Exhibition dates: 9th March – 29th May, 2017

Curator: Sarah Howgate, Senior Curator of Contemporary Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, London

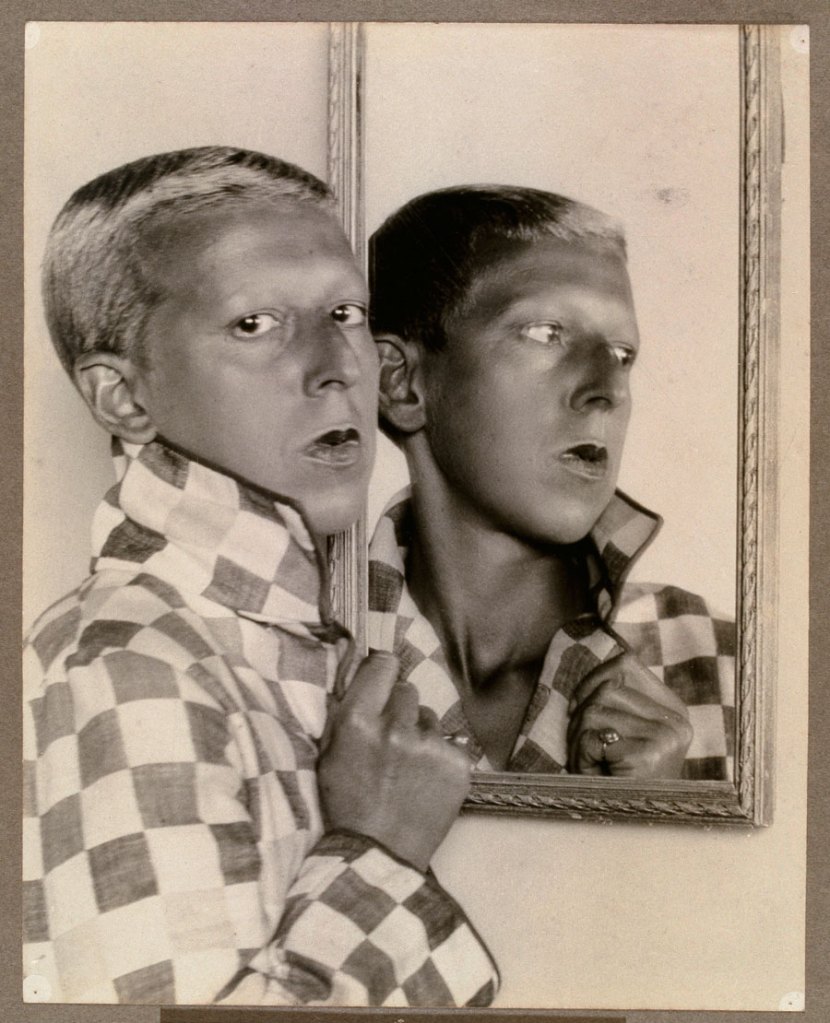

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait (reflected image in mirror with chequered jacket)

1927

Silver gelatin print

“… the life of spirit is not the life that shrinks from death and keeps itself untouched by devastation, but rather the life that endures it and maintains itself in it. It wins its truth only when, in utter dismemberment, it finds itself. It is this power, not as something positive, which closes its eyes to the negative as when we say of something that it is nothing or is false, and then having done with it, turn away and pass on to something else; on the contrary, spirit is this power only by looking the negative in the face, and tarrying with it. This tarrying with the negative is the magical power that converts it into being.”

George Wilhelm Frederich Hegel, 1807. Phenomenology of Spirit, Preface (trans. A. V. Miller 1977), Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 10

This is an interesting pairing for an exhibition but the connection between the artists is unconvincing. This is because Wearing and Cahun are talking to different aspects of the self.

