Exhibition dates: 21st November, 2024 – 5th May, 2025

Curators: Yasufumi Nakamori, former Senior Curator of International Art (Photography) Tate Modern, Helen Little, Curator, British Art, Tate Britain and Jasmine Chohan, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain with additional curatorial support from Bilal Akkouche, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern; Sade Sarumi, Curatorial Assistant, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain and Bethany Husband, Exhibitions Assistant, Tate Britain

List of artists: Keith Arnatt; Zarina Bhimji; Derek Bishton; Sutapa Biswas; Tessa Boffin; Marc Boothe; Victor Burgin; Vanley Burke; Pogus Caesar; Thomas Joshua Cooper; John Davies; Poulomi Desai; Al-An deSouza; Willie Doherty; Jason Evans; Rotimi Fani-Kayode; Anna Fox; Simon Foxton; Armet Francis; Peter Fraser; Melanie Friend; Paul Graham; Ken Grant; Joy Gregory; Sunil Gupta; John Harris; Lyle Ashton Harris; David Hoffman; Brian Homer; Colin Jones; Mumtaz Karimjee; Roshini Kempadoo; Peter Kennard; Chris Killip; Karen Knorr; Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen; Grace Lau; Dave Lewis; Markéta Luskačová; David Mansell; Jenny Matthews; Don McCullin; Roy Mehta; Peter Mitchell; Dennis Morris; Maggie Murray; Tish Murtha; Joanne O’Brien; Zak Ové; Martin Parr; Ingrid Pollard; Brenda Prince; Samena Rana; John Reardon; Paul Reas; Olivier Richon; Suzanne Roden; Franklyn Rodgers; Paul Seawright; Syd Shelton; Jem Southam; Jo Spence; John Sturrock; Maud Sulter; Homer Sykes; Mitra Tabrizian; Wolfgang Tillmans; Paul Trevor; Maxine Walker; Albert Watson; Tom Wood; Ajamu X.

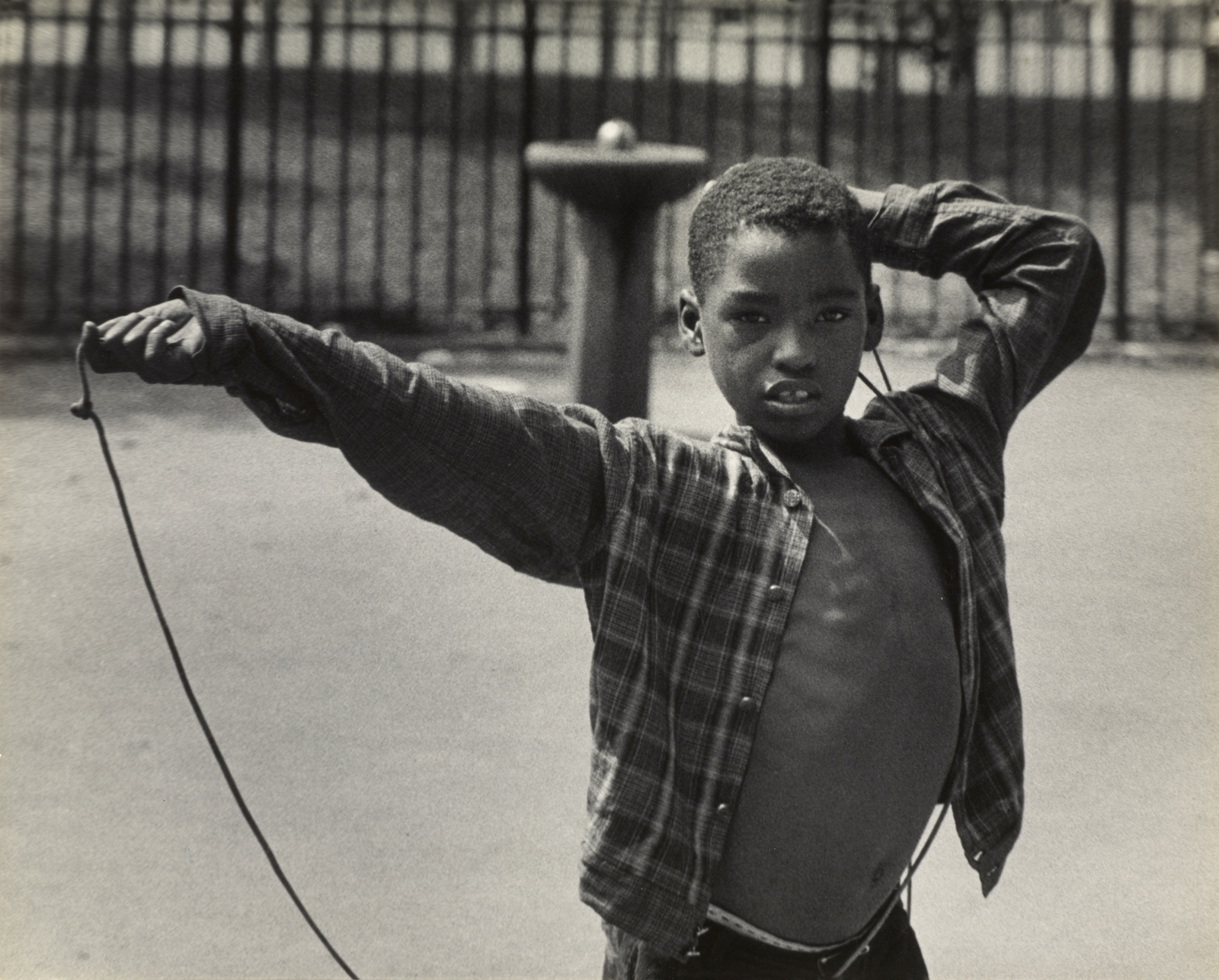

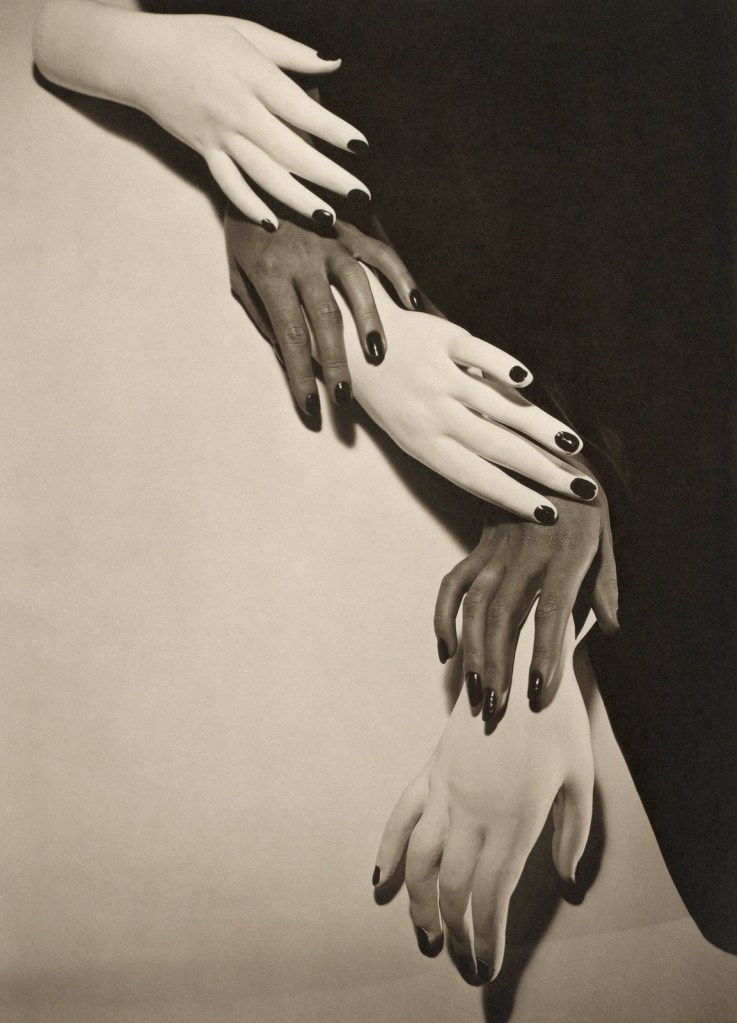

Jason Evans (Welsh, b. 1968) and Simon Foxton (British, b. 1961)

Untitled

1991

From the series Strictly

Tate

© Jason Evans

A humungous posting that, much like the exhibition itself, cannot do justice to the photographs and issues of an entire decade – the flow on effects of which are still being felt today.

From distant Australia and having not seen the exhibition myself, I cannot do justice – now there is an apposite word for the decade – to the flow of the exhibition, the many included or neglected artists involved or not, the bodies of work displayed or their commentary on the many disparate, competing and complex political, economic and social cataclysms (def: a sudden violent political or social upheaval) of the decade: including but not limited to, race, gender, identity, representation, activism, neoliberalism, Thatcher, The Miners’ Strike, Clause 28, HIV/AIDS, feminism, racism, class, patriarchy, money, greed, hedonism, humanism, subcultures, unemployment, strikes, poverty, luxury, consumer culture, war (Falklands) and riots, for example the Brixton riots of 1981.

I lived those years in the UK before emigrating to Australia in 1986. What I remember is the terrible weather, the cold and the damp, the vile Thatcher, and the poor quality of living. I lived in Stockwell (or Saint Ockwell as we used to call it) near Brixton in the early 80s before moving to Shepherd’s Bush were all the Mods gathered on their scooters on the roundabout as part of the mod revival.

I worked at a fish and chip restaurant called Geales just off Notting Hill Gate working double shifts, 10.30 – 3pm, 5.30 – 12, five days a week. The restaurant served fish and chips with French champagne and wines. The mostly gay floor staff were paid a pittance but we earnt our money off the tips we received from the celebrities that inhabited the place, people such as Bill Connolly, John Cleese, Divine and Kenny Everett. They loved us gay boys.

We worked hard and partied harder, often going out from Friday night to Sunday night to the clubs with a rest day on Monday. We were young. We ran from place to place living at a hundred miles an hour, not realising the ruts in London are very deep and you were spending as much as you made just to pay the rent, to eat at dive cafe (I lived on Mars bars, fish and chips, braised heart, mashed potatoes and bullet peas to name a few and I was as thin as a rake), and to go out partying, to have fun, visiting the alternative clubs in Kings Cross, Vauxhall, Brixton and the East End.

And then there was the spectre of HIV/AIDS raising its ugly head. I had my first HIV test in 1983. I had my blood taken and I went back 2 weeks later for the result. I sat outside the doctor’s room and if they called you in and said you had it, you were dead. To look death in the face at 25. The was no treatment. I survived but many of my friends, both here and in Australia, didn’t. We partied harder.

There are so many perspectives on the 80s that it is an impossible task for one exhibition to cover all of the issues. Reviews have noted that the exhibition is “a meandering look at pomp, protest” (Guardian); “exhaustive and exhausting… [the exhibition] makes for a dogged viewing experience that confuses as much as it enlightens” (Guardian); “a sense of fatigue and depletion as it went on and on … it could have been more engaging, more pleasurable” (1000 Words); and “the critical reception of the show has been rather lukewarm” (The Brooklyn Rail).

