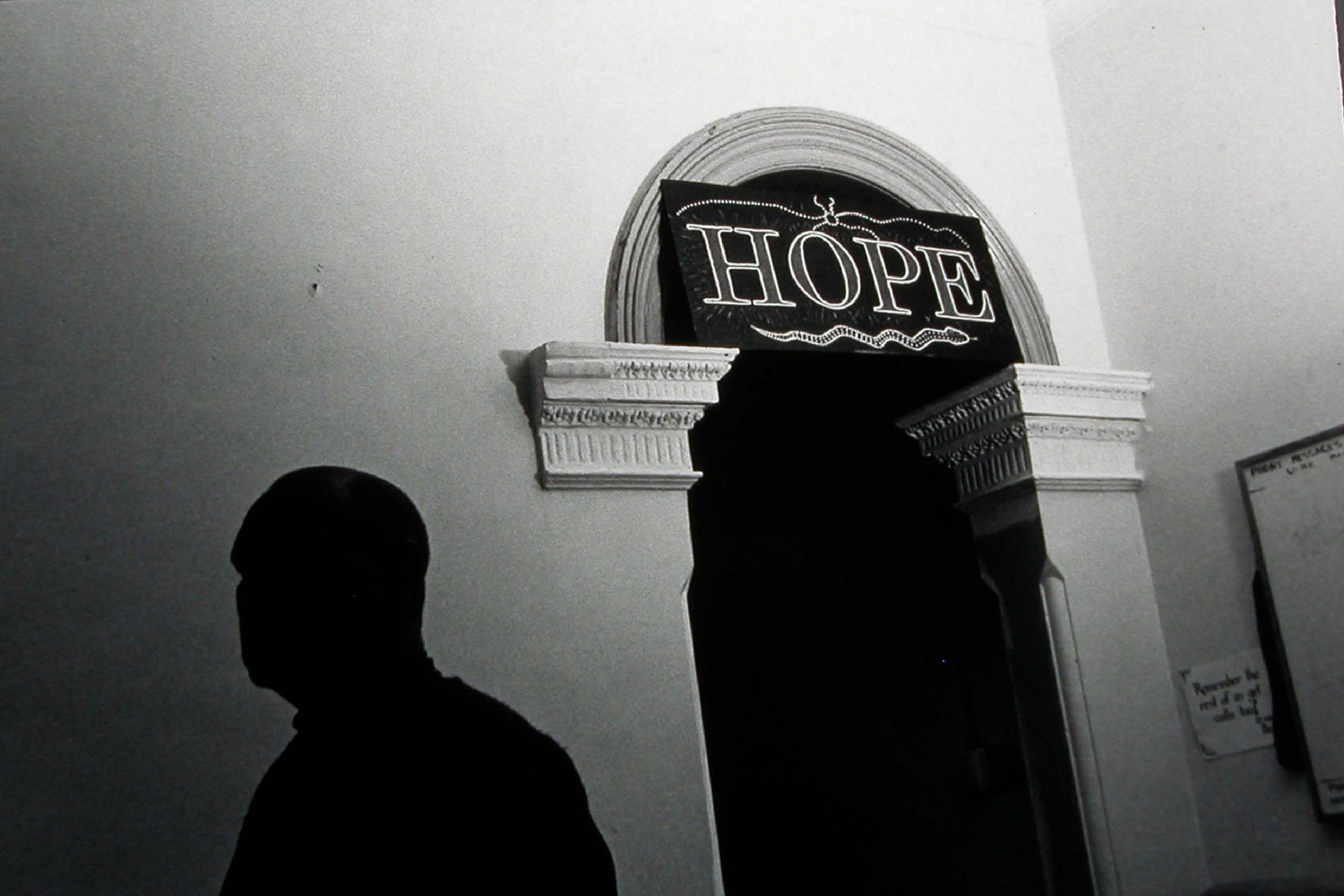

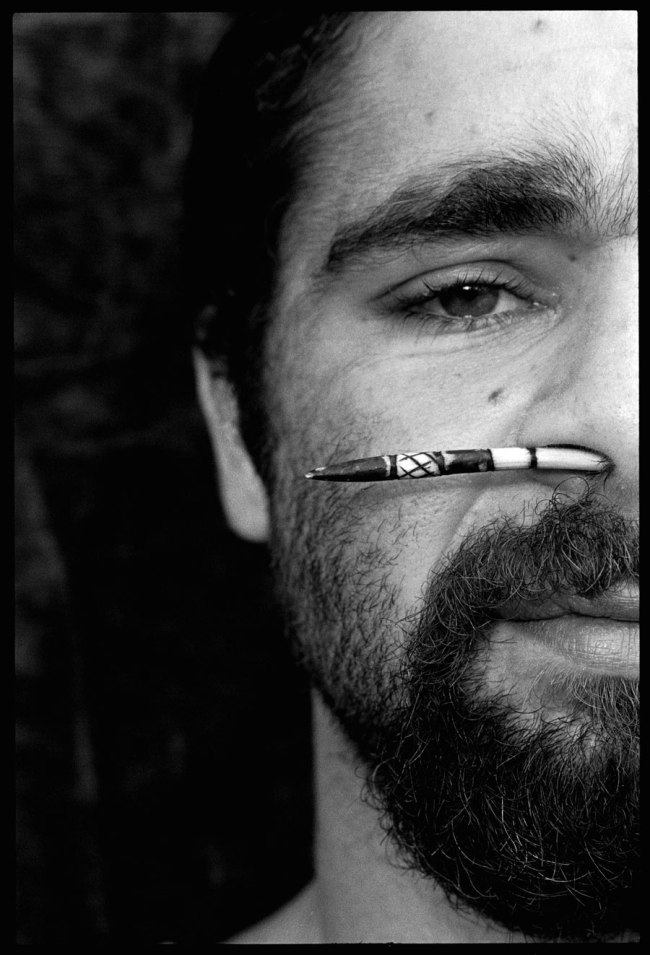

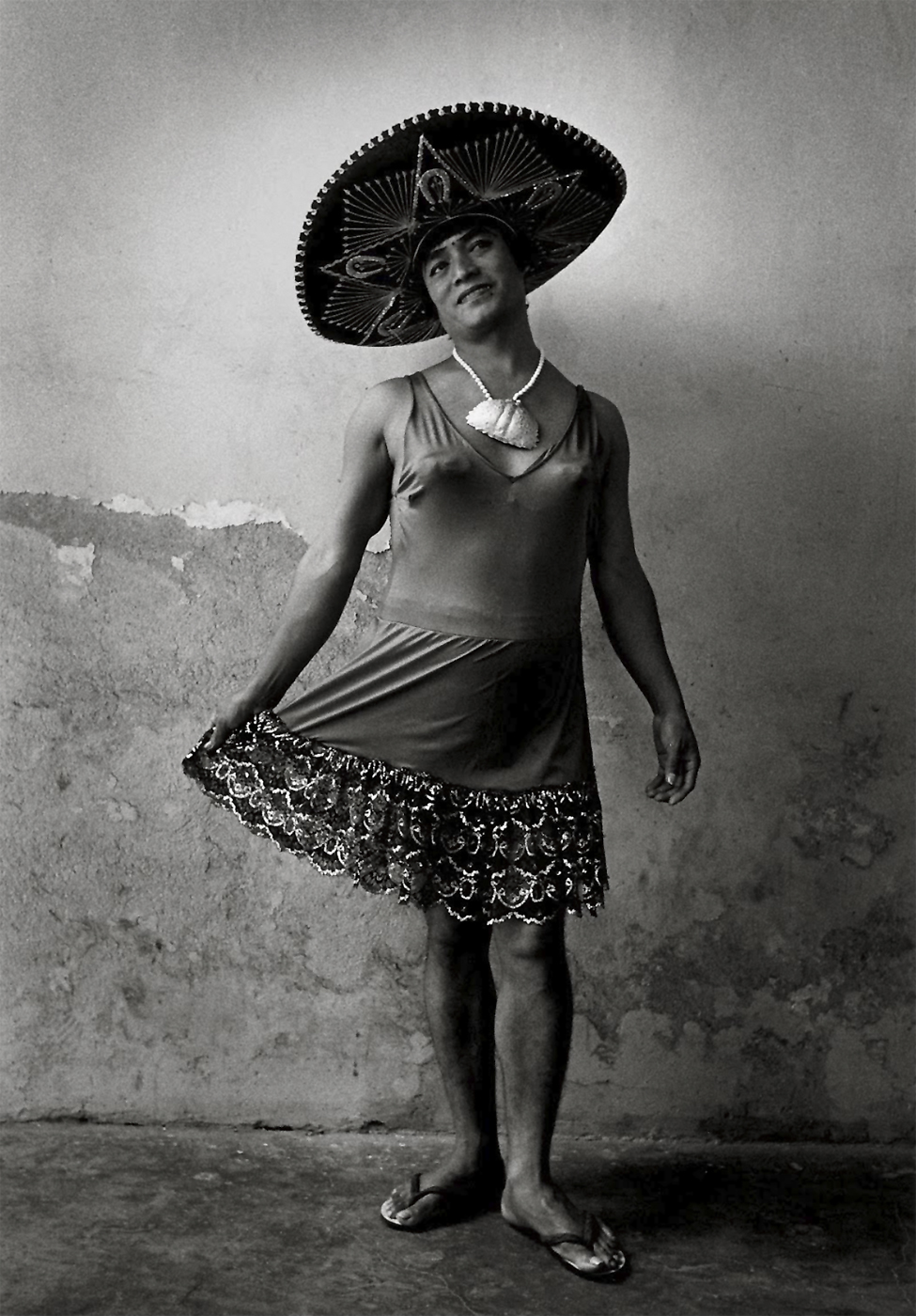

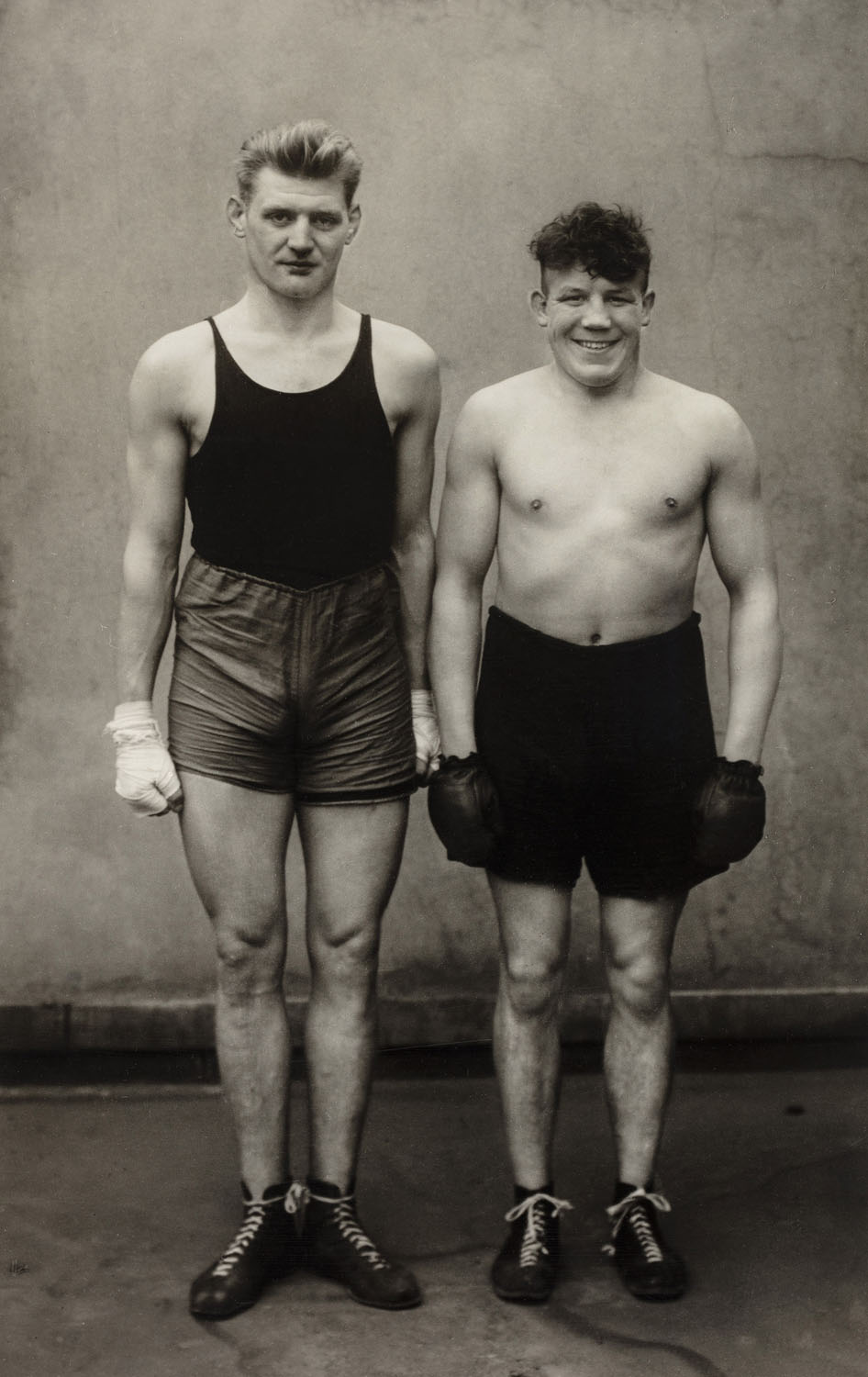

The “United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division”. Don’t you just love the irony in this title? The aim of the military group who took these photographs as part of a survey on “strategic bombing” of Hiroshima was to document the physical damage that took place. As if an atomic bomb is anything other than destructive! As if an atomic bomb is anything other than catastrophic! As if an atomic bomb is anything less than death itself!

Upon this realisation, the father of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer, famously quoted the Bhagavad Gita after the detonation of the first bomb on July 16, 1945 in the Trinity test in New Mexico, “Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

