Exhibition dates: 23rd February – 3rd September 2023

Curator: Dr Kristina Lemke (Head of Photography, Städel Museum)

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Pompeii: The Oil Merchant’s Shop

After 1873

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

20.5 x 25.3cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Perhaps I was born in the wrong age for the more I view the wonders of 19th century photography the more disappointed I am at the vacuousness of a large proportion of contemporary photography.

In these photographs there seems to be a secret language of the photograph … where a certain piece of paper has a certain aesthetics of the image inherently buried in its structure which is then revealed. This is the place I long to be.

Thinking of the exhibition listings and texts for a recent major photographic biennale, the vacuousness of the concepts/themes and the resulting photographs was astounding. This, given the utter tsunami of the photo-digital and primacy of the visual in every day life, and every other aspect of our existence, is not a good situation. As my friend and artist Elizabeth Gertsakis observed, “‘Vacuousness’ is like a mirror without a capacity for reflection.” Or too much (self) reflection.

‘Self’ alone lacks both knowledge and authenticity.

Contemporary conceptual photography is full of false prophecies.

Perhaps the photographers need to ask: what really matters? What are the things in my life that I will not negotiate on. That I hold onto at the core of my being. Then perhaps the images that emerge from that investigation will again begin to mean something to them… and to others.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Städel Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

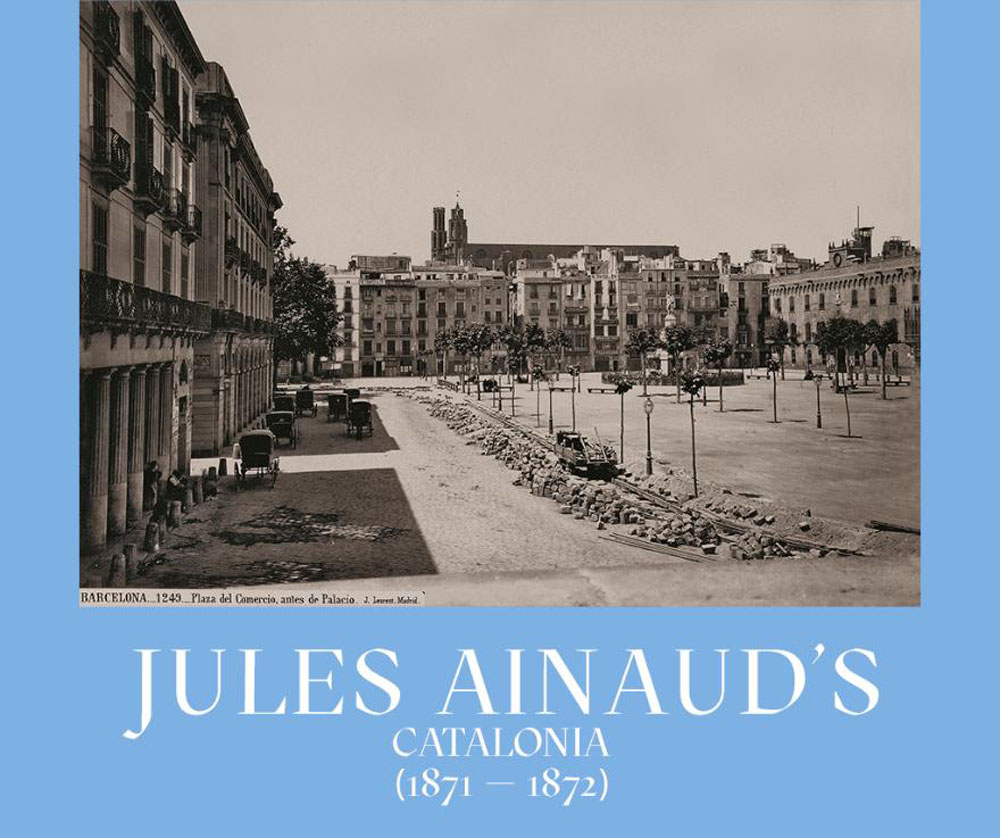

Gondoliers on the Grand Canal, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and the antiquities of Rome: numerous photographs by Giorgio Sommer, the Alinari brothers, Carlo Naya, and Robert Macpherson, among others, shaped the image of Italy as a place of longing. The Städel Museum is presenting a selection of early photographs of Italy. The exhibition unites altogether ninety major photos of the years 1850 to 1880 from the museum’s own collection.

About the exhibition

People have been dreaming their way to Italy for generations: the Mediterranean climate, multifaceted natural environment, and wealth of culture and art treasures have long since made the country a favourite travel destination. When the development of the railway system led to a boom in tourism in the second half of the nineteenth century, photography studios opened in the vicinity of the most popular sights. Even before the invention of the picture postcard, the photographic views on sale there were a prized souvenir for travellers, and also sold internationally by mail order. Johann David Passavant, then director of the Städel, began purchasing photos for the museum’s collection as far back as the 1850s. From these prints, both the art-interested public and students of the affiliated art academy were able to get an idea of southern Europe and its artistic and natural treasures. This brought distant countries closer while, simultaneously, the motifs in circulation determined what was considered worth seeing. To this day, the sceneries captured in photographs at that time continue to have an impact.

Text from the Städel Museum, Frankfurt

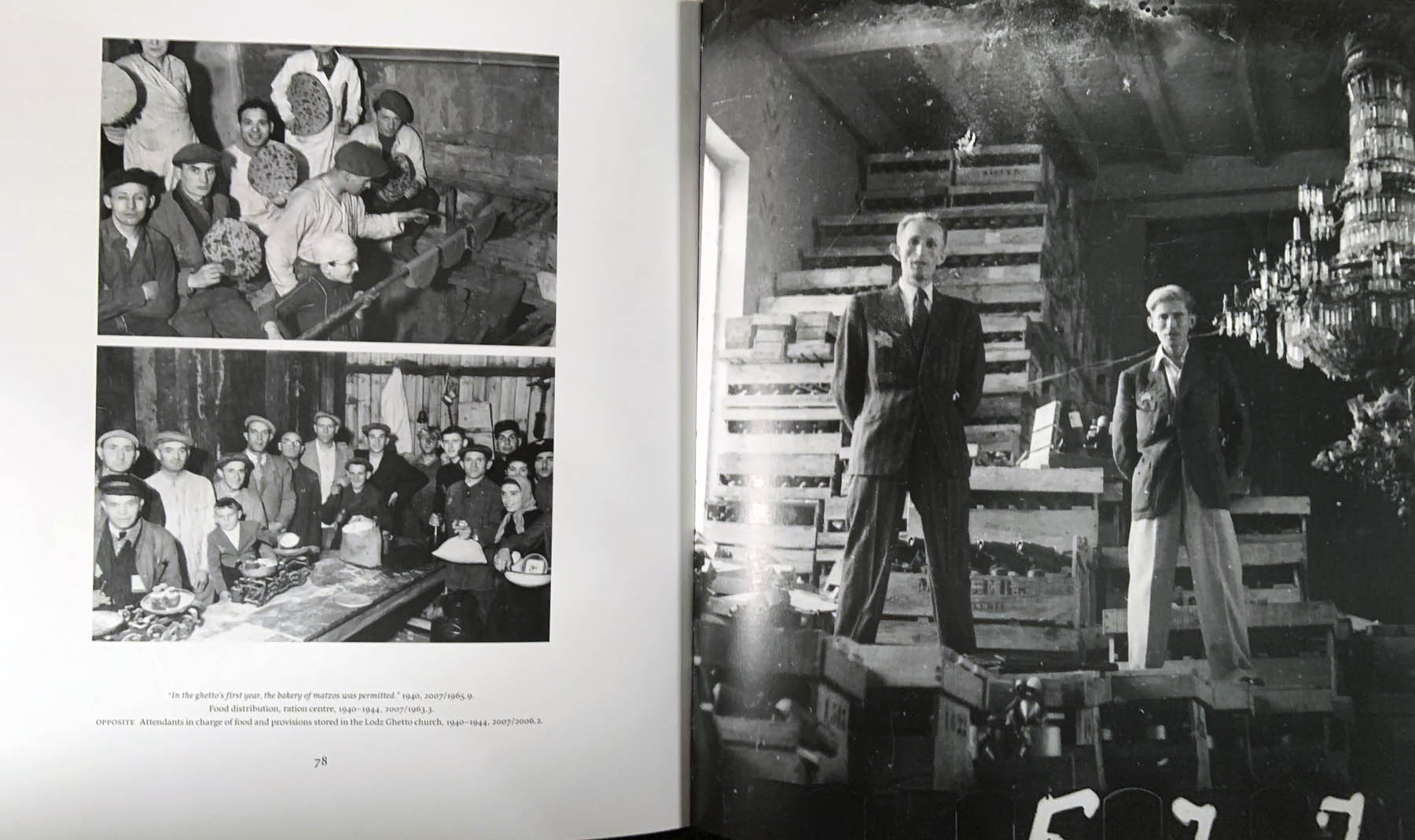

Installation views of the exhibition Images of Italy: Places of Longing in Early Photography at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing in the bottom image at left, Venice, Ca’ d’Oro (c. 1870-1880, below); and at centre, Carla Naya’s Venice: View of the Marciana Library, the Campanile and the Doge’s Palace (c. 1875, below)

Carlo Ponti (Italian 1823-1893)

Venice, Ca’ d’Oro

c. 1870-1880

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

24.9 x 33.1cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2012 as a gift from Alexander Rasor

The Ca’ d’Oro is the most famous of the more than 200 palaces lining the Canal Grande on both sides. Even today, a ride down the main waterway is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Venice. Captured in a frontal view from the canal and for the part isolated from its surroundings, the facade offers an opportunity for in-depth study of the architectural details. The rich decoration, complete with colonnades, tracery, and reliefs, is distinct down to the tiniest detail. The objective character of the view is underscored by the text on the back, which provides basic information on the building and its owners in a few sentences. By accompanying his prints with remarks of this kind in at least two languages, Carlo Ponti catered to a broad public – not only tourists but also exponents fo the young discipline of art history.