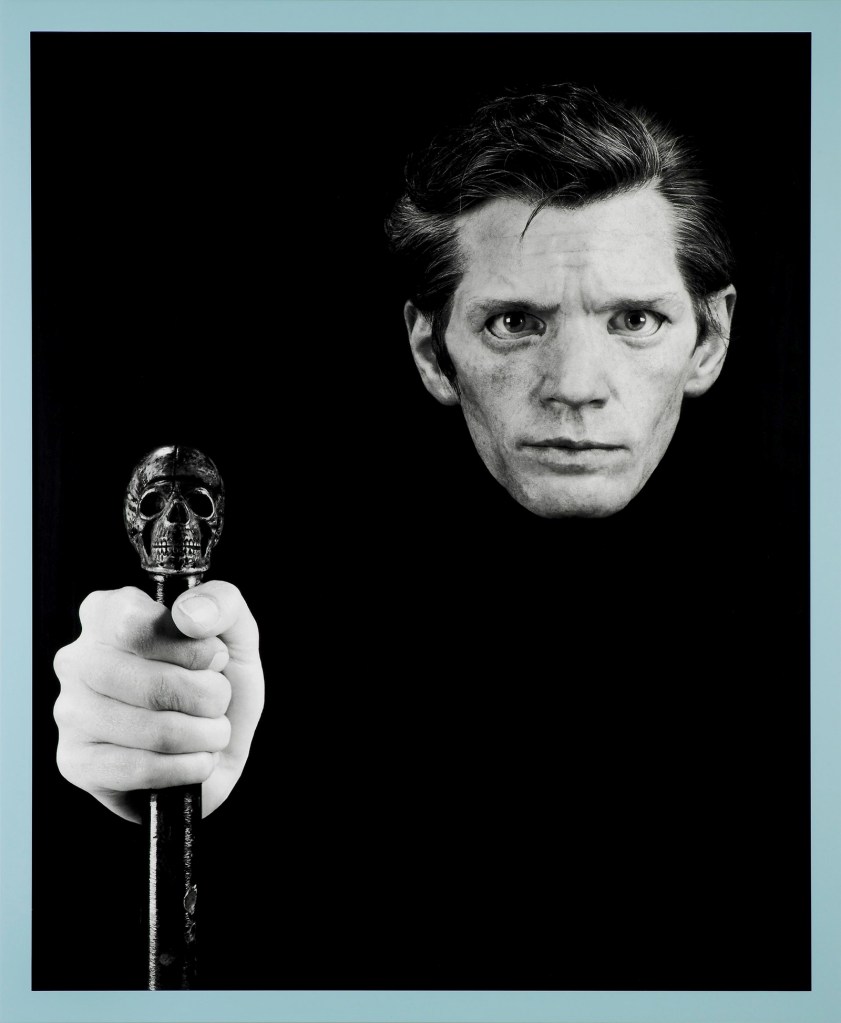

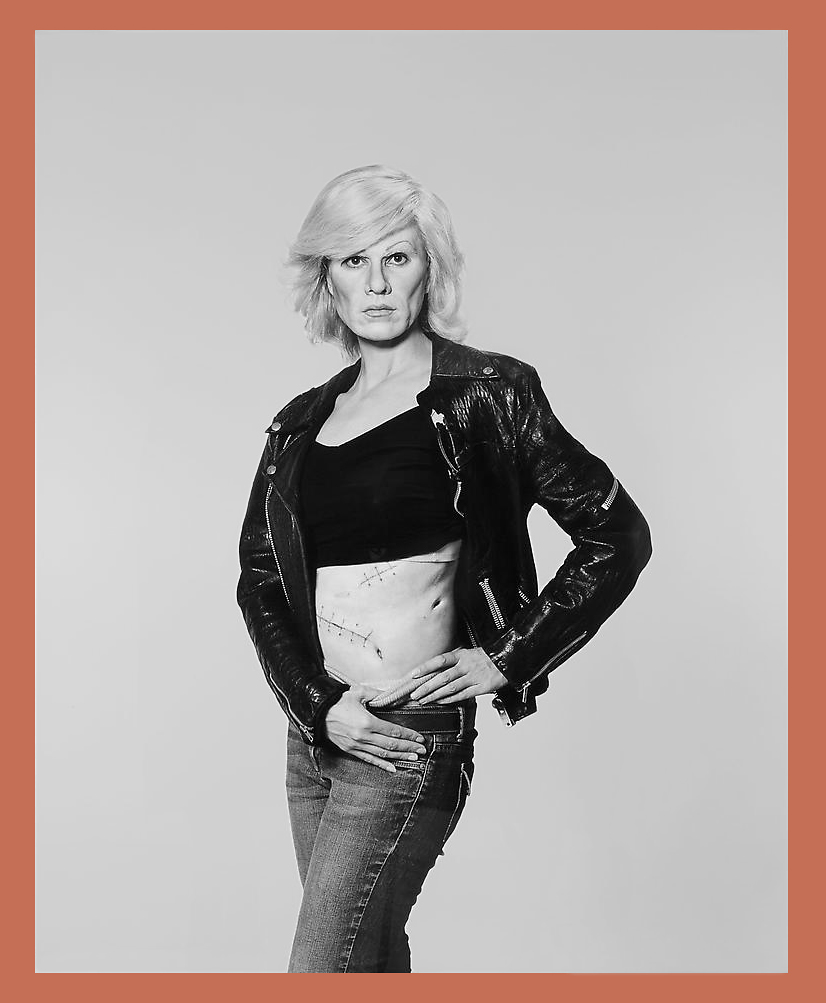

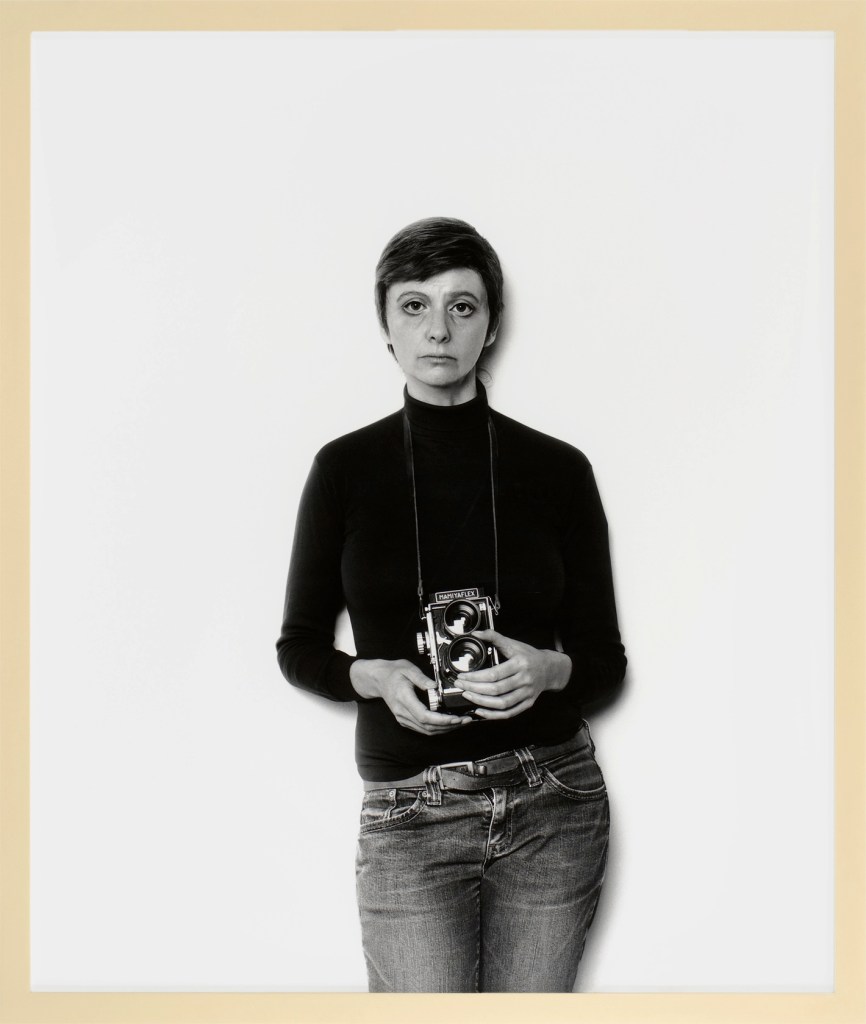

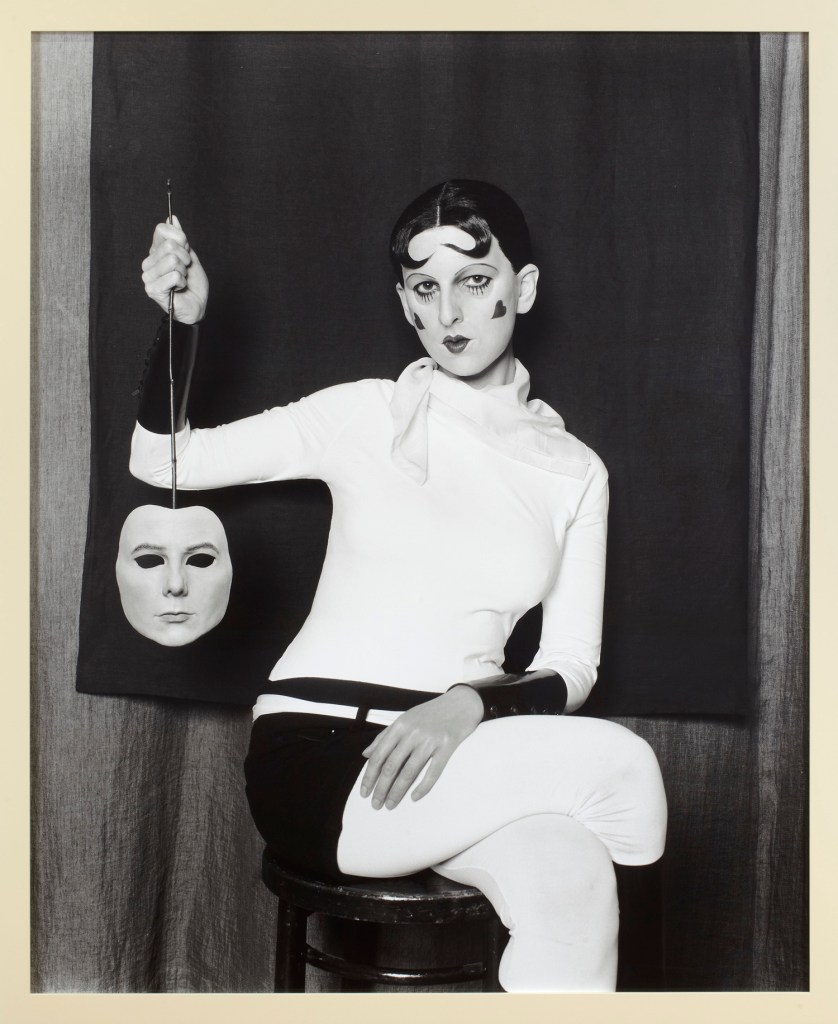

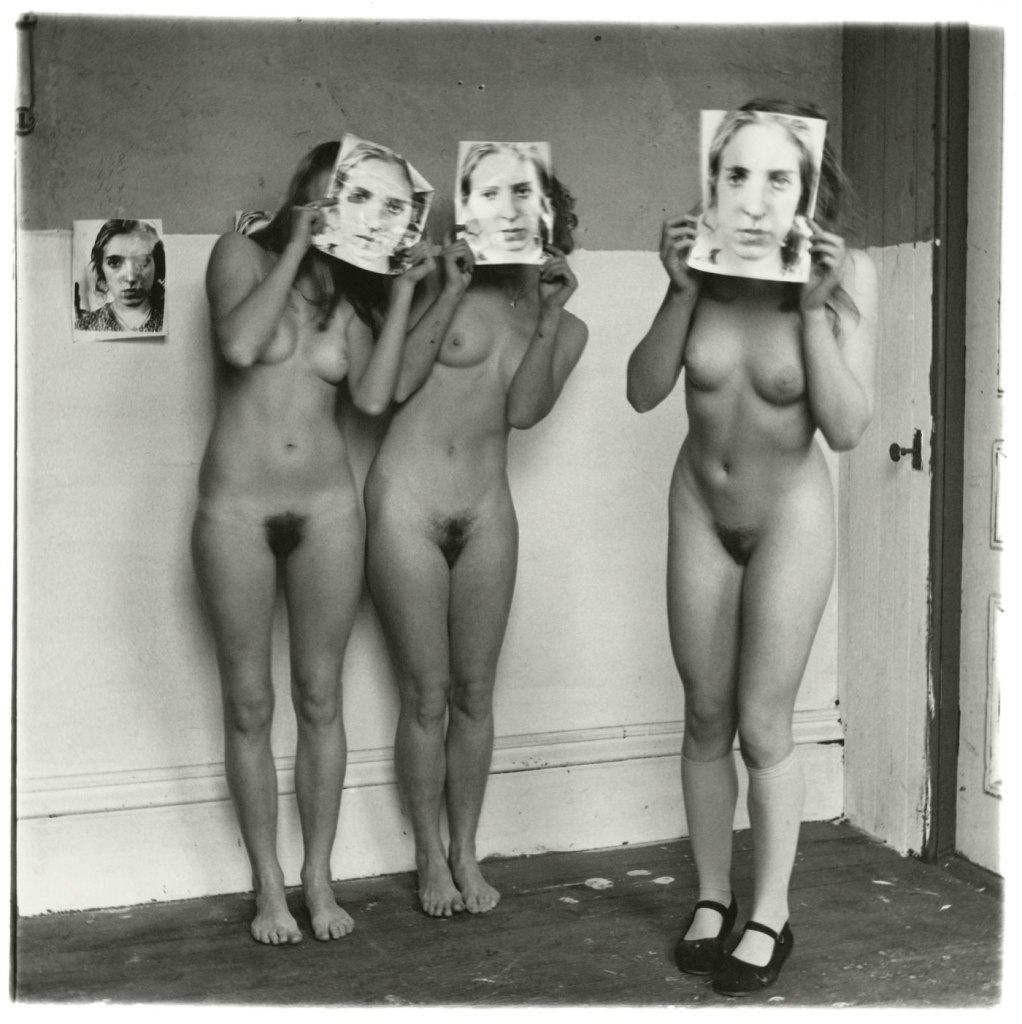

Wearing’s self-portraits, her mask-querades, her shielded multiple personalities, talk to a “postmodern meditation on the slipperiness of the self” in which there is little evidence of the existence of any “real” person. Wearing wears her identities in a series of dress-ups, performances where only the eyes of the original protagonist are visible. These identities evidence Jung’s shadow aspect, “an unconscious aspect of the personality which the conscious ego does not identify in itself.” Rather than an assimilation of the shadow aspect into the self followed by an ascent (enantiodromia), Wearing’s images seem to be mired in a state of melancholia, a “confrontation with the shadow which produces at first a dead balance, a stand-still that hampers moral decisions and makes convictions ineffective… tenebrositas, chaos, melancholia.” This is not a confrontation that leads anywhere interesting, by looking the negative in the face and tarrying with it. These split personalities rise little above caricature, an imitation of a person in which certain striking characteristics are over emphasised, such as in Wearing’s portraits of her as Andy Warhol or Robert Mapplethorpe. To me, the photograph of Wearing as Mapplethorpe is a travesty of the pain that artist was feeling as he neared the end of his life, dying from HIV/AIDS.

Cahun’s self-portraits contain all the depth of feeling and emotion that Wearing’s can never contain. Here, identity and gender is played out through performance and masquerade in a constructive way, a deep, probing interrogation of the self in front of the camera. While Cahun engages with Surrealist ideas – wearing masks and costumes and changing her appearance, often challenging traditional notions of gender representation – she does so in a direct and powerful way. As Laura Cumming observes, “She is not trying to become someone else, not trying to escape [as Wearing is]. Cahun is always and emphatically herself. Dressed as a man, she never appears masculine, nor like a woman in drag. Dressed as a woman, she never looks feminine. She is what we refer to as non-binary* these days, though Cahun called it something else: “Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.””

*Those with non–binary genders can feel that they: Have an androgynous (both masculine and feminine) gender identity, such as androgyne. Have an identity between male and female, such as intergender. Have a neutral or unrecognised gender identity, such as agender, neutrois, or most xenogenders.*

Cahun had a gift for the indelible image but more than that, she possesses the propensity for humility and openness in these portraits, as though she is opening her soul for interrogation, even as she explores what it is to be Cahun, what it is to be human. This is a human being in full control of the balance between the ego and the self, of dream-state and reality. The photographs, little shown in Cahun’s lifetime, are her process of coming to terms with the external world, on the one hand, and with one’s own unique psychological characteristics on the other. They are her adaption** to the world.

**“The constant flow of life again and again demands fresh adaptation. Adaptation is never achieved once and for all.” (Carl Jung. “The Transcendent Function,” CW 8, par. 143.)**

Claude Cahun is person I would have really liked to have met. Affiliated with the French Surrealist movement, living with her partner the artist and stage designer Marcel Moore, the two women left Paris for the Isles of Scilly and were then imprisoned in Nazi-occupied Jersey during the Second World War as a result of their roles in the French Resistance.