In saying that, military jurisprudence, that disciplinary machine of death, becomes not only the recorder of destruction but also the re-ordering of the world, thus re(c)ording the world under Foucault’s Matrix of Practical Reason:

~ Through the technologies of production, which permit us to produce, transform or manipulate things

~ Through the technologies of power, which determine the conduct of individuals and submit them to certain ends or domination, an objectivising of the subject.1

In short, the military is power; the military subjugates humans; and the military destroys at will.

The strange beauty of the Physical Damage Division photographs is that they simply document what remains. Like the “shadow” of a hand valve wheel on the painted wall of a gas storage tank, Ground Zero is burnt onto the ground glass of the camera.

Like the “shadow” these events are eternally seared into the collective memory never, ever, to be forgotten.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Foucault, Michel. “Technologies of the Self,” quoted in Martin, Luther and Gutman, Huck and Hutton, Patrick (eds.,). Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. London: Tavistock Publications, 1988, p. 18

Many thankx to the International Center of Photography for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[View of burned-over area with Hiroshima Kirin Beer Hall at far right]

October 16, 1945

Gelatin silver print

3 11/16 x 4 9/16 in. (9.4 x 11.6cm)

© International Center of Photography

Purchase, with funds provided by the ICP Acquisitions Committee, 2006

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Ruins of Shima Surgical Hospital, Hiroshima]

October 24, 1945

Gelatin silver print

4 1/8 x 6 1/16 in. (10.5 x 15.4cm)

© International Center of Photography

Purchase, with funds provided by the ICP Acquisitions Committee, 2006

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Group of people near damaged trolley cars, Hiroshima]

October 31, 1945

Gelatin silver print

3 11/16 x 4 7/16 in. (9.4 x 11.3cm)

© International Center of Photography

Purchase, with funds provided by the ICP Acquisitions Committee, 2006

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Distorted steel-frame structure of Odamasa Store, Hiroshima]

November 20, 1945

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Reinforced-concrete fire shutter in cast wall of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]

November 15, 1945

Gelatin silver print

3 11/16 x 4 3/4 in. (9.4 x 12.1cm)

© International Center of Photography

Purchase, with funds provided by the ICP Acquisitions Committee, 2006

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Ruins of Chugoku Coal Distribution Company or Hiroshima Gas Company]

