Exhibition dates: 13th November 2013 – 10th March 2014

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Emma Thiollier painting on top of one of the towers of Notre Dame, photographed by her father Félix Thiollier

1907

“Why is the price of justice so high?”

Maheude, Germinal

“Beneath the blazing of the sun, in that morning of new growth, the countryside rang with song, as its belly swelled with a black and avenging army of men, germinating slowly in its furrows, growing upwards in readiness for harvests to come, until one day soon their ripening would burst open the earth itself.”

Émile Zola. Germinal (1885)

This is the biggest collection of photographs by the French photographer Félix Thiollier available on the Internet. I spent hours cleaning up the images to a presentable standard (mixing them with appropriate paintings by Corot and Francois-Auguste Ravier), so I hope you enjoy the posting.

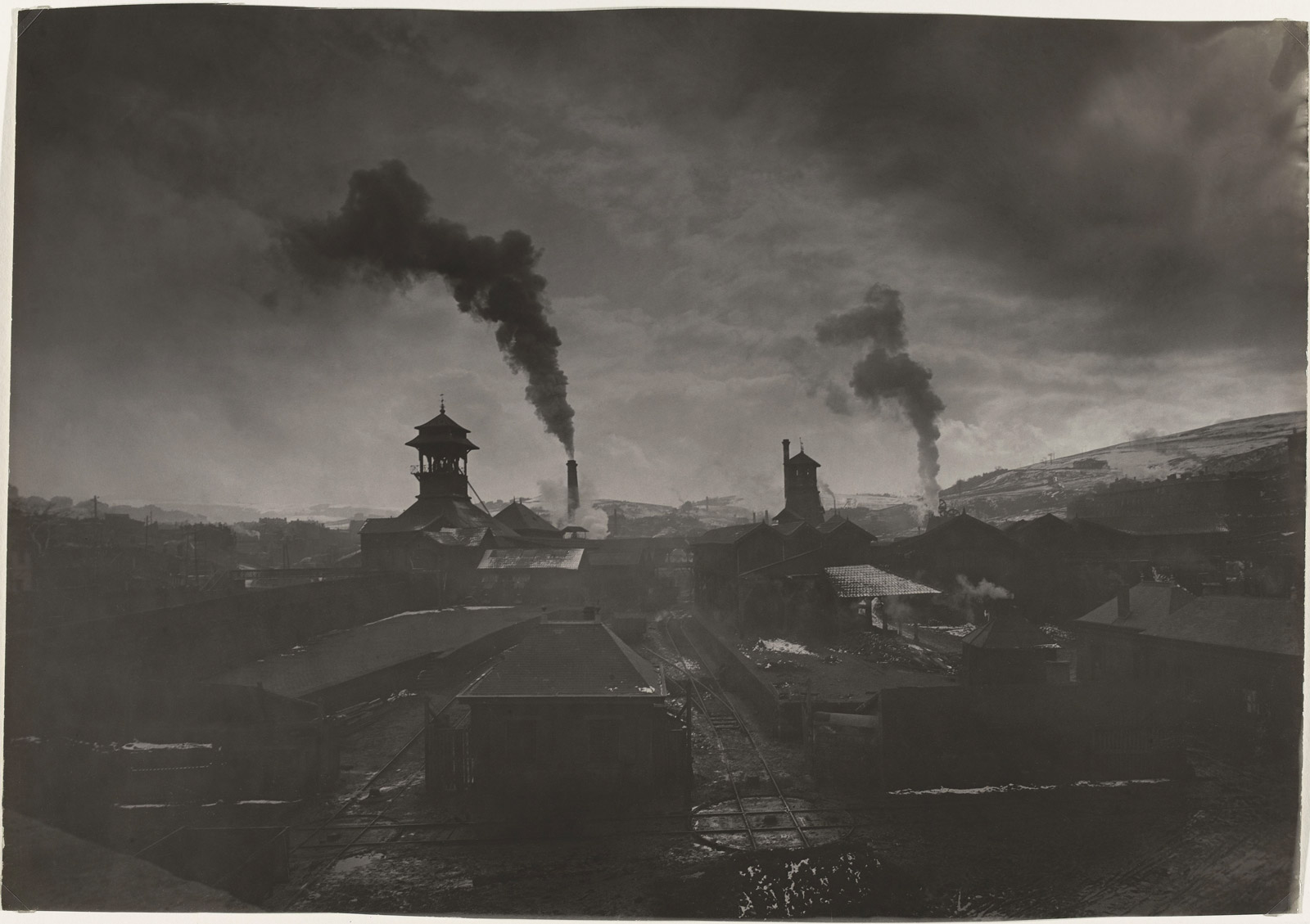

While the bucolic photographs of ruins, pastoral landscapes and shepherdess (bucolic – via Latin from Greek boukolikos, from boukolos ‘herdsman’) are relatively straight forward, it is Thiollier’s sensitive portrayal of the “industrial image” – of the mines and factories of Forez – that hold weight here. Thiollier emphasises the theatrical aspects of the landscape (he loved shooting at dusk), finding new subject matter among the photogenic nature of industrial sites “his last images… extolling these new “worthless” locations that included scrapheaps, wasteland and abandoned pitheads, such were the ruins of modern Forez, that met his melancholy and clear-sighted gaze.”

His photographs of the “black city” are atmospheric, vivid and powerful. Post-Romantic lyricism is still present in these images but is now coupled with a unique vision that has more earthy, psychological overtones. The anonymous figures of workers or coal pickers toiling away in oppressive landscapes are never better realised than in the line of figures silhouetted against the dying light in Mining Landscape, Saint-Etienne (1895-1910, below); the solitary figure caught in the rising dust on the side of the hill in Mining Landscape, Saint-Etienne (1895-1910, below – enlarge the image to see the figure). The desolation of an industrial revolution mining town is also perfectly captured in Mining Landscape, The Chatelus Pit at Saint-Etienne (1907-1912, below).

