Exhibition dates: 8th February – 11th May 2014

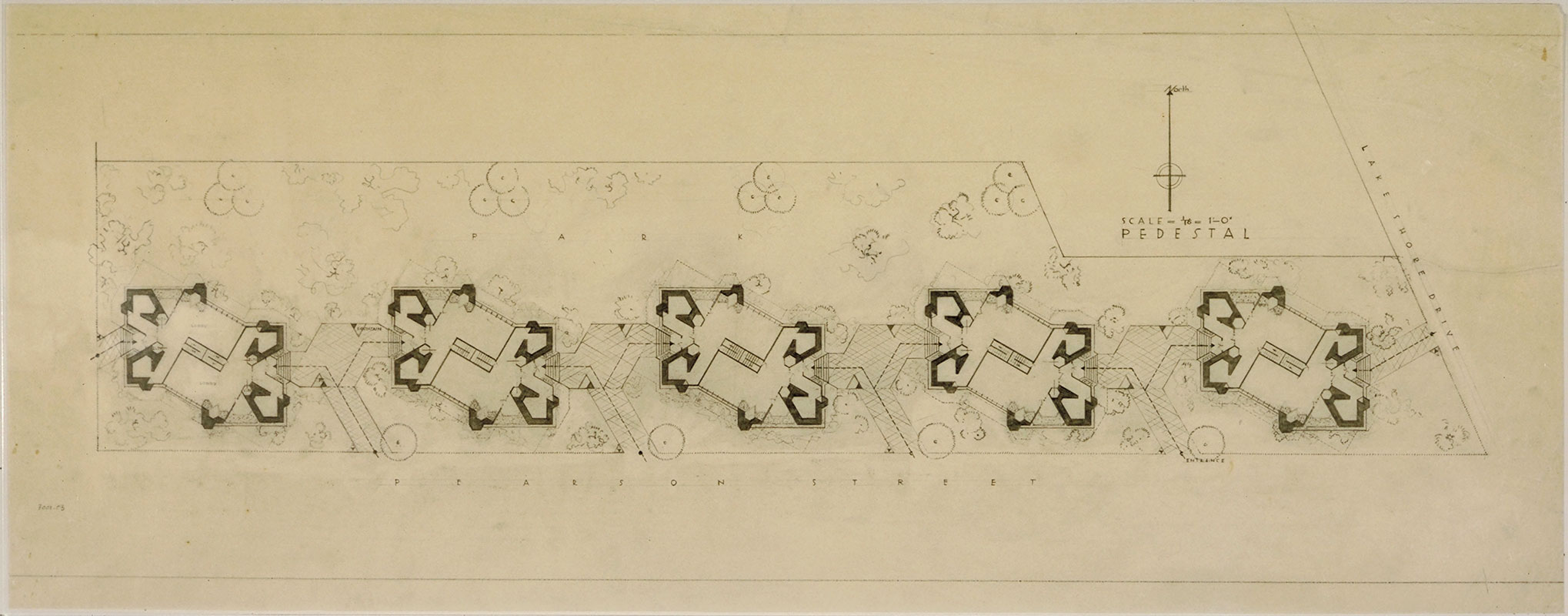

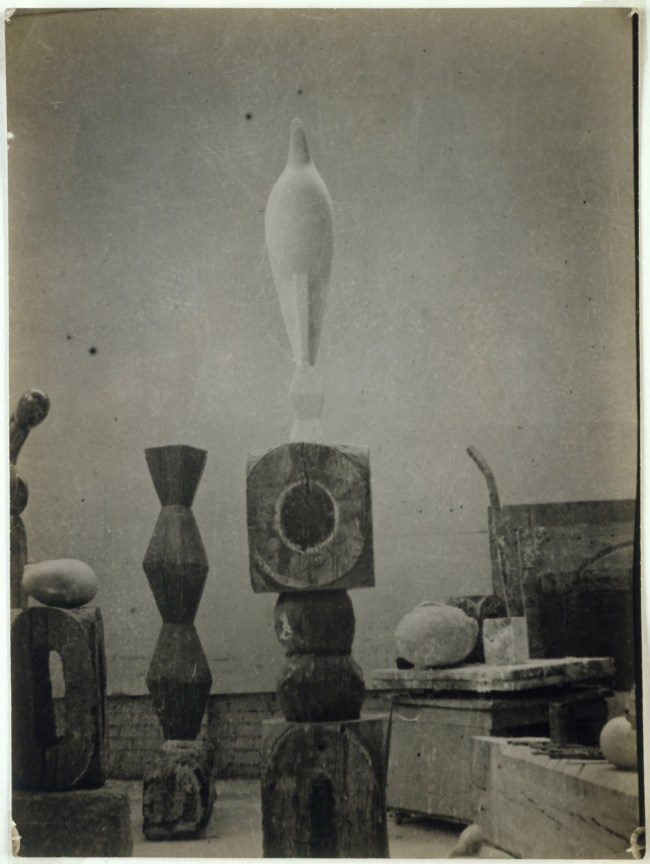

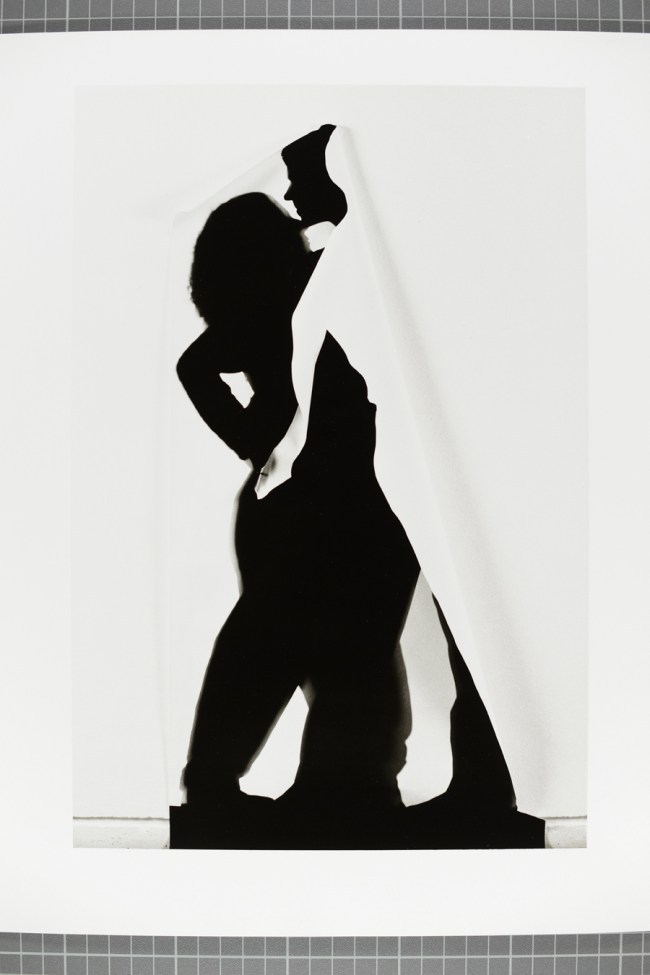

Installation photograph of the exhibition Brancusi, Rosso, Man Ray – Framing Sculpture

