Exhibition dates: 26th September 2012 – 20th January, 2013

Many thankx to the Städel Museum for allowing me to publish the reproductions of the artwork in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation photographs of the exhibition Dark Romanticism. From Goya to Max Ernst at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt

Photos: Norbert Miguletz

Installation views of the exhibition Dark Romanticism. From Goya to Max Ernst at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing at left in the bottom image, Thomas Cole’s Expulsion: Moon and Firelight (c. 1828, below); at centre, Johann Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (The Incubus) (1781-1782, below); at second right, Samuel Colman’s The Edge of Doom (1836-1838, below); and at right, William Blake’s The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun (c. 1803-1805, below)

Photos: Norbert Miguletz

Thomas Cole (American born England, 1801-1848)

Expulsion: Moon and Firelight

c. 1828

Oil on canvas

91.4 by 122cm (36.0 in × 48.0 in)

Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

Johann Henry Fuseli (Swiss, 1741-1825)

The Nightmare (The Incubus)

1781-1782

Oil on canvas

77cm (30.3 in) x 64cm (25.1 in)

Goethehaus (Frankfurt) collection

Samuel Colman (British, 1780-1845)

The Edge of Doom

1836-1838

Oil on canvas

54 x 78 1/2 in. (137.2 x 199.4cm)

Brooklyn Museum

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun

c. 1803-1805

Watercolour, graphite and incised lines

43.7 x 34.8cm

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of William Augustus White

Johann Henry Fuseli (Swiss, 1741-1825)

The Nightmare

1781

Oil on canvas

101.6 × 126.7cm

Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society

© Bridgeman Art Library

Johann Henry Fuseli (Swiss, 1741-1825)

Die wahnsinnige Kate (La folie de Kate) (Mad Kate)

1806-1807

Oil on canvas

92cm (36.2 in) x 72.3cm (28.4 in)

Francfort-sur-le-Main, Frankfurter Goethe-Haus

Freies Deutsches Hochstift, inv.1955-007

© Ursula Edelmann/ARTOTHEK

Installation view of the exhibition Dark Romanticism. From Goya to Max Ernst at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing Paul Delaroche’s The Wife of the Artist, Louise Vernet, on her Death Bed (1845, below)

Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Paul Hippolyte Delaroche (French, 1797-1856)

Louise Vernet, the artist’s wife, on her Deathbed

1845-1846

Oil on canvas

62 x 74.5cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes

© Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes

Installation view of the exhibition Dark Romanticism. From Goya to Max Ernst at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing Gabriel von Max’s The White Woman (1900, below)

Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Gabriel von Max (Austrian, 1840-1915)

The White Woman

1900

Oil on canvas

100 x 72cm

Private Collection

Johann Henry Fuseli (Swiss, 1741-1825)

Sin Pursued by Death

1794-1796

Oil on canvas

Kunsthaus, Zürich

Théodore Géricault (French, 1791–1824)

Cuirassier blessé quittant le feu / The Wounded Cuirassier

1814

Oil on canvas

358cm (11.7 ft) x 294cm (115.7 in)

Louvre Museum

The Wounded Cuirassier (French: Le Cuirassier blessé quittant le feu) is an oil painting of a single anonymous soldier descending a slope with his nervous horse by the French Romantic painter and lithographer Théodore Géricault (1791–1824). In this 1814 Salon entry, Géricault decided to turn away from scenes of heroism in favour of a subject that is on the losing side of the battle. On display in the aftermath of France’s disastrous military campaign in Russia, this life-size painting captured the feeling of a nation in defeat. There are no visible wounds on the figure, and the title has sometimes been interpreted to refer to soldier’s injured pride. The painting stood in stark contrast with Géricault’s Charging Chasseur, as it didn’t focus on glory or the spectacle of battle. Only his Signboard of a Hoofsmith, which is currently in a private collection, bears any resemblance in form or function to this painting.

The final salon version of The Wounded Cuirassier is at the Musée du Louvre and the smaller, study version, is located at the Brooklyn Museum.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774-1840)

Kügelgen’s Tomb

1821-1822

Oil on canvas

41.5 x 55.5cm

Die Lübecker Museen, Museum Behnhaus Drägerhaus, on loan from private collection

Ernst Ferdinand Oehme (German, 1797-1855)

Procession in the Fog

1828

Oil on canvas

81.5 x 105.5cm

Galerie Neue Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774-1840)

Rivage avec la lune cachée par des nuages (Clair de lune sur la mer) / Mond hinter Wolken über dem Meeresufer (Meeresküste bei Mondschein) / Moon behind clouds over the seashore (seashore by moonlight)

1836

Hambourg, Hamburger Kunsthalle

© BPK, Berlin, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Elke Walford

Samuel Colman (American, 1780-1845)

The Edge of Doom

1836-1838

Oil on canvas

137.2 x 199.4cm

Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Laura L. Barnes

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (French, 1825-1905)

Dante And Virgil In Hell

1850

Oil on canvas

280.5cm (110.4 in) x 225.3cm (88.7 in)

Musée d’Orsay

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Arnold Böcklin (Swiss, 1827-1901)

Villa by the Sea

1871-1874

Oil on canvas

108 x 154cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Serafino Macchiati (Italian, 1860-1916)

Le Visionnaire (The Visionary)

