Exhibition dates: 4th June – 11th September, 2016

Curator: Keith Hartley

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Self-portrait with gryphon and Joan Miró (Head of a Catalan Peasant) tattoo, both by Alex Binnie, London

1998

I have the five elements in tattoos. In the Head of a Catalan Peasant by Joan Miró featured in the posting, the red hat – in the form of a triangle – signifies ‘fire’ in Western occult mythology.

“Surrealism is not a movement. It is a latent state of mind perceivable through the powers of dream and nightmare.”

~ Salvador Dalí

“As beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table.”

~ Comte de Lautréamont

“A constant human error: to believe in an end to one’s fantasies. Our daydreams are the measure of our unreachable truth. The secret of all things lies in the emptiness of the formula that guard them.”

~ Floriano Martins

Many thankx to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

![Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893-1983) 'Tête de Paysan Catalan' [Head of a Catalan Peasant] 1925 from the Collections of Roland Penrose, Edward James, Gabrielle Keiller and Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June- Sept, 2016 Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893-1983) 'Tête de Paysan Catalan' [Head of a Catalan Peasant] 1925 from the exhibition 'Surreal Encounters: Collecting the Marvellous: Works from the Collections of Roland Penrose, Edward James, Gabrielle Keiller and Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June- Sept, 2016](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/joan-mirc3b3-tc3aate-de-paysan-catalan-web.jpg?w=795)

Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893-1983)

Tête de Paysan Catalan [Head of a Catalan Peasant]

1925

Oil on canvas

92.4 x 73cm

Collection: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Purchased jointly with Tate, with the assistance of the Art Fund 1999

Francis Picabia (French, 1879-1953)

Fille née sans mère [Girl Born without a Mother]

c. 1916-1917

Gouache and metallic paint on printed paper

50 x 65cm

Collection: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, purchased 1990

René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967)

Au seuil de la liberté (On the Threshold of Liberty)

1930

Oil on canvas

114 x 146cm

Collection: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (Formerly collection of E. James), purchased 1966

André Masson (French, 1896-1987)

Massacre

1931

Oil on canvas

Collection: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg/ Pietzsche Collection

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

La Joie de vivre [The Joy of Life]

1936

Oil on canvas

73.5 x 92.5cm

Collection: National Galleries of Scotland

Purchased with the assistance of the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Art Fund 1995

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

The Fireside Angel (The Triumph of Surrealism)

L’ange du foyer (Le triomphe du surréalisme)

1937

Oil on canvas

114 cm x 146cm

Dorothea Tanning (American, 1910-2012)

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik [A Little Night Music]

1943

Oil on canvas

40.7 x 61cm

Collection: Tate (formerly collection of R. Penrose)

Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund and the American Fund for the Tate Gallery 1997

Apart from three weeks she spent at the Chicago Academy of Fine Art in 1930, Tanning was a self-taught artist. The surreal imagery of her paintings from the 1940s and her close friendships with artists and writers of the Surrealist Movement have led many to regard Tanning as a Surrealist painter, yet she developed her own individual style over the course of an artistic career that spanned six decades.

Tanning’s early works – paintings such as Birthday and Eine kleine Nachtmusik (1943, Tate Modern, London) – were precise figurative renderings of dream-like situations. Like other Surrealist painters, she was meticulous in her attention to details and in building up surfaces with carefully muted brushstrokes. Through the late 1940s, she continued to paint depictions of unreal scenes, some of which combined erotic subjects with enigmatic symbols and desolate space. During this period she formed enduring friendships with, among others, Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Cornell, and John Cage; designed sets and costumes for several of George Balanchine’s ballets, including The Night Shadow (1945) at the Metropolitan Opera House; and appeared in two of Hans Richter’s avant-garde films.

Over the next decade, Tanning’s painting evolved, becoming less explicit and more suggestive. Now working in Paris and Huismes, France, she began to move away from Surrealism and develop her own style. During the mid-1950s, her work radically changed and her images became increasingly fragmented and prismatic, exemplified in works such as Insomnias (1957, Moderna Museet, Stockholm). As she explains, “Around 1955 my canvases literally splintered… I broke the mirror, you might say.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Marcel Duchamp (French, 1887-1968)

La Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Suitcase)

1935-1941

Sculpture, leather-covered case containing miniature replicas and photographs of Duchamp’s works

10 x 38 x 40.5cm

Collection: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, presented anonymously 1989

Paul Delvaux (Belgian, 1897-1994)

L’Appel de la Nuit (The Call of the Night)

1938

Oil on canvas

110 x 145cm

Collection: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Purchased with the support of the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Art Fund 1995

