Exhibition dates: 24th June – 18th September 2016

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Finishing the arabesque

1877

Oil and essence, pastel on canvas

67.4 x 38cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris (RF 4040)

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

This is a magnificent exhibition, well paced and beautifully hung in the gallery spaces. It is gratifying to see a “blockbuster” at the National Gallery of Victoria that does not rely on papered walls or patterned floors, that just allows the work to speak for itself. There is an excellent chronological trajectory to the work, showcasing the holistic development of the artist in one interweaving arc: from the early history paintings, where Degas is educating himself not only in the history of art but also in the practicalities of the history of painting (how actually to paint) … through to the late, bravura pastels.

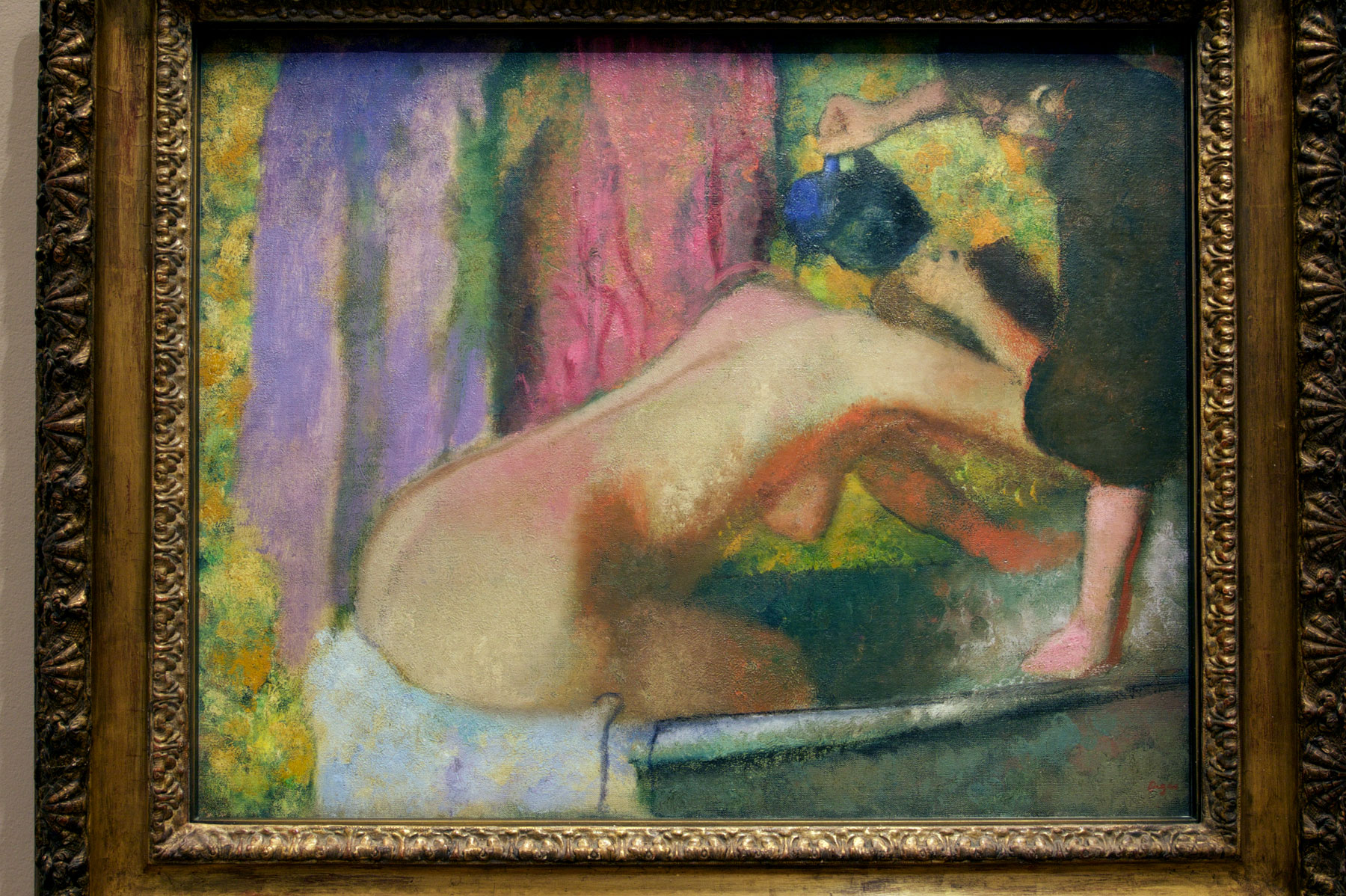

Pastel is Degas’s strongest medium and it was incredible to observe close up how he could make pastel look like oil paint and vice versa. My favourite was Femme à la toilette [Woman at her toilette] (c. 1894, below) were the flattened perspectival image disintegrates before your eyes: “As well as reflecting the artist’s love of Japanese woodblock prints with their frequently intimate subject matter, in this late drawing Degas applied his vivid pigments with an almost sculptural intensity, building them up as though modelling form with his fingers.” Abstraction eat your heart out.

His “impressions” of reality rely on a keen eye, a wonderful understanding of space and the refractions of light, and the use of depth of field. The paintings I like best were not of the ballet, but rather the everyday “observational” paintings of the theatre box, a conversation and, particularly, The laundress ironing (c. 1882-86, below) with its simplified planar colour fields that run in different directions. These “punctures” of reality, or punctum to use a photographic term, elevate mundane everyday occurrences into a revelatory state – as though these encounters were taken from the flow of space and time, one frame out of a non-linear narrative.