1904

Oil on canvas

55.0 x 38.5cm

Don Serafino Macchiati, 1916

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

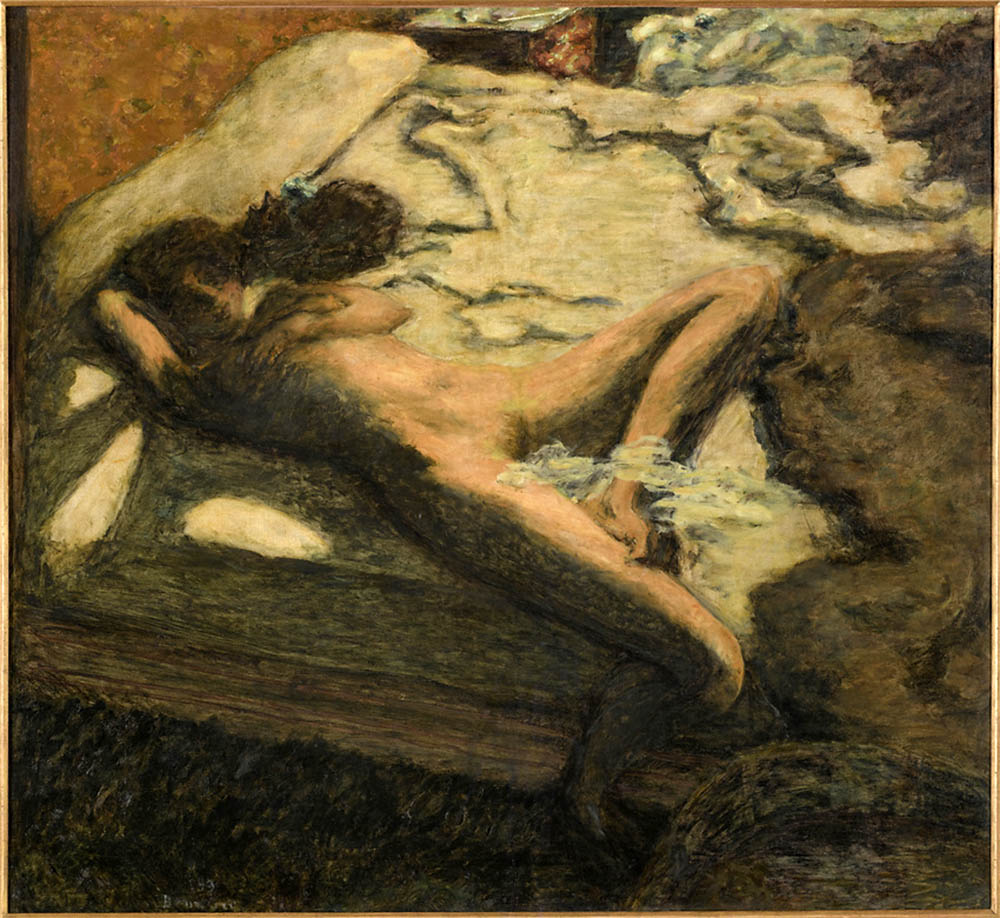

Pierre Bonnard (French, 1867-1945)

Femme assoupie sur un lit (Woman sleeping on a bed)

1899

huile sur toile

96.4 x 105.2cm

Achat en vente publique, 1948

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947)

A veritable hymn to voluptuousness, The Indolent Woman is a painting which relies on contrasts: the title already clashes with the young woman’s posture. Her body with its tense muscles – the left foot is literally hooked on to the right thigh – belies any idea of rest or laziness. Similarly, the modest gesture of the arm across the breasts is contradicted by the spread thighs. Sinuous lines run throughout the composition, materialised by the dark shadows on the sheets still bearing the undulating line of the bodies and the heavy jumble of the bedclothes. The electric blue “smoke” drifting across the woman’s thigh and ankle and the sumptuous dark hair spread across the bed accentuate the painting’s erotic charge.

This woman spread out for all to see after lovemaking is the epitome of unveiled intimacy, violent, passionate and sombre and, in the end, very “fin de siècle”. We are also struck by the modernity of the composition seen from above, with its monumental bed which seems to tip towards the viewer. The woman’s body, gnawed by shadows, has a tonic vibrant texture which gives it a strong timeless presence.

This is a crucial work in Bonnard’s career because it is one of the first nudes he painted, previously showing little interest in the theme. It can be compared with two other canvases from the same period: Blue Nude from the Kaganovitch collection and Man and Woman.

After seeing this painting, the famous art dealer and publisher Ambroise Vollard asked Bonnard to illustrate a collection of Paul Verlaine’s poetry, Parallèlement, which was published in 1900.

Text from the Musée d’Orsay website

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Dream caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second before Awakening

1944

Oil on wood

51 x 41cm

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2012

The Städel Museum’s major special exhibition Dark Romanticism. From Goya to Max Ernst will be on view from September 26th, 2012 until January 20th, 2013. It is the first German exhibition to focus on the dark aspect of Romanticism and its legacy, mainly evident in Symbolism and Surrealism. In the museum’s exhibition house this important exhibition, comprising over 200 paintings, sculptures, graphic works, photographs and films, will present the fascination that many artists felt for the gloomy, the secretive and the evil. Using outstanding works in the museum’s collection on the subject by Francisco de Goya, Eugène Delacroix, Franz von Stuck or Max Ernst as a starting point, the exhibition is also presenting important loans from internationally renowned collections, such as the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée du Louvre, both in Paris, the Museo del Prado in Madrid and the Art Institute of Chicago. The works on display by Goya, Johann Heinrich Fuseli and William Blake, Théodore Géricault and Delacroix, as well as Caspar David Friedrich, convey a Romantic spirit which by the end of the 18th century had taken hold all over Europe. In the 20th century artists such as Salvador Dalí, René Magritte or Paul Klee and Max Ernst continued to think in this vein. The art works speak of loneliness and melancholy, passion and death, of the fascination with horror and the irrationality of dreams. After Frankfurt the exhibition, conceived by the Städel Museum, will travel to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