“Fervently against war, the two worked extensively in producing anti-German fliers. Many were snippets from English-to-German translations of BBC reports on the Nazis’ crimes and insolence, which were pasted together to create rhythmic poems and harsh criticism. The couple then dressed up and attended many German military events in Jersey, strategically placing them in soldier’s pockets, on their chairs, etc. Also, they inconspicuously crumpled up and threw their fliers into cars and windows. In many ways, Cahun and Malherbe’s [Marcel Moore] resistance efforts were not only political but artistic actions, using their creative talents to manipulate and undermine the authority which they despised. In many ways, Cahun’s life’s work was focused on undermining a certain authority, however her specific resistance fighting targeted a physically dangerous threat. In 1944 she was arrested and sentenced to death, but the sentence was never carried out. However, Cahun’s health never recovered from her treatment in jail, and she died in 1954.” (Wikipedia)

Undermining a certain authority … while ennobling her own identity and being. Love and respect.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Portrait Gallery, London for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. For more information please see the blog entry by Louise Downie. “Claude Cahun: Freedom Fighter” on the National Portrait Gallery Blog 09 May 2017.

“Under this mask, another mask. I will never finish removing all these faces.”

Claude Cahun, 1930

This exhibition brings together for the first time the work of French artist Claude Cahun and British contemporary artist Gillian Wearing. Although they were born almost seventy years apart and came from different backgrounds, remarkable parallels can be drawn between the two artists. Both of them share a fascination with the self-portrait and use the self-image, through the medium of photography, to explore themes around identity and gender, which is often played out through masquerade and performance.

