Exhibition dates: 23rd February – 7th June 2024

Curators: Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich

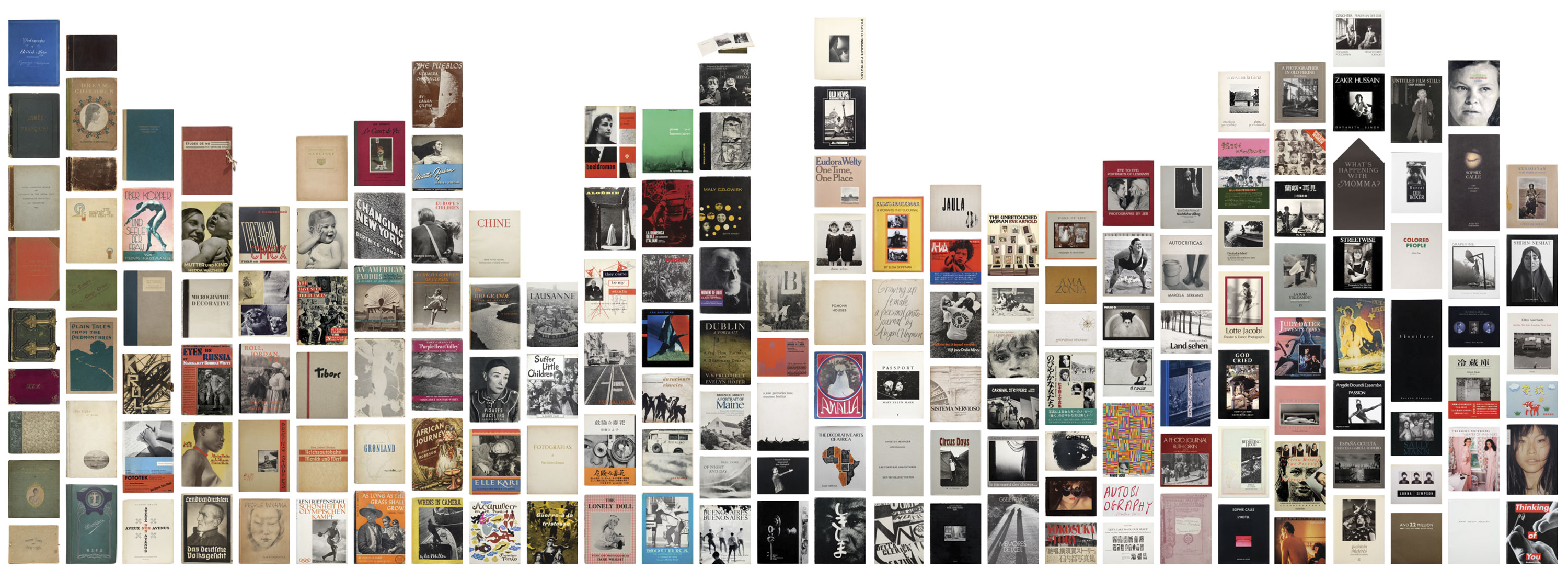

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999 (Nueva York, 10×10 Photobooks, 2021) cover images

Design: Ayumi Higuchi

Photography: Jeff Gutterman

A mid-week posting!

I wouldn’t have forgiven myself if I had missed this important exhibition about an interesting subject, the “underexposed and undocumented photobooks by women made between 1843 and 1999.”

So I thought I would squeeze it into the posting schedule which stretches a couple of months into the future…

Other than the group photographs of the book covers and installation photographs of the exhibition (below), there were no individual book covers nor details about some of the books in the media images, so I have added a few were it has been possible along with accompanying text.

I have also included photographs from what I think is one of the most iconic photobooks, even though I am not sure it is in the exhibition: Marion Palfi’s There is No More Time: An American Tragedy (1949).

So many important photobooks by so many glorious photographers.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

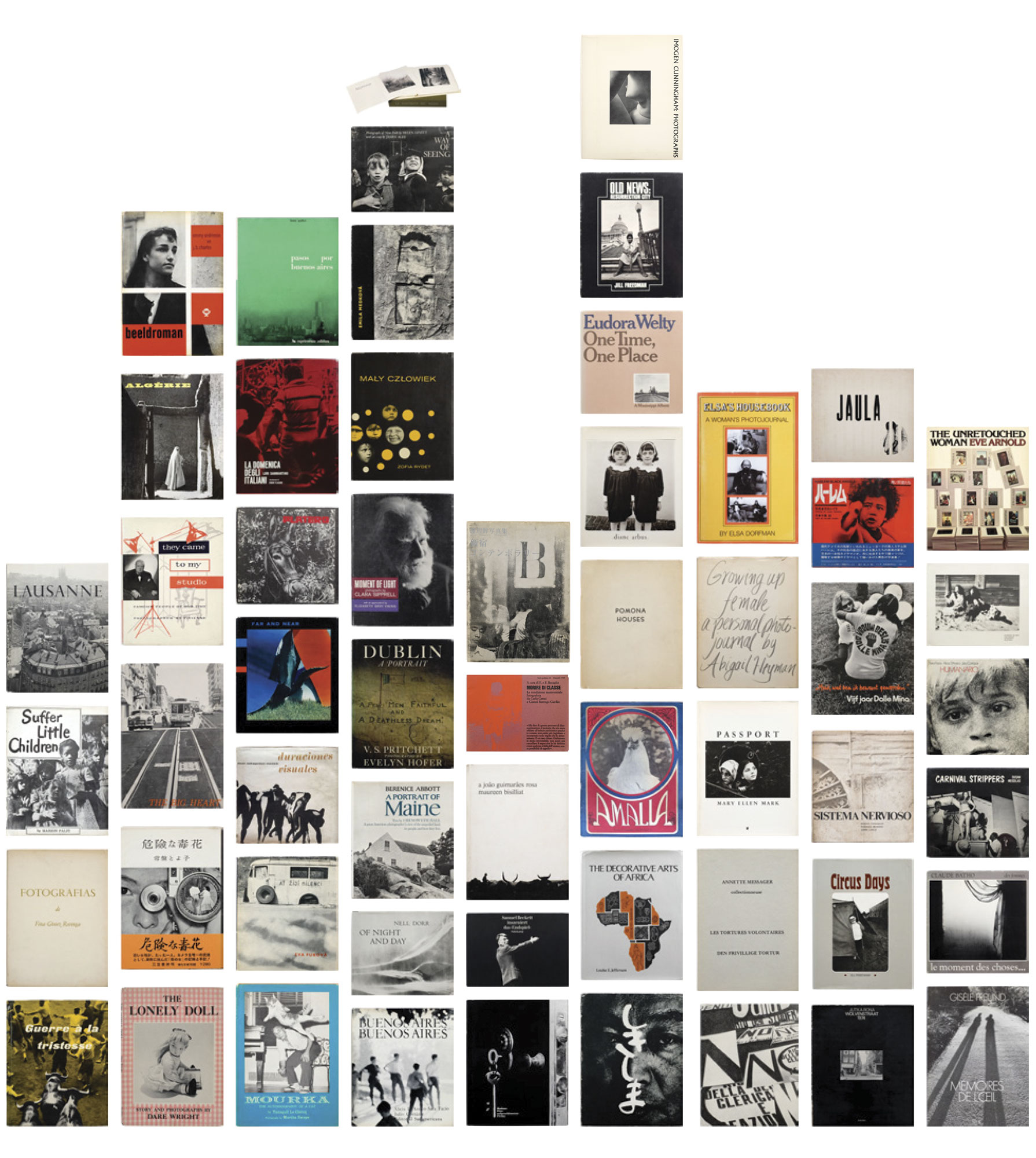

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999 (Nueva York, 10×10 Photobooks, 2021) cover images (detail)

Design: Ayumi Higuchi

Photography: Jeff Gutterman

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999 (Nueva York, 10×10 Photobooks, 2021) cover images (detail)

Design: Ayumi Higuchi

Photography: Jeff Gutterman

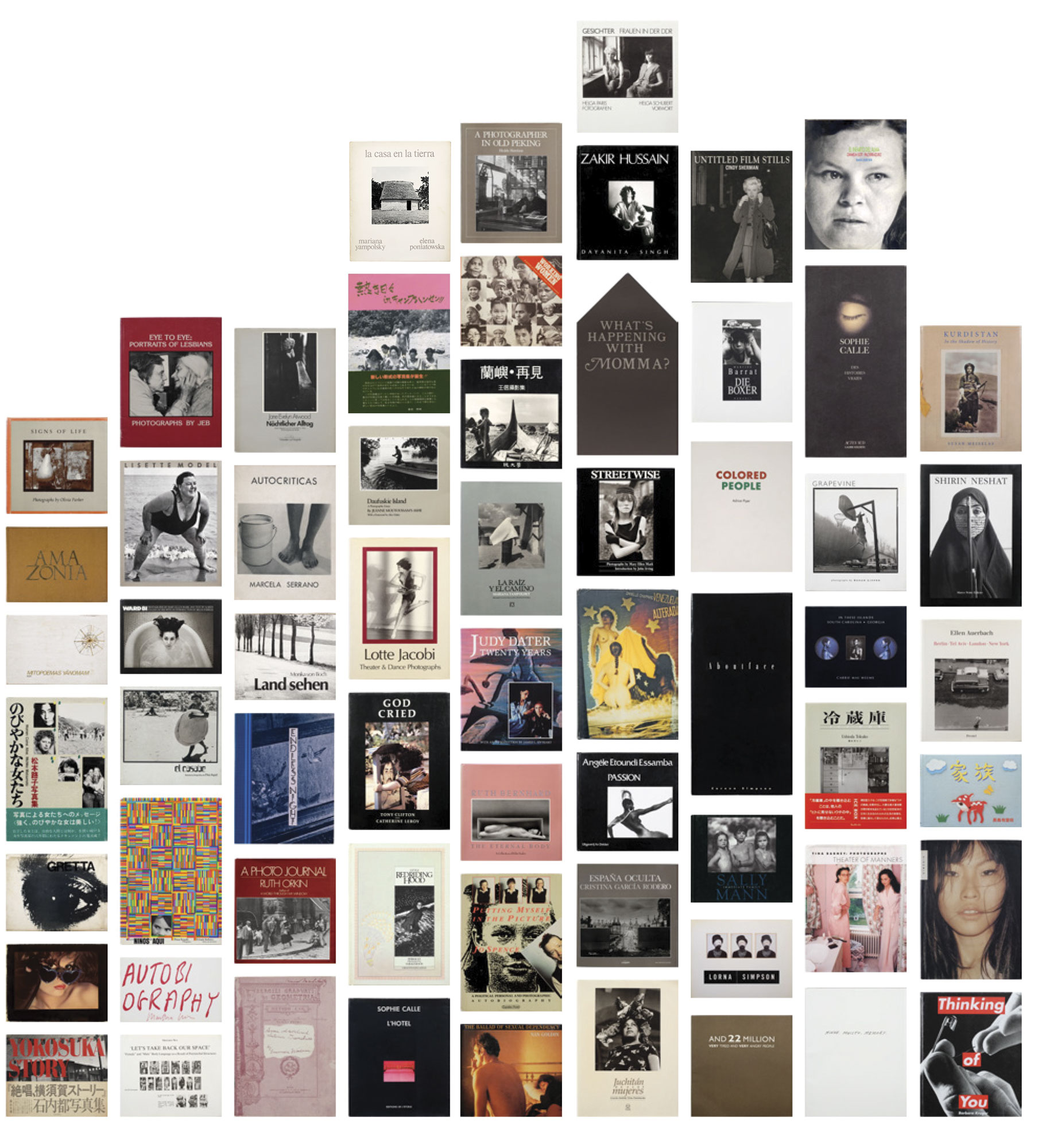

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999 (Nueva York, 10×10 Photobooks, 2021) cover images (detail)

Design: Ayumi Higuchi

Photography: Jeff Gutterman

What They Saw project, a touring exhibition accompanied by a publication and series of public programs, is a means to ignite interest in underexposed and undocumented photobooks by women made between 1843 and 1999 and to begin a process of filling in the gaps. The present show is organised in collaboration with 10×10 Photobooks, a nonprofit organisation with a mission to share photobooks globally and encourage their appreciation and understanding.

In seeking out the omissions in photobook history, the standard definition of the photobook: a bound volume with photographic illustrations published by the author, an independent publisher or a commercial publisher, needed to be expanded to incorporate those who do not call themselves photographers or artists but who nevertheless put together a “book” composed of photographs taken by themselves or others: individual albums, slim exhibition pamphlets, scrapbooks, mock-ups, fanzines and artists’ books to be more inclusive.

This iteration of the What They Saw exhibition includes 60 books of the more than 250 volumes highlighted in the associated publication. Most of these publications are from the collection of the Museo Reina Sofía’s Library and Documentation Centre. They are presented chronologically and show examples of books from around the globe. From the pioneers, such as Anna Atkins, who was the first person ever to print and distribute a photobook, or Isabel Agnes Cowper, who used photography to document museum objects, subsequently reproduced in numerous books, to the independent and self-published photobooks of the 1990s, including Colored People: A Collaborative Book Project by Adrian Piper or Twinspotting by Ketaki Seth, this selection allows for greater inclusion of previously marginalised photographic communities, including women, queer communities, people of colour and artists from outside Europe and North America.

Although only twenty-five years old, photobook history has been written primarily by men and has focused on publications authored by men. Very few books by women photographers appear in past anthologies documenting photobook history, and those included are already quite well known. This exhibition of women’s role in the production, dissemination, and authoring of photobooks is a necessary step in unwriting the current photobook history and rewriting an updated photobook history that is more equitable and inclusive.