The paintings of women at the toilettes are not voyeuristic but show a love and passion for an intimacy with women which he perhaps never achieved in real life, brought forth in observations of the female form “that challenged conventional notions of feminine beauty in their depiction of non-idealised jolie-laide (unconventionally beautiful) models”. Melbourne arts blogger Natalie Thomas observes that, “”Women and girls are everywhere in this show, but strangely absent too,” writes Thomas. Despite the fact the majority of Degas’ work explores femininity and the female body, the show, she says, fails to provide a female perspective.” (Natalie Thomas quoted in Shad D’Souza, “Gender and the NGV: ‘More white male artists than you can shake a stick at’,” on The Guardian website 15 September 2016 Cited 16/09/2016).

While I agree with Natalie Thomas that these paintings fail to provide a contemporary female perspective, that is not all that these paintings are about. Of course, they are a privileged white male gaze looking upon the body of a female and we must accept and acknowledge that is what they are. But that is just one element of their narrative. It’s all very well critiquing the work from the present day and saying there is no female perspective, but in the era in which these “sensational” paintings emerged – it was an epoch where the privileged, powerful male gaze could look upon the female body. Yes, please look at the paintings from a contemporary perspective while understanding the conditions under which they were created, and then try to say something more interesting about them: the perspective, the colours, the form, the position of the painter, the framing of the scene, the possible disappearance of the artist to the sitter, as though the camera (his eyes) had disappeared: where someone is so used to the other being there, that they are natural (do not act or perform), unselfconscious in front of them. Then, and only then, do the paintings perhaps become something else – about women, their lives and habits / habitats. A different perspective from trotting out the usual “we are objectified / subjugated / defiled” trope.

The sculptures are the revelation of the exhibition. Again, the male gaze pushing and prodding at the female form… except, these sculptures seem to erupt from within – like bubbling hot mud that seems to emanate from deep within the artist, erupting into the glorious form of the female body. Dark and mysterious, I would have loved to have seen one of the wax models, just one, to see the colour and feel the fragility of that form, over the robustness of the bronze.

And finally to the last room, the late works. There is an essentialness to the late work, the form stripped bare, heavily applied pastel in layers, dark heavy outlines with the frame filled with an “orgy of colours” – he “developed an expressive use of colour and line that may have arisen due to his deteriorating vision.” But he could still feel what he was doing and we can feel it too: the working of the medium, the working of the theme to its final resolution.

While I didn’t know much about the work of Degas other than the ballet pictures before this exhibition – after three visits, perhaps I know just a little more.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Victoria for allowing me to publish the artwork and photographs in the posting. All installation photographs © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

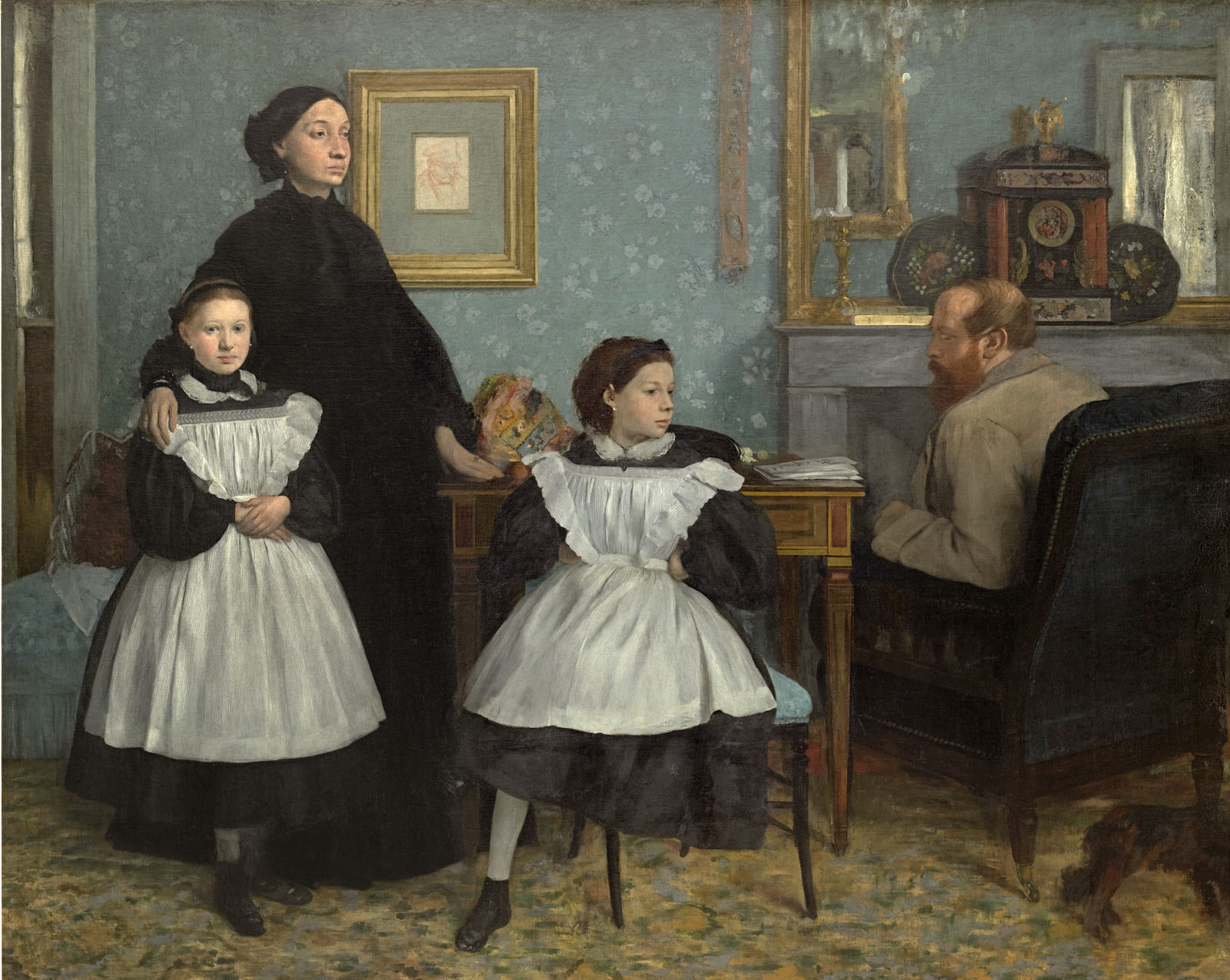

Edgar Degas biography

Edgar Degas was born in 1834 into a wealthy banking family. Unlike many of his contemporaries, his family were supportive of his artistic talent and desire to become an artist.

