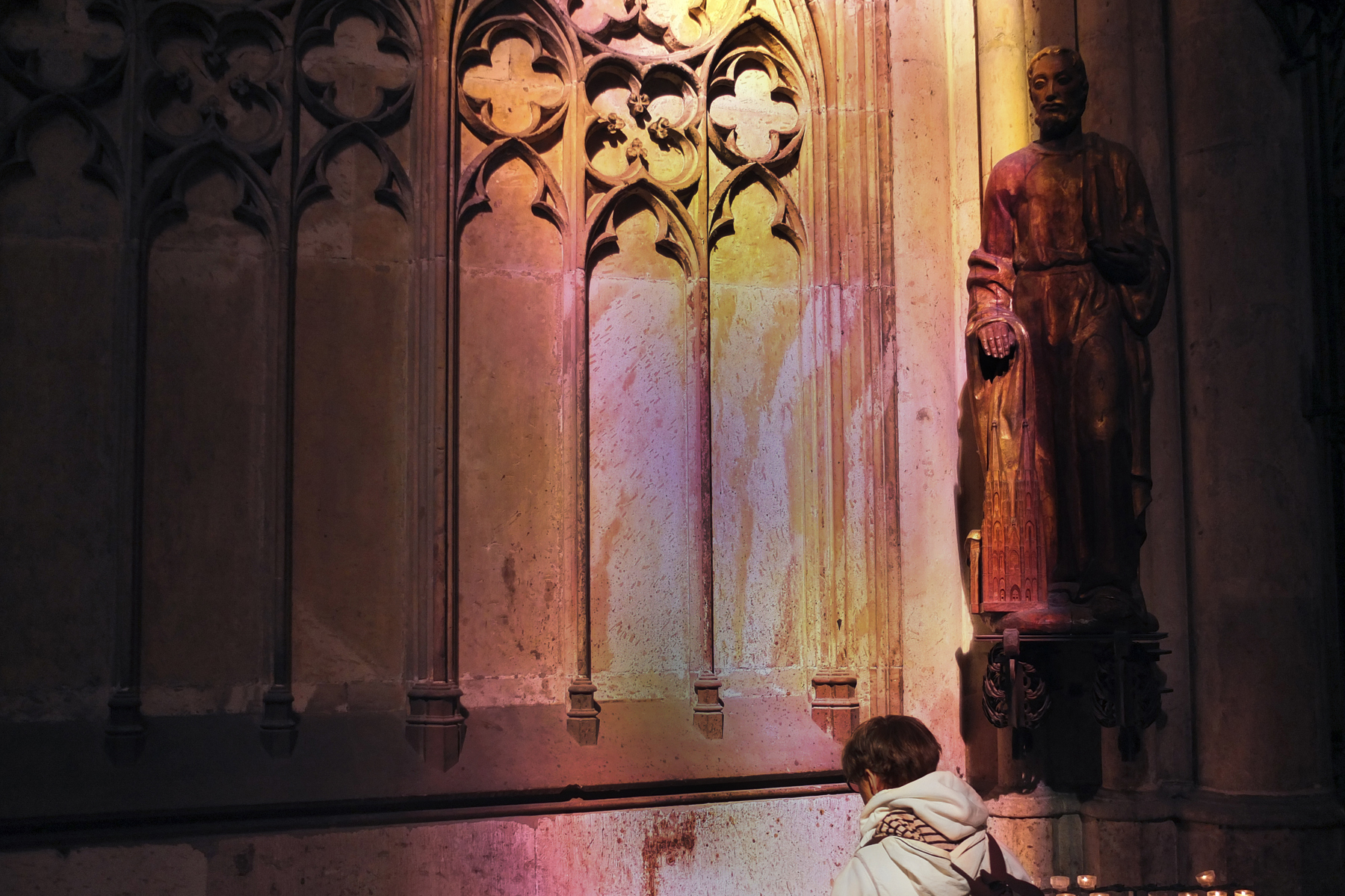

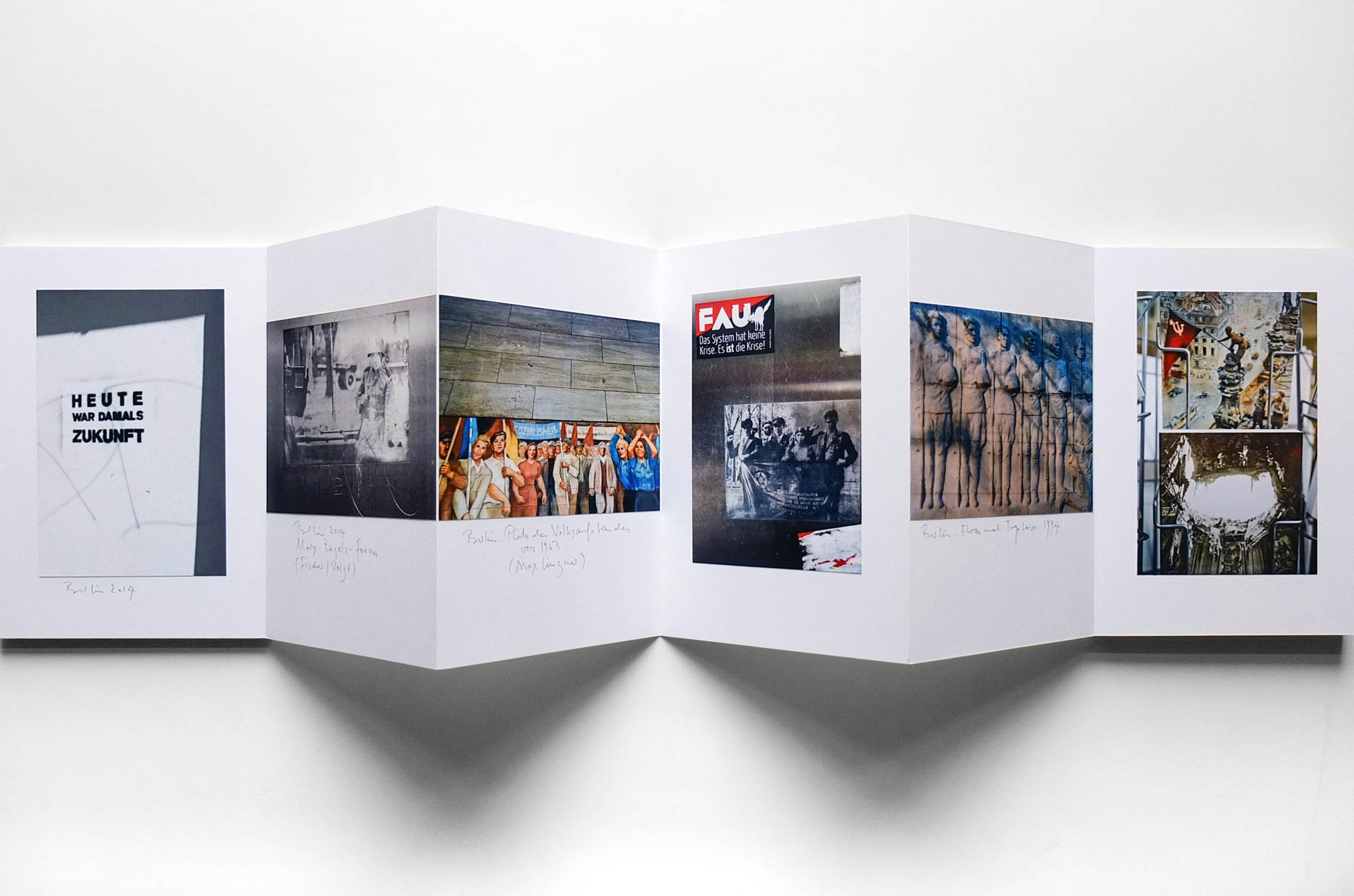

Exhibition dates: 14th March – 15 May, 2024

Curator: Stacey Lambrow

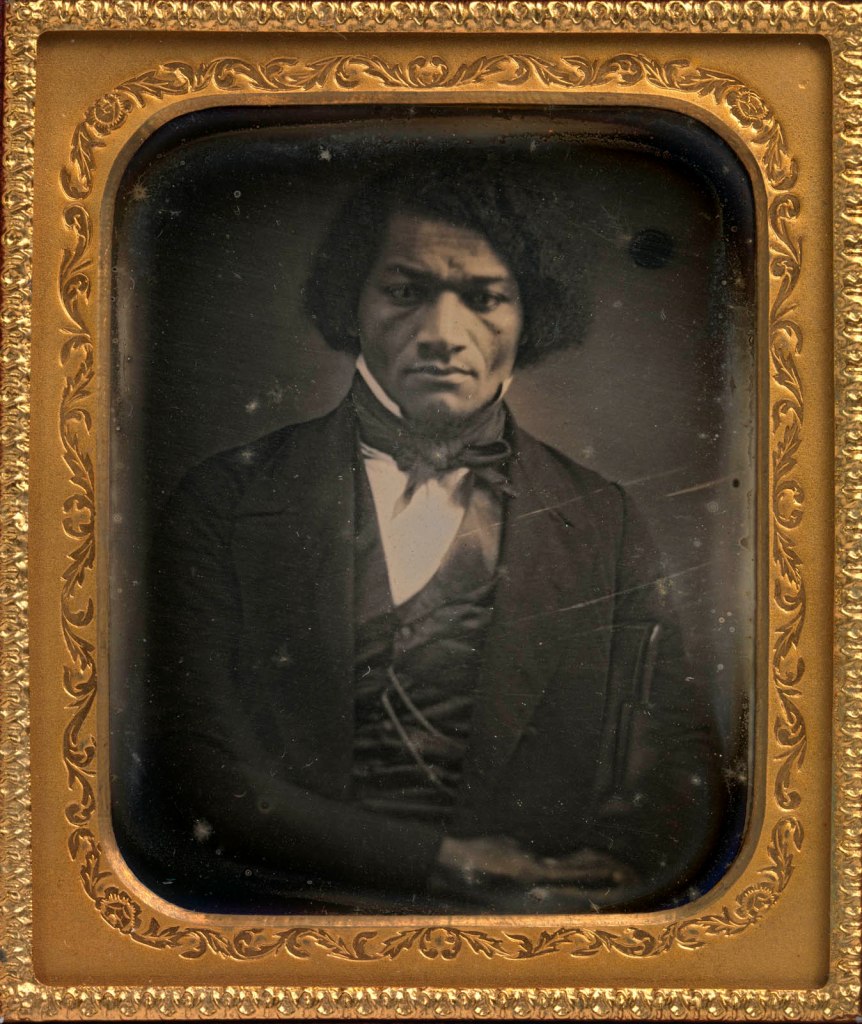

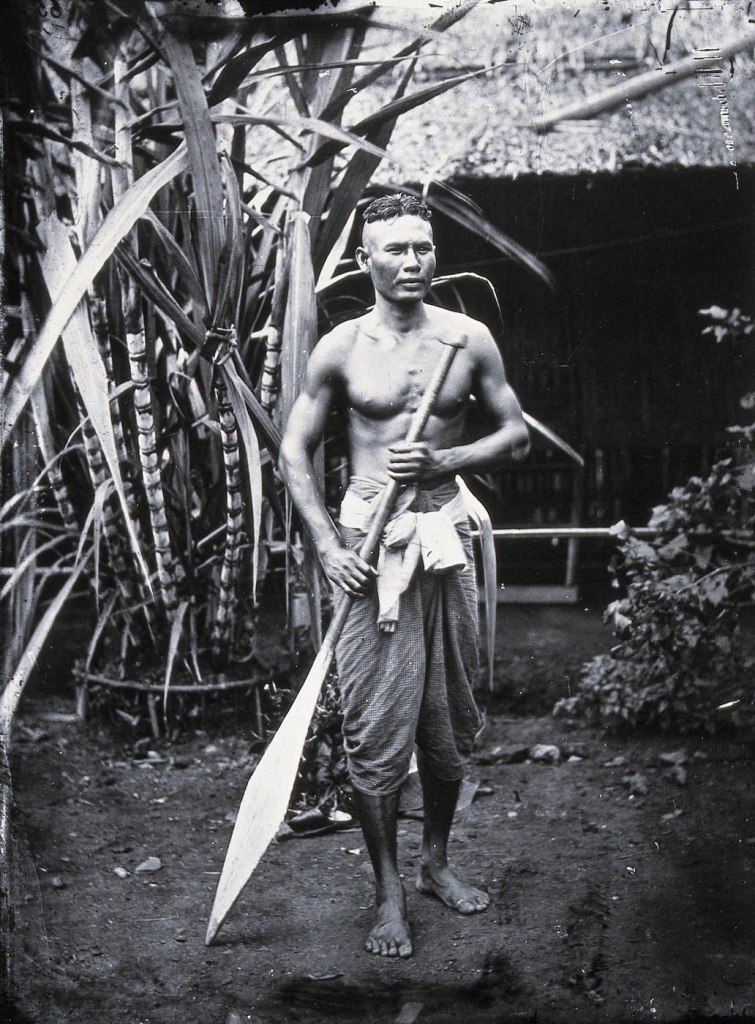

John Thomson (Scottish, 1837-1921)

Manchu Ladies

c. 1868

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

This posting is personal.

After I took the portrait below of my dear friend and fellow photographer Joyce Evans OAM (Australian, 1929-2019) at Jacques Raymond’s restaurant on the occasion of my birthday – the long exposure drawing a dragon-like creature from the flames – I posted the photograph to Facebook with a comment about Joyce being a “dragon lady” …. meaning, in my mind and foregrounded by Chinese culture, that she was a powerful, strong, loyal and intelligent women. Which she most definitely was.

I was then roundly abused by someone in a vituperative comment about calling Joyce a “dragon lady” when the person obviously had no idea of the mythological and cultural importance of the dragon to Chinese society, to which I was alluding.

Thus, it is with great joy that I post about this exhibition, a presentation that challenges “the negative and shallow stereotype of the “dragon lady.” The term remains a pervasive stereotype, often used against women who are unapologetically driven or have agency and power. It is particularly pernicious as a Western stereotype of East Asian women.” (Press release)

And thought, idea, photograph and in this case exhibition that challenges the stereotype and promotes difference and acceptance of that difference … can only make the world a better, more understanding place.

All power to strong, compassionate human beings everywhere.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Joyce Evans OAM (Australian, 1929-2019) at Jacques Raymond restaurant

2016

iPhone photograph

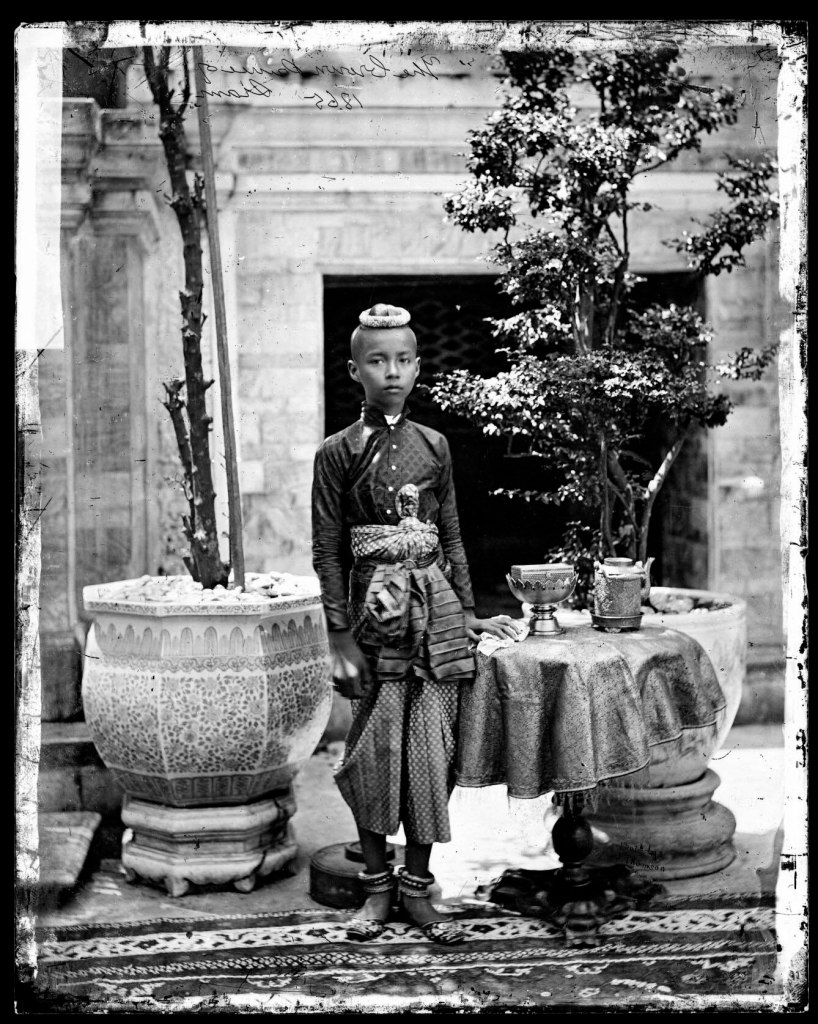

John Thomson (Scottish, 1837-1921)

Portrait of a Girl

1860s

Hand-coloured albumen silver print

Carte de visite

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Women in China can achieve the highest level of education today. At the end of the Qing dynasty this was not true. In Illustrations of China and Its People, the photographer John Thomson discusses the education of Chinese girls in the 1870s. He explains that girls are strictly secluded and that “Chinese history offers few examples of women who have been distinguished for their literary attainments.” He states that in “higher orders of society ladies here and there receive an education which enables them to form some slight acquaintance with the literature of their country, and to conduct and express themselves according to the strict and formal rules of etiquette which pertain to their position as daughters, or wives of men of learning and cultivation.”

Women’s education saw some reform during the final years of the Qing dynasty. Empress Dowager Cixi endorsed private women’s schools and sought public support for women’s education. The government acknowledged that educating women was necessary for developing strong mothers. Still, the Qing government continued to defend norms of gender separation and strict restrictions on women.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Unidentified Photographer in China

Portrait of a Woman Carrying a Child

1860s

Hand coloured albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Many Chinese photography studios created portraits of women carrying children on their backs. These popular portraits depict the tender bonds between the woman and the child, typically a boy.

Creating such photographs was both a technical and an interpersonal challenge. Because cameras were not yet widespread in the 1860s and 1870s, most women did not feel comfortable posing for a photographer. Skilled early photographers instilled trust allowing their subjects to feel at ease. It is likely that women were in the studio assisting female clients.

