Exhibition dates: 30th June – 2nd September 2023

Photographers: the exhibition features work by Katalin Arkell, Peter Arkell, Cyril Arapoff, Chris Bethell, A.R. Coster, Firmin, John Galt, David Granick, Bert Hardy, Brian Harris, Hawkins, Nick Hedges, David Hoffman, Tom Learmonth, Steve Lewis, Jack London, Marketa Luskacova, Anthony Luvera, MacGregor, Monty Meth, Douglas Miller, Moyra Peralta, Ray Rising, Reg Sayers, Andrew Scott, Alex Slotzkin, Norah Smyth, Humphrey Spender, Andrew Testa, Paul Trevor, Edith Tudor-Hart, as well as several unknown photographers.

Jack London Collection (American, 1876-1916)

People of the Abyss

1902

© Huntington Library, San Marino, California

1902: a policeman disturbs a rough-sleeping youth in Whitechapel, one of many photographs by the American author Jack London that illustrated his book The People of the Abyss.

Another insightful, socially-minded (ie. actively interested in social welfare or the well-being of society as a whole) exhibition from Four Corners who champion creative expression, education and empowerment and build upon almost 50 years of radical, socially-engaged approaches to photography and film.

“This timely exhibition draws shocking comparisons with today’s housing precarity, high rents and homelessness. From Victorian slums and the first model estates, to the mass postwar council house construction and the subsequent demolition of many tower blocks, it ends with post-Thatcherite gentrification and its impact on affordable housing.” (Press release)

I have included bibliographic information on the artists in the posting where possible.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. For more information on slum photography and urban poverty please see the essay by Sadie Levy Gale. “Exposed,” on the AEON website 21 August 2023 [Online] Cited 31/08/2023

Many thankx to Four Corners for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Jack London (American, 1876-1916)

Homeless people in Itchy Park, Spitalfields

1902

From People of the Abyss

NOTE: Photograph not in the exhibition

Images of housing, homelessness and resistance in London’s East End

Our summer exhibition explores how photographers have represented conditions of housing and homelessness for over a century. From workhouses to slums, damp council flats to Thatcherite gentrification, images reveal the systemic poverty that East Londoners have endured and how the medium of photography has been used to campaign for change. We are delighted to feature new artwork by Anthony Luvera, which addresses economic segregation in Tower Hamlets’ housing developments, a phenomenon known as ‘poor doors’. Created with a forum of local residents, this examines the rise of market-driven ‘affordable’ housing and the state of social housing today.

This exhibition is supported using public funding by the National Lottery through Arts Council England and the National Lottery Heritage Fund. We particularly thank Getty Images Hulton Archive and Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives for their generous contributions which made this exhibition possible. We are grateful for the kind support of Report Digital.

Text from the Four Corners website

Jack London (American, 1876-1916)

View in Hoxton

1902

From People of the Abyss

NOTE: Photograph not in the exhibition

Jack London (American, 1876-1916)

Homeless women in Spitalfields Garden

1902

From People of the Abyss

NOTE: Photograph not in the exhibition

Not many people know that the famous American author Jack London was also a skilled documentary photographer and photojournalist. He took thousands of pictures over the years from the slums of London’s East End to the islands of the South Pacific.

In 1902 Jack London visited his namesake city London where he took pictures of its people and their everyday life. In the book “The People of the Abyss”, London describes this first-hand account by living in the East End (including the Whitechapel District) for several months, sometimes staying in workhouses or sleeping on the streets. The conditions he experienced and wrote about were the same as those endured by an estimated 500,000 of the contemporary London poor.

Even before, Jack London had talked about a book on the London slums with George Brett, one of his publishers. Thus, the writer knew what he was ought to expect ‘down there’: “He meant to expose the underside of imperialism, the degradation of the workers…”. The “evolutionary Socialist” wanted to find “the Black Hole of capitalism”.

With this preconceived vision in his mind, he disguised himself as an American sailor who had lost his ship and went into the East End taking pictures and experiencing their life. To be more precise, he wandered about Whitechapel, Hoxton, Spitalfields, Bethnal Green, and Wapping to the East India Docks. Jack London disguised as one of the working-class poor and pretended to be one of them, which made it easier for him to get to know the conditions of their everyday life. …

In his 1903 “The People of the Abyss”, the American gives this description of the poor Londoners: “the air he breathes, and from which he never escapes, is sufficient to weaken him mentally and physically, so that he becomes unable to compete with the fresh virile life from the country hastening on to London Town… It is incontrovertible that the children grow up into rotten adults, without virility or stamina, a weak-kneed, narrow-chested, listless breed, that crumples up and goes down in the brute struggle for life with the invading hordes from the country.”

