Exhibition dates: 4th December, 2017 – 18th March, 2018

Curator: Beth Saunders, Assistant Curator in The Met’s Department of Photographs

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Water Lilies

c. 1906, printed 1912

Platinum print

26.1 x 35.2cm (10 1/4 x 13 7/8 in.)

Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933

The critic Charles H. Caffin described this photograph by de Meyer as “a veritable dream of loveliness.” It is one of several floral still life de Meyer made in London around 1906-1909, when he was in close contact with Alvin Langdon Coburn, a fellow photographer and member of the Linked Ring. Both men were inspired by the Belgian writer Maurice Maeterlinck’s 1906 book The Intelligence of Flowers, a mystical musing on the vitality of plant life. De Meyer exhibited several of his flower studies, including this platinum print, at Stieglitz’s influential Photo-Secession galleries in New York in 1909. The image also appeared as a photogravure in an issue of Stieglitz’s art and photography journal Camera Work.

While the “facts of Baron Adolf de Meyer’s early life have been obscured by contradictory accounts from various sources (including himself); he was born in Paris or Germany, spent his childhood in both France and Germany, and entered the international photographic community in 1894-1895,” by circa 1897-1900 he had assumed the title of “Baron.”

“In editions dating from 1898 until 1913, Whitaker’s Peerage stated that de Meyer’s title had been granted in 1897 by Frederick Augustus III of Saxony, though another source states “the photographer inherited it from his grandfather in the 1890s”. Some sources state that no evidence of this nobiliary creation, however, has been found.” (Wikipedia) He then married Donna Olga Caracciolo in 1899, “reputedly the illegitimate daughter of the British king Edward VII, who enjoyed a privileged position within the fashionable international set surrounding the monarch.” The marriage was one of convenience, since he was homosexual and she was bisexual or lesbian, but it was based on a perfect understanding and companionship between two people. As de Meyer observed in an unpublished biography, “Marriage based too much on love and unrestrained passion has rarely a chance to be lasting, whilst perfect understanding and companionship, on the contrary, generally make the most durable union.”

Meyer “gained recognition as a leading figure of Pictorialism and a member of the photographic society known as the Linked Ring Brotherhood in London. Alfred Stieglitz exhibited de Meyer’s work in his Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession and published his images as photogravures in his influential journal Camera Work.” In the early 20th century, he was famed for his photographic portraits and was the preeminent fashion photographer of the day; he was also the first official fashion photographer for the American magazine Vogue, appointed to that position in 1913-1914 until 1921. In 1922 de Meyer accepted an offer to become the Harper’s Bazaar chief photographer in Paris, spending the next 16 years there until he was forced out, his romantic style out of fashion with the modernist taste of the day.

I state these facts only to illustrate the idea that here was a “gay” of dubious lineage (reportedly born in Paris and educated in Dresden, Adolphus Meyer was the son of a German Jewish father and Scottish mother) who rose to associate with and photograph the upper echelons of society. He made it, and he made it good. His photographs of the well to do, film stars and fashion models are undoubtedly beautiful and his control of light magnificent, but they seem to me to be, well… constructed confections. His photographs of the elite and the fashion that they wore possess an ethereal beauty, de Meyer’s shimmering control of light adding to the photographs sense of enacted fantasy played out in the form of timeless classical elegance.

But there is that lingering doubt that these photographs were both his job and his entré (along with the connections and money of his wife) into high society. Look, for example, at the self-portrait of de Meyer in this posting. In the 1900 self-portrait in India when he was 32 and on his honeymoon, we see a coiffed, almost androgynous man who in his pose is as stiff as a board – his body contorted in the strangest way, the right hand gripping the arm of the cane chair, the left splayed and braced, ramrod straight against the seat and the feet crossed in the most unnatural manner. No matter the beautiful light and attractive setting, this is the image that this man wants to portray to the world, this is a man who thinks he has arrived. It is an affectation. And in the portrait of the aristocrat and patron of the avant-garde, Count Etienne de Beaumont (c. 1923, below), this is how he sees himself, as part of that elite. Because in the end, he was. But there is little feeling to any of his portrait work: style, surface, light, form and “the look” reign supreme. Only when he is so overwhelmed by stardust, such as in the brilliant photographs of Josephine Baker and her scintillating personality, does the mask of affection drop away.

