Exhibition dates: 17th January – 13th September, 2015

Curator: Karen Haas, the MFA’s Lane Curator of Photographs, in collaboration with The Gordon Parks Foundation

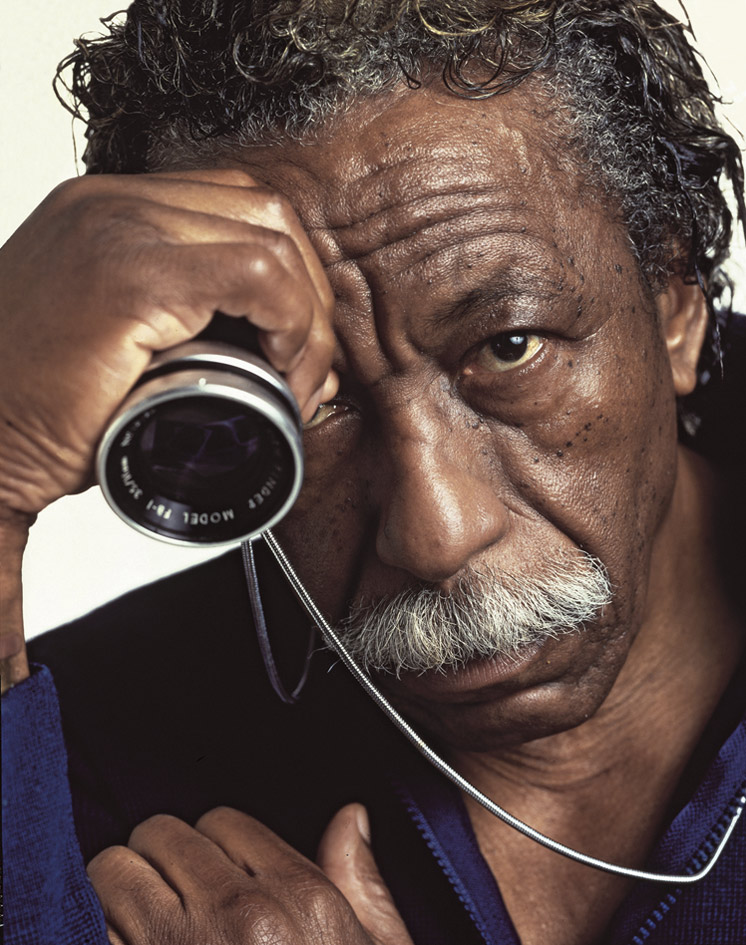

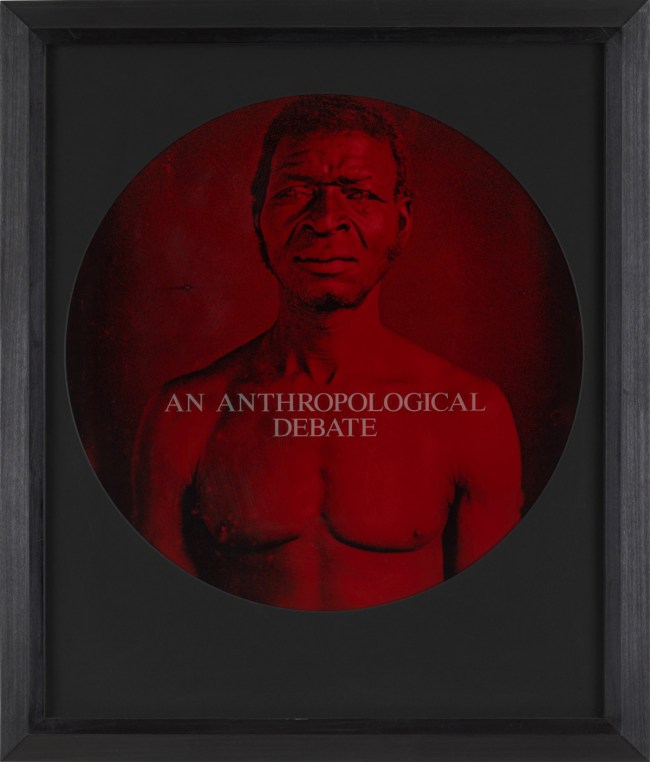

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Husband and Wife, Sunday Morning, Detroit, Michigan

1950

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

It’s been a really tough time writing the Art Blart recently, as my beloved Apple Pro tower that has served me so well over the years has died and gone to god. I have been making do with a small laptop, but tomorrow I pick up my new 27 inch iMac with Retina screen, to pair with my Eizo Flexscan monitor. I can’t wait!

