Exhibition dates: 16th March – 29th May 2011

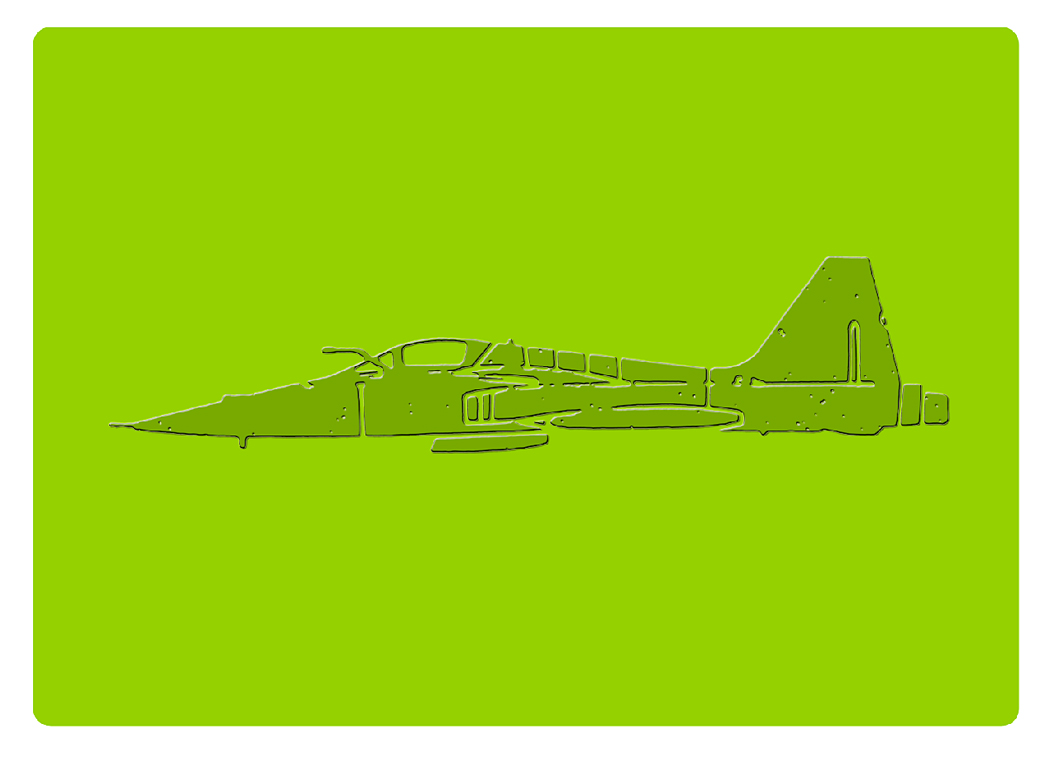

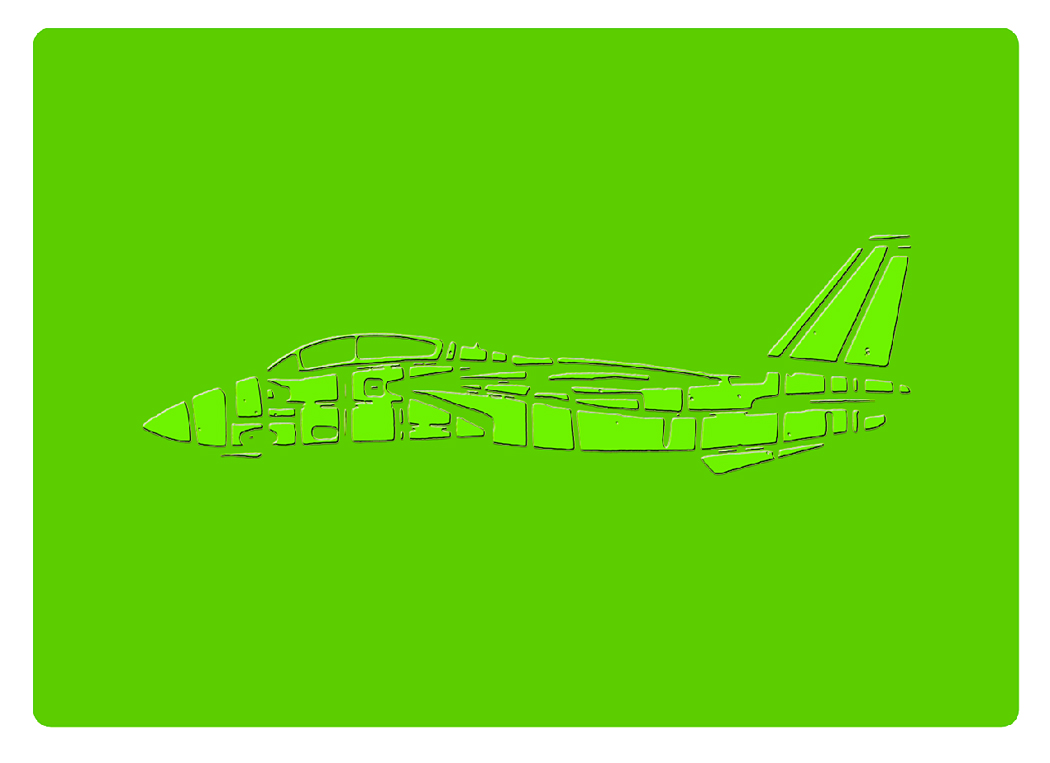

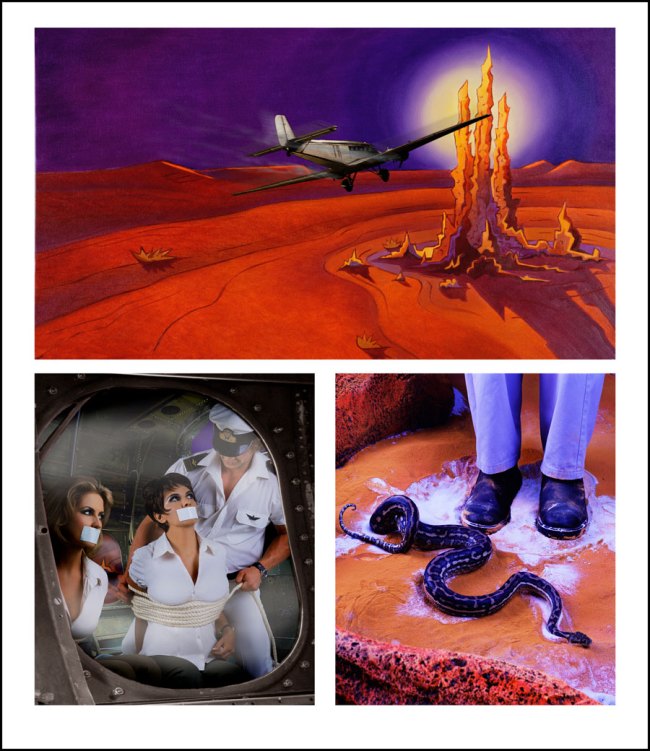

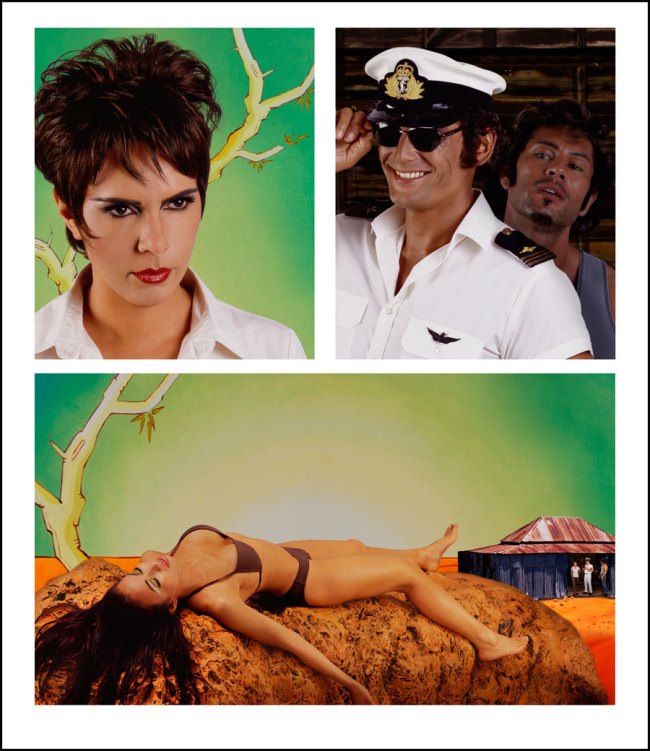

Debra Phillips (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled 7 (view from model plane launch area)

2001

From the series The world as puzzle

Two Type C photographs

68 x 80cm each

Image courtesy the artist and BREENSPACE, Sydney

© Debra Phillips

Hot on the heels of my reviews of Stormy Weather: Contemporary Landscape Photography at NGV Australia and Sidney Nolan: Drought Photographs at Australian Galleries, Melbourne comes the exhibition Photography & place: Australian landscape photography, 1970s until now at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. An insightful, eloquent text by Vigen Galstyan (Assistant curator, photographs, AGNSW) accompanies the posting.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Susanne Briggs for her help and to the Art Gallery of New South Wales for allowing me to publish the photographs and the text in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Douglas Holleley (Australia, United States of America, b. 1949)

Bottle-brush near Sleaford Bay, South Australia

1979

Four SX-70 Polaroid photographs

61 x 76cm

AGNSW collection, purchased 1982

© Douglas Holleley

Australian born and American based photographer Douglas Holleley has experimented with many aberrant photographic techniques over the course of his career. Holleley received a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology in 1971 at Macquarie University before relocating to America to undertake a Master of Fine Arts, studying at the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York between 1974 and 1976. Founded by Nathan Lyons in 1969 and affiliated with important photographers including Minor White and Frederick Sommers, the Visual Studies Workshop was a bedrock institution that fostered innovative photographic practice from the 1970s onwards. It was here that Holleley received tutelage from Ansel Adams in 1975. His early photographic output includes hand coloured black and white photographs as well as photograms and gridded arrangements of Polaroids. He later began experimenting with digital photography, applying the same principles of the photogram to his experiments with a flatbed scanner.

