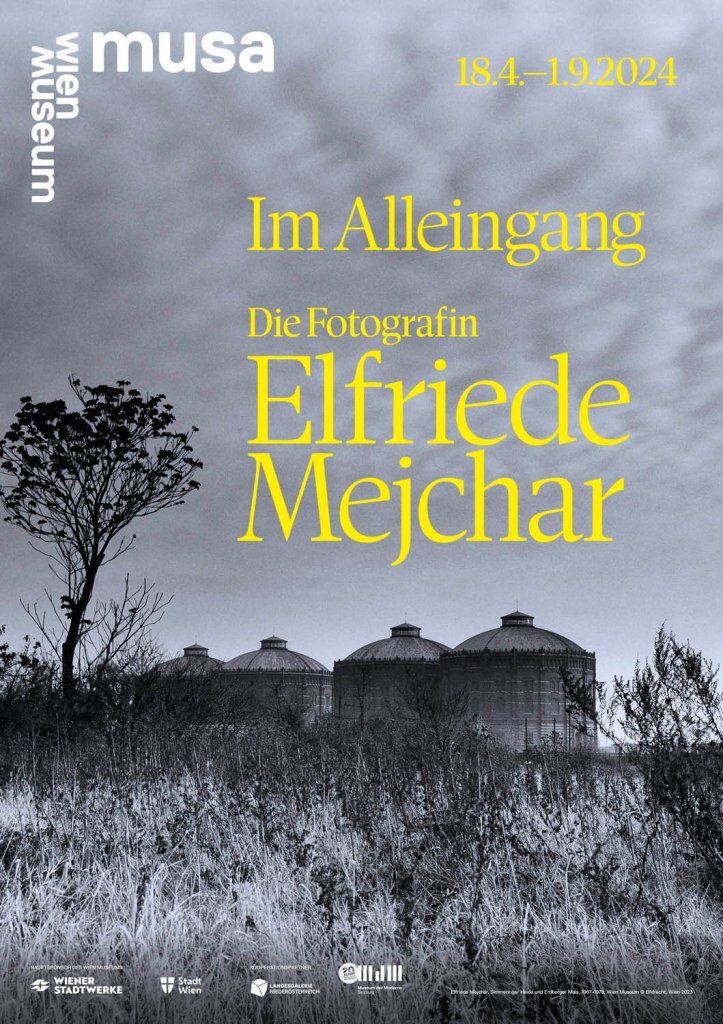

Exhibition dates: 18th April – 1st September, 2024

Curators: Anton Holzer, Frauke Kreutler

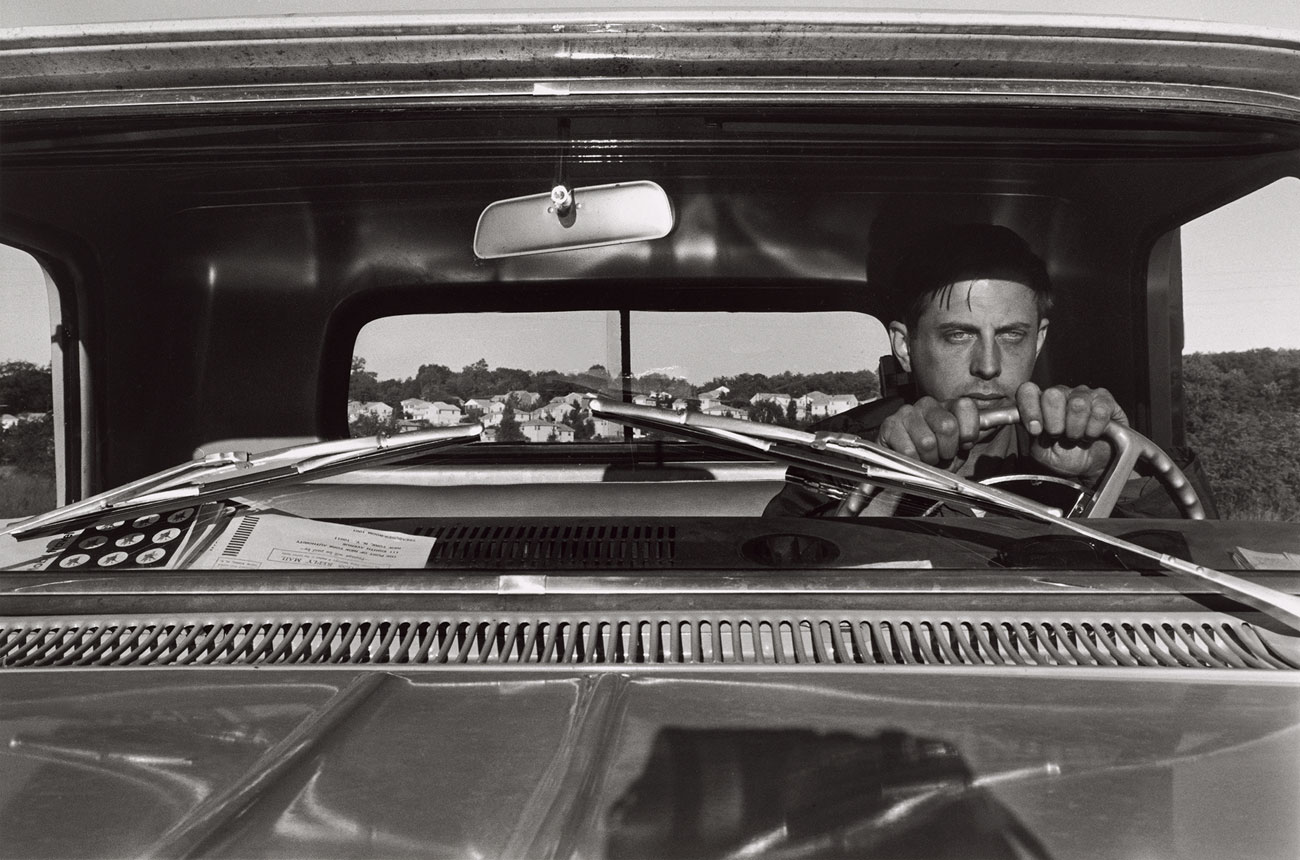

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Light and Shade

1958

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Comment on this magnificent Austrian photographer unknown to me until now will be forthcoming in the future posting on the simultaneous exhibition The Poetry of the Everyday. Photographs by Elfriede Mejchar at Museum der Moderne Salzburg.

Marcus

Many thankx to the Wien Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I am not an artist, I am a photographer.”

Elfriede Mejchar

Installation views of the exhibition On Her Own. The photographer Elfriede Mejchar at Wien Museum musa, Vienna

Elfriede Mejchar (1924-2020) was a major photographic artist, whose richly-varied oeuvre spans more than five decades, from the late 1940s well into the 21st century. The Viennese photographer, who only achieved recognition as an artist towards the end of her career, is now regarded as one of the most important representatives of the Austrian and the international photography scenes. May 10, 2024 marks the hundredth anniversary of her birth.

