Exhibition dates: 28th September 2010 – 30th January, 2011

Gerhard Gronfeld (German, 1911-2000)

Arrival at the transit camp

1942

Female forced labourers from the Soviet Union on their arrival at the Berlin-Wilhelmshagen Transit Camp, December 1942.

Source: Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

This is an emotional and sobering posting.

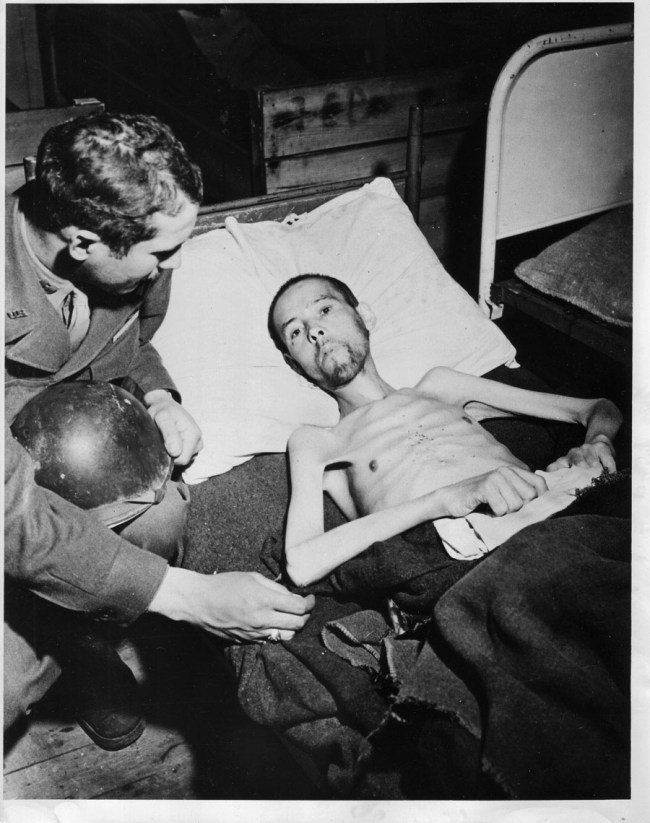

The photograph of the Liberated forced laborer with tuberculosis by an unknown photographer (1945, below) is as heartbreaking as the photograph of a mother and child, Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath, Minamata (1972) by Eugene Smith. The look on the man’s face when I first saw it made me burst into tears… it is difficult to talk about it now without being overcome. An unknown man photographed by an unknown photographer.

There is something paradoxical about the solidity of the doctor’s steel helmet, his uniform and the fact he is a doctor contrasted with the strength, size and gentleness of his hand as it rests near the elbow of this emaciated man, this human … yet the intimacy and tenderness of this gesture, as the man stares straight into the camera lens – is so touching that to look at this picture, is almost unbearable. Man’s (in)humanity to man.

Some pertinent facts

The Germans abducted about 12 million people from almost twenty European countries; about two thirds of whom came from Eastern Europe. Many workers died as a result of their living conditions, mistreatment or were civilian casualties of the war. They received little or no compensation during or after the war … At the peak of the war, one of every five workers in the economy of the Third Reich was a forced labourer. According to Fried, in January 1944 the Third Reich was relying on 10 million forced labourers. Of these, 6.5 million were civilians within German borders, 2.2 million were prisoners of war, and 1.3 million were located at forced labor camps outside Germany’s borders. Homze reported that civilian forced labourers from other countries working within the German borders rose steeply from 300,000 in 1939 to more than 5 million in 1944.

Examples

Russian Foreign Civilian Forced Labourers in Nazi Germany (total number approximately): 2,000,000

Russian Number of Known and Estimated Survivors Reported by Reconciliation Foundations: 334,500

(Source: Beyer, John C. and Schneider, Stephen A. “Forced Labour under Third Reich – Part 1” (pdf). Nathan Associates Inc.. 1999.)

Russian “volunteer” POW workers

“Between 22 June 1941 and the end of the war, roughly 5.7 million members of the Red Army fell into German hands. In January 1945, 930,000 were still in German camps. A million at most had been released, most of whom were so-called “volunteer” (Hilfswillige) for (often compulsory) auxiliary service in the Wehrmacht. Another 500,000, as estimated by the Army High Command, had either fled or been liberated. The remaining 3,300,000 (57.5 percent of the total) had perished.”