Degas resisted being labelled an ‘Impressionist’ yet was at the core of the movement’s most important manifestations. Classically trained, Degas initially aspired to be a painter of historical narratives. As he matured, however, he made the depiction of daily life the central focus of his art. He was drawn primarily to the human figure engaged in movement and work, sketching on the spot then working up his finished compositions indoors in his studio. Degas’ obsession with the theatre and ballet in particular enabled him to explore his fascination with artificial light, which set him apart from the other Impressionists who preferred to work out-of-doors capturing the transient effects of natural daylight.

Degas absorbed many diverse influences, from Japanese prints to Italian Mannerism, and reinterpreted them in innovative ways. Degas obsessively revisited and experimented with his favourite themes which saw him fashion varied and unusual vantage points and asymmetrical framing. His depictions of ballet dancers alone number in the hundreds. Such endeavours helped him to achieve the innovative and distinctive style which is explored in Degas: A New Vision.

Degas served in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and began to experience eyesight deterioration by the late 1880s. He increasingly took up sculpture as his eyesight weakened. In his later years, he was preoccupied with the subject of women bathing unselfconsciously and developed an expressive use of colour and line that may have arisen due to his deteriorating vision.

Degas continued working to as late as 1912. He died five years later in 1917, at the age of eighty-three.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Danseuses, éventail [Dancers (Fan, design)] (installation view)

1879

Gouache, pastel and oil paint on silk

Tacoma Art Museum, Washington State

Gift of Mr and Mrs W. Hilding Lindberg

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

[Dancers (Fan, design)] belongs to a group of fans made in the late 1870s that reflect Degas’s fascination at this time with Japanese art. Highly aestheticised, these fans show how Degas took advantage of this unusual format to explore new compositional possibilities. Here, for example, the balletic action taking place on stage competes for the viewer’s attention with the theatre’s screening machinery, as well as with the group of black-clad abonnés (subscribers with back stage passes) gathered in the wings in the middle distance.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Degas: A New Vision at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne with at left, Theatre box (1885) and at right, Theatre box (1880)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

La Loge [Theatre box] (installation view)

1885

Pastel

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

The Armand Hammer Collection

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

In contrast with his numerous ballet works, Degas produced relatively few studies of the spectators at the Opera and other theatrical venues. Theatre box is one of his most captivating studies of the magical effects created by artificial stage lighting. Its contrast between the shadowy reality of the viewer in her dimmer theatre box and the vividly illuminated fantasy being performed before her onstage is as compelling as it is radical.

Wall text from the exhibition

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

La Loge [Theatre box] (installation view)

1880

Pastel and oil on cardboard on canvas

The Lewis Collection, Houston

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

When exhibited at the fifth ‘impressionist’ group exhibition in Paris in 1880, this pastel attracted the attention of the critic Charles Ephrussi, who wrote glowingly of how it shoed ‘a profound knowledge of the relations between tones, producing the most unexpected and curious effects: the wine-coloured draperies of the spectator’s box and the yellowish glow of the footlights are projected onto the face of a diminutive theatre-goer, who thus finds herself illuminated by violet and brilliant yellow; the impression is strange, but captured with perfect reality’.

Wall text from the exhibition

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Theatre box

1880

Pastel and oil on cardboard on canvas

66.0 x 53.0cm

The Lewis Collection

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

In a café (The Absinthe drinker)

c. 1875-1876

Oil on canvas

92 x 68.5cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris (RF 1984)

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Martine Beck-Coppola

Cafés-concerts: 1870s

The time that Degas spent overseas in New Orleans made him surprisingly nostalgic for everything he had left behind in Paris. The simple reason he gave was that ‘One loves and gives art only to the things to which one is accustomed’. Although delighted by the new sights and sensations he experienced in New Orleans, he felt that ‘ new things capture your face and bore you by turns’. With these words, Degas expressed what would become his credo for the rest of his career.

After this time, Degas refused invitations to travel to exotic locales and put aside the search for new subjects, focusing instead on the same themes: dancers, rockets, women in the bath. The novelty of what he had discovered in America also led him soon afterwards to retreat into himself. seeing inspiration in introspection. For Degas the exotic could be found perfectly well at home, especially in the new evening venues of 1870s Paris, the café-concerts. He delighted in exploring the tension and psychological preparation that lay behind the surface glamour of stage performances conducted within an artificial other-reality.

Wall text from the exhibition

All that gesture in theatre summon,

or that the agile and mendacious tongue

of ballet speaks to those who comprehend

the silent eloquence of limbs in motion.

Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Rehearsal hall at the Opéra, rue Le Peletier

1872

Oil on canvas

32.7 x 46.3cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The dance rehearsal

c. 1870-1872

Oil on canvas

40.6 x 54.6cm

The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.