The exhibition at the Wien Museum presents a broad cross-section of the work of this artistic outsider, and demonstrates how the renewal of postwar Austrian photography was almost “all her own work.” Elfriede Mejchar consciously broke away from the photographic mainstream and the reportage style that was popular at the time. Rather than searching for the so-called “decisive moment,” she approached her subjects in a strongly conceptual and serial manner. She focused not on the extraordinary but on the unspectacular and the commonplace, the everyday and the banal, repeatedly addressing these in new ways in her photographic series.

In an Austria-wide cooperation between the Wien Museum, the State Gallery of Lower Austria, and the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, Elfriede Mejchar’s extensive oeuvre is being presented in 2024 for the first time, simultaneously, in three locations across the country. The exhibitions in Vienna, Krems, and Salzburg approach the work of Mejchar from different perspectives. And the three presentations are accompanied by a jointly conceived catalog published by Hirmer Verlag.

A cooperation between the State Gallery of Lower Austria, the Wien Museum and the Museum der Moderne Salzburg.

Text from the Wien Museum website

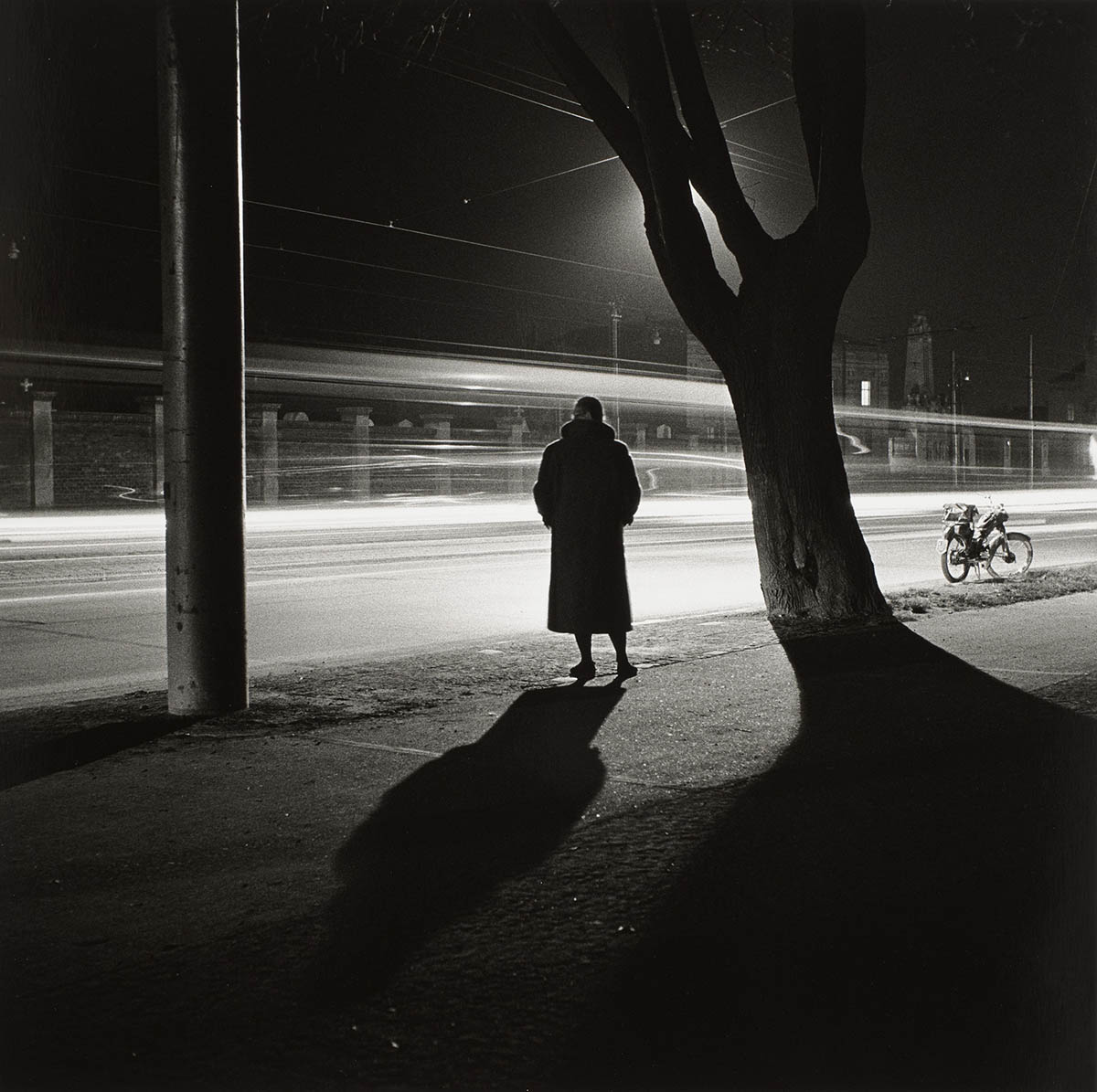

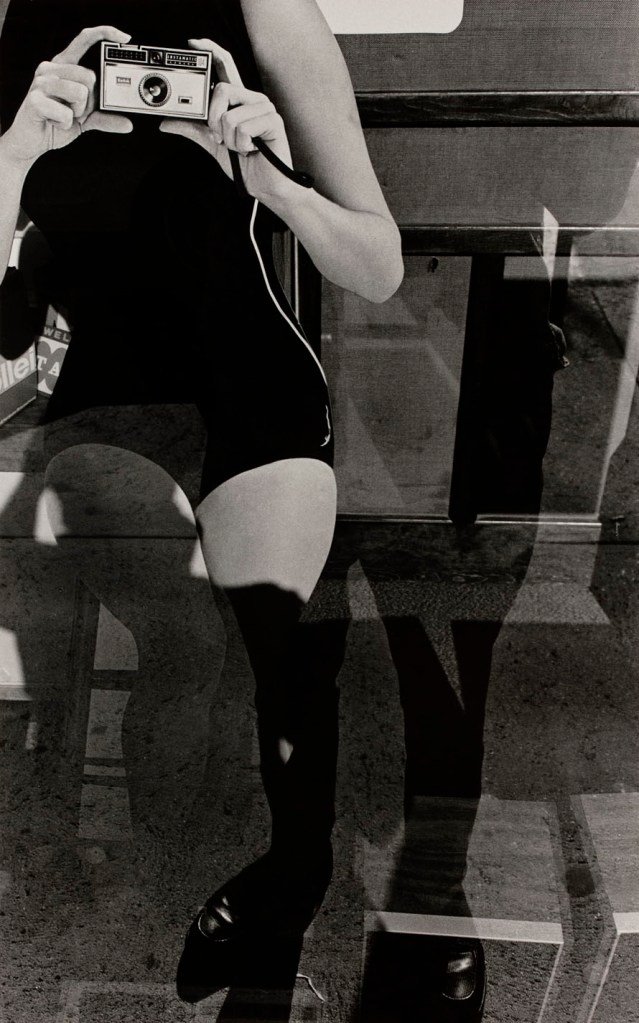

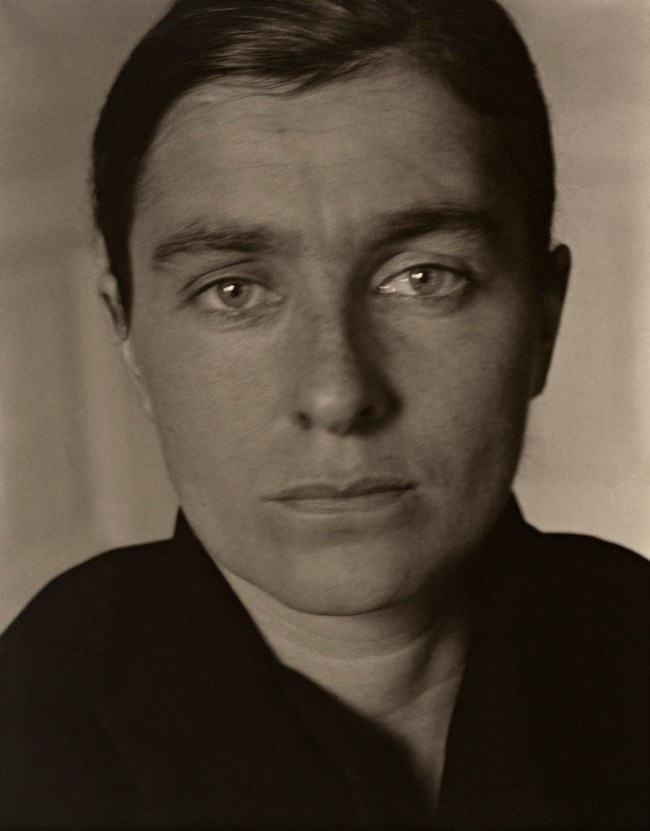

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Light and Shade

1958

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Untitled

1950-1960

From the series Light and Shade

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Untitled (Waiting for the Tram)

1950-1960

From the series Light and Shade

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Vienna 10, Hasengasse 53

1950-1960

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Installation view of the exhibition On Her Own. The photographer Elfriede Mejchar at Wien Museum musa, Vienna showing photographs from Mejchar’s series Simmering Heide and Erdberg Mais (1967-1976, below)

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Simmering Heide and Erdberg Mais

1967-1976

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Simmeringer Heide and Erdberger Mais