Text from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía website

Anna Atkins, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1843

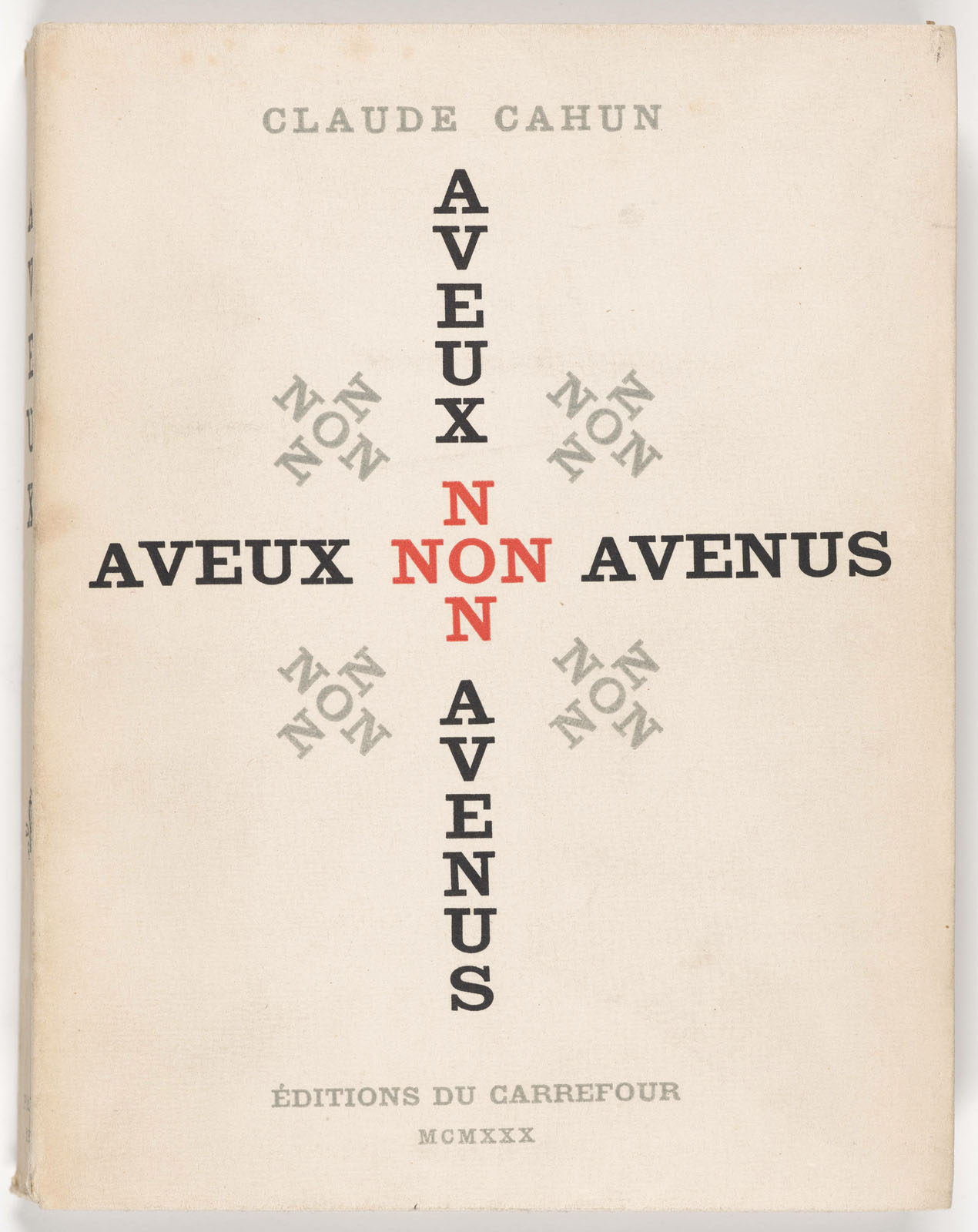

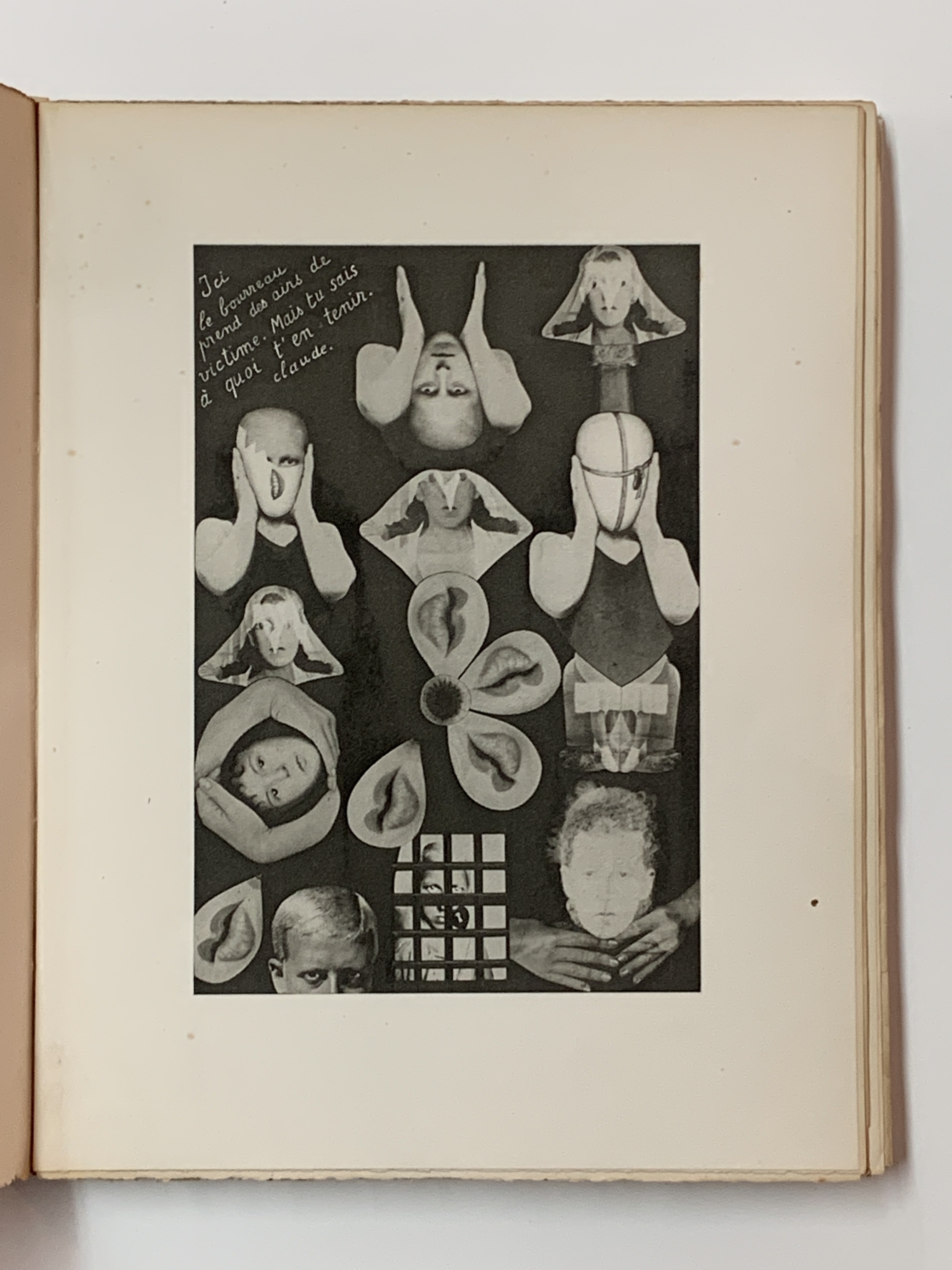

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) (French, 1894-1954) Aveux non avenus (Disavowals or Cancelled Confessions) 1930

In her 1930 publication, Aveux non Avenus, Claude Cahun used the relationship between her inwardly focused poetic writing and symbolic photomontages to construct a unique reality for self-expression. This article focuses on three chapters and respective photographic images from the publication to relate Cahun’s, and by association her partner Marcel Moore’s, discussion on sexuality and gender expression. The utopian dreamscape created investigates issues of narcissism and otherness, female homosexuality, dandyism and going beyond gender, individual and social critique, mocking the antiquated views of art and writing, accepting and breaking taboos, while allowing for other departures from the accepted norm. Through analysis of the publication and supporting evidence from early influences, it can be seen that Cahun created a world in Aveux non Avenus where she could exist in a space between the established feminine–masculine binary of 20th-century Europe.

Abstract from Erin F. Pustarfi. “Constructed Realities: Claude Cahun’s Created World in Aveux Non Avenus,” in Journal of Homosexuality, 67(5), pp. 697-711

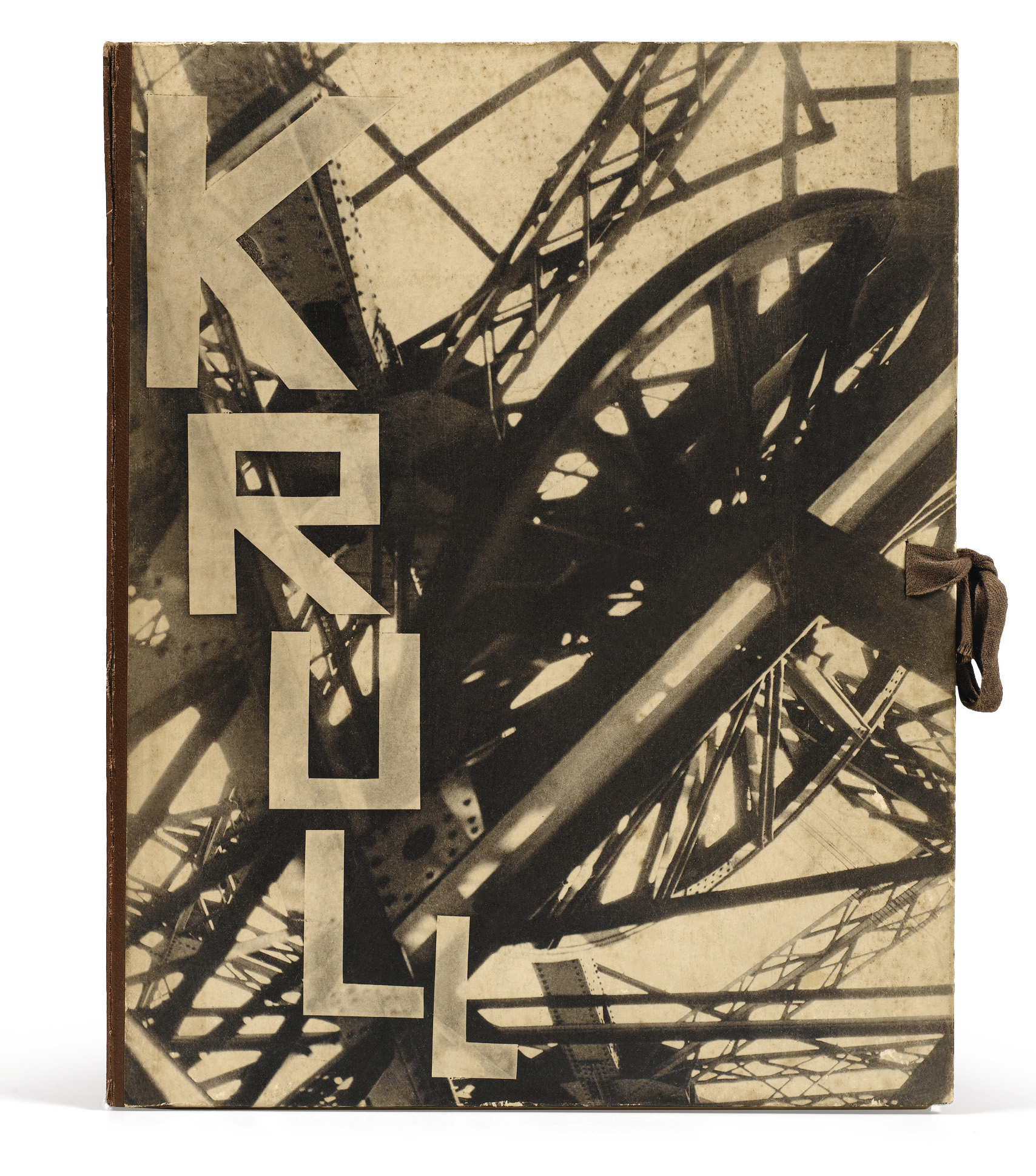

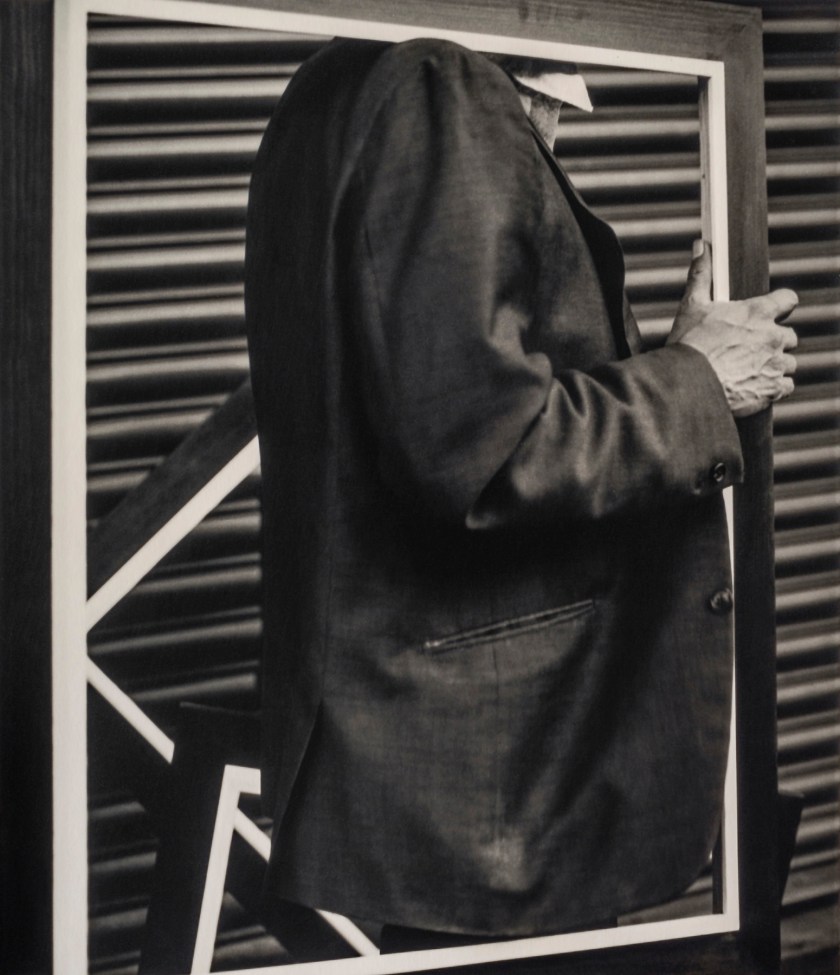

Germaine Krull (photographer) Cover design by M. Tchimoukow. MÉTAL cover 1928

Germaine Krull (1897-1985) Image from the portfolio MÉTAL 1928, p. 33

I did not have a special intention or design when I took the Iron photographs. I wanted to show what I see, exactly as the eye sees it. ‘MÉTAL’ is a collection of photographs from the time. ‘MÉTAL’ initiated a new visual era and open the way or a new concept of photography. ‘MÉTAL’ was the starting point which allowed photography to become an artisanal trade and which made an artist of the photographer, because it was part of this new movement, of this new era which touched all art.

Germaine Krull. Extract from the Preface to the 1976 edition of ‘MÉTAL’

See my writing on Germaine Krull’s portfolio MÉTAL.

