Exhibition dates: 18th February – 8th April 2012

Hijacked III Interview with writer Anthony Luvera

The photographs in this posting highlight the conceptual diversity in contemporary art practice and emphasise the talent of the practitioners working today. Just an observation: how serious are the portraits – it’s as if no’body’ is allowed to laugh or smile anymore. Perhaps this is a reflection of the times in which we live, full of malaise, anxiety and little wonder. Fear of being replaced, fear of discrimination, fear of growing up, fear of dying. Or dressed up in a women’s dress and pink hat, having the “courage” or ignorance (the opposite of fear?) to look like a stunned mullet with a blank expression on the face (deadpan photography that I really can’t stand). Or, perhaps, simple effacement: defiance as body becomes mannequin, body hidden behind a mask or completely cloaked from view. These grand photographs have the intensity, perhaps not a lightness of being.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to PICA for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Trish Morrissey (Irish, b. 1967)

Hayley Coles, June 17th, 2006

2006

Courtesy of the artist and Elaine Levy Project, commissioned by Impressions Gallery

Review of Trish Morrissey on Art Blart

Front deals with the notion of borders, boundaries and the edge; using the family group and the beach setting as metaphors. For this work, the artist travelled to beaches in the UK and around Melbourne. There, she approached families and groups of friends who had made temporary encampments, or marked out territories and asked if she could be part of their family temporarily. Morrissey took over the role or position of a woman within that group – usually the mother figure. The artist asked to take the place of the mother figure, and to borrow her clothes. The mother figure then took over the artist’s role and photographed her family using a 4 x 5 camera (which Morrissey had already carefully set up) under the artist’s instruction. While Morrissey, a stranger on the beach, nestled in with the mother figure’s loved ones.

These highly performative photographs are shaped by chance encounters with strangers, and by what happens when physical and psychological boundaries are crossed. Ideas around the mythological creature the ‘shape shifter’ and the cuckoo are evoked. Each piece within the series is titled by the name of the woman who the artist replaced within the group.

Text from the PICA website

Bindi Cole (Australian, b. 1975)

Ajay

2009

From the series Sistagirls

Courtesy of Nellie Castan Gallery

Review of Sistagirls on Art Blart

The term ‘Sistagirl’ is used to describe a transgender person in Tiwi Island culture. Traditionally, the term was ‘Yimpininni’. The very existence of the word provides some indication of the inclusive attitudes historically extended towards Aboriginal sexual minorities. Colonisation not only wiped out many Indigenous people, it also had an impact on Aboriginal culture and understanding of sexual and gender expression.

As many traditions were lost, this term became a thing of the past. Yimpininni were once held in high regard as the nurturers within the family unit and tribe much like the Faafafine from Samoa. As the usage of the term vanished, tribes’ attitudes toward queer Indigenous people began to resemble that of the western world and the religious right. Even today many Sistagirls are excluded from their own tribes and suffer at the hands of others.

Text from the PICA website

Maciej Dakowicz (Polish, b. 1976)

Pink Hat, 23:42. Cardiff

2006

Courtesy of the artist and Third Floor Gallery

St Mary Street is one of the main streets in central Cardiff, the capital city of Wales; a city as any other in the UK. Unassuming during the day, on weekend nights it becomes the main scene of the city night life, fuelled by alcohol and emotions. Some of Cardiff’s most popular clubs and pubs are located there or in its vicinity. The very popular Chippy Lane, with its numerous chip and kebab shops, is just a stone’s throw away. Sooner or later most party-goers end up in that area, whether looking for another drink, some food or in search of another dance floor.

Everything takes place in this public arena – from drinking, fighting, kissing to crying and sleeping. Supermen chat up Playboy Bunnies, somebody lies on the pavement taking a nap, the hungry ones finish their portions of chips and the policemen stop another argument before it turns into a fight. Nobody seems to worry about tomorrow, what matters is here and now, punctuated by another week at work, until the next weekend rolls around again.

Text from the PICA website

Laura Pannack (British, b. 1985)

Shay

2010

Courtesy of the artist

Represented by Lisa Pritchard Agency

What’s so special about this picture are the details. The tattoo – not just what it says but the way it mimics the Nike Swoosh on her shirt – and the cigarette, that although it is not in focus, one imagines has a large line of ash on it, as if time has stopped. This is echoed in the expression on her face, deep intensity and focused on something ahead although the car is obviously stationary. From a distance one could be mistaken that this is an American photograph from the 70s but on closer inspection – the piercing, the Nike Swoosh, the car door handles – one realises that this is contemporary and British. And yet of course that stare is timeless.

