Exhibition dates: 9th February to 26th May 2024

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 1st volume, no. 2 from 30.08.1943

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

Unquenchable flame

Between August 1943 and April 1945, German Jew Curt Bloch created his own weekly, satirical poetry magazine, a unique work of creative resistance titled Het Onderwater Cabaret (The Underwater Cabaret) while holed up in an attic with two other adults on the Dutch German border.

Bloch conceived, wrote, designed, and produced 96 individual copies of “OWC” (Het Onderwater Cabaret‘s abbreviation after issue 33) with a total of 492 poems spanning over 1,700 pages. “The title alluded to a modern form of cabaret that had enthralled a large audience during the Weimar Republic (1918-1933). Cabaret performances typically consisted of a series of creatively crafted texts, songs, and scenes in which artists criticised societal injustices, mocked celebrities, and confronted the people with their perceived ignorance.”1

“… the Underwater Cabaret, which took its title from a unique term in Dutch for the act of going into hiding: “onderduiken.” Its literal translation is “to dive under,” but a common translation is “to slip out of public view.” A person in hiding was an “onderduiker,” who had gone “under water,” or was submerged.”2

Although he had no formal design training (he trained as a lawyer), Bloch had an innate understanding of modern design at that time: Bauhaus, Russian Constructivism, advertising, typography, collage, contemporary magazines such as the socialist Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung and the satirical and politically provocative collages of the artist John Heartfield. This knowledge of contemporary art practice undoubtedly shows in the inventive photomontages of the OWC front covers.

“He cut out letters, images, and shapes from various print media and glued them onto the cover paper… [using the] artistic technique of collage, which was also used in contemporary mass media… small artworks with the simplest materials and means, using creativity, improvisational talent, and subtle humour.”3

Each edition of Bloch’s magazine consisted of just a single copy which was passed around to a small number of people external to the attic. The small “OWC” booklets could be discreetly delivered from house to house in a jacket or pants pocket. All copies were returned to him.

“Bloch mocked and ridiculed all of the major fascist leaders, from Hitler, Goebbels and Göring, to Mussolini and Seyß-Inquart, Reich commissioner of the Netherlands, alongside a host of their subordinates and henchmen, while always remaining acutely conscious of the enormity of their atrocities.”4

And here’s the rub. Despite the threat to his life, the possibility of death if their hiding place or a copy of the magazine where discovered, this man – through his spirit, creativity and humour – stared down with unquenchable spirit the unconscionable behaviour of the Nazis.

In the last edition there appears one poem, the only one he wrote in English, which reads:

At Berlin with our Russian friends,

The German Nightingale,

Herr Hitler, doesn’t sing today

He’s feeling, after some delay

A tie around his neck.

The ogre had met his maker.

While Bloch survived his mother and his sisters and most of the rest of his family in Germany died in the war. He survived and so did his magazines, now to be appreciated as a unique work of creative resistance published during the Second World War. Respect.

Human nature will always resist oppression, something that should be remembered in these troubled times.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Anonymous text from the Curt Bloch Het Onderwater Cabaret website Nd [Online] 23/04/2024

2/ Nina Siegal. “He Made a Magazine, 95 Issues, While Hiding From the Nazis in an Attic,” on The New York Times website Dec. 18, 2023 [Online] Cited 20/12/2023

3/ Anonymous text from the Curt Bloch Het Onderwater Cabaret website Nd [Online] 23/04/2024

4/ Text from the Jewish Museum Berlin website

Many thankx to the Jewish Museum Berlin for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. For more information about Curt Bloch and the Het Onderwater Cabaret please see the Curt Bloch Het Onderwater Cabaret website.

Read more about Curt Bloch and his little magazine below.

Vielleicht kommen euch die Gedichte,

Die ich in eurer Sprache schrieb

In spätren Zeiten zu Gesichte

Und täten sie’s, wär mir’s recht lieb.Perhaps at some point in the future,

the poems in your tongue I composed,

will be brought to your notice,

and if so, to delight will I then be disposed.

(Transl. by Aubrey Pomerance)

“Bloch’s experience was different because, in addition to sustenance and care, his helpers brought him pens, glue, newspapers and other printed materials that he used to produce a startling publication: his own weekly, satirical poetry magazine.”

The New York Times

Over a period of more than 19 months between August 1943 and April 1945, the hitherto unknown German Jewish author Curt Bloch produced a unique work of creative resistance while in hiding in the Netherlands: Het Onderwater Cabaret.