During the time spent studying photography in America in the 1970s Holleley became interested in Polaroid technology. When he returned to Australia in 1979, before later relocating permanently to America, Holleley commenced an extensive photographic project of documenting the Australian bush with a Polaroid SX-70 camera, effectively becoming one of the first professional practitioners of the medium in the country. The resulting images were presented as a series and published as a book – Visions of Australia – in 1980. Employing a refined formalist vocabulary, Holleley produced photographic mosaics by arranging his Polaroids into gridded compositions.

Dissected, disassembled and then collated within the pictorial frame, the landscape in Holleley’s works becomes slightly unnatural and detached. These works negate linear single point perspective by focusing on the ground and reducing the scene to a formal composite. Here, the expanse of the view and the horizon does not dominate the space of the image. The tessellating images produce a ‘whole’ that is slightly misaligned and unsettled. In some works, the photographer’s shadow is visible. It asserts itself as an ambivalent presence that is not tethered to the scene. This spectral form heightens the sense of disquiet that pervades the images.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 16/01/2020

Ian North (New Zealand, b. 1945)

Canberra suite no 2

1980, printed c. 1984

From the series Canberra suite 1980-81

Type C photograph

37 x 45.7cm

AGNSW collection, gift of the artist

© Ian North

Ian North (New Zealand, b. 1945)

Canberra suite no 7

1980, printed c. 1984

From the series Canberra suite 1980-81

Type C photograph

37 x 45.7cm

AGNSW collection, gift of the artist

© Ian North

Ian North is an Adjunct Professor of Visual Arts at both the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. He is a photographer, painter and writer, and was the founding curator of photography at the National Gallery of Australia 1980-1984. Throughout his career, he has been concerned with the legacy of Australian landscape, the impact of colonial narratives and their established visual conventions and, as a consequence, the politics of representing the subject. …

North’s methodology is concerned with the processes of vision and interaction as they have shaped the landscape. In Canberra Suite North presents an encyclopaedic record of Walter Burley Griffin’s intricately designed city, exploring the spatial interface between nature and humanity. The works are absent of human life – reminiscent of Ed Ruscha’s Twenty-six Gasoline Stations. The emotional ambivalence of the images is reflected in their use of colour, like that of postcards. As one of the first instances of larger format colour art photography in Australia, the images topographically map space as a depersonalised, banal subject. Yet their colour, like that of landscape painting, highlights flora, revealing the number of non-native plants included in Canberra’s design. As such, these artefacts of North’s private wanderings and systemic mode of looking are able to subtly critique colonialism.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 16/01/2020

EARTH SCANS AND BUSH RELEVANCES: Photography & place in Australia, 1970s till now

For many of us, landscape is a noun. A view from the window or the balcony, a strange immaterial ‘thing’ that makes people exclaim in awe, point to in pride, recall nostalgically, pose in front of or be used to bump up real estate prices. If one is an urban dweller, which most Australians are, then the landscape exists essentially as a mirage, something to create in the backyard, occasionally look at on holidays or hang on the walls. However, noted American cultural theorist and art historian W. J. T. Mitchell has proposed that we should think of landscape as a verb: an act of creation on our part that engenders cultural constructs, national identities and shared mythologies.

Photography & place is an exhibition that investigates this process of ‘landscaping’ through the work of 18 Australian photographers between the 1970s and now. Their significant contribution to representation of landscape broke new ground in what has always been a confounding topic. Indeed, as Judy Annear has pointed out in a 2008 essay in Broadsheet magazine, the practice of documenting and interpreting the notion of ‘place’ in Australian photography has been fragmentary in comparison to traditions in America, Europe or New Zealand. This reluctance to focus on the natural environment is perhaps a residue of the ‘terra nullius’ polemic, which shifted the attention of many photographers on the building of colonial Australia. Photography from the mid 19th to the early 20th century by photographers such as Charles Bayliss and Nicholas Caire actively documented the conquest of nature by white settlers, or presented views of untouched wilderness as epitomes of the picturesque: endless waterfalls, lakes, forests in twilights, enigmatic caves and an occasional nymph like creature prancing. Despite Bayliss’ efforts to show the indigenous people on their land, they are, as Helen Ennis observed in her 2007 book Photography and Australia, conspicuous by their absence: the land that we see surrounding them in early Australian photography by the likes of J.W. Lindt is often a mass-produced painted studio backdrop.

The advent of modernism in the 1930s only served to entrench the photographers deeper into the urban space. ‘Place’ is the city and it is here that industry, progress and culture shapes the Australian identity. It is still difficult to dislodge the iconic images of Max Dupain and David Moore as epitomes of Australianness, promulgated as they were through countless renditions in mass media and consumer culture. But as post-modern anxiety started to seep through the patchwork of the Australian dream, it was landscape that many critically informed photographers turned to as a tool for analysis and revision.