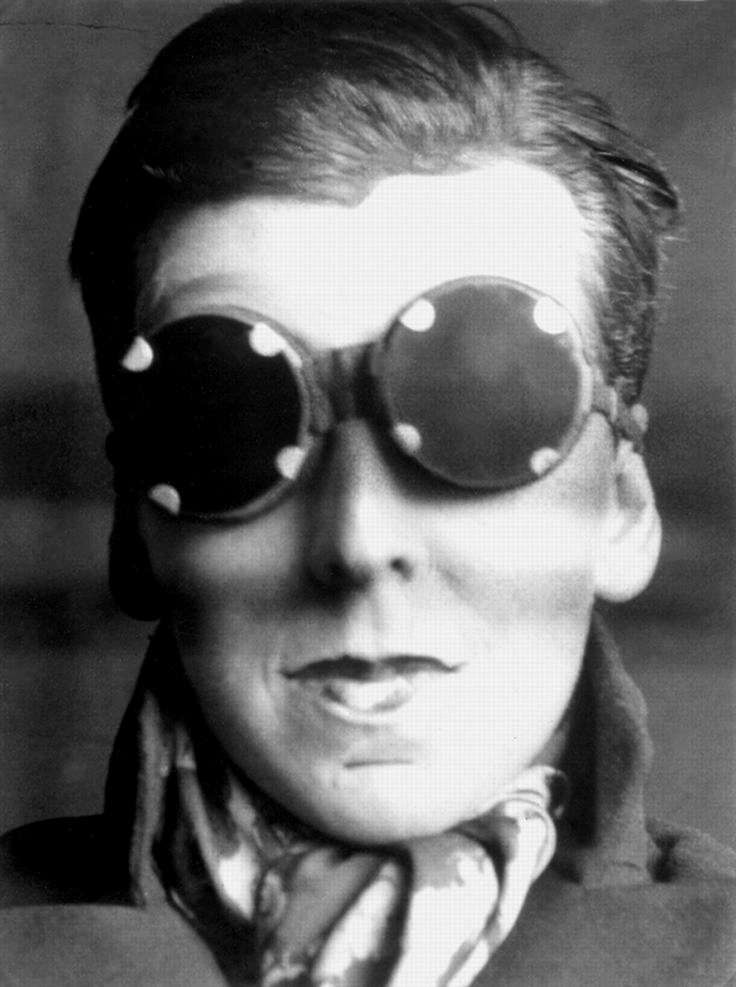

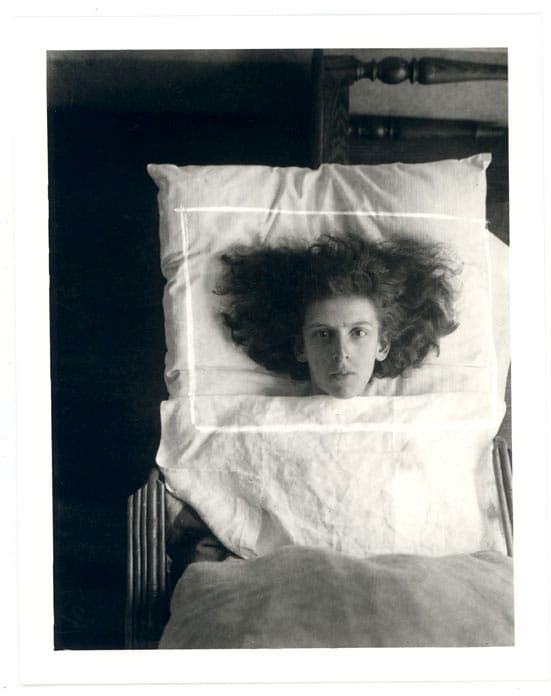

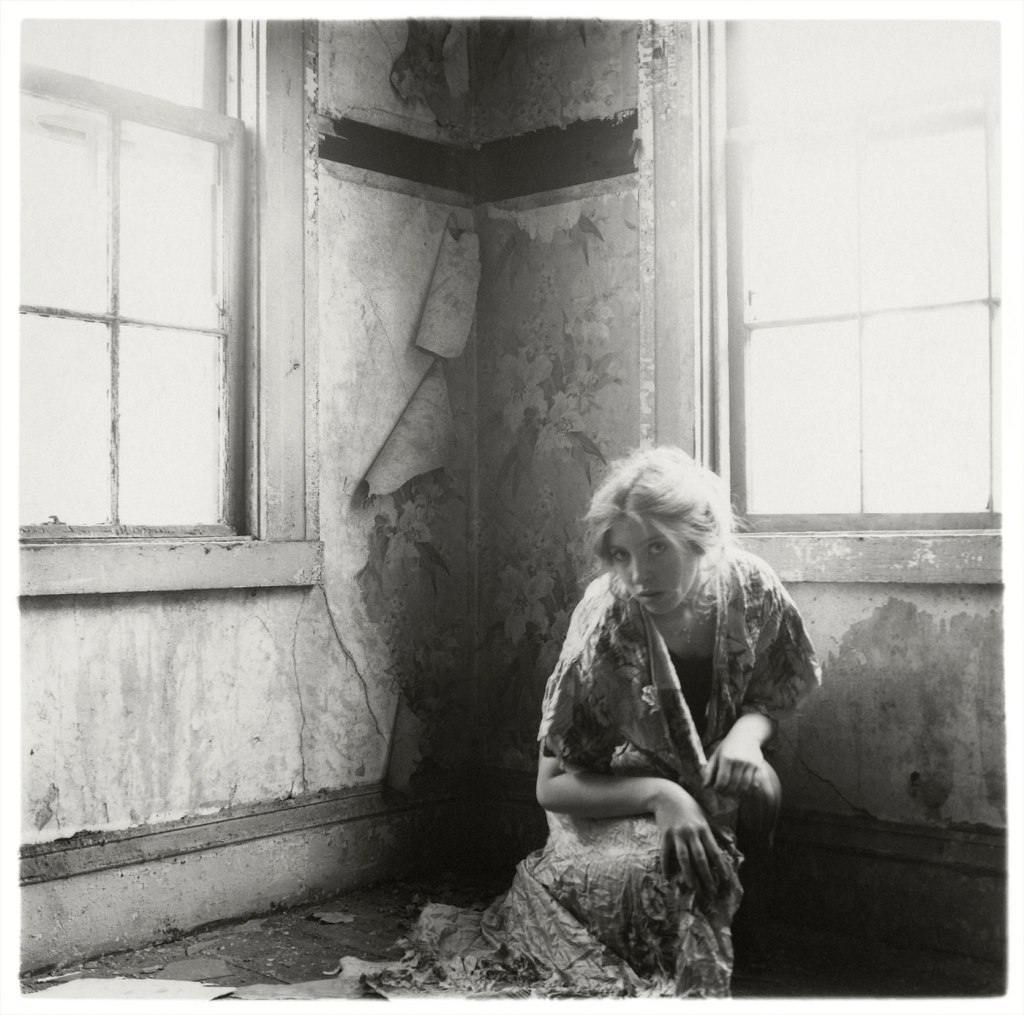

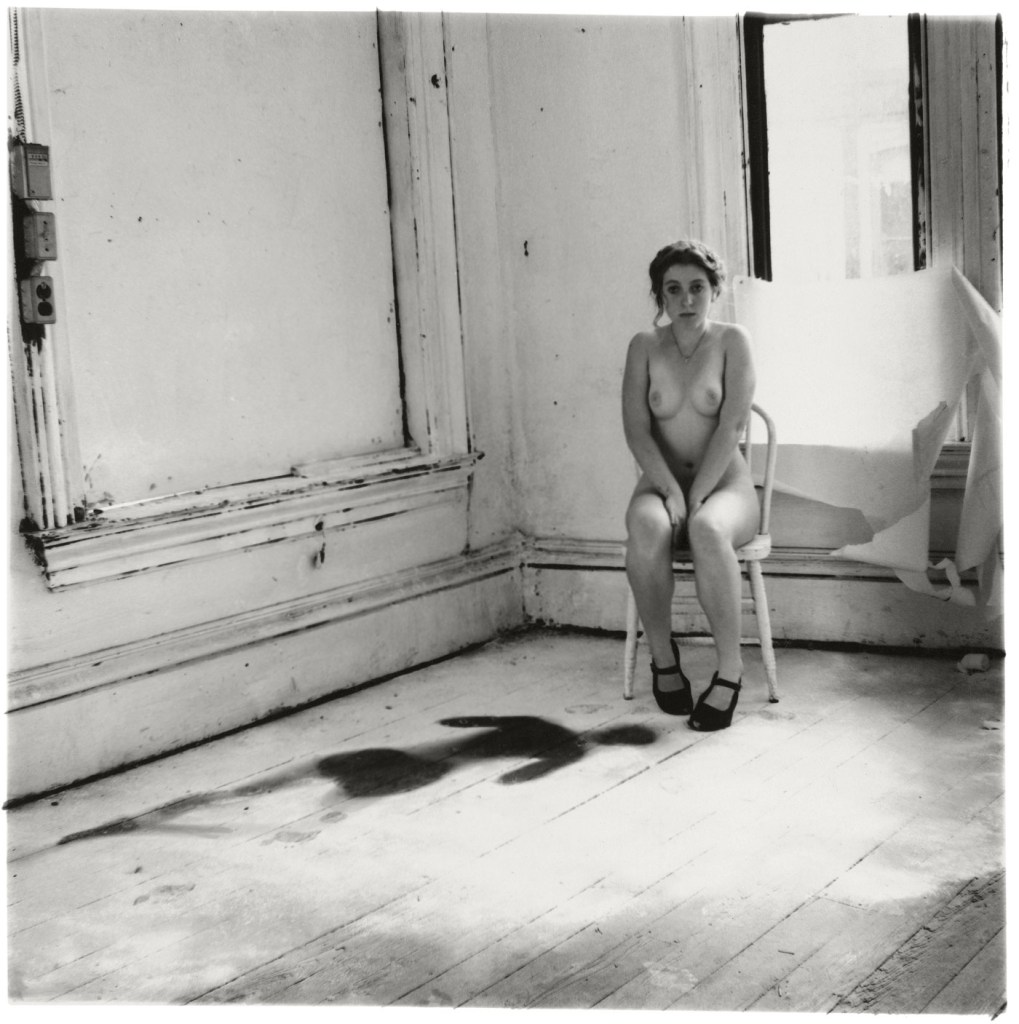

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Autoportrait

1928

Gelatin silver print

13.9 x 9cm

Jersey Heritage Collection

© Jersey Heritage

“Once seen, never forgotten: Cahun had a gift for the indelible image. Even when the signals are jammed, and the meaning deliberately baffled, her vision always holds strong. This is partly convenienced by the artist’s exceptional looks. Her long, thin face, with its shaved eyebrows, large eyes and linear nose, takes paint like a canvas. She converts herself into a harpy, a lunatic or a doll with equal ease. In one self-portrait, she even holds her own bare face like a mask…

Peering into these monochrome images, so delicate and small, the viewer might inevitably wonder which is the real Cahun: the woman in the aviator goggles, the pensive Buddhist, the young man in a white silk scarf? But this is not the right question. She is not trying to become someone else, not trying to escape. Cahun is always and emphatically herself.

Dressed as a man, she never appears masculine, nor like a woman in drag. Dressed as a woman, she never looks feminine. She is what we refer to as non-binary these days, though Cahun called it something else: “Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” …

There is little evidence that she ever displayed these photographs, which were forgotten for decades after her death. It seems that her partner was generally behind the lens, but we know almost nothing about how they were made. Of her lifelong project, Cahun wrote: “Under this mask, another mask. I will never finish removing all these faces.”

Commentators have taken this to mean that she thought of herself as a series of multiple personalities, and the double exposures, shadows and reflections in her work all seem to undermine the idea of a singular self. Yet Cahun is formidably and unmistakably Cahun, her force of personality registering every time in that utterly penetrating look. Far from some postmodern meditation on the slipperiness of the self, her images are completely direct. They acknowledge the sufferings of a double life and are deepened by them every time; and yet they rejoice in that life too.”

Laura Cumming. “Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the Mask, Another Mask – review,” on The Observer website Sunday 12 March 2017 [Online] Cited 17/12/2021

Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask

This exhibition brings together for the first time the work of French artist Claude Cahun and British contemporary artist Gillian Wearing. Although they were born almost seventy years apart and came from different backgrounds, remarkable parallels can be drawn between the two artists. Both of them share a fascination with the self-portrait and use the self-image, through the medium of photography, to explore themes around identity and gender, which is often played out through masquerade and performance.

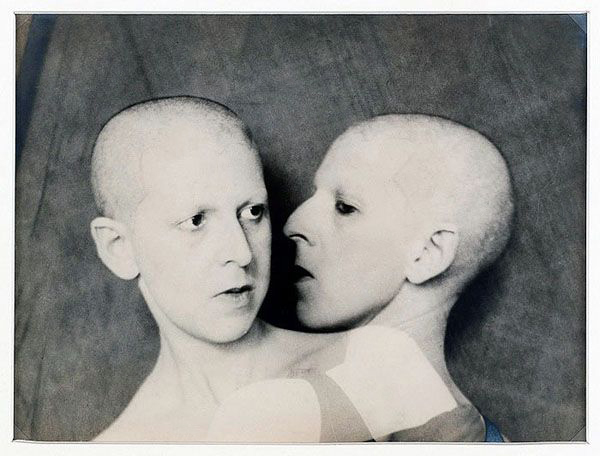

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) in collaboration with Marcel Moore (French, 1892-1972)

Aveux non avenus frontispiece

1929-1930

Photomontage

Silver gelatin print

Jersey Heritage Collections

© Jersey Heritage

“Cahun appears in enigmatic guises, playing out different personas using masks and mirrors, and featuring androgynous shaven or close-cropped hair – as can be seen in the multiple views of her in the lower left-hand side of this collage. The image also includes symbols made up by the women to represent themselves – the eye for Moore, the artist, and the mouth for Cahun, the writer and actor. Whereas the majority of Surrealists were men, in whose images women appear as eroticised objects, Cahun’s androgynous self-portraits explore female identity as constructed, multifaceted, and ultimately as having a nihilistic absence at the core.”

Ron Radford (ed), Collection highlights: National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2008

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait (as a dandy, head and shoulders)