Harry Hardie on the Foto8 website [Online] Cited 22/03/2012 no longer available online

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin

Culture3/Sheet72/Frame3

2011

Courtesy of the artists & Paradise Row, London

HIJACKED III interview with PICA curator Leigh Robb

… Artists are notorious for their ability to hijack; meaning to stop and hold up, to seize control by use of force in order to divert or appropriate, a deliberate attempt to action a change of direction.

Hijacked III: Contemporary Photography from Australia the UK draws on the success and unique energy of Hijacked I (Australia and USA) and Hijacked II (Australia and Germany), to once again bring together two geographically distant but historically connected communities through a range of diverse photographic practices.

This exhibition will be simultaneously presented across two sites: PICA in Perth, Western Australia and QUAD Gallery in Derby, United Kingdom, and has been timed to coincide with the launch of the luscious, full colour and 420 page Hijacked III compendium, published by Big City Press. Utilising portraiture, digital collage, archival images, documentary snap shots, internet grabs and refined photographic tableaux, the 24 artists and over 120 works in this exhibition explore themes as diverse as curious weekend leisure pursuits, gender politics and displaced Indigenous culture.

Artists: Tony Albert, Warwick Baker, Broomberg & Chanarin, Natasha Caruana, Bindi Cole, Maciej Dakowicz, Christopher Day, Melinda Gibson, Toni Greaves, Petrina Hicks, Alin Huma, Seba Kurtis, David Manley, Tracey Moffatt, Trish Morrissey, Laura Pannack, Sarah Pickering, Zhao Renhui, Simon Roberts, Helen Sear, Justin Spiers, Luke Stephenson, Christian Thompson, Tereza Zelenkova, Michael Ziebarth.

