Exhibition dates: 29th March – 30th July 2023

Curator: Dr. Josie R. Johnson, Capital Group Foundation Curatorial Fellow for Photography at the Cantor Arts Center

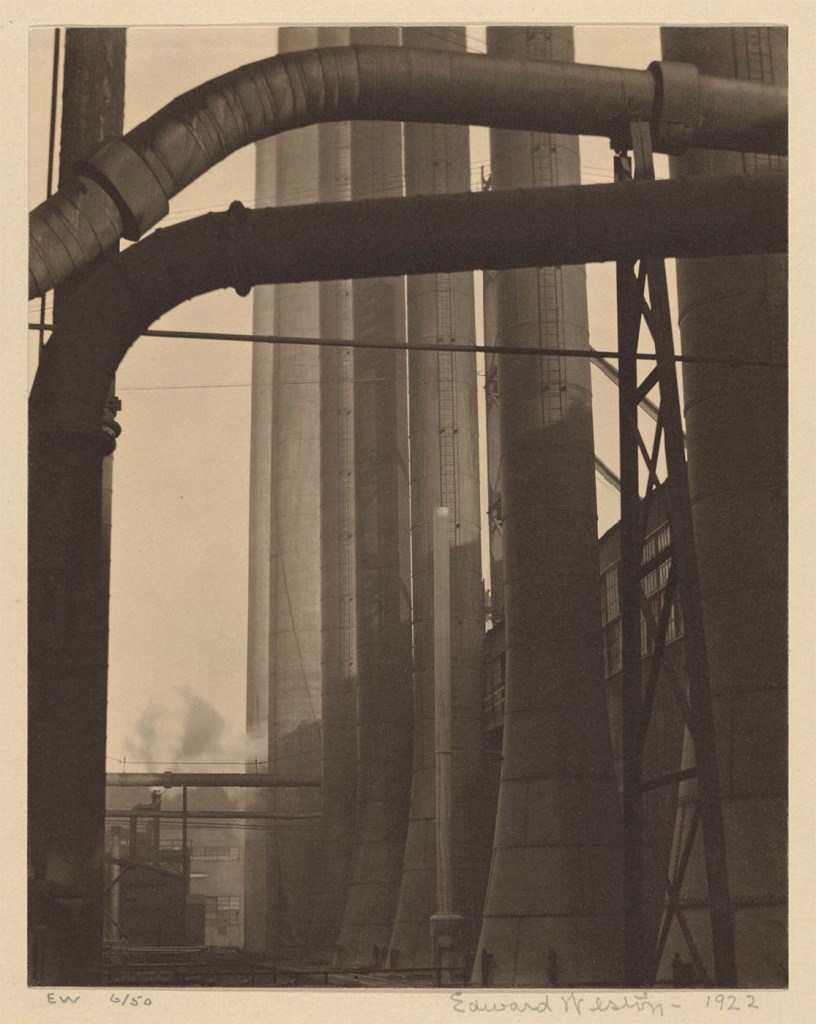

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Cypress Root and Rock, Seventeen Mile Drive

1929

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

On November 18, 1929, Edward Weston drove north from his home in Carmel to traverse the scenic coastal route of Seventeen Mile Drive. He made nine photographs of cypress roots and rocks that day, including this image. Less than three weeks earlier, the stock market had crashed, setting off a panic that plunged the United States into the Great Depression. Money troubles plagued Weston throughout his life, but on this November day, he was completely enthralled with the landscape. He wrote in his daybooks soon after that these photographs were “among the best seen and most brilliant technically I have yet done.”

Wall label from the exhibition

Transcending reality

While I admire the clever recontextualisation of the work of American photographers from the 1930s in this exhibition – into the sections Natural Wonders, Divine Figures, Everyday Splendors, Living Relics, The World of Tomorrow, Street Theater and Surreal Encounters – I am unsure that those photographers would ultimately see their work as a fusion of reality and dream, their documentary photographs “being both real and dream-like” that the concept of this exhibition proposes.

While all photographers use their imagination to visualise and take their photographs, to then extrapolate that these images are both reality-dream is, to my mind, a theoretical fancy that takes a kernel of the truth and views the images through a contemporary lens. Nothing wrong with that I hear you say and as the photographer Richard Misrach observes, “Photographs, when they’re made, can shift meaning with time, and often do.” And I agree that the meaning of photographs changes over time, is an ever fluid and shifting feast.

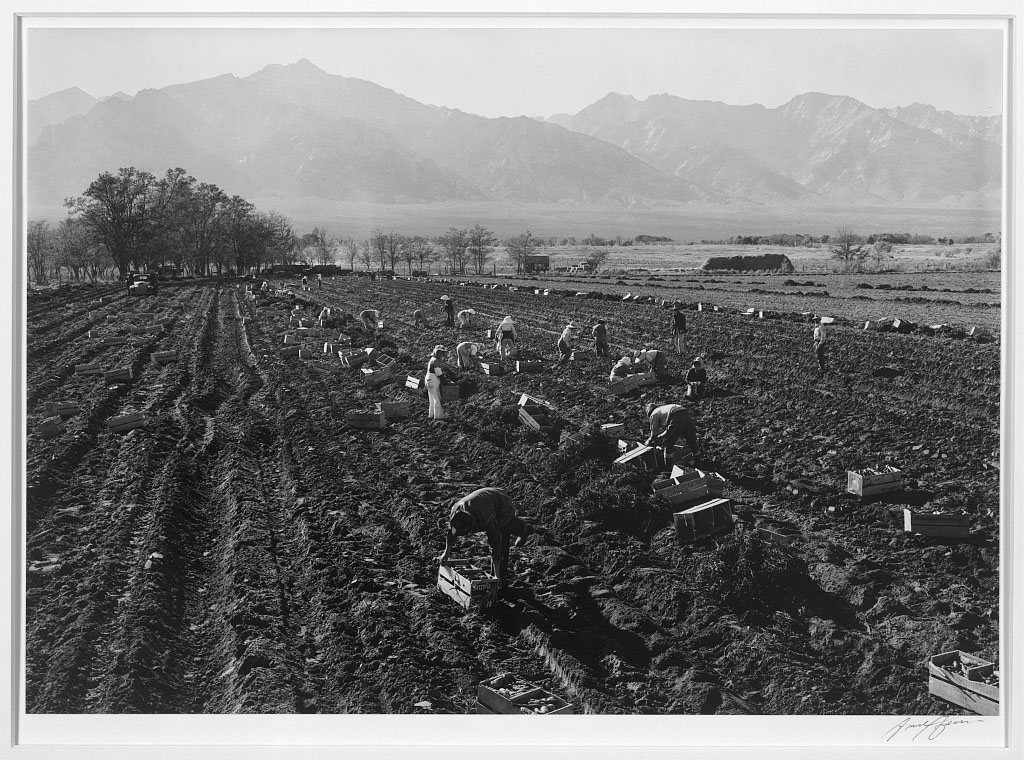

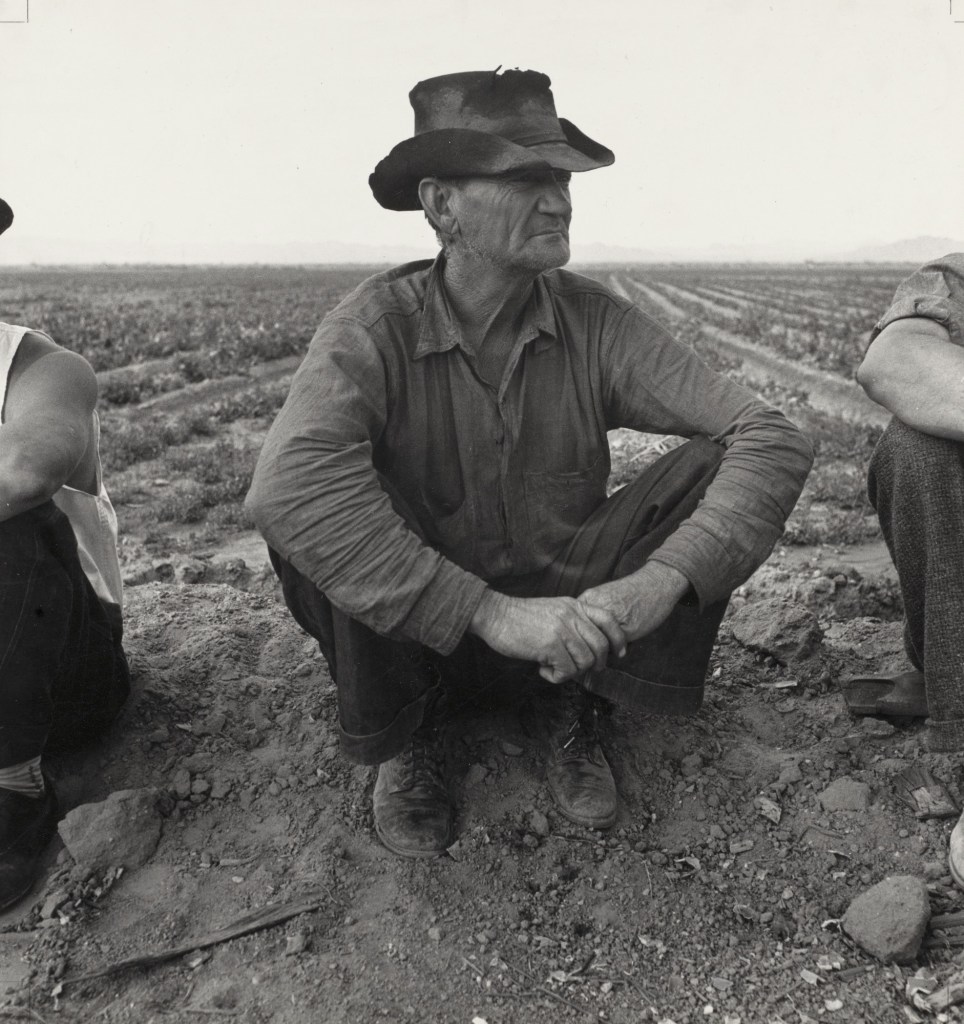

But can you imagine any of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers out in the field saying to themselves, “Oh! let’s take a dreamscape of these poor travelling people trying to survive the deprivations of hunger, poverty and joblessness”. It just wouldn’t happen. They didn’t think like that because it was a different era. They were concerned with representing with clarity and focus, with compassion and imagination not the melding of reality and dream, but the visceral feeling of the life being lived under the most trying of circumstances.

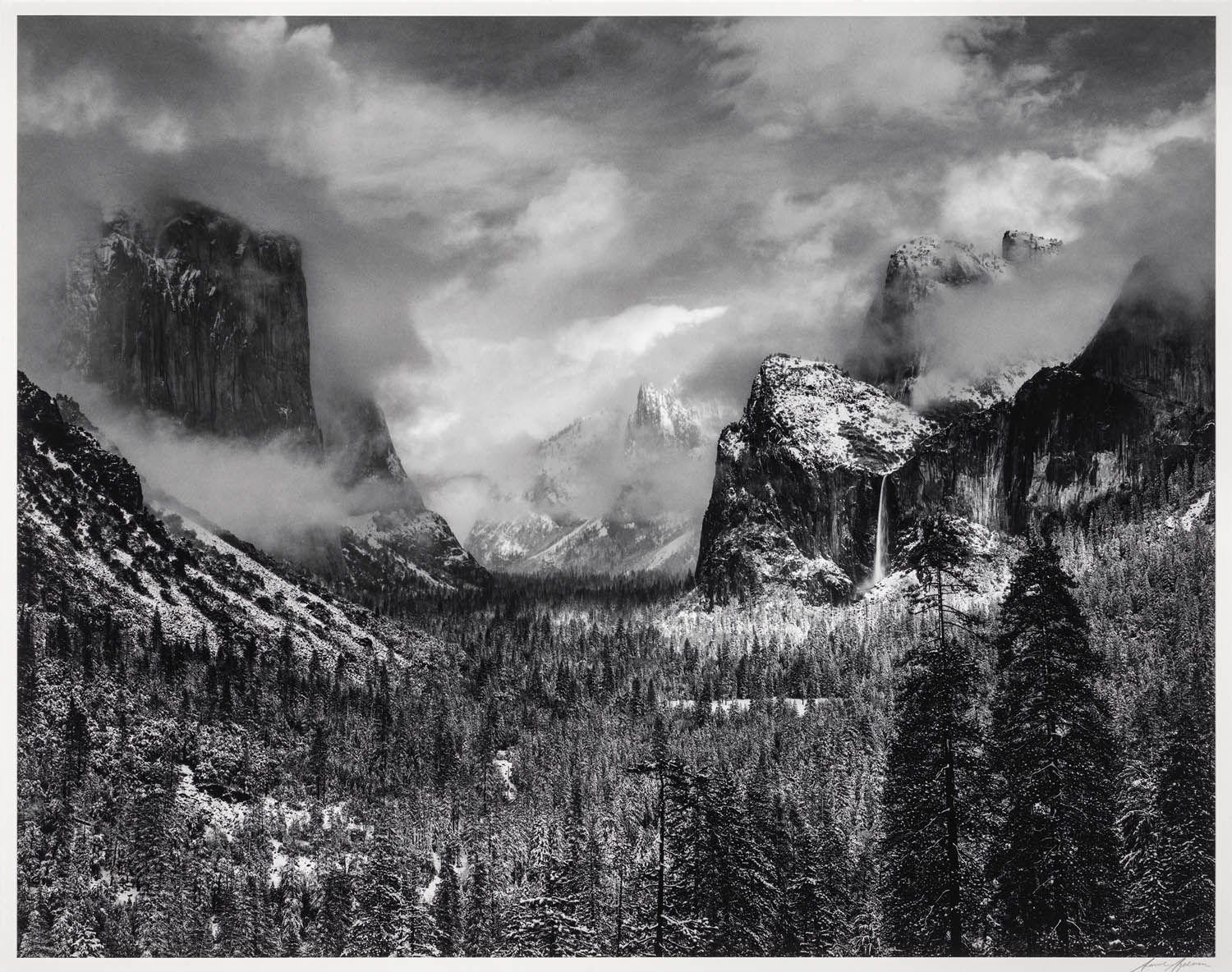

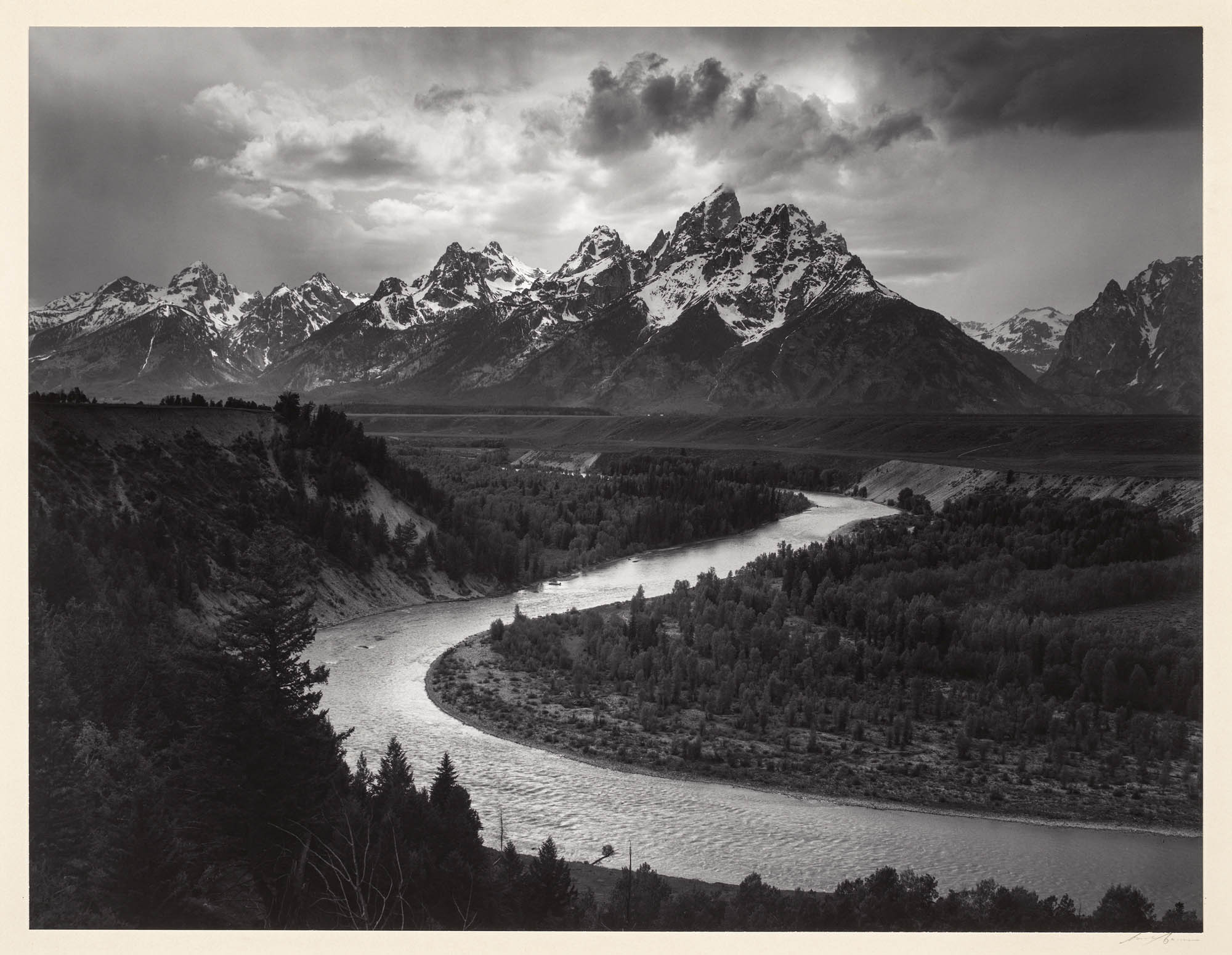

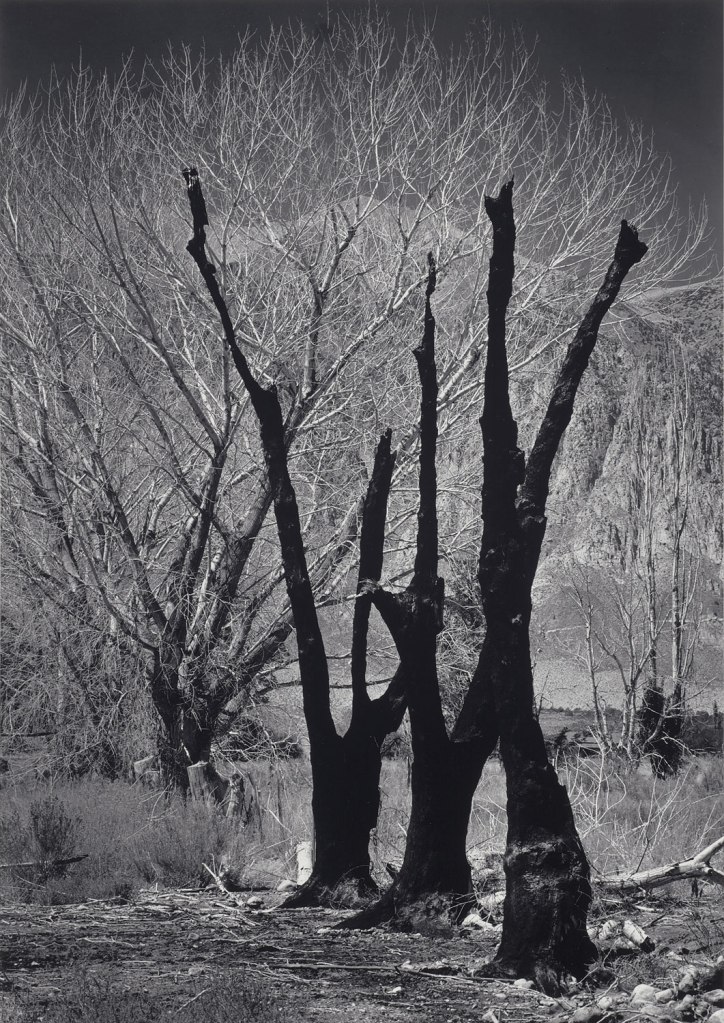

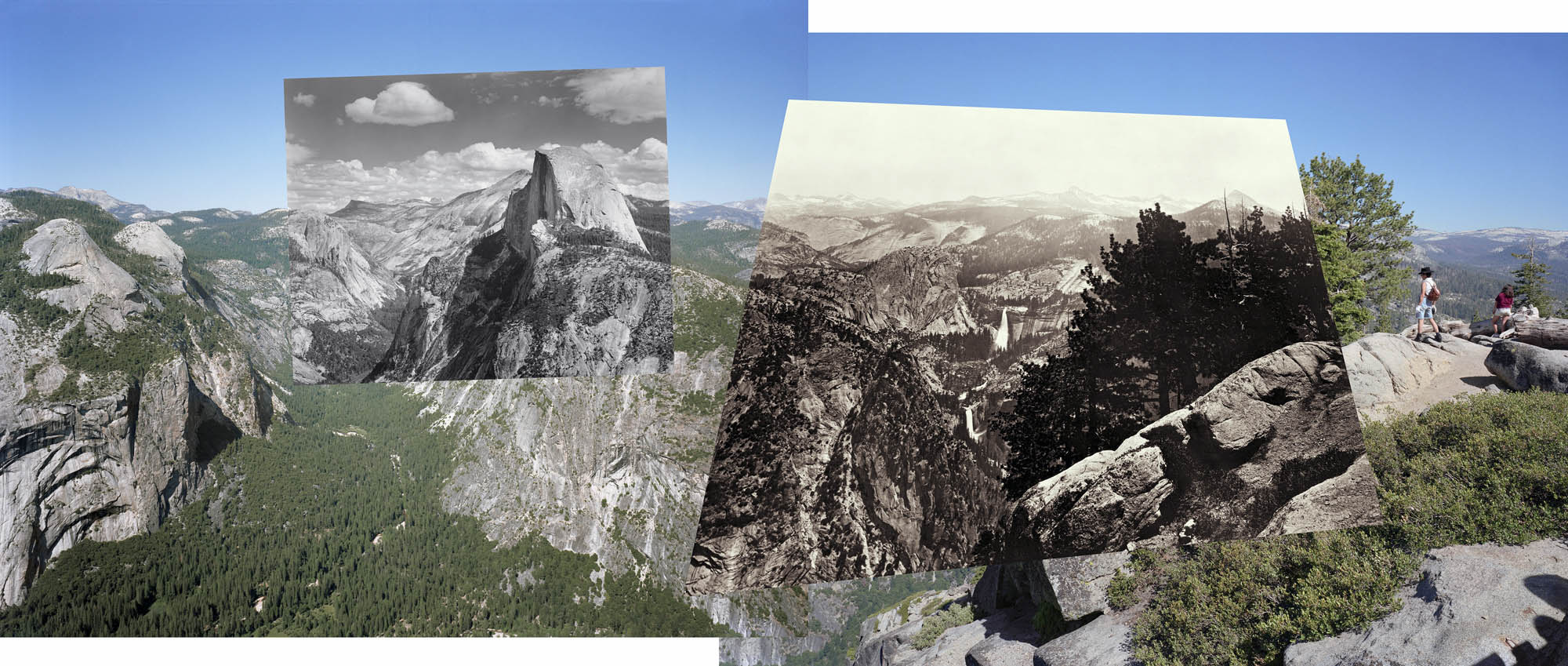

Following on from thoughts on the stunning landscape photographs of Ansel Adams in the last posting, one has to agree with Dr Isobel Crombie, Senior Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne when she says that,

“The term “landscape” can be ambiguous and is often used to describe a creative interpretation of the land by an artist and the terrain itself. But there is a clear distinction: the land is shaped by natural forces while the artist’s act of framing a piece of external reality involves exerting creative control. The terms of this ‘control’ have be theorised since the Renaissance and, while representations of nature have changed over the centuries, a landscape is essentially a mediated view of nature.”1

All photographs are a mediated view of reality, captured through the imagination of the artist and (usually) the gaze of the camera lens… but that does not necessarily mean that they are a melding of reality and dream: of course they can be – but in the context of 1930s American photography what is more likely is that the artists where attempting to create something that transcends the moment. As that fantastic American landscape photographer Robert Adams observes,

“At our best and most fortunate we make pictures because of what stands in front of the camera, to honor what is greater and more interesting than we are. We never accomplish this perfectly, though in return we are given something perfect – a sense of inclusion. Our subject thus redefines us, and is part of the biography by which we want to be known.”2

To my mind American photographers of the 1930s took photographs not only to document but also to honor what was greater and more interesting than they were. Not as a melding of reality-dream as this exhibition proposes, but as an exploration of what is possible through the interface of the image and imagination, the interface as Ansel Adams put it “between the reality of the world and the reality of yourself.”