Gift of anonymous donor, initiated 2001, completed 2006

Installation view of the exhibition Degas: A New Vision at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at left, The rehearsal (c. 1874), and at right The dance class (c. 1873)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The rehearsal (installation view)

c. 1874

Oil on canvas

58.4 x 83.8cm

Lent by Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums) on behalf of Glasgow City Council: from the Burrell Collection with the approval of the Burrell Trustees

© CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The rehearsal

c. 1874

Oil on canvas

58.4 x 83.8 cm

Lent by Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums) on behalf of Glasgow City Council: from the Burrell Collection with the approval of the Burrell Trustees

© CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

First Ballet Works: 1870s

While the friendships he established in the 1860s with musicians such as Désiré Dihau, a bassoon player with the Paris Opéra, brought Degas into the orbit of ballet performances in the French capital, the full extent of his access to this world prior to the mid-1880s remains unknown. This may explain why his many depictions of dancers practising backstage in rehearsal rooms in the 1870s were his own studio inventions rather than accurate depictions of the Opéra’s foyers de la danse.

Degas’ favourite theatrical venues – the Opéra in the rue le Peletier that was destroyed by fire in October 1873 and its replacement, the Palais Garnier, which opened in 1875 – were both located in the 9th arrondissement, close to his studio. Degas exhibited ballet compositions at the ‘impressionist’ group exhibitions from 1874 onwards, all the while resisting the label, arguing that his own art was Realist and meticulously crafted in the studio instead of spontaneously created before nature. When the Galeries Durand-Ruel began acquiring Degas’ paintings in 1872, the artist’s first sales at this time were of ballet subjects. Unlike the romantic perspective through which these scenes are viewed today, Degas’ contemporaries recognised in them a rejection of the surface glamour of ballet’s front of house in favour of a serious study of the gritty reality of life backstage. There, junior impoverished dancers jostled for attention from their trainers, all too frequently prostituting themselves on the side so they could afford to stay in competition for coveted stardom.

While The rehearsal and other similar depictions such as The dance class, c. 1873, are ostensibly based on direct observations of dance rehearsals at the Paris Opéra in the rue Le Peletier, their different treatments of architecture hint at the degree to which Degas constructed their compositions from memory. This painting shows a radical cropping of the spiral staircase at left connecting the stage level to the rehearsal room, down which the disembodied limbs of young ballerinas descend. In the background to the right the celebrated dance instructor Jules Perrot can be seen.

Wall text from the exhibition

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The dance class

c. 1873

Oil on canvas

47.6 x 62.2cm

National Gallery, Washington D.C.

Corcoran Collection (William A. Clark Collection)

© Courtesy of National Gallery, Washington

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The dance class (installation view)

c. 1873

Oil on canvas

47.6 x 62.2cm

National Gallery, Washington D.C.

Corcoran Collection (William A. Clark Collection)

© Courtesy of National Gallery, Washington

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Dancers on the stage (installation views)

c. 1899

Oil on canvas

76.0 x 82.0cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

Legs Jacqueline Delubac, 1997

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Dancers on the stage

c. 1899

Oil on canvas

76.0 x 82.0cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

Legs Jacqueline Delubac, 1997

Image © Lyon MBA – Photo RMN / Ojeda, Le Mage

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Dancers on the stage (detail)

c. 1899

Oil on canvas

76.0 x 82.0cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

Legs Jacqueline Delubac, 1997

Dancers on the stage looks back to the experiments with pictorial space and repoussoir compositional staging that had so characterised Degas’s ballet works of the 1870s and early 1880s. Repoussoir was a favourite technique for Degas, a technique in which an object place prominently in the foreground of a work serves to emphasise the recession of physical space in the rest of the composition. In an unusual choice for the artist, Degas shows here a dress rehearsal on stage. The attention of the dancers is focused upon the diminutive figure of the dave master in the far left background whose presence ignites a diagonal magnetism that animates the whole painting.

Wall text from the exhibition

Dr Ted Gott, Senior Curator of International Art at the National Gallery of Victoria talking to the media, standing in front of Degas’s Dancer with bouquets c. 1895-1900

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Dancer with bouquets (installation view and detail)

c. 1895-1900

Oil on canvas

180.3 x 152.4 cm

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia

Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr, in memory of Della Viola Forker Chrysler

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Dancer with bouquets

c. 1895-1900

Oil on canvas

180.3 x 152.4cm

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia

Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr, in memory of Della Viola Forker Chrysler

Sculptures

Although Degas exhibited only one sculpture during his lifetime, The little fourteen-year old dancer, he worked in this medium in privacy in his studio from the 1860s until the 1910s. His primary subjects were thoroughbred racehorses, female dances and women at the toilette, and he modelled his sculptures in wax, over steel wire and cork armatures. Never satisfied, he made, destroyed and remade them repeatedly. As Degas’s eyesight deteriorated in his later years, making three-dimensional figures fulfilled a physical and emotional need that transcended any desire to perfect a finished object; he allegedly side that sculpture was ‘a blind man’s trade’.