The wet plate collodion process mandated that a baby remain still for several seconds as a negative was exposed, lest the child appear blurred. Very young children routinely appear blurred in nineteenth-century photographs. The babies’ bodies were restrained by traditional Chinese baby carriers but their heads were free to move. The gaze of the child’s eyes in this portrait suggest a studio assistant, or relative, may be entertaining the children at the side of the photographer. This child is evidently content and connected with the women both physically and emotionally.

Women in China had long carried their babies on their backs, particularly in southern provinces. When an infant turned one month old, they were allowed to leave the home with their mother for the first time. At that time the maternal grandmother traditionally presented the baby with a baby carrier. During the late Qing dynasty, mothers, grandmothers, female siblings and amahs working in wealthy families would use these traditional carriers.

A baby carrier was a personal gift made of a square of dyed cloth with strips of fabric extending from the corners to provide straps. Baby carriers were often embellished with embroidered silk.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Pun Lun Studio (active circa 1864-1907)

Portrait of Woman and Child

1870s

Hand coloured albumen silver print

The Pun Lun Studio 瑱纶影相 was located at various addresses in Queen’s Road in Hong Kong. It was a successful portrait studio and opened branches in Fuzhou, Saigon and Singapore. Active c. 1864 – c. 1907.

Painting a Photograph

Tinted or hand-coloured photography was enormously popular among the prosperous individuals throughout the world. Portraits and genre studies served as status symbols for rising members of the professional and merchant classes…

Most nineteenth-century photographs of China are monochrome albumen silver prints made from collodion glass plate negatives. In the developing process, skilled photographers like the Pun Lun Studio were able to create gradation and richness of tone with great transparency and detail in shadows. The colour of the prints varied from red-violet to deep brown. Well-produced albumen silver prints were sumptuous, but coloured photographs commanded even higher prices.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection website

William Saunders (British lived China, 1832-1892)

Weaving

1860s

Hand-coloured albumen silver print

No. 6 in Sketches of Chinese Life and Character series

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

The Qing rulers adopted Confucianism from the Han Chinese culture of the conquered Ming dynasty.

In accordance with the Confucian ideal of gender labor division – “Men till, women weave.”

In this photograph Saunders presents a woman weaving on a loom. The woman is a model who appears in other roles in William Saunders photographic portfolio Sketches of Chinese Life and Character. Saunders’s depiction of the occupational roles of Chinese women follows a tradition established by painters in port cities. In this convincing pose the weaver appears to be engaged with the loom rather than the photographer. Saunders made this photograph outdoors at his studio but textiles were produced at a woman’s home. Women were secluded at home to ensure that their roles in their families was secure. Due to the nature of at-home work, women generated market income without having to reduce their investment in their families.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

William Saunders (British lived China, 1832-1892)

A Young Lady from Canton

1860s-1870s

Hand-tinted albumen silver print

No. 25 in Sketches of Chinese Life and Character series

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Women from Guangzhou were acclaimed for their natural beauty and often appear in early photographs. The woman in this portrait, tinged with uncertainty, wears a blue and red headscarf, an attire characteristic of women from a population living and working on boats in Guangzhou.