Anonymous. “London’s East End life through the lens of Jack London, 1902,” on the Rare Historical Photos website Nd [Online] Cited 04/08/2023

Jack London (American, 1876-1916)

Whitechapel on a bank holiday

1902

From People of the Abyss

NOTE: Photograph not in the exhibition

Jack London (American, 1876-1916)

Frying Pan alley, Spitalfields

1902

From People of the Abyss

NOTE: Photograph not in the exhibition

Norah Smyth (British, 1874-1963)

A Street in Bow

1914

© Paul Isolani-Smyth

1914: residents of a street in Bow, photographed by the activist and suffragette Norah Smyth. A street in Bow in 1914 where the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS) took care of children during the first world war. Smyth documented children in Bow through a series of intimate street photographs.

Norah Smyth

Smyth, a suffragette, socialist and pioneering female photographer was a founding member of the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS) and right-hand woman to Sylvia Pankhurst, who set up the federation in 1914.

Her years of activism included a spell as a prominent member of the Communist Workers’ Party (CWP) during the 1920’s. Her active participation in the international socialist movement came to an end with the dissolution of the CWP. After twelve years in the East End of London, it was time to move on. Smyth decided to join brother Maxwell in Florence, where she took up a post at the British Institute.

Jane McChrystal. “The adventures of Norah Smyth: her life as a suffragette, philanthropist and artist,” on the Roman Road LDN website 22 March 2023 [Online] Cited 04/08/2023

Anonymous photographer

Shadwell Family

1920

© Topical Press Agency, Hulton Archive, Getty Images

1920: a poverty-stricken family make a meal from a loaf of bread in Shadwell, traditionally an area of slum housing where the population lived in closely packed tenements.

Exhibition reveals East End’s history of poor housing and homelessness

Opening at Four Corners Gallery this month, Conditions of Living: Home and Homelessness in London’s East End takes a visual journey from workhouses to slums, damp tower blocks to homeless shelters, exploring how photographers have represented these conditions for over a century. It sheds light on little-known histories: the tenants’ rent strikes of the 1930s, post-war squatting, and ‘bonfire corner’, a meeting place for homeless people at Spitalfields Market for more than twenty years.

This timely exhibition draws shocking comparisons with today’s housing precarity, high rents and homelessness. From Victorian slums and the first model estates, to the mass postwar council house construction and the subsequent demolition of many tower blocks, it ends with post-Thatcherite gentrification and its impact on affordable housing.

The exhibition features new work by the artist Anthony Luvera, which addresses the rise of economic segregation in recent housing developments across Tower Hamlets, a phenomenon commonly known as ‘poor doors’. Also titled Conditions of Living, this socially engaged artwork by Luvera is built upon extensive research into the social, political, and economic contexts behind the rise of market-driven ‘affordable’ housing provision and the state of social housing today, and is created in collaboration with a community forum of local residents who live in the buildings themselves. This new work builds upon Luvera’s twenty-year career dedicated to working collaboratively with people who have experienced homelessness, and addressing issues of housing precarity and housing justice.

Anthony Luvera says: ‘London is one of the world’s last major cities still to ban the practice of allowing property developers to build ‘poor doors’, despite proclamations by successive governments and mayors about stopping the appalling practice. My work with people experiencing homelessness began twenty years ago in Spitalfields. To be back in Tower Hamlets creating this new work about economic segregation in housing developments and the broken social housing system feels urgent, especially at a time when the costs of living crisis has sunk its claws into the lives of ordinary working people.’

Carla Mitchell, Artistic Director at Four Corners says: ‘this is a highly relevant exhibition, given the extortionate London rents which create forms of social cleansing for long established local communities. We were inspired by Four Corners’ own building, which was a Salvation Army working men’s hostel.’

Four Corners

We are a cultural centre for film and photography, based in East London for fifty years. Our exhibitions explore unknown social histories that might not otherwise be told.

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives

THLHLA holds outstanding resources for the study of the history of London’s East End. Run by the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, collections cover the areas of Bethnal Green, Poplar and Stepney. Explore the changing landscape and lived experiences of individuals and communities in Tower Hamlets through original documents, images and reference books.