Most writer’s observe that the exhibition illuminates the way photography shifts “from monochrome to colour, from photojournalism to a more detached style of documentary” featuring “constructed, studio-based and appropriationist work.” The exhibition distils “the curatorial thrust of this sprawling exhibition, which, as its subtitle suggests, is more about photography’s often conceptually based responses to the 1980s than the turbulent nature of the decade itself.”1

Further, Bartolomeo Sala observes that the meandering view of the 1980s is consistent with the curatorial approach to the exhibition, “that is, to present eighties Britain not as a ossified relic but rather a container of multitudes, a country animated by competing, clashing energies and defying coherent description in a way that feels very reminiscent of today. A neoliberal hellhole, a nightmare of petit bourgeois conformity and cheapness, and at the same time an increasingly tolerant, multicultural, and open society, which finds its motor and pride in diversity and the endless project of self-fashioning.”2

Forty plus years on we are still paying the price for Thatcher’s neoliberal hellhole, with the loss of community, and the lack of compassion and empathy for others. I often think it was a more vibrant, more alive time in the 1980s despite all of its inherent problems. While we may have become a more tolerant, multicultural society, fascism and the right, disenfranchisement and loss of rights lurk ever closer to the surface. While we have pride we also have arrogance and self-aggrandisement, self-entitlement. While then we seemingly had freedom and love we now have surveillance and control. In some ways then I disagree with today being a more “open” society.

What social documentary and conceptual photography pictured so strongly and conscientiously in 1980s Britain was the vibrant madness of the age. The passions and the prejudices. Half your luck that you go and see this exhibition in London, that you have a chance to breathe in these photographs, for in Australia the chance of seeing such an exhibition of photographs from the 1980s by a state or national gallery would be zero.

I wouldn’t complain too much!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Sean O’Hagan. “The 80s: Photographing Britain review – in your face and to the barricades,” on The Guardian website, Sun 24 Nov 2024 [Online] Cited 02/05/2025

2/ Bartolomeo Sala. “The 80s: Photographing Britain,” on The Brooklyn Rail website March 2025 [Online] Cited 03/04/2025

Many thankx to Tate Britain for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation view of the exhibition The 80s: Photographing Britain at Tate Britain, London showing at left, the work of Jason Evans and Simon Foxton from the series Strictly 1991 (below); and at centre left top, Wolfgang Tillmans’ Love (Hands in Air) 1989 (below)

Courtesy of Tate Britain

Installation view of the exhibition The 80s: Photographing Britain at Tate Britain, London showing at rear, photographs from Maud Sulter’s series Zabat 1989

Courtesy of Tate Britain

Maud Sulter produced the Zabat series for Rochdale Art Gallery in 1989, the 150th anniversary of the invention of photography. It was a direct response to the lack of a black presence at other celebratory events and exhibitions. Here we see the conventions of Victorian portrait photography under the command of a black woman photographer. The backdrop, props and pose are all retained but the image is transformed with African clothes, non-European objects and, most importantly, by the resolute black woman at its centre.

The title ‘Zabat’ also signifies Maud Sulter’s call for a repositioning of black women in the history of photography: the word describes an ancient ritual dance performed by women on occasions of power.

Text from the V&A website

Installation view of the exhibition The 80s: Photographing Britain at Tate Britain, London showing at left the work of Paul Graham

Courtesy of Tate Britain

Installation view of the exhibition The 80s: Photographing Britain at Tate Britain, London

Courtesy of Tate Britain

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Love (Hands in Air)

1989

“Depending on where you stood in terms of race, gender, or class, the 1980s would seem a time of unprecedented economic expansion, an era defined by the triumph of consumerism and a particularly brass form of hedonism, or else an era of widening disparities, rising unemployment, and generalized economic crisis; a time defined by the booming of the housing market or the return of homelessness; a time of general disaffection and disillusionment toward the prospects of organized politics or an era defined by political activism and struggle, often hyperlocal in nature, as well as successive waves of discontent that at different points rocked the nation. …

In general, the critical reception of the show has been rather lukewarm. Many broadsheet commentators have lamented the meandering nature of the exhibition, while one critic noted the programmatic downplaying of the decade’s heavy-hitters. (Don McCullin and Chris Killip get a handful of photographs each, while virtuoso of political photomontage Peter Kennard is relegated to display cases.) Such assessments feel a little unfair and condescending to the excellent artists who do get a good showing, and in any case this curatorial approach is consistent with the intention of the exhibition – that is, to present eighties Britain not as a ossified relic but rather a container of multitudes, a country animated by competing, clashing energies and defying coherent description in a way that feels very reminiscent of today. A neoliberal hellhole, a nightmare of petit bourgeois conformity and cheapness, and at the same time an increasingly tolerant, multicultural, and open society, which finds its motor and pride in diversity and the endless project of self-fashioning.”

Bartolomeo Sala. “The 80s: Photographing Britain,” on The Brooklyn Rail website March 2025 [Online] Cited 03/04/2025

Derek Bishton, Brian Homer and John Reardon

Ting A Ling, Handsworth Self Portraits project

1979

© Derek Bishton, Brian Homer & John Reardon

Syd Shelton (British, b. 1947)

Skinheads, Petticoat Lane, East London

1979, printed 2012

Gelatin silver print on paper

417 x 281 mm

Tate

Gift Eric and Louise Franck London Collection 2016

Skinheads, known for their shaved heads and heavy boots, emerged as a working-class subculture in the 1960s. Initially non-political, some became associated with extreme nationalism. Others took an anti-racist position aligned with two-tone, a musical movement blending Jamaican ska and British punk. One of Syd Shelton’s photographs shows two members of Skins Against the Nazis proudly displaying a Rock Against Racism badge. The other was taken after an argument about racism. ‘I saw the guy at the front clenching his fists’, notes Shelton, ‘so I took the shot, said thanks and legged it as fast as I could.’

Wall text from the exhibition

Syd Shelton (British, b. 1947)

Anti-racist Skinheads, Hackney, London

1979, printed 2012

Gelatin silver print on paper

417 x 282 mm

Tate

Gift Eric and Louise Franck London Collection 2016

In 1977, 500 National Front (NF) members attempted to march through Lewisham, an area in southeast London with a significant Black population. Thousands ignored a police blockade to hold a peaceful counter-demonstration that led to the NF abandoning their march. Protestors clashed with police and were met by riot shields, baton charges and mounted officers. The events became known as the Battle of Lewisham. Shelton’s photographs contrast the chaos of the streets with the resolve of the protestors. ‘Politics was one of the reasons that I became a photographer’, notes Shelton, ‘the idea of the objective photographer is nonsense.’

Wall text from the exhibition

Syd Shelton (British, b. 1947)

Darcus Howe addressing the anti-racist demonstrators, Lewisham, 13 August 1977

Dated 1977, printed 2020

Tate

Presented by the artist 2021

© Syd Shelton

Explore one of the UK’s most critical decades, the 1980s. This exhibition traces the work of a diverse community of photographers, collectives and publications – creating radical responses to the turbulent Thatcher years. Set against the backdrop of race uprisings, the miner strikes, section 28, the AIDS pandemic and gentrification – be inspired by stories of protest and change.

At the time, photography was used as a tool for social change, political activism, and artistic and photographic experiments. See powerful images that gave voice and visibility to underrepresented groups in society. This includes work depicting the Black arts movement, queer experience, South Asian diaspora and the representation of women in photography.

This exhibition examines how photography collectives and publications highlighted these often-unseen stories, featured in innovative photography journals such as Ten.8 and Cameraworks. It will also look at the development of Autograph ABP, Half Moon Photography Workshop, and Hackney Flashers.

Visitors will go behind the lens to trace the remarkable transformation of photography in Britain and its impact on art and the world.

Text from the Tate Britain website

The 80s: Photographing Britain

David Preshaah and Helen Little curator of The 80s: Photographing Britain at Tate Britian discuss the show running 21st November, 2024 – 5th May, 2025. See powerful images that gave voice and visibility to underrepresented groups in society. This includes work depicting the Black arts movement, queer experience, South Asian diaspora and the representation of women in photography

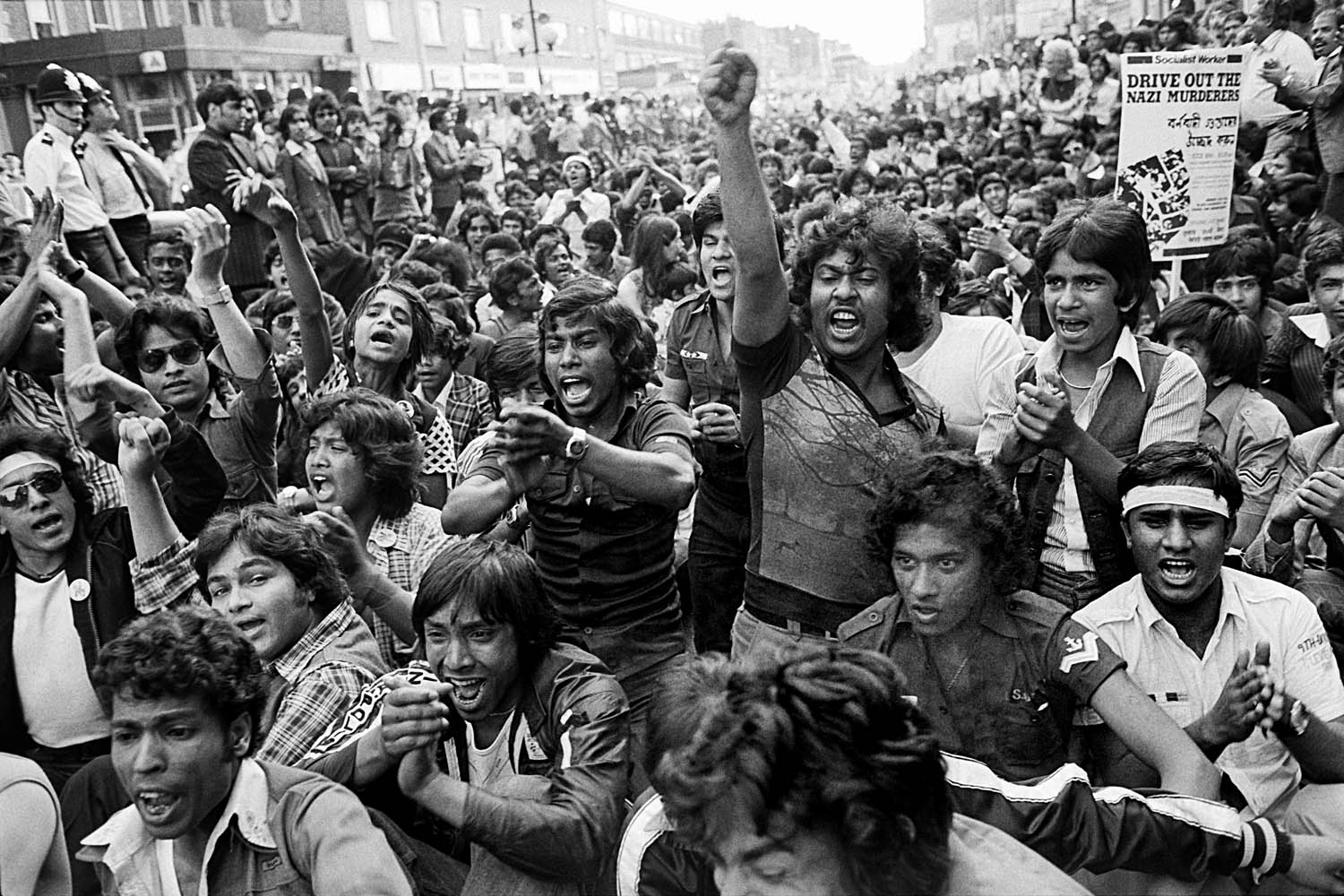

Paul Trevor (British, b. 1947)

Outside police station, Bethnal Green Road, London E2, 17 July 1978. Sit down protest

1978

Paul Trevor © 2023

On 4 May 1978, Altab Ali, a 24-year-old Bangladeshi textile worker, was murdered in a racially motivated attack. During police interviews, the three teenagers responsible casually described the regularity of their racist violence. The Bangladeshi community in east London mobilised in response. 7,000 people marched from Bethnal Green’s Brick Lane to Downing Street, following a vehicle carrying Ali’s coffin. Protestors rallied in Hyde Park chanting, ‘Who killed Altab Ali? Racism, racism!’