Week for week, Bloch put together a small format booklet comprising of handwritten poems in both Dutch and German which confronted Nazi propaganda and addressed a wide variety of themes: the course of the war, the lies and crimes of the National Socialists and their collaborators, his situation in hiding and the fate of his family, the approaching downfall and defeat of the Axis forces, and the fate of the German people. Through caustic satire and sardonic wit, Bloch mocked and ridiculed all of the major fascist leaders, from Hitler, Goebbels and Göring, to Mussolini and Seyß-Inquart, Reich commissioner of the Netherlands, alongside a host of their subordinates and henchmen, while always remaining acutely conscious of the enormity of their atrocities.

Some eight decades since the creation of the work and nearly fifty years after his death, Curt Bloch’s hope is now finally being fulfilled: The exhibition presents all 95 original issues of the Het Onderwater Cabaret, accompanied by insight into the production of their covers, which Bloch adorned with photomontages put together using materials from newspapers and magazines at his disposal. Audio readings of selected poems and a video performance staged by the actors Marina Frenk, Richard Gonlag and Mathias Schäfer bring Bloch’s verses to life.

Alongside the display of additional works written by Bloch while “under water”, his helpers and those who were with him in hiding are introduced, accompanied by eyewitness interviews. The entire Het Onderwater Cabaret is accessible in digital form, accompanied by transcriptions.

Bloch’s works, known to only a handful of people at the time of their composition, will now find the recognition and appreciation they so greatly deserve. In today’s world, in which war, disinformation, discrimination, exclusion and persecution are widespread, they remain highly pertinent.

Text from the Jewish Museum Berlin website

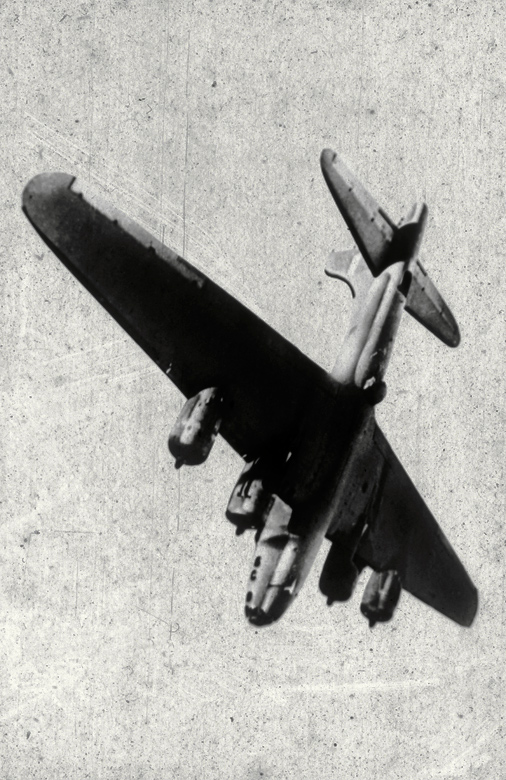

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine covers No.’s 1-95

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 1st volume, no. 6 from 25.09.1943

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

One of the earliest issues of “The Underwater Cabaret,” a weekly magazine made by a Jewish man hiding from the Nazis in Holland during World War II.

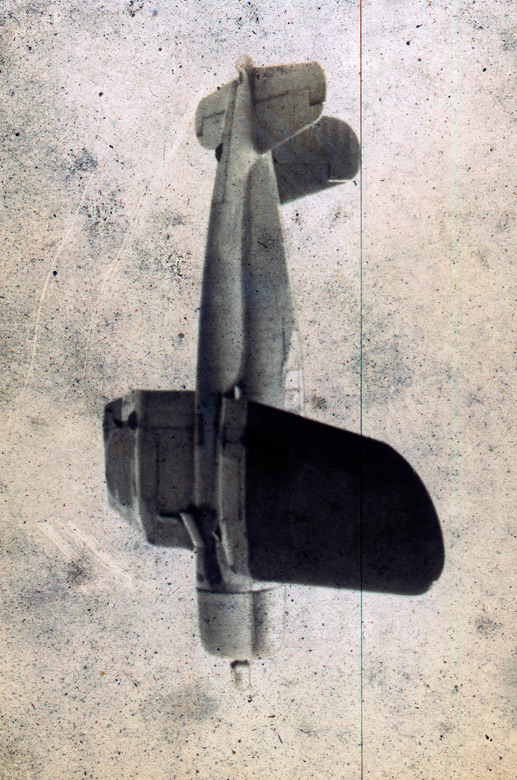

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 1st volume, no. 9 from 16.10.1943

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

Bloch’s magazine was satirical. Here he depicts British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, whose policy of appeasing Hitler drew criticism.