(Source: Streit, Christian. Keine Kameraden: Die Wehrmacht und die Sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen, 1941-1945, Bonn: Dietz (3. Aufl., 1. Aufl. 1978))

The remaining 3,300,000 had perished. A sobering figure indeed (if you can even imagine such a number of human beings).

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Jewish Museum in Berlin for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photograph for a larger version of the image.

Unknown photographer

Liberated forced laborer with tuberculosis

1945

A doctor of the U.S. Army examines a former forced labourer from Russia who was ill with tuberculosis. The Americans had discovered the sick forced labourers in a barrack yard in Dortmund. Dortmund, 30 April 1945.

Source: National Archives, Washington

Gerhard Gronfeld (German, 1911-2000)

Registration at the transit camp

1942

Berlin-Wilhelmshagen Transit Camp, December 1942. Labour office staff registered the forced labourers and handed out employment certificates.

Source: Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

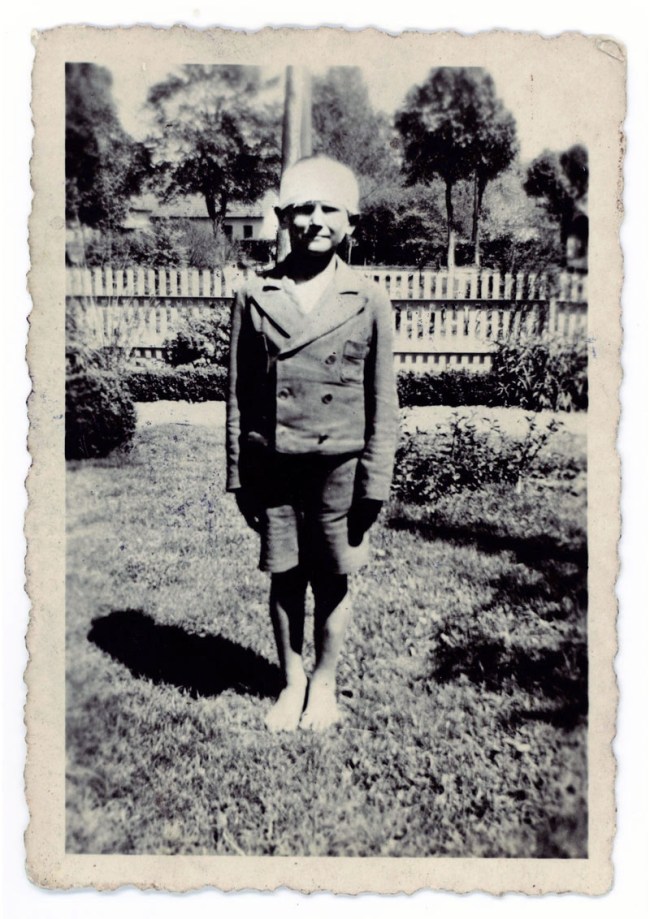

Unknown photographer

Humiliation of Bernhard Kuhnt in Chemnitz

Nd

The inscription, “Always dignified! The naval fleet’s mutineer Bernh. Kuhnt arrives at his new workplace (washing off the dirt),” refers to the myth that mutinous social democratic and communist sailors were responsible for the defeat of the German empire in the First World War.

Source: Bundesarchiv, Koblenz

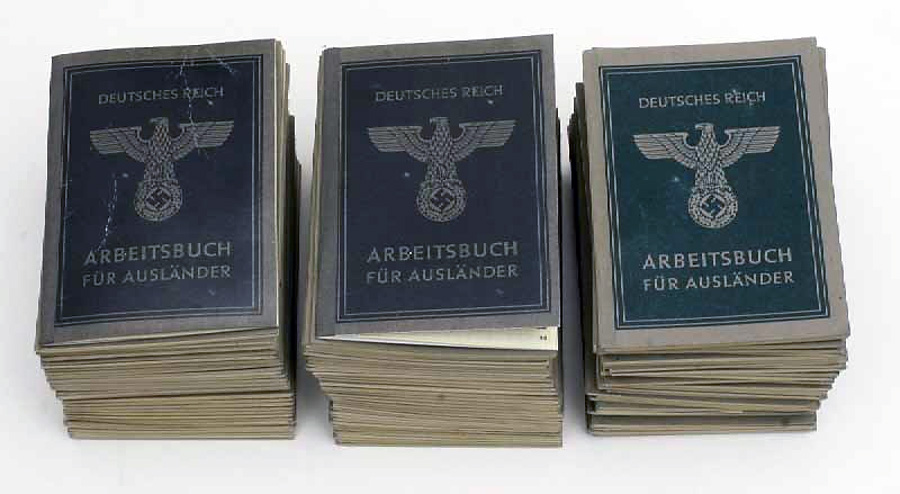

Workbooks issued by the employment office of the German Reich for foreign forced labourers; Buchenwald Concentration Camp Memorial, Weimar

Unknown photographer

Selection in a Prisoner of War Camp: Recruitment for Mining

1942

In the summer of 1942, Soviet prisoners of war were selected from the prisoner of war camp Zeithain to perform forced labor in Belgian mines.

