Exhibition dates: 26th October, 2014 – 11th January, 2015

Curators: Alison Fisher (Art Institute of Chicago), Katherine A. Bussard (Princeton University Art Museum), and Greg Foster-Rice (Columbia College, Chicago

Bruce Davidson (American, b. 1933)

Untitled, fromEast 100th Street

1966-1968

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York and Magnum Photos

What looks to be another fascinating exhibition. They are coming thick and fast at the moment, it’s hard to keep up!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Art Institute of Chicago for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The American city of the 1960s and 1970s experienced seismic physical changes and social transformations, from urban decay and political protests to massive highways that threatened vibrant neighbourhoods. Nowhere was this sense of crisis more evident than in the country’s three largest cities: New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Yet in this climate of uncertainty and upheaval, the streets and neighbourhoods of these cities offered places where a host of different actors – photographers, artists, filmmakers, planners, and activists – could transform these conditions of crisis into opportunities for civic discourse and creative expression.

The City Lost and Found is the first exhibition to explore this seminal period through the emergence of new photographic and cinematic practices that reached from the art world to the pages of Life magazine. Instead of aerial views and sweeping panoramas, photographers and filmmakers turned to in-depth studies of streets, pedestrian life, neighbourhoods, and seminal urban events, like Bruce Davidson’s two-year study of a single block in Harlem, East 100th Street (1966-68). These new forms of photography offered the public a complex image of urban life and experience while also allowing architects, planners, and journalists to imagine and propose new futures for American cities.

Drawn from the Art Institute’s holdings, as well as from more than 30 collections across the United States, this exhibition brings together a large range of media, from slideshows and planning documents to photo collage and artist books. The City Lost and Found showcases important bodies of work by renowned photographers and photojournalists such as Thomas Struth, Martha Rosler, and Barton Silverman, along with artists known for their profound connections to place, such as Romare Bearden in New York and ASCO in Los Angeles. In addition, projects like artist Allan Kaprow’s Chicago happening, Moving, and architect Shadrach Wood’s hybrid plan for SoHo demonstrate how photography and film were used in unconventional ways to make critical statements about the stakes of urban change. Blurring traditional boundaries between artists, activists, planners, and journalists, The City Lost and Found offers an unprecedented opportunity to experience the deep interconnections between art practices and the political, social, and geographic realities of American cities in the 1960s and 1970s.

Organiser

The City Lost and Found: Capturing New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, 1960-1980 is organised by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Princeton University Art Museum.

Text from the Art Institute of Chicago website

James Nares (British, b. 1953)

Pendulum

1976

Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York

James Nares’s film Pendulum illustrates the extraordinary status of Lower Manhattan during the 1970s, where disuse and decay created both the threat of demolition and the freedom to produce ambitious public art projects. The film shows a large pendulum swinging languidly in largely abandoned streets, suggesting the passage of time as well as the menace of the wrecking ball. Nares created this project by suspending a cast-concrete ball from an elevated pedestrian bridge on Staple Street on the Lower West Side adjacent to his loft. Unlike many neighbourhoods, urban renewal plans never came to fruition for this area, which still retains a connection to this precarious, yet liberating time in New York.