Delvaux’s paintings of the late 1920s and early 1930s, which feature nudes in landscapes, are strongly influenced by such Flemish Expressionists as Constant Permeke and Gustave De Smet. A change of style around 1933 reflects the influence of the metaphysical art of Giorgio de Chirico, which he had first encountered in 1926 or 1927. In the early 1930s Delvaux found further inspiration in visits to the Brussels Fair, where the Spitzner Museum, a museum of medical curiosities, maintained a booth in which skeletons and a mechanical Venus figure were displayed in a window with red velvet curtains. This spectacle captivated Delvaux, supplying him with motifs that would appear throughout his subsequent work. In the mid-1930s he also began to adopt some of the motifs of his fellow Belgian René Magritte, as well as that painter’s deadpan style in rendering the most unexpected juxtapositions of otherwise ordinary objects.

Delvaux acknowledged his influences, saying of de Chirico, “with him I realised what was possible, the climate that had to be developed, the climate of silent streets with shadows of people who can’t be seen, I’ve never asked myself if it’s surrealist or not.” Although Delvaux associated for a period with the Belgian surrealist group, he did not consider himself “a Surrealist in the scholastic sense of the word.” As Marc Rombaut has written of the artist: “Delvaux … always maintained an intimate and privileged relationship to his childhood, which is the underlying motivation for his work and always manages to surface there. This ‘childhood,’ existing within him, led him to the poetic dimension in art.”

The paintings Delvaux became famous for usually feature numbers of nude women who stare as if hypnotised, gesturing mysteriously, sometimes reclining incongruously in a train station or wandering through classical buildings. Sometimes they are accompanied by skeletons, men in bowler hats, or puzzled scientists drawn from the stories of Jules Verne. Delvaux would repeat variations on these themes for the rest of his long life…

Text from the Wikipedia website

Photograph album: International Surrealist Exhibition, London 1936

Made 1936-1939

Images taken by Chancery. Images titled by Roland Penrose

32.00 x 26.00cm

Collection: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Photo: Antonio Reeve

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Mae West Lips Sofa

1937-1938

Wood, wool

92 x 215 x 66cm

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam © Fundacion Gala – Salvador Dalí, Beeldrecht Amsterdam 2007.

© Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS, 2015

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Couple aux têtes pleines de nuages [Couple with their Heads Full of Clouds]

1936

Oil on canvas

Left figure: 82.5 x 62.5cm; right figure: 92.5 x 69.5cm

Collection: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (Formerly collection of E. James)

Purchased with the support of The Rembrandt Association (Vereniging Rembrandt) 1979

© Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS, 2015

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Impressions d’Afrique (Impressions of Africa)

1938

Oil on canvas

91.5 x 117.5cm

Collection: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (Formerly collection of E. James)

Purchased with the support of The Rembrandt Association (Vereniging Rembrandt), Prins Bernhard Fonds, Erasmusstichting, Stichting Bevordering van Volkskracht Rotterdam and Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen 1979

© Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS, 2015

Leonora Carrington (Mexican born Britain, 1917-2011)

The House Opposite

1945

Tempera on board

33 x 82cm

West Dean College, part of the Edward James Foundation

“I painted for myself… I never believed anyone would exhibit or buy my work.”

Leonora Carrington was not interested in the writings of Sigmund Freud, as were other Surrealists in the movement. She instead focused on magical realism and alchemy and used autobiographical detail and symbolism as the subjects of her paintings. Carrington was interested in presenting female sexuality as she experienced it, rather than as that of male surrealists’ characterisation of female sexuality. Carrington’s work of the 1940s is focused on the underlying theme of women’s role in the creative process.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Masterpieces from four of the finest collections of Dada and Surrealist art ever assembled will be brought together in this summer’s major exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (SNGMA). Surreal Encounters: Collecting the Marvellous will explore the passions and obsessions that led to the creation of four very different collections, which are bound together by a web of fascinating links and connections, and united by the extraordinary quality of the works they comprise.

Surrealism was one of the most radical movements of the twentieth century, which challenged conventions through the exploration of the subconscious mind, the world of dreams and the laws of chance. Emerging from the chaotic creativity of Dada (itself a powerful rejection of traditional values triggered by the horrors of the First World War) its influence on our wider culture remains potent almost a century after it first appeared in Paris in the 1920s. World-famous works by Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, René Magritte, Leonora Carrington, Giorgio de Chirico, André Breton, Man Ray, Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Yves Tanguy, Leonor Fini, Marcel Duchamp and Paul Delvaux will be among the 400 paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, artist books and archival materials, to feature in Surreal Encounters. The exhibition has been jointly organised by the SNGMA, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam and the Hamburger Kunsthalle, where it will be shown following its only UK showing in Edinburgh.