Press release from PICA website

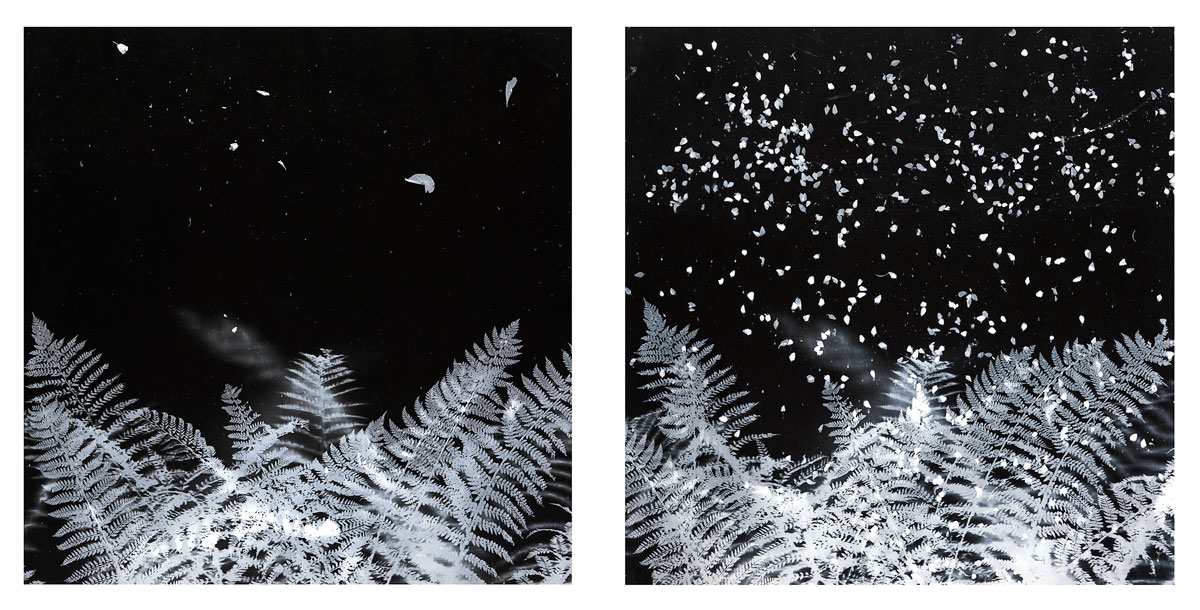

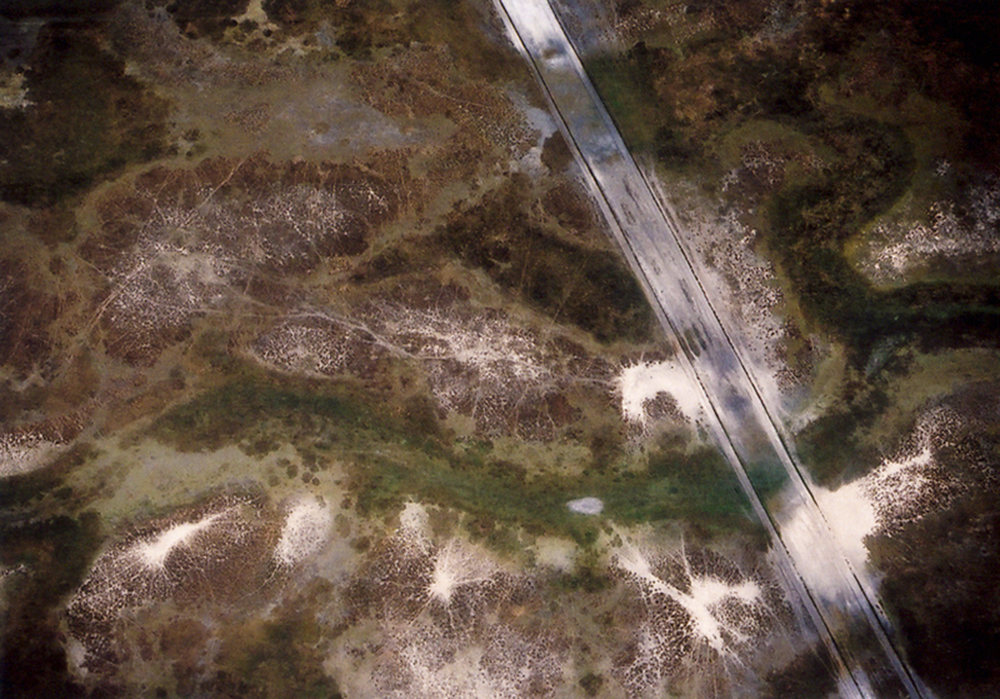

Sarah Pickering (British, b. 1972)

Land mine

2005

Courtesy of the artist and Meessen De Clercq, Brussels

The Explosion pictures document the literal theatre of war – the detailed level of artifice used to prepare men and women for combat on the front lines. They also reveal the minutiae of packaging war as entertainment. The beauty of the pictures lies in their perverse seductiveness, and this attraction underscores the distance most of us have from real combat.

Pickering’s Explosion images, by distilling an aspect of the war that is a fiction, question the reliability of seemingly objective historical accounts, such as news reports and photographs that influence how war is communicated and remembered. By extension they question how we come to know what we know about it. We learn about war from a variety of sources, from history books, first-hand accounts, news media, and movies, all of which can get confused and merged in our minds as memory.

The dual purpose of the explosives – training and re-enacting – forms a fitting parallel to how we cope with trauma, a process of both anticipation and reconciliation.”

Simon Roberts (British, b. 1974)

We English No. 56

2007

More Simon Roberts We English on Art Blart

Simon Roberts travelled across England in a motorhome between 2007 and 2008 for this portfolio of large-format tableaux photographs of the English at leisure. We English builds on his first major body of work, Motherland (2005), with the same themes of identity, memory and belonging resonating throughout. Photographing ordinary people engaged in diverse pastimes, Roberts aims to show a populace with a profound attachment to its local environment and homeland. He explores the notion that nationhood – that what it means to be English – is to be found on the surface of contemporary life, encapsulated by banal pastimes and everyday leisure activities. The resulting images are an intentionally lyrical rendering of a pastoral England, where Roberts finds beauty in the mundane and in the exploration of the relationship between people and place, and of our connections to the landscapes around us.