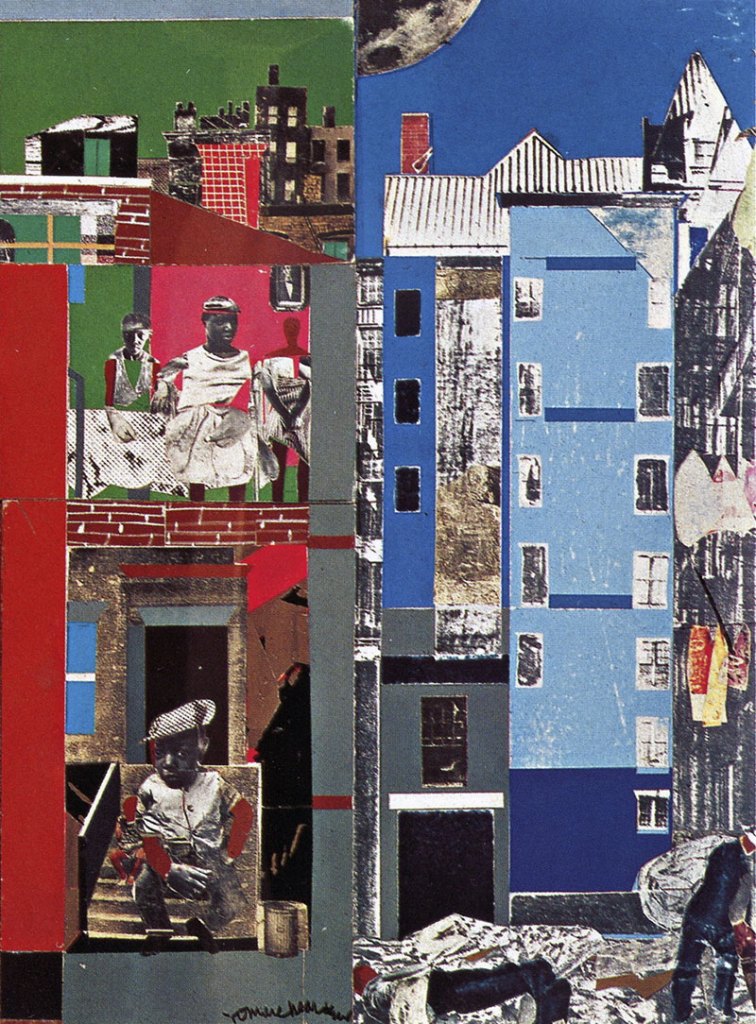

Romare Bearden (African-American, 1911-1988)

The Block II (detail)

1972

Collection of Walter O. and Linda J. Evans

This monumental collage depicts both a specific, identifiable block in Harlem and also the importance of everyday routines to the city. From the 1960s Romare Bearden used collage to convey the texture and dynamism of urban life, combining paint and pencil with found photographs and images from newspapers, magazines, product labels, and fabric and wallpaper samples. Here Bearden showed the diverse inhabitants of Harlem apartment buildings perched in windows and on fire escapes, sitting on front stoops and street benches. The scene highlights the innumerable ways city dwellers “make do” so that their environments are more functional and liveable, from transforming front steps into a living room to turning sidewalks into playgrounds. While Bearden’s work has strong connections to avant-garde art and American and African histories, his collage technique can also be seen as a form of making do, just like the practices of his neighbours in New York.

“The American city of the 1960s and ’70s witnessed seismic physical changes and social transformations, from shifting demographics and political protests to the aftermath of decades of urban renewal. In this climate of upheaval and uncertainty, a range of makers – including photographers, filmmakers, urban planners, architects, and performance artists – countered the image of the city in crisis by focusing on the potential and the complexity of urban places. Moving away from the representation of cities through aerial views, maps, and sweeping panoramas, new photographic and planning practices in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles explored real streets, neighbourhoods, and important urban events, from the Watts Rebellion to the protests surrounding the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. These ideas and images defined not only cities’ social and political stakes in the eyes of the American public, but they also led a new generation of architects, urban planners, and sociologists to challenge long-held attitudes about the future of inner-city neighbourhoods.

Works throughout the exhibition describe this new ideal of urban experience following three main lines of inquiry – preservation, demonstration, and renewal. The first reflects the widespread interest in preserving urban neighbourhoods and communities, including the rise of the historic preservation movement in the United States. The second captures the idea of demonstration in the broadest sense, encompassing political protests during the 1960s, as well as temporary appropriations of streets and urban neighbourhoods through performance art, film, and murals. The third, renewal, presents new and alternative visions for the future of American cities created by artists, filmmakers, architects, and planners. Together these works blur the lines between artists, activists, and journalists, and demonstrate the deep connections between art practices and the political, social, and geographic realities of American cities in a tumultuous era.”