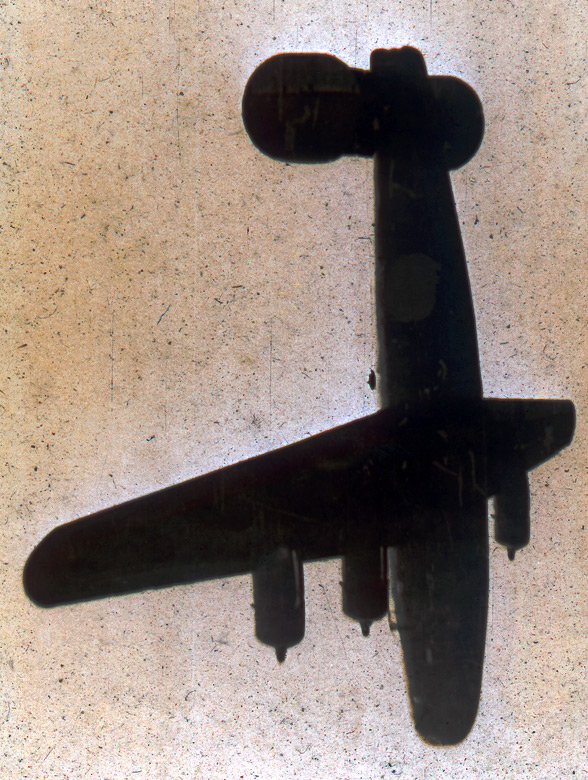

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 1st volume, no. 18 from 18.12.1943

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

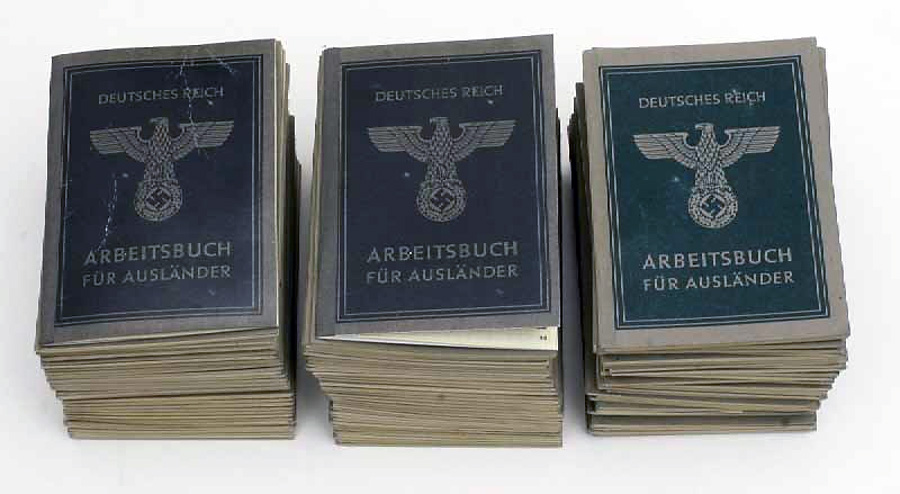

During the German occupation of the Netherlands, Curt Bloch lived in hiding, to avoid deportation to a labor or extermination camp. Under extremely challenging circumstances, Bloch developed a very personal form of resistance against the Nazi regime: “During the time I had to hide, I published a booklet of satirical poems in German and Dutch every week and circulated it among a small group.”

In reference to his fugitive situation, Bloch named his publication “Het Onderwater-Cabaret” (The Underwater Cabaret). The title alluded to a modern form of cabaret that had enthralled a large audience during the Weimar Republic (1918-1933). Cabaret performances typically consisted of a series of creatively crafted texts, songs, and scenes in which artists criticised societal injustices, mocked celebrities, and confronted the people with their perceived ignorance. Under Nazi rule, political cabarets were censored, closed, or forced to conform. The Dutch radio program “Cabaret op zondagmiddag” (Sunday Afternoon Cabaret) may have inspired Bloch to counter this fascist and anti-Semitic propaganda with his own subversive cabaret.

From 22 August, 1943, to 3 April, 1945, Curt Bloch conceived, wrote, designed, and produced 96 individual copies of “OWC” with a total of 492 poems spanning over 1,700 pages.

In 1943, he published 19 issues of his magazine. The following year: 61, including a special edition in July 1944 with no specific date assigned. The year 1945 included 15 magazines.

The magazines were typically published on Saturdays, but there were particularly productive periods, especially in August and September 1944, when he produced two issues per week.

Curt Bloch’s handmade booklets were slightly smaller than a standard postcard, measuring approximately 10 cm × 13.5 cm, and usually contained 16 or 20 pages.

All editions are fully preserved in numbered order. Only one poem, Farewell to ‘De Gouden Bommen’, had parts of the pages torn out, presumably intentionally, to remove any hints of a hiding place.

