November 2016

Their Royal Highnesses, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, May 1901

National Library of Australia

Souvenir card of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York with moveable ribbon with printed numbers

I have spent hours digitally cleaning these stereocards that I borrowed from my friend Ellie Young and undertaking the research for this posting. And the hours were well worth it. These 3D photographs really give you a feeling of what it would have been like to live in Australia in the first decade of the 20th century, the spectacle of the country. I also love the colour postcards, with their depictions of kangaroos and Australia surrounded by the red of China and the United States – vulnerable and all on her own!

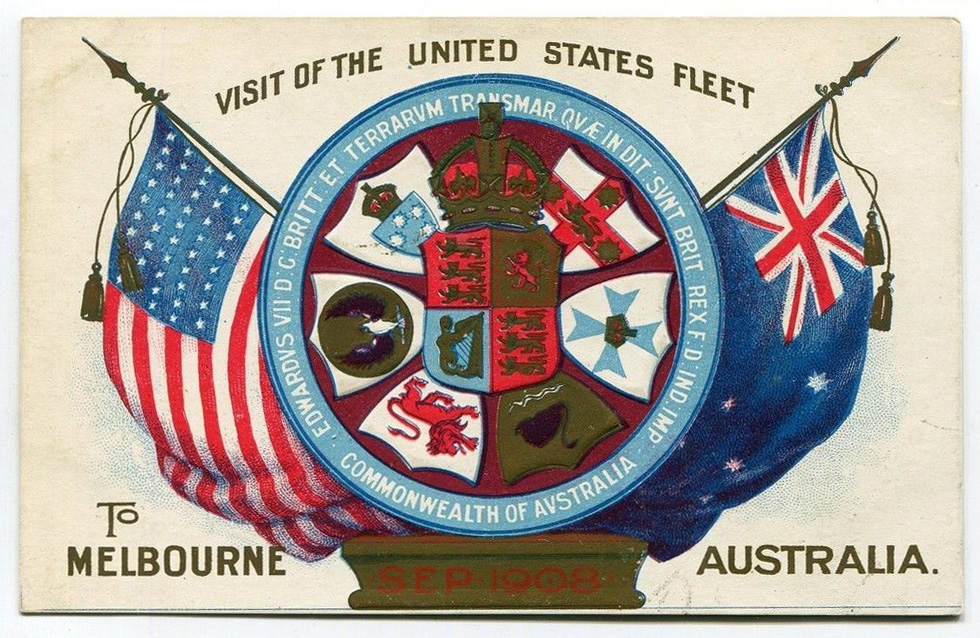

George Rose (1861-1942), was a Melbourne photographer started his photographic career around 1880 producing three-dimensional images. He called his business ‘The Rose Stereograph Company’. He toured the world with his 3-D camera, producing stereographs for the home and overseas markets. Most notable in this posting are the stereocards of the visit of the American Fleet, also known as the Great White Fleet, to Australia in 1908. The visit included the U.S.S. Ohio, U.S.S. Wisconsin, U.S.S. Louisiana, U.S.S. Kansas, U.S.S. Vermont, U.S.S. Kearsarge and U.S.S. Kentucky amongst others. The sixteen warships were painted white to denote peace. The flagship of the fleet was the U.S.S. Connecticut. As detailed below, the visit caused quite a stir in the relationship between nascent Australian nationalism and the mother country Great Britain, as no British battleship, let alone a modern fleet, had ever entered Australasian waters.

In these stereocards it is interesting to observe:

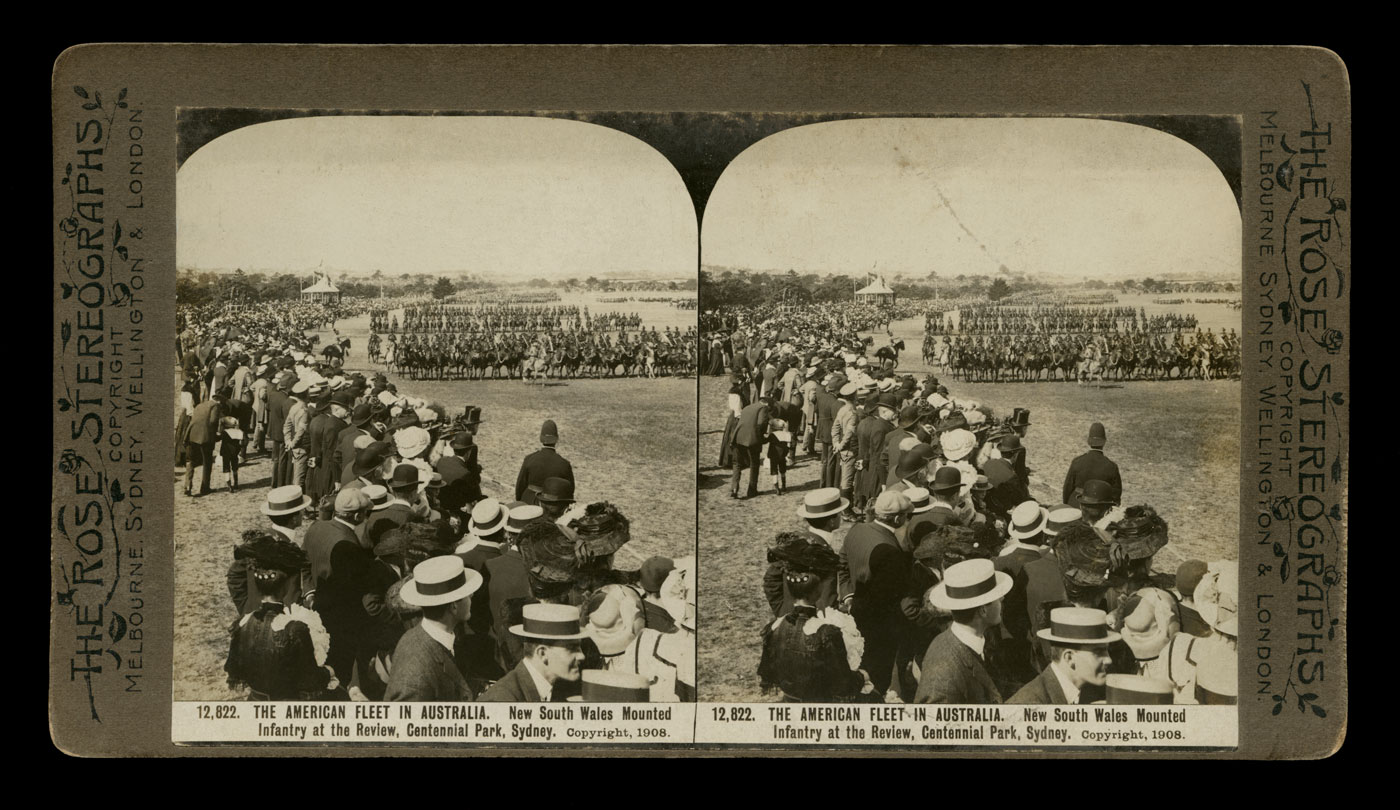

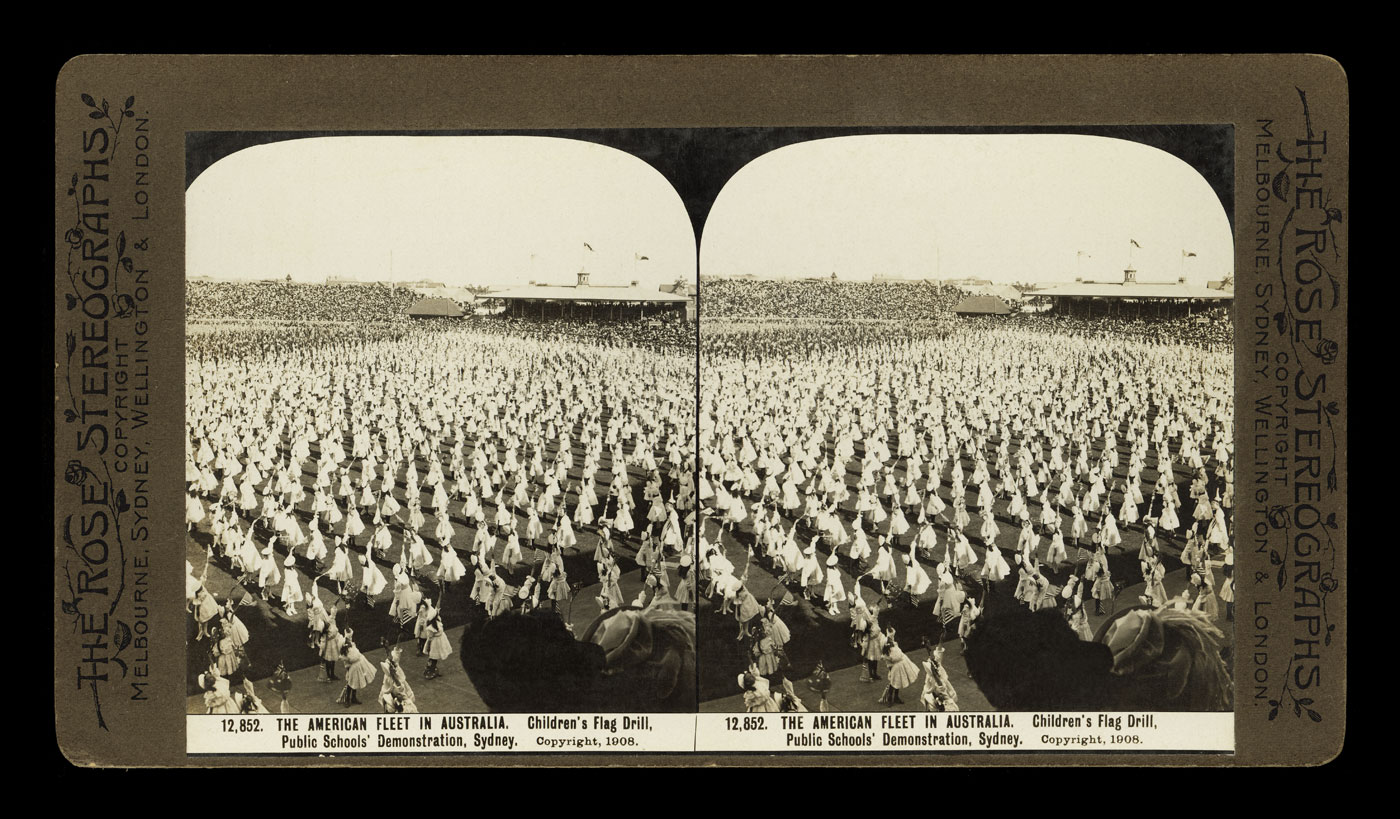

1/ How few Australian flags are flying (the Australian flag was only created following Federation in 1901), the British flag in prominence at the reviews in Centennial Park, Sydney and Flemington Racecourse, Melbourne. An Australian flag can be observed at the very bottom of the Children’s Flag Drill, Public Schools’ Demonstration, Sydney, 1908 photograph and flying alternatively between the American flag in the review at Flemington Racecourse.