New York

The election of Mayor John Lindsay in 1965 represented a watershed for New York, as the city moved away from administrator Robert Moses’s highly centralised push for new infrastructure and construction in previous decades. Lindsay’s efforts to create a more open and participatory city government were often in dialogue with ideas advanced by critic Jane Jacobs, who argued for the value of streets, neighbourhoods, and small-scale change. This new focus on local and self-directed interventions had a wide influence, leading to the development of pocket parks to replace vacant lots and the groundbreaking Plan for New York City’s use of photo essays and graphic design to express goals of diversity and community. In turn, many artists of the period, including Hans Haacke and Mierle Laderman Ukeles, created work that directly engaged with important social and political issues in the city, such as slum housing and labor strikes.

A multifaceted theme of preservation comes to the fore in work by the many artists and architects in New York who documented, staged, and inhabited areas where buildings were left vacant and in disrepair following postwar shifts in population and industry. The historic streets of Lower Manhattan became an integral part of projects by artist Gordon Matta-Clark and architect Paul Rudolph, for example, while low-income, yet vibrant neighbourhoods like Harlem gave rise to important bodies of work by Romare Bearden, Bruce Davidson, and Martha Rosler. James Nares’s elegiac film Pendulum and Danny Lyon’s remarkable photographs in The Destruction of Lower Manhattan are examples of a growing awareness of the struggle to preserve the existing urban fabric and cultures of New York during the 1960s and ’70s.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles (American, b. 1939)

Touch Sanitation Performance

1977-1980

Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

In 1977 Mierle Laderman Ukeles embarked on the multiyear performance piece Touch Sanitation, in which she shook the hand of every one of the 8,500 sanitation workers, or “sanmen,” employed by the city of New York, in keeping with her practice’s focus on labor. After the vilification of sanitation workers during the strikes of 1968, Ukeles’s personal and political camaraderie with the workers took on particular importance; every handshake was accompanied by the words “Thank you for keeping the city alive.” She worked the same hours as the sanmen and followed their paths through the streets of New York. Touch Sanitation was also distinguished by the importance Ukeles placed on the participation of the workers, as she explained in the brochure for the project: “I’m creating a huge artwork called TOUCH SANITATION about and with you, the men of the Department. All of you.”

Paul Rudolph (American, 1918-1997)

Lower Manhattan Expressway, New York City, perspective section

c. 1970

The Paul Rudolph Archive, Library of Congress

Known for high-tech buildings in concrete, architect Paul Rudolph began working on a project for Lower Manhattan Expressway in 1965, funded by the Ford Foundation as research and design exploring “New Forms of the Evolving City.” Rudolph diverged from Robert Moses’s strategy for infrastructural projects through a sensitive engagement with the scale and texture of the dense urban fabric of Lower Manhattan. He proposed a below-grade road surmounted by a large, continuous residential structure of varying heights that would protect the surrounding neighbourhood from the pollution and noise of the highway. In many places this terraced megastructure was precisely scaled to the height of the surrounding loft buildings, with entrances and gardens on existing streets, a contextual quality emphasised in his detailed drawings. Rudolph also designed the expressway complex to resonate with established functions and symbols of the city, with tall buildings flanking the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges like monumental gates to the city.

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

Crosby Street, New York, Soho

1978

© Thomas Struth

Thomas Struth’s 1978 photographs in the series Streets of New York City are remarkable representations of a city undergoing dramatic change, from the derelict streets of Lower Manhattan and public-housing buildings in Harlem to the dazzling, mirage-like towers of the newly built World Trade Center. Struth produced these photographs during a residency at the New York Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Inc. (now MoMA’s PS1) from December 1977 until September 1978. As he would later write, “I was interested in the possibility of the photographic image revealing the different character or the ‘sound’ of the place. I learned that certain areas of the city have an emblematic character; they express the city’s structure.” Although these photographs adopt the symmetrical framing and deadpan documentary style of his mentors Bernd and Hilla Becher, they led Struth to ask, “Who has the responsibility for the way a city is?”

