Exhibition dates: 24th March – 20th August, 2023

WARNING: This posting contains images of graphic violence. Please do not view of you do not wish to see.

Unknown photographer

The child Jacob Bergman standing at the entrance to the office of the “Judenrat” Chairman, Dr. Elchanan Elkes

Ghetto Kovno, Nd

© Yad Vashem Archives

On the door: Vorsitzender des altestenrates (Chairman of the Board of Elders)

Between the foreign and the familiar

This exhibition presents photographs of Jewish ghettos under Nazi control during the Second World War. Mainly featuring photographs of the Łódź ghetto during its period of existence (December 1939 – August 1944) before its destruction, the images were taken by a variety of German and Jewish photographers.

“Tens of thousands of photos were taken in the ghettos, mostly by German photographers but also by several Jewish ones. Many of the German photographers acted in an official capacity for several different organisations of the Nazi state. Others photographed for personal objectives. The few Jewish photographers who managed to work in the ghettos did so in an official capacity for the Jewish ghetto leadership.” (Text from the Museum für Fotografie website)

Jewish photographers such as Mendel Grossman, Arie Ben Menachem and Henryk Ross were officially banned by both Jewish and German authorities from taking personal photographs, but all did so in order to “leave behind a testimony for all generations about the great tragedy unfolding before his eyes.” (Mendel Grossman) If they had of been caught, the photographers and their families would have been killed for taking them.

When the ghetto was liquidated – what a euphemism that is, with over 210,000 human beings starved to death or murdered in the extermination camps leaving only 877 in hiding when the Russians arrived – the photographers hid their precious negatives in the ground in barrels or at the bottom of a well hoping to survive and return after the war to dig up evidence of that most important aspect of life in the ghettos… the value of life and comradeship itself and the atrocities that can be enacted one human being against another. Some photographers hid in the ruins of the ghetto, escaped the city to go into hiding with the resistance, others survived the extermination camps and the death marches, still others succumbed to the genocide.

As the intelligent quotation from Bernd Huppauf observes below, what is important when viewing these photographs is that we pay attention to the details, that unlearning “the seeing of the familiar and replacing a gaze of understanding and empathy with a growing sense of the tensions, and twisted connections, between the foreign and the familiar is a prerequisite for a photo-history beyond a history of mere illustrations.”

As Huppauf says, “Repeated confirmation, through images, of the knowledge that an inhumane ideology will produce inhumane pictures offers little insight.”

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. I have added appropriate bibliographic and historical information to the posting where possible.

Many thankx to the Museum of Photography, Berlin for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“As far as the construction of a pictorial history of the war of extermination is concerned, it is mandatory not to facilitate but rather to render more difficult the reading its photographs. More often than not they are read as parts of a story of encompassing generalisations concerning the immoral and barbaric ideology of the Nazi-system. But such forgone conclusions render the reading of images sterile. As long as the answer to the question as to what they show is known in advance, they will remain silent. Repeated confirmation, through images, of the knowledge that an inhumane ideology will produce inhumane pictures offers little insight. The questions as to what these images show, what they meant for the photographers and what they mean for us are answered neither by varied references to the murderous practices of Nazi-racism nor by reference to the pathological psyche of actors as individuals. Focusing on the concreteness of details and the iconography of the pictures will make ‘visible’ what can be seen in the photos and break the blockade of silence… Unlearning the seeing of the familiar and replacing a gaze of understanding and empathy with a growing sense of the tensions, and twisted connections, between the foreign and the familiar is a prerequisite for a photo-history beyond a history of mere illustrations. The empty ritual of repetitions will only be avoided in as far as the homogenising concept of a photo-history of the Third Reich as a mirror image of Nazi ideology and practices is dissolved and replaced with perspectives capable of reflecting upon differences and specificities in the pictorial self-representation of the time and the social production of attitudes and habits, visually represented in images.”

Bernd Huppauf. Emptying the Gaze: Framing Violence through the Viewfinder, 1997, p. 7.

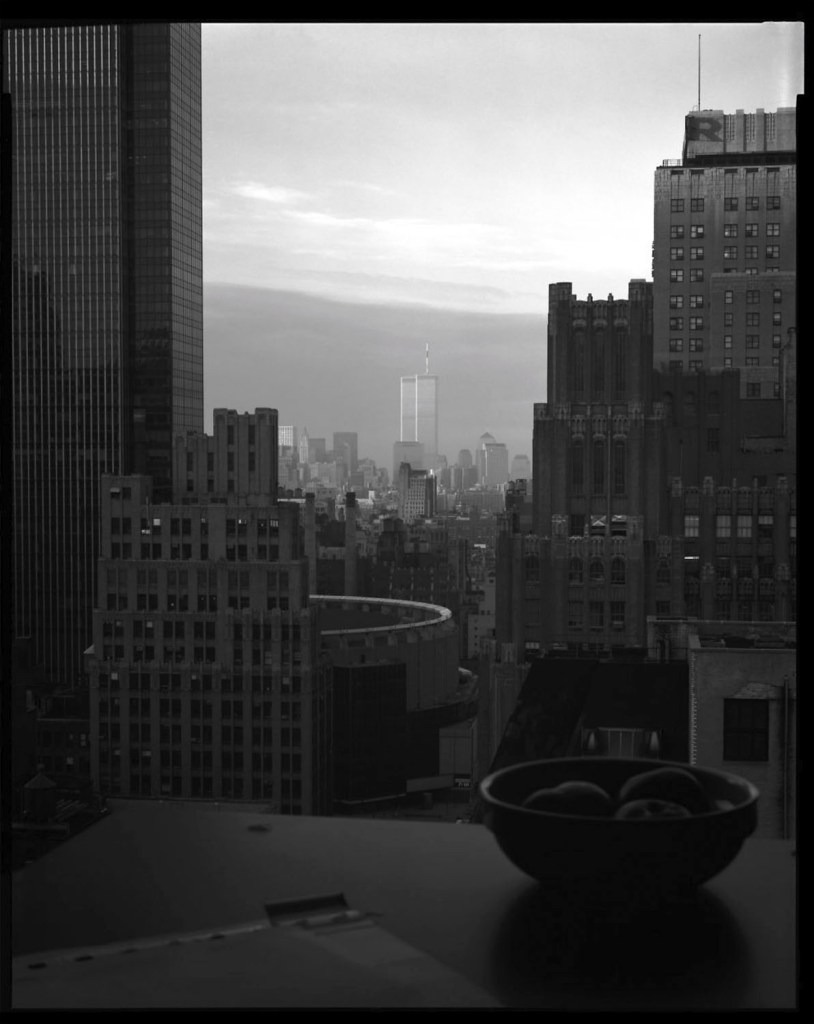

Installation view of the exhibition Flashes of Memory. Photography During the Holocaust 2023

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / David von Becker

Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, in cooperation with the Kunstbibliothek of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and the Freundeskreis Yad Vashem e. V., presents the highly acclaimed exhibition Flashes of Memory. Photography During the Holocaust at Berlin’s Museum für Fotografie (Museum of Photography). Featured for the first time in Germany, the exhibition presents a critical account of visual documentation – photographs and films – created during the Holocaust by German citizens and Nazi propaganda photographers, by Jewish photographers in the ghettos, and by members of the Allied forces during liberation. The exhibition focuses a spotlight on the circumstances under which each photograph was captured. It shows how the worldview of the documenting photographer – both official and private – influenced the image captured, while emphasising the different and unique viewpoints of the Jewish photographers as direct victims of the Holocaust.

For the German Nazi regime, photography and film played a crucial role in manipulating and mobilising the masses. These forms of propaganda were an elementary part of the National Socialist ideology. Conversely, the work of Jewish photographers during the Holocaust was part of their struggle for survival – depicting the living conditions of those incarcerated in ghettos. For the Jews, unsanctioned photography in the ghetto was punishable by death. Nonetheless, it was critical for them to document the atrocities so that the truth could one day be transmitted to all of humanity.

Upon liberation, the Allies recognised the need to document what they discovered in order to, combat future denial of these atrocities, justify their enormous losses on the battlefield, and gather evidence for upcoming war crimes trials. They were guided by the desire to educate the German population in the “spirit of democratic values.”