After Degas’s death in 1917, some 150 wax sculptures were found in his studio, some broken but many intact. His heirs subsequently authorised the casting in bronze of seventy-four of the most intact of Degas’s sculptures. While many of Degas’s original wax sculptures still survive, they are too fragile to travel. These bronzes allow wider audiences today to engage with some of the most beautiful sculptures of the nineteenth century.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation views of the exhibition Degas: A New Vision at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing the sculpture cases

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The tub

1888-89, cast 1919-32

Bronze

22.5 x 45.0 x 42.0cm

Czestochowski/Pingeot 26 (cast S)

Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Assis Chateaubriand

Donated by Alberto José Alves, Alberto Alves Filho and Alcino Ribeiro de Lima

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The masseuse

c. 1896-1911, cast 1919-32

Bronze

43 x 38 x 30cm

Czestochowski/Pingeot 55 (cast S)

Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Assis Chateaubriand

Donated by Alberto José Alves, Alberto Alves Filho and Alcino Ribeiro de Lima

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Seated woman wiping her left side

c. 1901-11, cast 1919-32

Bronze

35 x 30.5 x 30.4cm

Czestochowski/Pingeot 46 (cast S)

Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Assis Chateaubriand

Donated by Alberto José Alves, Alberto Alves Filho and Alcino Ribeiro de Lima

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Dancer adjusting the shoulder strap of her bodice

1882-95, cast 1919-32

Bronze

35.2 x 15.9 x 11.8cm

Czestochowski/Pingeot 64 (cast S)

Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Assis Chateaubriand

Donated by Alberto José Alves, Alberto Alves Filho and Alcino Ribeiro de Lima

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Dancer looking at the sole of her right foot (Second study)

c. 1900-1910, cast 1919-1937 or later

Bronze

47.3 x 24.3 x 20.8cm

Czestochowski/Pingeot 59 (cast T)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Leigh Clifford AO and Sue Clifford, 2016

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The laundress ironing (installation view)

c. 1882-1886

Oil on canvas

64.8 x 66.7cm

Reading Public Museum, Pennsylvania Gift, Miss Martha Elizabeth Dick Estate

© Courtesy of the Reading Public Museum, Pennsylvania

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The laundress ironing

c. 1882-1886

Oil on canvas

64.8 x 66.7cm

Reading Public Museum, Pennsylvania Gift, Miss Martha Elizabeth Dick Estate

© Courtesy of the Reading Public Museum, Pennsylvania

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The Conversation (installation view)

1895

Pastel

65 x 50cm (sheet)

Acquavella Galleries

© Courtesy of Acquavella Galleries

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The Conversation

1895

Pastel

65 x 50cm (sheet)

Acquavella Galleries

© Courtesy of Acquavella Galleries

Walter Sickert recalled Degas speaking of his obsession with observing women at their most private moments. He wanted to look at their private activities through keyholes, according to Sickert: ‘He said that painters too much made of women formal portraits, whereas their hundred and one gestures, their chatteries, &c., should inspire an infinite variety of design’. The Conversation reflects the artist’s love of Japanese woodblock prints and their frequently intimate subject matter. The specifics of setting are only alluded to in this exquisite pastel, the emphasis being placed instead upon the close relationship between these two elegant Parisiennes.

Wall text from the exhibition

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Rose Caron (installation view)

c. 1892

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Women at their toilettes: 1880s and 1890s

In 1875 pastel became one of Degas’s favourite techniques. Gustave Moreau had introduced him to this medium during their time together in Italy during the late 1850s, and the increasing interest in pastel in artistic circles during the 1870s influenced Degas’s choice to explore its potential. At the eighth and last ‘impressionist’ group exhibition in 1886 Degas exhibited a suite of pastel studies of women bathing that challenged conventional notions of feminine beauty in their depiction of non-idealised jolie-laide (unconventionally beautiful) models. George Moore wrote tellingly of these nudes: ‘The effect is prodigious. Degas has done what Baudelaire did – he has invented un frisson nouveau (a new sensation)’.

Because intimate access to female ablutions was rarely experience by husbands in bourgeois married life at the time, it was assumed by critics and audiences that Degas’s female nudes were performing their toilettes in a brothel setting. The close observation of undressed women engaged in private acts of washing and drying themselves led Degas’s ongoing status as a bachelor to become a topic of speculation in both the art world and wider social circles.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation views of the exhibition Degas: A New Vision at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne with, from left to right, Nude woman lying down (c. 1901), Dancer in a leotard (c. 1896) and Toilette after the bath (c. 1890)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Installation views of the exhibition Degas: A New Vision at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at centre left in the bottom image, The Bather (La Baigneuse), c. 1895

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

The Bather (La Baigneuse) (installation view)

c. 1895

Pastel and charcoal on paper

Bequest, Henry K. Dick Estate

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Femme à la toilette [Woman at he toilette] (installation view)

c. 1895-1900

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Femme à la toilette [Woman at her toilette] (installation view)

c. 1894

Charcoal and pastel on paper

956 x 1099mm

Tate, London

Presented by C. Frank Stoop 1933

© Tate, London 2016

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Femme à la toilette [Woman at her toilette]

c. 1894

Charcoal and pastel on paper

956 x 1099mm

Tate, London

Presented by C. Frank Stoop 1933

© Tate, London 2016

The repetitive work involved in a woman’s daily maintenance of her hair appealed greatly to Degas. As early as 187 he asked whether he could observe Geneviève Halévy, a cousin of his old school friend Ludovic, performing this private tasks. Woman at her toilette is a fascinating study of a woman’s labour-intensive morning routine, drawn with a sense of pathos and human frailty. As well as reflecting the artist’s love of Japanese woodblock prints with their frequently intimate subject matter, in this late drawing Degas applied his vivid pigments with an almost sculptural intensity, building them up as though modelling form with his fingers.

Wall text from the exhibition

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Woman in a Tub

c. 1883

Pastel on paper

70 x 70cm

Tate, London

Bequeathed by Mrs A.F. Kessler 1983

© Tate, London 2016

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Woman at her bath

c. 1895

Oil on canvas

71.1 x 88.9cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Purchase, Frank P. Wood Endowment, 1956

© 2016 Art Gallery of Ontario

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Woman at her bath (installation view)

c. 1895

Oil on canvas

71.1 x 88.9cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Purchase, Frank P. Wood Endowment, 1956

© 2016 Art Gallery of Ontario

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Woman seated on the edge of the bath sponging her neck (installation view)

1880-1895

Oil and essence on paper mounted to canvas

52.2 x 67.5 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Woman seated on the edge of the bath sponging her neck

1880-1895

Oil and essence on paper mounted to canvas

52.2 x 67.5cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Installation view of the exhibition Degas: A New Vision at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at right, Femme au Tub [Nude woman drying herself] c. 1884-1886

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Femme au Tub [Nude woman drying herself] (installation view)

c. 1884-1886

Oil on canvas

Brooklyn Museum, New York

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Horse racing

Broken staccato heralds its approach,

strong, steaming breath, as early as the dawn,

kept to its straining pace by stable lad,

the fine colt gallops throwing up the dew.