Germaine Krull (1897-1985) Image from the portfolio MÉTAL 1928 p. 37

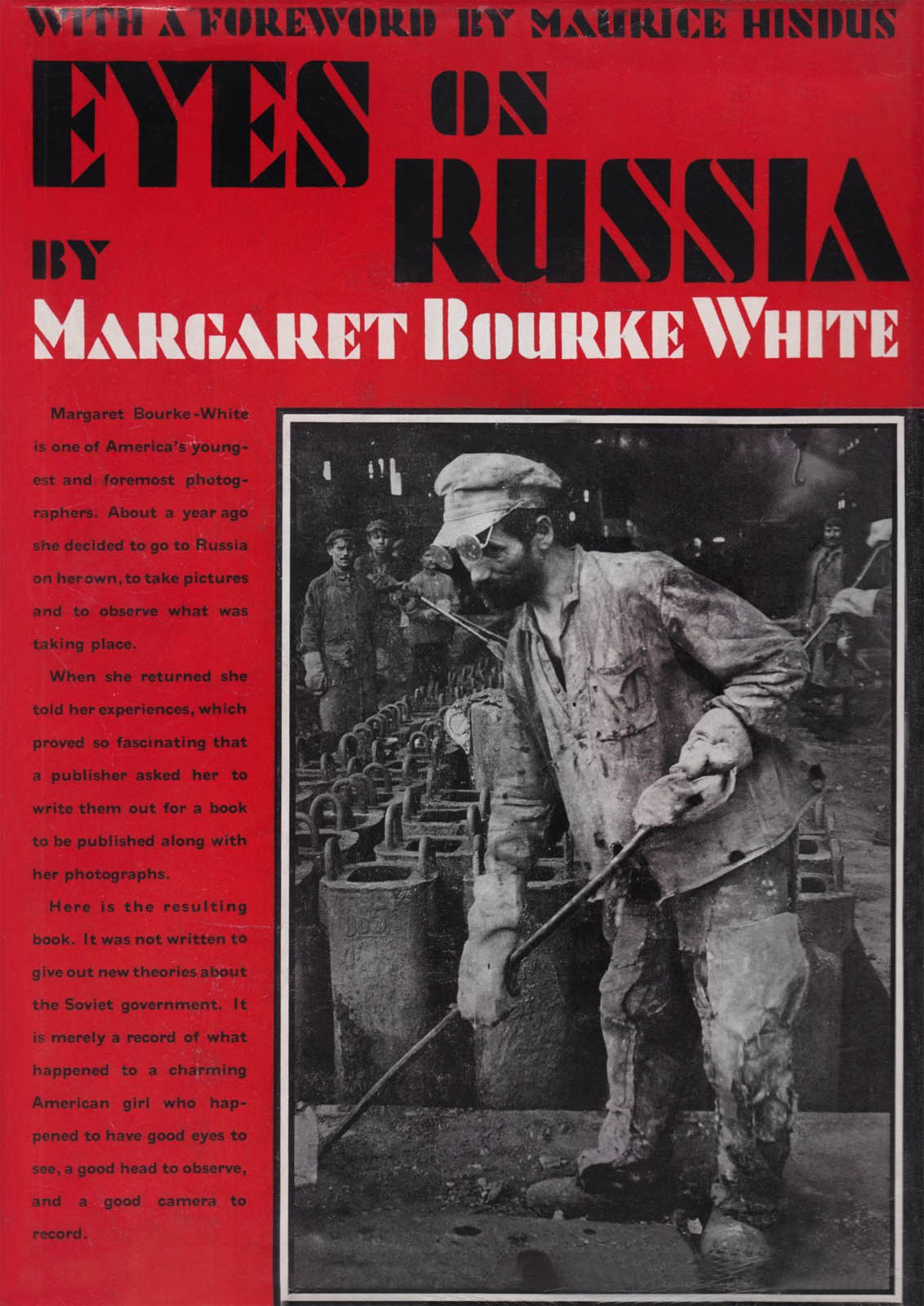

Eyes on Russia by Margaret Bourke-White. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1931

In 1951, Westbrook Pegler wrote numerous articles attacking Margaret Bourke-White for her associations with leftist politics in the 1930s. It is probably for this reason that in her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, written about ten years later, Bourke-White didn’t mention her first book, Eyes on Russia, published in 1931. And yet, this book is of extraordinary interest, not only as a landmark in Bourke-White’s career but also as a source, both visual and narrative, on the Soviet Union during its first Five Year Plan. With letters of recommendation from influential people, including the Russian film maker, Sergei Eisenstein, Bourke-White arrived in Moscow in the fall of 1930, where she obtained the official endorsement of A.B. Khalatoff, chief of the Soviet publishing house (he was later liquidated in the 1937 purges). Khalatoff supplied her with a thick roll of rubles and a guide. Bourke-White then toured some of the most important industrial and other sites and came back with stellar images of Russia under construction, which she complemented by a spritely and charming narrative of her experiences as the first foreign photographer to photograph in the Soviet Union with official permission. On her trip, she made 800 negatives, of which 40 were published in Eyes on Russia in a sepia tone. This book, along with at least eight related illustrated articles in Fortune, the New York Times Sunday Magazine, and other periodicals, significantly enhanced Bourke-White’s reputation (and commercial business). They also helped initiate relationships she established both with Soviet officials and Americans sympathetic to the U.S.S.R. She returned to Russia in 1931 and 1932 for additional photography, but Eyes on Russia, a fascinating book for a variety of reasons, remains the largest single published collection of her work in that country. It was very well received in numerous book reviews when it appeared. For a more detailed review, see my article, Gary D. Saretzky “Margaret Bourke-White: Eyes on Russia,” The Photo Review, 22: 3-4 (Summer & Fall 1999),

Text from a comment on the Amazon website

Roll, Jordan, Roll by Julia Peterkin (text) and Doris Ulmann (photographs) New York: Robert O. Ballo, 1933

Doris Ulmann’s photographic collaboration with Julia Peterkin focuses on the lives of former slaves and their descendants on a plantation in the Gullah coastal region of South Carolina. Peterkin, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1929, was born in South Carolina and raised by a black nursemaid who taught her the Gullah dialect before she learned standard English. She married the heir to Lang Syne in today’s Calhoun County, SC, one of the state’s richest plantations, which became the setting for Roll, Jordan, Roll. Ulmann’s soft-focus photos-rendered as tactile as charcoal drawings in the superb gravure reproductions here-straddle Pictorialism and Modernism even as they appear to dissolve into memory.

Text from the Amazon website

Leni Riefenstahl Schönheit im olympischen Kampf [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937)

Leni Riefenstahl Schönheit im olympischen Kampf [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937) pp. 220-221

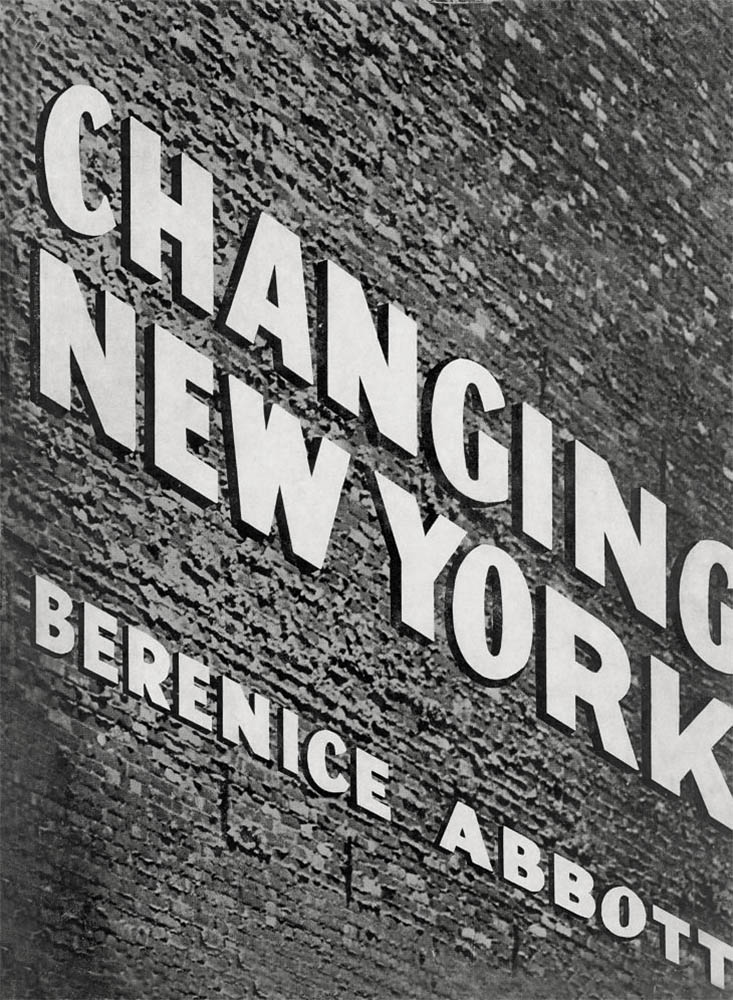

Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland. Changing New York. New York: E. P. Dutton & Company, 1939

“The camera alone can catch

the swift surfaces of the

cities today and speaks a

language intelligible to all.”

~ Berenice Abbott

Abbott’s landmark work on New York, illustrated with 97 halftone plates that display “the historical importance of the documentary model its power as a medium of personal expression” (Parr & Badger).

In January 1929, after eight years in Europe, Abbott boarded an ocean liner to New York City for what was meant to be a short visit. Upon arrival, she was struck by the rapid transformation of the built landscape and saw the city as ripe with photographic potential. “When I saw New York again, and stood in the dirty slush, I felt that here was the thing I had been wanting to do all my life,” she recalled. “Old New York is fast disappearing,” Abbott observed. “At almost any point on Manhattan Island, the sweep of one’s vision can take in the dramatic contrasts of the old and the new and the bold foreshadowing of the future. This dynamic quality should be caught and recorded immediately in a documentary interpretation of New York City. The city is in the making and unless this transition is crystallised now in permanent form, it will be forever lost…. The camera alone can catch the swift surfaces of the cities today and speaks a language intelligible to all.”

On the eve of the Great Depression, she began a series of documentary photographs of the city that, with the support of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project from 1935 to 1939, debuted in 1939 as the traveling exhibition and publication Changing New York.

With a handheld camera, Abbott traversed the city, photographing its skyscrapers, bridges, elevated trains, and neighbourhood street life. She pasted these “tiny photographic notes” into a standard black-page album, arranging them by subject and locale.

Consisting of 266 small black-and-white prints arranged on thirty-two pages, Abbott’s New York album marks a key turning point in her career – from her portrait work in Paris to the urban documentation that became one of her lasting legacies.

From 1935 to 1965, Berenice Abbott and art critic Elizabeth McCausland (1899-1965) lived and worked in two flats they shared on the fourth floor of the loft building at 50 Commerce Street.

Lannyl Stephens. “Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York,” on the Village Preservation website July 17, 2023 [Online] Cited 26/05/2024

Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland. Changing New York. New York: E. P. Dutton & Company, 1939

An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion. Photographs by Dorothea Lange; text by Paul Taylor. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1939

“We need to be reminded these days about what women have been, and can be. It’s a question of their really deep and fundamental place in society. I have a feeling that women need to be reminded of it. They are needed.”

~ Dorothea Lange

First published in 1939, An American Exodus is one of the masterpieces of the documentary genre. Produced by incomparable documentary photographer Dorothea Lange with text by her husband, Paul Taylor, An American Exodus was taken in the early 1930s while the couple were working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) The book documents the rural poverty of the depression-era exodus that brought over 300,000 migrants to California in search of farm work, a westward mass migration driven by economic deprivation as opposed to the Manifest Destiny of 19th century pioneers.

Text from the Google Books website

In 1938, Dorothea Lange and her husband Paul Taylor began sorting through the stacks of photographs she had made documenting migrant farmworkers and homeless drought refugees. Their goal was to create a book that would reveal the human dimension of the crisis to the American people and, hopefully, prompt government relief. One of several books released in the late 1930s that made use of the Farm Security Administration photo archive, An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion was innovative in several ways. Rather than tell the story from their own perspective, Lange and Taylor used direct quotes from the migrants themselves, which Lange had painstakingly collected in the field. Released as war tensions were building in Europe and Asia, An American Exodus was largely overlooked at the time. In the years since its publication, the book has gained power, presenting an iconic image of the Dust Bowl era that has shaped the way we think of those difficult years.

Text from the Dorothea Lange Digital Archive, Oakland Museum of California website

Eslanda Goode Robeson. African Journey. New York: John Day Company, 1945

Eslanda Robeson’s 1936 African journal with her own photographs. Africa seen through the eyes of an African American. She went to South Africa, Kenya, Uganda, and Congo, and visited African kings and British governors, villages, gold mines, plantations, herdswomen, and modern African leaders.

Eslanda Goode Robeson (1895-1965) was an American anthropologist, author, actress, and civil rights activist. She was born in Washington, D.C., graduated from Columbia University in 1917 with a degree in chemistry, and in 1921 married the singer and actor Paul Robeson. In 1936, she received her degree in anthropology from the London School of Economics, and in 1946, the year following the publication of African Journal, earned her anthropology Ph.D. from Hartford Seminary where she specialised in African studies and race relations.

Text from the Boyd Books website

Wrens in Camera by Lee Miller (London: Hollis and Carter, 1945)

During the Second World War Lee Miller was the official war photographer for Vogue magazine. The images contained in Wrens in Camera were commissioned by the Admiralty and show the female navy officers and workers fulfilling their war duties. There are signallers, technicians, trainers, housekeepers and transport crews. The whole is an important document of women’s roles in war-time Britain.