Dalí’s The Great Paranoiac (1936), Lobster Telephone (1938) and Impressions of Africa (1938); de Chirico’s Two Sisters (1915); Ernst’s Pietà or Revolution by Night (1923) and Dark Forest and Bird (1927), and Magritte’s The Magician’s Accomplice (1926) and Not to be Reproduced (1937) will be among the highlights of this exceptional overview of Surrealist art. The exhibition will also tell the personal stories of the fascinating individuals who pursued these works with such dedication and discernment.

The first of these – the poet, publisher and patron of the arts, Edward James (1907-84) and the artist, biographer and exhibition organiser, Roland Penrose (1900-84) – acquired the majority of the works in their collections while the Surrealist movement was at its height in the interwar years, their choices informed by close associations and friendships with many of the artists. James was an important supporter of Salvador Dalí and René Magritte in particular, while Penrose was first introduced to Surrealism through a friendship with Max Ernst. The stories behind James’s commissioning of works such as Dalí’s famous Mae West Lips Sofa (1938) and Magritte’s The Red Model III (1937) and the role of Penrose in the production of Ernst’s seminal collage novel Une Semaine de Bonté (1934) will demonstrate how significant these relationships were for both the artists and the collectors. Other celebrated works on show that formed part of these two profoundly important collections include Tanning’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943); Magritte’s On the Threshold of Liberty (1937); Miró’s Head of a Catalan Peasant (1925); and The House Opposite (c. 1945) by Leonora Carrington.

While the Penrose and James collections are now largely dispersed, the extraordinary collection of Dada and Surrealist art put together by Gabrielle Keiller (1908-95), was bequeathed in its entirety to the SNGMA on her death in 1995, the largest benefaction in the institution’s history. Keiller devoted herself to this area following a visit to the Venice home of the celebrated American art lover Peggy Guggenheim in 1960, which proved to be a pivotal moment in her life. She went on to acquire outstanding works such as Marcel Duchamp’s La Boîte-en-Valise (1935-41), Alberto Giacometti’s Disagreeable Object, to be Thrown Away (1931) and Girl Born without a Mother (c. 1916-17) by Francis Picabia. Recognizing the fundamental significance of Surrealism’s literary aspect, Keiller also worked assiduously to create a magnificent library and archive, full of rare books, periodicals, manifestos and manuscripts, which makes the SNGMA one of the world’s foremost centres for the study of the movement.

The exhibition will be brought up to date by the inclusion of works from the collection of Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch, who have spent more than 40 years in their quest to build up an historically balanced collection of Surrealism, which they have recently presented to the city of Berlin, where they still live. The collection features many outstanding paintings by Francis Picabia, Pablo Picasso, André Masson, Leonor Fini, Ernst, Tanguy, Magritte and Miró; sculptures by Hans Arp and Hans Bellmer; and works by André Breton, the leader of the Surrealists. Highlights include Masson’s Massacre (1931), Ernst’s Head of ‘The Fireside Angel’ (c. 1937), Picasso’s Arabesques Woman (1931) and Arp’s sculpture Assis (Seated) (1937).

The exhibition’s curator in Edinburgh, Keith Hartley, who is Deputy Director of the SNGMA, has said, “Surrealist art has captured the public imagination like perhaps no other movement of modern art. The very word ‘surreal’ has become a by-word to describe anything that is wonderfully strange, akin to what André Breton, the chief theorist of Surrealism, called ‘the marvellous’. This exhibition offers an exceptional opportunity to enjoy art that is full of ‘the marvellous’. It brings together many important works which have rarely been seen in public, by a wide range of Surrealist artists, and creates some very exciting new juxtapositions.”

Press release from SNGMA

![Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) 'Tête' [Head] 1913 Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) 'Tête' [Head] 1913](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/tc3aate-head-1913-by-pablo-picasso-web.jpg?w=763)

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973)

Tête [Head]

1913

Drawing, papiers collés with black chalk on card

43.5 x 33cm

Collection: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Purchased with assistance from the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Art Fund 1995

Photo: Antonia Reeve

© DACS / Estate of Pablo Picasso

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Pieta or Revolution by Night

1923

Oil on canvas

René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967)

The Magician’s Accomplice

1926

Oil on canvas

René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967)

L’Esprit comique (The Comic Spirit)

1928

Oil on canvas

75 x 60cm

Collection: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg/ Pietzsche Collection

