Exhibition dates: 27th July – 27th October 2013

Many thankx to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Giovanni Castell (German, b. 1964)

Tulpomania 3 / Vergissmeinnicht

2009

C-Print/Plexiglas (Diasec)

130 x 160cm

Courtesy the artist

Fischli/David Weiss

Peter Fischli (Swiss, b. 1952) and David Weiss (Swiss, 1946-2012)

Mushrooms / Funghi 18

1997-1998

Inkjet print with Polyester Foil

73.8 x 106.7cm

Bavarian State Painting Collections Munich – Pinakothek der Moderne

Acquired by PIN, Friends of the Art Gallery of modernity for the Modern Collection Art

© The artists; Gallery Sprueth Magers Berlin, London; Galerie Eva Presenhuber Zurich; and Matthew Marks Gallery New York

Michael Wesely (German, b. 1963)

Still life (29.12. – 4.1.2012)

2012

C-Print, UltraSecG, Metallrahmen

100 x 130cm

Courtesy Galerie Fahnemann, Berlin

© VBK, Wien, 2013

Marc Quinn (British, b. 1964)

Landslide in the South Tyrol

2009

Oil in canvas

168.5 x 254 x 3cm

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris. Salzburg

Foto: Ulrich Ghezzi

Pipilotti Rist (Swiss, b. 1962)

Sparking of the Domesticated Synapses

2010

Video installation; Projector and Media Player, miscellaneous

Objects, Regal, Quiet

Video: 5:34 min

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Zürich

© The artist, Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine, New York

Foto: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

For some time now, there has been a renaissance of flowers and mushroom themes in fine art. The comprehensive exhibition Flowers & Mushrooms explores the clichées and the various levels of meaning and symbolism of flowers and mushrooms in art. Current social and aesthetic issues are discussed on the basis of a selection of works from the fields of photography, photo-based paintings, video and sculptures/installations.

Today flowers are primarily associated with their decorative function. They also have a symbolic meaning both at weddings, where they represent freshness and fertility, and at funerals, where they represent transitoriness and death. An in-depth exploration of the varied symbolic meanings of flowers in cultural history reveals further levels of meaning, many of which refer to the ambivalence and abysms of human existence. Contemporary art adopts and continues the historical and complex pictorial tradition of flowers and mushrooms by adding new, contemporary perspectives. The exhibition was inspired by the multi-part work series Ohne Titel (Flowers, Mushrooms) by the artist duo Peter Fischli / David Weiss. The Swiss artists have been preoccupied with the role of clichées and common subjects for many years. Different slide projections with a comprehensive series of inkjet prints and Cibachromes included cross-fadings of flower and mushroom motifs.

At the beginning of the exhibition, a historical section shows photographs from the 19th and early 20th century. In particular the new medium of photography developed a special relationship with flower motifs. Photographs of the great variety of different plant and flower species serve as a kind of substitute for the traditional herbarium or as natural models, as “prototypes of art” for ornamental design lessons. From the early beginnings of photography, scientific interest motivated pioneers such as William Henry Fox Talbot or Anna Atkins to capture amazing pictures of plants.

Later on, the affirmative exaggeration of the decorative character of the flower inspired none other than Andy Warhol to take up a simple, photographically reproduced flower motif in his work Flowers (from 1964); through serial repetitions he ironically exaggerated the motif and conferred iconic status on banal everyday objects. Artists such as David LaChapelle and Marc Quinn continue the baroque symbol for opulence with the aggressive colourfulness of their impressively grand flower arrangements, but also emphasise the simultaneously existing threatening moment, when the boundlessness can take on a devouring character.

For some time now, there has been a renaissance of flowers and mushroom themes in fine art. The works of leading “portraitists” of flowers and mushrooms, such as Peter Fischli / David Weiss, David LaChapelle, Marc Quinn, Sylvie Fleury, Nobuyoshi Araki or Carsten Höller, continue the multi-faceted and long pictorial tradition of flowers, which is unparalleled in the history of art. At the same time no other motif is so easily suspected of trivialism. The question arises of how a subject that is frequently accused of being trivial and shallow has been able to gain ground in a field of art that is generally regarded as serious and sophisticated. The picture of a flower is too easily associated with the idea of harmless beauty and the mushroom with cliché-like hallucinogenic states of consciousness. Nevertheless many artists increasingly adopt these motifs, adapt them and find individual ways to put them into the context of socio-critical, feminist, political and media-reflexive art.

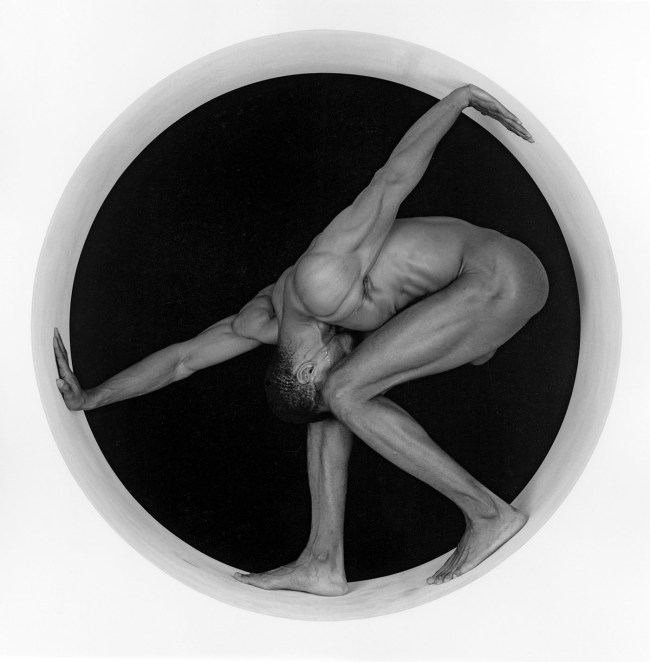

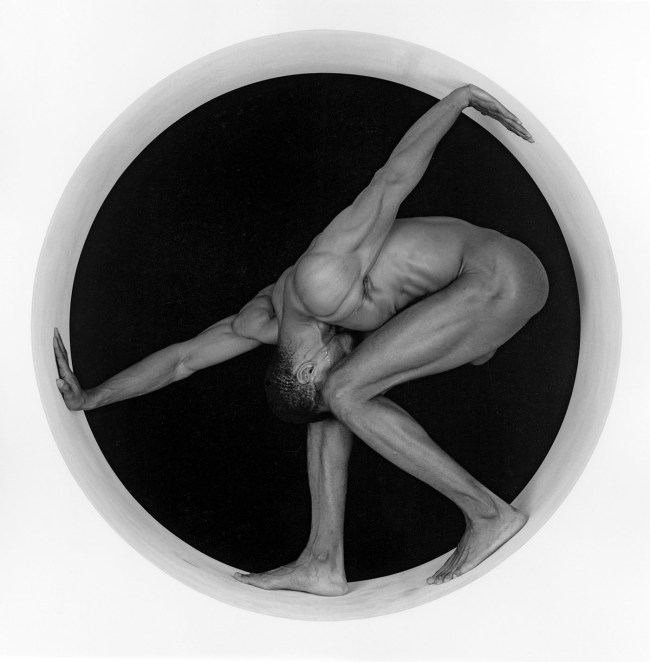

It is only at first glance that David LaChapelle and Marc Quinn continue the baroque symbol for opulence with their impressively grand flower arrangements that reveal a threateningly devouring character upon closer inspection. Female artists such as Vera Lutter, Paloma Navares and Chen Lingyang reflect upon flowers in a specifically female way, using them as a symbol for their own identity-defining sexuality, but also for their vulnerability and exposure and thus elevate the flower to a socio-critical and political level. With almost scientific interest, Andrew Zuckerman and Carsten Höller take an analytical view of the morphological characteristics of flowers and mushrooms in their photographs and installations which create an impressive immediacy. The erotic photographs by Nobuyoshi Araki and Robert Mapplethorpe draw parallels between a blossom and the male and female body and create a field of tension between still life and nude. The wilting flower as a classic symbol of vanity is depicted by Michael Wesely in his long-exposure photographs, which accompany the life of a flower from full bloom to its wilting while emphasising their beauty to the very end. Contrastingly, the monstrous, towering plants of the “desolate” video installations created by Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg are devoid of any loveliness and have a menacing effect. They depict violence and abuse give flowers a particularly irritating and disconcerting touch by breaking with their generally positive connotation.