Paul Trevor was a member of Half Moon Photography Workshop and helped produce Camerawork magazine. He contributed to an issue on the 1978 Battle of Lewisham in southeast London. While photographing the violent clashes between police and anti-fascist protestors, Trevor recalls, ‘A woman – appealing for help – shouted at me in desperation “What are you taking pictures for?” Good question, impossible to answer in that melee.’ The special issue of Camerawork, ‘What are you taking pictures for?’ was devoted to that question.

Wall text from the exhibition

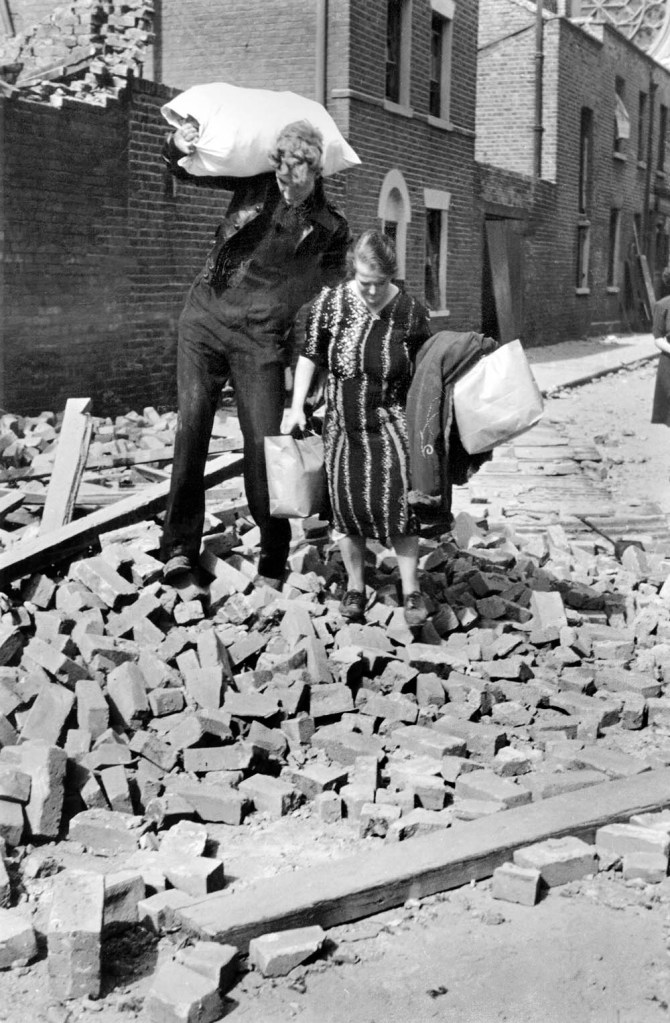

Don McCullin (British, b. 1935)

Jean, Whitechapel, London

Late 1970s

Gelatin silver print

Tate

Gift Eric and Louise Franck London Collection 2011

Photojournalist and war photographer Don McCullin spent nearly twenty years photographing people living on the streets of Aldgate and Whitechapel in east London. He documented people living at the edge of the city’s wealthy financial centre. In the late 1970s, unprofitable psychiatric institutions in the area had begun to close, leaving many residents homeless. These photographs of Jean show how closely McCullin worked with the people he photographed. Of his British social documentary work, McCullin notes: ‘Many people send me letters in England saying “I want to be a war photographer”, and I say, go out into the community you live in. There’s wars going on out there, you don’t have to go halfway around the world.’

Wall text from the exhibition

This autumn, Tate Britain will present The 80s: Photographing Britain, a landmark survey which will consider the decade as a pivotal moment for the medium of photography. Bringing together nearly 350 images and archive materials from the period, the exhibition will explore how photographers used the camera to respond to the seismic social, political, and economic shifts around them. Through their lenses, the show will consider how the medium became a tool for social representation, cultural celebration and artistic expression throughout this significant and highly creative period for photography.

This exhibition will be the largest to survey photography’s development in the UK in the 1980s to date. Featuring over 70 lens-based artists and collectives, it will spotlight a generation who engaged with new ideas of photographic practice, from well-known names to those whose work is increasingly being recognised, including Maud Sulter, Mumtaz Karimjee and Mitra Tabrizian. It will feature images taken across the UK, from John Davies’ post-industrial Welsh landscape to Tish Murtha’s portraits of youth unemployment in Newcastle. Important developments will be explored, from technical advancements in colour photography to the impact of cultural theory by scholars like Stuart Hall and Victor Burgin, and influential publications like Ten.8 and Camerawork in which new debates about photography emerged.

The 80s will introduce Thatcher’s Britain through documentary photography illustrating some of the tumultuous political events of the decade. History will be brought to life with powerful images of the miners’ strikes by John Harris and Brenda Prince; anti-racism demonstrations by Syd Shelton and Paul Trevor; images of Greenham Common by Format Photographers and projects responding to the conflict in Northern Ireland by Willie Doherty and Paul Seawright. Photography recording a changing Britain and its widening disparities will also be presented through Anna Fox’s images of corporate excess, Paul Graham’s observations of social security offices, and Martin Parr’s absurdist depictions of Middle England, displayed alongside Markéta Luskačová and Don McCullin’s portraits of London’s disappearing East End and Chris Killip’s transient ‘sea-coalers’ in Northumberland.

A series of thematic displays will explore how photography became a compelling tool for representation. For Roy Mehta and Vanley Burke, who portray their multicultural communities, photography offers a voice to the people around them, whilst John Reardon, Derek Bishton and Brian Homer’s Handsworth Self Portrait Project 1979, gives a community a joyous space to express themselves. Many Black and South Asian photographers use portraiture to overcome marginalisation against a backdrop of discrimination. The exhibition will spotlight lens-based artists including Roshini Kempadoo, Sutapa Biswas and Al-An deSouza who experiment with images to think about diasporic identities, and the likes of Joy Gregory and Maxine Walker who employ self-portraiture to celebrate ideas of Black beauty and femininity.

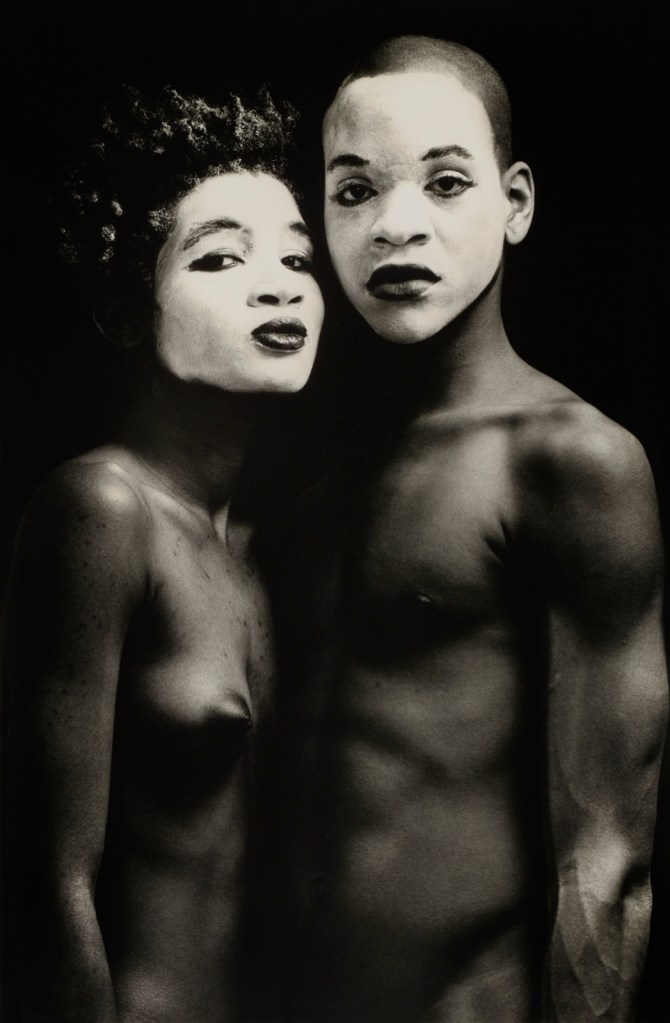

Against the backdrop of Section 28 and the AIDS epidemic, photographers also employ the camera to assert the presence and visibility of the LGBTQ+ community. Tessa Boffin subversively reimagines literary characters as lesbians, whilst Sunil Gupta’s ‘Pretended’ Family Relationships 1988, juxtaposes portraits of queer couples with the legislative wording of Section 28. For some, their work reclaims sex-positivity during a period of fear. The exhibition will spotlight photographers Ajamu X, Lyle Ashton Harris and Rotimi Fani-Kayode who each centre Black queer experiences and contest stereotypes through powerful nude studies and intimate portraits. It will also reveal how photographers from outside the queer community including Grace Lau were invited to portray them. Known for documenting fetishist sub-cultures, Lau’s series Him and Her at Home 1986 and Series Interiors 1986, tenderly records this underground community defiantly continuing to exist.

The exhibition will close with a series of works that celebrate countercultural movements throughout the 80s, such as Ingrid Pollard and Franklyn Rodgers’s energetic documentation of underground performances and club culture. The show will spotlight the emergence of i-D magazine and its impact on a new generation of photographers like Wolfgang Tillmans and Jason Evans, who with stylist Simon Foxton pioneer a cutting-edge style of fashion photography inspired by this alternative and exciting wave of youth culture, reflective of a new vision of Britain at the dawn of the 1990s.

