Exhibition dates: 18th October, 2024 – 27th May, 2025

Curators: Katja Böhlau and Ludger Derenthal, Kunstbibliothek – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Frontispiece

1921

From Paul Éluard: Répétitions

Print from collage

5.5 x 10.3cm

Sammlung Würth

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

“Although these artists were explicitly not dealing with mundane reality but instead with what lies beneath, behind and in-between, the still relatively new medium of photography was of great importance for many. Last but not least, they also used it to make visible what remains hidden to the naked eye without technical means: the distant, the tiny, the moving.” (Press release)

Expressing the unconscious mind through illogical, dreamlike imagery and ideas, exploring the irrational, challenging notions of reality through a technical instrument – the camera – to create “a rich and multifarious cosmos of idiosyncratic realities that radically transcended traditional aesthetics.”

In the dream of the mind and the camera’s eye. Over and above the real.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museum für Fotografie for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“The invention of modern photomontage in the early twentieth century by Max Ernst with his Dada colleagues Hannah Höch, John Heartfield, George Grosz and Raoul Hausmann established new history in a variety of ways. Expanding modern art with multimedia as well as placing found photographs into art cut from printed magazines, rather than chemical made prints from the darkroom. Redefining final works of art without the paint brush or canvas. Ernst freed imagery into the unconscious by self-made combinations of drawing with torn and pasted photographic fragments, evoking memories and other responses by viewers that continue today.”

Steve Yates, Fulbright scholar, photographic artist, author and curator

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Die chinesische Nachtigall / Le rossignol chinois / The Chinese Nightingale

1920

Collage and ink on paper

15.5 x 9cm

Musée de Grenoble

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

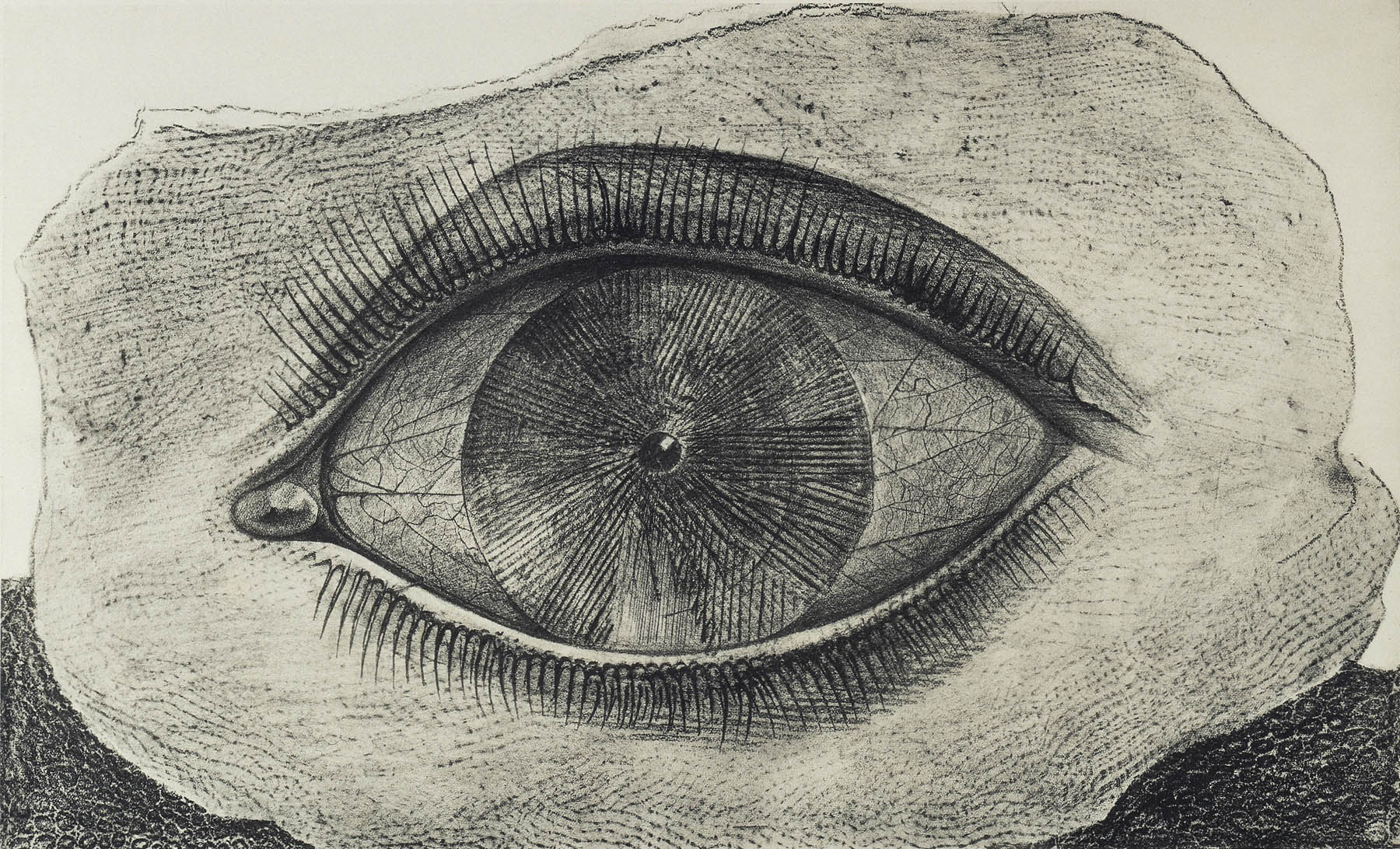

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Lichtrad / la roue de la lumière / The wheel of light

1926

From Histoire Naturelle, sheet 29

Photogravure after frottage

32.5 x 50cm

Sammlung Würth

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Max Ernst, Marie-Berthe Aurenche und Jean Aurenche / Max Ernst, Marie-Berthe Aurenche and Jean Aurenche, Photomaton

c. 1929

Silver gelatin paper

20.9 x 3.7cm

Sammlung Würth

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

“…unter meinem weißen Gewand, in meinem Taubenhaus, werdet ihr nicht mehr arm sein, ihr tonsurierten Tauben. Ich werde euch zwölf Tonnen Zucker bringen. Aber berührt nicht mein Haar“ / “…sous mon blanc vêtement, dans mon colombodrôme, vous ne serez plus pauvres, pigeons tonsurés. Je vous apporterai douze tonnes de sucre. Mais ne touchez pas à mes cheveux!” / “…you won’t be poor anymore, head-shaven pigeons, under my white dress, in my columbarium. I’ll bring you a dozen tons of sugar. But don’t you touch my hair!”