Flashes of Memory. Photography During the Holocaust displays photographs, films and artefacts, including cameras from archives and museums in the US, Europe and Israel. The exhibition curated by Director of the Yad Vashem Museums Division Vivian Uria was first opened in Jerusalem in January 2018 for International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Publication

An English-language as well as a German-language edition of the exhibition catalogue is available at the price of 38 € in the bookstore of the Museum für Fotografie.

Press release from the Museum für Fotografie website

Henryk Ross (Israeli born Poland, 1910-1991)

Ghetto police escorting residents for deportation

1942-1944

© Art Gallery of Ontario

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

To my knowledge this photograph is not in the exhibition

“Having an official camera, I could capture the entire tragic period in the Lodz ghetto. I did it knowing that if I were caught, my family and I would be tortured and killed.”

Henryk Ross

Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross

by Bernice Eisenstein (Author), Robert Jan van Pelt (Author), Michael Mitchell (Author), Eric Beck Rubin (Author), Maia-Mari Sutnik (Editor)

March 24, 2015 (Hardback)

Emotionally resonant photographs of everyday life in the Jewish Lódz Ghetto taken during WWII

From 1941 to 1944, the Polish Jewish photographer Henryk Ross (1910-1991) was a member of an official team documenting the implementation of Nazi policies in the Lódz Ghetto. Covertly, he captured on film scores of both quotidian and intimate moments of Jewish life. In 1944, he buried thousands of negatives in an attempt to save this secret record. After the war, Ross returned to Poland to retrieve them. Although some were destroyed by nature and time, many negatives survived.

This compelling volume (originally published in 2015 and now available in paperback), presents a selection of Ross’s images along with original prints and other archival material including curfew notices and newspapers. The photographs offer a startling and moving representation of one of humanity’s greatest tragedies. Striking for both their historical content and artistic quality, his photographs have a raw intimacy and emotional power that remain undiminished.