Content

In the first year of the OWC, Curt Bloch published 111 poems; in the second year, 302 poems (plus nine in the special edition); and in the third year, 70 poems. Most verses were written in rhymed quatrains, some as couplets or tail-rhymes. …

The Underwater Cabaret primarily dealt with current events of the time. Many contributions satirised well-known representatives of the Nazi regime, and some even dedicated entire poems to them. Besides Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels, who appeared most frequently in the verses, other figures such as Heinrich Himmler (Reich Interior Minister), Joachim von Ribbentrop (Reich Foreign Minister), Gerd von Rundstedt (Commander-in-Chief West), as well as foreign dictators Benito Mussolini (Italy) and Francisco Franco (Spain) were also targets for ridicule. Prominent Dutch fascists like Arthur Seyß-Inquart (Reichskommissar of the Netherlands), Anton Mussert (founder and leader of the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging, NSB), and Maarten van Nierop (NSB member and editor of the Nazi-controlled Twentsch Nieuwsblad) were also targets of his ridicule and mockery.

Another major theme of the OWC was the everyday experience of the occupation, including hunger, strikes, and raids. Bloch’s lyrical self also provided deep insights into his emotional world: concern for his family, especially his beloved sister Helene; despair and impatience in hiding; frustration over his isolated situation; gratitude for any form of support; joy at the victories of the Allies; and, repeatedly, hope for a swift return to freedom. Bloch’s rhymes display a wide range of emotions and changing moods depending on the course of the war.

Design

While the first covers of the OWC magazine were in black and white, Curt Bloch designed the covers of his magazine in colour from the 17th issue in 1943. He cut out letters, images, and shapes from various print media and glued them onto the cover paper.

In July 1944, Bloch decided to abbreviate the name of his magazine on the cover. Until issue 32 of the second year, he used the title “Het Onderwater-Cabaret.” From issue 33 onward, he used the abbreviation “OWC.” He retained this acronym on the cover until the final magazine.

Just as with the name of his magazine, Bloch’s cover design also refers to the characteristic popular culture of the Weimar Republic. His designs reference the artistic technique of collage, which was also used in contemporary mass media. Satirical and politically provocative collages by artist John Heartfield for the socialist Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung were particularly well-known.

Cabaret artists, collage artists, and Curt Bloch – who, as a trained lawyer, did not have formal design training – share the fact that they created unique small artworks with the simplest materials and means, using creativity, improvisational talent, and subtle humour.

Readership and Circulation

The weekly reading circle of the “Onderwater-Cabaret” began in Curt Bloch’s immediate environment, with the people who provided him with shelter, fellow fugitives like Karola Wolf and Bruno Löwenberg, and members of the resistance movement in Enschede. Once the window shutters were closed at night, Bloch could leave his hiding place. He often sat with his hosts and their visitors in the living room, where he could personally perform the cabaret pieces. However, his audience also included other fugitives and their supporters in different homes. Based on his research, Gerard Groeneveld, a Dutch historian and author (Het Onderwater Cabaret) estimates that the booklets reached up to thirty people. However, the exact number of readers and their names had to remain unknown due to the clandestine nature of the operation. …

The small “OWC” booklets could be discreetly delivered from house to house in a jacket or pants pocket. Getting caught with a magazine that satirised Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders would have been life-threatening for the couriers. In Germany, in 1943, four people who had disseminated one single satirical poem were sentenced to death for “undermining military morale.” Bloch wondered in A Goal: “What would happen to me, I have almost four hundred?”

Despite the extensive secret handovers required for circulation, Curt Bloch’s resistance operation remained undiscovered. All 96 editions were returned to him in good condition. After the war, he emigrated to the USA, where he had the booklets bound into four collected volumes.

Anonymous text from the Curt Bloch Het Onderwater Cabaret website Nd [Online] 23/04/2024