Press release from Four Corners

Edith Tudor-Hart (British born Austria, 1908-1973)

Stepney family

1932

© The Estate of W. Suschitzky

1932: portrait of an impoverished family in Stepney. Edith Tudor-Hart was one of the most significant documentary photographers of the period. Closely affiliated with the Communist party, she recorded the conditions of the working class.

Edith Tudor-Hart

Edith Tudor-Hart, née Suschitzky, was one of the most significant documentary photographers working in Britain in the 1930s and 1940s. Born in Vienna, she grew up in radical Jewish circles. Edith married Alex Tudor-Hart, a British doctor, and the pair moved to England. There she worked as a documentary photographer, closely associated with the Communist Party, compiling a remarkable archive of images of working people in London and later, the south of Wales. Although still active in the 1950s, the difficulties of finding work as a woman photographer led eventually to Tudor-Hart abandoning photography altogether.

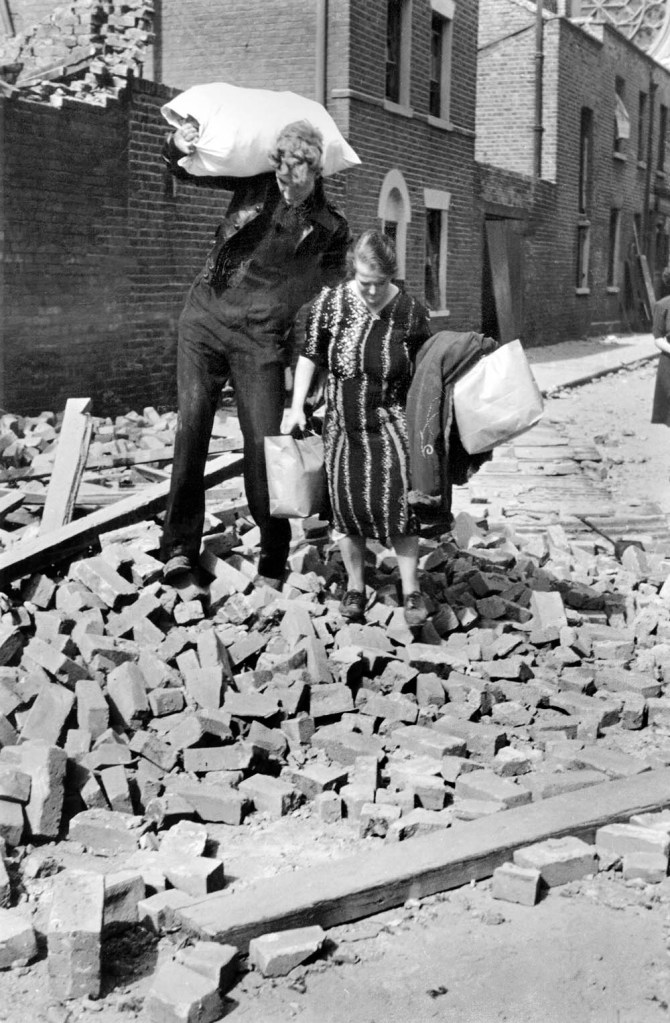

Bert Hardy (British, 1913-1995)

Bombed East End

1940

© Bert Hardy, Picture Post, Getty Images

1940: a couple carry their salvaged belongings after bomb damage to their home, photographed by photojournalist Bert Hardy, best known for his work for Picture Post

Bert Hardy

If one photographer sums up the spirit and sheer brilliance of the seminal British newsweekly Picture Post, it is Bert Hardy (1913-1995). Alongside Bill Brandt and Don McCullin, former Victoria & Albert curator Mark Haworth-Booth regarded Hardy as one of the three greatest British photojournalists from the genre’s Golden Age. Indeed, Hardy stands alongside Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa and Werner Bischoff as the giants of 20th-century photography.

London born and entirely self-taught, Hardy was one of the UK’s first professionals to embrace the 35mm Leica in favour of a traditional large-format press camera. The smaller camera and faster film suited his instinctual shooting style and allowed him to consistently create something unique even in high-pressure situations. His confidence and courage enabled him to produce some of the most memorable images of the Blitz and postwar England and Europe. An inspiration to a generation of photojournalists, Hardy was often greeted as warmly by his subjects as he was by his peers – so much so one dubbed him the ‘professional Cockney’.