A number of factors conflated in the mid 1970s, engendering a radical shift in perspectives. One of the primary forces that began to reshape the approaches to landscape in Australian photography was the awareness of new artistic movements taking place in USA and Europe. The enormously influential exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape held in 1975 at the George Eastman House, Rochester, consolidated the spread of minimalist and conceptually informed photography which was avidly embraced by a younger generation of Australian photographers. One can also cite the rise of the Australian greens movement in Tasmania, the increasing awareness of Indigenous cultures and rights and not the least, the phenomenon of university-educated photographers as key milestones during this decade.

Lynn Silverman, Douglas Holleley, Jon Rhodes, Wes Stacey and Marion Marrison were among the practitioners who pointed their lenses out of the city, often exploring the fringes of human settlement and sometimes as in the case of Silverman, Stacey and Holleley, venturing into the desert. The element that collectively stamps their work is the ostensible fragmentation of the landscape. Instead of the holistic, positivist postcard views of Australia, we get something resembling a lunar vista. The palpable sense of alienation in American expatriate Lynn Silverman’s striking Horizons series from 1979 echoes in the disorienting grid-based Polaroid assemblages by Holleley conjuring up a space that appears hostile and to a degree indifferent to our presence. The foreignness of these landscapes is not necessarily a malevolent force as was customary to show in a slate of Australian New Wave films of the 70s and 80s. Rather a much more meditative stance is taken in regards to our relationship to a place which has been claimed without being understood or in many ways respected. Ingeborg Tyssen’s photographs hint at existing presences, forms and phenomena which are full of life and meaning that remain perpetually unresolved to an outsider. The imported paradigms of Western culture can not take root in this environment. One could easily define the landscape photography of this period in Lynn Silverman’s words as “an orienting experience” and a belated attempt at a proper reconnaissance of the land.

The coolly detached outlook that underlines the investigative drive of most of these photographers is magnified by their adoption of serial or multi-panel formats. It was certainly a way to expand and collapse the accepted faculties of the pictorial field, challenging and questioning the accepted notions of photographic ‘truth’. Jon Rhodes demonstrates the inherent power of this simple device in his cinematically sequential Gurkawey, Trial Bay, NT 1974, which transforms a seemingly wild and uninhabitable swamp into a joyful playground of an Aboriginal child.

In some instances the photographic approach is more concerned with elucidating the nature of the photographic image itself and the way it can influence and control our perception. As Arnold Hauser has lucidly described in his groundbreaking Social History of Art, images have always been used to secure and infer political power. As such, the metamorphosis of a visual representation into an iconographic one carries within it an element of danger as images begin to seduce the viewer away from objectivity. Indeed, images of Australia have been the most relentlessly and carefully used signifiers in promoting a (colonial) national consciousness by political, commercial and cultural institutions. In this light, it is not difficult to see the works of Wes Stacey and Ian North as acts of iconoclasm. Stacey’s droll and gently parodic series The road 1973-1975, charts a snapshot journey that goes nowhere. Seemingly random, half-glimpsed shots of empty dirt roads, sunburnt grass mounds and endless highways emanate a sense of rootlessness and displacement, negating any possibility of objectification or identification with the landscape. Instead of epic grandeur and jingoism we get something that is confronting, uncomfortably real and in no way ‘advertisable’.

‘The Real’ is even more startling in Ian North’s subversive Canberra suite 1980-81, where the utopian dream capital has been reduced to banal ‘documents’ of depopulated, custom-made suburbia. The hyperreal concreteness of North’s Canberra gives the city an aura of a De Chiricoesque waking nightmare. In line with the set practices of conceptual photography of the period, North has distilled his images from any sign of formal mediation, forcing the viewer to focus on the raw content. It is through this forensic directness that the strange incongruity of human intervention within the landscape becomes ostensible.

Daniel Palmer has noted that North’s images “are highly prescient of much photography produced by artists in Australia today”. Certainly by the 1980s photographers became more actively engaged in analysing the nature / culture median. Strongly influenced by feminist and post-colonial theory, a number of practitioners used photography as a medium to document ideas rather than objective reality. Anne Ferran and Simryn Gill are particularly notable in this regard. Both artists are concerned with the historical and political dimensions of the locations they chose to photograph, resulting in multi-layered and complex strategies that require more involved intellectual interaction from the audience. Gill’s ‘staged’ photographs relate to us the agency of nature and time upon the cultural environment. Synthesis and amalgamation of outwardly irreconcilable elements – imported plants, Australian bush, cotton shirts – slowly, but surely melt into new, as yet unknown entities in Rampant 1999. The force of inevitable decay is absolute yet imbued with generative power as well. Exploring the constantly shifting certainties of what constitutes a ‘place’ the artist draws the audience into questioning its own role in this transformative process.