1967-1976

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

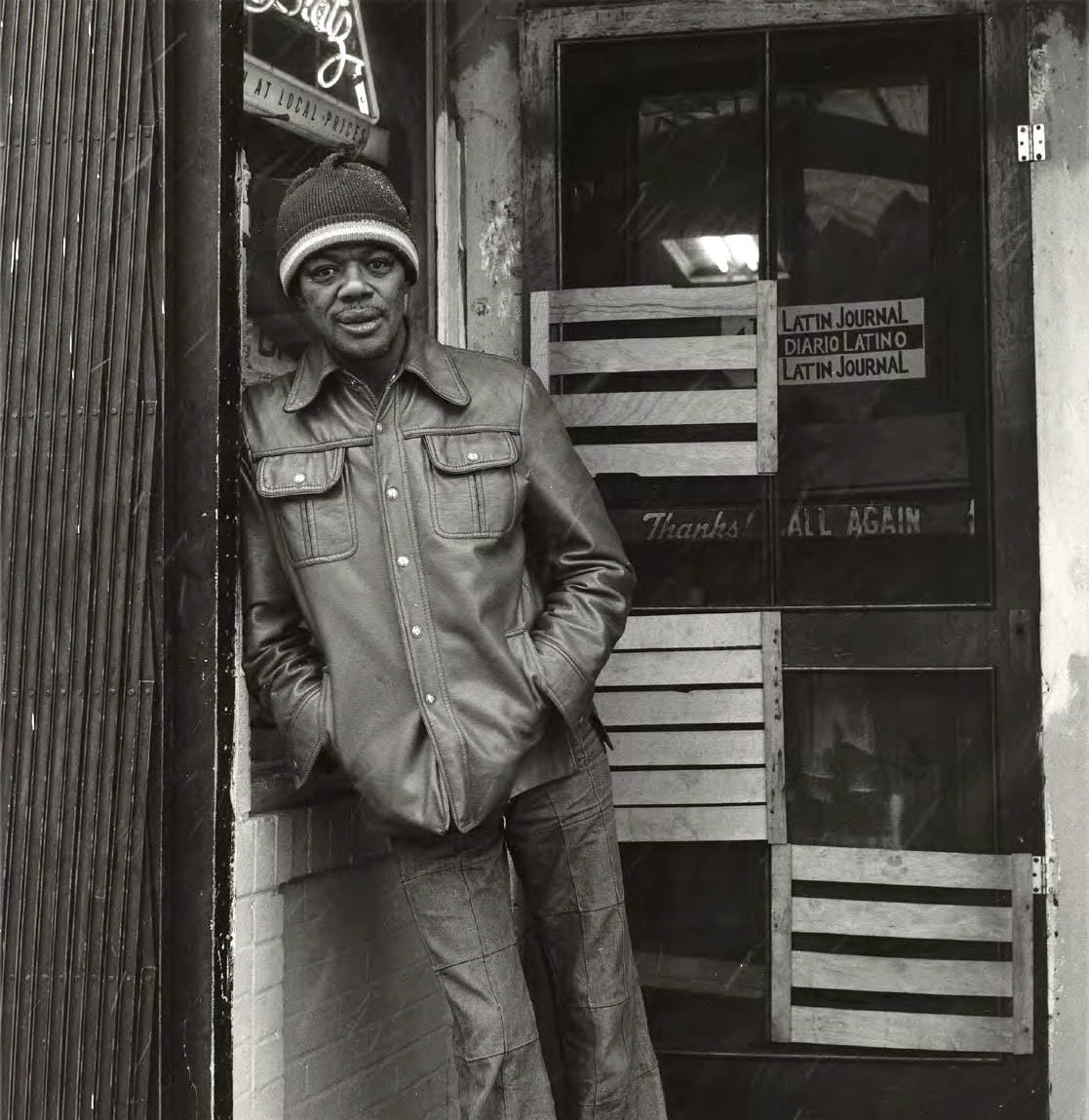

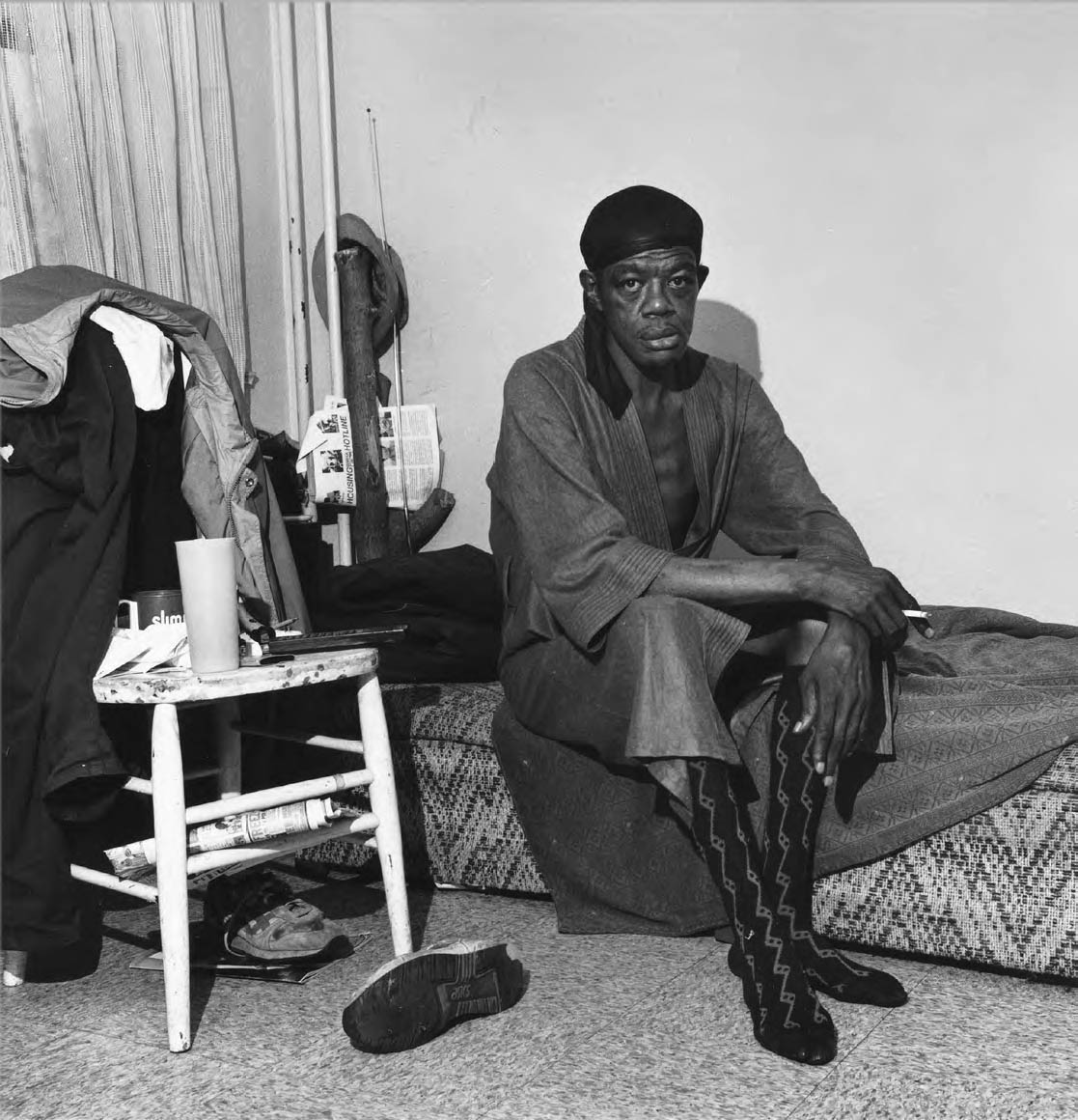

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

At the Hotel

Around 1980

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Triester Strasse

1982-1983

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (1924-2020) was a major photographic artist, whose richly-varied oeuvre spans more than five decades, from the late 1940s well into the 21st century. The Viennese photographer, who only achieved recognition as an artist towards the end of her career, is now regarded as one of the most important representatives of the Austrian and the international photography scenes. May 10, 2024 marks the hundredth anniversary of her birth.

The exhibition in musa presents a broad cross-section of the work of this artistic outsider, and demonstrates how the renewal of postwar Austrian photography was almost “all her own work.” Elfriede Mejchar consciously broke away from the photographic mainstream and the reportage style that was popular at the time. Rather than searching for the so-called “decisive moment,” she approached her subjects in a strongly conceptual and serial manner. She focused not on the extraordinary but on the unspectacular and the commonplace, the everyday and the banal, repeatedly addressing these in new ways in her photographic series.

Elfriede Mejchar revealed her hometown Vienna from the periphery and had little interest in its iconic center, which was already the subject of countless thousands of photographs. As a photographer, she was at home where the city became rural, at the meeting point between urban development zones, derelict sites, green spaces, and post-industrial decay. In her long-term studies she documented the architectural and social textures of Vienna’s suburbs in a way that was both attentive and sober: new buildings advancing ever further onto green land, the monotony of endless arterial roads, derelict industrial complexes, market gardens and ageing gasometers, run-down housing and forgotten areas of landfill and decay. For Mejchar, however, the image of the urban periphery is not grey and the wasteland and its dereliction are repeatedly brightened by moments of unsuspected beauty.

