Exhibition dates: 24th August – 29th December 2024

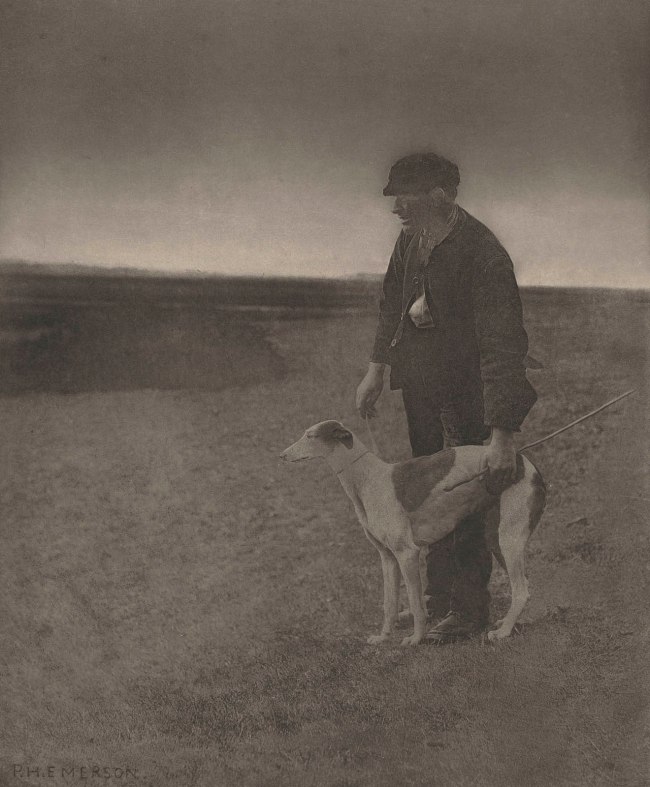

Peter Henry Emerson (British born Cuba, 1856-1936)

Poling the Marsh Hay

c. 1885

Platinum print on paper

Id est / that is

Voluptuous = relating to or characterised by luxury or sensual pleasure

Sensual = late Middle English (in the sense ‘sensory’): from late Latin sensualis, from sensus (see sense)

Sense = various; including:

~ a reasonable or comprehensible rationale i.e. the latent and emerging Modernism inherent in Photo-Secession photographs

~ the way in which a situation [in this case the “reading” of a photograph] can be interpreted i.e. the interpretation of Photo-Secession photographs as either Pictorialist, Modernist or a combination of both

~ a keen intuitive awareness of or sensitivity to the presence or importance of something i.e. the feeling of the photographer towards the object of their attention, revealed in the print, whether that be a nude, a building, pears and an apple or the side of a white barn

~ to be aware of (something) without being able to define exactly how one knows i.e. to be able to detect, recognise, and feel that ineffable “something” that emanates from the object of (y)our attention… in the act of creativity, in the act of seeing

Bringing something to our senses

Thus, the older I get the more I appreciate the faculty of feeling, thought and meaning that is revealed in these revolutionary photographs.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Quotes on Walls

“Why, Mr. Stieglitz, you won’t insist that a photograph can possibly be a work of art – you are a fanatic!”

Luigi Palma de Cesnola, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, reportedly said to Alfred Stieglitz, 1902

“The painter need not always paint with brushes, he can paint with light itself. Modern photography has brought light under control and made it as truly art-material as pigment or clay. … The photographer has demonstrated that his work need not be mechanical imitation. He can control the quality of his lines, the spacing of his masses, the depth of his tones and the harmony of his gradations. He can eliminate detail, keeping only the significant. More than this, he can reveal the secrets of personality. What is this but Art?”

Arthur Wesley Dow, 1921

“The photographer’s problem therefore, is to see clearly the limitations and at the same time the potential qualities of his medium… without tricks of process or manipulation, through the use of straight photographic methods. … Photography is only a new road from a different direction but moving toward the common goal, which is Life.”

Paul Strand, 1917

“Pictorial photography owes its birth to the universal dissatisfaction of artist photographers in front of the photographic errors of the straight print. Its false values, its lack of accents, its equal delineation of things important and useless, were universally recognised and deplored by a host of malcontents… I consider that, from an art point of view, the straight print of today is not a whit better than the straight print of fifteen years ago. If it was faulty then it is still faulty now.”

Robert Demachy, 1907

“Gum, diffused lenses, (ultra) glycerining, were of experimental interest once. … Most of these are of more value historically than artistically. The prints are neither painting (or its equivalents) nor photographs. Let the photographer make a perfect photograph. It will be straight and beautiful – a true photograph.”

Alfred Stieglitz, 1919

Photo-Secession: Painterly Masterworks of Turn-of-the-Century Photography celebrates an intrepid group of photographers, led by preeminent photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who fought to establish photography as fine art, coequal with painting and sculpture at the turn of the 20th century. The Photo-Secession movement took cues from European modernists – who seceded from centuries-old academic traditions – to demonstrate photographic pictures’ aesthetic, creative, and skilful value as art. An homage to Stieglitz, Photo-Secession includes some of the very images that established the appreciation of photography’s artistic merits.

The UMFA will present this exhibition concurrently with Blue Grass, Green Skies: American Impressionism and Realism from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to draw attention to the cyclical dialogue between painting and photography in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During this period, photographers manipulated their images at various stages of production to imitate painterly effects, while painters worked and reworked their oils to imitate the immediacy of photography, demonstrating a remarkable reciprocity between these two art forms.

Text from the Utah Museum of Fine Arts website

Installation view of the exhibition Photo-Secession: Painterly Masterworks of Turn-of-the-Century Photography at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts showing the work of Heinrich Kühn

Image courtesy of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts

Installation view of the exhibition Photo-Secession: Painterly Masterworks of Turn-of-the-Century Photography at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts showing at centre from left to right, Bernard Shea Horne Doorway Abstraction; Drahomir Josef Ruzicka The Arch, Pennysylvannia Station c. 1920; Arnold Genthe Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico c. 1920; William E. Dassonville The Great Highway, San Francisco c. 1905

Installation view of the exhibition Photo-Secession: Painterly Masterworks of Turn-of-the-Century Photography at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts showing from top left to right, Edward Steichen Lotus, Mount Kisco 1915; Edward Steichen Calla Lily c. 1921; Edward Steichen Three pears and an apple c. 1921; Edward Steichen Blossom of White Fingers c. 1923

Installation view of the exhibition Photo-Secession: Painterly Masterworks of Turn-of-the-Century Photography at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts

Installation view of the exhibition Photo-Secession: Painterly Masterworks of Turn-of-the-Century Photography at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts showing in the display cabinet issues of the magazine Camera Work, 1903-1917. Edited by Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen

The Role of Camera Work

One of the key platforms for the Photo-Secession movement was the influential journal Camera Work, edited by Stieglitz and Steichen. Published from 1903 to 1917, Camera Work featured the work of Photo-Secessionists alongside essays and critiques that championed the artistic potential of photography. The journal played a crucial role in shaping public and critical perceptions of photography, providing a space for photographers to showcase their work and engage in intellectual discourse.

Adelaide Ryder. “The Photo-Secession Movement: Pioneering Artistry in Early Photography,” on the UMFA website Nd [Online] Cited 22/10/2024

Introduction

This exhibition celebrates 26 intrepid artists at the turn of the 20th century who sought to establish photography as a fine art equal to long-established media like painting, sculpture, drawing, and printmaking. This movement in the United States centred on the group dubbed the Photo-Secession. While each of the Photo-Secessionists had their distinctive approaches, their works are hand-crafted photographic prints of traditional artistic subjects, such as landscape, portraiture, figure study, and still life. This combination of painterly imagery and printmaking is also known as Pictorialism.

The passionate leader and tenacious advocate of the Photo-Secession was Alfred Stieglitz, who advanced the visions of the most ambitious photographers of the time, including Heinrich Kühn, Gertrude Käsebier, Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, and Clarence White. Stieglitz tirelessly promoted art photography through his exhibition space in New York City – the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession and later called simply 291 – as well as through the journals he edited – Camera Notes (1897-1903) and Camera Work (1903-1917).

This exhibition also covers the breakup of the Photo-Secession, as some photographers rejected Pictorialism while others remained staunchly committed to it. The Photo-Secession itself irrevocably split apart around 1917. Artists led by Stieglitz, Steichen, and Strand switched to Straight Photography, an approach involving sharp focus and direct printing of the original shot. Artists led by Käsebier and White continued to innovate through painterly approaches using soft focus and manipulated prints.

The works in this exhibition represent some of the most influential artists and iconic images of the period as well as superb examples of a variety of photographic printing techniques, including platinum, gum-bichromate, carbon, cyanotype, and bromoil.

All works of art this exhibition are from the private collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg. This exhibition is organised by art2art Circulating Exhibitions.

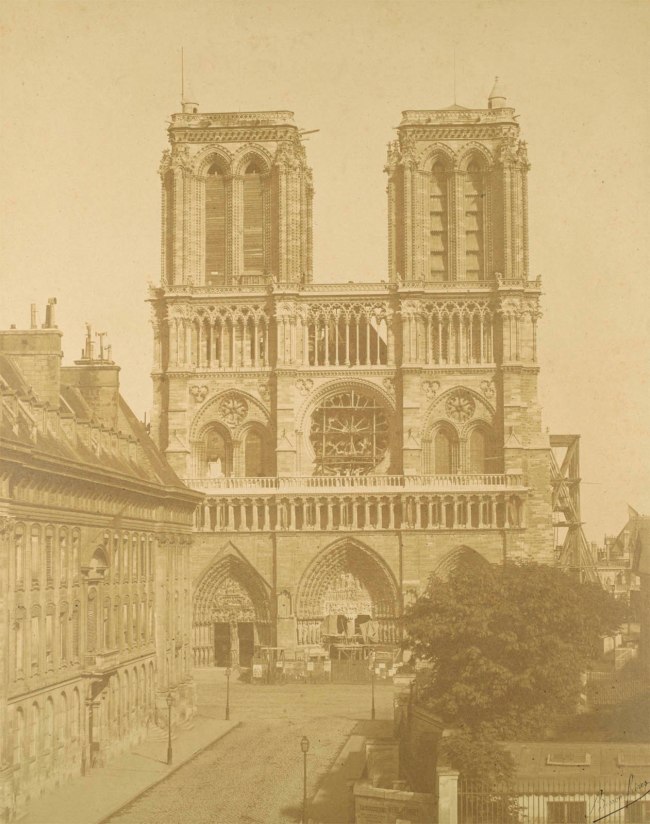

The Rebirth of Art Photography in Europe

In the first few decades after the invention of photography in 1839, painters played an instrumental role in the development of this new medium. Artist-photographers like D.O. Hill in Edinburgh and Gustave Le Gray in Paris exhibited their photographs alongside paintings, drawings, and prints. The novelty of the photograph led to the proliferation of portrait studios and mass-produced views of famous monuments or exotic locales for the tourist trade. By the 1860s photography was considered a bourgeois technical profession. The Kodak camera, first issued in 1888, further popularised photography with its roll film, simple controls, and reasonable cost of one dollar (about $33 today).

Even as more and more individuals could access the means to make photos, artist-photographers advocated for the status of their medium and demanded a differentiation between their work and the products of point-and-shoot cameras. In 1889 Peter Henry Emerson published the book Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art, which proposed a role for landscape photographers equal to esteemed painters like Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet. Emerson’s publication was a clarion call for a new generation of artistic photographers, and Pictorialism was born.

Pictorialist photographers enthusiastically pursued their new movement, pioneering soft-focus lenses and manipulatable printing methods. Soon they were forming regional clubs across Europe and resumed exhibiting their prints as art. The photographers that formed the t in London were particularly active and influential, and Pictorialism spread to other cultural centres like Paris, Berlin, and Vienna.

Alfred Stieglitz and the American Pictorialist Movement

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, but educated largely in Germany, Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) watched the flowering of European Pictorialism with a mixture of aesthetic appreciation and fierce competitiveness, writing in 1892:

“Every unbiased critic will grant that we [American photographers] are still many lengths in the rear, apparently content to remain there, inasmuch as we seem to lack the energy to strive forward – to push ahead with that American will-power which is so greatly admired by the whole civilised world.”

Energised by European Pictorialism, Stieglitz championed juried photographic salons in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. He also edited a series of increasingly ambitious journals about Pictorialist photography, starting with The American Amateur Photographer in 1893, then Camera Notes in 1897, and finally Camera Work starting in 1903. He inaugurated and named the Photo-Secession movement through the landmark exhibition he curated in 1903 at the National Arts Club in New York, which comprised 162 works by 32 artists. The name “Photo-Secession” referred to European avant-garde artistic movements, and in his own words, “Photo-Secession actually means a seceding from the accepted idea of what constitutes a photograph.” Eventually European artists would also be invited to join the Photo-Secession.

In 1905 Stieglitz opened a space at 291 Fifth Avenue in New York, the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later simply called 291. It was the first retail gallery devoted to photography. He supported the venture with his own resources and generous assistance from others, and Edward Steichen was his steadfast associate. By 1915 Stieglitz was also showing avant-garde painting and sculpture at 291, including works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Constantin Brâncuși. Thus, he sought to demonstrate the idea that all art forms were on par with and informed one another.

Close Collaborations and the Sudden End of the Photo-Secession

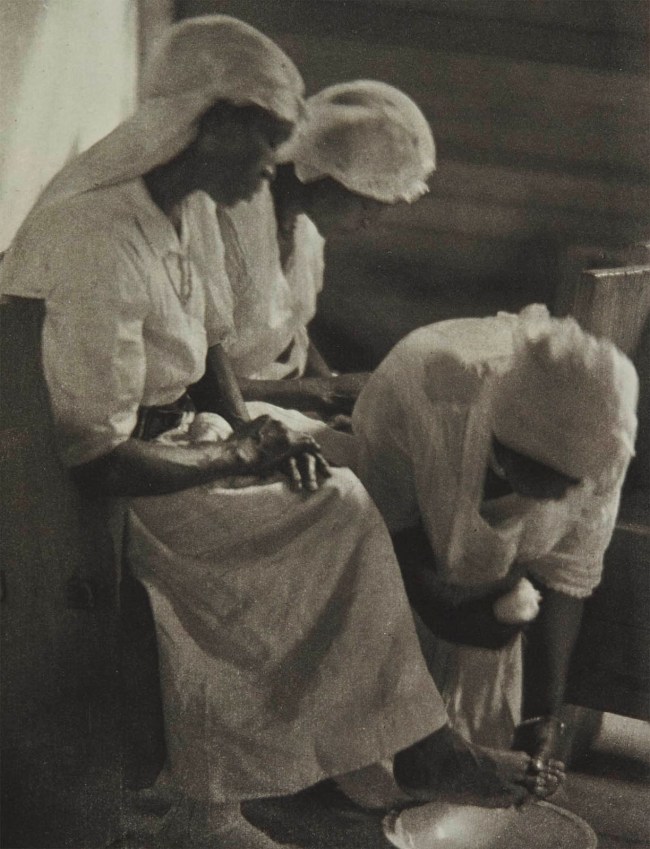

From 1907 to 1910 Alfred Stieglitz and Clarence White closely collaborated on photographs and a landmark photography exhibition. In 1907 they made a series of 60 nudes, Stieglitz posing the models and White focusing the camera and making most of the prints. The following year, Stieglitz devoted an entire issue of Camera Work to White. In 1910 Stieglitz and White co-curated the International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography at Buffalo’s Albright Gallery (now Albright Knox Gallery). This historic project that included over 600 prints is now regarded as the apex of the Photo-Secession. It was also the final monument of the movement, as each of the major Pictorialists, White included, broke away from Stieglitz in the years that followed.

Significant reasons for the end of the Photo-Secession were Stieglitz’s authoritarian personality and disdain for photographers who needed to earn a living rather than exclusively pursue art for art’s sake. Philosophical differences also explain the rupture. Stieglitz had come to believe that Pictorialism had run its course. The irony was that the Photo-Secession had established photography as fine art through images that imitated other art forms by manipulation at every stage of the process – from lens to negative to print. Their pictures to varying degrees used methods that denied the very essence of photography. Stieglitz asserted that it was time to abandon the “painterly photograph” and to champion photography as fine art with compelling pictures that were truly photographic.

Late Pictorialism and the Clarence White School

As the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz’s partner for 30 years, acknowledged, “He was either loved or hated – there wasn’t much in between.” For reasons both personal and professional, most of the leading Photo-Secessionists chose not to follow Stieglitz and Paul Strand into Straight Photography. Many clustered instead around Clarence White, who in his gentle and encouraging manner was the antithesis of Stieglitz. In 1914 White founded the Clarence White School of Photography in New York City. In 1916 White along with Gertrude Käsebier and Alvin Langdon Coburn co-founded Pictorial Photographers of America; this new society welcomed members of all backgrounds and published the new journal Photo-Graphic Art.

