Exhibition dates: 15th July – 24th October 2010

Many thankx to the National Portrait Gallery, London for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

[River Scene, France]

Negative 1858; print 1860s

Albumen silver print

25.7 × 35.6cm (10 1/8 × 14 in.)

When Camille Silvy originally exhibited this photograph in 1859 (with the title Vallée de l’Huisne), a reviewer wrote: “It is impossible to compose with more artistry and taste than M. Silvy has done. The Vallée de l’Huisne… [is a] true picture in which one does not know whether to admire more the profound sentiment of the composition or the perfection of the details.”

Early collodion-on-glass negatives, such as those Silvy used to render this scene, were particularly sensitive to blue light, making them unsuitable for simultaneously capturing definition in land and sky. Silvy achieved this combination of richly defined clouds and terrain by skilfully wedding two exposures and disguising any evidence of his intervention with delicate drawing and brushwork on the combination negative. The print exemplifies the tension between reality and artifice that is an integral part of the art of photography.

The Huisne River provided power for flour and tanning mills and was significant in the history of Nogent-le-Rotrou, the town where Silvy was born. This photograph was taken from the Pont de Bois, a bridge over the river, looking toward the south and downstream. It was only a few minutes’ walk from Silvy’s birthplace. As the reviewer suggested, it is a sentimental image, an idyllic landscape full of reverence for and memory of a timeless place that was significant in the artist’s development.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

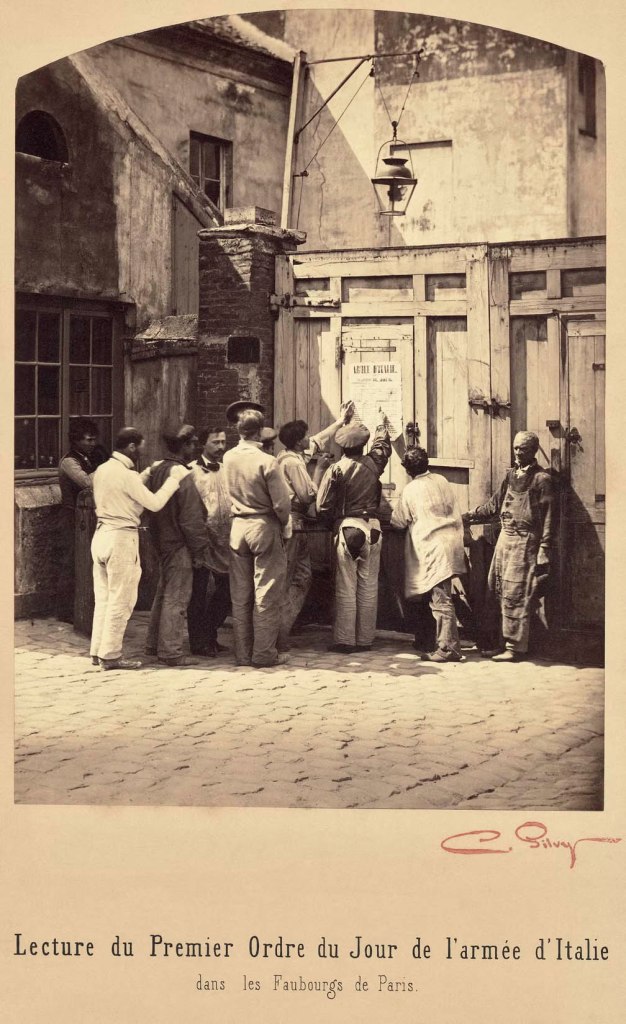

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Lecture du Premier Ordre du Jour de l’armée d’Italie dans Les Faubourgs de Paris

(Reading of the First Agenda of the army of Italy in the suburbs of Paris)

1859

Albumen print

10 x 7 1/4 inches (25.4 x 18.42cm)