1921-1922

Silver gelatin print

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection

Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence

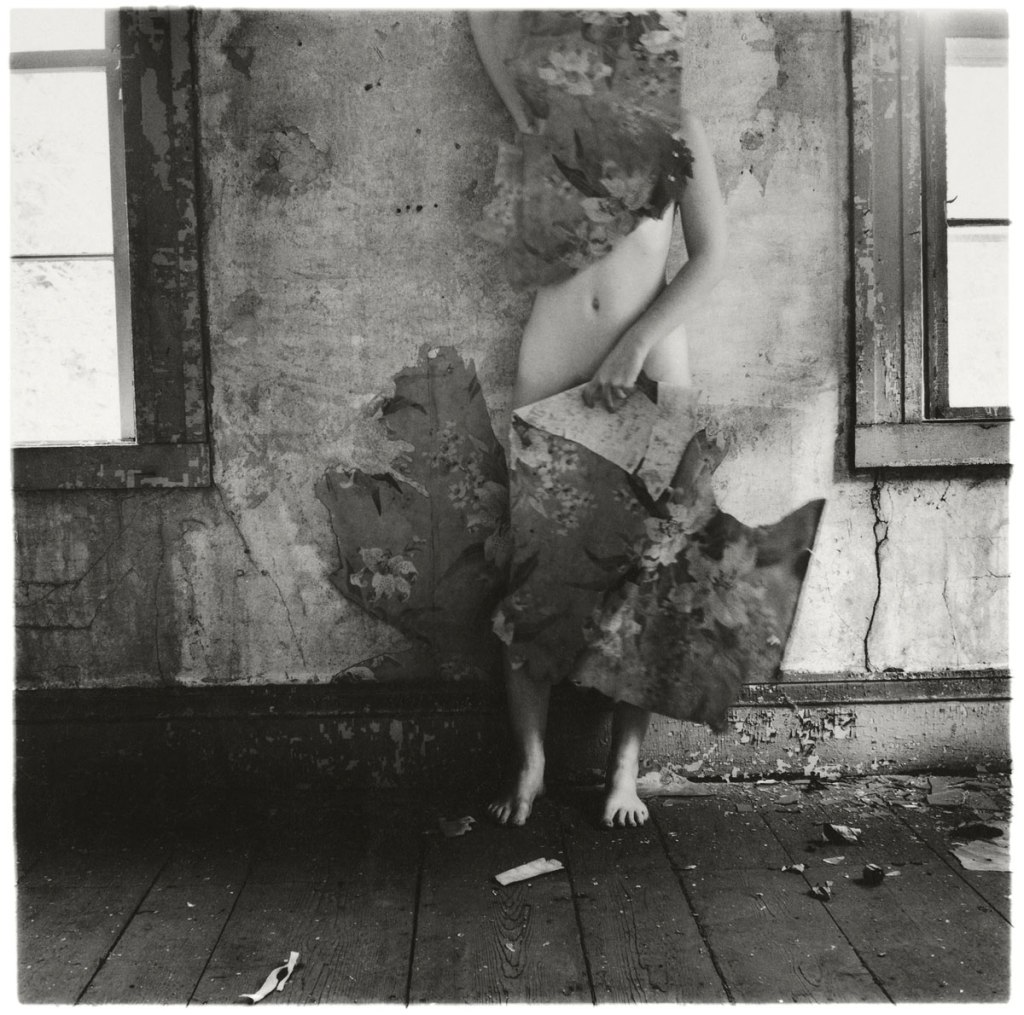

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Studies for a keepsake

c. 1925

Silver gelatin prints

Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris

© Musée d’Art moderne / Roger-Viollet

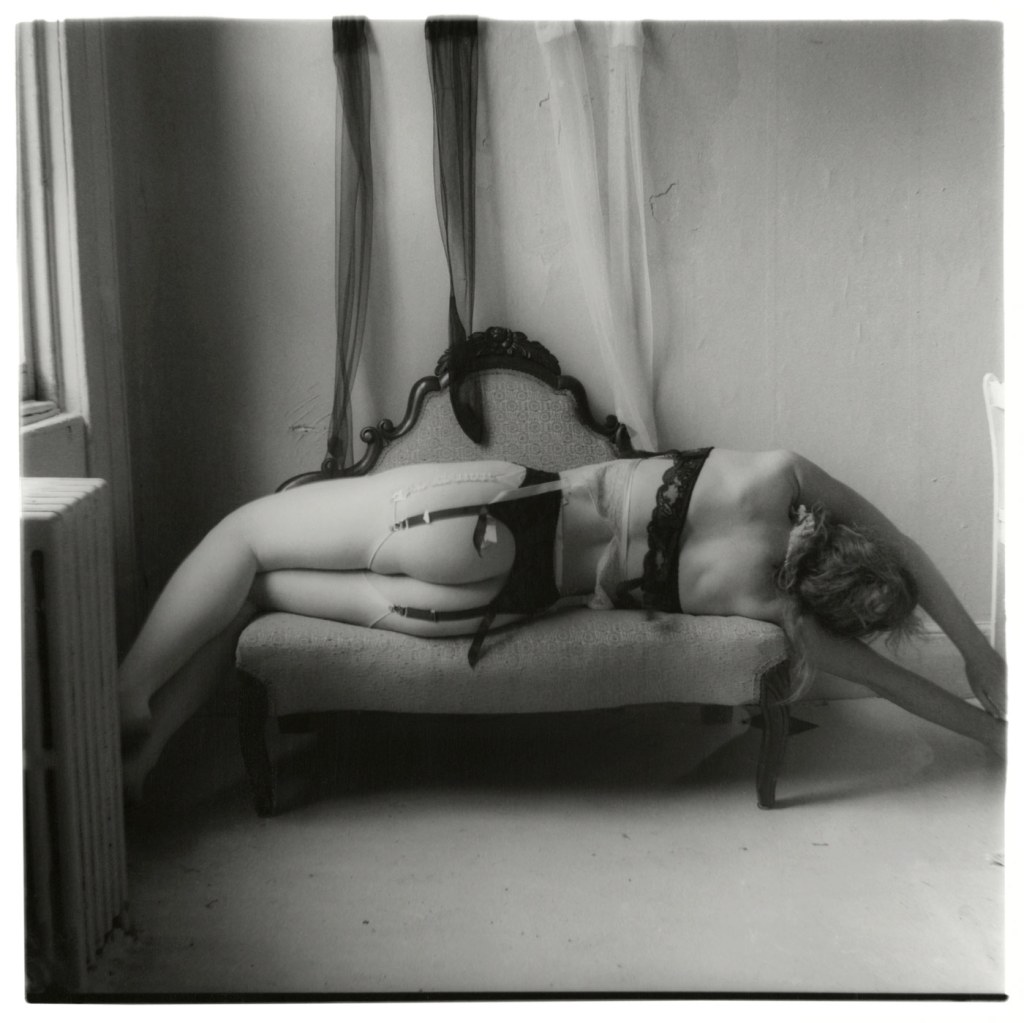

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Study for a keepsake

c. 1925

Silver gelatin print

Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris

© Musée d’Art moderne / Roger-Viollet

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

I am in training don’t kiss me

c. 1927

Silver gelatin print

117mm x 89mm (whole)

Jersey Heritage Collections

© Jersey Heritage

Totor (progenitor of Tintin) and Popol are two comic characters by the Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Castor and Pollux are the twin stars; Pollux and Helen were the children of Zeus and Leda, while Castor and Clytemnestra were the children of Leda and Tyndareus.

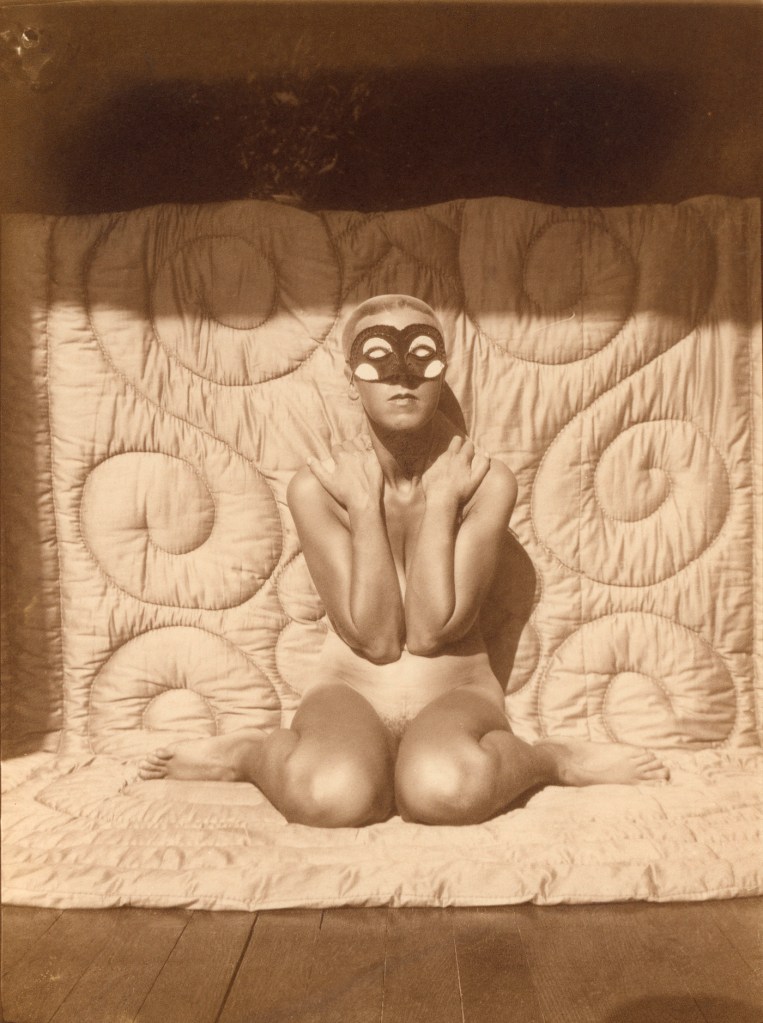

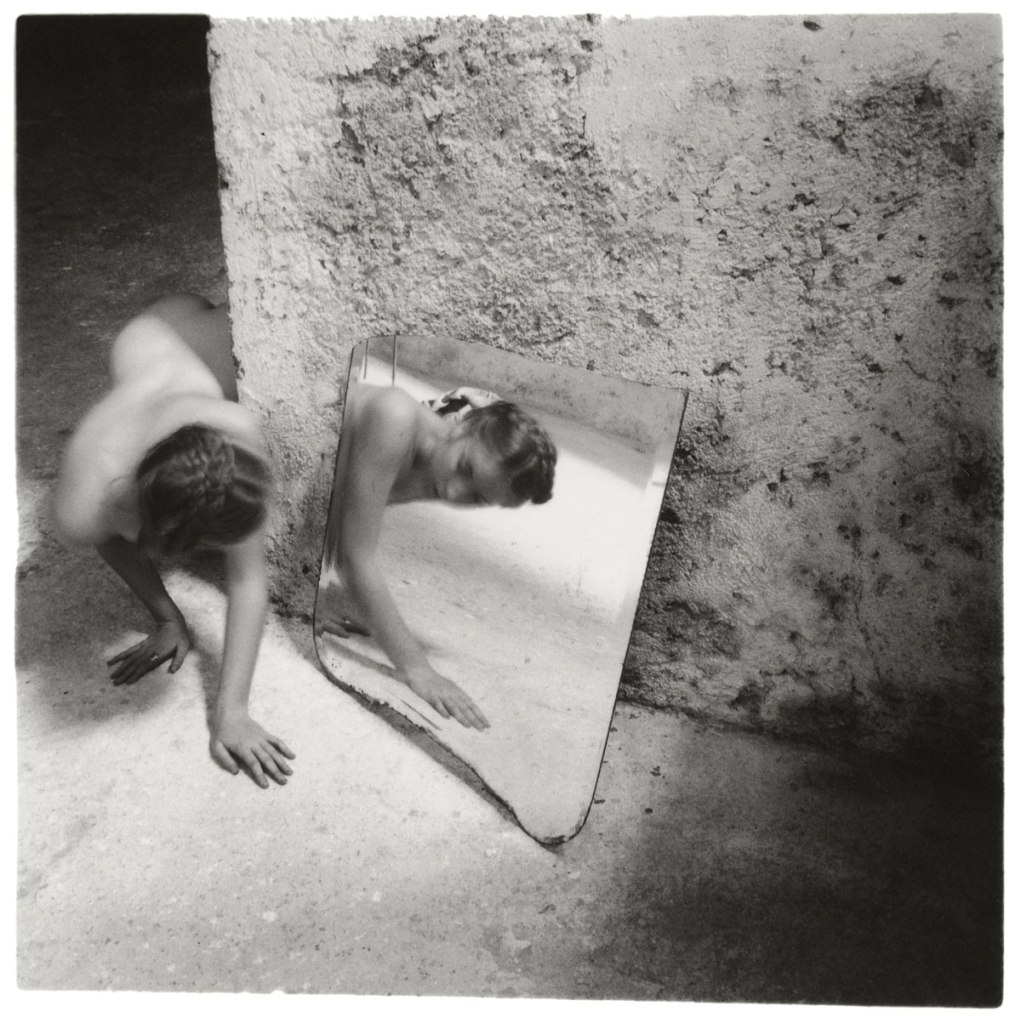

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait (kneeling, naked, with mask)

c. 1928

Silver gelatin print

116mm x 83mm

Jersey Heritage Collections

© Jersey Heritage

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait (full length masked figure in cloak with masks)