Distributed for the Art Gallery of Ontario

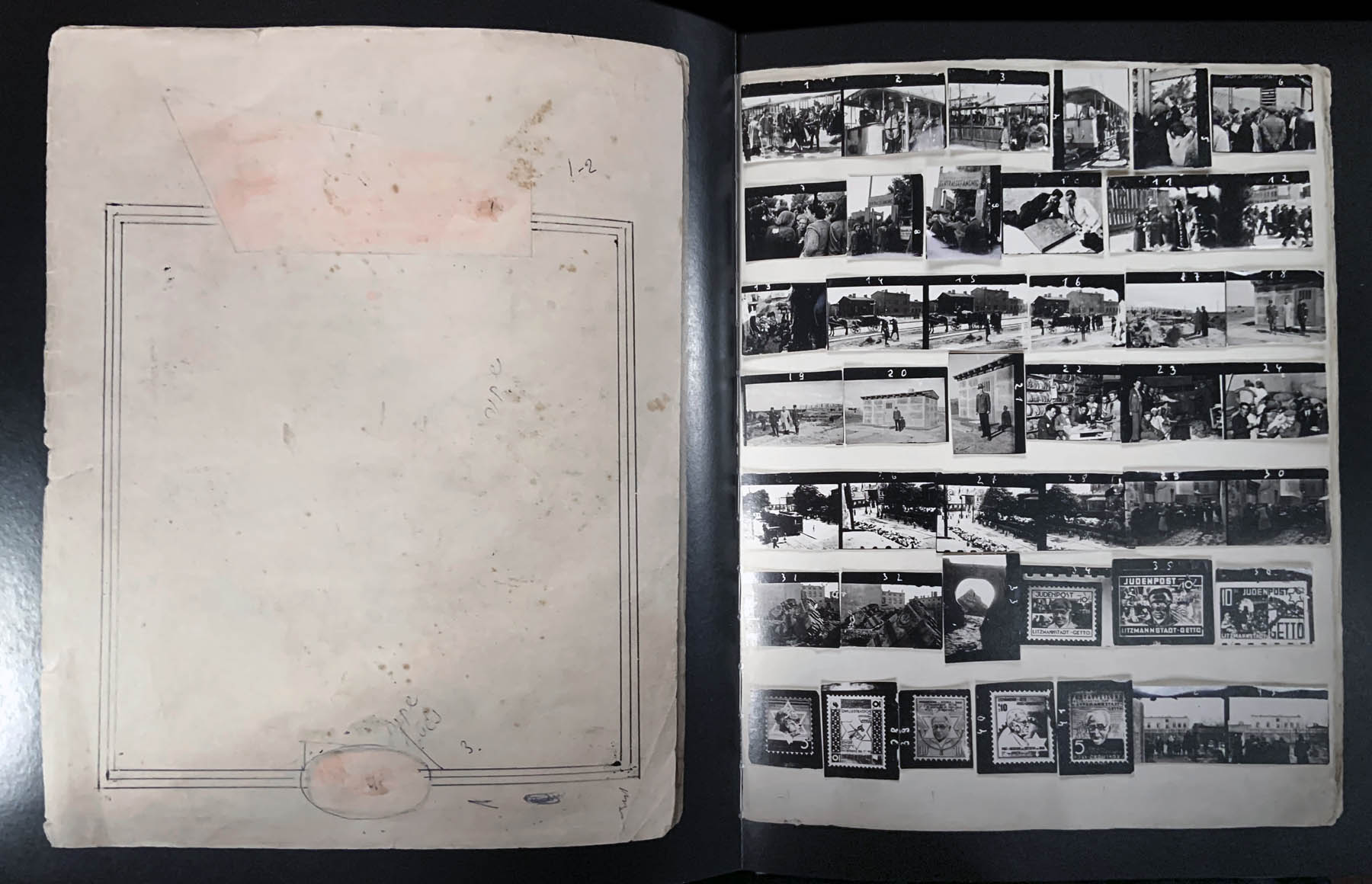

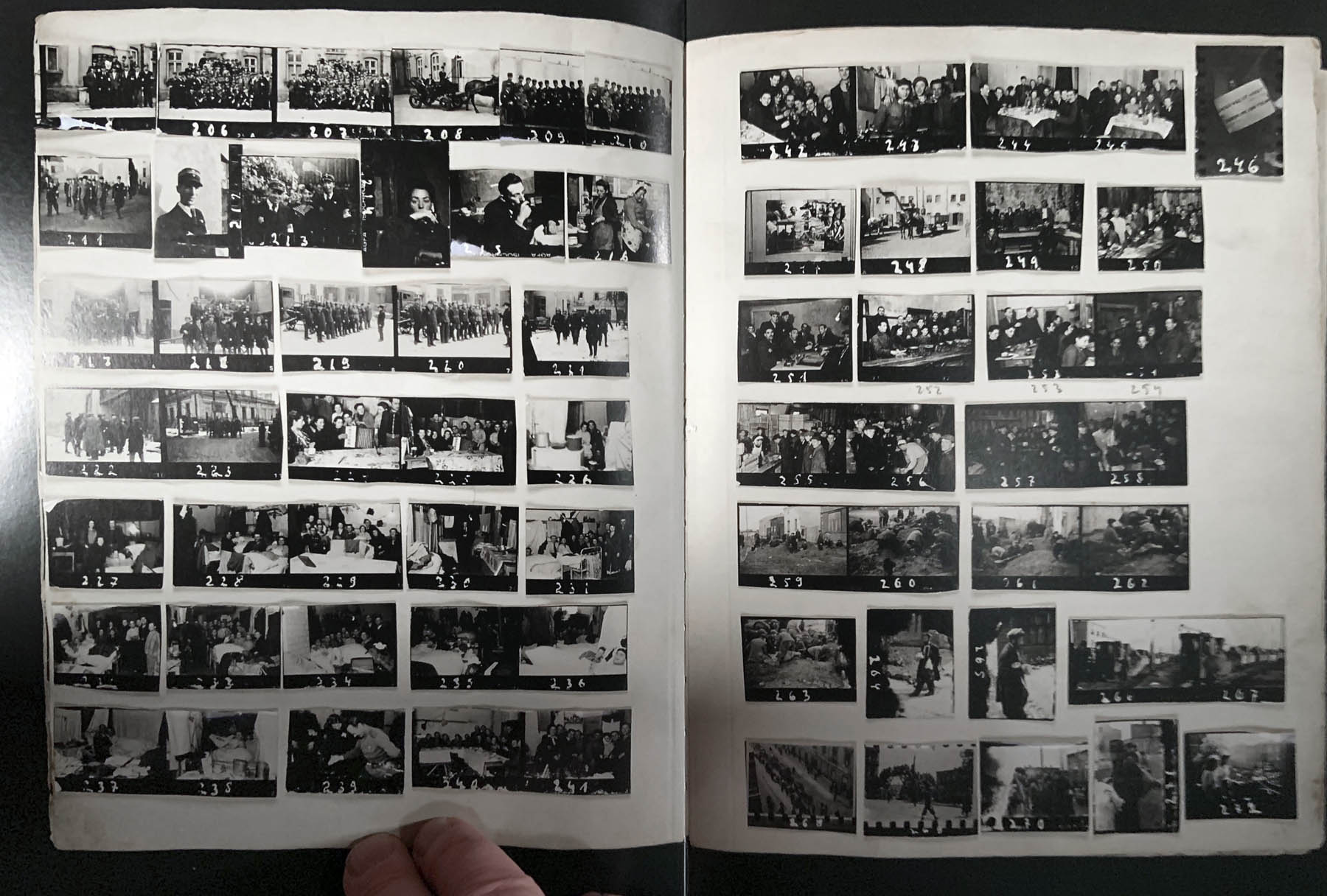

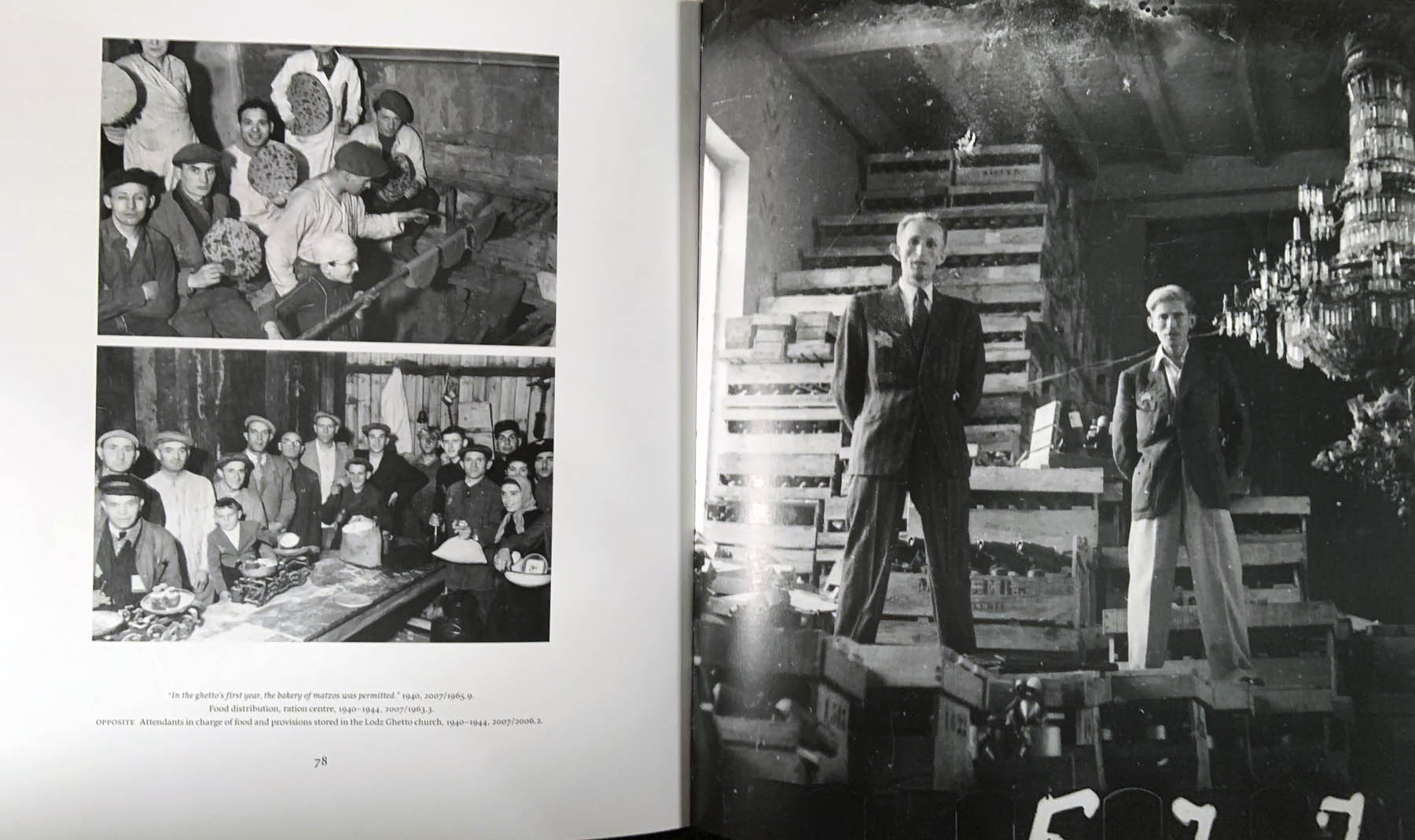

Pages from Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross

by Bernice Eisenstein (Author), Robert Jan van Pelt (Author), Michael Mitchell (Author), Eric Beck Rubin (Author), Maia-Mari Sutnik (Editor)

March 24, 2015 (Hardback)

Exhibition texts

Visual documentation is one of the major factors in shaping historical awareness of the Holocaust. Alongside archival documentation of the period’s events and the research on these records, visual documentation has contributed significantly towards knowledge of the Holocaust, influenced the manner in which it has been analysed and understood, and affected the way it has been engraved in the collective memory.

The camera, with its manipulative power, has tremendous impact and far reaching influence. Although photography purports to reflect reality as it is, it is essentially an interpretation of it, since elements such as worldview, values and moral perception influence the choice of the object to be photographed as well as how it is presented. When visual documentation is also used as a historical document, its use requires attributing the greatest of importance to these components.

Different parties photographed during the Holocaust. For the Nazi German regime, the visual media played a crucial role in propaganda as a means of expression and a tool for manipulating and mobilising the masses. This kind of documentation attests to Nazi ideology and how German leaders sought to mould their image in the public eye. Conversely, Jewish photography was a component in the struggle for survival of the Jews imprisoned in the ghettos, and a manifestation of underground activity that testified to their desire to document and transmit information on the tragedy befalling their people. The Allied armies, who understood the propaganda value of photographing the camps they liberated, documented the scenes revealed to them, bringing in official photographers and encouraging soldiers to document the Nazi horrors as evidence for future war crimes trials and in an effort to re-educate the German population.

This exhibit presents a critical examination of documentation through the camera lens, focusing on the circumstances of the photograph and the worldview of the photographer, while referring to the Jewish photographers’ different and unique viewpoints as direct victims of the Holocaust.

All items on display are replicas of the originals, except the cameras. The exhibition is curated by Vivian Uria, Director of the Yad Vashem Museums Division.

Political photography and filming in Nazi Germany

In the years following World War I, photography became a widespread pastime in Germany, both professionally and as a hobby. The Nazi Party was greatly aware of the importance of visual media as a propaganda and recruitment tool. As a result, this sector was developed vigorously after its rise to power. The Nazification (the process whereby the Nazi regime took over aspects of German life) of photography was first expressed in official photography, which served its communications efforts, the movie industry, and government institutions. Nazification was also significant in amateur photography, with the Party extending its patronage to photography clubs and periodicals. These processes were clearly reflected in the representation of the Jews in antisemitic propaganda and their increased persecution as documented by private photography.

“Today, many millions in many countries read [them] in the papers… hear them on the radio… and see them illustrated in pictures broadcast via the most modern technical means over continents and oceans to the great news agencies, or in innumerable copies in weekly news digests in movie theatres across the globe. Thereby public opinion is created.” Joseph Goebbels, “PK,” Das Reich, no.20, May 18, 1941, p. 2

Two Viewpoints on Photography in the Ghettos

The first ghettos were established in German-occupied Poland at the end of 1939. During 1940, their number grew rapidly. Most ghettos were created as a temporary and haphazard way to isolate the Jews from their surroundings. However, the majority eventually became the permanent residence for hundreds of thousands of Jews.