Ferran takes a more archaeological position in relation to her subject matter. Her eerie surveys of rather ordinary grass mounds in the series Lost to worlds 2008 become evocative paeans to obliterated lives, once we learn that the mounds are all that remain of the factories where convict women were sent to work. Looking at these shimmering ghost worlds one is reminded of Walter Benjamin’s essay The Ruin where the writer analyses the capacity of ruins to reveal the “philosophical truth content”. It is through this allegorical device that Ferran achieves a degree of rehabilitation for the absent histories she photographs.

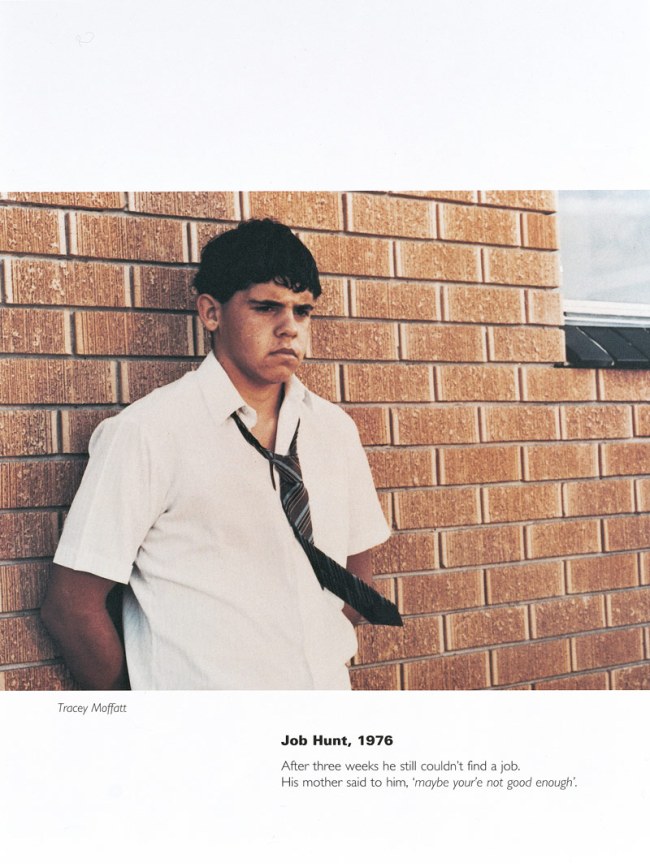

History, in its manifold and troubling guises, is directly ‘exposed’ in the landscapes of Ricky Maynard, Michael Riley and Rosemary Laing. As Indigenous photographers, Maynard and Riley have played an important role in translating the cultural and political status of Aboriginal peoples into a ‘language’ that is universally understood. Their work remains firmly rooted in the traditions of contemporary art, yet the heavily symbolical slant shows a more ardent and personal engagement with the Australian landscape. Riley’s expressionistic series flyblown 1998 sums up in a few strategically juxtaposed metaphors the spiritual dimension of the landscape, while simultaneously revealing the diverging connotations of Australia’s fundamentally divided identity. The colonial legacy is shown as one of conquest and domination that clashes with the artist’s engagement with country. Maynard’s Portrait of a distant land 2005, explores the same dichotomy in more site specific terms. After permanently settling in Flinders Island, Maynard decided to return to the portrayal of Tasmanian Aborigines, taking a more collaborative approach. He sees this as a way of bypassing the propensity of the photographic image “to subjugate its subjects”. The resulting series is a profoundly poetic treatment that rises above social documentation to suggest the wider implications of historical change and disclose the ability of people to overcome what the artist has described as victimisation through a deeply compassionate relationship with the land. Ultimately Maynard gives us an edifying testimony to the affirmative power of the landscape as collective memory.

Interest in the political aspects of landscape photography has continued unabated into the 21st century. Yet a more philosophically inclined thread has become evident in the last two decades. No longer is it enough to deconstruct and pull apart ideas about landscape’s relationship to identity and nationhood. What photographers like Bill Henson, David Stephenson, Simone Douglas and Rosemary Laing question is the very possibility (or impossibility) of seeing itself. If positioning oneself in relation to nature seems like a distinct, albeit problematic proposition in the 1970s and 80s, the later works in the exhibition are resolutely ambivalent on the subject.

What can one grab onto when faced with the endless expanses of white in Stephenson’s The ice 1992, the terrifying darkness of Henson’s night scenes or the infuriating haze of Douglas’s twilight worlds? Perhaps the only recourse is to dissolve into the beckoning ‘forever’ of the vanishing point in Laing’s To walk on a sea of salt 2004. This void is not a boundary point between nature and culture – it is where culture ends and an entirely new state of consciousness begins: the realm of the sublime and the imagination. As history seems no longer to be trustworthy, ‘place’ can only be constructed as a metaphysical entity. It is a curious turnabout in some ways that echoes some of the early, turn-of-the-century encounters with the Australian landscape by photographers such as John Paine and Norman C. Deck. The sense of fear and awe towards the unfamiliar environment permeates their images, transcending the merely investigative / didactic motives of most colonial photography. What has eventuated from walking into this environment? Subjugation? Destruction? Incomprehension? Indifference? By going back to the point zero of the void and the sublime, contemporary photography negotiates a second attempt at engagement with nature through a renewed and deeper understanding of humanity’s symbiotic relationship with this life-giving force.