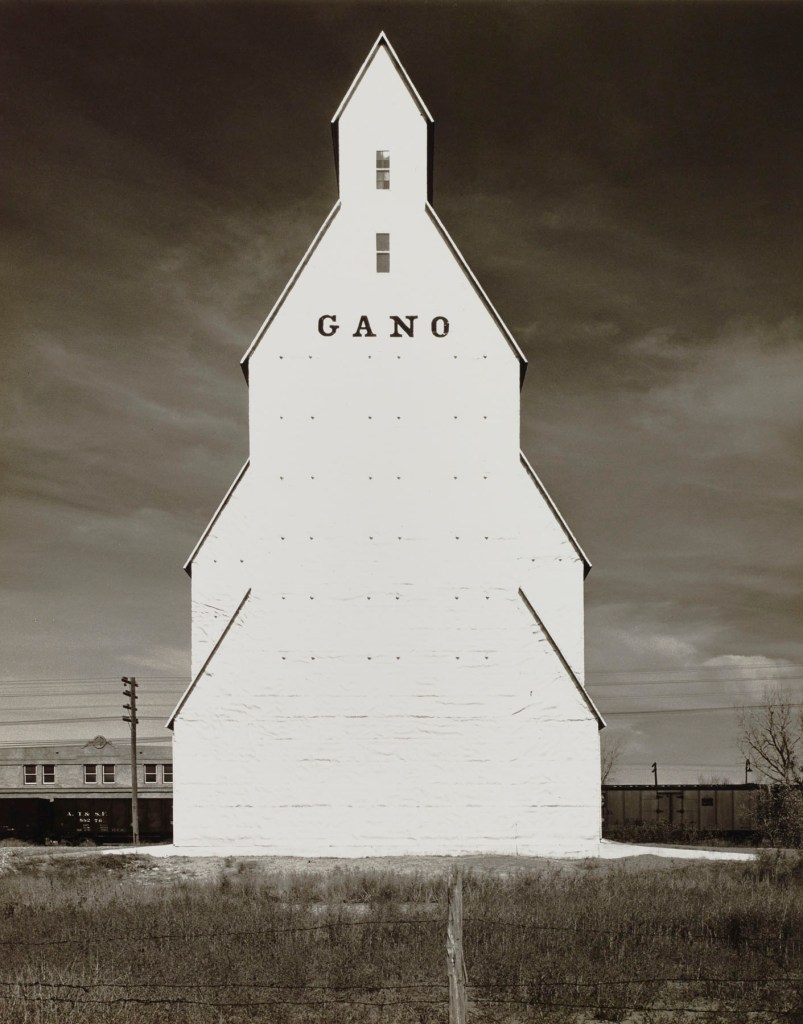

Finally, the unknown to me photographs of Wright Morris are superb because of their very capricious fidelity.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Isobel Crombie. Stormy Weather. Contemporary Landscape Photography (exhibition catalogue). Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2010, p. 15

2/ Robert Adams. Why People Photograph. New York: Aperture Foundation, 1994, p. 179

Many thankx to the Cantor Arts Center for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

In the fall of 1930, Stanford biology professor Laurence Bass-Becking used a curious phrase to describe the photography of his friend Edward Weston: “Reality makes him dream.” Few people today would associate dreaminess with the Great Depression, yet Bass-Becking penned this statement one year into the economic turmoil that would last until the nation’s entry into World War II. This exhibition of over 100 photographs, periodicals, and photobooks offers an alternative understanding of 1930s photography in the US by taking Bass-Becking’s phrase as its point of departure.

The work of five photographers featured in the Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at the Cantor Arts Center – Ansel Adams, John Gutmann, Helen Levitt, Wright Morris, and Edward Weston – comprises the core of the exhibition. Woven into this display is a diverse selection of photographs by their contemporaries that present new narratives about artists and images, from the iconic to the overlooked. Against the typical history of 1930s photography that views the work of this period as primarily documentary, this exhibition contends that a key goal for artists of this period was to use photography to ignite the imagination.

“If you have a conscious determination to see certain things in the world you are a potential propagandist; if you trust your intuition as the vital communicative spark between the reality of the world and the reality of yourself, what you tell in the super-reality of your art will have greater impact and verity. … without the elements of imaginative vision and taste the most perfect technical photograph is a vacuous shell.”

Ansel Adams. “Exhibition of Photographs” (1936), reproduced in Andrea Gray. Ansel Adams: An American Place, 1936. Tucson: Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, 1982, p. 38 quoted in Josie R. Johnson. “Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941,” in Josie R. Johnson. Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2023, p. 17.

The present exhibition [exhibition of contemporary photography in November 1930 at Harvard University] attempts to prove that the mechanism of the photograph is worthy and capable of producing creative work entirely outside the limits of reproduction or imitation. … Photography exists in the contemporary consciousness of time, surprising the passing moment out of its context in flux, and holding it up to be regarded in the magic of its arrest. It has the curious vividness and unreality of street accidents, things seen from a passing train, and personal situations overheard or seen by chance – as one looks from the window of one skyscraper into the lighted room of another forty stories high and only across the street.

Lincoln Kirstein, introductory note, Photography 1930. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, 1930, n.p. quoted in Josie R. Johnson. “Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941,” in Josie R. Johnson. Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2023, p. 26.

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Migrant Mother, California

1936

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

The Cantor Arts Center is pleased to present Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941, an exhibition featuring over 100 photographs, periodicals, and photobooks. This material collectively pushes against the typical history of 1930s photography that views the work of this period as primarily documentary, and instead illustrates that artists of this era frequently used photography to ignite the imagination. The exhibition and the expansive art historical narratives it illuminates result from Dr. Josie R. Johnson’s study over the past three years of the Cantor’s Capital Group Foundation (CGF) Photography Collection – a major gift of over 1,000 twentieth-century American photographs.

Currently serving as the museum’s CGF Curatorial Fellow for Photography, Johnson comments: “The Cantor’s holdings of American photography from the 1930s are especially rich, and the generous terms of the Capital Group Foundation Fellowship enabled me to delve deeply into this fascinating chapter of photo history. Sifting through these prints allowed me to set aside what I thought I knew about this material and take a fresh look, giving me a new appreciation for the novel approaches these artists developed in the midst of a profoundly difficult historical moment.”

The work of five photographers from the CGF Collection – Ansel Adams, John Gutmann, Helen Levitt, Wright Morris, and Edward Weston – comprises the core of the exhibition. Its conceit draws from a curious phrase by Stanford biology professor Laurence Bass-Becking about the photography of his friend Edward Weston: “Reality makes him dream.” Though few people today would associate dreaminess with the Great Depression, Bass-Becking penned this statement in the fall of 1930, one year into the economic turmoil that would last until the nation’s entry into World War II. Reality Makes Them Dream exemplifies the spirit of experimentation that Bass-Becking describes by highlighting an undercurrent of artistic practices in the United States that were sometimes more akin to those of Surrealism taking place concurrently in Europe.

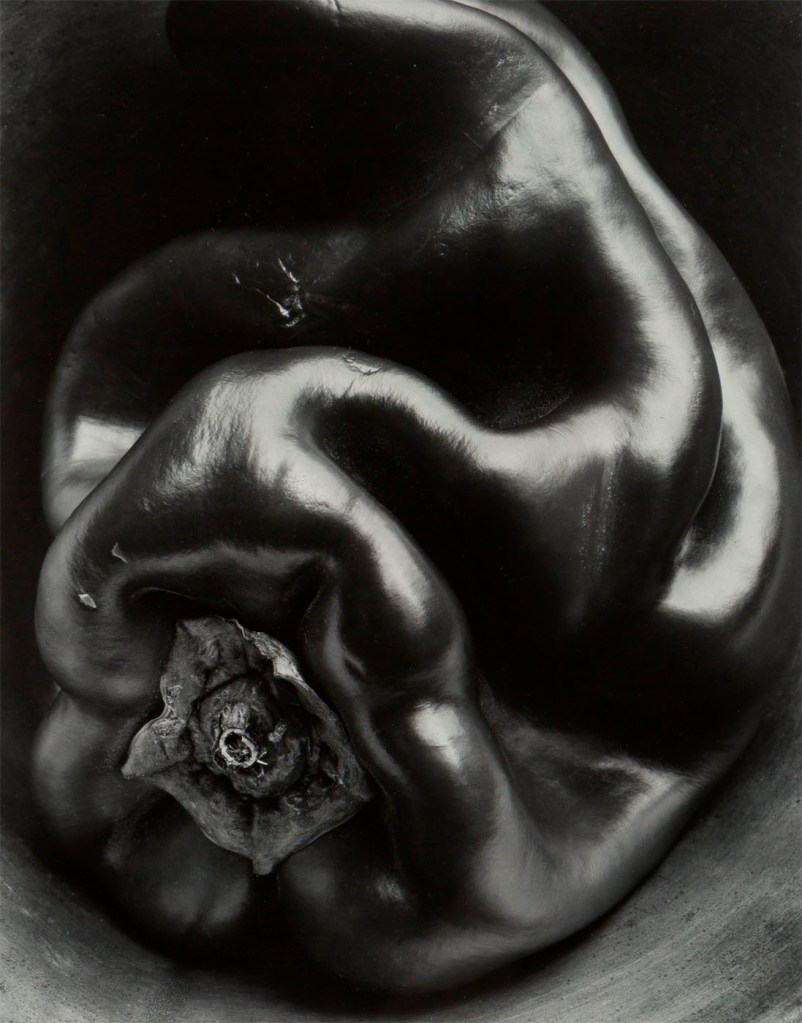

To tease out these under-examined connections, and de-emphasise the association of American photography of the 1930s with the unbiased documentation of real people and events, works by the five core CGF artists are interwoven with a diverse selection of photographs by their contemporaries, both iconic and overlooked, such as Walker Evans, Hiromu Kira, and Dorothea Lange. Edward Weston’s bold experimentation with forms both natural and man-made – exemplified by highly evocative works such as Pepper No. 35 (1930) and Egg Slicer (1930) that inspired Bass-Becking’s comment – blends harmoniously with contemporary prints from the community of Japanese-American photographers in Los Angeles that often supported Weston’s work. Examples of fashion and editorial photography, including colour images by Toni Frissell and Paul Outerbridge, draw connections across the galleries with photographs of airplanes, household items, and tourist sites made by seasoned artists and amateur hobbyists alike. Helen Levitt’s surreal tableaux on the streets of New York echo Berenice Abbott‘s studies of the metropolis with multiple layers of history jumbled into the same block. Ansel Adams’s pristine images of the Sierra Nevada hang alongside little-known photographs by Seema Weatherwax, his darkroom assistant in the late 1930s who was similarly enchanted with nature but developed a vision all her own. Despite gaining the respect of not only Adams, but also Weston, Lange, and Imogen Cunningham, Weatherwax shared her own work publicly for the first time in 2000 at the age of 95. Her photographs evidence her technical abilities and, not unlike her peers on view in this exhibition, find beauty in the everyday. Altogether, these photographs effectively illustrate Johnson’s three year exploration of the collection which revealed that despite the very real financial, political, and cultural challenges of the Great Depression, certain photographers chose not to focus on the camera’s cold mechanical precision, but rather used it as a medium to spark their imaginations – fusing reality and dream into one. …

The first exhibition curated by a CGF fellow, Reality Makes Them Dream is accompanied by a fully-illustrated catalogue. It features an essay by Johnson and contributions from the community of photography scholars at Stanford University – Kim Beil, associate director of the ITALIC arts program for undergraduates; Yechen Zhao (PhD in art history ’22); Anna Lee, photography curator for special collections at the Stanford Libraries; Rachel Heise Bolten (PhD in English ’22); Altair Brandon-Salmon (PhD candidate in art history); Marco Antonio Flores (PhD candidate in art history); and Maggie Dethloff, PhD, assistant curator of photography and new media at the Cantor.

Press release from the Cantor Arts Center

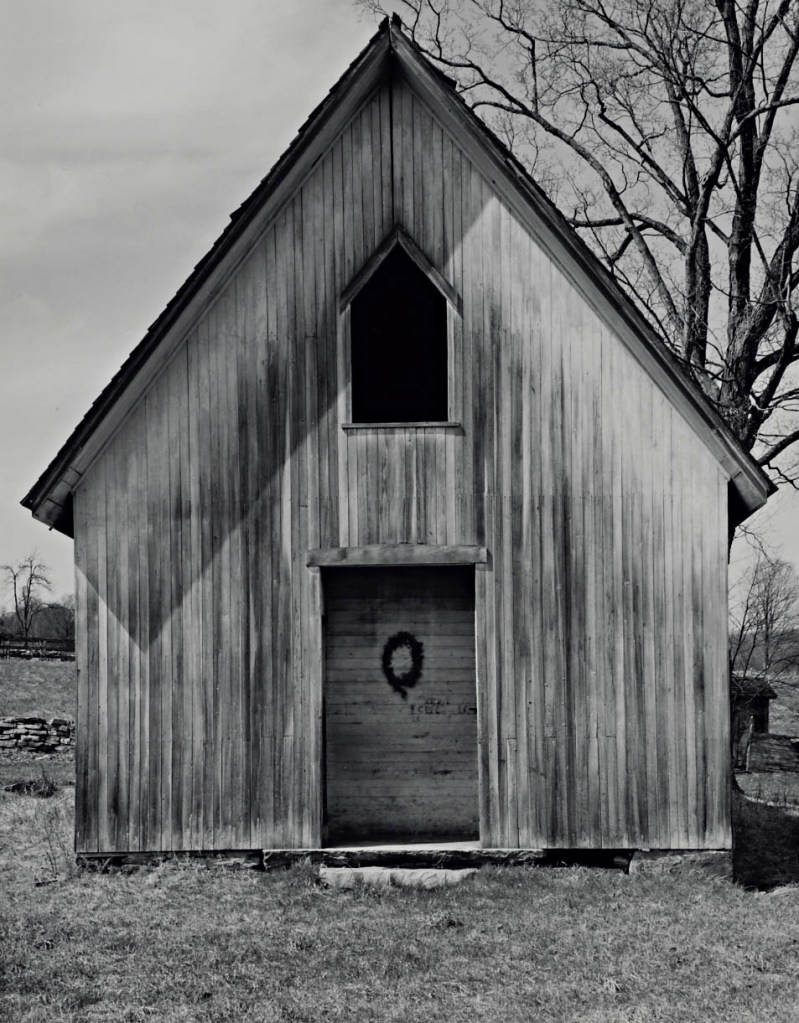

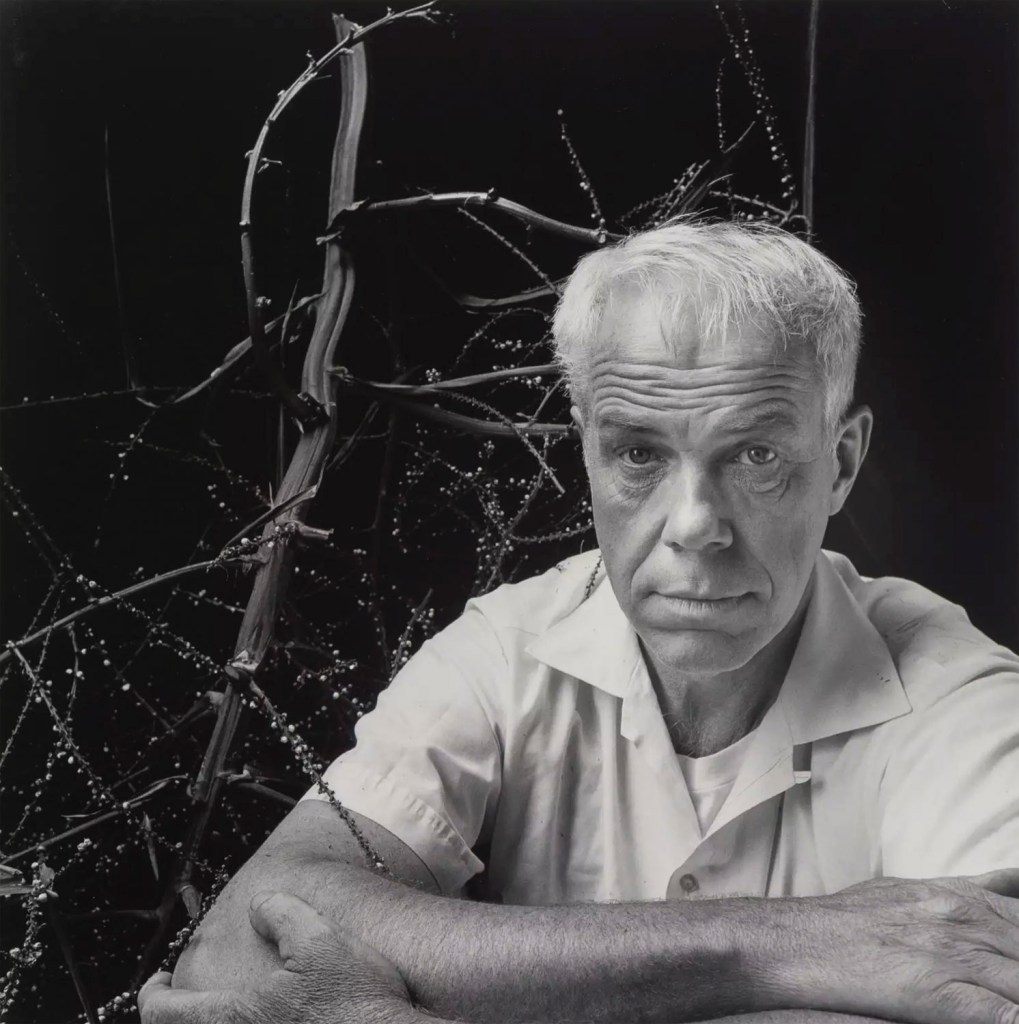

Wright Morris (American, 1910-1998)

Gano Grain Elevator, Western Kansas

1940, printed 1979-1981

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

In Dr. Josie R. Johnson’s exhibition … Johnson interweaves the Capital Group Foundation Collection images with additional works by other artists, building narratives that nuance our understanding of American photography in the 1930s. Her essay pushes against longstanding narratives that overemphasise the purity of straight photography and the veracity of documentary photography in this decade. Her research reveals instead that many artists used the medium of photography to fuse reality and dream into one.