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2014

Foto / Photo: Gert-Jan de Rooij, Amsterdam

What a magnificent exhibition. We all know Brancusi and Man Ray but it is the work of Medardo Rosso that surprises and delights here, an artist I admit I knew nothing about before this posting. What a revelation, both his sculptures and photographs. I must try and do a whole posting just on his photographs!

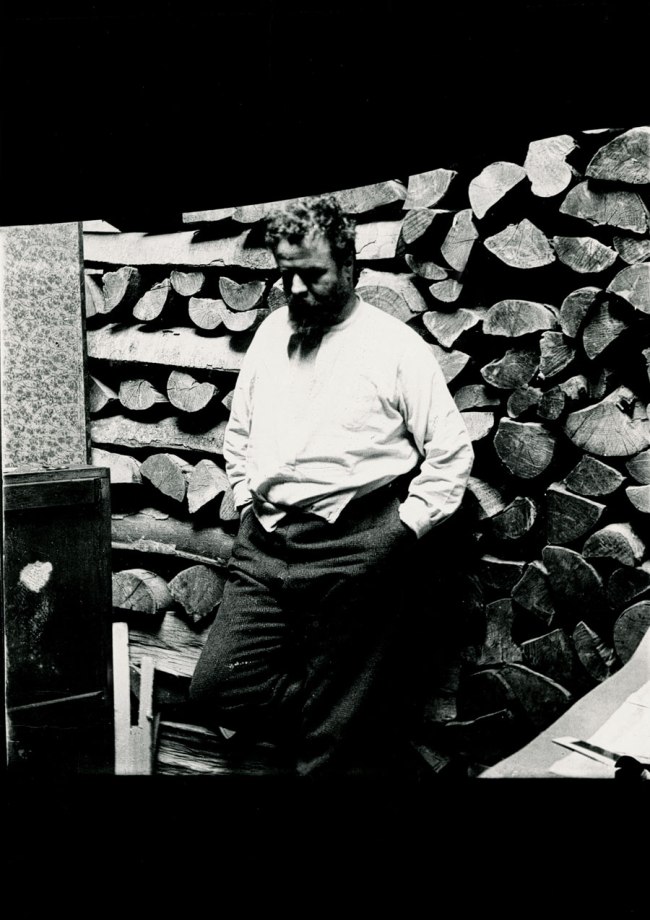

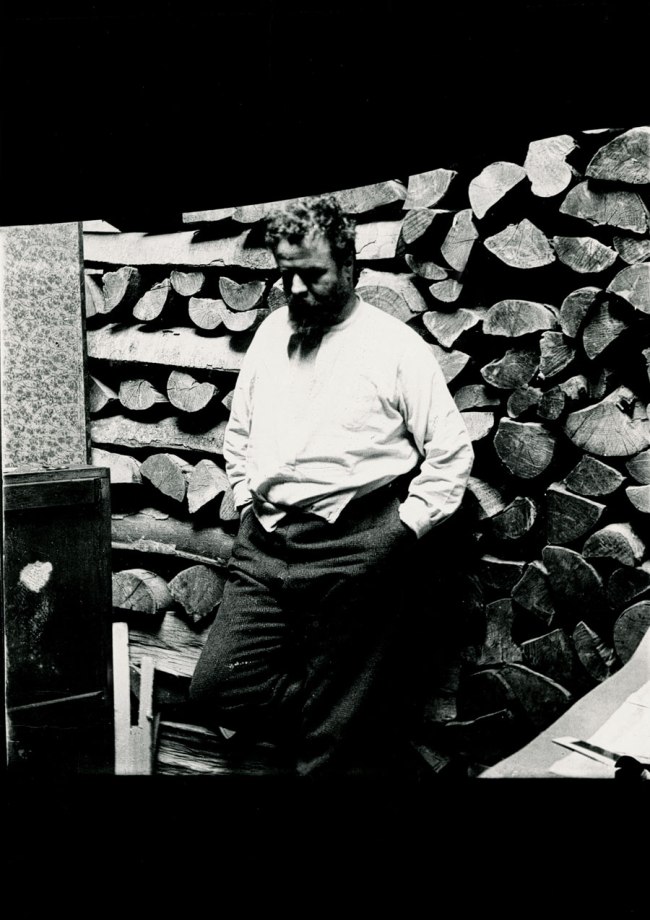

The two self-portraits of the artists in the studio are telling… Rosso, pensive, brooding, with a stack of chopped wood surrounding him, face wreathed in shadow, head titled slightly down and hands stuffed in pockets; Brancusi, seated on a plinth, legs crossed, swarthy arms folded replete with large hands, staring directly at the camera and surrounded by his work. Rosso in malleable darkness, Brancusi in towering light. The photographs reflect their respective personalities and inform the art which represents them.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the image for a larger version of the art.

Alessio delli Castelli considers the Italian sculptor’s photographic legacy.

“Medardo Rosso was born in Turin in 1858 and died in Milan 1928. However, he spent most of his life away from Italy, in Paris especially, from where he travelled to all the major European capitals. It was in Paris that, towards the close of the 19th century, he emerged alongside Auguste Rodin as a serious contender for the title of father of modern sculpture. Yet it was Rodin who achieved universal recognition. In spite of Rosso’s influence on sculptors such as Constantin Brancusi – whose Sleeping Muse (1909-10), with its radically abstracted features of a female head, is strongly reminiscent of Rosso’s Madame X (1896) – he was long held hostage by a provincial criticism which saw his practice confined, chronologically, thematically and formally, to the 19th century. Although it is true that Rosso only created two original sculptural works in the 20th century, to claim that he was no longer a practicing artist would be to overlook the variations he made of his sculptures, and the copies from antiquity. More importantly, it would be to dismiss his photographic work of that period merely as images of sculptures that already existed. This would mean ignoring the fact that his photography showed all the signs of rigorous artistic investigation – and was not, as critics in the 20th century often declared, indicative of either an accident that injured his leg and made him weak or a more general creative block.