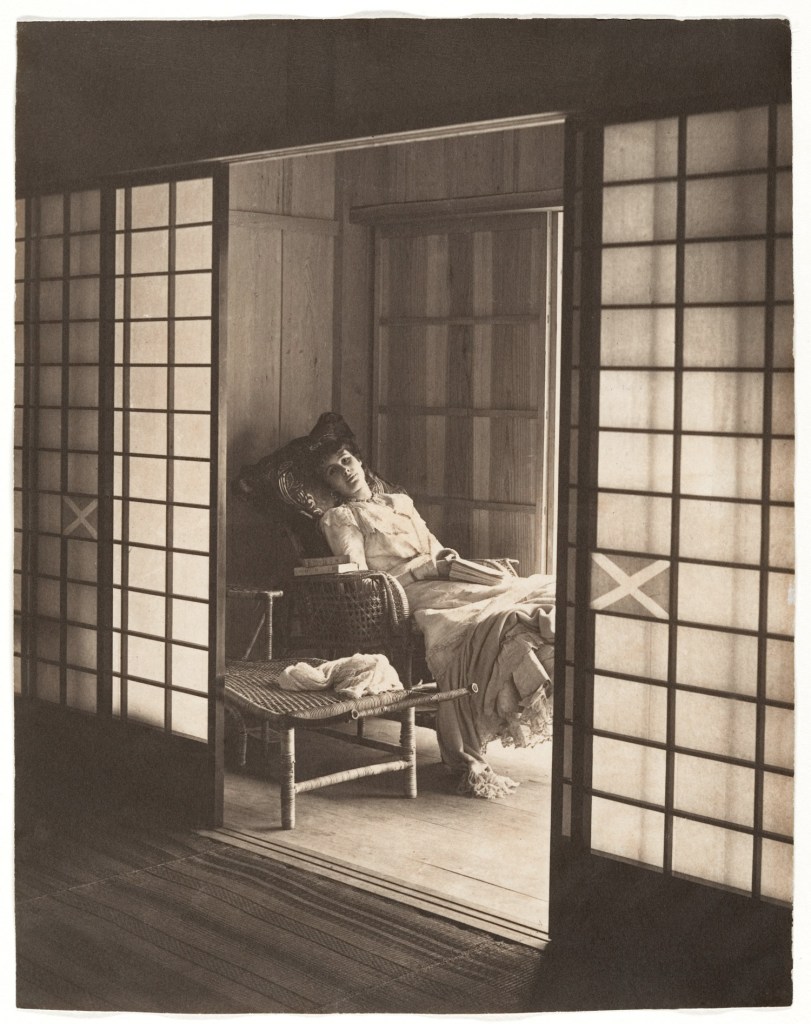

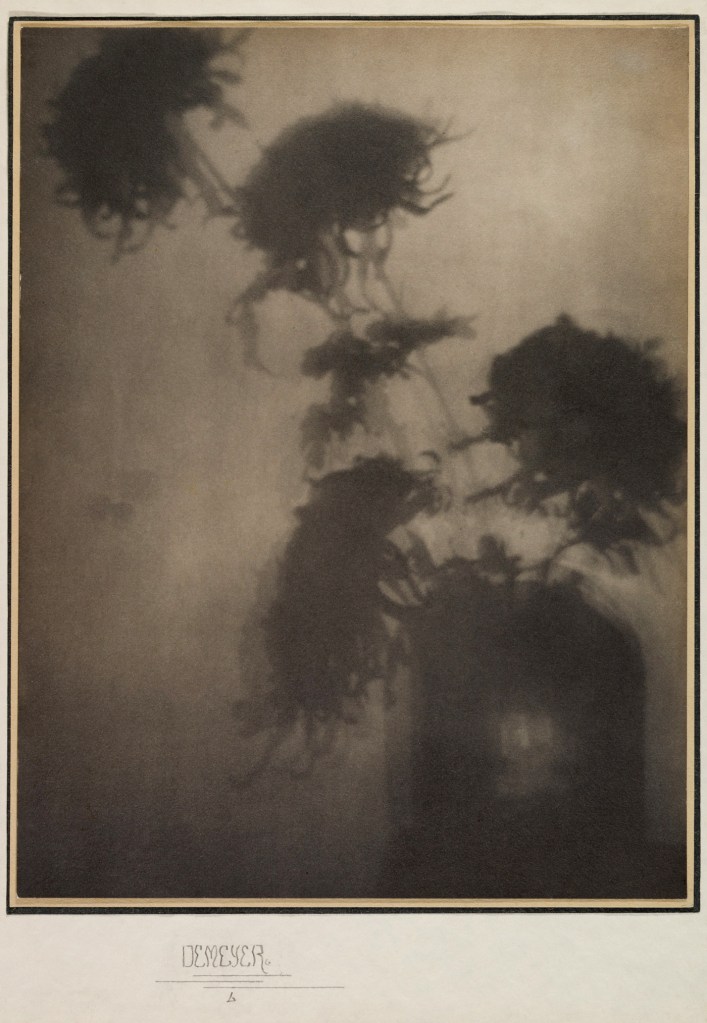

Of more interest to me are his early photographs of Japan where you feel he has some personal investment in the work. The “tactile elegance of his early work” was influenced by “Japanese aesthetics, as well as the influence of the painter James McNeill Whistler, a key figure of the Aesthetic movement.” The photograph View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan (1900, below) is an absolute cracker, as are the Japanese influenced Water Lilies (c. 1906, below) and The Shadows on the Wall (Chrysanthemums) (1906, below). In her January 17, 2018 review of the exhibition “Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs @Met” on the Collector Daily website, Loring Knoblauch states, “While De Meyer’s scenes from Japan, his travel photos of his wife Olga at the Acropolis and in St. Moritz, and his experiments with autochromes in the early 1900s are also included in this eclectic sampler, these rarities aren’t particularly compelling or noteworthy, aside from their supporting role in filling out a broader picture of the artist and his life.” Aren’t particularly compelling! I beg to differ.

I don’t know how people look at photographs and interpret them so differently to how I see them. Perhaps I just feel the music, I see these photographs as if I were taking them, as a personal investment in their previsualisation. While I get very little from de Meyer’s fashion photographs I get a whole lot of pleasure and delight from his transcendent earlier work. I most certainly feel their energy. You only have to look at the reflection of the water lilies. Need I say more.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(Nude Models Posing for a Painting Class)

1890s

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Lunn Gallery, 1980

A member of the “international set” in fin-de-siècle Europe, Baron Adolf de Meyer (1868-1946) was also a pioneering photographer, known for creating works that transformed reality into a beautiful fantasy. Quicksilver Brilliance will be the first museum exhibition devoted to the artist in more than 20 years and the first ever at The Met. Some 40 works, drawn entirely from The Met collection, will demonstrate the impressive breadth of his career.

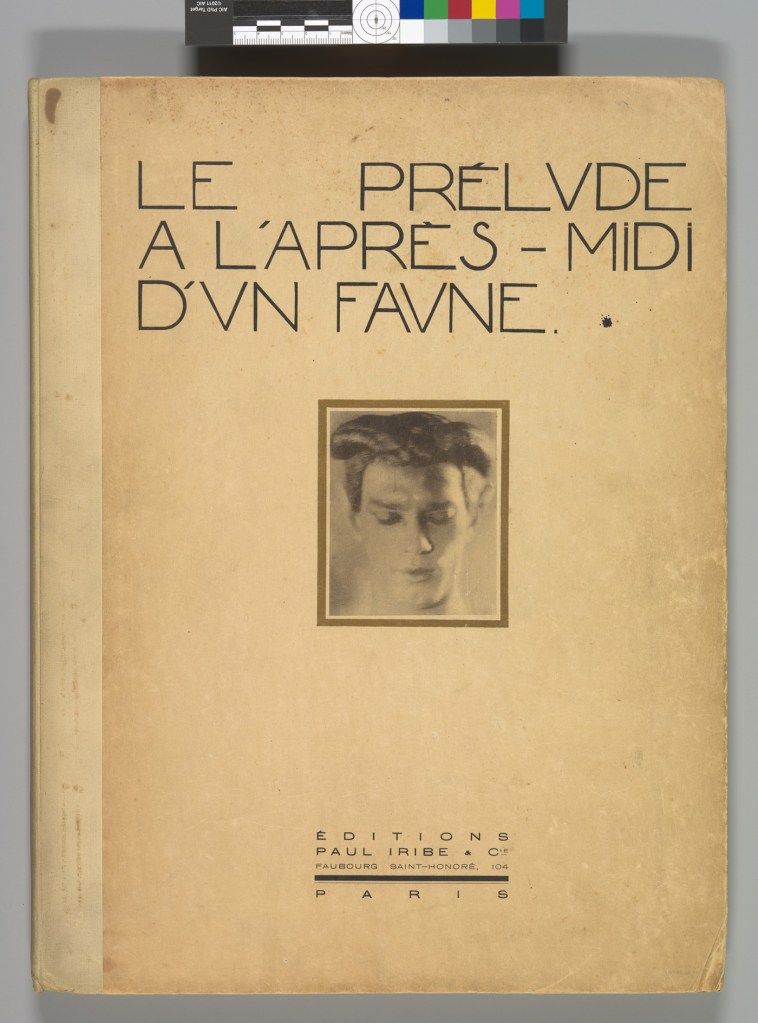

The exhibition will include dazzling portraits of well-known figures of his time: the American socialite Rita de Acosta Lydig; art patron and designer Count Étienne de Beaumont; aristocrat and society hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell; and celebrated entertainer Josephine Baker, among others. A highlight of the presentation will be an exceptional book – one of only seven known copies – documenting Nijinsky’s scandalous 1912 ballet L’Après-midi d’un faune. This rare album represents de Meyer’s great success in capturing the movement and choreography of dance, a breakthrough in the history of photography. Also on view will be the artist’s early snapshots made in Japan, experiments with colour processes, and inventive fashion photographs.