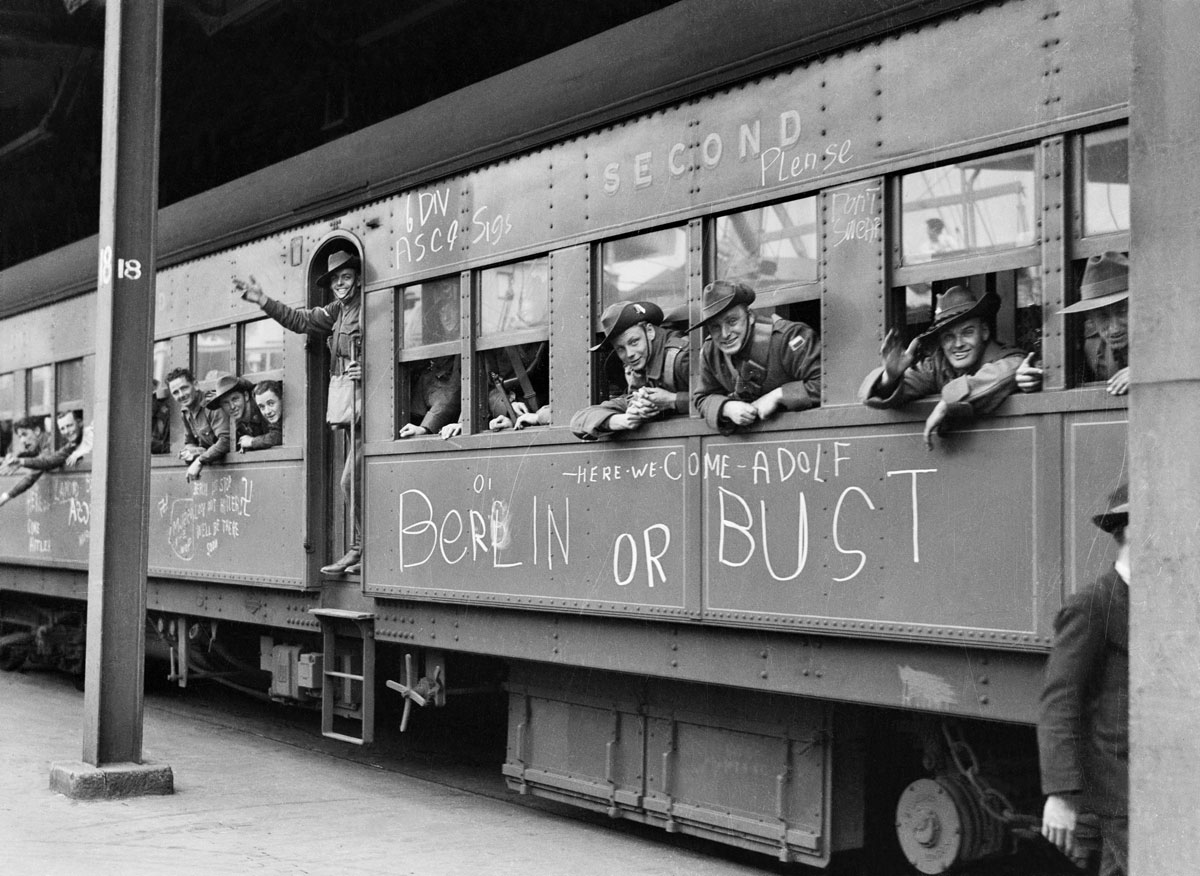

2/ How militarised the society seems to be, with huge turn out of spectators to the parades and reviews – just look at the crowds in Marines Marching through Martin Place, Sydney, 1908 and packing the stands at Flemington in Military Review, Flemington. The Admiral, the Governor, the Prime Minister, &c., (1908). It comes as a surprise, then, that just eight and nine years later, at the height of the First World War, two referendums were held in which compulsory conscription was defeated by popular vote.

3/ How many people – men, women and children – are all wearing hats. Royal Visit to Melbourne, May 1901 (detail below) is almost a bourgeois Dickensian scene of merriment, with all the men and women wearing de rigueur hats. The four women at the front are especially impressive. The crowd is pressed up against the barrier and stacked high behind to get the best view, causing a flattening of the picture plane, the bodies and attitudes of “the people” almost becoming a picture puzzle.

Other points of interest include:

~ A comparison between the horizontal point of view of 2nd Victorian Contingent. Horses Going Aboard (1900, below) replete with geometric shapes and forms; and the structure of Steigltiz’s The Steerage, 1907 with its closer cropping, stronger geometric elements and split horizontal and downward gaze.

~ Also notice the photographer in cap up a very narrow ladder at left in Jack Tars at the Military Review, on the Flemington Racecourse, Melbourne (1908, detail), just about to be passed a dark slide for his plate camera that is mounted on top of the ladder.

~ The Jack Tars make an interesting group of men, marching along with their rifles. I wonder what they thought of Australia at the turn of the century?

Please make sure you enlarge the photographs to see all of the details.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Ellie Young for lending me the stereocards in this posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Rose’s Stereoscopic Views

George Rose (Publisher), Windsor, Melbourne

2nd Victorian Contingent. Horses Going Aboard

Melbourne, Boer War embarkation, 1900

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

1900-01-13. ONLOOKERS WATCH THE HORSES OF THE 2ND VICTORIAN CONTINGENT TO THE BOER WAR BEING PUT ABOARD THE STEAMSHIP “EURYALUS”, BOUND FOR SOUTH AFRICA. THE SECOND VICTORIAN CONTINGENT CONSISTED ENTIRELY OF MOUNTED RIFLES.

Departed Melbourne: SS Euryalus 13 January 1900.

Raised predominantly on the Mounted Rifle Regiment, formed by Lt-Col Tom Price in 1885, and Victorian Rangers, Militia including the battalions of the Infantry Brigade and some from the Royal Australian Artillery. Colonel Price was initially made CO of the Hanover Road Field Force, including one battalion of Lancashire Militia, two companies of Prince Albert’s Guards and Tasmanians. Price was the only Australian Colonial Officer placed in command of British units during the Boer War.

A seminal moment in the Boer War was the capture of Pretoria in 1900 by British commander, Lord Roberts. The Victorian 2nd (Mounted Rifles) Contingent was the first unit to enter the city. A large number of this unit were invalided back to Victoria, having experienced starvation and extreme exhaustion on some treks.

Strength: 265

Service period: Feb 1900 – Dec 1900.

Text from the Defending Victoria website. No longer available online

As part of the British Empire, the Australian colonies offered troops for the war in South Africa. Australians served in contingents raised by the six colonies or, from 1901, by the new Australian Commonwealth. For a variety of reasons many Australians also joined British or South African colonial units in South Africa: some were already in South Africa when the war broke out; others either made their own way to the Cape or joined local units after their enlistment in an Australian contingent ended. Recruiting was also done in Australia for units which already existed in South Africa, such as the Scottish Horse.

Australians served mostly in mounted units formed in each colony before despatch, or in South Africa itself. The Australian contribution took the form of five “waves”. The first were the contingents raised by the Australian colonies in response to the outbreak of war in 1899, which often drew heavily on the men in the militia of the colonial forces. The second were the “bushmen” contingents, which were recruited from more diverse sources and paid for by public subscription or the military philanthropy of wealthy individuals. The third were the “imperial bushmen” contingents, which were raised in ways similar to the preceding contingents, but paid for by the imperial government in London. Then were then the “draft contingents”, which were raised by the state governments after Federation on behalf of the new Commonwealth government, which was as yet unable to do so. Finally, after Federation, and close to the end of the war, the Australian Commonwealth Horse contingents were raised by the new Federal government. These contingents fought in both the British counter-offensive of 1900, which resulted in the capture of the Boer capitals, and in the long, weary guerrilla phases of the war which lasted until 1902. Colonial troops were valued for their ability to “shoot and ride”, and in many ways performed well in the open war on the veldt. There were significant problems, however, with the relatively poor training of Australian officers, with contingents generally arriving without having undergone much training and being sent on campaign immediately. These and other problems faced many of the hastily raised contingents sent from around the empire, however, and were by no means restricted to those from Australia…

The Australians at home initially supported the war, but became disenchanted as the conflict dragged on, especially as the effects on Boer civilians became known…

Conditions for both soldiers and horses were harsh. Without time to acclimatise to the severe environment and in an army with a greatly over-strained logistic system, the horses fared badly. Many died, not just in battle but of disease, while others succumbed to exhaustion and starvation on the long treks across the veld. Quarantine regulations in Australia ensured that even those which did survive could not return home. In the early stages of the war Australian soldier losses were so high through illness that components of the first and second contingents ceased to exist as viable units after a few months of service.