It is only in recent years that Rosso’s photographs have acquired the status of art objects in and of themselves…”

Installation photographs of the exhibition Brancusi, Rosso, Man Ray – Framing Sculpture

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2014

Foto / Photos: Gert-Jan de Rooij, Amsterdam

In mythology, Leda is a girl who is seduced by Zeus who turns her into a swan. In the Brancusi sculpture, Leda (foreground, above) is that metamorphosis. The swan is an animal whose body is often associated with a hybrid identity between male and female. His neck is close to a phallic shape while her body has feminine attributes. The bird and woman, male and female mingle in the same sculptural movement. This transfiguration is reflected in the complex forms of sculpture, asymmetrical contours, the offset top shape intersecting with the lower form, giving rise to multiple passages and perceptions.

In 1932, Brancusi sculpture adds a large polished steel disc which suggests the presence of water and Leda is reflected in the mirror which changes its shape. Modifications qu’accentuera still provide a motor and a ball bearing arranged in the circular plate. Within the workshop, the body of Leda is in a state of constant metamorphosis. The shimmer of light on the surface of polished bronze sculpture blends with its reflection in the steel circle and absorbs its environment. Leda becomes a pure luminous presence. Weight and lightness, balance and imbalance are the same event within a continuous time duration in the sculptures of Constantin Brancusi.

Translated from the French on the Constantin Brancusi web page of the Centre Pompidou website [Online] Cited 05/05/2014 no longer available online

Installation photograph of the exhibition Brancusi, Rosso, Man Ray – Framing Sculpture

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2014

Foto / Photo: Gert-Jan de Rooij, Amsterdam

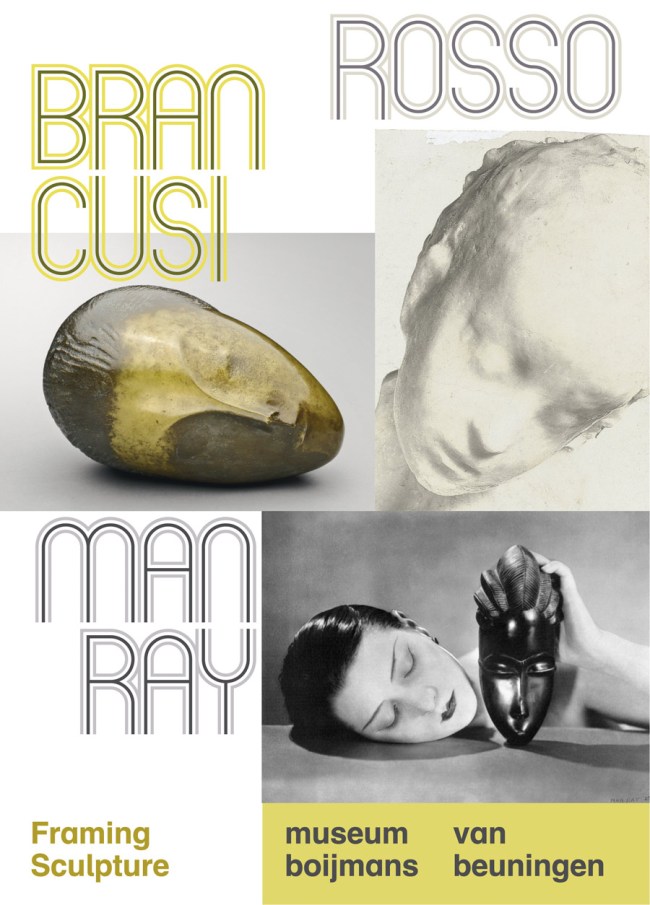

In the spring of 2014 Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen brings together works from all over the world by three artists who were decisive for the development of modern art. This is the first exhibition to combine sculptures by Brancusi, Rosso and Man Ray together with their photographs, affording a unique insight into the artists’ working methods.

Masterpieces that have rarely or never been seen in the Netherlands will be lent by important museums such as the Centre Pompidou, MoMA and Tate. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen will show more than 40 sculptures and hundred photographs by Constantin Brancusi (Hobita 1876 – Paris 1957), Medardo Rosso (Turin 1858 – Milan 1928) and Man Ray (Philadelphia 1890 – Paris 1976). The exhibition will feature sculptures such as Brancusi’s Princesse X (1915-1916) and Rosso’s Ecce Puer (1906) alongside works by Man Ray from the museum’s collection, including the sculpture L’Énigme d’Isidore Ducasse (1920 / 1971). Presenting the sculptures together with the artists’ photographs of their sculptures reveals their often-surprising perspectives on their own works.