Even if the urban and architectural photography of Vienna plays a major role in Elfriede Mejchar’s oeuvre, the range of subjects addressed in her work is far broader. Just as the photographer sheds a new photographic light on forgotten landscapes and buildings, she also approaches people and plants, places and things, in unexpected and surprising ways. In her incomparable series “Hotels,” she studies the interiors and typologies of Austrian accommodation in great detail, producing fascinating and often brightly coloured still lifes of plants and flowers as a means of aesthetically investigating the intermediate stages between blooming and withering. And in her bold collages and montages, a complex of work that continued to occupy her into her latter years, she created clever fantasy worlds, whose social criticism is only matched by their humour.

In an Austria-wide cooperation between the Wien Museum, the State Gallery of Lower Austria, and the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, Elfriede Mejchar’s extensive oeuvre is being presented in 2024 for the first time, simultaneously, in three locations across the country. The exhibitions in Vienna, Krems, and Salzburg approach the work of Mejchar from different perspectives:

Landesgalerie Niederösterreich. Elfriede Mejchar. Pushing the Boundaries of Photography April 13, 2024 to February 16, 2025 Tuesday – Sunday, 10am-6pm

musa. On her own. The photographer Elfriede Mejchar April 18 to September 1, 2024 Tuesday – Sunday, 10am-6pm

Museum der Moderne Salzburg. The Poetry of Everyday. Photographs by Elfriede Mejchar April 26 to September 15, 2024 Tuesday – Sunday, 10am-6pm

Biography of Elfriede Mejchar

Elfriede Mejchar (1924-2020) is undisputedly one of the most important personalities in Austrian photography. It was only at an advanced age that she received the public recognition she deserved, and in 2002 she was awarded the Federal Chancellery Prize for Artistic Photography and in 2004 the Lower Austrian Prize for Artistic Photography and the City of Vienna Prize for Fine Arts. In 2013, Elfriede Mejchar donated her entire oeuvre to the Province of Lower Austria. The Provincial Collections of Lower Austria have taken on the task of safeguarding this unique oeuvre for future generations and gradually making it accessible to the public. Her work is also prominently represented in the art collection of the Wien Museum, in the Federal Photography Collection and in the SpallArt Collection.