Vigen Galstyan

Assistant curator, photographs1

1/ Galstyan, Vigen. “EARTH SCANS AND BUSH RELEVANCES: Photography & place in Australia, 1970s till now,” in Look gallery magazine. Sydney: Art Gallery Society of New South Wales, 2011, pp. 25-29.

Rosemary Laing (Australian, b. 1959)

After Heysen

2005

Type C photograph

110 x 252cm

On loan from The Australian Club, Melbourne

Image courtesy of the arts & Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

© Rosemary Laing

Rosemary Laing (Australian, b. 1959)

to walk on a sea of salt

2004

Type C photograph

110 x 226.7cm

Image courtesy of the arts & Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

© Rosemary Laing

Jon Rhodes (Australian, b. 1947)

Hobart, Tasmania

1972-75

From the album Australia

1 of 53 gelatin silver photographs

11.9 x 17.7cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1980

© Jon Rhodes

Jon Rhodes (Australian, b. 1947)

Tuncester, New South Wales

1972-75

From the album Australia

1 of 53 gelatin silver photographs

11.9 x 17.7cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1980

© Jon Rhodes

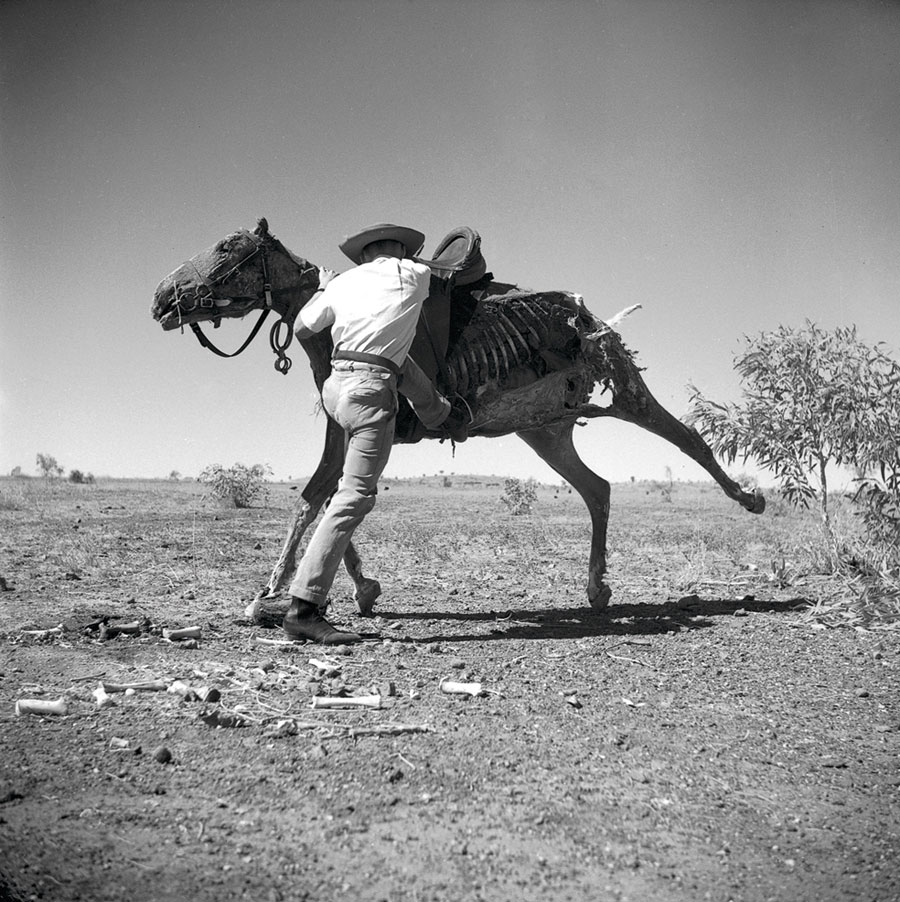

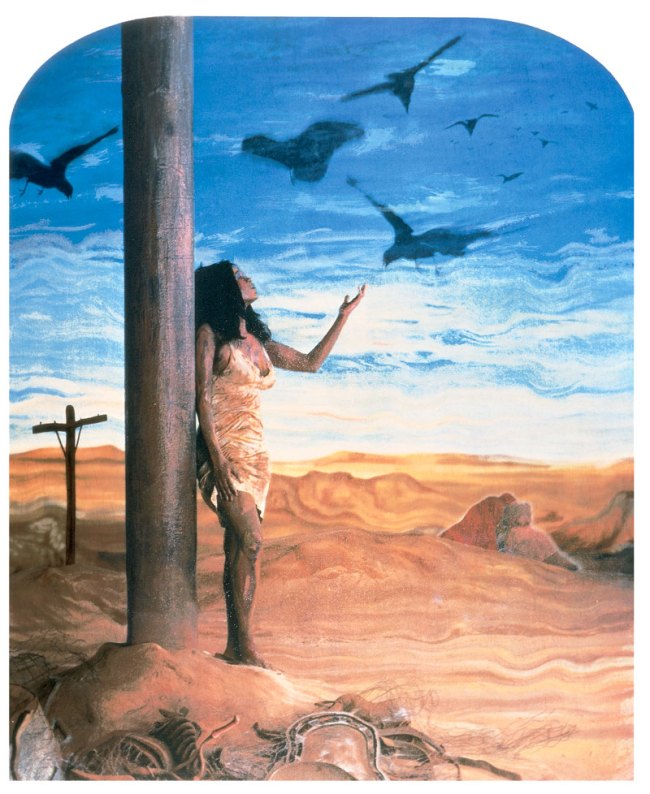

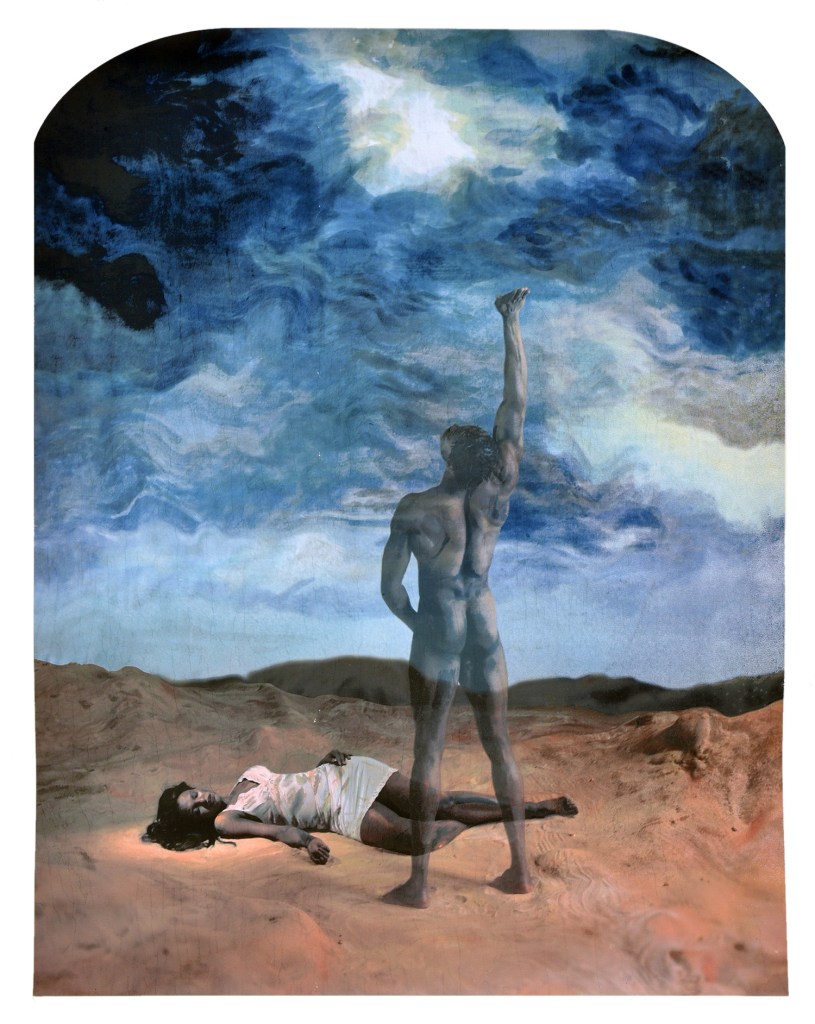

Michael Riley (Australian, 1960-2004)

Untitled

1998

From the series flyblown

Pigment print

82 x 107.8cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Anonymous gift to the Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander and Photography collections 2010

© Michael Riley Estate. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Michael Riley (Australian, 1960-2004)

Untitled

1998

From the series flyblown

Pigment print

82 x 107.8cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Anonymous gift to the Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander and Photography collections 2010

© Michael Riley Estate. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Michael Riley received his first introduction to photography through a workshop at the Tin Sheds Gallery in Sydney, 1982. A Wiradjuri / Kamilaroi man, the artist moved to Sydney from Dubbo in his late teens. He became part of a circle of young Indigenous artists drawn together in the city at that time. A founding member of the Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative Riley was also a key participant in the first exhibition of Indigenous photographers at the Aboriginal Artists Gallery, Sydney in 1986 (curator Ace Bourke). In 2003 Riley’s work was selected for the Istanbul Biennial, and in 2006 his work was permanently installed at Musée de quai Branly, Paris. A major retrospective toured nationally in 2006-2008.

Riley’s fine art photography began in black and white but he quickly progressed to large-scale colour, a format that also expanded the cinematic qualities of his images, no doubt reflecting the influence film and video were having upon the artist as he worked simultaneously with these media. He produced, for example, the documentaries Blacktracker and Tent boxers for ABC television in the late nineties.