Text from the Beaux Books website

Wrens in Camera by Lee Miller (London: Hollis and Carter, 1945) p. 47

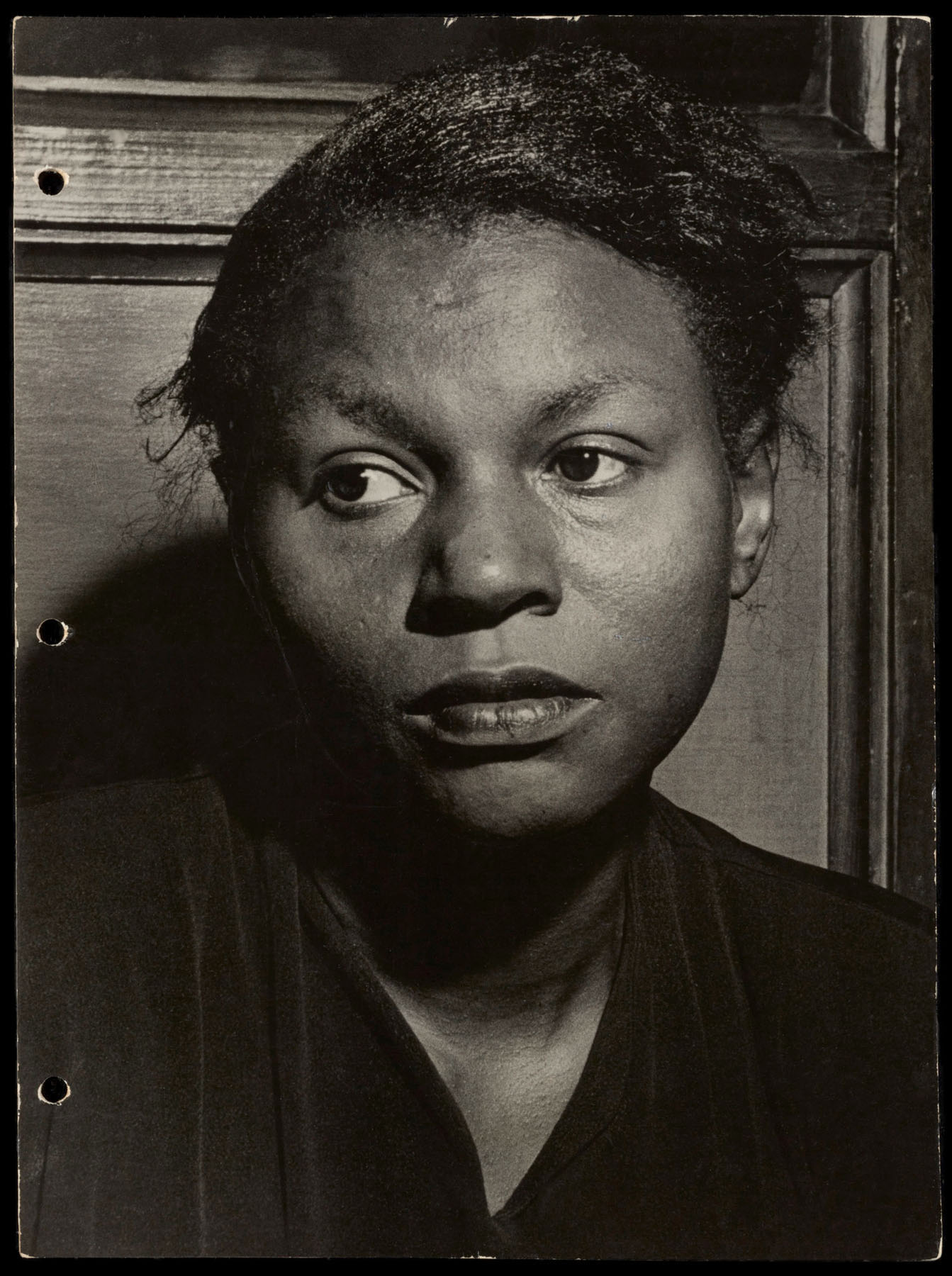

Marion Palfi (American born Germany, 1907-1978)

Untitled (Black woman with a white child)

1949

From the book There Is No More Time: An American Tragedy

Marion Palfi/Center for Creative Photography

© All Rights Reserved

Marion Palfi (American born Germany, 1907-1978)

Untitled (Portrait of Mrs. Caleb Hill, widow of a lynching victim)

1949

From the book There Is No More Time: An American Tragedy

Marion Palfi/Center for Creative Photography

© All Rights Reserved

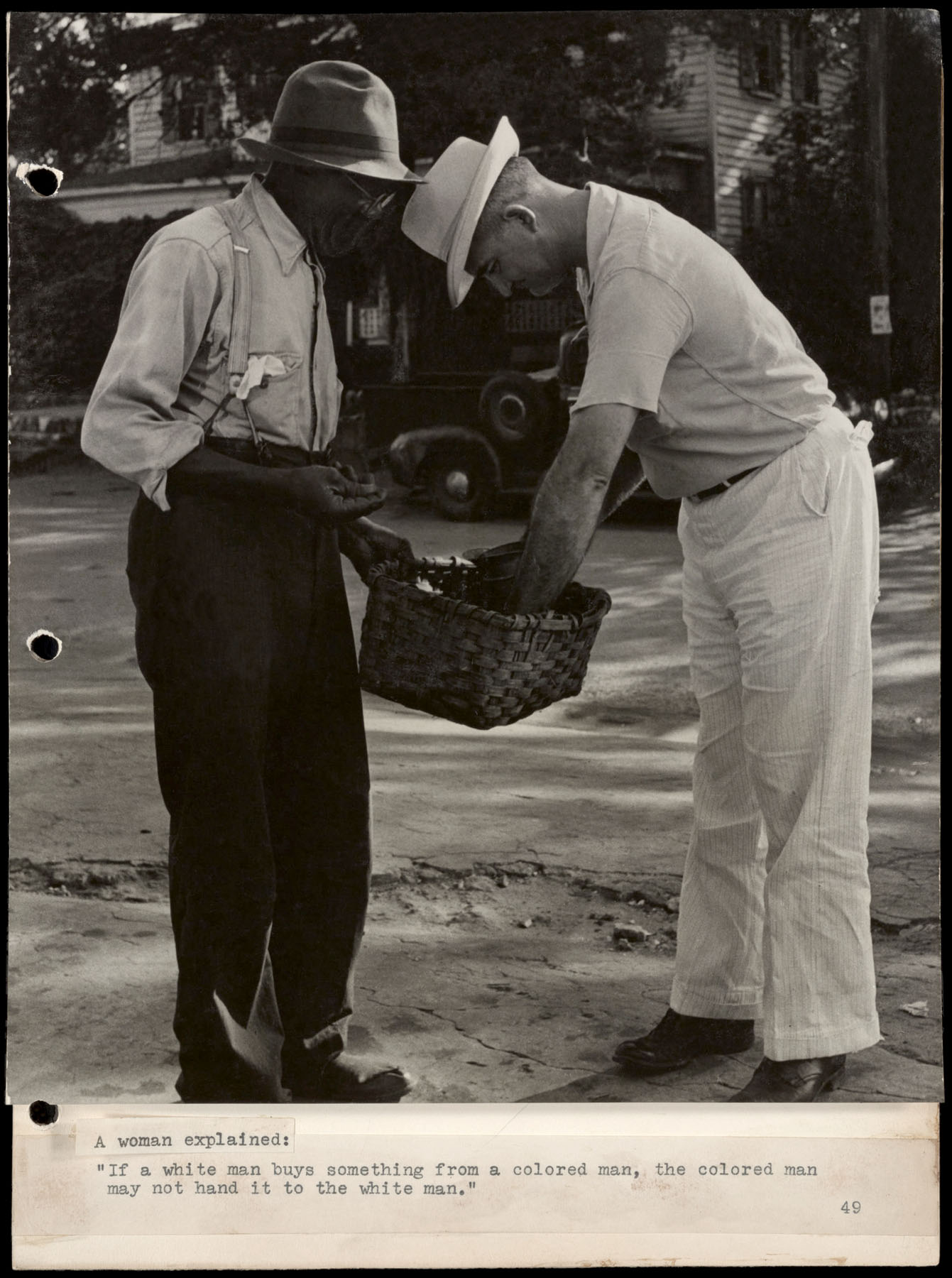

“As a photographer, she was as interested in the discriminator as in the victims of discrimination. Long before what we tend to think of as the crux of the civil rights struggle in the 1960s, Palfi went to Georgia at a particularly dangerous time. In 1949, she was drawn to do an in-depth portrait of Irwinton, a small community where a young black man had been torn out of jail and shot by a lynch mob. The tremendous public outcry over this barbaric incident included front-page coverage and editorials by the New York Times. Obviously, the presence of a photographer in such a community would attract unwanted attention and might have endangered her life. But by a happy stroke of luck, the Vice-President of the Georgia Power Company was interested in her work. Warning her that she must “photograph the South as it really is, not as the North slanders it,” he wanted her to get to meet the “right” people. As it happened, the “right” people turned out to be the very discriminators she wanted to photograph. Left in the protection of the local postmistress, she proceeded to take terms, objective pictures of overseers and white-suited politicians.

Even if the press had not indicted Irwinton for its racism, the extreme conservatism and tension were evident in the faces of its citizens. She found a white supremacist group, “The Columbians,” whose insignia was a thunderbolt, the symbol of Hitler’s elite guard. “Mein Kampf was their bible,” she believed. Meanwhile, the wife of the lunch victim said, simply, “Caleb was a good man … he believed in his rights and therefore he died.”

Elizabeth Lindquist-Cock. “Marion Palfi: An Appreciation,” in The Archive Research Series Number 19, September 1983, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, pp. 7-8.

Marion Palfi (American born Germany, 1907-1978)

Untitled (A woman explained: “If a white man buys something…”)