Anonymous. “Bert Hardy,” on the Getty Images Gallery website Nd [Online] Cited 04/08/2023

Monty Meth (British, 1926-2021)

New Houses

1951

© Monty Meth, Topical Press Agency, Hulton Archive, Getty Images

1951: workers stand on the ruins of Trinity church in Poplar, which was destroyed during the Blitz, and overlook new housing built in the wake of slum clearances.

Monty Meth

Monty was born above a barber’s shop in Bethnal Green, east London, the youngest of three sons of Millie Epstein, a domestic servant, and Max Meth, a Czech Jewish immigrant who found intermittent work as a bread roundsman and tailor.

Educated at the local Mansford St Central school, Monty learned photography at the Cambridge and Bethnal Green boys’ club, which he credited with rescuing him from teenage pilfering, and at 14 went to work as a messenger for the Fleet Street picture agency Photopress, then on to the Topical Press agency. He returned after second world war service in the Navy to become a prize-winning photographer and photojournalist.

Martin Adeney. “Monty Meth obituary,” on The Guardian website Sun 28 Mar 2021 [Online] Cited 03/08/2023

David Granick (British, 1912-1980)

Stifford Estate

1961

Retouched by Chris Dorley-Brown

© Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives

1961: the now demolished Stifford Estate in Tower Hamlets, built in the late 1950s to replace slum housing, and comprised of three 17-storey tower blocks. Photographed by lifelong Stepney resident David Granick, who recorded the East End pre-gentrification.

David Granick

David Granick (1912-1980) was a photographer who lived in the East End his whole life. His colour slides laid untouched until 2017 when a local photographer, Chris Dorley-Brown, examined them at Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives. These images capture the post-war streets of Stepney, Whitechapel, Spitalfields and beyond in the warm hues of Kodachrome film at a time when black and white photography was the norm.

David Granick was born in 1912 and lived his whole life in Stepney. A Jew, a keen photographer and a long-serving member of the East London History Society, he gave lectures on various local history themes illustrated with colour slides taken by himself or his fellow members of the Stepney Camera Club. Bequeathed to Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives after his death in 1980, where they have been preserved ever since, these photographs show the East End on the cusp of social change.

The London East End In Colour 1960-1980 David Granick 2019 Hoxton Mini Press

David Granick (British, 1912-1980)

Spitalfields Market

1973

Photo restoration by Chris Dorley-Brown

© Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives

David Hoffman (British, b. 1946)

Houses Stand Empty

1973

© David Hoffman

Photojournalist David Hoffman has spent more than 40 years photographing the happenings on the streets of London, with a particular focus on his East End hometown, and with his lens predominantly focused on those less fortunate than most.

His subjects have included the homeless, the addicted, and the enraged, and spanned slums, shelters, and the streets, in good spirits and bad.

‘Really, my work is about oppression,’ he explains, ‘It’s not about class, but how people’s lives are constrained and shaped by society. And that’s most visible at the bottom of society. You and I are constrained, too, but in far less, and far less damaging, ways.’ Besides, he adds, ‘No one’s going to get a feature published on how the middle class is having a tough time.’

What defines his work, Hoffman says, is that ‘I’m always looking for extremes.’

Hoffman’s first photographic training came from a course at the University of York, where, with Chris Steele-Perkins, he set up a Student Union-sponsored darkroom. Steele-Perkins went on to work for Magnum Photos and become their president. In contrast, after two years Hoffman ‘slung the course in at the same time that they slung me’.

He moved back to London in 1969, to the East End in 1970, and worked ‘rubbish jobs’ to support his photography.

‘I did van driving and jobs like that. I would work to save up money, and then take time off to do photography (until my money ran out).’ A polytechnic course helped: ‘It was a poor course and taught me nothing but I had three years being supported on grants so I could really put some effort into my photography’, and squatting ‘meant that I didn’t have to spend my time working to raise the rent and could build my photography into a survivable income.’

Amy Freeborn. “David Hoffman: chaos, riots, slums and the East End,” on the Roman Road LDN website 27 November 2014 [Online] Cited 04/08/2023

Marketa Luskacova (Czech, b. 1944)

Homeless men, Spitalfields

1975

© Markéta Luskačová

1975: homeless men in Spitalfields, photographed by the Czech documentarist Markéta Luskačová.