Flowers and buds symbolise eroticism in general, their appearance creating associations with the female and masculine gender (sexual organs) specifically and thus have a sensual appeal. Imogen Cunningham and Robert Mapplethorpe have a reputation as early forerunners of this sexualised and yet apocalyptic perception of flowers. They both implemented this special perception – erotically charged and aloof at the same time – in their photographs by drawing analogies to the human body in their sculptural treatment of the flower. Female artists such as Vera Lutter, Paloma Navares and Chen Lingyang reflect upon flowers in a specifically female way, using them as a symbol for their own identity-defining sexuality, but also for their vulnerability and exposure and thus elevate the flower to a socio-critical and political level.

Thanatos, or death, is closely related to Eros. The wilting flower as a symbol of vanity is depicted by Michael Wesely in his long-exposure photographs, which accompany the life of a flower from full bloom to its wilting while emphasising their beauty to the very end. The flower monstrosities of the “desolate” video installations by Nathalie Djurberg, which deal with violence and abuse, are devoid of any loveliness and even have a threatening effect.

Both in their natural environment and in cultural history, mushrooms are on the shadow side. Mushrooms are mainly associated with dubious alchemism and witchcraft, are desired and feared as hallucinogenic and have become an integral part of art and literature. Similar to flowers, mushrooms have a long tradition in art history and appear frequently within the context of artistic productions. Sylvie Fleury, for example, controls space with a “forest” of over-dimensional mushrooms, whose surface is covered with car paint, thus increasing their intrinsic character of a foreign body. Their over-dimensional size, and glittering appearance evokes scenes from “Alice in Wonderland”, where the protagonist eats from a mushroom to makes her grow or sink. Carsten Höller, by contrast, explores mushrooms with almost scientific interest and documents their individuality and uniqueness in detailed colour photographs or converts them into larger-than-life-size, large-scale sculptures and display cabinets.

The particular appeal of this exhibition organised by the curators of the MdM SALZBURG lies in the comparison and confrontation of the different levels of meaning of images of flowers and mushrooms and their controversial positions in contemporary arts. The title of the exhibition has been inspired by the series of C-prints by the Swiss artist duo Peter Fischli / David Weiss with the title “Flowers, Mushrooms”. Flowers & Mushrooms presents a selection of important works from the fields of photography, photo-based paintings, video and sculpture/installation art with floral motifs, spanning the time from the early beginnings of photography to the immediate presence. Selected works on loan accentuate the focal points and main themes of the exhibition by raising current social and aesthetic issues and thus allow a closer inspection of the multi-faceted symbolic use of flowers and mushrooms. At the same time, new levels of meaning are opened, referring to the ambivalent and mystical dark side of human existence. The exhibition shows how contemporary art adopts and continues the historical and complex pictorial tradition of flowers and mushrooms by adding new, contemporary perspectives. A historical section with photographs from the 19th century and of Classical modernism complements the exhibition and shows, how photography as a new medium has developed a special relationship with floral motifs.

The exhibition features works by Nobuyoshi Araki, Anna Atkins, Eliška Bartek, Christopher Beane, Karl Blossfeldt, Lou Bonin-Tchimoukoff, Balthasar Burkhard, Giovanni Castell, Georgia Creimer, Imogen Cunningham, Nathalie Djurberg, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Peter Fischli / David Weiss, Sylvie Fleury, Seiichi Furuya, Ernst Haas, Carsten Höller, Judith Huemer, Dieter Huber, Rolf Koppel, August Kotzsch, David LaChapelle, Edwin Hale Lincoln, Chen Lingyang, Vera Lutter, Katharina Malli, Robert Mapplethorpe, Elfriede Mejchar, Moritz Meurer, Paloma Navares, Nam June Paik, Marc Quinn, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Zeger Reyers, Pipilotti Rist, August Sander, Gitte Schäfer, Shirana Shahbazi, Luzia Simons, Thomas Stimm, Robert von Stockert, William Henry Fox Talbot, Diana Thater, Stefan Waibel, Xiao Hui Wang, Andy Warhol, Alois Auer von Welsbach, Michael Wesely, Manfred Willmann, Andrew Zuckerman.

Press release from the Museum der Moderne Salzburg website

Paloma Navares (Spanish, b. 1947)

Vestidas de Sede

2009

C-Print on Diasec

125 x 125cm

Courtesy MAM MARIO MAURONER Contemporary Art, Salzburg-Vienna

© VBK, Wien, 2013

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Flower

1988

Silver gelatin print

71.1 x 68.6cm

© The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, New York

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Thomas

1987

Silver gelatin print

71.1 x 68.6cm

© The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, New York

Luzia Simons (Brazilian, b. 1953)

Stockage 104

2010

Scannogramm

Lightjet Print / Diasec

100 x 100cm

Courtesy ALEXANDER OCHS GALLERIES BERLIN ǀ BEIJING

© VBK, Wien 2013

Katharina Malli

From the series Dead nature

2012

Digtal C-Print

40 x 60cm

KUNSTIMFLUSS; eine Initiative von VERBUND

Flowers & Mushrooms exhibition texts

The title of the exhibition refers to the name of different slide projections and comprehensive photo series created by the Swiss artist duo Peter Fischli / David Weiss, which show cross-fadings of flowers and mushrooms. Fischli / Weiss began with photo series of everyday motifs back in 1987, and ten years later they used 2400 pictures from their extensive archive to make a cross-fading video with a duration of eight hours. Their general aim was to present the entire visual world they had encountered and documented on their excursions or long travels. Ten years later, the seemingly endless impressions of sights and attractions of the old and new world became limited to flowers and mushrooms, whose pictures overlap in double exposures and appear as a kind of hybrid: as newly created “living beings” between the world of flowers, associated in art history with all kinds of christological and erotic symbolism, and the world of mushrooms, which are not plants and are mainly known for their toxicity. Peter Fischli and David Weiss made the representation of flowers and mushrooms, which had mainly been restricted to calendars and trivial photo books respectable and presentable in contemporary visual arts. The time was ripe for this, even though pictures of flowers and mushrooms had experienced a kind of renaissance in contemporary art before: The ongoing interest in artistic productions dealing with different plants and mushrooms seems to confirm this.

Nevertheless the question arises, how the “flower image” which was frequently accused of triviality in the past, has been able to gain ground in sophisticated and serious art. Pictures of flowers could too easily be associated with the idea of harmless beauty and those of mushrooms with cliche-like, hallucinogenic states. For some years, many artists have nevertheless adopted these motifs, adapted them and found individual ways to put them into the context of socio-critical, feminist, political and media-reflexive art.