Wall text from the exhibition

Carlo Naya (Italian, 1816-1882)

Venice: View of the Marciana Library, the Campanile and the Doge’s Palace

c. 1875

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

41.3 x 54.1cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Against the backdrop of the Doge’s Palace on the Piazza San Marco, the gondola glides across the surface of the water, seemingly without a sound. At first sight, what we have before us is a snapshot bearing close resemblance to those taken by present-day visitors to Venice in their effort to capture the special charm of the onetime maritime republic. However, closer inspection reveals that there is nothing at all spontaneous about this image. The two gondoliers merely stage the poses required to propel the vessel forwards. In fact, they are using their oars to hold the gondola in place so that the shot of it will be in focus. Over the course of his long career, Carlo Naya photographed nearly eery one of Venice’s architectural landmarks – and thus advanced to become the city’s most prominent chronicler in the second half of the nineteenth century

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation views of the exhibition Images of Italy: Places of Longing in Early Photography at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing in the bottom image at centre, Robert Macpherson’s Tivoli: Waterfall (c. 1860-1865, below); and at right, Adolphe Braun’s Rome: Detail of Michelangelo’s Moses (c. 1875, below)

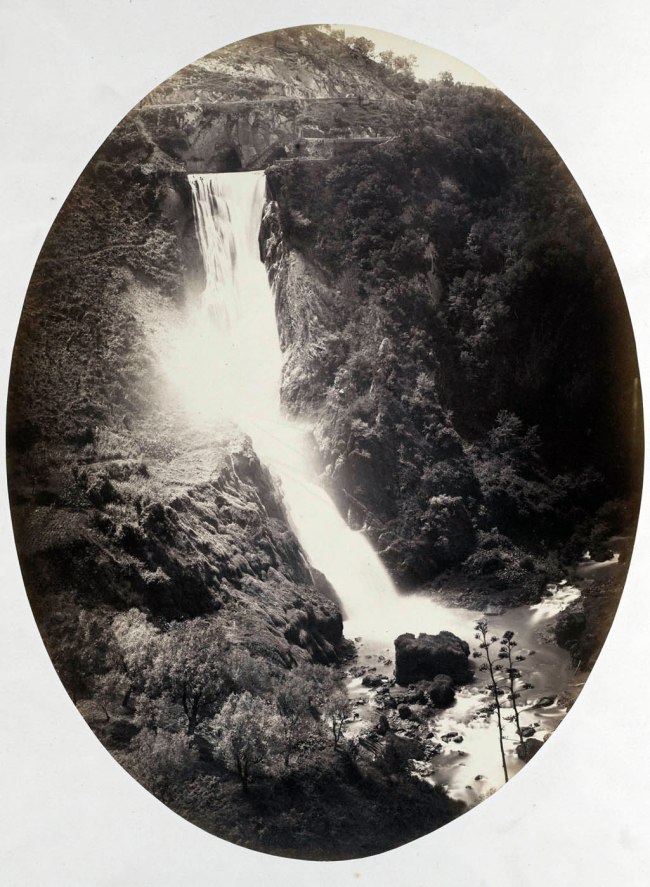

Robert Macpherson (Scottish lived Italy, 1814-1872)

Tivoli: Waterfall

c. 1860-1865

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

40 x 30.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

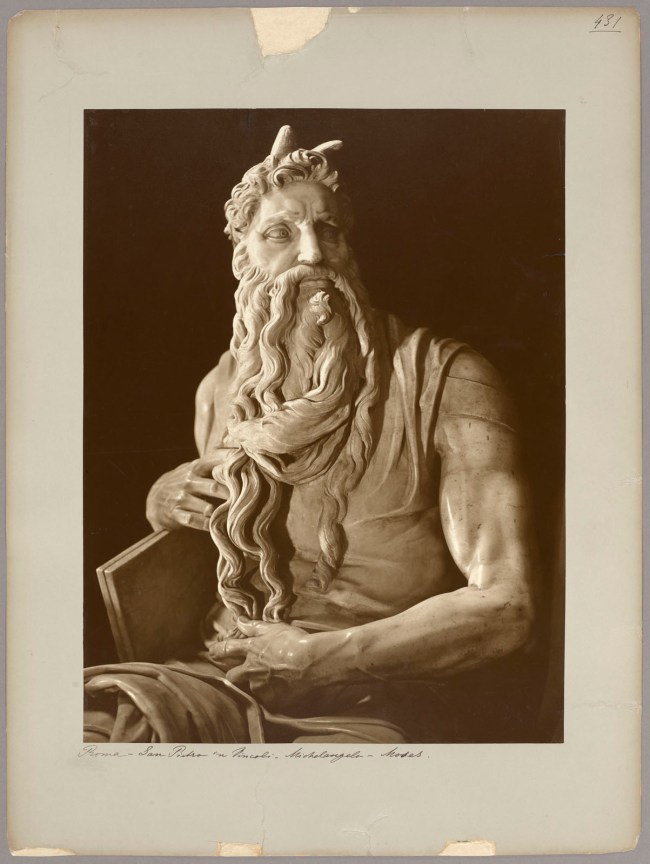

Adolphe Braun (French, 1811-1877)

Rome: Detail of Michelangelo’s Moses

c. 1875

Carbon print

48.6 x 36.1cm

Acquired in 2011 with support from the Kulturstiftung der Länder and the Hessischer Kulturstiftung, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

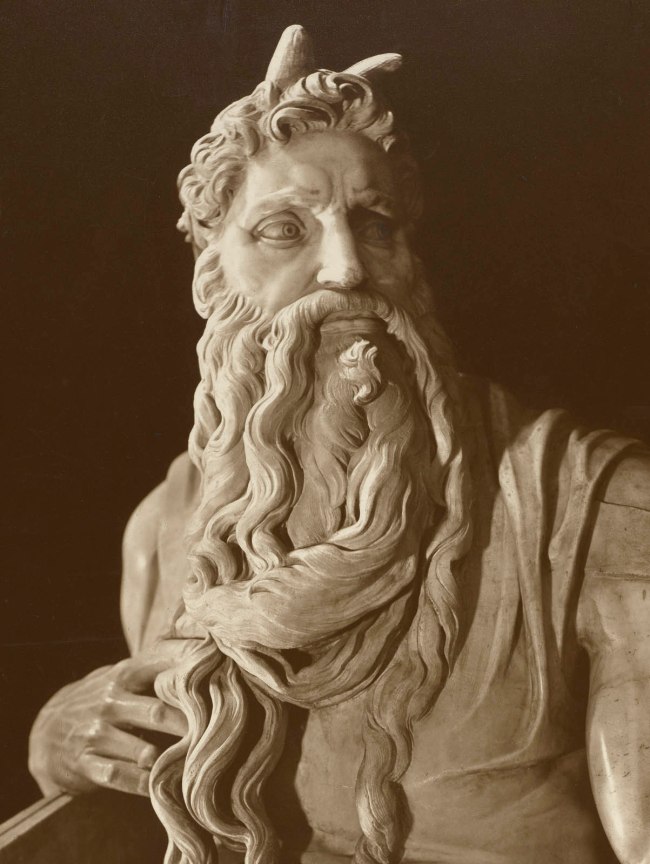

Owing to their immovability, sculptures were gratifying motifs for photographers. Every shot nevertheless posed many challenges. Meticulous calculations of the light were necessary to capture the plasticity of the three-dimensional works in the best way possible. Depending on the surface structure, various reflections might appear, and they were to be avoided. In the case of Michelangelo’s famous Moses from the tomb of Pope Julius II in Rome, Adolphe Braun concentrated on the upper body. The indeterminate dark background sets off the silhouette and three-dimensional forms of the white marble to particularly striking effect. To conceal the niche behind the sculpture, the photographer applied an asphalt solution to the negative. He moreover retraced certain details – for example the prophet’s left eye and the tip of his beard – with grey ink to heighten the contrasts.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Adolphe Braun (French, 1811-1877)

Rome: Detail of Michelangelo’s Moses (detail)

c. 1875

Carbon print

48.6 x 36.1cm

Acquired in 2011 with support from the Kulturstiftung der Länder and the Hessischer Kulturstiftung, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

Installation view of the exhibition Images of Italy: Places of Longing in Early Photography at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing Giorgio Sommer’s Gulf of Naples: View of Sorrento (c. 1880-1890, below)