The Clarence White School continued to be a locus for the training of new photographers until 1940, under the guidance of White’s widow Jane White after his death in 1925. Among the most prominent students of Clarence White are Karl Struss, Anne Brigman, Laura Gilpin, and Doris Ulmann, all of whom are represented in this exhibition. Other notable pupils of White include Margaret Bourke-White, Anton Bruehl, Paul Outerbridge, and Dorothea Lange.

Straight Photography, Edward Steichen, and Paul Strand

The final section of this exhibition focuses on Straight Photography and two of Alfred Stieglitz’s most notable protégés, Edward Steichen and Paul Strand. Between them, they pioneered leading branches of 20th-century American photography.

With the entry of the United States into World War I, both Steichen and Strand were drafted into the U.S. Army. Steichen was a photographer for the Army Air Service Signal Corps in Europe, and Strand was an X-ray technician in the Army Medical Corps. In the years immediately after WWI, they each turned their attention to photographing the natural world: flowers and fruit in Steichen’s case, and toadstools, grasses, and ferns in Strand’s. Both would return to photographing their gardens in the final years of their lives.

Outside the naturalist realm, Steichen and Strand’s paths diverged.

Steichen, an extrovert, pioneered modern fashion and advertising photography for the Condé Nast magazines Vogue and Vanity Fair. Later he was named Director of the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where he organised the landmark exhibition, Family of Man, which traveled to 37 countries on six continents and was seen by an estimated nine million people.

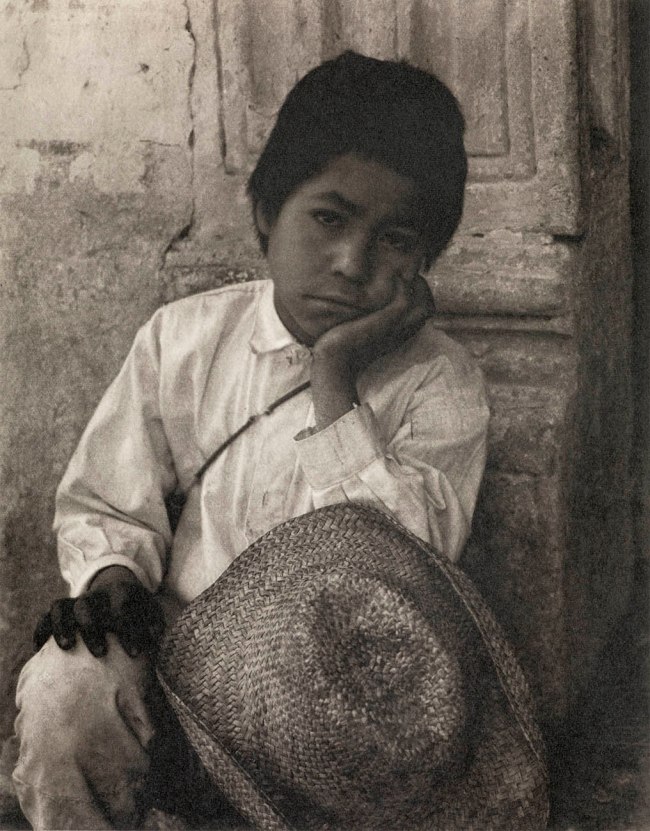

Strand, an introvert, traveled to remote places around the world, documenting the landscape, architecture, and people, his work exuding a respect for the dignity of the labouring class, which he absorbed from his mentor, Lewis Hine. Overall, Strand’s profoundly humanist scenes of everyday life influenced a generation of socially conscious photographers who documented the 20th-century crises of the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, World War II, and more.

Heinrich Kühn

In the late 19th century, European Pictorialism was divided into two camps. On the one side were the purist photographers who, aside from a softening of the lens, opposed extensive manipulation of the negative or the print for artistic effect. On the other side were those who derided “button-pushers” and viewed the “straight” photograph as merely the raw material from which to create an artistic print through elaborate handiwork.

The leader of this latter camp was Heinrich Kühn (1866-1944). Eschewing Modernist tendencies, he chose traditional subject matter of painting from the 17th through 19th centuries: still life, figural studies, and genre scenes. His preference for gum-bichromate and bromoil printmaking techniques, which allowed for extensive manipulation, were intended to provoke the reaction in the viewer: is that really a photograph?

Born in Dresden, Kühn moved to Innsbruck, Austria, after youthful studies in science and medicine. Thanks to a sizeable inheritance, he could devote himself to artistic photography, joining both the Linked Ring in London and Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession in the United States. A trans-Atlantic correspondence with Stieglitz began in 1899 and lasted three decades. They congratulated one another on their latest triumphs and encouraged each other through professional and personal disappointments. In 1909, with Stieglitz’s assistance, Kühn organised the International Photographic Exhibition in Dresden, one of the high points of Pictorialism.

Later in life, Kühn filed multiple patents in photochemistry and camera technology related to Pictorialist photography, but none earned him any money. Tastes had changed, and the painterly photograph had become a quaint curiosity.

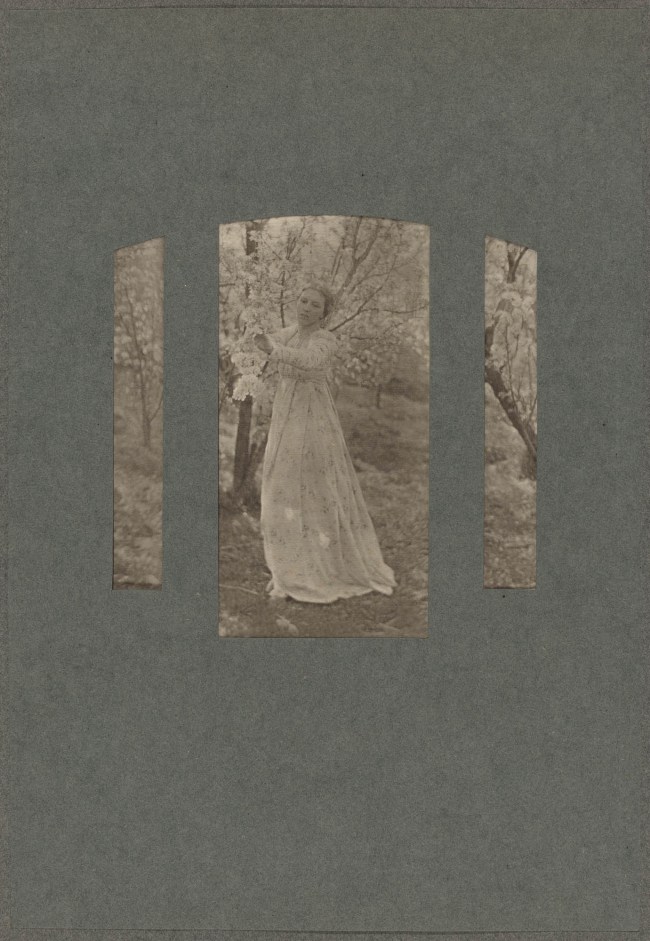

Gertrude Käsebier

Gertrude Käsebier (1852-1934) was 37 years old, married, and had three children by the time she began studying art at the Pratt Institute. She had originally purchased a camera to make portraits of her children, but Pratt encouraged its women students to earn a living in the arts. By 1897 she opened a one-room commercial portrait studio in New York City. Her ambition was to make “not maps of faces, but likenesses that are biographies, to bring out in each photograph the essential personality that is variously called temperament, soul, humanity.”

Recognition for Käsebier’s talent and ability came swiftly. In 1898 the painter William Merritt Chase, judging the Philadelphia Photographic Salon, called her work “as fine as anything that [Anthony] Van Dyck has ever done.” For Stieglitz, who organised her first solo show in 1899 at the Camera Club of New York, Käsebier was “beyond dispute the leading portrait photographer in this country.” That year, she sold one of her photographs for the unheard-of sum of $100 (almost $3,800 today).

However, by the time that the Brooklyn Museum honoured Käsebier with a career retrospective in 1929, Pictorialist photography had fallen so far out of fashion that the exhibition was not even reviewed in major journals.

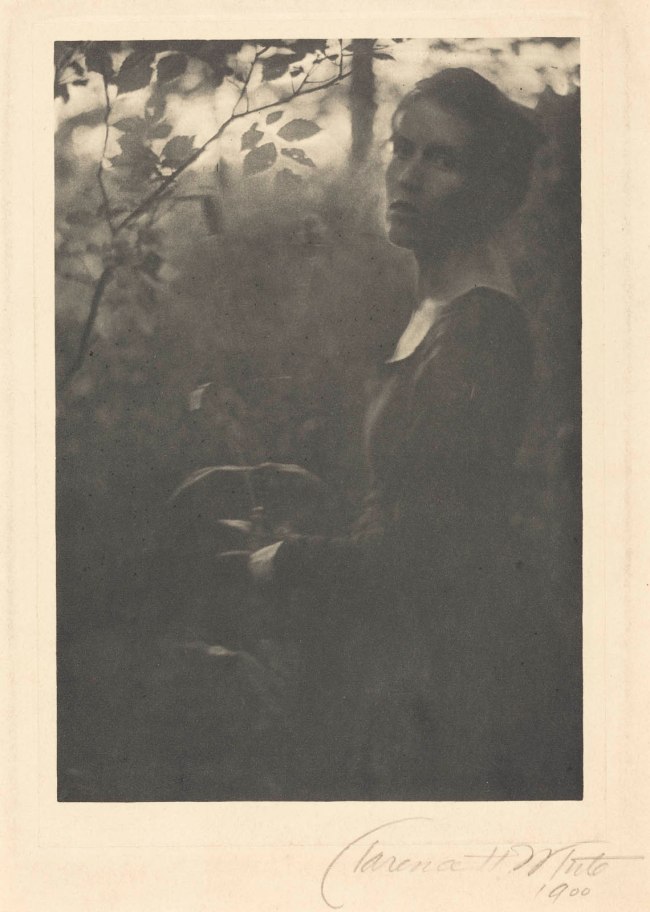

Clarence Hudson White

Clarence Hudson White (1871-1925) was a modest, soft-spoken, entirely self-taught genius from America’s heartland. Raised in the small town of Newark, Ohio, he eked out a living as a bookkeeper for a wholesale grocer; each week he saved enough to purchase two glass plates for his camera. He specialised in gorgeously back-lit domestic interior scenes featuring his friends and members of his close-knit extended family.

White’s contributions to the 1898 Philadelphia Photographic Salon were so highly praised that, like Gertrude Käsebier, he was appointed a judge for the following year. The annual salons of the Newark Camera Club that he organised featured the nation’s preeminent Pictorialists and were the direct precursor to Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession. Indeed, the 1900 salon featured his friend and latest discovery, Edward Steichen of Milwaukee.

From 1907 onwards, both in New York City and during summers in rural Maine, White was also America’s foremost teacher of photography. Many of the leading American photographers of the 20th century studied at the Clarence White School.

Paul Strand

In 1915 Alfred Stieglitz found in the young Paul Strand (1890-1976) the leader of a remarkable new direction in photography. Strand had been a senior at the Ethical Culture High School in 1907 when he first visited Gallery 291 on a class trip with his photography teacher, Lewis Hine, whose poignant documents of immigrants and child labor were staples of the Progressive Movement. Eight years later, after thousands of hours in the darkroom at the New York Camera Club, Strand returned to 291 with a portfolio of platinum prints that pointed the way to a new era. Stieglitz deemed them “brutally direct, devoid of all flim-flam, devoid of trickery and of any ‘ism’. These photographs are the direct expression of today.” Stieglitz not only offered Strand an exhibition at 291, but also devoted the final two issues of Camera Work exclusively to him.

What was so compelling and inspiring to Stieglitz in Strand’s photography? His portfolio contained pictures of urban street life and architecture, as well as powerful close-ups of weathered New York faces (influenced by Lewis Hine), boldly composed still lifes, and shadow abstractions taken on a porch in Twin Lakes, Connecticut.

As for photography’s future, Strand and Stieglitz saw eye to eye. In his essay in Camera Work, Strand called for the universal adoption of Straight Photography “without tricks of process or manipulation.” In a provocative lecture at the Clarence White School, Strand condemned “this so-called pictorial photography, which is nothing but an evasion of everything photographic.”

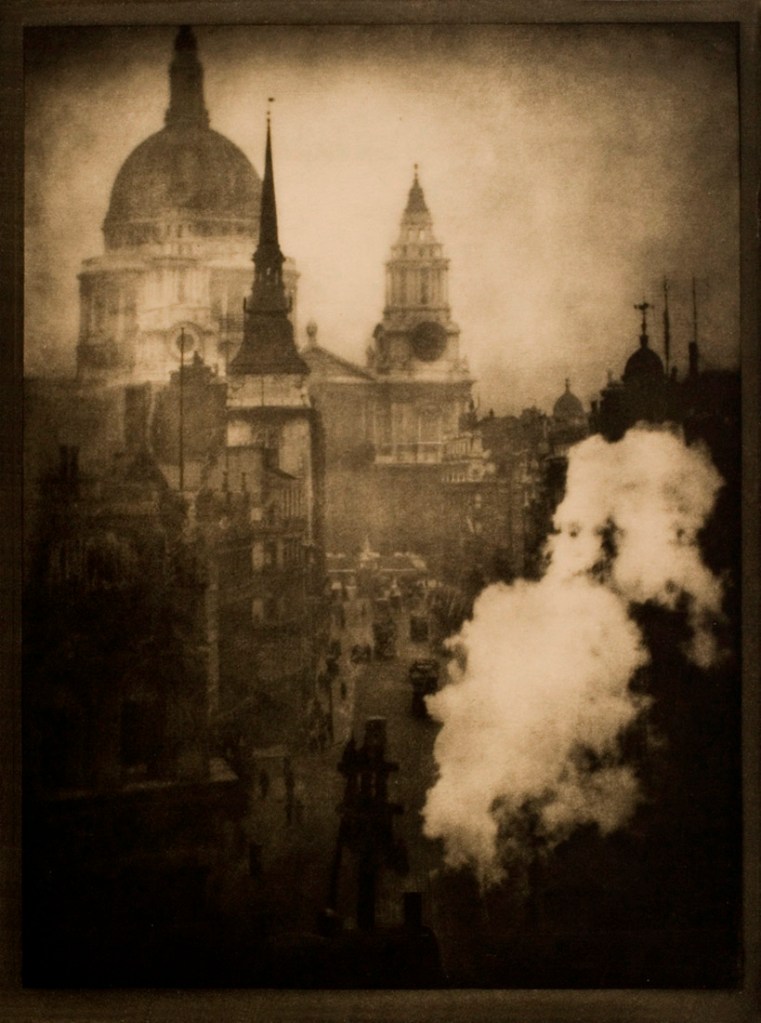

Works by Emerson, Post, Evans, and Sutcliffe

Frank Meadow Sutcliffe (British, 1853-1941)

The Water Rats

1886

Platinum print on paper

Sutcliffe was a member of the British photographic society the Linked Ring, which sought to make their work recognised as fine art. He operated a portrait studio in the seaside town of Whitby in North Yorkshire but is remembered for his charming, naturalistic depictions of local life. This photograph resulted in his excommunication by local clergy for its “corrupting” effects. Today this is his best-known photograph, regarded as a study of pure childhood joy.

Frederick H. Evans (British, 1853-1943)

Poplars on a French River

c. 1900

Platinum print on paper

Peter Henry Emerson (British born Cuba, 1856-1936)

Gathering Water Lilies

c. 1885

Platinum print on paper

In addition to his photographic work, Emerson wrote persuasively that photography could match – and even surpass – painting as an emotive art form. His writings were influential to the young Alfred Stieglitz, with whom he corresponded over four decades.

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Works by Thiollier

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Landscape in Bugey

c. 1885

Carbon print on paper

Thiollier’s photographic career is a fairly recent discovery, highlighted in the first ever retrospective of his career at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris in 2012.

