Exhibition dates: 26th June – 9th August, 2015

Curators: Rebekka Reuter and Fabian Knierim

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series Presa di coscienza sulla natura / Awareness of Nature

Italy, Senigallia

1980

Mario Gaicomelli has a unique signature as an artist. His photographs could never be anyone else’s work.

The press release states, “His works, all of them conceived as series, combine elements of reportage with lyrical subjectivity and a symbolic aesthetic which seems almost calligraphic in its harsh contrasts between black and white… On the one hand, they express a personal feeling; on the other, they embody a clear, courageous and conceptually groundbreaking attitude.” It continues, “His singular style caused him to remain beyond photographic fashions. In the five decades of his work, he created a body of work that is unparalleled in its aesthetic and thematic consistency.”

To remain beyond photographic fashions. In other words, he didn’t fit in, he was an outsider, he was Other. He did not conform.

He crafted, and I use the word deliberately, a conceptual response to life and landscape, to memory and existence – his symbolic aesthetic – that also expresses an enormous respect for personal feeling, for the stuff of life. There is a consistency to his enquiry, both aesthetically and thematically, that marks him out from the pack.

The calligraphic nature of his work has links back to his training as a printer. The aerial photographs of the landscape from the series Presa di coscienza sulla natura / Awareness of Nature (below) possess the quality of an etching. Mix in an dash of surrealism, such as in the series Verrà la morte e avrà i Tuoi Occhi / Death will come and have your eyes (below)1 and the macabre, as in the series Slaughterhouse, and you have a potent mix of portrayal of the irreality of everyday life. Some photographs, such as an image below from the series Scanno Italy, Scanno even posses the 3D quality of stereoscopic cards.