Extract of text from “Australia and the Boer War, 1899-1902” on the Australian War Memorial website

Rose’s Stereoscopic Views

George Ross (Publisher), Windsor, Melbourne

2nd Victorian Contingent. Horses Going Aboard (detail)

Melbourne, Boer War embarkation, 1899-1900

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

Columbia Stereoscopic Company

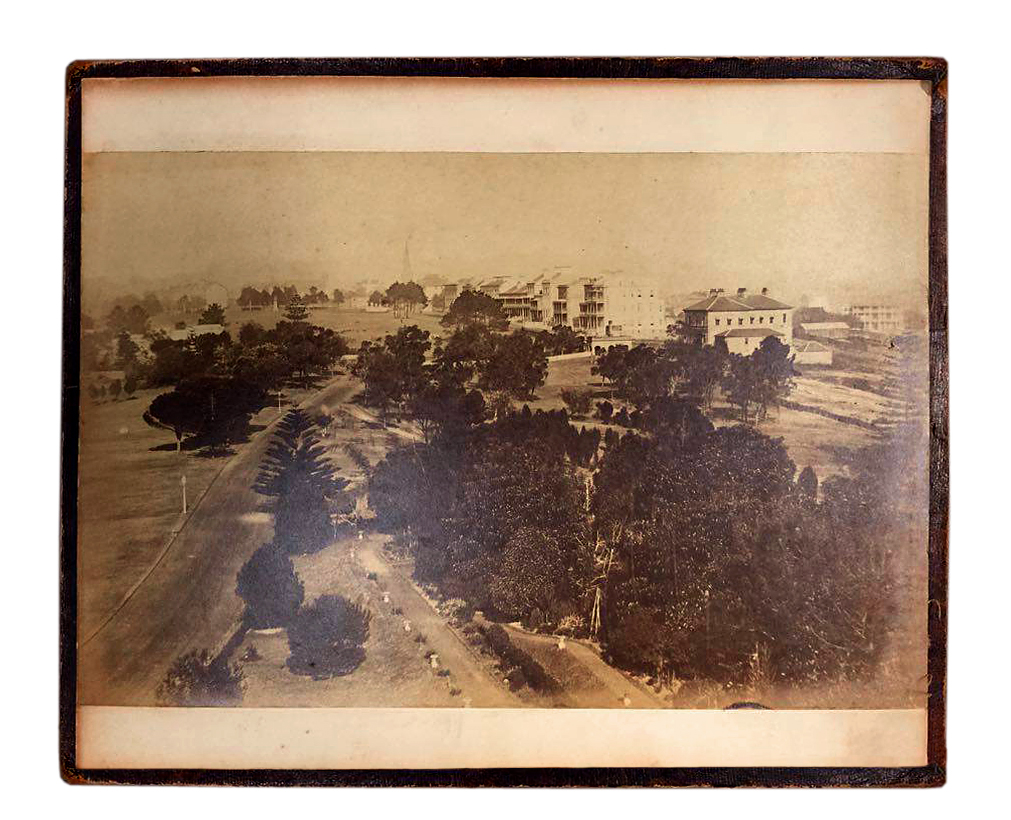

Royal Visit to Melbourne, May 1901

1901

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

Columbia Stereoscopic Company

Royal Visit to Melbourne, May 1901 (detail)

1901

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

Columbia Stereoscopic Company

Royal Visit to Melbourne, May 1901 (detail)

1901

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The visit to Australia by the Duke of York in 1901 was the first by a British heir-apparent, and it was the occasion of a frenzy of social activity, in which the Duke and Duchess were feted in parades, reviews, balls, dinners, concerts and a range of ceremonies. The royal visit became, in the minds of many, a much larger event than that which was the purpose of the visit; namely, the opening of the first Commonwealth Parliament.

Members of the royal party travelled to Australia on the royal yacht Ophir, which departed from Portsmouth on 16 March. They formally arrived in Melbourne on St Kilda pier at 2.00pm on 6 May, and immediately afterwards took part in a grand procession which travelled along St Kilda Road to the centre of Melbourne, past the front of Parliament House, and to Government House. Mounted troops from all Australian states and New Zealand participated in the procession, which was almost two kilometres long and took two hours to pass some points of the seven kilometre route.

The streets of Melbourne were lined with half a million spectators, many of whom had bought tickets to sit in wooden stands erected two or three stories high. People spilled from every window, step and vantage-point, waving flags and cheering. Thirty-five thousand school children waved union jacks and sang ‘God save the King’ and ‘God Bless the Prince of Wales’ from the slopes of the Domain.

Text from “The Royal Visit: Opening of the First Parliament” 9th May 1901 on the Parliament of Australia exhibitions website