13 platinum prints, 1900, 1906, 1907, 1912, 1917

2 photogravures, 1908, 1912

2 carbon prints, 1900, 1925-1926

1 autochrome in lightbox (facsimile), 1908

4 gelatin silver prints, 1912, 1923, 1925, 1928

1 set of 9 gelatin silver prints (framed together), 1890s-1910

1 trichrome carbro print, 1929

6 collotypes, 1914 (with full collotype book showing 1 image in nearby vitrine, 1914)

4 magazine spreads (in bound volumes of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, 1913, 1919, 1927, in vitrine)

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(Adolf de Meyer Photographing Olga in a Garden)

1890s

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Lunn Gallery, 1980

Like many Pictorialist photographers, de Meyer became interested in the camera through collecting and making snapshots of family and close friends. Olga de Meyer (née Caracciolo) was his companion and muse until her death in 1931. Rumoured to be the illegitimate daughter of the British king Edward VII, she enjoyed a privileged position within the fashionable international set surrounding the monarch. De Meyer made numerous portraits of Olga throughout their famously chic and eccentric life together (in 1916 the couple changed their names to Gayne and Mharah on the advice of an astrologer).

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(Self-Portrait in India)

1900

Platinum print

14.8 x 19.8cm (5 13/16 x 7 13/16 in.)

Gift of Isaac Lagnado, 1995

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(Self-Portrait in India) (detail)

1900

Platinum print

14.8 x 19.8cm (5 13/16 x 7 13/16 in.)

Gift of Isaac Lagnado, 1995

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Amida Buddah, Japan]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Amida Buddah, Japan]' 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-amida-buddah-web.jpg?w=775)

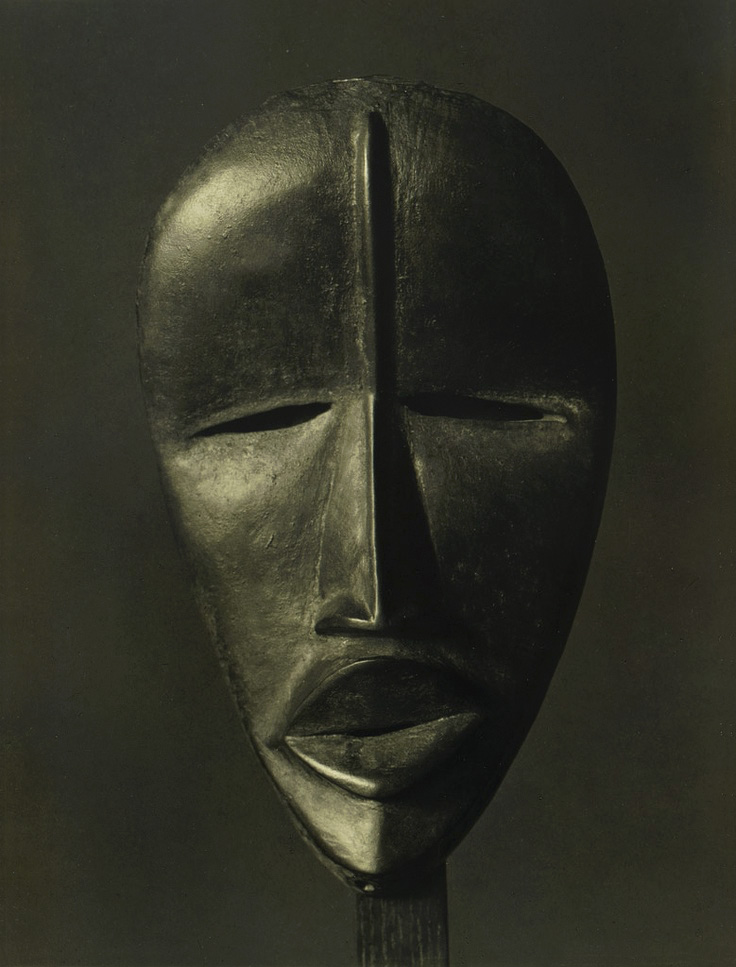

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(Amida Buddah, Japan)

1900

Platinum print

19.2 x 14.3cm (7 9/16 x 5 5/8 in.)

Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Ueno Tōshō-gū, Tokyo, Japan

1900

Platinum print

14.5 x 19.8cm (5 11/16 x 7 13/16 in.)

Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Olga de Meyer, Japan

1900

Platinum print

19.3 x 15.1cm (7 5/8 x 5 15/16 in.)

Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981

Framed by the gridded panels of a sliding screen door, Olga de Meyer pauses from her reading to look languidly at the camera. De Meyer made this affectionate photograph of his new wife while on their honeymoon to Japan. The composition suggests his interest in Japanese aesthetics, as well as the influence of the painter James McNeill Whistler, a key figure of the Aesthetic movement. In its rebellion against Victorian morals, the movement sought inspiration from outside the European tradition. De Meyer’s travels in Japan – as well as China, Ceylon, India, North Africa, Turkey, and Spain – nourished Orientalist fictions, and gave rise to the subjects and compositions of many of his photographs.

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan)

1900

Platinum print

13.8 x 20.3cm (5 7/16 x 8 in.)

Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

The Shadows on the Wall (Chrysanthemums)

1906

Platinum print

34.7 x 26.7cm (13 11/16 x 10 1/2 in.)

Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933

Focusing his camera not on a still life per se, but on its evanescent trace, de Meyer creates a composition that approaches abstraction. He later applied a similar handling of light and shadow to enhance the drama of his fashion photographs. Here, the shadow of a vase of flowers cast onto the wall has the effect of a Japanese lacquered screen.