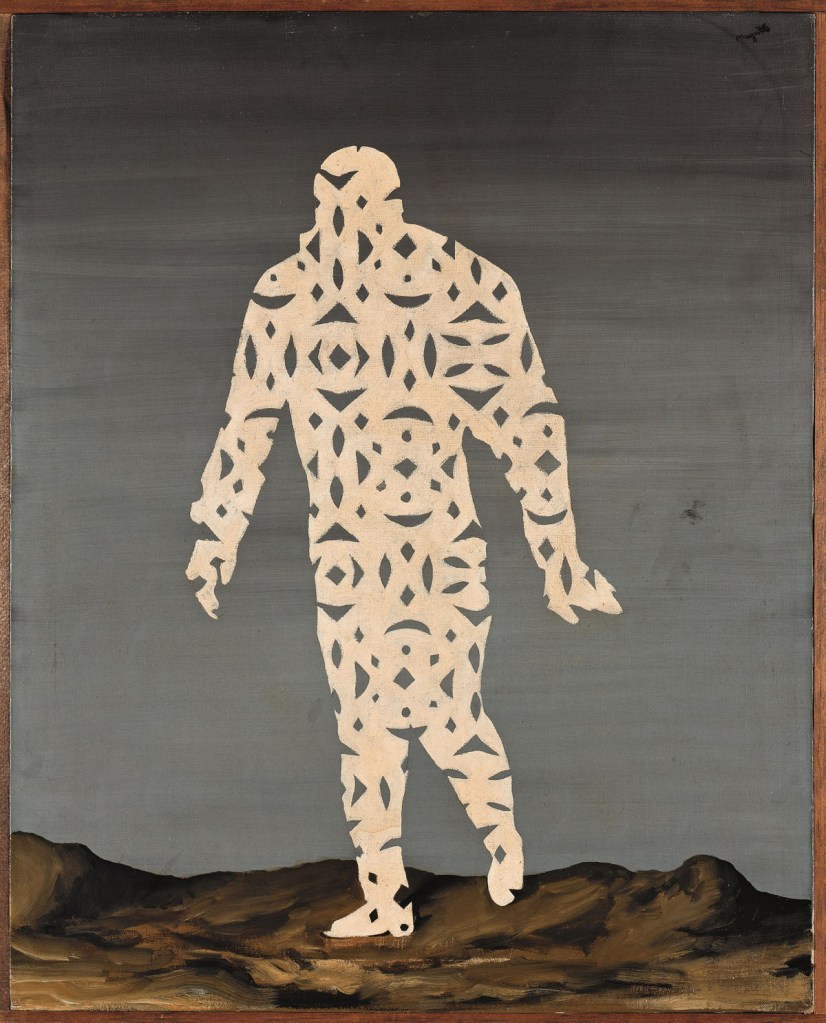

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973)

Femme aux arabesques (Arabesque Woman)

1931

Oil on canvas, 100 x 81cm

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg/ Pietzsche Collection

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Jeune homme intrigué par le vol d’une mouche non-euclidienne' [Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly] 1942–1947 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Jeune homme intrigué par le vol d’une mouche non-euclidienne' [Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly] 1942–1947](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/32_ernst-max_jeune-homme-intriguc3a9-1942-47-web.jpg?w=817)

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Jeune homme intrigué par le vol d’une mouche non-euclidienne [Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly]

1942-1947

Oil and paint on canvas

82 x 66cm

Collection: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg/ Pietzsche Collection

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ernst-une-semaine-de-bontc3a9-web.jpg?w=761)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ernst-une-semaine-de-bontc3a9-web2.jpg?w=755)

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

Une semaine de bonté [A Week of Kindness]

1934

Collage graphic novel

Une semaine de bonté [A Week of Kindness] is a graphic novel and artist’s book by Max Ernst, first published in 1934. It comprises 182 images created by cutting up and re-organising illustrations from Victorian encyclopaedias and novels.

The 184 collages of Une semaine de bonté [A Week of Kindness] were created during the summer of 1933 while Max Ernst was staying at Vigoleno, in northern Italy. The artist took his inspiration from wood engravings, published in popular illustrated novels, natural science journals or 19th century sales catalogues. With infinite care, he cut out the images that interested him and assembled them with such precision as to bring his collage technique to a level of incomparable perfection. Without seeing the original illustrations, it is difficult to work out where Max Ernst intervened. In the end, each collage forms a series of interlinked images to produce extraordinary creatures which evolve in fascinating scenarios and create visionary worlds defying comprehension and any sense of reality.