Chicago

In the 1960s and ’70s Chicago emerged from its industrial past led by a powerful mayor, Richard J. Daley, who prioritised development in the downtown areas. His work to modernise the city resulted in the construction of massive highways, housing projects, and imposing skyscrapers – new architectural and infrastructural icons that were explored by many photographers of the era. The arts experienced a similar boom, with the foundation and expansion of museums and university programs. Growth came at a cost, however, and the art of this period highlights the disparate experiences of local communities in Chicago, including Jonas Dovydenas’s photographs of life in ethnic neighbourhoods and independent films exploring issues ranging from the work of African American community activists to the forced evictions caused by urban renewal projects.

Demonstrations loomed large in Chicago, where artists responded to two major uprisings in 1968, the first on the West Side, following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and the second downtown, during the Democratic National Convention. These violent confrontations between protestors and police drew national attention to issues of race relations and political corruption in Chicago and led to an outpouring of new art projects as forms of demonstration, including community murals like the West Wall and an exhibition at the Richard Feigen Gallery condemning Daley’s actions during the DNC. The image of Chicago that emerged in the mass media of this period was one of destruction and resilience, a duality highlighted by contemporary artists like Gordon-Matta Clark and Allan Kaprow, whose work existed in the fragile space of opportunity between the streets and the wrecking ball.

Ken Josephson (American, b. 1932)

Chicago

1969

The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Still from Lord Thing, directed by DeWitt Beall

1970

Courtesy Chicago Film Archives

Lord Thing documents the development of the Vice Lords from an informal club for young men on the streets of Chicago’s West Side, its emergence as a street gang, and its evolution into the Conservative Vice Lords, a splinter group that aspired to nonviolent community activism. The film uses a mix of black-and-white sequences to retrospectively analyse the group’s violent middle period and contrasts these with colour sequences that show the Conservative Vice Lords fostering unity and developing black-owned businesses and social programs during the late 1960s. Together, Lord Thing argues for the agency of African Americans in the face of decades of spatialised oppression in Chicago.

Art Sinsabaugh (American, 1924-1983)

Chicago Landscape #117

1966

Art Sinsabaugh Archive, Indiana University Art Museum

© 2004 Katherine Anne Sinsabaugh and Elisabeth Sinsabaugh de la Cova

Sinsabaugh’s panoramic photographs are among the most distinctive visual records of Chicago, capturing the built landscape with what Sinsabaugh called “special photographic seeing,” achieved with large-format negatives. The Department of City Planning used his photographs in a 1963 planning document to help describe the qualities of Chicago’s tall buildings “as vertical forms contrasting with these two great horizontal expanses [the flat prairie and the lakefront edge].” Sinsabaugh’s panoramas also flirt with abstraction when depicting such remarkable places as Chicago’s Circle Interchange, a monumental coil of highways completed in the early 1960s. Sinsabaugh recalled that for the photographer, like the motorist, freeways provided “an access, an opening, a swath cut right through the heart of the City in all directions.” However, his early thrill at the novelty of these developments soon gave way to an appreciation of their violence, in which entire “neighbourhoods were laid bare and their very bowels exposed.” (Please enlarge by clicking on the image)