All three images remind me of the epic film Germinal staring Gerard Depardieu, based on the novel of the same name by Émile Zola. I’m sure that Thiollier would have been familiar with the book, it being a sensation upon original publication (1885). The book may well have appealed to Thiollier because he was a wealthy man, an industrialist who had reinvented himself as a gentleman farmer, who finally leaves the picturesque behind to photograph, “atmospheric phenomena studies, the architectural and mineral landscape created by the hard work of men, and how the human figure related to this.” In all its hope and misery.

Thiollier becomes so much more than an amateur photographer. His impressions of a dark, hidden drama beating at the heart of industrial, fin de siècle France provided him with the opportunity to become a progenitor of modernism, “ten years before the photogenic nature of industrial sites would be elevated into a credo of photographic modernism.” (Fin de siècle has connotations of both the closing and onset of an era, as the end of the 19th century was felt to be a period of degeneration, but at the same time a period of hope for a new beginning).

Finally, despite his willingness to remain on the sidelines, Thiollier may well be getting the approbation he deserves.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Émile Zola (French, 1840-1902)

Germinal

Title page of the 1885 edition

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Undergrowth in Forez (Sous-bois en Forez)

Nd

© Félix Thiollier

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Around Saint-Etienne (Environs Saint-Etienne)

1907-1912

Autochrome

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (French, 1796-1875)

Forest of Fontainebleau

1834

Oil on canvas

69 1/8 x 95 1/2 in. (175.6 x 242.6cm)

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Figure contemplant les monts du Menzenc (Emma Thiollier, fille du photographe)

Figure contemplating the mountains of Menzenc (Emma Thiollier, daughter of the photographer)

1895-1905

Collection Julien Laferrière

© Musée d’Orsay (dist. RMN) / Patrice Schmidt

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Landscape with Figure, Forez (Loire)

c. 1880-1882

Silver gelatin dry plate print on barium paper from a silver gelatin dry plate glass negative

H. 18.5; W. 22cm

Paris, Musée d’Orsay

Gift of Mr and Mrs Noël Sénéclauze, 2007

© Musée d’Orsay (dist. RMN)

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Landscape with Figure, Forez (Loire) (detail)

c. 1880-1882

Silver gelatin dry plate print on barium paper from a silver gelatin dry plate glass negative