The photographic series flyblown bears a close relationship to the film Empire which Riley created in 1997. Like the film, these photographs give expression to the artist’s concern with the impact of European culture upon that of Australia’s Indigenous population, specifically, as he described it, the ‘sacrifices Aboriginal people made to be Christian’ (Avril Quaill, ‘Marking our times: selected works of art from the Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Collection at the National Gallery of Australia’, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra 1996 p. 66).

Christian iconography looms large in the series, as it has across much of Riley’s work. In flyblown, an imposing reflective cross is raised in the sky. Repeated in red, gold and blue its presence is inescapable. A symbol capable of inspiring awe, fear, devotion, Riley also engages with its elegiac qualities so that it functions as memorial marker. Another image depicting a bible floating face down in water conceptualises the missionary deluge, perhaps; submersion and loss through baptism, definitely.

flyblown reverberates with a subtle ominous hum – the quiet tension that precedes a storm. The parched earth beneath a dead galah seems to ache for the rain and water promised in the other images of clouds and dark skies. The nourishment Christianity offered and the inadvertent drowning of traditional culture that often followed is implied.

Visually linking the natural environment with religious symbolism Riley articulates Indigenous spirituality’s connections to country and widens his examination beyond to examine the sustained environmental damage. The negative side effects of pastoralist Australia are indicated by contrasting images of the long grass of cattle pastures with that of drought and wildlife death.

Riley’s success in articulating these issues and complexities, incorporating religious iconography so laden by history and meaning is a testament to his sensitivity and subtlety. Allowing room for ambiguity, Riley provides space for the mixed emotions of the subject and its history.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 16/01/2020

Simryn Gill (Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, b. 1959)

Untitled

1999

From the series Rampant

Gelatin silver photograph

25 x 24cm

AGNSW collection, gift of the artist, 2005

© Simryn Gill

In Rampant, Simryn Gill turned her eye once more on Australia ‘… to see if I could find friends among the local flora’. This series of photographs was shot in sub-tropical northern New South Wales and shows unnerving images of trees and plants dressed up in clothes. In the photographs these ghostly forms are seen lingering in groves of introduced plants such as bamboo, bananas, sugar cane and camphor laurels. The plants are dressed in lungis and sarongs, generic clothing from South and South- East Asia, where many of these plants originate. Rampant is a form of memento mori, a record of the aspirations that saw plants only too successfully introduced into a pristine terrain which was unable to offer any resistance to their feral ways.

French philosopher Gaston Bachelard condenses his complex thinking on creativity and the human imagination into the metaphor of a tree, with its living, evolving growth and the simultaneity of being earth bound and heaven reaching, symbolising both the real and ideal.1 However, what happens when that tree is a camphor laurel, an admirable thing in its native land but out of place and wrecking havoc along the creeks of rural New South Wales?

Many once-useful species are now noxious weeds and over-successful colonisers, despised for their commonness, their success, their over-familiarity, and for being where we feel they should not be. They disrupt the order we would like to impose and remind us of our fallibility when attempting to play god and create our own earthly Edens. The language of natural purity that we use to protect our landscape also resonates with the nationalist rhetoric used to police our borders and to decide who are acceptable new arrivals and who are illegal aliens, often determined through scales of economic and social usefulness.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 16/01/2020

1/ Gaston Bachelard, ‘The totality of the root image’, On poetic imagination and reverie, editor and translator Colette Graudin, Spring Publications, Quebec, 1987, p. 85.

Anne Ferran (Australian, b. 1949)

Untitled

2008

From the series Lost to worlds

Gelatin silver print

© Anne Ferran

Anne Ferran (Australian, b. 1949)

Untitled

2008

From the series Lost to worlds

Gelatin silver print

© Anne Ferran

Wesley Stacey (Australia, b. 1941)

The road: Outback to the city 3

1973-1975

Folio 1 from “The Road” a portfolio of 280 photographs

Fuji Colour machine print

© Wesley Stacey

Wesley Stacey (Australia, b. 1941)

The road: Surfers to Hobart 15

1973-1975

Folio 16 from “The Road” a portfolio of 280 photographs

Fuji Colour machine print

© Wesley Stacey

Wesley Stacey (Australia, b. 1941)

The road: Port Hedland/Wittenoon/Roeburne, WA 14

1973-1975

Folio 10 from “The Road” a portfolio of 280 photographs

Fuji Colour machine print

© Wesley Stacey

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art Gallery Road, The Domain, Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

Opening hours:

Open every day 10am – 5pm

except Christmas Day and Good Friday

![Leonardo da Vinci (Italian, 1452-1519) 'Study for the head of Christ for The Last Supper [Testa di Cristo]' c. 1494-1495 Leonardo da Vinci (Italian, 1452-1519) 'Study for the head of Christ for The Last Supper [Testa di Cristo]' c. 1494-1495](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/leonardo_da_vinci_head_of_christ_c1494_5.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.