Press release from Wien Museum, Vienna

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Wienerberger Brick Kilns and Housing Estates

1979-1981

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Wienerberger Brick Kilns and Housing Estates

1979-1981

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Installation view of the exhibition On Her Own. The photographer Elfriede Mejchar at Wien Museum musa, Vienna showing text and photographs from the section ‘Allure of the Everyday’

Exhibition texts

“I always marvelled at the wallpaper” (Prologue)

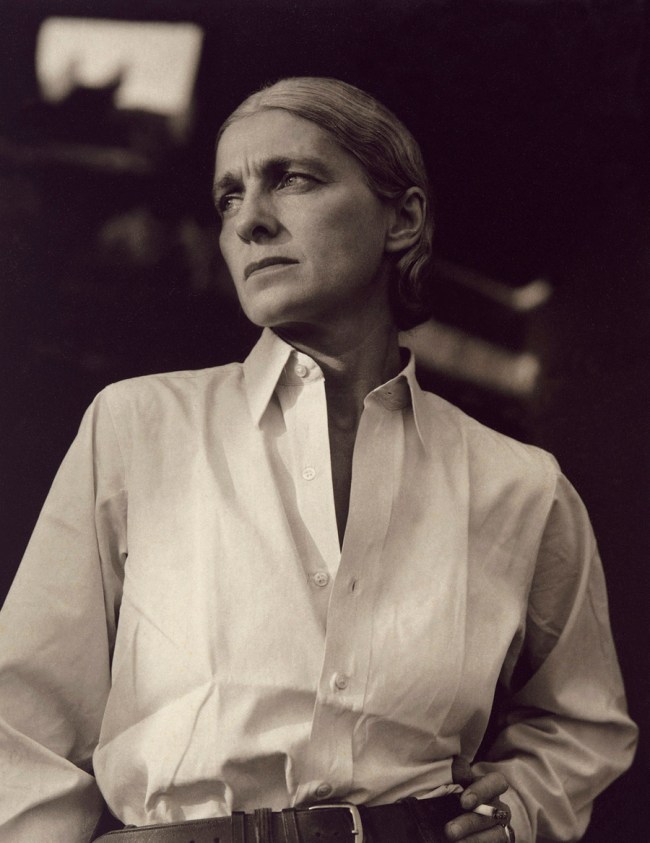

Elfriede Mejchar had two faces as a photographer: one in her day job, and one as an artist. Working for the Federal Monuments Office, she spent many years touring Austria, extensively documenting buildings and artworks in the provinces. On the side, she was a freelance photographic artist. When “at work,” she was bound by the strict criteria of art documentation. As an artist, she forged her own, very different paths.

While in her day job she photographed “great art,” in her free time she focused on the banality of everyday life, for example by taking interior shots of her accommodation over the years. The expenses covered by “the office,” she explained, “were not very generous, and I was always looking for lower-end lodgings. They could be very odd, anything was possible. In particular, I always marvelled at the wallpaper.”

1. Allure of the Everyday

A backlit trash can or advertising column, people waiting on the street, youths in the Bohemian Prater, the geometry of washing lines – even in her early series dating from the 1950s and 1960s, Mejchar’s fascination with scenes from everyday life is clear. She used her camera to record what she saw in the city in a matter-of-fact style, without judgment: the buildings and streets, cars and advertisements, traffic lights and posters. Only occasionally do people feature in her images. Often they seem a little lost. In contrast to many other photographers of her era, Mejchar was not looking for a quick snapshot or the “decisive moment.” “Speed doesn’t suit me,” she once said. Frequently she worked in series, often created over several years. Her focus was not on the extraordinary but on the unspectacular and the commonplace.

Working in Series

“I don’t like single photos very much,” said Elfriede Mejchar, thus describing one of the fundamental features of her photography. For almost 30 years, she explored Vienna’s peripheral zones on the southeast edge of the city. Again and again she returned to these uninviting places on the outskirts, where few people spent much time. In the main she photographed the landscapes, roads, and neighbourhoods in series, usually in parallel, but sometimes as a chronological sequence. For Mejchar as a photographer, the single image could not capture the complexity of this desolate and yet, in her eyes, beautiful landscape. It was the series that allowed her to show the different facets of a subject from ever new perspectives. Through her artistic and conceptual practice, Mejchar forged a completely new path in Austrian photography.

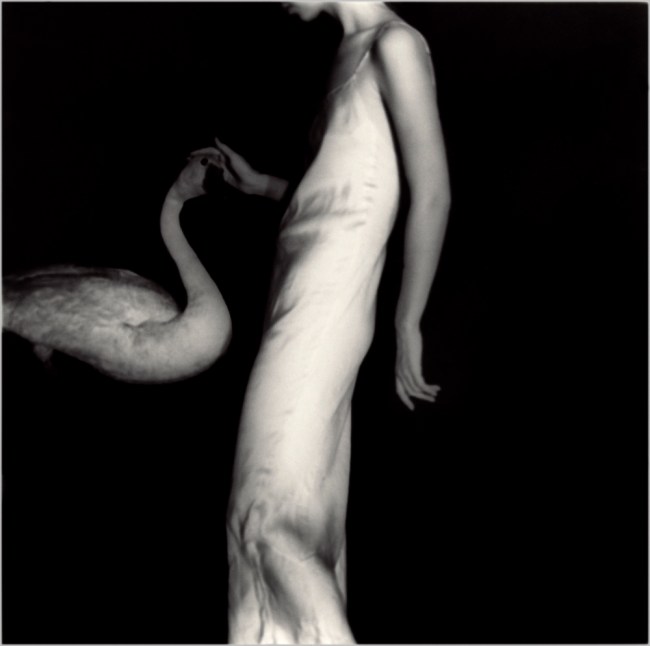

2. Evil Blooms

Throughout her working life, Mejchar photographed art, in other words, things created to last. Her images of flowers were a late counter-project. In these plant studies, some shot in luminous colour, the photographer brought transience and decay into focus, drawing out the fascinating transitions between blooming and withering. “I am not afraid of pathos, nor of kitsch,” Mejchar once said.

Elfriede Mejchar paid no heed to photographic conventions in her freelance work. Unabashed, she took delight in arranging and staging the plants and objects for her photographs in ways that opened up a range of associations. Some of her objects seem almost to come to life under her lens, while others wither away. Yet others invoke images of sexuality and desire.

Putting in a New Light

As a photographic subject, flowers are often dismissed as being romantic, kitsch, or unserious. Mejchar was not afraid of kitsch, but neither was she ever interested in the sweetness of the tulips or amaryllis she photographed. For her, flowers were like sculptures that needed to be shown in a proper light. Mejchar’s “merciless” gaze extended beneath the surface. It drilled into the very substance of the petals, laying bare the skeleton that emerged as the flower withered and capturing the bizarre forms of the dying plant. Yet the artist could not break free entirely of the strong metaphorical imagery of flowers. Sometimes, her shots of them in full bloom or with their inner parts exposed carried a sensual or sexual charge.

