Exhibition dates: 23rd April – 17th August 2014

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Sugar Loaf Islands and Seal Rocks, Farallons

1868-1869

From the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Who would you put in your top eleven photographers of all time?

(in no particular order)

- Minor White

- Eugene Atget

- Frederick Sommer

- Carelton Watkins

- Julia Margaret Cameron

- Walker Evans

- Edward Weston

- Lee Friedlander

- Manuel Alvarez Bravo

- Diane Arbus

- Paul Strand

and then it gets a bit more difficult…

Is it a Josef Sudek, Robert Adams, Aaron Siskind, Man Ray, Berenice Abbott, Helen Levitt, Emmet Gowin, William Clift, Ernest Cole, William Eggleston, Lee Friedlander, Cindy Sherman, Charles Marville, Vivian Maier, Saul Leiter and suggestions from others – André Kertész, Josef Koudelka, Dorothea Lange, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Edouard Boubat, Paul Caponigro, etc …

What is more interesting is to ask:

Who are the interesting photographers anywhere who are alive now?

And my answer would be: there are very few who are alive now that are interesting.

That is – by looking at the ideas that are present in poetry, music, philosophy or even politics – who is there that is truly taking these ideas forward (or ideas that are as interesting).

Or who is arranging images with the elegance of a Sommer or an Atget or the dynamics of Arbus

= few if any.

In other words whose acts am I hanging upon, so that I am waiting with great anticipation to see what they are going to do next.

Only a few is my answer.

Which living photographers would I walk a mile to see their work?

= some (eg Lee Friedlander, Wolfgang Tillmans)

Which living Australian photographers would I walk an hour in the hot January sun to see?

= possibly two (Bill Henson, Rosemary Laing)

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. Just look at Cape Horn, near Celilo (1867, below). You are not likely to see a more magnificent landscape photograph than this.

Many thankx to the Cantor Arts Center for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Devils’ Cañon Geysers, Looking Up

c. 1867

From the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Devils’ Cañon Geysers, Looking Up (detail)

c. 1867

From the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Alcatraz from North Point

1862–1863

From the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

The Wreck of the Viscata

March 1868

From the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Magenta Flume Nevada Co. Cal.

c. 1871

From the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Flour and Woolen Mills, Oregon City

1867

From the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon

Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Cape Horn, Columbia River

1867

From the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Mt. Hood and the Dalles, Columbia River

1867

From the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Cape Horn, near Celilo

1867

From the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

The Yosemite Valley from the “Best General View”