© Private Collection, Paris

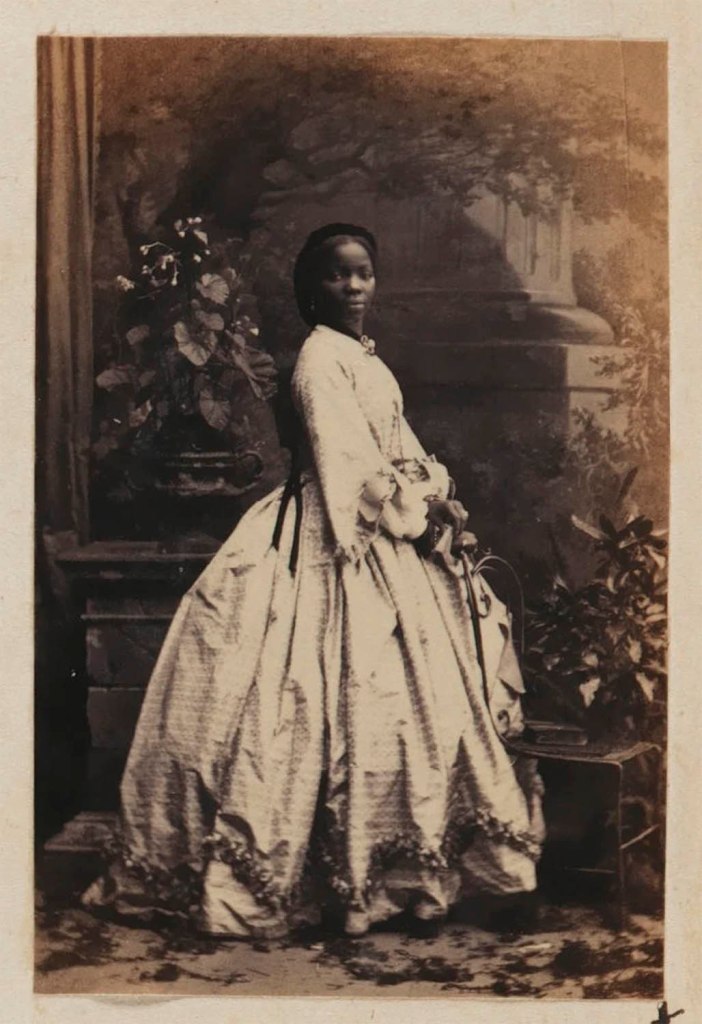

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

James Pinson Labulo Davies and Sarah Forbes Bonetta (Sarah Davies)

1862

© National Portrait Gallery, London

James Pinson Labulo Davies was a 19th-century African merchant-sailor, naval officer, influential businessman, farmer, pioneer industrialist, statesman, and philanthropist who married Sarah Forbes Bonetta in colonial Lagos.

Sara Forbes Bonetta, otherwise spelled Sarah, was a West African Egbado princess of the Yoruba people who was orphaned in intertribal warfare, sold into slavery and, in a remarkable twist of events, was liberated from enslavement and became a goddaughter to Queen Victoria. She was married to Captain James Pinson Labulo Davies, a wealthy Victorian Lagos philanthropist.

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Aina (Sarah Forbes Bonetta (later Davies))

15 September 1862

From Album 9 (Daybook Volume 9)