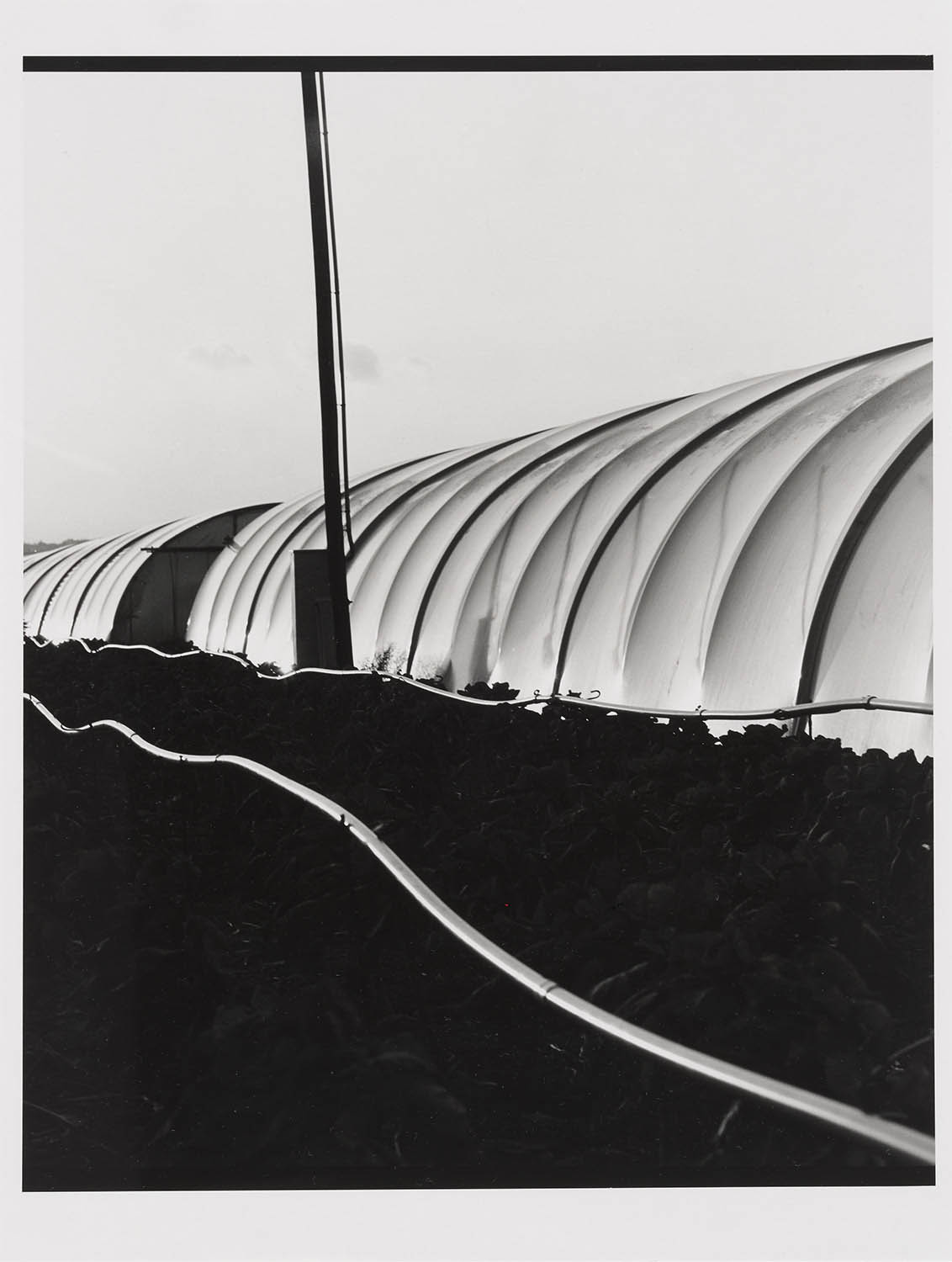

3. Measuring the Periphery

New builds encroaching ever further on the countryside, abandoned factories, fields of vegetables, ageing gasometers, the monotony of interminable highways, makeshift housing, wastelands – as a photographer, Elfriede Mejchar was especially keen on these forgotten landscapes on the margins of the Viennese metropolis. “It was the changes that I was concerned with.”

Starting in the 1960s, Mejchar roamed the city’s peripheral zones with her camera. “These were the sites that interested me the most. Where countryside and city collide.” Her long-term series “Simmeringer Heide and Erdberger Mais,” begun in the 1960s and first shown in 1976 in a solo exhibition at the Museum of the 20th Century, established Mejchar’s reputation as leading photo artist.

Constructing Space

Row upon row of plants, damp soil blanketed by the early morning mist, distant greenhouses, lettuces covering the ground, interspaced with sprinklers – Elfriede Mejchar documented every facet of Vienna’s market gardens at the edge of the city, from detached general views to shots that capture the smallest detail. Her images use a deep depth of field, making it seem almost as if the viewer could reach out and touch the clumps of soil or individual leaves in the foreground. But she also regularly translated landscapes, buildings, and spaces into abstract forms by setting up contrasting oppositions between individual motifs, or by reducing an image to monochrome surfaces.