Many people in Guangzhou and other cities in China lived and worked on boats until the 1950s. Their boats were often anchored in lines along the rivers or coasts, with a large part of the clusters being stationary, forming a unique community and island-like space on the water, close to, yet separate from, the land.

Although traditional accounts from terrestrial Chinese and Westerns present the population of women living on boats as being engaged in prostitution, this was only true of a small minority and was no more common than among the terrestrial Chinese population. Women from the boat communities were not as hidden as other women in China. In addition to being known for their beauty, these women were described as skilful and hard-working boat drivers.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

William Saunders (1832-1892) was born in Woolwich, London and travelled to China as an engineer in 1860. He returned to Britain, studied photography, and then went back to China with photographic equipment. He photographed in Tientsin (Tianjin) in 1861 and then opened a studio in Shanghai in 1862, one of the city’s first. Saunders was a highly successful commercial photographer, specialising in portraiture, but also photographing everyday life, events, architectural, topographical and genre scenes. In 1871, he published his Portfolio of Sketches of Chinese Life and Character. William Saunders retired in 1888 and is now recognised as one of the most important photographers in nineteenth-century China.

Source: Terry Bennett. “History of Photography in China – Western Photographers – 1861-1879”, Quaritch 2010, pp. 83-106.

Text from the Historical Photographs of China website

Born in Britain in 1832, Saunders moved to China in the 1850s and opened a photography studio in Shanghai in 1862. One of the first photographers in the city, Saunders focused primarily on portraiture but also photographed street life, local customs, current events, scenic views, and even executions. His photographs, intended for tourists and Westerners, were often based on compositions of earlier gouaches made for export. He was one of the main commercial photographers in China in the nineteenth-century. A series of fifty prints – Portfolio of Sketches of Chinese Life and Character – was published in 1871. This portfolio, in addition to his photographic contributions to Illustrated London News and other publications, disseminated information about life in China to Westerners. Saunders died in 1892.

Text from the International Center of Photography website

William Saunders (British lived China, 1832-1892)

Shanghai Woman and Girl

1860s-1870s

Hand-tinted albumen silver print

No. 13 in Sketches of Chinese Life and Character series

The girl in this portrait rests her hand on the hip of the young woman to balance herself as she stands before the camera on her tiny bound feet. The young woman seems to protect the girl as she holds her open parasol, an accoutrement of the nobility in ancient China, as a shield. The young woman and girl in this studio portrait are said to be from Keangsoo (Jiangsu) province, a region around Shanghai. Their gazes cross, neither looks at the camera. The photographer sought to present the diverse regional styles that converged in the international Chinese city of Shanghai. The woman and the girl were used as models for the photographer William Saunder’s portfolio Sketches of Chinese Life and Character. The photographer’s portrayal of Chinese women from different regions in China played a role in consolidating and redefining long standing preconceptions of Chinese women.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios

A Mandarin’s Wife

1860s

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

In China, a tradition of ancestral portraiture preceded the invention of photography by many centuries. Commemorative portraits, commonly referred to as ancestor portraits, were central to the ritual of family worship. Photographic portraits echoed the stylistic attributes of the ancient commemorative images. In this portrait the woman is posed frontally, so that she faces the viewer directly. No part of her body is cropped out of the frame.

In both ancestor portraits and early photographs most women are anonymous. Even distinguished women were given little attention in most family genealogies. The histories of the majority of the named women appearing in early photographs come to us from through the careers or accomplishments of their fathers, husbands, or sons.

The woman in this portrait is dressed in such a way that immediately reveals her social rank. In full regalia she wears an elaborate headdress, a long necklace, a robe, and an intricate coat or fringed vest known as a xiapei. The coat displays a rank badge, reflecting her husband’s status within the government bureaucracy.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios

Portrait of Three Women from Amoy

1870s

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Women are usually not identified in early Chinese photographs, but their clothing, hairstyles, and other aspects of their appearances can indicate their origin and social status. The hairstyles and accoutrements of the women in this photograph by Lai Fong, including the oval painted fans they hold, are typical of women from Amoy (Xiamen). Early photographic portraits often feature props signifying the trades or social status of their subjects.

Traditionally, women of a higher social class preferred decorated circular fans, which were literati-associated objects. The fans in this photograph allude to the refined taste and intellect of the women. Fans can also represent romantic feelings and longing. The opulent clothing, jewellery, and coiffures in portraits such as this example were also used to emphasise idealised feminine beauty.

Like other Chinese and Western photography studios, Afong Studio sometimes produced genre photographs for sale to Chinese buyers and to foreign clients. The portrait may have originally been made by Lai Fong for the sitters or their associates. The photographer then generated additional profit from the negative by circulating the image around the world as a general depiction of feminine beauty in late nineteenth-century China.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Lai Fong [is] arguably the most ambitious and successful photographer of nineteenth-century China. He began practicing under the name Afong in Hong Kong in the 1860s, and over the next twenty years built a towering reputation on his illustrious clientele, his impressive product range, and a catalogue of views of China “larger, choicer, and more complete… than any other in the Empire,” according to his advertisements. His photographs of Chinese cities, monuments, people, and land – however shaped by the desires of his cosmopolitan clientele – stand as records of places that have changed often beyond recognition, and of his own artistry, exuberance, and entrepreneurial brilliance. Managed by his son and daughter-in-law after his death, his studio persisted into the 1940s, an instance of remarkable longevity in a famously difficult field.

“Despite the historical fame of Lai’s studio and the reach of his photographs, which exist today in collections worldwide, Lai remains little known outside of specialist circles,” said Kate Addleman-Frankel, the Gary and Ellen Davis Curator of Photography at the Johnson Museum. “His work is understudied and rarely exhibited, the result in part of a colonial view of photography’s history that has privileged Western travel photographers over indigenous practitioners.”

Text from the exhibition Lai Fong (ca. 1839-1890): Photographer of China at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Ithaca, NY, February – June 2020

Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios

Bridal Carriage

1870s

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Elaborately decorated bridal sedan chairs were a feature of Chinese weddings for centuries. Carried by four to eight porters, the chair brought the bride from her home to the groom’s family home. The journey that represented her transition from childhood to adulthood and from her family to that of her husband. Young children leading the procession symbolised the hope for children for the couple. On arrival at her new home, the bride might be helped down by a woman who had been lucky in marriage.

Lai Fong’s image has a candid aspect rare to early photographs which required a long exposure time. We see the carriage and the girls as they may have appeared on the street, without asking onlookers to pose or retreat from the frame. Curious about the photographer and the camera, several of them face the lens directly.

Chinese women in the late Qing dynasty often had no freedom regarding marriage. A woman married the man her parents chose whether she liked him or not. Often she had no way to know if she was compatible with her soon to be husband since she would not have met or set eyes on him until the wedding night. Within the family, a woman had to obey her father before marriage, her husband after marriage, and her son after the death of her husband.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