1930

From Das Karmelienmädchen. Ein Traum / Rêve d’une petite fille qui voulut entrer au Carmel / Dream of a little girl who wanted to enter Carmel

Print from collage

7.7 x 11.3cm

Sammlung Würth

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Das Innere der Sicht 3 / A l’intérieur de la vue 3 / Inside View 3

1931/1947

From Paul Éluard : A l’intérieur de la vue. 8 Poèmes visibles

Collage

22.3 x 15.5cm

Sammlung Würth

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Max Ernst (German, 1891–1976)

…des vollständig auf sie beschränkten, des vom Rest der Welt isolierten / … d’absolument limité à eux, d’isolant du reste du monde / of the one who is completely confined to them, isolated from the rest of the world

1936

From André Breton: Le château étoilé

Photogram after frottage

25 x 20cm

Sammlung Würt

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

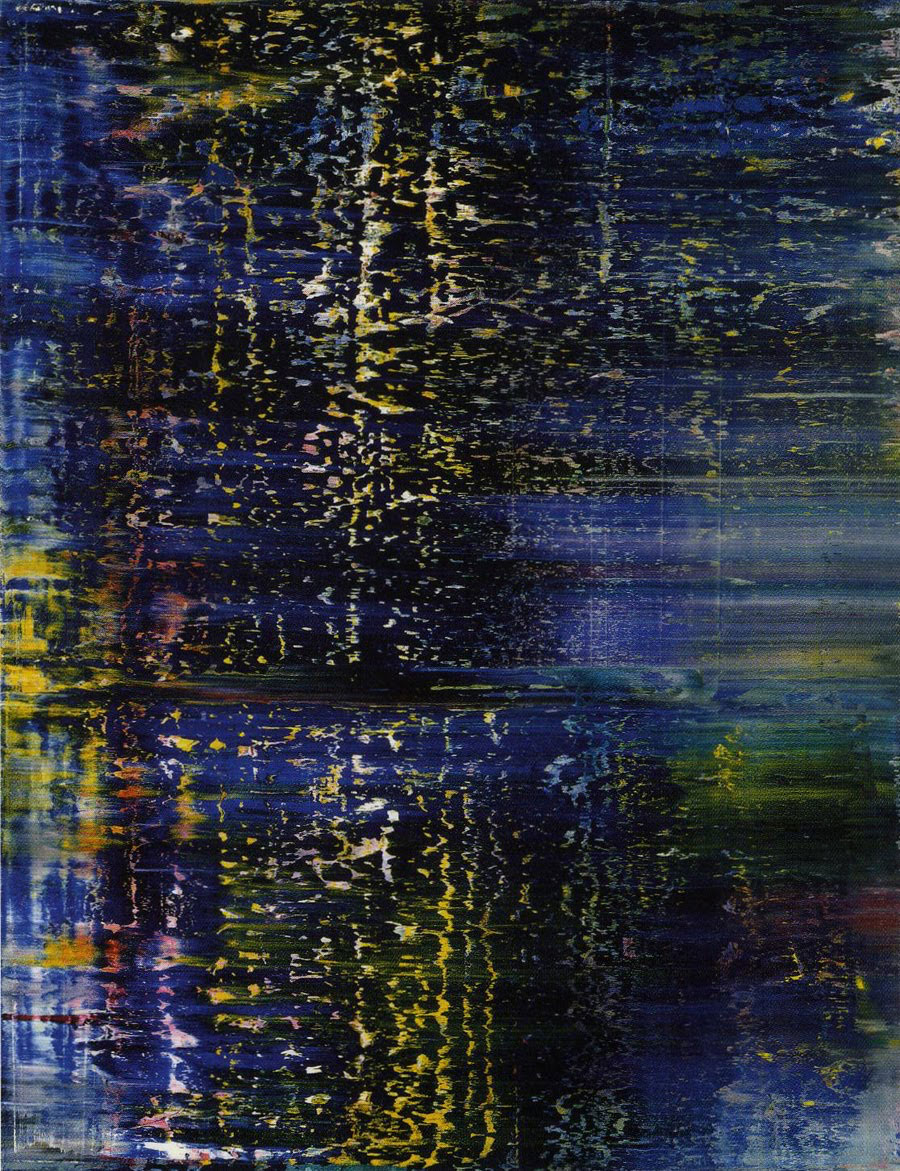

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Eine weitere Laune der Venus / Un autre caprice de Venus / Another whim of Venus