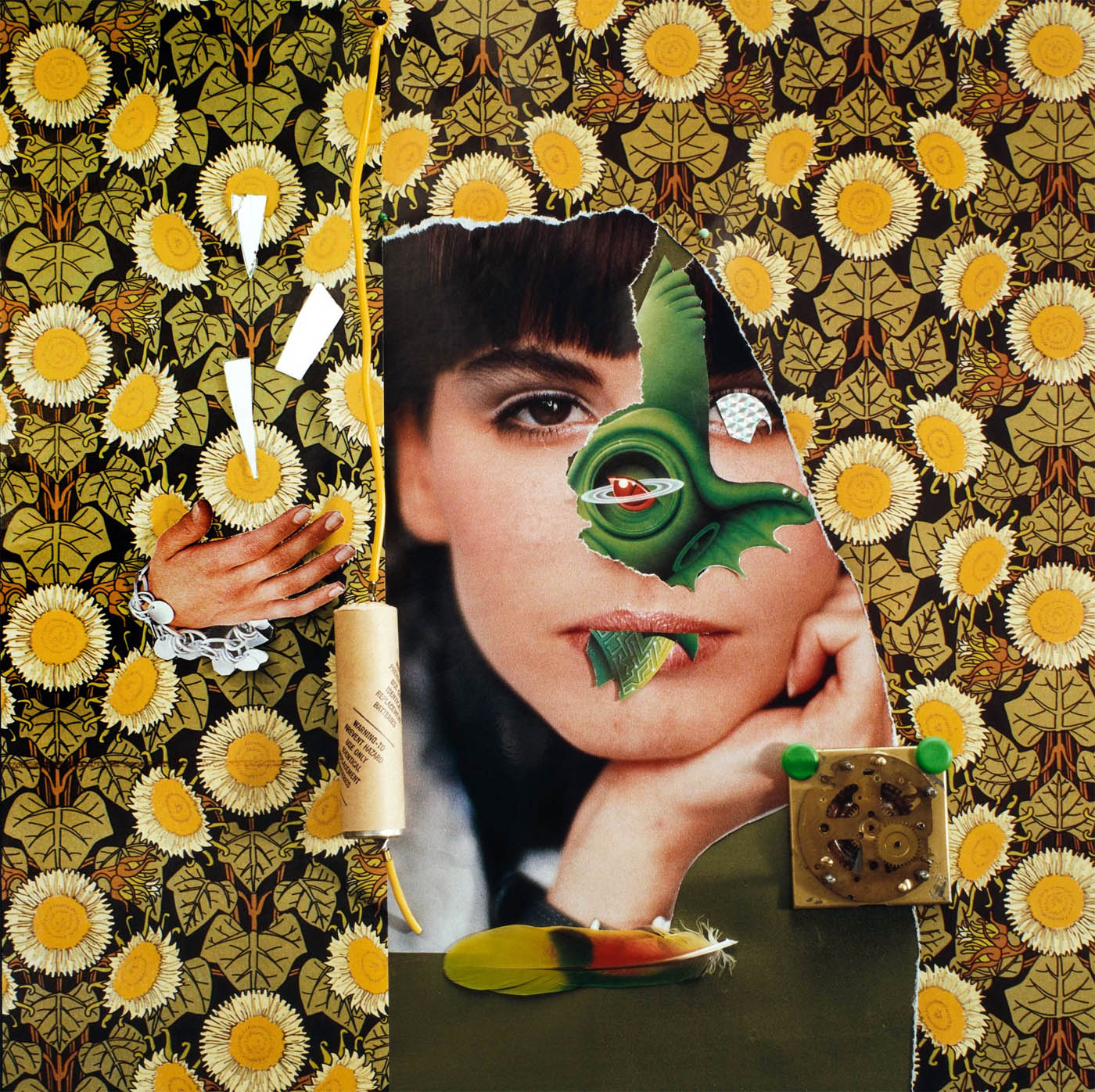

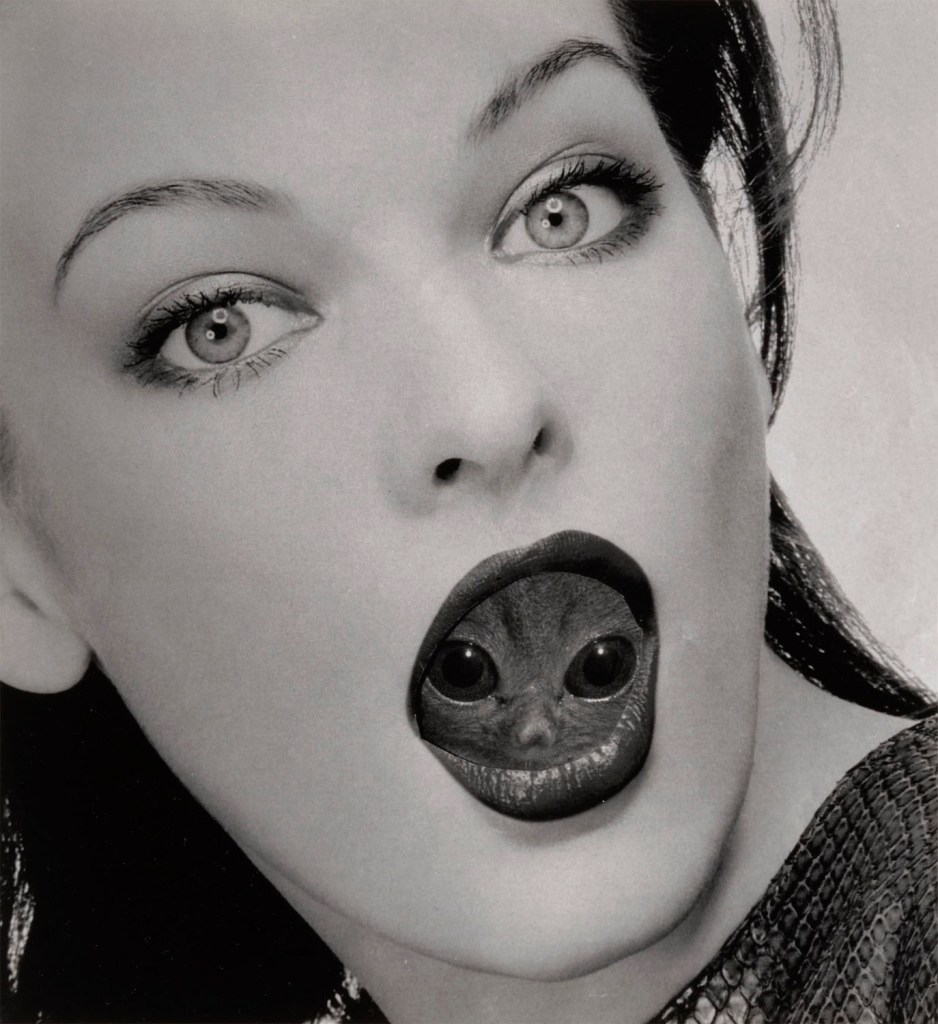

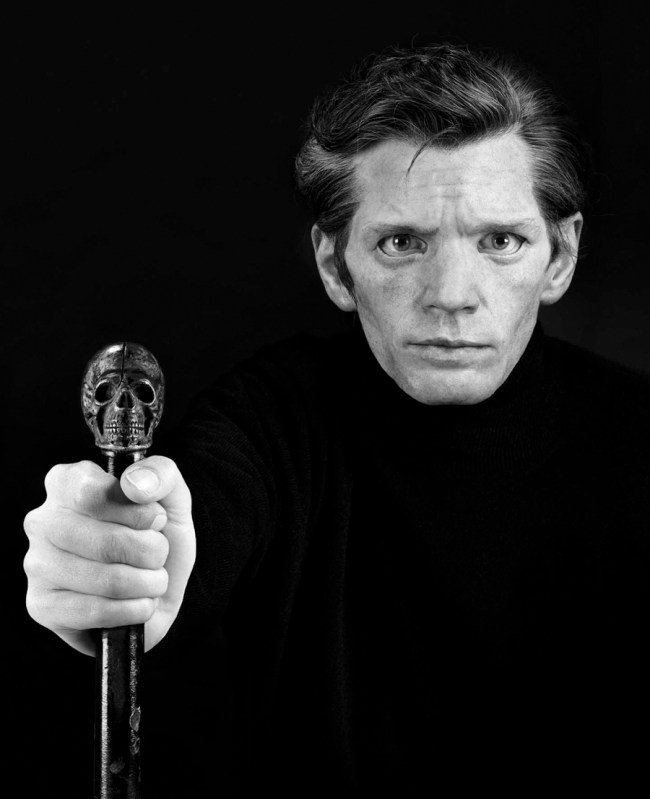

4. Lips and Pistols

Faces ripped from fashion magazines and floral wallpaper, cogs and cigarettes, spools and dressmaking pins, small chains and cables – starting in the 1980s, Mejchar jumbled these found, everyday objects together to create small-scale, theatrical arrangements laced with acerbic wit. “I construct images,” the artist once said of her sarcastic and subversive collages and assemblages. In these composite scenes, Elfriede Mejchar gave free rein to an anarchic desire to assemble and disassemble. At the same time, she used humour and irony to lampoon society’s ideals of perfection, “adorning” beautiful faces with everyday objects, for example, or – with a knowing wink – targeting James Bond’s pistol on the eroticised lips of the beauty industry. Mejchar’s summary: “I like things colourful and crazy.”