Many of the artists represented here in this exhibition deliberately continue this multi-faceted tradition which testifies to a respectable history the “flower picture”: Integrated into the context of Christian iconography in late antiquity and the Middle Ages until the Renaissance period, it timidly began to develop an autonomy during the Baroque period as a result of the newly arising scientific interest in the morphology of flowers and the related wish to classify them encyclopaedically. The rise of the “flower image” to a significant motif that appeals to the audience came to a temporary standstill in the 19th century, when it became an empty academic shell. It re-gained importance only during the Art Deco and New Objectivity period and even became a model for some contemporary forms of expression. While flowers have always been used as photographic motif all over the world due to their beauty and their specific shapes, which are frequently associated with human genitals, mushrooms seem to have inspired most artists who used them in their works due to their sculptural potential and possibly their hallucinogenic effect.

Our exhibition wants to present the use of flowers and mushroom in contemporary art photography, slide and video projections, installations, sculptures and photo-based paintings in all its different faces and assign the works to different themes for better understanding, however without clear boundaries between the individual categories. In a kind of art-historical prologue with the Latin title Species Plantarum we want to show, how scientists and artists have dealt with the representation of plants and blossoms and more rarely of mushrooms since the mid-19th century – parallel to the invention of photography – in photographic studies and “still lifes”. Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose shows that even seemingly trivial photographs of a flower or a mushroom viewed with disinterested pleasure can and should no longer be regarded as neutral and is linked with connotations of everyday experience and cultural education. Les Fleurs du Mal focuses on cryptic and unfathomable, abysmal aspects hidden in flower motifs. The works presented in the section Garden of Earthly Delights establish connections between gender, eroticism and sexuality – but also transitoriness and death – and the symbolism of flowers and associations used by many artists in their works. Nature versus artificiality finally heralds human interventions in nature and the wish to control and experiment with nature and the reflection of this development in visual art.

Species Plantarum

The 19th century was marked by social upheavals, which allowed civil society to intervene in many areas, such as politics, humanism and cultural history, but also natural sciences. The publication of Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) Origin of Species (1859) intensified the public interest in forms of nature and increased the significance of natural phenomena. This not only encouraged the scientific curiosity of scientists, but also inspired artists to find new approaches to representing nature.

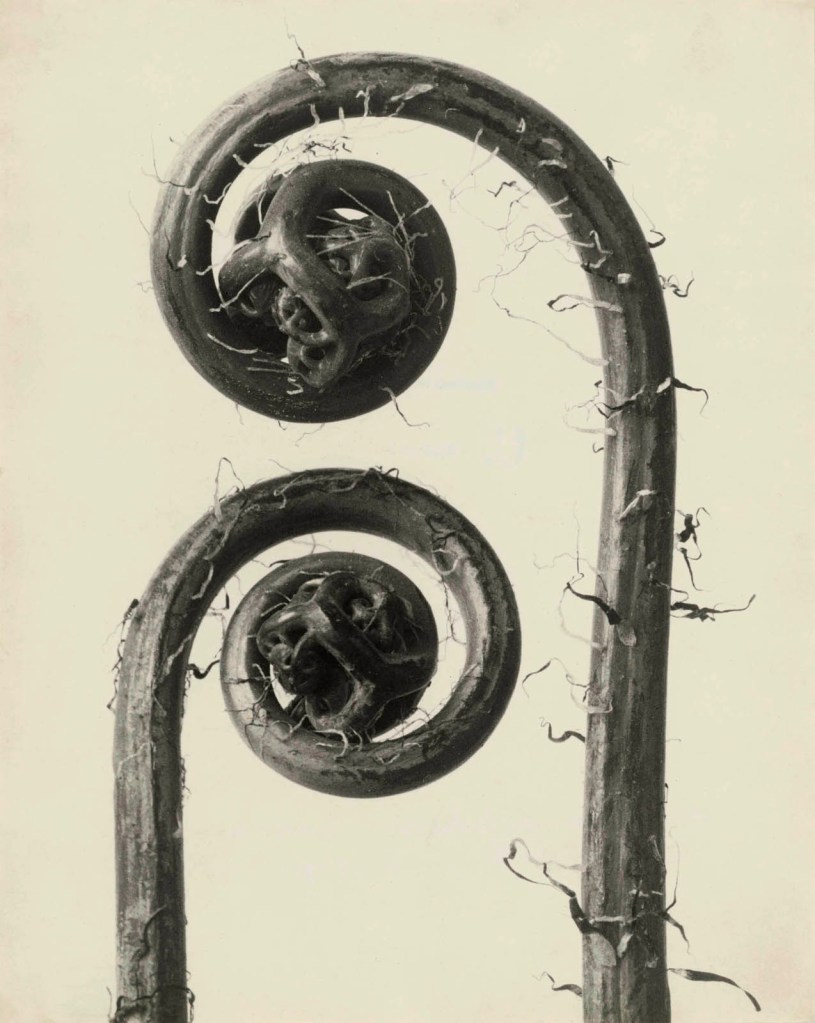

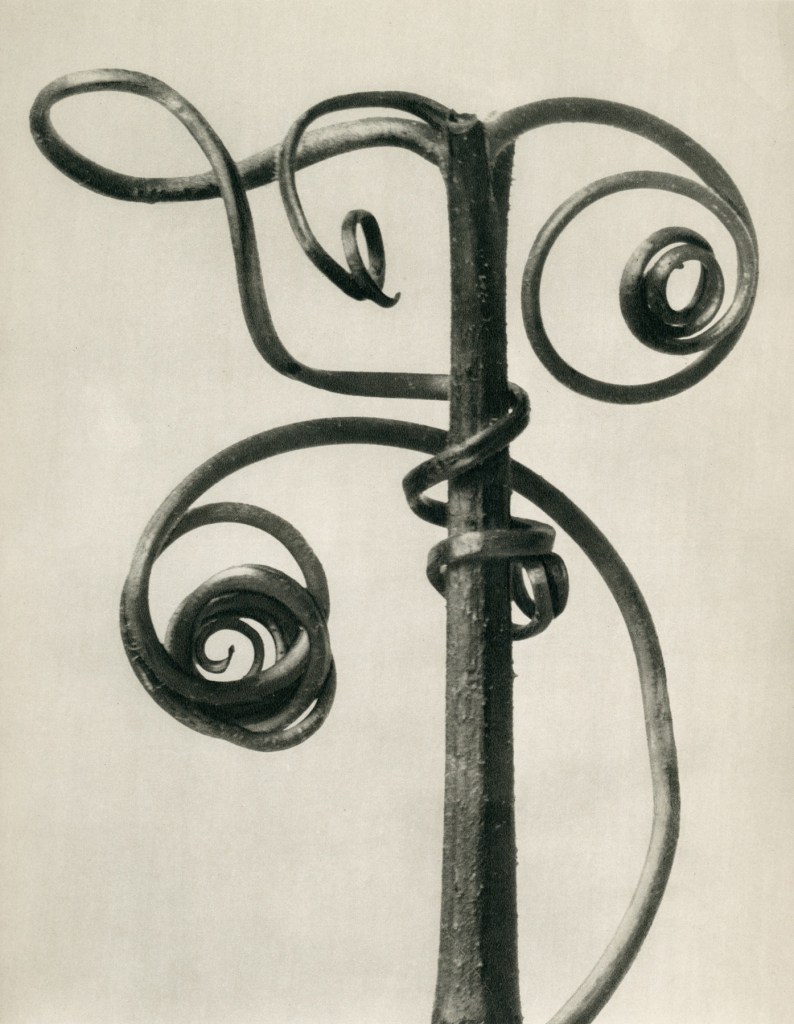

The newly discovered medium of photography, (further) developed out of the desire for an accurate reproduction for scientific purposes and used for various optical and chemical experiments, expanded the range of artistic forms of expression. Artists with an interest in botany eagerly and enthusiastically applied new techniques -such as nature prints, airbrush techniques or photogenetic drawings – and also embraced the new medium and instantly recognised its potential, inspired by pioneers such as Anna Atkins (1799-1871) and William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877). Early photographic experiments found their expression in the floral Art Nouveau style and in teaching concepts and teaching aids. The most famous collection of designs was Urformen der Kunst / Art Forms in Nature (1928) by Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932). His photographs became incunabula for the representation of plant-derived forms using the precise stylistic means of New Objectivity.