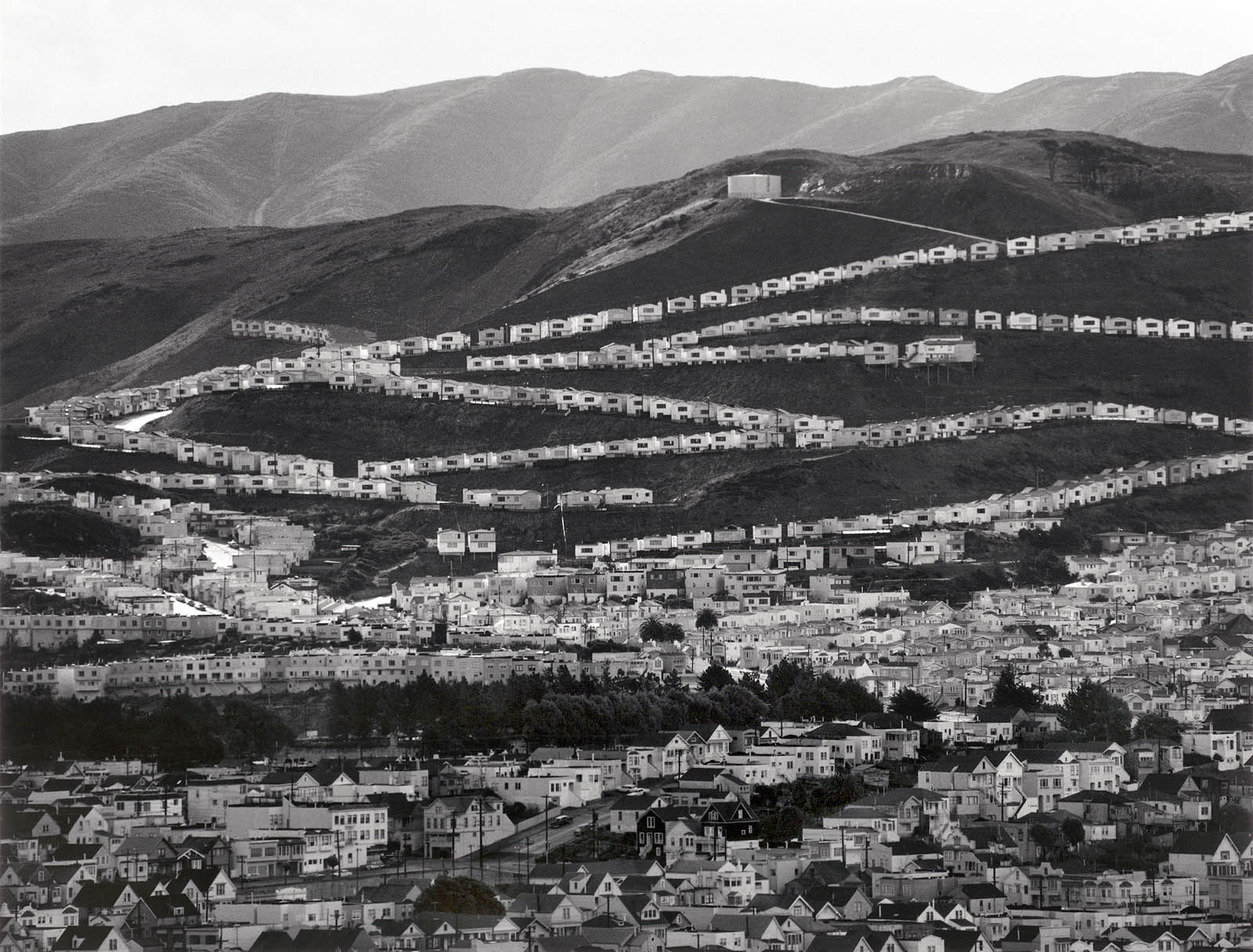

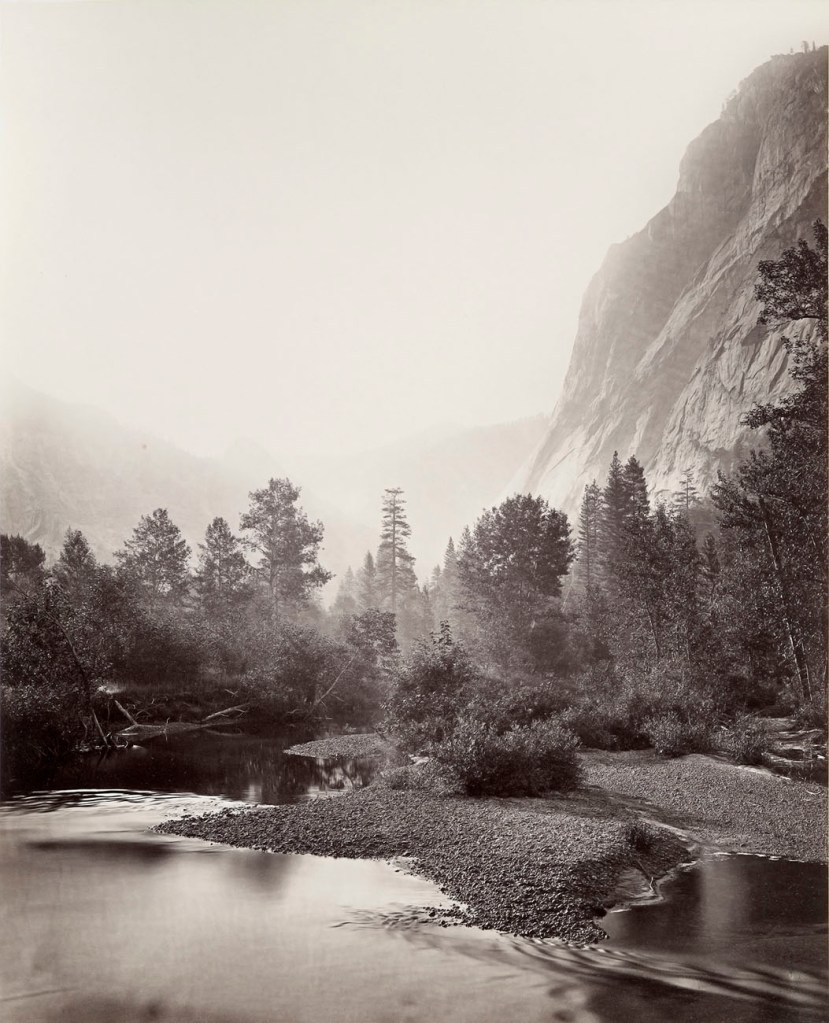

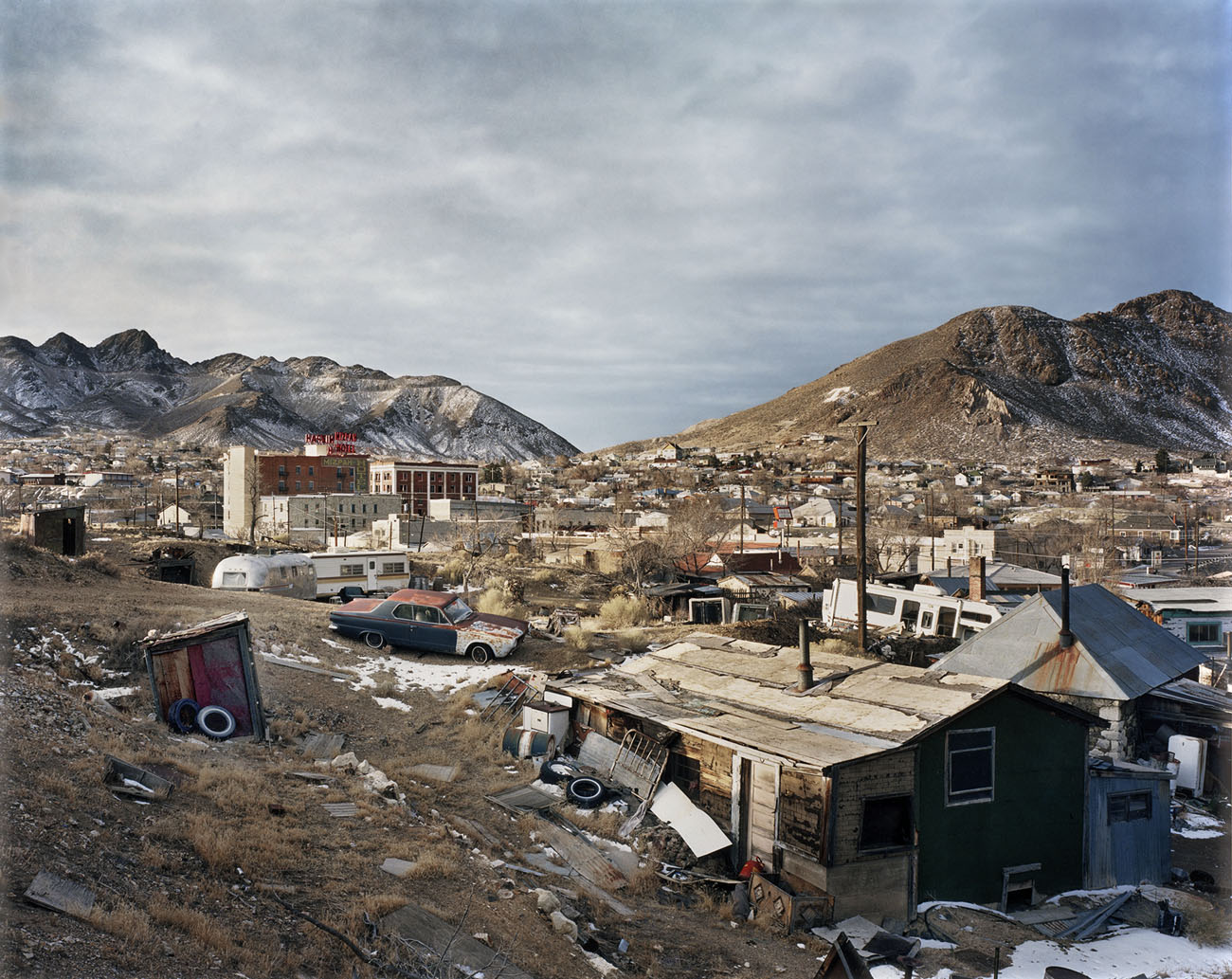

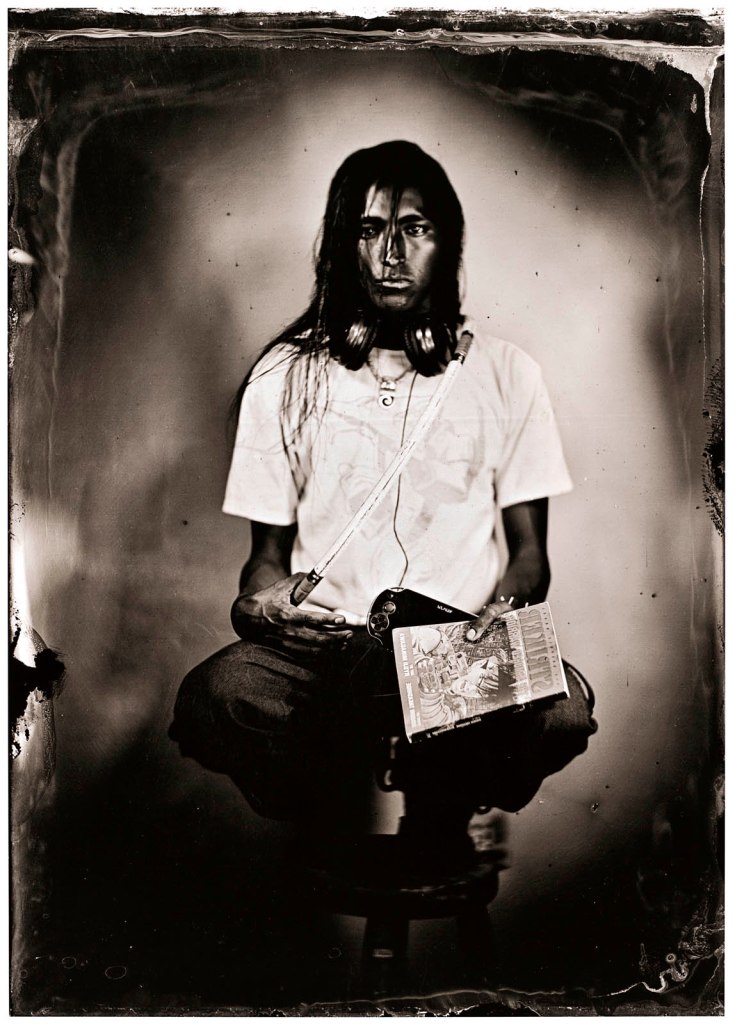

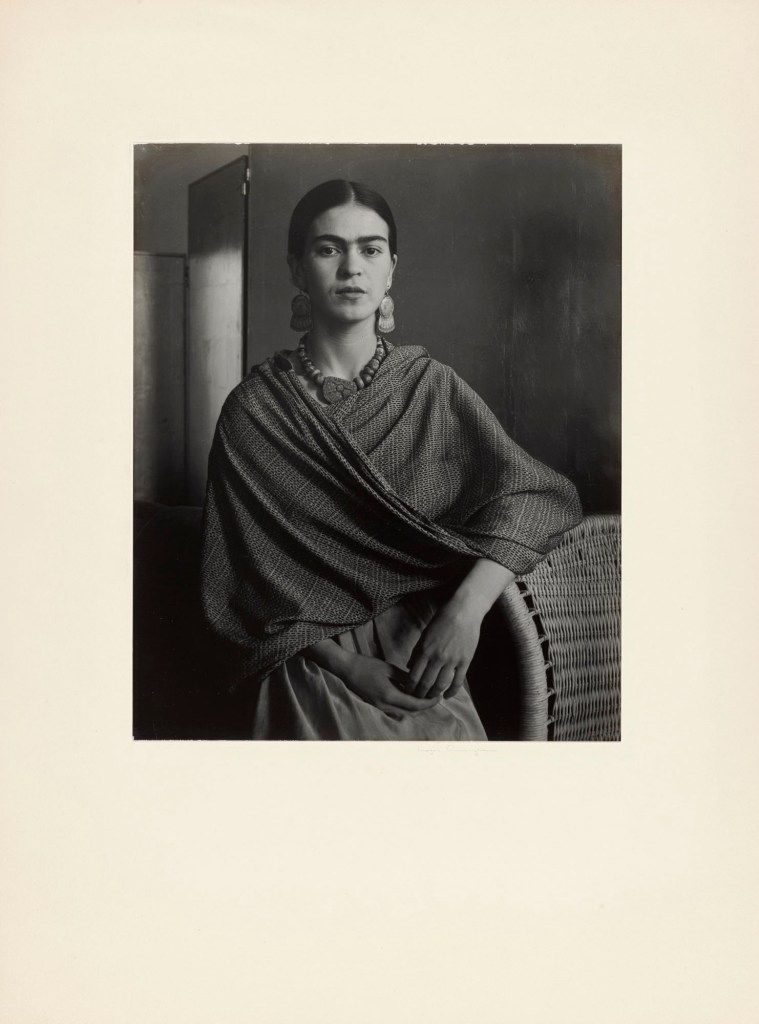

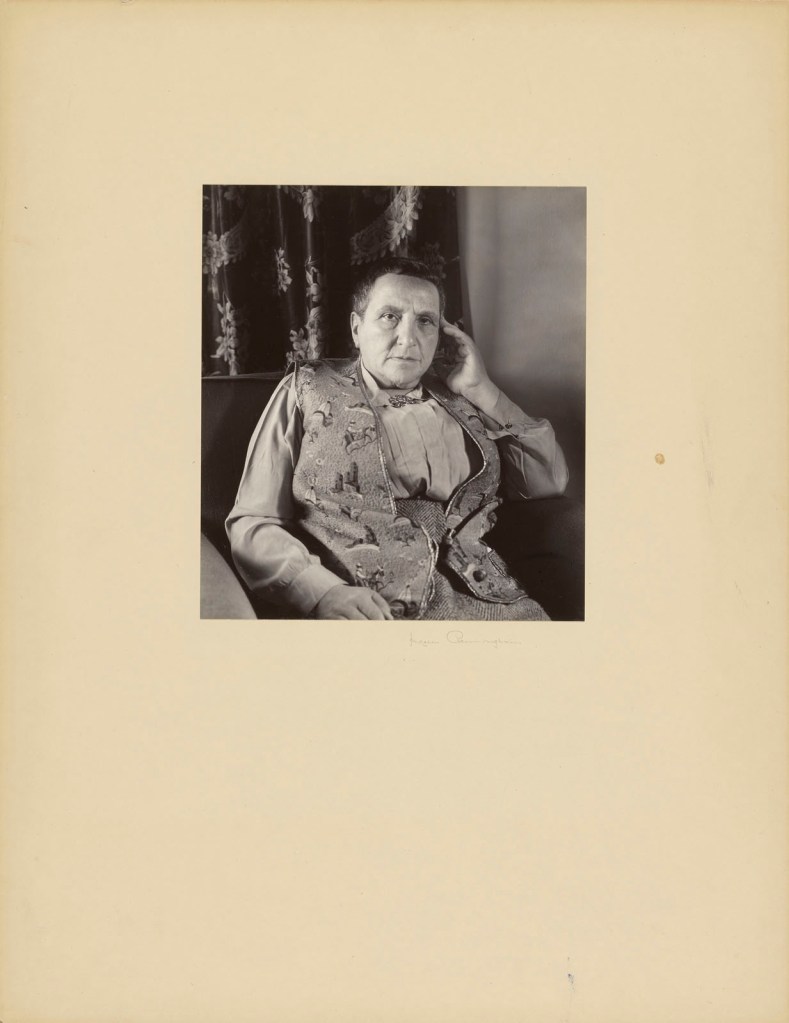

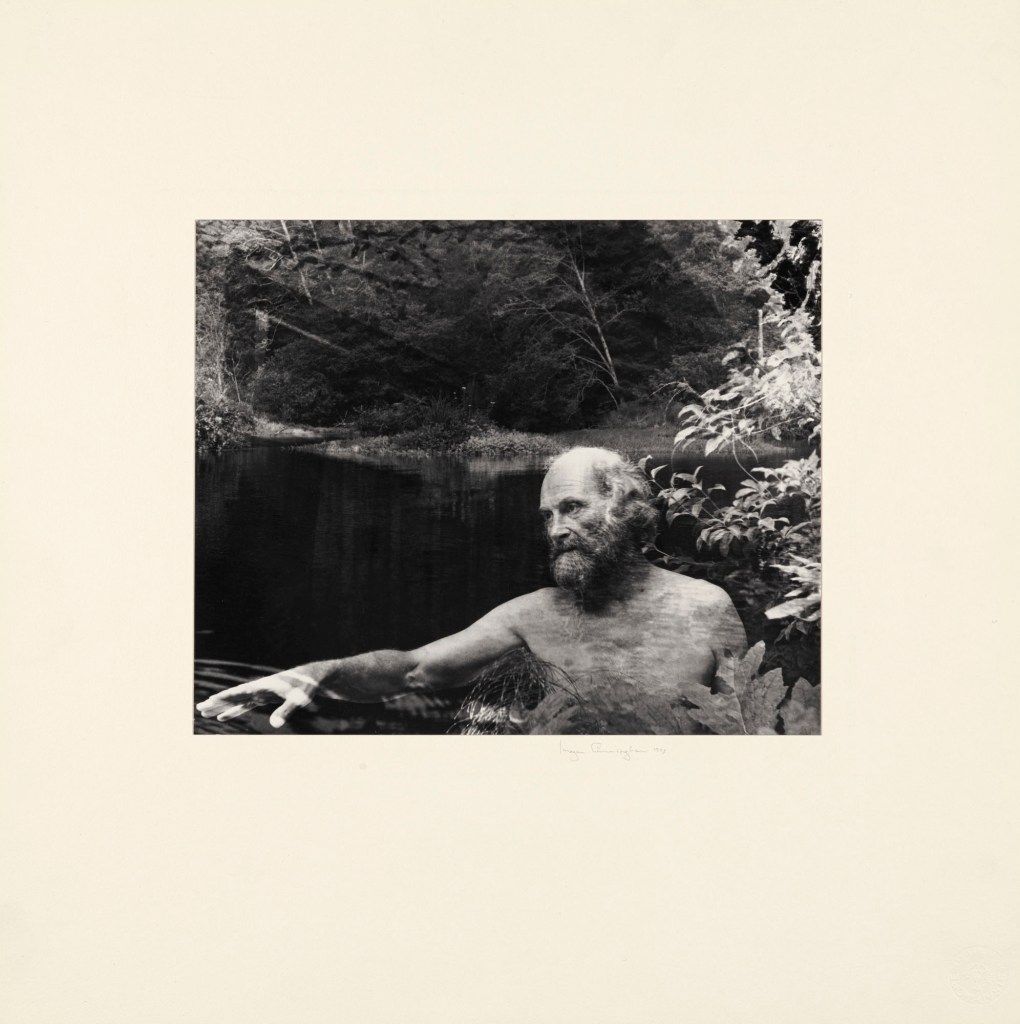

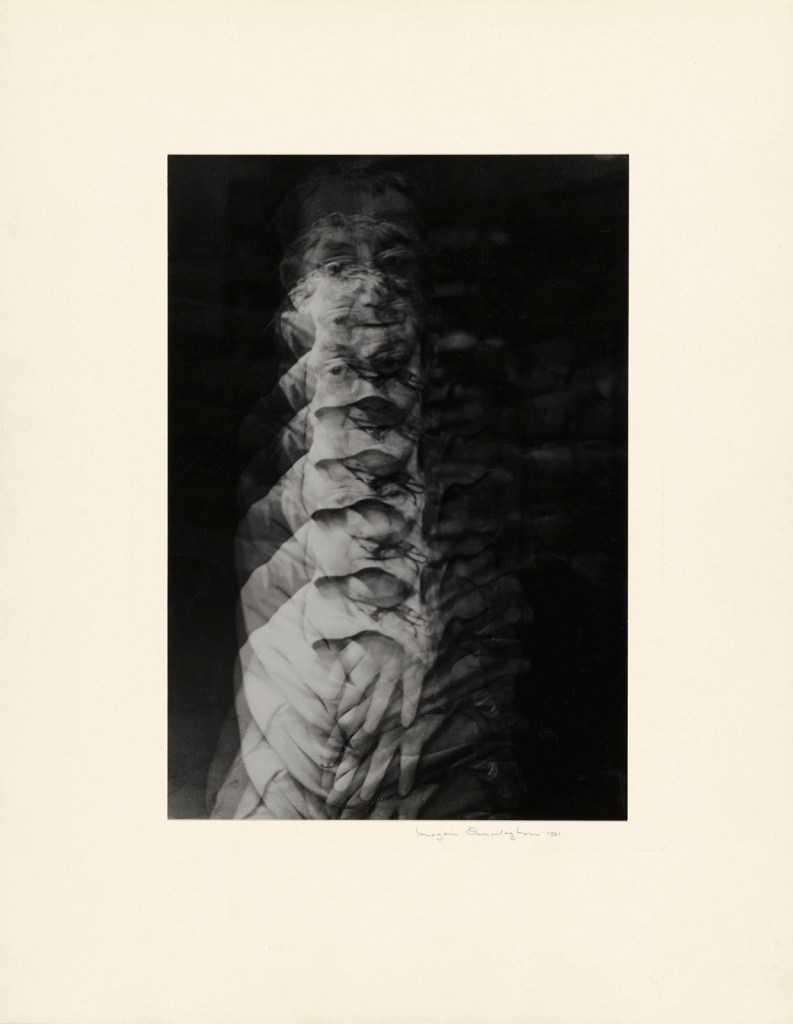

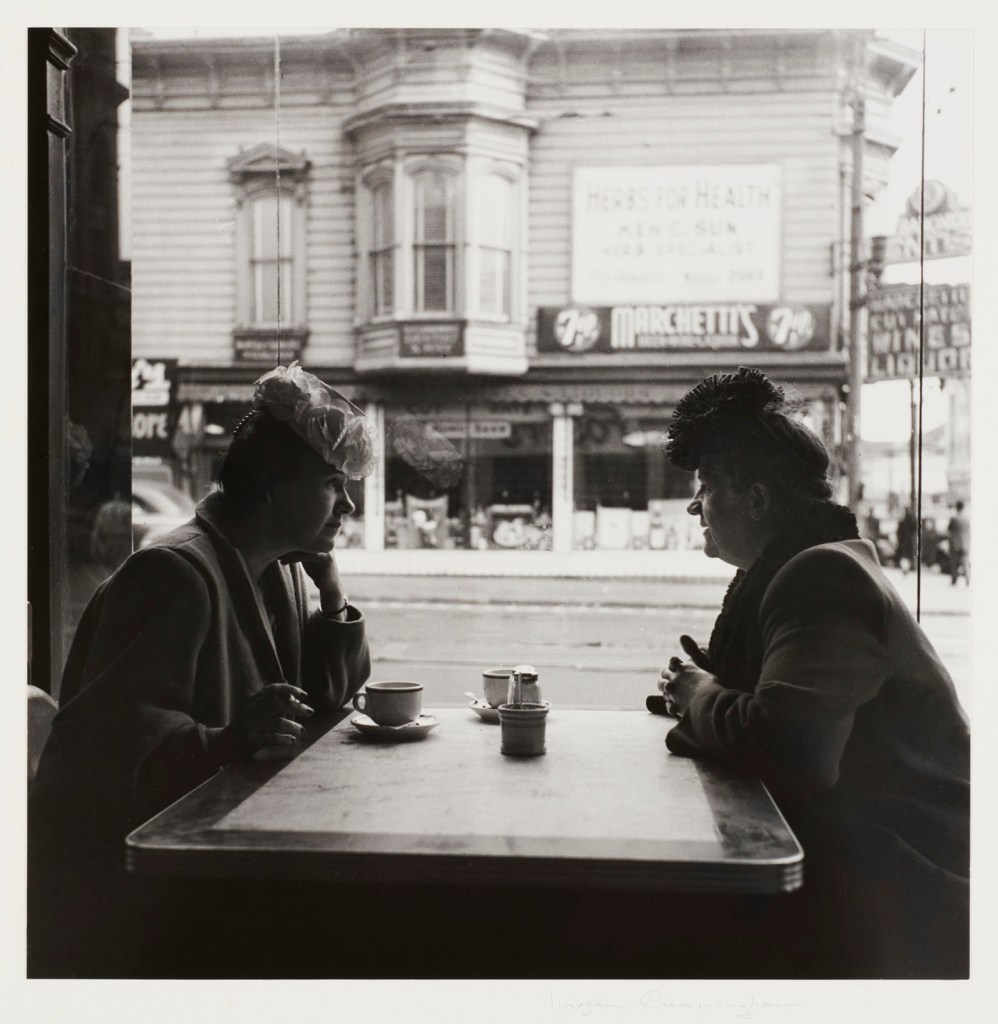

Johnson divides Reality Makes Them Dream into seven sections exploring subjects commonly photographed in the 1930s as being both real and dream-like. Looking beyond well-traveled approaches to photographs captured in the decade defined by the Great Depression, “Natural Wonders” features awe inspiring organic forms from still life and nature photography. “Divine Figures” presents methods of elevating the human figure to the status of a god-like being in portraiture, nude studies, dance photography, and photographs of modern labourers. “Everyday Splendors” explores the transformation of commonplace scenes and objects into vibrant masses of shapes and textures. The portraits, architectural photographs, and still life images in “Living Relics” exemplify the tendency of these photographers to depict emblems of a purer and more noble past that they hoped to reclaim. “The World of Tomorrow” considers the opposite end of the temporal spectrum, where photographers captured glimpses of a futuristic, machine-driven utopia in urban or industrial scenes. “Street Theater” encompasses street photography and urban architectural studies that approach their subjects as if they are actors and stage sets in their own make-believe world. Finally, “Surreal Encounters” highlights Surrealist strands in the work of American photographers as they emphasised the uncanny and fantastical in the physical world around them.