1961

Oil on canvas

27 x 22cm

Sammlung Würth

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

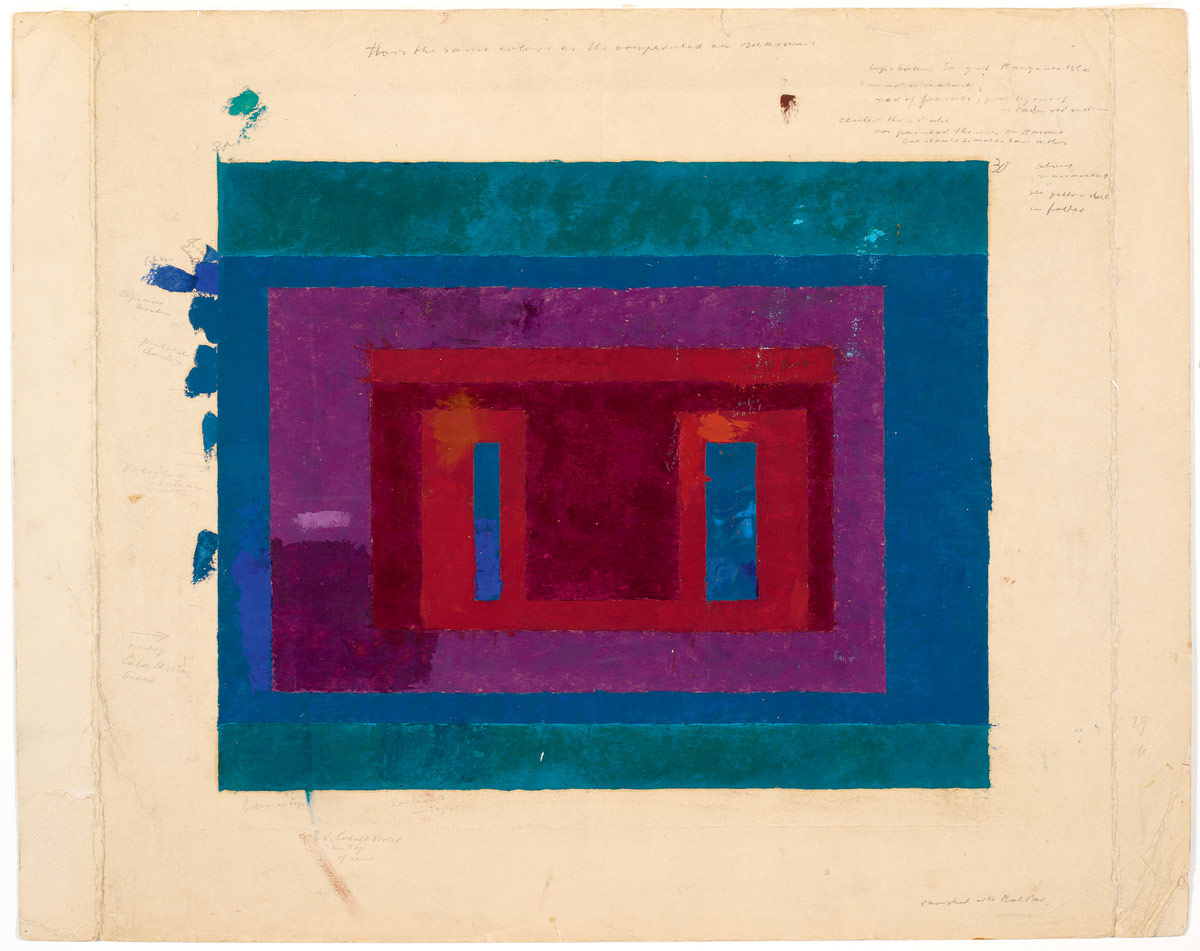

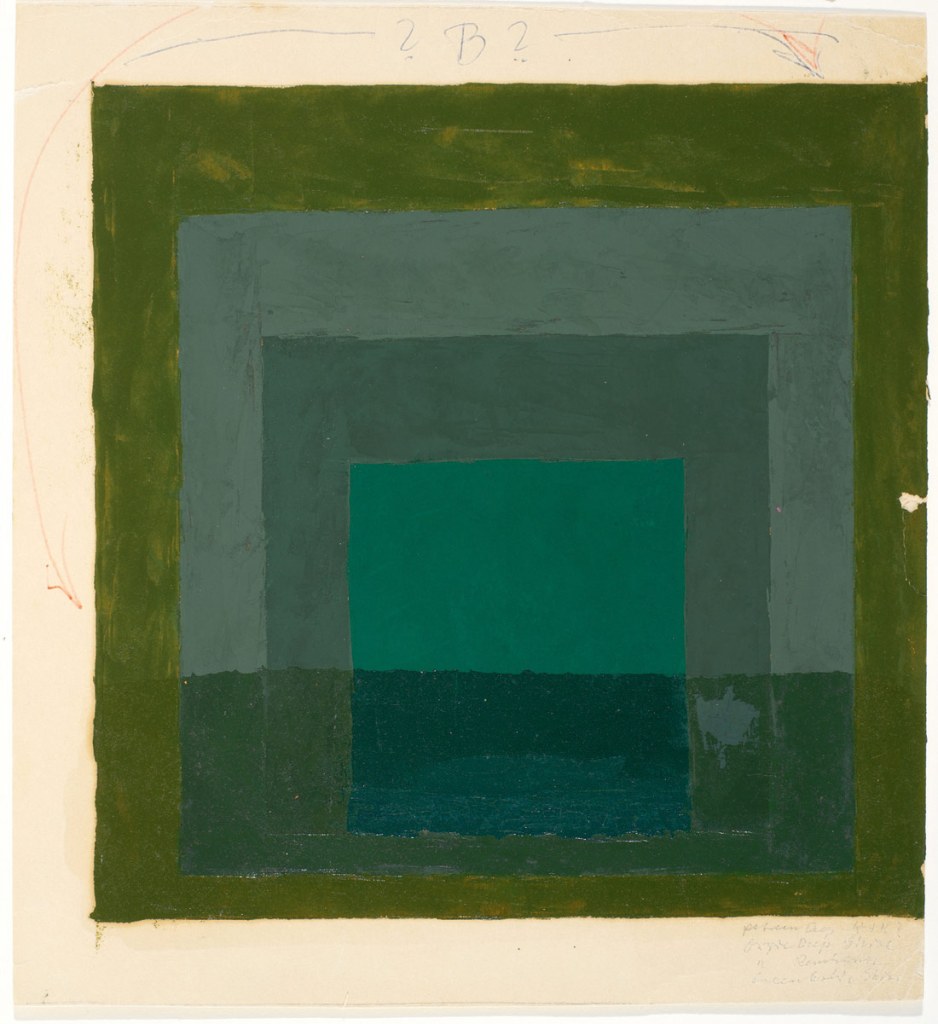

Max Ernst holds a prominent position within Dada and Surrealist Art. His name stands for genre-bending works that combine dream and reality. The exhibition FOTOGAGA: Max Ernst and Photography. A Visit from the Würth Collection is the first to search for points of intersection between his work and photography. Commemorating Surrealism’s centenary, the Museum für Fotografie (Museum of Photography) is showing a representative overview of Max Ernst’s artworks from the Würth Collection. These are complemented by works from the Kunstbibliothek, Kupferstichkabinett, Sammlung Scharf-Gerstenberg and the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, and other exceptional loans from museums and private collections in France and Germany.

Max Ernst and Photography – A Special Connection

The art of Max Ernst (1891-1976) was created at a time characterised by a new, creative approach to photography. Snapshots, scientific photographs and images of war machinery inspired him and served as working materials, especially for his collages. Technical and artistic developments in the medium of photography significantly influenced his work. He used photographic reproduction techniques to increase the visual impact of his works: enlargements allowed his small-format collages to hold their own alongside paintings in exhibitions; the production of photo postcards of the collages ensured that the works could be distributed quickly and easily; and the inversion of the tonal values in a photogram enhanced the effect of his frottages.

Max Ernst himself never used a camera for his art, but he liked to pose for the camera, whether for images taken by well-known photographers or made in photo booths. At times serious, at times a little “gaga”, the portraits illustrate not just the artist’s love for playfulness but also an occasionally strategic use of photography to promote his artistic agenda. The title of the exhibition – “FOTOGAGA” – is derived from a group of works by Hans Arp and Max Ernst, which they called “FATAGAGA”: the “FAbrication de TAbleaux GAsométriques Garantis (Fabrication of Guaranteed Gasometric Images)”. One of these photocollages, in which the two artists address their relationship as friends, can be seen in the exhibition.

A Century of Surrealism

Some 270 works will be exhibited, primarily works on paper but also paintings by Max Ernst and photographs, photograms, collages, and illustrated books by his Surrealist contemporaries. Although these artists were explicitly not dealing with mundane reality but instead with what lies beneath, behind and in-between, the still relatively new medium of photography was of great importance for many. Last but not least, they also used it to make visible what remains hidden to the naked eye without technical means: the distant, the tiny, the moving.

Max Ernst’s works are framed within the context of both contemporary and historical references. There are numerous and surprising parallels to photographs by other artists. An avid delight in experimentation and a creative game played with chance characterise the works selected for the exhibition. Their originators reflected on forgotten photographic processes from the 19th century and developed new techniques using light-sensitive materials. Semi-automatic methods, working with found objects, unusual combinations, and the blurring of traces have equally shaped the work of Max Ernst and the photographic oeuvres of many of his contemporaries and other artists that followed. Even a century after André Breton published the first Surrealist Manifesto on 15 October 1924, they have not lost any of their fascination.