Marketa Luskacova

Marketa Luskacova’s work is marked by her own lived experiences. Themes like cultural identity and social behaviour are at the core of her candid photographs. Born in Prague in 1944 during the communist regime, Luskacova graduated from Charles University with a degree in Sociology in 1967 and studied Photography at FAMU (1967-1969). Around this time, she began to take photographs as a means to document local traditions in some of the poorest communities of Slovakia.

She moved to London in 1975, where she continued her career as a photographer. She began to document her surroundings, producing captivating portraits of everyday life in some of the least privileged areas of the city. She felt particularly drawn towards the cultural atmosphere of Brick Lane and Spitalfields street markets, where she used to buy her own groceries.

‘I was poor and I needed to do my shopping there as it was the cheapest place to buy things. I could identify with the people in Brick Lane because they were immigrants and they were in need of cheap goods. Once I had done my shopping, I would leave my bag with a stall holder while I took my photographs.’

In her series London Street Markets, Luskacova documents daily life in the city, capturing powerful and emphatic portraits of its people and their traditions and offering a glimpse into the diverse cultural fabric of London East End’s society in the seventies.

‘I don’t go to Brick Lane regularly anymore, sometimes six months pass between one visit and another … I photographed what I saw there and what I thought it was good to record, be it a face or a smile, an animal or a shoe. I believe in the evidential quality of photography, and I know that unless things are done in a visually interesting way they are not remembered.’

Anonymous. “Artist Profile: Marketa Luskacova,” on the Arts Council Collection website Nd [Online] Cited 04/08/2023

Tom Learmonth (British, b. 1955)

Usher Rd Bow, Tower Hamlets

1976

© Tom Learmonth

1976: children play on rubble on waste ground on Usher Road, Tower Hamlets.

Tom Learmonth

Born in Liverpool but brought up in England, Wales, India and Australia, he studied on the first BA degree in photographic arts in the UK, at the Polytechnic of Central London. “There I developed a social and political view of what photography could and should do,” he says. “My work concentrated on the community in the East End of London. After graduating I worked in community photography projects in the East End and freelanced as a photojournalist in the wide sense of the word; I wrote as well as photographed.”

Tom Learmonth (British, b. 1955)

Mrs Baldwin, Mansford Street Estate, Bethnal Green

1978

© Tom Learmonth

1978: Mrs Baldwin on the balcony of her flat on the Mansford Street Estate, Bethnal Green. The estate of more than 700 homes was built over 20 years from 1957.

Andrew Testa (English, b. 1965)

Bailiffs move along rooftops towards protesters as they evict Claremont Road on the route of the M11 motorway

1994

© Andrew Testa

1994: bailiffs move along rooftops towards protesters as they evict occupants of Claremont Road on the route of the M11 motorway, prior to the demolition of the houses.