Tens of thousands of photos were taken in the ghettos, mostly by German photographers but also by several Jewish ones. Many of the German photographers acted in an official capacity for several different organisations of the Nazi state. Others photographed for personal objectives. The few Jewish photographers who managed to work in the ghettos did so in an official capacity for the Jewish ghetto leadership.

However, both by German and Jewish photographers, the borders between official and private photography were oftentimes blurred. The bias in German official photography was clear, and aimed at conveying various propaganda messages. In contrast, Jewish photography was carried out for the most part as a survival strategy vis-à-vis the Germans, with the goal of documenting and displaying a more realistic view of life in the ghetto.

Liberation of the Camps – Function and Distribution

Visual documentation played a central role for the Allied nations in revealing Nazi persecution, as well as displaying their own moral superiority visà-vis the fascist enemy. The Soviets were the first to liberate the concentration camps. Since private photography was almost nonexistent in the USSR during the war, visual evidence of liberation by Soviet forces remained in the hands of the official photographers. In contrast, the British and Americans encouraged their troops to engage in private photography in the liberated camps, as part of the effort to disclose Nazi crimes to the public as widely as possible. Another important consideration was the collection of visual documentation for trials of German war criminals, which the Allies planned to hold after the war.

To a great extent, liberation photos and films, including those that were staged, molded the collective and visual memory of the Holocaust for generations to come.

Text from the Museum für Fotografie website

Unknown photographer

Abraham Tory and Pnina Schinzon in the ghetto Kovno

December 1943

© Yad Vashem Archives

Pnina Tory (née Oshpitz), born in 1930 in Lithuania, describes her family; moving to and living in Kaunas when the war began, at which point her entire family was taken to jail for three days; the death of her first husband, Pinchas Sheinzon, at the Seventh Fort; entering the Kaunas ghetto with her daughter, Shulamit; assisting Avraham Tory, who was keeping a diary of life in the ghetto, by hiding the pages of the diary and taking dictation from him when he was too tired to write; marrying Avraham on August 10, 1944; going into hiding with Avraham and Shulamit; escaping with her daughter and husband in March 1945 and settling in Budapest, Hungary; sneaking into Italy, where she stayed for two years, with the help of a Palestinian Jewish Brigade; and immigrating to Palestine with Avraham and Shulamit on October 17, 1947.

Anonymous text. “Oral history interview with Pnina Tory,” on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website [Online] Cited 21/06/2023

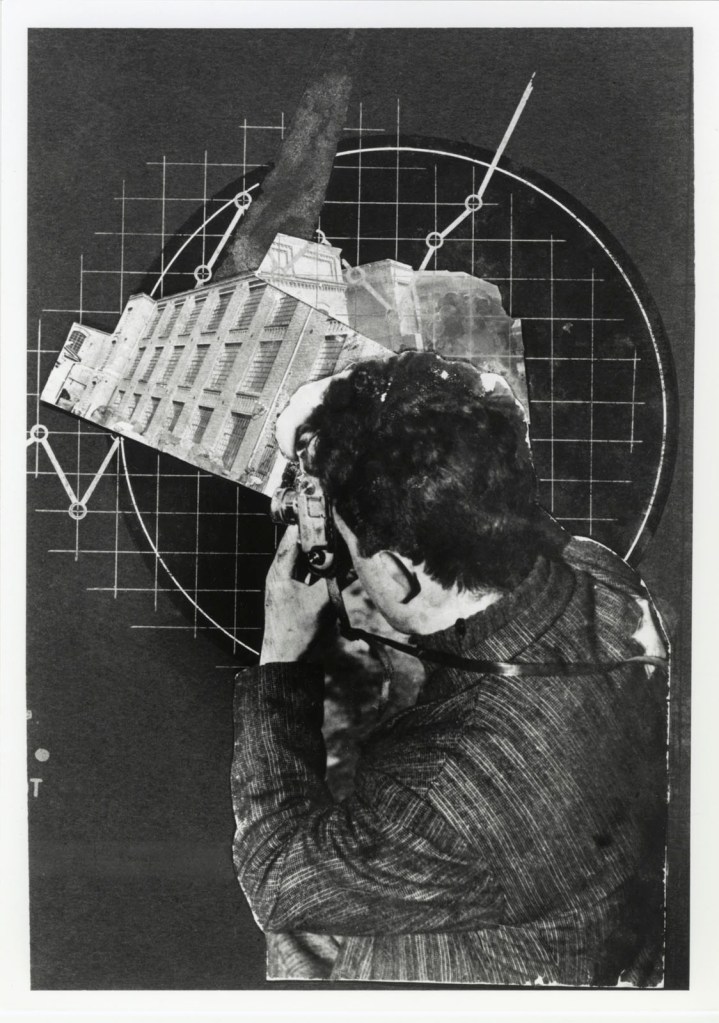

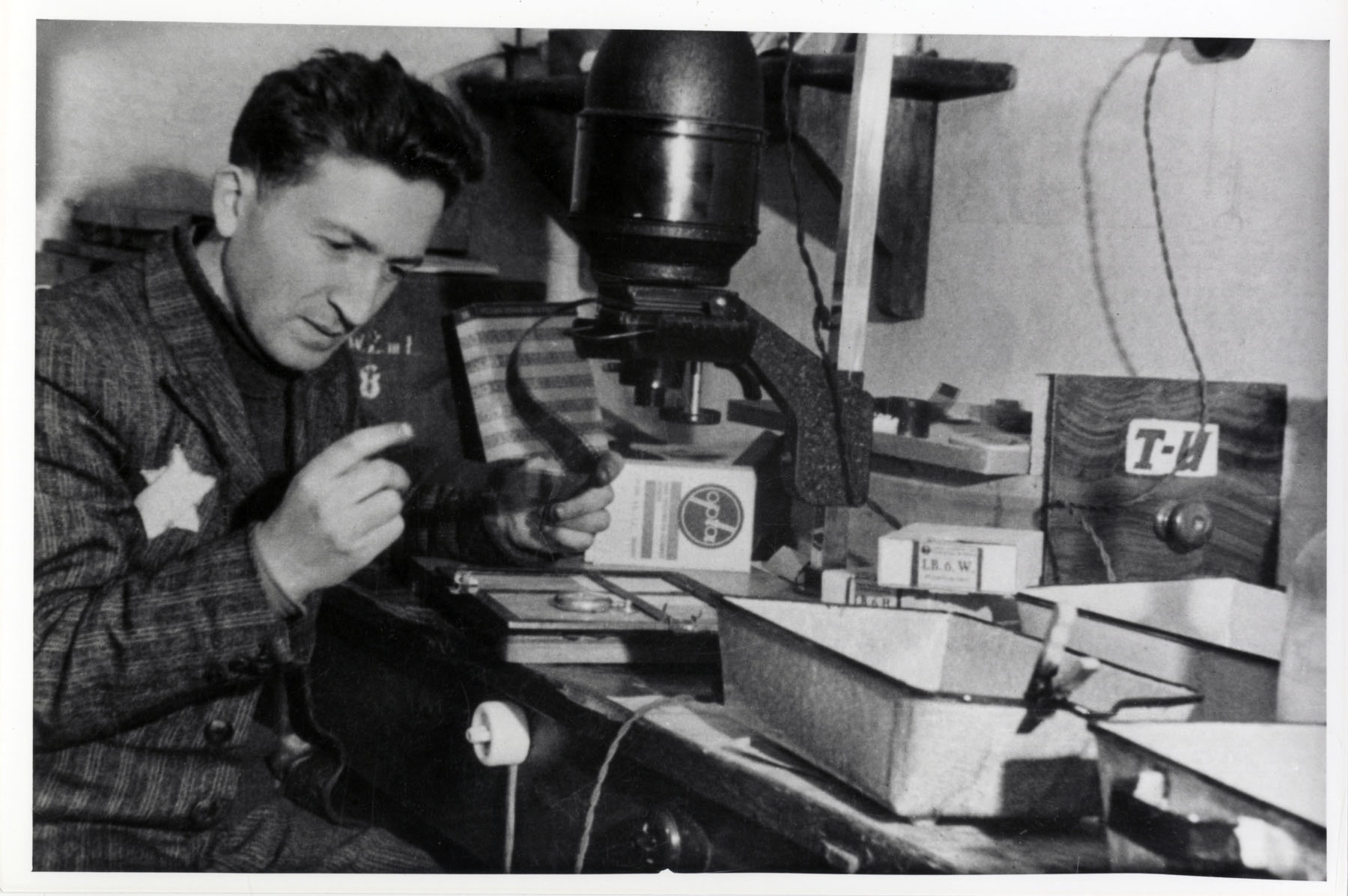

Aryeh Ben-Menachem (Israeli born Poland, 1922-2006)

Łódź ghetto photographer Mendel Grossman clandestinely photographing the deportation of Jews from the Łódź ghetto, the photo was taken by Grossman’s assistant, Aryeh Ben-Menachem

Nd

© Yad Vashem Archives

Arie Ben Menachem collaborated with Mendel Grossman, photographing, developing and distributing photos. During the Great Szpera, Grossman was obliged by the German authorities to photograph the corpses of Jews murdered in the streets for identification purposes – Menachem helped him in this by numbering the cartons in which the corpses were packed. In 1943, he created his own photo album with collages, using Grossman’s photos and an ironic commentary on the pages of the album in order to show the cruelty of the ghetto. In it, he described hunger, poverty and deportations.