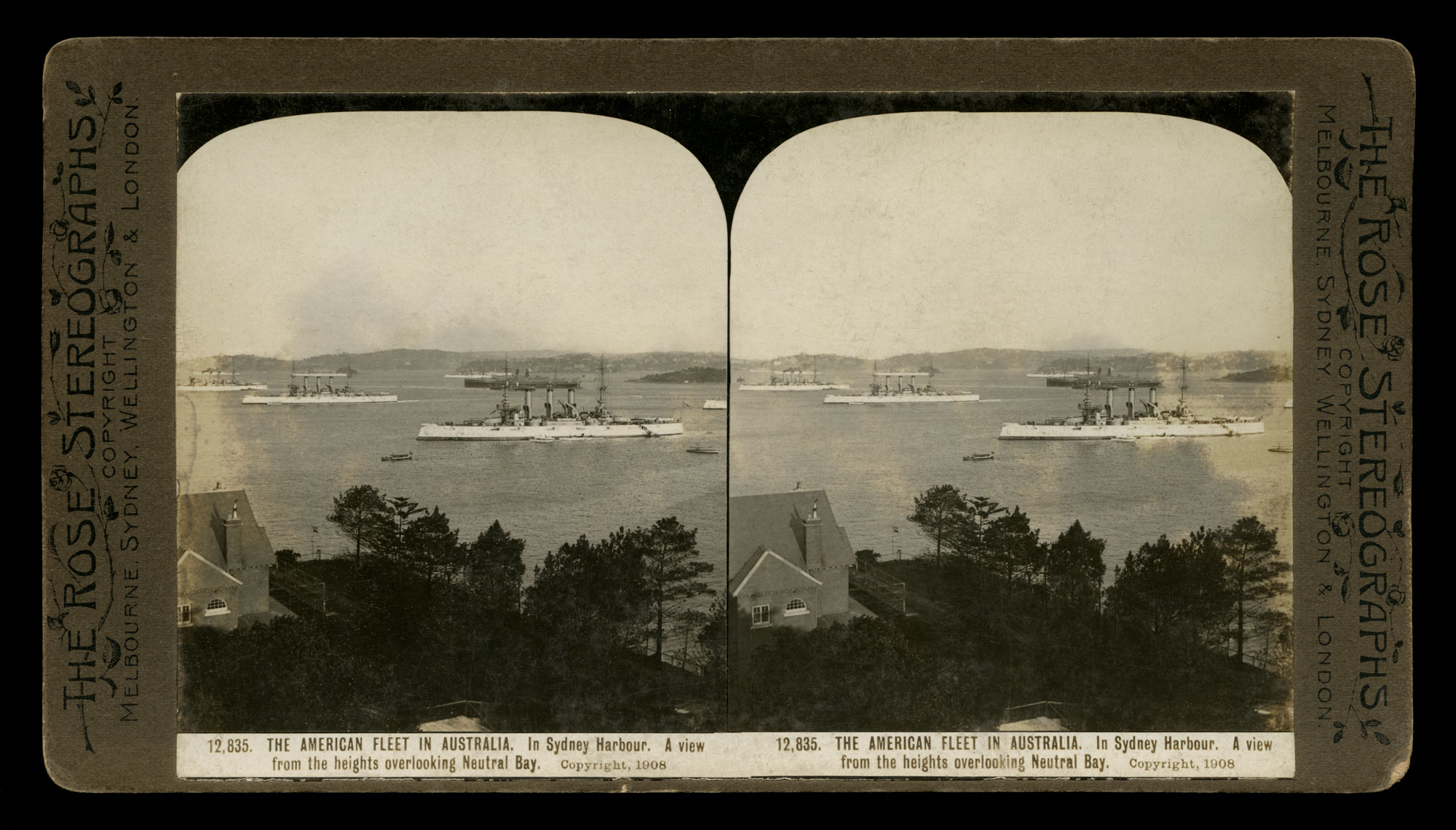

The Rose Stereographs

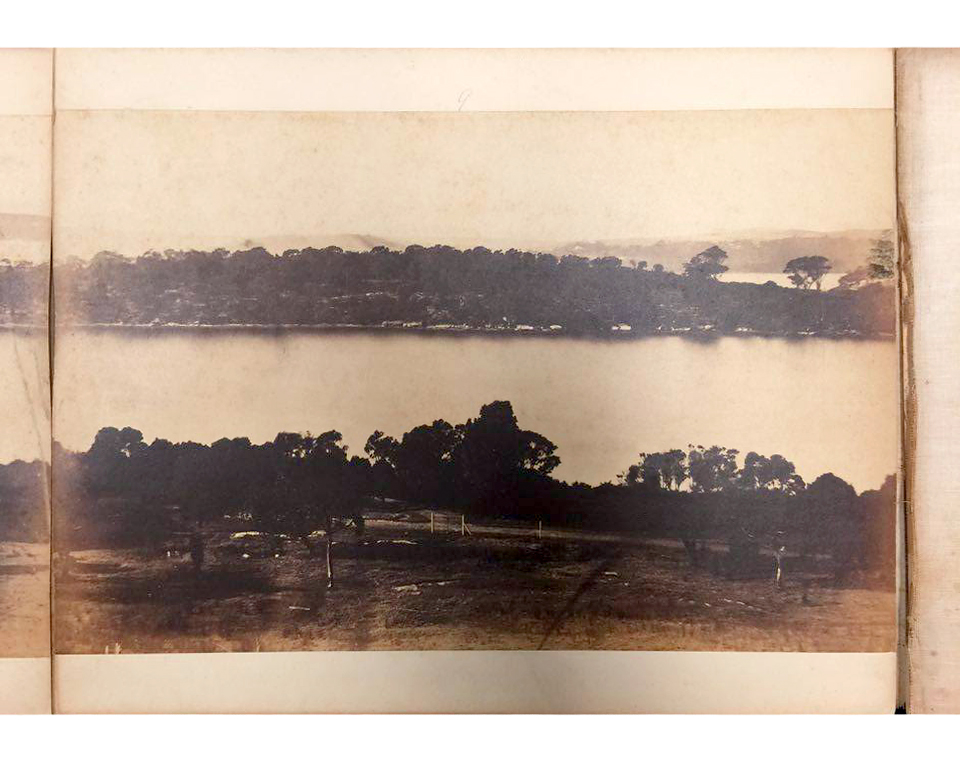

In Sydney Harbour. A view from the heights overlooking Neutral Bay

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The fleet was given a tremendous welcome. Thursday 20 August 1908 was a public holiday and a week long celebration followed. Fleet Week celebrations and entertainments included the Official Landing and Public Reception, a review at Centennial Park, parades, luncheons, dinners, balls, concerts, theatre parties, sporting events such as boxing, football and baseball matches, a gymkhana including a tug-of-war and a regatta. Buildings and streets were decorated and illuminated at night. There were daylight and night time fireworks displays. Excursions were arranged for the Americans to visit Manly, Parramatta, Newcastle, The National Park, the Illawarra and the Blue Mountains. The fleet stayed in Sydney until its departure for Melbourne on 27 August 1908.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website

The Rose Stereographs

In Sydney Harbour. A view from the heights overlooking Neutral Bay (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Three fine U.S. battleships in Sydney Harbour, viewed from Cremorne Heights

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

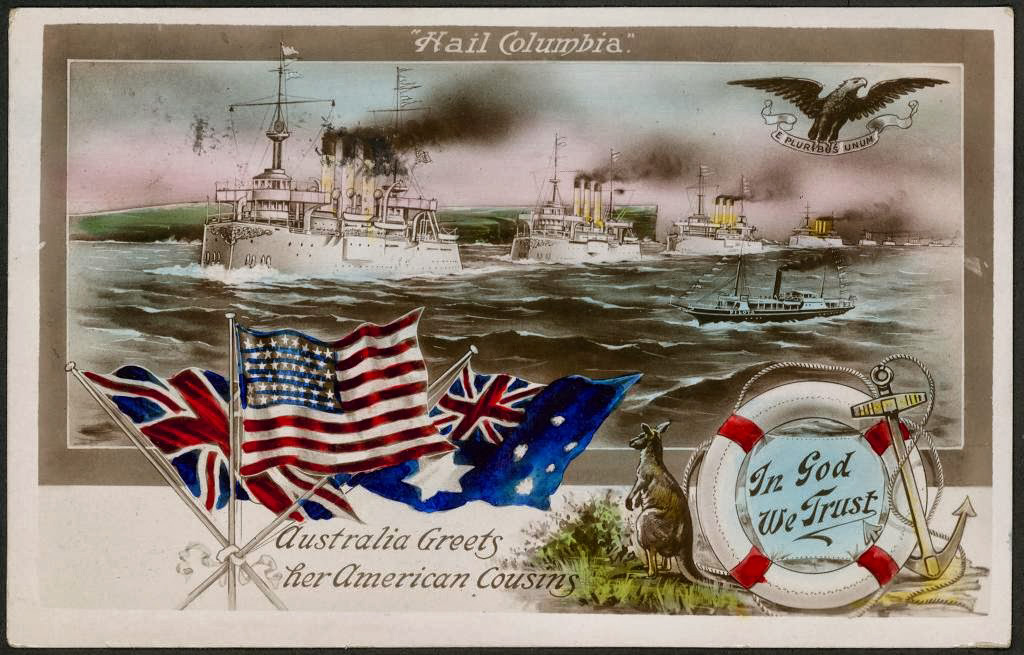

“Hail Columbia”

Australia Greets her American Cousins

In God We Trust

1908

Postcard

Harry T. Weston (publisher)