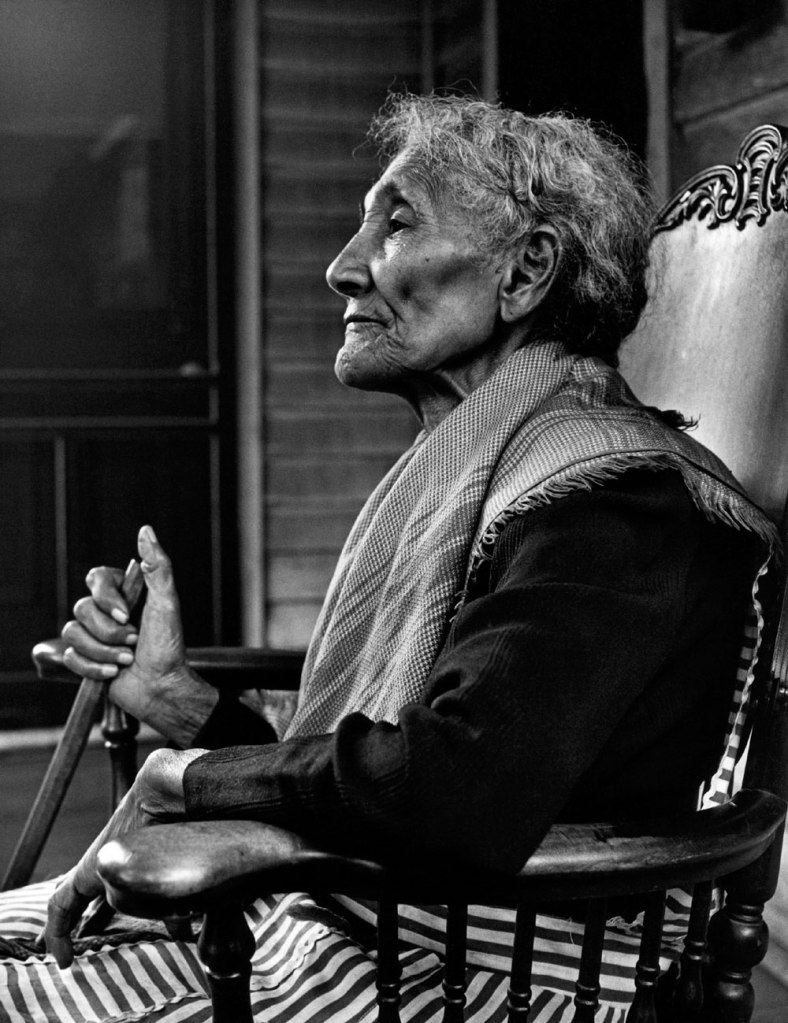

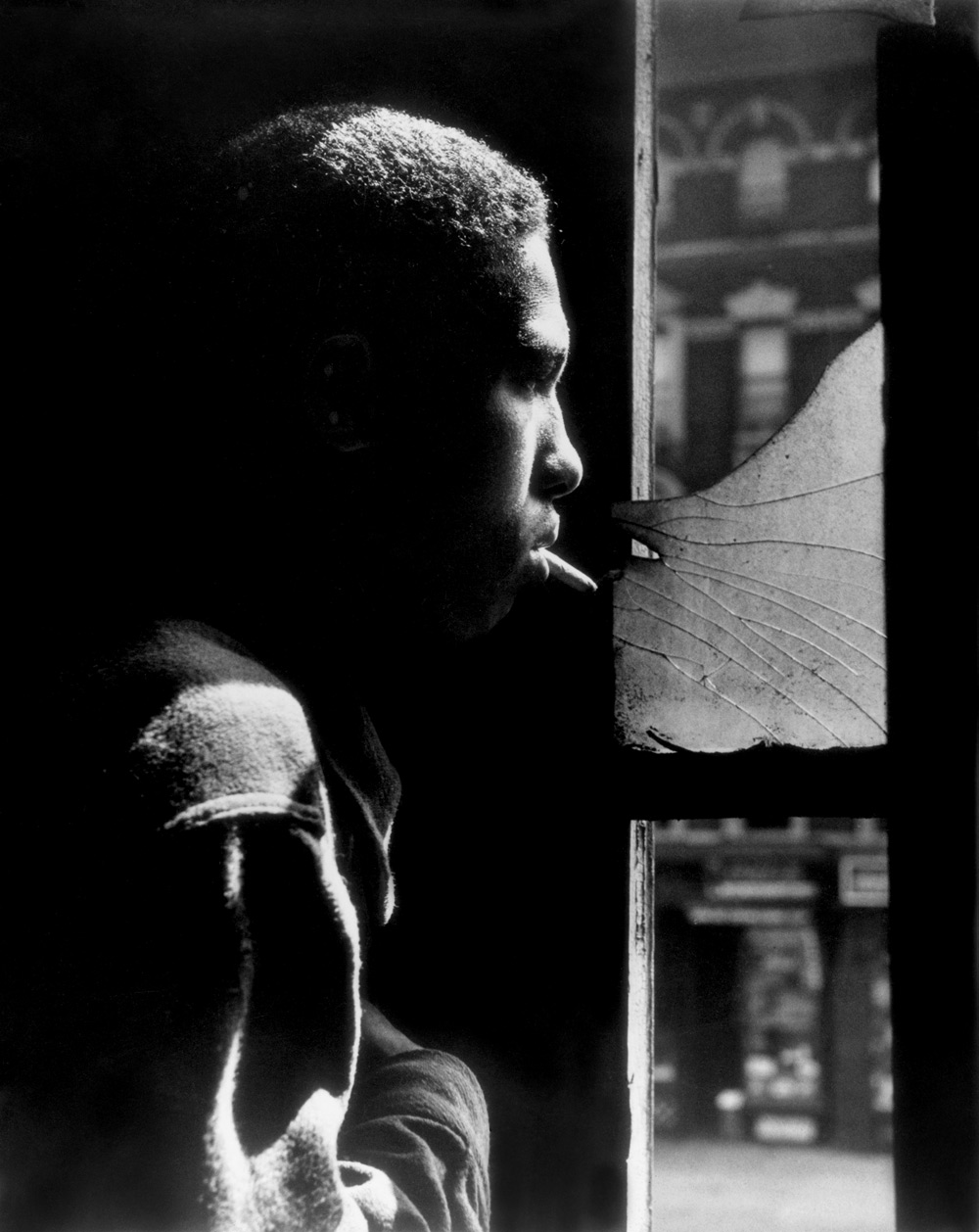

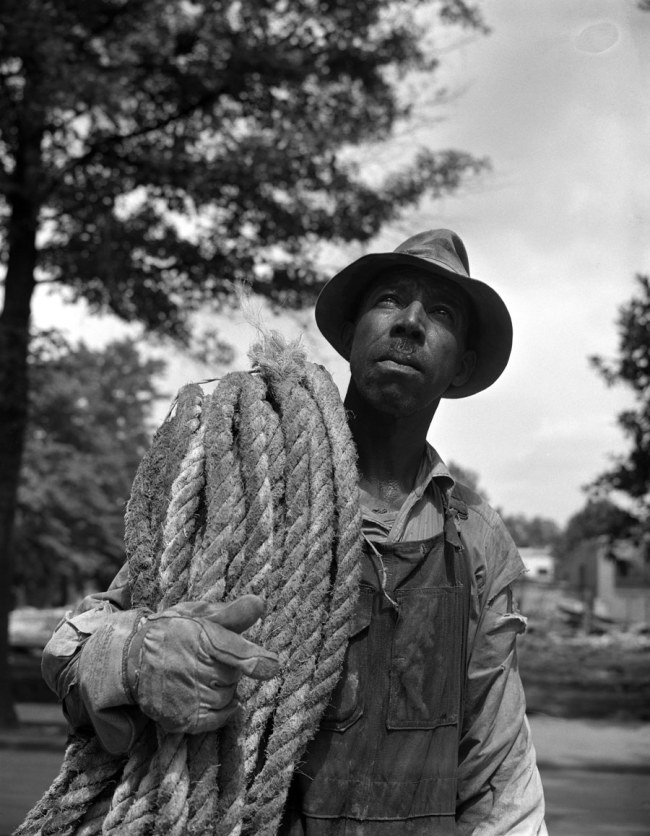

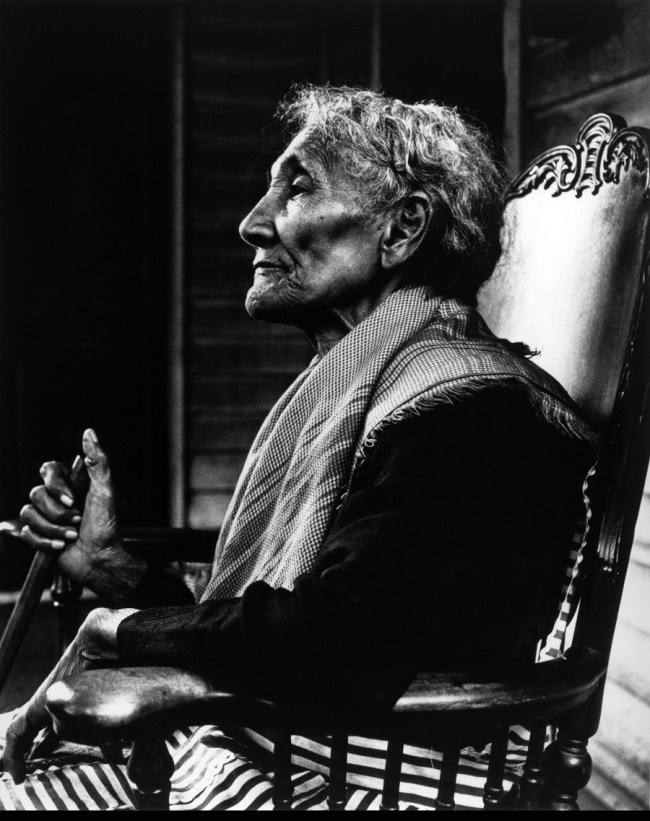

I have so much admiration for the work of this man. The light, the sensitivity to the social documentary narrative just emanates from these images. You don’t need to say much, it’s all there in front of you. Just look at the proud profile of that old woman, Mrs. Jefferson, Fort Scott, Kansas (1950, below), and you are instantly transported back to the slave fields and southern plantations of the 19th century. No words are necessary. The bony hands, gaunt cheeks and determined stare speak of a life hard lived.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