1928

Silver gelatin print

109 x 82mm

Jersey Heritage Collections

© Jersey Heritage

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait

1929

Silver gelatin print

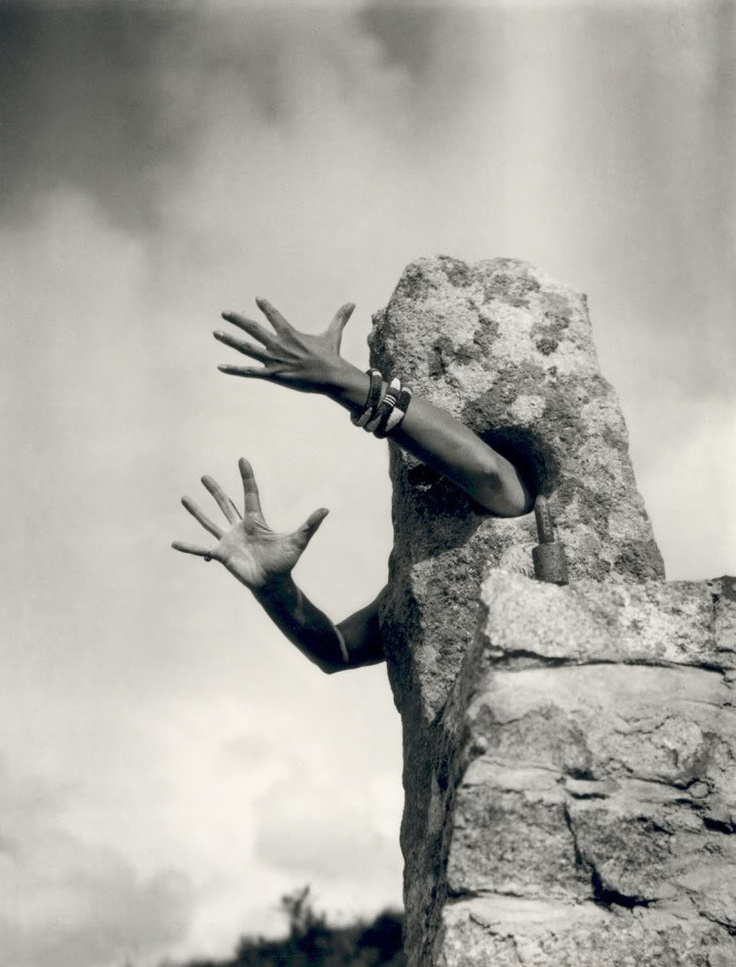

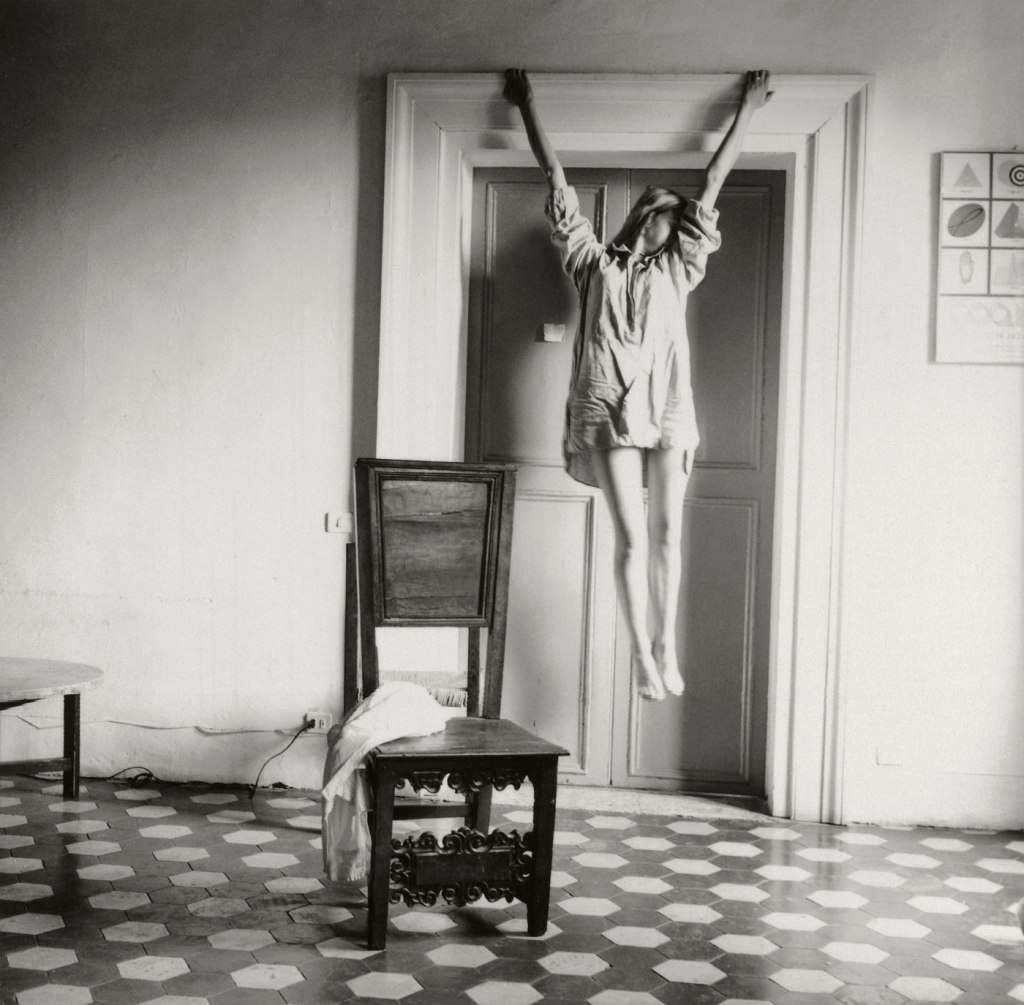

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Je tends les bras (I extend my arms)

c. 1932

Silver gelatin print

Jersey Heritage Collections

© Jersey Heritage

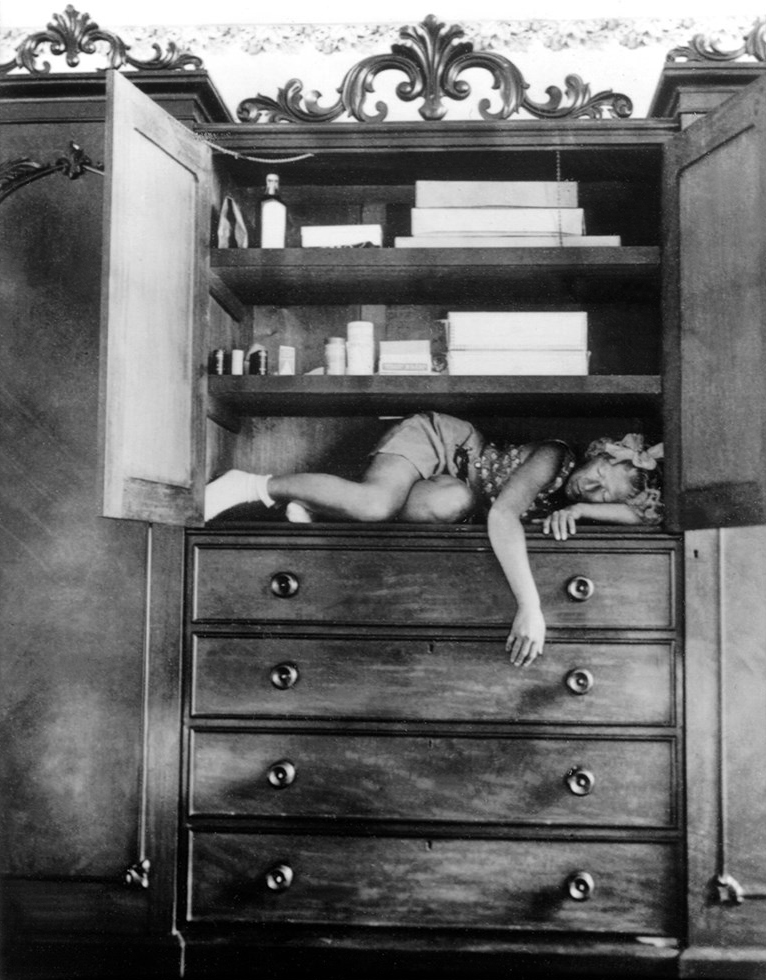

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait (in cupboard)

c. 1932

Silver gelatin print

Jersey Heritage Collections

© Jersey Heritage

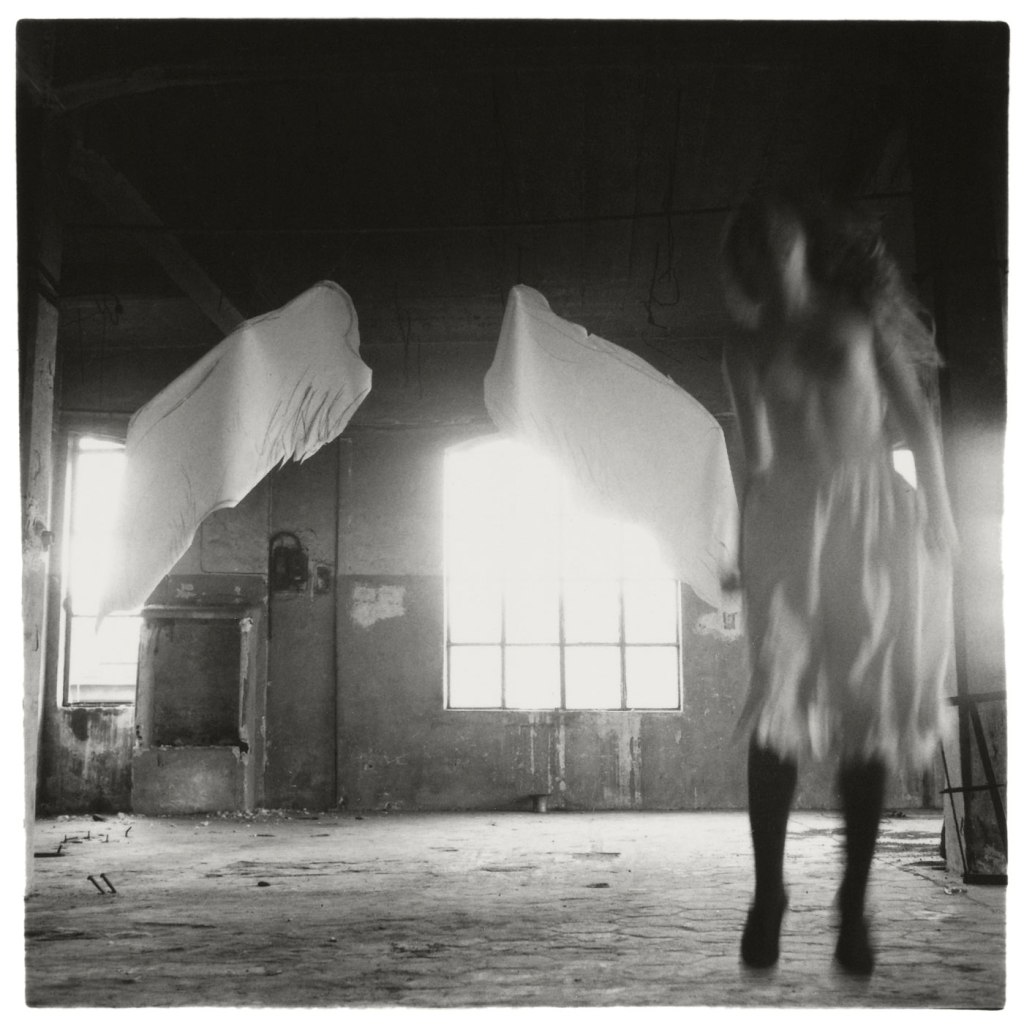

Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask (9 March – 29 May 2017) draws together over 100 works by French artist Claude Cahun (1894-1954) and British contemporary artist Gillian Wearing (b.1963). While they were born 70 years apart, they share similar themes of gender, identity, masquerade and performance.

Cahun, along with her contemporaries André Breton and Man Ray, was affiliated with the French Surrealist movement although her work was rarely exhibited during her lifetime. Together with her partner, the artist and stage designer Marcel Moore, the two women left Paris and were then imprisoned in Nazi-occupied Jersey during the Second World War as a result of their roles in the French Resistance. In her photographs she is depicted wearing masks and costumes and engaging with Surrealist ideas. She also changes her appearance by shaving her hair and wearing wigs, often challenging traditional notions of gender representation.

Gillian Wearing studied at Goldsmiths University, winning the Turner Prize in 1997. She has exhibited extensively in the United Kingdom and internationally, including solo exhibitions at the Whitechapel Gallery and Serpentine Gallery, whilst overseas, recent retrospectives include IVAM Valencia and K20 Dusseldorf. Wearing’s photographic self-portraits incorporate painstaking recreations of her as others in an intriguing and sometimes unsettling range of guises such as where she becomes her immediate family members using prosthetic masks.