Souvenir of the American Fleet’s Visit to the Commonwealth of Australia. 1908

1908

Postcard

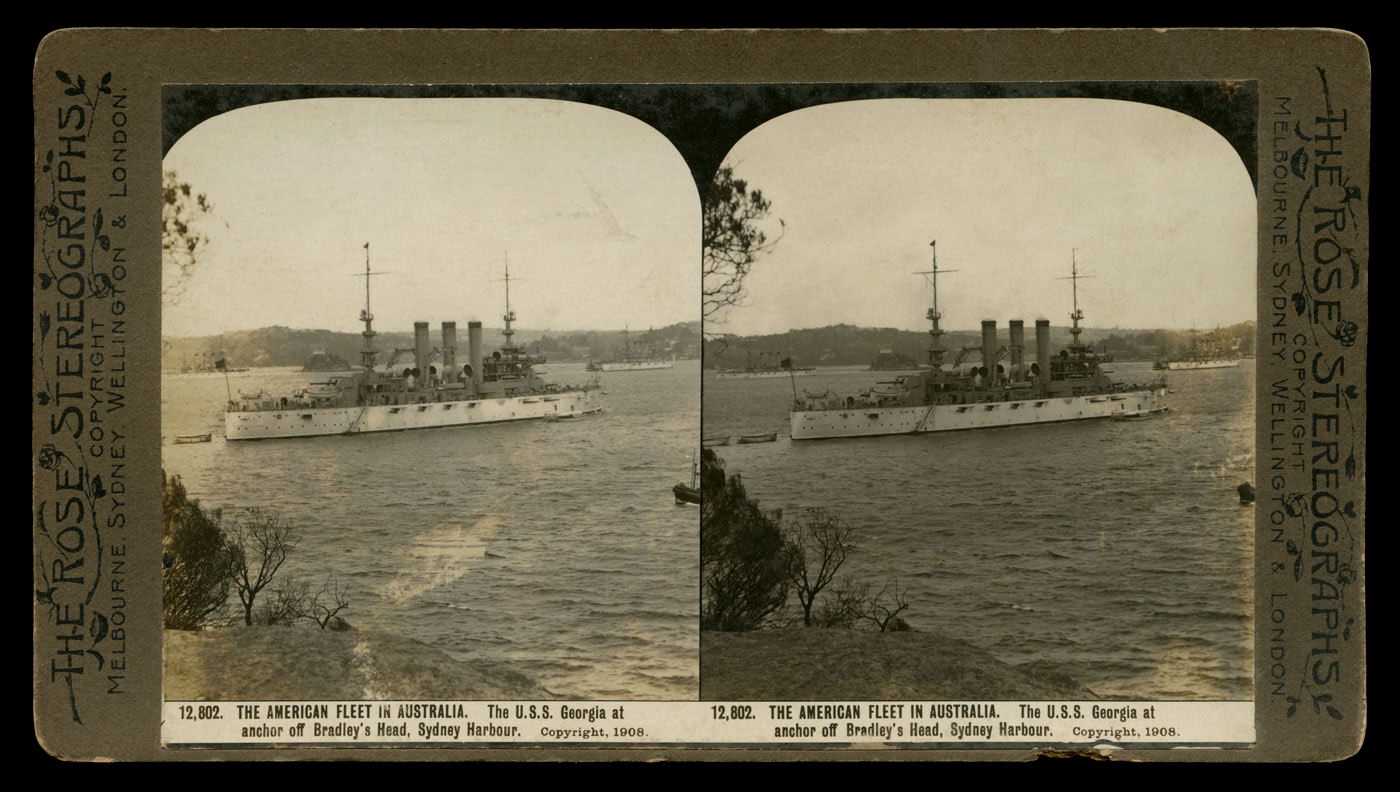

The Rose Stereographs

The U.S.S. Georgia at anchor off Bradley’s Head, Sydney Harbour

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

The U.S.S. Georgia at anchor off Bradley’s Head, Sydney Harbour (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

On 20 August 1908 well over half a million Sydneysiders turned out to watch the arrival of the United States (US) Navy’s ‘Great White Fleet’. For a city population of around 600,000 this was no mean achievement. The largest gathering yet seen in Australia, it far exceeded the numbers that had celebrated the foundation of the Commonwealth just seven years before. Indeed, the warm reception accorded the crews of the 16 white-painted battleships during ‘Fleet Week’, was generally regarded as the most overwhelming of any of the ports visited during the 14 month and 45,000 mile global circumnavigation. The NSW Government declared two public holidays, business came to a standstill and the unbroken succession of civic events and all pervading carnival spirit encountered in Sydney (followed by Melbourne and Albany) severely tested the endurance of the American sailors…

One man undoubtedly well pleased with the visit’s success was Australia’s then Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, who had not only initiated the invitation to US President Theodore Roosevelt, but had persisted in the face of resistance from both the British Admiralty and the Foreign Office. By making his initial request directly to American diplomats rather than through imperial authorities Deakin had defied protocol, but he was also taking one of the first steps in asserting Australia’s post-colonial independence. His motives for doing so were complex. He was, after all, a strong advocate for the British Empire and Australia’s place within it, but he also wished to send a clear message to Whitehall that Australians were unhappy with Britain’s apparent strategic neglect.

The security of the nascent Commonwealth might still ultimately depend on the Royal Navy’s global reach, but the ships of the small, rarely seen and somewhat obsolescent Imperial Squadron based in Sydney did not inspire confidence. As an officer in the US flagship, observed during the visit: ‘These vessels were, with the exception of the Powerful [the British flagship], small and unimportant … Among British Officers this is known as the Society Station and by tacit consent little work is done’…

Feeling both isolated and vulnerable, it was easy for the small Australian population to believe that Britain was ignoring its antipodean responsibilities. The 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance (renewed in 1905), which had allowed the Royal Navy to reduce its Pacific presence, did little to alleviate these fears. Remote from the British Empire’s European centre, Australians had no confidence that their interests, and in particular their determination to prevent Asiatic settlement, would be accommodated in imperial foreign policy. Japan’s evident desire for territorial expansion, its decisive naval victory over the Russians at Tsushima in 1905, and its natural expectation of equal treatment for its citizens all seemed to reinforce the need for Australia to explore alternative security strategies.

Staunchly Anglophile, Deakin was not necessarily seeking to establish direct defence ties with the United States, but more than a few elements in Australian society were prepared to see in America the obvious replacement for Britain’s waning regional power. A new and evidently growing presence in the Pacific, the United States possessed a similar cultural heritage and traditions, and as even Deakin took care to note in his letter of invitation: ‘No other Federation in the world possesses so many features [in common with] the United States as does the Commonwealth of Australia’…

No British battleship, let alone a modern fleet, had ever entered Australasian waters. So with the arrival of the American vessels locals were treated to the greatest display of sea power they had even seen. While the public admired the spectacle’s grandeur, for those interested in defence and naval affairs it was an inspiration. This too was a part of Deakin’s plan, for although he was a firm believer in Australia’s maritime destiny, where defence was concerned national priorities still tended towards the completion of land rather than maritime protection. The Prime Minister’s own scheme for an effective local navy was making slow progress, and like Roosevelt he recognised the need to rouse popular support.