1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

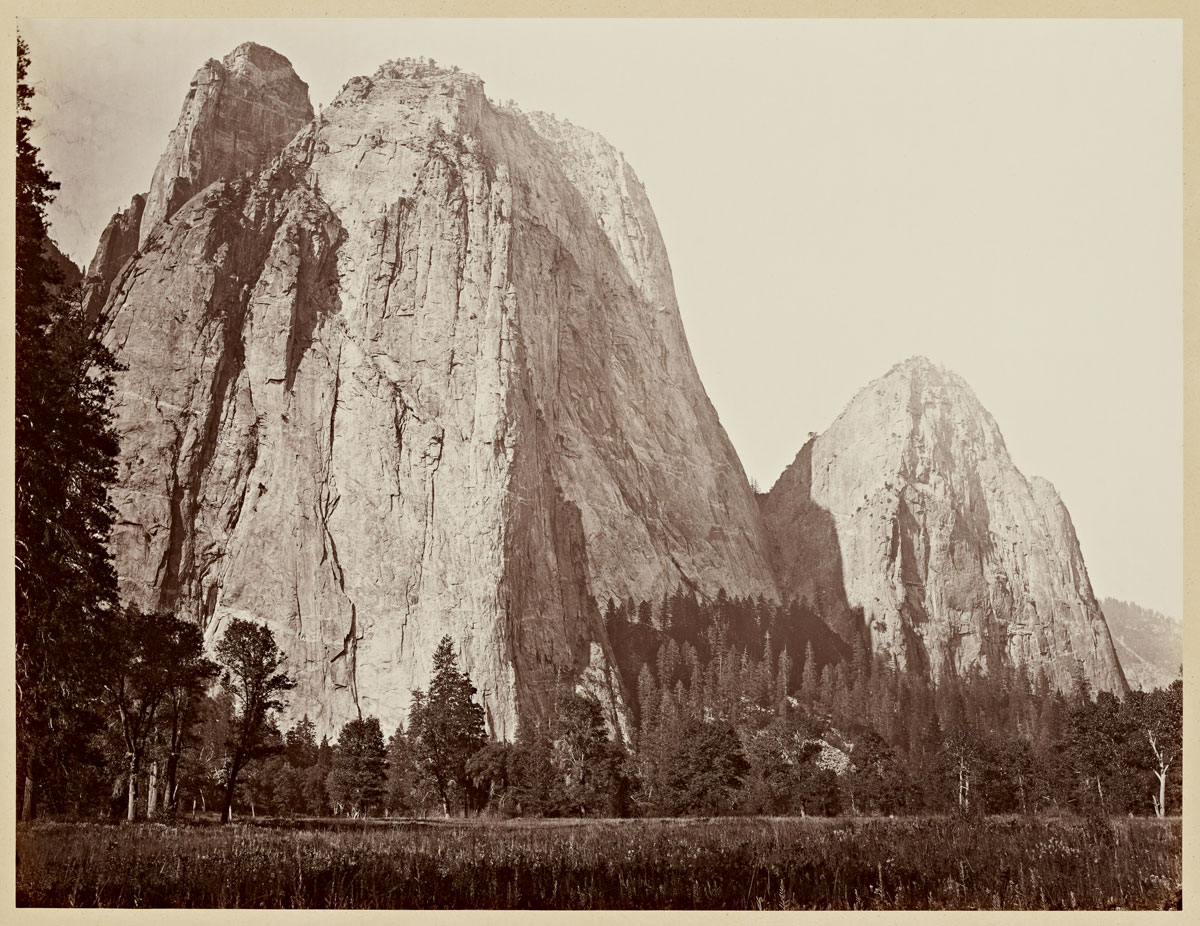

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Cathedral Rocks, 2630 ft., Yosemite

1865-1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Pompompasos, the Three Brothers, Yosemite 4480 ft.

1865-1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Mirror View of the North Dome, Yosemite

1865-1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Born in upstate New York, Carleton Watkins (1829-1916) ventured west in 1849 to strike it rich. But instead of prospecting for gold, Watkins developed a talent for photography – a medium invented only 22 years before. He documented the remote Pacific Coast in the 1860s and 1870s, capturing its vast scale and spirit with a custom-built camera that created “mammoth” 18 x 22-inch glass-plate negatives. In June 1864, his stunning photographs of Yosemite’s valley, waterfalls and peaks proved instrumental in convincing President Abraham Lincoln and the 38th U.S. Congress to pass the Yosemite Valley Grant Act, legislation that preserved the land for public use and set a precedent for America’s National Park System.

As the nation celebrates the 150th Anniversary of the Yosemite Grant, the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University presents Carleton Watkins: The Stanford Albums, an exhibition featuring more than 80 original mammoth prints from three unique albums of Watkins’s work: Photographs of the Yosemite Valley (1861 and 1865-66), Photographs of the Pacific Coast (1862-76), and Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon (1867 and 1870). The exhibition will be on view April 23 through August 17, 2014. Also featured will be cartographic visualisations developed in collaboration with Stanford’s Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis and the Bill Lane Center for the American West, which provide dynamic context for the geography and natural history of Watkins’s photographs. A fully illustrated publication will accompany the exhibition.

“The Cantor is thrilled to be leading such an innovative, interdisciplinary effort to look at Watkins’s work anew,” says Connie Wolf, the Cantor’s John & Jill Freidenrich Director. “These extraordinary albums from Stanford University Libraries’ singular collection provide us with an unparalleled opportunity to examine Watkins’s place in the history of photography, and to more fully understand the critical role photography played in the preservation, promotion, and development of the West. It is fascinating to note that Watkins and Leland Stanford were contemporaries. Watkins even photographed Stanford’s family, making this university a proud and apt home for these albums.”