The exhibition’s take on the subject is geographically and chronologically comprehensive, thereby shedding light on the links between different centres of Romanticism, and thus retracing complex iconographic developments of the time. It is conceived to stimulate interest in the sombre aspects of Romanticism and to expand understanding of this movement. Many of the artistic developments and positions presented here emerge from a shattered trust in enlightened and progressive thought, which took hold soon after the French Revolution – initially celebrated as the dawn of a new age – at the end of the 18th century. Bloodstained terror and war brought suffering and eventually caused the social order in large parts of Europe to break down. The disillusionment was as great as the original enthusiasm when the dark aspects of the Enlightenment were revealed in all their harshness. Young literary figures and artists turned to the reverse side of Reason. The horrific, the miraculous and the grotesque challenged the supremacy of the beautiful and the immaculate. The appeal of legends and fairy tales and the fascination with the Middle Ages competed with the ideal of Antiquity. The local countryside became increasingly attractive and was a favoured subject for artists. The bright light of day encountered the fog and mysterious darkness of the night.

The exhibition is divided into seven chapters. It begins with a group of outstanding works by Johann Heinrich Fuseli. The artist had initially studied to be an evangelical preacher in Switzerland. With his painting The Nightmare (Frankfurt Goethe-Museum) he created an icon of dark Romanticism. This work opens the presentation, which extends over two levels of the temporary exhibition space. Fuseli’s contemporaries were deeply disturbed by the presence of the incubus (daemon) and the lecherous horse – elements of popular superstition – enriching a scene set in the present. In addition, the erotic-compulsive and daemonic content, as well as the depressed atmosphere, catered to the needs of the voyeur. The other six works by Fuseli – loans from the Kunsthaus Zürich, the Royal Academy London and the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart – represent the characteristics of his art: the competition between good and evil, suffering and lust, light and darkness. Fuseli’s innovative pictorial language influenced a number of artists – among them William Blake, whose famous water colour The Great Red Dragon from the Brooklyn Museum will be on view in Europe for the first time in ten years.

The second room of the exhibition is dedicated to the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya. The Städel will display six of his works – including masterpieces such as The Witches’ Flight from the Prado in Madrid and the representations of cannibals from Besançon. A large group of works on paper from the Städel’s own collection will be shown, too. The Spaniard blurs the distinction between the real and the imaginary. Perpetrator and victim repeatedly exchange roles. Good and evil, sense and nonsense – much remains enigmatic. Goya’s cryptic pictorial worlds influenced numerous artists in France and Belgium, including Delacroix, Géricault, Victor Hugo and Antoine Wiertz, whose works will be presented in the following room. Atmosphere and passion were more important to these artists than anatomical accuracy.

Among the German artists – who are the focus of the next section of the exhibition – it is Carl Blechen who is especially close to Goya and Delacroix. His paintings are a testimony to his lust for gloom. His soft spot for the controversial author E. T. A. Hoffmann – also known as “Ghost-Hoffmann” in Germany – led Blechen to paint works such as Pater Medardus (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin) – a portrait of the mad protagonist in The Devil’s Elixirs. The artist was not alone in Germany when it came to a penchant for dark and disturbing subjects. Caspar David Friedrich’s works, too, contain gruesome elements: cemeteries, open graves, abandoned ruins, ships steered by an invisible hand, lonely gorges and forests are pervasive in his oeuvre. One does not only need to look at the scenes of mourning in the sketchbook at the Kunsthalle Mannheim for the omnipresent theme of death. Friedrich is prominently represented in the exhibition with his paintings Moon Behind Clouds above the Seashore from the Hamburger Kunsthalle and Kügelgen’s Grave from the Lübecker Museums, as well as with one of his last privately owned works, Ship at Deep Sea with full Sails.

Friedrich’s paintings are steeped in oppressive silence. This uncompromising attitude anticipates the ideas of Symbolism, which will be considered in the next chapter of the exhibition. These ‘Neo-Romantics’ stylised speechlessness as the ideal mode of human communication, which would lead to fundamental and seminal insights. Odilon Redon’s masterpiece Closed Eyes, a loan from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, impressively encapsulates this notion. Paintings by Arnold Böcklin, James Ensor, Fernand Khnopff or Edvard Munch also embody this idea. However, as with the Romantics, these restrained works are face to face with works where anxiety and repressed passions are brought unrestrainedly to the surface; works that are unsettling in their radicalism even today. While Gustave Moreau, Max Klinger, Franz von Stuck and Alfred Kubin belong to the art historical canon, here the exhibition presents artists who are still to be discovered in Germany: Jean-Joseph Carriès, Paul Dardé, Jean Delville, Julien-Adolphe Duvocelle, Léon Frédéric, Eugène Laermans and Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer.

The presentation concludes with the Surrealist movement, founded by André Breton. He inspired artists such as Ernst, Brassaϊ or Dalí, to create their wondrous pictorial realms from the reservoir of the subconscious and celebrated them as fantasy’s victory over the “factual world”. Max Ernst vehemently called for “the borders between the so-called inner and outer world” to be blurred. He demonstrated this most clearly in his forest paintings, four of which have been assembled for this exhibition, one of them the major work Vision Provoked by the Nocturnal Aspect of the Porte Saint-Denis (private collection). The art historian Carl Einstein considered the Surrealists to be the Romantics’ successors and coined the phrase ‘the Romantic generation’. In spite of this historical link the Surrealists were far from retrospective. On the contrary: no other movement was so open to new media; photography and film were seen as equal to traditional media. Alongside literature, film established itself as the main arena for dark Romanticism in the 20th century. This is where evil, the thrill of fear and the lust for horror and gloom found a new home. In cooperation with the Deutsches Filmmuseum the Städel will for the first time present extracts from classics such as Frankenstein (1931), Dracula (1931), Faust (1926), Vampyr (1931-32) and The Phantom Carriage (1921) within an exhibition.