Albumen print

3 1/4 in. x 2 1/4 in. (83 mm x 56 mm) image size

National Portrait Gallery, London

Purchased, 1904

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Now best known as Sarah Forbes Bonetta, Aina lived a life of extraordinary contrasts. Her story is one of displacement and reveals how she was fetishized in both Africa and England. Born in modern-day south-west Nigeria, Aina was about five years old when she was captured by soldiers of King Ghezo of Dahomey, a central figure in the transatlantic slave trade. She was discharged by the King to Captain Frederick Forbes, who was sent to west Africa to persuade the King to abandon slavery. He bargained to save the child, convincing the King to send her as a ‘gift’ to Queen Victoria. Before setting sail for England on board HMS Bonetta, Forbes had Aina baptised Sarah Forbes Bonetta. This stripped her of her original name ‘Aina’ and symbolically, of her west-African identity. The Queen, impressed by the young girl’s intelligence and dignity, became her protector, funding her education and providing for her welfare. She became one of the Queen’s favourites and by her late teens, had entered elite society. She was highly regarded in the royal household, appearing at many social events including the wedding of Princess Victoria, the Queen’s eldest daughter. It was at one such event that a Sierra Leonian merchant, prominent in missionary circles, first saw her and declared his interest in marrying her. The match was considered a suitable one and Aina was encouraged to accept the proposal from widower James Pinson Labulo Davies. In 1862, the couple married in a lavish wedding featuring ten carriages. They settled in colonial Lagos, naming their first child Victoria with the Queen’s blessing. When Aina died of tuberculosis in Madeira, aged just 37, the Queen wrote: “Saw poor Victoria Davies, my black godchild, who learnt this morning of the death of her dear mother.” Caught up in Britain’s imperial ambitions and plunged into Victorian high society, Aina had crossed immense boundaries between places, cultures and identities – often without a choice.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery, London website

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Silvy in his Studio with his Family

1866

© Private Collection, Paris

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Proof sheet of Madame Silvy

c. 1865

© Private Collection, Paris

This is the first retrospective exhibition devoted to Camille Silvy, pioneer of street photography, early image manipulation and photographic mass production. The exhibition includes photographs not seen for over 150 years.

The first retrospective exhibition of work by Camille Silvy, one of the greatest French photographers of the nineteenth century, will open at the National Portrait Gallery this summer. Marking the centenary of Silvy’s death, Camille Silvy, Photographer of Modern Life, 1834-1910, includes over a hundred objects, many of which have not been exhibited since 1860. The portraits on display offer a unique glimpse into nineteenth-century Paris and Victorian London through the eyes of one of photography’s greatest innovators.

Focusing on Silvy’s ten-year creative burst from 1857-67 when he was working in Algiers, rural France, Paris and London, the exhibition will show how Silvy pioneered many branches of the photographic medium including theatre, fashion, military and street photography. Working under the patronage of Queen Victoria, Silvy photographed royalty, statesmen, aristocrats, celebrities, the professional classes, businessmen and the households of the country gentry. Silvy’s London studio was a model factory producing portraits in the new carte de visite format – small, economically priced, and collectable. Silvy played an important role in the popularity of the carte de visite format in London and these portraits show how the modern and fashionably dressed looked. Silvy’s Bayswater studio, with a staff of forty, produced over 17,000 portraits.

Works on display will include River Scene, France (1858), considered Silvy’s masterpiece, alongside his London series on twilight, sunlight and fog. Anticipating our own era of digital manipulation, Silvy created photographic illusions in these works by using darkroom tricks. Mark Haworth-Booth, the curator of this exhibition, claims that Camille Silvy came closest in photography to embodying the vision of ‘the painter of modern life’ sketched out by Charles Baudelaire in a famous essay.

The exhibition draws on works from public and private collections including that belonging to Silvy’s descendants, seen for the first time, along with a cache of letters in which Silvy describes to his parents how he set up and ran his London studio. A selection of Daybooks, providing a unique record of the day to day workings of Silvy’s studio will also be on display. The Daybooks were bought by the National Portrait Gallery in 1904 and are among the rarely seen treasures of the Gallery’s photography collection. Albums, documents, a dress worn by Silvy’s wife for a portrait session in 1865 and other items which build up a picture of Silvy’s working practice will also be included in the exhibition. The exhibition will illustrate the transformation of photographic art into industry, the beginnings of the democratisation of portraiture and the life of this photographic genius who fell into obscurity.

Born 1834 in Nogent-le-Rotrou, France, Silvy graduated in arts and law and took up a diplomatic post in the French foreign office in 1853 and was first sent to London the following year. In 1857, he joined a six month mission to Algeria to draw buildings and scenes but he soon realised the inadequacy of his talents and turned to photography. Returning to London, he exhibited River Scene, France to immense success in the 3rd annual exhibition of the Photographic Society in Edinburgh and at the first ever Salon of photography as a fine art in Paris. In 1859 he took over the photographic studio of Caldesi and Montecchi at 38 Porchester Terrace in Bayswater, London. After ten years of creative productivity, in 1869, at the age of thirty-five, Silvy retired from photography. He went on to fight with distinction in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 before being diagnosed with folie raisonnante (manic-depression) in 1875. Camille Silvy spent the remaining thirty-one years of his life in psychiatric asylums before dying from bronchopneumonia in the Hôpital de St Maurice, France in 1910.