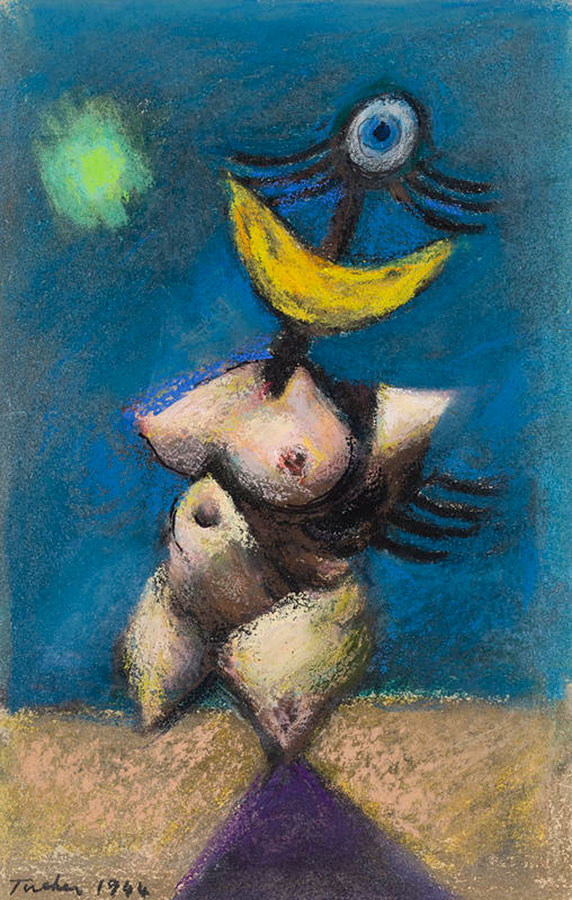

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 2nd volume, no. 3 from 15.01.1944

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

Doktor Göbbels Mummenschanz

Doctor Goebbels mask

The name “Mummenschanz” is a combination of “Mummen”, meaning to conceal or to mask (similar to the English “mummer”), and “Schanz”, a play on “chance”.

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret 2nd volume, no. 20 from 13.05.1944

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 2nd volume, no. 21 from 20.05.1944

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

Pioneers of Labor

They, who always reduced your wages

And increased your working hours

Plunged you comrades and metal proletarians

Into ever deeper poverty,

Those who only kept you in check

By delivering you to fascism,

Do you still remember the old

Representatives of capitalism?

Indeed, you will still recognise them,

The gentlemen and their crimes,

When you hear the name Röchling mentioned,

Then you think of the mines of the Stumm brothers

In the Saar region and the sufferings

The miner must endure there,

Mr. Röchling called you ungrateful

You were not hungry without complaints.

And Vögler, the head of the steel barons

In the Ruhr region, also let you starve

And ultimately left you to loiter

Without income in the streets.

And with their

Socio-political “merits”

Today the Führer makes these men “Pioneers

Of German labor,” well-regarded.

They are exploiters and oppressors

In Adolf’s beautiful miracle state,

They are even honoured as bringers of people’s happiness

And their praises are sung loudly.

These are the new “socialists”

Who vouch for your future,

The masterminds of the fascists,

Who strangle welfare, freedom, life.

They are the pioneers of misfortune,

Who cause unhappiness, hardship, and death,

How long will Germany endure their

Criminal tyranny?

Curt Bloch

Post-Editing: Sylvia Stawski, Ernst Sittig

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 2nd volume, no. 46 from 16.09.1944

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

This OWC edition was published on September 16 – four days earlier, the south of the Netherlands was liberated by the Allies as part of Operation “Market Garden.” Curt Bloch is pleased with the positive developments – and also with the fact that members of the Dutch Nazi movement are now filled with fear. He observes: The NSB members tremble. Their leader, Anton Mussert, calls for the evacuation of the families of his followers to the northeast of the Netherlands. In his verses, Bloch suspects that it will only be weeks before all of the Netherlands is liberated. However, he will have to wait more than half a year before he can leave his hiding place.

Text from the Curt Bloch Het Onderwater Cabaret website

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 2nd volume, no. 50 from 07.10.1944

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

“Die Man Rief, Die Geister…”

“The Spirits That I’ve Cited …”

Bloch depicted the brutish character of Nazism in some of his covers.