Edgar Degas

Racecourses: 1860s

Horse racing was Degas’s first recurrent modern subject, and preceded his dance classes and opera scenes. In 1861 Degas visited Ménil-Hubert in the Normandy countryside, the family estate of his old school friend Paul Valpinçon, situated near to the Haras-le-Pin stud and the Argentan racecourse. The recreational sports of horse racing and the steeplechase now offered him scope for exploring contemporary narrative painting. In pre-mechanised Europe, horses were as ubiquitous as the car is today. They were an essential part of life, whether for work or pleasure, and Degas was accordingly fascinated by these magnificent creatures. They feature in his earliest sketchbooks when he carefully copied equestrian subjects after the Parthenon frieze sculptures and the Italian Old Masters Paolo Uccello and Benozzo Gozzoli; and he continuously drew, painted and sculpted horses until his death.

Degas’s approach to depicting horses embodies his lifelong methodology. He studied and copied how they were represented by specialist animalier artists, as well as by the Old Masters, and he spent many hours observing and examining them. How he portrayed horses changed over time and his earliest works reveal a slightly tentative and clichéd manner as he struggled for perfection. As his art evolved, his images of horses became more innovative and remarkable: he attained great precision in their appearance yet the rendering remained tactile and lively. He also perfectly captured the physical relationship between rider and horse through all the different poses they struck, whether at rest or in full flight. Few artists have reproduced the grace, power and elegance of horses as well as Degas.

Wall text from the exhibition

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Out of the paddock (Racehorses)

c. 1871-1872, reworked c. 1874-1878

Oil on wood panel

32.5 x 40.5cm

Private collection

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Chevaux de courses [Racehorses] (installation view)

c. 1895-1899

Pastel on tracing paper on cardboard

55.8 x 64.8cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Purchase 1950

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Racehorses

c. 1895-1899

Pastel on tracing paper on cardboard

55.8 x 64.8cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Purchased 1950

Photo © NGC

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Before the race

c. 1883-1990

Pastel

49 x 62cm (sheet)

Private collection

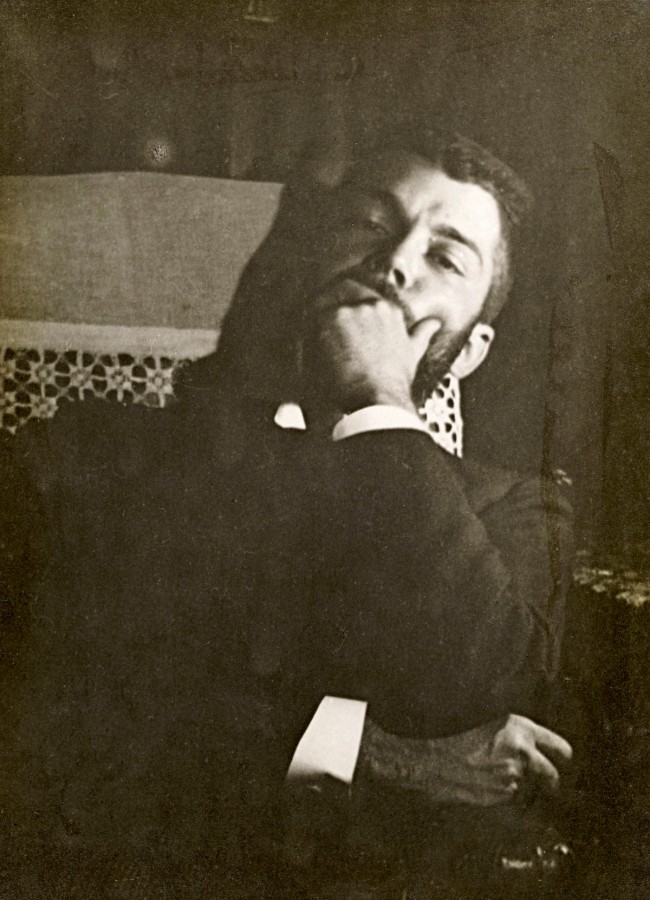

Photography

By the time he began making photographs in 1895, Degas was 61 years old and the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition was a decade behind him. Daniel Halévy, son of his old friends Ludovic and Louise Halévy, introduced Degas to photography, prompting the artist to acquire a camera that required glass plates and a tripod. In a burst of creative energy that lasted less than five years, he made a body of photographs of which fewer than 50 survive…

Exactly why Degas took up photography remains unknown. Clearly, photography provided a new pair of eyes during the period when his eyesight was failing. The illness and death of his sister, Marguerite, in 1895 and his brother Achille in 1893 may also have played a role. Photographs were for Degas a powerful tool of memory to recall his loved ones, and the activity of photographing bound him closely to an extended family-the Halévys-that embraced him in his time of grief…

Degas often illuminated his subjects with a single bright light source. The figures seem to emerge from darkness. In a series of individual portraits he made of Daniel and Louise Halévy in the autumn of 1895, each sitter is pictured in the same armchair in their home, under this Rembrandtesque light. They are seen in original contact prints (about 3 x 4 inches) and in enlargements. Altogether, these images show the artist’s picture-making process and reveal Degas’ manipulations of space, scale, focus, and emotional effect. In Louise Halévy Reading to Degas (J. Paul Getty Museum), another enlargement from a contact print done about the same time, Degas conveys unusual intimacy. It shows a vulnerable man’s dependence upon a friend in reading the newspaper at a time when his eyesight was failing.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

“These days, Degas abandons himself entirely to his new passion for photography,” wrote an artist friend in autumn 1895, the moment of the great Impressionist painter’s most intense exploration of photography. Degas’s major surviving photographs little known even among devotees of the artist’s paintings and pastels, are insightfully analysed and richly reproduced for the first time in this volume, which accompanies an exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The J. Paul Getty Museum, and the Bibliothéque Nationale de France.