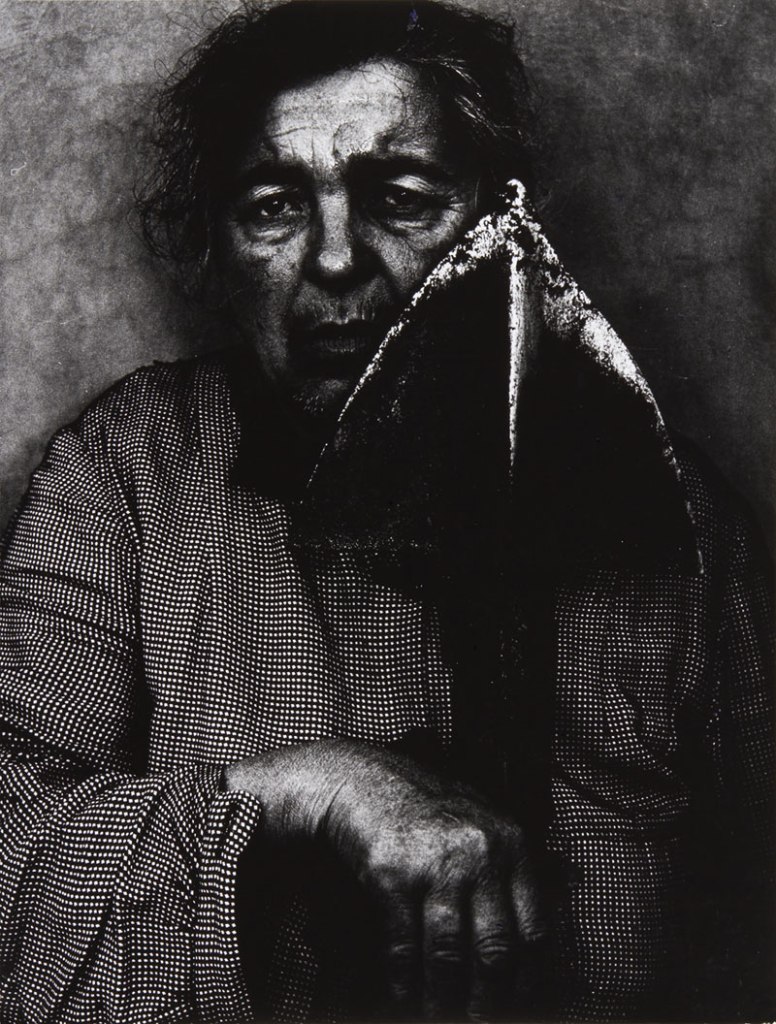

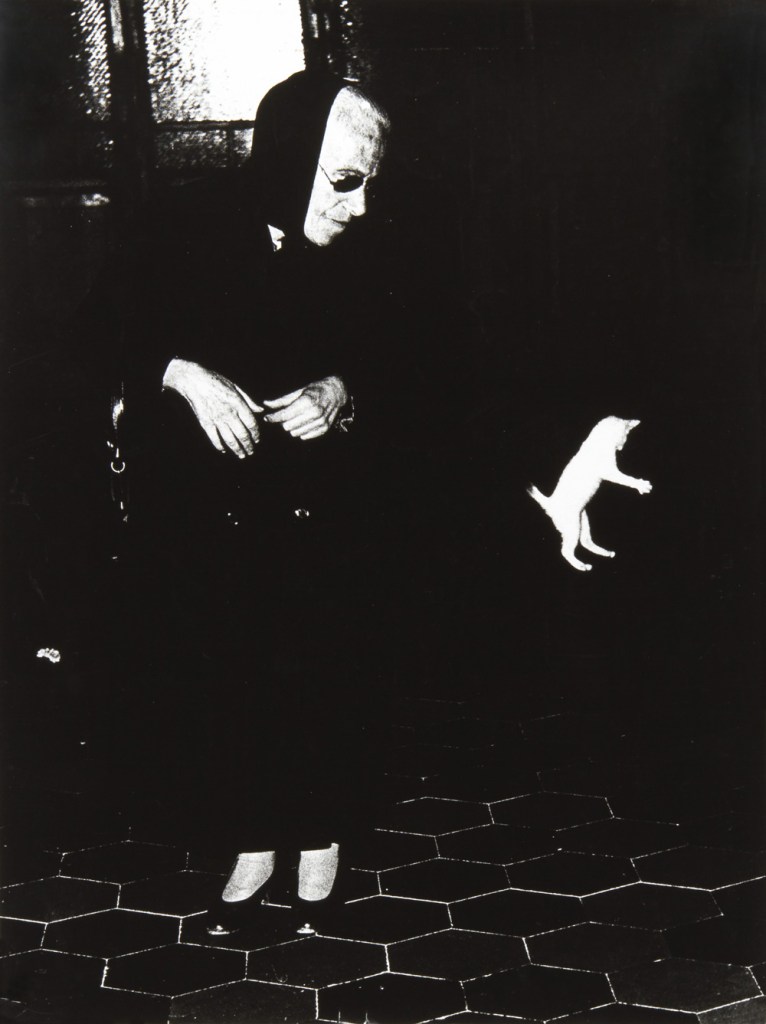

Above all, there is a sense of the mysteries of life contained within the spaces of his work. Is the white cat flying in mid-air or is clinging to someone that we can’t see, who has been printed out by the photographer because of his previsualisation of the work. What is that shape hovering next to his mother? I think it looks like a moth, and the mother is a Japanese mother after Hiroshima with a withered hand. She almost looks like she is dressed in a kimono as well. We’re not supposed to know what that is – actually it’s Agfa paper, hardest possible grade, and skilled use of bleach by the artist – and that is the mystery. Its an interesting print because it is printed so that it could be any gender.

I do love artists who push the boundaries of the sensual and the symbolic. Praise be to traces of differences.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ See the case of Christine Papin and Léa Papin who were two French maids who murdered their employer’s wife and daughter in Le Mans, France, on 2 February 1933. They had both been beaten to the point of being unrecognisable, and one of the daughter’s eyes was on the floor nearby. Madame Lancelin’s eyes had been gouged out and were found in the folds of the scarf around her neck.

Many thankx to Fotomuseum WestLicht for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series Presa di coscienza sulla natura / Awareness of Nature

Italy, Senigallia

c. 1987

Italian Neorealism (Neorealismo)

Italian Neorealism came about as World War II ended and Benito Mussolini’s government fell, causing the Italian film industry to lose its center. Neorealism was a sign of cultural change and social progress inItaly. Its films presented contemporary stories and ideas, and were often shot in the streets because the Cinecittà film studios had been damaged significantly during the war.

The neorealist style was developed by a circle of film critics that revolved around the magazine Cinema, including Luchino Visconti, Gianni Puccini, Cesare Zavattini, Giuseppe De Santis and Pietro Ingrao. Largely prevented from writing about politics (the editor-in-chief of the magazine was Vittorio Mussolini, son of Benito Mussolini), the critics attacked the white telephone films that dominated the industry at the time. As a counter to the popular mainstream films some critics felt that Italian cinema should turn to the realist writers from the turn of the 20th century.

Both Antonioni and Visconti had worked closely with Jean Renoir. In addition, many of the filmmakers involved in neorealism developed their skills working on calligraphist films (though the short-lived movement was markedly different from neorealism). Elements of neorealism are also found in the films of Alessandro Blasetti and the documentary-style films of Francesco De Robertis. Two of the most significant precursors of neorealism are Toni (Renoir, 1935) and 1860 (Blasetti, 1934). In the Spring of 1945, Mussolini was executed and Italy was liberated from German occupation. This period, known as the “Italian Spring,” was a break from old ways and an entrance to a more realistic approach when making films. Italian cinema went from utilising elaborate studio sets to shooting on location in the countryside and city streets in the realist style.