Press release from the National Portrait Gallery website [Online] Cited 13/10/2010 no longer available online

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

The Misses Booth

1861

Albumen print

© K and J Jacobson Collection, United Kingdom

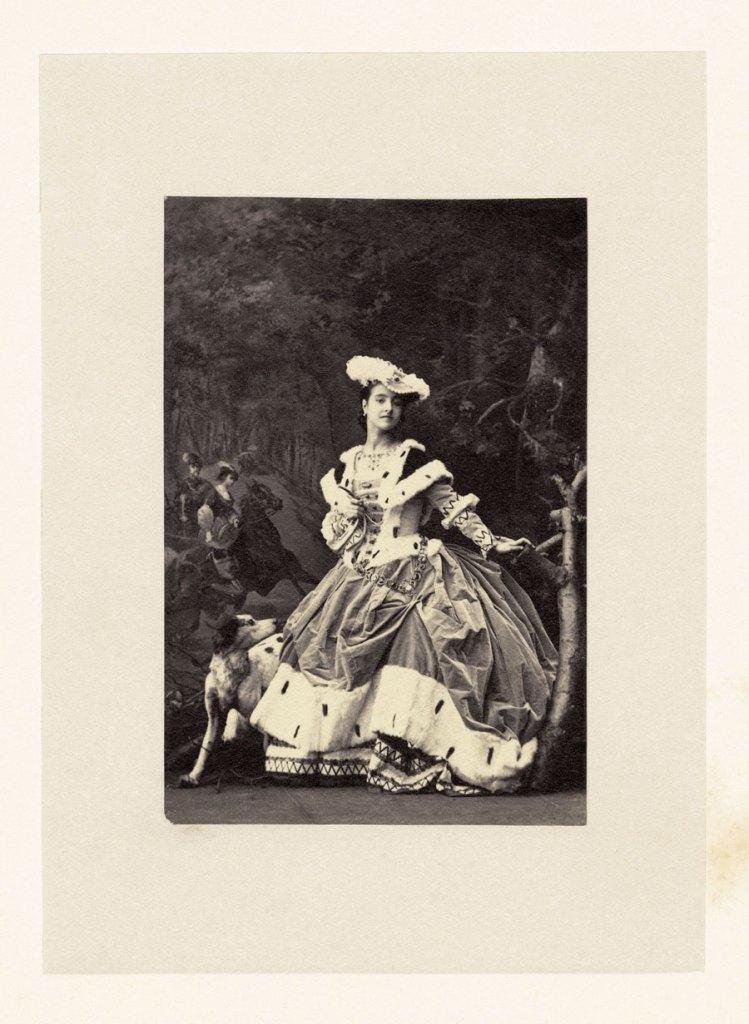

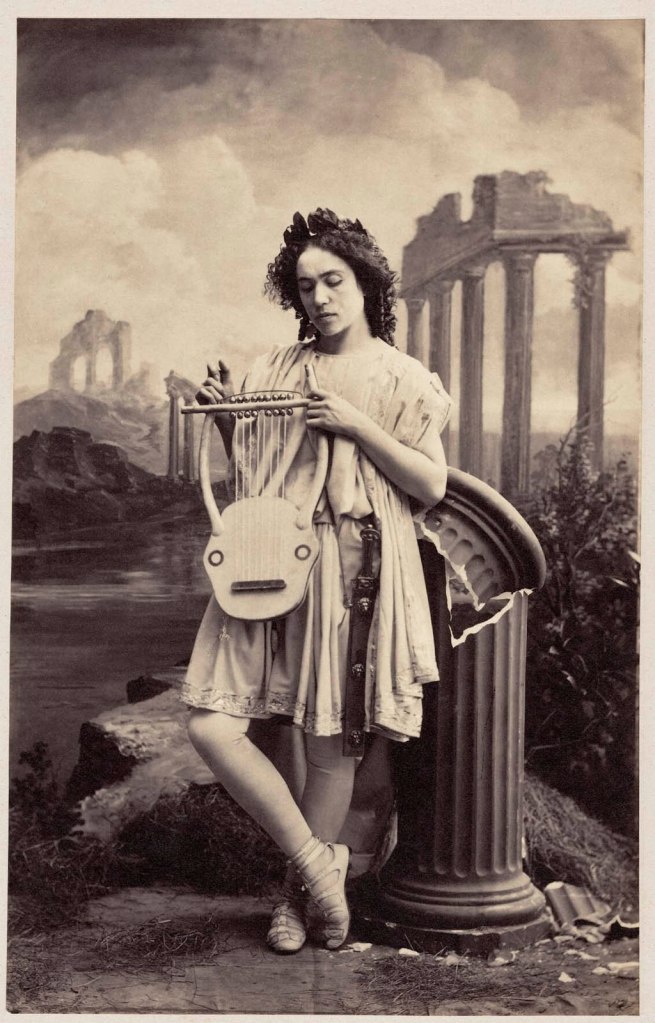

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Adelina Patti as Harriet in Martha

1861

© Private Collection

Adelina Patti (10 February 1843 – 27 September 1919) was an Italian 19th-century opera singer, earning huge fees at the height of her career in the music capitals of Europe and America. She first sang in public as a child in 1851, and gave her last performance before an audience in 1914. Along with her near contemporaries Jenny Lind and Thérèse Tietjens, Patti remains one of the most famous sopranos in history, owing to the purity and beauty of her lyrical voice and the unmatched quality of her bel canto technique.

The composer Giuseppe Verdi, writing in 1877, described her as being perhaps the finest singer who had ever lived and a “stupendous artist”. Verdi’s admiration for Patti’s talent was shared by numerous music critics and social commentators of her era.