A cooperation with tradition

The Staatliche Museen zu Berlin look back on a longstanding cooperation with the Würth Collection. FOTOGAGA: Max Ernst and Photography is the fourth exhibition in a series that began in 2019‒2020 with Anthony Caro: The Last Judgement Sculpture from the Würth Collection at the Gemä-ldegalerie. It was followed in 2021‒2022 by Illustrious Guests: Treasures from the Kunstkammer Würth in the Kunstgewerbemuseum and David Hockney – Landscapes in Dialogue. “The Four Seasons” from the Würth Collection in 2022, also shown at the Gemäldegalerie. The exhibition at the Museum für Fotografie draws on the Würth Collection’s extensive holdings, especially of Max Ernst’s graphic works, which are now being shown in Berlin for the first time.

Press release from the Museum für Fotografie

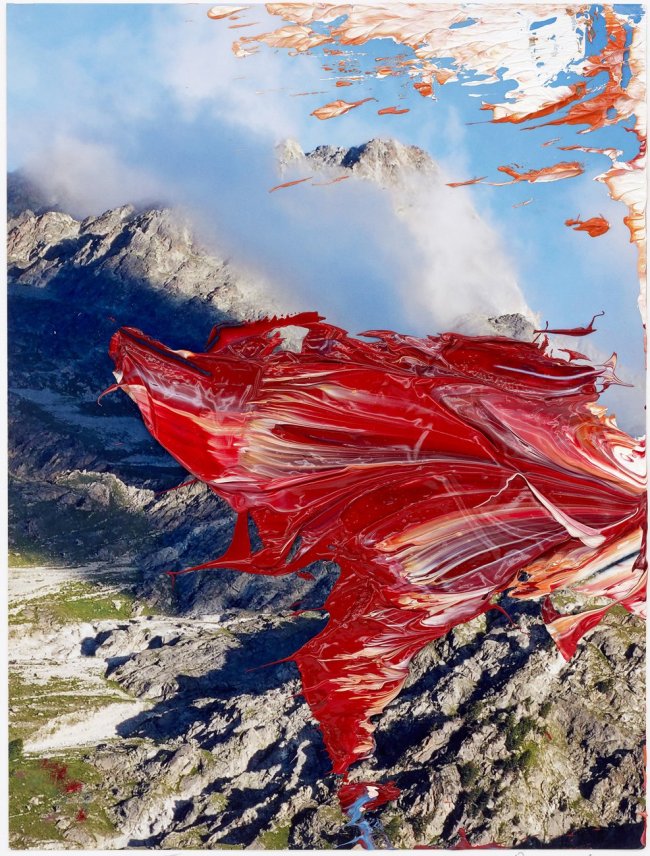

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Above the Clouds Midnight Passes

1920

Photographic enlargement of a collage and ink, facsimile, 2024

73 x 55cm

Kunsthaus Zürich

Public domain

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

The broken marriage

1925

Photomontage

16.5 x 12.2cm

Sammlung Siegert, München

Public domain

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

The Stall of the Sphinx

1925

Pencil on paper

16.4 x 15.2cm

Sammlung Ulla und Heiner Pietzsch, Berlin

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Little Tables around the Earth (Petites tables autour de la terre)

1926

From Natural History (Histoire naturelle)

Collotype of a frottage

50 x 32.5 cm (sheet)

Paris: Éditions Jeanne Bucher

Portfolio with 34 collotypes of frottages

51.7 x 35 x 1cm

Jean Painlevé (French, 1902-1989)

Hummerschere / Pince d’homard, Port-Blanc, Bretagne / Lobster claw, Port-Blanc, Brittany

1929

Silver gelatin paper

23 x 16.7cm

Sammlung Dietmar Siegert

© Archives Jean Painlevé/Les Documents cinématographiques, Paris

Repro: Christian Schmieder

Aenne Biermann (German, 1898-1933)

Cactus

1929

Silver gelatin paper

12.4 x 17.3cm

“The object, which, in its surroundings, is never seen other than in its most mundane aspect, is given new life when isolated in the lens of the viewfinder. […] It seemed to me that the clarity of a constructed form, when removed from its overly distracting surroundings, could be depicted convincingly through the use of photography.”

~ Aenne Biermann

Max Ernst (1891–1976)

Quiétude from The Hundred-Headless Woman

1929

Collage novel with 147 reproductions of collages

Paris: Éditions du Carrefour

25 x 19cm

The Hundred Headless Woman is Ernst’s first collage novel. It features a loosely narrative sequence of uncanny Surrealist collages, made by cutting up and reassembling nineteenth-century illustrations, accompanied by Ernst’s equally strange captions. Ernst’s French title, La Femme 100 têtes, is a double entendre; when read aloud it can be understood as either “the hundred-headed woman” or “the headless woman.” Along with this enigmatic title character, the book marks the introduction of Ernst’s favourite alter ego, Loplop, “the Bird Superior.” Ernst was deeply engaged with illustrated books during the 1930s; in addition to collage novels, he created many etchings and lithographs to complement the poems and stories of Surrealist writers with whom he was closely associated.

Gallery label from Max Ernst: Beyond Painting, September 23, 2017-January 1, 2018 on the MoMA website Nd [online] Cited 31/03/2025

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Loplop presents the members of the Surrealist group

1931

Reproduction of a collage in Le Surréalisme au service de la revolution, No. 4

27.4 x 19.9cm

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) / Marcel Moore (French, 1892-1972)

Aveux non avenus / Disavowals (frontispiece)

1930

Paris: Éditions du Carrefour

Book with 11 heliogravures of collages

22 x 17 x 2.8cm

Sammlung Siegert, München

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Untitled

1931

From Électricité. Dix rayogrammes de Man Ray et un texte de Pierre

Bost, Paris: La Compagnie Parisienne de Distribution d’Électricité

Heliogravure after photogram

Collotype

38.8 x 29.3cm

Kunstbibliothek – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

© Man Ray Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Repro: Dietmar Katz

Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975)

The Doll

1935

Silver gelatin paper

17.5 x 16 cm

Sammlung Siegert, München

Brassaï (British born Germany, 1899-1984)