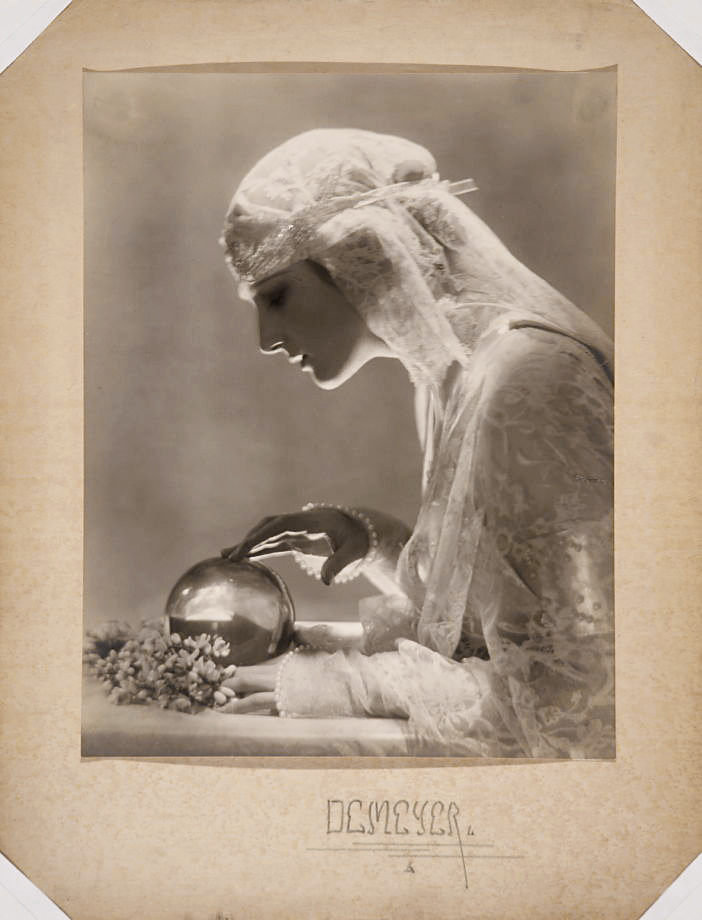

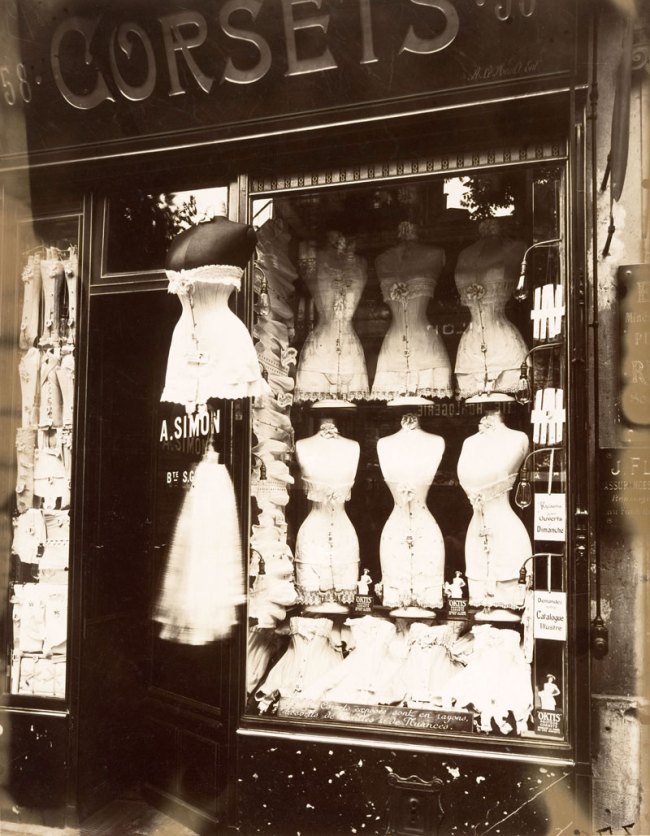

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

The Silver Cap

c. 1909, printed 1912

Gelatin silver print

45.7 x 27.6cm (18 x 10 7/8 in.)

Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933

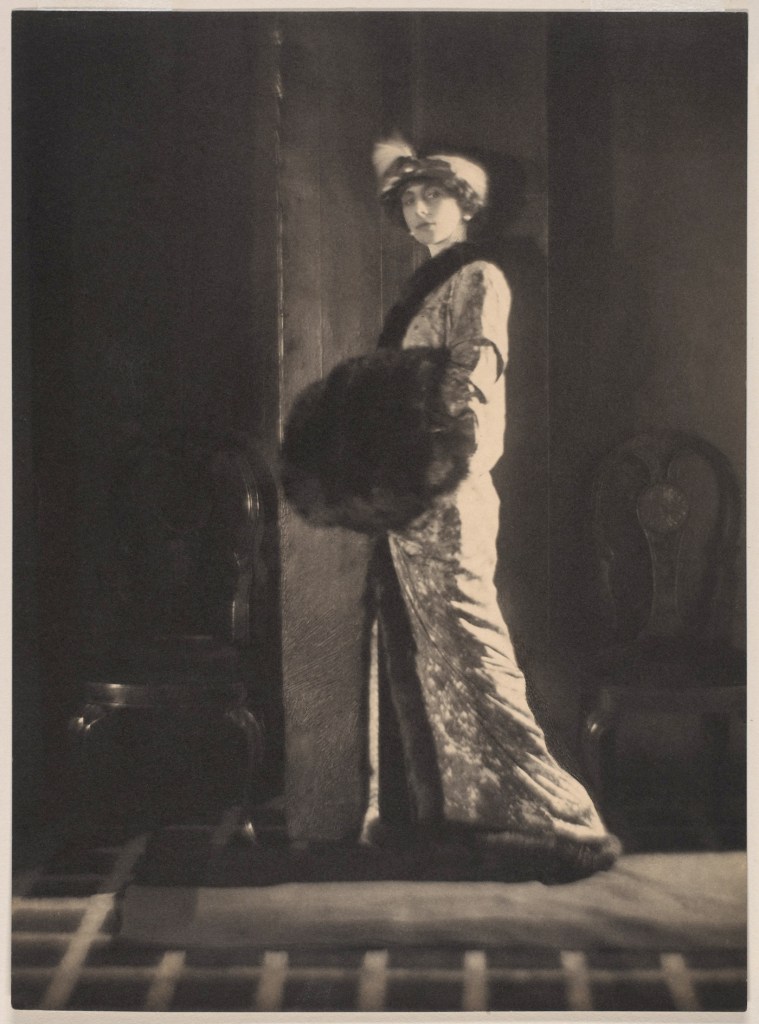

Born in Paris, Baron Adolf de Meyer settled in London in 1896. With his wife, Donna Olga Caraciollo, he joined the elegant set surrounding the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, Olga’s godfather. They entertained lavishly, including concerts and small fancy-dress balls, which gave de Meyer a chance to devise marvellous costumes for Olga. Likely inspired by the de Meyers’ involvement with the Ballets Russes and time spent at their villa on the Bosporus, this dress features Ottoman elements such as the full skirt and decorative trimmings yet conforms to the Western fitted waistline – a fine example of the 1910s fashion trend of exoticism.

A member of the “international set” in fin-de-siècle Europe, Baron Adolf de Meyer (1868-1946) was also a pioneering art, portrait, and fashion photographer, known for creating images that transformed reality into a beautiful fantasy. The “quicksilver brilliance” that characterised de Meyer’s art led fellow photographer Cecil Beaton to dub him the “Debussy of the Camera.” Opening December 4 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs will be the first museum exhibition devoted to the artist in more than 20 years and the first ever at The Met. Some 40 works, drawn entirely from The Met collection, will reveal the impressive breadth of his career.

The exhibition will include dazzling portraits of well-known figures of his time: the American socialite Rita de Acosta Lydig; art patron and designer Count Étienne de Beaumont; aristocrat and society hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell; and celebrated entertainer Josephine Baker, among others. A highlight of the presentation will be an exceptional book – one of only seven known copies – documenting Nijinsky’s scandalous 1912 ballet L’Après-Midi d’un Faune. This rare album represents de Meyer’s great success in capturing the choreography of dance, a breakthrough in the history of photography. Also on view will be the artist’s early snapshots made in Japan, experiments with colour processes, and inventive fashion photographs.