Framing Sculpture

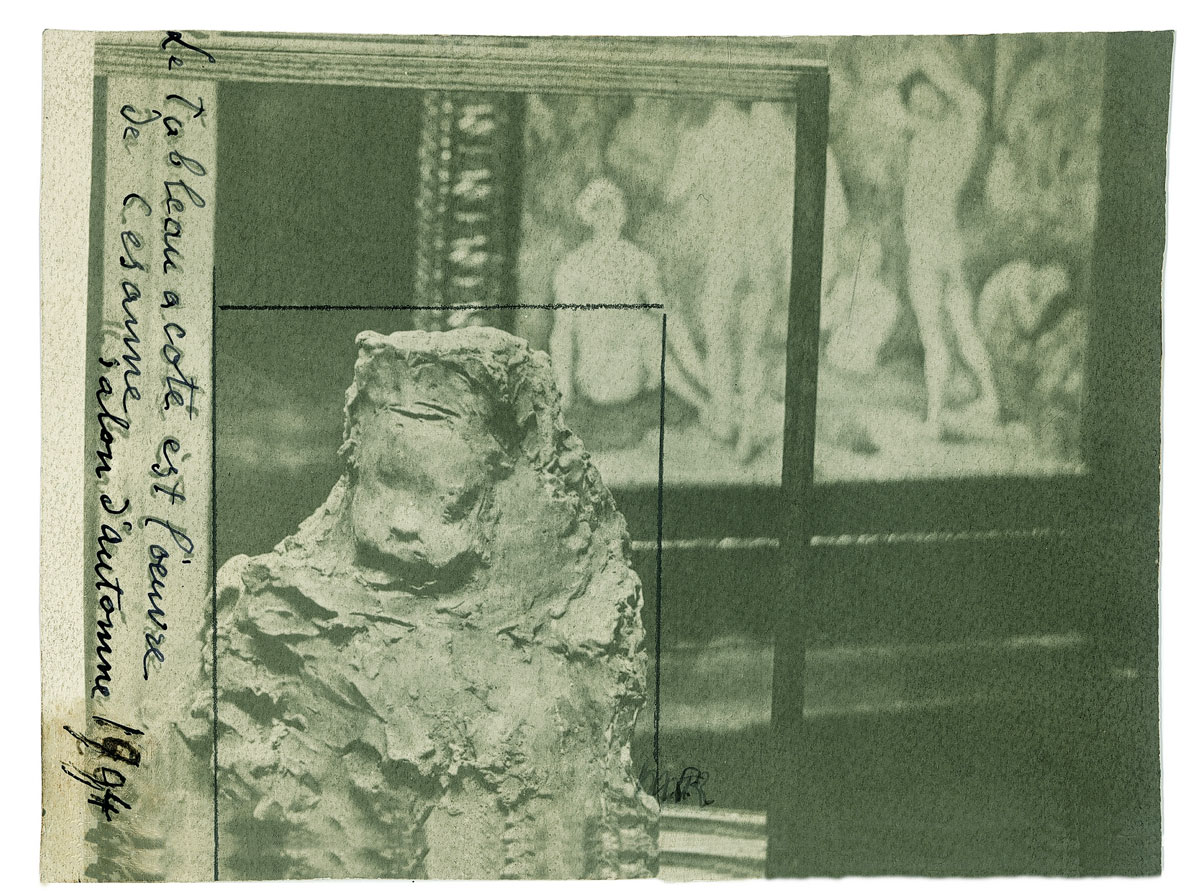

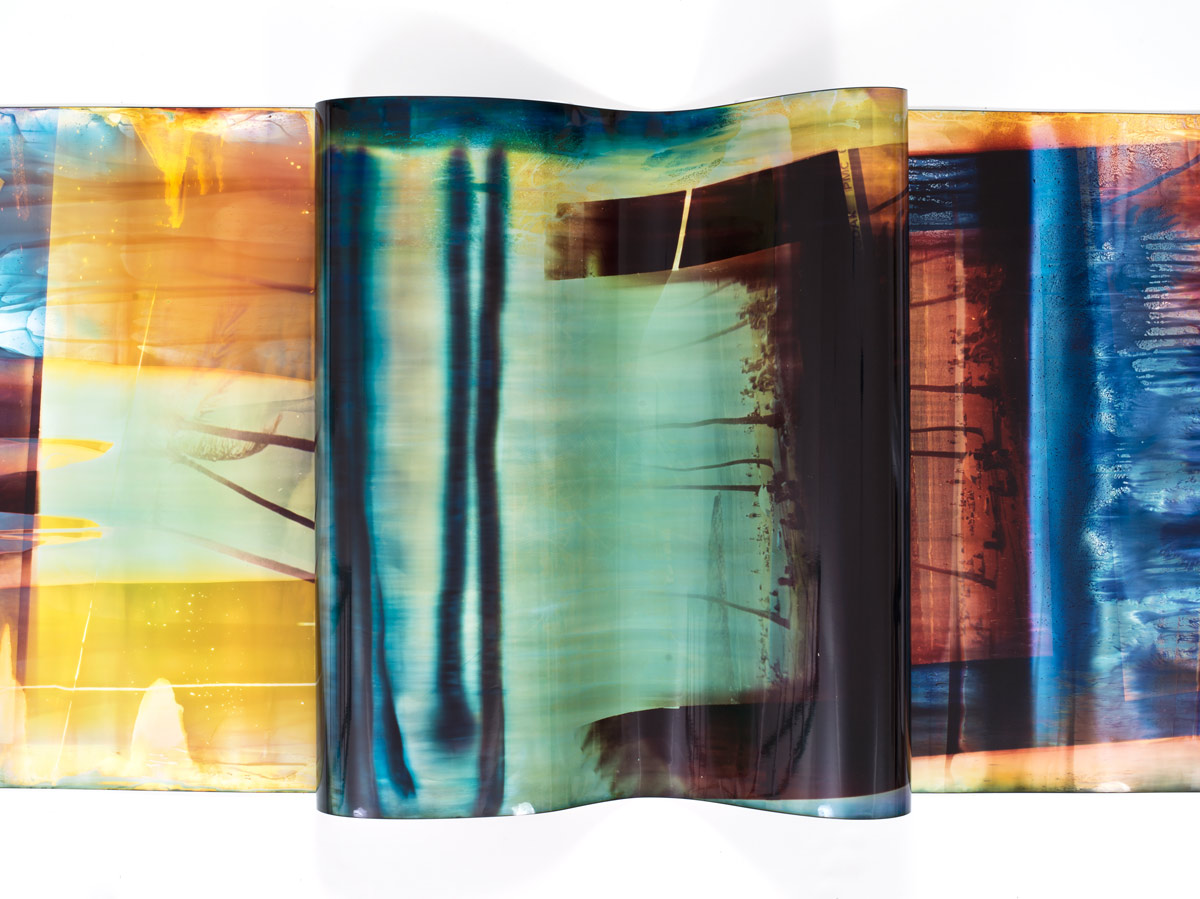

Brancusi, Rosso and Man Ray employed photography not so much as a means of recording their work. The photographs show how they interpreted their sculptures and how they wanted them to be seen by others. Brancusi is considered the father of modern sculpture with his highly simplified sculptures of people and animals. In his photographs he experimented with light and reflection so that his sculptures absorb their environment and appear to come to life. Rosso is the artist who introduced impressionism in sculpture. The indistinct contours of his apparently quickly modelled figures in plaster and wax make them appear to fuse with their surroundings. Rosso cut up the soft-focus photographs of his work, made them into collages and reworked them with ink so that the sculptures appear even flatter and more contourless. Man Ray is best known as a photographer but was also a painter and sculptor. His choice of materials was unconventional: he combined existing objects to create new works, comparable to the ‘readymades’ of his friend Marcel Duchamp. Man Ray’s experimental use of photography led him to make photographs without the use of a camera. He made these so-called ‘rayographs’ by placing objects directly on photographic paper and exposing them briefly to light, leaving behind a ghostly impression.