The Albums

Photographs of the Yosemite Valley (1861 and 1865-1866)

In 1861, Watkins loaded up a team of mules with nearly a ton of photographic equipment including a mobile darkroom tent, a dangerous assortment of flammable chemicals, and an enormous custom-built camera that produced “mammoth” 18 x 22-inch glass-plate negatives. He headed 75 miles into the rugged and remote Yosemite Valley on a sometimes perilous journey to capture the natural wonders of the Sierra Nevada. The technical challenges of creating wet-plate negatives in the field were immense. Dust and grit could easily ruin the work as the plates were coated, exposed for up to an hour, and developed. Water had to be carried great distances. The sun warped and shrank camera parts. But the resulting suite of photographs became an international sensation – not only because they provided virtual access to one of America’s grandest wilderness areas but also for their extraordinary beauty. The New York Times declared in 1862 that “as specimens of the photographic art they are unequaled.”

Watkins’s album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley is sequenced to replicate the experience of entering the Mariposa Grove trail and traveling into the valley. From Cathedral Rocks to Half Dome, Watkins captures the quiet majesty of Yosemite’s natural monuments. The album contains images from both his initial expedition in 1861 and a subsequent visit as an ad hoc member of the California State Geological Survey team in 1865-66. Throughout his career, Watkins maintained close relationships with geologists as well as botanists who were deeply interested in his documentation of native tree species.

In Yosemite, Watkins found a spectacular natural laboratory for testing and refining his approach to landscape photography. His compositional choices were unique. In The Yosemite Valley from the “Best General View” (1866), for instance, Watkins cropped off the top of the lone tree in the foreground instead of framing it, lending a painterly quality to the image. By manipulating focus and perspective, Watkins also achieved an unusual balance of crispness against softer tonalities.

Watkins’s technical achievements under adverse conditions were unmatched and astonished his peers. The resolution of his photographs still rivals that of the high-end digital cameras of today. After 1861, capitalising on the success of his Yosemite pictures and his reputation as a landscape photographer, Watkins renamed his studio at 425 Montgomery Street in San Francisco the “Yo-Semite Gallery.” The exhibition features more than 30 photographs from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley including various views of Yosemite Valley; mountains and rock formations such as Cathedral Rocks, Half Dome, and El Capitan; waterfalls and water views such as Mirror Lake and Yosemite Falls; and photographs of Yosemite’s majestic trees.

Photographs of the Pacific Coast (1862-1876)

Watkins made his living mostly as a field photographer for hire, accepting commissions from logging companies and mining operations up and down the coast. Early in his career, Watkins’s photographs were often used to attract investors or as documentation in court evidence for land disputes. In the fast-developing West, photography was a means of establishing ‘truth claims’ to property and resource rights. And in a region where vast swaths of territory were rarely traveled by city dwellers, photography filled in the gaps.

Watkins added images from these underwritten trips to an album he called Photographs of the Pacific Coast. Along with his commercial photographs of smelting works at the New Almaden Mine in Santa Clara County and the hydraulic North Bloomfield mine in Nevada County, the album contains remarkable vistas of San Francisco including a dramatic photograph of the shipwreck Viscata on Ocean Beach, also images of the Devil’s Canyon geysers in Sonoma County and the Farallon Islands.

The album also includes images commissioned by California’s sixth governor, Milton Slocum Latham, of Latham’s mansion on San Francisco’s Rincon Hill. It was, in fact, Latham’s wife, Mollie, who commissioned the three albums now at Stanford. One of the original bindings is on display so visitors can appreciate its massive size and ornate details. With the Civil War raging in the eastern part of the country until 1865, Watkins’s images of the pristine Pacific Coast must have provided Americans a welcome alternative to the images of carnage issuing from the battlefield.

In the exhibition, there are more than 20 California photographs from the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast including scenes of San Francisco neighbourhoods, homes, and natural sites including the Farallon Islands; commissioned images of mining operations; and views of Mt. Shasta, Mendocino County, and Sonoma County.

Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon (1867 and 1870)

While Watkins’s name is most closely associated with Yosemite, photographers often cite Watkins’s album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon as his crowning artistic achievement. No longer a novice, Watkins demonstrates mastery of his craft and a keen eye for composition in these images. A friend at the Oregon Steam Navigation Company arranged for Watkins to travel by rail up and down the Columbia River to photograph the company’s rail portages and scenic beauty to document the company’s progress. Watkins was the first to photograph this area and traveled for four months to do so.