Arranging Objects

After retiring from paid employment, Mejchar increasingly concentrated on her work in the studio, which now became a stage for herself and her camera. Here she created ironic, acerbic, and frequently bizarre object combinations, often as an exploration of gender stereotypes. In her collages, she dismantled and critiqued the fashion industry’s preformed ideals of beauty with zest and humour. She took pleasure in experimenting with a whole range of props, rearranging them into new scenes again and again. Fragmented faces from fashion magazines were combined with torn and cut wallpaper, then garnished with cogs, feathers, and cables. She literally nailed the beauty industry to the wall.

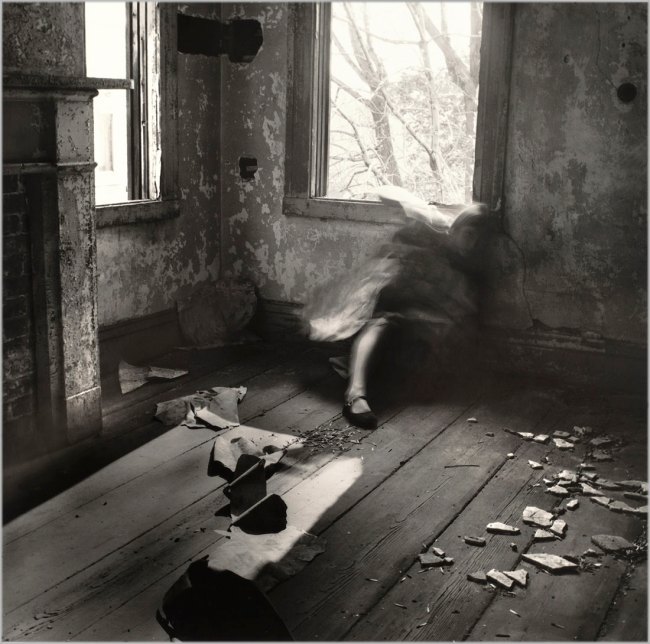

5. Remains and Ruins

The innards of a house scheduled for demolition, derelict industrial estates, overgrown railway lines and buildings, gouged landscapes, forgotten piles of bricks – over many years, Mejchar explored these remains of industrial culture. “My work only began,” she said, “when the people were gone.”

“I took myself off to the factories, going from one road to the next.” In her series “Wienerberger Brick Kilns,” which she photographed from 1979 to 1981 following the closure of the Wienerberger brick factory on Vienna’s southern edge, she made deliberate use of colour photography for the first time. Impregnated with brick dust, the ground and the remains of the industrial architecture glow red under an azure sky, assuming an air of unreality. Mejchar: “I am interested in what remains.”

Seeing in Color

During the first decades of her career as a photographer, Elfriede Mejchar worked in black and white because colour photography was too expensive. All the more astonishing, therefore, is the confidence and precision with which she employed colour as an aesthetic element in the photo series “Wienerberger Brick Kilns” in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Similar to the New Color Photography movement in the USA, Mejchar’s photographic explorations focused primarily on the borders between urban and rural spaces. Her main interest was in landscapes subjected to human interventions. She documented these run-down locations using vivid lighting and brilliant colours, producing unsentimental photographs of high aesthetic quality. In doing so, she opened up an entirely new approach to documentary photography in Austria.

Installation view of the exhibition On Her Own. The photographer Elfriede Mejchar at Wien Museum musa, Vienna showing at second right, Mejchar’s Aether and narcosim (1989-1991, below)

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Aether and narcosim

1989-1991

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Vegetable Tunnels. Simmering Market Gardens

1990-1994

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Vegetable Tunnels. Simmering Market Gardens

1990-1994

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

A Costume of Borrowed Identity

1990-1991

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

A Costume of Borrowed Identity

1990-1991

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Amaryllis

1996

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Amaryllis

2001

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

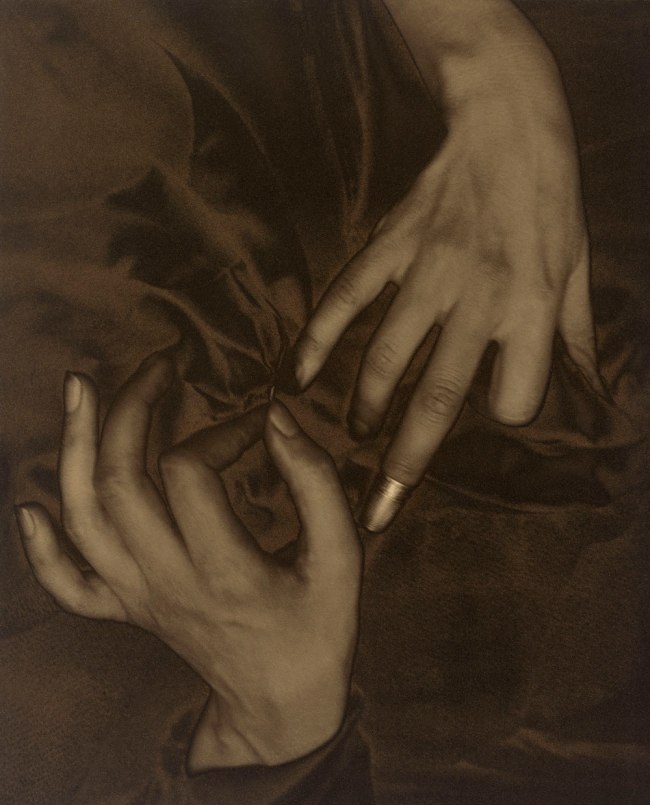

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

Hands in Lap

2002

Wien Museum

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

From the series Nobody is Perfect

1989-2007

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2024

Elfriede Mejchar (Austrian, 1924-2020)

From the series Nobody is Perfect

1989-2007

© Bildrecht, Vienna 2024

Unknown photographer

Elfriede Mejchar with Linhof camera and tripod in the Federal Monuments Office

Late 1970s

State Collections of Lower Austria

Poster for the exhibition On Her Own. The Photographer Elfriede Mejchar

Graphic: Studio Kehrer

Wien Museum MUSA

1010 Vienna, Felderstraße 6-8

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Sunday 10am – 6pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.