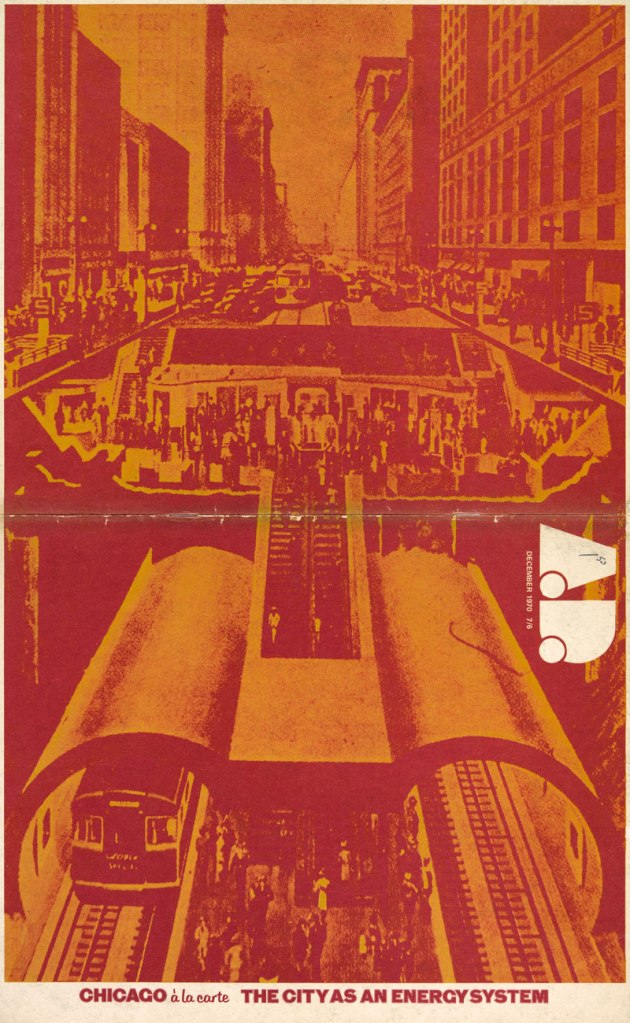

Alvin Boyarsky (Polish-Canadian, 1928-1990)

Chicago à la Carte: The City as Energy System

1970

Special issue of Architectural Design, December 1970

Courtesy Alvin Boyarsky Archive, London

The concept of the city as organism emerged during the 1960s as a response to the increasingly complex interconnections of technology, communication, and history. One exceptional project in this vein was the British architect Alvin Boyarsky’s Chicago à la Carte. Boyarsky drew on an archive of historical postcards, newspaper clippings, and printed ephemera to trace a hidden history of Chicago’s built environment as an “energy system.” This idea was represented on the cover by a striking postcard image of a vivisection of State Street in the Loop, showing subway tunnels, sidewalks, El tracks, and skyscrapers in what Boyarsky described as “the tumultuous, active, mobile, and everywhere dynamic centre of a vast distribution system.” On other pages, Boyarsky showed images of Chicago’s newly built skyscrapers with newspaper clippings of recent political protests to juxtapose the city’s reaction to recent political protests against the disciplinary tradition of modern architecture in Chicago.

Los Angeles

Los Angeles has always been known for its exceptionalism, as a city of horizontal rather than vertical growth and a place where categories of private and public space prove complex and intertwined. During the 1960s and ’70s these qualities inspired visual responses by seminal artists like Ed Ruscha as well as critics like Reyner Banham, one of the most attentive observers of the city during this period. In many other respects, however, Los Angeles experienced events and issues similar to those of New York and Chicago, including problems of racial segregation, a sense of crisis about the decay of its historical downtown, and large-scale demonstrations, with responses ranging from photography and sculpture to provocative new forms of performance art by the collective Asco.

Concerns about the future forms of urbanism in Los Angeles and a renewal of the idea of the city were major preoccupations for artists, architects, and filmmakers. Many photographers focused on the everyday banality and auto-centric nature of the city, such as Robbert Flick’s Sequential Views project and Anthony Hernandez’s Public Transit Areas series. The historic downtown core continued to hold a special place in popular memory as many of these areas – including the former neighbourhood of Bunker Hill – were razed and rebuilt. Julius Shulman’s photographs of new development in the 1960s – including Bunker Hill and Century City – focus on the spectacular quality of recent buildings as well their physical and cultural vacancy. Architects played a strong role in creating new visions for the future city, including an unrealised, yet bold and influential plan for redeveloping Grand Avenue as a mixed-use district shaped by ideals of diversity and pedestrian-friendly New Urbanism.