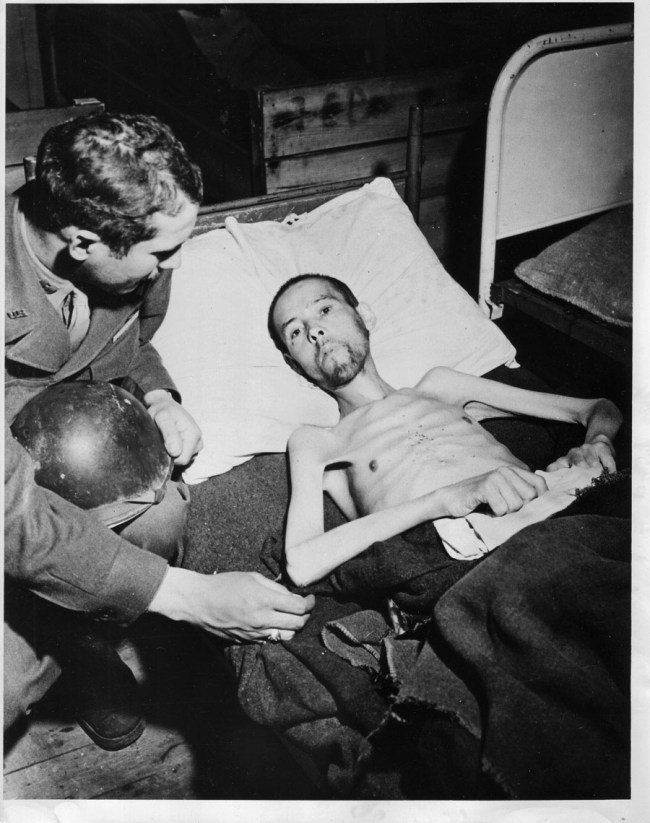

For more than two years, home for Curt Bloch was a tiny crawl space below the rafters of a modest brick home in Enschede, a Dutch city near the German border. The attic had a single small window. He shared it with two other adults.

During that time, Bloch, a German Jew, survived in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands by relying on a network of people who gave him food and kept his secrets.

In that respect, he was like at least 10,000 Jews who hid in Holland and managed to live by pretending not to exist. At least 104,000 others – many of whom also sought refuge, but were found – ended up being sent to their deaths.

But Bloch’s experience was different because, in addition to sustenance and care, his helpers brought him pens, glue, newspapers and other printed materials that he used to produce a startling publication: his own weekly, satirical poetry magazine.

From August 1943 until he was liberated in April 1945, Bloch produced 95 issues of Het Onderwater Cabaret, or The Underwater Cabaret.

Each issue included original art, poetry and songs that often took aim at the Nazis and their Dutch collaborators. Bloch, writing in both German and Dutch, mocked Nazi propaganda, responded to war news and offered personal perspectives on wartime deprivations.

In one poem, he sardonically suggested how recent events had reordered what it meant to be a beast in the animal kingdom:

Hyenas and jackals

Look on with jealousy

For they now seem as choirboys

Compared to humanity.

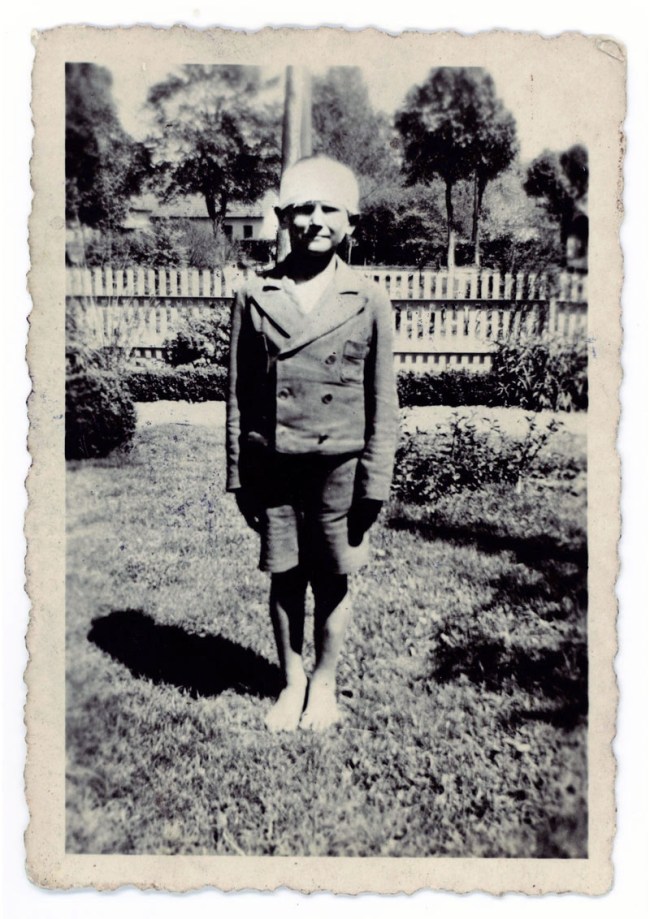

Bloch shared his handwritten magazine with the people he lived with, the family who sheltered him and, possibly, outside helpers and other Jews in hiding. After the war, which Bloch survived, he collected his magazines and brought them home and ultimately to New York, where he emigrated. There they sat on some bookshelves, the unknown creations of a man who was trained not as a poet, or an artist, but as a lawyer.

Bloch’s daughter, Simone Bloch, now 64, remembers seeing the magazines in the family home growing up. She didn’t fully grasp their significance, or particularly care to. A rebellious teenager by her own account, Simone said she never connected particularly well with her father, who died suddenly from a liver ailment when she was 15.

“A couple of times he read from them at dinner parties,” she said in an interview, “but I didn’t understand German then.”