Born in Paris and educated in Germany, de Meyer was of obscure aristocratic German-Jewish and Scottish ancestry. He and his wife, Olga Caracciolo, goddaughter of Edward VII, were at the centre of London’s café society.

After starting in photography as an amateur, de Meyer gained recognition as a leading figure of Pictorialism and a member of the photographic society known as the Linked Ring Brotherhood in London. Alfred Stieglitz exhibited de Meyer’s work in his Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession and published his images as photogravures in his influential journal Camera Work. At the outbreak of World War I, de Meyer settled in the United States and applied his distinctive pictorial style to fashion imagery, helping to define the genre during the interwar period.

The exhibition was organised by Beth Saunders, Assistant Curator in The Met’s Department of Photographs.

Press release from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Tamara Karsavina

c. 1908

Autochrome

9 x 11.9cm (3.5 x 4.6 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Harriette and Noel Levine Gift, 2005

De Meyer enthusiastically embraced the autochrome process at its inception in 1907, writing to Stieglitz the following year that his work in black and white no longer satisfied him. An ardent admirer of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, de Meyer created this image of Tamara Karasavina (1885-1978), a leading dancer and partner to Nijinksy, during one of the company’s visits to England. The photographer chose a background of bellflowers and arranged a brocaded shawl to enhance the exotic elegance of the dancer.

The autochrome, which retains in its minuscule prisms the particular luminosity of a misty English day in summer, was thought to represent the Marchioness of Ripon in her garden at Coombe, Surrey. An early patron of de Meyer, Lady Ripon was also a staunch supporter of Diaghilev, bringing the Ballets Russes to London in 1911. She frequently entertained Karasavina and Nijinsky at Coombe, where they danced for Alexandra, the queen consort, and de Meyer dedicated to her his album documenting Nijinsky’s production of L’Après-midi d’un faune. A companion image to this autochrome is in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Lady Ottoline Morrell]' c. 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Lady Ottoline Morrell]' c. 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-lady-ottoline-morrell-web.jpg?w=764)

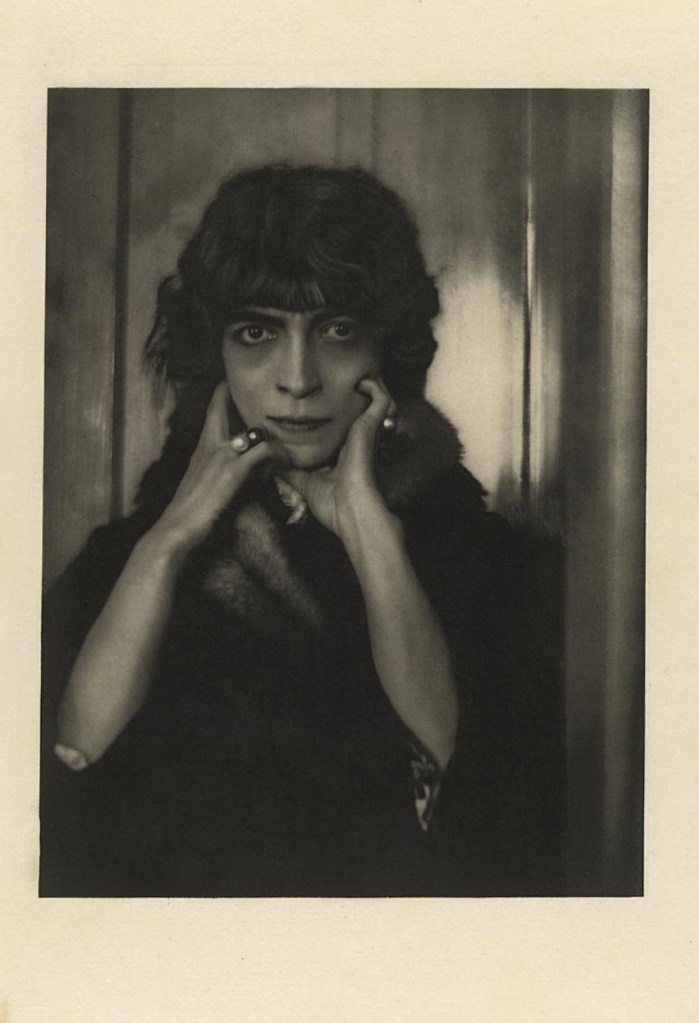

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(Lady Ottoline Morrell)

c. 1912

Platinum print

23.5 x 17.4cm (9 1/4 x 6 7/8 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Harriette and Noel Levine Gift, 2005

Adolph de Meyer’s portrait of Lady Ottoline Morrell, eccentric hostess to Bloomsbury, is a stunning summation of the character of this aristocratic lady who aspired to live “on the same plane as poetry and as music.” Rebelling against the narrow values of her class, Lady Ottoline Cavendish Bentinck (1873-1938) married Philip Morrell, a lawyer and liberal Member of Parliament, and surrounded herself in London and on their estate at Garsington with a large circle of friends, including Bertrand Russell, W. B. Yeats, D. H. Lawrence, T. S. Eliot, Katherine Mansfield, Lytton Strachey, Virginia Woolf, Aldous Huxley, and E. M. Forster. Tall, wearing fantastic, scented, vaguely Elizabethan clothes, Lady Ottoline made an unforgettable impression. With her dyed red hair, patrician nose, and jutting jaw, she could look, according to Lord David Cecil, at one and the same moment beautiful and grotesque. Henry James saw her as “some gorgeous heraldic creature – a Gryphon perhaps or a Dragon Volant.”

De Meyer made several portraits of Lady Ottoline. None went as far as this one in conjuring up the sitter’s flamboyant persona, capturing, through dramatic lighting and Pre-Raphaelite design, her untamed, baroque quality. “Her long, pale face, that she carried lifted up, somewhat in the Rossetti fashion, seemed almost drugged, as if a strange mass of thoughts coiled in the darkness within her.” D. H. Lawrence’s inspired description of the character based on Lady Ottoline in “Women in Love” finds a vivid counterpart in the photographer’s art.

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

The Cup

c. 1910

Gum bichromate print

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Olga de Meyer

c. 1912

Platinum print

22.4 x 16.4cm (8 13/16 x 6 7/16 in.)

Gift of Paul F. Walter, 2009

Renowned for her beauty and style, de Meyer’s spouse was, in a sense, his first fashion model. Here, dramatic backlighting emphasises her sinuous form, enshrouded in shimmering fabric and fur. Her gaze conveys a haughty bemusement that elevates the tableau from costume play to regal sophistication.

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(Dance Study)

c. 1912

Platinum print

32.7 x 43.5cm (12 7/8 x 17 1/8 in.)

Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933

De Meyer photographed the dancer Nijinsky and other members of Diaghilev’s troupe when “L’Après-midi d’un Faun” was presented in Paris in 1912. It has been suggested that this photograph, the only nude by de Meyer, has some connection to the Russian ballet, but if so, it remains mysterious. The image vibrates with an uneasy erotic tension, a product of the figure’s exposed torso, startled body language, and disguised identity.