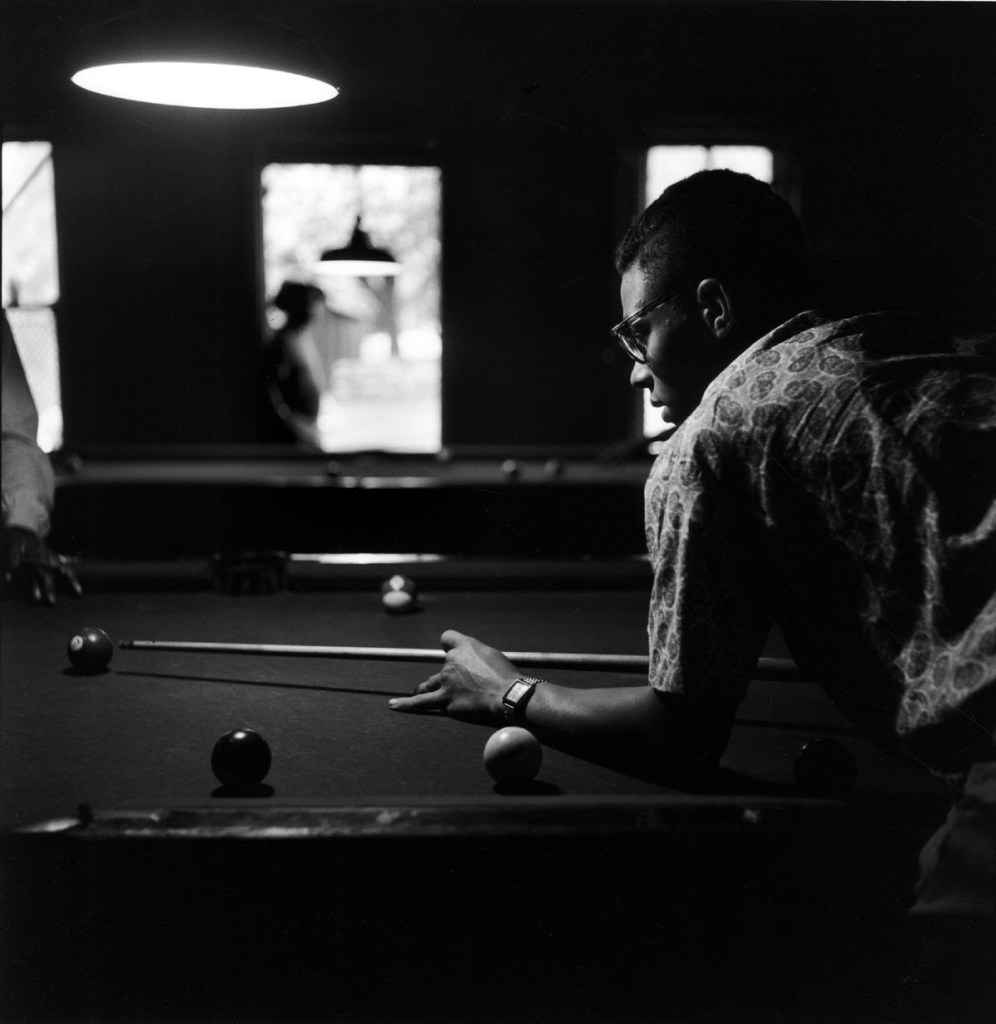

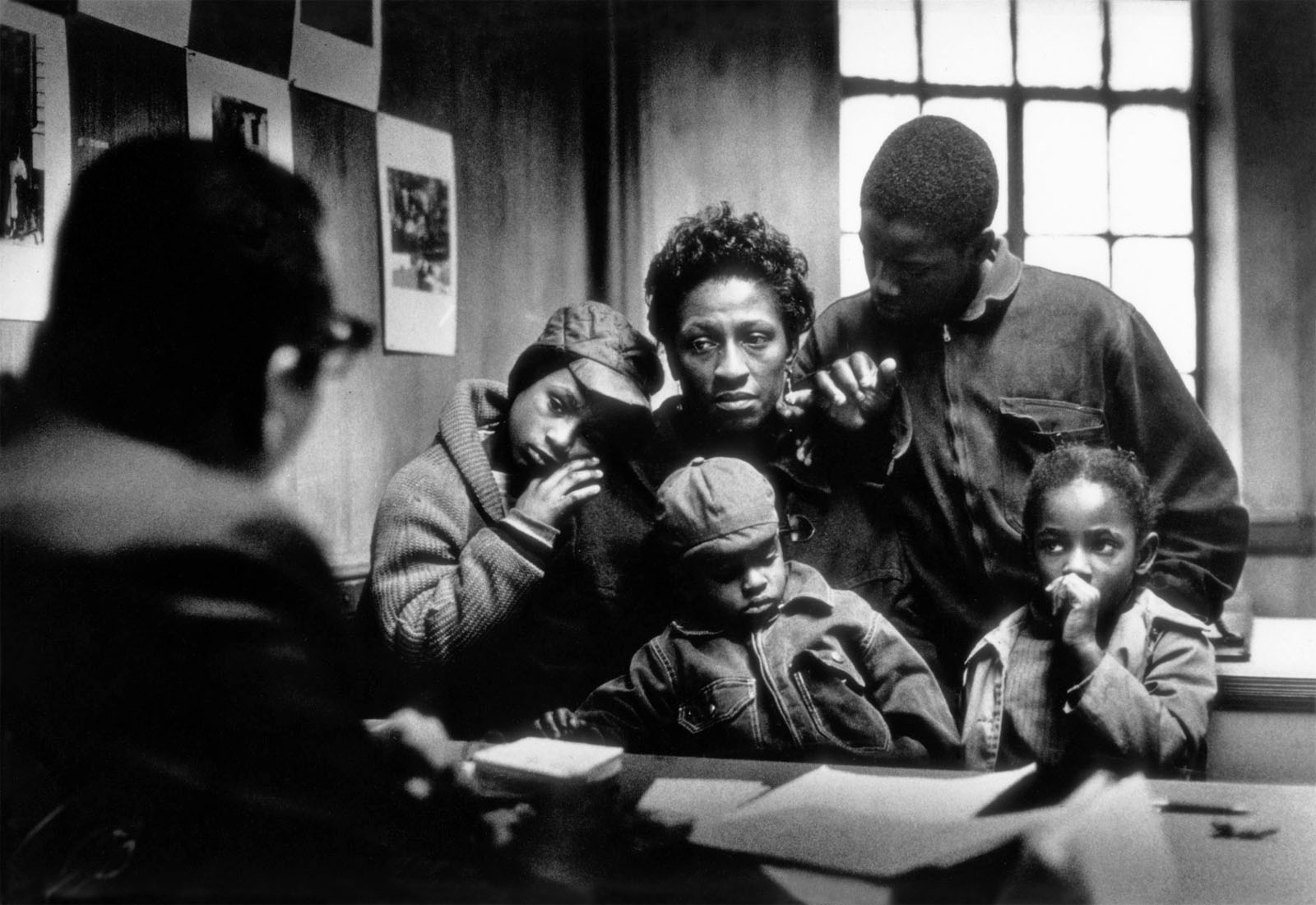

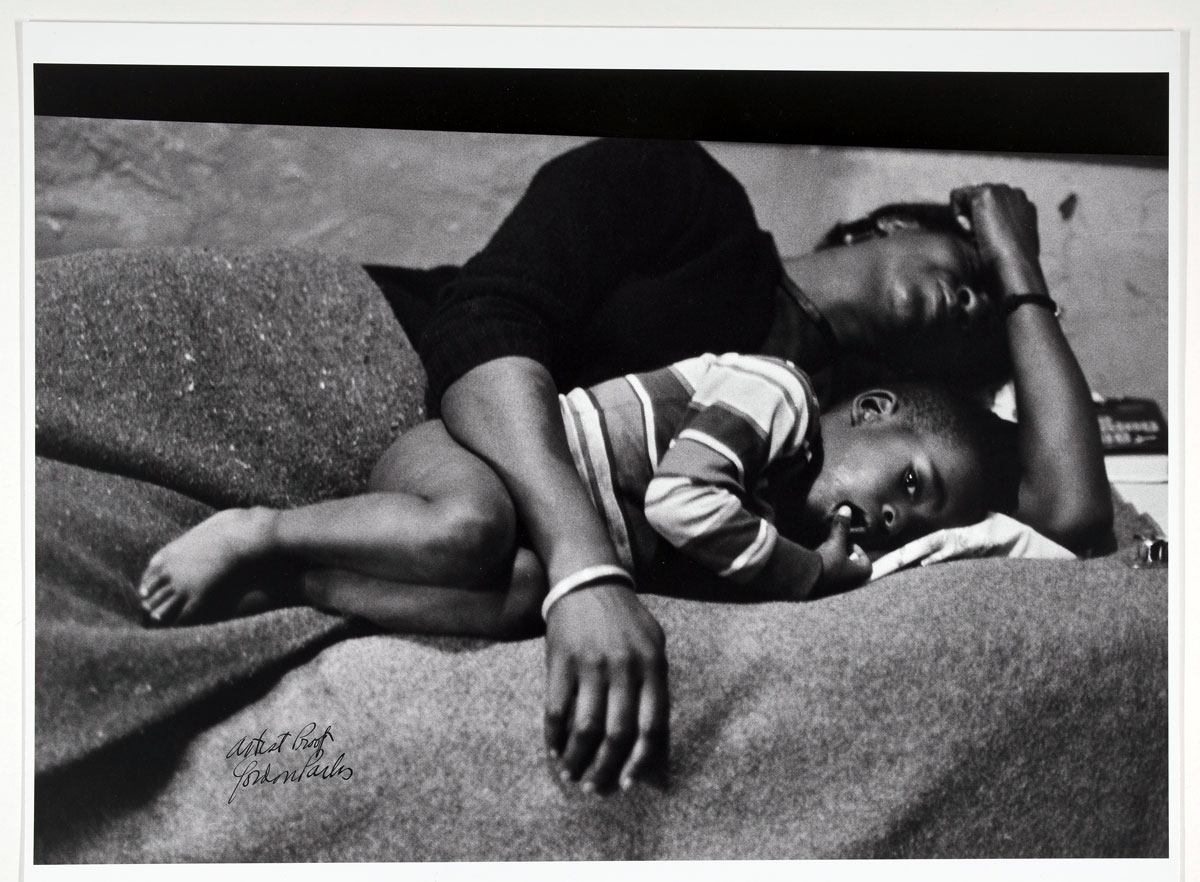

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, St. Louis, Missouri

1950

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

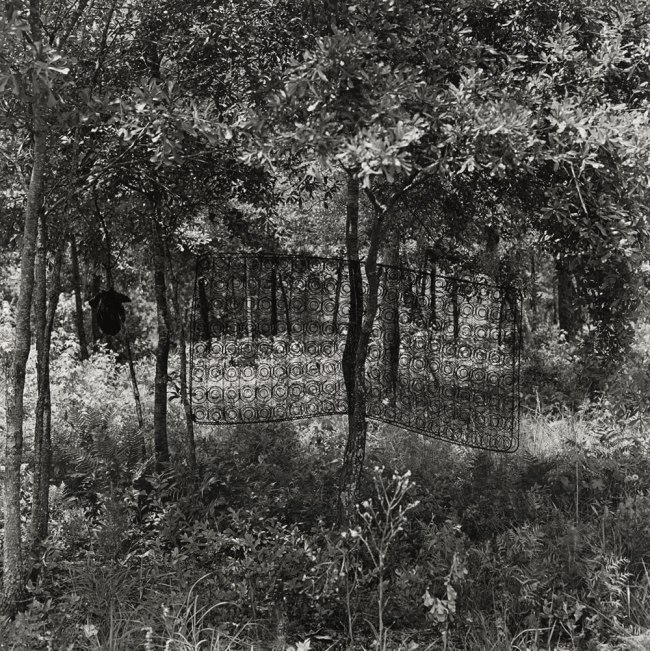

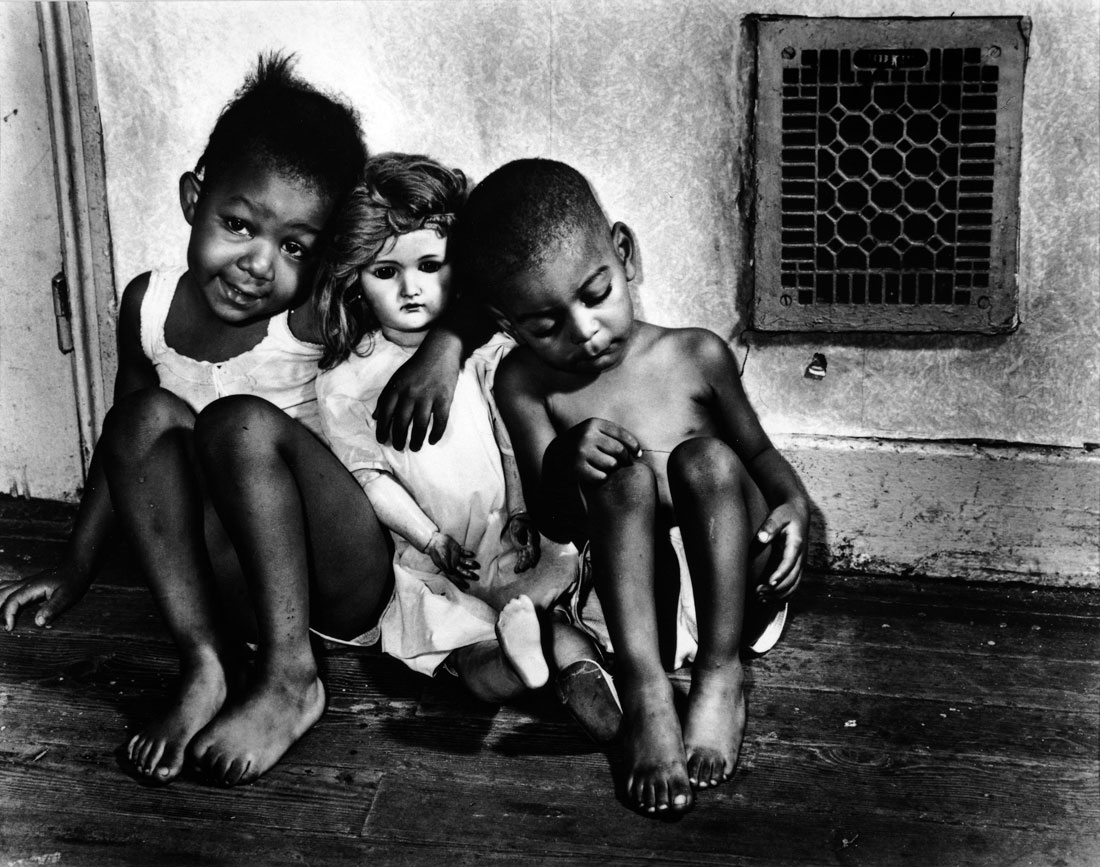

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Tenement Dwellers, Chicago, Illinois

1950

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

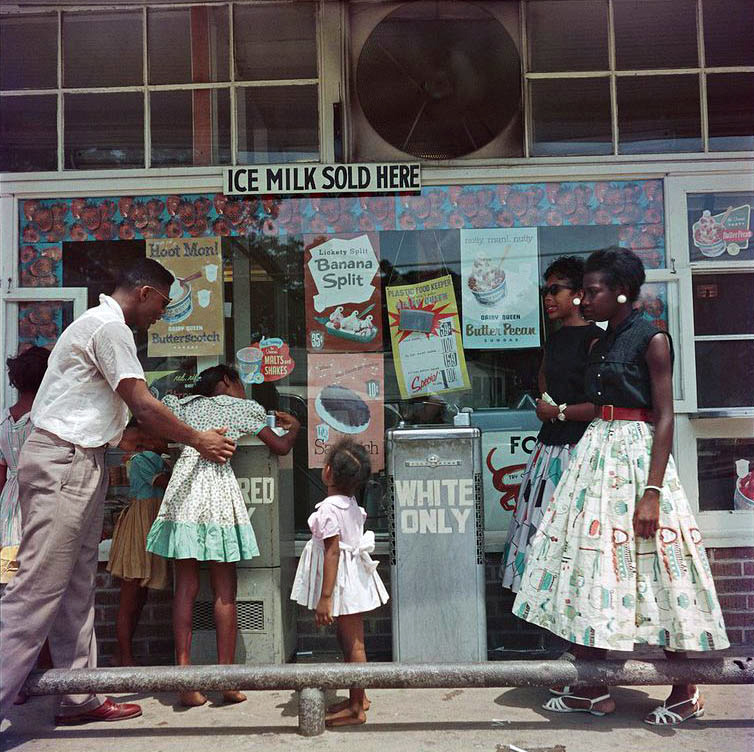

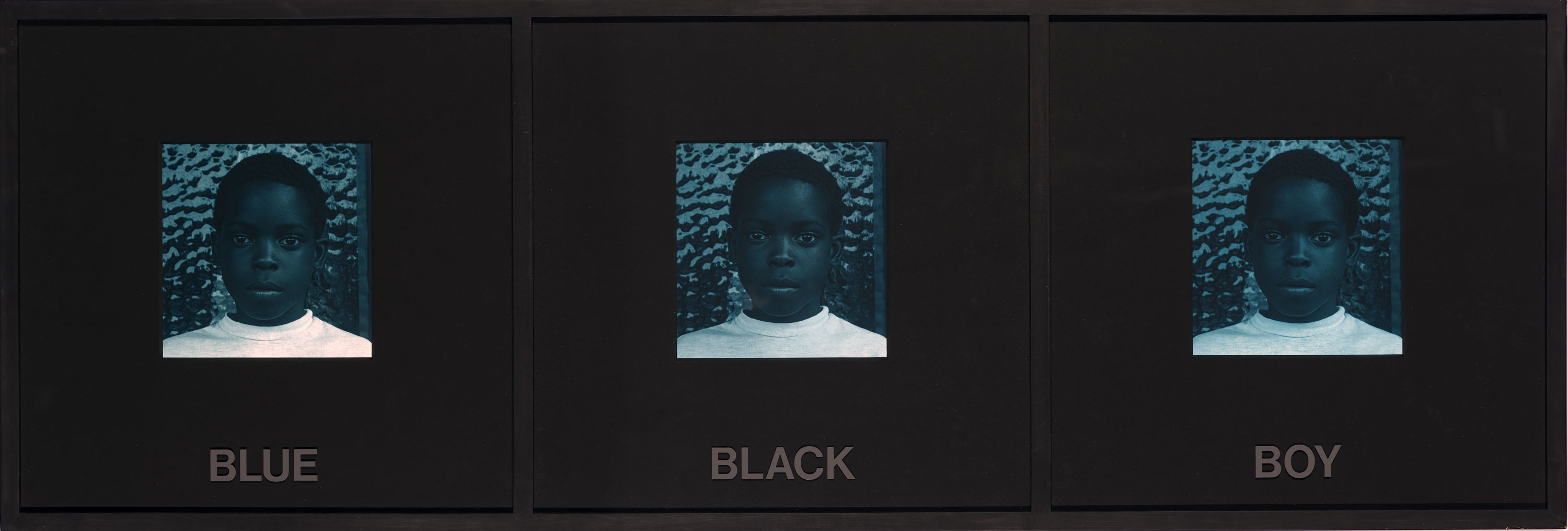

Gordon Parks (1912-2006), one of the most celebrated African-American photographers of all time, is the subject of a new exhibition of groundbreaking photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott (January 17 – September 13, 2015) traces Parks’ return to his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas and then to other Midwestern cities, to track down and photograph each of his childhood classmates. On view in the MFA’s Art of the Americas Wing, the exhibition’s 42 photographs were from a series originally meant to accompany a Life magazine photo essay – but for reasons unknown, the story was never published. The images depict the realities of life under segregation in 1950 – presenting a rarely seen view of everyday lives of African-American citizens in the years before the Civil Rights movement began in earnest. One of the most personal and captivating of all Parks’ projects, the images, now owned by The Gordon Parks Foundation, represent a rare and little-known group within Parks’ oeuvre. This exhibition, on view in the Robert and Jane Burke Gallery, is accompanied by a publication by Karen Haas, the MFA’s Lane Curator of Photographs, in collaboration with The Gordon Parks Foundation, which includes an introduction by Isabel Wilkerson, Pulitzer-prize winning author of The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. The book includes previously unpublished photographs as well as archival materials such as contact sheets and a portion of the 1927 yearbook from the segregated school Parks attended as a child.

“These personal and often touching photos offer a glimpse into the life of Gordon Parks and the prejudice that confronted African Americans in the 1940s and 1950s,” said Malcolm Rogers, Ann and Graham Gund Director at the MFA. “We’re grateful to The Gordon Parks Foundation for giving us the opportunity to display these moving works.”