Press release from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

L’Énigme d’Isidore Ducasse (The Riddle of Isidore Ducasse)

1920 (1971)

Iron, textile, rope, cardboard

45.4 x 60 x 24cm

Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

© Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2013.

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

L’Énigme d’Isidore Ducasse (The Riddle of Isidore Ducasse)

1920 (1975)

Gelatin silver print

47.5 x 59cm

Courtesy Fondazione Marconi, Milan

© Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2013

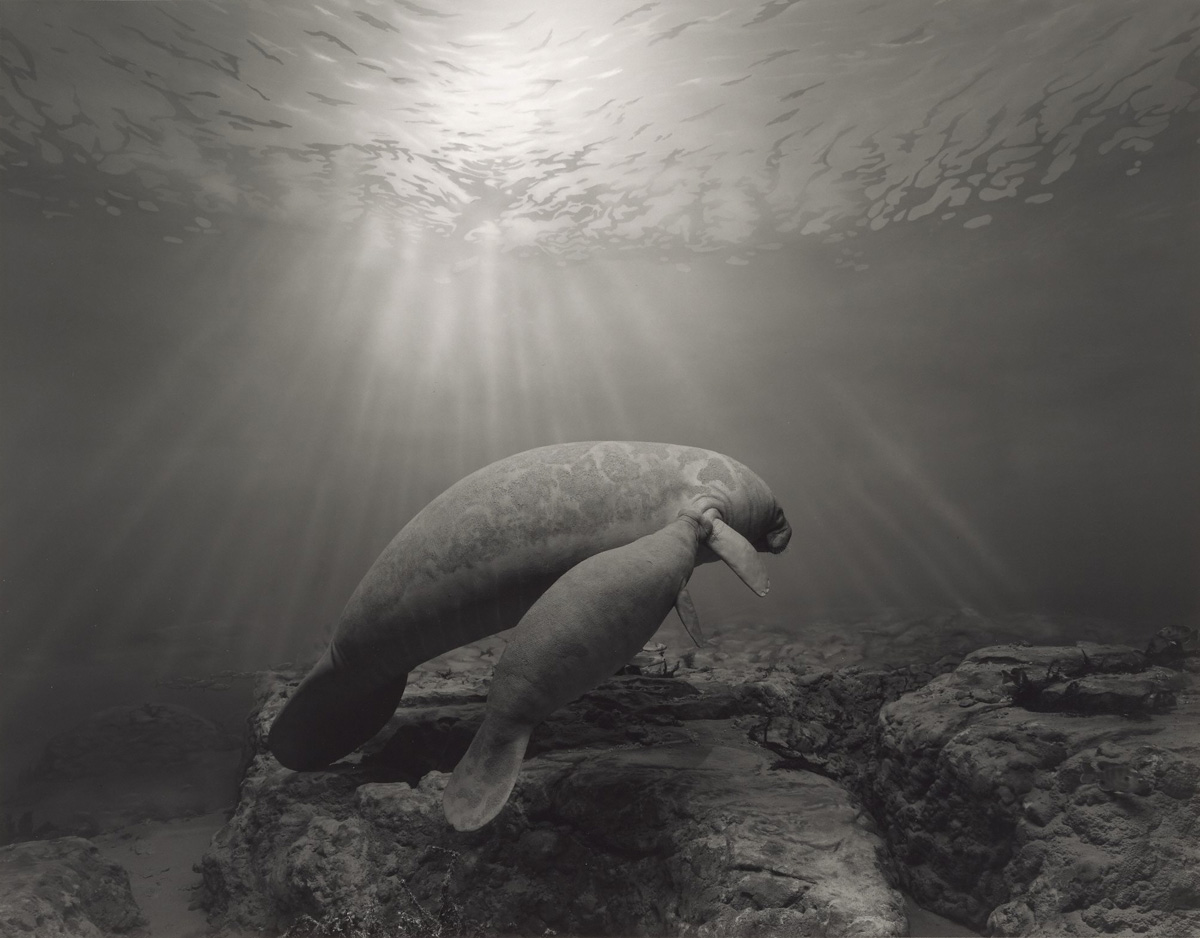

Medardo Rosso (Italian, 1858-1928)

Enfant à la Bouchée de pain (Child in the soup kitchen)

1897 (1892-1893)