Night Moth

1935

Reproduction in Minotaure No. 7

31.6 x 24.8cm

Kunstbibliothek

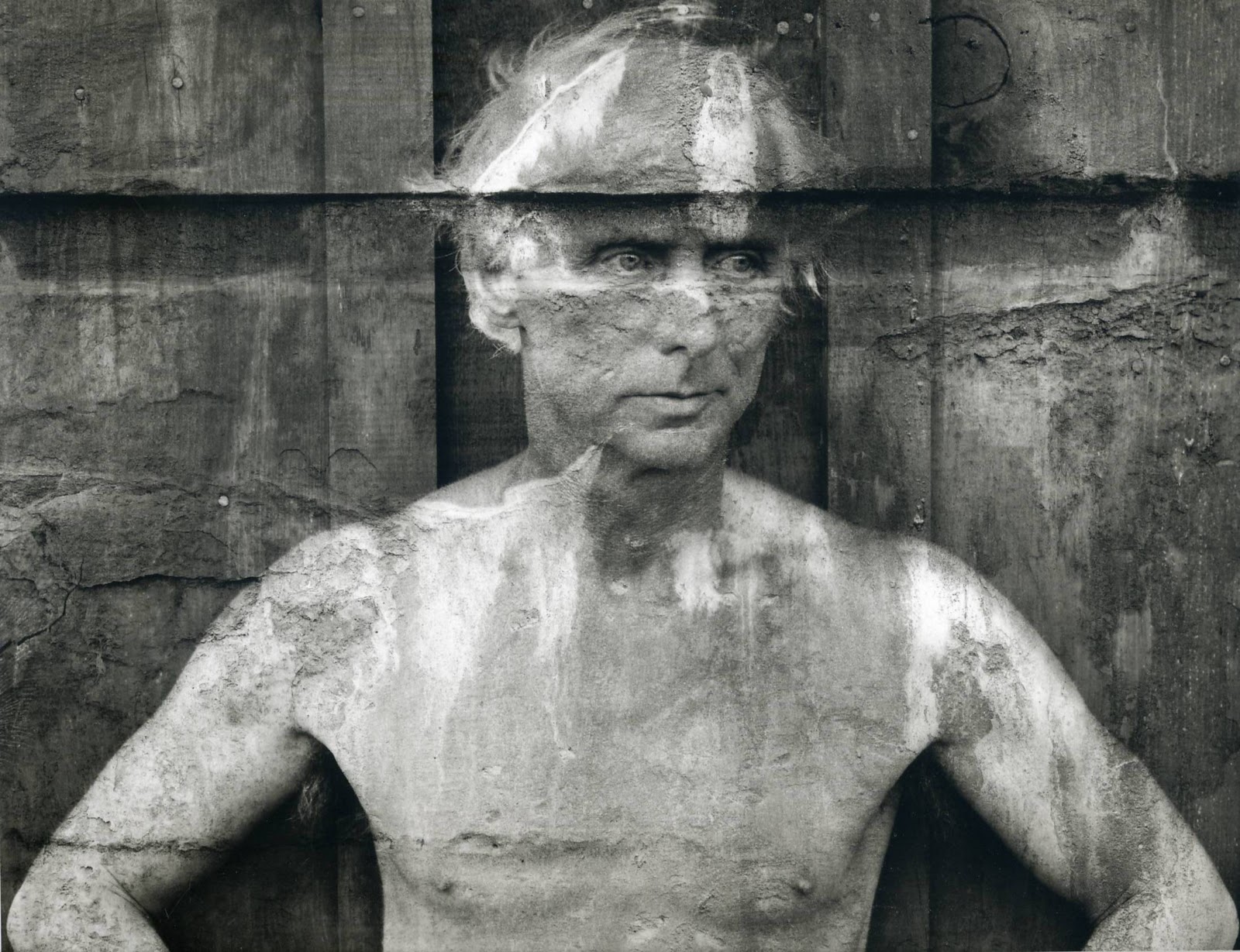

Joseph Breitenbach (German, 1896-1984)

Max Ernst, Paris

1936

Silver gelatin paper

35.3 x 27.8cm

Sammlung Würth

© The Josef and Yaye Breitenbach Charitable Foundation

Raoul Ubac (Belgian, 1910-1985)

The Battle of the Penthesilea II

1937

Photomontage, silver gelatin paper

18 x 24.2cm

Sammlung Siegert, München

Max Ernst (1891-1976) is one of the most important representatives of Dadaism and Surrealism, two artistic movements that turned traditional norms on their head from the 1920s onwards. His boundary-crossing works combine dream and reality. His art also was created at a time characterized by a new, creative approach to photography. Snapshots, scientific photographs and images of war machinery inspired him and served as working materials, especially for his collages. Although he never used a camera for his art himself, technical and artistic developments in the medium of photography significantly influenced his work. Last but not least, Max Ernst liked to pose for the camera, whether for images taken by well-known photographers or made in photo booths.

Some 270 works will be exhibited, primarily works on paper but also paintings by Max Ernst and photographs, photograms, collages, and illustrated books by his Surrealist contemporaries. Although these artists were explicitly not dealing with mundane reality but instead with what lies beneath, behind and in-between, the still relatively new medium of photography was of great importance for many. Last but not least, they also used it to make visible what remains hidden to the naked eye without technical means: the distant, the tiny, the moving.

Max Ernst’s works are framed within the context of both contemporary and historical references. There are numerous and surprising parallels to photographs by other artists. Semi-automatic methods, working with found objects, unusual combinations, and the blurring of traces have equally shaped the work of Max Ernst and the photographic oeuvres of many of his contemporaries and other artists that followed. Even a century after André Breton published the first Surrealist Manifesto on 15 October 1924, they have not lost any of their fascination.