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Le Prelude à l’Après-Midi d’un Faune

1914

Collotypes

Album: 15 1/4 x 11 5/8 inches

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

In 1912 de Meyer made a remarkable series of photographs related to the Ballets Russes production L’après-midi d’un faune (Afternoon of a Faun). The avant-garde dance was choreographed by famed Russian performer Vaslav Nijinsky, set to a score by Claude Debussy, and inspired by a poem by Symbolist writer Stéphane Mallarmé. It follows a young faun distracted from his flute-playing by bathing nymphs who seduce and taunt him, leaving behind a scarf with which he allays his desire. When the ballet premiered in Paris on May 29, 1912, the overtly sexual climactic scene and unconventional choreography scandalised audiences. Nijinsky based the angular movements and frieze-like staging on Greek vase paintings, but Ballets Russes founder Sergei Diaghilev also likened them to Cubism.

Thirty of de Meyer’s photographs of the ballet were published as collotypes (photomechanical ink prints) in a 1914 edition of one thousand luxurious handcrafted books. Only seven copies are known today. Using alternately complex and fragmentary compositions, de Meyer’s images generate a rhythm of gesture and form. The thin Japanese papers offer a tactile echo of the diaphanous costumes (designed by artist Léon Bakst), and the heavily manipulated negatives enshroud the angular figures in a dreamlike haze. An object of desire, the book itself embodies the spirit of Nijinsky’s ballet.

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-portrait-of-vaslav-nijinski-1912-web.jpg?w=785)

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l’Après-Midi d’un Faune]

1912

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1914 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1914](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-nijinsky-plate-from-le-prelude-acc80-laprecc80s-midi-dun-faune-web.jpg?w=637)

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Nijinsky (Plate from Le Prelude à l’Après-Midi d’un Faune)

1914

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(Image from Prelude à l’Après-Midi d’un faune)

1914

Platinum print

4 3/16 × 7 1/16 in. (10.6 × 17.9cm)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Mrs. Walter Annenberg and The Annenberg Foundation Gift, 2005

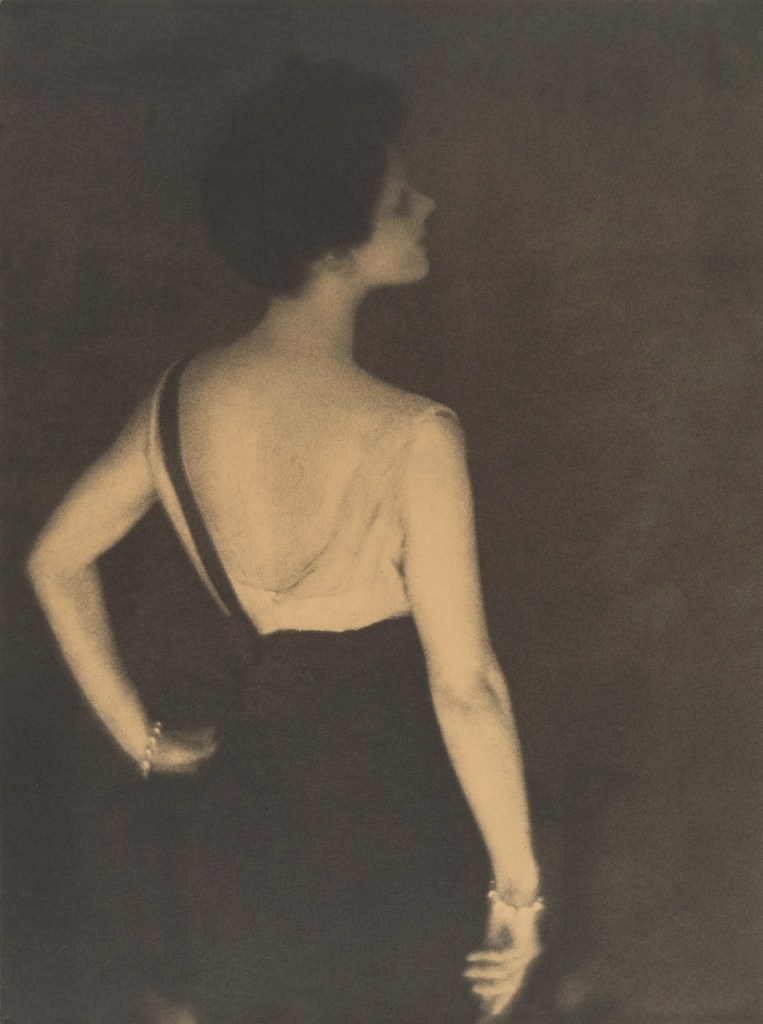

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Rita de Acosta Lydig

1917

Platinum print

41.5 x 30.9cm (16 5/16 x 12 3/16 in.)

Gift of Mercedes de Acosta, 1952

De Meyer’s portrait of the socialite, art patron, “shoe queen,” and suffragette Rita de Acosta Lydig is striking in its simplicity of tone and contour. The image, which appeared in Vogue in 1917, resonates with the classical elegance epitomised in the paintings of society portraitists John Singer Sargent and Giovanni Boldini, who also depicted this so-called alabaster lady.

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Portrait of the Marchesa Casati

1912

Plate from Camera Work No. XL August 1912

Luisa, Marchesa Casati Stampa di Soncino (23 January 1881 – 1 June 1957), also known as Luisa Casati, was an Italian heiress, muse, and patroness of the arts in early 20th-century Europe. …

A celebrity, the Marchesa was famed for eccentricities that dominated and delighted European society for nearly three decades. The beautiful and extravagant hostess to the Ballets Russes was something of a legend among her contemporaries. She astonished society by parading with a pair of leashed cheetahs and wearing live snakes as jewellery.

Text from the Wikipedia website

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Study for Vogue [Jan 1-1918, Betty Lee, Vogue, page 41]' 1918-1921 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Study for Vogue [Jan 1-1918, Betty Lee, Vogue, page 41]' 1918-1921](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-study-for-vogue-web.jpg?w=803)

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Study for Vogue (Jan 1 – 1918, Betty Lee, Vogue, page 41)

1918-1921

Gelatin silver print

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Dolores

1921

Gelatin silver print

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Etienne de Beaumont [Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956)]' c. 1923 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Etienne de Beaumont [Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956)]' c. 1923](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-etienne-de-beaumont-web.jpg?w=808)

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Etienne de Beaumont (Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956))

c. 1923

Gelatin silver print

23.7 x 18.6cm (9 5/16 x 7 5/16 in.)

Gift of Paul F. Walter, 2009

An aristocrat and patron of the avant-garde, Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956) cuts a dashing figure here, posed in one of the grand salons of his hôtel (grand townhouse) in Paris’s rue Masseran. The count hosted a series of legendary masquerade balls at his residence during the interwar period, attended by avant-garde artists such as Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso, and Man Ray. De Meyer described these parties, which he and Olga often attended, as “fêtes of unsurpassed magnificence” in a 1923 article for Harper’s Bazaar.