Wax over plaster

46 x 49 x 37cm

Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome

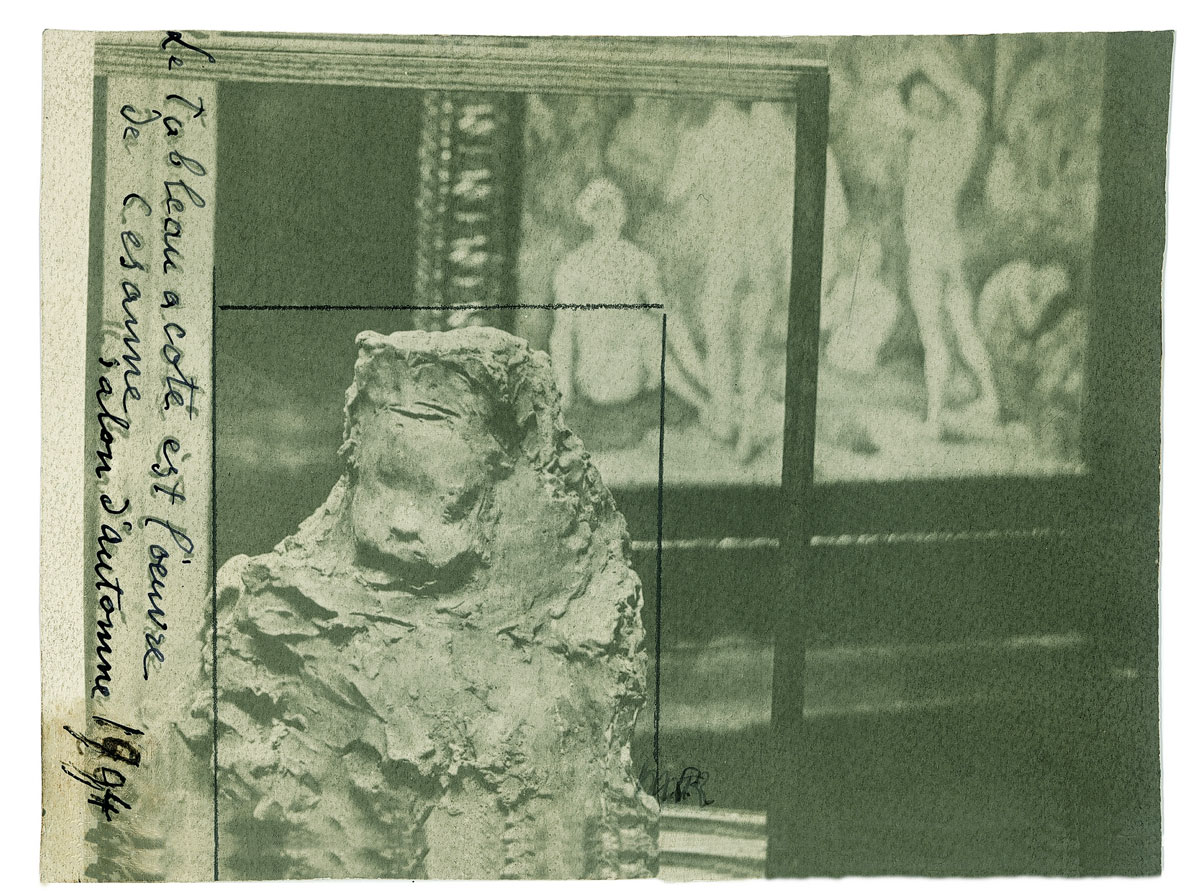

Medardo Rosso (Italian, 1858-1928)

Enfant à la Bouchée de pain in the Cézanne room at the Salon d’Automne

1904

Felatin silver print

12.3 x 15.5cm

Private collection

The Italian sculptor Medardo Rosso (1858-1928) is the oldest and most traditional of the three artists. He stands in the Impressionist tradition of French sculptor August Rodin. Rosso has made many portraits of children, which he adored. They were one of his favourite subjects. Rosso kept working on the same pieces throughout his career, making changes to their titles, shapes or materials. Sometimes he combined materials or poured another substance over the original. A work of plaster then became a wax sculpture. Other times he made two different versions of the same image, using different materials…

Rosso… used his camera to present his art in the way he preferred. By taking pictures and displaying them next to the actual sculptures he could show the audience what was, in his opinion, the right angle to look at his piece. Of course, everyone is free to walk around the sculpture, but the photographs show what the artist had in mind when he created it. Many times he would cut up his pictures, tear away corners or colour them with ink. This way he even reinterpreted his interpretations. Together the sculptures, photographs and collages give a complete picture of the work by Medardo Rosso. Never before have there been so many of his works on display in the Netherlands.

Text by Evita Bookelmann on the Kunstpedia website [Online] Cited 05/05/2014. No longer available online

Constantin Brancusi (Romanian, 1876-1957)

Tête d’enfant endormi (Head of a Sleeping Child)

1906-1907

Plaster, coloured dark brown

10.8 x 13.6 x 15.2cm

Private collection

A previously unknown sculpture by Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) can be seen in Brancusi, Rosso, Man Ray – Framing Sculpture, the exhibition opening at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen on Saturday. The museum is especially delighted by the arrival of Tête d’enfant endormie (Head of a Sleeping Child, 1906-07). This early sculpture is an important key work in Brancusi’s development of his famous ‘ovoid’.

The exhibition, which features more than forty sculptures by Constantin Brancusi, Medardo Rosso and Man Ray and a hundred vintage photographs taken by them, runs in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen for three months from 8 February. The plaster sculpture was purchased at a sale by a French private collector. Leading expert Friedrich Teja Bach has recently confirmed that it is a version of the ‘head of a sleeping child’. Curators Francesco Stocchi and Peter van der Coelen remarked, “It is unusual for a previously unknown work by Brancusi to turn up at a sale. Works by Brancusi are rare and almost all of them are in prominent museum collections like those of the Centre Pompidou, the Tate and MoMA.”

The Road to Abstraction

The child’s head with natural features is in the tradition of the contemporary Impressionists Auguste Rodin and Medardo Rosso. At the same time, this early work is a starting point in Brancusi’s journey towards a more abstract style, which culminated in an entirely smooth oval form, devoid of any facial features. This process can also be seen in the photographs taken by Brancusi himself, in which he pictured Tête d’enfant endormie in his studio with Le Nouveau-Ne II, a work he made ten years later. The exhibition in Rotterdam examines the artistic practices and development of Brancusi, Rosso and Man Ray by showing the sculptures alongside the photographs they took of them.

Painted Bronze

Brancusi’s oeuvre contains a number of recurring subjects, which the artist executed in a variety of materials, including plaster, marble and bronze. This allowed Brancusi to explore various effects, such as the reflection of light. The signed Tête d’enfant endormie is an early version in the series. It is unusual that Brancusi painted the plaster, making it look like bronze.

Press release from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

Constantin Brancusi (Romanian, 1876-1957)

La Muse endormie (Sleeping muse)

1910

Bronze

16.1 x 27.7 x 19.3cm

Arthur Jerome Eddy Memorial Collection. The Art Institute of Chicago

© 2013 c/o Pictoright Amsterdam

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Noire et blanche (Black and white)

1926

Gelatin silver print

18 x 23.5cm

© Man Ray Trust / ADAGP – PICTORIGHT / Telimage – 2013

Man Ray’s Noire et blanche is a photograph exemplary of Surrealist art. The striking faces of the pale model and the dark mask have a doubling effect. This repetition is a reminder that a photograph is a double of what it represents, namely, a sign or an index of reality. In Surrealism the act of doubling indicates that we are all divided subjects made up of the conscious and unconscious. In reading this photograph as typical of primitivism, the woman can be understood as European civilisation and the mask as “primitive” Africa. The image draws a parallel between the two faces presenting them as related to each another. The title “black and white” is a word play because the order is reversed when reading the image left to right. The artist also printed a negative version of this image. The photograph was first published in Vogue. It is a portrait of Kiki of Montparnasse, Man Ray’s lover and model at the time the photograph was taken.