In 1944, Menachem together with his family and the album were transported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where the album was taken from him and, thanks to the activities of the underground, he was to find himself in Kraków. After arriving in Auschwitz, Menachem’s mother, Hinda, was murdered. Arie Ben Menachem and his father were then transported to Groß-Rosen and to the Flossenburg camp, where Menachem’s father died during the death march. He himself survived, rescued by the American army, and after a few months in the hospital, in 1945 he made his way through Italy through Italy to Palestine, where he lived in the kibbutz Bet She’an, changed his name from Princ to Menachem, in order to commemorate his father and because of to the fact that one of the SS men in the Flossenburg camp had a dog whose name was Princ, and that he also married Ewa Bialer, whom he met in the ghetto. … In 1946, an album of Menachem was published by the Central Jewish Historical Commission, although the original of the album has not been found. After being liberated from captivity, Menachem began documenting the history of the Łódź ghetto, translated the “Kronika Getta Łódzkiego” into Hebrew and collaborated on the publication of the “Encyclopaedia of the Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem. He was also involved in cooperation with the District Commission for the Investigation of Crimes against the Polish Nation and was a member of the Union of Lodz residents in Israel, based in Tel Aviv. He was one of the experts on the history of the Łódź ghetto, having extensive library collections on the Litzmannstadt Ghetto and the Holocaust.

Text translated from the Polish Wikipedia website

Łódź Ghetto

The Łódź Ghetto or Litzmannstadt Ghetto (after the Nazi German name for Łódź) was a Nazi ghetto established by the German authorities for Polish Jews and Roma following the Invasion of Poland. It was the second-largest ghetto in all of German-occupied Europe after the Warsaw Ghetto. Situated in the city of Łódź, and originally intended as a preliminary step upon a more extensive plan of creating the Judenfrei province of Warthegau, the ghetto was transformed into a major industrial centre, manufacturing war supplies for Nazi Germany and especially for the Wehrmacht. The number of people incarcerated in it was increased further by the Jews deported from Nazi-controlled territories.

On 30 April 1940, when the gates closed on the ghetto, it housed 163,777 residents. Because of its remarkable productivity, the ghetto managed to survive until August 1944. In the first two years, it absorbed almost 20,000 Jews from liquidated ghettos in nearby Polish towns and villages, as well as 20,000 more from the rest of German-occupied Europe. After the wave of deportations to Chełmno extermination camp beginning in early 1942, and in spite of a stark reversal of fortune, the Germans persisted in eradicating the ghetto: they transported the remaining population to Auschwitz and Chełmno extermination camps, where most were murdered upon arrival. It was the last ghetto in occupied Poland to be liquidated. A total of 210,000 Jews passed through it; but only 877 remained hidden when the Soviets arrived. About 10,000 Jewish residents of Łódź, who used to live there before the invasion of Poland, survived the Holocaust elsewhere.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Mendel Grossman (Polish, 1913-1945)

Children on Łódź ghetto street

Nd

© Yad Vashem Archives

“Mendel takes out his camera. No more flowers, clouds, natures, stills, or landscapes. Amid the horror all around him he has found his destiny: to photograph and leave behind a testimony for all generations about the great tragedy unfolding before his eyes.”

Mendel Grossman, With a Camera in the Ghetto (Lochamei HaGeta’ot: Ghetto Fighters’ House and HaKibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 1970), p. 101 (Hebrew).

In the Lodz ghetto, thousands of photographs managed to survive and, in surviving, to commemorate the lives and deaths of the Jews there. Mendel Grossman was already a photographer when the ghetto was sealed in May, 1940, though previously he had photographed beauty and movement. He managed to get a job with the Department of Statistics in the ghetto, photographing “official” subjects such as employees of ghetto factories for the pictures on their work permits, and products made in the ghetto workshops for purposes of attracting German clients. Grossman’s job was the perfect camouflage for his true intention: to secretly record the terrible conditions in the Lodz Ghetto, and the suffering of the Jews there, for posterity. Grossman photographed, as well, the brutality of the Germans. His photography can be said to be photographic commemoration, as well as a form of resistance.

Grossman was strictly forbidden by Chaim Rumkowski, the head of the Lodz Judenrat, to take pictures in the ghetto. On December 8, 1941, Rumkowski wrote to Grossman, “I inform you herewith that you are not allowed to work in your profession for private purposes… Your photographic work is confined only to the activity in the department in which you are employed. You are therefore strictly prohibited to do any photographic work.” Much more threatening were the German prohibitions. As the pictures he took – including public executions, deportations to the death camp at Chelmno, and the bloating and misery of the ghetto inhabitants – were damning evidence against the Germans, Grossman could have been killed for taking them. Yet, despite pleas by his family and friends to stop endangering himself, Grossman continued to photograph what he saw in the Lodz ghetto. However, to fool the Germans and the police, he took his pictures in secret. Grossman slashed open the pockets of his coat, and kept his hands hidden inside them. His camera stayed underneath the coat, suspended by a strap around his neck. From his pockets, Grossman was able to manipulate the camera, aim, open his coat slightly, and snap the photographs. In this fashion, he accumulated thousands of pictures that tell us what life was like in the Lodz ghetto.

Grossman caught on film the deportations of the Lodz Jews to their deaths at Chelmno – he photographed people writing their last notes to their families, and children waiting behind chain-link fences to be taken to an unknown destination during the “Sperre”, the horrifying deportation in September, 1942 where almost all the children under ten years old were taken from the ghetto, and later murdered at Chelmno. …

Perhaps Grossman’s most successful photographic record was the one he made of his family. During the four years of the ghetto’s existence, Grossman lived together with his parents, two sisters, brother-in-law and little nephew, Yankush, in a crowded apartment. He watched and photographed his family as they carried on their day-to-day lives, waiting in never-ending lines for whatever food was being distributed, wolfing the food down first at the table, and then later, in bed under blankets, because the cold was so brutal (and perhaps the table had been burned for heat). As he carefully watched his family through the eye of his camera, he saw them slowly fading away. The many pictures he took of his family’s step-by-step deterioration created a horrifying photographic record typical of many other families in the ghetto. Looking at these pictures, the love and tenderness he felt towards his family members is evident. Grossman’s brother-in-law was the first in the family to die, on a rainy day after he came home from work. He dropped dead of starvation and exhaustion, wearing the same shabby clothes and wooden clogs in which Grossman had photographed him previously, gulping down soup. His father, emaciated and wrapped in a tallit, died as his son stood at his deathbed with his camera, recording his last moments. His mother, also photographed, died of starvation.

Grossman’s sadness is perhaps most palpable as we watch his the deterioration of his sister’s little son Yakov (Yankush) Freitag, a beautiful little boy. In the first pictures, a smile plays on his face as he helps his mother with her many chores, including waiting on infinite lines to bring home food. He was, no doubt, a curious child with an impish smile, well-tended by his mother. Ultimately, however, ghetto life reduced him to a sallow, blank-faced boy, robbed of his childhood and his natural inquisitiveness, deadened somehow. The contrast between the picture where, his eyes closed in delight, Yankush anticipates eating a single cherry brought to him by his uncle, “God knows from where, because nothing of the sort could have been found in the ghetto,” and that in which he is pictured sucking on a frozen carrot typical of the spoiled food available in the Lodz ghetto, his eyes full of pain and his hands swollen from the cold, are emblematic of the fate of Jewish children in the ghetto.