Veronica Roberts, Director of the Cantor Arts Center

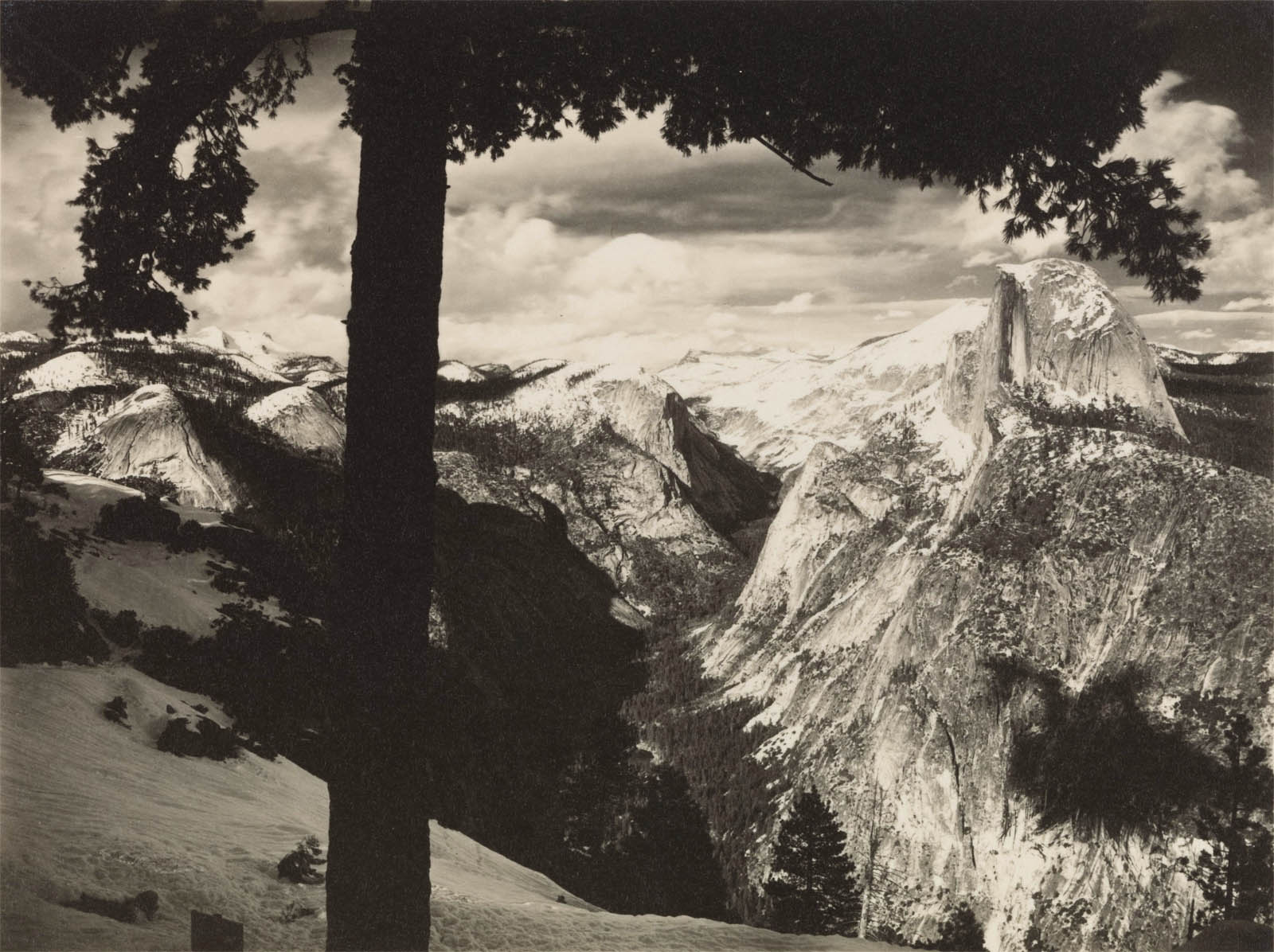

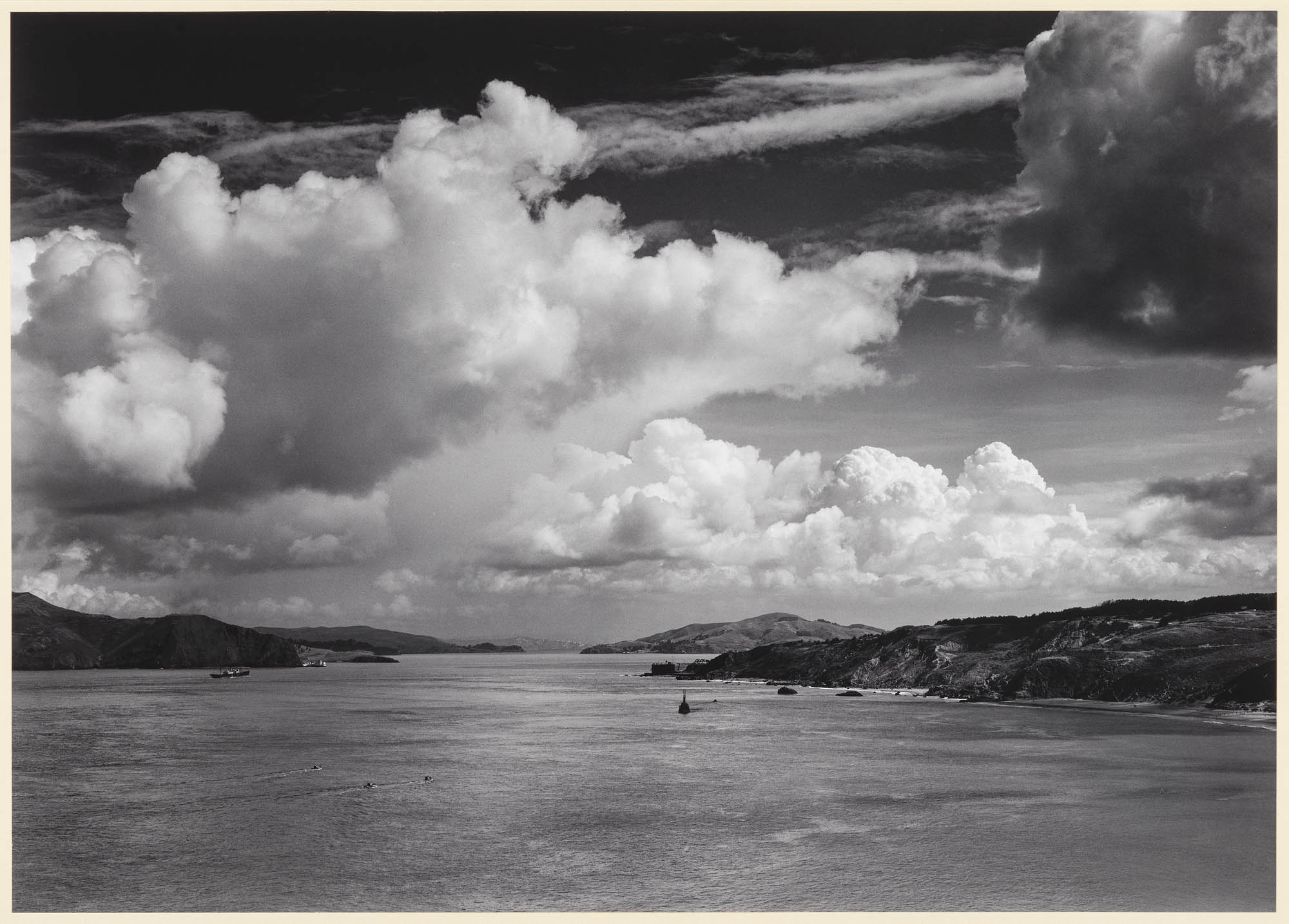

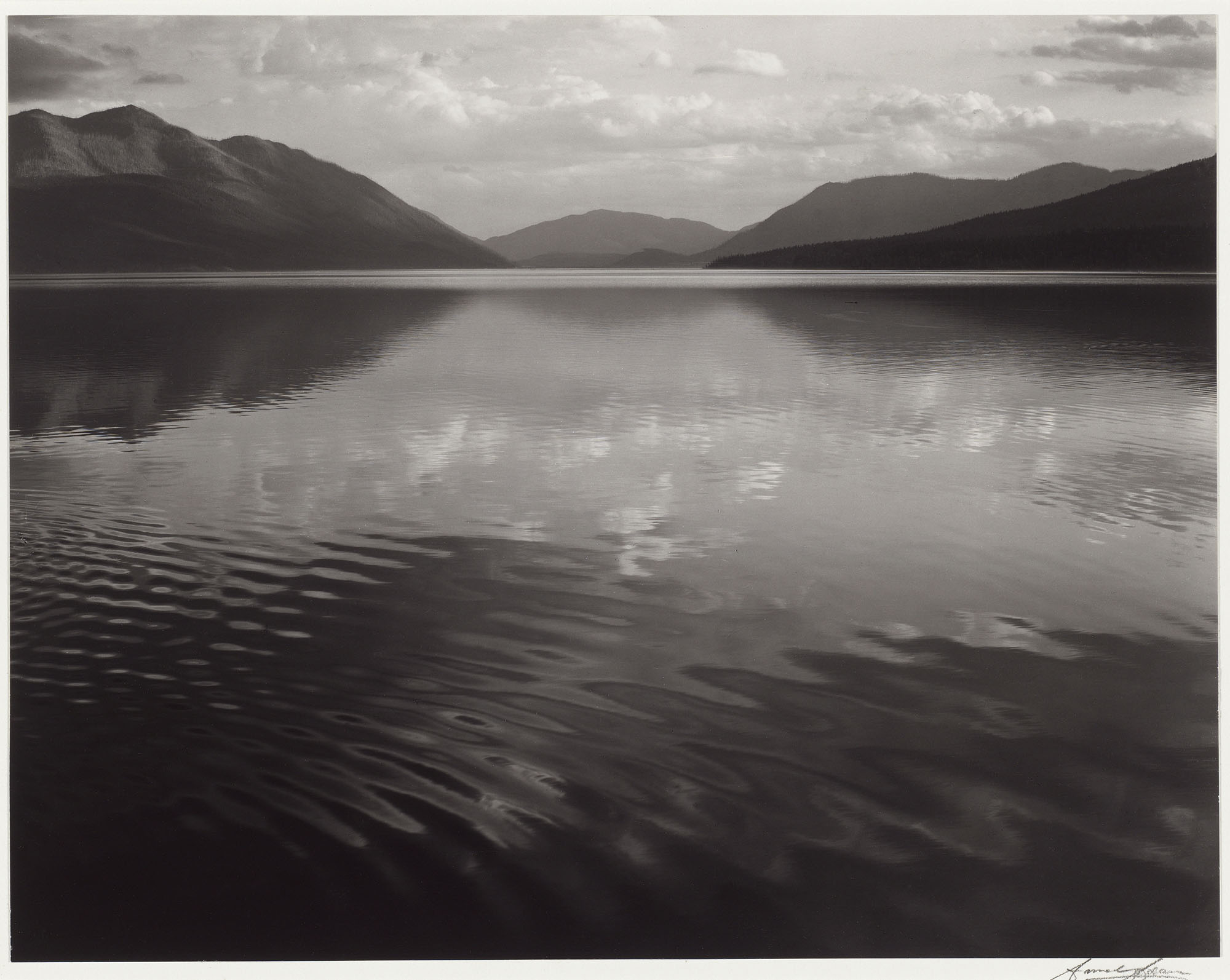

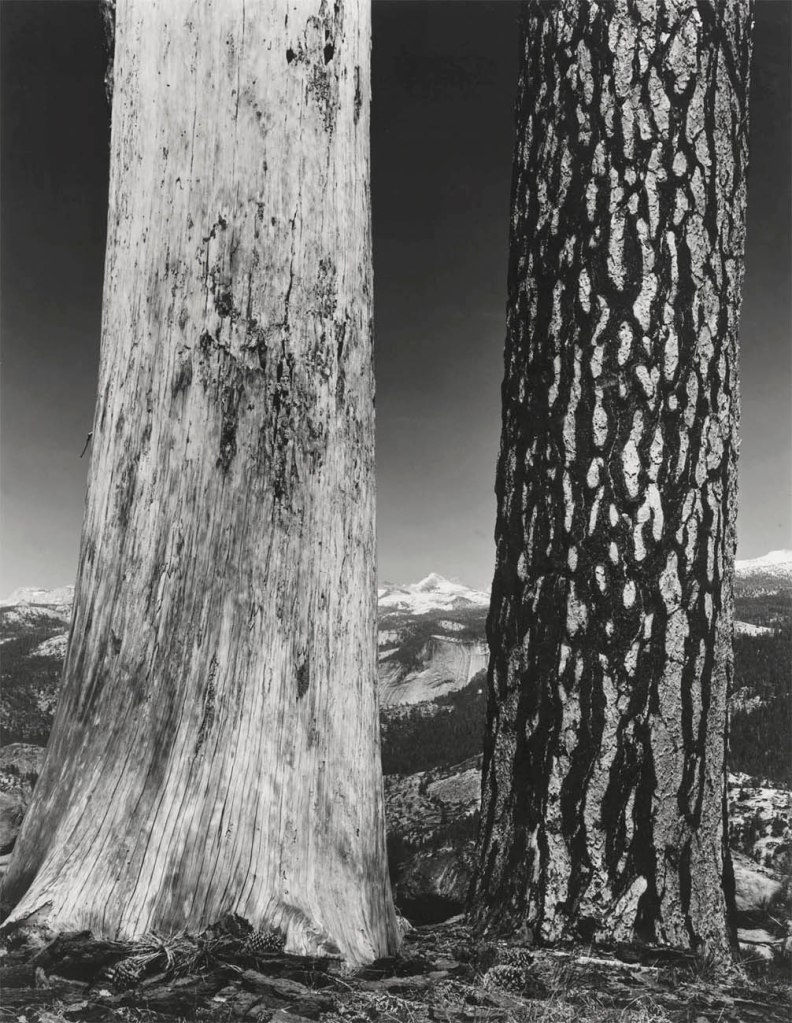

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Sculptor’s Tools, San Francisco, California

1930, printed c. 1974

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

In 1930, a meeting with the photographer Paul Strand inspired Ansel Adams to abandon the use of soft-focus camera settings and textured printing papers in pursuit of “absolute realism.” However, Adams did not renounce the photograph’s capacity to convey an artist’s imaginative vision; instead, he launched a crusade for photography to be recognised as a “pure art form.” This image of the tools belonging to the San Francisco sculptor Ralph Stackpole stages Adams’s main argument at the time: Photography is no less a form of art than sculpture, so long as the artist’s tools (a camera or a hammer and chisel) are employed directly, without imitating another medium.

Wall label from the exhibition

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

Sumner Healy Antique Shop

1936

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Judge Leonard Edwards

Cantor Arts Center Collection

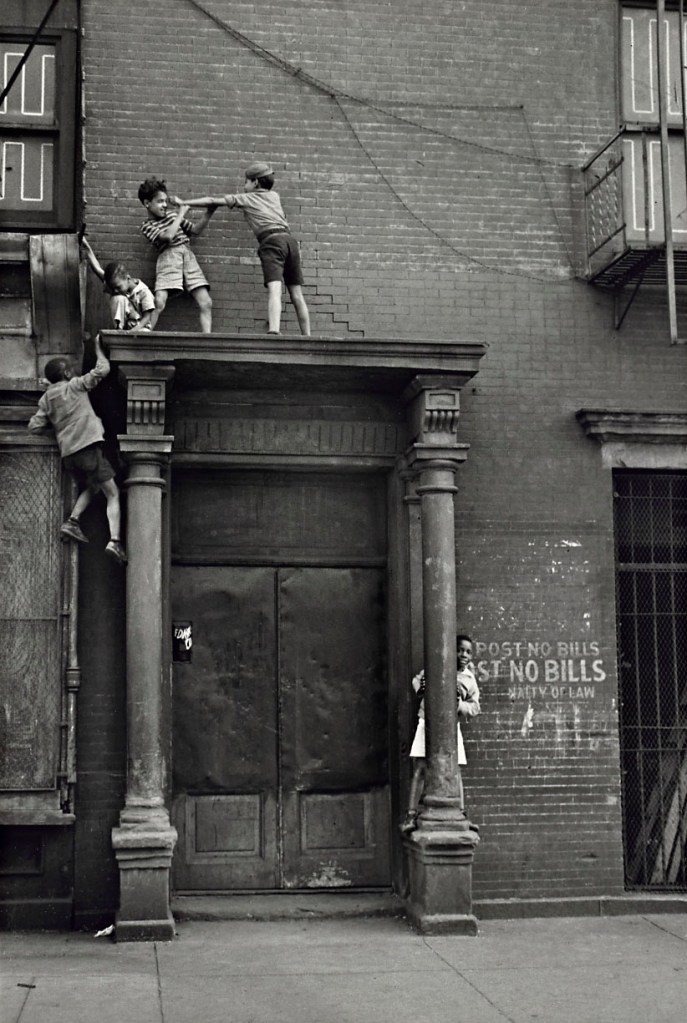

Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009)

New York

c. 1938

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Woven into this exhibition is a diverse selection of photographs by their contemporaries, adding breadth to this survey of American photography of the 1930s and presenting new narratives about artists and images, from the iconic to the overlooked. This project interprets the term “American” loosely, encompassing photographers who lived in the United States for extended periods but who did not necessarily hold citizenship, as well as locations including Alaska and Hawaii, which were then still US territories. Thirteen of the forty-two photographers featured in this catalogue were born outside the United States, reflecting diasporic patterns that brought Japanese immigrants in the early 1900s and European immigrants – especially Jews fleeing antisemitism – in the 1910s and mid-1930s.7 Many turned to photography as a way to earn a living, and their photographs often expressed their enchantment with the dramatic natural landscapes or unfamiliar cultural practices they encountered in their newly adopted nation.

Together, this material demonstrates that Bass-Becking’s idea [Bass-Becking used a curious phrase to describe the photography of his friend Edward Weston: “Reality makes him dream”] offers an interpretive lens for a much wider swath of photography than either he or Weston might have realized. Against the typical history of 1930s photography that views the work of this period as primarily documentary in style and purpose , this project contends that a key goal for artists of this period was to use photography to ignite the imagination, even while pursuing an increasingly transparent approach that mirrored the world as they saw it. From the delicate curve of a seashell to the jostle of a crowded city street, reality made the photographers and their audiences dream.

Footnote 7. Another ten were second- and/or third-generation immigrants.

Josie R. Johnson. “Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941,” in Josie R. Johnson. Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2023, p. 11.

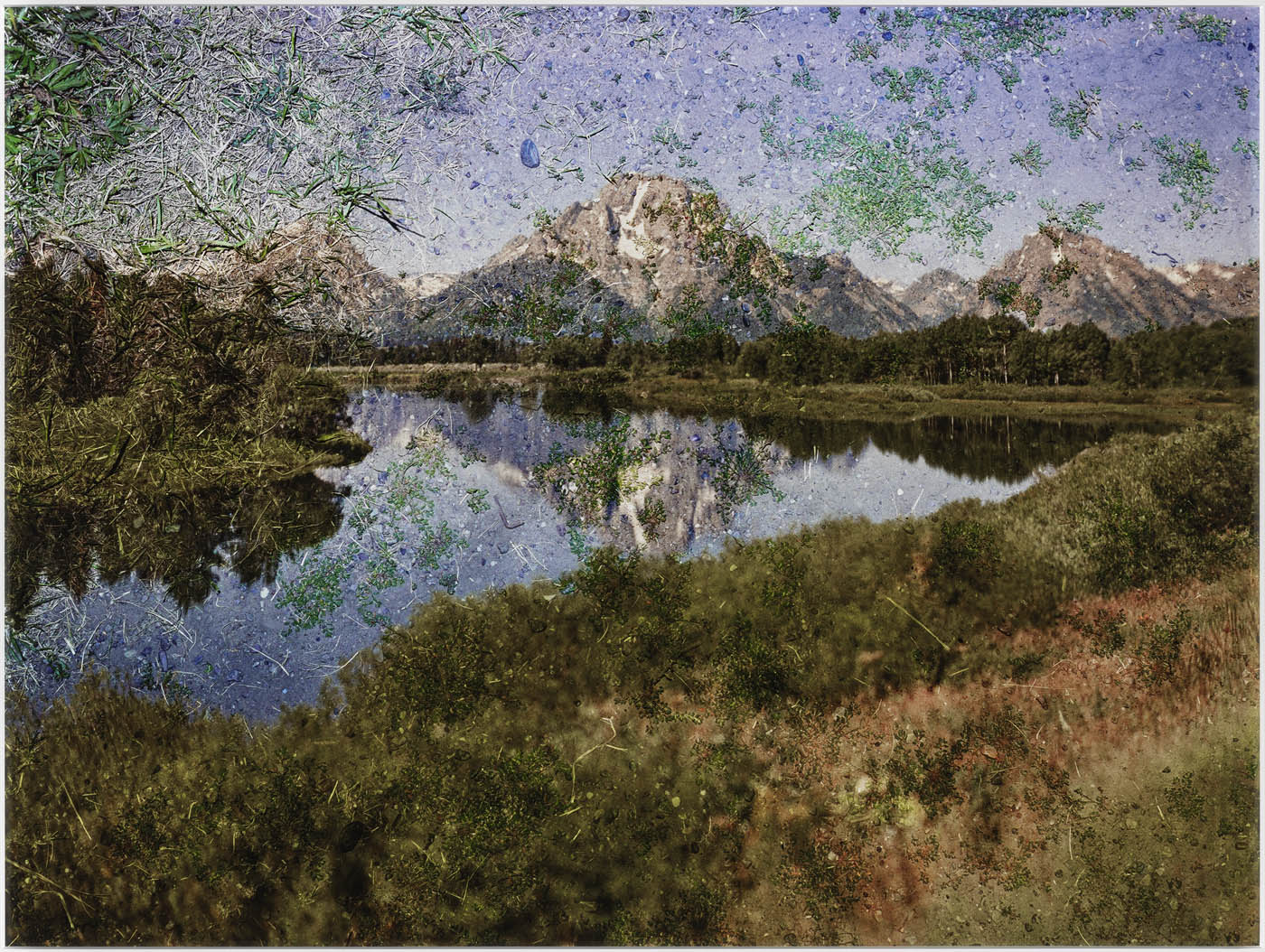

Natural Wonders

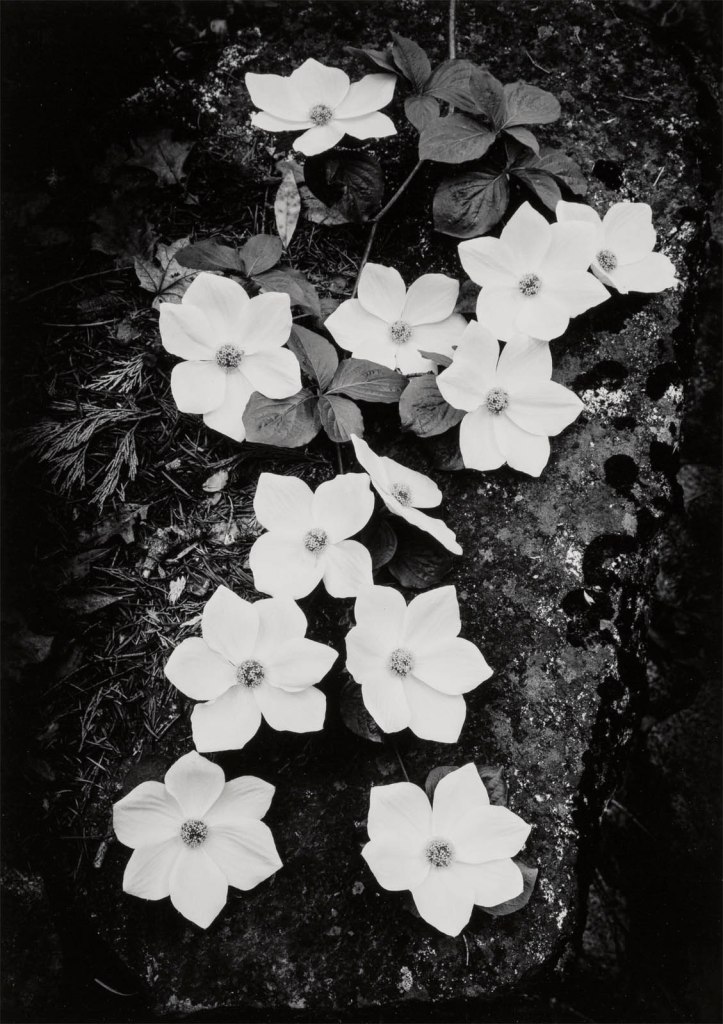

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Dogwood, Yosemite National Park, California

1938

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Ansel Adams is best known today for the majestic landscape photographs he made throughout his life, but in the 1930s he gravitated toward tightly framed images of a more intimate scale. This photograph of dogwood blossoms exemplifies Adams’s close looking at nature from this period. Even among the grand vistas of Yosemite, he often turned his lens to humbler sights while retaining the same density of detail across the picture plane, illuminating multitudes in a patch of moss or a pile of pine needles. Adams explained at the time: “Honest simplicity and maximum emotional statement suggests the basis of a critical definition of photography as an Art Form – that is, as a means of more than factual statement.”

Wall label from the exhibition

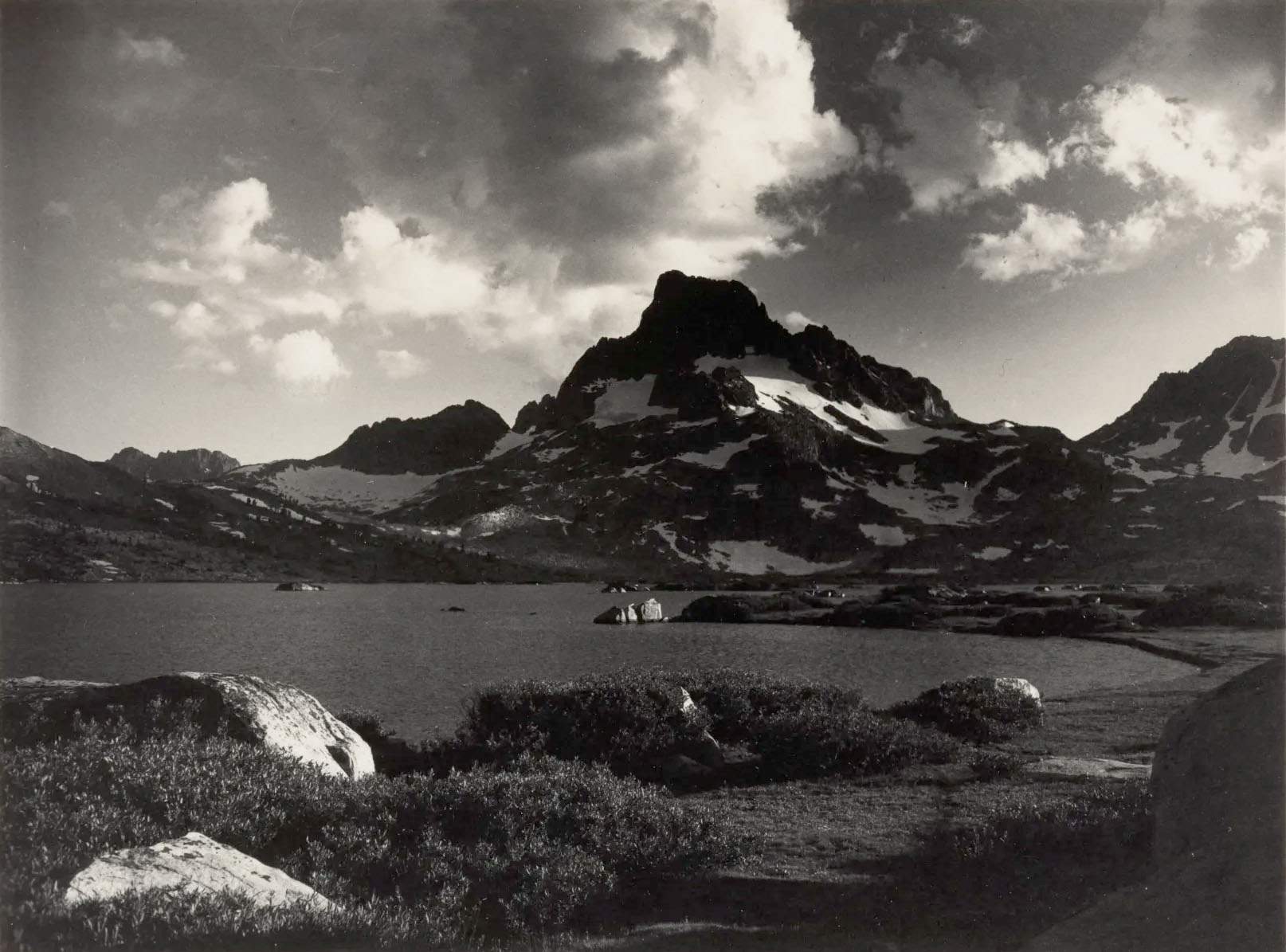

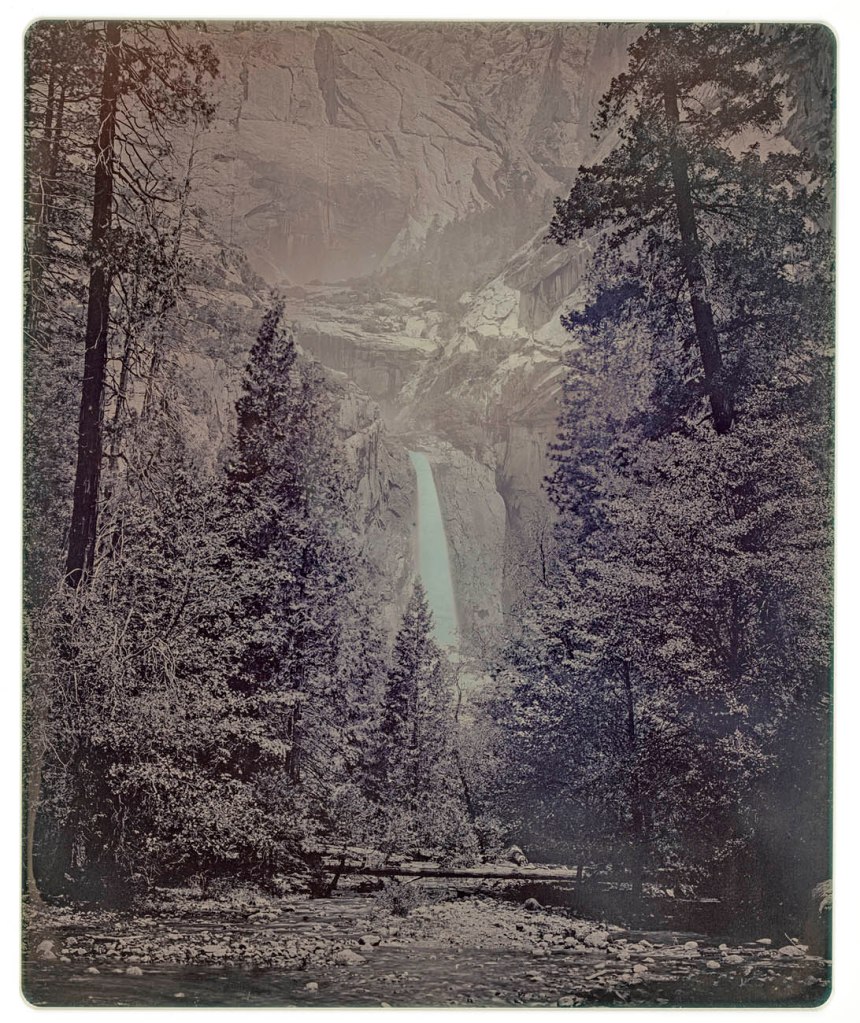

Cedric Wright (American, 1889-1959)

Wildflowers

1930s-1940s

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

George Cedric Wright (April 13, 1889 – 1959) was an American violinist and a wilderness photographer of the High Sierra. He was Ansel Adams’s mentor and best friend for decades, and accompanied Adams when three of his most famous photographs were taken. He was a longtime participant in the annual wilderness High Trips sponsored by the Sierra Club. …

In an article published in 1957, which included eight full-page photographs, Wright described his thoughts about how high mountain beauty resembles great music: “Beauty haunts the high country like a majestic hymn, sings in cold sunny air, the brilliant mountain air – makes of sunlight a living thing – floats in cloud forms – filters changing floods of light ever clothing the mountains anew. Beauty arrives in deep voice of river and wind through forest, swelling the chorus, giving sonority universal proportions.”[Wright, Cedric. “Trail Song: An Artist’s Profession of Faith” Sierra Club Bulletin. San Francisco: Sierra Club. 42 (6): 50-53]. He dedicated these words to Sierra Club leader William Edward Colby, and they became part of the introduction to Wright’s posthumous book, Words of the Earth.