After La Femme 100 têtes [The Woman with one Hundred Heads] (1929) and Rêve d’une petite fille qui voulut entrer au Carmel [A Little Girl dreams of taking the Veil] (1930), Une semaine de bonté was Max Ernst’s third collage-novel. Ernst had originally intended to publish it in seven volumes associating each book with a day of the week. Moreover, the title referred to the seven days in Genesis. Yet it was also an allusion to the mutual aid association ‘La semaine de la bonté’ [The Week of Kindness], founded in 1927 to promote social welfare. Paris was flooded with posters from the organisation seeking support from everyone. Like the elements making up the collages, the title was also “borrowed” by Max Ernst.

The first four publication deliveries did not, however, achieve the success that had been anticipated. The three remaining ‘days’ were therefore put together into a fifth and final book. The books came out between April and December 1934, each having been bound in a different colour: purple, green, red, blue and yellow. In the final version, two works were taken out. The edition therefore consists of only 182 collages.

Anonymous text from the Musée D’Orsay website [Online] Cited 07/09/2016. No longer available online

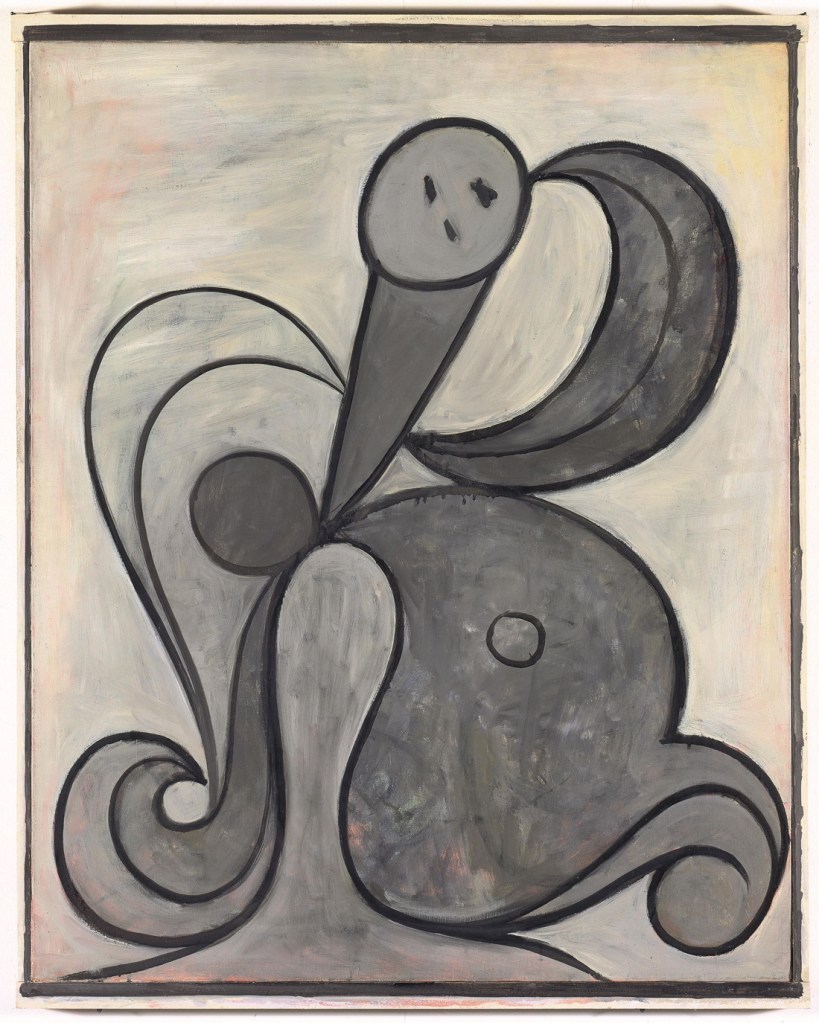

Yves Tanguy (French, 1900-1955)

Sans titre, ou Composition surréaliste (Untitled, or Surrealist Composition)

1927

Oil on canvas

54.5 x 38cm

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg/ Pietzsche Collection

Tanguy’s paintings have a unique, immediately recognisable style of nonrepresentational surrealism. They show vast, abstract landscapes, mostly in a tightly limited palette of colours, only occasionally showing flashes of contrasting colour accents. Typically, these alien landscapes are populated with various abstract shapes, sometimes angular and sharp as shards of glass, sometimes with an intriguingly organic look to them, like giant amoebae suddenly turned to stone.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Dorothea Tanning (American, 1910-2012)

Voltage

1942

Oil on canvas

29 x 30.9cm

Collection: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg/ Pietzsche Collection

Alberto Giacometti (Italian, 1901-1966)