The exhibition, which presents the Romantic as a mindset that prevailed throughout Europe and remained influential beyond the 19th century, is accompanied by a substantial catalogue. As is true for any designation of an epoch, Romanticism too is nothing more than an auxiliary construction, defined less by the exterior characteristics of an artwork than by the inner sentiment of the artist. The term “dark Romanticism” cannot be traced to its origins, but – as is also valid for Romanticism per se – comes from literary studies. The German term is closely linked to the professor of English Studies Mario Praz and his publication La carne, la morte e il diavolo nella letteratura romantica of 1930, which was published in German in 1963 as Liebe, Tod und Teufel. Die schwarze Romantik (literally: Love, Death and Devil. Dark Romanticism).

Press release from the Städel Museum website

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Witches in the Air

1797-1798

Oil on canvas

43.5 × 30.5cm (17 1/8 in × 12 in)

Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

© Museo Nacional del Prado

Witches’ Flight (Spanish: Vuelo de Brujas, also known as Witches in Flight or Witches in the Air) is an oil-on-canvas painting completed in 1798 by the Spanish painter Francisco Goya. It was part of a series of six paintings related to witchcraft acquired by the Duke and Duchess of Osuna in 1798. It has been described as “the most beautiful and powerful of Goya’s Osuna witch paintings.” …

At center point are three semi-nude witches wearing penitential coroza bearing aloft a writhing nude figure, their mouths close to their victim, as if to devour him or suck his blood. Below, two figures in peasants’ garb recoil from the spectacle: one has thrown himself to the ground covering his ears, the other attempts to escape by covering himself with a blanket, making the fig hand gesture to ward off the evil eye. Finally, a donkey emerges on the right, seemingly oblivious to the rest of the scene.

The general scholarly consensus is that the painting represents a rationalist critique of superstition and ignorance, particularly in religious matters: the witches’ corozas are not only emblematic of the violence of the Spanish Inquisition (the upward flames indicate that they have been condemned as unrepentant heretics and will be burned at the stake), but are also reminiscent of episcopal mitres, bearing the characteristic double points. The accusations of religious tribunals are thus reflected back on themselves, whose actions are implicitly equated with superstition and ritualised sacrifice. The bystanders can then be understood either as appalled but unable to do anything or wilfully ignorant and unwilling to intervene.

The donkey, finally, is the traditional symbol of ignorance.

Text from the Wikipedia website

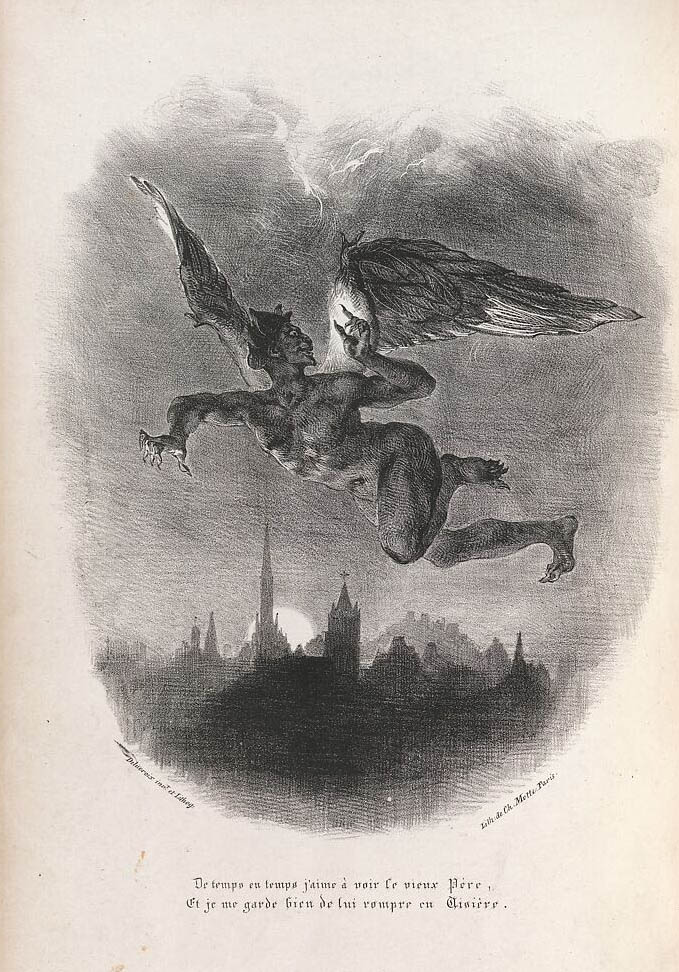

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798-1863)

Mephistopheles in the air, illustration for from Goethe’s Faust

1828

Lithograph

Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum

© All rights reserved

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Flying Folly (Disparate Volante)

from “The proverbs (Los proverbios)”, plate 5, 1816-1819, 1

Edition, 1864

Etching and aquatint

21.7 x 32.6cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

“I am not afraid of witches, goblins, apparitions, boastful giants, evil spirits, leprechauns, etc., nor of any other kind of creatures except human beings.”

Francisco Goya

An enthusiastic champion of Enlightenment values, Goya was also on close terms with the progressive nobility, but his doubts and disillusionment increased as the French Revolution was succeeded by the Terror, and Europe was torn apart by warring armies.