Many years later, though, Simone’s daughter, Lucy, took an interest in the magazines, not just as family mementos but as markers of history. She got a research grant to travel to Germany, where she was able to study more about her grandfather’s history. Simone then spent years searching for a way to expand public awareness of the magazines, one of the few previously undiscovered literary efforts that document the Holocaust in Europe.

This led to the production of a book, The Underwater Cabaret: The Satirical Resistance of Curt Bloch, by Gerard Groeneveld, which was published in the Netherlands earlier this year. Soon there will also be a museum exhibition, “‘My Verses Are Like Dynamite.’ Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret,” which is scheduled to open in February at the Jüdisches Museum Berlin.

“Any time that an almost completely unknown work of this caliber comes to the fore, it’s very significant,” said Aubrey Pomerance, a curator of the Berlin museum exhibition. “The overwhelming majority of writings that were created in hiding were destroyed. If they weren’t, they’ve come to the public attention before now. So, it’s tremendously exciting.”

Research by Pomerance and Groeneveld for the exhibition and the book has helped to illuminate many aspects of Bloch’s life, which had not previously drawn much attention. Born in Dortmund, an industrial city in western Germany, Bloch was 22 and working at his first job as a legal secretary when Adolf Hitler became the chancellor of Germany in 1933. Antisemitic violence in Bloch’s hometown escalated even before official anti-Jewish measures were instituted.

After a colleague threatened his life that same year, Bloch fled to Amsterdam, where he took a job with a Persian rug importer and dealer. He hoped to find refuge there before escaping farther west, but his plans were dashed when the Germans invaded in 1940, the borders closed, and the nightmare expanded to Jews there as well.

Bloch’s firm transferred him to The Hague, but when non-Dutch Jews were forced out of the western Dutch provinces by the occupier’s decree, he was sent to work in a subsidiary in Enschede.

There, he got a job with the local Jewish Council, an organisation installed by the German overseers to implement Nazi antisemitic edicts. Jews who worked for the council were assured that they were safe from deportation.

Technically, Bloch was an adviser for “immigrant affairs,” although no opportunities for immigration existed – only transport to a concentration camp. The Enschede council understood the dangers and warned its members to go into hiding.

It was aided by an influential Dutch Reformed Church pastor, Leendert Overduin, who secretly ran a resistance organisation that helped some 1,000 Jews find places to hide. Known as Group Overduin, it consisted of about 50 people, including Overduin’s two sisters. Overduin was arrested three times and was imprisoned for this work; he has been recognised since as Righteous Among Nations by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance center in Jerusalem.

Group Overduin found Bloch a hiding place in the home of Bertus Menneken, an undertaker, and his wife, Aleida Menneken, a housekeeper. Their two-story brick house on Plataanstraat 15 was in a middle-class district of western Enschede.

There, Bloch shared the crawl space with a 44-year-old German-Jewish refugee, Bruno Löwenberg, and Löwenberg’s 22-year-old girlfriend, Karola Wolf, whom they called Ola. During their time in hiding, Bloch fell in love with Ola and wrote many verses just for her.

“He had a lot of courage, but he also had a reckless streak,” Groeneveld said.

Each edition of Bloch’s magazine consisted of just a single copy. But it may have been read by as many as 20 to 30 people, Groeneveld estimated.

There was a “huge organisation behind him, which included couriers, who brought food, but who could also bring the magazine out, to share with other people in the group who could be trusted,” Groeneveld said. “The magazines are very small, you can easily put one in your pocket or hide it in a book. He got them all back. They must have also returned them in some way.”

Bloch named his magazine in response to a German-language radio program that played on Dutch airwaves during the occupation, the Sunday Afternoon Cabaret. But this, Groeneveld explained, was the Underwater Cabaret, which took its title from a unique term in Dutch for the act of going into hiding: “onderduiken.” Its literal translation is “to dive under,” but a common translation is “to slip out of public view.” A person in hiding was an “onderduiker,” who had gone “under water,” or was submerged.

Groeneveld said Bloch’s covers, which were stylised photomontages, drew inspiration from anti-fascist satirical magazines of the prewar era, like the French “Marianne,” known for its anti-Nazi illustrations, and the German workers’ magazine Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung.

“His main target was Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister,” Pomerance said. “He often refers to articles that talk about a ‘final victory for the Nazis,’ and he mocks that notion, calling them murderers and liars. He was always sure that Germany would not win the war.”

In his poem, “The Way to Truth,” for example, he advised an imagined German reader how to approach Goebbels’ falsehoods:

If he writes straight, read it crooked.

If he writes crooked, read it straight.

Yes, just turn his writings around.