The artistic impulses of the following decades contributed to an exploration of nature through alternative cognitive forms. Photography detached itself from the primacy of representation, dominated by form and surface stimuli, and turned towards visual stimuli for the human power of imagination.

Anna Atkins

The botanist and illustrator Anna Atkins (1799-1871) is regarded as pioneer of photography. Her father, the British chemist, mineralogist and zoologist John George Children (1777-1852) aroused her passion for natural sciences. At a time when there was no scientific education for women, ladies from noble families had to content themselves with being “amateur helpers” for their fathers and husbands and worked in the background, compiling herbariums and making drawings. Through her friendship with the physicist John Herschel (1792-1871), who closely collaborated with William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877), Atkins became familiar with cyanotype, a printing process invented by Herschel, and began to use this new photographic printing process for mapping scientific samples. The first photographic herbarium was published under the title Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions between 1843 and 1854, comprising 12 issues with 389 illustrations. The photograms, which get their characteristic blue colour on the parts of the paper exposed to light from the use of an iron complex, produce particularly accurate representations of the plants. Their special allure is their diaphanous appearance. Anna Atkins’s works, which were forgotten for a long time, are today regarded as a milestone in the history of scientific and photographic illustration and have contributed to the rediscovery of cyanotype as printing technique.

Alois Auer von Welsbach

Alois Auer von Welsbach (1813-1869) was an Austrian printer, inventor and illustrator specialising in books on botany. He was head of the “k.u.k. Hof-und Staatsdruckerei” printing company founded in 1804 in Vienna and developed it into a large-scale enterprise that offered all state-of-the-art printing techniques and methods of representation known at that time. The printing company became renowned for its nature prints developed and perfected by Auer in cooperation with Andreas Worring. Nature printing is a printing process that uses natural objects to produce an image. Dried or pressed objects are placed between a plate of steel and another of lead and drawn through a pair of zinc rollers under considerable pressure to produce in impression in the leaden plate. The printing plate is produced by electrotyping, also called galvanoplasty. Gravure printing is used for plants. The use of several colours in one printing cycle produced polychrome and particularly “authentic” prints. Until today no printing process has been able to surpass the high level of detail of this technique. For Auer nature printing was as important as photography, and he published books to promote this printing process. “Auers Naturselbstdruck” was patented in 1852 and released for general use in 1853. Over the centuries nature printing has been used for decorating everyday objects and for illustrations on substrates such as papyrus, parchment and paper.

Robert von Stockert

In the 1890s a small community of aristocrats and upper class people with an interest in arts established the “Club der Amateur-Photographen” (Club of Amateur Photographers) – later renamed “Wiener Kamera-Club”. Their photographs were largely influenced by painting. Members of the club include many famous names such as Heinrich Kühn (1866-1944), but also less famous contemporaries such as Carl Brandis (active around 1885-1900), Franz Holluber (1858-1942) or Robert von Stockert (1848-1918), who specialised in flower still lifes. For von Stockert, nature was an interesting theme for various reasons: He had the ambition to contribute to the “development of photographic art”, benefited from his own gardens and the decorative talent of his daughters and used his photographs for book illustrations. He regularly published his experience in illustrated supplements to the association’s publication “Wiener Photographische Blätter”. His pictorial vocabulary ranges from purely decorative flower arrangements to sophisticated still lifes. To convey the colourfulness of his motifs, von Stockert experimented with various techniques, both with photographic techniques, like the use of various colour filters and sensitive plates, and with reproduction techniques. His favourite printing techniques include platinum print, which provides a particularly rich and intensive range of grey nuances. For colour reproductions he used the new multicolour collotype process.