Text from the Wikipedia website

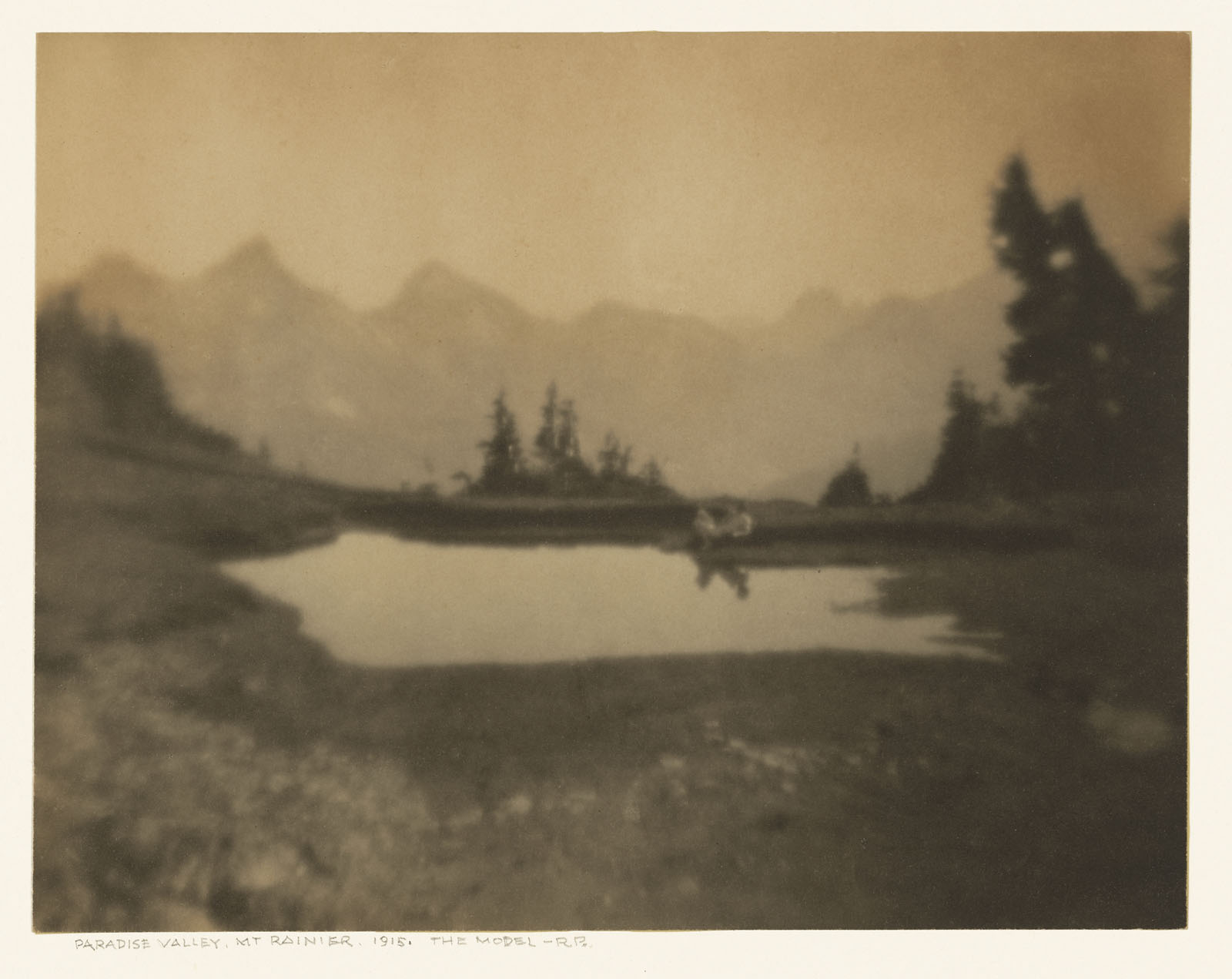

Bradford Washburn (American, 1910-2007)

Mount La Perouse

c. 1933

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries

Bradford Washburn became a well-known mountaineer and aerial photographer while still in college. In the early 1930s, he climbed and surveyed multiple peaks in the Fairweather Range of southeastern Alaska, including Mount La Perouse. Although Washburn’s photographs functioned as topographical records and route maps, he also displayed them in artistic contexts, where they elicited deeply poetic and emotional responses from viewers. In the 1940 issue of U.S. Camera Magazine, an editor wrote of Washburn’s Alaskan photography: “Sea and mountain and plain, join island and cape and bay in a beauty that is the true setting for the fantasy of northern lights and midnight sun. … Here is an America that is no more a last frontier or hinterland, but a fruitful part of America, present – a glowing promise to America, future.”

Wall label from the exhibition

Henry Bradford Washburn Jr. (June 7, 1910 – January 10, 2007) was an American explorer, mountaineer, photographer, and cartographer. He established the Boston Museum of Science, served as its director from 1939-1980, and from 1985 until his death served as its Honorary Director (a lifetime appointment). Bradford married Barbara Polk in 1940, they honeymooned in Alaska making the first ascent of Mount Bertha together.

Washburn is especially noted for exploits in four areas.

1/ He was one of the leading American mountaineers in the 1920s through the 1950s, putting up first ascents and new routes on many major Alaskan peaks, often with his wife, Barbara Washburn, one of the pioneers among female mountaineers and the first woman to summit Denali (Mount McKinley).

2/ He pioneered the use of aerial photography in the analysis of mountains and in planning mountaineering expeditions. His thousands of striking black-and-white photos, mostly of Alaskan peaks and glaciers, are known for their wealth of informative detail and their artistry. They are the reference standard for route photos of Alaskan climbs.

3/ He was responsible for creating maps of various mountain ranges, including Denali, Mount Everest, and the Presidential Range in New Hampshire.

4/ His stewardship of the Boston Museum of Science.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Hy Hirsh (American, 1911-1961)

Untitled

Late 1930s

Gelatin silver print

Dennis and Annie Reed Collection

Hyman Hirsh (October 11, 1911, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – November 1961, Paris, France), was an American photographer and experimental filmmaker. He is regarded as a visual music filmmaker, as well as one of the first filmmakers to use electronic imagery (filmed oscilloscope patterns) in a film. …

Photography style

Hirsh’s early photographs were influenced by California photography movement Group f/64, who had first exhibited in 1932 at the de Young Museum where Hirsh later worked. In 1932. Hirsh’s photo work from that period used sharply focused black and white renderings and little manipulation in their process. Hirsh was then influenced by the social documentary of the Farm Security Administration [FSA] photographers who recorded the impact of the Great Depression on displaced workers and their families. Hirsh followed suit, exploring social issues through visages of vacant lots, rusted machinery, and other images of urban decay. Recognition for these photographs led to seven exhibitions in Los Angeles and San Francisco from 1935 to 1955. A 1936 group show entitled “Seven Photographers” at L.A.’s Stanley Rose Gallery put him alongside the leading figures of West Coast photography, including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston and Brett Weston. Hirsh also appeared in the publication U.S. Camera in 1936, 1937 and 1939.

In 1943 San Francisco Museum of Art featured Hirsh in a solo exhibition. By now Hirsh had moved away from the straight-ahead aesthetic of Ansel Adams and Group f64, and his artistic photography took more cues from the world of experimental film. He made surrealist self-portraits by superimposing negatives of himself with broken sheets of glass. Later in Paris, as a study for one of his films, he shot colour slides of old wall posters that were peeling, exposing layers of posters underneath.

Text from the Wikipedia website

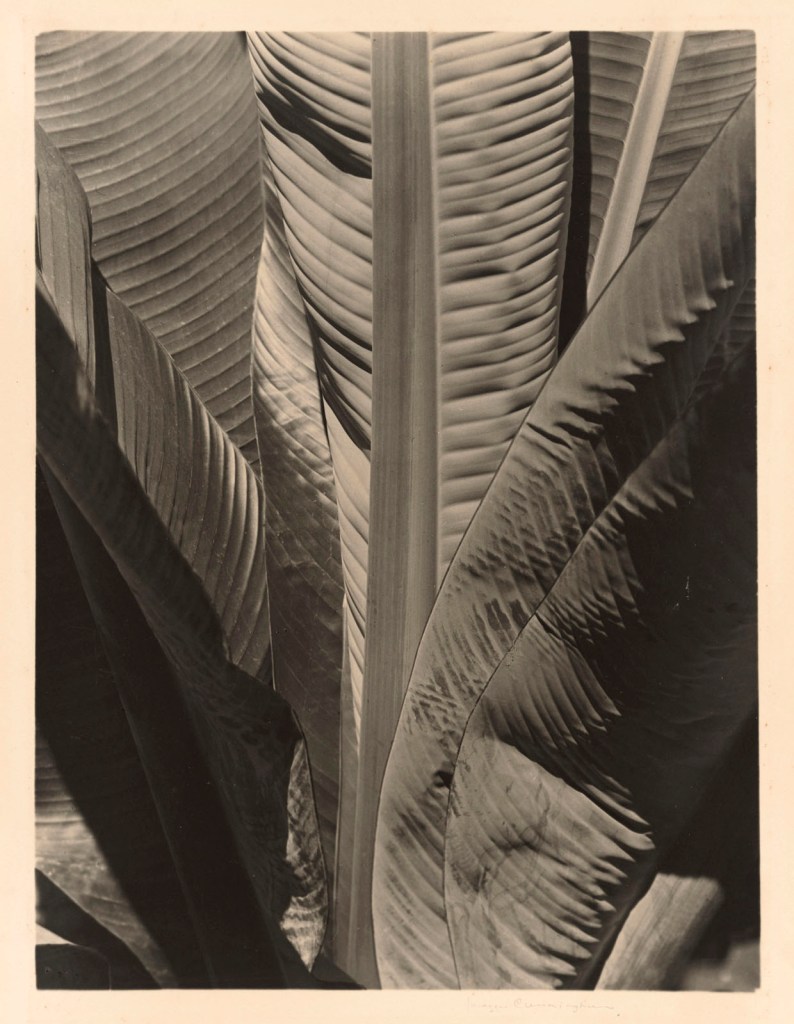

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Bananas

1930

Gelatin silver print

Dennis and Annie Reed Collection

Despite his many accolades, Edward Weston struggled to support himself throughout his career as a photographer. He found an important group of patrons in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo, where several artist groups sustained a lively community of photographers in the 1920s and ’30s. The play of light, movement, and space in Shinsaku Izumi’s The Shadow (below) exemplifies their experimental ethos. In this context, the photographer Toyo Miyatake (1895-1979) organised three exhibitions of Weston’s photography between 1925 and 1931. At the final exhibition, he purchased this print (above) from Weston, perhaps because he shared Weston’s excitement for the pictorial possibilities of the rhythms and textures in a bunch of bananas.

Wall label from the exhibition

Marion Post Wolcott (American, 1910-1990)

Cornshocks and fences on farm near Marion, Virginia

1940

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Michael and Sheila Wolcott

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Marion Post Wolcott (June 7, 1910 – November 24, 1990) was an American photographer who worked for the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression documenting poverty, the Jim Crow South, and deprivation. …

Post trained as a teacher, and went to work in a small town in Massachusetts. Here she saw the reality of the Depression and the problems of the poor. When the school closed she went to Europe to study with her sister Helen. Helen was studying with Trude Fleischmann, a Viennese photographer. Marion Post showed Fleischmann some of her photographs and was told to stick to photography.

Career

While in Vienna she saw some of the Nazi attacks on the Jewish population and was horrified. Soon she and her sister had to return to America for safety. She went back to teaching but also continued her photography and became involved in the anti-fascist movement. At the New York Photo League she met Ralph Steiner and Paul Strand who encouraged her. When she found that the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin kept sending her to do “ladies’ stories”, Ralph Steiner took her portfolio to show Roy Stryker, head of the photography division of the Farm Security Administration, and Paul Strand wrote a letter of recommendation. Stryker was impressed by her work and hired her immediately.

Post’s photographs for the FSA often explore the political aspects of poverty and deprivation. They also often find humour in the situations she encountered.

In 1941 she met Leon Oliver Wolcott, deputy director of war relations for the U. S. Department of Agriculture under Franklin Roosevelt. They married, and Marion Post Wolcott continued her assignments for the FSA, but resigned shortly thereafter in February 1942. Wolcott found it difficult to fit in her photography around raising a family and a great deal of traveling and living overseas.

In the 1970s, a renewed interest in Post Wolcott’s images among scholars rekindled her own interest in photography. In 1978, Wolcott mounted her first solo exhibition in California, and by the 1980s the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art began to collect her photographs. The first monograph on Marion Post Wolcott’s work was published in 1983. Wolcott was an advocate for women’s rights; in 1986, Wolcott said: “Women have come a long way, but not far enough. … Speak with your images from your heart and soul” (Women in Photography Conference, Syracuse, N.Y.).

Text from the Wikipedia website

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Pepper No. 35

1930, printed 1952-1955 by Brett Weston

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

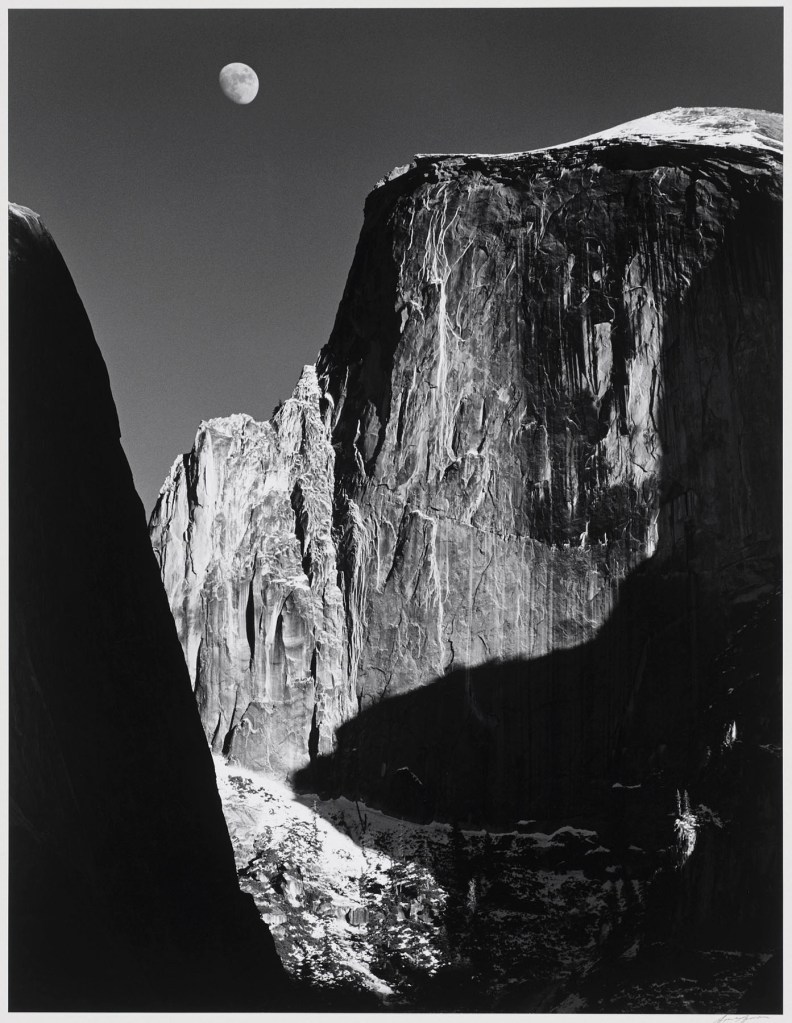

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

High Country Crags and Moon, Sunrise, Kings Canyon National Park, California

c. 1935, printed 1979

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Divine Figures

Peter Stackpole (American, 1913-1997)

Overview of the City

1935

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Ayleen Ito Lee

Cantor Arts Center Collection

In 1935, 25 of Stackpole’s bridge photographs were shown at the San Francisco Museum of Art.

Peter Stackpole (1913-1997) was an American photographer. Along with Alfred Eisenstaedt, Margaret Bourke-White, and Thomas McAvoy, he was one of Life Magazine‘s first staff photographers and remained with the publication until 1960. He won a George Polk Award in 1954 for a photograph taken 100 feet underwater, and taught photography at the Academy of Art University. He also wrote a column in U.S. Camera for fifteen years. He was the son of sculptor Ralph Stackpole.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Peter Stackpole (American, 1913-1997)

Mother and Daughter

1934

Gelatin silver print

Cantor Arts Center Collection

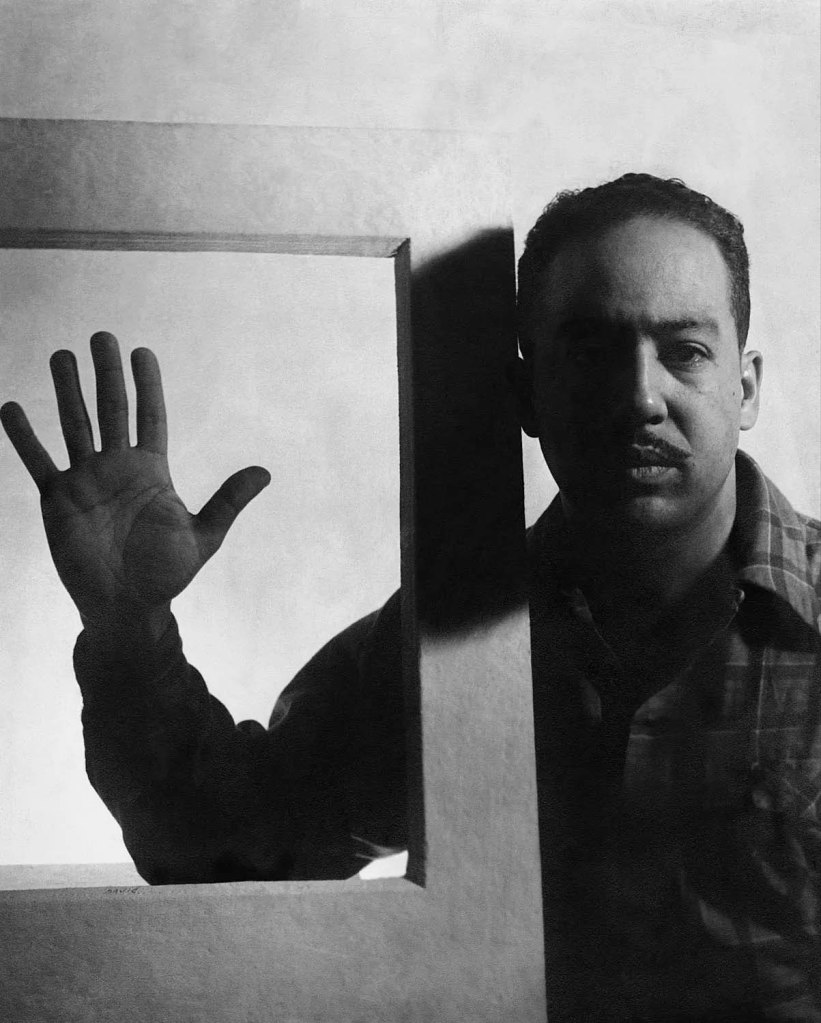

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Langston Hughes, Chicago, Illinois, 1941

1941, printed 2002-2003

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

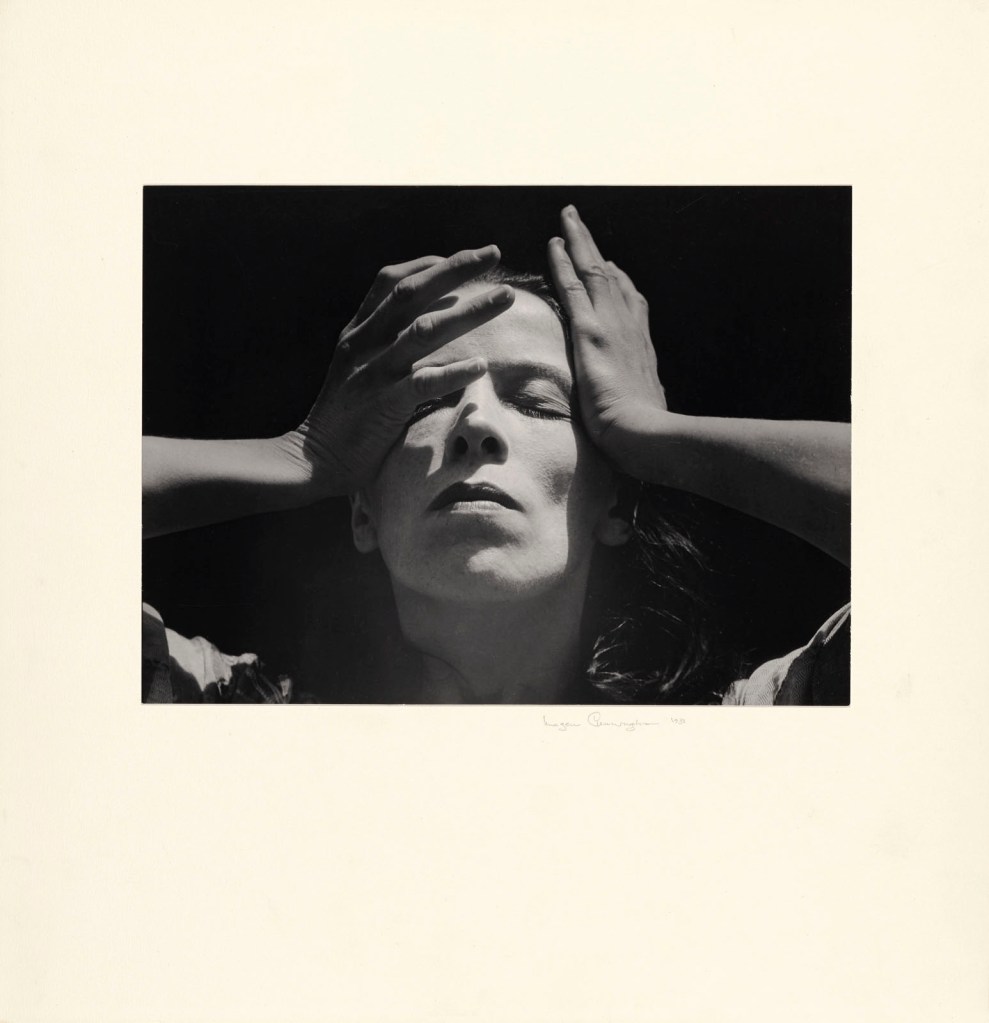

Barbara Morgan (American, 1900-1992)

Martha Graham – Ekstasis (Torso)

1935

Gelatin silver print

Given in memory of Belva Kibler by Barbara Morgan

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Barbara Morgan first attended a performance by Martha Graham’s modern dance company in 1935. The experience so deeply impressed her that she began photographing Graham and her fellow dancers regularly, becoming a recognised expert in the genre within a few years. Morgan typically captured a dancer’s entire body, but for Graham’s solo in Ekstasis, she explained: “When by moving a light which cast a certain shadow I suddenly felt a heroic scale evoked. … The torso expressed it all, and I felt as if I were on a lonely shore between Egypt and archaic Greece discovering a forgotten Venus.”

Wall label from the exhibition

John Gutmann (American born Germany, 1905-1998)

Class, Olympic High Diving Champion, Marjorie Gestring

1937

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Marjorie Gestring, a future Stanford undergraduate from Los Angeles, won the 1936 Olympic gold medal in women’s springboard diving at age 13. John Gutmann photographed Gestring the following spring at a diving exhibition held as part of the weeklong festivities for the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge. For Gutmann, the “rigid geometry” of her dives struck him as an “absolutely modern machine style.” More broadly, his image of Gestring soaring through the air captures the ethos of a moment when, having just completed the longest suspension bridge in the world, humans seemed capable of any accomplishment.

Wall label from the exhibition

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Nude (Charis) Floating

1939, printed 1952-1955 by Brett Weston

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Herbert Matter (American born Switzerland, 1907-1984)

Untitled

1940

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries

Herbert Matter (April 25, 1907 – May 8, 1984) was a Swiss-born American photographer and graphic designer known for his pioneering use of photomontage in commercial art. Matter’s innovative and experimental work helped shape the vocabulary of 20th-century graphic design. …

As a photographer, Matter won acclaim for his purely visual approach. A master technician, he used every method available to achieve his vision of light, form and texture. Manipulation of the negative, retouching, cropping, enlarging and light drawing are some of the techniques he used to achieve the fresh form he sought in his still lifes, landscapes, nudes and portraits. As a filmmaker, he directed two films on his friend Alexander Calder: “Sculptures and Constructions” in 1944 and “Works of Calder” (with music by John Cage) for the Museum of Modern Art in 1950.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Russell Lee (American, 1903–1986)

Jim Norris and wife, homesteaders, Pie Town, New Mexico

1940

Dye transfer print

Committee for Art Acquisitions Fund

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Chao-Chen Yang (Chinese-American, 1910-1969)

Chief Owasippe

1939

Gelatin silver print

The Michael Donald Brown Collection, made possible by the William Alden Campbell and Martha Campbell Art Acquisition Fund and the Asian American Art Initiative Acquisitions Fund

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Chao-Chen Yang came to the United States in 1934 to work at the Chinese Consulate in Chicago. He photographed in his spare time, regularly submitting prints like this one to the national circuit of photography salons. At first glance, this photograph might appear to be a portrait of the man named in the title. In fact, “Owasippe” references a legend about a Potawatomi chief who died waiting for his sons to return from a journey. The story originated in Michigan around the turn of the 20th century; by the 1930s, it had been popularised around the Midwest by the Boy Scouts of America. Yang likely heard the tale in Chicago and photographed a model whose true identity remains unknown. Although the headdress was familiar to settler audiences as a shorthand for “Native,” the one in this photograph references different cultural traditions than those of the Potawatomi. Reality thus became fodder for a fantasy that captured the interest of many viewers in the late 1930s, when Yang’s photograph won multiple awards from camera club juries across the country.