Julius Shulman (American, 1910-2009)

The Castle, 325 S. Bunker Hill Avenue, Los Angeles, California, (Demolished 1969)

c. 1968

Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10)

© J. Paul Getty Trust. Used with permission

Julius Shulman (October 10, 1910 – July 15, 2009) was an American architectural photographer best known for his photograph “Case Study House #22, Los Angeles, 1960. Pierre Koenig, Architect.” The house is also known as the Stahl House. Shulman’s photography spread the aesthetic of California’s Mid-century modern architecture around the world. Through his many books, exhibits and personal appearances his work ushered in a new appreciation for the movement beginning in the 1990s.

His vast library of images currently resides at the Getty Center in Los Angeles. His contemporaries include Ezra Stoller and Hedrich Blessing Photographers. In 1947, Julius Shulman asked architect Raphael Soriano to build a mid-century steel home and studio in the Hollywood Hills.

Some of his architectural photographs, like the iconic shots of Frank Lloyd Wright’s or Pierre Koenig’s remarkable structures, have been published countless times. The brilliance of buildings like those by Charles Eames, as well as those of his close friends, Richard Neutra and Raphael Soriano, was first brought to wider attention by Shulman’s photography. The clarity of his work added to the idea that architectural photography be considered as an independent art form in which perception and understanding for the buildings and their place in the landscape informs the photograph.

Many of the buildings photographed by Shulman have since been demolished or re-purposed, lending to the popularity of his images.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Asco

Decoy Gang War Victim

1974 (printed later)

Photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr.

Courtesy of Harry Gamboa Jr.

The Chicano art collective Asco was famous for their No Movies – works that appropriate certain stylistic qualities of the movies while maintaining a nonchalance that allows them to critique the media industry’s role in Los Angeles. Asco’s performances, therefore, function on different registers to engage with current events and issues facing the Chicano community as well as acknowledge the mainstream media’s distorted image of the city. For Decoy Gang War Victim, Asco’s members staged a fake gang shooting then circulated the images to local television stations, simultaneously feeding and deriding the media’s hunger for sensationalist imagery of urban neighbourhoods.

William Reagh (American, 1911-1992)

Bunker Hill to soon be developed

1971 (printed later)

Los Angeles Public Library

From 1939 to 1990, William Reagh produced over 40,000 photographs of Los Angeles in considerable architectural detail. Reagh is also well known for his specific efforts to document the Downtown area from the 1950s to the 1980s. His collection is now part of the California State Library, and a photography center in his name, the William Reagh Los Angeles Photography Center, is located at 2332 W. Fourth Street.

The William Reagh Los Angeles Photography Center is operated by Grupo de Teatro SINERGIA in partnership with the Department of Cultural Affairs City of Los Angeles, and is the only Community Photography Laboratory in the Los Angeles area.

Reagh was on the streets: Looking. Lingering. Documenting. He walked Los Angeles and consequently saw Los Angeles — offering a different perspective than the mere suggestion of place so often gleaned in motion or generalised shorthand. He circled neighbourhoods, returned to some locations year after year, charting their evolution. And though, until his death in 1992, he became one of Los Angeles’ most prolific visual documentarians, he didn’t set out to be a photographer, nor was his trove of L.A. images meant to be a formal paean to Los Angeles. A painter and philosopher, by training and inclination, photography was something that he “picked up,” while in the service, a proficiency, that overtime became, at turns, poetic – though he, says his son, would never see it as such. …

His father’s arrival in Los Angeles, coincided with the city’s most vigorous years of growth, as well as its many phases of urban renewal. For years, his day job was work as a commercial photographer – shooting products, catalogues, art collections “whatever the clients called for,” his son recalls. But the weekends were dedicated to solely to prowling Los Angeles, uncovering and documenting its very disparate parts, assembling a sense of the whole.