From the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

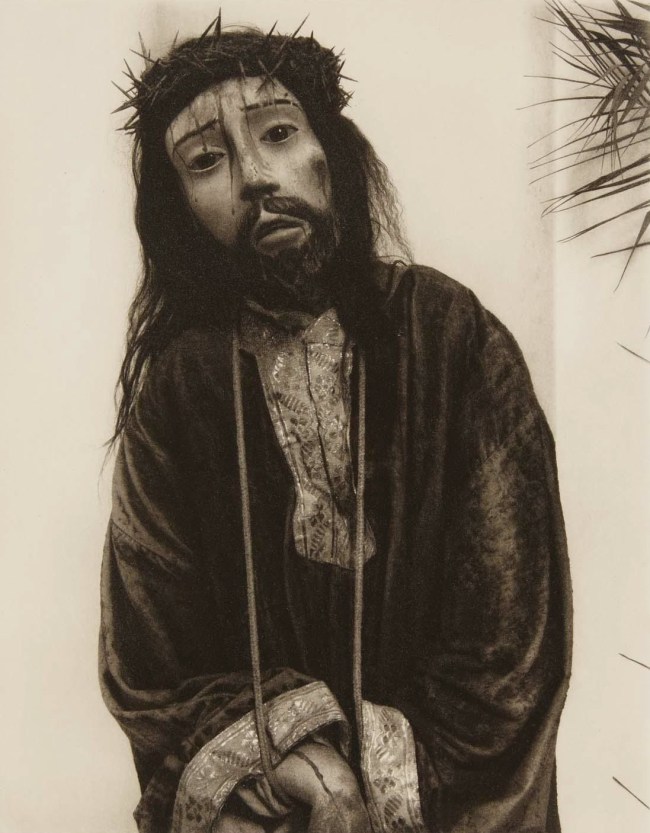

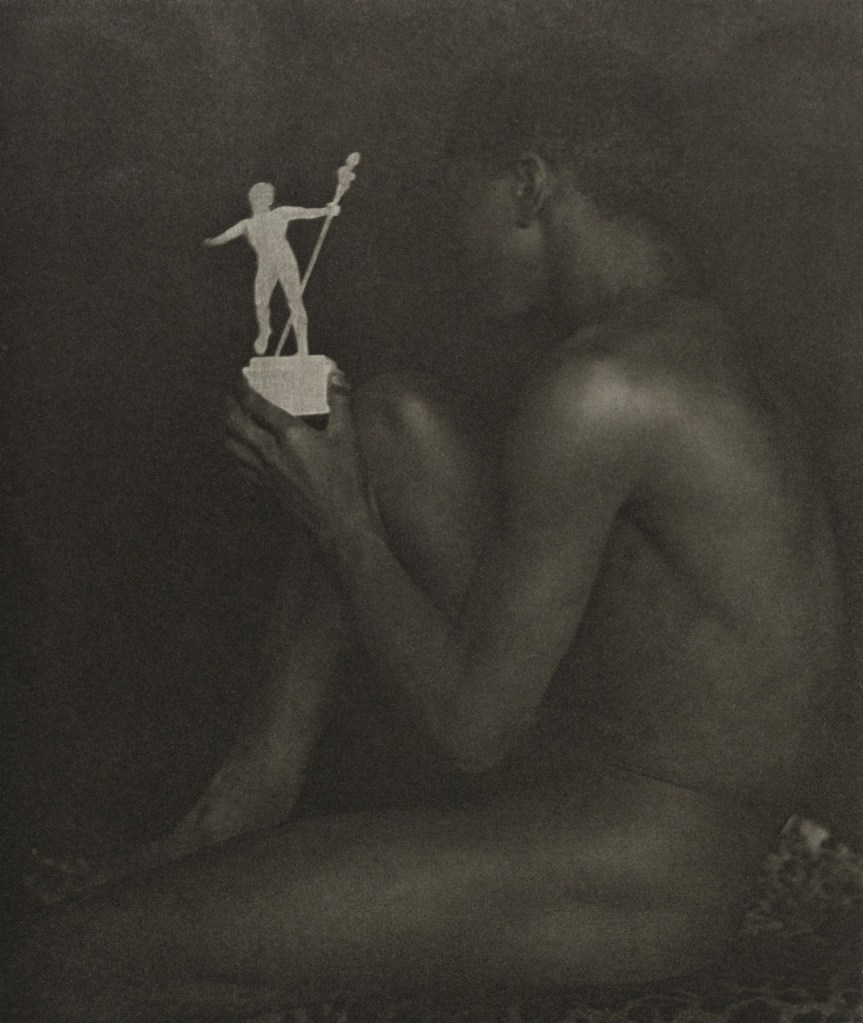

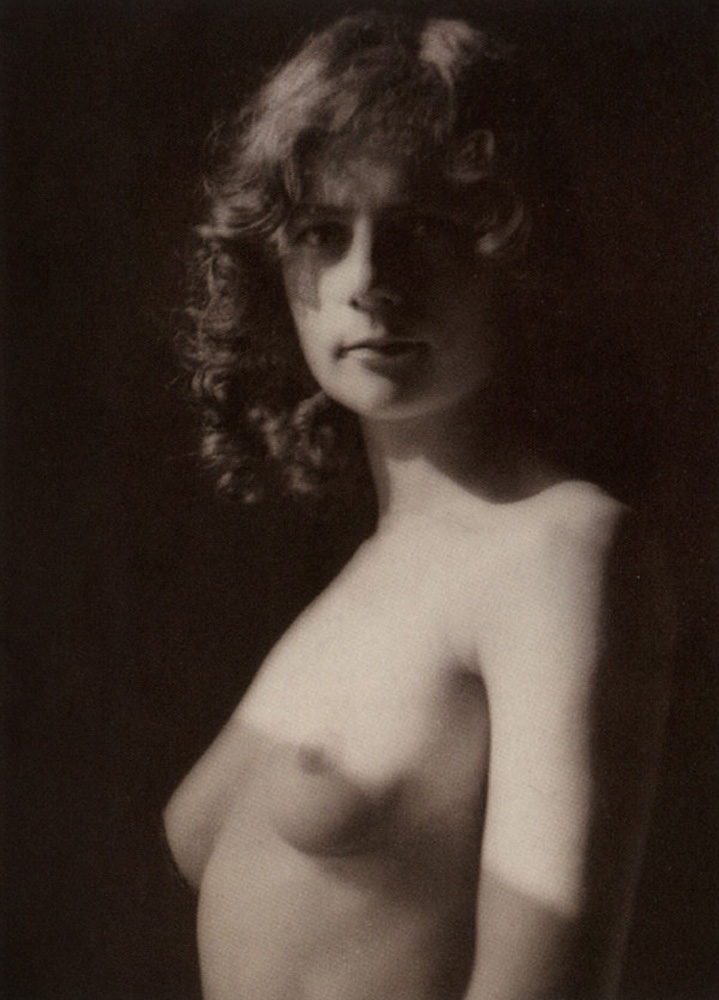

Works by Kühn

Heinrich Kühn (Austrian born Germany, 1866-1944)

Nude in Morning Sun

c. 1920

Multiple bromoil transfer print on Japanese tissue paper

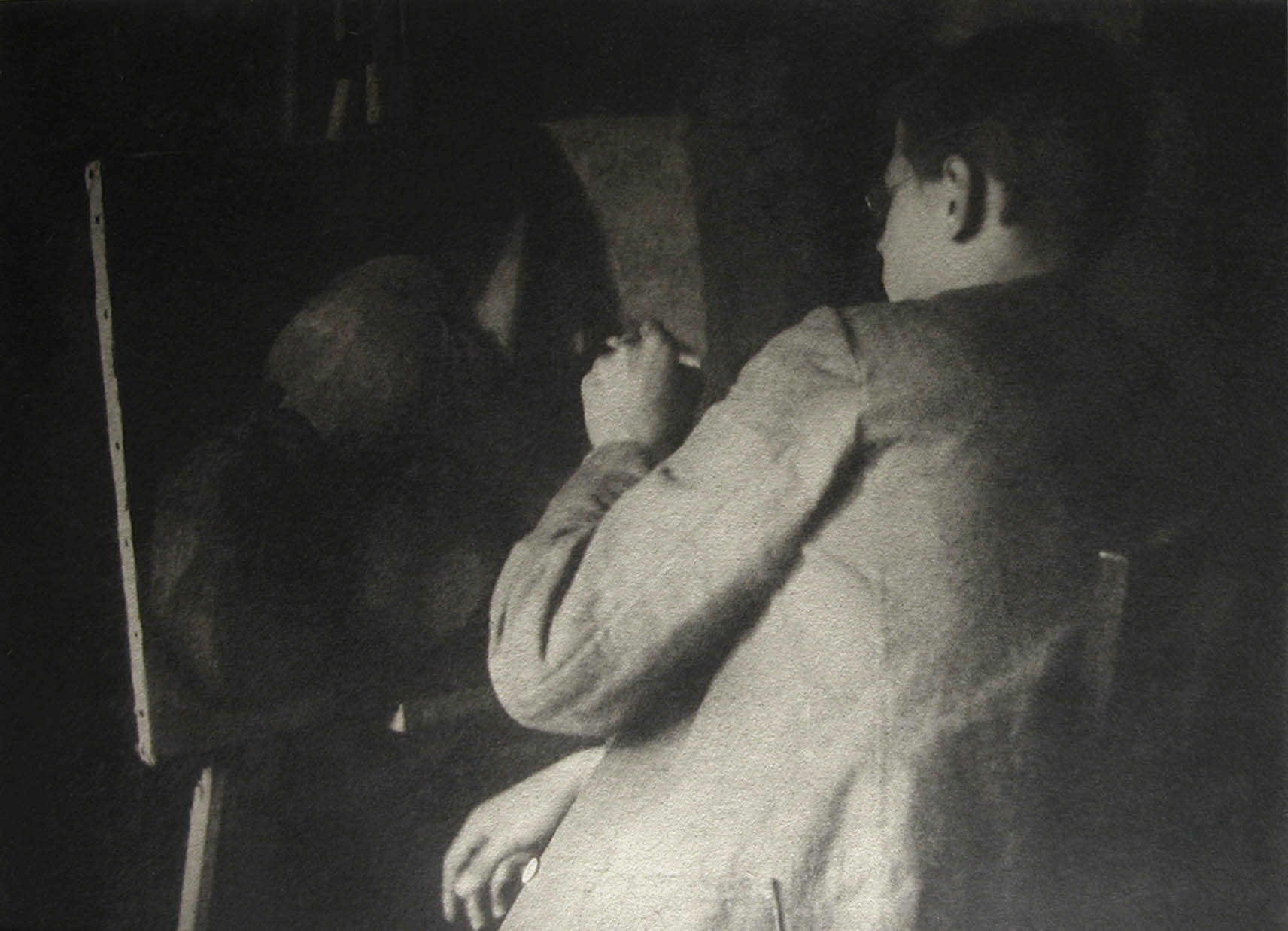

Heinrich Kühn (Austrian born Germany, 1866-1944)

Female torso in sunlight

c. 1920

Heinrich Kühn (Austrian born Germany, 1866-1944)

Walter at Easel

c. 1909

Gum-bichromate print on paper

Heinrich Kühn (Austrian born Germany, 1866-1944)

Still Life with Fruit and Pottery

c. 1896

Gum-bichromate print on paper with an applied watercolour wash

Kühn’s still lifes deliberately recall paintings from earlier centuries. This scene – his first published image – contains similar elements to 17th-century still-life compositions. He even included insects, which are traditional references to mortality called memento mori (reminders of death). Can you spot the housefly?

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Portraits by Steichen

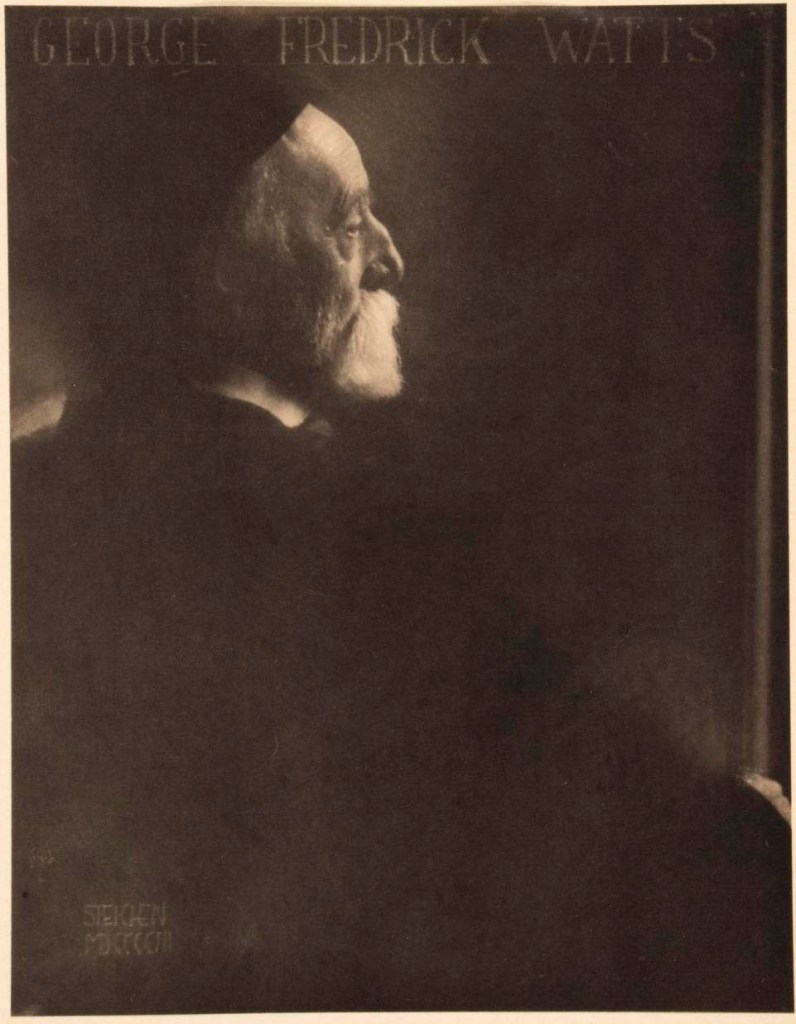

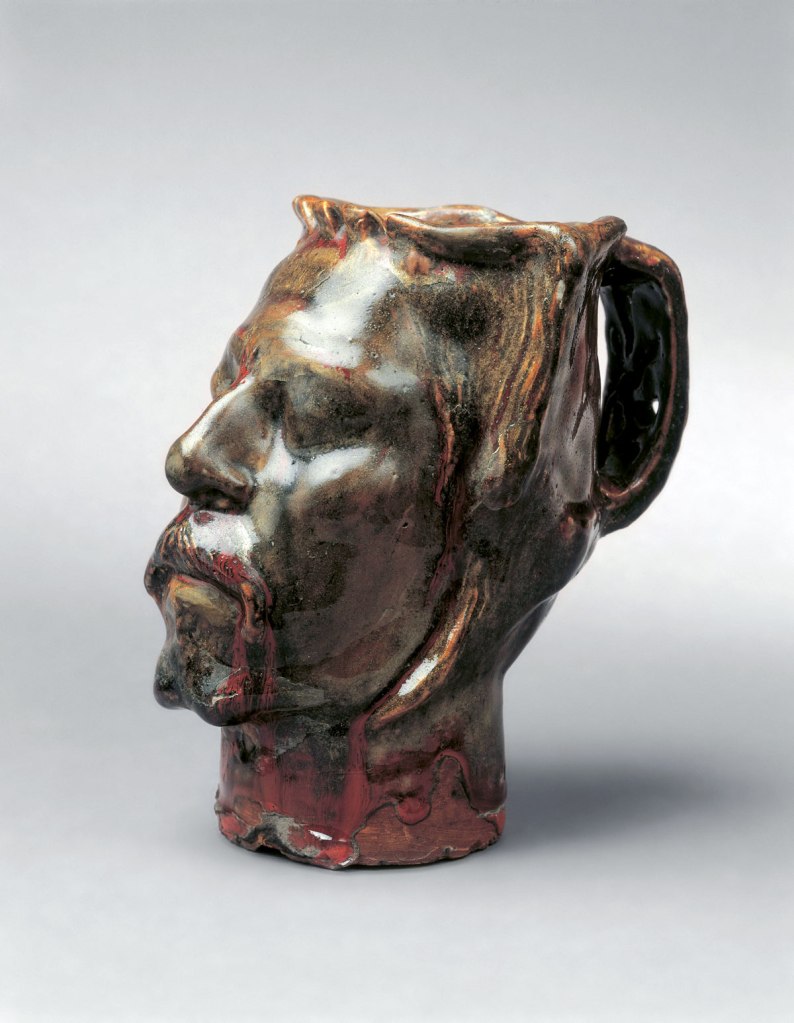

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

George Frederic Watts, London

1901

Varnished platinum print on paper

This dramatic profile portrait of the English Pre-Raphaelite painter was the first in what Steichen termed his “Great Men” series. Steichen wrote about his approach to portraiture, “I aim for the expression of something psychological. I am not satisfied with the mere reproduction of features and expression.”