Press release from Tate Britain

Markéta Luskačová (Czech, b. 1944)

Man singing on Brick Lane, London

1982

Gelatin silver print

Tate

© Markéta Luskačová

Markéta Luskačová’s London Street Musicians series includes photographs taken between 1975 and 1990. They document the lives of street musicians performing at London markets. Her photographs reveal the humanity and resilience of these often-solitary musicians. ‘The street musicians themselves were often quite lonely men, yet their music lessened the loneliness of the street, the people in it and my own loneliness’, she recalls. For Luskačová, photography is ‘a tool for trying to understand life … to remember the people and things that I photograph. I want them to be remembered.’

Wall text from the exhibition

Chris Killip (Manx, 1946-2020)

‘Critch’ and Sean

1982

Tate

© Chris Killip

Chris Killip first visited the seacoaling community at Lynemouth Beach in Northumberland in 1976. ‘The beach beneath me was full of activity with horses and carts backed into the sea’, Killip recalls. ‘Men were standing in the sea next to the carts, using small wire nets attached to poles to fish out the coal from the water beneath them. The place confounded time.’ In 1982, Killip started photographing the community, living alongside them from 1983 to 1984. ‘I wasn’t getting close enough, so I bought a caravan and moved into the place and that made a very big difference.’

Killip used a large format plate camera to capture his subjects. ‘It’s not a casual thing’, he notes. ‘I think it works to your advantage. They know this is going to live after this moment. It’s not ephemeral.’

Wall text from the exhibition

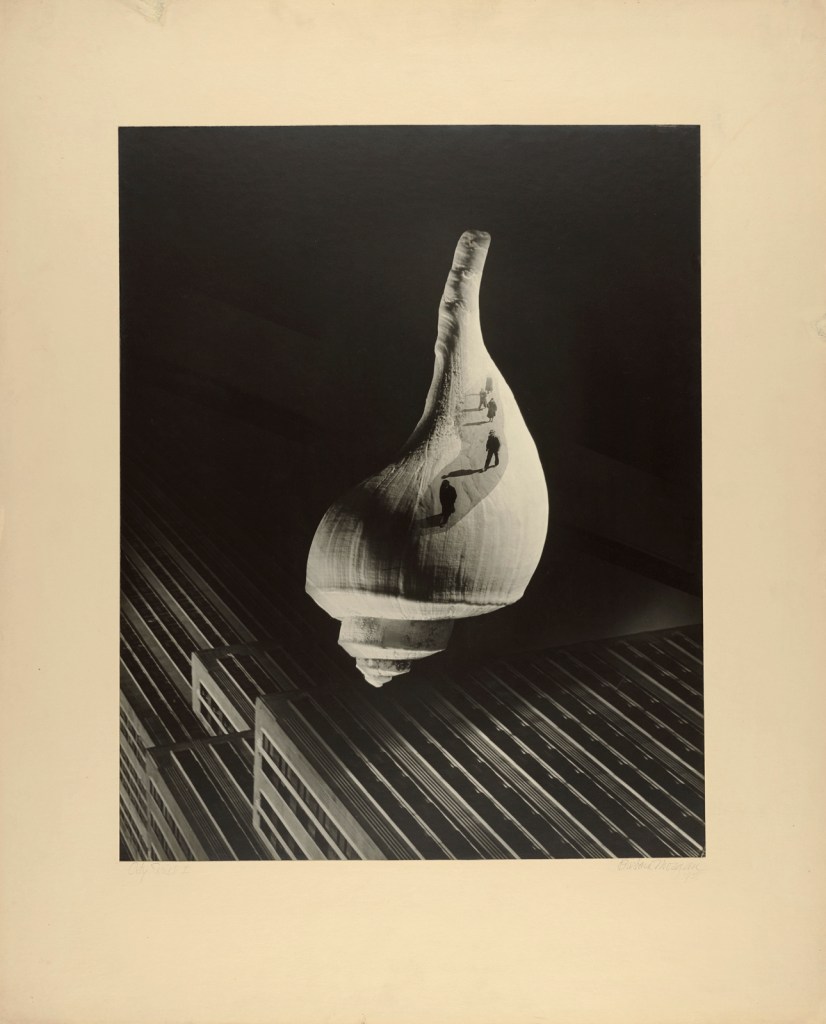

Jo Spence (British, 1934-1992) and Terry Dennett (British, 1938-2018)

Remodelling Photo History: Revisualization

1981-1982

Tate

Presented by Tate Patrons 2014

© The Jo Spence Memorial Archive

These images are from Remodelling Photo History, a collaboration between Jo Spence and Terry Dennett. The work was originally published as a sequence of 13 photographs in which Spence and Dennett both act as photographer and photographic subject. The series was devised as a critique of standard histories of photography and particularly the depiction of women in art. It employs a practice Spence called ‘photo-theatre’. Each photograph emphasises its staging and construction in order to challenge and ‘make strange’ the assumed ‘naturalism’ of photography. Spence commented ‘it is obvious that a vast amount of work still needs to be done on the so-called history of photography, and on the practices, institutions and apparatuses of photography itself, and the function they have had in constructing and encouraging particular ways of viewing and telling about the world.’

Wall text from the exhibition

Joy Gregory (British, b. 1969)

Magenta Dress with Pink Tulips

1984

Courtesy of the artist

© Joy Gregory. All rights reserved, DACS

Joy Gregory’s early interest in colour photography began as student at Manchester Polytechnic. The university was known for its emphasis on the technical and chemical aspects of photography. Gregory’s education taught her the craft of commercial photography but she set out to use these skills like a painter. Her early experiments informed an ongoing interest in stillness, space and light. This series of colour transparencies presents models and still lifes in a painted studio interior. By using multiple exposures and layering images, Gregory suggests a spectral presence in the works. Her focus on the painterly qualities of colour and light here are typical of her practice. She employs languages of beauty and seduction in small textured prints that invite close inspection.

Wall text from the exhibition

John Harris (British, b. 1958)

Mounted Policeman attacking Lesley Boulton at the Battle of Orgreave

1984, printed 2024

John Harris’s photographs from the 1984 Battle of Orgreave challenged government portrayals of miners as aggressors. In 1984, the National Union of Miners identified Orgreave coking plant in South Yorkshire as a key site for picketing. From May to June, strikers attempting to disrupt deliveries were met by growing police presence. Tensions came to a head on 22 June when an estimated 6,000 officers clashed with pickets. One of Harris’s images captures Lesley Boulton cowering beneath the truncheon of a mounted officer. It became an emblem of the strike, appearing on badges, banners and posters.

Wall text from the exhibition

Paul Graham (British, b. 1956)

Union Jack Flag in Tree, Country Tyrone

1985

C-print on paper

Tate

Presented by Tate Members 2007

© Paul Graham

From 1984 to 1986, Paul Graham documented Northern Irish locations featured in news reports of the Troubles. During his first visit, Graham was stopped by a British military patrol suspicious of his camera. As they left, he took a shot with his camera hanging from his neck. The photograph became a ‘gateway’ for Graham’s Troubled Land series. He felt his other images of rioting, murals and destruction, ‘weakly echoed what I saw in the newspapers. This one image did not’. ‘There were people walking to shops and driving cars – simply going about their day, but then there was a soldier in full camouflage, running across the roundabout.’ For Graham, the image ‘reintegrated the conflict into the landscape … it was a conflict photograph masquerading as a landscape photograph.’

Wall text from the exhibition

Pogus Caesar (British born St. Kitts, b. 1953)

Handsworth Riots: Birmingham, United Kingdom

September 1985, printed 2020

Gelatin silver print

Martin Parr Foundation Collection

These photographs capture two days of uprisings in Handsworth, Birmingham, following the arrest of a Black man over a parking violation and a police raid on a pub on the Lozells Road. The photographer, Handsworth resident Pogus Caesar, notes: ‘Where possible it was vital to document.’ He explains: ‘The media has a way of portraying these type of events, I needed to document my truth.’ Caesar’s insider perspective allowed him to capture a range of images, such as artist John Akomfrah reading a sensationalist newspaper account of the two days of violence between the police and local communities.

Wall text from the exhibition

Melanie Friend (British, b. 1957)

Greenham Common, 14 December 1985

1985, reprinted 2023

© Melanie Friend, Format Photographers Archive, Bishopsgate Institute

Exhibition guide

The 80s: Photographing Britain explores a critical decade for photography in the UK. It highlights the work of artists who were radically reconsidering the possibilities of the medium and its role in society.

The exhibition traces developments in photographic art from 1976 to 1993. It follows artists working against a backdrop of high unemployment, industrial action and civil rights activism. Many were part of local photographic communities that developed around key photography schools and collectives. Yet, through innovative publications and independent galleries, they reached national and international audiences.

The artists included in the exhibition expanded photographic practice in Britain. They often collaborated, shared ideas and debated theory. Some were inspired by the activism of the period’s protest movements, using their cameras to provide new ways of looking at society. Others embraced technical developments to push the boundaries of fine art photography. Their work highlights the medium’s range, from landscapes to self-portraiture, and social documentary to conceptual photography.

The 80s: Photographing Britain invites us to reflect on photography’s political and artistic potential. It acknowledges that the diversity of contemporary photographic practice is indebted to the groundbreaking photographers of the 1980s.

Room 1

Documenting the decade

This room documents a period of significant social and political upheaval in the UK. It features protests, uprisings and acts of violence photographed through an activist lens. These photographers challenged dominant narratives and amplified marginalised voices. Some photographed their own communities, giving them access an outsider might not be granted. Others, free from the violence and oppression their subjects faced, turned to photography as an act of solidarity.

The exhibition begins in 1976, the year Jayaben Desai walked out of Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories in London, starting a two-year strike for the right to union representation. The Grunwick dispute typifies the events explored in this room. It was led by an activist whose intersecting identities were the root of her cause. When thousands took to the streets in solidarity it revealed the power of collective action. But it is also an example of failed industrial action, hardline policing and racist media coverage.

In 1979, following months of industrial disputes during the so-called ‘Winter of Discontent’, James Callaghan’s Labour government lost the general election. When Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher took office, she promised to reverse the country’s ‘decline’. The answer, she argued, was free markets, traditional values and British nationalism. Her political philosophy became known as Thatcherism. It helped UK financial markets thrive but led to growing class division and inequalities.

Within this context, socially engaged photographers joined the fight for change. They documented protests and the hardline police tactics designed to silence them. Their images reveal a range of documentary practices and photography’s ability to uncover events that might otherwise remain hidden.

Anti-racist movements

The 1948 British Nationality Act allowed everyone born in Britain or its Empire to become a ‘Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies’. The act encouraged people from Britain’s current and former colonies to move to the UK to address labour shortages, help facilitate post-war reconstruction and build the welfare state. Yet, on arrival, citizens of colour faced hostility and racial discrimination. It marked the beginning of decades of racist rhetoric, rioting and civil rights activism.

In 1968, Conservative MP Enoch Powell delivered his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in Birmingham, criticising immigration and emboldening the far-right. That same year, writer Obi Egbuna founded the British Black Panthers to defend Black communities against racism and discrimination. By the mid-1970s, the far-right, anti-immigration National Front was England’s fourth largest political party. They capitalised on the perception that white workers were losing jobs to immigrants rather than government failures to address unemployment levels. Their far-right ideology was opposed by anti-fascist and anti-racist campaign groups whose members vastly outnumbered the National Front. Throughout the 1980s, high-profile uprisings in Bristol, Leeds, London, Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham revealed the strength of anti-racist feeling across the country.