Fort Scott, Kansas was an emotional touchstone for Gordon Parks and a place that he was drawn to over and over again as an adult, even though it held haunting memories of racism and discrimination. Parks was born in Fort Scott in 1912 to a poor tenant farmer family and left home as a teenager after his mother died and he found himself – the youngest of 15 children – suddenly having to make his own way in the world. By 1948, Parks was the first African-American photographer hired full time by Life magazine. One of the rare African-American photojournalists in the field, Parks was frequently given magazine assignments involving social issues that his fellow white photographers were not asked to cover. For an assignment on the impact of school segregation, Parks returned to Fort Scott to revisit early memories of his birthplace – many involving racial discrimination – and to reconnect with childhood friends, all of whom went to the same all-black elementary school that Parks had attended. He was able to track down all but two members of the Plaza School Class of 1927, although only one was still living in Fort Scott at the time. As he met with fellow classmates, his story quickly shifted its focus to the Great Migration north by African Americans. Over the course of several days Parks visited with his childhood friends – by this time residing in Kansas City; Saint Louis; Columbus, Ohio; Detroit; and Chicago – joining them in their parlours and on their front porches while they recounted their life stories to him. Organised around each of these cities and families, the exhibition features previously unpublished photographs as well as a seven-page draft of Parks’ text for the article.

“With the Back to Fort Scott story, Parks showed – really for the first time – a willingness to mine his own childhood for memories both happy and painful, something he would continue to do in a series of memoirs over the course of his long career” said Haas. “The experience also seems to have inspired him to write The Learning Tree in 1963, his best-selling novel about growing up poor and black in Kansas, that he transformed a few years later into a groundbreaking Hollywood movie – the first by an African American writer-director.”

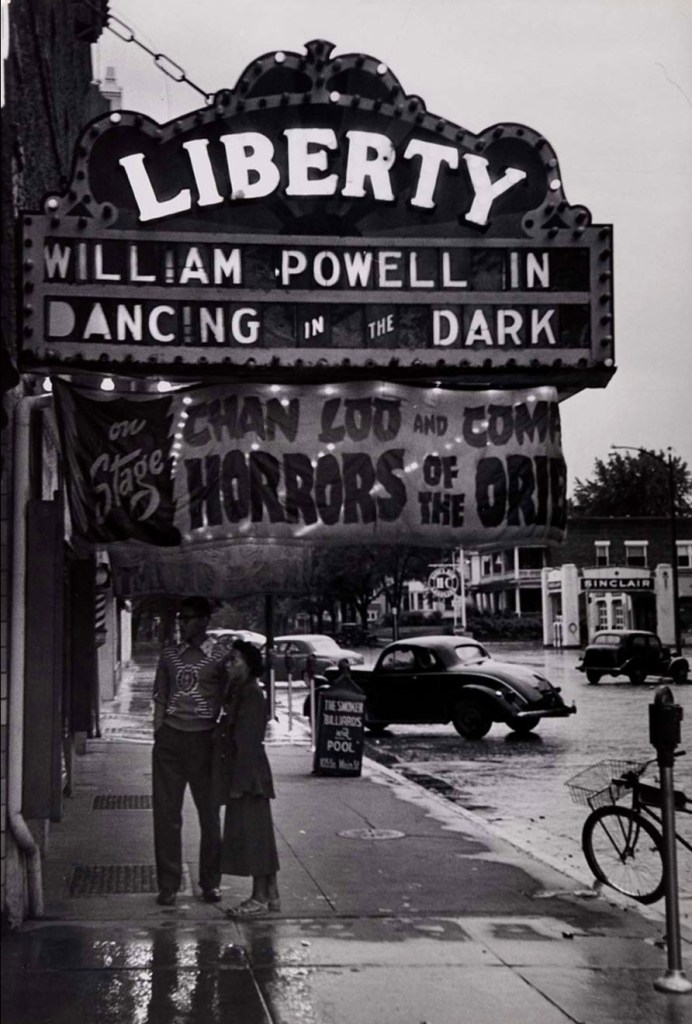

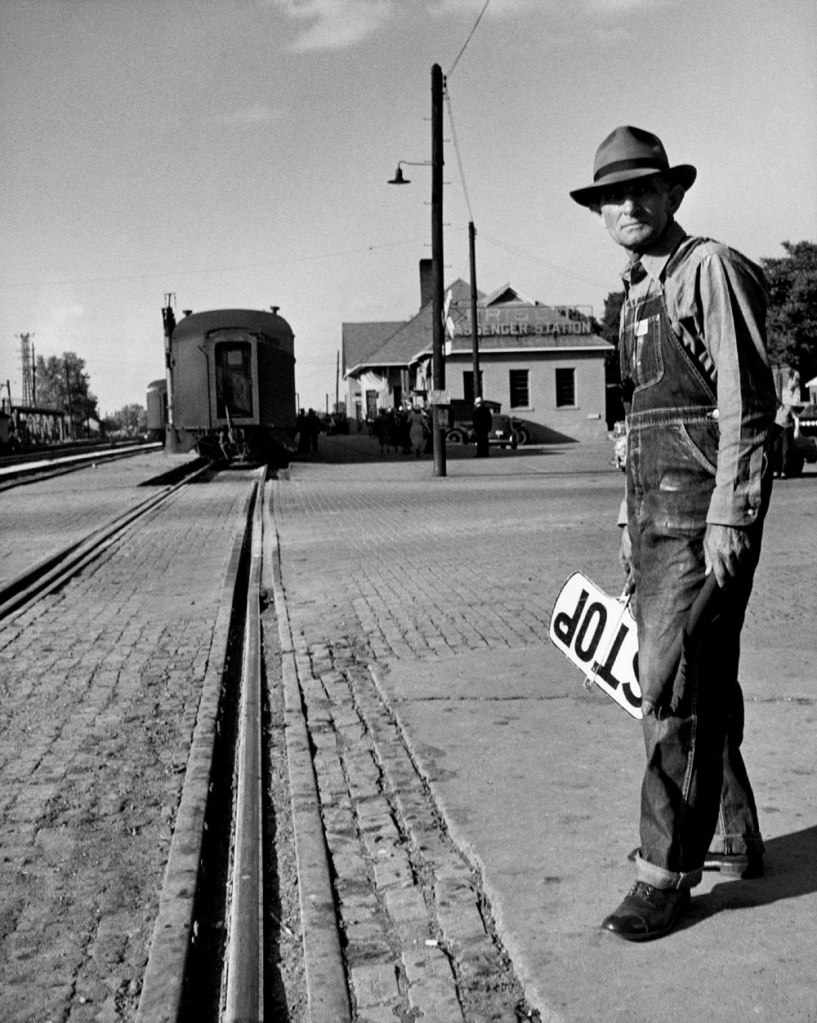

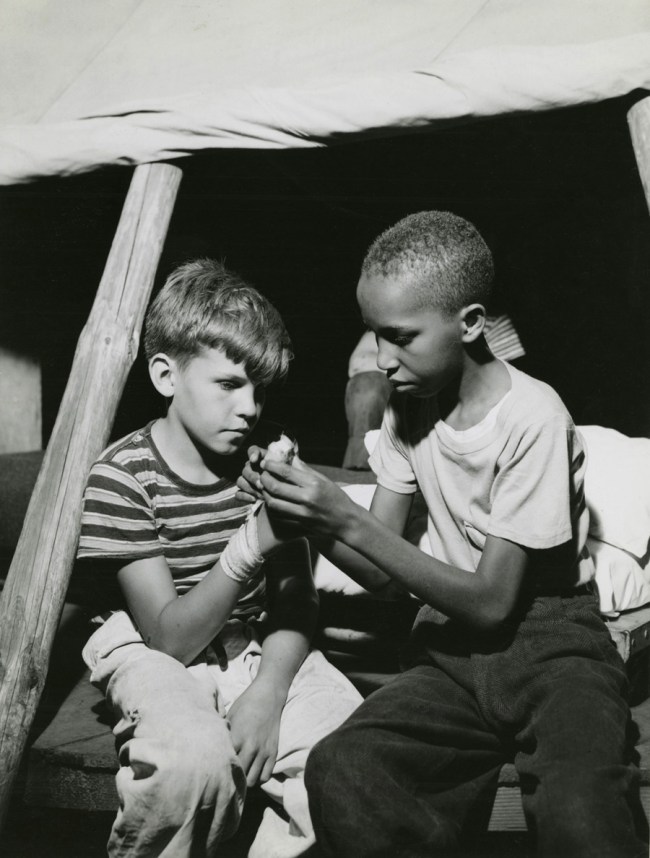

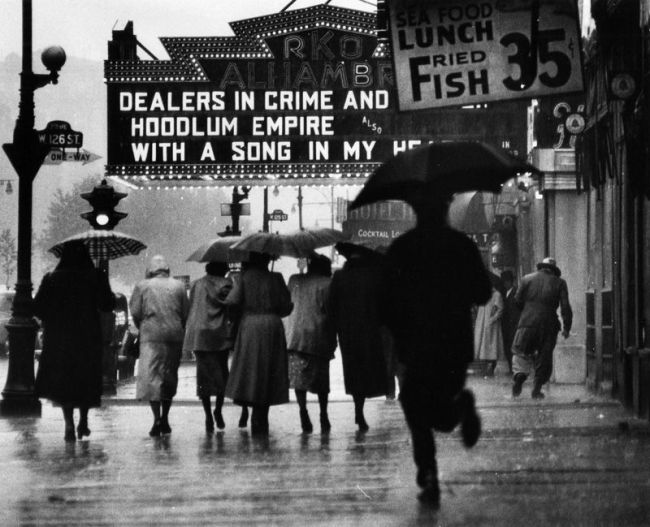

Parks began his research in Fort Scott, where he found classmate Luella Russell. In addition to photographing Luella with her husband and 16-year-old daughter, Parks took photos of his own family and life around town – finding friends and acquaintances at the local theatre, railway station and pool hall. Parks also visited the local baseball field at Othick Park, where he recorded a group of white spectators seated at one end of the bleachers watching a game, while two African-American girls in summer dresses stand at the other end, in an area loosely designated for the town’s black residents. Parks’ image of the girls at the ballpark, where black and white baseball teams sometimes competed against each other, subtly refers to the separation of the races that marked much of everyday life in Fort Scott.