1949

From the book There Is No More Time: An American Tragedy

Marion Palfi/Center for Creative Photography

© All Rights Reserved

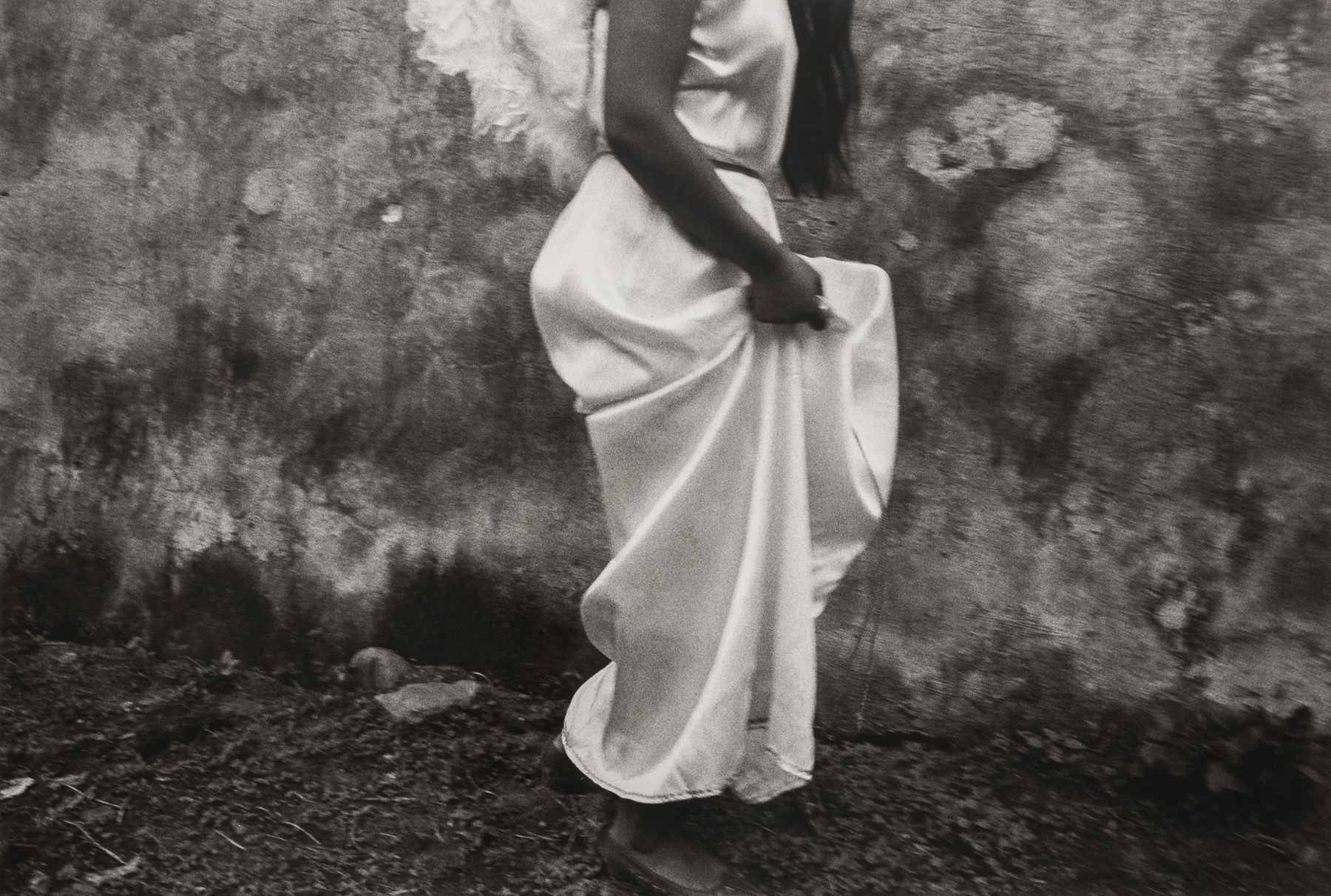

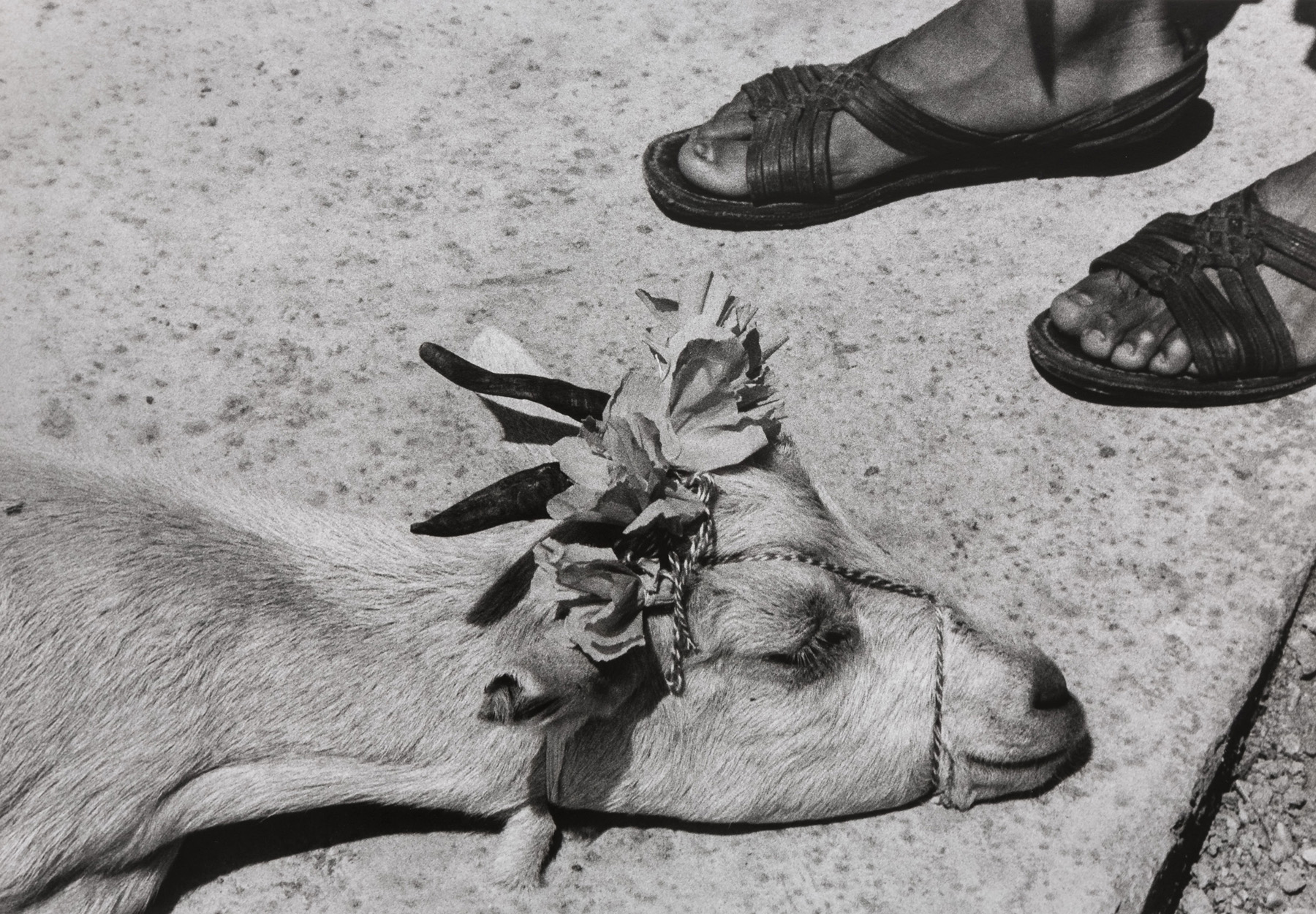

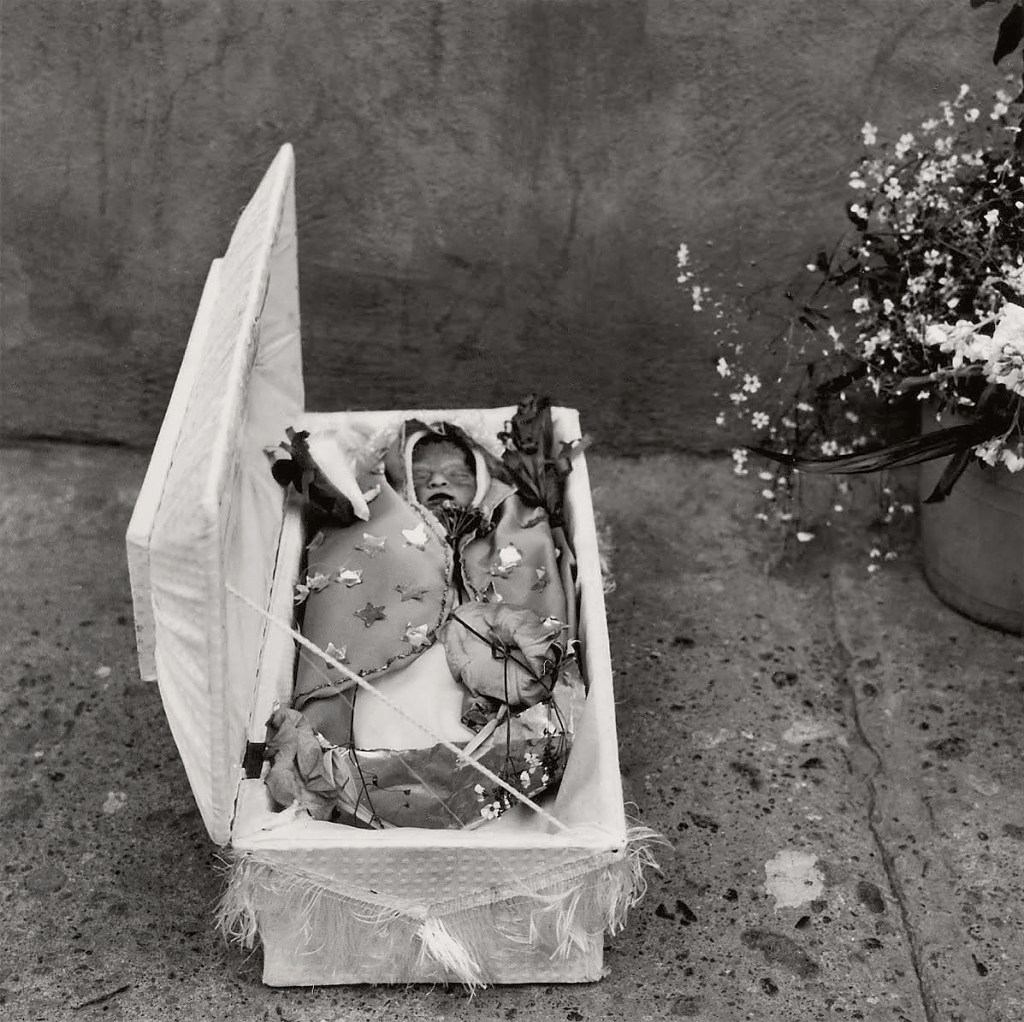

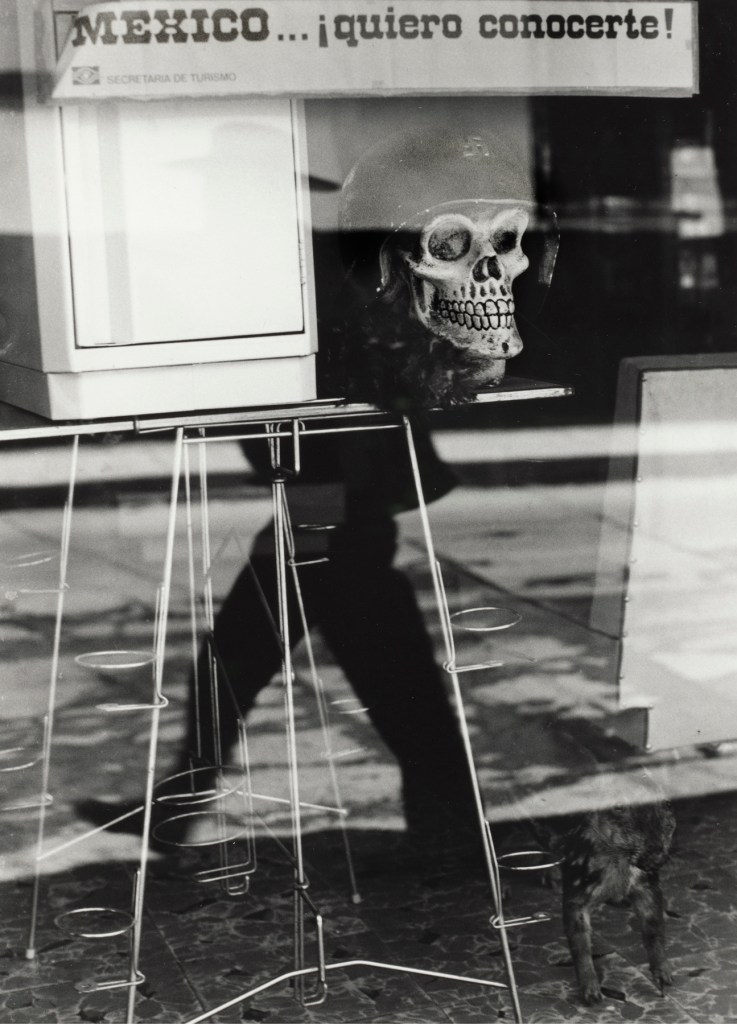

Acapulco en el sueño by Francisco Tario (text) with photographs by Lola Alvarez Bravo, 1951

“If my photographs have any meaning, it’s that they stand for a Mexico that once existed.”

~ Lola Alvarez Bravo

Dare Wright. The Lonely Doll. New York: Doubleday & Co, 1957

Once there was a little doll. Her name was Edith. She lived in a nice house and had everything she needed except someone to play with. She was lonely! Then one morning Edith looked into the garden and there stood two bears! Since it was first published in 1957, The Lonely Doll has established itself as a unique children’s classic. Through innovative photography Dare Wright brings the world of dolls to life and entertains us with much more than just a story. Edith, the star of the show, is a doll from Wright’s childhood, and Wright selected the bear family with the help of her brother. With simple poses and wonderful expressions, the cast of characters is vividly brought to life to tell a story of friendship.

Text from the Amazon website

Mourka, the autobiography of a Cat, by Tanaquil Le Clercq and Martha Swope. Stein and Day 1964

Le Clercq is the wife of choreographer George Balanchine; she wrote this book after Mourka became famous because of the photograph of Martha Swope in Life magazine, where George Balanchine assists Mourka in his grand jeté. Mourka writes about his exercises in dance and his aspirations to travel in outer space.

Text from the Cats in Books albums Facebook page

Mourka, the autobiography of a Cat, by Tanaquil Le Clercq and Martha Swope. Stein and Day 1964

A Way of Seeing, 1965. Photographs by Helen Levitt

Dublin: A Portrait by V.S. Pritchett (text) and Evelyn Hofer (photographs). New York: Harper & Row, 1967

The starting point for this book is Evelin Hofer’s Dublin: A Portrait, which features an in-depth essay by V. S. Pritchett and photos by Hofer, and enjoyed great popularity upon its original publication in 1967. Dublin: A Portrait is an example of Hofer’s perhaps most important body of work, her city portraits: books that present comprehensive prose texts by renowned authors alongside her self-contained visual essays with their own narratives. Dublin: A Portrait was the last book published in this renowned series. …

In Dublin Hofer repeatedly turned her camera to sights of the city, but mainly to the people who constituted its essence. She made numerous portraits – be they of writers and public figures or unknown people in the streets. Her portraits give evidence of an intense, respectful engagement with her subjects, who participate as equal partners in the process of photographing.

Text from The Eye of Photography Magazine website

Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, 1972

When Diane Arbus died in 1971 at the age of forty-eight, she was already a significant influence-even something of a legend-among serious photographers, although only a relatively small number of her most important pictures were widely known at the time. The publication of Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph in 1972 – along with the posthumous retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art – offered the general public its first encounter with the breadth and power of her achievements. The response was unprecedented.

The monograph of eighty photographs was edited and designed by the painter Marvin Israel, Diane Arbus’s friend and colleague, and by her daughter Doon Arbus. Their goal in making the book was to remain as faithful as possible to the standards by which Diane Arbus judged her own work and to the ways in which she hoped it would be seen. Universally acknowledged as a classic, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph is a timeless masterpiece with editions in five languages and remains the foundation of her international reputation.

Nearly half of a century has done nothing to diminish the riveting impact of these pictures or the controversy they inspire. Arbus’s photographs penetrate the psyche with all the force of a personal encounter and, in doing so, transform the way we see the world and the people in it.

Text from the Fraenkel Gallery Shop website

Jill Freedman. Circus Days. New York: Harmony Books/Crown, 1975

A photographic documentation of the Beatty-Cole Circus, recording and portraying the customs, activities, animals, and singular personalities of an endangered way of life.

Jill Freedman. Circus Days. New York: Harmony Books/Crown, 1975

Susan Meiselas. Carnival Strippers book cover 1975

From 1972 to 1975, Susan Meiselas spent her summers photographing women who performed striptease for small-town carnivals in New England, Pennsylvania and South Carolina. As she followed the shows from town to town, she captured the dancers on stage and off, their public performances as well as their private lives, creating a portrait both documentary and empathetic: “The recognition of this world is not the invention of it. I wanted to present an account of the girl show that portrayed what I saw and revealed how the people involved felt about what they were doing.” Meiselas also taped candid interviews with the dancers, their boyfriends, the show managers and paying customers, which form a crucial part of the book.

Meiselas’ frank description of these women brought a hidden world to public attention, and explored the complex role the carnival played in their lives: mobility, money and liberation, but also undeniable objectification and exploitation. Produced during the early years of the women’s movement, Carnival Strippers reflects the struggle for identity and self-esteem that characterised a complex era of change.

Text from the Booktopia website [Online] Cited 22/04/2022

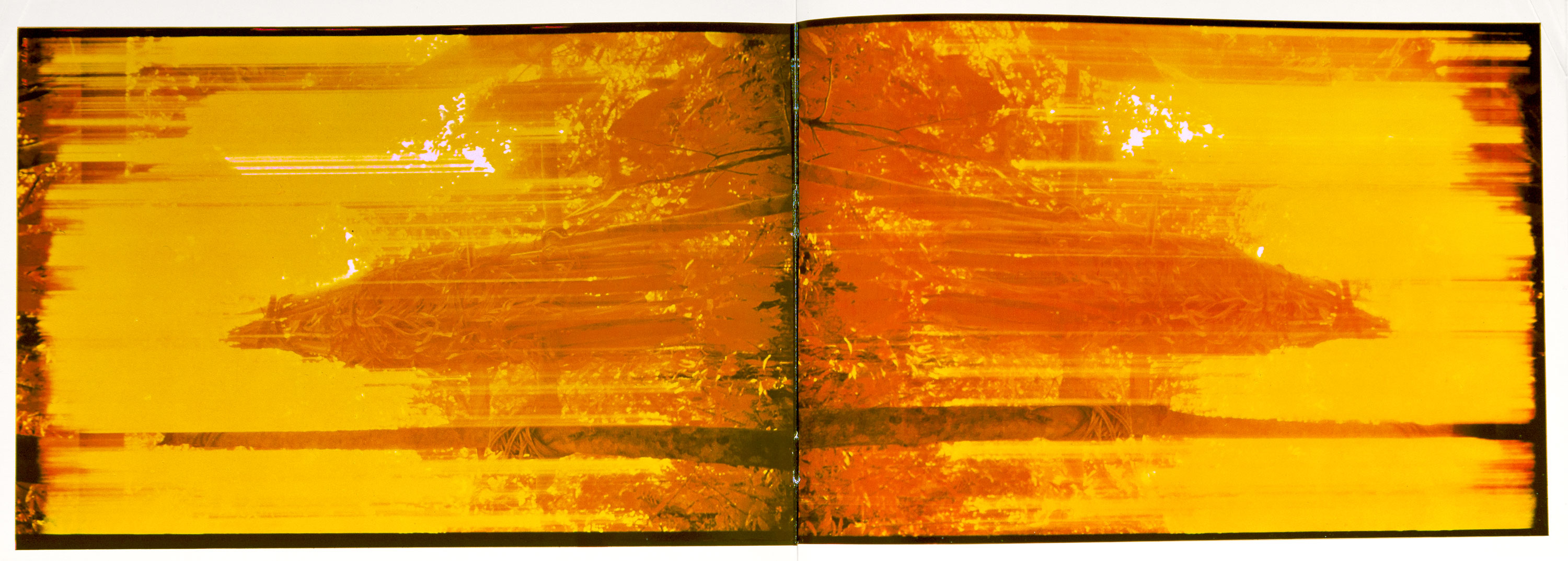

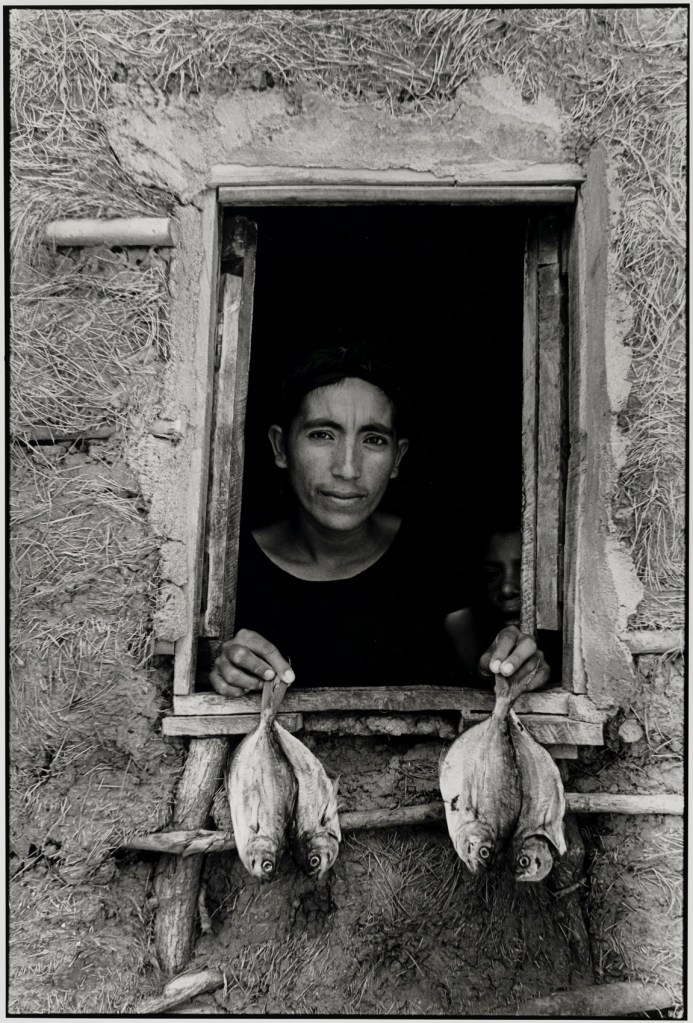

Claudia Andujar, Amazônia, 1978

Since the early 1970s, Claudia Andujar has been committed to the cause of the Yanomami Indians living in the heart of the Amazon rainforest and is the author of the most important photographic work dedicated to them to date. A founding member of the Brazilian NGO Comissão Pró Yanomami (CCPY), the photographer has played a fundamental role in the recognition of their territory by the Brazilian government. …

Claudia Andujar first met the Yanomami in 1971 while working on an article about the Amazon for Realidade magazine. Fascinated by the culture of this isolated community, she decided to embark on an in-depth photographic essay on their daily life after receiving a Guggenheim fellowship to support the project. From the very beginning, her approach differed greatly from the straightforward documentary style of her contemporaries. The photographs she made during this period show how she experimented with a variety of photographic techniques in an attempt to visually translate the shamanic culture of the Yanomami. Applying Vaseline to the lens of her camera, using flash devices, oil lamps and infrared film, she created visual distortions, streaks of light and saturated colors, thus imbuing her images with a feeling of the otherworldly.