The deceptively clear distinction between enlightenment and obscurantism was now supplanted by the vision of a new, grey, frightening and uncertain world, in which no sharp line could be drawn between good and evil, reality and fantasy, reason and absurdity, the beliefs of the past and the revolutionary fervour of the present.

But instead of living in the past or doing nothing, Goya swapped his court painter’s brush for the etcher’s unsparing needle. Black in all its shades was the keynote of the many series of engravings he now produced on freely chosen themes, with only the Inquisition’s censors to contend with.

The Caprices, a series produced at the end of the 18th century, reflects his amazement and exasperation at the imaginative wealth of Spanish popular culture, steeped in the superstition, fanaticism and ignorance promoted by the Jesuits.

Ten years later, the atrocities which marked the war against Napoleon inspired The Disasters of War – a cry of outrage and horror at the barbaric excesses of the “Grande Nation” and the terrifying emptiness of a world with no God or morality.

Anonymous. “The Angel of the Odd. Dark Romanticism from Goya to Max Ernst,” on the Musée D’Orsay website Nd [Online] Cited 12/08/2024

Louis Candide Boulanger (French, 1806-1867)

Les Fantômes

1829

Oil on canvas

Maison de Victor Hugo

Carl Blechen (German, 1798-1840)

Scaffold in Storm

1834

Oil on canvas and on board

29.5cm (11.6 in) x 46cm (18.1 in)

Galerie Neue Meister

Carl Eduard Ferdinand Blechen (29 July 1798 – 23 July 1840) was a German landscape painter and a professor at the Academy of Arts, Berlin. His distinctive style was characteristic of the Romantic ideals of natural beauty.

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798-1863)

Hamlet and Horatio in the Graveyard

1839

Oil on canvas

29.5cm (11.6 in) x 36cm (14.1 in)

Louvre Museum

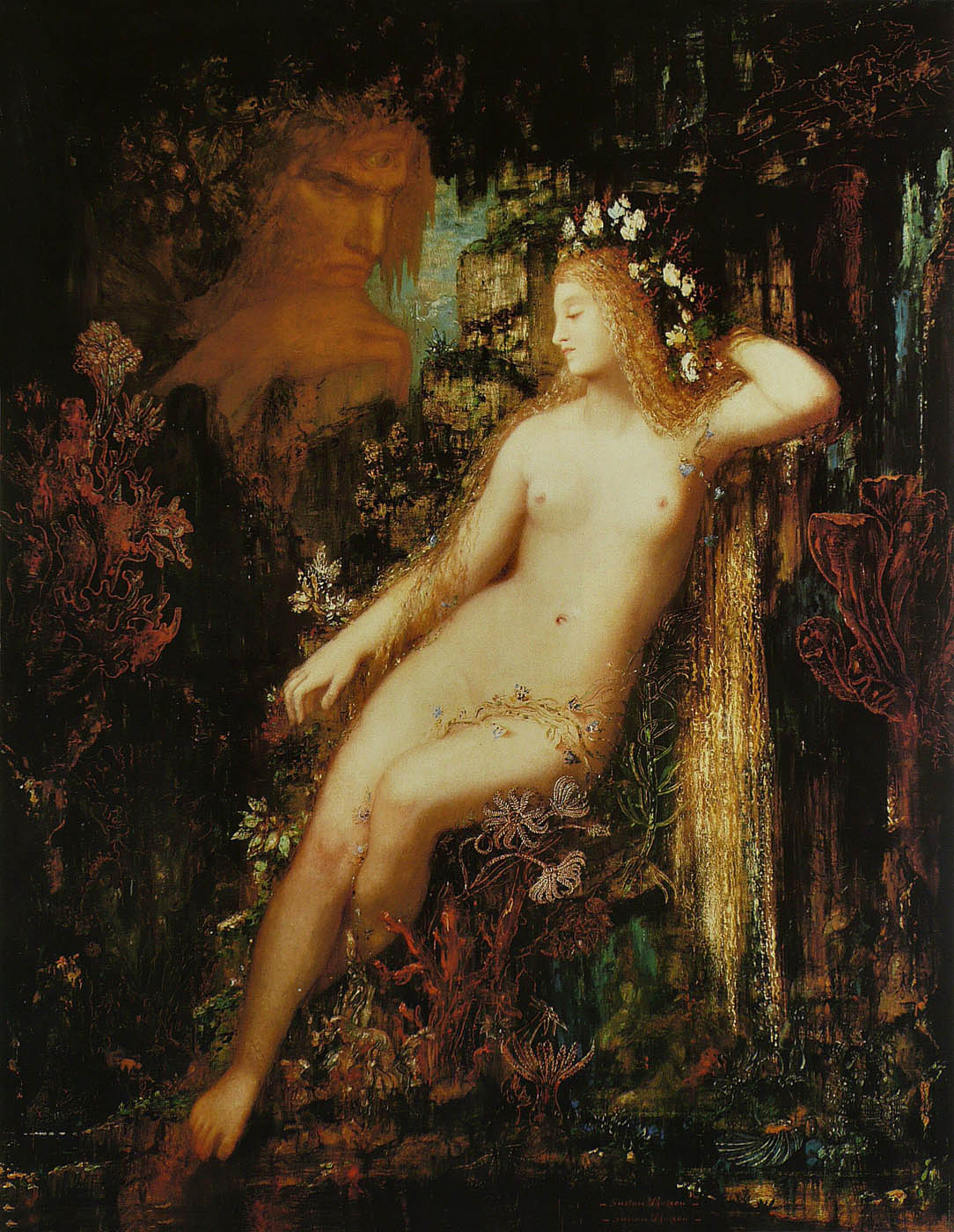

Gustave Moreau (French, 1826-1898)