In all his useful words, harm is found.

Bloch’s writing wasn’t necessarily intended to live only on the page. During his time in hiding, he may have recited his poetry or performed the songs, Pomerance said.

“Quite a number of his poems were identified as being songs,” he said. “But unfortunately he didn’t provide any melodies that they should be sung to,” except for one, titled “Resistance Song.” The cover of the final issue, dated April 1945, after his liberation, is a photomontage of two people climbing out of a hatch. The title of that issue declares they are finally “above water.”

One poem in the edition, the only one he wrote in English, reads:

At Berlin with our Russian friends,

The German Nightingale,

Herr Hitler, doesn’t sing today

He’s feeling, after some delay

A tie around his neck.

Though Bloch survived, his mother and his sisters and most of the rest of his family in Germany died in the war. After the liberation of the Netherlands, he met Ruth Kan, who had survived a number of concentration camps, including Auschwitz. They married in 1946, had a son, Stephen, and moved to New York in 1948, where they later opened a business that sold European antiques and had Simone in 1959.

Beyond the new book and museum exhibition, Simone is developing a website that will feature her father’s art and poetry in three languages: German, Dutch and English.

That process has had a profound impact on her, she said.

“It provides not just insight, but access to my father in a way that I wish I’d had when I was young,” she said.

Nina Siegal. “He Made a Magazine, 95 Issues, While Hiding From the Nazis in an Attic,” on The New York Times website Dec. 18, 2023 [Online] Cited 20/12/2023

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret Magazine cover 2nd volume, no. 53 from 04.11.1944

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

“Ich schieb wache” I keep watch

Bloch was dedicated to publishing his magazine each week and numbered them.

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret Magazine cover 2nd volume, no. 57 from 05.12.1944

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 3rd volume, no. 5 from 03.02.1945

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 3rd volume, no. 12 from 24.03.1945

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

Bloch’s title: “The Fuhrer’s Mother”

Curt Bloch (German Jewish, 1908-1975)

Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover 3rd volume, no. 15 from 03.04.1945

Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch’s family

The final issue: liberated and “above water”

Immediately after the liberation of Enschede by British troops, Curt Bloch publishes his final magazine from underground. The headline on the front page reads “Bovenwater Finale van het O.W.C.” (Above Water Finale of the O.W.C.), accompanied by an image of a hidden person opening a cellar hatch. …

With the poem “Bovenwaterfinale van het O.W.C.” (Above Water Finale of the O.W.C.), Curt Bloch bids farewell as an underground publisher. He announces the end of The Underwater Cabaret and expresses gratitude for the attention. Now, one can return to the daylight, and his dream of freedom has come true. Bloch hopes that those who were taken from him will return (referring to his mother and two sisters, who were already murdered in concentration camps at this time, though Bloch will learn this not until later). Closing the chapter of his extensive publishing work in hiding, Bloch ends with the old-fashioned greeting “Tabé!” – a farewell phrase derived from Asian language usage.

Text from the Curt Bloch Het Onderwater Cabaret website

Above-Water Finale of the O.W.C.

We brought to you the final sounds

of the Underwater Cabaret,

And will thank you for your attention,

Since with this it will be ending.

Yes, it finally will close,

We now resurface

And no longer feel like outcasts

And not as pressurised as Hiob

Today, we crawl toward the daylight,

Our hiding time is in the past, thank God

And we are happy and are contented,

Because we finally are free –

This is the O.W.C. Finale

We long expected this,

That sometime we would be brought to daylight

After these years’ fearful night.

We were quiet partisans

And empathised with the fight for justice

And today the banners are waving.

And this fight has – almost – ended.

They did not cut us down to size

Although they wanted to,

You see: Injustice does not bring a blessing,

Our dream of freedom did come true.

Today we breathe in freedom’s air

Delightedly and greedily,

We, recently still sighing,

find the present to our liking.

And hope, that those who were sadly

torn away from us, will return,

Whether this will happen? Time will tell.

Sometimes we’re hopeful, sometimes sad.

After this time of cruel murders

Now comes a new melody,

Peaceful chords are coming,

There come prosperity and harmony

Now we will be building peace

And building a new era

Of charity and trust,

Of freedom and of justice.

Gone is the time of war and bombs,

Gone the wartime woe.

The OWC closes its columns

And says today forever:

Tabé!

Curt Bloch

Post-Editing: Hanny Veenendaal

Curt Bloch, undated; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2023/90/5, gift of Lide Schattenkerk

Jewish Museum Berlin

Libeskind Building, ground level, Eric F. Ross Gallery

Lindenstraße 9-14, 10969 Berlin

Opening hours: 10am – 6pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.