Published in Camera Work, 14, 1906

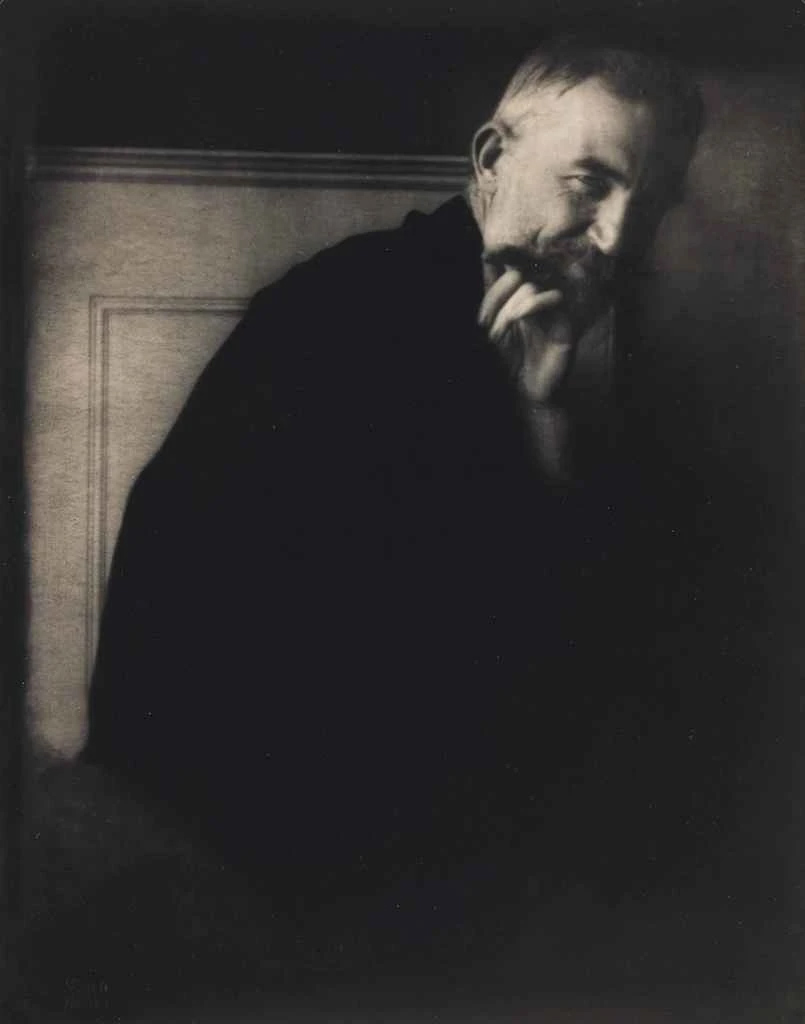

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

The Photographer’s Best Model: George Bernard Shaw, London

1907

Platinum print on paper

Steichen was elated after his photographic sitting with Shaw, writing to Stieglitz: “Well I’ve seen and done Shaw (photographically of course). He’s the nicest kind of fellow imaginable – genial and boyish – there is a little of the sardonic about him as you see him but when you get the camera at him you are tempted with possibilities in that way. He seems to know a lot about photography and certainly skilfully bluffs you into believing he knows it all.”

Published in Camera Work, 42/43, 1913

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Glossary of Photographic Printing Methods and Terms from the History of Photography

Gelatin Silver Print

For over a century, from the 1880s until the digital era, the gelatin silver print was the most common technique for producing black-and-white photographs. The paper is coated with a binder layer of gelatin incorporating light-sensitive silver chloride or silver bromide. The paper is exposed under a negative, either by contact-printing or through an enlarger, then chemically developed, stopped, fixed, and dried. In the process, the silver salts are reduced to metallic silver, which carries the image. The overall color of the print can be altered through toning.

Cyanotype

A sheet of paper is sensitised in a solution of potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate. After contact-printing under a negative, the iron compounds form an insoluble blue (“cyan”) dye known as Prussian blue. Apart from its occasional artistic use, the only regular use of the cyanotype was in copying architectural plans, thus called “blueprints.”

Platinum or Palladium Print

A platinum print is produced by sensitising a sheet of paper with platinum and iron salts. The sheet is then contact-printed under a negative until a faint image is visible. The print is developed in a potassium oxalate solution that dissolves unexposed iron salts and transforms the platinum salts into metallic platinum, which intensifies the image. Mercury chloride can be added to the solution to give a warmer tone. Unlike a silver print, where the image lives in a gelatin binder layer on top of the paper (akin to a watercolour), the image in a platinum print is embedded in the paper fibres (akin to an oil painting). The rich mid-tone range and matte surface made the platinum print the favoured medium for the Pictorialist photographers, from P.H. Emerson onward. When the price of platinum spiked during World War I, palladium was introduced as a more affordable (and generally warmer-toned) substitute.

Pigment Prints

The following processes are known as pigment prints, because the photographic image is carried by inks or pigments, rather than by metallic particles like silver, iron, or platinum.

Gum Bichromate Print

A sheet of paper is coated with diluted gum-arabic mixed with coloured pigment and light-sensitive potassium bichromate. During exposure under a negative, the bichromate causes the coloured gum-arabic to harden in proportion to the amount of light received. The areas not exposed to light remain soluble in water, and the print is developed by washing away the soluble areas, leaving a positive image on the paper. The prints can be exposed and reprinted numerous times with different coloured pigments, as well as manipulated by brushing away more pigmented gum during the washing stage.

Bromoil (Transfer) Print

This process does not begin with a negative, but rather with a gelatin silver print that is bleached in a solution of potassium bromide. The bleaching removes the silver-based image and selectively hardens the underlying gelatin in proportion to the image density. The sheet is then hand-coloured with an oil-based ink, which is selectively absorbed depending on the hardness of the gelatin: the softer areas contain more water, which repels the oil-based ink. An inked print is sometimes used as a kind of printing plate for transferring the image to another sheet of paper (a bromoil transfer print).

Photogravure

This is a sophisticated photomechanical process used for reproducing photographs in ink in a large edition. It is a form of intaglio printing, in which a photographic image is acid-etched into a copper plate. The relief image is then inked and printed. Alfred Stieglitz’s magazine Camera Work was largely printed in photogravure.

The Photo-Secession

This was the brief but influential artistic movement led by American Alfred Stieglitz during the years 1902–1915 that championed photography as an art form that was as aesthetic, creative, and skilful as traditional media like painting, drawing, watercolour, and printmaking. The European artistic movement Secessionism inspired the name Photo-Secession, and both movements were committed to Modernism by seceding from centuries-old academic traditions.

Pictorialism / Pictorialist

The approach to photography in which artists sought to make images that imitated the tradition of paintings through photographic prints. Pictorialist photographers used soft focus lenses and manipulated both their negatives and printing media to create their prints.

The Linked Ring

Also known as the Brotherhood of the Linked Ring, this photographic society founded in 1892 in London promoted photography as a form of art and was influential for the American society of the Photo-Secession.

Straight Photography

The approach to photography in which artists use sharp focus and print directly from their negatives with minimal or no manipulation.

Camera Notes

Camera Notes was the journal of the Camera Club of New York, edited by Alfred Stieglitz from 1897 to 1902. Under Stieglitz’s editorship, the purposes of Camera Notes were “to take cognisance also of what is going on in the photographic world at large, to review new processes and consider new instruments and agents as they come into notice; in short to keep our members in touch with everything connected with the progress and elevation of photography.”

Camera Work

Camera Work was the journal about contemporary photography that Alfred Stieglitz edited and published with the assistance of Edward Steichen from 1903 to 1917. The goal of this journal “devoted largely to the interests of pictorial photography” was “to issue quarterly an illustrated publication which will appeal to the ever-increasing ranks of those who have faith in photography as a medium of individual expression, and, in addition, to make converts of many at present ignorant of its possibilities.”

This glossary has been edited from primary sources and text by Ina Schmidt-Runke, Meike Harder, and Andreas Gruber.

The Photo-Secession Movement: Pioneering Artistry in Early Photography

By Adelaide Ryder, head photographer and digital assets manager at the UMFA

The Birth of the Photo-Secession Movement

This fall the Utah Museum of Fine Arts will exhibit Photo-Secession: Painterly Masterworks of Turn-of-the-Century Photography. This exhibition of art photography from the early 20th century will be on view from August 24 to December 29, 2024. Who were the Photo-Secessionists and why was their work so pivotal to the advancement of photography as an art form?

In the mid-19th century photography was regarded as a complex technical field that only a trained professional could do. By the 1880s, however, the hand-held camera had become affordable and easy to use, and the “snapshot” became commonplace. Smaller, easier-to-use cameras and the ability to send the film off to a lab for development gave the public accessibility to the medium in a new way. This technological advancement greatly affected the professional photography business, as people began to question the skills needed to make a photograph when “anyone could push a button.”

How did photographers respond to this shift in aesthetics and business? Many searched for ways to use photography to express abstract ideas or subjective points of view, shifting from using photography to document objective likeness to illustrating subjective conditions or the subject’s inner state. This helped elevate the photographer’s status, as the expressive ability of the person behind the camera became as important as the subject. Photographers embraced symbolism and started printing with complex techniques like gum bichromate to elevate their craft above the basic snapshot. Two significant movements were born from this struggle to gain recognition as a legitimate form of artistic expression rather than simply a means of mechanical documentation: Pictorialism and the Photo-Secession.

The camera was seen as a tool, and many felt that photographs visually lacked the “artist’s hand,” an essential factor in calling something “art.” The Photo-Secession movement, founded by Alfred Stieglitz in 1902, aimed to change this perception. Stieglitz and his contemporaries believed photography deserved the same artistic consideration as painting and sculpture. They aimed to elevate photography to fine art, emphasizing the photographer’s vision and creativity over mere technical skill. Stieglitz said the Photo-Secession was founded “loosely to hold together those Americans devoted to pictorial photography in their endeavour to compel its recognition, not as a handmaiden of art, but as a distinctive medium of individual expression.” (Camera Work, no. 6, April 1904.)

The Photo-Secession movement emerged from the broader Pictorialist movement, which dominated photographic art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While both movements sought to establish photography as an art form, the Photo-Secessionists emerged with their own philosophy.

Similarities

Artistic Expression: The Photo-Secession and Pictorialism emphasized the photographer’s role as an artist rather than a mere technician. They believed that photography should convey the photographer’s vision and emotional intent.

Aesthetic Quality: Both movements valued the aesthetic quality of photographs. They often employed techniques like soft focus, manipulation of light, and careful composition to create visually striking images.

Influence of Painting: Both were heavily influenced by the aesthetics of painting, particularly Impressionism and Symbolism. They sought to create images that were painterly in style, blurring the lines between photography and traditional fine arts.

Differences

Philosophical Focus: Pictorialism focused on creating images that looked like paintings, often using elaborate darkroom techniques to achieve a painterly effect. Photo-Secession, while also influenced by painting, emphasised the photographer’s personal expression and the inherent qualities of the photographic medium, sometimes even embracing the “snapshot” aesthetic if it helped to illustrate more hidden ideas and thoughts.

Technical Innovation: The Photo-Secessionists were more open to embracing the amateur artist and experimentation in techniques and technologies, whereas the Pictorialists held on to the traditional hierarchy of the European artistic schools of the time. Photo-Secessionists saw innovation as a means to expand photography’s artistic potential.

Subject Matter: Pictorialists focused on romanticized and idealized subjects, such as landscapes, portraits, and allegorical scenes. The Photo-Secessionists, on the other hand, explored a wider range of subjects, including urban scenes, modern life, and abstract forms. They embraced art movements like Cubism and Futurism, reflecting a broader and more progressive vision of art.

Exhibition and Display: The Photo-Secessionists were disenchanted with the outdated salons and gate-keeping ways of many photo schools commonly practiced in Europe. They began publications like The American Amateur Photographer, Camera Notes, and Camera Work to help give a platform to young photographers and people practicing these new ways of image making.

Adelaide Ryder. “The Photo-Secession Movement: Pioneering Artistry in Early Photography,” on the UMFA website Nd [Online] Cited 22/10/2024

Who were the Photo-Secessionists?

Works by Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz: The Visionary Leader

Alfred Stieglitz was a driving force behind the Photo-Secession movement. His passion for photography galvanized his dedication to promoting it as an art form. He saw photography as a means of personal expression. He helped catapult the idea that image-making can happen in the darkroom, during the printing process, as much as in the camera.

Stieglitz’s photograph The Steerage (1907, below) is one of the most iconic images in the history of photography. This powerful image captures the crowded lower deck of a transatlantic steamer, where people traveled in steerage class, the part of the ship with accommodations for those with the cheapest tickets. The Steerage is celebrated for its striking composition, which combines geometric shapes and human forms to create a dynamic and balanced visual narrative. Stieglitz considered this photograph one of his most outstanding achievements, as it encapsulated his transition to straight photography, which embraced photographs looking like photographs rather than the painterly qualities of Pictorialism. This photograph shows his ability to convey the complexity and depth of human experience through a single image. The photograph is a masterpiece of visual artistry and a compelling social document, reflecting the conditions and aspirations of early 20th century immigrants.

Adelaide Ryder. “The Photo-Secession Movement: Pioneering Artistry in Early Photography,” on the UMFA website Nd [Online] Cited 22/10/2024

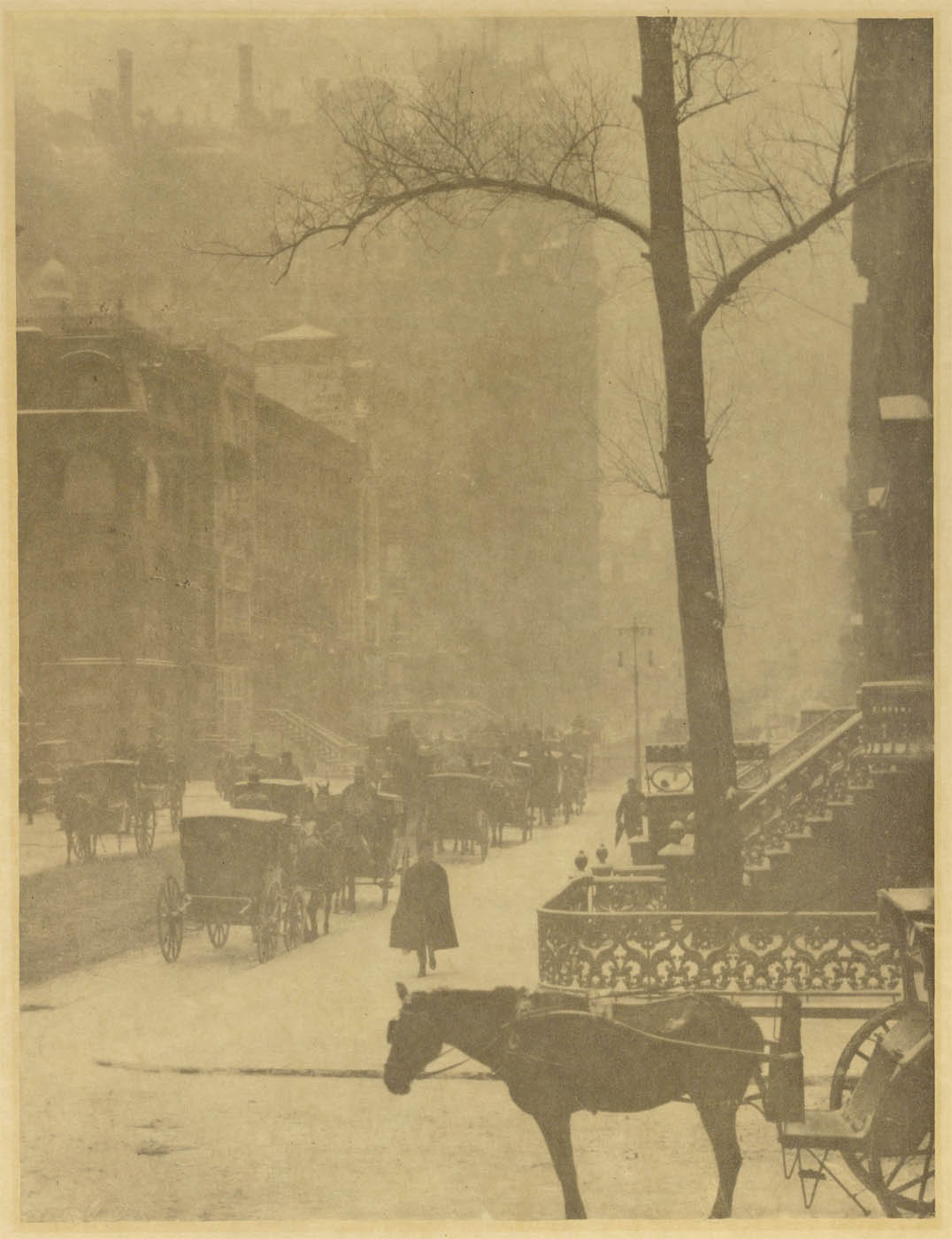

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

The Steerage

1907

Hand-pulled photogravure on paper

This photograph has become the iconic image of the Photo-Secession and has legendary status. In June 1907 he sailed to Europe to visit family and booked a first-class cabin. On a stroll around the ship, he encountered a bustling scene of labourers and their families traveling in steerage class, the part of the ship with accommodations for those with the cheapest tickets. With a single four-by-five-inch glass plate left in his camera, Stieglitz shot what would be regarded as a definitive masterpiece of both photography and Modernism.