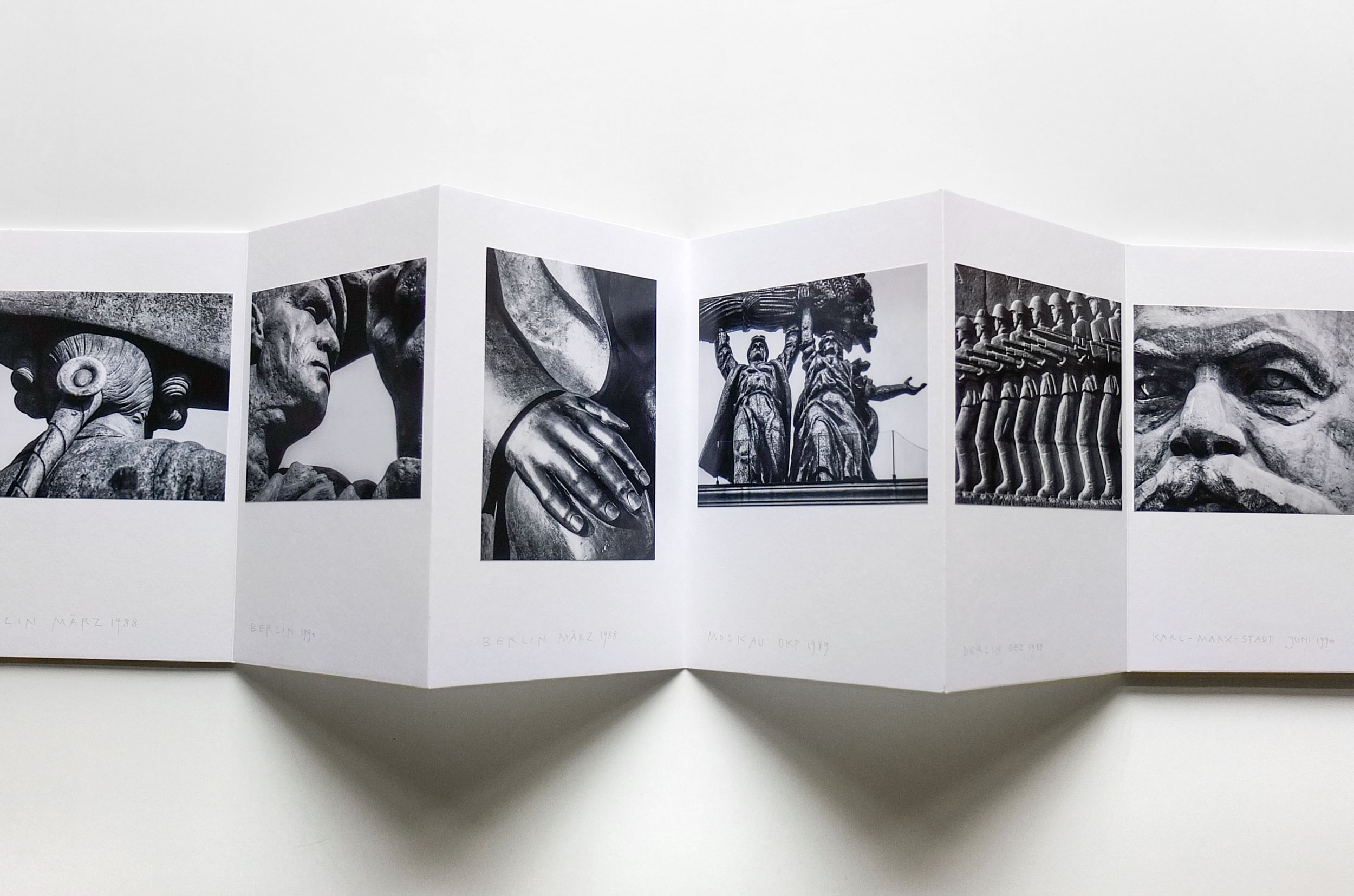

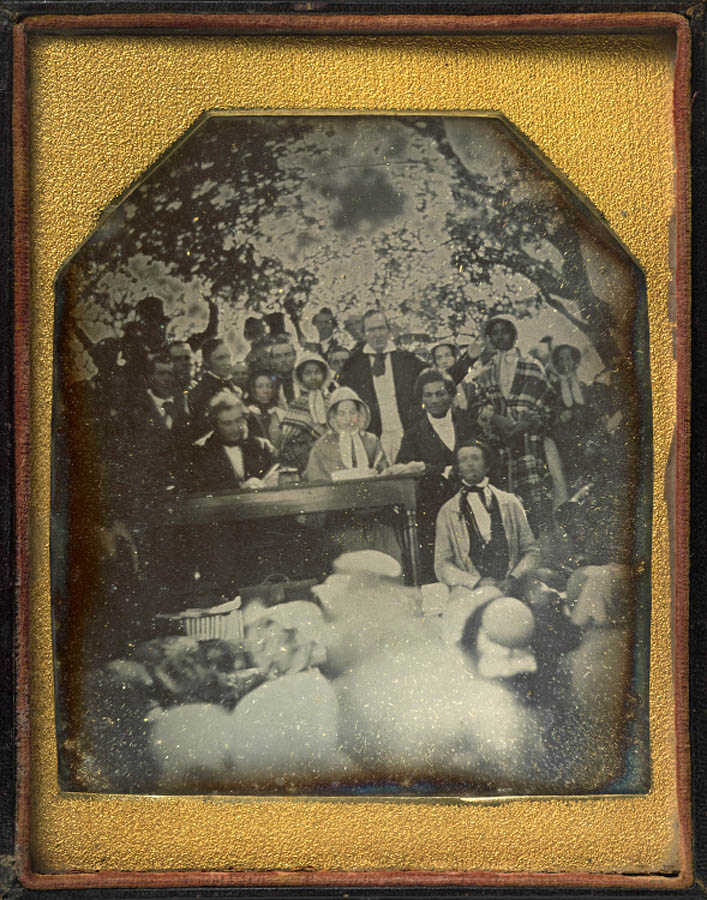

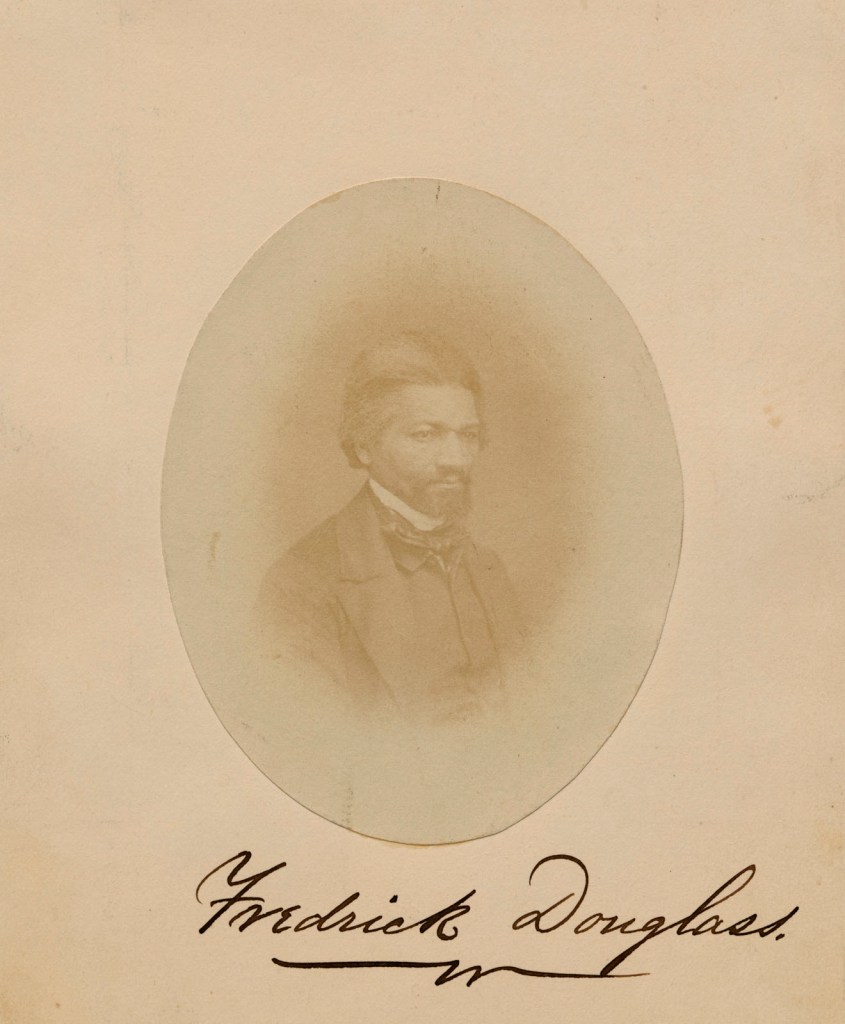

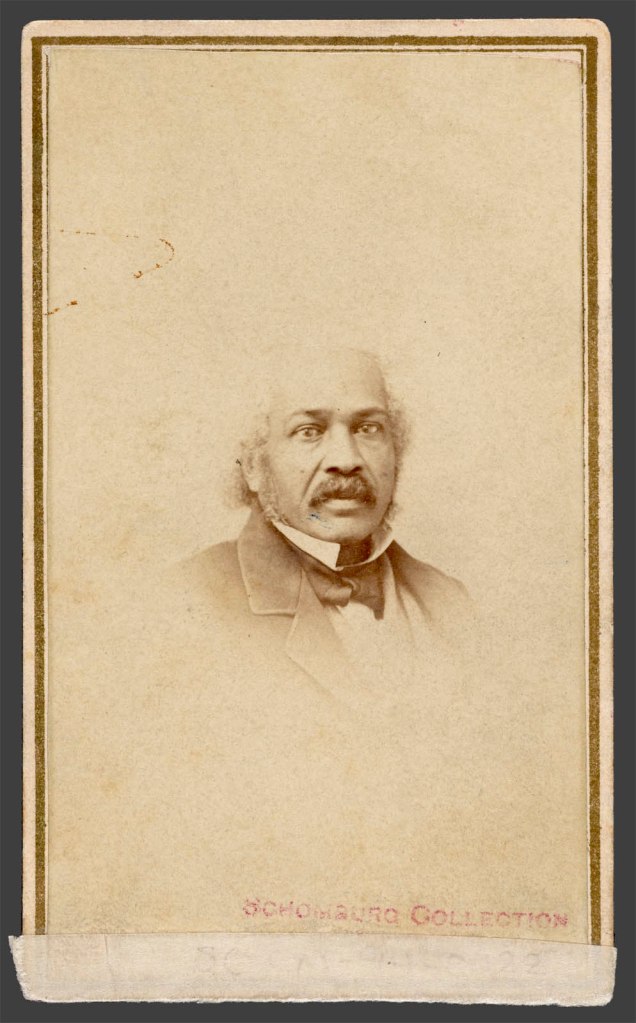

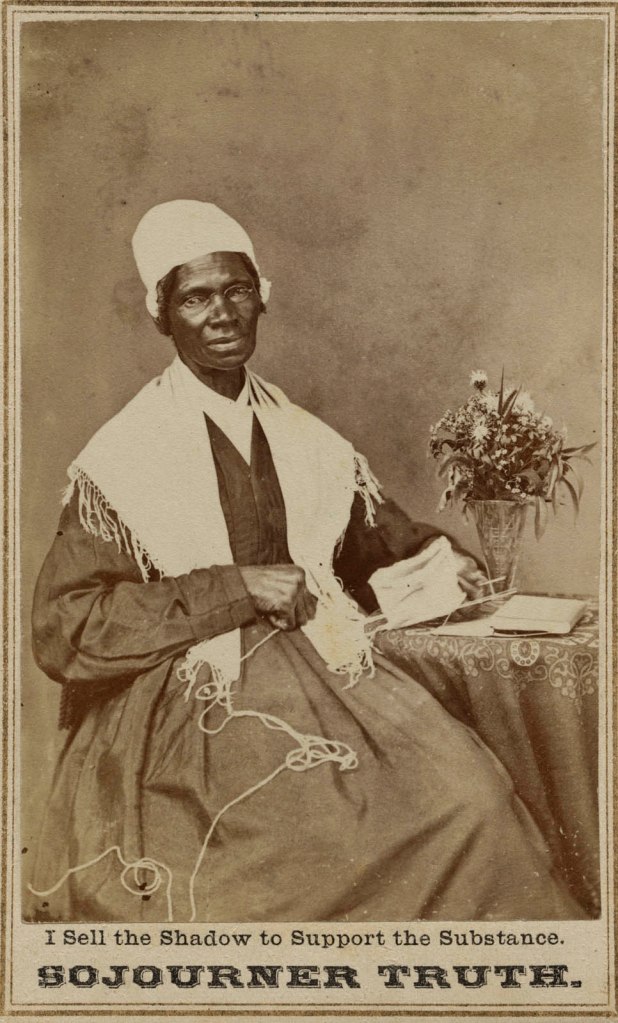

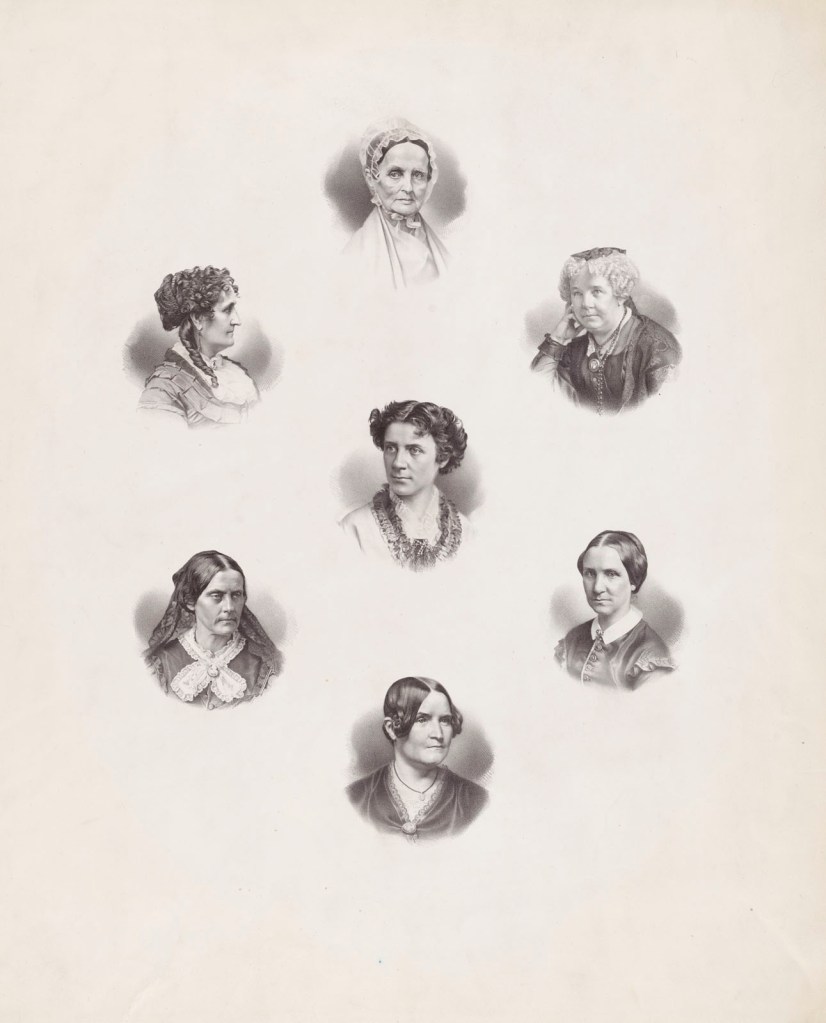

First Exhibition of the Earliest Photographs of Chinese Women

Rare early photographs of Chinese women from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection will be exhibited for the first time in New York as part of Asia Week New York. Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography curated by Stacey Lambrow runs from March 14th – May 15th 2024.

Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography celebrates the Year of the Dragon and the representation of women in the earliest photography of China. This is the first exhibition devoted to the depiction of Chinese women in early photography. The over 50 photographs selected from the Loewentheil Collection include the first photographic portraits of Chinese women, most made in the 1860s and 1870s. Many have never before been shown. The exhibition examines women’s place in society in the late Qing dynasty and their depiction in historical photography of China. It also presents work by the few known early female photographers of China.

Highlights include a rare photograph by the first known Chinese female photographer, Mae Linda Talbot, and works by Hedda Morrison, Isabella Bird, and Eva Sandberg Xiao. Masterworks include photographs by Chinese and international artists such as Sze Yuen Ming Studio, Pun Lun Studio, A Chan Studio, Lai Fong, John Thomson, and Thomas Child. The exhibition showcases the diversity of Chinese women and their experiences during the final decades of imperial China.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection website

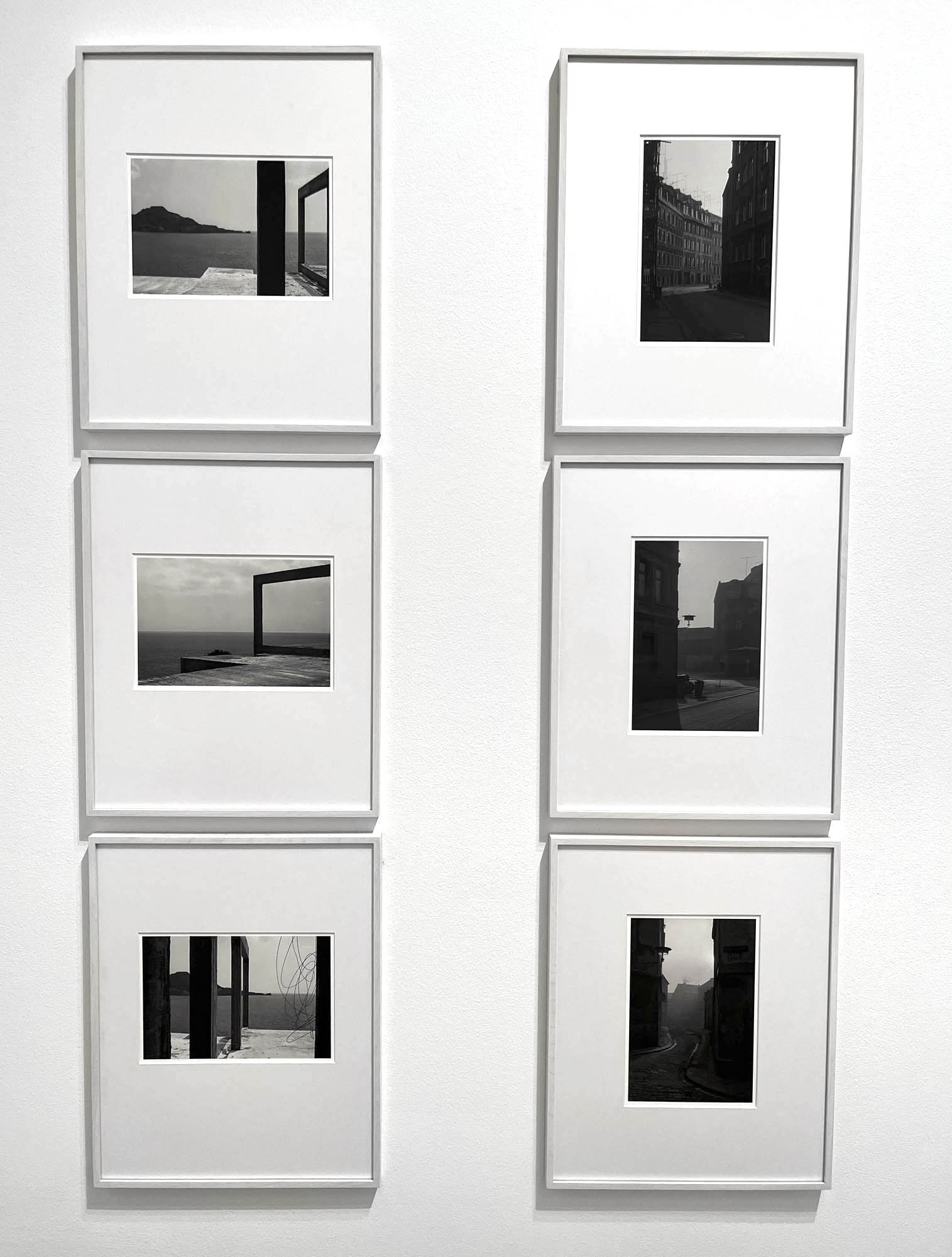

Installation view of the exhibition Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography at the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection showing at top right, Unidentified Photographer in China. Portrait of a Woman 1870s

Installation view of the exhibition Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography at the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Installation view of the exhibition Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography at the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection showing at left, Portrait of a Woman Playing a Dizi (1870s, below)

Unidentified Photographer in China

Portrait of a Woman Playing a Dizi

1870s

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