Text from the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam website [Online] Cited 05/05/2014. No longer available online

Medardo Rosso (Italian, 1858-1928)

Enfant malade (Ziek kind)

c. 1909

Aristotype

7.9 x 6.3cm

Private collection

Medardo Rosso (Italian, 1858-1928)

Enfant malade (Ziek kind)

1895 (1903-1904)

Bronze

25.5 x 14.5 x 16.5cm

Collectie Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan

Medardo Rosso (Italian, 1858-1928)

Madame X

1896

Wax

300mm

Venice, Ca’ Pesaro

Con una coerenza assoluta, insensibile alle polemiche e alle controversie che la sua arte suscitava, e più ancora al disprezzo oltraggioso di cui lo faceva segno la cultura ufficiale, il Rosso deduceva alle estreme conseguenze le premesse fondamentali della sua visione. Davanti ai nostri occhi una sgomentante superficie d’ombra da cui emerge la lama trepida e vibrante di un essere vivente, che contesta al nulla misterioso che lo incalza e in cui in un soffio si dissolverà, il suo diritto alla luce, cioè all’essenza vitale. Le premesse letterarie, le suggestioni filosofiche o vagamente esoteriche sono totalmente assorbite nella suprema qualità stilistica: lo scultore modula ed assottiglia la materia al limite del possibile, sull’orlo dell’astrazione assoluta, ricercandone spasmodicamente ogni vibrazione musicale; l’equazione scultura-luce-pittura poteva dirsi verificata.”

“With absolute consistency, insensitive to the controversies and disputes that his art aroused, and even more outrageous contempt of which he did hold official culture, Rosso deduced to the extreme the basic premises of his vision. Before our eyes a daunting shadow surface which shows the blade trembling and vibrating of a living being, which criticises the mysterious anything that presses him and when you blow in a dissolver, its right in the light, that all ‘vital’ essence. The premises literary, philosophical or vaguely esoteric suggestions are totally absorbed in the supreme quality of style: the sculptor modulation and tapering the matter to the extent possible, the absolute brink of abstraction, seeking spasmodically every musical vibration; the equation of light-sculpture-painting could be said to be verified.

Terrible translation by Google translate of an anonymous text = but so beautiful at the same time!

Constantin Brancusi (Romanian, 1876-1957)

Princesse X (Princess X)

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

29.7 x 23.7cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Paris

© 2013 c/o Pictoright Amsterdam

Photo: Bertrand Prévost

Constantin Brancusi (Romanian, 1876-1957)

Princesse X (Princess X)

1915-1916

Bronze

61.7 x 40.5 x 22.2cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Paris

© 2013 c/o Pictoright Amsterdam

Photo: Adam Rzepka

Princess X is a sculptured rendering of the French princess, Marie Bonaparte, by the artist Constantin Brâncusi. Princess Bonaparte was the great-grand niece of the emperor Napoleon Bonaparte…

According to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Brâncusi had been “at the center of two of modern arts most notorious scandals.” One of the scandals being that the Salon des Indépendants, in Paris where Brâncusi practiced his trade, discontinued the display of Princess X from its establishment for its apparent obscene content, as some thought it looked like a penis. After having his art taken off display, Brâncusi was shocked. He declared the incident a misunderstanding. He had created Princess X not as a sculpture depicting a more masculine subject, but the object of feminine desire and vanity.

After much accusation, Brâncuși insisted the sculpture had been his rendition of Marie Bonaparte. Brâncusi discussed the comparison of the bronze figure to the princess. He described his detest of Marie, as a “vain woman.” He claimed she went as far as placing a hand mirror on the table at mealtimes, so she could gaze upon herself. The sculpture’s C-like form reveals a woman looking over and gazing down, as if looking into an object. The large anchors of the sculpture resemble the “beautiful bust” which she possessed. Without knowing the context, to a viewer Princess X could look like an erect penis. Brâncusi allows the princess to gaze upon herself in an eternal loop locked in the bronze sculpture.

The style of Brâncusi is one that “was largely fuelled by myths, folklore, and primitive culture,” this combined with the modern materials and tools Brâncuși used to sculpt, “formed a unique contrast… resulting in a distinctive kind of modernity and timelessness.” The technique Brâncusi was known for and used on Princess X could be mistaken for a penis, but in fact it was the simple form of a woman.

“What my art is aiming at, is above all realism; pursue the inner hidden reality, the very essence of objects in their own intrinsic fundamental nature: this is my only preoccupation.” – Constantine Brâncusi.

Text from the Wikipedia website

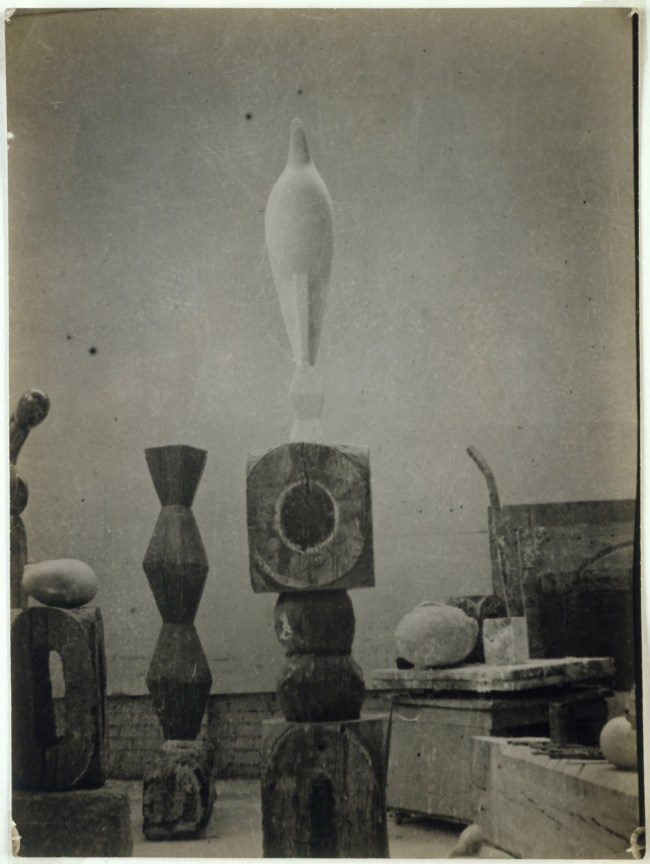

Constantin Brancusi (Romanian, 1876-1957)

View of the Studio with Maïastra

1917

Gelatin silver print

23.9 x 17.8cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Paris

© 2013 c/o Pictoright Amsterdam

According to Constantin Brancusi’s own testimony, his preoccupation with the image of the bird as a plastic form began as early as 1910. With the theme of the Maiastra (1910-18), he initiated a series of about thirty sculptures of birds.