About making this picture Stieglitz recalled: “There were men and women and children on the lower deck of the steerage. There was a narrow stairway leading to the upper deck of the steerage, a small deck right on the bow of the steamer. To the left was an inclining funnel and from the upper steerage deck there was fastened a gangway bridge that was glistening in its freshly painted state. It was rather long, white, and during the trip remained untouched by anyone. On the upper deck, looking over the railing, there was a young man with a straw hat. The shape of the hat was round. He was watching the men and women and children on the lower steerage deck. A round straw hat, the funnel leaning left, the stairway leaning right, the white drawbridge with its railing made of circular chains – white suspenders crossing on the back of a man in the steerage below, round shapes of iron machinery, a mast cutting into the sky, making a triangular shape. I saw shapes related to each other. I saw a picture of shapes and underlying that the feeling I had about life.”

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

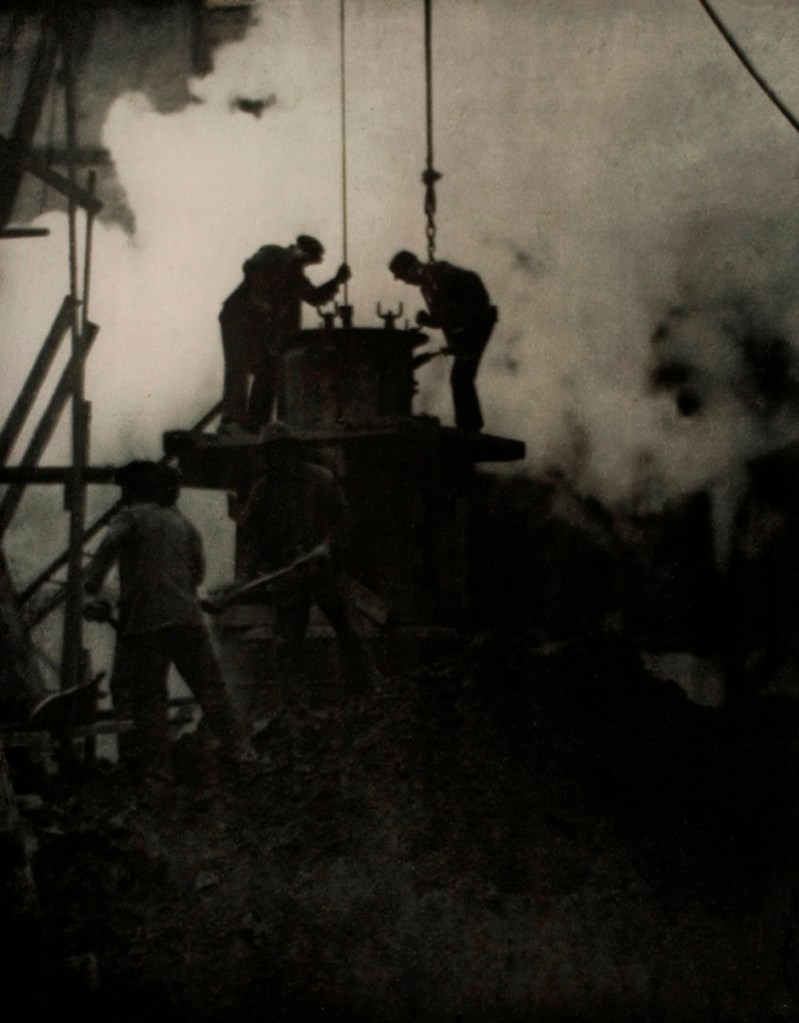

The Hand of Man

1902

Hand-pulled photogravure on paper

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Works by Käsebier

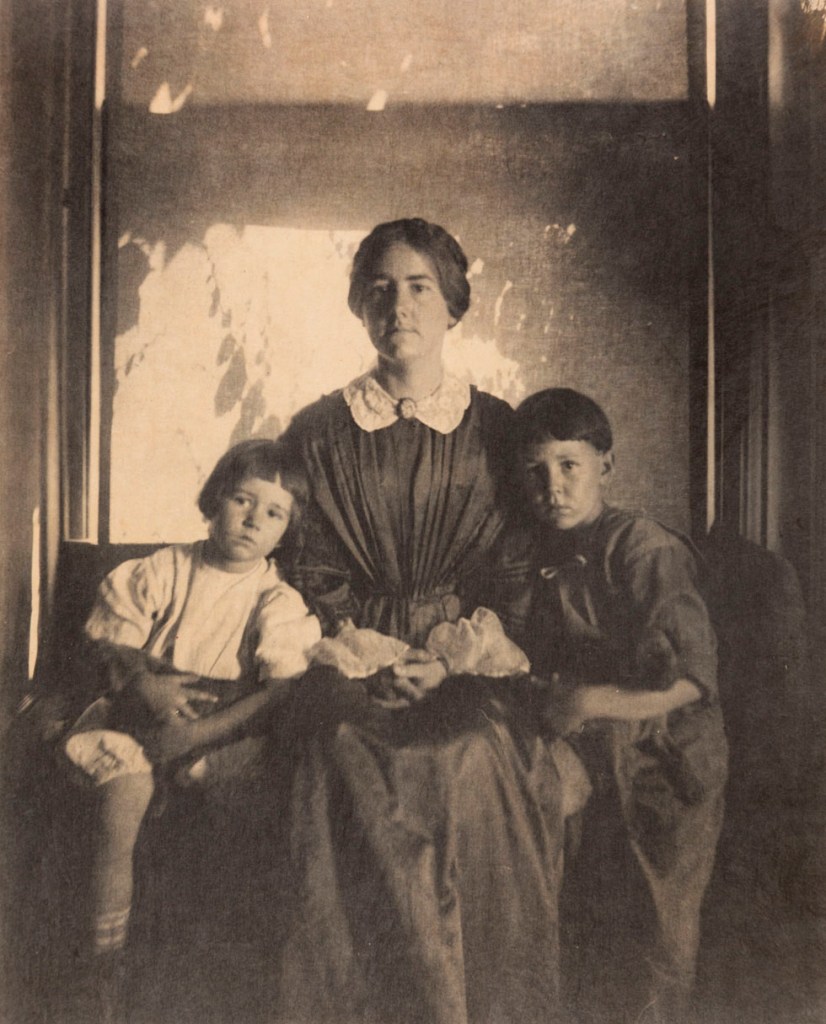

Gertrude Käsebier: The Master of Portraiture

Gertrude Käsebier was known for her compelling portraits and allegorical imagery. Käsebier’s work transcended traditional portrait photography by infusing her images with a deep sense of intimacy and character. She believed that a photograph should reveal the inner essence of its subject, and her portraits are renowned for capturing the personality and spirit of the people she photographed.

Käsebier’s approach to portraiture was both innovative and empathetic. This image from the UMFA’s permanent collection is a perfect example of how she photographed women and children, presenting them with dignity and respect at a time when they were not the usual subjects of portraiture. Her work challenged conventional representations and highlighted her subjects’ emotional depth and individuality.

Adelaide Ryder. “The Photo-Secession Movement: Pioneering Artistry in Early Photography,” on the UMFA website Nd [Online] Cited 22/10/2024

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

Untitled (Billiard Game)

c. 1909

Platinum print on paper

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

Mother and Two Children

1899

Platinum print on paper

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

Serbonne (A Day in France)

1901

Platinum print on paper

Both Pumpkin Pie, Voulangis and Serbonne (A Day in France) were set in France in 1901, when the artist was chaperoning art students. The young man in both scenes is Edward Steichen at age 22, whose interest in photography was then budding.

Serbonne is Käsebier’s chaste reference to Édouard Manet’s famous painting Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass) of 1863. An example of ultra-soft focus, this photo was reproduced in the inaugural issue of Camera Work, which was devoted to Käsebier.

Published in Camera Work, 1, 1903

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

The Heritage of Motherhood

1904

Gum-bichromate print on paper

This portrays the children’s book author Agnes Rand Lee in mourning after the sudden death of her daughter from illness. A contemporary photographer and critic deemed this image “one of the strongest things that Käsebier has ever done, and one of the saddest and most touching that I have ever seen.” Käsebier extensively manipulated the gum-bichromate process to make this print appear like a charcoal drawing.

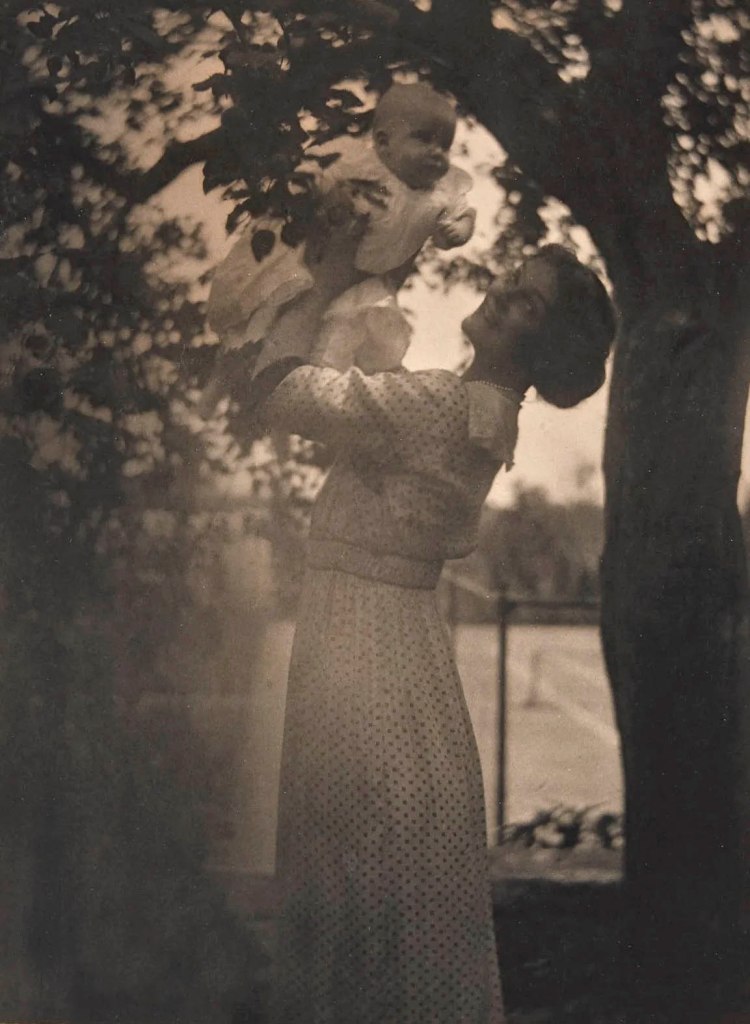

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

Mother and Child

c. 1900

Multiple gum-bichromate print on paper

The subject of mother and child was a frequent one for Pictorialists, especially Käsebier and Clarence White. The contrast between the tiny infant and the mighty tree gives this image additional symbolic meaning.

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

The Picture Book

1903

Platinum print on paper

Alfred Stieglitz had a print of this photograph in his personal collection, which he bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Published in Camera Work, 10, 1905

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Works by Evans

Frederick H. Evans (British, 1853-1943)

Aubrey Beardsley

1893

Platinum print on paper

Evans, a member of the British art photography group the Linked Ring, was close friends with prominent authors and artists, such as George Bernard Shaw and Aubrey Beardsley. Portrayed here around age 20, Beardsley was a talented artist, designer, and illustrator, whose promising career was cut short by tuberculosis just five years after this photo was made.

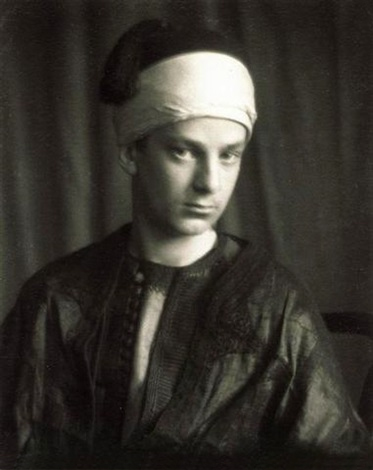

Frederick H. Evans (British, 1853-1943)

Alvin Langdon Coburn in Eastern Clothing

1901

Platinum print on paper

Coburn was a precocious young American artist. An eighth birthday gift of a Kodak camera sparked his interest in photography. By age 16 Coburn had moved to London to work with his cousin the photographer F. Holland Day, whose portrait by Gertrude Käsebier is in this exhibition. After being included in a landmark exhibition at the Royal Photographic Society, Coburn returned to New York and apprenticed with Käsebier. By the tender age of 20, he became a founding member of the Photo-Secession and launched an international career dividing his time between New York, London, and Paris.

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

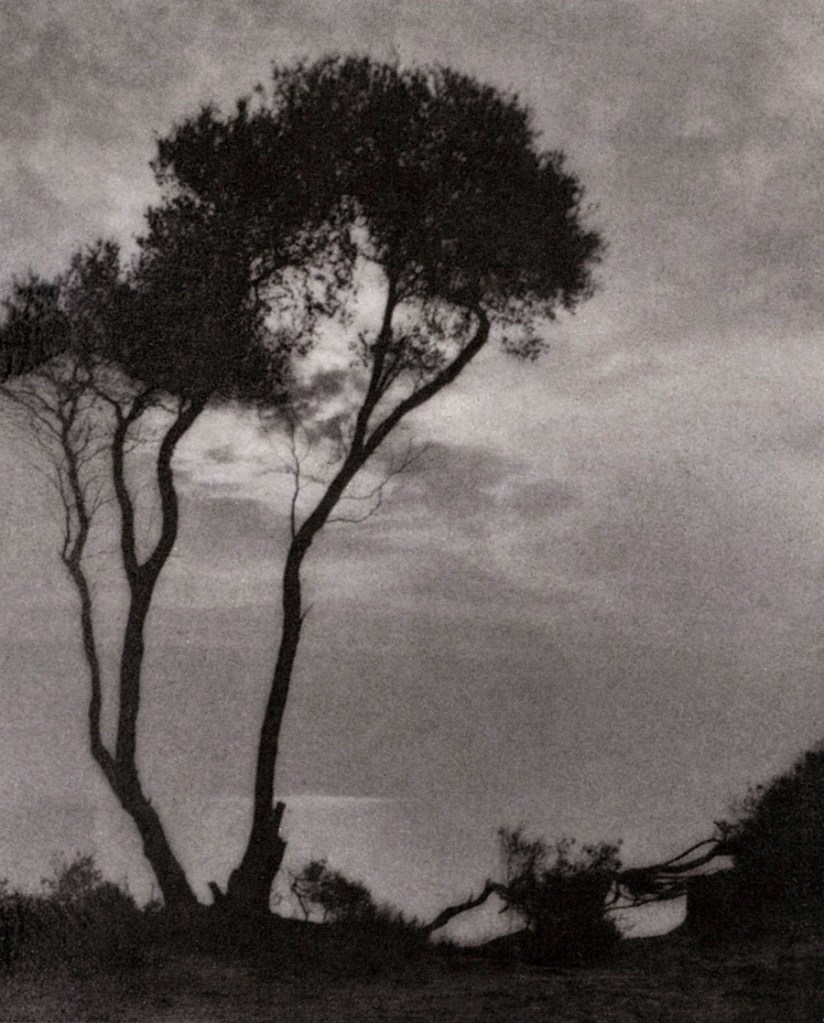

Works by Dow

Arthur Wesley Dow (American, 1857-1922)

Silhouetted Trees

c. 1910

Cyanotype print on paper

A painter, printmaker, and photographer, Dow is mainly remembered today as a pioneering educator who taught in New York at the Pratt Institute, Art Students League, and Teacher’s College of Columbia University. Among Dow’s students were Gertrude Käsebier, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Charles Sheeler, and Georgia O’Keeffe. Dow also hired Clarence White to teach photography at Columbia, thereby launching White’s important teaching career.