Galatea

c. 1880

Oil on panel

85.5cm (33.6 in) x 66cm (25.9 in)

Musée d’Orsay

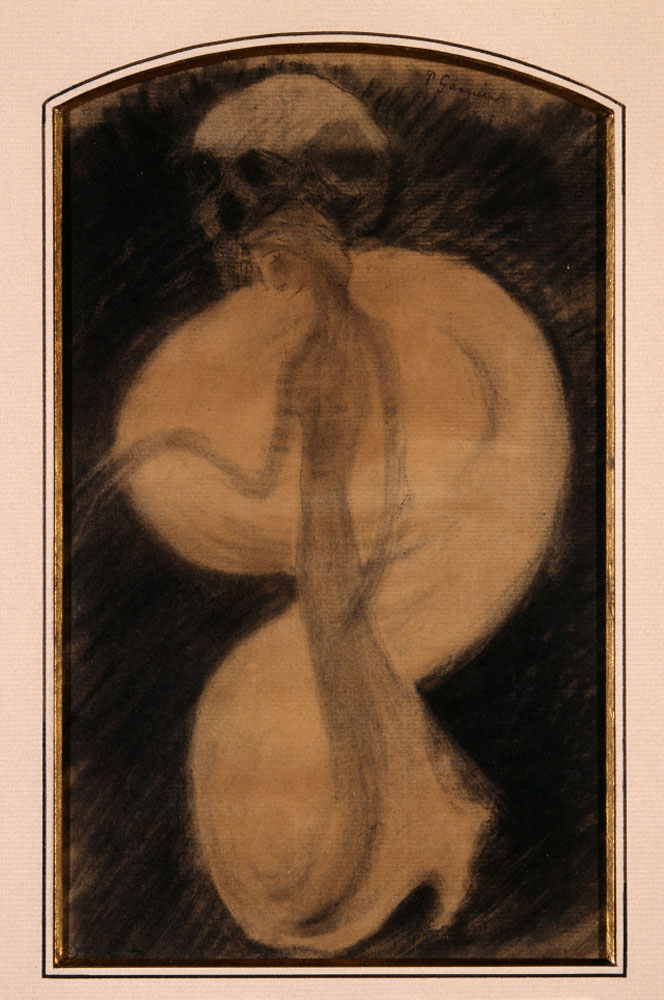

Paul Gauguin (French, 1848-1903)