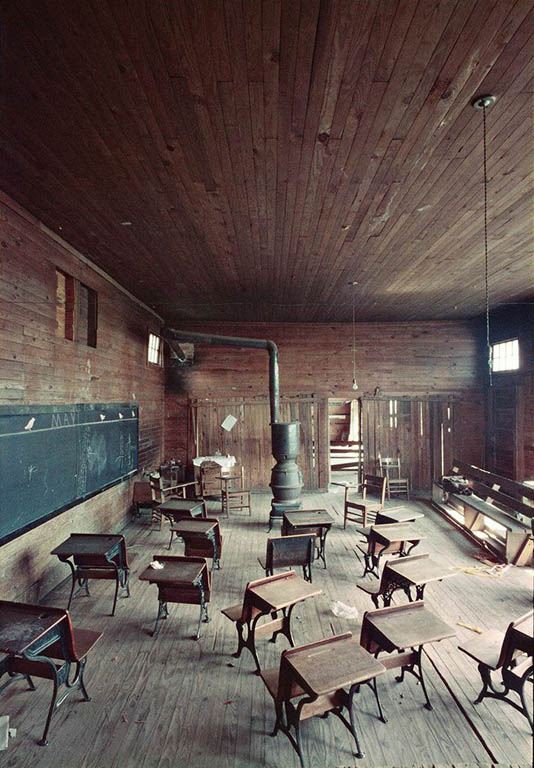

Fort Scott had not changed dramatically since Parks’ youth. Parks attended the all-black Plaza School through the ninth grade in 1927, and as he wrote in his draft for Life magazine: “Twenty-four years before I had walked proudly to the centre of the stage and received a diploma. There were twelve of us (six girls and six boys) that night. Our emotions were intermingled with sadness and gaiety. None of us understood why the first years of our education were separated from those of the whites, nor did we bother to ask. The situation existed when we were born. We waded in normal at the tender age of six and swam out maladjusted… nine years later.”

After Fort Scott, Parks discovered three of his classmates in Kansas City and St. Louis – cities that were easily reached by rail and were often the first stops made by African Americans leaving smaller towns. Many left towns like Fort Scott in the hope of finding jobs and better futures for their children in these larger, more industrial cities. When Parks tracked down his classmates, he recorded their jobs and wages – the sort of detail that Life typically included in such pieces, allowing its readers to measure their own lives against a story’s subjects. In Kansas City, classmate Peter Thomason was working as a postal transportation clerk (a position, Parks noted, with a minimum salary of $3,700 a year), while in St. Louis, Parks recorded that classmate Norman Earl Collins was doing quite well, making $1.22 an hour at Union Electric of Missouri. Parks’ sympathetic images of Earl and his daughter, Doris Jean, may have been a conscious effort on Parks’ part to offset contemporary stereotypes of black families as less stable and strong than their white counterparts.

By 1950, Chicago was the de facto capital of African-American life in the US, with more black inhabitants than any other city in America – including three of Parks’ classmates. Parks discovered them residing only a mile or two apart from one another on the city’s South Side. Untitled, Chicago, Illinois (1950), depicts Parks’ classmate Fred Wells and his wife Mary in front of their apartment building in the Washington Park neighbourhood. A number of the photographs in the exhibition repeat the simple compositional device seen here – featuring a classmate and his or her family, framed by the front door of their home. These images highlighted the families’ similarities to, rather than differences from Life‘s readers, who would have found such strong representations of black families at once surprising and reassuring.

In Detroit, Parks traced classmate Pauline Terry to the McDougall-Hunt neighbourhood. In Fort Scott, Pauline had married Bert Collins, who had run a restaurant during much of the 1930s. By 1950, they were settled in Detroit and had five children. Unlike Parks’ other classmates who had migrated north in search of opportunity, Pauline (yearbook ambition: “To be young forever; to be a Mrs.”) now had a large family and no longer worked outside the home. In the course of her conversation with Parks, she emphasised the importance of religion in their lives. Parks’ powerful portrait of the couple walking to Sunday services at the Macedonia Baptist Church, Husband and Wife, Sunday Morning, Detroit, Michigan (1950) reinforces the seriousness of their faith. The cigar-smoking Bert wears a sharp suit and straw boater and carries a well-worn Bible.

Once completed, Parks’ Fort Scott photo essay never appeared in Life. The reason for that remains a mystery, although the US entry into the Korean War that summer had a major impact on the content of its pages for some time. The magazine’s editors did try to resuscitate the story early in April of 1951 only to have it passed over by the news of President Truman’s firing of General Douglas MacArthur. In the end, all that survives, as far as written documentation of the Fort Scott assignment, are Parks’ project notes from his individual visits with his classmates in May and June of 1950; several telegrams sent by Life staffers regarding his friends’ whereabouts before his arrival; fact-checking when the piece was again slated to run in April 1951; and an annotated seven-page draft. Because the photos were never published, and most have never before been on view, the exhibition presents a unique opportunity to explore a body of work that is almost completely unknown to the public.

“The Gordon Parks Foundation is pleased to collaborate with the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, on this exhibition and publication highlighting a series of very personal, early works by the artist” said Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., the Foundation’s executive director. “Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott allows us a focused look at a single Life magazine story and reveals a fascinating tale of Gordon Parks’ segregated beginnings in rural Kansas and the migration stories of his classmates, many of whom, like him, left in search of better lives for themselves and their families.”

Press release from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston website