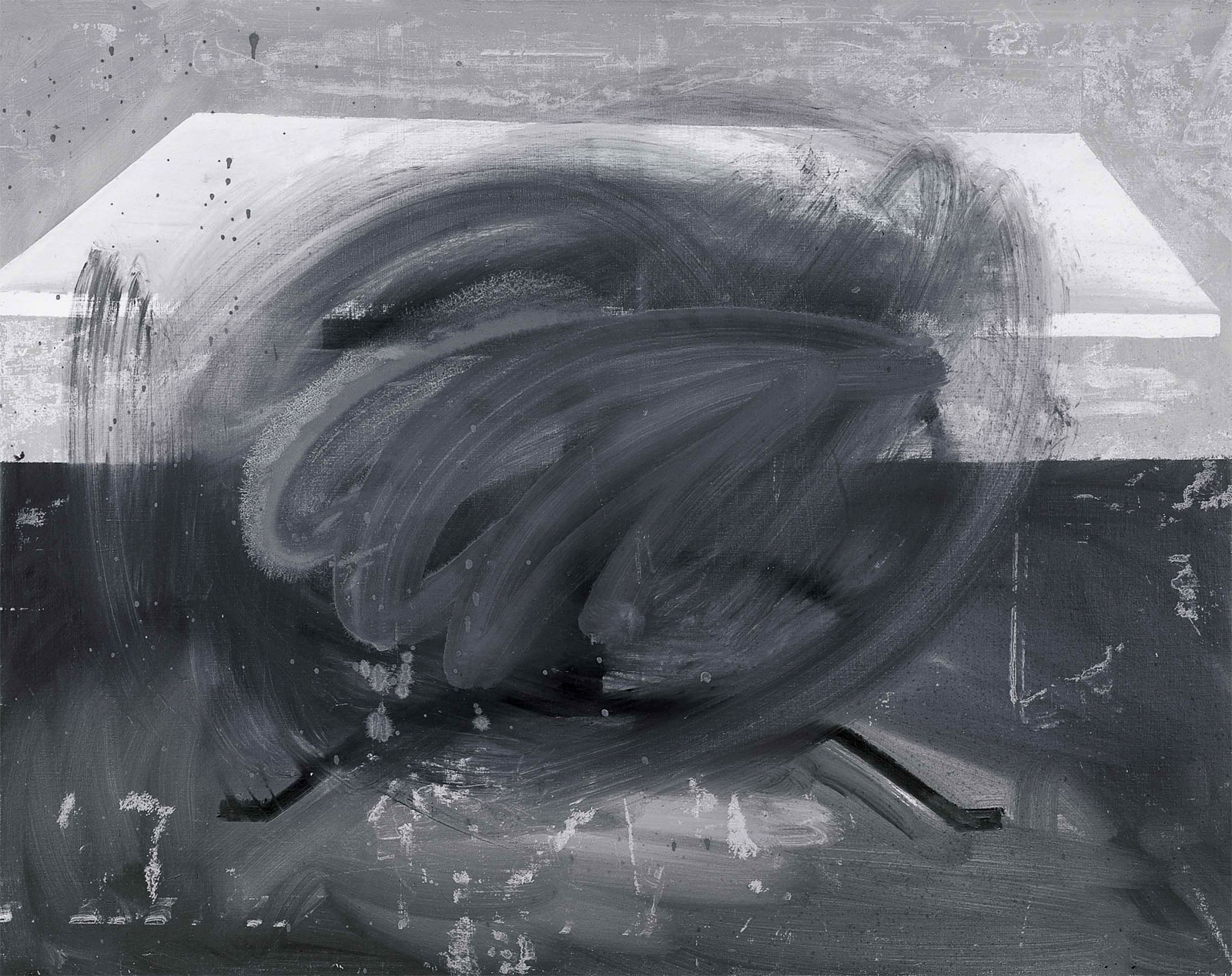

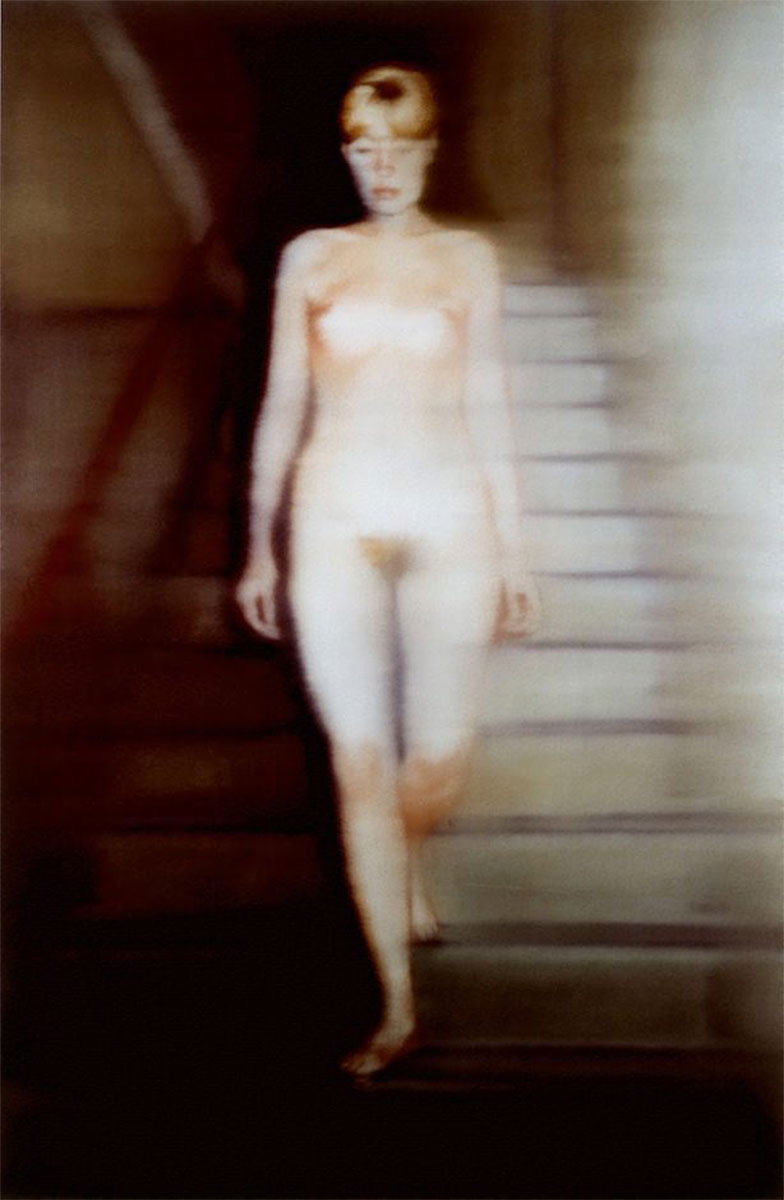

Gazes and Visions

The Motif of the Eye as a Surrealist Symbol

For the Surrealists, free, wild seeing opened up perspectives on an untamed world beyond reality – provided that the eyes were used in the right way or equipped with appropriate devices. Thus the motif of the eye symbolizes the translation of visions into perceptible images. Max Ernst’s frottages show radically enlarged, wide-open eyes hovering over a flat horizon. Visionary seeing can also be assisted by various instruments. In a coloured collage for Les malheurs des immortels, a young man gazes through two pipes, cheeks flushed with excitement: what might he be looking at?

The focus on inner vision becomes the theme of a 1929 collage, in which the portrait photos of the Surrealists, all shown with eyes closed, are arranged around the reproduction of a nude painting by René Magritte. In so doing, a very masculinely connoted group activity is simulated in which sexual desire makes possible the liberation of thought. A violent variation – a blinding, likewise understood as liberation – appears in the famous eyeball-slicing scene in the prologue of the 1928 film Un chien andalou by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí.

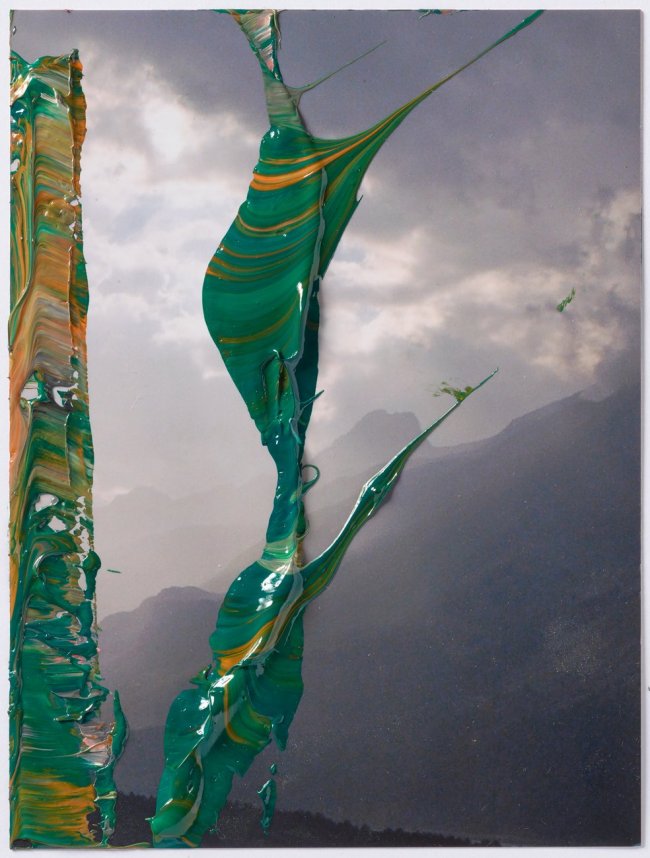

Flora, fauna, firmament

Frottage, Nature Printing, and Plant Photography

Plantlike animals, seashell flowers, fishbone forests, crocheted stars – the visual world of Max Ernst is full of fantastic forms. For him, nature served as both inspiration and material. In his frottages, he used wood, leaves and much more for rubbings on paper. This is how the portfolio Histoire naturelle (Natural History) was created in 1926. The frottages were reproduced as collotype prints, photomechanically produced prints using an exposed glass plate as a printing block.