Objet désagréable, à jeter [Disagreeable Object, to be Thrown away]

1931

Wood

19.6 x 31 x 29 cm

Collection: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, purchased 1990

© Bridgeman Art Library

Jean (Hans) Arp (French-German, 1886-1996)

Assis (Seated)

1937

Limestone

29.5 x 44.5 x 16cm

Collection: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg/ Pietzsche Collection

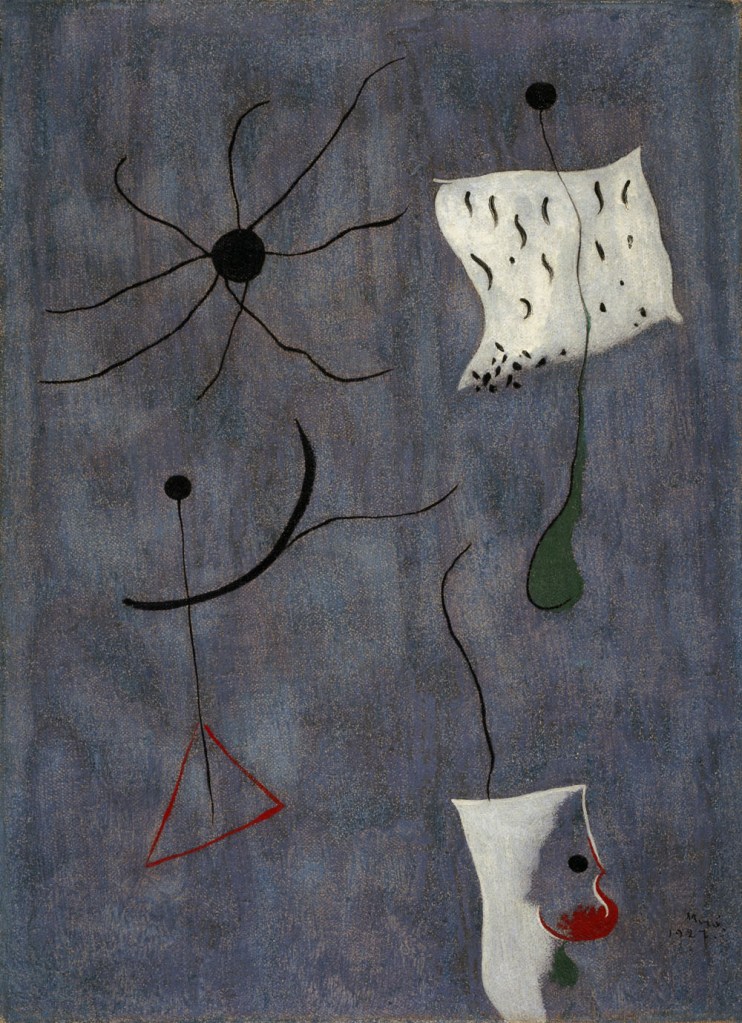

Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893-1983)

Peinture (Painting)