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Fort Scott, Kansas

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

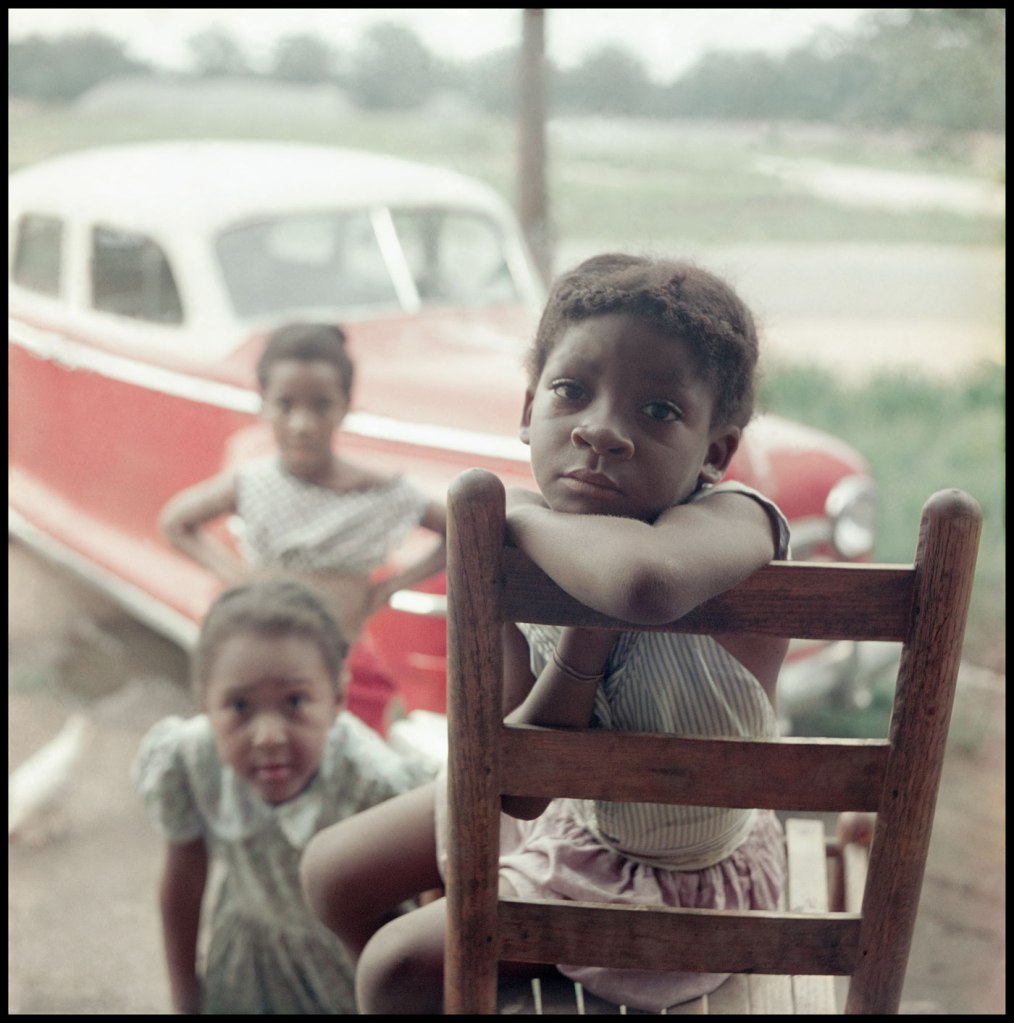

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Fort Scott, Kansas

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

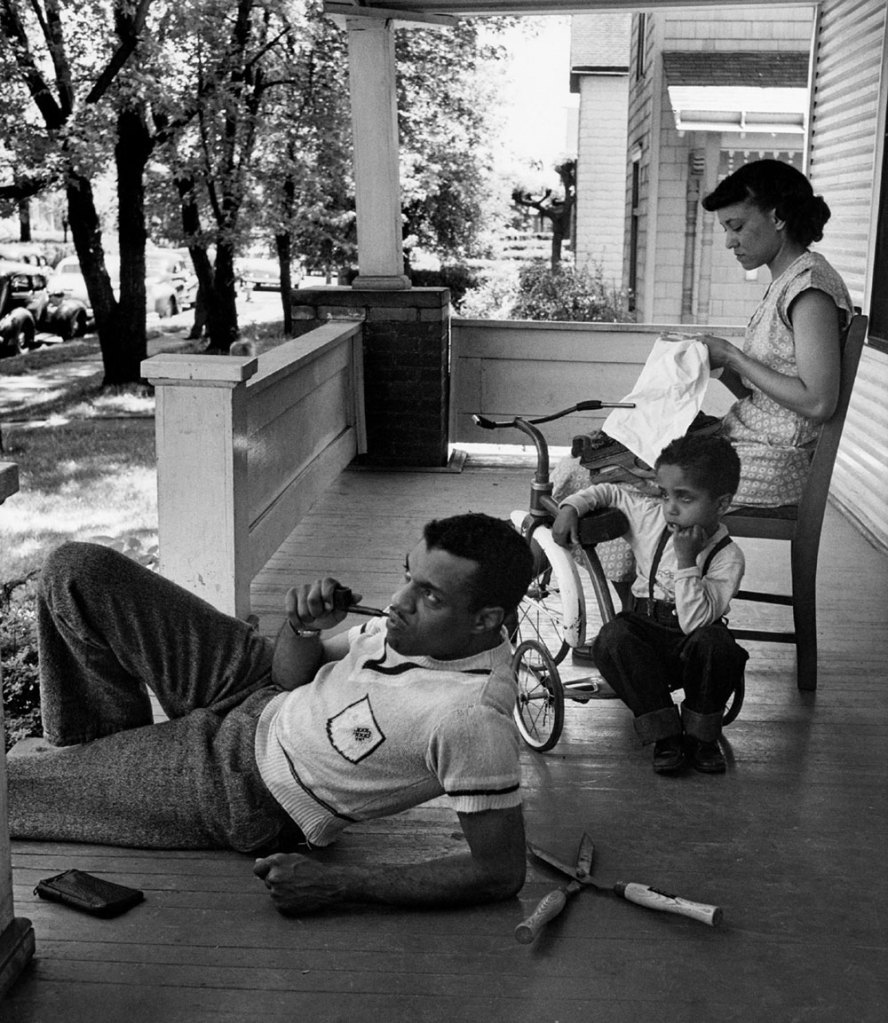

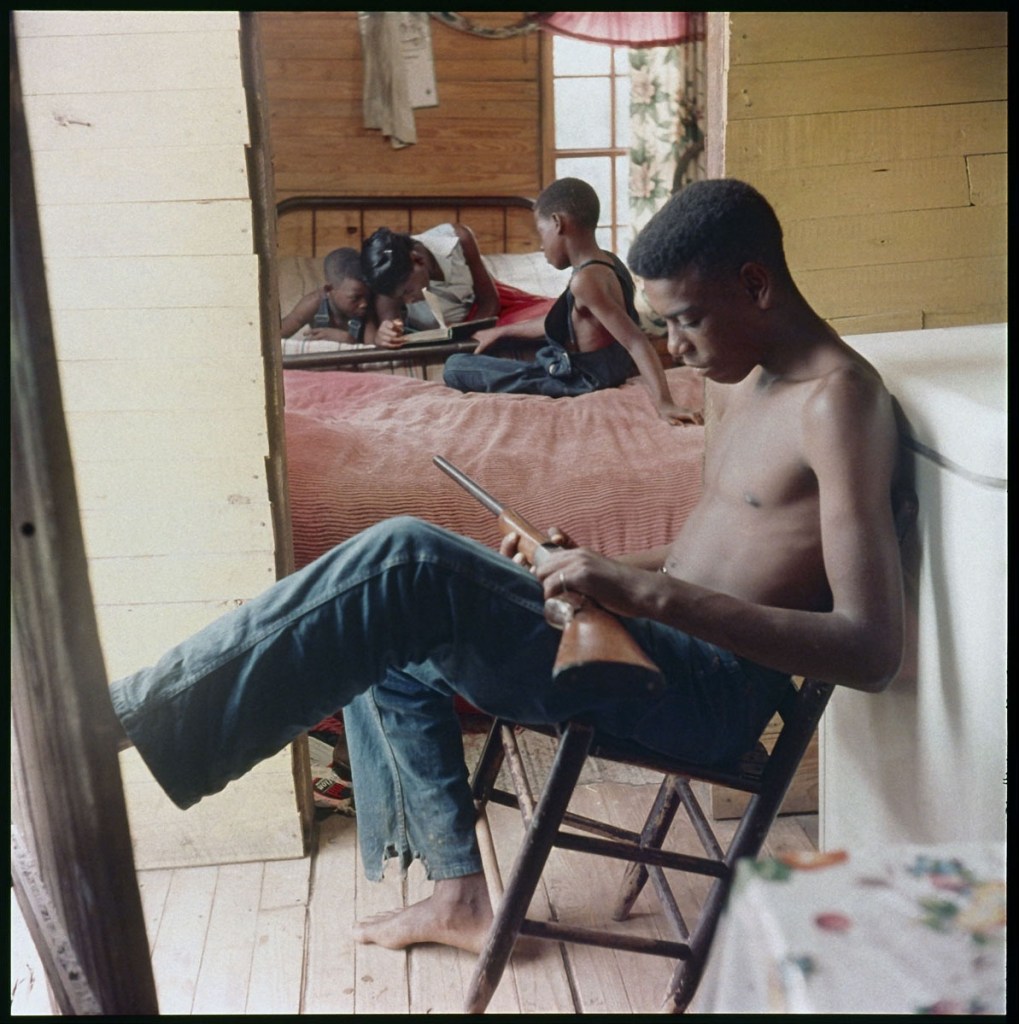

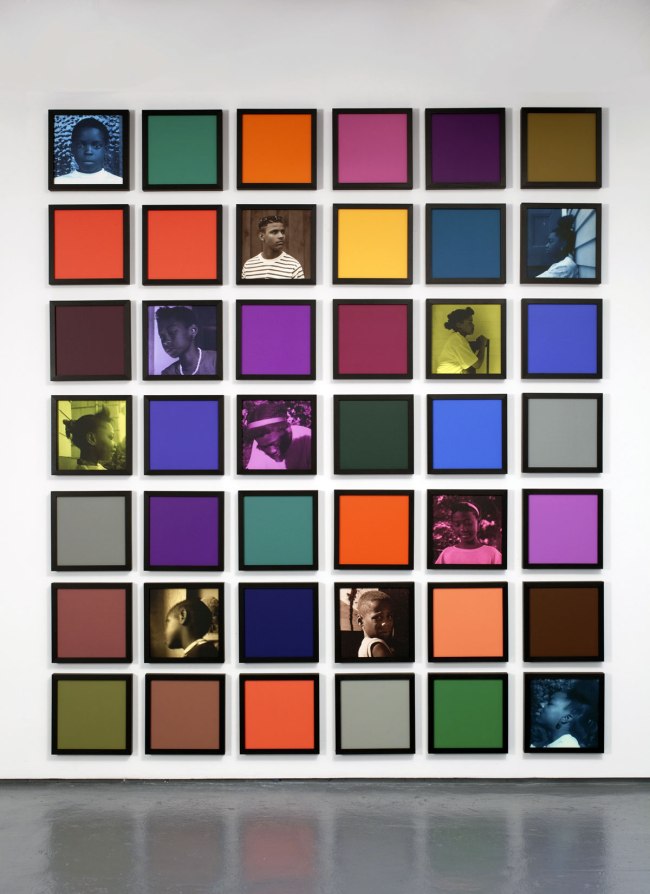

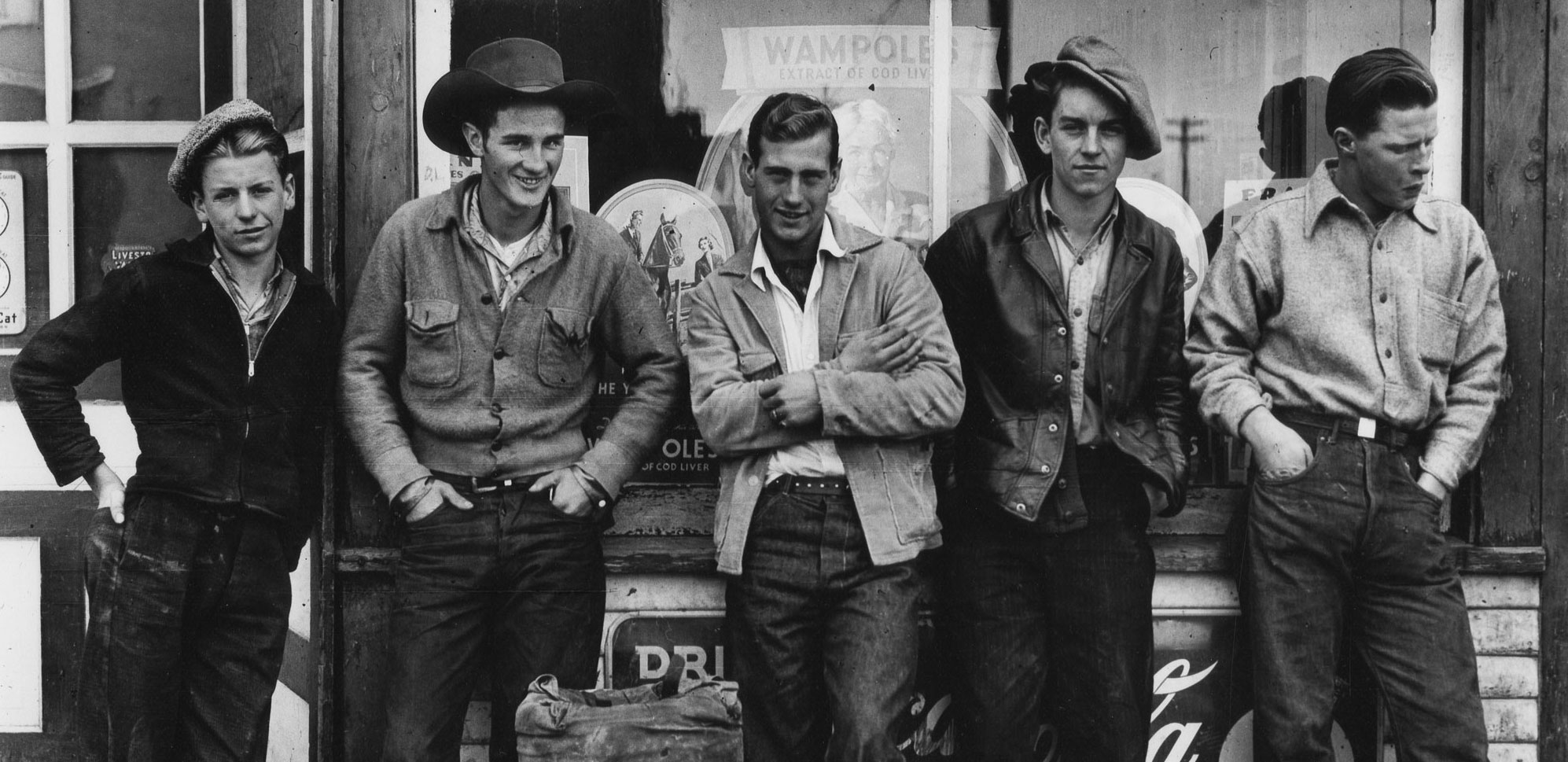

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Columbus, Ohio

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The lives of the classmates – six girls and five boys who graduated from the segregated Plaza School in 1927, in what was then a town of 10,000 people – present a miniature snapshot of African-American aspiration and struggle in the years before Brown v. Board of Education or the civil rights movement.

Parks found Emma Jane Wells in Kansas City, Mo., where she sold clothes door-to-door to supplement her husband’s salary at a paper-bag factory. Peter Thomason lived a few blocks away, working for the post office, one of the best jobs available to black men at the time. But others from the class led much more precarious lives. Parks tracked down Mazel Morgan on the South Side of Chicago, in a transient hotel with her husband, who Parks said robbed him at gunpoint after a photo session. Morgan’s middle-school yearbook description had been ebullient (“Tee hee, tee ho, tee hi, ha hum/Jolly, good-natured, full of fun”), but in 1950 she told Parks, “I’ve felt dead so long that I don’t figure suicide is worthwhile anymore.”

The most promising of the classmates, Donald Beatty, lived in an integrated neighbourhood in Columbus, Ohio, where he had a highly desirable job as a supervisor at a state agency and where Parks’s pictures show him – very much in the vernacular of Life magazine’s Eisenhower-era domestic scenes – happy and secure with his wife and toddler son and a brand-new Buick. But notes made by a Life fact-checker just a year later, when the magazine planned once again to run Parks’s article, recorded a tragedy, blithely and with no explanation: “Aside from the death of their son, nothing much has happened to them.”

Lorraine Madway, curator of Wichita State University’s special collections, said of the Fort Scott story: “There are those moments in an archive when you know you’ve found the gold, and this is one of them. It’s a wonderful example of micro-history. It’s not only that there is so much material written at a specific time in people’s lives, but then there are Parks’s reflections on it later.” …