Source: Gedenkstätte Ehrenhain Zeithain

Selection in a Prisoner of War Camp

In the summer of 1942, Karl Schmitt – head of the Wehrmacht mining division in Liège, Belgium – went to Berlin on vacation with his wife. On the way, he visited the Zeithain prisoner of war camp in Saxony. The Soviet POWs were ordered to present themselves for inspection with the aim of deploying them to Belgian mines under German control. They were accordingly checked for physical fitness. Karl Schmitt decided who was to be transported to Belgium and who was not.

Soviet prisoners of war were frequently put to work in mines. The Reich Security Main Office had ruled that they could be employed only in work gangs kept separate from German workers. The authorities considered the mines particularly suitable in that respect.

Source: Gedenkstätte Ehrenhain Zeithain.

Over 20 million men, women, and children were taken to Germany and the occupied territories from all over Europe as “foreign workers,” prisoners of war, and concentration camp inmates to perform forced labor. By 1942, forced labourers were part of daily life in Nazi Germany. The deported workers from all over Europe and Eastern Europe in particular were exploited in armament factories, on building sites and farms, as craftsmen, in public institutions and private households. Be it as a soldier of the occupying army in Poland or as a farmer in Thuringia, all Germans encountered forced labourers and many profited from them. Forced labor was no secret but a largely public crime.

The exhibition Forced Labor. The Germans, the Forced Laborers, and the War on view at the Jewish Museum in Berlin provides the first comprehensive presentation of the history of forced labor and its ramifications after 1945. The exhibition was curated by the Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation and initiated and sponsored by the “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” Foundation. Federal President Christian Wulff has assumed patronage for the exhibition. The exhibition’s first venue on its international tour is the Jewish Museum Berlin, other venues are planned in European capitals and in North America.

Forced labor was without precedent in European history. No other Nazi crime involved so many people – as victims, perpetrators, or onlookers. The exhibition provides the first comprehensive presentation of the history of this ubiquitous Nazi crime and its ramifications after 1945. It shows how forced labor was part of the Nazi regime’s racist social order from the outset: The propagated “Volksgemeinschaft” (people’s community) and forced labor for the excluded belonged together. The German “Herrenmenschen” (superior race) ruthlessly exploited those they considered “Untermenschen” (subhumans). The ordinariness and the broad societal participation of forced labor reflect the racist core of Nazism.

The exhibition pays special attention to the relationships between Germans and forced labourers. Every German had to decide whether to treat forced labourers with a residual trace of humanity or with the supposedly required racist frostiness and implacability of a member of an allegedly superior race. How Germans made use of the scope this framework reveals something not only about the individuals but also about the allure and shaping power of Nazi ideology and practice. Through this perspective, the exhibition goes beyond a presentation of forced labor in the narrow sense to illustrate the extent to which Nazi values had infiltrated German society. Forced labor cannot be passed off as a mere crime of the regime but should rather be considered a crime of society.

Over 60 representative case histories form the core of the exhibition. As is true of the majority of documents on show, they resulted from meticulous investigations in Europe, the USA, and Israel. Moreover the exhibition team viewed hundreds of interviews with former forced labourers that have been carried out in recent years. In terms of content, these case histories range from the degrading work of the politically persecuted in Chemnitz through the murderous slave labor performed by Jews in occupied Poland to daily life as a forced labourer on a farm in Lower Austria.

Among the surprises of the extensive international archival research was discovering unexpectedly broad photographic coverage of significant events. The photos relating to the case histories represent the second pillar of the exhibition. Whole series of photos were traced back to their creator and the scene and people depicted. This presentation, based on well-founded sources, allows quasi dramatic insight into aspects of forced labor. Cinematically arranged photo or photo-detail enlargements form the introduction to the continued inquiry into the history of forced labor.