Text from the Simon Roberts website

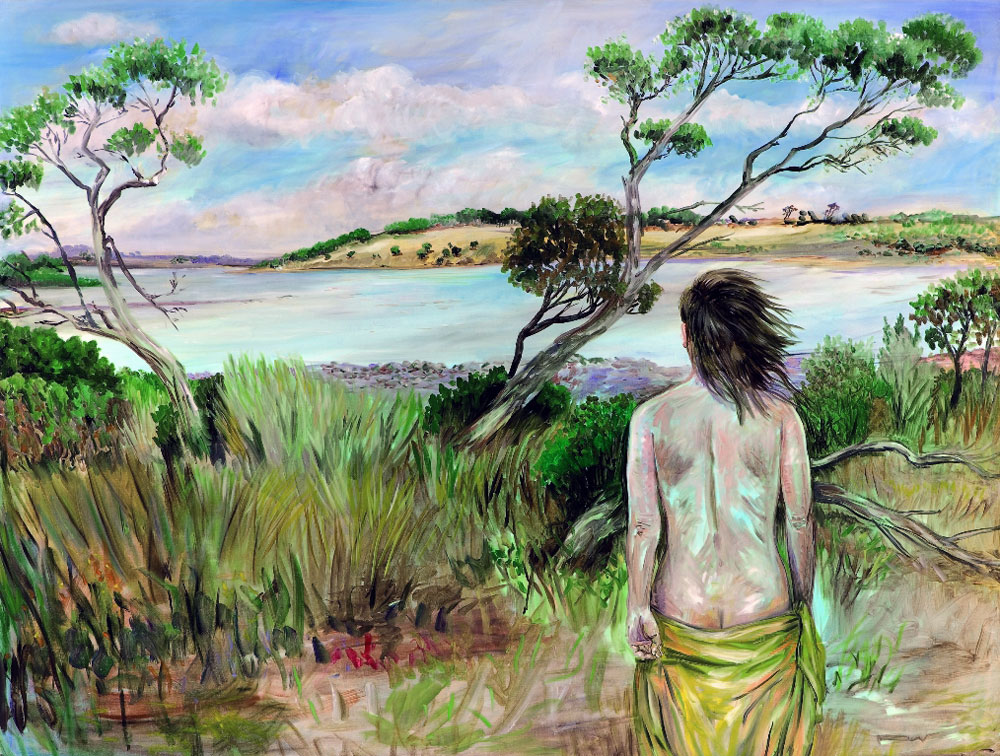

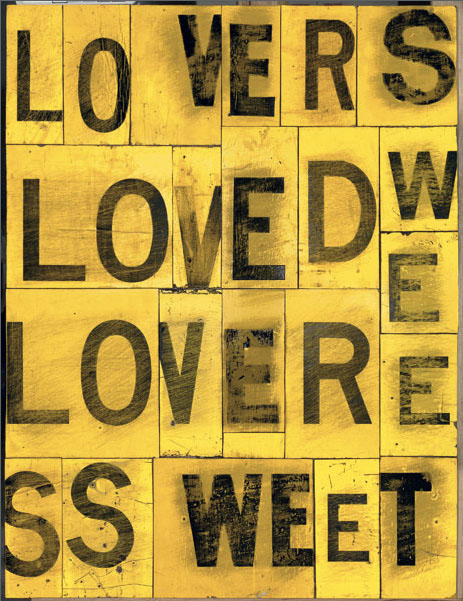

Tony Albert (Australian, b. 1981)

No Place

2009

Courtesy of the artist

Tony Albert is a Girramay rainforest man from the Cardwell area… The No Place series references The Wizard of Oz ‘there’s no place like home’. For No Place Tony returns to his tropical paradise home with a group of Lucho Libre wrestling masks from Mexico. His family adorn these masks and again become warriors protecting their paradise. These seemingly playful masks share much with Aboriginal and particularly rainforest culture. Body and shield designs from this area represent animal gods or spirit beings. The use of these masks brings a prescient new layer of armour for a new generation of warrior.

The colour scheme of solid blocks of red, black and yellow also speak to traditional rainforest aesthetics. There are strong elements of the sublime and the fantastical within these works. Viewing Aboriginal people in iconic north Queensland locations masked in Mexican wrestling paraphernalia carries more than a hint of the surreal and absurd.

Anon. “Tony Albert and No Place,” on the Big Art website, 2010 [Online] Cited 22/03/2012 no longer available online