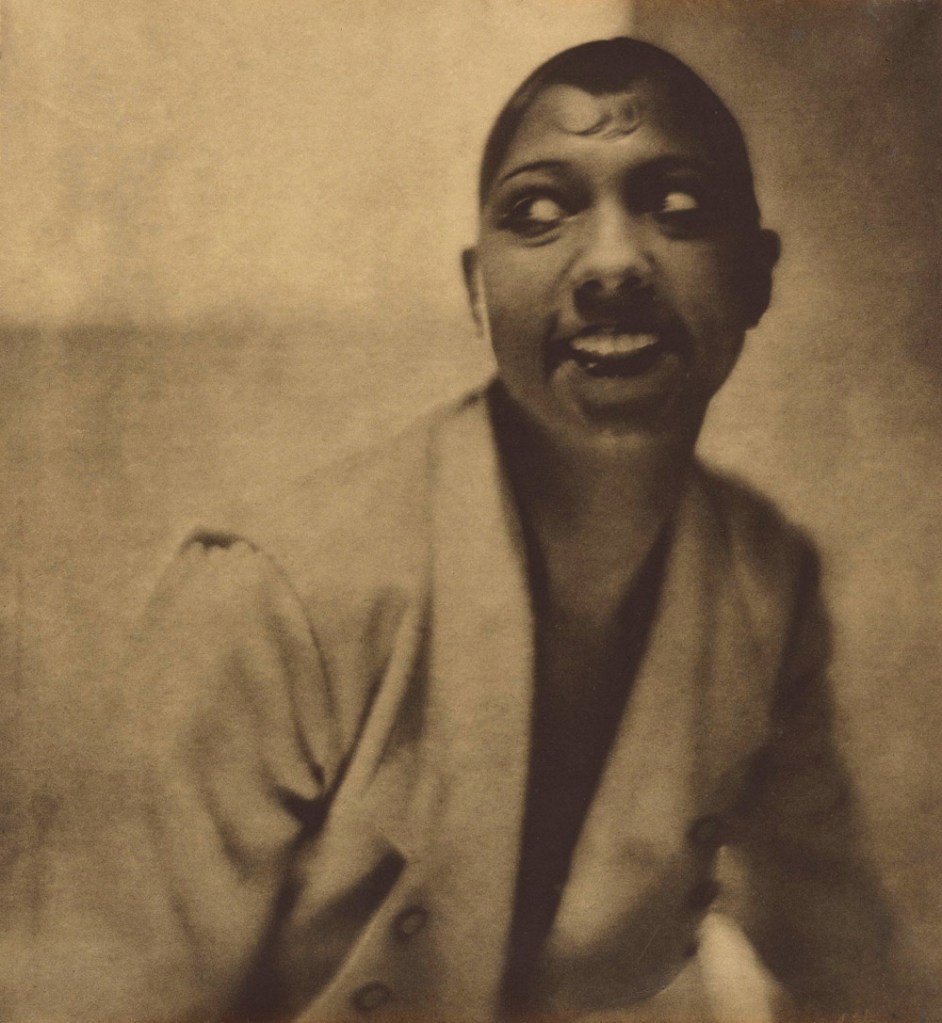

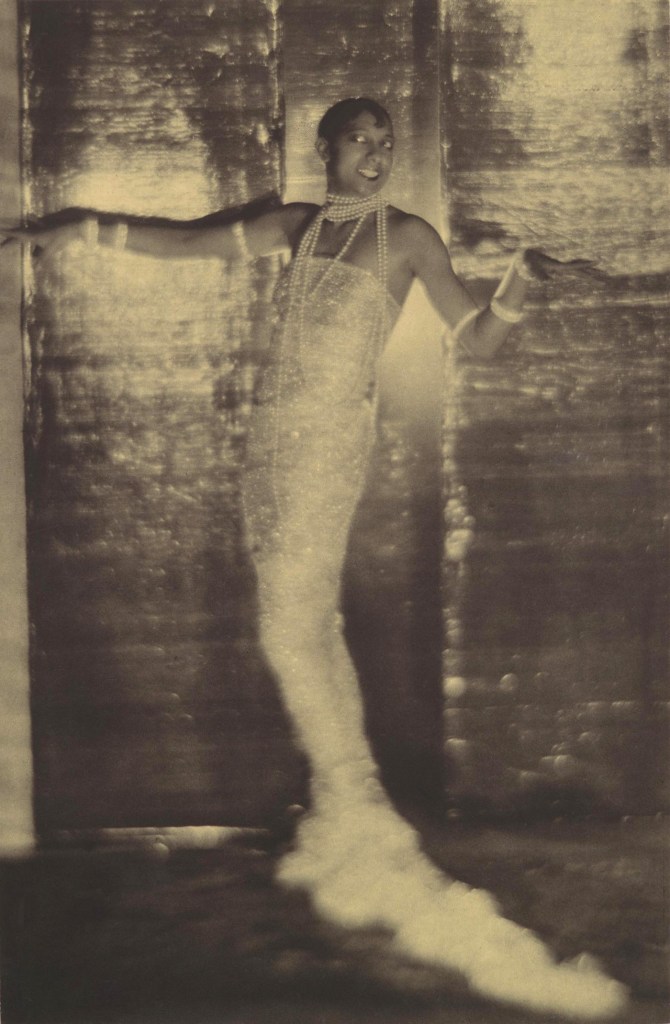

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Portrait of Josephine Baker

1925

Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Josephine Baker

1925-1926

Direct carbon print

45.2 x 29.5cm (17 13/16 x 11 5/8 in.)

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

The Saint Louis, Missouri-born Josephine Baker arrived in Paris in 1925 and quickly made a sensation as part of the all-black Revue Nègre, a musical entertainment that capitalised on the French craze for American Jazz. Famously donning a banana skirt for her danse sauvage, Baker crafted performances that astutely deployed the stereotypes white Europeans associated with blackness, recouping them as instruments of her own empowerment and success. Baker shines amid the glittering backdrop and soft focus of de Meyer’s photograph, creating an iconic image of stardom.