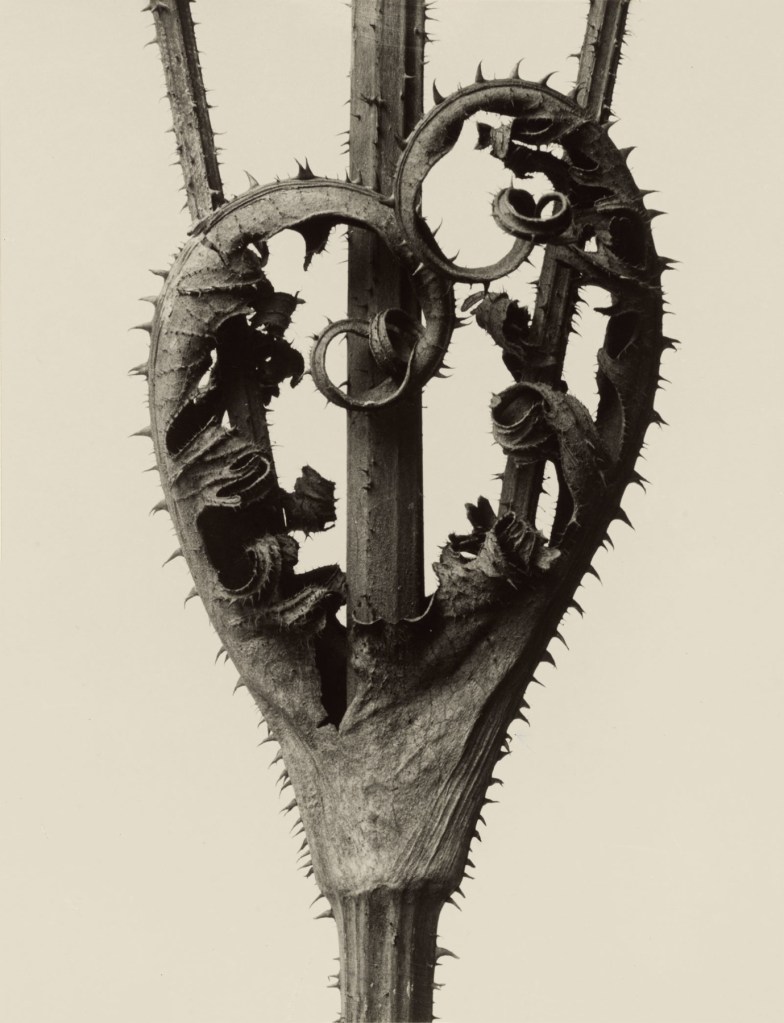

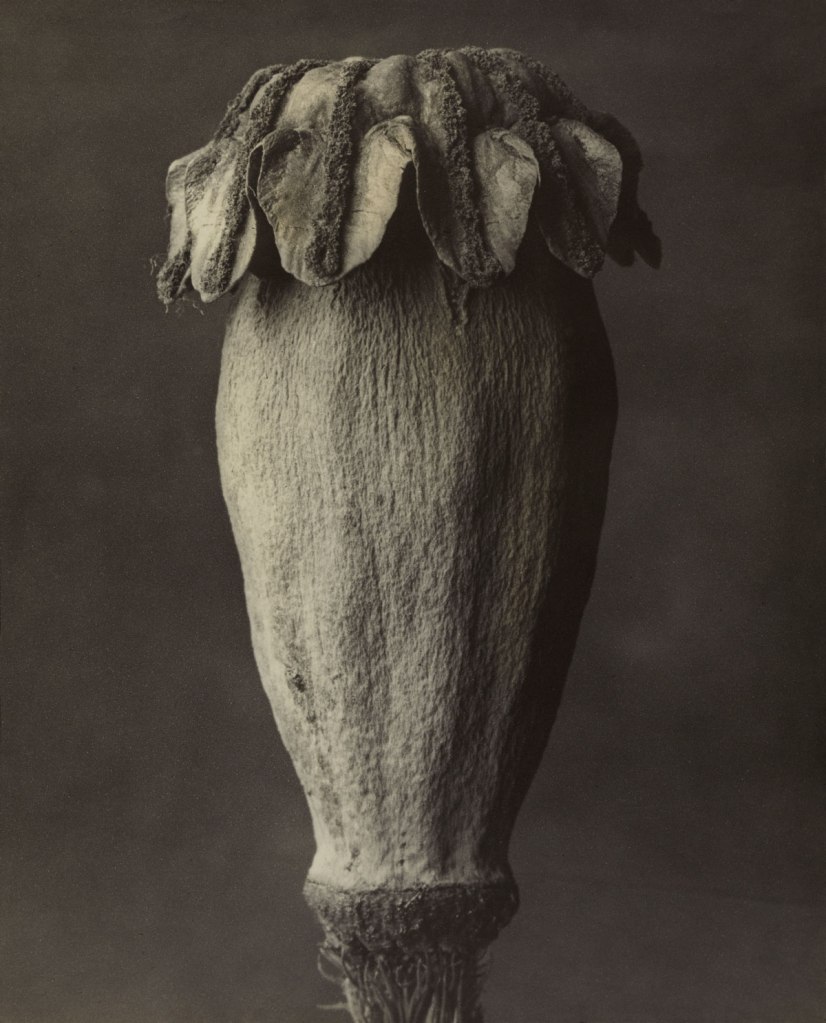

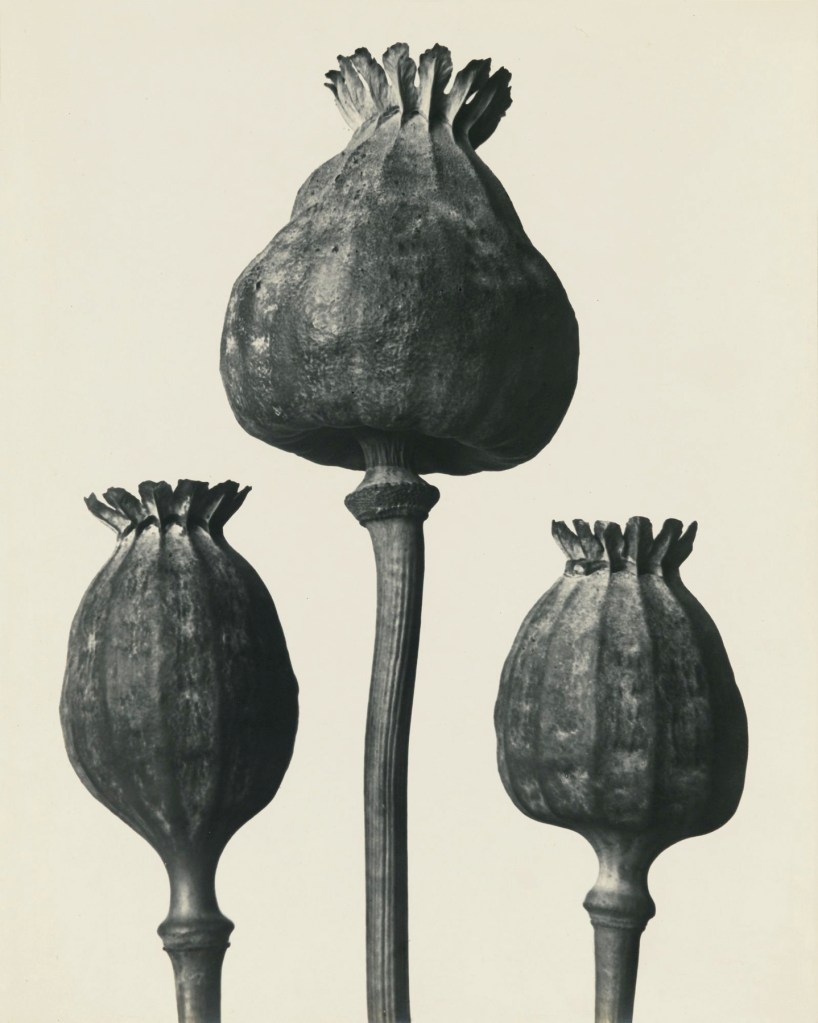

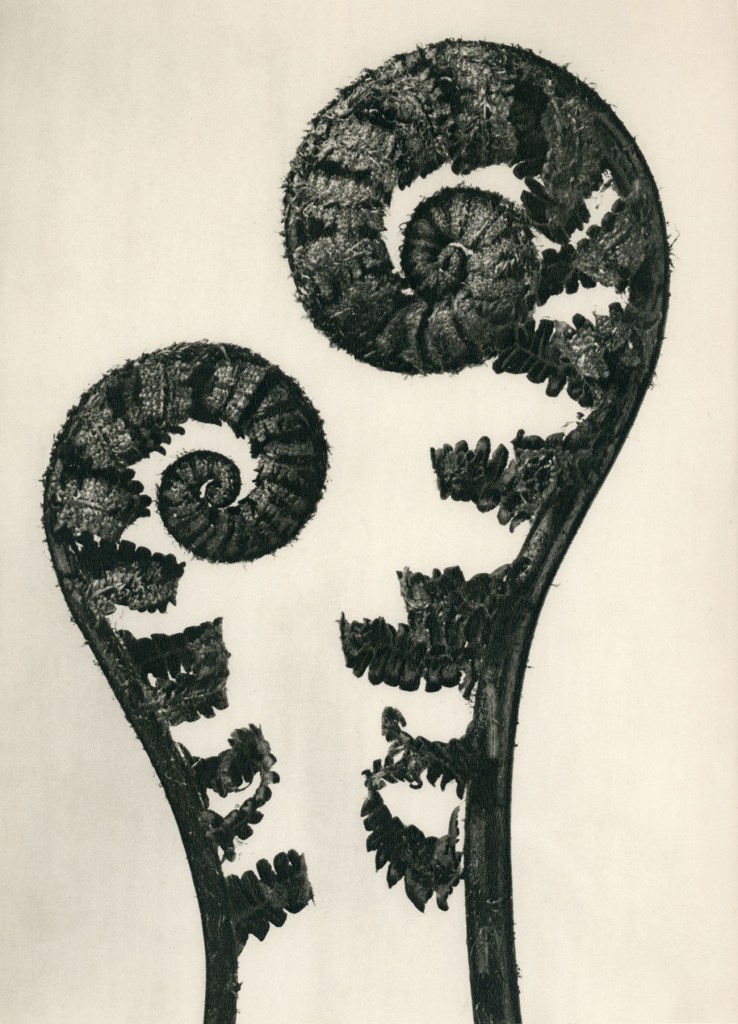

Karl Blossfeldt

The plant photographs of German photographer Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932) are milestones in the transitions from the playfully stylising Art Nouveau style to the unemotional, cool spirit of “New Objectivity” and have become incunabula of the history of photography. His motivation behind his imagery and motifs is rooted in his education as sculptor and modeller in an art foundry. At the Kunstgewerbeschule in Berlin – today the Universität der Künste (University of the Arts) – he collaborated in a project of his art teacher Moritz Meurer and compiled teaching aids for ornamental design. As lecturer for “modelling from plants” he received an official assignment in 1889 which provided further impetus for the production of illustrative material. Blossfeldt became famous for his book Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature) (1928); another volume – Wundergarten der Natur (Magic Garden of Nature). A sequel to Art Forms in Nature was published in 1932. The photographs here on display are a small selection from a collection of 6,000 pictures, whose clarity, rich contrast and acutance testify to his technical precision, craftsmanship and passion for photography and teaching. Graphic details, structures, forms and surfaces are emphasised by the targeted selection of details, magnified 2 to 45 times. Blossfeldt achieves a sculptural effect by using a monochrome, light background and thus liberates the plants from their natural context.

Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose

What Getrude Stein wrote in the mid-1920s and later became so influential and was often misunderstood, can be used as a motto for the works here on display, but also to point out ironically that the use of flower motifs is trivial only at first sight.

Like portraits or interieurs, flower pictures are part of the repertoire of art history. Even more so: No living being is used more frequently in symbolism than the flower, and few subjects are as complex as the history of the flower motif. In the past, flower still lifes were used to convey encrypted and symbolic messages, most of which are lost to us today. We no longer know the symbolic meaning of the individual flowers or their arrangements. Many artists have used floral themes in their work, as a reaction to the apparent triviality of the century-old flower motif, and have so continued this traditional theme. Today the flower motif has become the basis for new reflections and observations.

The oldest photographers whose works are here on display – Ernst Haas and Balthasar Burkhard – already liberated the flower from its temporal and spatial context and focused on depicting the flower not as a decorative still-life at the height of its beauty, but as a fragile plant subjected to instability and transformation. The American photographer Andrew Zuckerman portrays crystal-clear, razor-sharp images of different blossoms with an accurate eye, capturing the fine details of their surface structure and colour transitions. His strict staging abandons the common understanding of flowers and releases them from their context. As a result, Zuckerman’s pictures assume an almost cool, abstract quality.

Christopher Beane shares a similar love for details. His close-up pictures of petals convey sensuousness and opulence. As a staging photographer he completely restrains himself and entirely leaves the stage to his protagonists, allowing them to unfold their full beauty in exciting, suspenseful intersections, contours and curves. The scannograms by Luzia Simons show an opulence and splendour that reminds us of traditional Dutch still lifes of flowers. The large-format photographs are thoughtful reflections on the proud, but also tragic role of the tulip in the early 17th century Netherlands in connection with the “tulip mania”, which is generally considered the first recorded speculation bubble. In Giovanni Castelli’s photographs, flowers appear as mysterious plants, monumental and unreal at the same time. The artist finds his motifs in nocturnal parks, capturing close-ups of colourful flowers against a jet-black sky. The result are eerily beautiful flower portraits which seem to be from another world and elegantly refute our conventional visual concepts.

Carsten Höller

b. 1961 in Brussels/Belgium, lives and works in Stockholm / Sweden.

Carsten Höller, who has a doctorate in agricultural science, works at the frontier between art and natural science. Dissatisfied with the restrictive structures of the academic world, he turned his back on it and chose the path of greatest-possible openness: he became an artist. “As an artist I do not have to submit to any formalistic constraints and can develop things as far as I think makes sense in a particular framework, without always having to undergo specialist training in the relevant fields.” Höller has not abandoned his first life, but combines the two disciplines, which appear to be so different from one another, in a highly idiosyncratic and humorous manner. He creates bizarre hybrid forms from a variety of types of mushrooms. He either grows them to a threatening height or exhibits them, like jewels in a glass cabinet, in orderly rows as though in a natural-history museum. Fly agaric is always present. Höller explores this mushroom and its hallucinogenic effects in great detail. In this context he is on the trail of a mysterious potion called soma, which is thought to have been made of fly agaric and was used for ritual purposes as early as the second century BC. Drinking it is said to impart good fortune and riches, the power to be victorious, and awareness and access to the divine sphere.

Hans Peter Feldmann

b. 1941 in Düsseldorf/Germany, lives and works in Düsseldorf.

The large-format photographs of flowers by Hans-Peter Feldmann are at first glance reminiscent of the floral postcards of the 1950s: we see flowers popular at the time, such as roses and lilies, in close-up in front of a neutral, colourful background. The colour aesthetic of flower and background, too, corresponds to the time. Clear and uncompromising, the blossoms present themselves to the viewer in their full glory, while simultaneously appearing distant and artificial. In this respect they do not match today’s ideas of the bourgeois idyll. The magnification makes the kitschy look sublime. The blossom appears like a fetish behind glass, frozen for the next millennium. Feldmann has always been interested in the everyday and the banal. He lives his passion for collecting at flea markets and in his own shop of knick-knacks. He often works with found materials such as postcards and newspaper cuttings. The photographs shown here are not enlargements of these collected objects, however. They were created by Feldmann, based on the aesthetic of the small-format postcards of which they are ironic imitations. Feldmann’s artistic concept includes the practice of not dating and not signing his works: “Bakers don’t sign their rolls either, do they? Art has to taste and smell, one has to be able to experience it.” For Feldmann, one of the first concept artists, the works of art are already there. He considers it to be his job to find them. They should not lose their vitality despite the transformation.

Luzia Simons

b. 1953 in Quixadá/Brazil, lives and works in Stuttgart and Berlin / Germany.

The tulip is, in the eyes of Luzia Simons, an element that connects cultures, and a symbol of transcultural identity. As a nomad among flowers, the tulip was brought to Europe from Asia, and connects the Orient and the Occident. It is at home both here and there, and has established itself as a virtu despite having been transferred via several different cultures. The tulip conquered the Netherlands in the late sixteenth century, and tulips featuring special colours and patterns commanded exorbitant prices on the market in a rapidly expanding “tulip mania”. Speculation with tulip bulbs led to a speculative bubble. The bubble burst in 1637, with far-reaching social and economic consequences. Simons sets the scene for the majestic and simultaneously tragic character of the tulip, as well as for its long-standing traditions, in her series entitled Stockage. The artist stages the flowers in large-format arrangements in which they surge towards the viewer in bright colours out of a neutral darkness, revealing their beauty and fugacity in sharp focus. Both through the inescapable vanitas concept and in its painterly effect Simons’s oeuvre is reminiscent of Baroque still lifes. Paradoxically, Simons makes use of a very modern method to generate the images, however: the flowers are “read” by a scanner before they are printed using a carbon-printing process, and finally they unfold their vibrant depth effect behind acrylic glass.

Peter Fischli / David Weiss

b. 1952 in Zurich/Switzerland, lives in Zurich / b. 1946 in Zurich, d. 2012 in Zurich.

The Swiss artist duo Fischli / Weiss began work in 1979 and was highly successful in the spheres of film, photography, sculpture, art books and video installations. Cryptic and playful, often seen as though through the eyes of children, they re-arranged art and the everyday in their work. Their subtly ironic works, which often appear to be imbued with subversive nonsense messages, received numerous international awards. From kinetic experimental arrangements using everyday objects to interpersonal re-enactments using sausage leftovers: Fischli / Weiss transformed the apparently banal and the absurd into art. For this reason the flower motif also entered the work of Fischli / Weiss from 1997 onwards. The Flowers series (1997-1998) exists in two presentation forms: colour prints, and a double-slide projection. It shows a chaotic view of nature, as though from an ant’s perspective, using a hallucinatory and intensely colourful technique of superimposition. The arrangement of double and quadruple exposures and the resulting translucent layering of close-ups of flowers, mushrooms, snails and many other things creates the impression of a nature that is unordered and exuberant, unreal and simultaneously beautiful. This playful approach to reality and appearance, the conceptual claim of the visualisation of the world – in this case nature, which is just “there” and is in no need of legitimisation in order to be shown in the context of art – and the interest in the banal, in combination with a more serious artistic interest, constitutes the framework that encompasses the entire oeuvre of die Fischli / Weiss.