Madame la Mort

1890-1891

Charcoal on paper with wash highlights

33,5 x 23cm

Don de la société des Amis du musée d’Orsay, 1991

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Gérard Blot

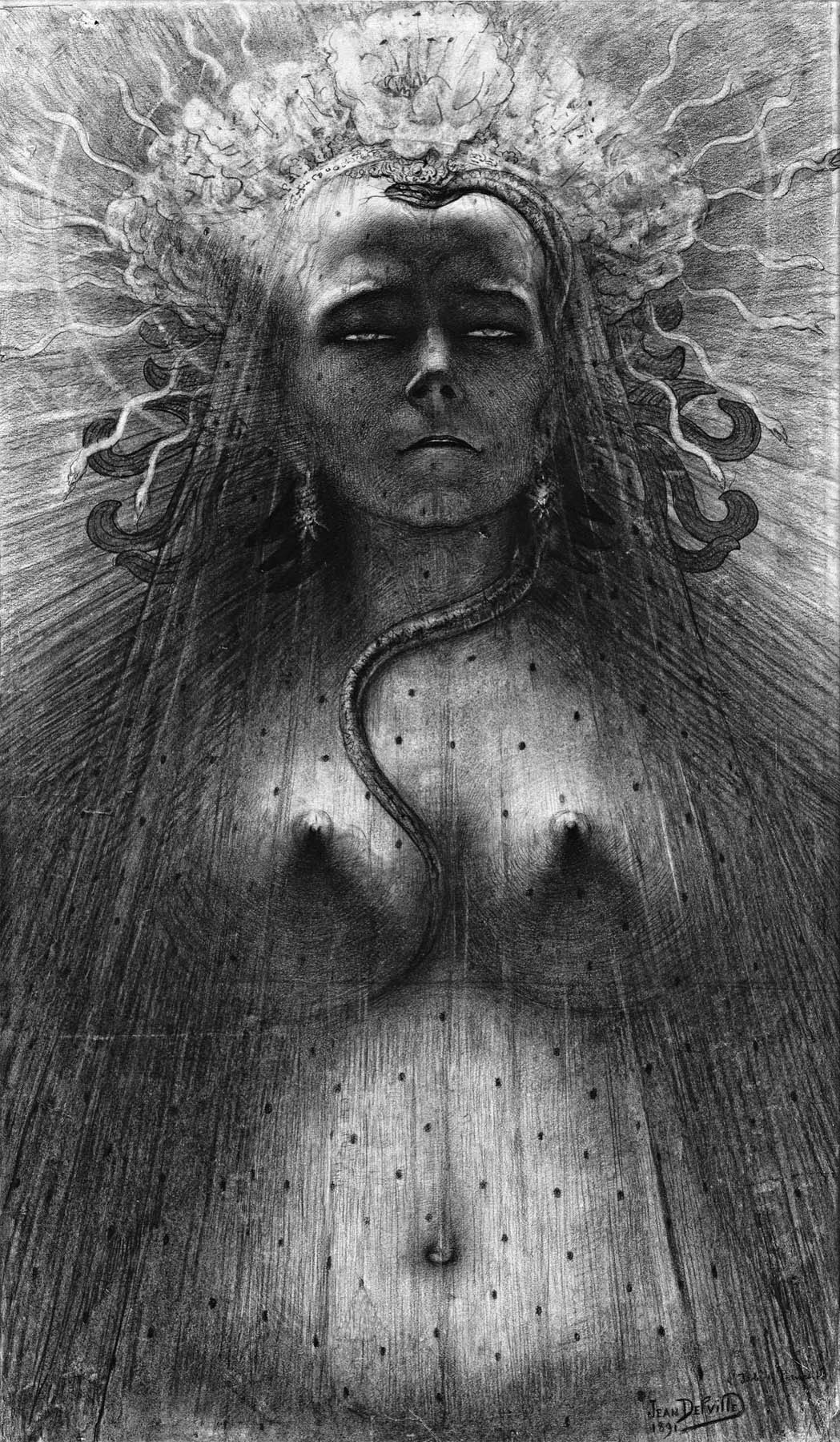

Jean Delville (Belgium, 1867-1953)

L’Idole de la Perversité (The Idol of Perversity)

1891

81.5 x 48.5cm

Museum Wiesbaden, Collection Ferdinand Wolfgang Neess

Eugène Grasset (French, 1845-1917)

Trois Femmes et Trois Loups

1892

Pencil, watercolour, Indian ink and gold highlights on paper

35.3 x 27.3cm

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

Franz von Stuck (German, 1863-1928)

Le Péché (Die Sünde) (The Sin)

1893

Zurich, galerie Katharina Büttiker

© Galerie Katharina Büttiker, Zürich

Franz Stuck (German, 1863-1928)

The Kiss of the Sphinx (Le Baiser du Sphinx) (Der Kuss der Sphinx)

1895

Collection particulière

© Droits réservés

Franz Ritter von Stuck (February 23, 1863 – August 30, 1928), born Franz Stuck, was a German painter, sculptor, printmaker, and architect. Stuck was best known for his paintings of ancient mythology, receiving substantial critical acclaim with The Sin in 1892. In 1906, Stuck was awarded the Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown and was henceforth known as Ritter von Stuck.

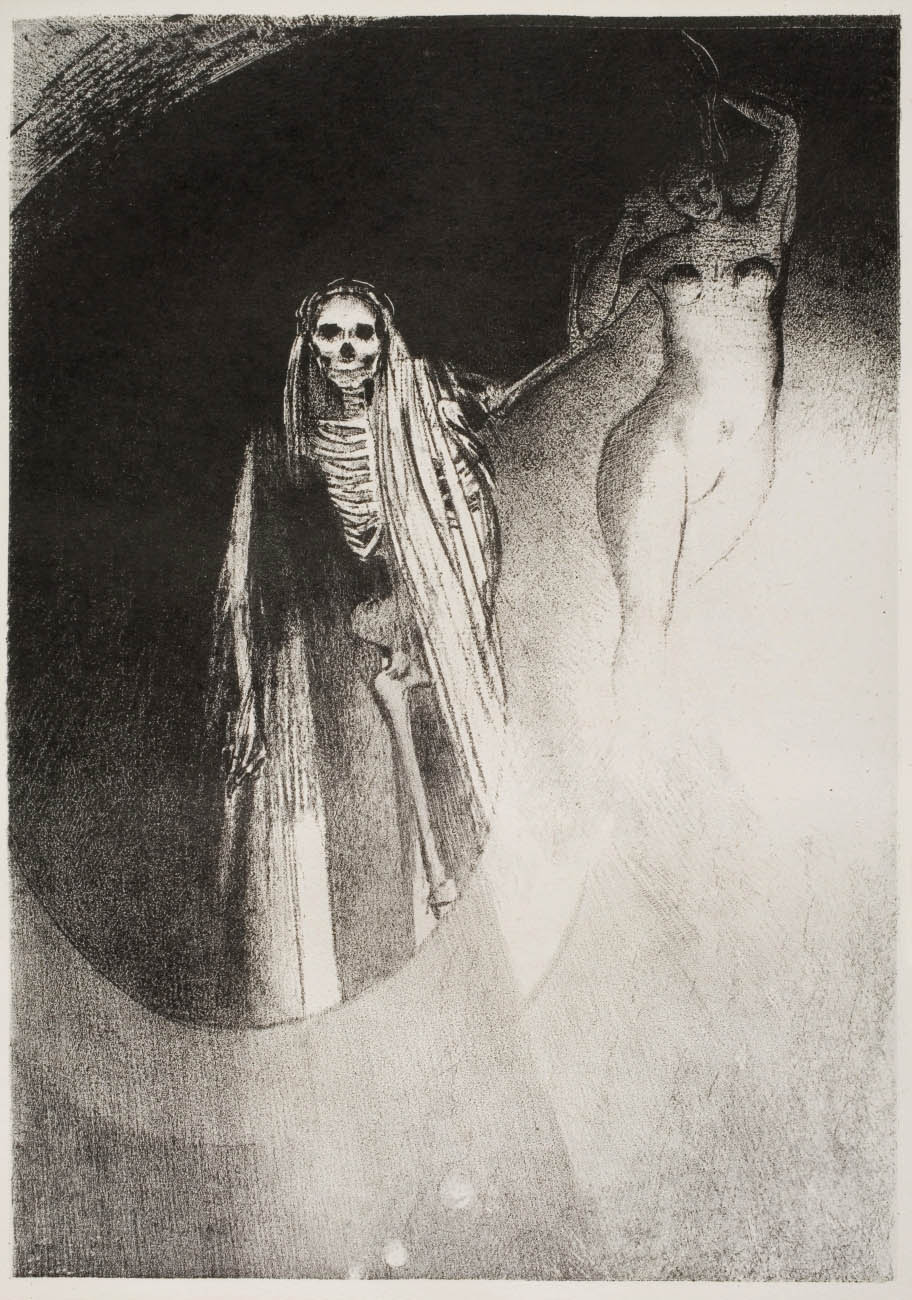

Odilon Redon (French, 1840-1916)