In this, the visit of the Great White Fleet played a crucial role, for it necessarily brought broader issues of naval defence to the fore, and made very plain the links between sea power and national development. Americans clearly had a real sense of patriotism and national mission. Having been tested and hardened in a long and bitter civil war they were confident that the United States was predestined to play a great part in the world. Australians, on the other hand, still saw Federation as a novelty and their first allegiance as state-based. One English traveller captured well the prevailing mood. ‘Australia’, he wrote, ‘presents a paradox. There is a breezy buoyant Imperial spirit. But the national spirit, as it is understood elsewhere, is practically non-existent’.

Extracts from Dr David Stevens. “The Great White Fleet’s 1908 Visit To Australia,” on the Royal Australian Navy website [Online] Cited 11/11/2106. No longer available online

| Sydney, Australia | 20 August 1908 | 28 August 1908 |

| Melbourne, Australia | 29 August 1908 | 5 September 1908 |

| Albany, Australia | 11 September 1908 | 18 September 1908 |

The Fleet, First Squadron, and First Division were commanded by Rear Admiral Charles S. Sperry. First Division consisted of Connecticut, the Fleet’s flagship, Captain Hugo Osterhaus, Kansas, Captain Charles E. Vreeland, Minnesota, Captain John Hubbard, and Vermont, Captain William P. Potter.

Second Division consisted of Georgia, the Division flagship, Captain Edward F. Qualtrough, Nebraska, Captain Reginald F. Nicholson, New Jersey, Captain William H.H. Southerland, and Rhode Island, Captain Joseph B. Murdock.

The Second Squadron and Third Division were commanded by Rear Admiral William H. Emory. Third Division consisted of Louisiana, the Squadron flagship, Captain Kossuth Niles, Virginia, Captain Alexander Sharp, Missouri, Captain Robert M. Doyle, and Ohio, Captain Thomas B. Howard.

Fourth Division was commanded by Rear Admiral Seaton Schroeder. Fourth Division consisted of Wisconsin, the Division flagship, Captain Frank E. Beatty, Illinois, Captain John M. Bowyer, Kearsarge, Captain Hamilton Hutchins, and Kentucky, Captain Walter C. Cowles.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

![F.H. Boone & Co., 'Untitled [Wicker chair supplied to the American Fleet during their visit]' 1908 F.H. Boone & Co., 'Untitled [Wicker chair supplied to the American Fleet during their visit]' 1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/photo-of-one-of-the-wicker-chairs-web.jpg?w=700)

F.H. Boone & Co

Untitled [Wicker chair supplied to the American Fleet during their visit]

1908

NRS 905, Chief Secretary, Letters Received, 1908 [5/6990]

Note the Union Jack and the Stars and Stripes on the back of the chair.

Police Department, Inspector General’s Office, Sydney

“URGENT MATTER”

8th September, 1908

NRS 905, Chief Secretary, Letters Received, 1908 [5/6995]

The Rose Stereographs

A magnificent view of the fine battleship U.S.S. Ohio

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

A magnificent view of the fine battleship U.S.S. Ohio (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

Semco Series

American Fleet Souvenir Post Card (front and verso)

1908

Postcard

C.B & Co. S

Australia Welcomes The American Fleet

1908

Postcard

The Rose Stereographs

The March Past of the Navy at the Review, Centennial Park, Sydney

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

The March Past of the Navy at the Review, Centennial Park, Sydney (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

New South Wales mounted infantry at the review, Centennial Park, Sydney

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

New South Wales mounted infantry at the review, Centennial Park, Sydney (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Procession of Metropolitan and Country Fire Brigades, Sydney

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Procession of Metropolitan and Country Fire Brigades, Sydney (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Marines Marching through Martin Place, Sydney

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Marines Marching through Martin Place, Sydney (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Great Naval Parade of American Sailors at Sydney, Australia, August 23, 1908

1908

Postcard

The Rose Stereographs

Procession in Sydney. The Admiral’s Carriage turning out of Martin Place

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Procession in Sydney. The Admiral’s Carriage turning out of Martin Place (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Children’s Flag Drill, Public Schools’ Demonstration, Sydney

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Children’s Flag Drill, Public Schools’ Demonstration, Sydney (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Inside Port Phillip Heads, en route to Hobson’s Bay, Victoria

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

Victoria pulled out all the stops for ‘Fleet Week’, and records held at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) show the scale and scope of the welcome: newspaper reporters waxing lyrical about the ‘Turner-esque’ picture of the ships steaming past Dromana; sixteen thousand copies of maps, guide books, railway schedules and souvenir programs printed and distributed to the ships’ crews to guide them around Australia’s biggest city; hundreds of thousands of extra train travellers swarming into Williamstown to see the Fleet, and into Melbourne to meet the sailors; young cadets marching five days from Ballarat to take part in the welcome parade; and of course sailors ‘with a girl on each arm’.

Melburnians laid out the red, white and blue welcome mat for the new Pacific sea power. The records describe months of preparations by state and city officials to celebrate the visit. Suppliers of bunting and decorations rushed to offer their wares, and scores of Victorian town councils, as well as public and private clubs and societies, wrote to beg the State Cabinet American Fleet Reception Committee to consider them when scheduling the official program of events. The Victorian Railways offered cheap excursion trains from country centres, and free travel to the sailors, and carried record numbers of passengers during Fleet Week. Victorians and Americans mingled, as thousands visited the Royal Agricultural Show, where they saw dumbbell and wand exercises by state school students, and flocked to the racing at Flemington, where the Washington Steeplechase and Fleet Trotting Cup were run. The Zoo, the Aquarium and ‘Glacarium’ all offered free entry to visiting sailors.

While country Victoria travelled into the city to meet the sailors, the sailors journeyed out to see the country. At the invitation of a local American citizen, some sailors made the long trip to Mirboo North in East Gippsland, where they saw wood chopping and ‘Aboriginal boomerang throwing’ and took part in foot races (a handsome silver-mounted emu-egg trophy was carried home by the victor) and a tug-of-war. Others travelled to Bendigo and to Ballarat, watching Australian Rules Football and visiting the mines.

In such a flurry of welcome and activity, there were problems, both comic and tragic. The failure of an American officer to pass on an invitation meant that only seven sailors turned up to a reception and dinner at the Exhibition Buildings, where catering had been laid on for 2,800. Two sailors died in train-related accidents, with newspapers quoting a comrade as saying ‘we lose a few in every port’. Spruiking of the state’s liveability was also in evidence. Visitors were proudly told that, in Victoria, ‘All railways … and supplies of water are state-owned’ and that we had ‘Factories Acts and Wage Boards, Pure Food Laws, Compulsory Vaccinations’ and ‘Manhood Suffrage’ – the Fleet had arrived just three months shy of Victoria awarding the vote to women.