The story of Grossman’s family was typical of Jewish families in the Lodz ghetto, where over 20% of the population was killed by starvation. Grossman, by intensively photographing his loved ones, created a record of his family’s, and the ghetto’s, slow and ineluctable march toward death.

Grossman hid over ten thousand negatives in round tin cans – he gave many of the pictures away to whoever wanted them. He emphasized again and again in conversations with friends that he expected the negatives to reach Israel and to be exhibited as testimony of what took place in the ghetto, proof of this great crime. As the ghetto was being liquidated, he hid the tin cans in a wooden crate in a hollow space he made under the windowsill in his apartment. They were found by Grossman’s sister, Fajge, after the war ended, after Grossman himself had died at the age of 32 on a death march. All ten thousand negatives were indeed sent to Israel, to Kibbutz Nitzanim. However, when the Kibbutz fell into Egyptian hands during the War of Independence, the treasure was lost. Only the prints distributed by Grossman, and some hidden by his friend Nachman Zonabend at the bottom of a well in the ghetto, survived.

Sheryl Silver Ochayon. “Who Took The Pictures?” on the Yad Vashem website Nd [Online] Cited 13/06/2023

My Secret Camera

Gulliver Books, Hardcover – April 1, 2000

Photographs by Mendel Grossman (Photographer), text by Frank Dabba Smith (Author)

In 1940 as Nazi troops rolled across Europe, countless Jewish families were forced from their homes into isolated ghettos, labor and concentration camps. In the Lodz Ghetto in Poland, Mendel Grossman refused to surrender to the suffering around him, secretly taking thousands of heartrending photographs documenting the hardship and the struggle for survival woven through the daily lives of the people imprisoned with him. Someday, he hoped, the world would learn the truth. My Secret Camera is his legacy.

Unknown photographer

Łódź ghetto photographer Mendel Grossman in his laboratory in the ghetto

Nd

© Yad Vashem Archives

Cropped photograph of Łódź ghetto photographer Mendel Grossman pasted on a page of one of the albums prepared by the Department of Statistics for the “Judenrat” (Jewish Council)

© Yad Vashem Archives

Zvi Kadushin (Lithuanian Jewish, 1910-1997)

Jews collecting potatoes in the ghetto Kovno

September 1943

© Yad Vashem Archives

George Kadish, born Zvi (Hirsh) Kadushin (1910 – September 1997), was a Lithuanian Jewish photographer who documented life in the Kovno Ghetto during the Holocaust, the period of the Nazi German genocide against Jews.

Prior to World War II he was a mathematics, science and electronics teacher at a Hebrew High School in Kovno, Lithuania.

As a hobby, Kadish was a photographer. He was skilled at making home-made cameras. During the period of Nazi control of Lithuania (along with indigenous Lithuanian collaborators) he successfully photographed various scenes of life and its difficulties in the ghetto in clandestine circumstances. Kadish constructed cameras by which he could photograph through the buttonhole of his coat or over a window sill. He was able to photograph sensitive scenes that would attract the ire of Nazis or collaborators, such as scenes of people gathered for forced labor, burning of the ghetto, and deportations.

Text from the Wikipedia website

In the Kovno Ghetto

The Kovno ghetto had two parts, called the “small” and “large” ghetto, separated by Paneriu Street. Each ghetto was enclosed by barbed wire and closely guarded. Both were overcrowded, with each person allocated less than ten square feet of living space. The Germans continually reduced the ghetto’s size, forcing Jews to relocate several times. The Germans destroyed the small ghetto on October 4, 1941, and killed almost all of its inhabitants at the Ninth Fort. Later that same month, on October 29, 1941, the Germans staged what became known as the “Great Action.” In a single day, they shot 9,200 Jews at the Ninth Fort.

Kadish took every opportunity possible to document day-to-day life in the Kovno ghetto and, after his escape in 1944, the ghetto’s final days. The results constitute one of the most significant photographic records of ghetto life during the Holocaust era. Photographing life in the Kovno ghetto was an extremely risky venture. The Germans strictly prohibited it, and as with all defiant acts, they did not hesitate to murder offenders.

Acquiring and developing film secretly outside the ghetto were just as perilous as using hidden cameras inside. Kadish received orders to work as an engineer repairing x-ray machines for the German occupation forces in the city of Kovno. Once in the city, he discovered opportunities to barter for film and other necessary supplies. He developed his negatives at the German military hospital, using the same chemicals he used to develop x-ray film, and succeeded in smuggling them out in sets of crutches.

The subjects of Kadish’s photographic portraits were varied, but he seemed especially interested in capturing the reality of the ghetto’s daily life. In June 1941, witnessing the brutality of the initial pogroms, he photographed the Yiddish word Nekoma (“Revenge”) found scrawled in blood on the door of a murdered Jew’s apartment.

Camera in hand, or whenever necessary, placed to record subjects through a buttonhole of his overcoat, he photographed Jews humiliated and tormented by Lithuanian and German guards in search for smuggled food, Jews dragging their belongings from one place to another on sleds or carts, Jews concentrated in forced work brigades, and so forth. Kadish also recorded the new regimen of regulated daily activities at the Ältestenrat’s (as the Jewish council in Kovno was known) food gardens and in schools, orphanages, and workshops. In addition to depicting the severe conditions of ghetto life, he had an insider’s eye for portraiture, the desolation of deserted streets, and the intimacy of informal, improvised gatherings.

Among Kadish’s last photographs from inside the ghetto are those recording the deportation of ghetto prisoners to work camps in Estonia. In July 1944, after escaping from the ghetto, across the river, he photographed the ghetto’s liquidation. Once the Germans fled, he returned to photograph the ghetto in ruins and the small groups who had survived the final days in hiding.

Saving the Collection

Kadish recognised early on the danger of losing his precious collection. He enlisted the assistance of Yehuda Zupowitz, a high-ranking officer in the ghetto’s Jewish police, to help hide his negatives and prints. Zupowitz never revealed his knowledge of Kadish’s work or the location of his collection, even during the “Police Action” of March 27, 1944, when Zupowitz was tortured and killed at the Ninth Fort prison. Kadish retrieved his collection of photographic negatives upon his return to the destroyed ghetto.

After Germany’s surrender on May 8, 1945, Kadish left Lithuania for Germany with his extraordinary documentary trove. In the American zone of occupied Germany, he mounted exhibitions of his photographs for survivors residing in displaced persons camps. Since then, several museums, including New York’s Jewish Museum, have formally exhibited his work.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC. “George Kadish,” on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website Nd [Online] Cited 13/06/2023

The Kovno Ghetto was a ghetto established by Nazi Germany to hold the Lithuanian Jews of Kaunas during the Holocaust. At its peak, the ghetto held 29,000 people, most of whom were later sent to concentration and extermination camps, or were shot at the Ninth Fort. About 500 Jews escaped from work details and directly from the ghetto, and joined Jewish & Soviet partisan forces in the distant forests of southeast Lithuania and Belarus. …

Resistance

Throughout the years of hardship and horror, the Jewish community in Kovno documented its story in secret archives, diaries, drawings and photographs. Many of these artefacts lay buried in the ground when the ghetto was destroyed. Discovered after the war, these few written remnants of a once thriving community provide evidence of the Jewish community’s defiance, oppression, resistance, and death. George Kadish (Hirsh Kadushin), for example, secretly photographed the trials of daily life within the ghetto with a hidden camera through the buttonhole of his overcoat.

The Kovno ghetto had several Jewish resistance groups. The resistance acquired arms, developed secret training areas in the ghetto, and established contact with Soviet partisans in the forests around Kovno.

In 1943, the General Jewish Fighting Organization (Yidishe Algemeyne Kamfs Organizatsye) was established, uniting the major resistance groups in the ghetto. Under this organisation’s direction, some 300 ghetto fighters escaped from the Kovno ghetto to join Jewish partisan groups. About 70 died in action.