Text from the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain website

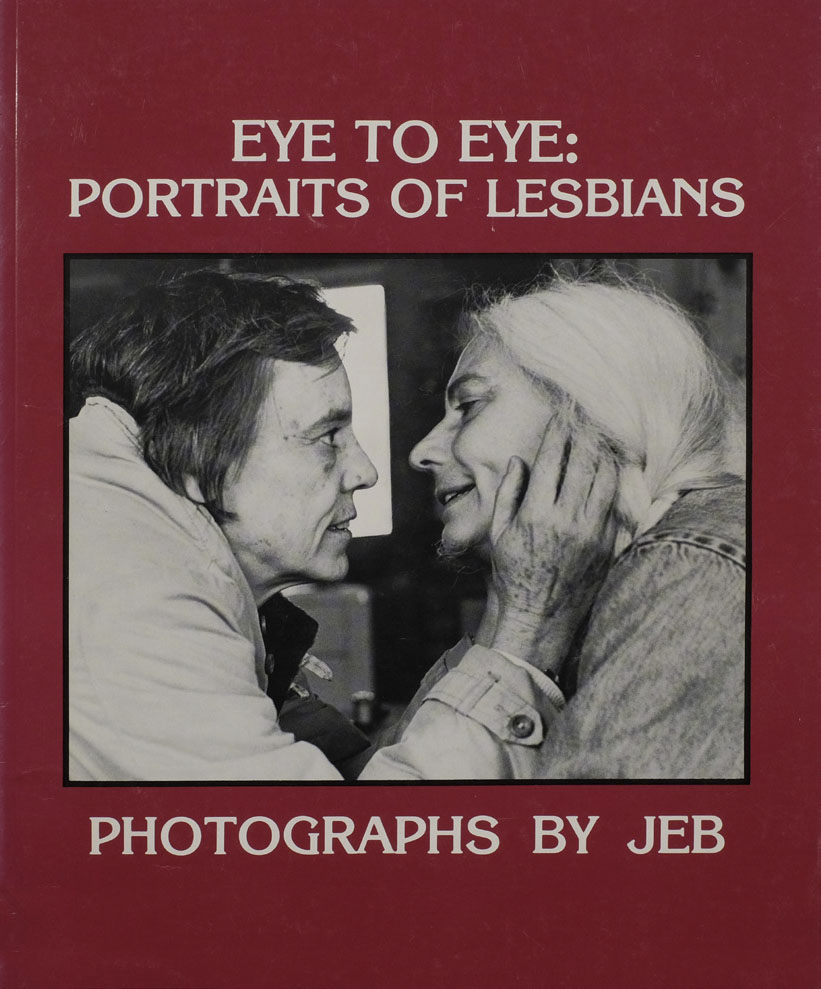

Cover image of Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians (1979). Photographs by JEB (Joan E. Biren)

In 1979, JEB (Joan E. Biren) self-published her first book, Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians. Revolutionary at that time, JEB made photographs of lesbians from different ages and backgrounds in their everyday lives-working, playing, raising families, and striving to remake their worlds. The photographs were accompanied by testimonials from the women pictured in the book, as well as writings from icons including Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich and a foreword from Joan Nestle. Eye to Eye signalled a radical new way of seeing – moving lesbian lives from the margins to the centre, and reversing a history of invisibility. More than just a book, it was an affirmation of the existence of lesbians that helped to propel a political movement. Reprinted for the first time in forty years and featuring new essays from photographer Lola Flash and former soccer player Lori Lindsey, Eye to Eye is a faithful reproduction of a work that continues to resonate in the queer community and beyond.

Text from the Amazon website

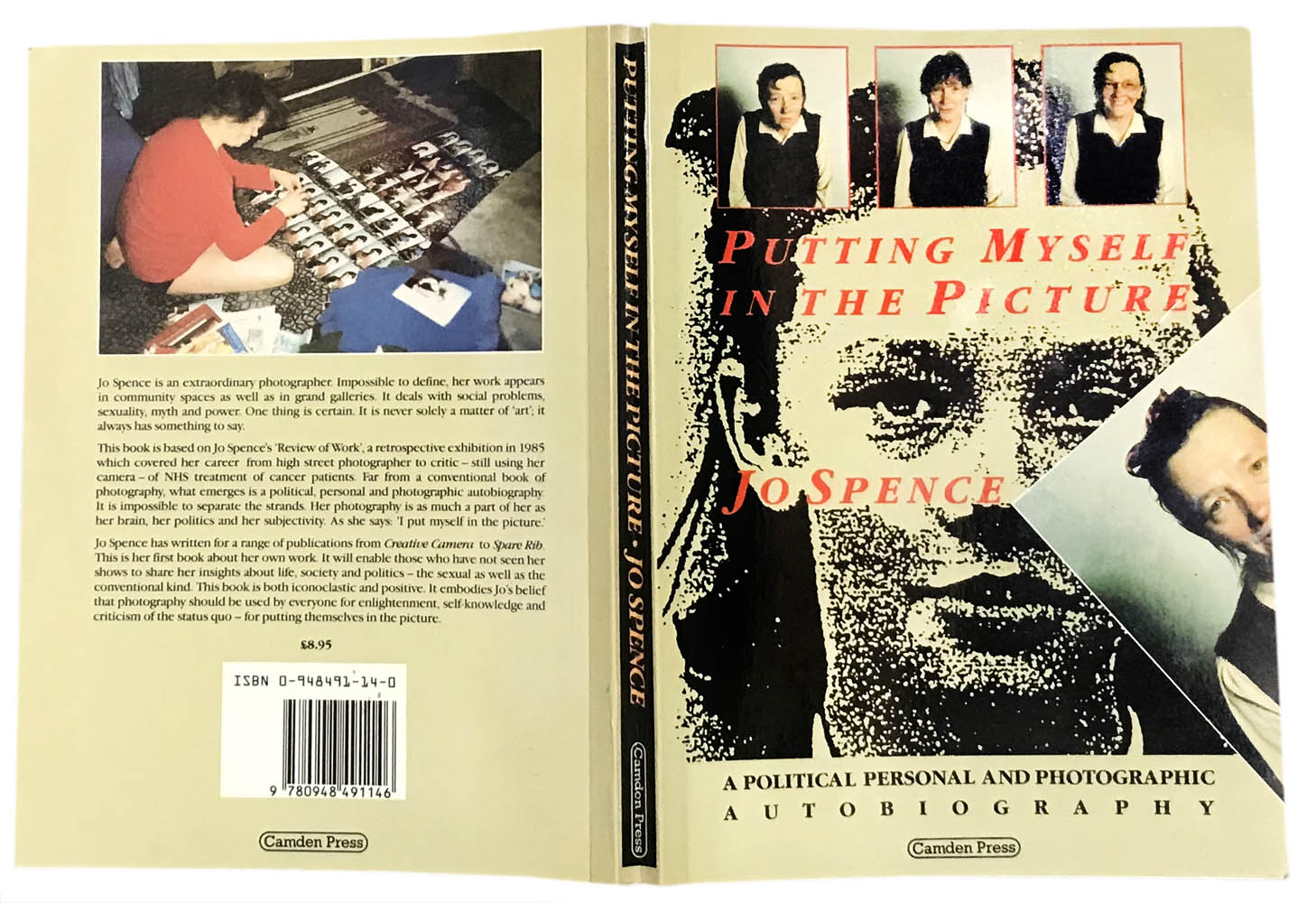

Jo Spence. Putting Myself In The Picture: A Political, Personal, and Photographic Autobiography. London: Camden Press Ltd, 1986

Photographer Jo Spence challenges the assumptions of conventional photography in this groundbreaking visual autobiography, which traces her journey from self-censorship to self-healing.

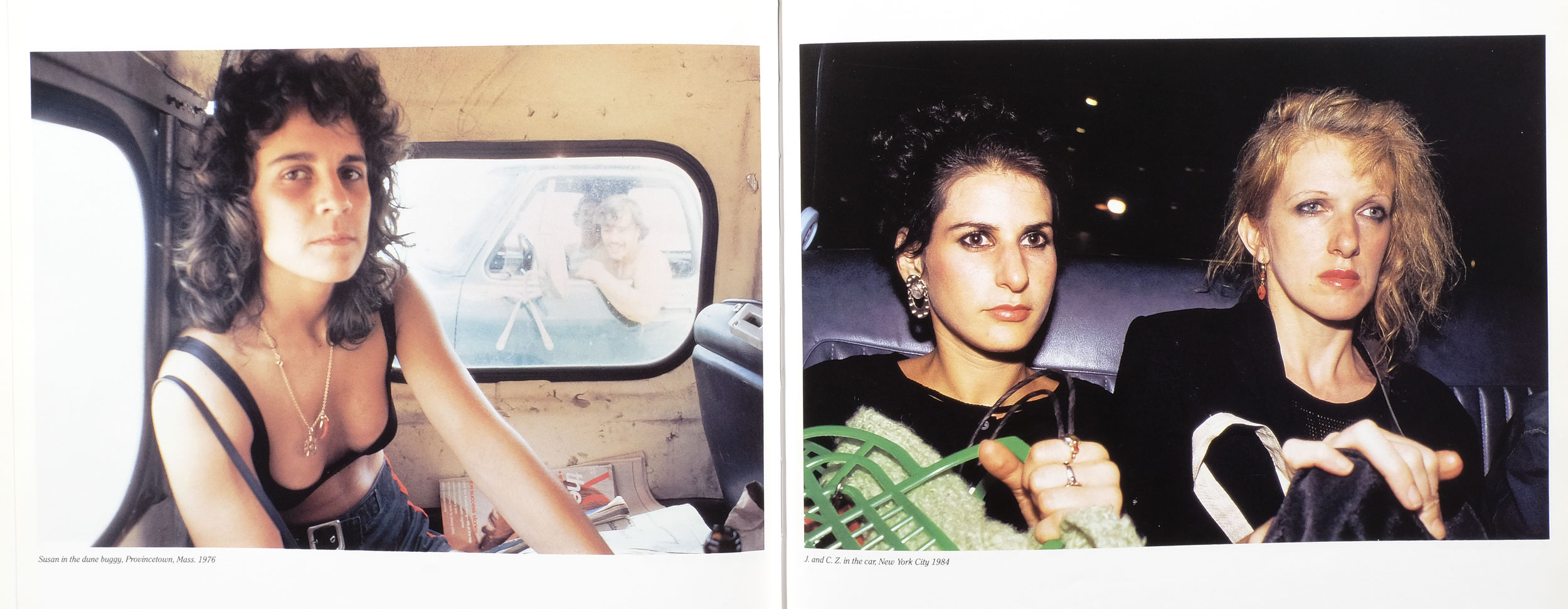

Nan Goldin, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 1986

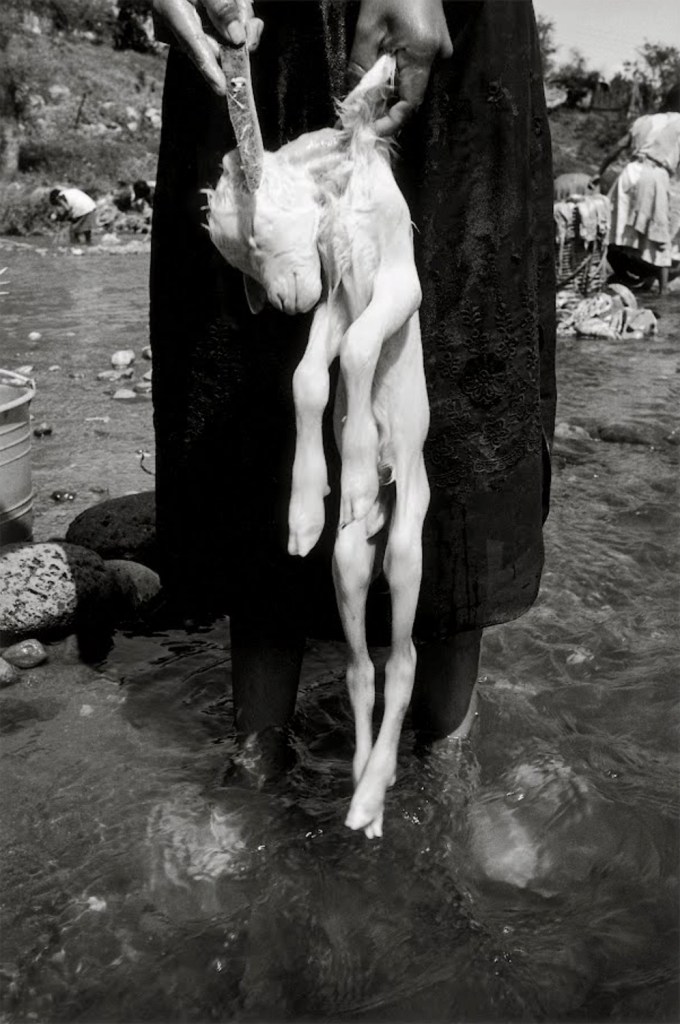

Cristina García Rodero. España Oculta. 1989

When Spanish photographer Cristina Garcia Rodero went to study art in Italy, in 1973, she fully understood the importance of home. Yet her time abroad formented a deeper interest in was happening in her own country and, as a result, at the age of 23, Garcia Rodero returned to Spain and started a project that she hoped would capture the essence of the myriad Spanish traditions, religious practices and rites that were already fading away. What started as a five-year project ended up lasting 15 years and came to be the book España Oculta (Hidden Spain) published in 1989. At 39 years old, Garcia Rodero had managed to compile a kind of anthropological encyclopedia of her country. The work also captured a key moment in Spain’s history – with Spanish dictator Franco dying in 1975, and the country commencing a period of transition – something that would come to have a huge effect on the way the nation’s cultural traditions and rites were experienced and performed from then on.