Les Fleurs du Mal. Reality and Appearance

In his poetry collection Les Fleurs du Mal (1857-1868) the French writer Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) painted a picture of a pessimistic modern city dweller that is characterised by despondency, anger and rebellion against all conformities. Man is torn between Christian morality, the good ideal and virtuousness on the one hand and the reprehensible and yet appealing fascination with the evil and ugly on the other hand, and forced to establish a new position for himself continuously.

What the artists represented in this part of the exhibition and Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal have in common is their questioning of conventional views on beauty and morality, symbolised by flowers which are generally regarded as beautiful, and the deliberate discussion of the transience of beauty as well as socio-political principles and ethics. In particular the vanity theme is directly related to the “Flowers of Evil”, as it belies the human desire for eternal beauty and eternal life. Bourgeois decadence in the form of Baudelaire’s positive re-interpretation is no longer a common term today, but has a stronger presence than ever in the classic meaning of the decline of a social system, in particular with reference to the frequently heralded fall of capitalism. In the 21st century artists approach this subject in a differentiated way. Works closely related to traditional genres of art history, such as the still life, exist side by side with current series of works dealing with the concept of time as such, for example by intensely visualising the blossoming and withering of flowers or linking this with socio-political issues. The delightful moment of the pictures and materials is sometimes opposed to the subject matter or explicitly border-crossing contents.

Marc Quinn

b. 1964 in London/Great Britain, lives and works in London.

Marc Quinn’s 2009 paintings Landslide in the South Tyrol and Aleppo Shore from 2010 are based on photographs that he took of model landscapes he himself had composed. To this end he arranged lush and colourful plant ensembles in his studio. Drawing on Baroque bouquets, which are artificial creations and consciously unnatural in their composition, Quinn negates the passing of the seasons and combines plants that do not blossom at the same time as each other. His enormous square compositions confront viewers with paradisiacal gardens bursting with life, allowing viewers to immerse themselves in an apparently idyllic, magical world. Closer inspection reveals that the white surface to which the luminosity is owed is in fact a snowfield, and this causes consternation. The first impression of cheerful colourfulness and light-heartedness dissipates and the scenery that is now perceived as artificial suddenly feels threatening in a very subtle way. In the midst of life we are surrounded by death! The viewer is surrounded not by a lively garden landscape, but by an arrangement of frozen, dead plants. The unnatural brightness of the colours, which knows no soft nuances, points to the artificially generated world, and reveals the difference between beautiful appearances and reality. One senses that critique of civilisation is a driving force: the artist exposes humankind’s reckless approach to nature because we are willing to sacrifice nature for the sake of its perfect beauty.

Eliška Bartek

b. 1950 in Nov Jičín/former Czechoslovakia, lives and works in Berlin/Germany and Lucerne / Switzerland.

For the series Und Abends blüht die Moldau Eliška Bartek uses highly sensitive film that blurs the contours while simultaneously making details as visible as though they are being viewed through a microscope. As a result the surfaces of the flower petals appear exquisitely delicate and fragile. This feeling corresponds to the traditional symbolism of flowers. They are viewed as the ultimate symbols of the beauty of the moment, which already contains the seeds of transience. The flowers come from a Berlin wholesaler or are cut fresh by the owner of a botanical garden in Pila, a small village in Ticino. Bartek exposes them to particular light influences and in this way alters their colours. In addition to the extreme magnification and closely framed composition of the pictorial subjects it is this intense colourfulness in particular, further enhanced by the dark background and dramatically heightened by unusual light and shadow effects, that creates an extraordinary vitality and releases the pictorial subject from its static nature. For a short time the photo artist breathes an intoxicating beauty into the blossoms, for which the flowers pay the ultimate price: the extreme light burns the delicate petals and destroys the natural splendour. Bartek’s subtle play with reality and appearance, or with artificiality and naturalness, also points to the fallibility of our perception.

Vera Lutter

b. 1960 in Kaiserslautern/Germany, lives and works in New York / USA.

With the project Samar Hussein Vera Lutter reveals herself to be a socio-critical artist who rescues the civilian victims of the Iraq war from oblivion and creates a memorial to them. More than 120,000 civilians have been killed since the invasion by the American army in March 2003. They are referred to in military jargon as “collateral damage” – an appalling word that downplays the suffering for which it stands. The artist has gathered the names and dates for her work of art from the Iraq Body Count Project. The biggest publicly accessible database of this kind worldwide, it records the civilians who have lost their lives in military and paramilitary campaigns, and documents the collapse of public safety following the invasion. Lutter uses the image of a budding, blossoming and finally wilted and withered hibiscus blossom as a metaphor for the human life cycle. The artist sees analogies between human life with its beauty and fullness, as well as its vulnerability and destructibility, on the one hand, and the tones of this flower, reminiscent of the colour of flesh, and the sensuous shape of its blossom, on the other hand. The names of the dead are superimposed on the printed and projected photographs in chronological order according to the date of death. The first picture is named after Samar Hussein. It is for this 13-year-old girl, the first civilian victim to have been recorded in the database, that the art project as a whole, Vera Lutter’s remarkably poetic and touching elegy for the senseless casualties of war, is named.

Paloma Navares

b. 1947 in Burgos/Spain, lives and works in Madrid and Alicante / Spain.

Paloma Navares’s oeuvre spans the fields of photography, sculpture, installation and performance, and explores historical female positions in our society. Navares, who suffers from a rare eye condition that will eventually lead to the loss of her eyesight, employs her memory, which she refers to as her “inner eye”, as an artistic device. The multimedia artist uses a poetical pictorial language that aims to draw the viewer’s attention in a delicate and subtle way to existential human questions: might putative mistakes or what society judges to be incapacity lead to recognition after all? The photographs of delicate orchid blossoms tell of the fates of women, and are in some respects symbolic. They stand, for example, for Meerabai, a late-fourteenth-century princess from northern India who wrote love songs and laments, and who, as a devotee of Krishna, vehemently opposed marriage. The pressure exerted on her by society at court forced her to commit suicide by drinking from a poisoned cup. Female Korean entertainers, known as kisaeng, were similarly despised and judged by society for their nonconformity. Navares’s depictions of flowers are homages to great female poets of past eras whose lyrical works were ignored and who, in the face of the contempt with which society treated them, chose to die by their own hands. The images represent a plea for justice and self-determination, and simultaneously stand for grace, strength and beauty.

Garden of Earthly Delights

Flowers and blossoms have always held a great fascination for man and are symbolically and culturally linked with love, beauty, youth and sensuality. Opulent flowers are thus instinctively associated with eroticism and seduction, but also inevitably with the aspect of transitoriness. From a biological point of view, the attraction of flowers is due to their signal effect for the purpose of pollination and thus reproduction and survival of a plant species. Not only poems use flowers as metaphor for human desire; the flower as analogy for man and corporeality is also found in fine arts. Artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe, Nobuyoshi Araki and Rolf Koppel combine nudes with floral still lifes and both in form and context refer to the sensual analogies to the erotic desires of man. Robert Mapplethorpe has made the most explicit comments on the relationship between flowers – in particular blossoms with strongly emphasised seeds such as the calla or anthuria – and the phallus. Mapplethorpe once said that his way of photographing a flower does not differ significantly from his way of photographing male genitals. The natural scientist Carl von Linné (1707-1778), who established the basis for modern botanical and zoological classifications, commented two centuries ago on the relationship between the corporeality of plants, animals and man. “We look at the genitals of plants with pleasure, those of animals with revulsion and our own with wondrous thoughts.” In his writings he poses the question, who is aware that the flowers a man gives to the woman he adores are “cut-off genitals of higher plants” and that the floral splendour must be regarded as “sexual intercourse of plants”? Within the context of cultural history, plants have been used until today as a symbol for the sexuality of man which is still a taboo.