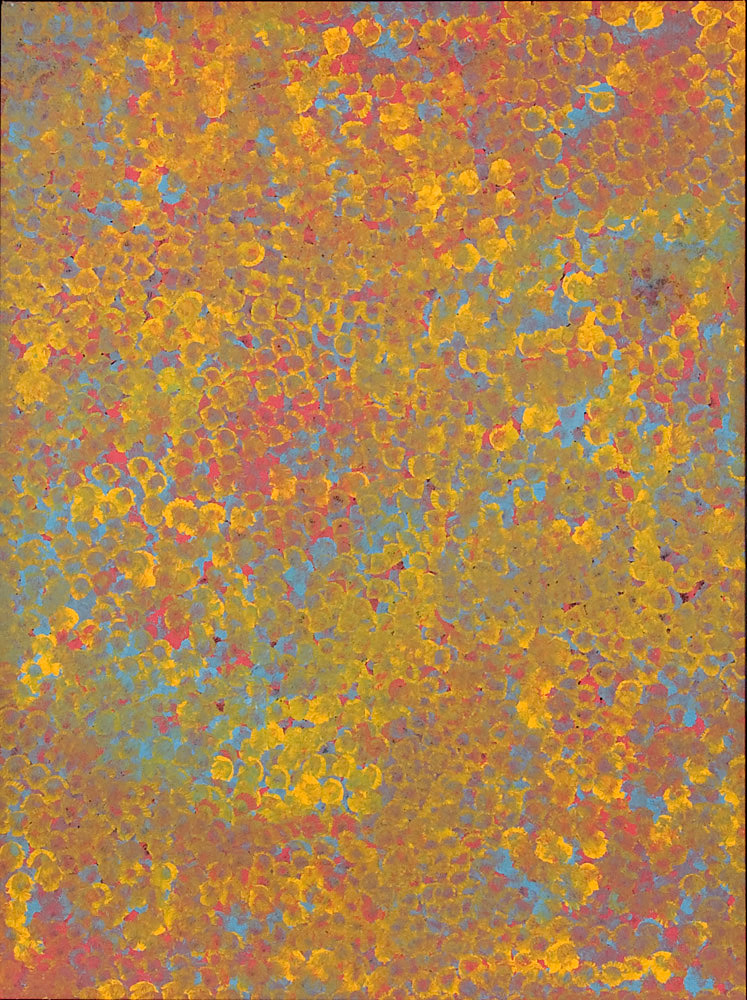

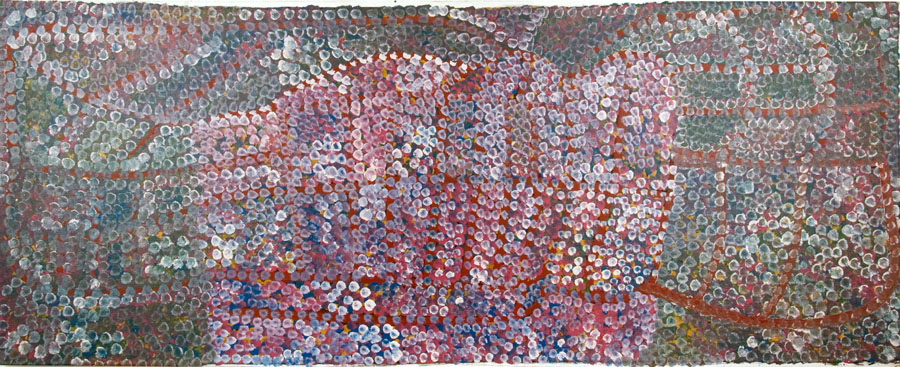

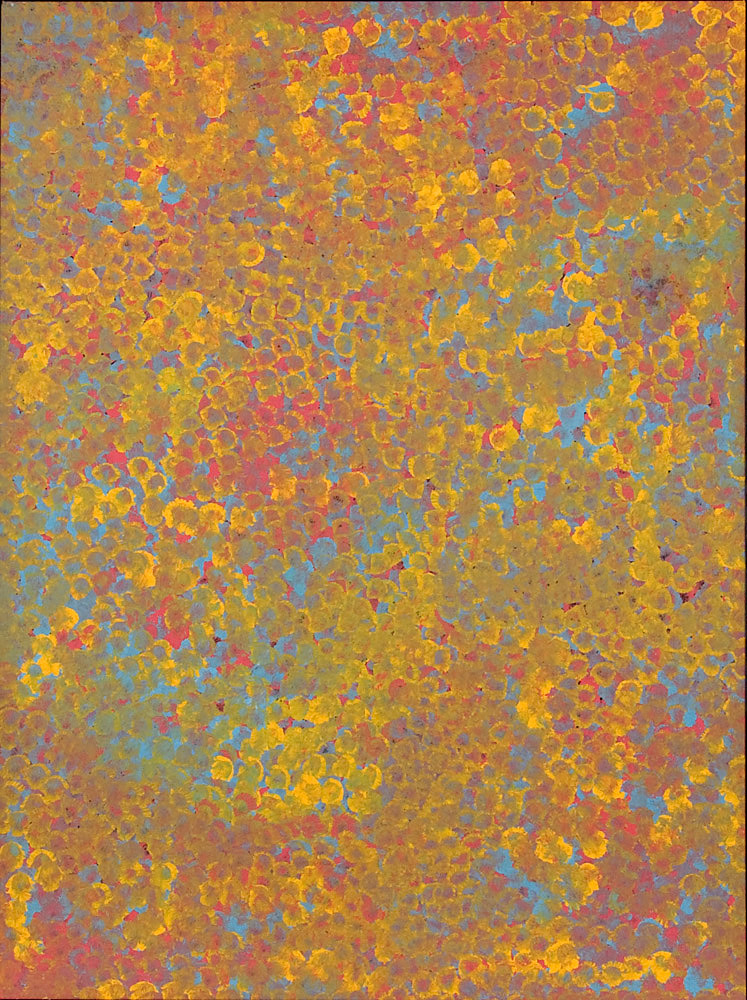

Christian Thompson (Australian / Bidjara, b. 1978)

Untitled #7 from the King Billy series

2010

Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi

King Billy, is an ode to his great great grandfather, King Billy of Bonnie Doon Lorne. The initial inspiration was a photograph of King Billy, standing alone wearing his ‘name plate’. Despite its colonial overtones, for Thompson, this image of the senior tribesman exudes wisdom and kindness and reminds him of his father. In much of Thompson’s work his processes are intuitive, he delves into a rich dream world and draws out fabulous images. He manifests his own mythological world. In this series his figures are clad in fabrics patterned with Indigenous motifs, mainly cheap hoodies in lurid colours; a modern / ancient skin for a magic youth culture. He has made a triptych, three views of a pink hooded figure spewing cascading pearl stands from the face; opulent, decadent, excessive and sensual.

Another image shows a crowned figure swathed in fabrics bearing the markings of various clans, perhaps indicating the domain of this regal form. In the hands a (poisoned?) chalice – the sawn off plastic bottle a warning about petrol sniffing? His self-portrait as psychedelic godhead/Carnaby Street dandy / flower child is spectacular and arresting. He is wearing a tailored suit, patterned with more Indigenous motifs and he cradles a bouquet. His skin is green and his eyes are purple flowers. What can this otherworldly creature tell us?

Thompson seems to emphasise a theme of disparity in this work; the ‘hoodie’ with the cascading pearls, the crown with the plastic bottle, the opulence with the desperate. These works are both beautiful and confronting.

Text from the PICA website

HIJACKED III interview with Christian Thompson

Petrina Hicks (Australian, b. 1972)

Emily the Strange

2011

Courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery

Petrina Hicks’ Beautiful Creatures appeals to our senses. Immediately alluring, the large-scale, hyper-real photographs, are all rendered so clearly and with such control they are reminiscent of advertisements. But with a series of little ruptures, within images and between them, Hicks disrupts our usually beguiled response to such artistry. For her, photography’s capability to both create and corrupt the process of seduction and consumption is of endless interest.