In the resulting views of Portland, Oregon City, rail portages, river industry, and scenery, Watkins made art of the river landscapes and the railroad laid alongside it. Cape Horn, Near Celilo (1867), taken at the final point of his journey where the tracks ended, shows a stark horizon, suggesting both the far edge of the world and the determination of early industrial pioneers. In Mt. Hood and the Dalles, Columbia River (1867), a spectacular view of Mt. Hood and of the meandering river at the base of basalt cliffs is disrupted by the object of greatest focus – a tiny white outbuilding for the railroad.

The exhibition features more than 15 photographs from the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon including views along the Columbia River of Cape Horn, Castle Rock and Mt. Hood; and images of Portland, Oregon City, and smaller towns and industries along the railroad.

Exploring Watkins’s Photographs with Digital Technology

Stanford’s Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis, the Bill Lane Center for the American West, the Branner Earth Sciences Library, and the Cantor worked together to create an innovative cartographic digital accompaniment for each album.

For Photographs of Yosemite Valley, the team – including select students – generated “viewsheds” of several of Watkins’s photographs that enable visitors to see where each was likely taken and what topographical elements are either illuminated or obscured in them. With Photographs of the Pacific Coast, fascinating before-and-after visualisations illustrate the incredible changes in the landscape of San Francisco over the last century and a half. Lastly, a cartographic accompaniment to Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon details the early railroad routes Watkins traveled to take his photographs.

Carleton Eugene Watkins (1829-1916)

Born in upstate New York in 1829, Watkins ventured west to look for opportunities and settled in the Bay Area in 1852. While working for a photography studio, he was asked to step in for a photographer who had unexpectedly quit. Watkins quickly learned the daguerreotype process and within two years he was making ambrotypes and wet-plate collodion photographs.

Throughout his career, Watkins documented the remote American West, generating more than 7,000 photographs of its most majestic wilderness sites as well as the dramatic transformation of isolated territories caused by logging and mining industries. His photographs won awards throughout the United States and abroad. With his early success, he established a gallery in San Francisco on prestigious Montgomery Street in 1861.

But Watkins’s fortunes took a turn with the 1874 failure of the Bank of California and the resulting economic panic. Heavily in debt at the time, Watkins had to declare bankruptcy and lost both the gallery and the majority of his negatives to a competitor. Watkins rebuilt his inventory, continuing to travel and work into the 1890s, but never recovered financially. At one point he and his family lived in a rail car in Oakland. Watkins’s health also declined, and by 1903 he was nearly blind. Watkins died tragically. The 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed his studio and his life’s work, and he never got over the shock. His family eventually had him committed to Napa State Hospital. He died there in 1916.

Press release from the Cantor Arts Center website

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Cape Horn, Columbia River

1867

From the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Arch at the West End, Farallones

1868-1869

From the album Photographs of the Pacific Coast

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Multnomah Falls, Columbia River, Oregon

1867

From the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Multnomah Falls, Cascades, Columbia River

1867

From the album Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Pohono, the Bridal Veil, Yosemite 900 ft.

1865-1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

The Lower Yosemite Fall, Yosemite

1865-1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

The Yosemite Falls, 2634 ft.

1865-1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Mirror View of El Capitan, Yosemite

1865-1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Washington Column, 2082 ft., Yosemite

1865-1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

The Ponderosa, Yosemite

1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print

Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Section of the Grizzly Giant, 33 ft. diameter

1865-1866

From the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Albumen print. Lent by Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University

328 Lomita Drive at Museum Way

Stanford, CA 94305-5060

Phone: 650-723-4177

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Sunday 11am – 5pm

Closed Monday and Tuesday

![Neo Rauch (German, b. 1960) 'Goldgrube' [Goldmine] 2007 Neo Rauch (German, b. 1960) 'Goldgrube' [Goldmine] 2007](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/22_neo_rauch_goldgrube-web.jpg)

![Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669) 'Sogenannter Faust' [Allegedly Faust] c. 1651‑1653 Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669) 'Sogenannter Faust' [Allegedly Faust] c. 1651‑1653](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/12_rembrandt_sogenannter_faust-web.jpg?w=650&h=854)

![Yves Klein (French, 1928-1962) 'Relief éponge bleu (RE 18)' (blue sponge relief [re 18]) 1960 Yves Klein (French, 1928-1962) 'Relief éponge bleu (RE 18)' (blue sponge relief [re 18]) 1960](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/16_klein_schwammrelief-web.jpg?w=650&h=976)

You must be logged in to post a comment.