Chen Lingyang

b. 1975 in Zhejiang province/China, lives and works in Beijing / China.

The subject of Chen Lingyang’s twelve-part series of photographs Twelve Flower Months is the artist’s monthly cycle, which is associated with twelve different flowers. The viewer sees twelve geometric formats that correspond to traditional Chinese window and door shapes. They feature reflections of Chen Lingyang’s vagina, and the menstrual blood that drips from it. The shape of the mirror, too, varies from month to month. The viewer is supposed to feel disturbed by the juxtaposition of flowers – which are the ideal expression of the beauty of nature – and the bleeding genitals. Looking at the mirror, a Western symbol of flirtatiousness and beauty, viewers simultaneously become secret viewers of an intimate depiction. The apparent contrast also reveals unusual similarities, however: Chen Lingyang shows two natural cycles of growth and decay. The artist herself has commented on this work that “in traditional Chinese culture there is the idea of the person who lives in harmony with nature. … To me, ‘nature’ refers most importantly to the laws and rhythms of the universe. And these laws and rhythms are connected to cycles. It is easy for a woman to observe this from monthly physiological and psychological changes.”

Nature vs. artificiality

“Planting means to dig holes to force nature to become unnatural (cultural). […] Owing to the gesture of planting man has lived in an artificial world since the Neolithic period”, the media philosopher and communication scientist Vilém Flusser (1920-1991) once said. In this way he descriptively refers to the general circumstance that we can no longer view nature as something “given”, but as something that is “man-made” and constructed and controlled by man. Accordingly, culture has monopolised nature and its original autonomy to a large extent.

The main purpose of fine arts as a cultural manifestation is not only aesthetic edification. Artists, in particular modern and contemporary artists, also serve as introspective seismographs for development processes of civilisation. Their thinking, designs and creations bring about a change of perspective that goes beyond conventional acceptance and reception and thus refers to phenomena that inspire the viewer to reflect and take a closer look. The preoccupation with flower and mushroom motifs also has to be understood in this context. Primarily decorative and trivial at first glance, their meta levels contain far-reaching statements.

The installation of the Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist explores socially standardised patterns of behaviour of civilised man. Rist makes these patterns tangible in her works by depicting the way people deal with artfully arranged flower decorations. In a comparable, yet differing way Gitte Schäfer explores nature and its “domestic use” in her flower wall. About three hundred small flower vases with an artistically kitschy design are affixed to a wall of diagonally placed mirrored tiles and filled by the artist with cut flowers in the form of a symmetrical picture.

The transient splendour of the flower arrangements symbolises earthly transitoriness and were a characteristic feature of 17th century Baroque still lifes. The Italian term for this category of painting natura morta – also alludes to the notion of vanity. In her four-part work series with the same title, the Austrian artist Katharina Malli shows close-up coloured pictures of crops and ornamental plants against a neutral white background, whose aesthetics deliberately quote the documentary style of Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932). Upon closer inspection, they are industrially produced artificial flowers. As perverted products of civilisation they represent this dead nature and at the same time symbolise the notion of immortality. Dieter Huber’s works also focus on artificially generated nature and play with the wishful thought of potential immortality. In his work series he presents apparently “documentary” pictures of plant hybrids that herald a “brave new world”. The works by Nam June Paik and Zeger Reyers create a concrete connection between nature and technology. The instruments used, such as TV sets and record players, symbolically refer to social progress and are an expression of human inventiveness. They emphasize “manmade” things, juxtapose them with naturally occurring objects and thus describe them in relation to one another.

Andy Warhol

b. 1928 in Pittsburgh/USA, d. 1987 in New York / USA.

By the second half of the twentieth century the flower as an artistic motif had become insignificant. It had become overburdened with the general suspicion of triviality and kitsch. However, Pop Art, which took a deliberate interest in the world of trivial imagery, immersed itself in this subject. Andy Warhol’s Flowers are exemplary of the approach of Pop Art artists. Warhol based his flowers on a folded insert in the June 1964 issue of Modern Photography magazine, a reproduction of a colour photograph of seven hibiscus blossoms. The photograph had been taken by the editor in chief, Patricia Caulfield, and was included as an illustration accompanying an article about a Kodak colour processor. Warhol cropped the photograph to alter the pictorial format, number and arrangement of the blossoms. Numerous variations of what was now a square image were then produced using the screen-printing process, differing from one another in colour and size. In total, more than 500 pictures of flowers must have been produced in this way. The Flowers appear to float in a diffuse space, detached from the background and unconnected to their stalks and leaves. In some versions the blossoms and the pictorial ground are painted by hand in DayGlo colours, further emphasising this impression. Warhol presented the prints in such a way that they covered entire gallery walls as though they were wallpaper. In this way he succinctly demonstrated the plant’s natural potential for rank growth as well as its technical reproducibility as a decorative mass subject.

Dieter Huber

b. 1962 in Schladming/Austria, lives and works in Vienna and Salzburg / Austria.

Since as early as 1986 Dieter Huber has worked with photography that is optimised and altered using computer technology. The three works from the KLONES series, which were executed from 1994 onwards and thus explored genetic engineering and manipulation at a very early date, are doubtless among the pioneering works in computer-generated images. Huber commented on them that “the construction of a world that could be freely disposed of in all respects according to one’s will and imagination was still considered highly vexing at the time.” The three plant studies in the exhibition are – at first glance – razor-sharp photographs of flowers, each before a black background. Well-known types of flowers such as tulips, carnations, narcissuses, daffodils, roses and lilies are reminiscent of a grandmother’s garden. Closer inspection causes consternation, however: various types of flowers grow out of the same greenery, rose stalks are crowned by lily blossoms, and daffodils, lilies and tulips all grow out of the stem of a trumpet flower. Artificially created, impossible-looking crossings have long since found entrance into our real world. Almost all livestock breeds and crop plants used in agriculture were developed through decade-long crossing. Perhaps the surreal floral worlds of Dieter Huber will really exist one day?

Christopher Beane (American, b. 1967)

Study of fungus

2004

From the Farm House series

C-Print

60 x 50cm

Courtesy of the artist

Lou Bonin-Tchimoukoff (French, 1906-1979)

Rayograph #35 – #75

Paris, 1928

Gelatin silver print

23.8 x 17.8cm

Courtesy Galerie Johannes Faber, Wien

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976)

Two Callas

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

Estate Prints, 2013

21.5 x 17cm

Austrian Gallery, Museum of Moderne Salzburg

The Imogen Cunningham Trust, 2013

David LaChapelle (American, b. 1963)

Late Summer

2008-2011

C-Print

152 x 110cm

Courtesy of the Artist ROBILANT + VOENA, London – Milan

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Mönchsberg 32

5020 Salzburg, Austria

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday:10.00am – 6.00pm

Wednesday: 10.00am – 8.00pm

Monday: closed

Museum der Moderne Salzburg website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

0.000000

0.000000

You must be logged in to post a comment.