The Jewish council in Kovno actively supported the ghetto underground. Moreover, a number of the ghetto’s Jewish police participated in resistance activities. The Germans executed 34 members of the Jewish police for refusing to reveal specially constructed hiding places used by Jews in the ghetto.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Unknown photographer

Der Stürmer display case in a rural area of Germany before World War II

Nd

© Yad Vashem Archives

Der Stürmer (pronounced [deːɐ̯ ˈʃtʏʁmɐ]; literally, “The Stormer / Attacker / Striker”) was a weekly German tabloid-format newspaper published from 1923 to the end of World War II by Julius Streicher, the Gauleiter of Franconia, with brief suspensions in publication due to legal difficulties. It was a significant part of Nazi propaganda, and was virulently anti-Semitic. The paper was not an official publication of the Nazi Party, but was published privately by Streicher. For this reason, the paper did not display the Nazi Party swastika in its logo. …

Most of the paper’s readers were young people, and people from the lowest strata of German society. Copies of Der Stürmer were displayed in prominent red Stürmerkästen (display boxes) throughout the Reich. As well as advertising the publication, the cases also allowed its articles to reach those readers who either did not have time to buy and read a newspaper in depth, or could not afford the expense. In 1927, Der Stürmer sold about 27,000 copies every week. By 1935, its circulation had increased to around 480,000.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Heinrich Hoffmann (German, 1885-1957)

The Nazi Party’s official photographer and Adolf Hitler’s personal photographer, sitting to Hitler’s right during a boat ride on the Rhine River

Bad Godesberg 1933

© Yad Vashem Archives

Heinrich Hoffmann (12 September 1885 – 15 December 1957) was Adolf Hitler’s official photographer, and a Nazi politician and publisher, who was a member of Hitler’s intimate circle. Hoffmann’s photographs were a significant part of Hitler’s propaganda campaign to present himself and the Nazi Party as a significant mass phenomenon. He received royalties from all uses of Hitler’s image, even on postage stamps, which made him a millionaire over the course of Hitler’s rule. After the Second World War he was tried and sentenced to 10 years in prison for war profiteering. He was classified by the Allies’ Art Looting Investigators to be a “major offender” in Nazi art plundering of Jews, as both art dealer and collector and his art collection, which contained many artworks looted from Jews, was ordered confiscated by the Allies. Hoffmann’s sentence was reduced to 4 years on appeal. In 1956, the Bavarian State ordered all art under its control and formerly possessed by Hoffmann to be returned to him.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Unknown photographer

US Army cameraman and photographer at the Ohrdruf concentration camp after its liberation

April 1945

© Yad Vashem Archives

Ohrdruf was a German forced labor and concentration camp located near Ohrdruf, south of Gotha, in Thuringia, Germany. It was part of the Buchenwald concentration camp network. …

As the American troops advanced towards Ohrdruf, the SS began evacuating almost all prisoners on death marches to Buchenwald on April 1. During these marches, SS, Volkssturm, and members of the Hitler Youth killed an estimated 1,000 prisoners. Mass graves were re-opened and SS men tried to burn the corpses. The SS guards killed many of the remaining prisoners in the Nordlager that were deemed too ill to walk to the railcars. After luring them to the parade ground, claiming that they were to be fed, the SS shot them and left their corpses lying in the open.

In addition to those killed on the death marches, an estimated 3,000 inmates died from exhaustion or were murdered inside the camp. Together with those worked to death here but moved elsewhere to die, estimates of the total number of victims are around 7,000.

Liberation

Ohrdruf was liberated on April 4, 1945, by the 4th Armored Division, led by Brigadier General Joseph F. H. Cutrona, and the 89th Infantry Division. It was the first Nazi concentration camp liberated by the U.S. Army.

When the soldiers of the 4th Armored Division entered the camp, they discovered piles of bodies, some covered with lime, and others partially incinerated on pyres. The ghastly nature of their discovery led General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe, to visit the camp on April 12, with Generals George S. Patton and Omar Bradley. After his visit, Eisenhower cabled General George C. Marshall, the head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, describing his trip to Ohrdruf:

… the most interesting – although horrible – sight that I encountered during the trip was a visit to a German internment camp near Gotha. The things I saw beggar description. While I was touring the camp I encountered three men who had been inmates and by one ruse or another had made their escape. I interviewed them through an interpreter. The visual evidence and the verbal testimony of starvation, cruelty and bestiality were so overpowering as to leave me a bit sick. In one room, where they were piled up twenty or thirty naked men, killed by starvation, George Patton would not even enter. He said that he would get sick if he did so. I made the visit deliberately, in order to be in a position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to ‘propaganda.’

At Ohrdruf concentration camp, 4th Armored Division soldier David Cohen said: “We walked into a shed and the bodies were piled up like wood. There are no words to describe it.” He said the smell was overpowering and unforgettable.

Seeing the Nazi crimes committed at Ohrdruf made a powerful impact on Eisenhower, and he wanted the world to know what happened in the concentration camps. On April 19, 1945, he again cabled Marshall with a request to bring members of Congress and journalists to the newly liberated camps so that they could bring the horrible truth about German Nazi atrocities to the American public. That same day, Marshall received permission from the Secretary of War, Henry Lewis Stimson, and President Harry S. Truman for these delegations to visit the liberated camps.

Ohrdruf had also made a powerful impression on Patton, who described it as “one of the most appalling sights that I have ever seen.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Unknown photographer

Display panel with photographs of the liberation of the concentration camps during a session of the International Court in Nuremberg

1946

© Yad Vashem Archives

Rüdiger Halt (German) (designer)

Leni Riefenstahl (German, (photographer)

Die Götter des Stadions (The Gods of the Stadium)

1938

Offset lithographic film poster for the film Olympia printed on off-white paper, and adhered to a white linen backing

Height: 35.250 inches (89.535cm)

Width: 25.250 inches (64.135cm)

Poster for the German propaganda sports film, “Olympia” (The Gods of the Stadium), about the 1936 Summer Olympics held in Berlin, released in April, 1938. The poster features a photographic image of German Olympic athlete Erwin Huber in a discus throwing stance. Huber participated in the 1928 and the 1936 games. The poster image is reproduced from a scene in the opening of the film. The stance is reminiscent of the Discobolus, an ancient Greek statue of a discus thrower, which symbolises the Olympics and the athletic ideal. Nazi authorities used the games to promote an image of a new, strong, and united Germany to foreign spectators and journalists while masking the regime’s targeting of Jews and Roma (Gypsies), as well as Germany’s growing militarism. Germany fielded the largest team, 348 athletes, and won the most medals. The games were used to promote the myth of “Aryan” racial superiority, physical prowess, and symbolise that “Aryan” culture was the rightful heir of classical antiquity. Leni Riefenstahl, who directed “Triumph des Willens” (“Triumph of the Will”), shot at the 1934 Nuremberg Rally, was commissioned by the Nazis to produce a film about the Berlin games, which would also promote all these ideals. Riefenstahl made two films, “Olympia Part I: Festival of the Nations” and “Part II: Festival of Beauty” and combined them to create “Olympia.” Riefenstahl’s work pioneered numerous cinematographic techniques and won Best Foreign Film honours at the Venice Film Festival and a special award from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for depicting the joy of sport.