Degas’s photographic figure studies, portraits of friends and family, and self-portraits – especially those in which lamp-lit figures emerge from darkness – are imbued with a Symbolist spirit evocative of realms more psychological than physical. Most were made in the evenings, when Degas transformed dinner parties into photographic soirees, requisitioning the living rooms of his friends, arranging oil lamps, and directing the poses of dinner guests enlisted as models. “He went back and forth … running from one end of the room to the other with an expression of infinite happiness,” wrote Daniel Halévy, the son of Degas’s close friends Ludovic and Louise Halévy, describing one such evening. “At half-past eleven everybody left; Degas, surrounded by three laughing girls, carried his camera as proudly as a child carrying a rifle.”

Text from The Met website

Installation view of the exhibition Degas: A New Vision at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne with at right, Paul Gobillard, Jeannie Gobillard, Julie Manet, and Geneviève Mallarmé (16 December 1895, below)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Paul Gobillard, Jeannie Gobillard, Julie Manet, and Geneviève Mallarmé (installation view)

16 December 1895

Gelatin silver print

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Self-portrait with Zoé Closier

Probably Autumn 1895

Gelatin silver print

18.2 x 24.2cm (image and sheet)

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Self-portrait with Zoé Closier (installation view)

Probably Autumn 1895

Gelatin silver print

18.2 x 24.2cm (image and sheet)

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Self-portrait with Bartholomé’s Weeping girl (installation view)

Probably Autumn 1895

Gelatin silver print

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Daniel Halévy

14 October 1895

Gelatin silver print

40.0 x 29.4cm (image and sheet)

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Gift of the children of Mme Halévy-Joxe

Photo © RMN – Hervé Lewandowski

Late works

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Les Trois Danseuses [Three dancers]

1896-1905

Pastel

51 x 47cm

Lent by Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums) on behalf of Glasgow City Council: from the Burrell Collection with the approval of the Burrell Trustees (35.249)

© CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Pastel entitled Les Trois Danseuses, depicting three ballet dancers, apparently making an entry, wearing yellow ballet skirts.

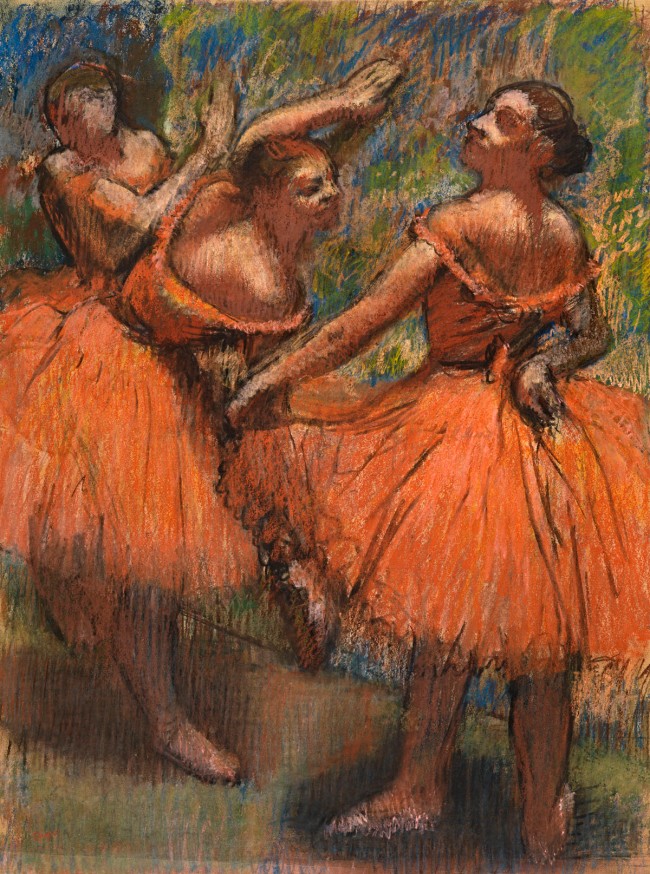

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Group of dancers (red skirts) [Les Jupes Rouges] (installation view)

1895-1900

Pastel

77 x 58cm

Lent by Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums) on behalf of Glasgow City Council: from the Burrell Collection with the approval of the Burrell Trustees

© CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Group of dancers (red skirts) [Les Jupes Rouges]

1895-1900

Pastel

77 x 58cm

Lent by Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums) on behalf of Glasgow City Council: from the Burrell Collection with the approval of the Burrell Trustees

© CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Pastel entitled Les Jupes Rouges, depicting three ballet dancers in red skirts – in posing practice.

Throughout his career Degas produced more than 700 works in pastel. In the 1870s he often worked ‘wet’, employing pastel à l’eau (crushing pastel sticks to powder which, mixed with water, could be applied with a brush) to create smooth, seamless textures. By the mid 1890s he worked increasingly with layers of pastel cement together over applications of fixative. This created shimmering optical effects that celebrated the crumbly texture of the pastel medium.