With Histoire Naturelle, Max Ernst drew on natural history encyclopaedias, but reworked the originals to create his own natural history. In so doing he dissected nature, showed the tiny and the distant, and created planar structures rather than views. This interest in the formal language of nature also resonates in the photography of the New Objectivity from around the same time, which reveal the aesthetic power of natural forms. That also made them interesting to the Surrealist movement.

In his artist’s book Maximiliana or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy from 1964, Max Ernst devoted himself entirely to celestial phenomena. As in photograms, Ernst used objects here like spirals or gears as stencils to evoke comets and nebulas.

Between Positive and Negative

Photogram, Cliché Verre, and Other Darkroom Experiments

The play of positive and negative effects is a recurring theme in Max Ernst’s oeuvre. Early works created using fine lines incised on a black ground show motifs that appear fragile and vague. He also used photographic techniques for some of his works and transformed his frottages into negative forms in Man Ray’s studio. In 1931, for example, he created dark photograms as illustrations for René Crevel’s text Mr. Knife, Miss Fork.

Max Ernst’s use of manually produced prototypes relates to a technique borrowed from the early days of photography: cliché verre, or glass printing. In this hybrid process, an etching is created on a glass plate coated with paint or ink, which then serves as a negative for the print. The twentieth century witnessed a rediscovery of cliché verre and the further amalgamation of photographic and drawing processes. The growing interest in camera-less photography led to a wide range of experiments using light and unconventional materials in various avant-garde circles.

Invisible Cuts

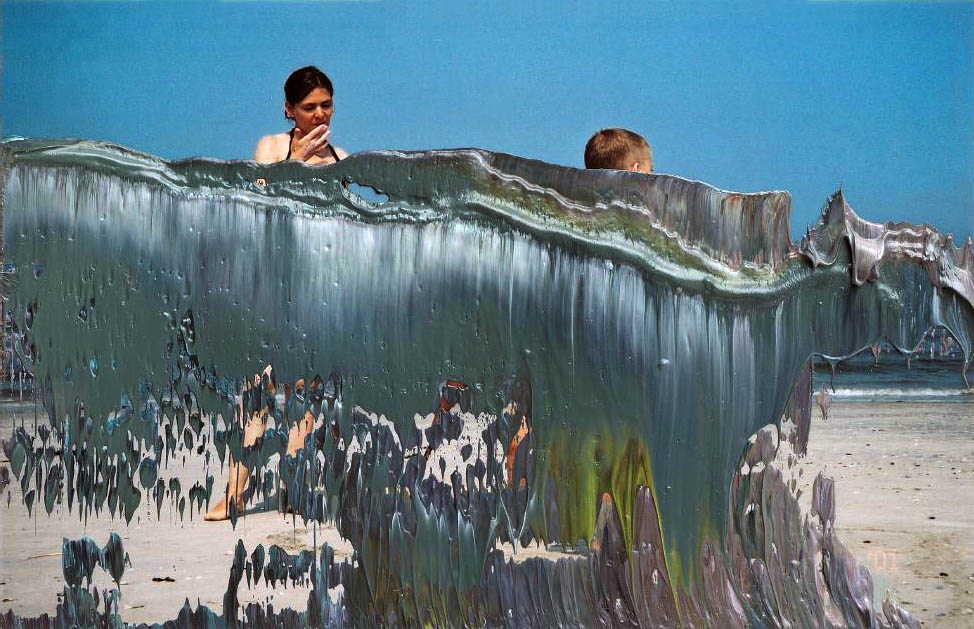

(Photo-) Collages, Collage Novels, and Surrealist Photography

For Max Ernst, collage is the fundamental mode of artistic production. It encompasses a colorful variety of methods for combining materials of all kinds, initiating an open-ended artistic process. Max Ernst had already experimented with collages of printed photographs during his Dada years. The combination of the most diverse illustrations and their fusion into a new image by painting and drawing over them all took place within the working process.

For his wood engraving collages, Max Ernst made use of old-fashioned illustrations from popular scientific magazines of the nineteenth century. Many of these images were also based on photographs; at that time, however, photos could not yet be reproduced and thus had to be rendered as wood engravings. His three collage novels featured visions and hallucinations alongside blasphemy, the critique of bourgeois morals, and the glorification of free love and revolution.

Photographers of the Surrealist movement from Claude Cahun to Karel Teige, from Georges Hugnet to Emila Medková created with the help of camera and darkroom as well as scissors and glue, a rich and multifarious cosmos of idiosyncratic realities that radically transcended traditional aesthetics.