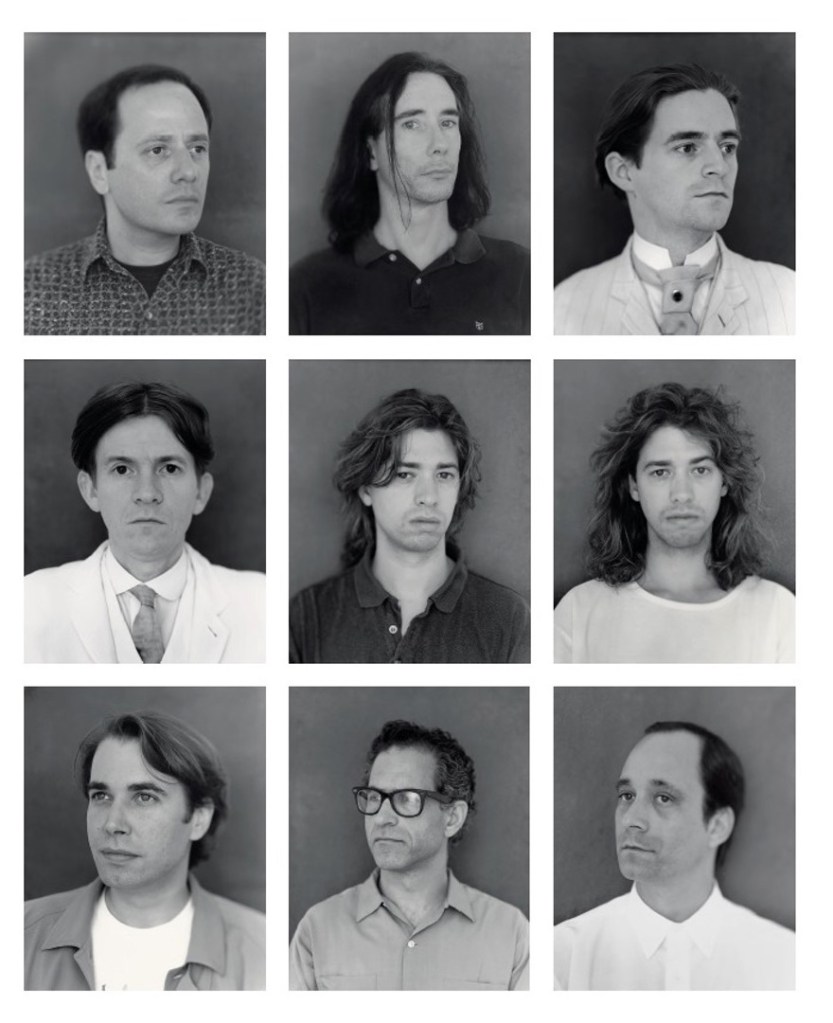

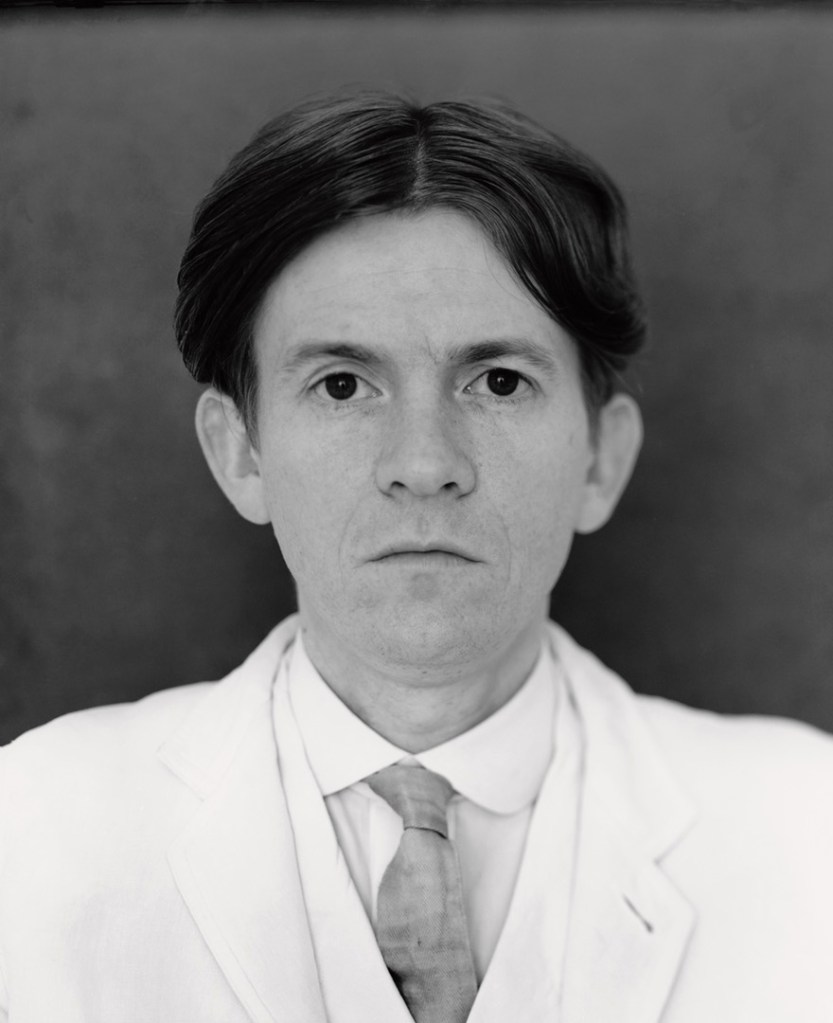

Anthony Luvera (Australian, b. 1974)

Assisted Self-Portrait of Ruben Torosyan

2004

© Anthony Luvera

2004: assisted self-portrait of Ruben Torosyan by Anthony Luvera. Luvera started the project in 2001, helping homeless people to document their lives and experiences.