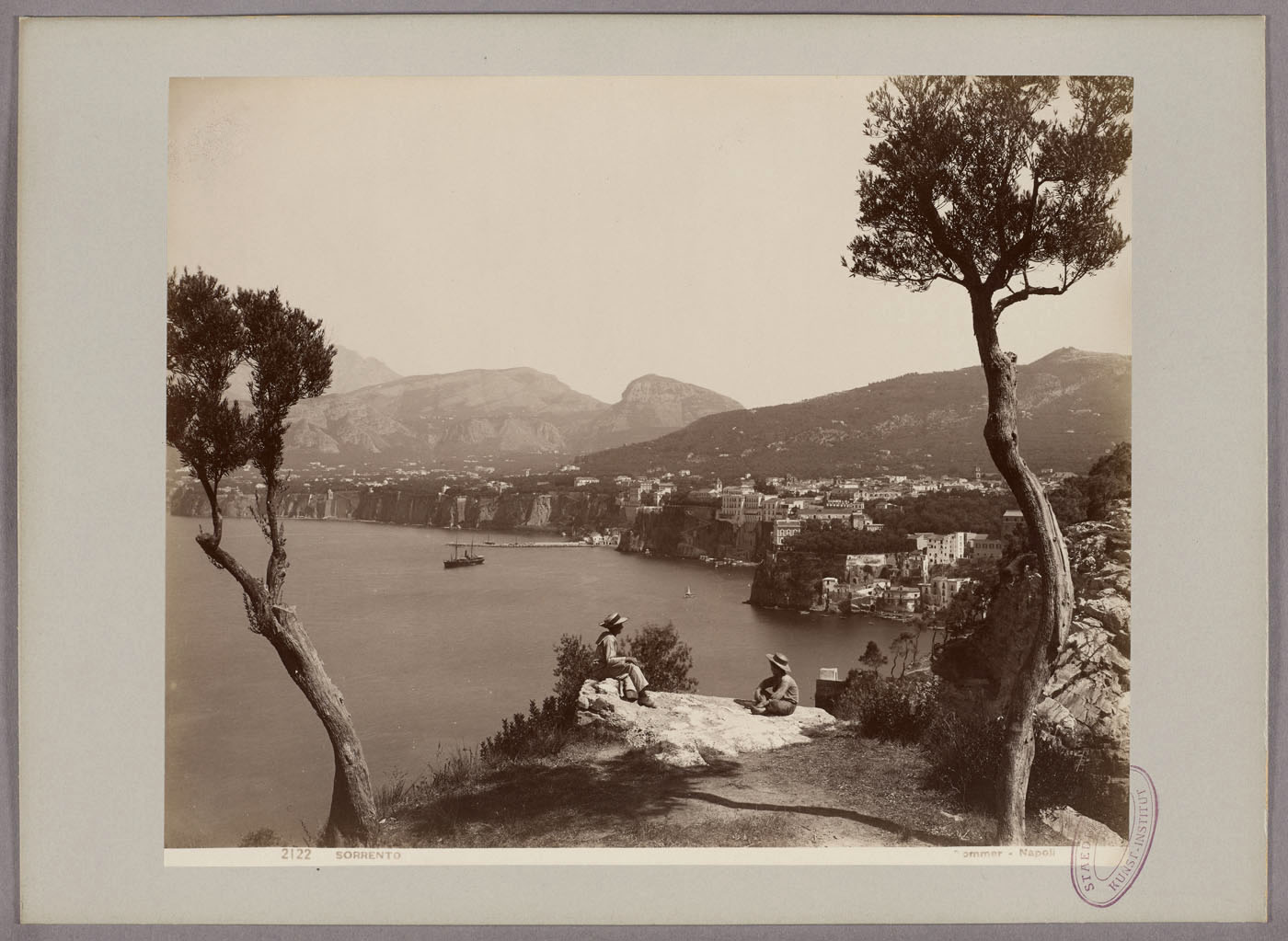

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Sorrento: View of the City from the West [Gulf of Naples: View of Sorrento]

c. 1880-1890

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

20.9 x 25.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Sorrento: View of the City from the West [Gulf of Naples: View of Sorrento]

c. 1880-1890

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

20.9 x 25.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Installation view of the exhibition Images of Italy: Places of Longing in Early Photography at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing at top left, Carlo Naya’s Venice. Cavalli Palace and the Grand Canal looking towards the Santa Maria della Salute church (c. 1877, below); and at bottom left, Carlo Naya’s Venice: View of the Canal Grande and Santa Maria della Salute from the Ponte della Carità (Moonlight Effect) (c. 1870, below)

Carlo Naya (Italian, 1816-1882)

Venice. Cavalli Palace and the Grand Canal looking towards the Santa Maria della Salute church

c. 1877

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

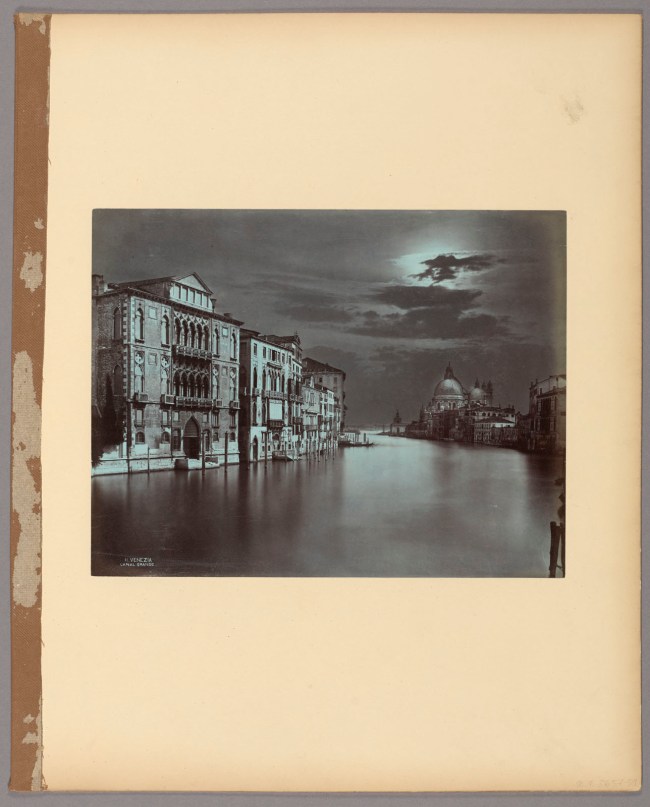

Carlo Naya (Italian, 1816-1882)

Venice: View of the Canal Grande and Santa Maria della Salute from the Ponte della Carità (Moonlight Effect)

c. 1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

The mysterious aura of the “Floating City” in the silvery light of the moon had already been discovered in painting. The painter Friedrich Nerly, for example, had made a name for himself with nocturnal views of Venice. In the photography medium, it was Carlo Naya who specialised in this area. He had to go to tremendous pains, however, to achieve comparable effects. He shot the buildings and the cloudy sky separately during the day, strongly underexposing the film, and then assembled the negatives. When the print was developed on bluish prepared photo paper, the lighter zones took on the appearance of reflected moonlight. The scenes were extremely popular with tourists because they intensified the myth of Venice conveyed by romantic literature – as a place of intrigues and secret love affairs. Naya and Nerly were acquainted, and the photographer reproduced the works of the painter from 1865 onwards.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914) (attributed)

Venice: View of the Canal Grande and Santa Maria della Salute from the Ponte della Carità

c. 1860-1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

18.0 x 23.9cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Early photographers took orientation from veduta painting, which owed its development to eighteenth-century tourism. As in Nerly’s composition, the dome of Santa Maria della Salute also dominates the scene in the shot by Carlo Naya. Here, however, it does not mark the centre of the composition but has been shifted to the right, drawing the viewer’s gaze somewhat further into the depths towards the Adriatic Sea. Owing to technical limitations, photographers had to do without the reproduction of atmospheric phenomena. The long exposure times transformed the waves into a smooth surface. To prevent the movement of the clouds in the sky from causing streaks, the photographer covered that area of the negative with black or red ink before exposure. The result was an evenly bright background that sets off the minute details of the pin-sharp architecture to especially good effect.