The first neorealist film is generally thought to be Ossessione by Luchino Visconti (1943). Neorealism became famous globally in 1946 with Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City, when it won the Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival as the first major film produced in Italy after the war…

The films are generally filmed with nonprofessional actors – although, in a number of cases, well known actors were cast in leading roles, playing strongly against their normal character types in front of a background populated by local people rather than extras brought in for the film. They are shot almost exclusively on location, mostly in run-down cities as well as rural areas due to its forming during the post-war era.

The topic involves the idea of what it is like to live among the poor and the lower working class. The focus is on a simple social order of survival in rural, everyday life. Performances are mostly constructed from scenes of people performing fairly mundane and quotidian activities, devoid of the self-consciousness that amateur acting usually entails. Neorealist films often feature children in major roles, though their characters are frequently more observational than participatory…

The period between 1943 and 1950 in the history of Italian cinema is dominated by the impact of neorealism, which is properly defined as a moment or a trend in Italian film, rather than an actual school or group of theoretically motivated and like-minded directors and scriptwriters. Its impact nevertheless has been enormous, not only on Italian film but also on French New Wave cinema, the Polish Film School and ultimately on films all over the world.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series The Good Earth, Italy

c. 1965

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series Presa di coscienza sulla natura / Awareness of Nature

Italy, Senigallia

1982-1992

The images by Mario Giacomelli (1925-2000), one of the most well-known Italian photographers of the post-war period, are distinctive and possessed of an almost painful intensity. Inspired by Neorealismo cinema, Giacomelli, a typesetter and printer by training who had been experimenting with painting and literature, turned to photography during the 1950s, developing a highly individual visual idiom characterised by graphic abstraction. His works, all of them conceived as series, combine elements of reportage with lyrical subjectivity and a symbolic aesthetic which seems almost calligraphic in its harsh contrasts between black and white.

Starting with the people and landscape of his native central Italy, Giacomelli’s pictures always deal with the fundamental questions of existence: life and death, faith and love, the relationship of man and his roots, the traces of time. One of his most well-known images shows a group of young priests in their cassocks dancing a round in the snow – a moment of innocence already inscribed with loss. Giacomelli’s images of the farm land around his native town of Senigallia, taken from an airplane, dissolve the fields into picturesque networks of lines, showing the landscape as a product of human toil and the passing of time. On the one hand, they express a personal feeling; on the other, they embody a clear, courageous and conceptually groundbreaking attitude.

The photographs on display are part of the Photography Collection OstLicht, curated by Rebekka Reuter and Fabian Knierim.

