Exhibition dates: 22nd November, 2014 – 4th January, 2015

Curator: Sarah Hermanson Meister, Curator, Department of Photography

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, New Canaan, Connecticut

1975

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

This is the most successful, long running group portrait series in the history of photography. I have always liked the images because of their stunning clarity, delicate tonality and wonderful arrangement of the figures. Much as they shield their privacy, as a viewer I feel like I have grown up with these women, the sisters I never had. Some images are more successful than others, but as a body of work that focuses on the “face” we present to the world, they are without peer.

Just imagine being these women (and being the photographer), taking on this project and not knowing where it would lead, still not knowing where it will lead. There is a fascinating period in the photographs between 1986 and 1990, as we see the flush of youth waning, transitioning towards the beginning of middle age. As they grow older and closer I feel that I know their characters. I look for that inflection and nuance of presentation that make them more than just faces, more than just photographic representation. The lines on their faces are the handwriting of their travails and I love them all for that.

In each photograph they are as beautiful as the next, not in a Western sense, but in the sense of archetypal beauty, the Platonic form of all beauty – the beauty of women separated from the individuality of the object and considered by itself. In each of these images you can contemplate that form through the faces of these women – they are transcendent and pure. It is as if they live beyond space and time, that the photographs capture this sense of the sublime. Usually the sublime is regarded as beyond time… but not here.

A simply magnificent series.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. Let’s hope that there are more images from the series that we can eventually see and that there are some platinum prints being produced. The images deserve such a printing.

Many thankx to MoMA for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Throughout this series, we watch these women age, undergoing life’s most humbling experience. While many of us can, when pressed, name things we are grateful to Time for bestowing upon us, the lines bracketing our mouths and the loosening of our skin are not among them. So while a part of the spirit sinks at the slow appearance of these women’s jowls, another part is lifted: They are not undone by it. We detect more sorrow, perhaps, in the eyes, more weight in the once-fresh brows. But the more we study the images, the more we see that ageing does not define these women. Even as the images tell us, in no uncertain terms, that this is what it looks like to grow old, this is the irrefutable truth, we also learn: This is what endurance looks like. …

These subjects are not after attention, a rare quality in this age when everyone is not only a photographer but often his own favourite subject. In this, Nixon has pulled off a paradox: The creation of photographs in which privacy is also the subject. The sisters’ privacy has remained of utmost concern to the artist, and it shows in the work. Year after year, up to the last stunning shot with its triumphant shadowy mood, their faces and stances say, Yes, we will give you our image, but nothing else.”

Susan Minot. “Forty Portraits in Forty Years: Photographs by Nicholas Nixon,” on the ‘New York Times’ website, October 2014 [Online] Cited 01/01/2015. No longer available online. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Harwich Port, Massachusetts

1978

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, East Greenwich, R.I.

1980

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Allston, Mass.

1983

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Cambridge, Mass.

1986

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Wellesley, Massachusetts

1988

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Woodstock, Vt.

1990

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

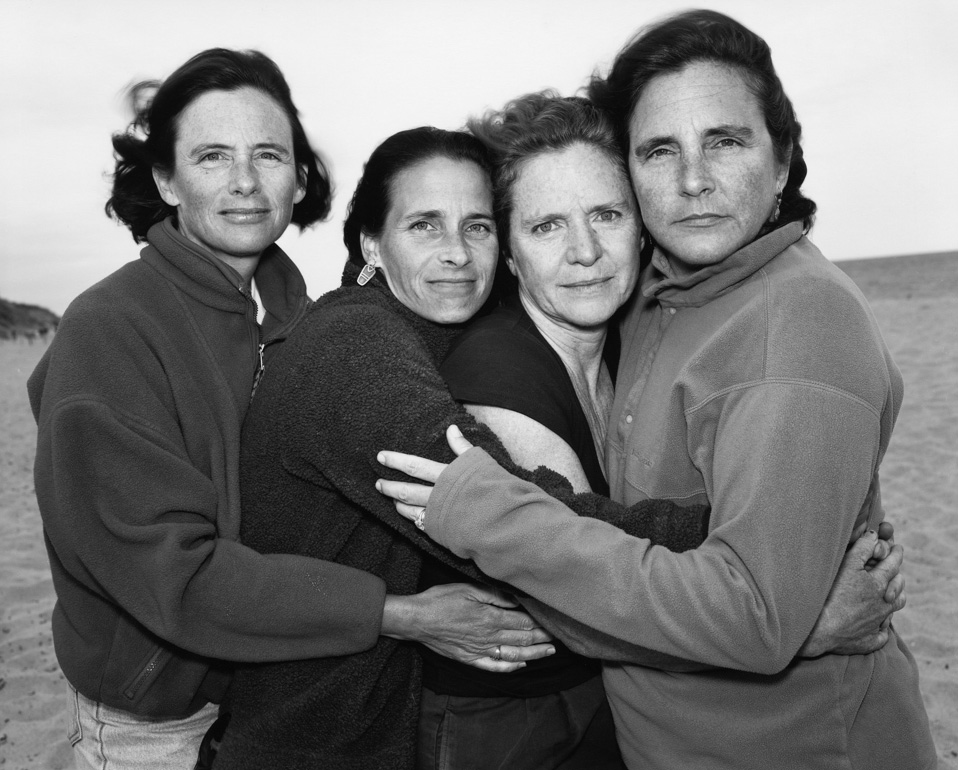

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Grantham, N.H.