Text from the Wikipedia website

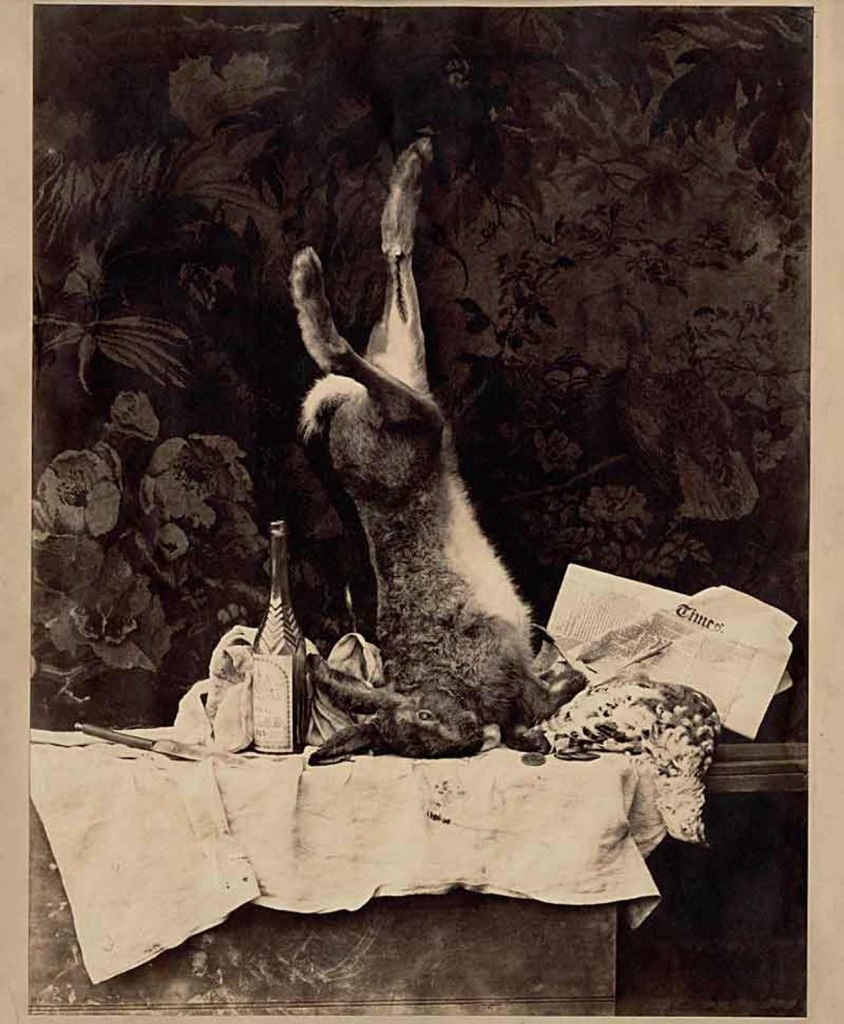

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Studies on Light: Twilight

1859

© Private Collection, Paris

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Hunting Still Life with The Times

After 1859

Albumen print

Dietmar Siegert Collection, Munich

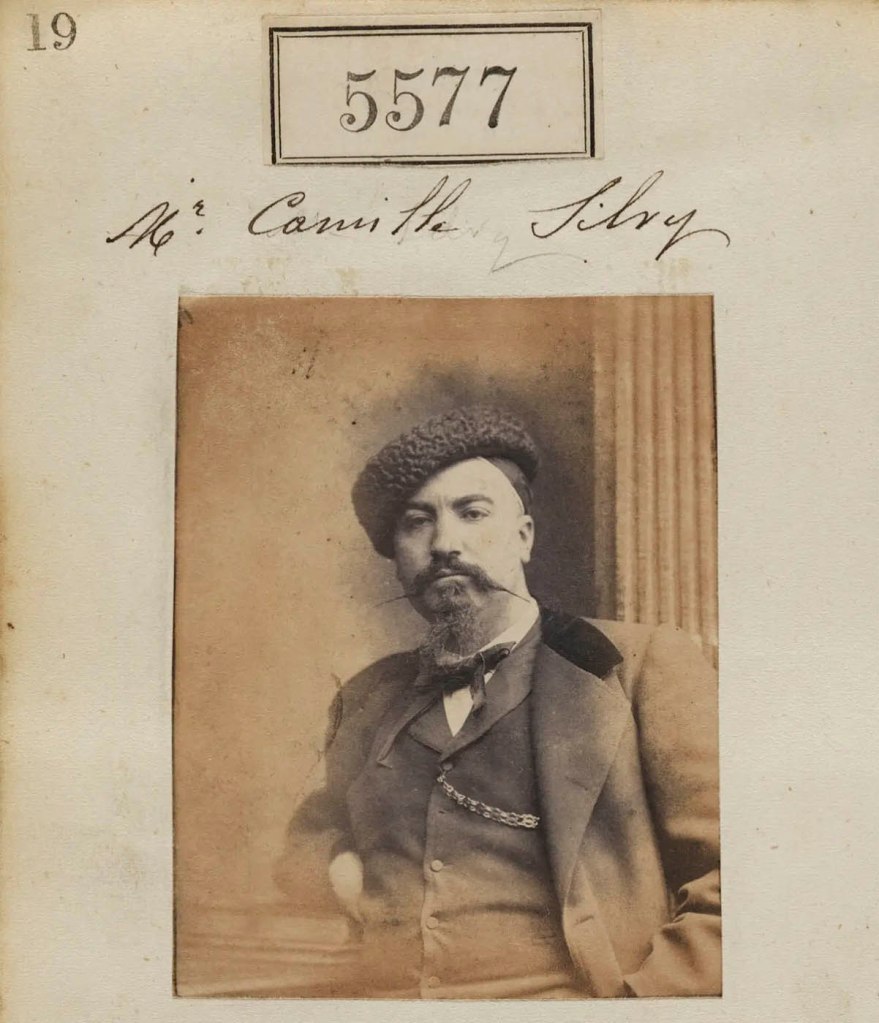

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Rosa Csillag as Orfeo

1860

© Private Collection, Paris

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Mrs Holford’s daughter

Nd

Albumen print

© K and J Jacobson Collection, United Kingdom

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Children at play

Nd

Albumen print

© Private Collection, Paris

Camille Silvy was a pioneer of early photography and one of the greatest French photographers of the nineteenth century. This exhibition includes many remarkable images which have not been exhibited since the 1860s.