Hicks loads her images with history and associations but denies us a clear message. Along with the ambiguity, there is a visceral quality in these new works; her depiction of flesh, hair and veins stops the viewer short of being lulled into consumption. Hicks engages a playful yet confronting approach to confound our expectations. A cat, naked without fur, in the image Sphynx, contrasts a beautiful blonde with a face full of it in Comfort. In Emily the Strange the hairless creature reappears with a young girl whose piercing green eyes, skin-pink dress, and latent defiance, make her eerily akin to her pet. Alluded to, in the title of the exhibition, this duality is present in much of the work. Her subjects are not simply beautiful or simply creatures.

Text from the PICA website

HIJACKED III interview with photographer Petrina Hicks

Tereza Zelenkova (Czech, b. 1985)

Cadaver

2011

Courtesy of the artist

Luke Stephenson (British, b. 1983)

Diamond Sparrow #1

2009

Courtesy of the artist

Stephenson finds birds and the world surrounding them wonderfully fascinating. The birds he has photographed all belong to avid bird breeders who on the whole have been keeping birds their whole lives. It’s a hobby people generally don’t come into contact with, unless you are active within it. The artist does not keep birds but finds them beautiful in all their variations and colours, so has set out capture these birds in a way that would show them at their best.

There are many criteria to breeding a prize-winning bird, from shape and form to its pattern, and this is something Stephenson has tried to convey whilst also attempting to show some of their personalities. He set out to photograph every breed of bird within the ‘hobby’ of keeping birds but soon realised there were thousands of variations, so decided to keep this as an ongoing project; realising instalments every couple of years which people can collect and, hopefully one day, the dictionary will be complete.

Perth Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA)

Perth Cultural Centre

James Street Northbridge

Phone: + 61 (0) 8 9228 6300

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 10am – 5pm

Closed Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.