The woman in this portrait holds a dizi, a bamboo flute, as if she is playing it for the photographer. Courtesans playing the dizi and other Chinese instruments were a common subject of Chinese paintings before the theme appeared in the earliest photographs of Chinese women. In ancient China, courtesans were highly cultivated women who were rigorously trained in music, singing, dancing, and poetry. Courtesans were educated to be more than mere entertainers. Respected for their art and education in the classics, they were intellectual equals to aristocrats, scholars, and government official. Famous courtesans, such as Yang Yuhuan, were renowned for their beauty as well as their influence on politics and Chinese culture. They were hired to perform at elegant banquets for both male and female clients. They were also employed by the court.

Courtesan, such as Sai Jinhua, and others are some of the few women whose accomplishments are recognised by name in early Chinese history. Most women remained anonymous and were identified by their relationship to a father, husband, or son.

Courtesans often seem more at ease in front of the camera than other women. These women were accustomed to performing and being seen. They also recognised the value of photography for their reputations as entertainers.

During the late Qing dynasty, the status of some courtesans diminished as the concept of female performers changed. Subclass of courtesans developed. The artistic and intellectual skills of courtesans were not valued as highly as they once were and as a result some of these women became viewed as little more than objects of men’s sexual desire. They began to be regarded as prostitutes. It is evident from the props used in photography studios, such as instruments and books that artistic and literary talent continued to be associated with courtesans in the nineteenth century.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Installation view of the exhibition Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography at the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection showing at top left, Unidentified Photographer in China Portrait of a Woman (1870s, below)

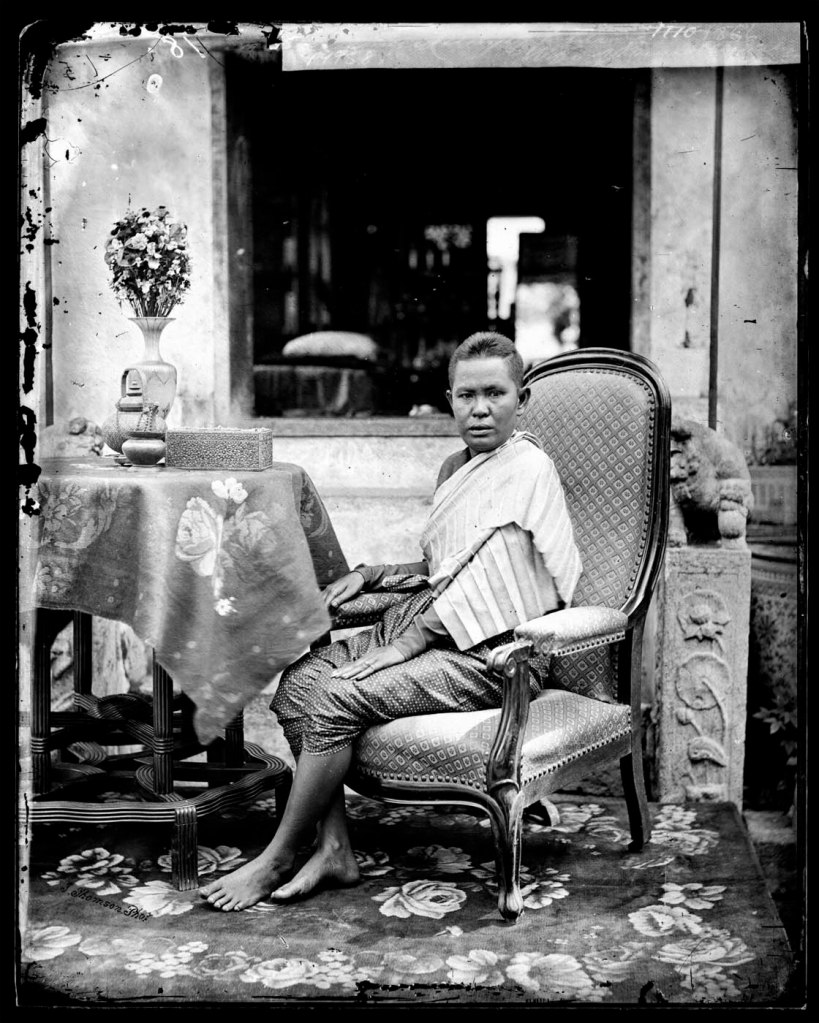

Unidentified Photographer in China

Portrait of a Woman

1870s

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Installation view of the exhibition Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography at the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Installation view of the exhibition Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography at the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection showing two photographs labelled below:

LEFT

Unidentified Photographer in China

Portrait of a Mother and Servants in Amoy

1860s

Albumen silver print

Carte de visite

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

An unidentified photographer achieved this powerful group portrait of three women and three children. It is inscribed on the verso “Women of Amoy (Xiamen).” The chaotic composition depicts a lavishly dressed seated woman gazing directly at the camera. She holds an open fan in one hand, a teacup in the other, and an elaborately dressed child is perched on her knee. Around her are servants including a young wet nurse cradling a feeding baby. The nurse stares ahead seemingly stunned as she bears her breast for the infant and the camera, a living emblem of the seated mother’s wealth. The image contradicts itself. It is a boastful public display of the privileges of the informal private life of a wealthy mother. The photograph was taken in the 1860s. The mother demonstrates the posture and dress of a woman of an elevated social position. It is unlikely that she was in a room interacting wit a male photographer, therefore the photograph was likely choreographed by a women assisting in the studio, perhaps a wife or daughter of the photographer. Social stipulations in late imperial China restricted women from contact with men outside their families. Domestic seclusion was considered a virtue. Women often requested privacy from men while being photographed.

Wall text from the exhibition

RIGHT

Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios

Portrait of a Chinese Caregiver with White Child

1880s

Cabinet card

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

This portrait depicts a white child from the West and an amah, a domestic servant, in Hong Kong. Some Chinese women were employed as live-in housemaids in wealthy households, combining the function of a maid and nanny. Often these women came from poor villages. They were seen as subordinates. Many of these women formed strong bonds with each other, amah sisterhood, and with the children under their care.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography at the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection showing various portraits of Chinese women on carte de visite

Installation view of the exhibition Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography at the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection showing two photographs labelled below:

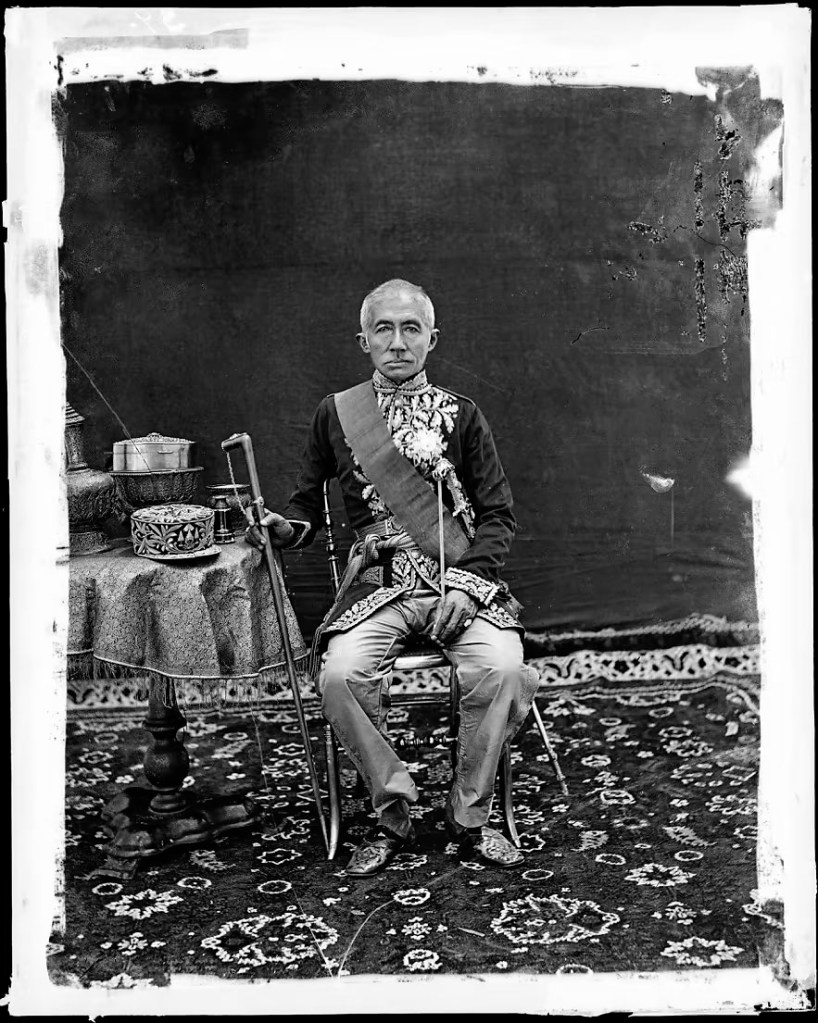

LEFT

Milligan Miller

The General’s Wife

1864

Albumen silver print

RIGHT

Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios

A Mandarin’s Wife

1860s

Albumen silver print

Rare early photographs of Chinese women from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection will be exhibited for the first time in New York as part of Asia Week New York. Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography curated by Stacey Lambrow runs from March 14th – May 15 2024.

Dragon Women: Early Chinese Photography celebrates the Year of the Dragon and the representation of women in the earliest photography of China. This is the first exhibition devoted to the depiction of Chinese women in early photography. The 50 photographs include the first photographic portraits of Chinese women, most made in the 1860s and 1870s. Many have never before been shown. The exhibition examines women’s place in society in the late Qing dynasty and their depiction in historical photography of China. It also presents work by the few known early female photographers of China.

Highlights include a rare photograph by the first known Chinese female photographer, Mae Linda Talbot, and works by Hedda Morrison, Isabella Bird, and Eva Sandberg Xiao. Masterworks abound including photographs by Chinese and international artists such as Sze Yuen Ming Studio, Pun Lun Studio, A Chan Studio, Lai Fong, John Thomson, and Thomas Child. The exhibition showcases the diversity of Chinese women and their experiences during the final decades of imperial China.

The dragon is an integral part of Chinese culture. The origin of dragons in Chinese mythology extends back to the earliest recorded dynasties, where male and female dragons were revered as powerful and benevolent creatures created by the gods to govern the world. Unlike the evil, fire-breathing European dragon, the Chinese dragon is an auspicious and multifaceted figure. It is both powerful and benevolent, fierce and elegant. The dragon also symbolises imperial power.

This exhibition held in the Year of the Dragon reclaims the feminine power of the dragon and honours all Chinese women. It includes iconic photographs of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) by her Court photographer Yu Xunling (c. 1880-1943). Cixi, one of the most powerful women in Chinese history, was referred to as “Dragon Lady.” Some caricatured her as a uniquely sinister, manipulative, and cold-blooded ruler. However, scholars agree that the Empress’s contribution to empowering and advancing opportunities for women is an important part of her legacy, thereby revising this one-dimensional view.

The early photographic portraits of women in Dragon Women challenge the negative and shallow stereotype of the “dragon lady.” The term remains a pervasive stereotype, often used against women who are unapologetically driven or have agency and power. It is particularly pernicious as a Western stereotype of East Asian women.

The exhibition portrays and honours women of various ages, classes, and social circumstances. The diversity of the “dragon women” in the photographs more authentically reflects the power and complexity of the dragon.

For the majority of women at the end of the Qing dynasty, being photographed was off-limits for social and financial reasons. Qing society perpetuated the conservative ideas of previous dynasties, and the majority of women were isolated in their homes. Some of the women in these images chose to be photographed, while others submitted to the photographer for other reasons. Some of the photographs were made as personal family photographs and others were produced for popular consumption to portray the women as “exotic.” Regardless, the camera immortalised their images and offer us a rare and complicated view into the lives of Chinese women during a period of modernisation in China.

Most late Qing dynasty photographs of Chinese women depict unnamed sitters and a great number of the portraits were created by photographers who at this time remain unidentified. As research into the history of photography of China advances, more of the names of the Chinese women appearing in nineteenth-century photographs will be discovered and more of China’s pioneering photographers will be identified. Certainly, more of the early photographers working in China will prove to be women.

The Loewentheil Photography of China Collection includes the largest selection of nineteenth-century photographs of Chinese women in the world. In photography’s most formative years Chinese women were involved in the art in a myriad of ways. Their presence exerted a profound influence on the development of the art of photography. Women worked alongside men in photography studios, sometimes as the wives and daughters of studio owners, or as printers, finishers, retouchers, colourists, camera operators, or studio managers. In addition, women participated as subjects of early photographs. Early photographs of Chinese women, rank among the greatest nineteenth-century photographs ever made.

About the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

The Loewentheil Photography of China Collection, based in New York, is the finest and largest holding of historical photographs of China in private hands. It contains many thousands of photographs spanning the earliest days of paper photography from the 1850s through the 1930s. The majority date to before 1900, including the largest selection of nineteenth-century photographs of Chinese women in the world.

Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios

Bound Foot Exposed [A Chinese Golden Lily Foot]

1870s

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Foot binding (simplified Chinese: 缠足; traditional Chinese: 纏足; pinyin: chánzú), or footbinding, was the Chinese custom of breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls to change their shape and size. Feet altered by foot binding were known as lotus feet and the shoes made for them were known as lotus shoes. In late imperial China, bound feet were considered a status symbol and a mark of feminine beauty. However, foot binding was a painful practice that limited the mobility of women and resulted in lifelong disabilities.

The prevalence and practice of foot binding varied over time and by region and social class. The practice may have originated among court dancers during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in 10th-century China and gradually became popular among the elite during the Song dynasty. Foot binding eventually spread to lower social classes by the Qing dynasty (1644-1912). Manchu emperors attempted to ban the practice in the 17th century but failed. In some areas, foot binding raised marriage prospects. It has been estimated that by the 19th century 40-50% of all Chinese women may have had bound feet, rising to almost 100% in upper-class Han Chinese women.