This combination of attractions no doubt contributed to the sailors’ view that Melbourne was the ‘best port of call’ in their 14-month, 20-port call, round-the-world voyage. So convinced were the visitors of Victoria’s, and Australia’s, attractions that 221 deserters jumped ship in Melbourne. The USS Kansas stayed on for a number of days after the rest of the Fleet departed for Albany, Western Australia, in part to wait for a mail steamer, but also to collect stragglers. A reward of $10 was advertised for the successful return of each deserter to his ship, but the conditions of the reward were so difficult to meet that no money was ever paid. By the time the Kansas finally weighed anchor and bade farewell to Melbourne, more than half the deserters had been recovered, but about a hundred men remained behind to start a new life.

Anonymous text. “Great White Fleet – 105 years on,” on the Public Records of Victoria website [Online] Cited 11/11/2016. No longer available online

The Rose Stereographs

Inside Port Phillip Heads, en route to Hobson’s Bay, Victoria (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Steaming up Port Phillip Bay, in the direction of Port Melbourne

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Steaming up Port Phillip Bay, in the direction of Port Melbourne (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

Wellman & Co., St Kilda (Publisher)

The People of the Southern Cross Offer Greetings to their Kinsmen of the Stars & Stripes

1908

Postcard

Visit of the United States Fleet To Melbourne Australia, Sep 1908

1908

Postcard

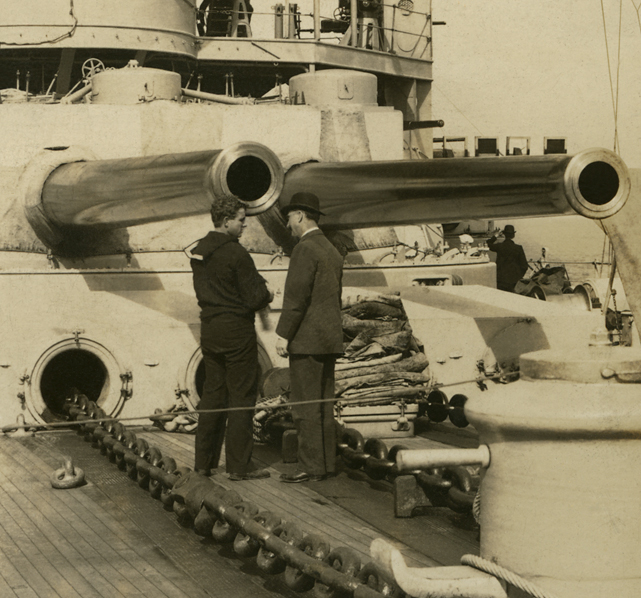

The Rose Stereographs

The two 12-inch guns, ‘Ben’ and ‘Jim,’ on the U.S. battleship Louisiana

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

The two 12-inch guns, ‘Ben’ and ‘Jim,’ on the U.S. battleship Louisiana

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Rear-Admiral Sperry at St. Kilda Pier. Inspection of Naval Brigade

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Rear-Admiral Sperry at St. Kilda Pier. Inspection of Naval Brigade (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Military Review, Flemington. The Admiral, the Governor, the Prime Minister, &c.

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Military Review, Flemington. The Admiral, the Governor, the Prime Minister, &c. (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

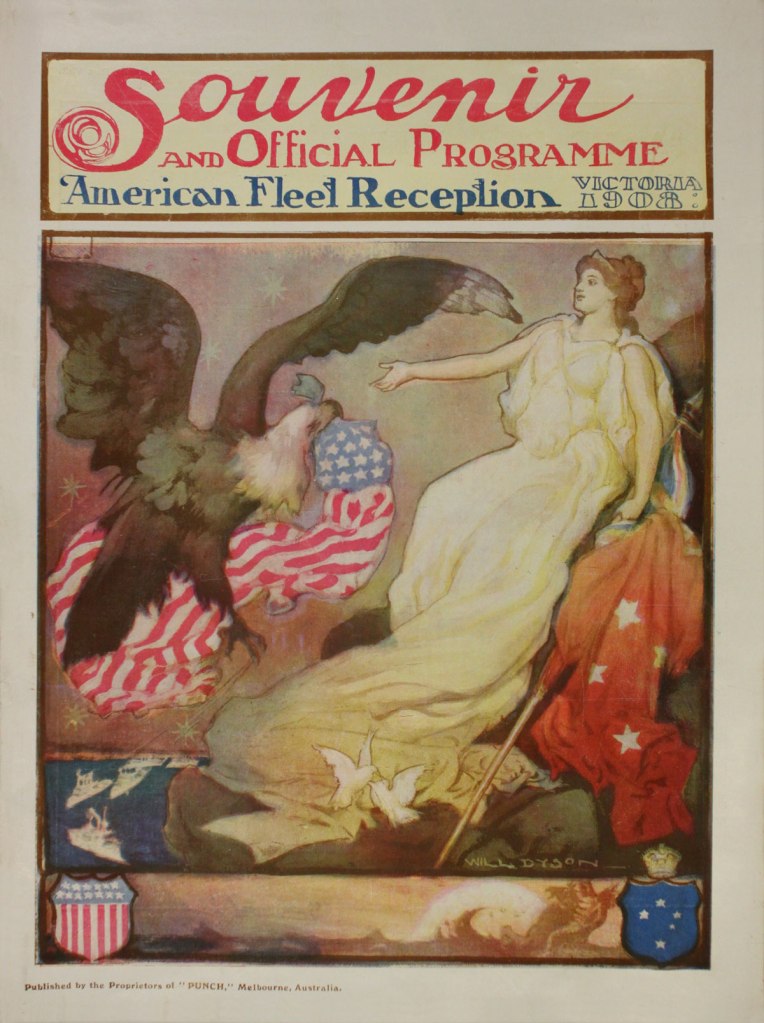

Proprietors of “Punch”, Melbourne Australia (publishers)

Souvenir and Official Programme, American Fleet Reception, Victoria 1908

1908

The Rose Stereographs

Jack Tars at the Military Review, on the Flemington Racecourse, Melbourne

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

The Rose Stereographs

Jack Tars at the Military Review, on the Flemington Racecourse, Melbourne (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

Jack Tar

Jack Tar (also Jacktar, Jack-tar or Tar) was a common English term originally used to refer to seamen of the Merchant or Royal Navy, particularly during the period of the British Empire. By World War I the term was used as a nickname for those in the U.S. Navy. Both members of the public, and seafarers themselves, made use of the name in identifying those who went to sea. It was not used as a pejorative and sailors were happy to use the term to label themselves.

Text from the Wikipedia website

The Rose Stereographs

Jack Tars at the Military Review, on the Flemington Racecourse, Melbourne (detail)

1908

From the series The American Fleet in Australia

Stereocard

Silver gelatin photograph

![George Roberts (Australian born United Kingdom, c. 1800-1865) '[Mrs Macquarie's chair]' c. 1843-1865 George Roberts (Australian born United Kingdom, c. 1800-1865) '[Mrs Macquarie's chair]' c. 1843-1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mrs-macquaries-chair-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.