The exhibition is divided into four sections. The first covers the years from 1933 to 1939 and unveils in particular how the racist ideology of Nazi forced labor struck roots. What was propagated up to the beginning of WWII, partly laid down in laws and widely implemented by society in practice, formed the basis for the subsequent radicalisation of forced labor in occupied Europe culminating in extermination through labor. This escalation and radicalisation is the focus of the second section of the exhibition. The third part covers forced labor as a mass phenomenon in the Third Reich from 1941/1942, ending with the massacre of forced labourers at the end of the war. The fourth section explores the period from the time of liberation in 1945 to society’s analysis and recognition of forced labor as a crime today. Former forced labourers have the last word.

Press release from The Jewish Museum website

Unknown photographer

Daimler facility in Minsk

1942

Female forced laborers of the Daimler facility in Minsk, September 1942.

Source: Mercedes-Benz Classic, Archive, Stuttgart

Minsk: German firms in occupied Eastern Europe

In Minsk, a town which had suffered major destruction, Daimler-Benz ran a large repair facility for motorised Wehrmacht vehicles. Together, Daimler and Organisation Todt set up more than thirty repair sheds on the grounds of a ruined military base. With a workforce of five thousand, the facility was soon one of the largest enterprises in occupied Eastern Europe. The management exploited prisoners of war and members of the local population, among them Jews. Labourers were also deported from White Russian villages to the Minsk works as part of the effort to crush the partisan movement.

In the occupied areas of Eastern Europe, many German companies took advantage of the opportunity to take over local firms or establish branch operations. The unlimited availability of labourers was an important factor in their business strategies.

Unknown photographer

Foreign workers at BMW in Allach

c. 1943

All the foreigners in aircraft engine production had to be visibly identifiable as such. The Soviet prisoners of war had the “SU” symbol on their jackets. Concentration camp inmates could be recognised by their striped uniforms. These photographs were most likely propaganda photos. Munich-Allach, c. 1943.

Source: BMW Group Archiv.

Munich-Allach: Working for BMW

Toward the end of the war ninety percent of the workforce at the largest aircraft engine factory in the German Reich – BMW’s plant in Munich-Allach – consisted of foreign civilian workers, POWs and concentration camp inmates. The number of workers had risen from 1,000 in 1939 to more than 17,000 in 1944.

Forced labourers worked not only in the assembly halls, but also on the factory’s expansion. Due to BMW’s importance to the armament industry, the authorities gave it priority over other companies in the assignment of workers. Nevertheless, its personnel demand was never completely met.

Some of the Western European workers lived in private quarters. For all others, barrack camps were set up all around the factory grounds until 1944, ultimately accommodating 14,000 people. That figure included several thousand concentration camp inmates which the company management had applied for already in 1942.

Unknown photographer

KZ-prisoners on the industrial union color building site, Auschwitz

c. 1943

Source: © Bundesarchiv, Koblenz

Unknown photographer

Liberated Jewish women

1945

These young Jewish women were released from a forced labor camp at Kauritz (Saxony) by U.S. Army troops in early April, 1945. They are part of a large group removed from homes in France, Holland, Belgium and other occupied areas in Europe.

Source: National Archives, Washington

Unknown photographer

Wladyslaw Kolopoleski

Nd

“In addition to the hard work, which exceeded my strength, I was beaten on the slightest provocation, sometimes to the point of unconsciousness. Once, for example, I suffered a severe head injury after I was beaten by Max Ewert, an SA officer. I not only lost consciousness, but I had to have head surgery,” wrote Władysław Kołopoleski, a young Pole born in Łódź in 1932. He was deployed in April 1940 on the estate of mayor Max Ewert in Gervin, now Górawino, in Pomerania.

Source: Foundation “Polish-German Reconciliation,” Warsaw

Jewish Museum Berlin

Lindenstraße 9-14, 10969 Berlin

Phone: +49 (0)30 259 93 300

Opening hours:

10am – 7pm

![Laurenz Berges (German, b. 1966) 'Garzweiler' [surface mine] 2003 from the exhibition 'presentation/representation: photography from Germany' at the Monash Gallery of Art, Melbourne, July - August, 2009 Laurenz Berges (German, b. 1966) 'Garzweiler' [surface mine] 2003 from the exhibition 'presentation/representation: photography from Germany' at the Monash Gallery of Art, Melbourne, July - August, 2009](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/laurenz-berges-garzweiler-web-1.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.