In the late 19th century, Christian missionaries and Chinese reformers challenged the practice but it was not until the early 20th century that the practice began to die out, following the efforts of anti-foot binding campaigns. Additionally, upper-class and urban women dropped the practice of foot binding sooner than poorer rural women. By 2007, only a small handful of elderly Chinese women whose feet had been bound were still alive. …

Feminist perspective

Foot binding is often seen by feminists as an oppressive practice against women who were victims of a sexist culture. It is also widely seen as a form of violence against women. Bound feet rendered women dependent on their families, particularly the men, as they became largely restricted to their homes. Thus, the practice ensured that women were much more reliant on their husbands. The early Chinese feminist Qiu Jin, who underwent the painful process of unbinding her own bound feet, attacked foot binding and other traditional practices. She argued that women, by retaining their small bound feet, made themselves subservient as it would mean women imprisoning themselves indoors. She believed that women should emancipate themselves from oppression, that girls can ensure their independence through education, and that they should develop new mental and physical qualities fitting for the new era. The ending of the practice is seen as a significant event in the process of female emancipation in China, and a major event in the history of Chinese feminism.

In the late 20th century, some feminists have pushed back against the prevailing Western critiques of foot binding, arguing that the presumption that foot binding was done solely for the sexual pleasure of men denies the agency and cultural influence of women.

Other interpretations

Some scholars such as Laurel Bossen and Hill Gates reject the notion that bound feet in China were considered more beautiful, or that it was a means of male control over women, a sign of class status, or a chance for women to marry well (in general, bound women did not improve their class position by marriage). Foot binding is believed to have spread from elite women to civilian women and there were large differences in each region. The body and labor of unmarried daughters belonged to their parents, thereby the boundaries between work and kinship for women were blurred. They argued that foot binding was an instrumental means to reserve women to handwork, and can be seen as a way by mothers to tie their daughters down, train them in handwork, and keep them close at hand. This argument has been challenged by Shepherd 2018, who shows there was no connection between handicraft industries and the proportion of women bound in Hebei.

Foot binding was common when women could do light industry, but where women were required to do heavy farm work they often did not bind their feet because it hindered physical work. These scholars argued that the coming of the mechanised industry at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, such as the introduction of industrial textile processes, resulted in a loss of light handwork for women, removing a reason to maintain the practice. Mechanisation resulted in women who worked at home facing a crisis. Coupled with changes in politics and people’s consciousness, the practice of foot binding disappeared in China forever after two generations. More specifically, the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing (after the first Opium War) opened five cities as treaty ports where foreigners could live and trade. This led to foreign citizens residing in the area, where many proselytised as Christian missionaries. These foreigners condemned many long-standing Chinese cultural practices like foot binding as “uncivilised” – marking the beginning of the end for the centuries-long practice.

Text from the Wikipedia website

John Thomson (Scottish, 1837-1921)

Older Woman Carrying Child

c. 1868

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios

Caregiver [Woman carrying child]

1870s

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

A Chan (Yazhen) Studio

Portrait of a Female Musician

1870s

Albumen silver print

11.5 x 6.5cm

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Guqin music expresses the soul of the Chinese nation.

An Early Photograph including a Guqin

This rare A Chan (Yazhen) Studio photograph is one of the earliest known photographs including a guqin or qin. The instrument, the most prestigious in China, was invented more than three thousand years ago. Guqin playing developed as an elite art form practiced by scholars and noblemen. It is one of the four classic Chinese arts along with painting, an ancient form of chess, and calligraphy. The guqin is famous for being the preferred instrument of literati and sages. A Chan (Yazhen) Studio’s 1870s photographic portrait depicts a woman with a guqin, an instrument critical to Chinese intellectual history.

A Female Musician

A Chan (Yazhen) Studio posed the elegant woman directly in front of the camera. Rather than looking down towards the musical instrument, the woman’s eyes engage the viewer as she holds her pose. In accordance with tradition an incense burner is positioned on the table in front of her. The Chinese photography studio, fully cognisant of the significance of the art form, has composed a timeless photograph of the ancient instrument and the beauty of its player.

The woman’s hand gestures suggest that she was a skilled practitioner of the instrument. Her hand positions are accurate, and her left hand is pressing the strings rather than plucking them. The constraints of early photography prevented the woman from playing the instrument while posing. Long exposure times required by the wet plate collodion process would cause motion to appear as a blur in the negative. It is very likely that the photographer instructed the guqin player to exaggerate her finger positions to emphasize her gestures and give the illusion that she was playing the instrument.

Imperial-era literature strongly suggests that guqin playing was a male dominated tradition, but paintings dating back to the Tang dynasty depict female players. The female guqin players in early paintings are identified as court ladies or ladies of refinement. Contemporary scholars believe that it is a mistaken stereotype to consider guqin playing a strictly male tradition. In order to understand the prevalence and role of female guqin players, scholars are working on closer studies of women in Ming and Qing Dynasty qin schools and societies. Today there are many more female than male qin players, and all people of all walks of life play the instrument.

The Guqin

The guqin is a seven stringed instrument endowed with metaphysical and cosmological significance. The instrument, beloved by sages including Confucius, is said to have the power to communicate the deepest human feelings. Writers dating back to the Han Dynasty claim that the guqin aids in cultivating character, understanding morality, and enhancing life and learning.

Each component of the guqin relates to cosmology and is identified by a zoomorphic or anthropomorphic name. The upper round board symbolises heaven. The flat bottom board represents earth. The strings are traditionally made of twisted silk and vary in thickness. Traditionally the guqin had five strings which symbolise the five elements: metal, wood, water, fire, and earth.

Guqin playing, is much more than an auditory experience, it has an olfactory component as well. The players customarily perfumed the air by burning incense. The incense burner in A Chan (Yazhen) Studio’s portrait is placed in its usual position in front of the musician.

It is traditionally said that twenty years of training are necessary to gain proficiency on the qin. Guqin players once had a repertoire of several thousand compositions. Presently, fewer than one hundred works are still performed. Today there are fewer than one thousand well-trained guqin players and no more than fifty surviving masters. The guqin and guqin music, recognised as inseparable from Chinese intellectual history, have been added to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The art form had been on the verge of extinction, but in recent times there has been a revival of guqin culture. Contemporary musicians are attracting the interest of young people in the ancient Chinese art form.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection website

A Chan (Yazhen) Studio

Portrait of a Female Musician

1870s

Albumen silver print

11.5 x 6.5cm

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Evening Cry of the Crow 乌夜啼

Performed by Mingmei Yip 叶明媚

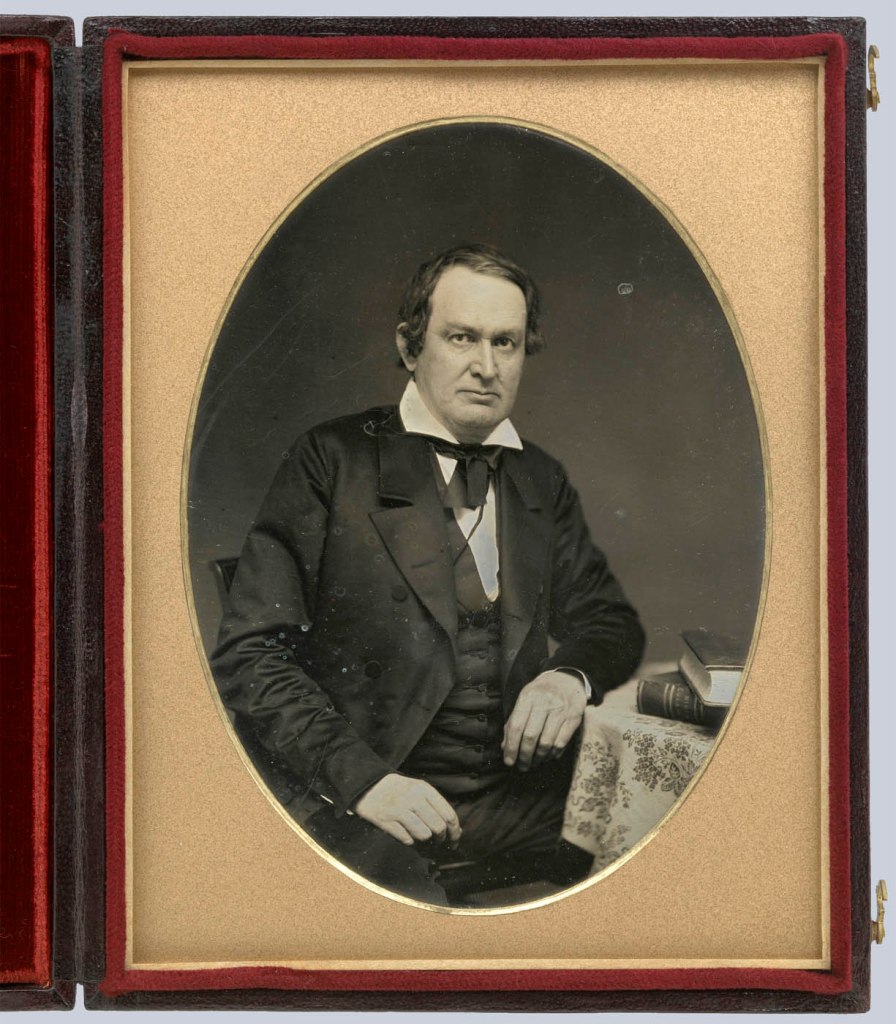

Isabelle Bird (English, 1831-1904)

Fuzhou Headdress

1896

Gelatin silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Isabella Bird (1831-1904) was a pioneering female travel photographer and writer from England. She travelled to several continents in defiance of societal conventions. Bird is famous for her books beautifully illustrated with her own photographs.

China is the first country Bird visited with the goal of creating a photographic record of a place. Her photographs are some of the most thoroughly documented records of nineteenth-century China. Bird’s photographs of China on the brink of modernisation are sensitive, comprehensive, and unparalleled. They reveal her admiration for the country, its people, and their culture. After first arriving in China in 1894, she returned frequently over three years.

Bird became the first woman inducted into the Royal Geographical Society in 1892 and she was elected to membership of the Royal Photographic Society in 1897. She died in Edinburgh in 1904, just short of her 73rd birthday. Her bags were packed for another journey to China.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Sanshichiro Yamamoto (Japanese, 1855-1943)

Women in Peking Cart

c. 1900

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Sanshichiro Yamamoto 山本讃七郎 (1855-1943) was a Japanese photographer, born in Okayama Prefecture. He had a photography studio in Shibahikage-cho (near present day Shimbashi Station) in Tokyo, Japan, from 1882 to about 1897. When news of the Boxer Uprising swept the world, he quickly went to Peking (Beijing) to photograph the historic activities of foreign troops in the capitol, including the Japanese. After photographing the aftermath in Peking (Beijing), he finally settled down in Tientsin (Tianjin) and opened his third photographic studio (Yamamoto Shōzō Kan or Yamamoto Syozo House), from where he sold photographs, souvenir photobooks and coloured post cards, taken in and around Beijing and North China. Yamamoto’s photographs were published in Views of the North China Affair, Picturesque Views of Peking and View and Custom of North China (1909).