H. 18.5; W. 22cm

Paris, Musée d’Orsay

Gift of Mr and Mrs Noël Sénéclauze, 2007

© Musée d’Orsay (dist. RMN)

Francois-Auguste Ravier (French, 1814-1895)

Landscape with Setting Sun

Nd

Oil on canvas

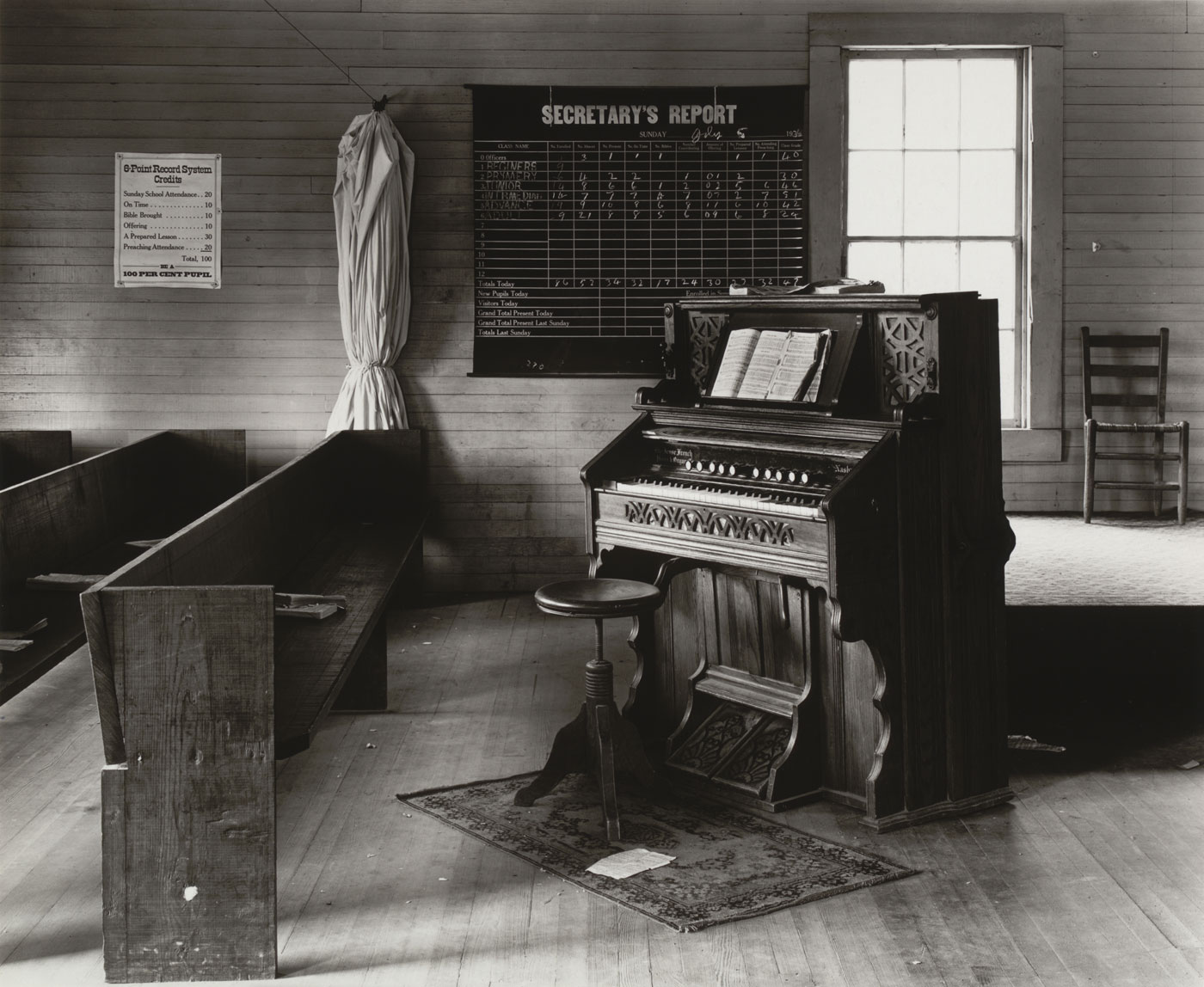

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Mining Landscape, Saint-Etienne