Text from the Google Books website

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. The MIT Press & The Museum of Contemporary Art, 1999

This is the most comprehensive publication ever produced on the work of American artist Barbara Kruger. Kruger, one of the most influential artists of the last three decades, uses pictures and words through a wide variety of media and sites to raise issues of power, sexuality, and representation. Her works include photographic prints on paper and vinyl, etched metal plates, sculpture, video, installations, billboards, posters, magazine and book covers, T-shirts, shopping bags, postcards, and newspaper op-ed pieces.

This book serves as the catalog for the first major one-person exhibition of Kruger’s work to be mounted in the United States. The book, designed by Lorraine Wild in collaboration with the artist, contains texts by Rosalyn Deutsche, Katherine Dieckmann, Ann Goldstein, Steven Heller, Gary Indiana, Carol Squiers, and Lynne Tillman on subjects associated with Kruger’s work, including photography, graphic design, public space, power, and representation, as well as an extensive exhibition history, bibliography, and checklist of the exhibition. The cover features a new piece by Kruger, entitled Thinking of You, created especially for the catalog.

Text from the Amazon website

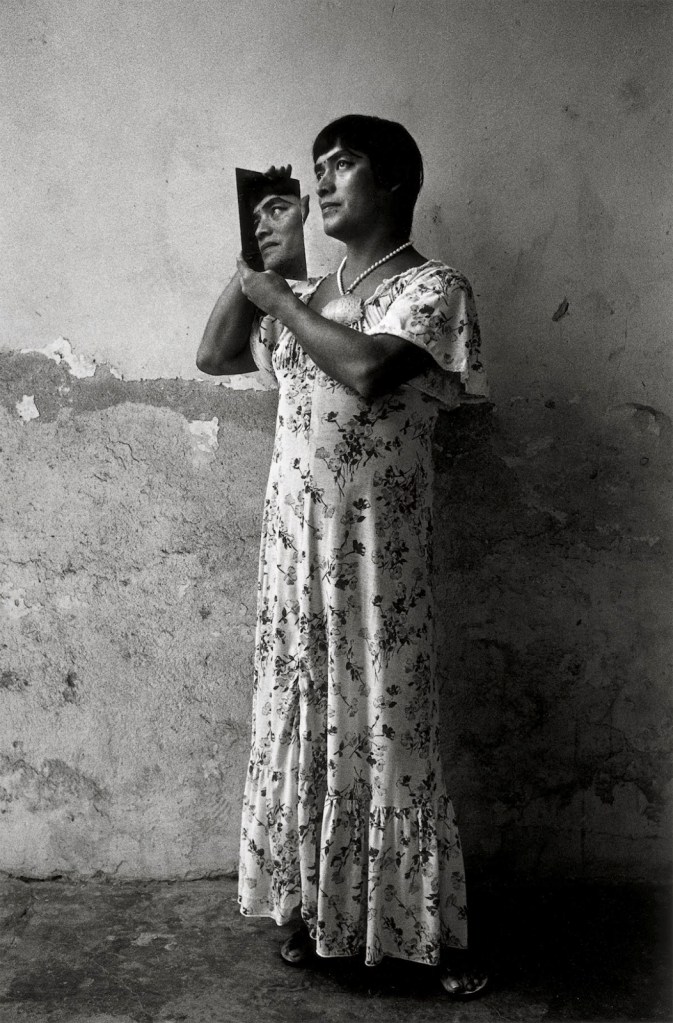

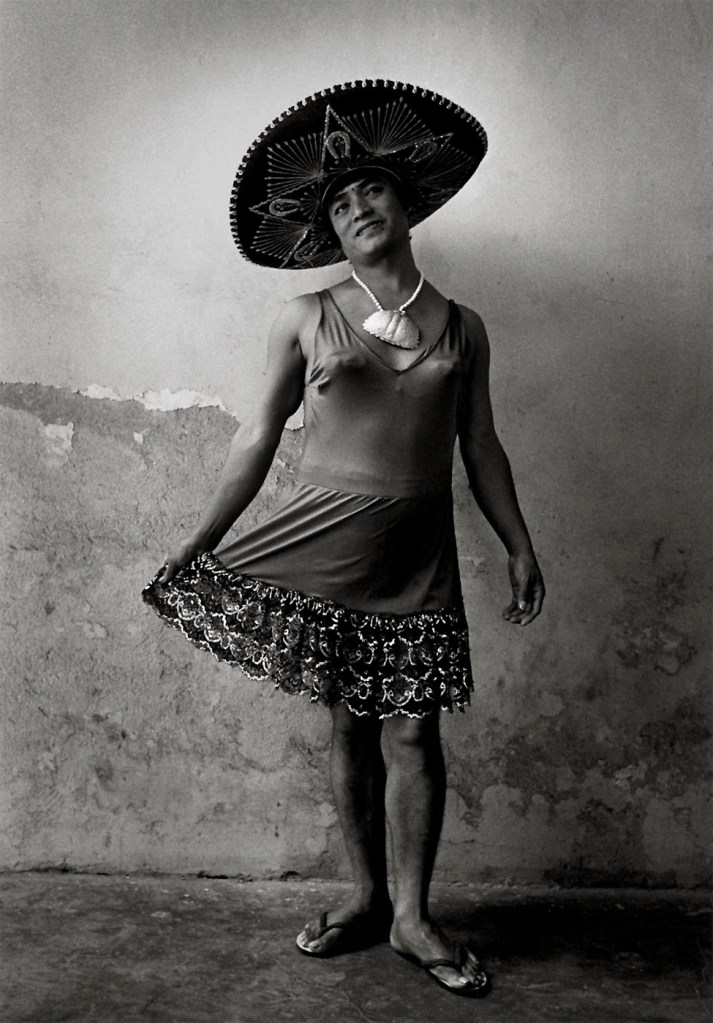

Graciela Iturbide. Juchitán de las Mujeres. Mexico: Ediciones Toledo, 1991

In 1979 Graciela Iturbide took a series of photographs of the Zapotec culture, published as Juchitán de la mujeres. This is certainly the best known of all her works. It is the result of ten years of work, numerous trips to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and a prolonged experience of living among its inhabitants. None of the subjects of these photographs was captured candidly; all were carefully posed.

Photobook history is a relatively recent area of study, with one of the first “book-on-books” anthologies published in 1999 with the release of Fotografía Pública / Photography in Print 1919-1939, a catalogue associated with an exhibition of the same title at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Over the past two decades, a virtual cottage industry of books-on-photobooks has emerged, documenting photographically illustrated books based on geography or around a theme. Photobooks by women are in short supply in most of these anthologies, which is why 10×10 Photobooks launched the How We See: Photobooks by Women touring reading room and associated publication in 2018. Focusing on contemporary photobooks by women from 2000 to 2018, the project was the first step in 10×10 Photobooks’ ongoing interest in reassessing photobook history as it relates to women. Although only twenty-five years old, photobook history has been written primarily by men and has focused on publications authored by men. Very few books by women photographers appear in past photobook anthologies, and those included are already quite well known.

As a nonprofit organisation with a mission to share photobooks globally and encourage their appreciation and understanding, the 10×10 Photobooks team frequently discusses how photobook history was – and continues to be – written from a skewed perspective and that a “new” history needs to emerge. Early in our discussions, we recognised photobook history as needing to be “rewritten,” but this implied we accepted the partial history already in existence, which we did not. Instead, we concluded that photobook history needs to be “unwritten,” as the existing history is riddled with omissions. What is left out is not by mistake – it indicates bias and incomplete research by the current gatekeepers. To present a more inclusive and diverse vision, we must collectively address these omissions.

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, a touring reading room accompanied by a publication and series of public programs, is a means to ignite interest in some of the underexposed and undocumented photobooks by women made between 1843 and 1999 and to begin a process of filling in the gaps. We say “some photobooks” because we are keenly aware that much work is still required, and we have only opened the door a crack. In several cases, particularly for books done before 1900 in regions other than North America and Europe or by women of colour, we heard about an artist who may have produced a photographically illustrated book or album, but we were unable to find any further documentation other than a brief mention before the trail went cold. Other impediments emerged among the cohort of women who collaborated with their husbands. Many of their collaborative books are credited only with their husbands’ names, and their contributions, if mentioned at all, are included as footnotes. In some cases, women authors marked their works with a gender-neutral signature that used only their studio name or first initial and last name. In addition, our initial research was impeded by the standard definition of a photobook: a bound volume with photographic illustrations published by the author, an independent publisher, or a trade publisher.

We found that we had to widen the frame to include individual albums, slim exhibition pamphlets, scrapbooks, maquettes, zines, and artists’ books in order to be more inclusive. This wider frame necessitated redefining a photobook author to incorporate those who may not call themselves a photographer or artist but who nonetheless assembled a “book” composed of photographs taken by themselves or others. Funding was another limitation. Many women photographers who actively exhibited their work either lacked the personal resources to produce a book or could not find anyone willing to underwrite such a venture.

This iteration of the What They Saw reading room includes 60 books of the more than 250 volumes highlighted in the associated publication. Most of these publications are kept in the collection of the Museo Reina Sofía’s Library and Documentation Centre. They are presented chronologically and show examples of books from around the globe. We begin with Anna Atkins, a British botanist, who was the first person ever to print and distribute a photobook. Her simple desire to share images of her algae specimens ushered in a new art form that presents photography in the book format. In the following years, women such as Isabel Agnes Cowper, the Official Museum Photographer at the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), used photography to document museum objects, subsequently reproduced in numerous books. Until recently, her name was forgotten, as none of the South Kensington Museum publications credit her as the photographer.

In the early twentieth-century, women authors of photobooks gained some visibility. Fine-art photographer Germaine Krull published numerous books that approached photography from a creative and inventive perspective. Margaret Bourke-White emerged as a well-regarded photojournalist who traveled worldwide photographing for Fortune and Life magazines and producing countless books. In the 1930s, in Russia, Varvara Stepanova collaborated with her husband, Aleksandr Rodchenko, to create books filled with experimental photomontages. As the century progressed, women in other parts of the world also found their voices in photobooks. African American anthropologist Eslanda Cardozo Goode Robeson traveled to Uganda and South Africa and published African Journey in 1945, one of the earliest books written on Africa by a female scholar of color. In Mexico in 1951, Lola Álvarez Bravo contributed photographs to Acapulco en el sueño, a bold publication created to attract tourism to Acapulco. A few years later, Fina Gómez Revenga, a Venezuelan photographer, worked in Paris with the famed French printing house Draeger Frères to illustrate the poems of Surrealist poet Lise Deharme.

With the arrival of the 1960s, women emerged from the sidelines and began to produce widely distributed, often socially focused, photobooks. A New York City street photographer, Helen Levitt, published A Way of Seeing in 1965, while Carla Cerati collaborated on Morire di classe in 1969, a visually compelling commentary on the appalling conditions in Italian psychiatric hospitals. With the women’s movement finding its full voice in the 1970s, women photographers took center stage in the last three decades of the twentieth-century, releasing a steady flow of photobooks. A year after her death in 1971, Aperture published Diane Arbus’s monograph, a photobook that continues to influence generations of photographers. Barbara Brändli, a Swiss immigrant to Venezuela, documents the energy and rapid transformations of Caracas, while activist-photographer JEB (Joan E. Biren) toured the United States, capturing lesbian pride events. In South Africa, Lesley Lawson, a member of the Afrapix photo agency, combined interviews and her photographs to reveal the working conditions of Black women in Johannesburg. Cameroonian Angèle Etoundi Essamba shares the beauty and spirit of Black women in Passion (1989), while American Donna Ferrato unflinchingly explores domestic violence in Living with the Enemy (1991), and Nan Goldin exposes violent love and loss in her personal narrative, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986). In books centered on cultural explorations, Wang Hsin photographs the fading traditions of Lanyu (Orchid Island) off the coast of Taiwan, Cristina García Rodero records religious festivals and rituals in her native Spain, and Ketaki Sheth documents twins and triplets in the Indian Gujarati community.

In reaching out to the far corners of the world, we uncovered numerous forgotten books, but many remain undiscovered. For example, we learned about a nineteenth-century woman in Iran who kept her husband’s diary and most probably added her photographs to the volume, but no visual documentation of this diary could be found. We also discovered several books that featured the participation of women in collaboration with male photographers where the women’s contributions were ambiguous. There were several “leads” of this nature, and we decided that leaving them out would be a missed opportunity. Therefore, in the associated anthology, we have included a “timeline” that presents several historically significant publishing, magazine, small press, photography, and feminist events that may or may not have produced a photobook, but have undoubtedly influenced its history. To support further exploration of these unresolved “leads,” 10×10 Photobooks has launched a research grant program to encourage scholarship on underexplored topics in photobook history.

From its inception, What They Saw has sought to include a diverse group of photographically illustrated publications by women. For photobook history to become more inclusive, it requires everyone (men, women, nonbinary, white, Black, Asian, African, Latinx, Indigenous, Western, Eastern, etc.) to contribute. We see this reading room of women’s role in the production, dissemination, and authoring of photobooks as a necessary step in the unwriting of the current photobook history and a rewriting of a photobook history that is more equitable and inclusive. We invite future researchers to take the next steps to explore further women and other marginalised people’s historical impact in the realm of photobooks and to expand upon the books we present in this reading room and its associated anthology.