Over 100 images, including a large number of carte de visites, focus on a ten-year creative burst from 1857-1867 working in Algiers, rural France, Paris and London, and illustrate how Silvy pioneered many now familiar branches of the medium including theatre, fashion and street photography.

Working under the patronage of Queen Victoria, Silvy photographed royalty, aristocrats and celebrities. He also portrayed uncelebrated people, the professional classes and country gentry, their wives, children and servants. The results offer a unique glimpse into nineteenth-century society through the eyes of one of photography’s outstanding innovators.

Exhibition organised by the Jeu de Paume, Paris, in collaboration with the National Portrait Gallery, London

Introducing Camille Silvy

Camille Silvy was one of the photographic pioneers who burst on the scene in the 1850s.

The great photographer Nadar described him as one of photography’s ‘primitives’ and a ‘zélateur’ or enthusiast. Silvy was born in 1834 in Nogentle-Rotrou, about forty miles west of Chartres, trained in law and became a diplomat.

Silvy took up photography as an amateur in 1857 and his work was first exhibited in 1858. He gave up his career in the French diplomatic service, moved from Paris to London, and set up a portrait studio in fashionable Bayswater, just north of Hyde Park. Silvy met and married Alice Monnier in 1863.

Portraits of Silvy capture his passionate horsemanship and dashing presence. He portrayed his wife on many occasions, dressed in the most elegant fashions. Silvy’s self-portraits show him posing in his studio or in impressive fancy-dress. The most characteristic self-portrait presents him four times over: Silvy – like Andy Warhol a century later – made his studio a factory.

Early Photographs: Algeria and Rural France

While still a diplomat, Silvy visited Algeria in 1857 on a commission from the Minister of Public Instruction to draw buildings and scenes. He later confessed that ‘when I realised the inadequacy of my talent in obtaining exact views of the places we travelled through, I dedicated myself to photography and … concentrated especially on reproducing everything interesting – archaeologically or historically – that presented itself to me’.

Two of the photographs are shown here. On returning to France, Silvy studied with an innovative amateur, Count Olympe Aguado. Silvy photographed the countryside around Nogent-le-Rotrou. His rural subjects included a self-portrait with a local priest. These rural photographs were shown in the first exhibition devoted to photography as a fine art, held in Paris in spring 1859.

River Scene, France and ‘The Emperor’s Order of the Day’

The climax of Silvy’s photography of his native countryside was ‘River Scene, France’ or ‘La Vallée de l’Huisne’, from the summer of 1858. The river Huisne runs through Silvy’s birthplace, Nogent-le-Rotrou.

Silvy’s subject, modern leisure at the edge of town, became popular with Impressionist painters a decade later. Silvy’s next tableau presented an important moment in French military history. Napoleon III led his army to Italy to drive out the Austrians.

After arriving in Genoa, the Emperor wrote out an Order of the Day for his army. The text was telegraphed to Paris, printed up overnight and posted in the streets of Paris the next morning. The proclamations showed that although the Emperor was away he was still in control of the volatile capital.

The Streets of London

In summer 1859 Silvy established his London studio in Bayswater on the north side of Hyde Park. He chose this location because he was a keen and knowledgeable horseman and wanted to make equestrian portraits. The poet Baudelaire, in his famous essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ (1863), recommended sleek carriages and smart grooms as a subject for modern artists.

Silvy also responded to what the novelist Henry James called ‘the thick detail of London life’. He became entranced by the light effects in the capital’s streets. In this section, three tableaux – ‘Sun’, ‘Twilight’ and ‘Fog’ – comprise his highly original series Studies on Light from autumn 1859. All sorts of special effects and manipulations were required to create the illusion of fog and twilight. It is likely, for example, that four separate negatives were combined to produce Twilight. This picture includes perhaps the first ever deliberate use of blur in a photograph to suggest movement.