Anthony Luvera

Anthony Luvera (born 1974) is an Australian artist, writer and educator, living in London. He is a socially engaged artist who works with photography on collaborative projects, which have included working with those who have experienced homelessness and LGBT+ people. Luvera is an Associate Professor of Photography at Coventry University… Luvera has worked extensively with people who have experienced homelessness. Many of these projects use his “assisted self-portrait” methodology, where the subject of the photograph, assisted by Luvera, makes and selects the pictures.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits

Photographs

I had never wanted to photograph homeless people before. I’d read the (de)constructive writings by photo critics on ‘others’, poverty and representation. I knew about the complexities of the find-a-bum school of photography trounced by Martha Rosler. So in December 2001, when it was put to me by a friend to get involved as a photographer at Crisis Open Christmas, the annual event for homeless people in London, the invitation threw me. “I’d much prefer to see what the people I met would photograph.”

Over the following months, the conversation with my friend about photography and homelessness bounced louder in the back of my head. I became extremely interested in how homeless people have been represented and in questions about the process of representation itself. To what degree could the apparently fixed proximities between photographer, subject and camera be dismantled and reconfigured? How could a ‘subject’ become actively involved in the creation of a representation? What use, if any, would all this serve in the meanings offered in the final presentation?

I sourced 1,000 cameras and processing vouchers, and spent every day and many late nights at the following Crisis Open Christmas…

Between 25 and 40 people dropped in to each following weekly session. Around a big communal table, we gathered to look at the photos, to show and tell the stories held in the images, and to drink endless cups of tea. The sessions were high-energy, swarming with vibrant personalities. The youngest participant was 19 and the oldest was nearing 90. Different people got involved for different reasons. Some wanted to make snapshots of their special times, favourite places, friends and family. While others had ideas about art and concepts to explore with photography. I explained how to use the cameras and listened to each participant’s ambitions, encouraging everyone to simply go and do it. I never brought along photography books or showed my own photographs, nor did I tell any of the participants how or what to photograph. When looking at the photographs I asked each participant to pull out their favourites, or the images that best represented what they wanted to show. With permission I took scans of these photographs and held the negatives in a file. Release forms and licenses were provided, written especially for the project by specialist intellectual property copyright lawyers. Permission was not always given, which was always completely respected.

I never asked why anybody was homeless. Though over time stories came out with the photographs. In the four years the sessions have taken place I have worked with over 250 people. Every person I’ve met has a very different and particular story to tell. Some are entirely abject, while others are remarkable for their ordinariness. All are compelling in their own way. And while there may be commonalities between the experiences of particular individuals, not one situation of any participant could be seen as being broadly representative of the cause or experience of homelessness.

Ruben Torosyan

Ruben Torosyan left Georgia in the late 1980’s when the country was still under harsh Soviet rule. Not issued a birth certificate and unable to get a passport, Ruben was determined to get to the capitalist West to create a better life for himself. He spent over five years traveling across Europe attempting to obtain political asylum in over 15 different countries. In every place he was unsuccessful, largely for the same bureaucratic reasons, boiling down to the incredible fact that Ruben has absolutely no official way of proving who he is or where he comes from. In Spain Ruben smuggled himself on to a shipping freight container. Squished in with bottles and bags for his excrement, and packets of biscuits to eat, he travelled for 35 nights in complete darkness to get to New York. After failing to get legal rights to remain there, and escaping detainment, he struggled on the streets of Brooklyn in conditions worse than back home in Georgia. After two years, determined not to go back to Georgia, Ruben did the same shipping container trip to Ireland to get to London, where shortly after we met.

Ruben came to the sessions with a very clear idea about what he wanted to use the cameras to photograph in making his contribution to the archive; the discrepancy between what he expected London to be and what, in his experience, it actually was. Ruben’s depictions of dirty, litter strewn streets (serendipitously replete with the newspaper headline, “I Feel Used”), a naked man with mental health issues running down the road, people begging and a poor woman walking by without shoes, are for him, depictions of the filthy, hostile, brutal and ugly place that is London. Where there is “no mercy and the food is rubbish”.

Anthony Luvera. “Photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits,” in Source, Issue 47 2006 published on the Anthony Luvera website [Online] Cited 03/08/2023 (with permission of the author)

Four Corners

121 Roman Road, Bethnal Green,

London E2 0QN

Nearest tube: Bethnal Green, Central Line

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Saturday 11am – 6pm

Thursday 11am – 8pm (July and on 31 Aug)

You must be logged in to post a comment.