Text from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

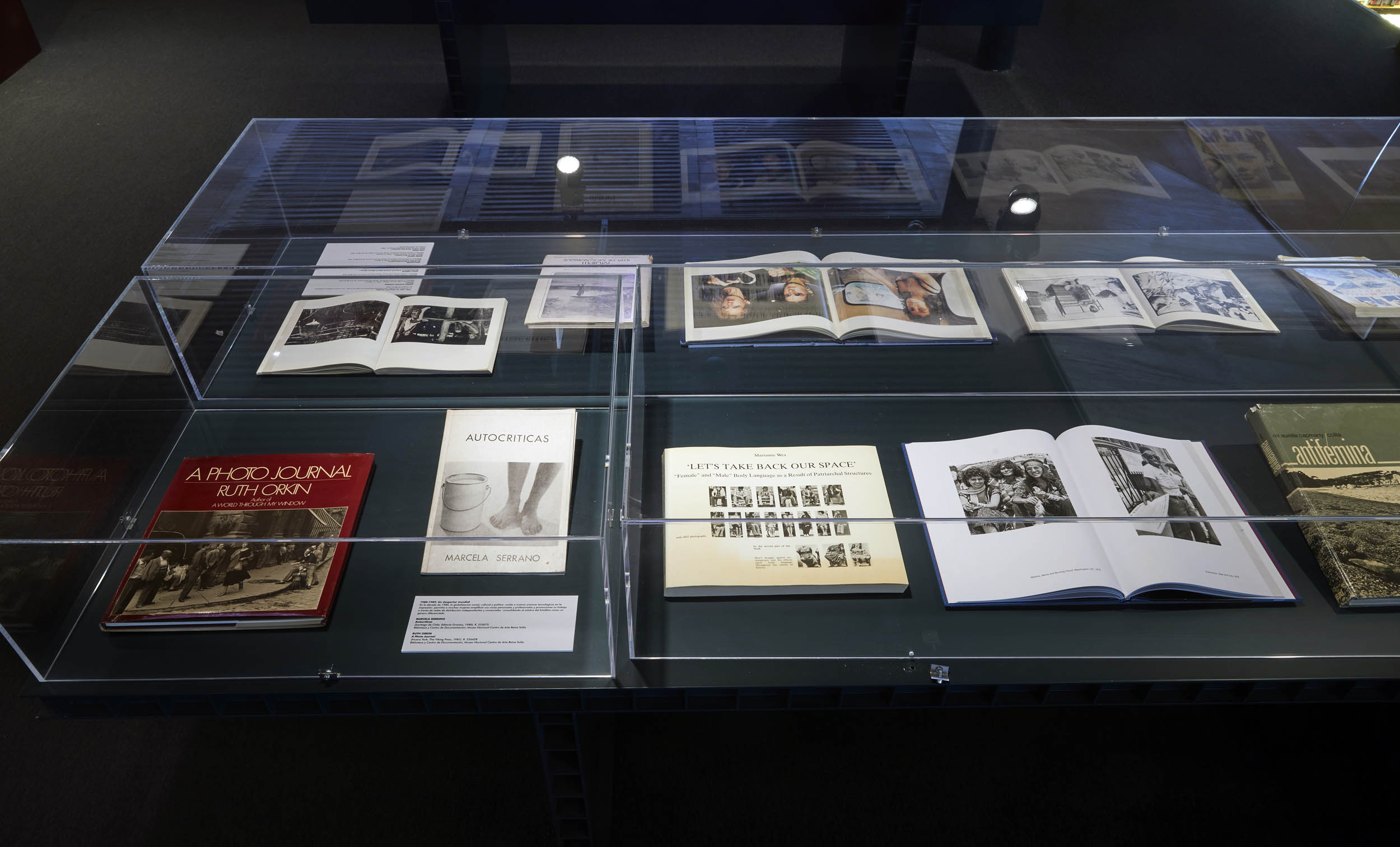

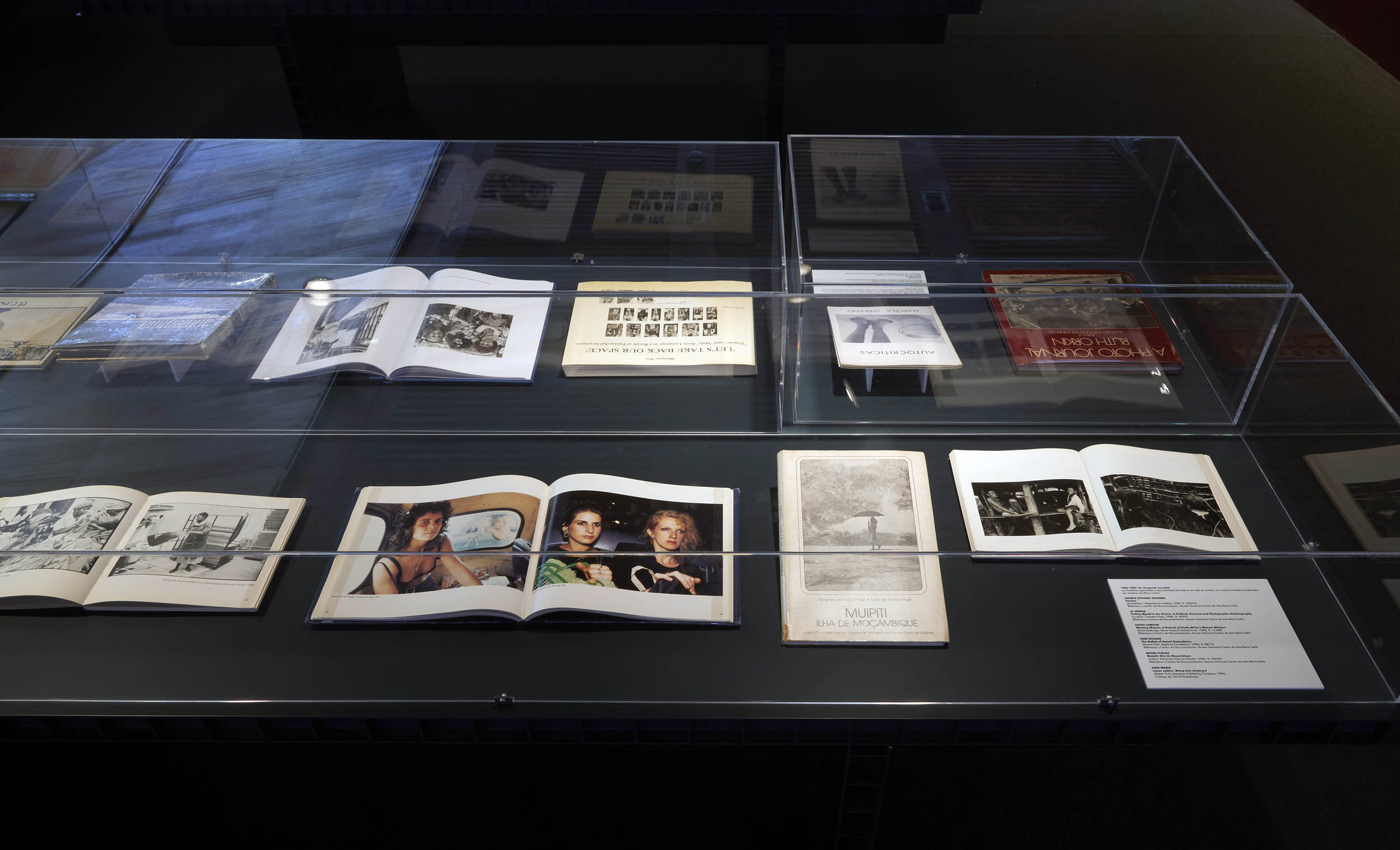

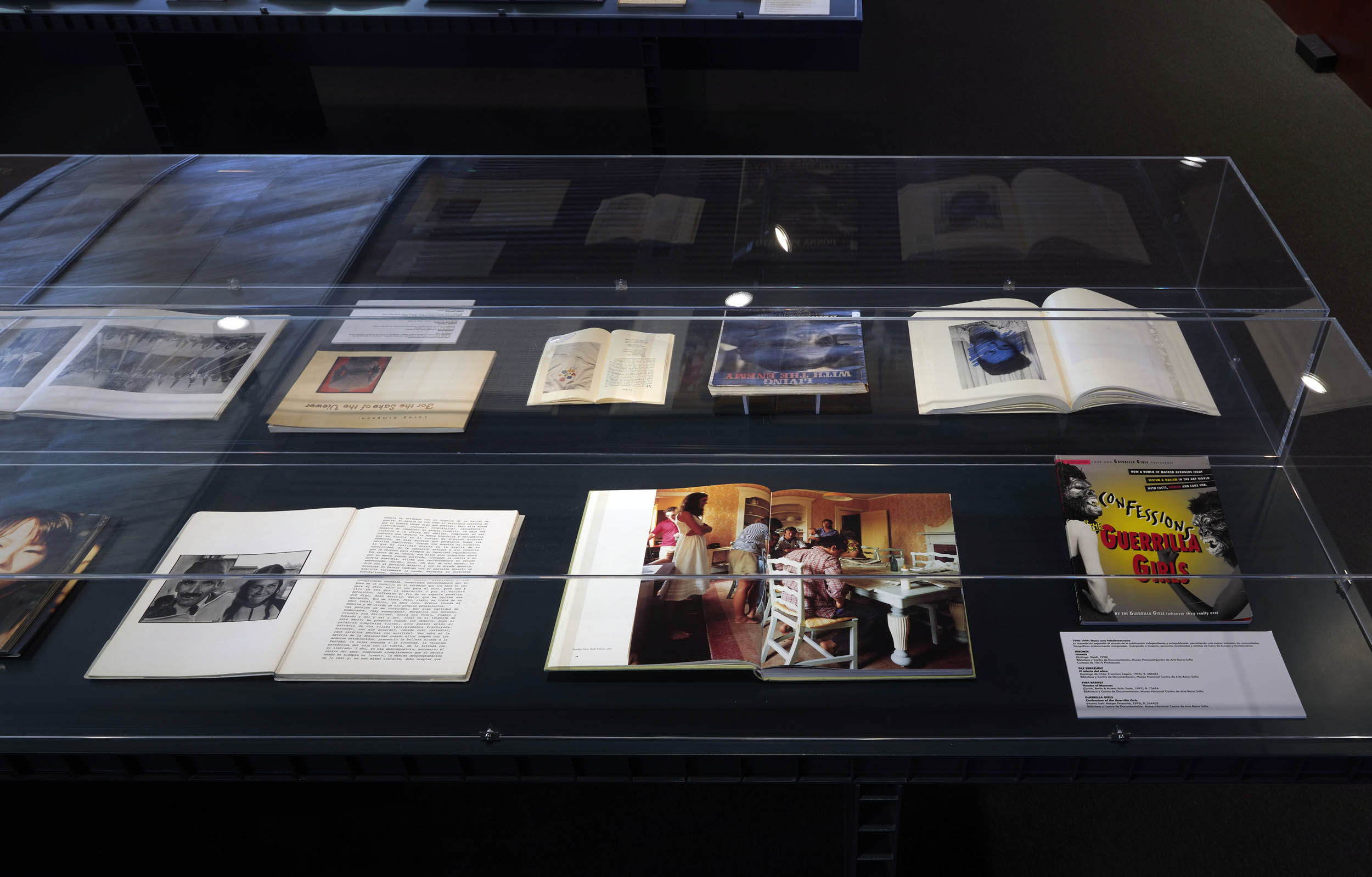

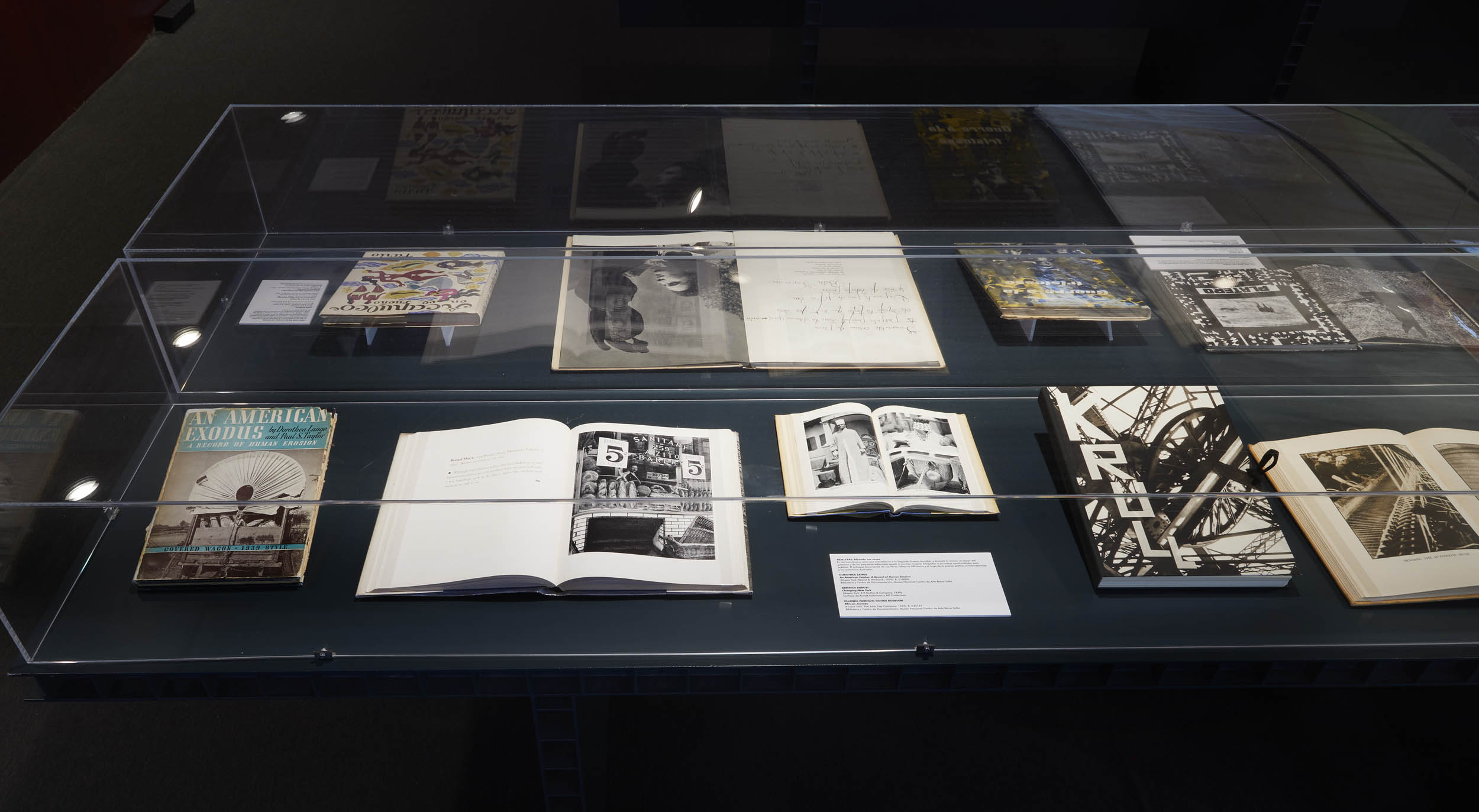

Installation views of the exhibition What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999 at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Sabatini Building

Santa Isabel, 52

Nouvel Building

Ronda de Atocha (with plaza del Emperador Carlos V)

28012 Madrid

Phone: (34) 91 774 10 00

Opening hours:

Monday 10.00am – 9.00pm

Tuesday Closed

Wednesday – Saturday 10.00am – 9.00pm

Sunday 12.30am – 2.30pm

![Leni Riefenstahl 'Schönheit im olympischen Kampf' [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937) Leni Riefenstahl 'Schönheit im olympischen Kampf' [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/leni-riefenstahl-schonheit-im-olympischen-kampf.jpg)

!['Leni Riefenstahl Schönheit im olympischen Kampf' [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937) pp. 220-221 'Leni Riefenstahl Schönheit im olympischen Kampf' [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937) pp. 220-221](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/leni-riefenstahl-schonheit-im-olympischen-kampf-a.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.