1895-1910

Silver gelatin dry plate print on barium paper from a silver gelatin dry plate glass negative

H. 28; W. 39.5cm

Paris, Musée d’Orsay

© Musée d’Orsay (dist. RMN)

Félix Thiollier

Although the talent of photographer Félix Thiollier was still unrecognised twenty years ago, this is mainly because it never occurred to him to seek recognition as such. When, at the age of 35, he decided to live off his private income, this ribbon manufacturer from Saint-Étienne intended to devote himself to art and archaeology. But feeling restricted in his role as scholar of the local area, Thiollier very quickly started publishing illustrated books. This enterprise, intended to promote both the rich natural environment and cultural heritage of Forez and the work of his artist friends, seemed to take up most of his energy, when he was not otherwise involved with initiatives to protect the local heritage of Saint-Étienne or promote the culture of the area.

It was his activities in these two latter fields that brought him both regional and national recognition, and until recently his reputation was based on these activities alone. Today, his resolute determination to remain on the fringes of the photographic circles of his time seems consistent with Thiollier’s passion for this medium that he would practise continuously for over half a century. In addition to showing the rich variety of subjects that inspired him, this exhibition seeks to give the viewer an appreciation of the originality of an approach based wholly on an inexhaustible passion for the picturesque: guiding his photographical machine, this mechanics of looking would lead him from bucolic landscapes and scenes of rural life to sensitive images of an industrial environment largely ignored by the amateur photographers at the turn of the 20th century.

“At an age when I deluded myself into believing that it was possible to combine the picturesque and archaeology…”

Thiollier’s intellectual and aesthetic background was typical of that section of the provincial elite in the 19th century who took a keen interest in art and archaeology, and had a great love of books. When, at the end of the 1850s, senior figures encouraged him to take photographs of notable sites and monuments in the Forez area, they already had a project in mind to produce a book about this ancient province which, celebrated by Honoré d’Urfé in L’Astrée (1607-1627), extended right across the department of the Loire into parts of the Haute-Loire and Puy-de-Dôme. They were all steeped in the Romantic tradition of the illustrated picturesque book, a tradition that would flourish in the second half of the century through many regional publications, like many local responses in this search for the identity of the regions of France. Illustrated with his early and more recent photographs, Thiollier’s Le Forez pittoresque et monumental, published in 1889, is one of the last and most outstanding examples of these.