La Mort: C’est moi qui te rends sérieuse: Enlaçons-nous (Death: It is I who Makes You Serious; Let Us Embrace)

1896

Plate 20 from the series “La Tentation de Saint-Antoine” (The Temptation of Saint Anthony)

Lithograph

Sheet: 17 1/8 in. x 13 in. (43.5 x 33cm)

La Mort: C’est moi qui te rends sérieuse: Enlaçons-nous is one of twenty-four prints by the French artist Odilon Redon (1840-1916) that illustrated Flaubert’s play Temptation of Saint Anthony, a lesser-known work of the literary giant but one that Flaubert laboured on painstakingly throughout his life. A contemporary to Flaubert, Redon had worked in lithography for about two decades when the final version of Temptation of Saint Anthony was published. Already working with a repertoire of dark and absurd subjects, Redon was drawn to the grotesque characters described by Flaubert and wrote fondly of the play, calling it “a literary marvel and a mine for me.”

La Mort depicts a scene in the play where Death and Lust, disguised respectively as an emaciated old woman and a fair young one, reveal their real likenesses after failed attempts to seduce Saint Anthony:

The winding-sheet flies open, and reveals the skeleton of Death. The robe bursts open, and presents to view the entire body of Lust, which has a slender figure, with an enormous development behind, and great, undulating masses of hair, disappearing towards the end.

Death tries to lead Saint Anthony to step into the abyss under the cliff and take his own life, thereby ending all pain. “It is I who make you serious, let us embrace each other,” she says, telling Saint Anthony that, by destroying himself, a work of God, he will become God’s equal.

Redon’s accomplished use of chiaroscuro, the sharp contrast between light and dark, underscores the dramatic nature of this moment. Death’s winding-sheet is enveloped by the dazzling rays of light radiating from the voluptuous body of Lust, and Lust’s hair vanishes into the darkness that seeps through Death;s skeletal body. Although the appearance of Lust differs greatly from that of Death, the overlap of their bodies suggests that they are but different phantoms created by the Devil.

Ningyi Xi. “Odilon Redon,” on the Davis Museum website 2017 [Online] Cited 11/08/2024

Arnold Böcklin (Swiss, 1827-1901)

Shield with Gorgon’s head (Bouclier avec le visage de Méduse)

1897

Papier-mâché

610 x 610cm

© RMN (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Carlos Schwabe (Swiss, 1866-1926)

La Mort et le fossoyeur (Death and the Gravedigger)

1900

Paris, musée d’Orsay, conservé au département des Arts Graphiques du musée du Louvre

Legs Michonis, 1902

© RMN (Musée d’Orsay) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi / Patrice Schmidt

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle (French, 1873-1961)

Crâne aux yeux exorbités et mains agrippées à un mur (Skull with bulging eyes and hands gripping a wall)

1902

Pencil and charcoal mounted on a sheet blackened with charcoal

Paris, musée d’Orsay, conservé au département des Arts Graphiques du musée du Louvre

Don de Mme Fourier en souvenir de son fils, 1995

© DR – RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Anonymous photographer

Photographie spirite (médium et spectres) / Spiritual photography (medium and ghosts)

c. 1910

Musée d’Orsay

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski / DR

Paul Dardé (French, 1888-1963)

Eternelle douleur (Eternal Pain)

1913

Plaster, direct carving

50cm

Musée de Lodève

Paul Dardé created Eternal Pain at 25, even though he had only just finished his year of training. Having gone through the Paris National School of Beaux-Arts and Rodin’s workshop, it is probably his journey to Italy and his mythological reading which fixed the theme of the Medusa in the mind of the artist. Carved from a block of plaster gleaned on the heights of Lodève, the piece would be exhibited seven years later side by side with the great Faun, at the Salon of French artists in 1920.

Text from the Musée de Lodève website

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Vampire

1916-1918

Oil on canvas

85 x 110cm

Collection Würth

Photo: Archiv Würth

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2012

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (German, 1888-1931)

Nosferatu – A Symphony of Horror

Germany 1922

Filmstill

Silent film

© Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung

Roger Parry (French, 1905-1977)

Untitled

1929

Illustration from Léon-Paul Fargue’s “Banalité” (Paris 1930)

Gelatin silver print

21.8 x 16.5cm

Collection Dietmar Siegert

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2012

Jacques-André Boiffard (French, 1902-1961)

Renée Jacobi

1930

Paris, Centre Pompidou, musée national d’Art moderne, Centre de création industrielle

© Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Image: Centre Pompidou MNAM-CCI © Mme Denise Boiffard

Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975)

La Poupée (tête et couteau) / The Doll (head and knife)

1935

Collection Dietmar Siegert

© ADAGP, Paris

René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967)

Sentimental Conversation

1945

Oil on canvas

54 x 65cm

Private Collection

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2012

Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie

Schaumainkai 63, 60596 Frankfurt

Phone: +49(0)69-605098-170

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Wednesday, Friday – Sunday 10 – 18 h

Thursday 10 – 21 h

Monday closed

You must be logged in to post a comment.