From the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

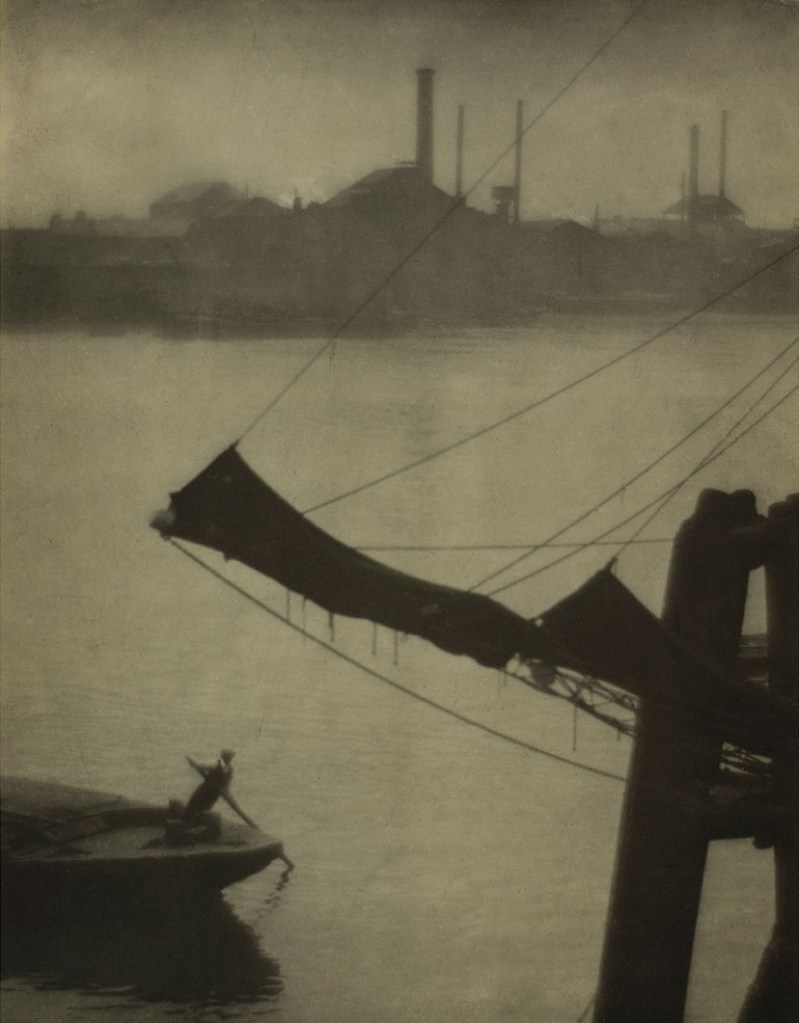

Works by Haviland

Paul Burty Haviland (American, 1880-1950)

Ship Deck

1910

Platinum print on paper

Haviland was an amateur photographer from a young age and grew up immersed in the arts. His grandfather was an early photography critic in Paris, and his father owned Haviland porcelain factory in Limoges, France. As the New York representative of the family business, Haviland happened to meet Alfred Stieglitz in 1908. Just two years later he became associate editor of Camera Work and helped financially support Stieglitz’s gallery 291.

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Works by Struss

Karl Struss (American, 1886-1981)

Cables

1912

Gelatin silver print on paper

Struss was a star pupil of Clarence White and became a favourite of Alfred Stieglitz and the youngest member of the Photo-Secession. He is best known for his compelling cityscapes of New York, including the view of the Singer Building through the cables of the Brooklyn Bridge and the dramatic Flatiron Building, Twilight.

Karl Struss (American, 1886-1981)

Flatiron Building, Twilight

c. 1915

Gelatin silver print on paper

Struss eventually broke away from Stieglitz and cofounded the society of the Pictorial Photographers of America along with Clarence White and Gertrude Käsebier in 1916. He … accepted a job as a cameraman for filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille. Struss would become one of the most prolific Hollywood cinematographers with 150 films, an Academy Award, and three Academy nominations to his credit.

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Nudes by Stieglitz and White

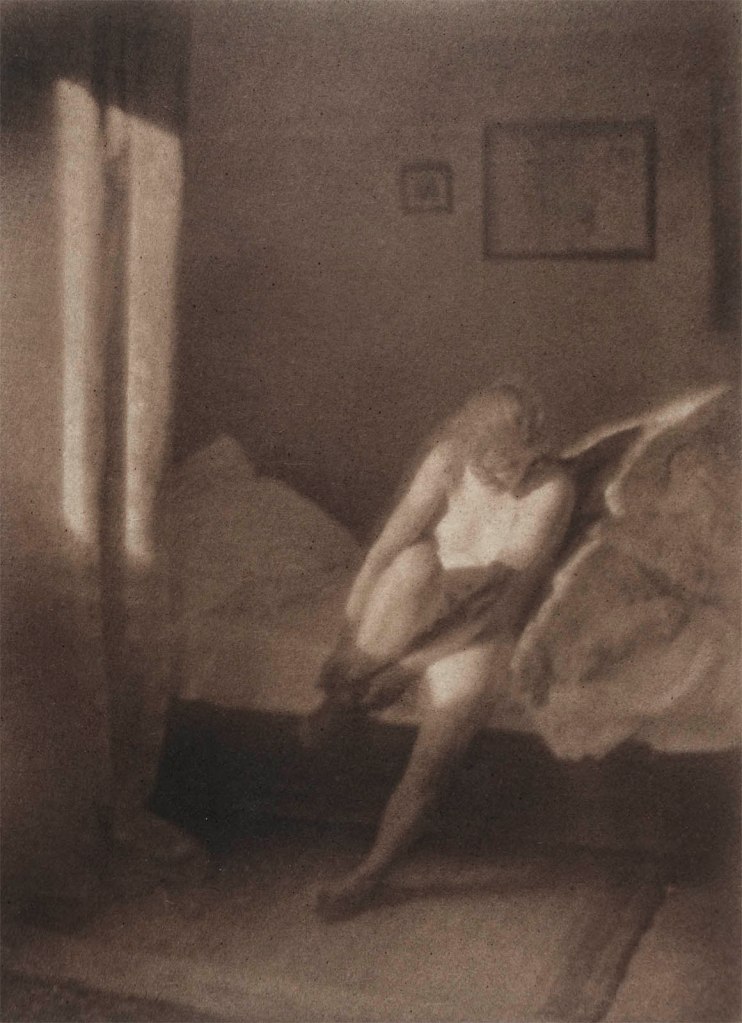

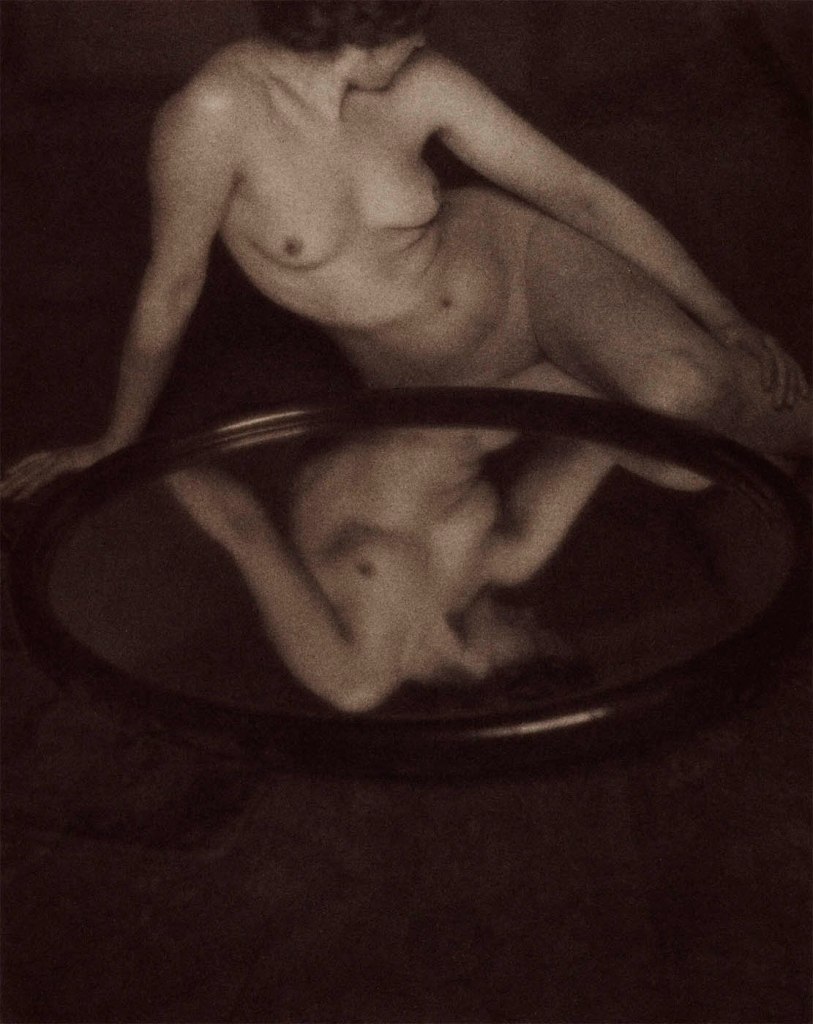

Clarence Hudson White (American, 1871-1925)

Reflected Nude

1909

Platinum print on paper

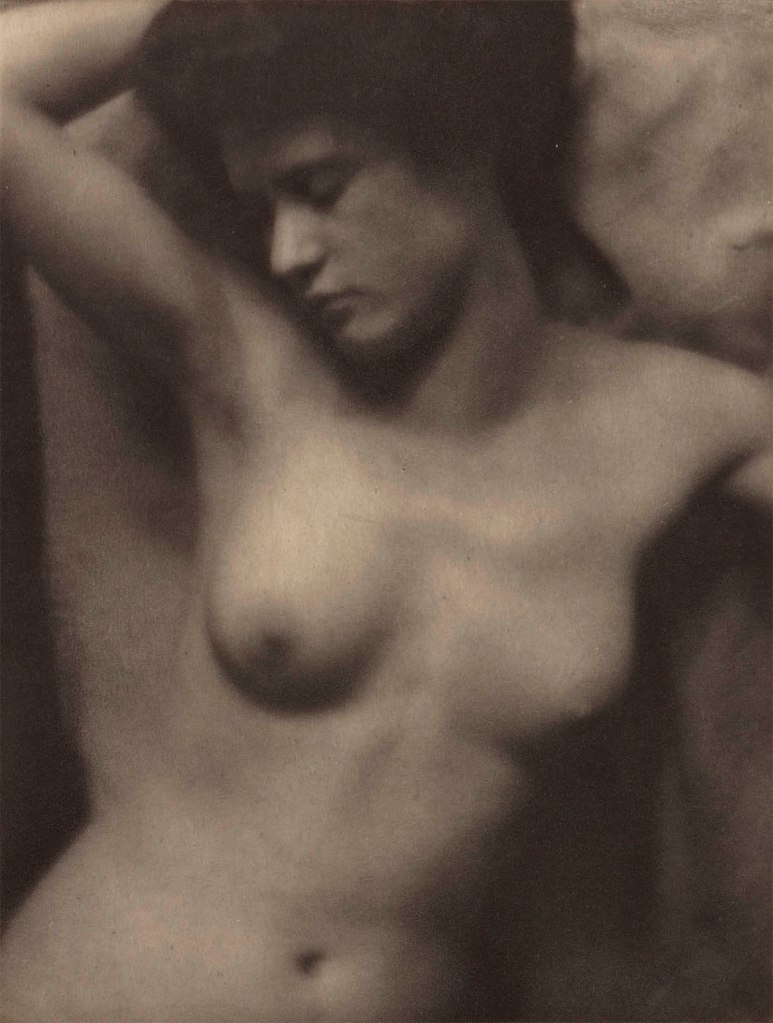

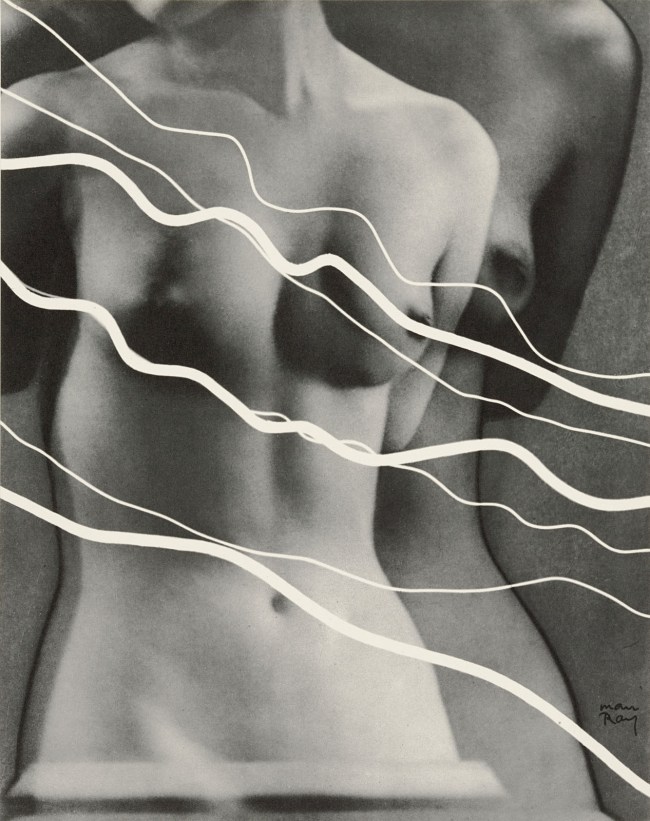

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) and Clarence Hudson White (American, 1871-1925)

Nude Posed in Doorway (Miss Thompson)

1907

Platinum print on paper

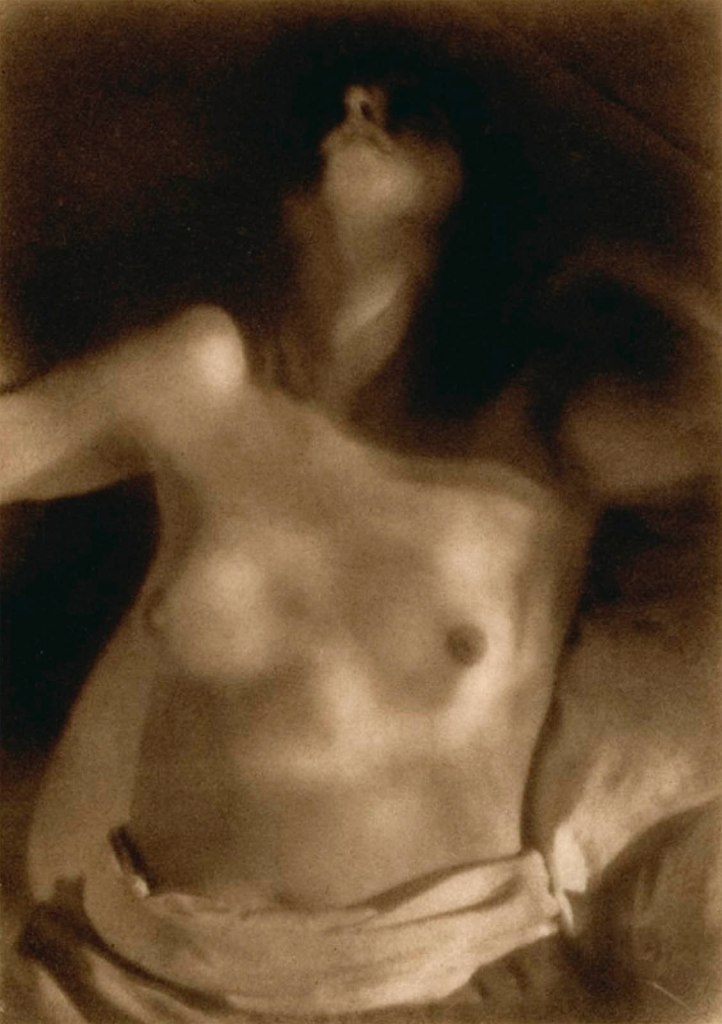

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) and Clarence Hudson White (American, 1871-1925)

The Torso

1907

Palladium print on paper

This is likely the most widely reproduced nude by Photo-Secession artists.