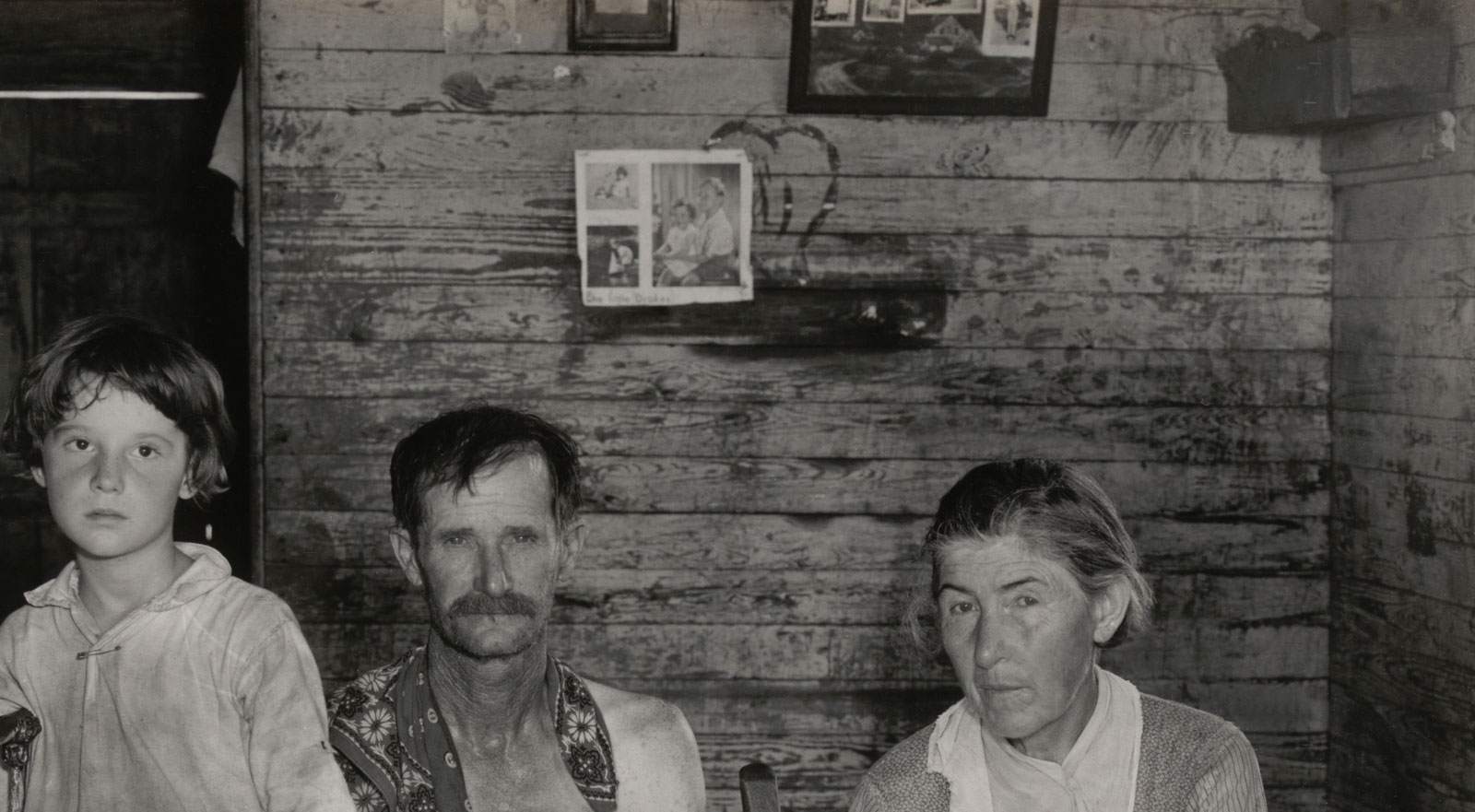

Perpetuating the rustic ideal

In leaving the town and his activities as an industrialist, Thiollier did not just move closer to the monuments and landscapes he had undertaken to describe. Having acquired two modest country estates – a hunting lodge near the ponds around Précivet, and the former commandery of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem at Verrières – he also reinvented himself as a gentleman farmer in the heart of this arcadian Forez countryside, which, in his view, was under threat. Heavily influenced by the example of the Barbizon artists whose paintings he collected along with those of his naturalist painter friends, he never tired of capturing the disappearing traces of traditional skills and ways of life with the eye of a painter. However, it required a certain poetic detachment for photographs to complete this grief. This was usually achieved with the loyal help of his daughter, who appeared in his photographs whenever he wanted to draw attention to the timeless nature of peasant genre scenes.

“Stylistic Landscapes”

Although Thiollier had nursed an ambition to become a landscape photographer before he met Ravier in 1873, it is essential to recognise the influence of this painter from Morestel – who had been practising photography since the 1850s – in order to understand why Thiollier moved towards a more committed, if unrevealed, artistic approach to the medium. After many sessions spent “photographicking” together, their shared vision is expressed in the resulting images of autumnal and winter landscapes, which, devoid of any human presence, offer many light-filled variations on the handful of motifs chosen by the painter: still pools or the banks of streams, solitary outlines of dead trees, undergrowth and country paths, it is a complete repertoire of images of the Dauphiné region that stimulated Thiollier’s desire to extol the natural beauty of the Forez. Although he had to include riverscapes and mountain panoramas to reflect the true variety of this beautiful area, he almost always concentrate on the sky and studies of clouds, ideally enhanced by reflections playing on the still water.