Text from the Historical Photographs of China website

Yu Xunling (勋龄; c. 1880-1943)

Empress Dowager Cixi

c. 1903

Albumen silver print

24.1 x 17.8cm (9.5 x 7 in.)

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

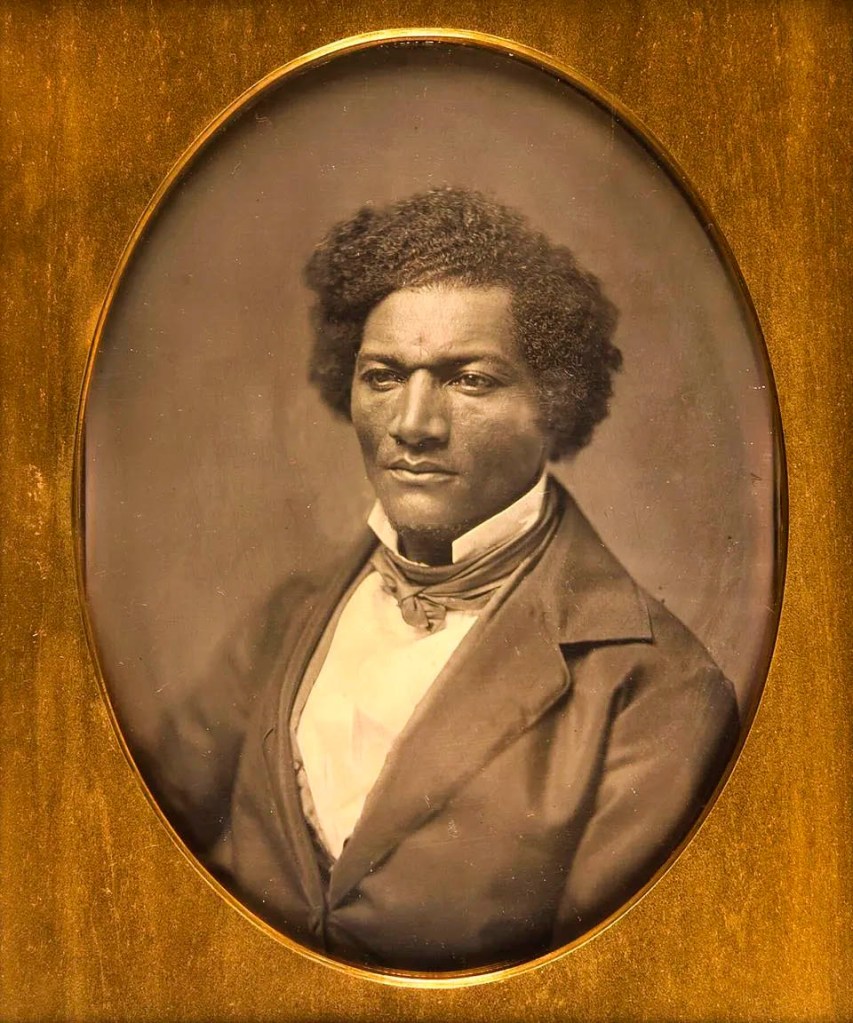

This exhibition held in the Year of the Dragon reclaims the feminine power of the dragon and honours all Chinese women. It includes iconic photographs of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) by her Court photographer Yu Xunling (c. 1880-1943). Cixi, one of the most powerful women in Chinese history, was referred to as “Dragon Lady.” Some caricatured her as a uniquely sinister, manipulative, and cold-blooded ruler [see text below]. However, scholars agree that the Empress’s contribution to empowering and advancing opportunities for women is an important part of her legacy, thereby revising this one-dimensional view.

Text from the press release from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

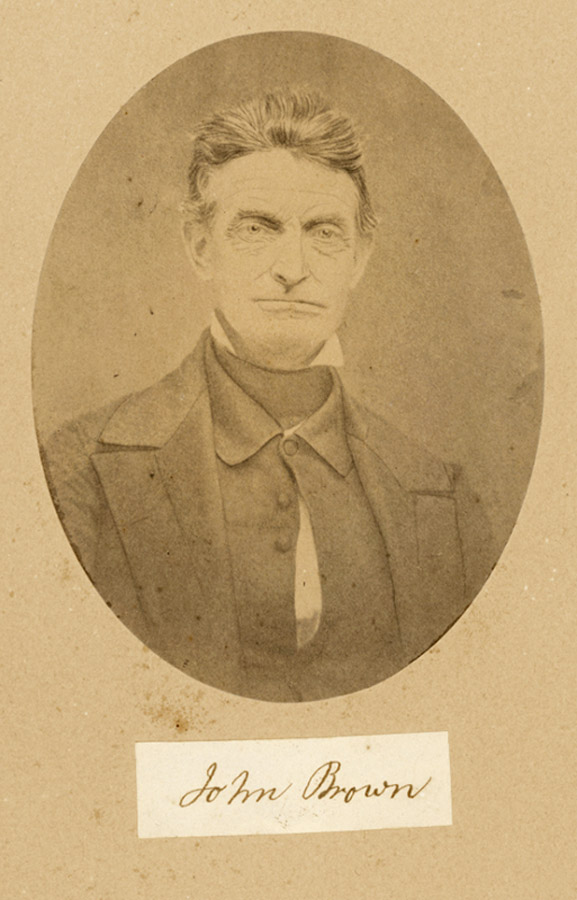

Cixi (慈禧太后), Empress Dowager of China, 1835-1908

This photograph was taken in the Hall of Happiness and Longevity (Leshou tang) in the Summer Palace, Beijing. Cixi sits at the center. Behind her is a banner that says “Long Live the Current Divine Mother Empress Dowager of the Great Qing Empire for Ten Thousand Years.” Her embroidered robe is covered with stylised longevity characters and chrysanthemums, a symbol for long life. The auspicious emblems signify the wish of longevity for herself and, by extension, for the Qing dynasty. …

Cixi is a contradictory figure in Chinese history. From the 1860s until her death in 1908, Cixi dominated the Qing court and policies. She was regent to two successive emperors. Powerful as she was, she did not have a good reputation abroad. During her reign, foreigners and some of Cixi’s countrymen considered the Qing court to be conservative, corrupt, and incompetent. Her reputation was worsened among westerners after the Yihetuan Movement of 1900 (also known as Boxer Rebellion), an anti-imperialist, anti-foreign, and anti-Christian uprising. Cixi supported the group and declared war on the foreign powers. In response, a foreign joint army was sent to Beijing and Cixi was forced to flee the capital. After she returned to Beijing in 1902, she changed course and initiated massive reforms. She also took advice from key reformers. These new policies included promoting railroads, founding modern schools, and sending students to study overseas. Cixi also attempted to improve her international image. For example, she would invite the wives of foreign diplomats to receptions at the palace…

The picture belongs to the only photographic series taken of Cixi. They were shot by a young aristocratic photographer named Xunling (c. 1880-1943) between 1903 and 1904. The photographs were meant to be used to restore Cixi’s public image. They were designed to convey imperial authority and aesthetic elegance. Some of the photographs were presented as diplomatic gifts, including one for US President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919).

National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution. “Xunling, The Empress Dowager Cixi with foreign envoys’ wives,” in Smarthistory, July 6, 2021 [Online] Cited 05/04/2024

Yu Xunling (勋龄; c. 1880-1943)

Empress Dowager Cixi

c. 1903

Albumen silver print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

The Loewentheil Collection includes iconic photographs of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) by her Court photographer Yu Xunling (c. 1880-1943). Xunling’s series of photographs of Cixi commissioned in 1903 and 1904 are the only known surviving photographs of the most important political figure of the late Qing dynasty.

Cixi, one of the most powerful women in Chinese history, was referred to as “Dragon Lady.” She was caricatured, particularly in the West, as a uniquely power-hungry, tyrannical, manipulative, and cold-blooded ruler. However, scholars agree that the Empress was unfairly represented. Her strategies, attitudes, and actions as a ruler were no more cunning than those of powerful males. Cixi also contributed to empowering and advancing opportunities for women in China.

Photography offered Cixi a means to take control of her representation. Her photographic images were crafted to destroy the caricatured image of her that circulated around the world. She crafted photographs to be self-defining and to articulate her view of herself as a ruler of China.

Xunling’s series of photographs of Cixi are artistic collaborations between a photographer and an Empress. Photography fascinated Cixi, and she carefully orchestrated the concept and composition of each photograph. In addition to her official portraits, Cixi created complicated group tableaux, portrayed herself in famous roles from Peking Opera, and posed as the compassionate bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. Cixi exercised absolute authority over her photographic portraits down to minute details. Xunling served as a collaborator and master technician helping Cixi achieve her artistic goals. Some photographs of Cixi were kept private until the Empress Dowager’s death.

Xunling’s photographs of Cixi are regarded by many historians as some of China’s earliest art photographs. Photographs of the Empress are of great scholarly interest to museum curators, art historians, and academics from a range of disciplines.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Hedda Morrison, née Hammer (German, 1908-1991)

Portrait of a Man with a Bird Cage

1930s

Silver gelatin print

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Hedda Morrison (1908 -1991) née Hammer, was born in Stuttgart, Germany and studied photography in Munich. She is one of the earliest identified female photographers of China. Morrison contracted polio as a young girl, which caused her to walk with a limp for the rest of her life. Her disadvantage increased her desire for adventure and travel. She moved to Beijing in 1933 to manage Hartung’s, a German-owned commercial photographic studio and shop in the Legation Quarter. Morrison also worked as a freelance photographer, selling individual prints and thematic albums of her work and creating photographs for books on China. Her photographs document lifestyles, trades, landscapes, religious practices, and architecture in China.

Morrison made this photograph of a man outdoors with a birdcage. In traditional Chinese culture birdcages hold cultural significance symbolizing an appreciation for art, nature, and balanced life.

Text from the Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

Loewentheil Photography of China Collection

10 West 18th Street 7th Floor

Open by appointment only: 646-838-4576 or 410-602-3002

![Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios. 'Bound Foot Exposed' [A Chinese Golden Lily Foot] 1870s Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios. 'Bound Foot Exposed' [A Chinese Golden Lily Foot] 1870s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/bound-foot-exposed.jpg)

![Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios. 'Caregiver' Caregiver [Woman carrying child] 1870s Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios. 'Caregiver' Caregiver [Woman carrying child] 1870s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/lai-fong-caregiver.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.