Anonymous. “Poster for the Lenie Riefenstahl film, Olympia, about the 1936 Olympics,” on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website Nd [Online] Cited 13/06/2023

Flashes of Memory. Photography During the Holocaust exhibition poster

Museum für Fotografie

Jebensstraße 2, 10623 Berlin, Germany

Phone: +49 30 266424242

Opening hours:

Tues – Sunday 11am – 7pm

![Willy Römer (German, 1887-1979) 'Election propaganda with car, flags and posters "Vote List 4"' [Election propaganda automobile of the German National Party on the streets of Berlin] January 1919 Willy Römer (German, 1887-1979) 'Election propaganda with car, flags and posters "Vote List 4"' [Election propaganda automobile of the German National Party on the streets of Berlin] January 1919](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/roemer_wahlpropaganda-web.jpg)

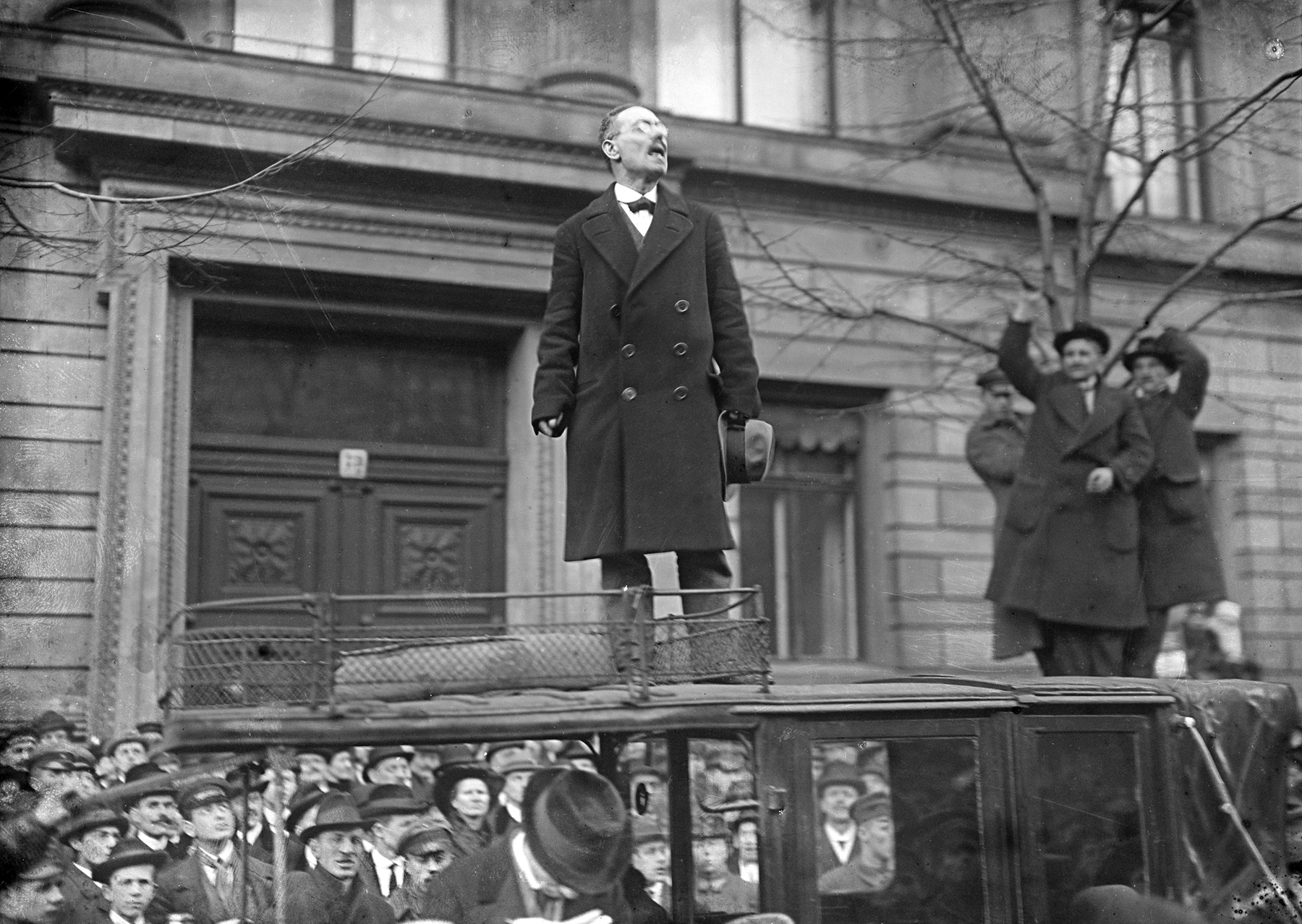

![Walter Gircke (German, 1885-1974) 'Elections to the National Assembly in Berlin. Agitation by the actress Senta Söneland in front of the Zoologischer Garten station' [National Assembly in Berlin: agitation by the actress Senta Söneland] January 1919 Walter Gircke (German, 1885-1974) 'Elections to the National Assembly in Berlin. Agitation by the actress Senta Söneland in front of the Zoologischer Garten station' [National Assembly in Berlin: agitation by the actress Senta Söneland] January 1919](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/gircke_wahlen-web.jpg)

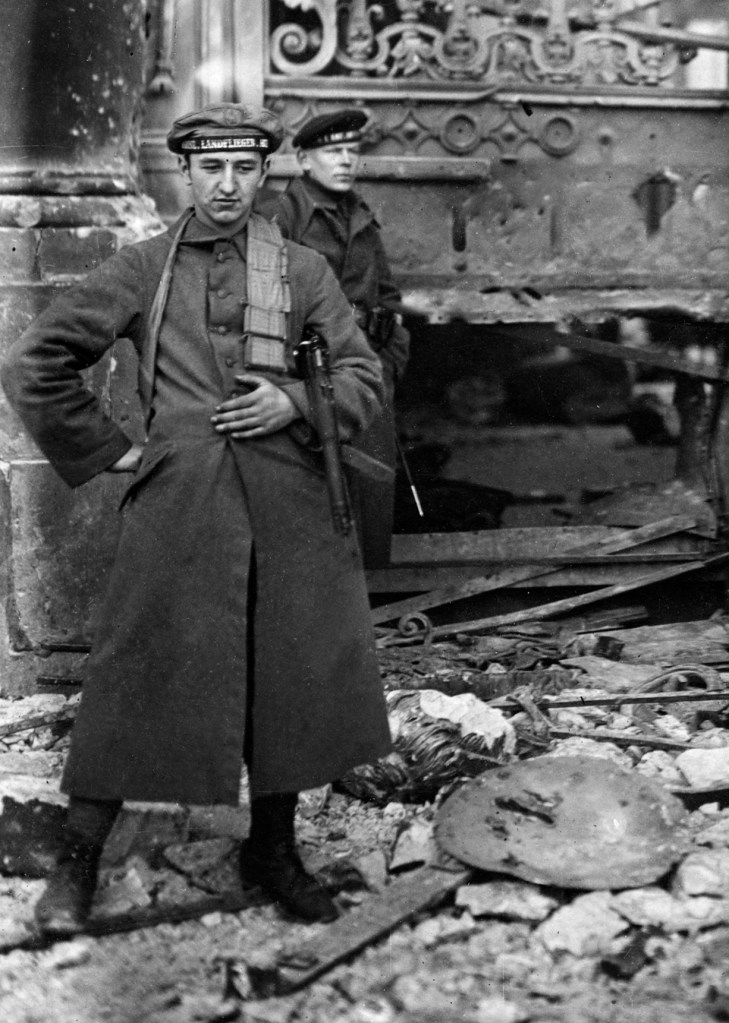

![Willy Römer (German, 1887-1979) 'Fighting in the Berlin newspaper district. The Vorwärts building after being bombarded by government troops' [The Spartacist had barricaded themselves inside the Vorwärts building. The photo shows the Vorwärts building after an artillery assault by government troops] 11.1.1919 Willy Römer (German, 1887-1979) 'Fighting in the Berlin newspaper district. The Vorwärts building after being bombarded by government troops' [The Spartacist had barricaded themselves inside the Vorwärts building. The photo shows the Vorwärts building after an artillery assault by government troops] 11.1.1919](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/roemer_kaempfe_berliner_zeitungsviertel-web.jpg?w=755)

![Willy Römer (German, 1887-1979) 'View of the funeral procession in the Frankfurter Allee on the occasion of the funeral of Rosa Luxemburg' [Funeral of Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. Funeral procession on Große Frankfurter Strasse] 13.6.1919 Willy Römer (German, 1887-1979) 'View of the funeral procession in the Frankfurter Allee on the occasion of the funeral of Rosa Luxemburg' [Funeral of Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. Funeral procession on Große Frankfurter Strasse] 13.6.1919](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/roemer_blick_auf_trauerzug-web.jpg?w=726)

![Willy Römer (German, 1887-1979) 'Dismissed soldiers and unemployed. The gaming tables in front of the employment office in Gormannstraße' [Gambling den in front of the employment agency on Gormannstraße. For strengthening during the game, there is coffee and cake at the next table] 24.11.1919 Willy Römer (German, 1887-1979) 'Dismissed soldiers and unemployed. The gaming tables in front of the employment office in Gormannstraße' [Gambling den in front of the employment agency on Gormannstraße. For strengthening during the game, there is coffee and cake at the next table] 24.11.1919](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/roemer_entlassene_soldaten_arbeitslose-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.