The range of effects Thiollier developed, although intended in part to transpose the Post-Romantic lyricism which, in Ravier’s work, was conveyed through blazing colours and highly skilful brush- work, nonetheless indicates that his images of the countryside were produced with a perfect understanding of his medium. In pushing for a rapprochement with contemporary artistic photography, the main feature of his style was thus the expressiveness of the contrasts in values. It is this preference for representing nature in monochrome that partly explains his liking for snowscapes, and also prompted him to undertake almost systematic research into contre-jour, the most appropriate effect for both synthesising his motifs and revealing the theatrical aspects of the landscape. Indeed, the all-revealing clarity of broad daylight was far less of an inspiration to Thiollier than the atmosphere of solitude and silence that came with the dusk. As he often noted in his descriptions, it was when the shadows were at their most dramatic that the countryside cast its strongest spell over him.

Territories of intimacy

Alongside the search for effects that so often excited this landscape photographer, Thiollier’s solitary wanderings too were a source of more physical, more earthy themes that reveal a personal shift in the sensitive approach towards the territory. Although the traditional picturesque approach, which he had adopted until the 1880s, had been fuelled by Romanticism, it was also partly because it implied a way of considering the environment as a spectacle and thus relied heavily on the subjectivity of the first viewer that chose to depict it.

It was this look at the landscape that Thiollier now seems to stage, finding that this, far more than the self-portrait, offered him a way to incorporate himself into the landscape that he claimed as his own, and in doing so, into his work. Admittedly, the natural world he shows us is always uninhabited, but this makes it now all the better to fill with the presence of the photographer: the bleaker his selected locations, in relation to the accepted picturesque aesthetic, the more personal these choices turn out to be. Swept along by the rapid improvements in photographic techniques, the snap shot practitioner was freed from the pictorial tradition that restricted him to this side of Alberti’s “window”: his images are those of someone taking a stroll into the heart of the countryside, or more precisely, pausing at some point, seized by the desire to capture forever the emotion that had prompted him to set up his equipment right in the middle of the pathway, or, as often happened, in a quiet corner of his garden.

The picturesque as developer: the photogeneity of the black city

Forty years after having made the first important choices of his life, learning photography at the same time when he renounced a career as a mine engineer, the former ribbon manufacturer discovered a photographic passion for Saint-Étienne, “a lively and animated city (…) to which the local industries brought a special picturesque character”. It was not easy to break away from a code of aesthetic appreciation, which, at a deeper level, was also a way of recognising the world.

The mines and factories in the cradle of the first French industrial revolution were, moreover, particularly appropriate subjects for what came to absorb him more than ever: atmospheric phenomena studies, the architectural and mineral landscape created by the hard work of men, and how the human figure related to this. It was as if the anonymous figures of workers or coal pickers had come just at the right moment, not only to enhance that “impression (…) of a sort of hidden drama” that best reveals the continuing influence of Ravier in his work, but also to fuel his inexhaustible desire for the picturesque. Besides, how could the poor people of this black town have concealed the exotic charm of their poverty from the lens of this bourgeois citizen who, in spite of himself, was still Thiollier?

Although Thiollier’s interest in photography gradually developed until eventually it became much more than the project to promote the natural and archaeological treasures of the area, it was perhaps because this industrialist turned gentleman farmer had realised intuitively that “machine art” (Delacroix) could be the way to resolve, in images, this tension between two worlds that lived side by side – the rural and traditional on one side and the industrial and contemporary on the other – and he belonged to both. The union of the picturesque and photography was sealed and could not be broken until his project as the editor of Le Forez pittoresque et monumental was completed, and this meant the aesthetic appropriation of the mental and identitarian territory of Forez as he saw it, reconciled with itself in the context of the “industrial image”. The choice of medium, precisely because Thiollier officially refused to give it any artistic legitimacy, would not however be made without consequences.

By admitting the creative superiority of the eye over the hand, the mechanised tool for reproducing images would gradually enable him to establish an independent vision, with a boldness that would burst into colour: ten years before the photogenic nature of industrial sites would be elevated into a credo of photographic modernism, his last images were extolling these new “worthless” locations that included scrapheaps, wasteland and abandoned pitheads, such were the ruins of modern Forez, that met his melancholy and clear-sighted gaze.