1925

Oil on canvas

130 x 97cm

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg/ Pietzsche Collection

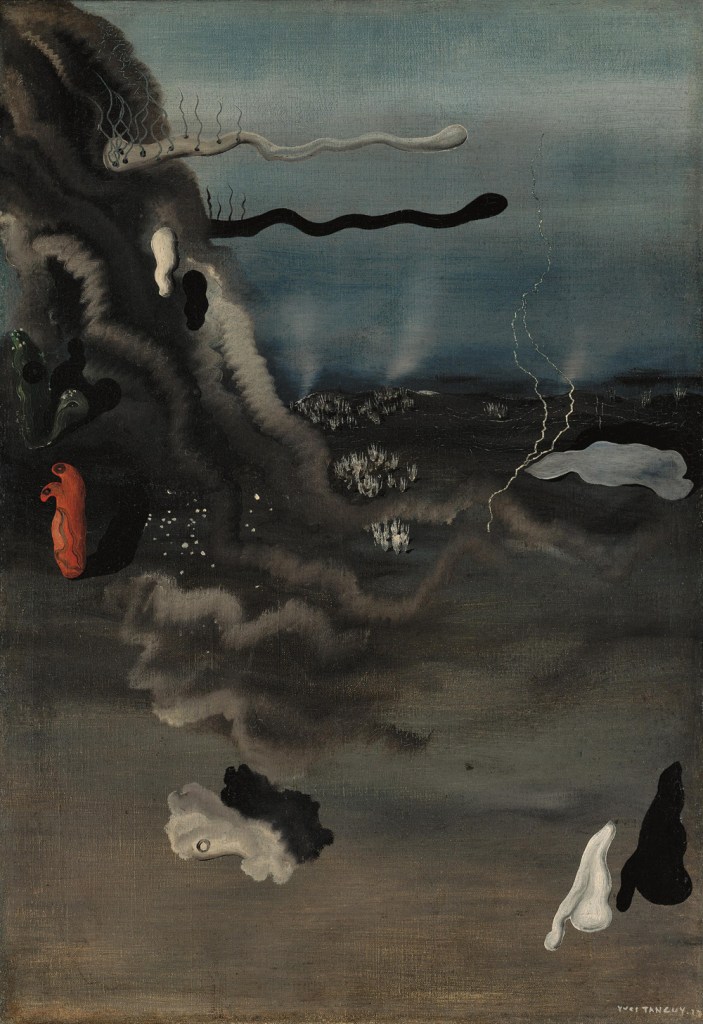

Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893-1983)

Peinture [Painting]

1927

Oil on canvas

33 x 24.1 cm

Collection: National Galleries of Scotland

Bequeathed by Gabrielle Keiller 1995

René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967)

Le Modèle rouge III (The Red Model III)

1937

Oil on canvas

206 x 158 x 5cm

Collection: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (Formerly collection of E. James)

Purchased with the support of The Rembrandt Association (Vereniging Rembrandt), Prins Bernhard Fonds, Erasmusstichting, Stichting Bevordering van Volkskracht Rotterdam Museum Boymans-van Beuningen Foundation 1979

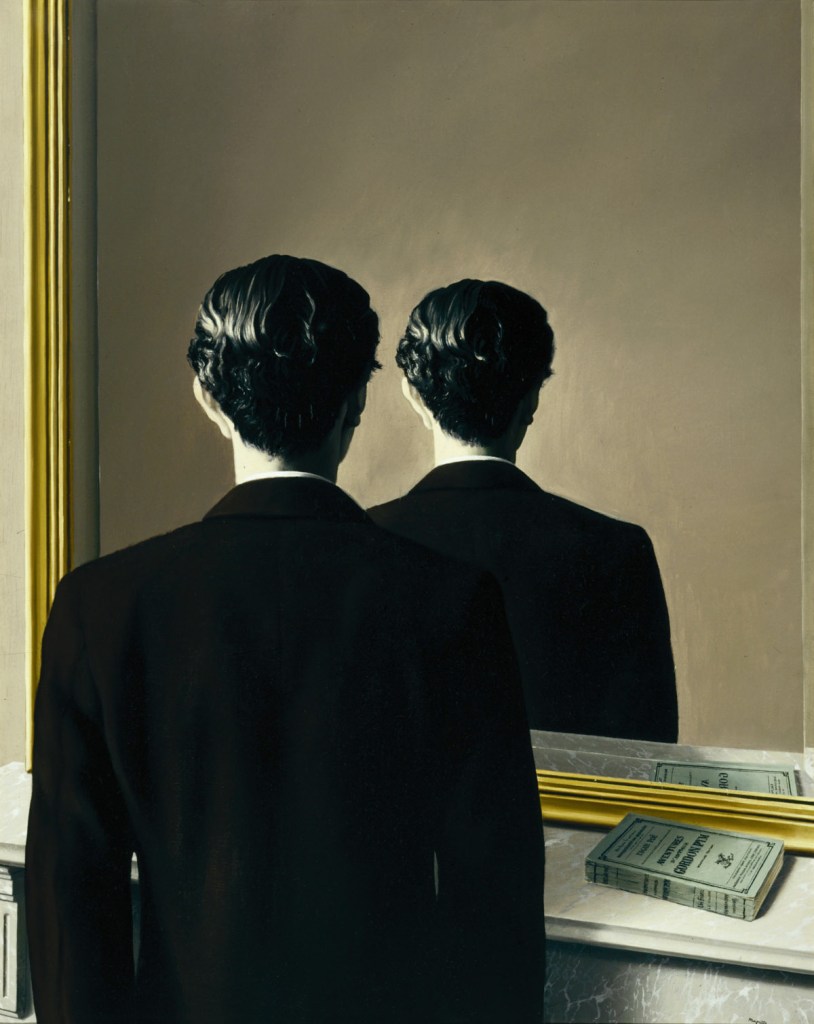

René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967)

La reproduction interdite (Not to be Reproduced)