The Miners’ Strike

Following the First World War, there were 1 million miners in the UK. By the beginning of the 1980s, there were 200,000. In March 1984, the National Coal Board announced plans to close 20 collieries, putting 20,000 jobs at risk. The National Union of Mineworkers, led by Arthur Scargill, responded with a series of year-long strikes. Observed across England, Scotland and Wales, the strikes were a national issue.

Determined to disable labour movements across the UK, Margaret Thatcher took steps to break the miners’ union and limit their power. The government stockpiled coal, mobilised police forces, brought legal challenges, and made media statements heavily criticising the union and striking workers.

Journalists challenged the government’s portrayal of miners as aggressors and agitators. Photographers helped evidence instances of excessive and often unprovoked violence by law enforcement. But the government’s plans to take down miners, one of the strongest unionised workforces in the country, had worked. On 3 March 1985, after 362 days, the National Union of Mineworkers accepted defeat. Union members voted to end the strike. The strike put industrial issues and workers’ rights on the national agenda and had a profound impact on the politics of the period.

Brenda Prince was a member of Format Photographers Agency. Started by Maggie Murray and Val Wilmer in 1983, Format was set up as an agency for women. Prince joined in 1984. ‘We were all documentary photographers’, Prince notes. ‘We would work on our own stories and my miners’ strike images came out of that.’ ‘The miners’ strike gave me the opportunity to document working class people who were really struggling to keep their jobs and keep their communities alive’, Prince explains. She spent eighteen months in Nottinghamshire’s mining communities. Her works highlight the vital role women played in sustaining the strike.

(For more information on the miners’ strike please see the posting on the exhibition ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners Strike 1984-85 at Four Corners, London, Sept – October, 2024)

Greenham Common

On 5 September 1981, a group of women marched from Cardiff to the Royal Air Force base at Greenham Common in Berkshire. The site was common land, loaned to the US Air Force by the British Government during the Second World War and never returned. The group called themselves Women for Life on Earth. They were challenging the decision to house 96 nuclear missiles at the site. On arrival, they delivered a letter to the base commander stating: ‘We fear for the future of all our children and for the future of the living world which is the basis of all life.’ When their request for a debate was ignored, they set up camp. Others joined and the site became a women-only space.

Over the next 19 years, Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp became a site of protest and home to thousands of women. Some stayed for months, others for years, and many visited multiple times. Greenham women saw their anti-nuclear position as a feminist one. They used their identities as mothers and carers to fight for the protection of future generations and inspired protest movements across the world.

In 1987, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and US President Ronald Reagan signed a treaty which paved the way for the removal of cruise missiles from Greenham. Gorbachev has since paid tribute to the role ‘Greenham women and peace movements’ played in this historic agreement. By 1992, all missiles sited at Greenham had been removed and the US Air Force had left the base. The Peace Camp remained until 2000 as a protest against nuclear weapons.

Format Photographers Agency (1983-2003), featuring Maggie Murray, Melanie Friend, Brenda Prince and Jenny Matthews, played a crucial role in documenting social movements. Their photographs of the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp capture this landmark protest against nuclear missiles. They record the activism, daily life and personal stories of the women involved, highlighting their strength and creativity. They also reveal contrast between the women’s camp and their non-violent resistance and the militarised environment they were protesting.

The Gay Rights Movement

In 1967, the Sexual Offences Act partially decriminalised sexual acts between two men. It was the result of decades of campaigning but the act did nothing to address the discrimination LGBTQ+ communities faced. In 1970, the first meeting of the Gay Liberation Front took place. They wrote a manifesto outlining how gay people were oppressed and mapped out a route to liberation through activism and consciousness-raising. In the 1980s, the Gay Rights movement continued to grow. Queer communities came together in opposition to homophobia fuelled by Conservative ‘family values’ campaigns and fear of the HIV/ AIDS epidemic.

The first cases of Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID) in the UK were identified in 1981. In 1982, GRID was renamed Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and Britain saw its first deaths from the disease. By 1987, AIDS was a worldwide epidemic, with around 1,000 recorded cases in the UK. The public focus was largely on gay men, who were being infected in much greater numbers, fuelling anti-gay rhetoric in politics and the press.

In 1988, the government passed Section (formerly Clause) 28 of the Local Government Act. The legislation stated local authorities ‘shall not intentionally promote homosexuality’ or ‘promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship’. Section 28 forced many LGBT groups to disband and saw literature depicting gay life removed from schools and libraries. But it also galvanised the Gay Rights movement. People took to the streets in a series of marches and protests, and set up organisations to lobby for change.

Poll Tax

The community charge, commonly known as the ‘poll tax’, was introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in 1989 in Scotland, and 1990 in England and Wales. This flat-rate tax on every adult replaced previous taxation based on property value. The tax was accused of benefitting the rich and unfairly targeting the poor.

The national anti-poll tax movement began on the streets of Glasgow and led to a series of anti-poll tax actions across the UK. Many demonstrations saw clashes between police and protestors, and resulted in rioting. The fallout from the tax triggered leadership challenges against the prime minister and, in 1990, Thatcher resigned. In 1991, following vehement national opposition, John Major’s Conservative government announced the poll tax would be replaced by council tax.

The Troubles

The Troubles was a 30-year conflict in Northern Ireland between Protestant Ulster loyalists, who believe Northern Ireland should remain part of the United Kingdom, and Catholic Irish republicans, who believe in an independent united Ireland. The roots of the conflict date back to the twelfth century, when English settlers displaced Irish landholders and colonised areas of Ireland. In the seventeenth century, in an attempt strengthen British rule over the Catholic population, Britain moved protestants from Scotland and England to the north of Ireland. This caused sectarian divisions that continue to this day.

During the 1920 Irish War of Independence against British rule, a treaty was signed dividing the island into two self-governing areas. The majority Catholic counties, primarily in the south, formed the Irish Free State. The six majority Protestant counties in the north became a region of the United Kingdom. Catholics living in Northern Ireland faced discrimination and police harassment and, in the late 1960s, they organised civil rights marches challenging their treatment. Activists were met by counter-demonstrators and violent suppression by the almost exclusively Protestant police force. Riots ensued and the Troubles began. In 1969, the British Army was deployed to restore order in the region, but instead violence escalated. Paramilitary organisations on both sides took up arms and employed guerrilla tactics. More than 3,500 people had been killed by the time the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, ending 30 years of violence.

Room 2

The cost of living

These photographs spotlight UK class dynamics in the 1980s. Images of social security waiting rooms and people living on the streets, sit alongside office workers, Conservative Party functions and gallery private views.

Margaret Thatcher believed, ‘whatever your background, you have a chance to climb to the top’. She presented social mobility as the reward for those who worked hard enough. The government encouraged people to become part of the property-owning middle classes. The 1980 Housing Act gave 5 million council house tenants the right to buy at discounted prices. But Thatcherism also advocated for limited government controls, privatisation of industry, low taxes and free markets. Conservative economic philosophy made the wealthiest in society richer. While young urban professional ‘yuppies’ in financial centres thrived, the gap between classes increased.

In the 1970s, a global economic recession and increased mechanisation had led to deindustrialisation. By the 1980s, working-class communities centred around heavy industries were greatly affected. Specialised machines replaced workers and manufacturing moved to countries where wages were lower. The government introduced legislation to limit the influence of trade unions and allow employers to sack striking workers. Thousands were left unemployed. The foundations of working-class identity were being eroded while the prospect of middle-class affluence remained out of reach for many.

The photographers in this room produced work that highlights these class dynamics. Some revealed the human stories behind the policies and statistics, others helped cement stereotypes.

Room 3

Landscape

The photographs in this room highlight different political and social narratives embedded in the landscape of the British Isles. They reveal the impact of human endeavour on the land and the effect of the land and its borders on people.

While these photographs depict a particular part of the world, they also explore how landscapes are constructed in our imaginations. As artist Jem Southam notes, ‘When we look at a photograph of a landscape, we’re looking as much at a projection of the cultural, social, historical, literary connections we have with that place, as we are with an actual physical landscape.’ Southam describes his work as ‘a description of a culture, and of a place, but also an investigation of how we carry imagery in our minds’.

Some of the featured photographers drew on the history of British landscape painting to produce nostalgic images of sublime natural vistas. Others parodied or subverted the romantic notion of a green and pleasant land, revealing British landscapes as sites of decay, conflict, deindustrialisation and racism. Several artists produced photographs that immerse us in their chosen scenes, treating industrial ruins with the same careful attention as natural phenomena. Those working with large format cameras and slow exposure times gave their chosen scenes a painterly quality. Others utilised photography’s ability to record the everyday. They embraced a medium some didn’t consider high art to capture landscapes many didn’t consider worthy of documenting.

Room 4

Image and text

Conceptual art prioritises the idea (or concept) behind an artwork. The photographs in this room focus on photography’s ability to carry ideas. They challenge the notion of the photograph as a window on the world and use text to complicate the medium’s relationship with reality.

Artist and academic, Victor Burgin wrote that our most common encounters with photographs – in advertisements, newspapers and magazines – are all mediated by text. Informed by semiotics, the study of signs and symbols, Burgin highlighted our reliance on existing systems of codes and social meanings to ‘read’ photographs. By making work that combines image and text he was ‘turning away from concerns inherited from “art” and towards everyday life and its languages, which are invariably composed of image/text relations’. Burgin used image and text to ‘dismantle existing communication codes’ and ‘generate new pictures of the world.’

Burgin’s art and ideas influenced the photographers in this room, several of whom he taught. They used text borrowed from literature, film, parliamentary speeches and journalism to expose hidden meanings, heighten emotion and confuse. The resulting artworks expanded contemporary photographic practice while offering new ways of viewing the world.

Room 5

Remodelling history

The personal and intimate photographs of Jo Spence and Maud Sulter remodel the history of representation. Their artworks and writings challenge photography’s sexist and colonial past, and its relationship to class politics. Rather than using the camera to stereotype, categorise, objectify or commodify, they used it to reclaim agency.

For both artists, their collaborative approach to image-making was key to the politics of their practice. Sulter and Spence worked closely with other artists and their subjects. Through collaboration, they discovered new ways of seeing and being seen.

For Spence, this meant ‘putting myself in the picture’. She recognised the power of having control over her representation and, together with artist Rosy Martin, developed photo-therapy. Spence noted: ‘I began to use the camera to explore links that I had never approached before, links between myself, my identity, the body, history and memory’. Known for her unflinching gaze and use of satire, Spence challenged social expectations. She questioned common visual representations of beauty, health and womanhood, as well as women’s place in society.

Sulter’s photography explores absence and presence. She was interested in the ways that ‘Black women’s experience and Black women’s contribution to culture is so often erased and marginalised’. Whether rephotographing personal family photographs or producing portraits, Sulter ‘put Black women back in the centre of the frame – both literally within the photographic image, but also within the cultural institutions where our work operates’. Sulter saw her practice as a contribution to ‘archival permanence’. As she noted: ‘Survival is visibility.’