Text from the Fotomuseum WestLicht website

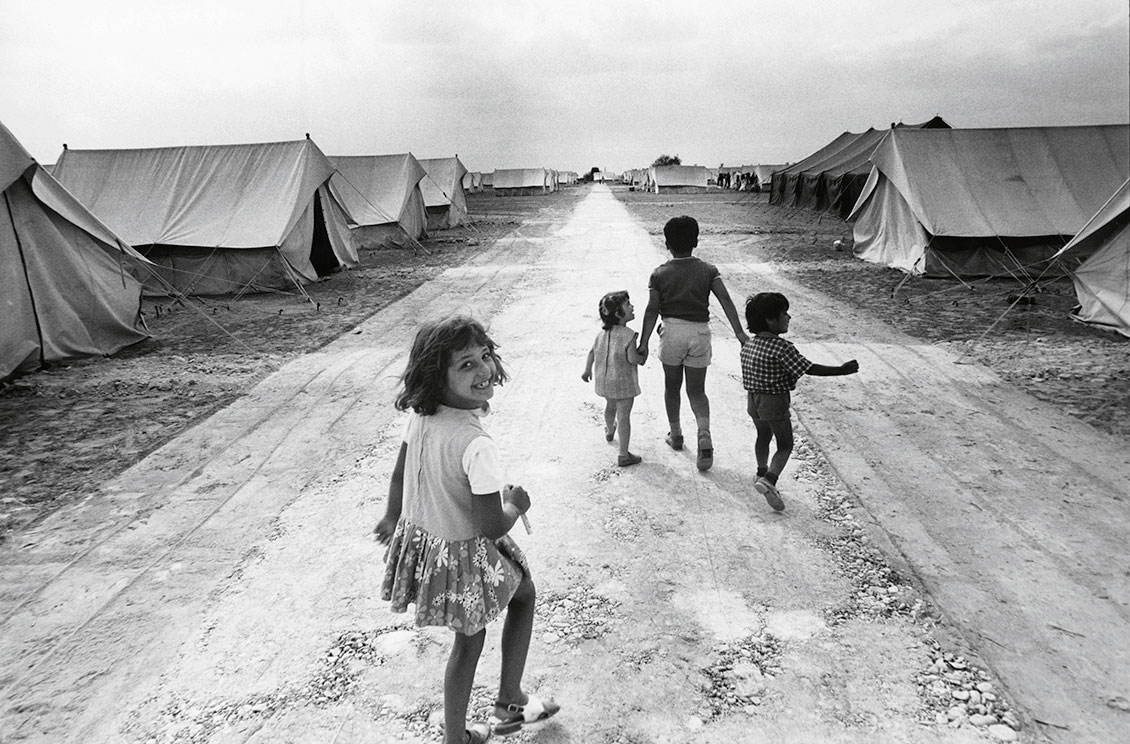

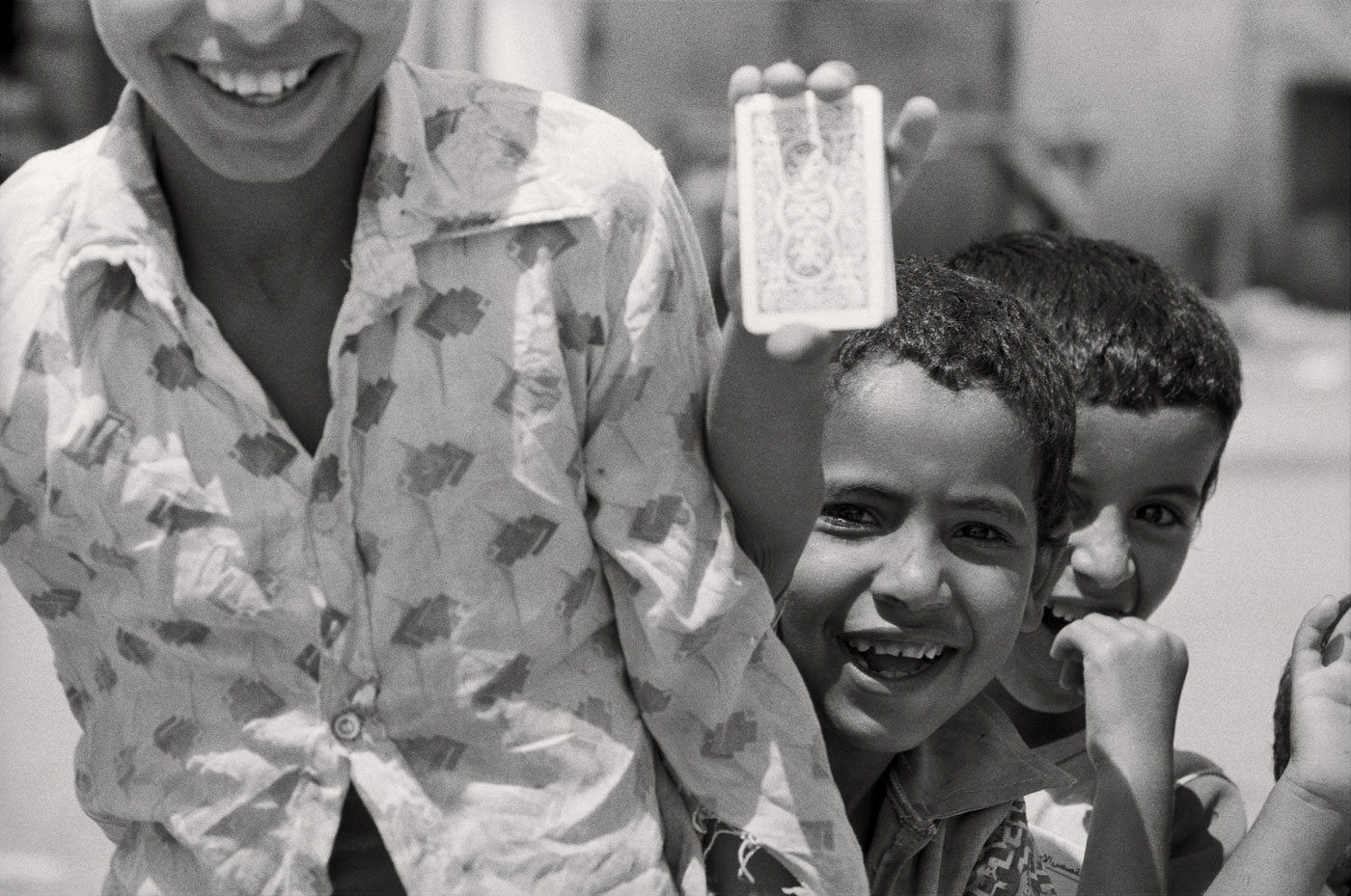

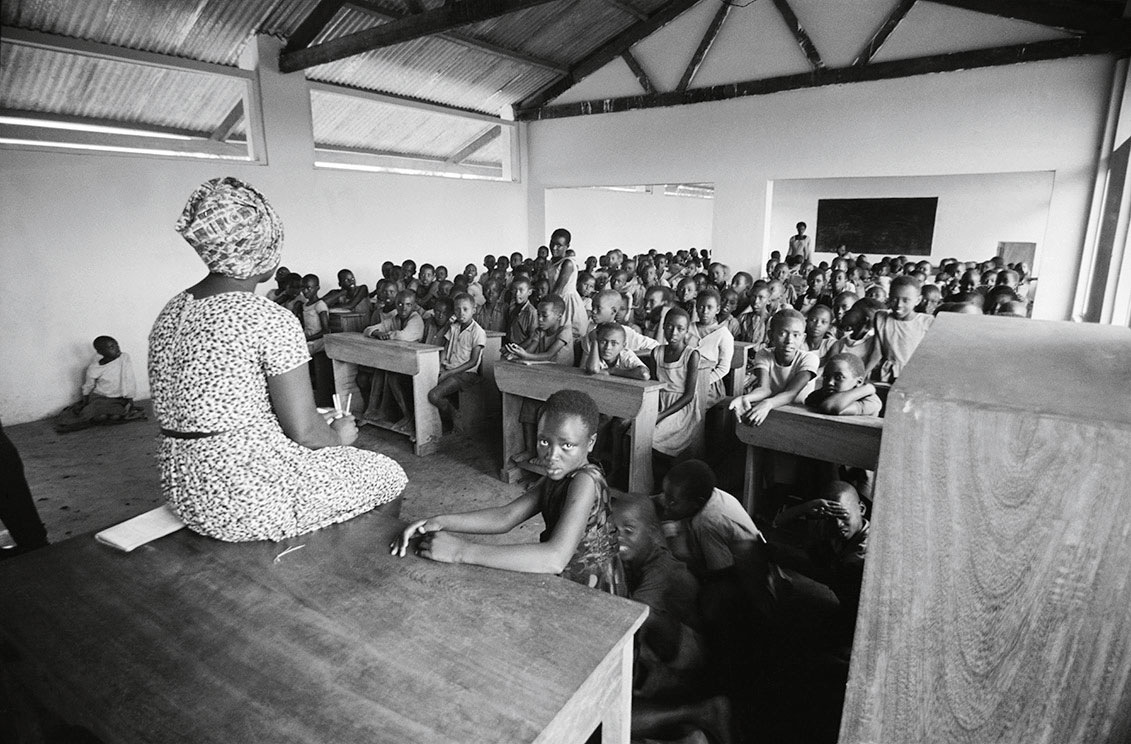

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series Puglia Italy, Puglia

1958

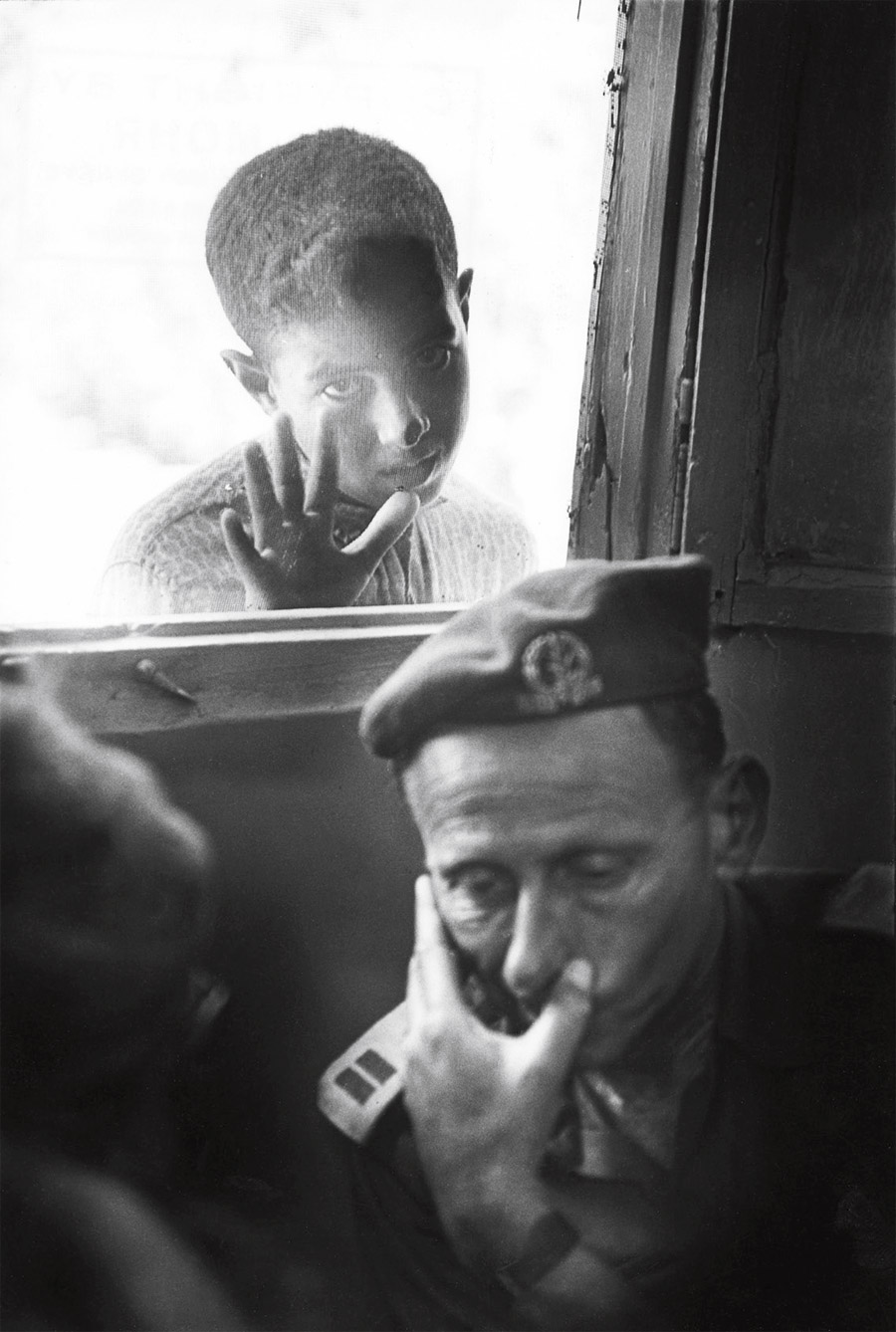

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series Scanno Italy, Scanno

1959

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series Lourdes France, Lourdes

1966

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto / I have no Hands to caress my face

Italy, Senigallia

1961-1963

Among his most famous designs include the photographs of the series Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il Volto (I have no hands that caress my face, after a poem by David Maria Turoldo), 1961-63. Giacomelli observed in a group of priest candidates at their boisterous games and silliness between the seriousness of the lessons. An image showing the young clergy, as