Besides fact-checking notes, Parks’s own notes and a typewritten draft for what might have been his introduction to the photo spread, there is almost no other documentation surrounding the project, for which Parks shot about 30 rolls of 35-millimetre and medium-format film. And so the question of why it was not published might never be answered. In an essay for the show’s catalog, Ms. Haas speculates that it might have been doomed by its very newsworthiness, as national challenges to school segregation began gathering speed and Life waited – in the end too long – for just the right moment…

Parks carried his own psychic wounds from those years, which profoundly shaped his writing and approach to photography. But his feelings were always bittersweet. Though he lived for many years in New York City, he chose to be buried in his hometown, whose African-American population has declined even more markedly than its overall population. In a 1968 poem about his childhood, he wrote that he would miss “this Kansas land that I was leaving,” one of “wide prairies filled with green and cornstalk,” of the “winding sound of crickets rubbing dampness from wings” and “silver September rain.”

Then he added: “Yes, all this I would miss – /along with the fear, hatred and violence/We blacks had suffered upon this beautiful land.”

Extract from Randy Kennedy. “‘A Long Hungry Look’: Forgotten Gordon Parks Photos Document Segregation,” on The New York Times website, December 24, 2014 [Online] Cited 29/08/2015.

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Railway Station Entrance, Fort Scott, Kansas

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

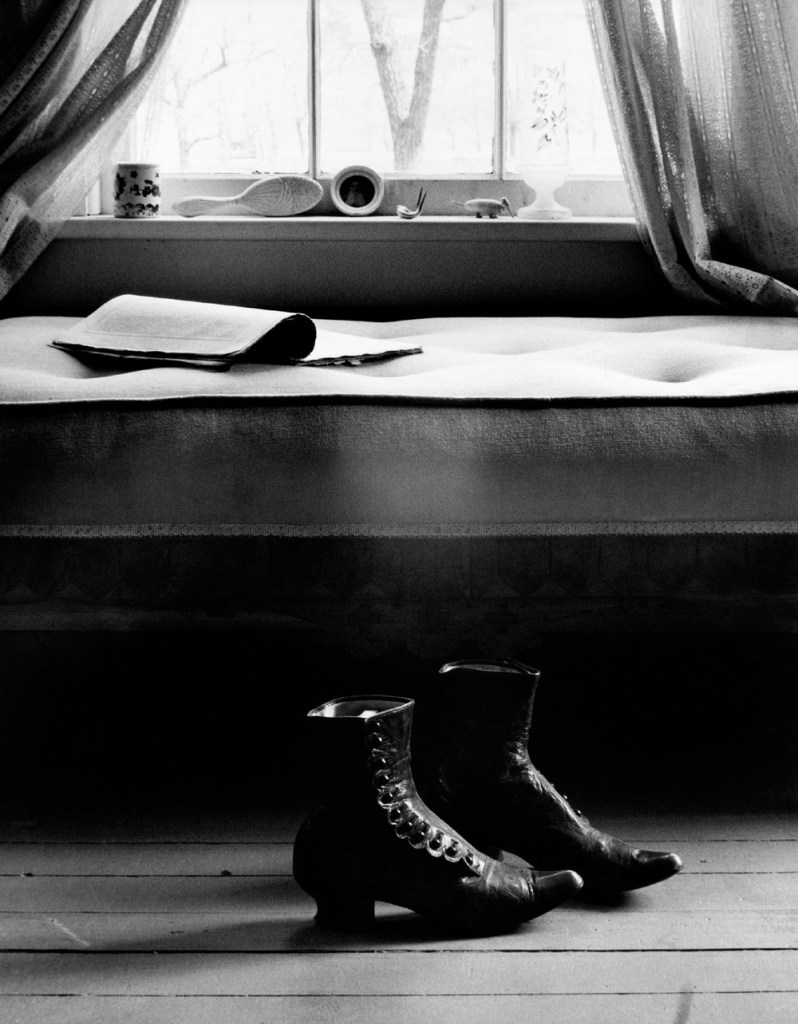

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Shoes, Fort Scott, Kansas

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled (Outside the Liberty Theater)

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Fort Scott, Kansas

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Uncle James Parks, Fort Scott, Kansas

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Mrs. Jefferson, Fort Scott, Kansas

1950

Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Avenue of the Arts

465 Huntington Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Monday 10am – 5pm

Closed Tuesdays

You must be logged in to post a comment.