Text from the Städel Museum website

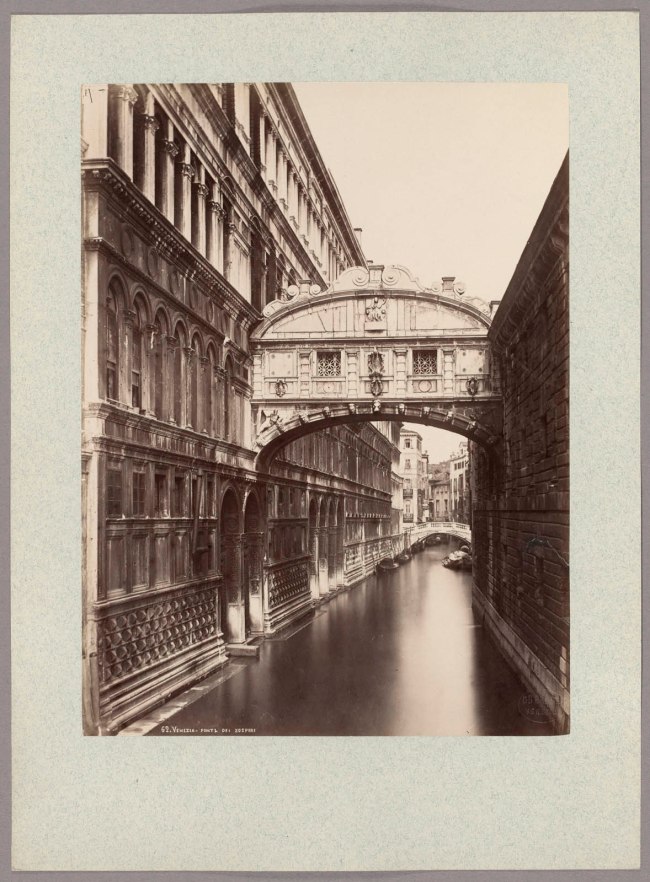

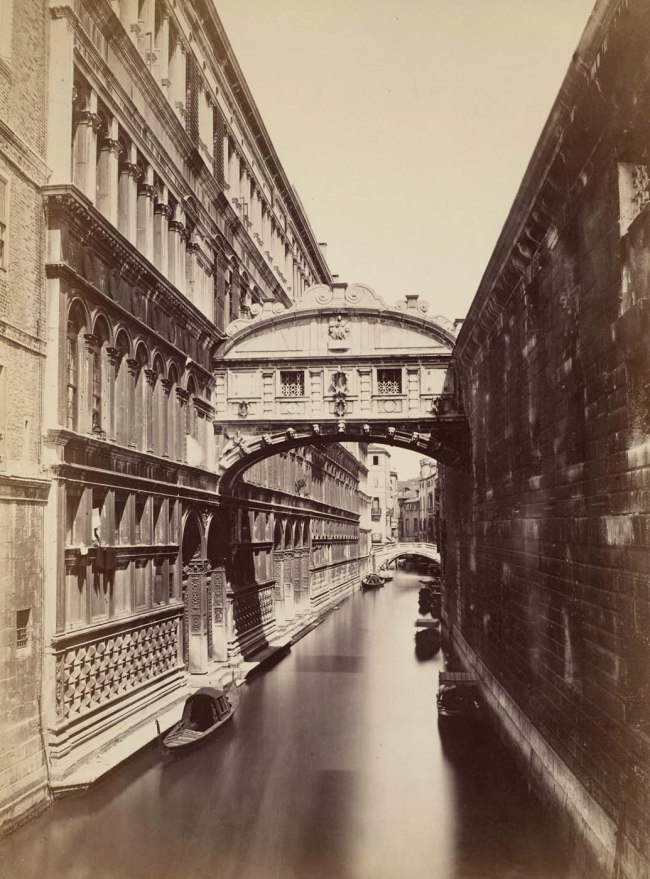

Installation views of the exhibition Images of Italy: Places of Longing in Early Photography at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing various photographers’ views (including Carlo Naya, Giovanni Battista Brusa and Carlo Ponti) of the Bridge of Sighs (see below)

Photo: Städel Museum – Norbert Miguletz

Giovanni Battista Brusa (Italian, active in Italy c. 1860-1880)

Venice, Bridge of Sighs

c. 1860

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

26.4 x 19.7cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

The so-called Bridge of Sighs led from the Doge’s Palace to the Prigioni Nuove, the “New Prison”. On their way across, convicts are said to have issued a sigh at the brief glimpse of freedom. The famous Venice landmark is one of the world’s most photographed bridges – and that was already the case in the nineteenth century. Countless photographers have adopted the same slightly oblique angle of view from the pedestrian bridge Ponte della Paglia opposite the south façade of the Bridge of Sighs. Their photos differ in the play of shadows – as determined by the respective position of the sun – the tonal richness, and the number of gondolas. This perspective on the bridge has etched itself in the collective visual memory and is still encountered in the social media today as the ideal angle for holiday pics.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Carlo Ponti (Italian, 1823-1893)

Venice, Bridge of Sighs

c. 1860-1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

35.2 x 25.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Travel routes to art: owing to its ancient past and wealth of art treasures, Italy had already long been a favourite destination for artists, scholars, and affluent citizens. In the mid-nineteenth century, the new medium of photography further inflamed the yearning for Italy. In the years that followed,thanks to the invention of the railway, more people than ever were able to set off for the South and the land of their dreams. Photographic views of the most popular destinations were sold as souvenirs right on site or marketed all over Europe by way of mail-order trade. The spread and technical refinement of photography moreover offered art scholars a means of studying artworks in faithful reproductions independently of location. It was in the 1850s that then director Johann David Passavant acquired the first photographs for the Städel collection. In the German art-historical perception, Italy and its art were outstanding and exemplary. Photographic views of the same accordingly account for a large proportion of the Städel Museum’s photography holdings. They have lost nothing of their appeal to this day.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Enrico Van Lint (Italian, 1808-1884)

Pisa: The Leaning Tower

c. 1855

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

14.5 x 10.9cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

To this day, the Leaning Tower of Pisa is one of the most photographed sights in Italy. In the 1850s, the trained sculptor Enrico Van Lint repeatedly photographed the tower and the other buildings on the Cathedral Square from different perspectives. Under good weather conditions, the exposure times ranged between 20 seconds and 7 minutes, on overcast days up to 18 minutes. In the second half of the nineteenth century – long before the invention of the picture postcard – travellers to Italy could purchase the small-scale prints as souvenirs. This view by Enrico Van Lint is one of the oldest objects in the Städel Museum’s ancient photography collection which, like the photo itself, dates back to around 1850.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Jakob August Lorent (American lived Italy, 1813-1884)

Venice: View of Santa Maria della Salute from the Molo

c. 1853

Albumen print from wax-paper negative

38.4 x 47.7cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2011 with support from the Kulturstiftung der Länder and the Hessische Kulturstiftung, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

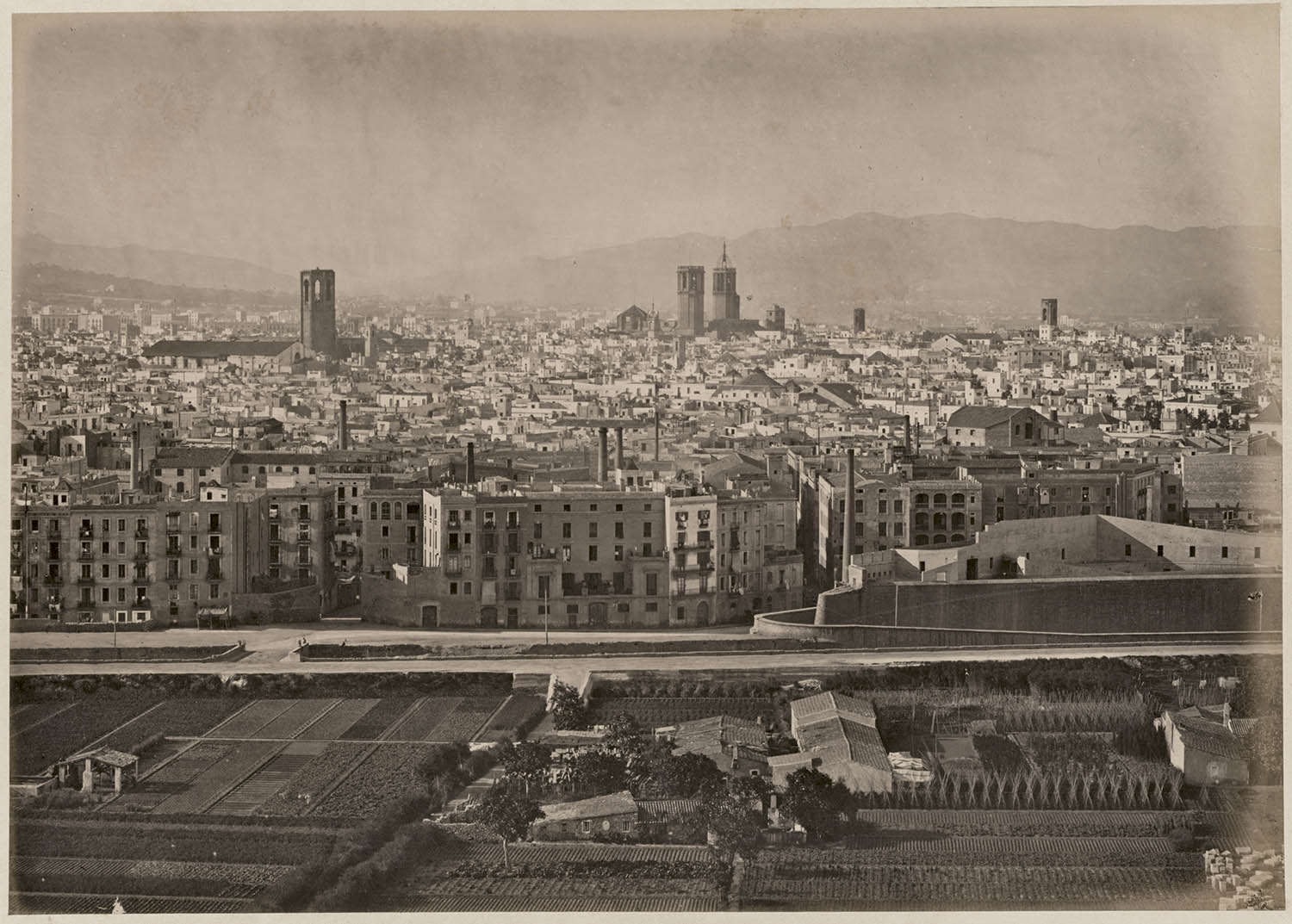

Gondoliers on the Grand Canal, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and the antiquities of Rome: Numerous photographs by Giorgio Sommer, the Alinari brothers, Carlo Naya, and Robert Macpherson, among others, shaped the image of Italy as a place of longing. From 23 February to 3 September 2023, the Städel Museum is presenting a selection of early photographs of Italy. The exhibition unites altogether ninety major photos of the years 1850 to 1880 from the museum’s own collection, taking visitors on a photographic tour along the best-known routes with stops in Milan, Venice, Florence, Rome, and Naples.