they dance in their cassocks a dance in the snow – a moment of innocence, the loss already acknowledged. The soil is so that the seminarians seem to float as black silhouettes on nothing in the recording of a pure white surface without any drawing.

At the end of the 1950s Giacomelli photographed the street scenes of Puglia and Scanno. Both series show a largely untouched by modernity village community. The archaic rural life that still has a clearly vital undertone in Puglia (1958), turns into the black-clad figures of Scanno (1957-1959), an image of gloomy Providence.

Over several years, from 1954 to 1983, Giacomelli returned to the nursing home where his mother had worked in the days of his childhood, to photograph there. As in all his series he took, even with Verrà la morte e avrà i Tuoi Occhi (Death will come and will have your eyes on a poem by Cesare Pavese), Giacomelli builds a relationship to the place and its people. The recordings are marked by a harsh realism of human decay, the white of the deductions seem to exhaust the fragile body which possesses an almost existential quality. Simultaneously Giacomelli’s identification with the residents and his silent anger at the suffering is obvious and so the ancients always remain hidden in his eyes.

Giacomelli’s shots from the plane of farmland of his birthplace Senigallia, finally resolve the fields in picturesque interwoven lines and show the landscape as a drawn from the people and time. On one hand, an expression of a personal feeling, these images embody at the same time a clear, bold and pioneering conceptual attitude. Giacomelli’s art is always a rebellion against the impositions of human existence. The bitter irony of the transience of life, he meets by means of photography. His singular style caused him to remain beyond photographic fashions. In the five decades of his work, he created a body of work that is unparalleled in its aesthetic and thematic consistency.”