Room 6

Reflections on the Black experience

This room examines the influence of Reflections of the Black Experience, which opened at Brixton Art Gallery in south London in 1986. The exhibition was organised by the Greater London Council’s Race Equality Unit. It invited artists ‘from a diversity of cultural/political backgrounds’ to collectively ‘challenge the existing and inadequate visual histories of the black experience’. In the 1980s, the term ‘political blackness’ was used as an organising tool to encourage people of colour to come together in the fight against racism. Reviews noted the range of practices on display and that the exhibition set ‘a new agenda where black people can begin to trace a history of representation of ourselves by ourselves’. Yet they also warned: ‘If seen as definitive representations / reflections in photographic imagery the exhibition becomes very limited.’

D-MAX: A Photographic Exhibition was a response to this possible containment of Black photographic practice. Three of the photographers featured had exhibited work in Reflections of the Black Experience. The exhibition opened at Watershed in Bristol in 1987 and toured to the Photographers’ Gallery in London and Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff. It attempted to free Black photographers from the burden of representation and the restrictions of documentary practice.

Both exhibitions played an important role in the development of the Association of Black Photographers, now Autograph ABP. Established in 1988, its mission was to advocate for the inclusion of historically marginalised photographic practices. Working from a small office in Brixton, the agency delivered an ambitious programme of exhibitions, publications and events. Autograph ABP developed alternative models of producing and sharing photography without defining Black photographic practice or the Black experience.

Although the focus of Reflections of the Black Experience was on young photographers, the exhibition also included a tribute to Armet Francis, who was already well-established. Francis’s photographs focus on the areas of Notting Hill and Brent in west London, documenting the lives of people in the African and Caribbean diasporas. His images capture elements of everyday life, like school and church, as well as shining a light on Black community activism. Francis provided a crucial early articulation of Black identity and political presence in British photography.

Room 7

Self-portraiture

Whether putting themselves in the frame or handing the shutter release to their subjects, the photographers in this room understood the importance of people of colour having control over their image.

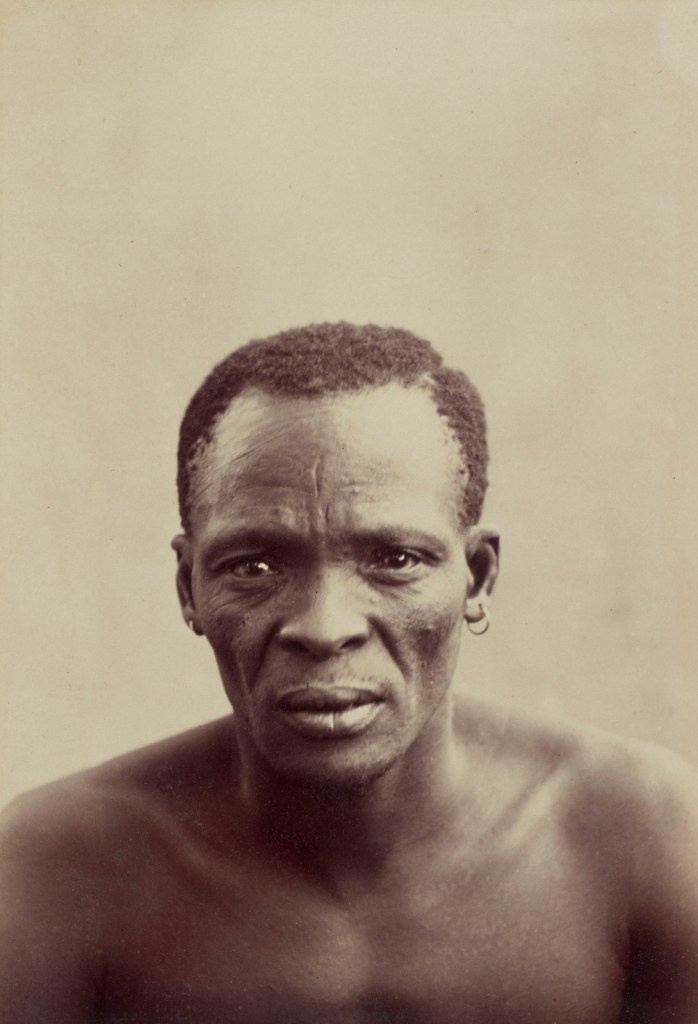

In the nineteenth century, photography was a valuable tool for colonial powers. Ethnographic images of Indigenous Peoples and landscapes were distributed through postcards and magazines. They ‘othered’ subjects and created racist stereotypes that legitimised the mission of empire. The photographs on display here challenge this colonial gaze. They present nuanced, multi-dimensional representations of Black and Asian British selfhood.

These artists used different photographic and post-production techniques to complicate the idea of representation and identity. The diversity of their images enhances our understanding of what it means to capture the ‘self’. By adding text, highlighting objects and layering images through projection and photomontage, they remind us that identity isn’t a fixed entity.

Three of the photographers shown here took part in Autoportraits, Autograph ABP’s first exhibition, held at Camerawork in east London in 1990. The exhibition took self-portraiture as its theme. Cultural theorist, Stuart Hall, wrote an essay for the catalogue. In ‘Black Narcissus’, he defended the use of ‘self-images’ by contemporary Black photographers. Far from ‘a narcissistic retreat to the safe zone of an already constituted “self”‘, Hall notes that self-portraiture presents a ‘strategy … of putting the self-image, as it were, for the first time, “in the frame”, on the line, up for grabs. This is a significant move in the politics and strategies of black representation.’

Room 8

Community

The photographs in this room are contributions to a people’s history. They focus on communities whose stories were often absent from the visual arts of the period. To tell these stories with integrity, photographers attempted to document communities from within. Some formed collectives, brought together by shared interests and common goals. They encouraged photographers to move to live alongside their subjects and to build relationships with local people to better represent them. Others documented their own lives and those of their local communities. Their images challenged prevailing narratives and aimed to bring about social change.

Here, photographs of everyday life are presented through a different lens. By the 1970s, most people expected to be photographed in colour, using roll film in point-and-shoot cameras. By producing black-and-white prints, these photographers appear to reference fine art and documentary practice. They invite us to view their subjects as part of the history of photography.

These photographers recorded different social pressures: inadequate housing, disproportionate unemployment, aggressive policing and stereotypical framing in the media. They also highlighted the joy, pride and humour within these communities. By working with their subjects and photographing their own experiences, they produced works that provide insight, build connections and encourage empathy.

Room 9

Colour

These photographers challenged the expectation that ‘art’ photography had to be black and white. At a time when the market for colour photography was still young, they subverted and appropriated colour’s associations with the commercial worlds of fashion and snapshot photography. They used burgeoning colour technologies to create a new visual language that became emblematic of the period. Their images offered new ways of seeing British life and culture.

Britain’s first exhibition of photography taken on colour film was Peter Mitchell’s 1979 show at Impressions Gallery in York. By this time, colour had almost entirely replaced black-and-white film in amateur photography. But many professional photographers were looking for greater nuance than the saturated results of commercially available film stock.

Across the decade, small technical leaps allowed for greater creativity in colour image-making. Kodachrome, the first commercially available colour negative film, was the most commonly used of the period. It provided rich and naturalistic colours, remarkable contrast and extraordinary sharpness. New papers such as Cibachrome II allowed artists to produce high-quality colour prints with greater permanence. Around 1984, Fuji introduced a new colour negative film offering even punchier, brighter saturation. Used with new cameras such as the Plaubel Makina 67 and daytime flash, photographers could produce detailed images in vivid colour.

Photographers exploited these technical advances. They used the camera like a painter, highlighted the garish excesses of consumer society and invented new forms of documentary. By December 1985, Creative Camera journal had announced ‘from today, black and white is dead’.

Room 10

Black Bodyscapes

The photographs of Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Ajamu X and Lyle Ashton Harris explore masculinity, sexuality and Blackness. Their staged portraits highlight the artists’ technical skills while challenging essentialist ideas of identity.

Fani-Kayode was described by Ajamu X as ‘the most visible, out, Black, queer photographer’ of the 1980s. His photographs interrogate a perceived tension between his heritage, spirituality and gay identity. Fani-Kayode commented: ‘On three counts I am an outsider: in terms of sexuality; in terms of geographical and cultural dislocation; and in the sense of not having become the sort of respectably married professional my parents might have hoped for.’ For Fani-Kayode the position of ‘outsider’ produced ‘a sense of freedom’ that he felt opened up ‘areas of creative enquiry which might otherwise have remained forbidden’.

Ajamu X’s desire to document ‘the whole of Black queer Britain’ has been dubbed ‘Pleasure Activism’. ‘There is a reluctance to talk about sex and pleasure’, he notes. ‘To me, the act of pleasure has to … be part of the conversation around making work.’ For Ajamu X, the materiality of his photography is as important as his subject. ‘I still get excited by the magic alchemy of being in the darkroom’, he reflects. ‘Process is key to my practice – in some cases, much more than the photographic image itself.’

Harris, a US photographer, was included in Autograph ABP’s first exhibition, 1990’s Autoportraits. He describes his photographs as a celebration of ‘Black beauty and sensuality’. Harris notes: ‘I think it’s important to understand that my work is not so much about trying to unpack identity as it is about relationally exploring my positionality to what has gone before and to what is unfolding in our present day lives, as a way to imagine a future to come.’

Room 11

Celebrating subculture

By the end of the decade, previous distinctions between commercial and art photography had begun to break down. Launched in 1980, popular magazines like The Face and i-D brought together fashion, art and advertising. They employed cutting-edge photographers to capture the youth movements that set trends and defined contemporary culture.

Many of the photographs in this final room of the exhibition document subcultures. They feature young people resisting dominant values and beliefs, and challenging the policies and rhetoric that informed them. Section 28 of the Local Government Act was one such policy. Passed in 1988, it prohibited local authorities from ‘promoting homosexuality’. Schools and libraries banned literature, plays and films referencing same-sex relationships and arts organisations faced censorship. Yet, in the face of discrimination, gay and lesbian communities mobilised. The government had put queer culture in the spotlight and, with great courage, many gay and lesbian photographers produced work that changed public discourse.

These artists embraced a range of photographic practices. They combined street photography with saturated colour to challenge stereotypes. They produced highly staged portraits exploring social justice issues, and they captured underground club scenes using the principles of community photography.

The photographs in this room offered a new vision of the UK. One that is both politically engaged and celebratory. They highlight the importance of self-expression, give agency to the photographic subject and make overlooked perspectives visible. Across style, format and subject, these artists asserted photography’s role in society: to document, interrogate and celebrate.