Text from the Musée d’Orsay website

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

4 am Roche-La-Moliere, Forez (4H du matin vers Roche-La-Moliere, Forez)

c. 1870

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Mining Landscape, Saint-Etienne

1895-1910

Paris, Musée d’Orsay

© RMN (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

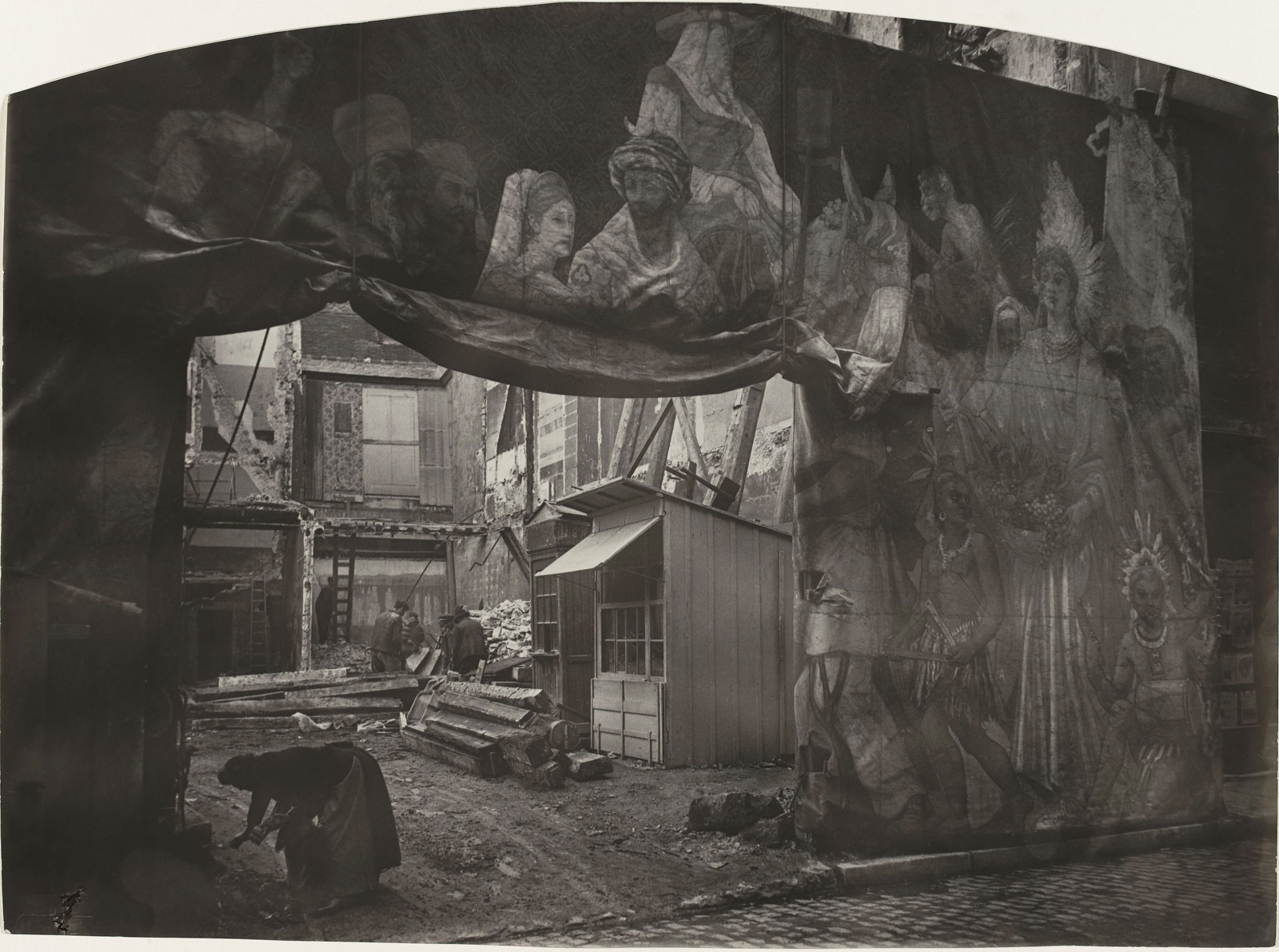

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Decor for a fete or fair, Saint-Etienne (Décor de fête ou de foire, Saint-Etienne)