Mario Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli was born in 1925 in Senigallia. The small town on the Italian Adriatic coast in the province of Ancona remained until his death in 2000, the centre of his life. Giacomelli grew up in poverty. His father he lost before he was nine years old, his mother worked as a laundress in a retirement home. At thirteen, he left school and began an apprenticeship as a printer. With a partner, he opened after the war in Senigallia his own printing business. Inspired by photography magazines and the neo-realist film, he discovered at the beginning of the 1950s photography for himself and bought his first camera. He successfully participated in a number of photo contests and regional exhibitions. He received an important impetus in this period by Giuseppe Cavalli, with whom he founded the Photo Group Misa in 1954. In the same year he began his work on Verrà la morte. In 1957 he undertook trips to Scanno and Lourdes, from which emerged the first images of the same series. International presentations of his photographs – the Subjective Photography 3 exhibition, 1959 organised by Otto Steinert in Brussels, at Photokina in Cologne, or the George Eastman House, Rochester (both 1963) – made Giacomelli known beyond Italy. An exhibition curated by John Szarkowski at MoMA in New York meant an international breakthrough for Giacomelli 1964.

Translated from the German press release

Installation views of the exhibition Mario Giacomelli. Against Time at Fotomuseum WestLicht

© WestLicht / Sandro E. E. Zanzinger

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series Slaughterhouse

Italy 1961

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

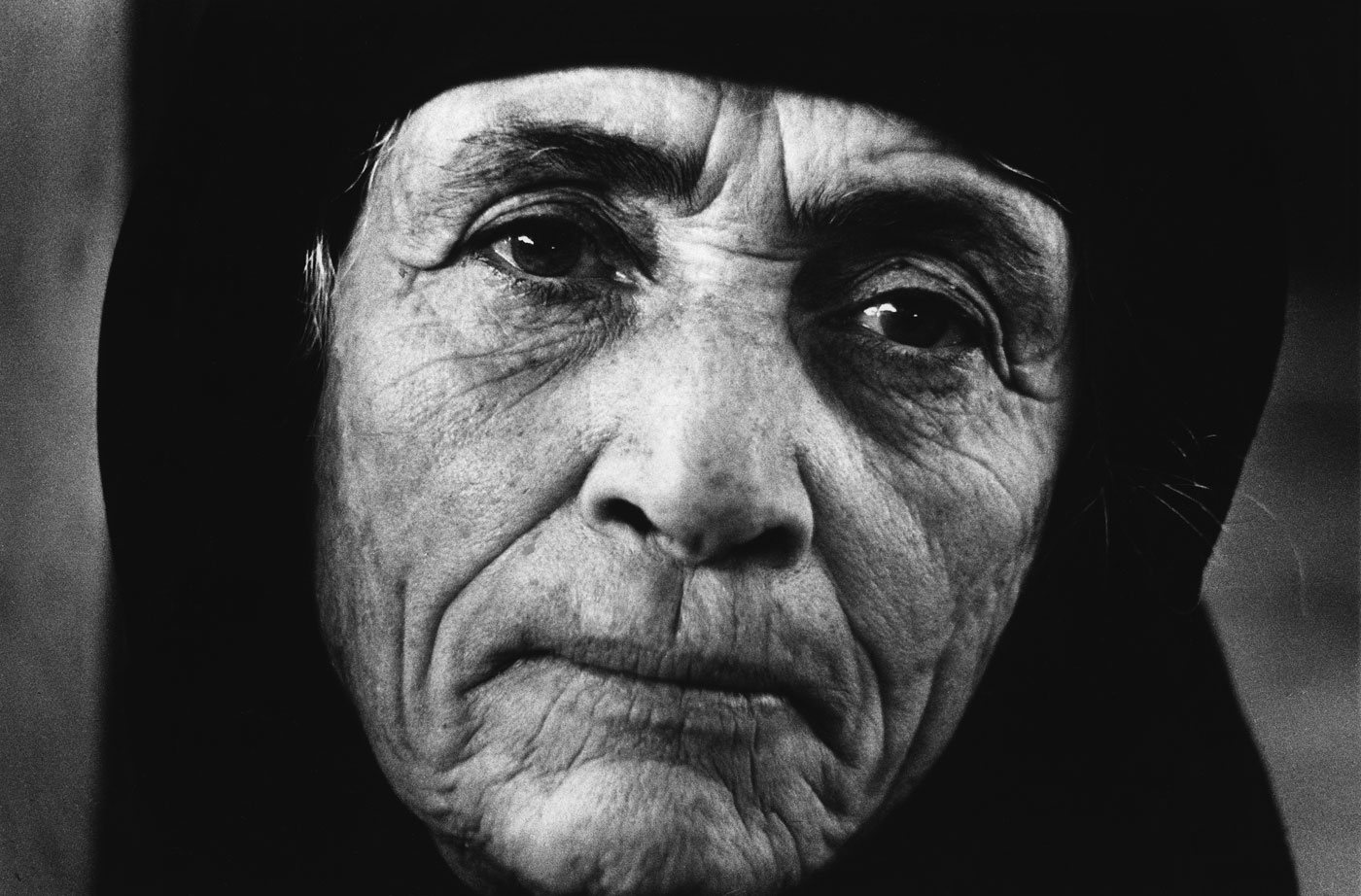

From the series: Verrà la morte e avrà i Tuoi Occhi / Death will come and have your eyes