Text from the Tate Britain exhibition guide

Martin Parr (British, 1952-2025)

New Brighton, England, 1983-85

From the series The Last Resort

1983-1985

C-type print

© Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Martin Parr took his first colour photographs as a student at Manchester Polytechnic in 1971 and has worked exclusively in colour since 1982. These photographs are from his series The Last Resort. They document the Merseyside seaside resort of New Brighton at a time of economic decline. The series features Parr’s characteristic use of daytime flash and saturated colour to produce satirical images exploring leisure and consumption. Parr was ‘interested in showing how British society is decaying; how this once great society is falling apart.’ Of the series’ reception, Parr notes, ‘People thought it was exploitation, you know – middle-class guy photographing a working-class community, that sort of stuff. The thing is, it was shown first in Liverpool and no one batted an eyelid … middle-class people [in London] don’t know what the north of England’s like.’

Wall text from the exhibition

Paul Reas (British, b. 1955)

Hand of Pork, Caerphilly, South Wales

1985-1988

C-print on paper

© Paul Reas/Martin Parr Foundation

“Deregulation of the banking system meant credit was easy to come by and consumer spending rose fast. Shopping malls were the new cathedrals of consumption and retail parks with supermarkets and furniture stores the parish churches. Shopping became leisure”

~ Paul Reas

Inspired by the use of colour in advertising, Paul Reas dedicated his first series of colour photographs to the post- industrial consumer boom in the UK in the 1980s. These works, taken with a medium-format camera and a large flashgun, present everyday scenes at US-style retail parks, supermarkets and the new housing estates fast becoming a feature of British towns and villages. Reas’s images consider the impact of these ‘new cathedrals of consumption’. Reas has described how Margaret Thatcher’s belief in a free-market economy and individualism moved British society from a ‘we’ to a ‘me’ mentality. As he explains: ‘Although I was photographing people, I never really think about my photographs as being totally about people. They’re about the systems that we’re all subjected to.’

Wall text from the exhibition

Paul Reas (British, b. 1955)

Army Wallpaper, B&Q Store, Newport South Wales

c. 1987

C-print on paper

© Paul Reas/Martin Parr Foundation

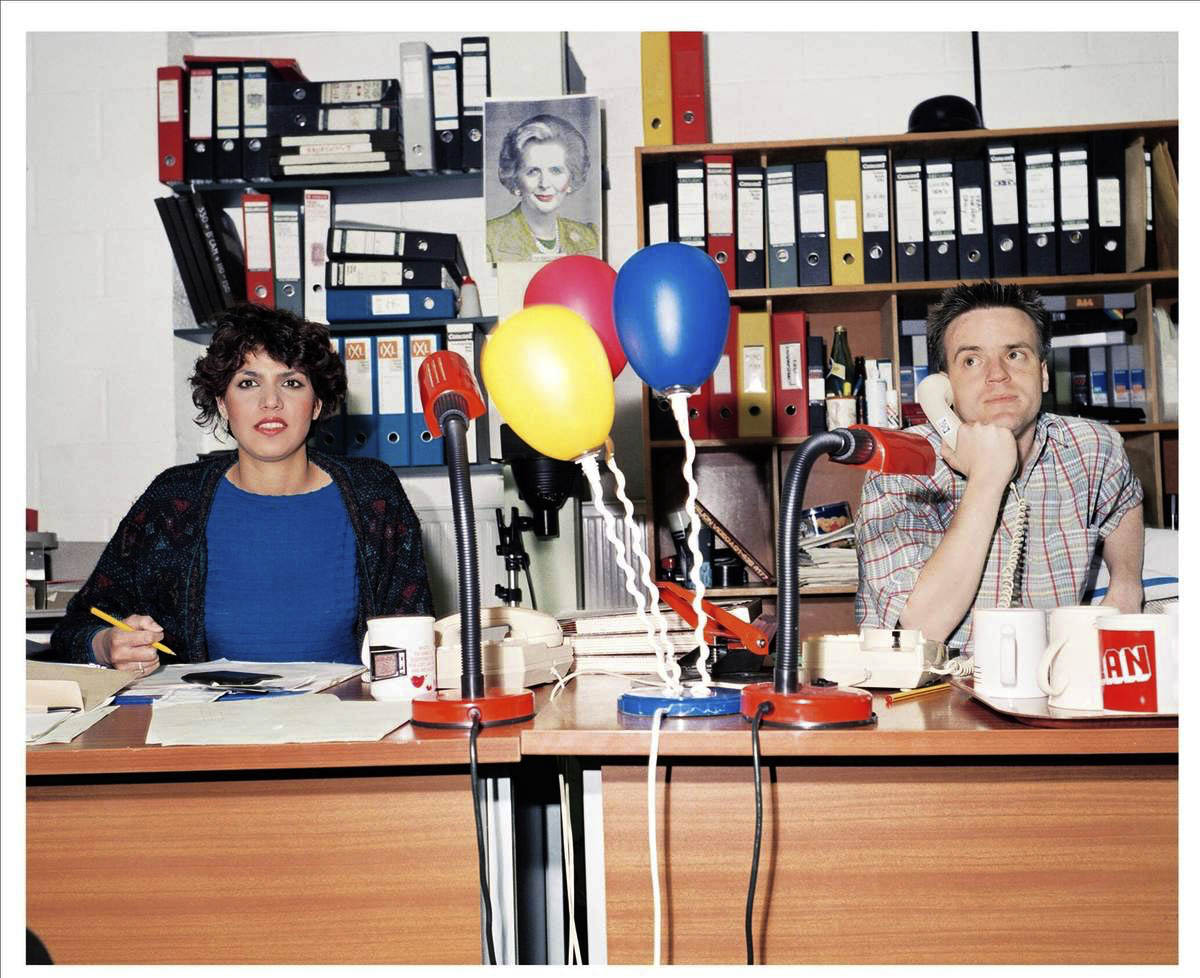

Anna Fox (British, b. 1961)

Independent Video Production Company

1988

From the series Work Stations

The Hyman Collection

Courtesy of the Centre for British Photography

© Anna Fox

“Thatcher was a powermonger and her favourite phrase, ‘there is no such thing as society, just individuals’ saw the end of a culture of community support and a rise in the pursuit of wealth for individuals – primarily white men. Compared to now, things in some ways were more straightforward, and as artists we knew what we were making work about – there was a positive sense that we could change things; we criticised society with hope fueling us…

I made two key bodies of work in this period, including Work Stations – a study of London office life with found texts, creating satirical commentary on a very conservative Britain. I was interested in how consumerism was sweeping the floor with us and how money ruled. There were hardly any documentary images made of office life, it wasn’t considered a valid subject and this interested me. All documentary images change as time passes – design and style become more fascinating as they age – and I am so pleased these images have stayed in people’s imagination. They are a significant record of a particular time and they bring up a lot of memories of what it was like to live and work in it.”

Zoe Whitfield. “The story of 80s Britain, as seen by 7 notable photographers,” on the Dazed website, November 22, 2024 [Online] Cited 03/04/2025

Anna Fox (British, b. 1961)

Salesperson, Cafe, the City

1988

From the series Work Stations

Inkjet print on paper

The Hyman Collection

Courtesy of the Centre for British Photography

© Anna Fox

In her Work Stations series, Anna Fox captures London office life in the late 1980s. ‘I was attracted to it because it’s such an ordinary subject and hardly anyone had ever photographed office life’, she says. The photographs combine colour, on-camera flash and snapshot style compositions to create hard shadows and emphasise the immediacy of each scene. The unusual framing and off-kilter camera angles give them a spontaneous and humorous feel. Fox repurposed text from business articles and magazines to loosely pair with each image in the series. They reveal the intense competition, stress and absurdities of corporate culture in Thatcher-era Britain.

Wall text from the exhibition

Anna Fox (British, b. 1961)

Friendly Fire, target (Margaret Thatcher) / Margaret Thatcher Target

1989

Inkjet print on paper

The Hyman Collection

Courtesy of the Centre for British Photography

© Anna Fox

While working on her 1987-1988 series Work Stations exploring office life, Anna Fox came across the phenomenon of paintballing. Learning that corporate sales teams often took part in outdoor paintball games to encourage team spirit and competitiveness, she wanted to capture these ‘weekend wargames’ in action. In her series Friendly Fire, Fox plays the role of war photographer just as the participants play at being soldiers. This image depicts a paint-splattered cardboard cutout of Margaret Thatcher used for target practice. Taken in the aftermath of the Falklands War, Fox’s work explores the connections and contrasts between these sites of simulated conflict and the experiences of military personnel.

Wall text from the exhibition

Grace Lau (British-Chinese, b. 1939)

Interiors series

1986

Colour transparency

Lent by the artist

© Grace Lau 1986

Grace Lau employs colour to explore fetish subcultures from a feminist perspective. This series was produced following an invitation to document a London cross-dressing community. Lau’s portraits are often set in private, domestic spaces where fantasies and alternative lifestyles could be acted out more openly. As the artist explains: ‘When I started making portraits of cross-dressers, many projected their alter-identities with such joyous style that I felt black-and-white could not do justice to their vibrant characters. Colour seemed to express their proud desire to project subliminal identities and these images with their saturated, bright colours, reflect my subjects’ multi-layered personalities; their bright red lipstick, glamorous dresses and jewellery blazing into life in colour transparency film.’

Wall text from the exhibition

Brenda Prince (British, b. 1950)

Anti-Clause 28 demo in Whitehall, London

9 June 1988

Format Photographers Archive, Bishopsgate Institute

© Brenda Price

Did the 80s really last from 1976-94? This exhibition thinks it did – resulting in a show replete with gems, but in need of a tight edit…

The exhibition starts out along thematic lines. The opening room is dedicated to protest, from the Grunwick strike led by British/South Asian workers in Brent, through clashes between pickets and the police at the Orgreave coking plant, and marches opposing the homophobic Section 28 legislation. In a gallery dedicated to money and the growing divide between haves and have-nots, Paul Graham’s grimly atmospheric pictures of DHSS waiting rooms face off against Martin Parr’s snarky snaps of garden parties and gallery openings. In the next section, the lens is turned on the landscape, and the transformations wrought both by industry and its removal. …

The closing section Celebrating Subcultures bypasses those usually associated with the 1980s (punks, goths, rude boys, new age travellers) but includes an entire wall of 1990s photographs by Wolfgang Tillmans, most of which were shot in Germany and Greece…

The art world of the 1980s speaks strongly to our own, in particular, the shared interest in identity and representation. In short supply here is the punky irreverence of an era in which taking the piss was practically a national hobby.

Hettie Judah. “The 80s: Photographing Britain review – a meandering look at pomp, protest – and pork,” on The Guardian website Wed 20 Nov 2024 [Online] Cited 02/05/2025

For all that, I left this show feeling slightly beleaguered by the overload of images and attendant theory. The foregrounding of emerging visual strategies, from activist reportage to nascent conceptualism to identity-driven self-portraiture, is brave but often bewildering rather than enlightening. The final room, Celebrating Subculture, is a case in point, being a cursory nod to a decade that saw the emergence of the style-conscious youth culture that echoes through fashion, music and indeed everyday life until this day.

If your image of the 80s is predicated on memories of The Face magazine, or the blossoming of extravagant tribal subcultures such as goths and New Romantics in clubs such as the Batcave and Blitz, you may be as baffled as I was not to encounter a single image by the likes of Juergen Teller, Nigel Shafran or Derek Ridgers. Instead, there are four street portraits of stylish young men by Jason Evans and a recreation of Wolfgang Tillmans’s first photo installation, which mainly comprises images first published in i-D magazine. A portrait of the 80s, then, but one that at times seems determinedly out of focus.