November 8, 1945

Gelatin silver contact print

© International Center of Photography

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Remains of a school building]

November 17, 1945

Gelatin silver contact print

© International Center of Photography

Once-classified images of atomic destruction at Hiroshima will be displayed in a new exhibition Hiroshima: Ground Zero 1945 at the International Center of Photography (1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street) from May 20 to August 28, 2011. Drawn from ICP’s permanent collection, the Hiroshima archive includes more than 700 images of absence and annihilation, which formed the basis for civil defence architecture in the United States. These images had been mislaid for over forty years before being acquired by ICP in 2006.

This exhibition will include approximately 60 contact prints and photographs as well as the secret 1947 United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) report, The Effects of the Strategic Bombing on Hiroshima, Japan. It will be accompanied by a catalogue published by ICP/Steidl, with essays by John W. Dower, Adam Harrison Levy, David Monteyne, Philomena Mariani, and Erin Barnett.

After the nuclear attacks in August 1945, President Truman dispatched members of the USSBS to Japan to survey the military, economic, and civilian damage. The Survey’s Physical Damage Division photographed, analysed, and evaluated the atomic bomb’s impact on the structures surrounding the Hiroshima blast site, designated “Ground Zero.” The findings of the USSBS provided essential information to American architects and civil engineers as they debated the merits of bomb shelters, suburbanisation, and revised construction techniques.

The photographs in this exhibition were in the possession of Robert L. Corsbie, an executive officer of the Physical Damage Division who later worked for the Atomic Energy Commission. An architectural engineer and expert on the effects of the atomic bomb, he used what he learned from the structural analyses and these images to promote civil defence architecture in the U.S. The photographs went through a series of unintended moves after Corsbie, his wife and son died in a house fire in 1967.

The U.S., at war with Japan, detonated the world’s first weaponised atomic bomb over Hiroshima, a vast port city of over 350,000 inhabitants, on August 6, 1945. The blast obliterated about 70 percent of the city and caused the deaths of more than 140,000 people. Three days later, the U.S. dropped a second nuclear bomb on Nagasaki, resulting in another 80,000 fatalities. Within a week, Japan announced its surrender to the Allied Powers, effectively ending World War II.

“Once part of a classified cache of government photographs, this archive of haunting images documents the devastating power of the atomic bomb,” said ICP Assistant Curator of Collections Erin Barnett, who organised the exhibition.

Press release from the International Center of Photography website

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[“Shadow” of a hand valve wheel on the painted wall of a gas storage tank; radiant heat instantly burned paint where the heat rays were not

obstructed, Hiroshima]

October 14 – November 26, 1945

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Interior of Hiroshima City Hall auditorium with undamaged walls and framing but spalling of plaster and complete destruction of contents by fire]

November 1, 1945

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Ruins of Sumitomo Fire Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]

October 24, 1945

Gelatin silver print

3 3/16 x 4 7/16 in. (8.1 x 11.3cm)

© International Center of Photography

Purchase, with funds provided by the ICP Acquisitions Committee, 2006

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Rooftop view of atomic destruction, looking southwest, Hiroshima]

October 31, 1945

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Burned-over landscape north of ground zero in the vicinity of Hiroshima Castle]

October 31, 1945

Gelatin silver print

3 3/4 x 4 5/8 in. (9.5 x 11.7cm)

© International Center of Photography

Purchase, with funds provided by the ICP Acquisitions Committee, 2006

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Interior with heavy spalling of cement plaster by fire in combustiible floor of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]

November 1, 1945

Gelatin silver print

3 11/16 x 4 3/4 in. (9.4 x 12.1cm)

© International Center of Photography

Purchase, with funds provided by the ICP Acquisitions Committee, 2006

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Damaged turbo-generator and electrical panel of Chugoku Electric Company, Minami Sendamachi Substation, Hiroshima]

November 18, 1945

Gelatin silver print

3 13/16 x 4 7/16 in. (9.7 x 11.3cm)

© International Center of Photography

Purchase, with funds provided by the ICP Acquisitions Committee, 2006

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division

[Steel stairs warped by intense heat from burned book stacks of Asano Library, Hiroshima]