People have been dreaming their way to Italy for generations: the Mediterranean climate, multifaceted natural environment, and wealth of culture and art treasures have long since made the country a favourite travel destination. When the development of the railway system led to a boom in tourism in the second half of the nineteenth century, photography studios opened in the vicinity of the most popular sights. Even before the invention of the picture postcard, the photographic views on sale there were a prized souvenir for travellers, and also sold internationally by mail order. Johann David Passavant, then director of the Städel, began purchasing photos for the museum’s collection as far back as the 1850s. From these prints, both the art interested public and students of the affiliated art academy were able to get an idea of southern Europe and its artistic and natural treasures. This brought distant countries closer while, simultaneously, the motifs in circulation determined what was considered worth seeing. To this day, the sceneries captured in photographs at that time continue to have an impact.

Philipp Demandt, director of the Städel Museum, on the exhibition: “‘Images of Italy’ invites visitors along on a photographic journey: from Milan, Venice, and Florence to Rome and Naples. At the same time, the show offers insights into the history of the Städel Museum’s photography collection. Johann David Passavant, the museum’s director at the time, recognised the possibility of providing unlimited access to artworks and cultural treasures with the help of the photography medium early on – thus upholding our founder Johann Friedrich Städel’s guiding principle in splendid manner.”

The beginnings of the photography collection

With reproductions of artworks, photography also created new possibilities for the developing discipline of art history. It was in the 1850s that Johann David Passavant (1787-1861), then director of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut, acquired the first photographs for the museum. Amassed from a range of different sources, the prints convey the wealth of motifs and forms distinguishing a cultural region appreciated at the time as one of Europe’s most important. In the German art-historical perception, Italy and its art were outstanding and exemplary. Photographic views of them accordingly account for a large proportion of the Städel Museum’s photography holdings. They served visitors and students alike as study objects and a means of exploring proportions, light conditions, and perspectives.

“The exhibition retraces the unique history of the development of photography in nineteenth-century Italy. The first section looks at how the medium entered the Städel Museum in the form of collection items and took on ever greater importance in connection with the emerging tourist industry. From there the show proceeds to images of Italy’s most important destinations, thus presenting a comprehensive – and singularly striking – stocktaking of its cultural landscape in the period in question. The sights of those days still attract the photographic eye today. The views are often the same ones we travel to now,” comments exhibition curator Kristina Lemke.

A tour of Italy in pictures

After crossing the Alps, the classical route of a trip to Italy for purposes of education and enjoyment took travellers through the North to Milan, Genoa, and Venice, onwards from there to Florence and Rome, and finally to Naples and Pompeii. Starting in the 1850s, photographers recorded the main architectural and natural attractions in pictures. In terms of visual language, the photographs exhibit a close similarity to paintings, drawings, and prints. To lend images an idyllic mood, the photographers chose their vantage points with care, waited for a time of day that would produce a finely gradated play of light and shade, and integrated models to enliven their compositions. Many of them, such as Pompeo Pozzi (1817-1880), Gioacchino Altobelli (1814-1878), and Enrico Van Lint (1808-1884) had initially trained as artists. The rapidly growing photography trade also offered numerous emigrants a source of income: Robert Macpherson (1814-1872), Eugène Constant (active in Rome 1848-1852), Jakob August Lorent (1813-1884), Alfred August Noack (1833-1895), and Giorgio Sommer (1834-1914), for example, came to Italy from the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. The widely circulating motifs shaped the travel canon.

The photographic views popular back then convey an image of Italy as a timeless place of longing. Only to an extent can they be understood as mirrors of reality. The region was shaped above all by a national unification movement that got underway after 1815: the Risorgimento, which – punctuated by frequent military disputes – would only end in 1870 with the capture of Rome. Yet the political conflicts did little to discourage the development of tourism and photography taking place in the same decades.

Photographers and motifs – a selection

To this day, the Leaning Tower of Pisa is one of the most photographed sights in Italy. In the 1850s, the trained sculptor Enrico Van Lint (Pisa 1808-1884) repeatedly photographed the tower and the other buildings on the Cathedral Square from different perspectives. Under good light conditions, the exposure times ranged between 20 seconds and 7 minutes, on overcast days between 8 and 18 minutes. Dating from around 1855, the view by Van Lint on display in the show is one of the oldest objects in the Städel Museum’s photography collection.

Alfred Noack (Dresden 1833 – Genoa 1895) completed artistic training in Dresden before emigrating to Italy in the late 1850s. After four years in Rome, he opened a photo studio in Genoa that served him as a base for explorations of the Ligurian Riviera. Here he captured the Sestri Levante section of the coast, a popular holiday destination, in photos he composed in painting-like manner. By reducing the depth of field after the manner of traditional landscape painting, Noack was able to create suggestive atmospheric images.

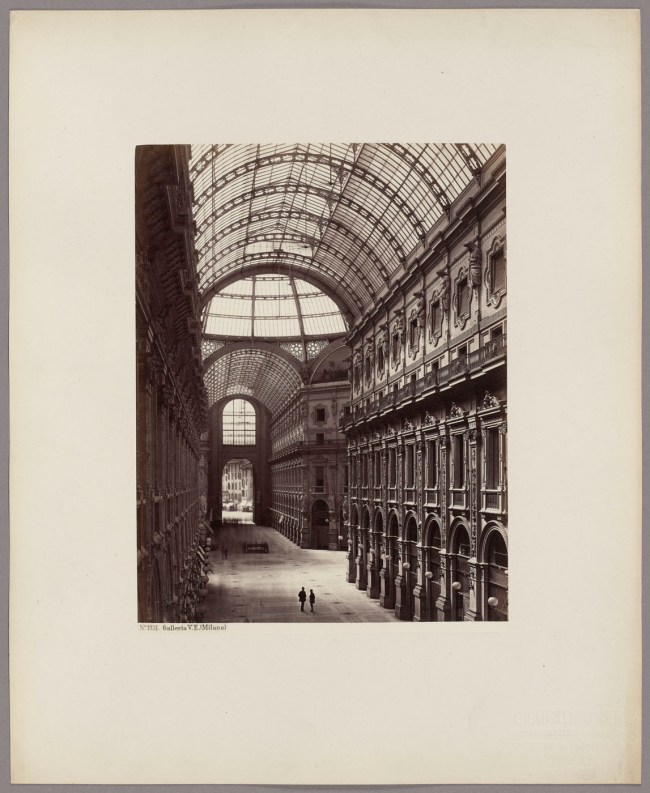

In 1856, the photographer Georg Sommer (1834 – Naples 1914) moved to Italy and, under the name Giorgio Sommer, became one of Naples’s most successful entrepreneurs. The exhibition presents, among others, his views of the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II (c. 1868-1873) in Milan, the island of Capri, and a spectacular series of shots capturing the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in April 1872. Sommer photographed the rare natural spectacle at half-hour intervals from a boat lying at anchor a safe distance away in the Gulf of Naples. The Leipzig Illustrierte Zeitung featured woodcut reproductions of these images that can be regarded as forerunners of the later emerging field of photojournalism.

Carlo Naya (Tronzano Vercellese 1816 – Venice 1882) advanced to become the most prominent chronicler of Venice in the second half of the nineteenth century. At first sight, his photo of a gondola against the backdrop of the Library of Saint Mark, Campanile, and Doge’s Palace (c. 1875) looks like a snapshot, but nothing about it is spontaneous. Over the course of his long career, Naya captured nearly every one of Venice’s architectural landmarks, among them the so-called Bridge of Sighs. In the nineteenth century, the famous sight was one of the world’s most photographed bridges. Countless photographers have set up their camera on the same spot. The resulting view of the bridge has etched itself in the collective visual memory and is still encountered in the social media today as the ideal angle for holiday pics.

Carlo Ponti (Sagno 1823 – Venice 1893) produced views of popular architectural sights in Venice. Among the photos by Ponti on display in the exhibition is one of the Ca’ d’Oro (c. 1870-1880) providing information about the edifice in two languages on the back. With this souvenir, the photographer catered not only to tourists, but also to persons interested or specialising in the history of art and culture. In the image, the building’s rich decoration – with colonnades, tracery, and reliefs – is distinct down to the tiniest detail.

Leopoldo Alinari, who had trained as an engraver, went into business for himself as a photographer in 1852. Two years later he founded a studio with his brothers Romualdo and Giuseppe. In addition to portraits, the Fratelli Alinari offered views of the city’s famous monuments. In 1859, they came to international fame with reproductions of drawings by Raphael. From that time forward, photographic reproductions of artworks, for example from the Uffizi, were a permanent feature of the family company’s product range – and likewise among the Städelsches Kunstinstitut’s purchases.

The exhibition also presents the remarkable photographic composition entitled Rome: Fishermen on the Tiber near the Castel Sant’Angelo (c. 1860) by Gioacchino Altobelli (Terni 1814 – Rome 1878), who had previously been active as a history and portrait painter. Altobelli was one of Rome’s most successful photographers. The Ponte Sant’Angelo with its Baroque sculptures by Gian Lorenzo Bernini divides the pictorial field about halfway between top and bottom, leaving plenty of space for the reflections of St Peter’s Basilica and the Castel Sant’Angelo in the smooth surface of the Tiber. The photographer was judicious in his choice of staffage in the foreground: the figures serve to point the viewer’s gaze to the main monuments.