Sean O’Hagan. “The 80s: Photographing Britain review – in your face and to the barricades,” on The Guardian website, Sun 24 Nov 2024 [Online] Cited 02/05/2025

Roy Mehta (British, b. 1968)

From the series Revival, London

1989-1993

C-print on paper

Courtesy of the artist and LA

Roy Mehta’s Revival, London, series focusses on Caribbean and Irish communities in Brent northwest London, where he lived in the 1980s. Much of Mehta’s practice engages with the complexity of identity and belonging.

Mehta invites us ‘to share in the atmosphere of the subject’s internal world by illustrating the gentle essence of our shared humanity through images of empathy, faith and tenderness’. He notes: ‘I wanted the work to depict compassion and solidarity, along with reflections of the everyday. I felt these were absent from some mainstream representations of diasporic identities at that time in the 1980s.’

Wall text from the exhibition

David Hoffman (British)

Nidge & Laurence Kissing, taken at a poll tax protest in London

1990

© David Hoffman

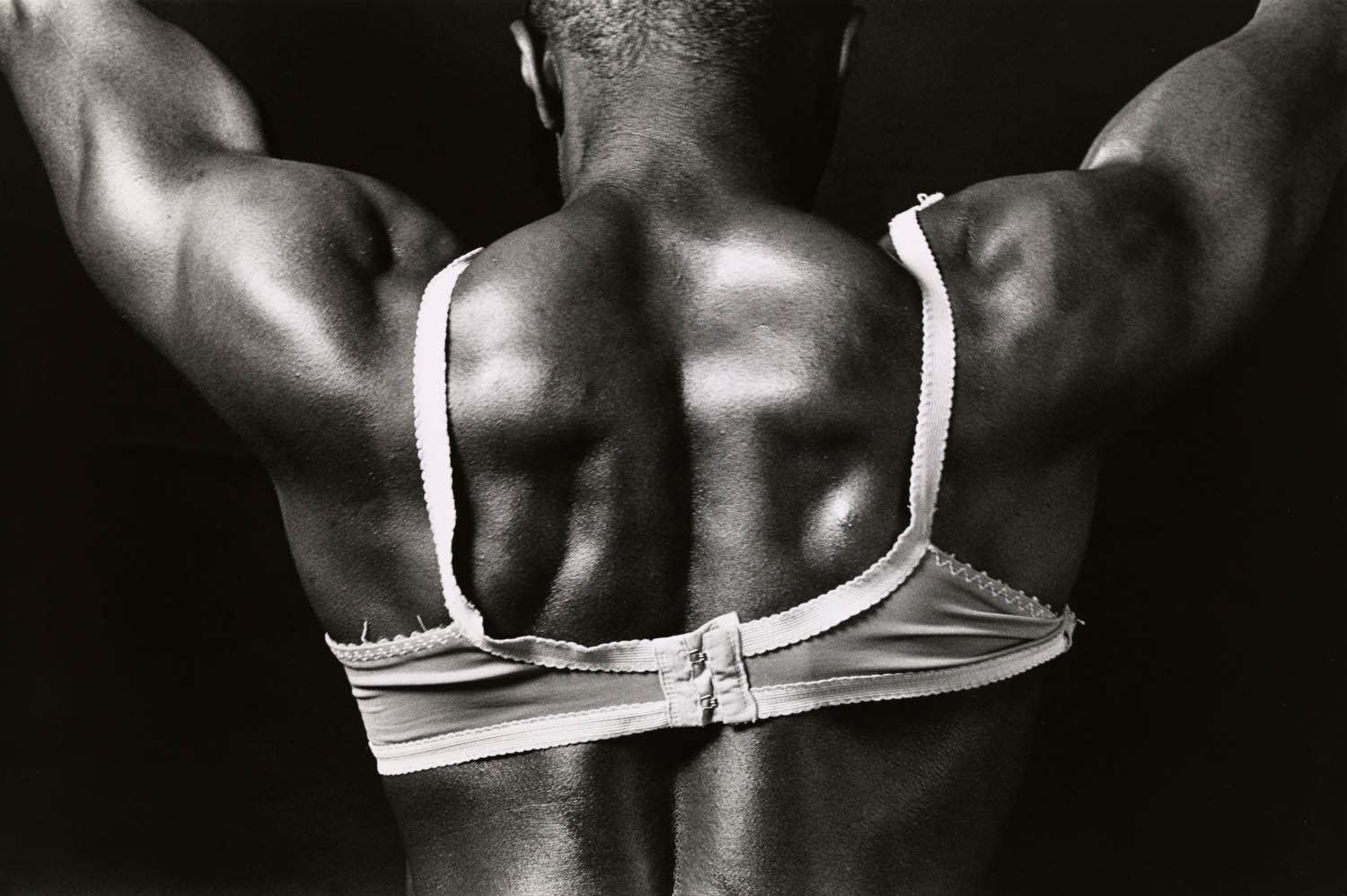

Ajamu X (British, b. 1963)

Body Builder in Bra

1990

Gelatin silver print on paper

Tate

Presented by Tate Members 2020

When asked about the photoshoot for this image, Ajamu said: ‘we went to the local market here in Brixton, bought a bra and played around with it. This was one of the first shots.’ This spontaneity is contrasted with the carefully framed close-up of the sitter’s back. Bodybuilding has long been an area of interest for Ajamu. Although it represents ‘an archetypal image of the male body’, he describes how his practice is ‘a consistent attempt to subvert, re-think, play with these limited modes of representations around particular bodies in a multi-dimensional way.’

Wall text from the exhibition

Jason Evans (Welsh, b. 1968) and Simon Foxton (British, b. 1961)

Untitled

1991

From the series Strictly

Tate

© Jason Evans

“This work was made in collaboration with Simon Foxton. It takes the head-to-toe ‘straight up’ documentary approach to street style as a point of departure, however they’re entirely constructed. We saw fashion photography as a political space where we could create something that pushed back at the media stereotypes of young Black men. This is a Trojan horse exercise, intended to disrupt the white supremacist media project. For many, it may be hard to imagine how racist the UK felt then, which, especially with hindsight, makes today’s politics all the harder to witness.”

Zoe Whitfield. “The story of 80s Britain, as seen by 7 notable photographers,” on the Dazed website, November 22, 2024 [Online] Cited 03/04/2025

Al-An deSouza (Kenyan, b. 1958)

Junglee, Indian Aphorisms series

1992/2024

Courtesy Al-An deSouza and Talwar Gallery, New York and New Delhi

In Indian Aphorisms, Al-An deSouza combines self-portraits with introspective reflections. Through the series, the artist attempts to reclaim and redefine their identity. Each work portrays the tension between public perception and private reality, illustrating the ways in which personal identity is continually negotiated and reshaped. DeSouza’s photographs reveal their struggle to separate reality from yearning and imagining. ‘I don’t know which of my memories are my own remembrance, which are tales whispered to me secretly as I lay in my bed, or which are ghostly after images, effigies petrified between the tissue leaves of photo albums’, the artist explains.

Wall text from the exhibition

Related publications

The 80s: Photographing Britain

Edited by Yasufumi Nakamori, Helen Little and Jasmine Chohan

Featuring contributions by Bilal Akkouche, Geoffrey Batchen, Derek Bishton, Jasmine Chohan, Taous Dahmani, Helen Little, Yasufumi Nakamori, Mark Sealy, Noni Stacey

Published November 2024, hardback £40

Available on the Amazon website

Tate Britain

Millbank, London

SW1P 4RG

Open daily 10.00 – 18.00

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Austria, 1899-1968) '[Calypso]' about 1944; before 1946 from the exhibition Exhibition: 'Unseen: 35 Years of Collecting Photographs' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Dec 2019 - March 2020 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Austria, 1899-1968) '[Calypso]' about 1944; before 1946 from the exhibition Exhibition: 'Unseen: 35 Years of Collecting Photographs' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Dec 2019 - March 2020](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_04305501_2000x2000.jpg)

![Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Guadalupe Mill]' 1860 from the exhibition Exhibition: 'Unseen: 35 Years of Collecting Photographs' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Dec 2019 - March 2020 Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Guadalupe Mill]' 1860 from the exhibition Exhibition: 'Unseen: 35 Years of Collecting Photographs' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Dec 2019 - March 2020](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_06196501_2000x2000.jpg)

![Marinus Jacob Kjeldgaard (Danish, 1884-1964, active Paris, France late 1930s - late 1940s) '[Collage: Balance of Powers]' about 1939 Marinus Jacob Kjeldgaard (Danish, 1884-1964, active Paris, France late 1930s - late 1940s) '[Collage: Balance of Powers]' about 1939](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_05085801_2000x2000.jpg)

![Paul Outerbridge (American, 1896-1958) '[Egg in Spotlight]' 1943 Paul Outerbridge (American, 1896-1958) '[Egg in Spotlight]' 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_32105401_2000x2000.jpg)

![Shigeichi Nagano (Japanese, 1925-2019, active Tokyo, Japan) '[Tokyo, Aobadai (Nishi Saigoyama Park), Meguro Ward]' 1988 Shigeichi Nagano (Japanese, 1925-2019, active Tokyo, Japan) '[Tokyo, Aobadai (Nishi Saigoyama Park), Meguro Ward]' 1988](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_30687901_2000x2000.jpg)

![Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879) '[Spring]' 1873 Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879) '[Spring]' 1873](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_06520801_2000x2000.jpg?w=738)

![Reverend William Ellis (British, 1794-1872) and Samuel Smith. '[Portrait of a Black Couple]' about 1873 Reverend William Ellis (British, 1794-1872) and Samuel Smith. '[Portrait of a Black Couple]' about 1873](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_133436t1v1_2000x2000.jpg?w=788)

![László Moholy-Nagy (American born Hungary, 1895-1946) '[The Law of the Series]' 1925 László Moholy-Nagy (American born Hungary, 1895-1946) '[The Law of the Series]' 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_05309301_2000x2000.jpg?w=764)

![Paul Wolff (German, 1887-1951) and Dr Wolff & Tritschler OHG (German, founded 1927, dissolved 1963) '[Dog at the beach]' 1936 Paul Wolff (German, 1887-1951) and Dr Wolff & Tritschler OHG (German, founded 1927, dissolved 1963) '[Dog at the beach]' 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_041552t1v1_2000x2000-1.jpg?w=780)

![Walker Evans (American, 1903 - 1975) '[Two Giraffes, Circus Winter Quarters, Sarasota]' 1941 Walker Evans (American, 1903 - 1975) '[Two Giraffes, Circus Winter Quarters, Sarasota]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_05269601_2000x2000.jpg?w=820)

![Myoung Ho Lee (South Korean, b. 1975) '[Tree #2]' 2006 Myoung Ho Lee (South Korean, b. 1975) '[Tree #2]' 2006](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/gm_31977201_2000x2000.jpg?w=822)

You must be logged in to post a comment.