Despite their different backgrounds, obvious and remarkable parallels can be drawn between the artists whose fascination with identity and gender is played out through performance and masquerade. Wearing has referenced Cahun overtly in the past: Me as Cahun holding a mask of my face is a reconstruction of Cahun’s self-portrait Don’t kiss me I’m in training of 1927, and forms the starting point of this exhibition, the title of which (Behind the mask, another mask) adapts a quotation from Claude Cahun’s Surrealist writings.

Dr Nicholas Cullinan, Director, National Portrait Gallery, London, says: ‘This inspired, timely and poignant exhibition pairs the works of Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun. These pioneering artists, although separated by several decades, address similarly compelling themes around gender, identity, masquerade, performance and the idea of the self, issues that are ever more relevant to the present day.’

Sarah Howgate, Curator, Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask, says: ‘It seems particularly fitting that at the National Portrait Gallery on International Women’s Day we are bringing together for the first time Claude Cahun’s intriguing and complex explorations of identity with the equally challenging and provocative self-images of Gillian Wearing.’

Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask is curated by Sarah Howgate, Senior Curator of Contemporary Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait as a young girl

1914

Silver gelatin print

Jersey Heritage Collections

© Jersey Heritage

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait as a young girl

1914

Silver gelatin print

Jersey Heritage Collections

© Jersey Heritage

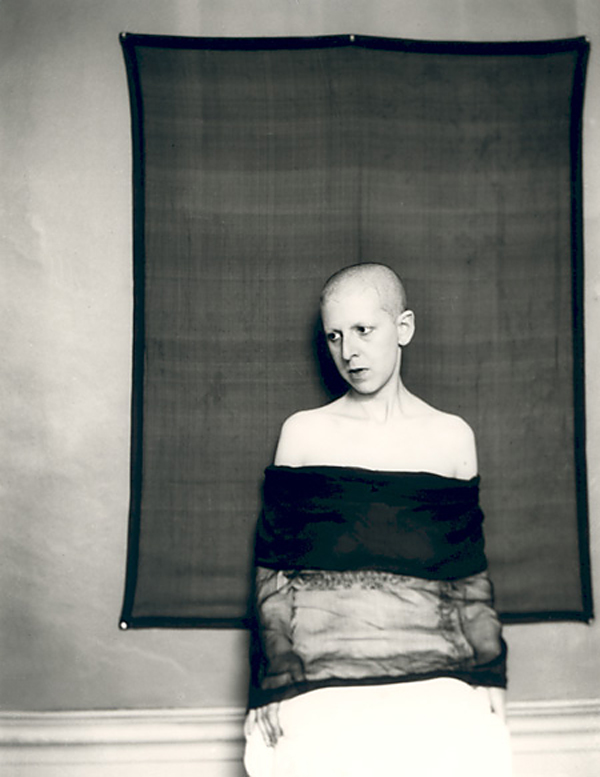

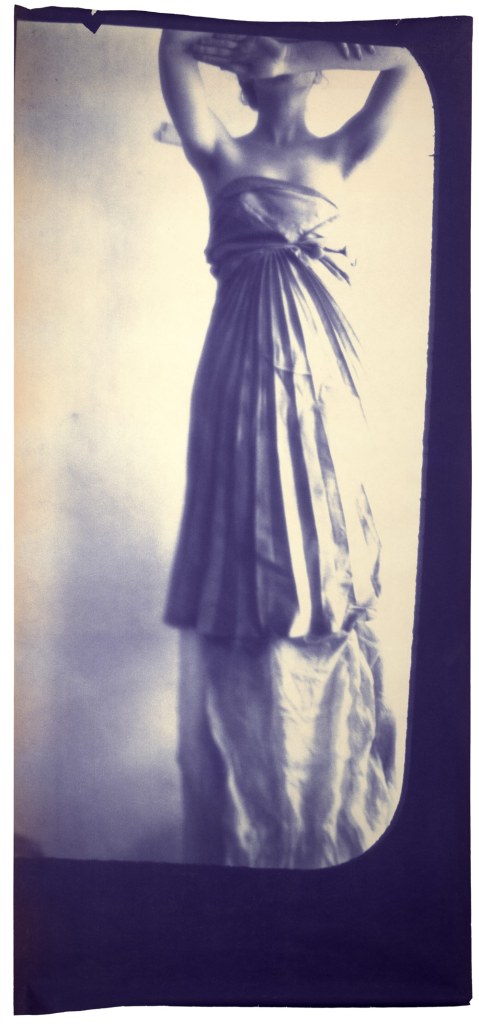

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait (shaved head, material draped across body)

1920

Silver gelatin print

115 x 89mm

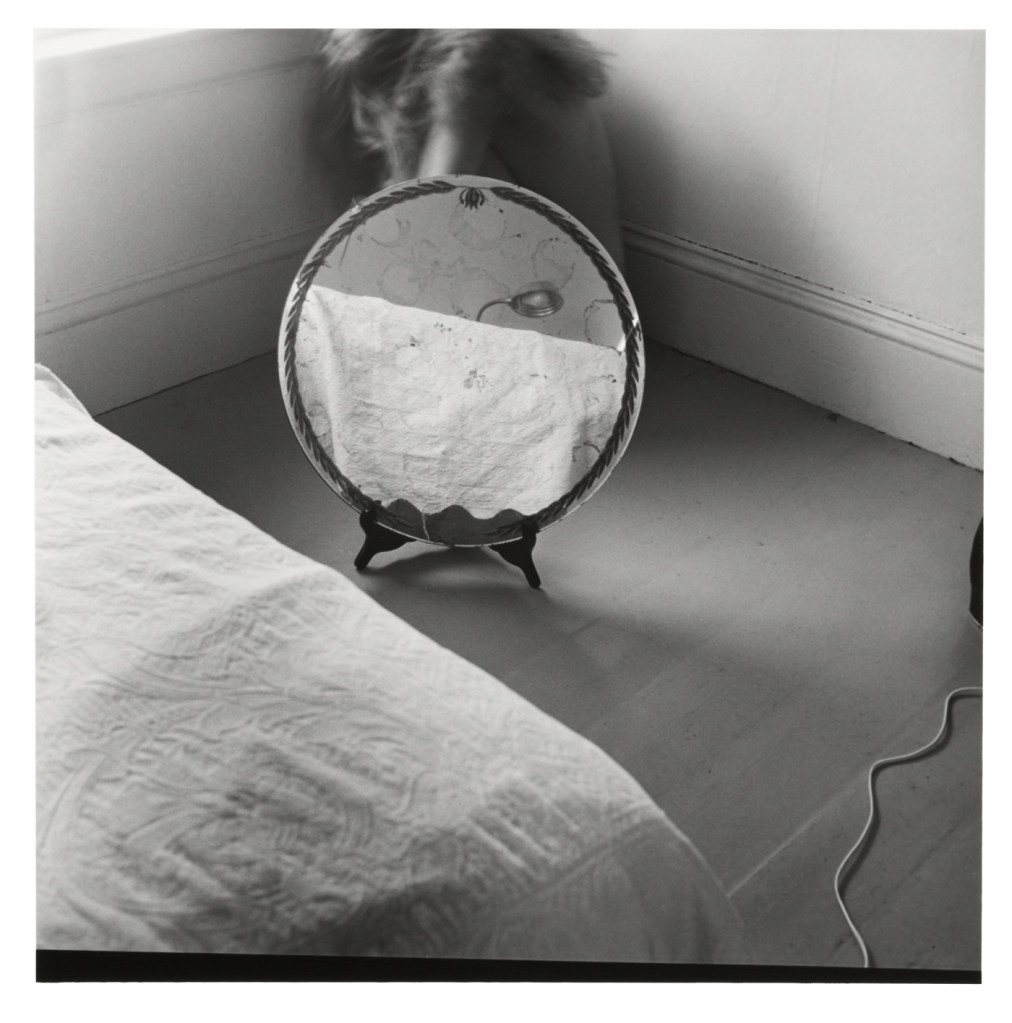

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Autoportrait

1927

Silver gelatin print

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-Portrait

1927

Silver gelatin print

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Que me veux tu? (What do you want from me?)

1929

Gelatin silver print

18 x 23cm (7 1/16 x 9 1/16 ins)

Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait

1929

Gelatin silver print

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Autoportrait

1939

Gelatin silver print

10 x 8cm

Jersey Heritage Collection

© Jersey Heritage

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Self-portrait (with Nazi badge between her teeth)

1945

Photograph – Courtesy of the artist

Ten things you need to know about this extraordinary artist

1. Her real name was Lucy Schwob.

She was born 25 October 1894 in Nantes, daughter of newspaper owner Maurice Schwob and Victorine Marie Courbebaisse; her uncle was the Symbolist writer Marcel Schwob. Subjected to anti-Semitic acts following the Dreyfus Affair, she was removed to a boarding school in Surrey, where she studied for two years.

2. Cahun’s lover was also her stepsister.

In 1909, she met her lifelong partner and collaborator Suzanne Malherbe while studying in Nantes, in what she described as a ‘thunderbolt encounter’. Eight years later, Cahun’s father married Suzanne’s widowed mother.

3. The couple adopted gender-neutral names.

Schwob first used the name Claude Cahun in the semi-biographical text ‘Les Jeux uraniens’, Cahun being a surname from her father’s side. Malherbe changed her name to Marcel Moore and the pair moved to Paris in 1914, where they began their artistic collaborations and Cahun studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne.

4. Cahun was one of the few female Surrealists.

In 1932 she was introduced to André Breton, who called her ‘one of the most curious spirits of our time’. Four years later, Cahun participated in the Surrealist exhibition at the Galerie Charles Ratton, Paris, and visited the International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries, London. Whereas in the works of male Surrealists women often appear as eroticised objects, Cahun’s self-portraits explore female identity as constructed and multifaceted.

5. She was first and foremost a writer.

Now best known for her striking self-portraits, Cahun saw herself primarily as a writer. In 1930 she published Aveux non avenus (translated into English as Disavowals or Cancelled Confessions), an ‘anti-memoir’ including ten photomontages created in collaboration with Moore.

6. In 1937 the couple swapped Paris for Jersey.

Cahun and Moore moved to La Rocquaise, a house in St Brelade’s Bay, Jersey, where they led a secluded life. The couple reverted to their given names, Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe, and were known by the islanders as ‘les mesdames’.

7. They were actively involved in the resistance against Nazi Occupation.

When the Germans invaded Jersey in 1940 they decided to stay and produced counter-propaganda tracts. In July 1944 they were found out, arrested, stood trial, and were, briefly, sentenced to death (though these sentences were commuted). The couple were imprisoned in separate cells for almost a year before Liberation in May 1945.