1994

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

In August 1974, Nicholas Nixon made a photograph of his wife, Bebe, and her three sisters. He wasn’t pleased with the result and discarded the negative. In July 1975 he made one that seemed promising enough to keep. At the time, the Brown sisters were 15 (Mimi), 21 (Laurie), 23 (Heather), and 25 (Bebe). The following June, Laurie Brown graduated from college, and Nick made another picture of the four sisters. It was after this second successful picture that the group agreed to gather annually for a portrait, and settled on the series’ two constants: the sisters would always appear in the same order – from left to right, Heather, Mimi, Bebe, and Laurie – and they would jointly agree on a single image to represent a given year. Also significant, and unchanging, is the fact that each portrait is made with an 8 x 10″ view camera on a tripod and is captured on a black-and-white film negative.

The Museum has exhibited and collected the Brown Sisters from the beginning; since 2006, acquiring the series both as lusciously tactile contact prints and as striking 20 x 24″ enlargements (a new scale for Nixon). This installation – featuring all 40 images – marks the first time the Museum has displayed these larger prints.

In his first published statement about photography, written the year he made the first of the Brown Sisters portraits, Nixon remarked, “The world is infinitely more interesting than any of my opinions about it.” If he was modest about his opinions, though, his photographs clearly show how the camera can capture that infinitely interesting world. And to the attentive viewer, these silent records, with their countless shades of visual and emotional grey, can promote a new appreciation of an intangible part of it: the world of time and age, of commitment and love.

Text from the MoMA website

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Marblehead, Mass.

1995

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Brookline, Massachusetts

1999

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Eastham, Mass.

2000

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Cataumet, Mass.

2004

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Dallas

2008

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Truro, Mass.

2010

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Truro, Mass.

2011

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Boston

2012

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

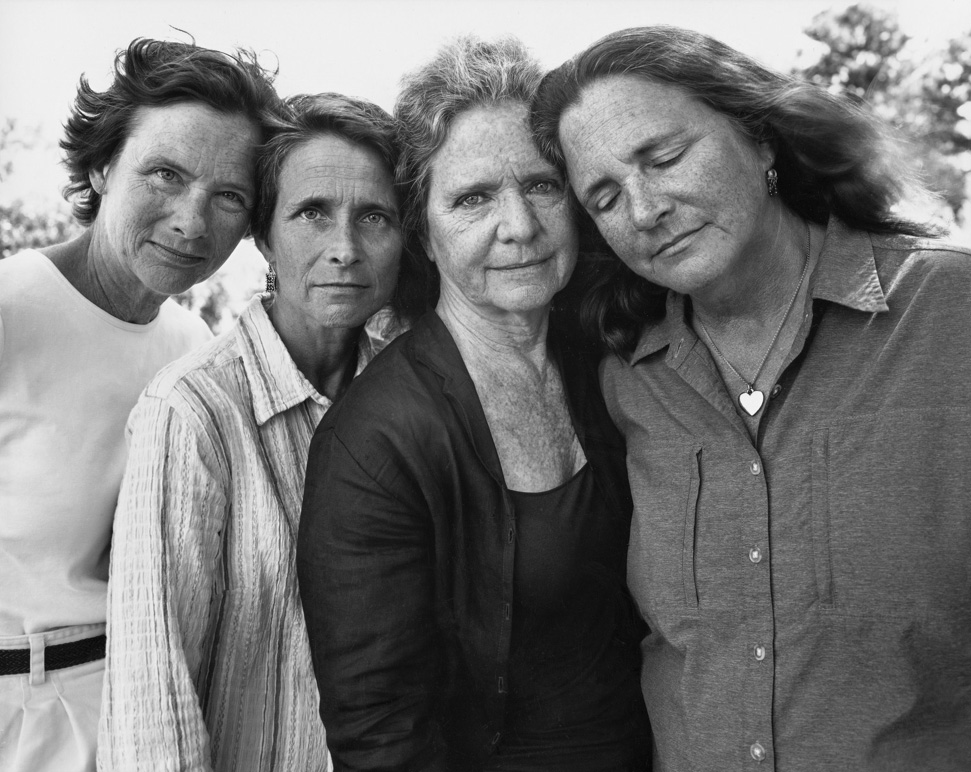

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters, Wellfleet, Massachusetts

2014

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Parkinson III Fund

© 2014 Nicholas Nixon

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

You must be logged in to post a comment.