Wall label from the exhibition

Chao-Chen Yang (1910-1969) was a Chinese American photographer based in Seattle, Washington. Born Hangchow, China, Yang received degrees in foreign relations and art education from the University of Hwin-Hwa, Shanghai, and became the director of the Department of Art at the Government Institute in Nanking. Coming to the United States in 1934 to work at the Chinese Consulate in Chicago, he took night courses in art at the Art Institute of Chicago from 1935 to 1939. He was transferred to Seattle as Deputy Consul and founded the Seattle Photographic Society in 1941. He served as director of the Northwest Institute of Photography and concentrated in colour photo printing processes.

Text from the Smithsonian website

Lit dramatically from above, the face of the “chief” emerges stoically from beneath a feathered headdress, the sartorial signifier of “Indianness” lifted by white Americans from the Oceti Sakowin Oyate of the Northern Plains (plate 27 [here above]). Concentrating on some distant point beyond the frame, he squints as if staring into the sun, but the nondescript background suggests that the photograph was likely made in a studio setting. All the better to decontextualize and generalize its subject, because the aim is not to reproduce the specificity of an Indigenous person, but to practice the visual shorthand popularized decades earlier by the photographer Edward S. Curtis and his North American Indian portfolios (fig. 2).1 The stereotyping function of this picture is reinforced by its title: “Chief Owasippe” is not Oceti Sakowin Oyate, but an invented leader of the Potawatomi, whose name continues to adorn the oldest Boy Scout camp in the United States, founded in 1911 in Michigan by a group of businessmen from Chicago.

Yet this reductive representation of the “vanishing Indian” – whose authenticity and natural purity came from his exteriority to the temporal and societal boundaries of modernity – was produced by a recent arrival to the United States with no personal connection to the politics of Indigenous assimilation, domination, and expropriation that underpinned this representational type. Chao-Chen Yang, employee at the Chinese consulate in Chicago, made this picture while enrolled in night classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. The photograph is his attempt to speak a foreign language: not English per se but the dialect of American identity, which is so filled with fantasy and contradiction that it feels right, with the theme of this exhibition in mind, to call it a language of dreams. What fluencies must the photographer possess to move freely within another person’s dream?

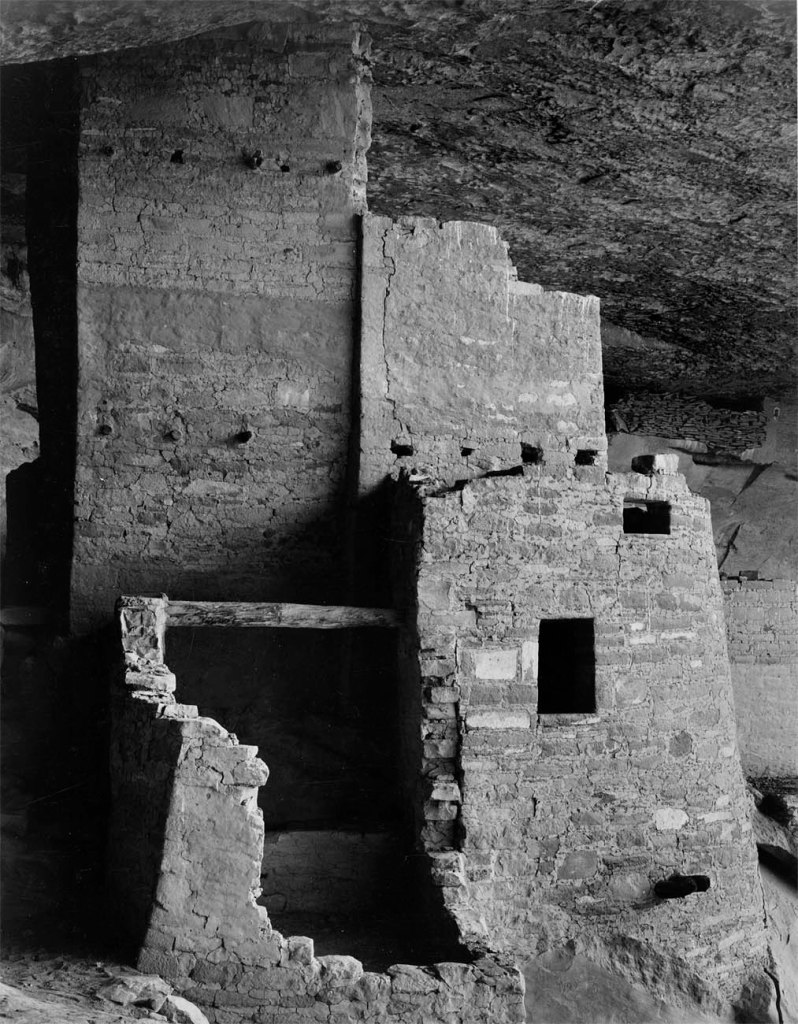

By the time Yang took this photograph, American artists’ fetishistic valorization of Indigenous culture had turned away from the Plains tribes from which the chief’s feather headdress originates and toward the southwestern tribes in New Mexico. In the 1920s, writers and artists including D. H. Lawrence, Mabel Dodge Luhan, John Sloan, and Marsden Hartley projected an “authenticity” onto Pueblo visual culture, which justified their appropriation of its subject matter and form to create a native modernist aesthetic.2 Many photographers did the same, including Ansel Adams and Wright Morris (plates 47 and 48). For its time, Yang’s photograph spoke a dated form of Indigenous appropriation, but the numerous exhibition stamps on the version of the print held by his estate reveal that this image was widely received by photography clubs across America – New York, Denver, all the way to Seattle, where Yang would become deputy consul in 1941.

Vexingly, the racist exoticization and flattening of Indigenous identity performed by the photograph also demonstrate its creator’s fluency with the visual language of artistic-minded amateur photographers in America…

Yechen Zhao. “Photographic Fluency (Its Pleasures and Pains): Kyo Koike and Chao-Chen Yang,” in Josie R. Johnson. Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2023, p. 55.

Everyday Splendors

Shinsaku Izumi (Japanese-American, 1880-1941)

The Shadow

c. 1931

Gelatin silver print

Dennis and Annie Reed Collection

In The Shadow (c. 1931, above), Izumi plays with the late-afternoon light, picturing a man riding a bike. In the upper-right-hand corner of the image, we see part of the front wheel; the entire rear wheel; the bicycle seat; and the cyclist’s feet, perfectly balanced and planted on pedals, riding past our line of vision. The rest of the image shows the bike traveling past a rectangular manhole cover, on the left side; and, on the right, the front wheel appears prominently as it casts a long shadow, with the individual spokes disappearing with each rotation. Against the brushed surface of the street, hard and soft patterns of gray emerge diagonally across the image…

The Shadow [is] a study of motion, light, and shadow, and, on another level, a metaphysical commentary on “the fugitive, fleeting beauty of present-day life.”

Susette Min. “Speculative Frameworks: Approaching the Interwar Years Work of Shinsaku Izumi and Nakaji Yasuim,” in Trans-Asia Photography Volume 5, Issue 1: Photography and Diaspora, Guest Edited by Anthony W. Lee, Fall 2014

Marion Post Wolcott (American, 1910-1990)

One of the Wilkins family making biscuits for dinner on cornshucking day at Mrs. Fred Wilkins’ home near Tallyho, Granville County. North Carolina

1939

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Judith Hochberg and Michael Mattis

Cantor Arts Center Collection

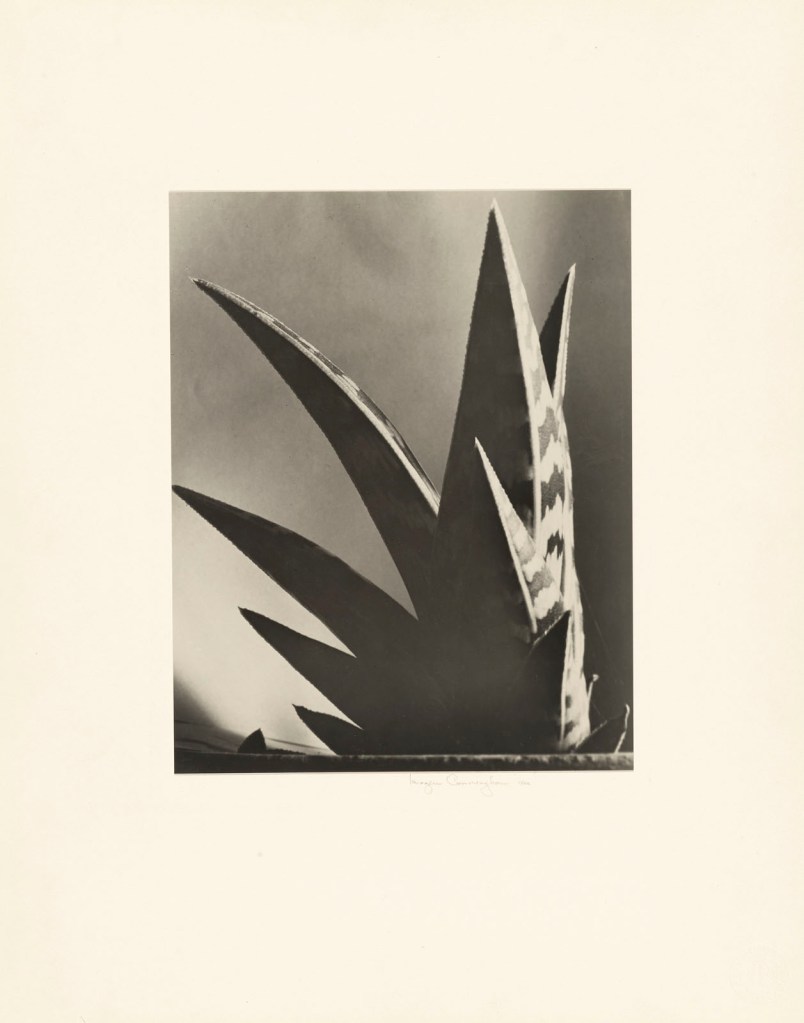

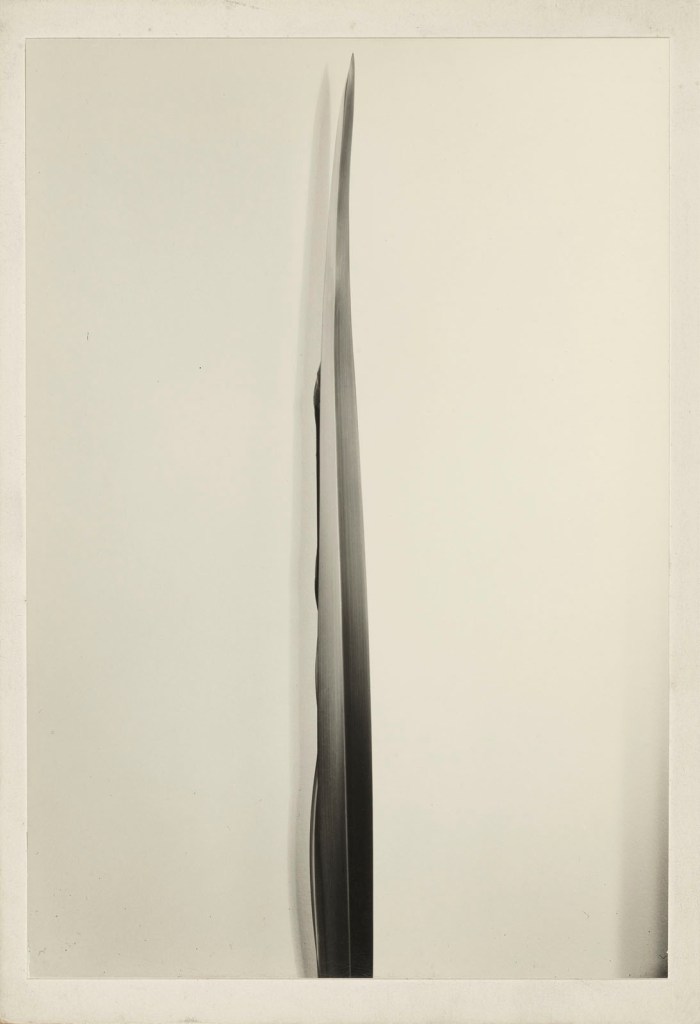

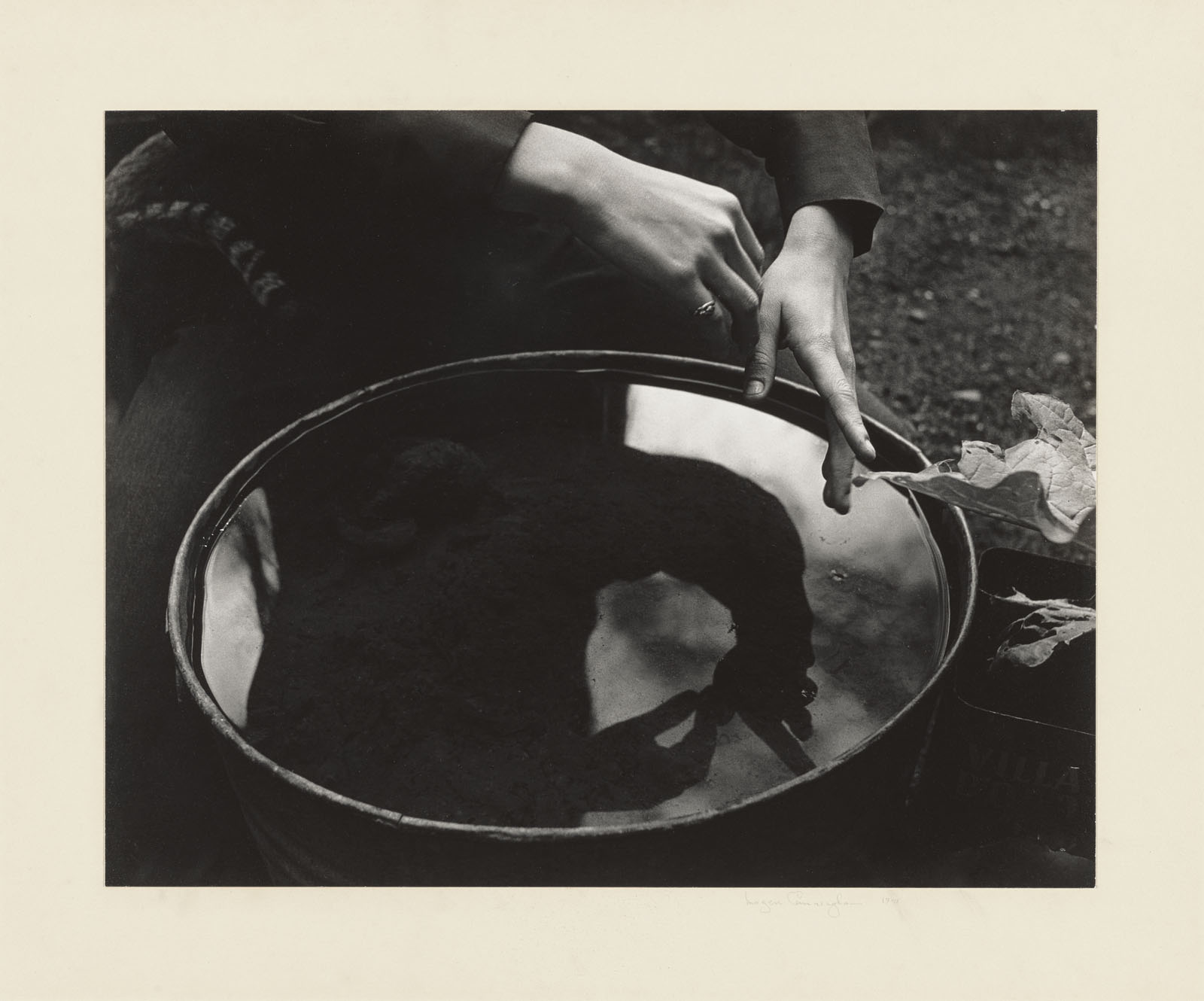

Sonya Noskowiak (American, 1900-1975)

Washing, San Francisco, California

1937

Gelatin silver print

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The United States General Services Administration, formerly Federal Works Agency, Works Projects Administration (WPA), allocation to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Sonya Noskowiak (25 November 1900 – 28 April 1975) was a 20th-century German-American photographer and member of the San Francisco photography collective Group f/64 that included Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. She is considered an important figure in one of the great photographic movements of the twentieth century. Throughout her career, Noskowiak photographed landscapes, still lifes, and portraits. Her most well-known, though unacknowledged, portraits are of the author John Steinbeck. In 1936, Noskowiak was awarded a prize at the annual exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists. She was also represented in the San Francisco Museum of Art’s “Scenes from San Francisco” exhibit in 1939. Ten years before her death, Noskowiak’s work was included in a WPA exhibition at the Oakland Museum in Oakland, California.

Photography

Noskowiak primarily focused on landscapes and portraits between the 1930s and 1940s. Noskowiak embraced straight photography and used it as a tool to give newer meaning to her photographs. She emphasized the forms, patterns, and textures of her subject, to enrich the documentation of it.

Her earliest works reflect the work of photographers of her period and their thoughts on Pictorialism. In her earliest works, such as City Rooftops, Mountains in Distance (the 1930s), there is a graphic quality to how she abstracted the piece. There is the dark, strong industrial structure that contrasts with the light sky. There are almost no logs seen on the buildings, as if they are they are blurred beyond readability. This is an example of the ‘New Objectivity’ movement, which focused on a harder, documentary approach to photography.

Noskowiak often composed her photographs to intersect her subjects, which gave a more dynamic feel to her photographs. Examples of these are provided by her works Kelp (1930) and Calla Lily (1932). The composition crops the boundaries of the kelp plant and flower and draws the viewer’s eye to the texture of the plants. The kelp is so abstracted that if not for the title it would be unrecognisable. In Calla Lily, her use of chiaroscuro gives a luminous, almost floating feeling to the photograph.

Her photograph Agave (1933) is an intimate viewing of the cactus plant – another example of a composition separating the object from what is made visible shown and emphasising the plant’s beautiful pattern.

Noskowiak utilised the same technique of straight photography in her pictorial portraits and commercial works. The same intimacy shown in Agave can be seen in portrait works such as John Steinbeck (1935) and Barbara (1941). In both, she creates an intimate atmosphere, in which the viewer feels as though they are there interacting with the subjects. Even in her more commercial works, Noskowiak’s style and technique still remained important. In her untitled 1930s photograph, you have a model with a broad-brimmed hat that conceals her face. The composition of the piece relieves viewers from thinking about the photograph as an advertisement. The cropping and position of the model offers closeness, and viewers get the feeling of being in the moment with the model more than simply responding to the photo as an advertisement.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Cement Worker’s Glove