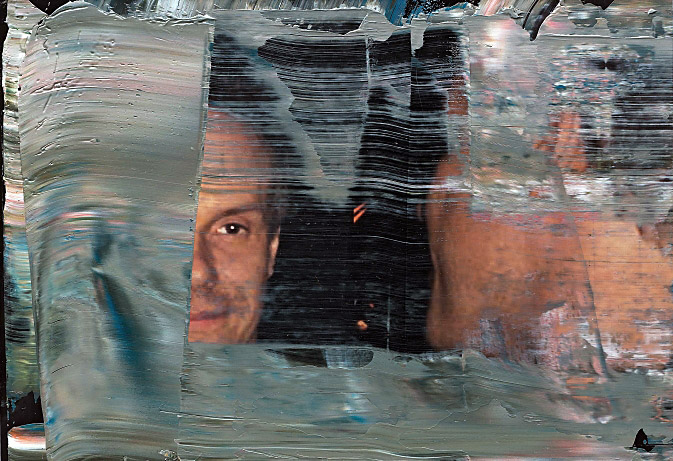

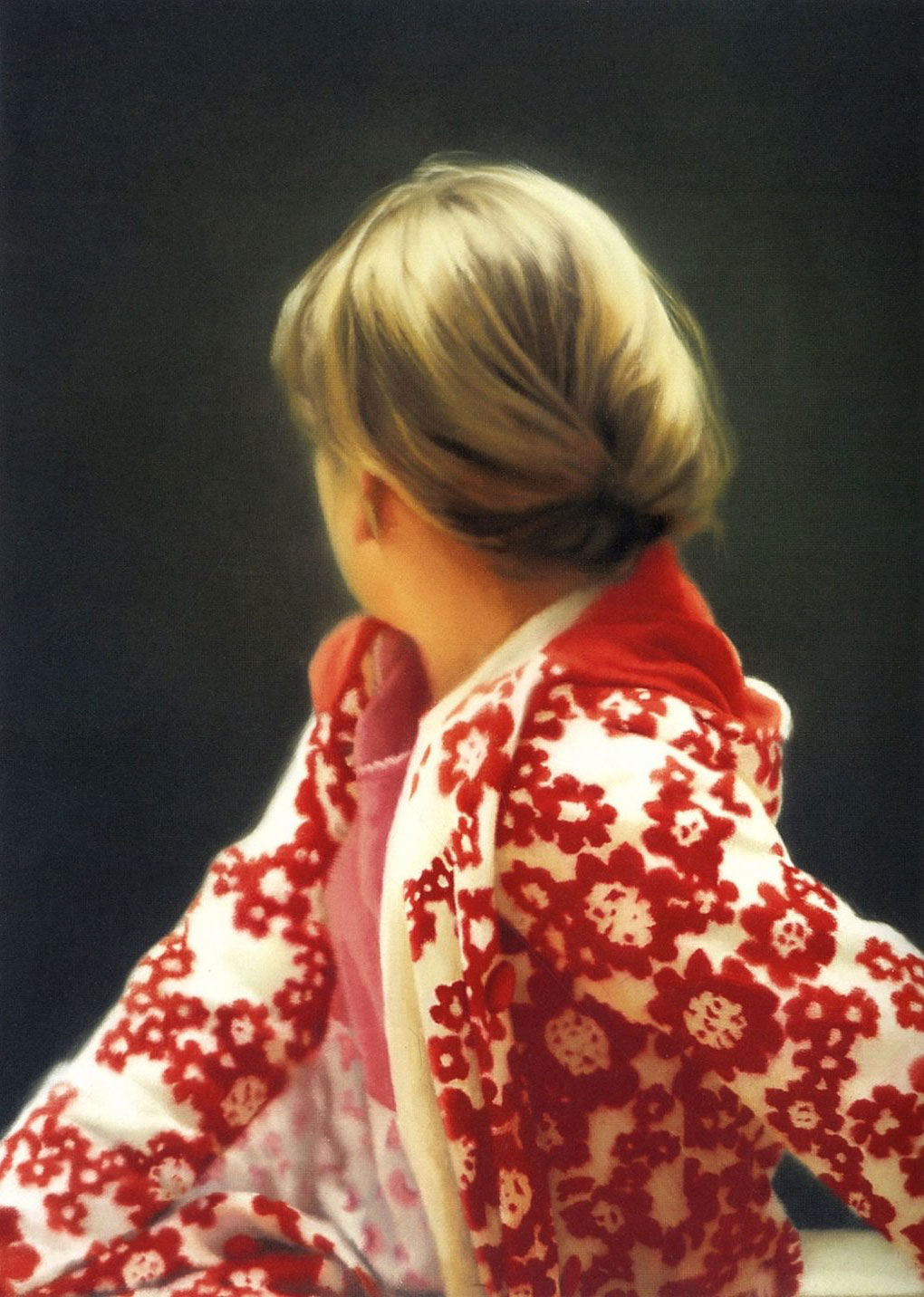

Max Ernst in Front of the Camera

From Studio Portrait to Photo Booth

Max Ernst is one of the most frequently photographed artists of the twentieth century. He posed for the cameras of important photographers such as Berenice Abbott, Arnold Newman, Lee Miller, Irving Penn, and Man Ray. Their portraits demonstrate just how individual the view of a person can be. A whole series of photographs shows the artist at work, with his art, or in the studio. Whether in focused concentration wearing his painter’s smock, in the midst of creative chaos, or in intimate relation to his sculptures – such photographs reinforce or even create the iconic conception of the artist.

Another group of images shows Max Ernst with female companions such as the artists Leonora Carrington or Dorothea Tanning, which convey the intensity of their relations. As a member of the Surrealists Max Ernst frequently appears in group portraits. These images bear witness to the various stations of the movement – its beginnings in Paris or exile in America – as well as to constellations of fashion and gender. Whether individually or in a group, pensive, playful, joyful or serious, the photographs tell of Max Ernst’s delight in self-representation and in theatrical play.

Text from the Museum für Fotografie

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Max Ernst, New York

1941

Silver gelatin paper, new print

25.1 x 20.1cm

Josef Breitenbach (German, 1896-1984)

Max Ernst and the seahorse, New York

1942

Silver gelatin paper

24 x 19cm

Arnold Newman (American, 1918-2006)

Max Ernst, New York

1942

Silver gelatin paper

24.2 x 18.6cm

Frederick Sommer (American, 1905-1999)

Max Ernst

1946

Gelatin silver print

A reproduction of this image on postcard for the Max Ernst retrospective: 30 Years of his Work – A Survey, Copley Galleries, Beverly Hills 1949 is included in the exhibition.

John Kasnetzis

Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst with the sculpture Capricorne, Arizona

1948

Silver gelatin print, later print

23.6 x 18.8cm

In the summer of 1947, Max Ernst, exuberant and inspired by the arrival of water piped to our house (up to then we had hauled it daily from a well 5 miles away), began playing with cement and scrap iron with assists from box tops, eggshells, car springs, milk cartons and other detritus, The result: Capricorn, a monumental sculpture of regal but benign deities that consecrated our “garden” and watched over its inhabitants. Years later, when we had gone, a sculptor friend made molds and sent them to their creator in Huismes, France where he reassembled his Capricorn for casting in bronze. The above photo is a one-shot, spur-of-the-moment caper made after taking a people-less documentary photo.

Dorothea Tanning from Birthday, Santa Monica: The Lapis Press, 1986

Emila Medková (Czech, 1928-1985)

Schwarz / Black

1949

Silver gelatin paper

17.7 x 23cm

Sammlung Dietmar Siegert

© Eva Kosakova Medkova

Repro: Christian Schmieder

Denise Colomb (French, 1902-2004)

Max Ernst on the roof terrace on the Quai Saint-Michel in Paris

1953

Silver gelatin paper, later print

28 x 22cm

Fritz Kempe (German, 1909-1988)

Max Ernst, Hamburg

1964

Silver gelatin print

12.8 x 17.7cm

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Seen at the Neuilly fair

1971

Colour reproduction of a collage, sheet 3 from the portfolio: Commonplaces. Eleven Poems and Twelve Collages

49 x 34.5cm

Museum für Fotografie

Jebensstraße 2, 10623 Berlin

Opening hours:

Tuesday + Wednesday 11am – 7pm

Thursday 11am – 8pm

Friday – Sunday 11am – 7pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.