Wall text from the exhibition

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Dancers at the barre

1900

Charcoal and pastel on tracing paper on cardboard

111.2 x 95.6cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Purchased 1921

Photo © NGC

Installation views of the exhibition Degas: A New Vision at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne with at right in the bottom image, Dancers at the barre (1900)

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Installation views of the exhibition Degas: A New Vision at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne with at right, The Russian dancer (1895)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Dancers at a rehearsal (installation view)

c. 1895-1898

Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria

NGV International

180 St Kilda Rd, Melbourne

Opening hours:

Open daily, 10am – 5pm

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Danseuses, éventail [Dancers (Fan, design)]' (installation view) 1879 Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Danseuses, éventail [Dancers (Fan, design)]' (installation view) 1879](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-al.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917 'La Loge [Theatre box]' 1885 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917 'La Loge [Theatre box]' 1885 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/installation-am.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'La Loge [Theatre box]' 1880 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'La Loge [Theatre box]' 1880 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/installation-an.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'La Baigneuse [The bather]' c. 1895 Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'La Baigneuse [The bather]' c. 1895](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/installation-bp.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Femme a la toilette [Woman at he toilette] c. 1895-1900 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Femme a la toilette [Woman at he toilette] c. 1895-1900 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/installation-bd.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Femme a la toilette [Woman at her toilette] c. 1894 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Femme a la toilette [Woman at her toilette] c. 1894 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/installation-be.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Femme a la toilette [Woman at her toilette] c. 1894 Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Femme a la toilette [Woman at her toilette] c. 1894](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/exhi036044-web.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at right, 'Femme au Tub' [Nude woman drying herself] c. 1884-1886 Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at right, 'Femme au Tub' [Nude woman drying herself] c. 1884-1886](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/installation-bh.jpg)

![Edgar Degas. 'Femme au Tub [Nude woman drying herself]' c. 1884-1886 (installation view) Edgar Degas. 'Femme au Tub [Nude woman drying herself]' c. 1884-1886 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/installation-bi.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Chevaux de courses [Racehorses]' c. 1895-1899 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Chevaux de courses [Racehorses]' c. 1895-1899 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/installation-bf.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Chevaux de courses [Racehorses]' c. 1895-1899 Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Chevaux de courses [Racehorses]' c. 1895-1899](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/exhi039831_web.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at left, 'Mendiante romaine' [Roman beggar women] (1857) Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at left, 'Mendiante romaine' [Roman beggar women] (1857)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-l.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Mendiante romaine' [Roman beggar women] 1857 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Mendiante romaine' [Roman beggar women] 1857 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-m.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at left, 'Monsieur Reulle' (1861); and at right, 'Portrait de jeune femme' [Portrait of a young woman] (1867) Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at left, 'Monsieur Reulle' (1861); and at right, 'Portrait de jeune femme' [Portrait of a young woman] (1867)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-q.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Étude pour Jeunes Spartiates s'exerçant à la lutte' [Study for The young Spartans exercising] c. 1860-1861 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Étude pour Jeunes Spartiates s'exerçant à la lutte' [Study for The young Spartans exercising] c. 1860-1861 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-o.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Petites filles spartiates provoquant des garçons' [Young Spartan girls challenging boys] c. 1860 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Petites filles spartiates provoquant des garçons' [Young Spartan girls challenging boys] c. 1860 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-n.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Petites filles spartiates provoquant des garçons' [Young Spartan girls challenging boys] c. 1860 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Petites filles spartiates provoquant des garçons' [Young Spartan girls challenging boys] c. 1860 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-p.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Etude de nus: Mlle Fiocre dans le ballet La Source' [Nude study: Mademoiselle Fiocre in the ballet 'The Spring'] 1867-1868 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Etude de nus: Mlle Fiocre dans le ballet La Source' [Nude study: Mademoiselle Fiocre in the ballet 'The Spring'] 1867-1868 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-aa.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at left, 'Portrait d'homme' [Portrait of a man] (c. 1866) and at right, 'Victoria Dubourg' (1868-1869) Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at left, 'Portrait d'homme' [Portrait of a man] (c. 1866) and at right, 'Victoria Dubourg' (1868-1869)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-z.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at left, 'Portrait d'homme' [Portrait of a man] (c. 1866) and at right, 'Victoria Dubourg' (1868-1869) Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne Installation view of the exhibition 'Degas: A New Vision' at the National Gallery of Victoria International, Melbourne showing at left, 'Portrait d'homme' [Portrait of a man] (c. 1866) and at right, 'Victoria Dubourg' (1868-1869)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-v.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Mme Jeantaud sur sa chaise longue, avec deux chiens' [Madame Jeantaud on her chaise longue, with two dogs] 1877 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Mme Jeantaud sur sa chaise longue, avec deux chiens' [Madame Jeantaud on her chaise longue, with two dogs] 1877 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-x.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Mme Jeantaud sur sa chaise longue, avec deux chiens' [Madame Jeantaud on her chaise longue, with two dogs] 1877 (installation view detail) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Mme Jeantaud sur sa chaise longue, avec deux chiens' [Madame Jeantaud on her chaise longue, with two dogs] 1877 (installation view detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-x-detail.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Un bureau de coton à la Nouvelle-Orléans' [A cotton office in New Orleans] 1873 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Un bureau de coton à la Nouvelle-Orléans' [A cotton office in New Orleans] 1873 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/installation-af.jpg)

![Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Un bureau de coton à la Nouvelle-Orléans' [A cotton office in New Orleans] 1873 (installation view) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) 'Un bureau de coton à la Nouvelle-Orléans' [A cotton office in New Orleans] 1873 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/exhi040021_web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.