1936, printed 1952-1955 by Brett Weston

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

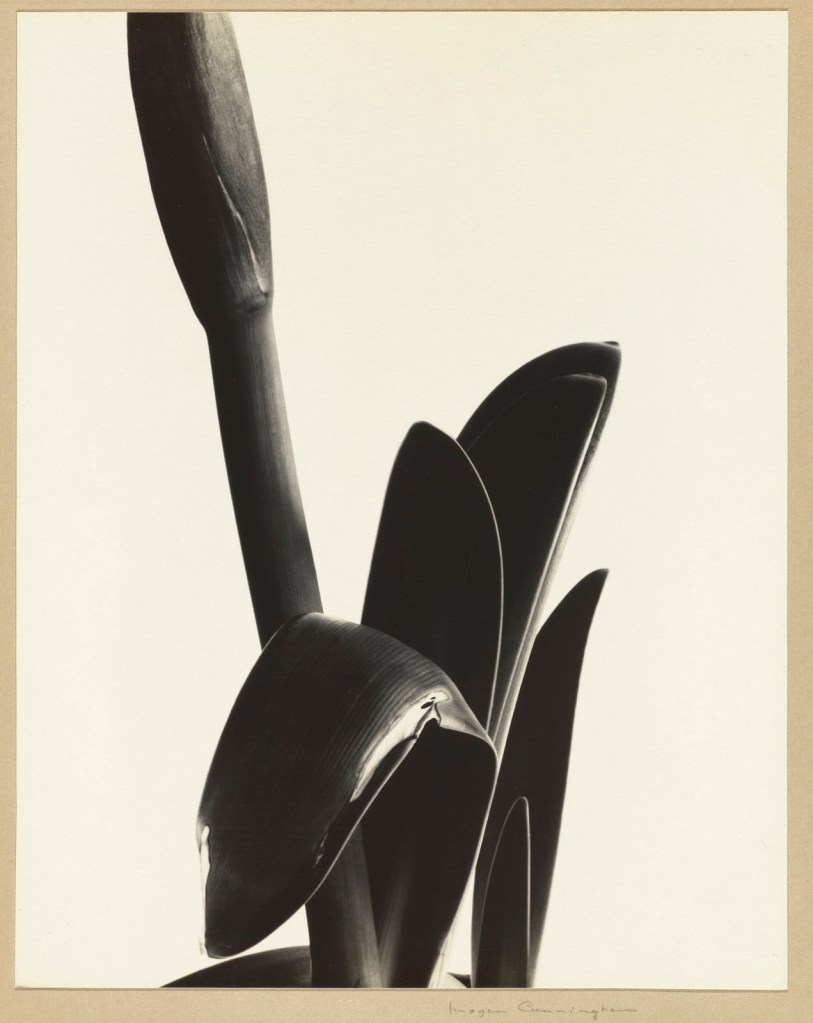

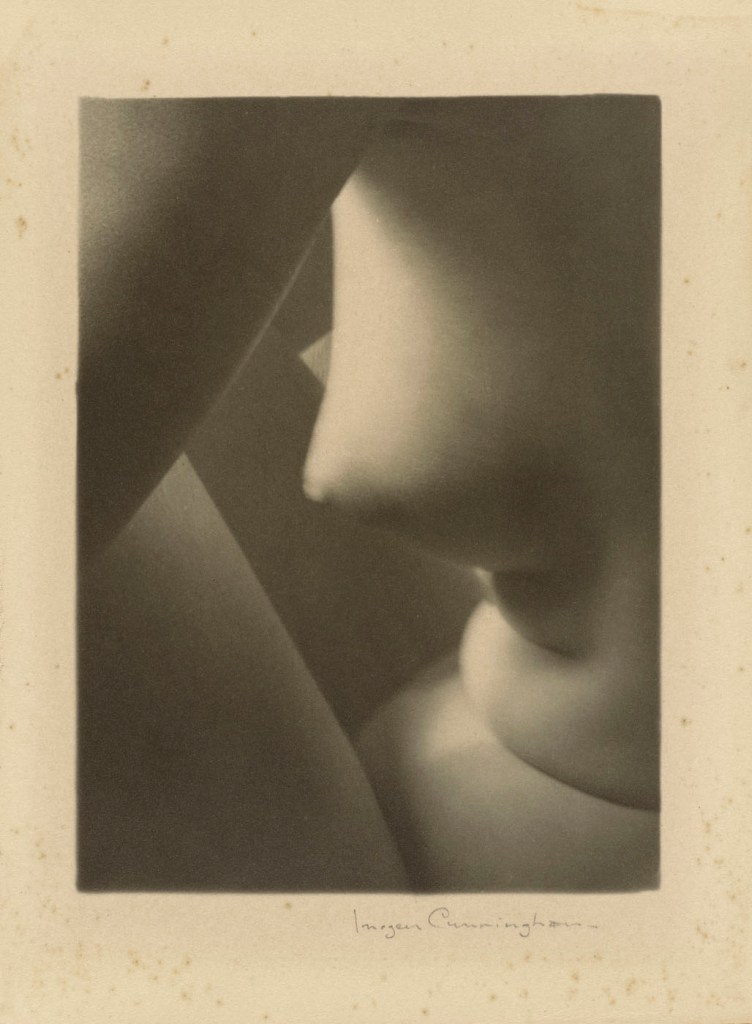

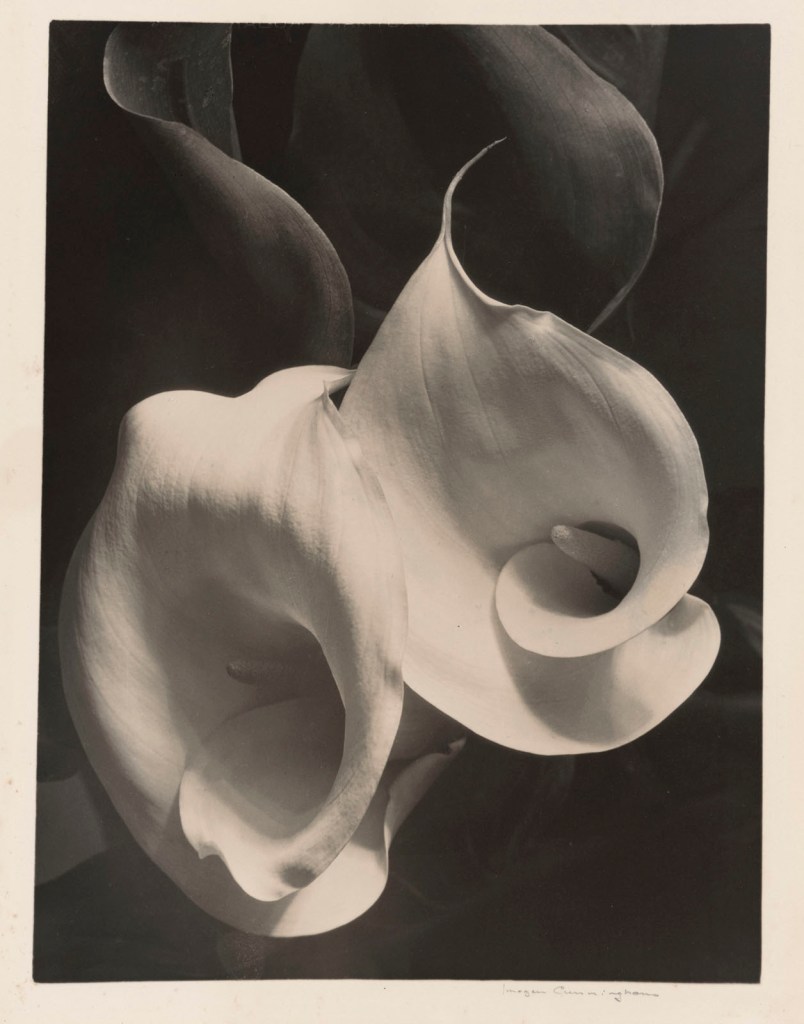

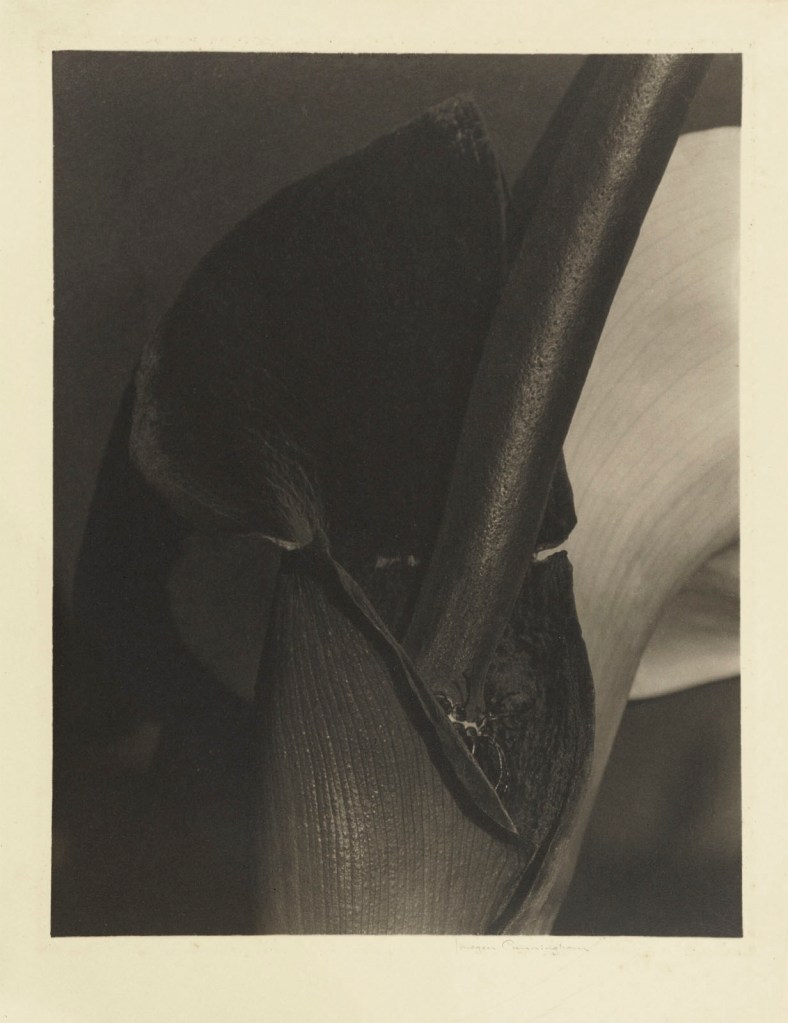

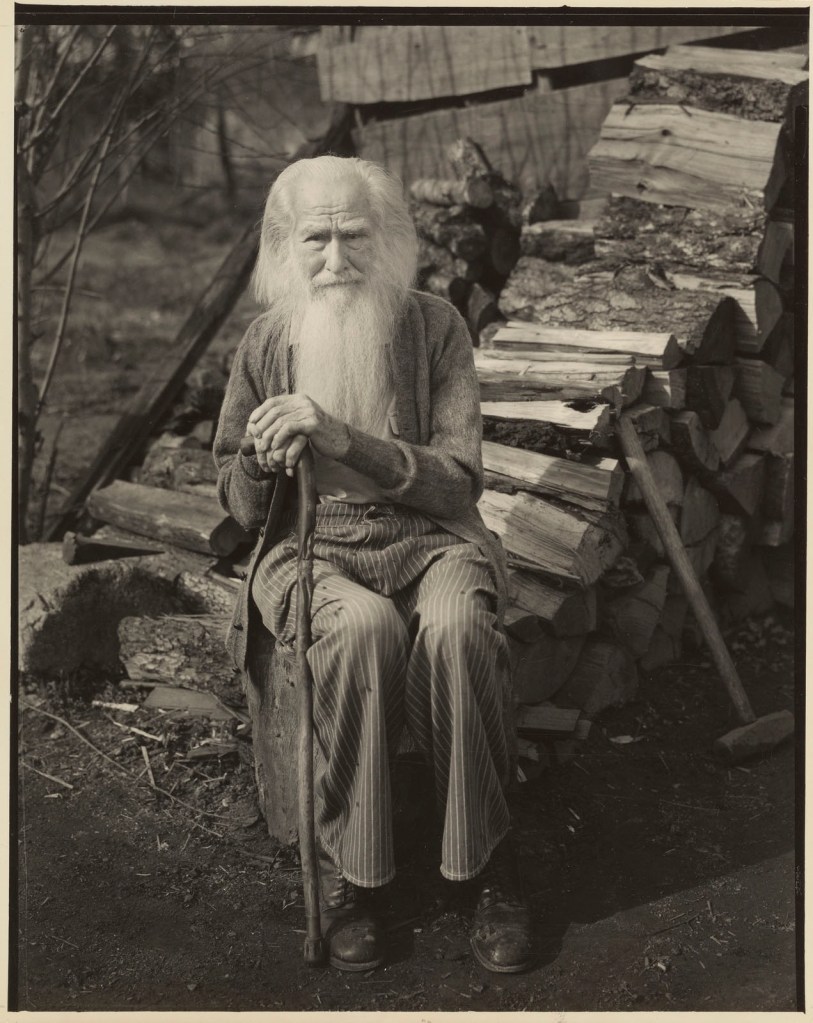

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976)

Junk

1934

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Florence Alston Swift

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Henry Swift Collection

Seema Weatherwax (Jewish-American, 1905-2006)

Yosemite

1940

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries

Seema Aissen Weatherwax was a photographer and social activist who was part of the Film and Photo League, worked with Ansel Adams in Yosemite, and shot Woody Guthrie and migrant workers at a California FSA camp. …

Emigrating from Tsarist Russia with her parents in 1913 to escape persecution and the conscription act, Seema Aissen graduated from high school and began studying science courses in Leeds, England. A few years after her father’s death, her mother took the three daughters to Boston to join relatives, and Seema became involved in photography. She moved to Southern California in 1929, lived in Tahiti for a year, and upon returning to Los Angeles joined the Film and Photo League in 1934. Ansel Adams asked her to run his darkroom in Yosemite in 1938. The following year she assisted Adams with the first Camera Workshop in Yosemite. In 1941 Seema met the writer Jack Weatherwax, and together with folk singer Woody Guthrie visited the Shafter Farm Security Administration Camp, managed by noted civil rights advocate Fred Ross. At Shafter she photographed Dust Bowl refugees and their surroundings. The Weatherwaxes moved to Santa Cruz, California in 1984. Following the death of her husband, Seema continued her activism, including working with the NAACP and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and at the age of 95 organized the first exhibition of her work. She passed away in 2006, two months shy of her 101st birthday.

Text from the Online Archive of California website

Prints made by Seema at Yosemite reveal a photographer whose confidence in her technical abilities allows her to pursue photography in daunting weather conditions7 and to render transcendent beauty through everyday forms, both natural and man-made. Her work from this period focuses not only on postcard-ready vistas but also on the physical structures that locate and organise human experiences within these natural surroundings: like a slush-covered road impressed by tire tracks, or a fawn viewed through a gridded windowpane. 8 In one winter scene from 1940, titled simply Yosemite, tall wooden utility poles with triple cross-arms anchor a dozen snow-coated cables (plate 38 [above]). Set amidst dark tree trunks laced with white boughs, these power lines are resplendent in the snow. They stream down the vertical axis of the scene, indelible reminders of a Yosemite modernised for tourism – reminders that Adams typically left out of his artistic work. Seema’s prints from the 1940s are variously signed “Seema,” “Seema Aissen,” and later “Seema Weatherwax,” reflecting the surname she adopts upon marrying writer and political activist Jack Weatherwax in 1942.

Anna Lee. “Seema (Sophie) Aissen Weatherwax: Photographer,” in Josie R. Johnson. Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2023, p. 72.

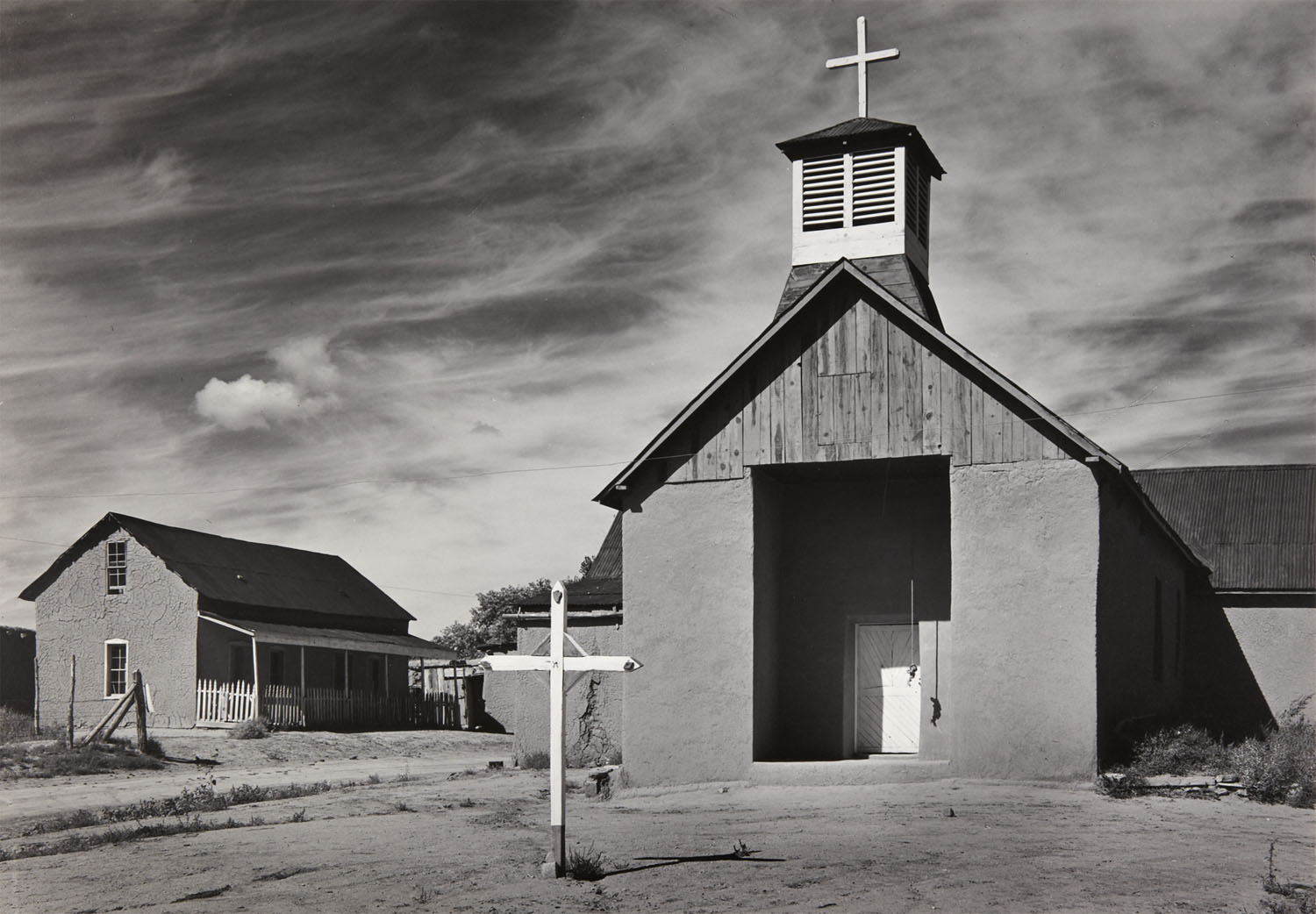

Living Relics

Wright Morris (American, 1910-1998)

Meeting House, Southbury, Connecticut

1940

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Wright Morris developed a personal practice of pairing his photographs with texts, publishing the first of many of these combination projects in 1940. The page-long text paired with a variation of this photograph does not describe an observed scene but rather a scene imagined by the narrator, who sits “like a man caught in a spell” seeing “what nobody’d seen before.” By presenting this text with his photograph of an unidentified, weather-worn wooden building, Morris vaguely evokes a moment from the past, but leaves its meaning open to interpretation. As with memories and daydreams, the viewer’s impressions are subjective and imprecise, if not total figments of the imagination.

Wall label from the exhibition

Wright Morris (1910-1998) was a renowned writer and affective photographer. Pairing photographs with his own writing, Morris pioneered a new tradition of “photo-texts” in the 1940s that proved highly influential to future photographers. Devoid of figures, his photographs depict everyday objects and atmosphere. Morris’s poetic images exist in a fictional narrative, but reference documentary style.

Born in Nebraska, Morris attended Pomona College in Claremont, California. After graduation he traveled throughout Europe, purchasing his first camera in Vienna. Morris returned to California in 1934 determined to become a writer, but also continued to photograph. In 1935, he bought a Rolleiflex camera and began photographing extensively. Morris first exhibited his photo-texts in 1940, at the New School for Social Research in New York. This same year the Museum of Modern Art purchased prints for their collection and New Directions published images that would become his first book.

In 1942, Morris received the first of his three Guggenheim Fellowships, funding the completion of The Inhabitants. Published by Scribners, The Inhabitants (1946) documented domestic scenes of the South, Midwest, and Southwest and although visually influential enjoyed little financial success. His second photo-text book, The Home Place (1948) was a visual novel, with short fictional prose accompanying each photograph. Although groundbreaking, it remained unmarketable and after its publication Morris invested in his more successful career as a writer. In 1956, Morris won the National Book Award for his tenth book, the unillustrated A Field of Vision. Morris continued to write and publish while teaching English and creative writing from 1962-1974 at San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California. Morris’s acclaimed novel, Plains Song won American Book Award for Fiction 1981.

The Museum of Modern Art proved supportive of Morris throughout his career, both exhibiting and purchasing his work. MoMA curator John Szarkowski prompted a reconsideration of Wright Morris with the publication of God’s Country and My People (1968), widely considered Morris’s most successful photo-text book. Morris’s exhibition career burgeoned in his later years with many shows including Wright Morris: Origin of a Species, a 1992 retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and following his death, Distinctly American: The Photography of Wright Morris at Stanford’s Cantor Center of Art in 2002.

Anonymous. “Wright Morris,” on the Center for Creative Photography website Nd [Online] Cited 04/07/2023

Wright Morris (American, 1910-1998)

House in Winter, near Lincoln, Nebraska

1941, printed 1979-1981

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Wedding Cake House, Kennebunkport, Maine

1941, printed 1952-1955 by Brett Weston

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

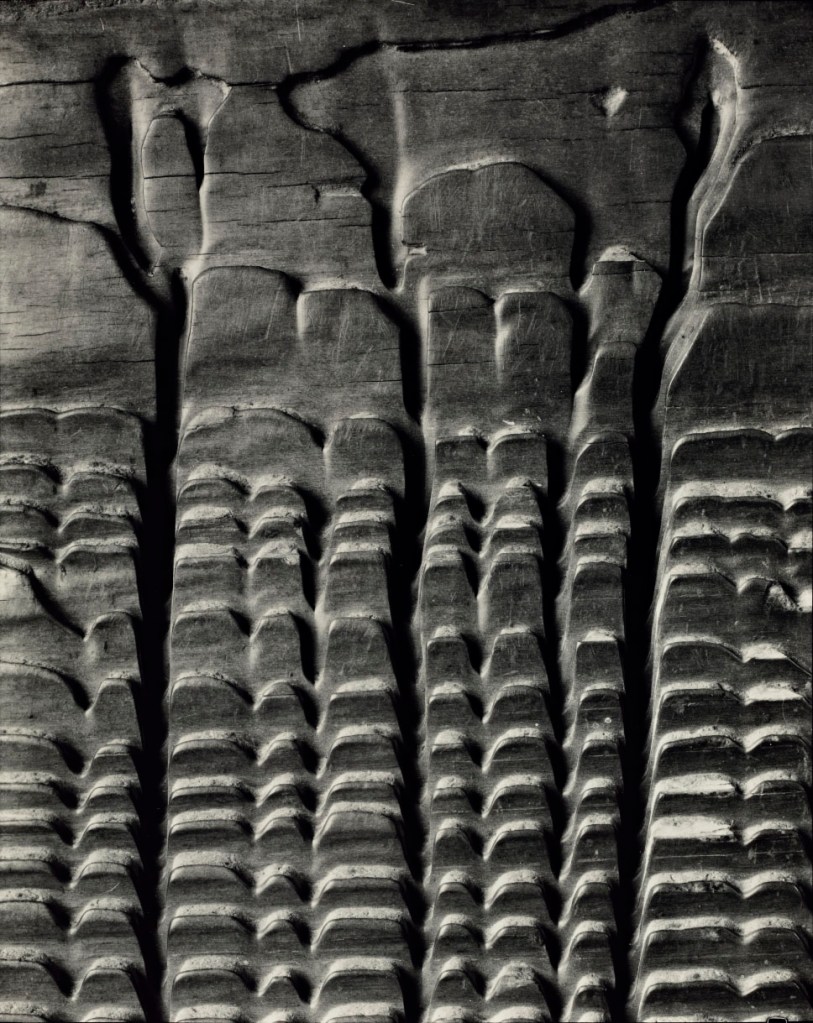

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Eroded Plank from Barley Sifter

1931, printed 1952-1955 by Brett Weston

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

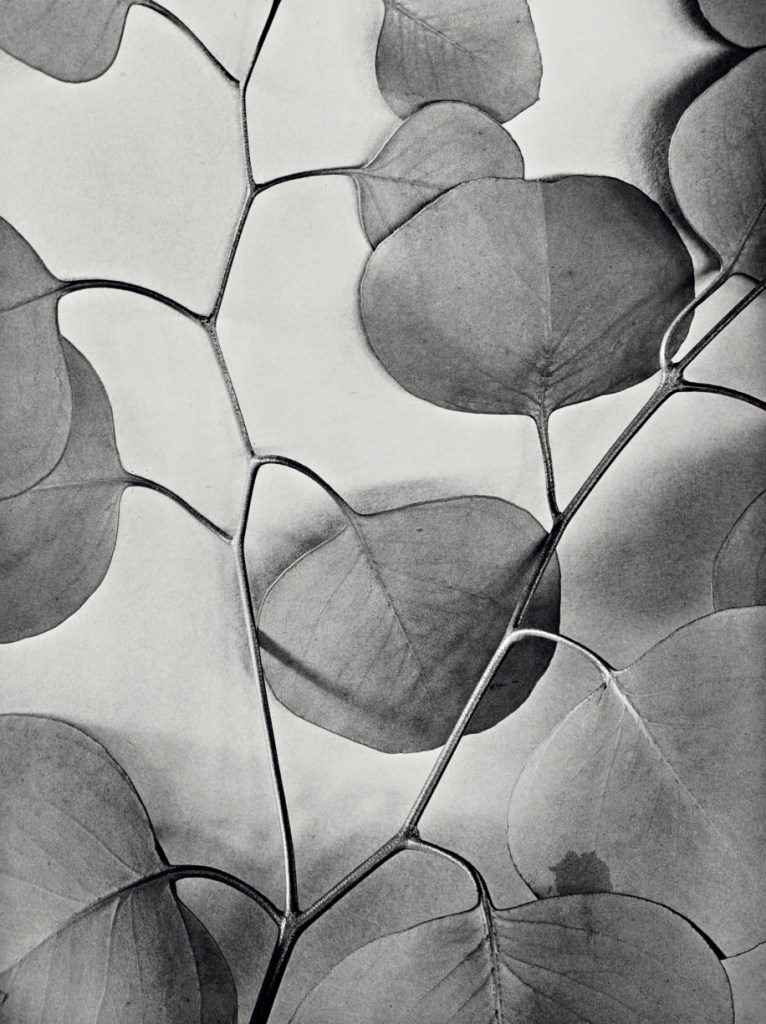

Alma Lavenson (American, 1897-1989)

Eucalyptus Leaves

1933

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

The next year Lavenson made her own picture specimen, titled Eucalyptus Leaves, a forking branch against white ground (plate 49 [above]). The leaves are rounded, almost gingko-like, the stems slender and bending, a young plant or newer shoot, likely blue or silver dollar gum. It is hard to make sense of the light, which comes from the left, above, and the right – which is to say that there is an unnatural quality to the photograph. This looks like a studio picture, though Lavenson rarely worked indoors. But there are ways the photograph is in conversation with others made during this period, after she met Weston in 1930. It is a graceful picture, attentive to form and surface. Almost a decade later Lavenson would write, “In all my work – whether shacks or flowers or landscapes – I aim for perfection of texture and fineness of detail.”2 Up close the silver gelatin print has a lithographic quality, in its etched shadows and shining branch, the velvet opacity of the leaves.

Footnote 2. Alma R. Lavenson. “Virginia City: Photographing a ‘Ghost Town,'” in U.S. Camera Magazine 10 (June-July 1940), 66, quoted in Audrey Goodman. A Planetary Lens: The Photo-Poetics of Western Women’s Writing. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2021, p. 75.

Rachel Heise Bolten. “Eucalyptus Leaves,” in Josie R. Johnson. Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2023, p. 87.

The World of Tomorrow

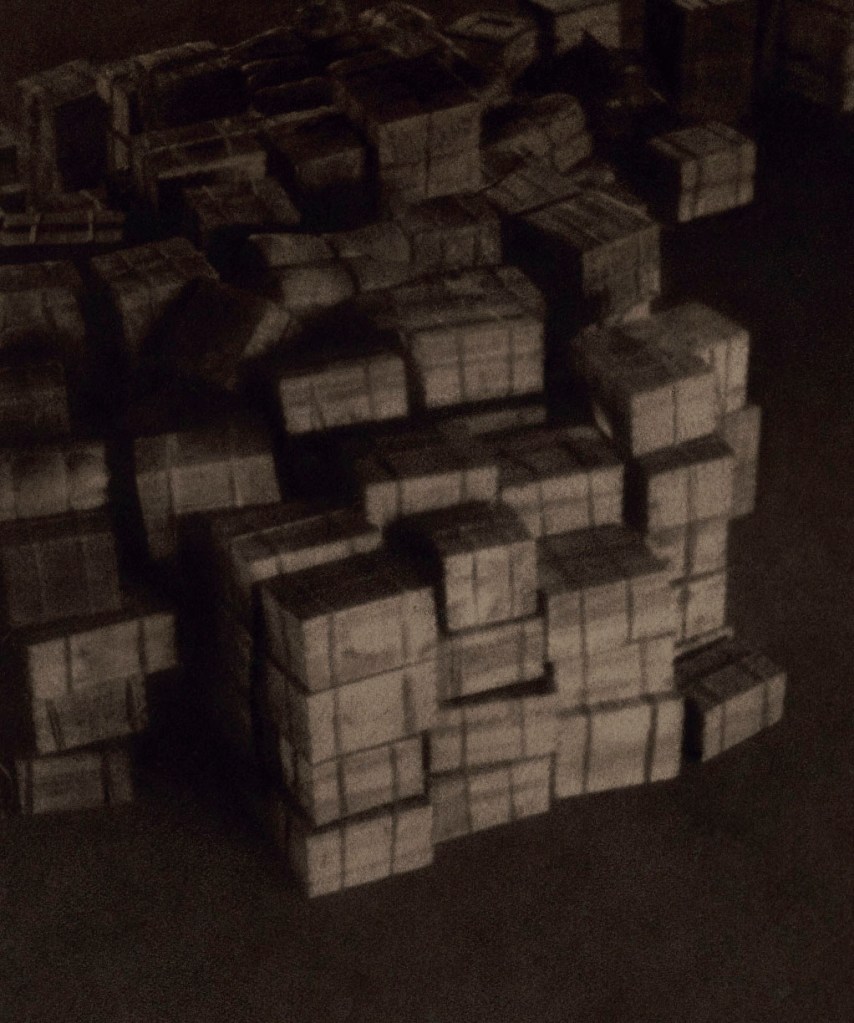

Akira Furukawa (American born Japan, 1890-1968)

Cargo

1929

Bromoil

Dennis and Annie Reed Collection

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Egg Slicer

1930, printed 1952-1955 by Brett Weston

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Ruth Bernhard (American born Germany, 1905-2006)

Kitchen Music

1930-1933

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Hiromu Kira (American, 1898-1991)

The Thinker

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Dennis and Annie Reed Collection

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

Drilling Rig, The Texas Co.