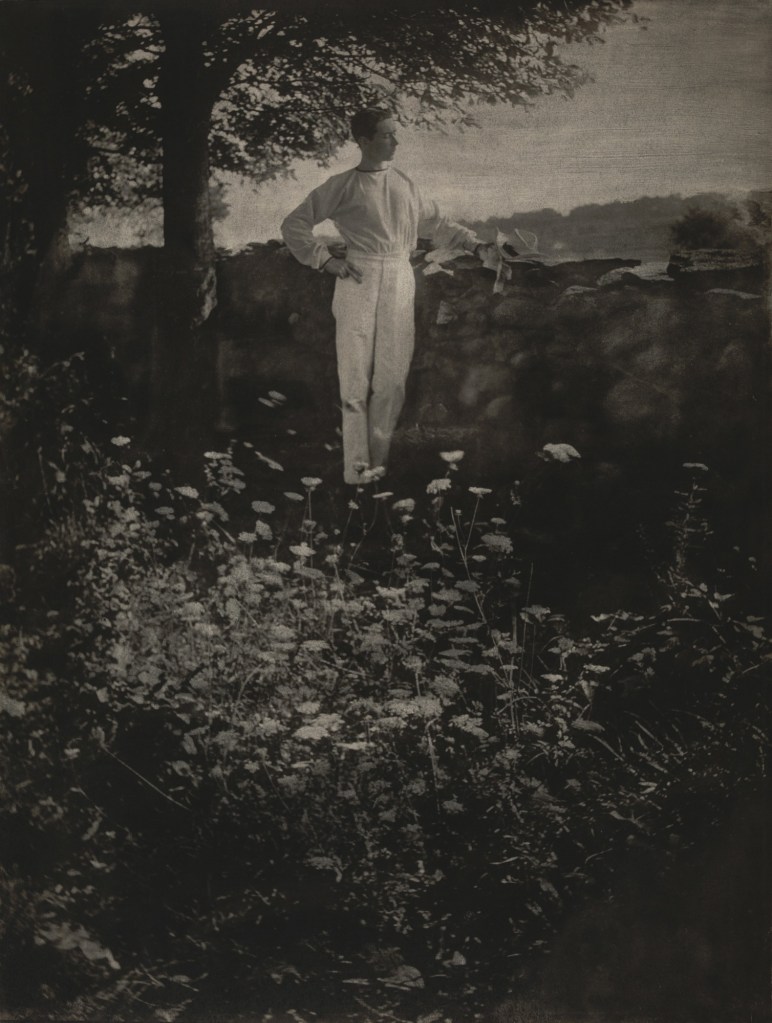

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

Baron Adolf de Meyer

1903

Platinum print

13 3/8 x 10″ (34 x 25.5cm)

Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Miss Mina Turner

Taken in the same photo session as the photograph below.

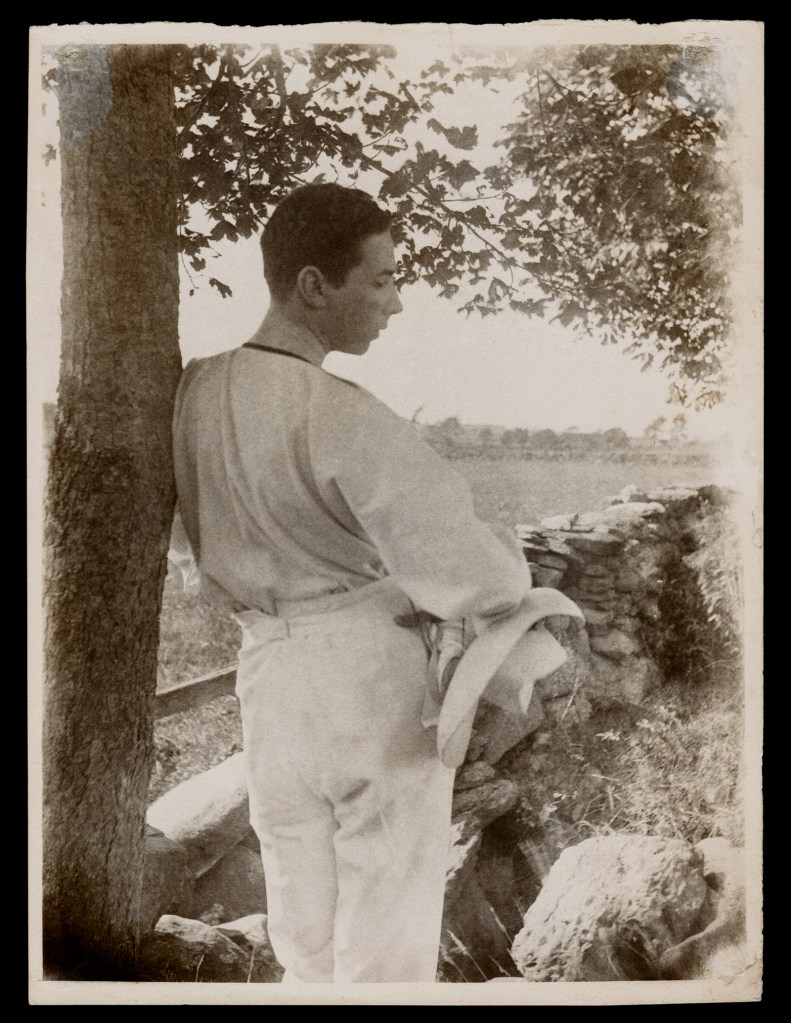

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

Baron Adolph de Meyer (Leaning Against Tree)

1903

Platinum photograph

8.5 x 6.5 in.

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) 'A Mexican [Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868-1946 Los Angeles, California)]' 1905 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) 'A Mexican [Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868-1946 Los Angeles, California)]' 1905](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/sears-adolf-de-meyer-web.jpg?w=808)

Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935)

A Mexican (Adolf de Meyer (American born France, Paris 1868 – 1946 Los Angeles, California))

1905

Platinum print

24.2 x 18.7cm (9 1/2 x 7 3/8 in.)

Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933

With his brow arched beneath a tilted hat and hand elegantly grasping a stark white scarf, de Meyer dons a mysterious alter ego. Like de Meyer, Sears was involved with the two major groups devoted to art photography: the Photo-Secession and the Linked Ring Brotherhood. The two artists may have met through a mutual friend, the photographer F. Holland Day, who included their work in his exhibition “New School of American Photography,” on view in London in 1900 and Paris the following year. The title for this portrait follows a Photo-Secession tradition of withholding the sitter’s name when exhibiting publicly.

Sarah Choate Sears (1858-1935) was an American art collector, art patron, cultural entrepreneur, artist and photographer. …

About 1890 she began exploring photography, and soon she was participating in local salons. She joined the Boston Camera Club in 1892, and her beautiful portraits and still lifes attracted the attention of fellow Boston photographer F. Holland Day. Soon her work was gaining international attention. …

In 1899 she was given a one-woman show at the Boston Camera Club, and in 1900 she had several prints in Frances Benjamin Johnson’s famous exhibition in Paris. … In 1907, two of her photographs were published in Camera Work, but by that time she had lost much of her interest in photography.

Text from the Wikipedia website

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Thursday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Closed Wednesday

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Nude Models Posing for a Painting Class]' 1890s from the exhibition 'Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dec 2017 - March 2018 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Nude Models Posing for a Painting Class]' 1890s from the exhibition 'Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dec 2017 - March 2018](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-nude-models-posing-for-a-painting-class-web.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Adolf de Meyer Photographing Olga in a Garden]' 1890s Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Adolf de Meyer Photographing Olga in a Garden]' 1890s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-photographing-olga-in-a-garden-web.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-self-portrait-in-india-web.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 (detail Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-self-portrait-in-india-detail.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan]' 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-view-through-the-window-of-a-garden-web.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-dance-study-web.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Image from "Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un faune"]' 1914 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Image from "Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un faune"]' 1914](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-image-from-prelude-web.jpg)

![Morton Schamberg (American, 1881–1918) '[View of Rooftops]' 1917 Morton Schamberg (American, 1881–1918) '[View of Rooftops]' 1917](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/schamberg-view-of-rooftops.jpg?w=815)

You must be logged in to post a comment.