1890-1910

Paris, Musée d’Orsay

© RMN (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Mining Landscape, The Chatelus Pit at Saint-Etienne

1907-1912

Silver gelatin dry plate print on barium paper from a silver gelatin dry plate glass negative

H. 28; W. 40cm

Paris, Musée d’Orsay

© Musée d’Orsay (dist. RMN)

Francois-Auguste Ravier (French, 1814-1895)

A Marsh at Sunset

Nd

Oil on canvas

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Boats on the Seine, Paris (Bateaux sur la Seine, Paris)

1903-1905

Silver gelatin print

29.7 x 39.4 cm

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Shepherdess and Flock

1890-1910

Silver gelatin dry plate print on barium paper from a silver gelatin dry plate glass negative

H. 29.2; W. 38.4cm

Paris, Musée d’Orsay

© Musée d’Orsay (dist. RMN) / Patrice Schmidt

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

The Verpilleux Coking Plant, near Saint-Etienne

1895-1910

Silver gelatin dry plate print on barium paper from a silver gelatin dry plate glass negative

H. 39.3; W. 29.9cm

Paris, Julien-Laferrière collection

© Musée d’Orsay / Patrice Schmidt

Félix Thiollier (French, 1842-1914)

Landscape with Ruin

c. 1870

Biography

1842

Maurice Félix Thiollier is born in Saint-Étienne into a wealthy family of ribbon manufacturers who espouse the values of social Catholicism.

1847

The Thiollier family moves to Paris. A French priest, l’abbé Paul Lacuria, is engaged as a tutor for Félix’s older brothers.

1851-52

The Thiollier family returns to Saint-Étienne. Félix Thiollier goes to school at the Collège Saint-Thomas d’Acquin in Oullins near Lyon.

1858

Eligible to take the competitive entrance test for the École des Mines de Saint-Étienne, Félix Thiollier chooses to train at the ribbon factory. He takes up photography, and possibly receives technical advice at this time from Stéphane Geoffray, a photographer from Roanne.

1867

At the age of 25, he sets up his own ribbon factory in Saint-Étienne.

1869

Through the painter Henri Baron, his father’s cousin, he is offered a place in the studio of the painter Louis Français, which he turns down for family reasons.

1870

Marries Cécile Testenoire-Lafayette, daughter of Claude-Philippe Testenoire-Lafayette, a lawyer and local scholar from Saint-Étienne, and president of La Diana – the Historical and Archaeo-logical Society of Forez (1870-1879).

1873

Meets the Dauphinois painter Auguste Ravier and soon gives up hope of becoming a professional painter.

1879

Decides to live off his private income. Becomes a member of La Diana.

1881

Publication of the first book to be illustrated with his photographs, Le Poème de l’âmeby his friend the painter Louis Janmot.

1885

First exhibition of his photographs, presented in the great hall belonging to La Diana in Montbrison, on the occasion of the 52nd congress of the Société Française d’Archéologie. Becomes a member of this society, which awards him its silver medal.

1886

Publication of Château de la Bastie d’Urfé et ses seigneurs.

1889

Publication of Forez pittoresque et monumental. Receives a silver medal for his illustrated books at the universal exhibition in Paris.

1894

Becomes a non-resident member of the Committee for Historic and Scientific Works at the Ministry for Public Instruction.

1895

Receives the Légion d’Honneur for his work as a photographer.

1897

Receives the title of honorary curator of the Saint-Étienne Museum of Art and Industry.

1900

Receives another silver medal for his illustrated books at the universal exhibition in Paris.

1902

Publication of L’Histoire de Saint-Etienne by Claude-Philippe Testenoire Lafayette, illustrated with photographs by Félix Thiollier.

1914

Death of Félix Thiollier on 12 May at Saint-Étienne.

1917

Publication of his biography by Sébastien Mulsant.

Musée d’Orsay

62, rue de Lille

75343 Paris Cedex 07

France

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 9.30am – 6pm

Closed on Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.