1937

Gelatin silver print

Elizabeth K. Raymond Fund

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Lou Stoumen (American, 1917-1991)

Times Square in the Rain

1940

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Lou Stoumen began photographing Times Square when he first moved to New York City at age 21. Decades later, he still recalled the day he made this photograph, when he rode an elevator to the top of the Times Building, then waited to snap the shutter until the rain “turned the great X of Broadway and Seventh Avenue into silvery rivers.” Stoumen continued photographing this famed stretch of the city for nearly half a century, but he remembered the years around 1940 as special: “Those days Manhattan was the center of the world, and Times Square was its heart.”

Wall label from the exhibition

It was raining in New York. Streets slick as oil, people hurrying past the trams and buses in Times Square with their umbrellas up. September 1940: the penultimate year of peace for America. An ocean away, bombs were falling on London, nightly. But here, for now, people could still think of it as a European war.

Some of the crowds in Lou Stoumen’s photograph Times Square (plate 59 [above]) might have come to catch Gone with the Wind, Wallace Beery’s new western Wyoming, or Busby Berkeley’s latest musical spectacular Strike Up the Band, starring Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney. Times Square: Here are the cinemas and the burning neon lights and the billboards for cigarettes and automobiles and cold, fizzy drinks. All the things you can buy and see during an autumn in New York.

Lou Stoumen was 23 when he made the photograph: The elevator at 1475 Broadway took him up the first 19 stories and then he took the stairs up the final six flights, to the top, and walked out onto the roof ledge.1 From there he pointed his camera out at 46th Street and Broadway capturing the TIMES sign from behind. The building had once been the home of the New York Times, but the newspaper had departed in 1913 and now the sign stood as an announcement of a location, a cry too, an exclamation of the times. …

Margaret Bourke-White photographed Drilling Rig, The Texas Co. (1937) (plate 56) within the oil well’s tower, looking up at the vertiginous pipes that pumped petroleum from beneath the ground. The cutting shadows cast by the latticework of the rig patterns the image with a rigorous geometry, all forms reduced to a series of rectangles and triangles. Humanity has disappeared from view, to be replaced by science and engineering, unchallengeable, mathematically correct.

Bourke-White had begun working for the newly established Life magazine a year earlier, already one of America’s most prominent news photographers.5 Yet she had been fascinated with shooting machinery since the late 1920s, claiming that “the beauty of industry lies in its truth and simplicity; every line is essential therefore beautiful.”6 The drilling rig is undoubtedly elegant; shorn of context, it becomes impossible to establish its scale or relationship to its environment. It stands as an autonomous creation, a pure distillation of form as function. Irresistibly, its towering pipes and metal superstructure, disappearing into the distance at the top of the photograph, recall the skyscrapers of Stoumen’s New York. Their symbiosis is more than coincidence: It is the drilling rig that enables the tower block. This is the stuff that the World of Tomorrow is built upon.

1/ William A. Ewing. Ordinary Miracles: The Photography of Lou Stoumen. Los Angeles: Hand Press, 1981, p. 22.

5/ Stephen Bennett Phillips. Margaret Bourke-White: The Photography of Design, 1927-1936. Washington, DC: Phillips Collection, in association with Rizzoli, New York, 2002, p. 83.

6/ Margaret Bourke-White in 1930, quoted in Theodore M. Brown. Margaret Bourke-White: Photojournalist. Ithaca, NY: Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art, Cornell University, 1972, p. 31.

Altair Brandon-Salmon. “Sign of the Times,” in Josie R. Johnson. Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2023, pp. 101-102.

John Gutmann (American born Germany, 1905-1998)

“Switch to Dodge,” An American Altar, Detroit

1936

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Street Theater

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Corrugated Tin Façade

1936

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Dr. J. Patrick and Patricia A. Kennedy

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

Warehouse, Water and Dock Streets

1936

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Daniel Mattis

Cantor Arts Center Collection

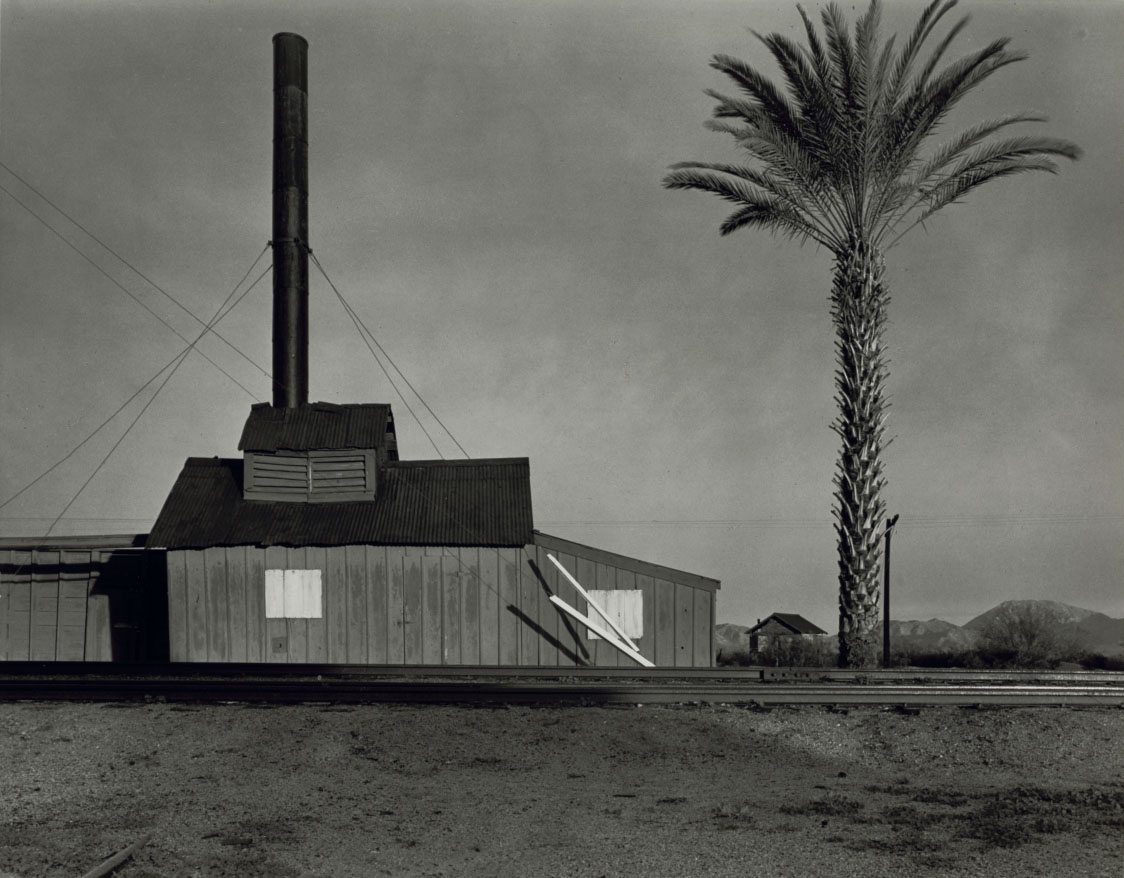

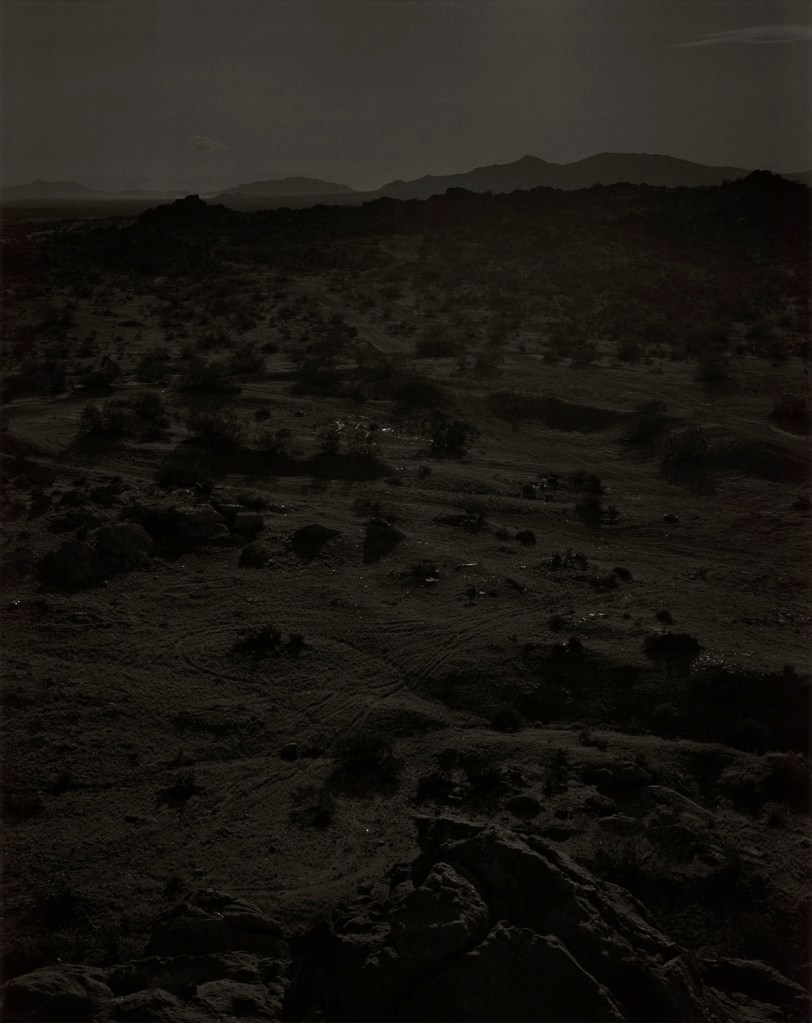

Wright Morris (American, 1910-1998)

Powerhouse and Palm Tree, near Lordsburg, New Mexico

1940, printed 1979-1981

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Marion Post Wolcott (American, 1910-1990)

Center of town. Woodstock, Vermont. “Snowy night”

1940

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Michael and Sheila Wolcott

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Marion Post Wolcott made this photograph halfway through her three-year appointment as a photographer for the Farm Security Administration. Though most of her work (and that of the FSA overall) was understood at the time as “documentary” or factual in nature, this is one of several photographs by Post that tended to stir the imagination. For instance, Sherwood Anderson reproduced this photograph in his 1940 book on rural America, Home Town, to illustrate his metaphor for New England winters as times of peaceful slumber.

Wall label from the exhibition

Aaron Siskind (American, 1903-1991)

Untitled from St. Joseph’s House

c. 1938

Gelatin silver print

Vincent Bressi Fund

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Robert Disraeli (American born Germany, 1905-1988)

Sunday – After Church

1933

Gelatin silver print

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Committee for Art Acquisitions Fund

Wright Morris (American, 1910-1998)

Untitled

1940

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009)

New York

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Helen Levitt avoided the descriptive or symbolic titles favoured by the previous generation of photographers, preferring instead to leave her photographs untethered to specific people or locations within New York. The viewer is thus given free rein to make associations or compose narratives from the streetscapes in each photograph, just as the shoe shiner in this image may have conjured his own daydream from the action unfolding on the street.

Wall label from the exhibition

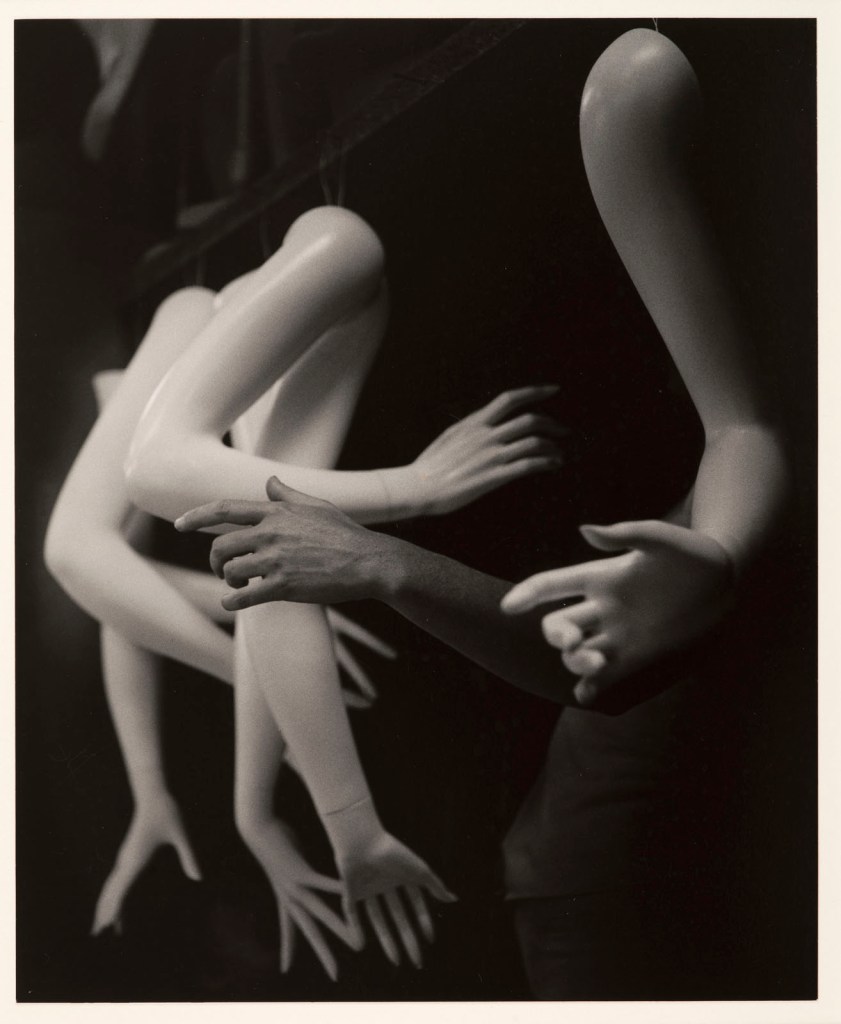

Surreal Encounters

John Gutmann (American born Germany, 1905-1998)

Monster on Broadway, New York City

1936

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

John Vachon (American, 1914–1975)

Girl on Lobster, Washington, D.C.

1938

Gelatin silver print

Gift of R. Joseph and Elaine R. Monsen

Cantor Arts Center Collection

By the early 1930s, discussions about Surrealism had spread from the art world into the mainstream, even if few Americans subscribed to, or even understood, its main tenets. Not long after, Americans began to use the words “surreal” and “surrealistic” to describe anything bizarre or dreamlike. Each of these three photographs could have fit this unofficial classification; by locating the extraordinary among the ordinary – a monster in the city, a woman riding a lobster, and another woman enacting the text on the magazine in her hands – each image is thoroughly uncanny.

Wall label from the exhibition

John Gutmann (American born Germany, 1905-1998)

Monument to the Chicken Center of the World, Petaluma, California

1936

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

After photographing the town of Petaluma, north of San Francisco, John Gutmann sent dozens of prints to his agent in New York. He explained: “This little town of 9,000 inhabitants and its surrounding ranches is today one of the greatest, if not the greatest poultry center in the world. … Thousands and thousands of little chicken houses, covering the country, the low built hatcheries, the many signs and symbols, trucks fully loaded with poultry or eggs give a very unique character to this district.” Gutmann photographed this roadside monument several times, likely noticing the traces of past vandalism visible in this image.

Wall label from the exhibition

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Hot Coffee, Mojave Desert

1937, printed 1977 by Cole Weston

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Although Edward Weston regarded his photography with the utmost seriousness, his writings and accounts from friends reveal a spirited sense of humour. This photograph offers a rare example of this playful side. According to Charis Wilson, Weston’s travel companion at the time, they were struck by the absurdity of the hot coffee advertisement in the middle of the desert; the fact that the location bore the name “Siberia” added a second layer of irony.

Wall label from the exhibition

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905-1985)

The Repulsive Bed

1941

Gelatin silver print

Gift from the Alinder Collection

Cantor Arts Center Collection

In the summer of 1941, Edward Weston visited Louisiana with Clarence John Laughlin as his guide. Before driving to the same building that Walker Evans had photographed six years earlier, they visited another antebellum plantation house where Laughlin photographed a friend among the ruins. Weston shared Laughlin’s fascination with the ornate architecture, laden with history as it slowly deteriorated back into swampy earth. Yet Laughlin understood these forces as an embodiment of Surrealism. For him, New Orleans was a place “unparalleled in its violence of decay” but also where “the human spirit reached a singular flowering” in the face of this destruction.

Wall label from the exhibition

Dubbed “The Father of American Surrealism,” Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905-1985) was the most important Southern photographer of his time and a singular figure within the burgeoning American school of photography. Known primarily for his atmospheric depictions of decaying antebellum architecture that proliferated his hometown of New Orleans, Laughlin approached photography with a romantic, experimental eye that diverged heavily from his peers who championed realism and social documentary.

Referring to his own fraught relationships with women, Laughlin described this ethereal photograph of a woman lounging atop a collapsed, tattered bed in a decaying house as an “Image of those who endure marriage, without love, because of convention. [The] marriage bed becomes repulsive, and part of it turns into a monster head.” The veil across the woman’s face gives her a haunting look, as if she is fading away along with the house around her. The cracks in the wall reinforce the idea of a fractured, failing marriage, while the shadows envelop her in darkness.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Breakfast Room at Belle Grove Plantation, White Chapel, Louisiana

1935, printed 1974

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Dr. J. Patrick and Patricia A. Kennedy

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Walker Evans admired the photography of Eugène Atget (1857-1927), a French photographer whose images of Paris caught the interest of a new generation of photographers shortly before his death. Though neither photographer self-affiliated with Surrealism, Evans recognised that “in some of his work [Atget] places himself in a position to be pounced upon by the most orthodox of surrealists.” Evans occasionally emulated Atget’s style, as in this image of an empty Louisiana plantation house, leading some American critics to describe Evans’s photography in a manner befitting a Surrealist. One 1938 review stated, “In some miraculous way [Evans’s] objects or persons acquire a super-reality, the implications of which echo across the years to startle and haunt, to jolt and to enchant.”

Wall label from the exhibition

Nathan Lerner (American, 1913-1997)

Uncommon Man

1936, printed 1983

From Nathan Lerner – Fifteen Photographs: 1935-1978

Gelatin silver print

Gift of the Mattis Family

Cantor Arts Center Collection

Frederick Sommer (American, 1905-1999)

Jack Rabbit

1939

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Lisa and John Pritzker

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Sommer’s Jack Rabbit (1939) was one of the first 100 negatives the artist made with his new 8 x 10 inch view camera recommended by his friend Edward Weston.1 Living in the arid climate of Arizona to protect his lungs against the recurrence of tuberculosis, the casualties of the desert – rabbits, horses, coyotes – became some of Sommer’s signature photographic subjects.2 Weston, too, had a penchant for photographing dead things. Weston’s preference was for the corpses of birds, often those of shore birds near his coastal California home.3 Photo historian Robin Kelsey has made an excellent comparison of the two artists’ “rival” treatments of deceased animals, grounded in their diametrically opposed aesthetic concerns. As in Jack Rabbit, Sommer used evenly dispersed light to create a visual field that privileged no one thing above the rest,4 reflecting both an aesthetic and a philosophical orientation concerned with the essential oneness of the world.5 On the other hand, Weston treated his dead birds in the same manner as his nudes or his peppers, expressing what he termed “the universality of basic form.”6 Using light to emphatically trace the contours of the birds’ forms, Weston visually separated them from their backgrounds and transformed them into abstract objects. Aligned with their concerns, the two artists typically chose different moments of death and decay to capture: For Sommer it was desiccated or decaying bodies and for Weston it was stripped bones or newly deceased bodies.

Although Weston’s Dead Man, Colorado Desert (1937) similarly focuses on the clearly defined form of a newly deceased body,7 there are crucial distinctions in its composition. Whereas Weston’s birds are photographed from above, aiding in their abstraction, the dead man is photographed from an angle to the side, which emphasizes both his human features and the bramble-filled space that he occupies (plate 83 [below]). His waist, legs, and one arm continue outside the frame to the top right. This makes Dead Man fundamentally different from Weston’s birds, because the man exists not as an abstract form, but as a body in space, a space that we can imagine Weston and his wife and collaborator Charis Wilson sharing and a space that we can imagine inhabiting ourselves.

Maggie Dethloff. “Violable Edges: Frederick Sommer’s and Edward Weston’s Photographs of Death in the Desert,” in Josie R. Johnson. Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2023, p. 131.

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Dead Vulture, Mojave Desert

1937

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Dead Man, Colorado Desert

1937

Gelatin silver print

The Capital Group Foundation Photography Collection at Stanford University

Cantor Arts Center Collection

While traveling through the Colorado Desert on a photography excursion for his Guggenheim Fellowship, Edward Weston came across the corpse of a recently deceased man. He had apparently become ill and stranded while traversing the harsh landscape. Despite the unexpected, and certainly disturbing, nature of this encounter, Weston seamlessly fit the subject into his photography practice. He made two photographs, one of which Life magazine published alongside a short narrative by Weston titled “Desert Tragedy.” In the text Weston explained: “He must have died that day. But whatever aid he got came too late, hunger and privation had wasted his body and the merciless sun had dried him up. But he was quite beautiful in death.”

Wall label from the exhibition

Cantor Arts Center

328 Lomita Drive at Museum Way

Stanford, CA

Phone: 650-723-4177

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Sunday, 11.00am – 5.00pm

![Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984) '[Dogwood Blossoms, Yosemite National Park]' Negative about 1938; print 1941 Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984) '[Dogwood Blossoms, Yosemite National Park]' Negative about 1938; print 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ansel-adams-dogwood-blossoms-yosemite-national-park.jpg?w=806)

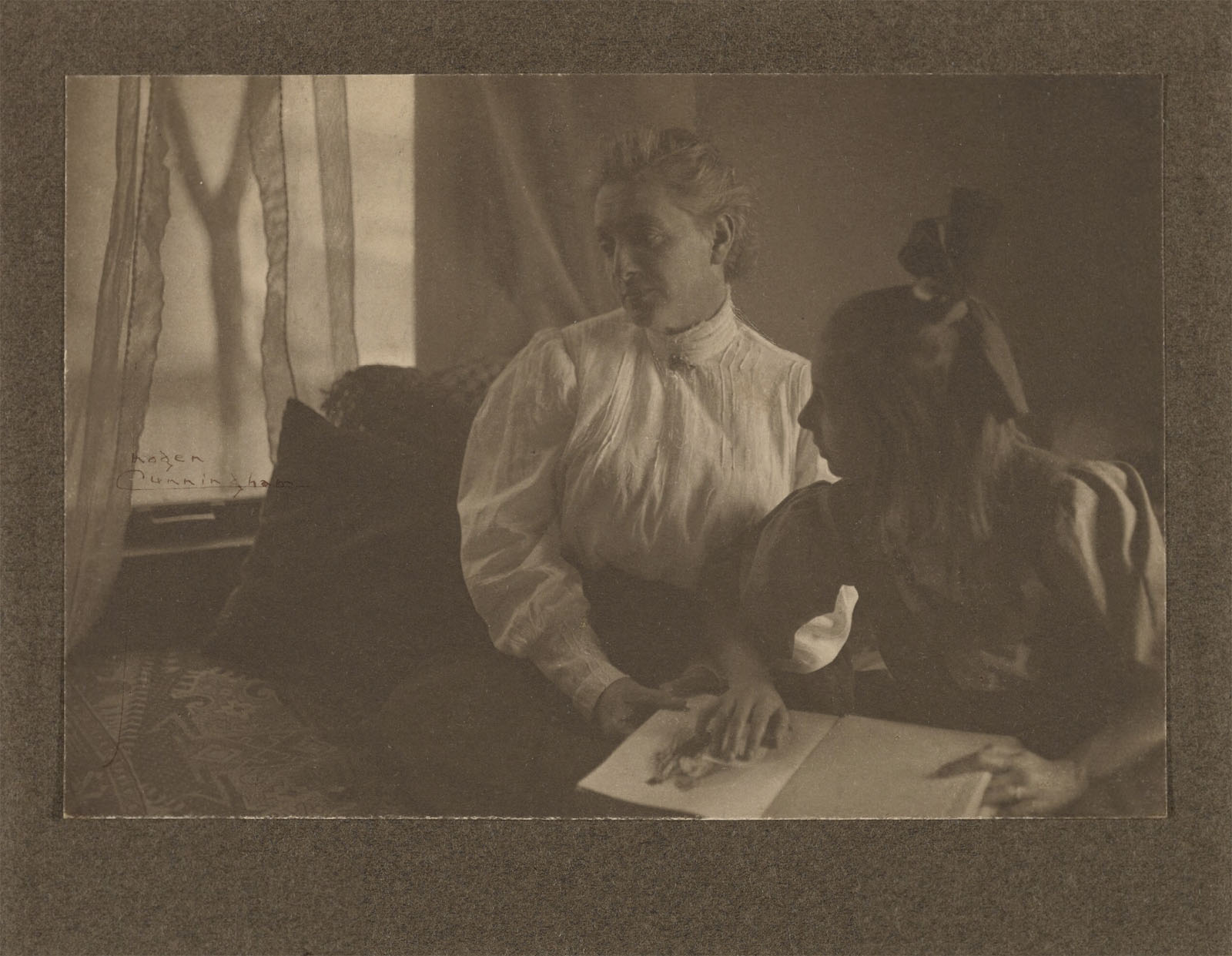

![Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976) '[Sonya Noskowiak]' 1928 Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976) '[Sonya Noskowiak]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/cunningham-sonya-noskowiak.jpg?w=819)

You must be logged in to post a comment.