The word maïastra means “master” or “chief” in Brancusi’s native Romanian, but the title refers specifically to a magically beneficent, dazzlingly plumed bird in Romanian folklore. Brancusi’s mystical inclinations and his deeply rooted interest in peasant superstition make the motif an apt one. The golden plumage of the Maiastra is expressed in the reflective surface of the bronze; the bird’s restorative song seems to issue from within the monumental puffed chest, through the arched neck, out of the open beak. The heraldic, geometric aspect of the figure contrasts with details such as the inconsistent size of the eyes, the distortion of the beak aperture, and the cocking of the head slightly to one side. The elevation of the bird on a saw-tooth base lends it the illusion of perching. The subtle tapering of form, the relationship of curved to hard-edge surfaces, and the changes of axis tune the sculpture so finely that the slightest alteration from version to version reflects a crucial decision in Brancusi’s development of the theme.

Seven other versions of Maiastra have been identified and located: three are marble and four bronze…

Extract from Lucy Flint. “Constantin Brancusi: Maiastra,” on the Guggenheim website [Online] Cited 17/03/2021

Constantin Brancusi (Romanian, 1876-1957)

Self-portrait in the studio

c. 1934

Gelatin silver print

39.7 x 29.7cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Paris

© 2013 c/o Pictoright Amsterdam

Photo: Philippe Migeat

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Rayographie (Rayograph)

1925

Photogram

50 x 40.5cm

Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

© Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2013

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Le Violon d’Ingres (Ingres’s Violin or The Hobby)

1924

Gelatine silver print

17.2 x 22.4cm

Private collection Turin

© Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2013

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Self-portrait with the lamp

1934

Gelatin silver print

10. 8 x 8cm

© Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2013

Medardo Rosso (Italian, 1858-1928)

Self-portrait in the studio

c. 1906

Modern contact print of the original glass negative

12.7 x 13cm

Private collection

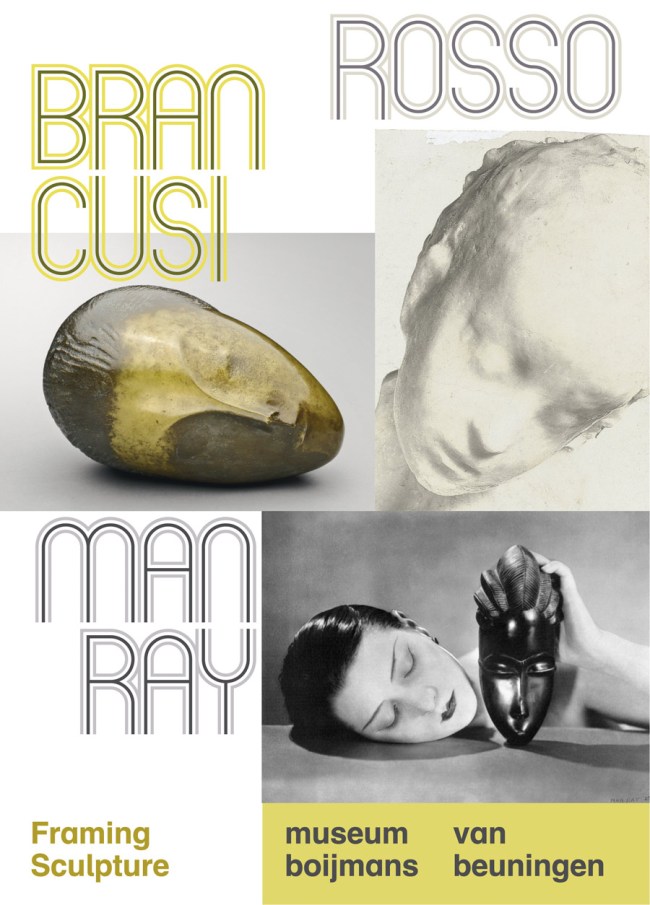

Brancusi, Rosso, Man Ray – Framing Sculpture exhibition poster

Constantin Brancusi, La Muse endormie, 1910. Arthur Jerome Eddy Memorial Collection. The Art Institute of Chicago. © 2013 c/o Pictoright Amsterdam /

Medardo Rosso, Enfant malade, c. 1909. Private collection / Man Ray, Noire et blanche, 1926

© Man Ray Trust / ADAGP – PICTORIGHT / Telimage – 2013

Design: Thonik.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

Museumpark 18-20

3015 CX Rotterdam

The Netherlands

Phone: +31 (0)10 44.19.400

Opening hours:

Tuesdays to Sundays, 11am – 5pm

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

0.000000

0.000000

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Studienkopf zur Stuttgarter Iphigenie [Study of a Head for Stuttgart Iphigenia]' 1870 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Studienkopf zur Stuttgarter Iphigenie [Study of a Head for Stuttgart Iphigenia]' 1870](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_studienkopf-web.jpg?w=650&h=815)

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Poesie, Zweite Fassung [Poetry, Second Version]' 1863 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Poesie, Zweite Fassung [Poetry, Second Version]' 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_poesie-web.jpg?w=650&h=807)

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Lucrezia Borgia, Bildnis einer Römerin in weißer Tunika und rotem Mantel [Lucrezia Borgia, Portrait of a roman in white tunic and red cloak]' 1864/1865 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Lucrezia Borgia, Bildnis einer Römerin in weißer Tunika und rotem Mantel [Lucrezia Borgia, Portrait of a roman in white tunic and red cloak]' 1864/1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_borgia-web.jpg?w=650&h=781)

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Das Urteil des Paris [The Judgement of Paris]' 1870 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Das Urteil des Paris [The Judgement of Paris]' 1870](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_paris-web.jpg)

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Ruhende Nymphe [Resting Nymph]' 1870 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Ruhende Nymphe [Resting Nymph]' 1870](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_nymphe-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.