Italy 1954

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Mia Madre / Mother

Italy 1959

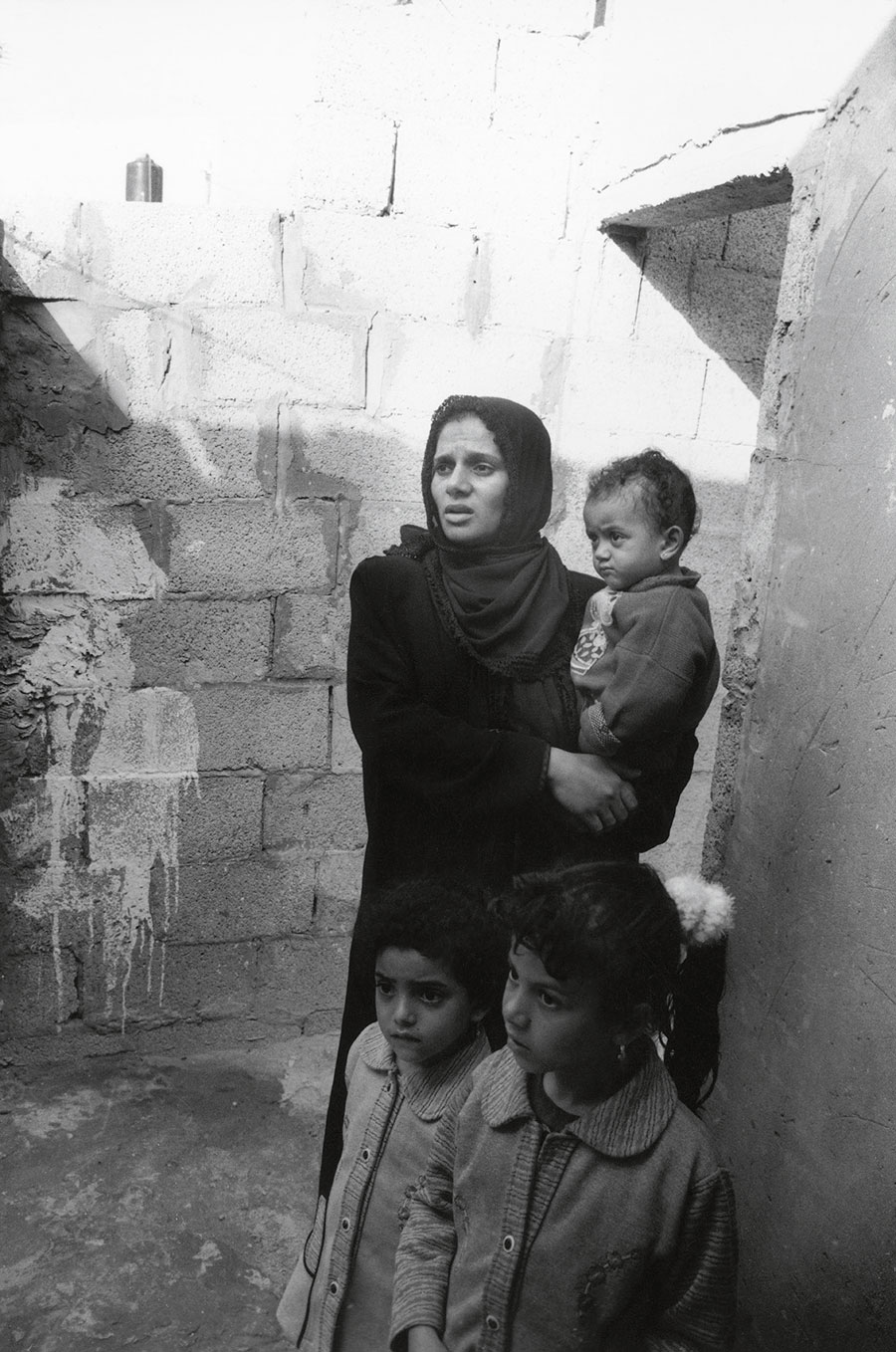

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

From the series: Verrà la morte e i Tuoi Occhi avrà / Death will come and your have eyes

Italy, 1955-1958

WestLicht

Westbahnstraße 40

A-1070 Vienna

Opening hours:

Tue, Wed, Fri 2 – 7pm

Thu 2 – 9pm

Sat, Sun 11am – 7pm

Mon closed

You must be logged in to post a comment.