After their personal and professional rupture, Stieglitz wrote White a letter that specifically referred to their collaboration in 1907. Stieglitz insisted “that my name be not mentioned by you in connection with either the prints or the negatives” and further instructed White to erase his name from any prints they had jointly signed. Despite this vitriol, Stieglitz retained in his personal collection two prints of The Torso, one of them jointly signed in pencil.

Published in Camera Work, 27, 1909

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Images of O’Keeffe by Stieglitz

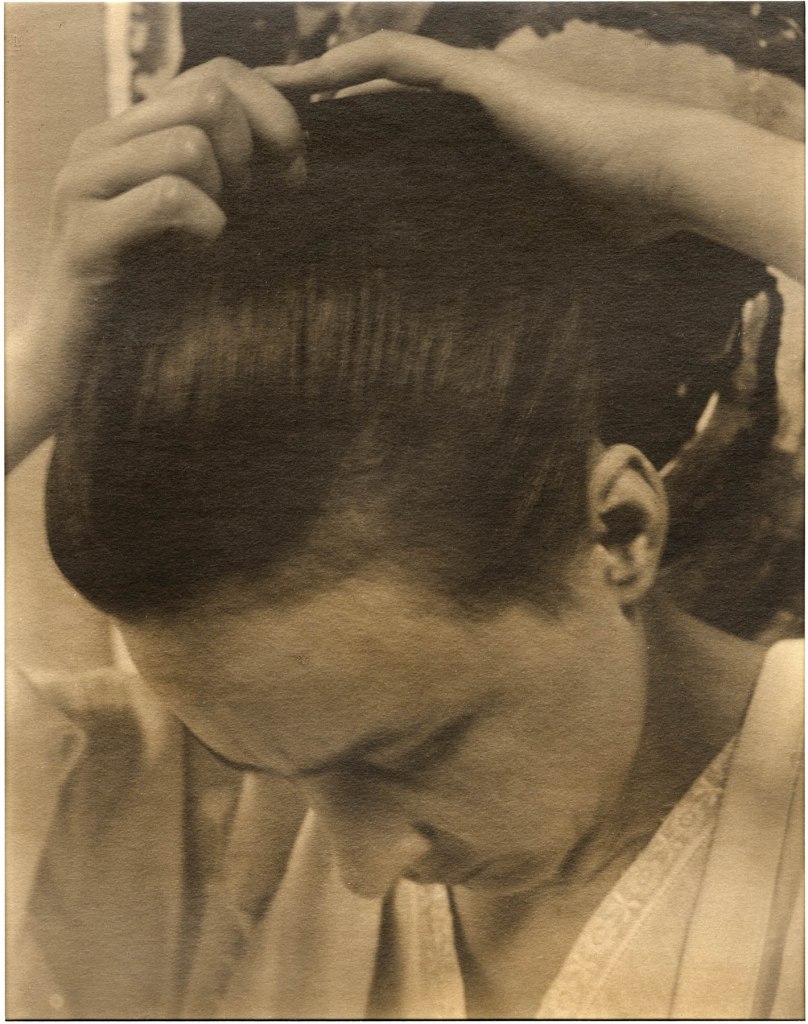

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe

1918

Palladium print on paper

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe (Fixing Hair)

1919-1921

Palladium print on paper

Over two decades, Stieglitz made over 300 photos of O’Keeffe, producing an extraordinary and candid portrait of the artist. She recalled, “I was photographed with a kind of heat and excitement and in a way wondered what it was all about.” The directness and intimacy of this series of photos differ from the idealised nudes that Stieglitz and White made together during the heyday of the Photo-Secession.

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Works by White

Clarence Hudson White: The Romantic

Clarence Hudson White was celebrated for his romanticised and intimate approach to photography. His 1904 image The Kiss perfectly illustrates his unique style. This platinum print on paper captures a tender moment with a soft focus and gentle lighting. The Kiss portrays an intimate scene imbued with a sense of emotional depth. White’s use of the platinum printing process, which provides a broad tonal range and exquisite detail, enhances the image’s delicate and dreamlike quality. His work reflects the movement’s early emphasis on creating photographs that evoke the emotional and aesthetic qualities of fine art while also paving the way for future explorations in photographic expression.

Adelaide Ryder. “The Photo-Secession Movement: Pioneering Artistry in Early Photography,” on the UMFA website Nd [Online] Cited 22/10/2024

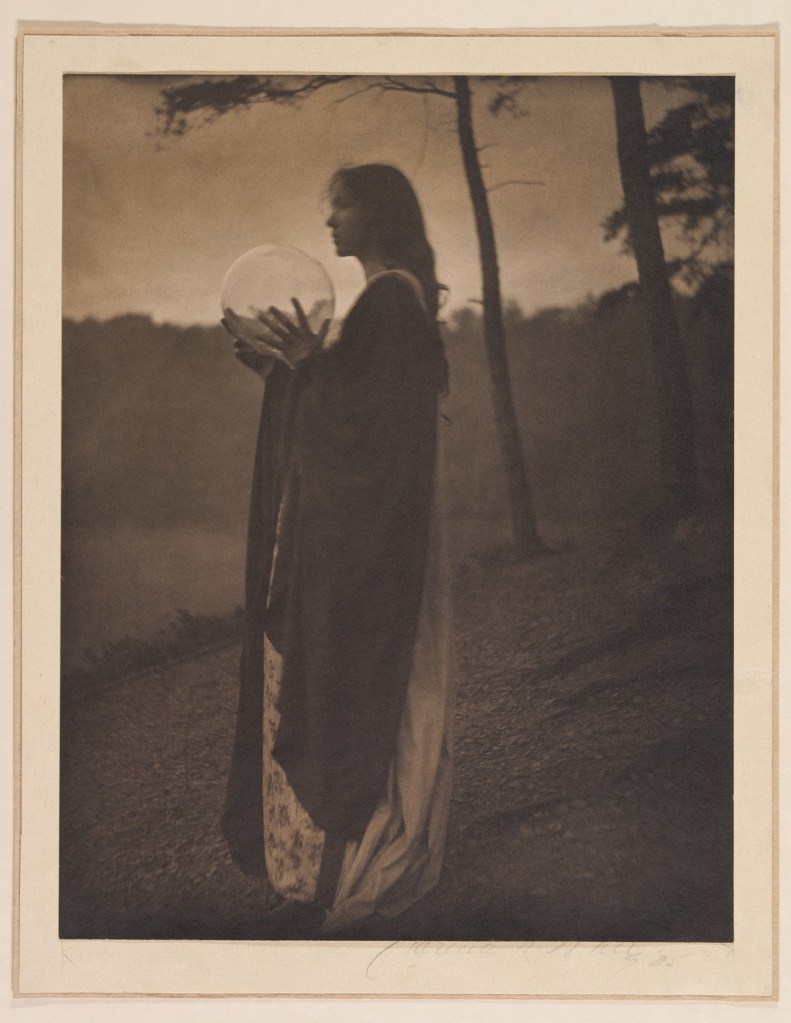

Clarence Hudson White (American, 1871-1925)

The Bubble

1898

Platinum print on paper

This image was exhibited at the 1898 Philadelphia Photographic Salon to great acclaim. Fellow photographer and critic Joseph Keiley commented, “Like most of Mr. White’s pictures, it is a well nigh perfect piece of composition whose subject with subtle poetry stimulates and leaves much to the imagination.”

Clarence Hudson White (American, 1871-1925)

The Mirror

1912

Platinum print on paper

Clarence Hudson White (American, 1871-1925)

The Kiss

1904

Platinum print on paper

This is one of White’s best known photographs. Despite his separation from White, Stieglitz kept prints of both The Kiss and The Bubble in his personal collection throughout his life.

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

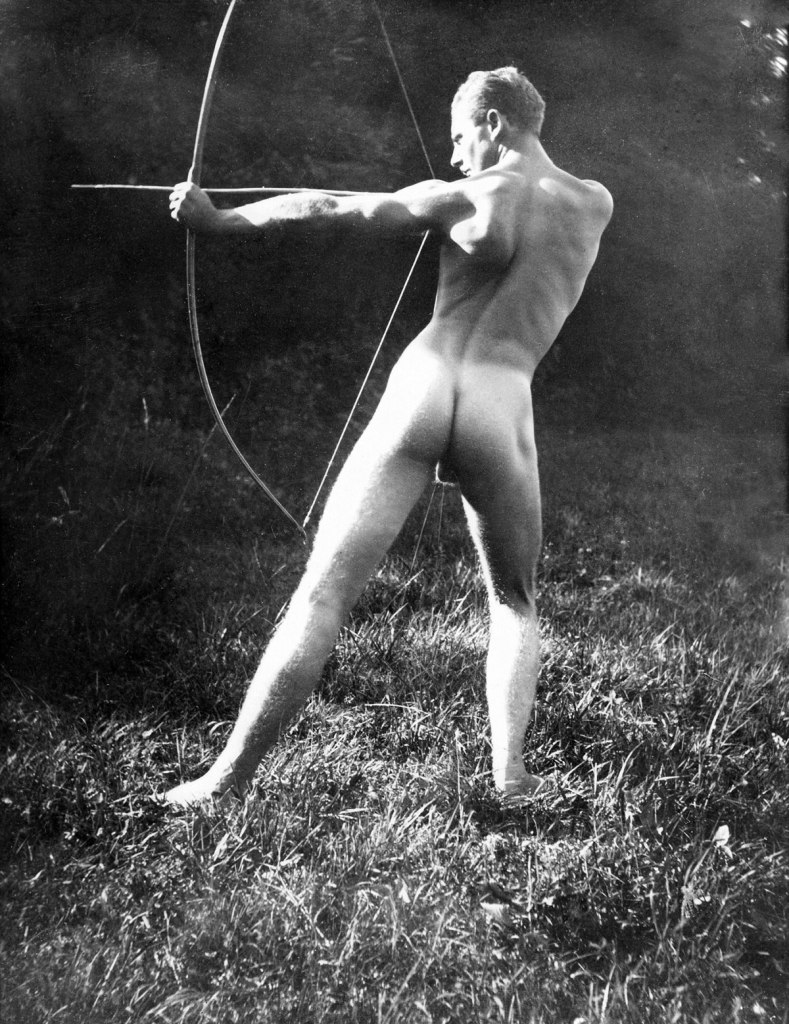

Works by followers of White

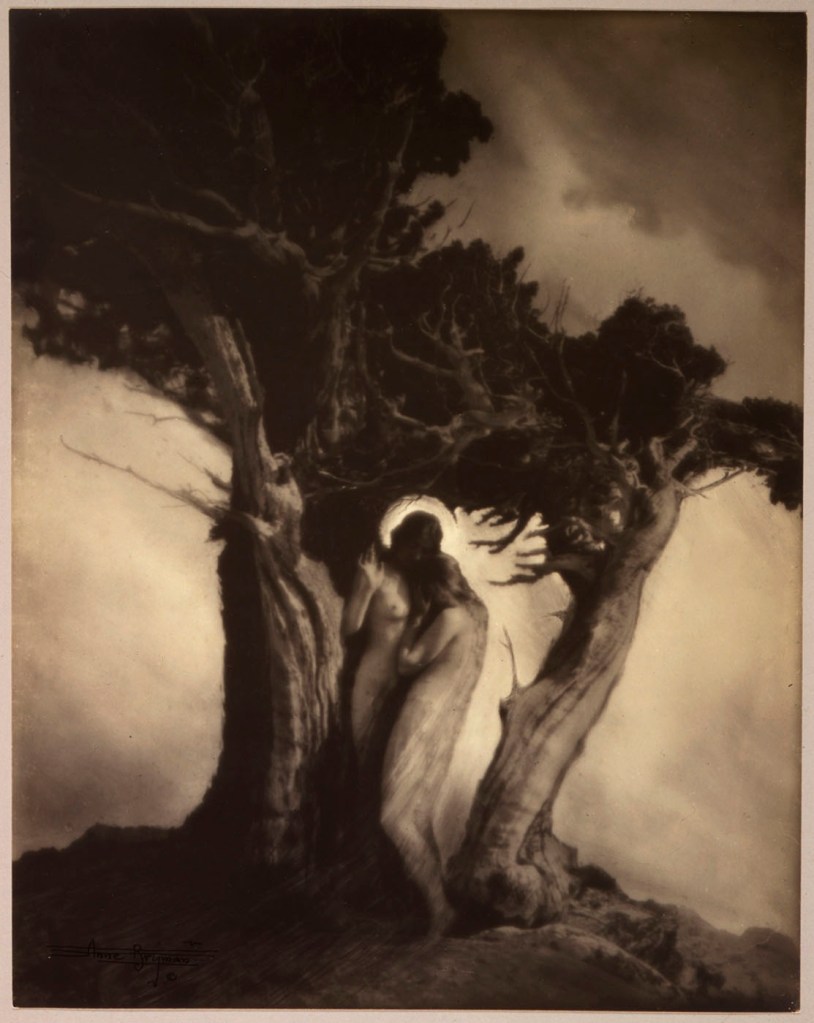

Anne Brigman: The Feminine Mystic of Photo-Secession

Anne Brigman was known for her evocative and mystical imagery. She often placed herself within her compositions, challenging traditional gender roles and expectations. Her connection to the Photo-Secession movement was cemented through her association with Alfred Stieglitz, who published her work in Camera Work and admired her innovative spirit.

Brigman’s 1911 photograph The Pine Sprite exemplifies her distinctive style. The image features a nude female figure intertwined with the natural landscape, blending the human form seamlessly with the rugged environment. This work reflects Brigman’s themes of femininity, nature, and freedom, aligning with the Photo-Secessionist emphasis on personal expression and artistic experimentation. Brigman’s contributions highlighted the movement’s inclusive spirit, showcasing how female photographers could assert their voices and artistic visions in a male-dominated field.

Adelaide Ryder. “The Photo-Secession Movement: Pioneering Artistry in Early Photography,” on the UMFA website Nd [Online] Cited 22/10/2024

Anne Brigman (American, 1869-1950)

The Shadow on My Door (Self Portrait)

1921

Gelatin silver print on paper

Anne Brigman (American, 1869-1950)

The Pine Sprite

1911

Gelatin silver print on paper

Brigman was for a long time the only Californian member of the Photo-Secession. She was a free spirit and pagan whose woodsy nudes inspired by fantasy and folklore were frequently reproduced in Camera Work.

Laura Gilpin (American, 1891-1979)

Ghost Rock, Garden of the Gods, Colorado

1919

Palladium print on paper

An amateur photographer from Colorado Springs, Gilpin moved to New York to study with Clarence White in 1916. This photograph was one of Gilpin’s first successes after returning home in 1919, the beginning of her decades-long career as one of the most notable photographers of the West and Southwest.

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

In 1916 Gilpin enrolled at the Clarence H. White School of Photography in New York. Two years later, she returned to her native Colorado Springs and became one of the few women to pursue landscape photography.

This is her depiction of the Garden of the Gods, a scenic rock formation in Colorado Springs. It captures the stillness and otherworldly quality of the area. The photograph also reflects an emphasis on the evocation of mood rather than on descriptive detail.

Text from the National Gallery of Art Facebook page

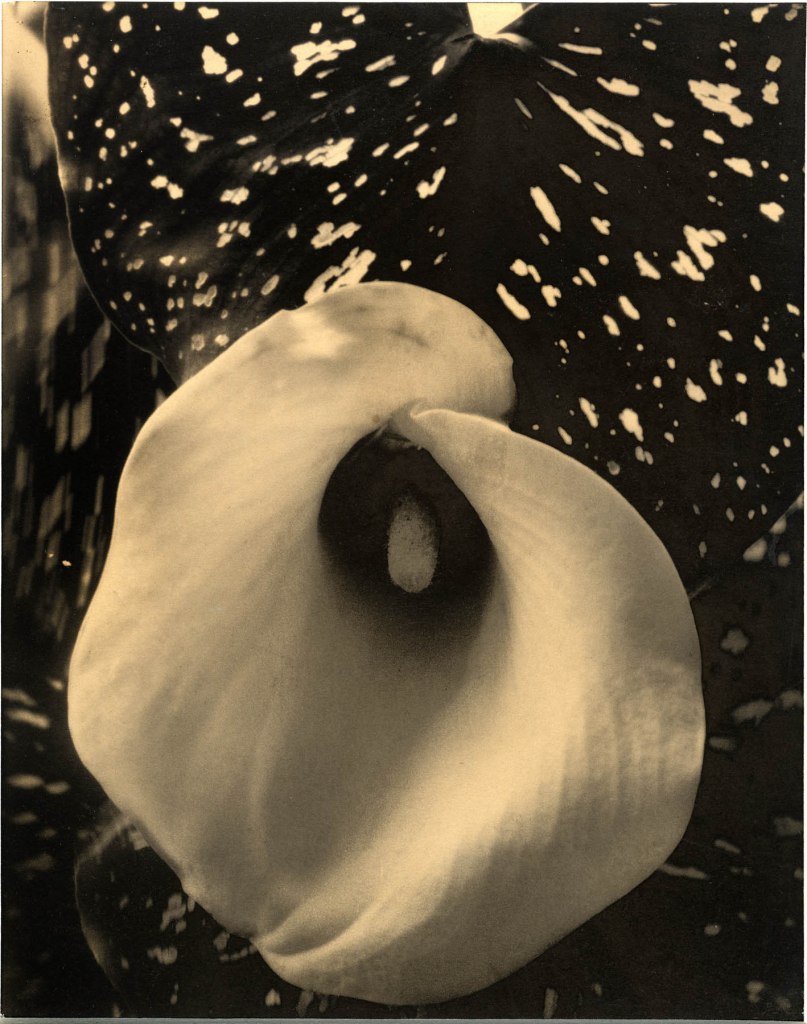

Edward Steichen

Edward J. Steichen: The Innovator

Edward J. Steichen, a close associate of Stieglitz, brought a unique perspective to the Photo-Secession movement. Steichen was not only a photographer but also a painter, which influenced his photographic style. He experimented with various techniques, including soft focus and manipulation of light, to create both ethereal and visually striking images.