1937

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

© Beeldrecht Amsterdam 2007

Photographer: Studio Tromp, Rotterdam

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

75 Belford Road

Edinburgh EH4 3DR

Phone: 0131 624 6200

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 6pm

![Francis Picabia (French, 1879-1953) 'Fille née sans mère' [Girl Born without a Mother] c. 1916-1917 from the Collections of Roland Penrose, Edward James, Gabrielle Keiller and Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June- Sept, 2016 Francis Picabia (French, 1879-1953) 'Fille née sans mère' [Girl Born without a Mother] c. 1916-1917 from the Collections of Roland Penrose, Edward James, Gabrielle Keiller and Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June- Sept, 2016](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/francis-picabia-fille-nc3a9e-sans-mc3a8re-web.jpg)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'La Joie de vivre' [The Joy of Life] 1936 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'La Joie de vivre' [The Joy of Life] 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/max-ernst-la-joie-de-vivre-1936-web.jpg)

![Dorothea Tanning (American, 1910-2012) 'Eine Kleine Nachtmusik' [A Little Night Music] 1943 Dorothea Tanning (American, 1910-2012) 'Eine Kleine Nachtmusik' [A Little Night Music] 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/dorothea-tanning-eine-kleine-nachtmusik-1943-web.jpg)

![Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989) 'Couple aux têtes pleines de nuages' [Couple with their Heads Full of Clouds] 1936 Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989) 'Couple aux têtes pleines de nuages' [Couple with their Heads Full of Clouds] 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/salvador-dalc3ad-couple-aux-tc3aates-pleines-de-nuages-web.jpg)

![Alberto Giacometti (Italian, 1901-1966) 'Objet désagréable, à jeter' [Disagreeable Object, to be Thrown away] 1931 Alberto Giacometti (Italian, 1901-1966) 'Objet désagréable, à jeter' [Disagreeable Object, to be Thrown away] 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/alberto-giacometti-objet-dc3a9sagrc3a9able-web.jpg)

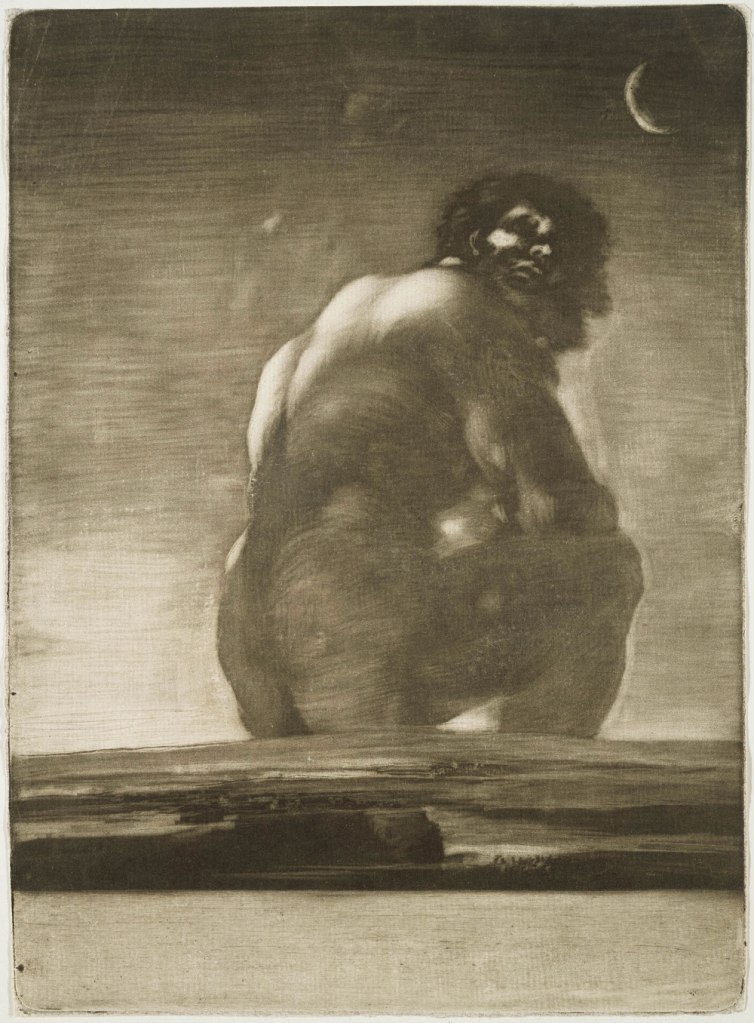

![Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828) 'Raging Lunatic (Loco furioso), Bordeaux Album I, G, 3[4?]' 1824-1828 Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828) 'Raging Lunatic (Loco furioso), Bordeaux Album I, G, 3[4?]' 1824-1828](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/11-raging-lunatic-web.jpg?w=788)

You must be logged in to post a comment.