Meticulous calculations of the light were necessary to capture the plasticity of sculptures in the best way possible. That is because, depending on the surface structure, various reflections might appear, and they were to be avoided. In the case of Michelangelo’s figure of Moses from the tomb of Pope Julius II in Rome, Adolphe Braun (Besançon 1811 – Dornach 1877) concentrated on the upper body. To conceal the niche behind the sculpture, the photographer applied an asphalt solution to the negative. He moreover retraced certain details – for example the prophet’s left eye and the tip of his beard – with grey ink to heighten the contrasts.

In the shot of the Pantheon (c. 1870) by the Fratelli D’Alessandri, the building still boasts a feature today no longer extant – the bell towers by the great Roman Baroque artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Thanks to the angle of view, the photograph captures not only the temple façade with its rectangular outline, but also the domed rotunda. At the same time it portrays the urban setting, complete with cafés, shops, and pedestrians, creating a suspenseful contrast between the permanence of the structure and the fugacity of the moment.

For nineteenth-century travellers to Rome, an excursion to the surrounding region was a must. In Tivoli, the great waterfall in the park of the Villa Gregoriana had already been attracting artists since the eighteenth century. They usually concentrated on staging the spectacular natural scenery in interplay with the remains of ancient culture. In Tivoli: Waterfall (c. 1860-1865), Robert Macpherson (Edinburgh 1814 – Rome 1872) – a surgeon by training – focussed solely on the plunging water and the bright reflections off the mist it causes. The oval shape heightens the image’s poetic effect and draws all the more attention to the motif.

Press release from the Städel Museum

A. De Bonis (Italian, active 1850-1870) (attributed)

Rome: Man Reading in the Garden of the Cloister of San Giovanni in Laterano

c. 1855-1860

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

25.5 x 19.6cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2011 with support from the Kulturstiftung der Länder and the Hessischer Kulturstiftung, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

Fratelli D’Alessandri (Italian, 1858-1930)

Antonio D’Alessandri (Italian, 1818-1893)

Paolo Francesco D’Alessandri (Italian, 1827-1889)

Rome: Pantheon

c. 1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

17.1 x 21.9cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

No other metropolis offered a comparable rich and closely interwoven legacy of built monuments and art treasures from antiquity to the modern age. The Pantheon is a prime manifestation of Rome’s special status as the “Eternal City”. The best-preserved edifice of Roman antiquity, it was converted into a Christian church in AD 609. Since the Renaissance it has moreover served as the final resting place of prominent personages, among them Raphael. In this shot, the building still boasts a feature today no longer extant – the bell towers by the great Roman Baroque artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Thanks to the angle of view, the photograph by the D’Alessandri brothers captures not only the temple façade with its rectangular outline, but also the domed rotunda. At the same time it portrays the urban setting, complete with cafés, shops, and pedestrians, creating a suspenseful contrast between the permanence of the structure and the fugacity of the moment.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Jakob August Lorent (American lived Italy, 1813-1884)

Venice: The Horses of San Marco

c. 1853

Salt print mounted on cardboard

33.6 x 46.4cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2011 with support from the Kulturstiftung der Länder and the Hessische Kulturstiftung, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

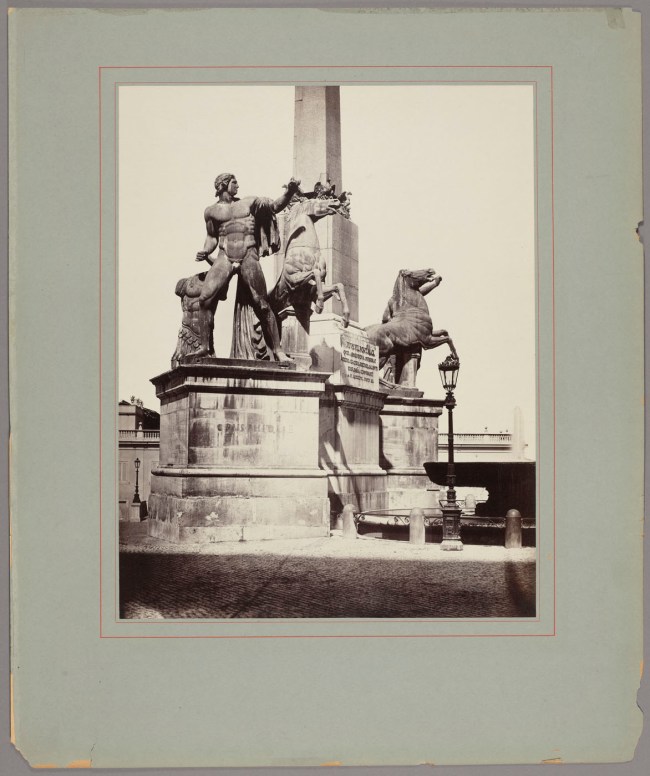

Robert Macpherson (Scottish lived Italy, 1814-1872)

Rome: The Fountain of the Dioscuri on Quirinal Hill

1860

39.6 x 30.9cm

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2011 with support from the Kulturstiftung der Länder and the Hessischer Kulturstiftung, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

Carlo Naya (Italian, 1816-1882)

Venice: Riva degli Schiavoni (with Carlo Naya’s studio in the left foreground)

c. 1865-1875

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

43.7 x 53.9cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2011 with support from the Kulturstiftung der Länder and the Hessischer Kulturstiftung, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

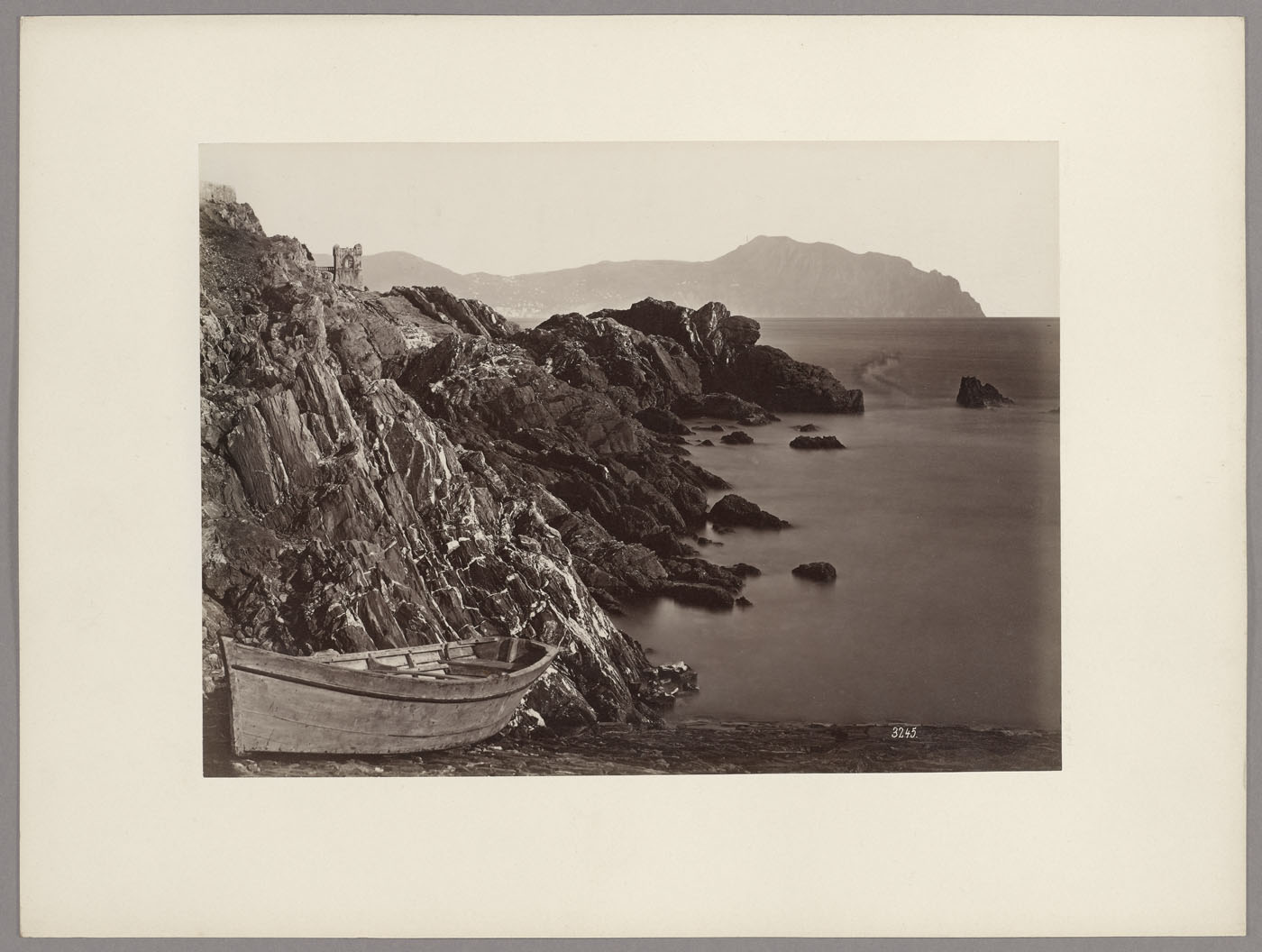

August Alfred Noack (Italian, 1833-1895)

Genoa: Fishing Boat on the Beach of Nervi, View of Torre Gropallo and Monte Fasce

c. 1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

20.5 x 28.0cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

In the 1850s Alfred Noack immigrated to Italy, like Giorgio Sommer. After four years in Rome he opened a photographic studio in Genoa and intensely studied the landscapes of the coast of Liguria. His photographs of the beach of Nervi, with rocky bits of land reaching diagonally into the picture plane, appear exceptionally modern. The angle he chose draws the viewer into the picture, an effect heightened by the abandoned boat. The careful tinting makes the single elements of the landscape melt into monotone areas, clearly distinguished by sharp contours.