An avid gardener, Steichen propagated and grew a bountiful garden at his French country house. This image of a calla lily is rendered with exquisite detail and tonal richness. Steichen’s botanical images showcase his ability to find harmony between nature and art. His meticulous composition and sensitivity to light transform a simple flower into a work of art, reflecting his painterly approach to photography. His botanical works contributed to the Photo-Secession movement by highlighting the artistic potential of natural forms.

Adelaide Ryder. “The Photo-Secession Movement: Pioneering Artistry in Early Photography,” on the UMFA website Nd [Online] Cited 22/10/2024

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

Lotus, Mount Kisco

1915

Gelatin silver print on paper

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

Calla Lily

c. 1921

Platinum print on paper

Steichen had previously photographed flowers in compositions that placed delicate floral arrangements next to women figured as ideals of feminine beauty. In contrast, here he presents the lotus and calla lily in sharp focus and as singular subjects without overt metaphorical meaning.

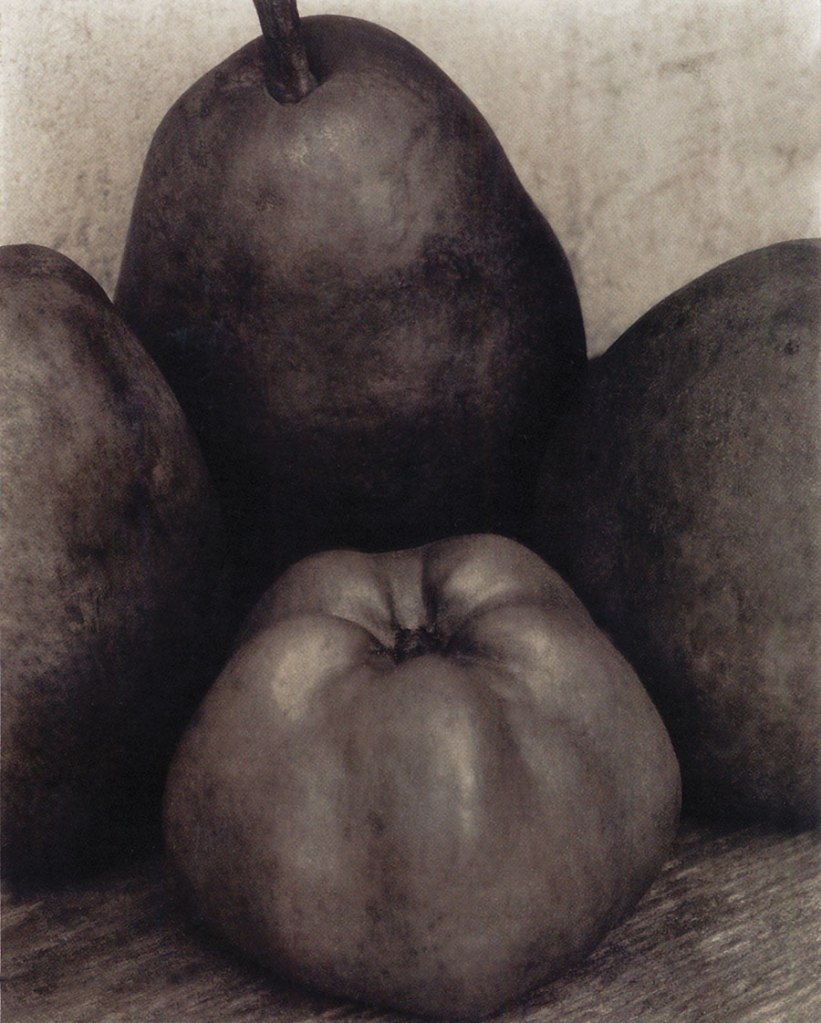

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

Three Pears and an Apple

1921

Gelatin silver print on paper

On making this picture Steichen wrote: “I was particularly interested in a method of representing volume, scale, and a sense of weight. In my small greenhouse I constructed a tent of opaque blankets. From a tiny opening, I directed light against one side of the covering blanket, and this light, reflected from the blanket, was all. I made a series of exposures that lasted more than two days and one night. As the nights were cool, everything, including the camera, contracted and the next day expanded. Instead of producing one meticulously sharp picture, the infinitesimal movement produced a succession of slightly different sharp images, which optically fused as one. Here for the first time in a photograph, I was able to sense volume as well as form.”

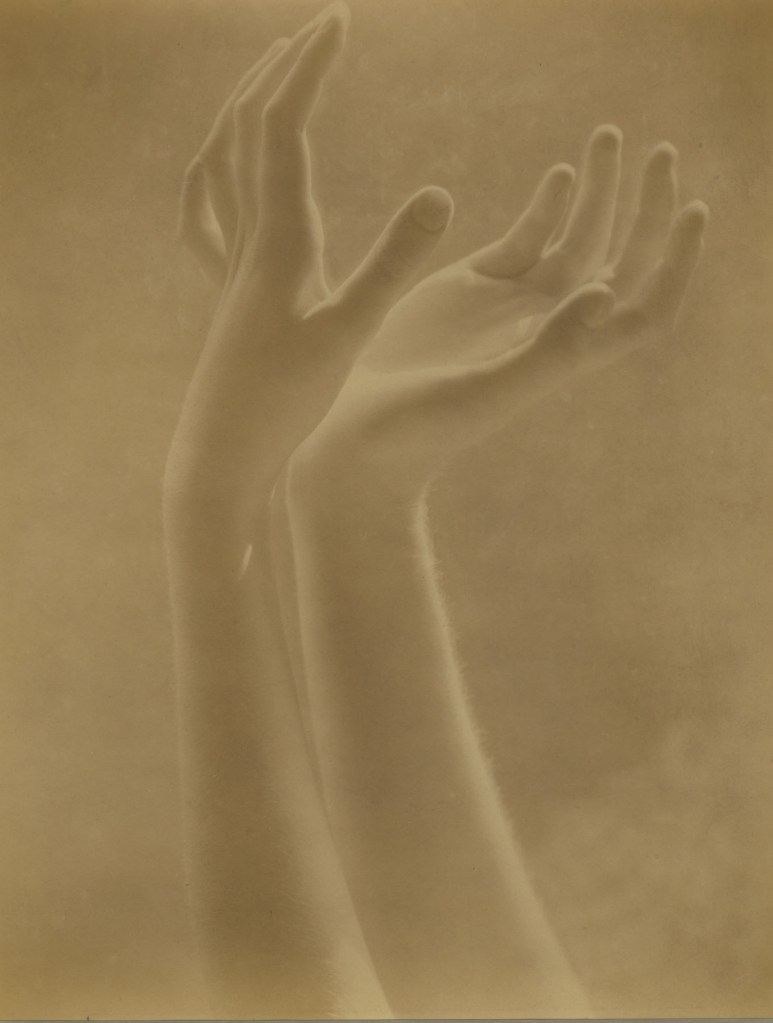

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

Blossom of White Fingers

c. 1923

Gold-toned gelatin silver print on paper

This study of the graceful hands of Steichen’s wife with ultra-soft focus and high-key lighting and printed on gold-toned gelatin paper is one of the rare instances of Steichen using Pictorialist methods after the end of the Photo-Secession.

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

Backbone and Ribs of a Sunflower

c. 1920

Gelatin silver print on paper

Steichen was a knowledgeable botanist and spent five decades photographing the life cycle of sunflowers. This is one of his earliest studies of the plant. He became fascinated with spirals in nature, writing, “I found some form of the spiral in most succulent plants and in certain flowers, particularly in the seed pods of the sunflower.”

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

Advertising Study for Coty Lipstick

1929

Gelatin silver print on paper

Steichen is credited as a founding figure of modern advertising and fashion photography. From 1923 to 1938, he served as chief photographer for the Condé Nast magazines Vogue and Vanity Fair. He had extensive experience in graphic design and advertising from his youth and earlier career. He had designed posters as a young man for a lithographic printer in Milwaukee. As Alfred Stieglitz’s associate on Camera Work from 1903 to 1917, Steichen produced the logo, typeface, and page layouts.

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

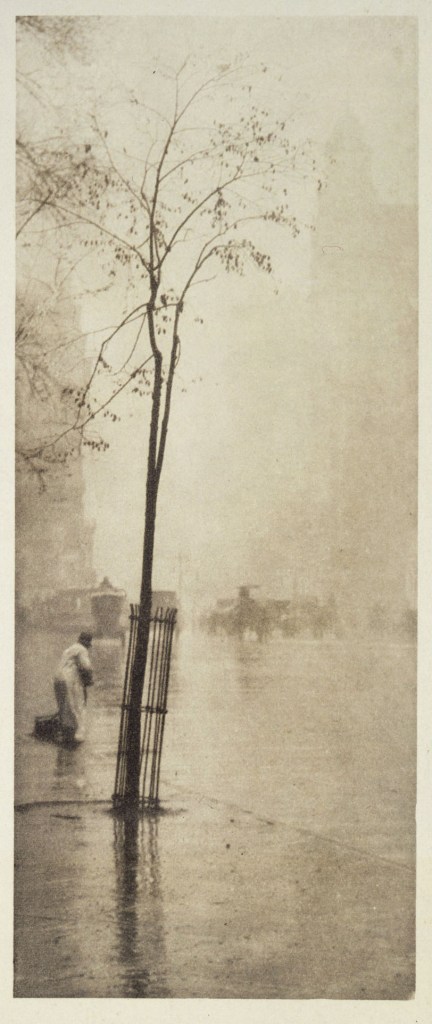

Works by Strand

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976)

Central Park

1915-1916

Platinum print on paper

Urban life preoccupied Strand and in the 1920s would become a central subject of Modernist photographers around the world. From a Central Park overpass Strand identified this interesting composition with the bright, sinuous path dividing the picture plane. The decisive moment to snap the shutter occurred with the appearance of the two advancing figures and their angular shadows.

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976)

Speckled Toadstool, Georgetown, Maine

1927

Waxed platinum print on paper

Strand continued to use platinum printing long after most other photographers adopted gelatin silver papers, which were more efficient and versatile and had a glossier surface. His prints in platinum are highly regarded for capturing minute detail and a wide range of tonal values.

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976)

Cobweb in the Rain, Georgetown, Maine

1928

Gelatin silver print on paper

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Works of Straight photography

Charles Sheeler (American, 1883-1965)

Side of White Barn, Bucks County

1917

Gelatin silver print on paper

A painter and photographer, Sheeler became a close friend of Alfred Stieglitz as the Photo-Secession dissolved. This photographic study of line, shape, and tone recalls the hard-edged style of Sheeler’s paintings. Only the chickens appearing at the bottom edge give a sense of scale to the barn.

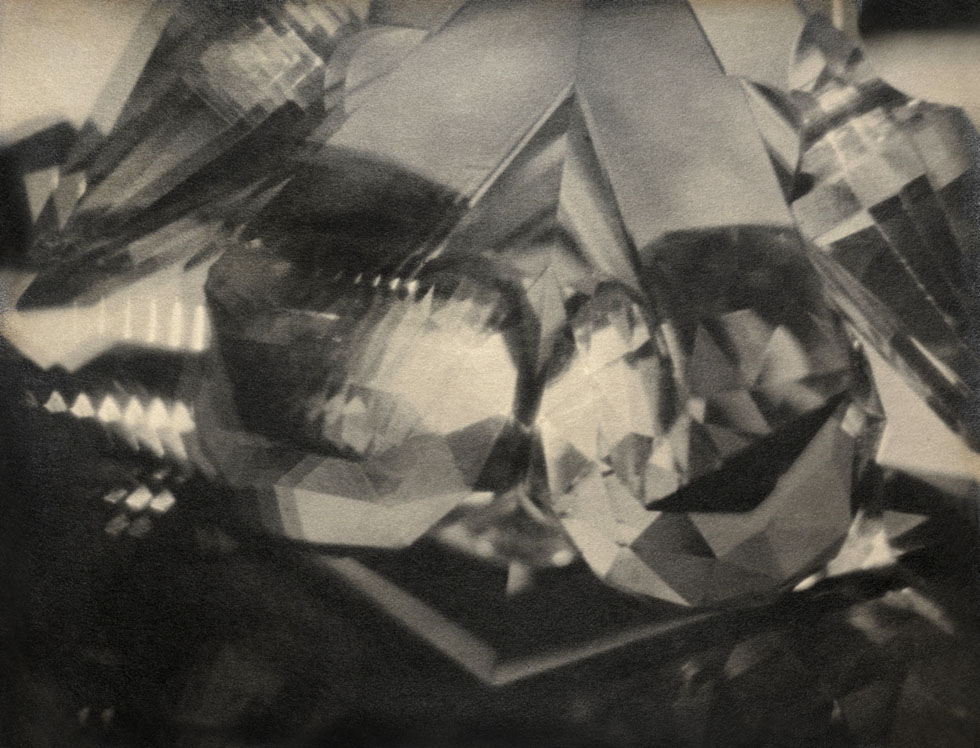

Alvin Langdon Coburn: The Avant-Garde Creator

Alvin Langdon Coburn pushed the boundaries of photography with his innovative Vortographs, created in 1916-1917. These images are considered some of the first abstract photographs, born from Coburn’s desire to create art that combined the physical with the spiritual. By placing a vortoscope, a triangular arrangement of mirrors and prisms, over a camera’s lens, Coburn created complex images of kaleidoscopic and geometric patterns that simplify the photograph to the essential elements of light and form. This technique broke away from traditional photographic representation, emphasising form, structure, and abstraction. The Vortographs were influenced by the Vorticist movement, which celebrated dynamic and abstract art. Coburn’s pioneering work with these images marked a significant departure from Pictorialism, embracing modernist principles and demonstrating the artistic potential of photography beyond mere depiction. The Vortographs stand as a testament to Coburn’s visionary approach and contributions to the evolution of photographic art.

Adelaide Ryder. “The Photo-Secession Movement: Pioneering Artistry in Early Photography,” on the UMFA website Nd [Online] Cited 22/10/2024

Alvin Langdon Coburn (British American, 1882-1966)

Vortograph

1917

Gelatin silver print on paper

Coburn was one of the Photo-Secessionists who rejected Pictorialism. In his 1916 essay “The Future of Pictorial Photography,” he called for abstraction in photography, concluding, “it is my hope that photography may fall in line with all the other arts, and with her infinite possibilities, do things stranger and more fascinating than the most fantastic dreams.” Coburn created vortographs like this by placing a devise with three mirrors between his camera and subject. When he exhibited them to great fanfare in London in 1917, Ezra Pound proclaimed: “The Camera is freed from Reality!”

All from the Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Utah Museum of Fine Arts

University of Utah campus

Marcia and John Price Museum Building

410 Campus Center Drive

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 10am – 5pm

Closed Mondays

![Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976) 'New York [Wall Street]' Negative 1915; print 1916 Photogravure Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976) 'New York [Wall Street]' Negative 1915; print 1916 Photogravure](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/strand-wall-street-a.jpg)

![Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976) 'New York [Wall Street]' Negative 1915; print 1916 Photogravure Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976) 'New York [Wall Street]' Negative 1915; print 1916 Photogravure](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/strand-wall-street-b.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.