To say there was a goal, a plan or even an organising thesis to his images, would be to overstate his process, Patrick suggests. His father, he says, was a wanderer who would lose himself within the intricate folds of the city, “wherever his muse led him.” Patrick remembers the meanderings of his father. “He just loved to wander downtown and walk around the streets and shoot. Sometimes it might be a streetscape, sometimes it might be people. He’d often shoot from the hip, hold the camera low. He was very good at taking pictures of people without them knowing. But really, he was so non-threatening, such a friendly guy – even in the seediest of neighbourhoods – he would make everyone feel at ease.”

While Saturdays often meant a solo trek – perhaps crisscrossing the freeways by car, touring surface streets on foot for inspiration – on Sundays, Reagh might take Patrick and his sister along. It was an opportunity to see the city through his eyes – the places he felt were important to document, even if he couldn’t articulate why in words. “Train yards, he loved. Shipyards. Amusement parks, the Pike and Pacific Ocean Park,” Reagh recalls. These were places at the edge of things – of the city or the coastline – and, metaphorically, our imaginations. The transit hubs in particular provided an interesting opportunity to see behind the scenes – an end on one story, beginning of another.

Each setting called for a different set up. “If he was downtown shooting people, he’d have his reflex, or another smaller camera, maybe his Leica. At the train yard or shipyard, he’d bring his tripod and set up his big Speed-Graphic. Back then there were no security guards asking questions: who you were and what you were doing. I would climb on stuff, those piled up streetcars. There was broken glass all over. He’d be off shooting. I’d climb. Back when you could do that sort of thing.” …

Decades later, the work reveals his heart. And what the images, taken as a whole, most eloquently preserve is not just sense of place, but a sense of the city’s humanity, its particular vernacular – its feel, pace, space; its leisureliness, and idiosyncratic visual language. “He was just interested in the passing parade.” says Reagh, “He let the camera do the talking.”

Lynell George. “Sidewalk Stories: The Photography of William Reagh,” on the KCET website January 10, 2013 [Online] Cited 26/11/2022. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

John Humble (American, b. 1944)

300 Block of Broadway, Los Angeles, October 3, 1980

1980

Courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica

Brought up in a military family, John Humble spent his childhood moving around the country from one military base to another. Humble was drafted during the Vietnam War, then became a photojournalist for the Washington Post before pursuing a graduate degree at the San Francisco Art Institute. His itinerant nature continued when he traveled the world in the early 1970s, going from Europe to the Middle East, then to Africa and Asia in his Volkswagen van. However, since the summer of 1974 Humble has lived in one place: Los Angeles. His traveling instinct did not diminish despite his fixed geographical location; rather, it intensified as he traversed the length and breadth of the city (from the San Fernando Valley and East Los Angeles to Venice and the shores of Long Beach), creating images that explore the postmodern qualities of America’s second largest city. Humble’s desire to capture “the incongruities and ironies of the Los Angeles landscape” results in a compelling body of work where power lines cut across blue skies, freeways divide neighbourhoods and a river bisects the city.

Humble began working with a 35mm camera, favouring black-and-white prints, but in September 1979 he bought his first view camera and switched to colour printing, producing first Cibachrome, then chromogenic prints. In the 1970s colour emerged within the tradition of photography, most notably in the 1976 exhibition Photographs by William Eggleston at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. No longer confined to the commercial domain of advertising, colour photography gained recognition as a valid expression of fine art. For Humble, the choice was clear; to fully capture the realities of the city – what he refers to as “the urban landscape” – colour was essential.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

The Art Institute of Chicago

111 South Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois 60603-6404

Phone: (312) 443-3600

Opening hours:

Monday, 11.00am – 6.00pm

Tuesday – Wednesday, closed

Thursday, 11am – 9.00pm

Friday, 11am – 9.00pm

Saturday – Sunday, 11.00am – 6.00pm

The museum is closed Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s days.

You must be logged in to post a comment.