Text from the Städel Museum website

August Alfred Noack (Italian, 1833-1895)

Riviera di Levante: The Coast near Sestri Levante

c. 1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

21.6 x 27.8cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Alfred Noack completed artistic training in Dresden before emigrating to Italy in the late 1850s. After four years in Rome, he opened a photo studio in Genoa which served him as a base for explorations of the Ligurian Riviera. Here he captured the Sestri Levante section of the coast, a popular holiday destination, in a photo composed in painting-like manner. The splendid agave blossom in the foreground leads the gaze from lower left to upper right, close up to far away. By reducing the depth of field after the manner of traditional landscape painting, Noack has achieved a suggestive atmospheric image. This effect is further enhanced by the path alluded to at the lower left, which prompts the viewers to stroll through the Mediterranean landscape themselves – at least in their imaginations.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Gioacchino Altobelli (Italian, 1814-1878?)

Rome: Fishermen on the Tiber near the Castel Sant’Angelo

c. 1860

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

27.7 x 38.0cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Gioacchino Altobelli had previously been active as a history and portrait painter. Here he staged Christian Rome in a photographic composition distinguished by the utmost harmony. The Ponte Sant’Angelo with its Baroque sculptures by Gian Lorenzo Bernini divides the pictorial field about halfway between top and bottom, leaving plenty of space for the reflections of St Peter’s Basilica and the Castel Sant’Angelo in the smooth surface of the Tiber. The photographer was judicious in his choice of staffage in the foreground. The pipe smoker’s fishing rod and the long stick leaning against the shoulder of the man on the bank point the viewer’s gaze to the main monuments, which appear all the more imposing as a result. At the same time, with the fishing motif Altobelli was alluding to symbolic imagery widespread in the Christian pictorial tradition. He was one of the city’s most successful photographers.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Edizioni Brogi (Italian, active 1860s-1920s publisher)

Giacomo Brogi (Italian, 1822-1881)

Carlo Brogi (Italian, 1850-1925) son of Giacomo Brogi

Naples: Macaroni Maker

c. 1880-1890

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

19.9 x 25.2cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Naples held great appeal for tourists not only because of its charming coastal scenery and awe-inspiring Mount Vesuvius, but also thanks to its customs and traditions. Particularly from the 1880s onwards, Italian-based photographers increasingly marketed studies of human beings that shaped and continually fuelled the cliché of the poor but carefree population of Southern Italy. The Edizioni Brogi company staged its native performers against the backdrop of an osteria. In the foreground, a scruffy-looking man and two barefoot boys stand side by side, grinning cheerfully into the camera while eating macaroni with their hands as if it was the most natural thing in the world. To lend the artificial arrangement a connection to reality, Brogi claims in the printed text above that the photograph had been made “from life”.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Fratelli Alinari (founded 1852)

Leopoldo Alinari (Italian, 1832-1865)

Romualdo Alinari (Italian, 1830-1891)

Giuseppe Alinari (Italian, 1836-1890)

Florence: Loggia dei Lanzi

c. 1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

41.2 x 32.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Along with Venice, Rome, and Naples, Florence also made a name for itself as an important centre for photography in Italy. It was there that Leopoldo Alinari, who had trained as an engraver, set up his own business in 1852. Two years later his brothers Romualdo and Giuseppe founded a photo studio. In addition to portraits, the Alinari offered views of the city’s famous monuments which they sold primarily to tourists. In 1859, they came to international fame with reproductions of drawings by Raphael in photographs of “high artistic value”, as the Photographisches Journal reported. From that time forward, photographic reproductions of artworks, for example from the Uffizi, were a permanent feature of the family company’s product range. Still in existence today, the Alinari Archive is a unique document of Italian art and architecture.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Giorgio Sommer

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Florence: Fountain of Neptune

c. 1860-1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

18.1 x 24.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Rome: The Market on Piazza Navona

c. 1862

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

27.4 x 37.4cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2011 with support from the Kulturstiftung der Länder and the Hessischer Kulturstiftung, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Amalfi: Valle dei Mulini

c. 1860-1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

17.6 x 23.5cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Amalfi: View from the Coast

c. 1860-1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

18.4 x 24.3cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

The area on the Gulf of Salerno figured prominently in Giorgio Sommer’s product range. By photographing striking sites from different perspectives, he amassed a large repertoire of multifarious views. Here we see the harbour of the once-powerful maritime republic Amalfi from a slightly elevated vantage point. On the beach, nets have been spread out between the boats for patching. The long masts of the sailing vessels point our gaze to the characteristic steep cliffs. According to the Baedeker travel guide of 1867, the region offers “a charming new landscape scene at almost every turn”. The intricately interleaved and overlapping houses have carved out a place for themselves at the foot of the rugged slopes.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914) (attributed)

Amalfi: Seaside Promenade

c. 1860-1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

17.8 x 24.1cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

The area on the Gulf of Salerno figured prominently in Giorgio Sommer’s product range. By photographing striking sites from different perspectives, he amassed a large repertoire of multifarious views. Here we see the harbour of the once-powerful maritime republic Amalfi from a slightly elevated vantage point. On the beach, nets have been spread out between the boats for patching. The long masts of the sailing vessels point our gaze to the characteristic steep cliffs. According to the Baedeker travel guide of 1867, the region offers “a charming new landscape scene at almost every turn”. The intricately interleaved and overlapping houses have carved out a place for themselves at the foot of the rugged slopes.

Wall text from the exhibition

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Milan: Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II

c. 1868-1873

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

24.0 x 18.2cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

The shopping mall erected in Milan between 1865 and 1867 inspired praise from the author of Baedeker’s Handbook for Travellers (1870): “Among Europe’s glass arcades, this is the most beautiful and magnificent by far.” Giorgio Sommer captured the prestigious edifice in a single shot. On the one hand the angle of view emphasises the longitudinal axis connecting the Piazza della Scala and the Piazza del Duomo. On the other hand, the choice of a vantage point to the left of the centre enables the onlooker to appreciate the richly ornamented arcades. Sommer moreover made use of the light entering from above to bring out the delicate structure of the architecture.

Wall text

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Milan: Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II

c. 1868-1873

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

24.0 x 18.2cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Naples: The Eruption of Mount Vesuvius on 26 April 1872, 3.00 pm, 1872

1872

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

18.1 x 24.1cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, property of the Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

When Mount Vesuvius began emitting masses of lava in April 1872, Giorgio Sommer photographed the rare natural spectacle at half-hour intervals from a boat lying at anchor a safe distance away in the Gulf of Naples. In the end he had created a series of shots documenting the volcanic emission. A display of the omnipotence of natural forces, the tower of ash several kilometres high sends shivers down the viewer’s spine. The photographs met with keen interest not only from tourists. In the Illustrierte Zeitung (Leipzig) they were also reproduced as woodcuts that can be regarded as forerunners of photojournalism. Unlike the relatively matter-of-fact photos that served as their basis, the printed reproductions turn the scene into an emotionally charged landscape veduta. The gulf and the city of Naples fill the foreground; the fire-spewing mountain looms up behind them like a mighty omen.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914) (attributed)

Naples: View of Capri from Massa Lubrense

c. 1860-1865

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

18.0 x 23.8cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

On his wanderings in Southern Italy, Giorgio Sommer concentrated more than most of his photographer colleagues on the beauty of the landscape. He had the help of natural circumstances to arrive at this especially striking shot of Capri, an island in the Gulf of Naples that is still as popular with tourists as ever. The olive trees at the left and right frame it in such a way as to create a picture within a picture. The use of treetops for this purpose is a classical element of landscape painting. The two barefoot boys at the left not only enliven the composition but also serve as scale figures and underscore the vastness of natural setting. At the same time, they point to another area of Sommer’s repertoire: genre scenes from what was imagined to be typical everyday life in Southern Italy.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914) (attributed)