London Portrait Studio

Silvy’s studio occupied a house at 38 Porchester Terrace, Bayswater, which is still standing, and the yard behind it (now built over). The yard was used to print out the photographs by sunlight. The reception rooms were grandly appointed, with tapestries, choice furniture, sculptures and Old Master paintings. There was a dressing room in which to prepare for a sitting and the ‘Queen’s Room’ was created to welcome the monarch if she were ever to come to sit for Silvy. She did not but sent her family and friends.

Generally, two poses were recorded, three times each, on one glass negative. When the sitter had chosen which they preferred, the portraits would be printed, gold-toned, trimmed, mounted on card and dispatched by post. Over 17,000 portraits were made here between 1859 and 1868, and over a million prints produced for sale.

Theatre

Portraits of actors and actresses became popular in the 1850s. When Silvy opened his London studio, he sought out stage performers. They needed portraits to sell to fans and Silvy needed sitters. The tactic worked, launching Silvy’s studio and spreading his fame.

Silvy began working with London’s resident theatricals but soon he photographed one of the greatest international operatic stars – Adelina Patti. He portrayed Patti in many of the roles she performed at Covent Garden and she brought the best out of his talent.

Although Patti sometimes seems to be caught by Silvy’s camera in mid-aria, all of his theatre portraits were made in the studio. Given the cumbersome cameras and relatively slow exposures of the period, only studio lighting – natural light, controlled by a system of blinds – provided Silvy with the conditions he required.

Photographing Art

Silvy set up a Librairie photographique in 1860. This was envisaged as a series of photographic facsimiles of illuminated manuscripts. The Manuscrit Sforza was published in two volumes in 1860. Silvy wrote an introduction and set out a typically bold claim for photographic reproduction. He argued that the medium of photography could not merely reproduce manuscripts but also appear to restore them. This was because the standard photographic medium of the time, the wet collodion process, recorded yellow as black.

Another early commercial venture was the reproduction of paintings by Sir Peter Lely at Windsor Castle. These were published as an instalment of Silvy’s magazine, the London Photographic Review – another of his publishing ventures – in 1860.

1867 and after

Silvy wound up his London studio in 1868 but may have taken his last portraits in 1867. There were several reasons for selling up. He was often unwell in London’s coal-smoke-laden atmosphere; he had expended huge amounts of energy on photography and become wealthy; the craze for carte-de-visites had waned and perhaps he wanted to resume his diplomatic career.

In spring 1867 Silvy demonstrated a new photographic system he had designed to record battlefields. From the middle of the Champs Elysées, in the heart of Paris, Silvy produced a panoramic photograph which made the French capital look – prophetically – like a battlefield.

In 1874 he succumbed to what would later be termed manic-depression and spent most of the rest of his life in psychiatric hospitals until his death in 1910. His friend Nadar remembered Silvy in a memoir published in 1889: ‘This photographer and his studio … had no equals’.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery, London website

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Camille Silvy with a boy

August 1859

Albumen print

3 1/4 in. x 2 1/4 in. (82 mm x 57 mm)

National Portrait Gallery, London

Purchased, 1904

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Self-portrait

20 August 1861

National Portrait Gallery, London

Purchased, 1904

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Self-portrait

1863

© Private Collection, Paris

National Portrait Gallery

St Martin’s Place

London WC2H 0HE

Opening hours:

Open daily 10.00 – 18.00

Friday until 21.00

![Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910) '[River Scene, France]' Negative 1858; print 1860s from the exhibition 'Camille Silvy, Photographer of Modern Life, 1834-1910' at the National Portrait Gallery, London, July - Oct 2010 Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910) '[River Scene, France]' Negative 1858; print 1860s from the exhibition 'Camille Silvy, Photographer of Modern Life, 1834-1910' at the National Portrait Gallery, London, July - Oct 2010](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/silvy-river-scene-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.