November 15, 1945

Gelatin silver contact print

© International Center of Photography

International Center of Photography

79 Essex Street, New York, NY 10002

between Delancey Street and Broome Street

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Monday 11am – 7pm

Closed: Tuesday

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall (A-Bomb Dome)] October 24, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall (A-Bomb Dome)]' October 24, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/3-hgz-2006_1_33-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[View of burned-over area with Hiroshima Kirin Beer Hall at far right]' October 16, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[View of burned-over area with Hiroshima Kirin Beer Hall at far right]' October 16, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/view-of-burned-over-area-with-hiroshima-kirin-beer-hall.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Shima Surgical Hospital, Hiroshima]' October 24, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Shima Surgical Hospital, Hiroshima]' October 24, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/ruins-of-shima-surgical-hospital.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Group of people near damaged trolley cars, Hiroshima]' October 31, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Group of people near damaged trolley cars, Hiroshima]' October 31, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/group-of-people-near-damaged-trolley-cars.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Distorted steel-frame structure of Odamasa Store, Hiroshima] November 20, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Distorted steel-frame structure of Odamasa Store, Hiroshima]' November 20, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/1-hgz-2006_1_68-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Reinforced-concrete fire shutter in cast wall of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' November 15, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Reinforced-concrete fire shutter in cast wall of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' November 15, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/reinforced-concrete-fire-shutter-in-cast-wall-of-yasuda-life-insurance-company.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Ruins of Chugoku Coal Distribution Company or Hiroshima Gas Company] November 8, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Chugoku Coal Distribution Company or Hiroshima Gas Company]' November 8, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/7-hgz-035_hiroshima-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Remains of a school building] November 17, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Remains of a school building]' November 17, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/6-hgz-065_hiroshima-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. ["Shadow" of a hand valve wheel on the painted wall of a gas storage tank; radiant heat instantly burned paint where the heat rays were not obstructed, Hiroshima] October 14 - November 26, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '["Shadow" of a hand valve wheel on the painted wall of a gas storage tank; radiant heat instantly burned paint where the heat rays were not obstructed, Hiroshima]' October 14 - November 26, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/4-hgz-2006_1_431-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Interior of Hiroshima City Hall auditorium with undamaged walls and framing but spalling of plaster and complete destruction of contents by fire] November 1, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Interior of Hiroshima City Hall auditorium with undamaged walls and framing but spalling of plaster and complete destruction of contents by fire]' November 1, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/8-hgz-031_hiroshima-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Sumitomo Fire Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' October 24, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Ruins of Sumitomo Fire Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' October 24, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/ruins-of-sumitomo-fire-insurance-company.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. [Rooftop view of atomic destruction, looking southwest, Hiroshima] October 31, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Rooftop view of atomic destruction, looking southwest, Hiroshima]' October 31, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/10-hgz-006_hiroshima-web.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Burned-over landscape north of ground zero in the vicinity of Hiroshima Castle]' October 31, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Burned-over landscape north of ground zero in the vicinity of Hiroshima Castle]' October 31, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/burned-over-landscape-north-of-ground-zero-in-the-vicinity-of-hiroshima-castle.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Interior with heavy spalling of cement plaster by fire in combustiible floor of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' November 1, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Interior with heavy spalling of cement plaster by fire in combustiible floor of Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Hiroshima branch]' November 1, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/interior-with-heavy-spalling-of-cement-plaster.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Damaged turbo-generator and electrical panel of Chugoku Electric Company, Minami Sendamachi Substation, Hiroshima]' November 18, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Damaged turbo-generator and electrical panel of Chugoku Electric Company, Minami Sendamachi Substation, Hiroshima]' November 18, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/damaged-turbo-generator-and-electrical-panel.jpg)

![United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Steel stairs warped by intense heat from burned book stacks of Asano Library, Hiroshima]' November 15, 1945 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division. '[Steel stairs warped by intense heat from burned book stacks of Asano Library, Hiroshima]' November 15, 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/11-hgz-193_hiroshima-web.jpg?w=650&h=790)

You must be logged in to post a comment.