Naples: Largo del Municipio

c. 1860-1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

18.1 x 23.9cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

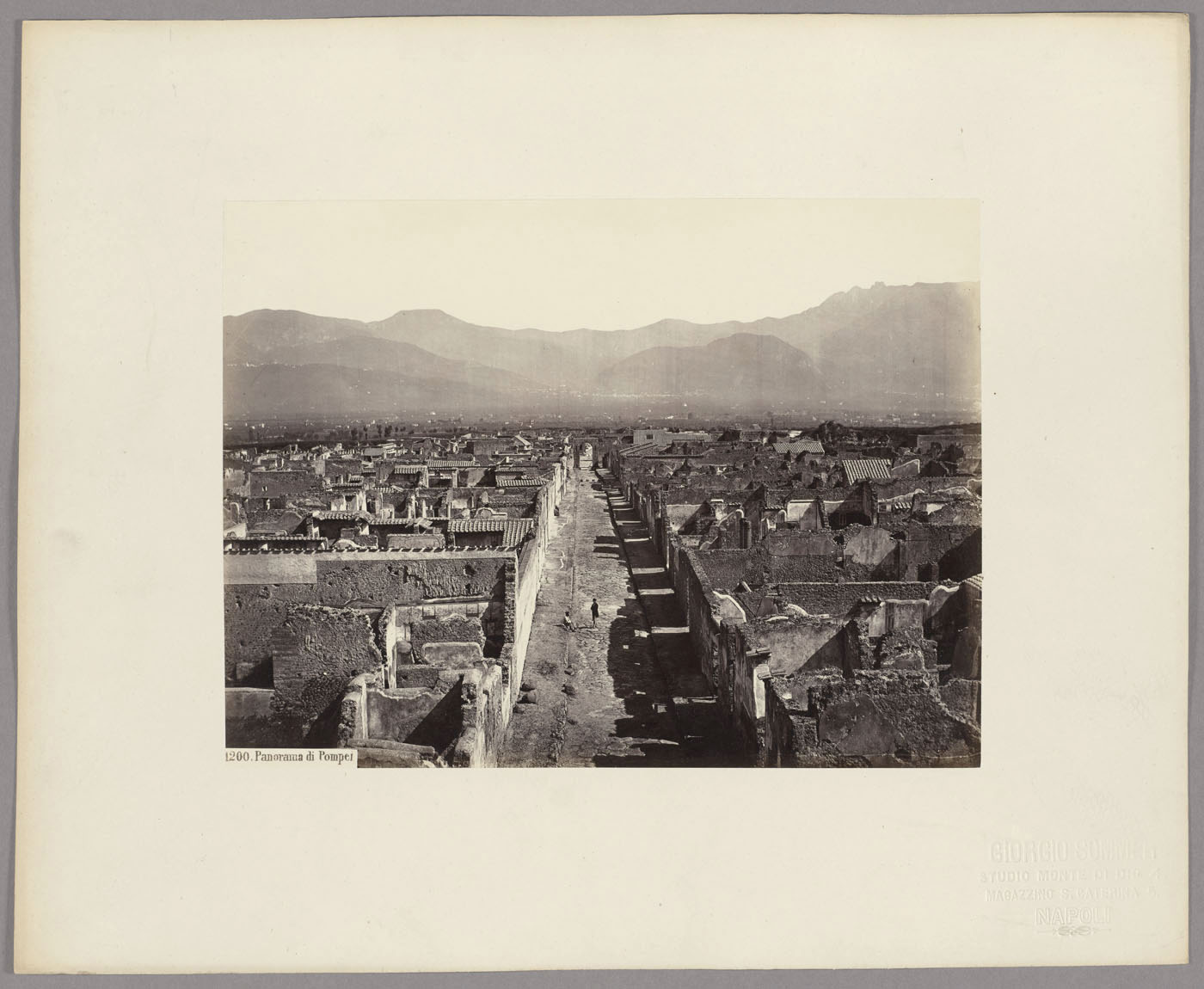

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Pompeii: Panoramic View

c. 1860-1870

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

18.2 x 24.1cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

Monreale: Panoramic View

Before 1886

Albumen print mounted on cardboard

20.2 x 25.6cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in the 19th century

Städel Museum

Schaumainkai 63

60596 Frankfurt

Opening hours:

Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday – Sunday 10.00am – 6.00pm

Thursday 10.00am – 9.00pm

Monday closed

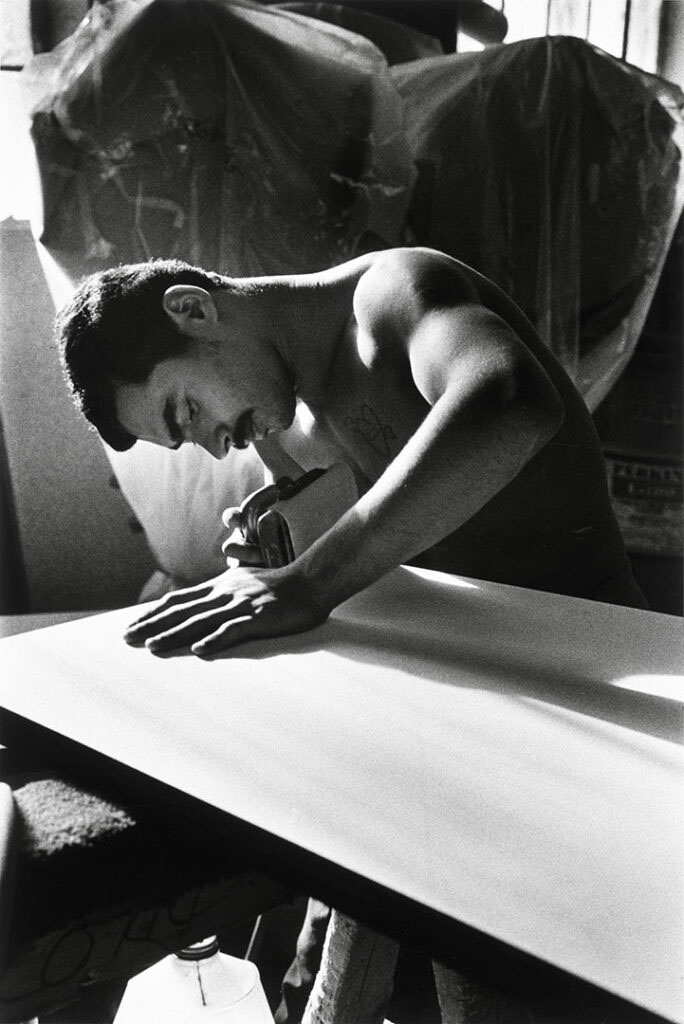

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Boulevard de Clichy, Paris' [Boulevard de Clichy, París] 1951 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Boulevard de Clichy, Paris' [Boulevard de Clichy, París] 1951 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/03.-id40_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aubervilliers, France' [Aubervilliers, Francia] 1947 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aubervilliers, France' [Aubervilliers, Francia] 1947 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/02.-id37_p.jpg?w=801)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Concentric Circles, Construction Site, New York' [Círculos concéntricos, obra, Nueva York] 1952 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Concentric Circles, Construction Site, New York' [Círculos concéntricos, obra, Nueva York] 1952 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/11.-id737_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Manhole, Times Square, New York' [Tapa de alcantarilla, Times Square, Nueva York] 1954 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Manhole, Times Square, New York' [Tapa de alcantarilla, Times Square, Nueva York] 1954 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/08.-id68_p-b.jpg?w=689)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, New York' [Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, Nueva York] 1954 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, New York' [Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, Nueva York] 1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/09.-id1_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Nancy Listening to Jazz, Greenwich Village, New York' [Nancy escuchando jazz, Greenwich Village, Nueva York] 1958 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Nancy Listening to Jazz, Greenwich Village, New York' [Nancy escuchando jazz, Greenwich Village, Nueva York] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/10.-id4211_p.jpg?w=744)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman Holding Newspaper, New York' [Mujer sujetando un periódico, Nueva York] 1946 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman Holding Newspaper, New York' [Mujer sujetando un periódico, Nueva York] 1946](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/01.-id1732_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Train Station Near Málaga, Spain' [Estación de tren cerca de Málaga, España] 1951 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Train Station Near Málaga, Spain' [Estación de tren cerca de Málaga, España] 1951](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/05.-id74_p.jpg?w=675)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Tony, "Pepe and Tony, Spanish Fishermen", Ibiza, Spain' [Tony, "Pepe y Tony, pescadores españoles", Ibiza, España] 1956 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Tony, "Pepe and Tony, Spanish Fishermen", Ibiza, Spain' [Tony, "Pepe y Tony, pescadores españoles", Ibiza, España] 1956](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/04.-id4569_p.jpg?w=669)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Commuters, Evening Train, Penn Station, New York' [Volviendo del trabajo en el tren de la tarde, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Commuters, Evening Train, Penn Station, New York' [Volviendo del trabajo en el tren de la tarde, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/06.-id179_p.jpg?w=684)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman with White Glove, Penn Station, New York' [Mujer con guante blanco, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman with White Glove, Penn Station, New York' [Mujer con guante blanco, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/07.-id461_p.jpg?w=683)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aluminum Foundry, Soviet Union' [Fundición de aluminio, Unión Soviética] 1975 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aluminum Foundry, Soviet Union' [Fundición de aluminio, Unión Soviética] 1975](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/13.-id648_p.jpg?w=686)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Assembly Line Worker, Long Island City, New York' [Trabajadora en cadena de montaje, Nueva York] 1972-1974 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Assembly Line Worker, Long Island City, New York' [Trabajadora en cadena de montaje, Nueva York] 1972-1974](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/12.-id96_p-1.jpg?w=691)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Demonstrators on March in Support of United Farm Workers, New York' [Manifestantes en una marcha de apoyo a la Unión de Campesinos, Nueva York] 1975-1976 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Demonstrators on March in Support of United Farm Workers, New York' [Manifestantes en una marcha de apoyo a la Unión de Campesinos, Nueva York] 1975-1976](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/14.-id1307_p.jpg?w=685)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Self-Portrait, Santiago, Chile' [Autorretrato, Santiago de Chile] 2000-2001 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Self-Portrait, Santiago, Chile' [Autorretrato, Santiago de Chile] 2000-2001](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/16.-id1627_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Women from Texas, Fifth Avenue, New York' [Mujeres de Texas, Fifth Avenue, Nueva York] 1975 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Women from Texas, Fifth Avenue, New York' [Mujeres de Texas, Fifth Avenue, Nueva York] 1975](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/15.-id145_p.jpg?w=694)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris' [Jardin du Luxembourg, París] 1997 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris' [Jardin du Luxembourg, París] 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/17.-id2978_p.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.