8. In 1951 Cahun received the Medal of French Gratitude for her acts of resistance during the Second World War. Suffering increasingly from ill health, she died in 1954 at the age of sixty. Moore died eighteen years later, in 1972.

9. She remained forgotten for half a century

Following her move to Jersey, Cahun slipped from critical attention. After the death of Marcel Moore, much of Cahun’s work was put up for auction and acquired by collector John Wakeham, who then sold it to the Jersey Heritage Trust in 1995. The publication in 1992 of the definitive biography by Francois Leperlier, Claude Cahun: l’ecart et la metamorphose, and subsequent exhibition, Claude Cahun: Photographe, at the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1995 encouraged a growing interest in the artist’s work. It was during this time that Gillian Wearing discovered Claude Cahun.

10. She was an artist ahead of her time

Wearing speaks of a ‘camaraderie’ between her and Cahun but she is not the only contemporary artist to have been influenced by her work. Cahun has a dedicated following among artists and art historians working from postmodern, feminist and queer theoretical perspectives; the American art critic Hal Foster described Cahun as ‘a Cindy Sherman avant la lettre’.

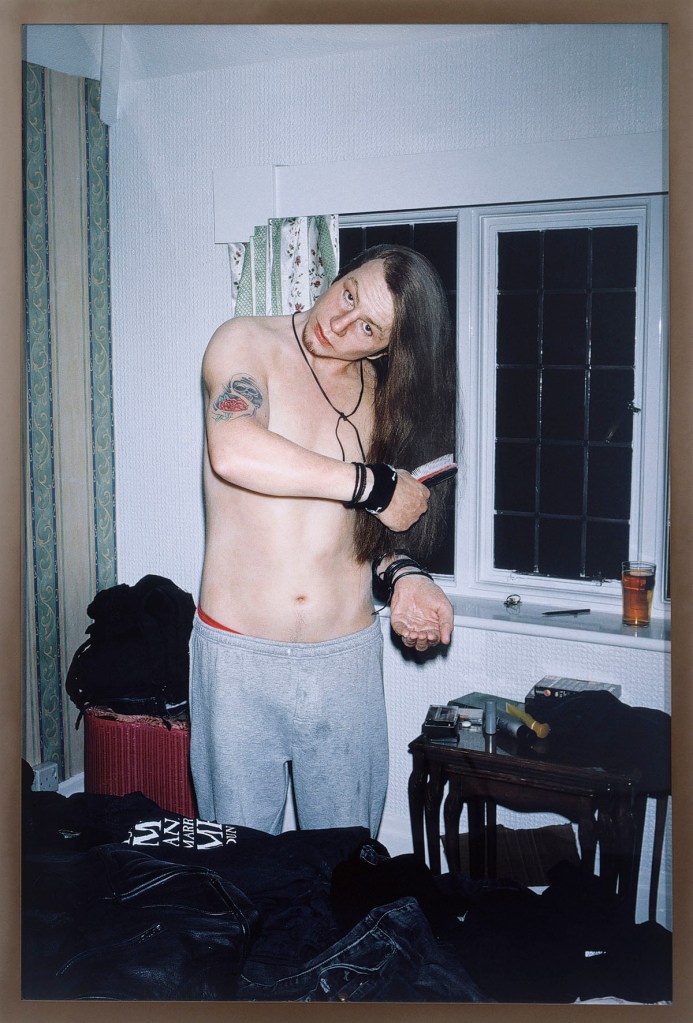

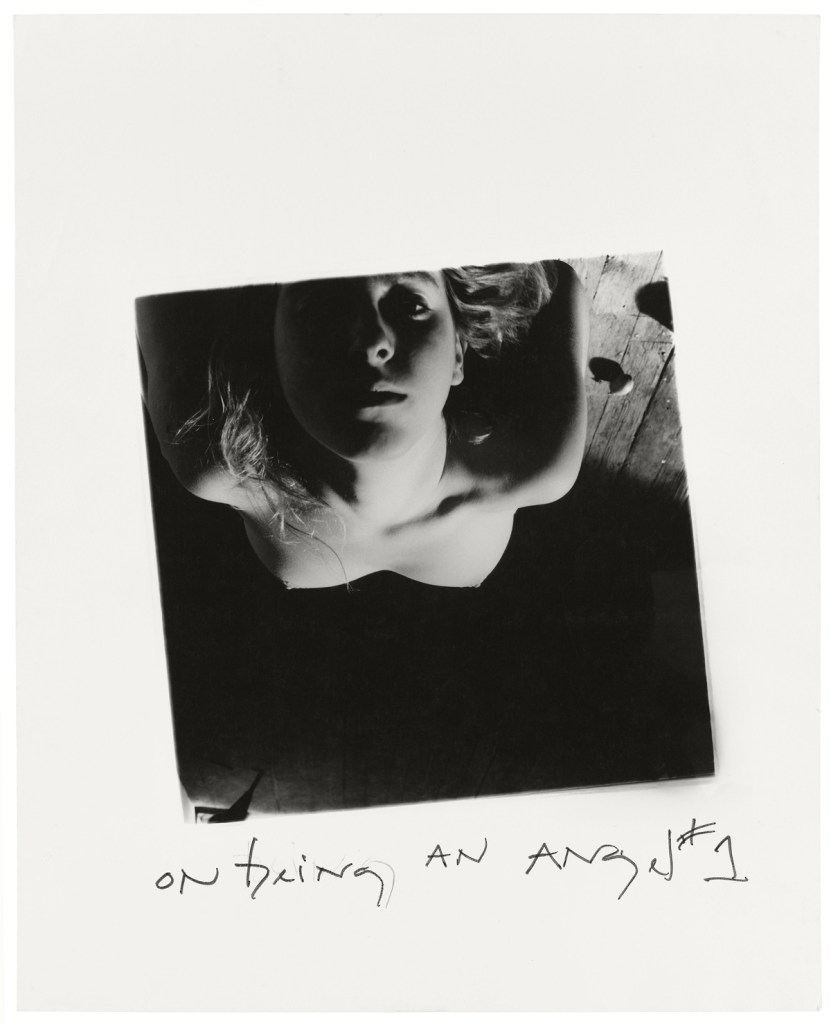

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

Self-portrait as my brother Richard Wearing

2003

Heather Podesta Collection

Courtesy Maureen Paley, London; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

© Gillian Wearing

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

Me as Mapplethorpe

2009

Courtesy Maureen Paley, London, Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

© Gillian Wearing

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

Me as Warhol in Drag with Scar

2010

Courtesy Maureen Paley, London, Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

© Gillian Wearing

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

Me as Diane Arbus

2008-2010

Courtesy Maureen Paley, London, Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

© Gillian Wearing

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

Me as Cahun holding a mask of my face

2012

Courtesy Maureen Paley, London; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

© Gillian Wearing

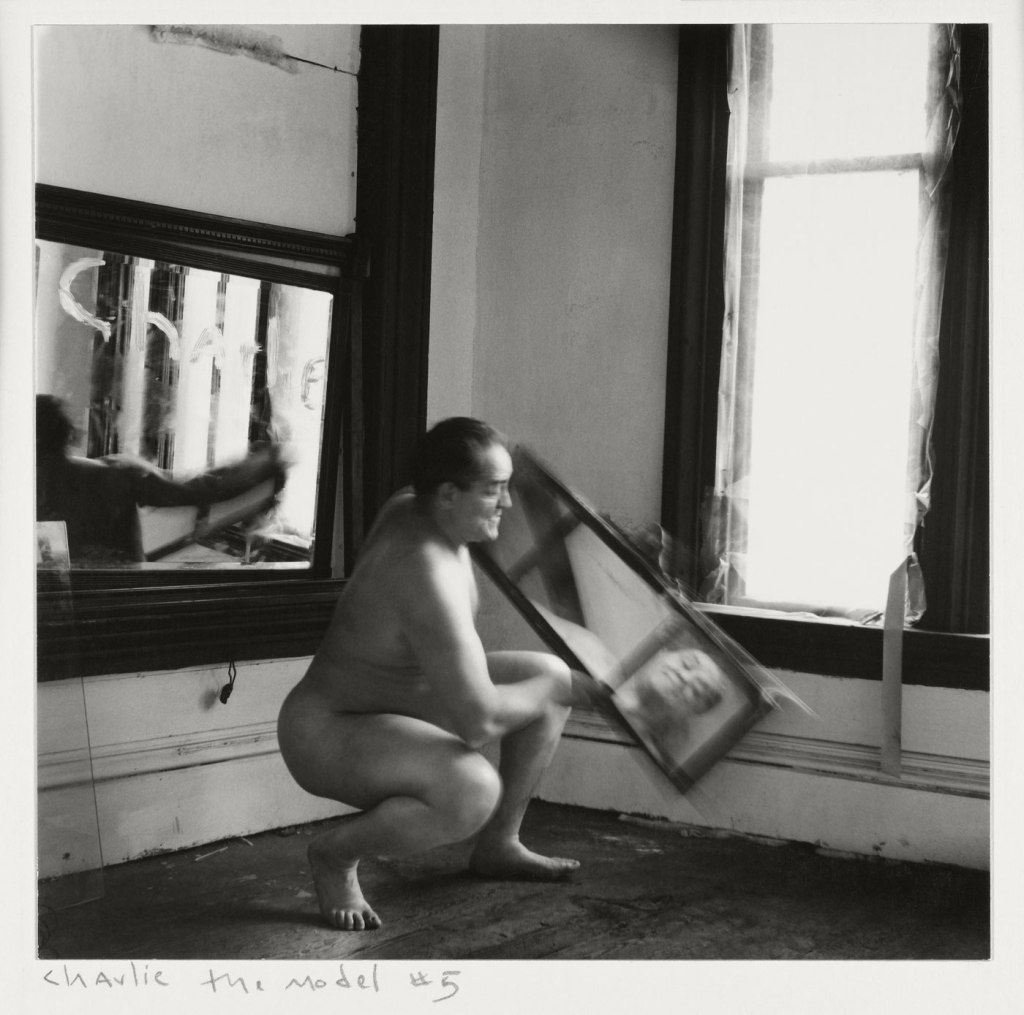

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

Self-portrait of me now in a mask

2011

Collection of Mario Testino

Courtesy Maureen Paley, London; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

© Gillian Wearing

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

Me as mask

2013

Private collection, courtesy Cecilia Dan Fine Art

Courtesy Maureen Paley, London; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

© Gillian Wearing

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

At Claude Cahun’s grave

2015

Courtesy Maureen Paley, London

© Gillian Wearing

National Portrait Gallery

St Martin’s Place

London, WC2H 0HE

Opening hours:

Open daily: 10.30 – 18.00

Friday and Saturday: 10.30 – 21.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.