Exhibition dates: 30th April – 12th October, 2025

Curator: Clément Chéroux, Director, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

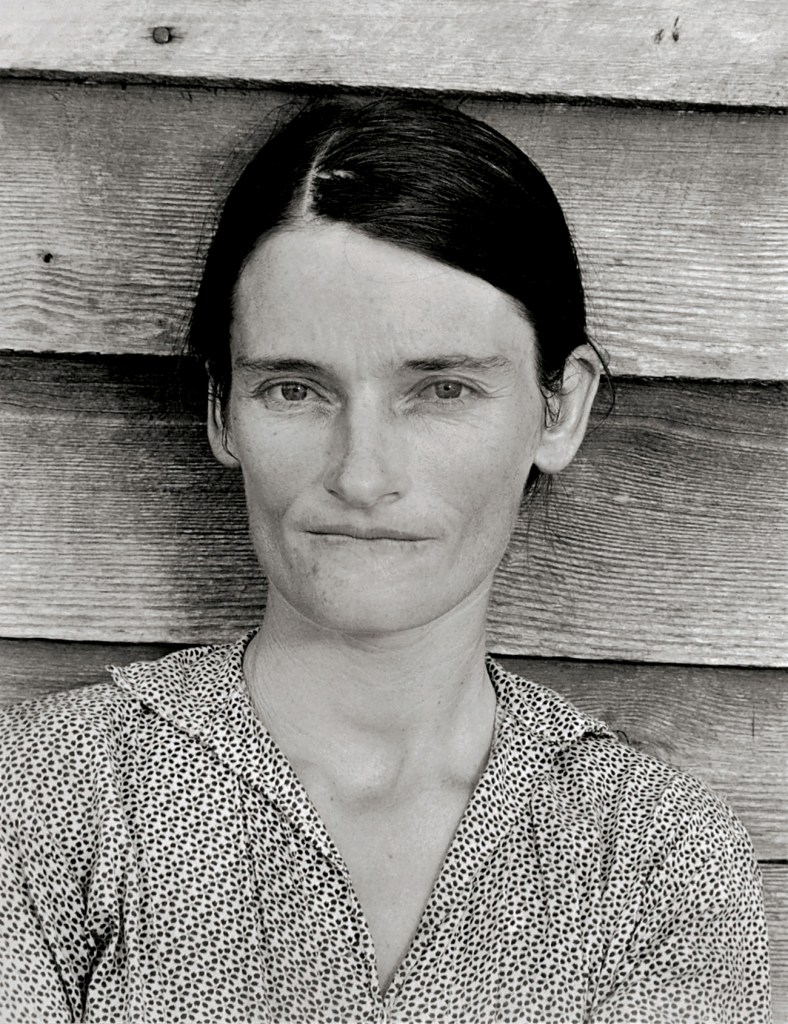

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

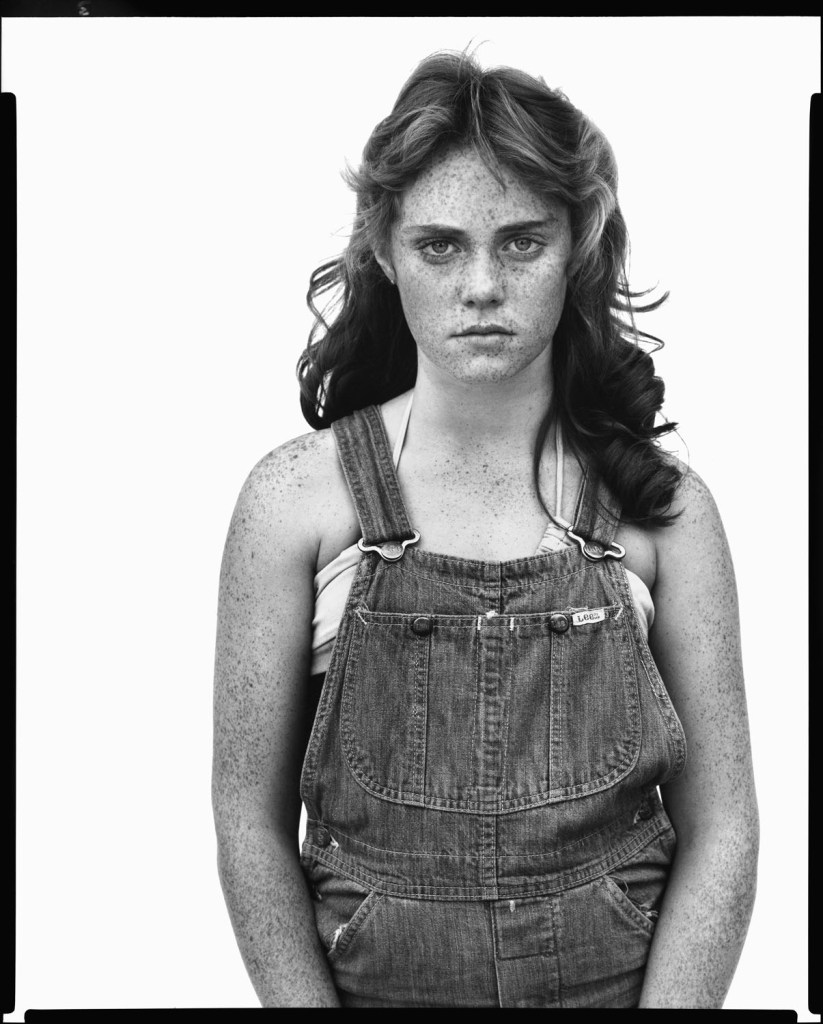

Sandra Bennett, twelve year old, Rocky Ford, Colorado, August 23, 1980

1980

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

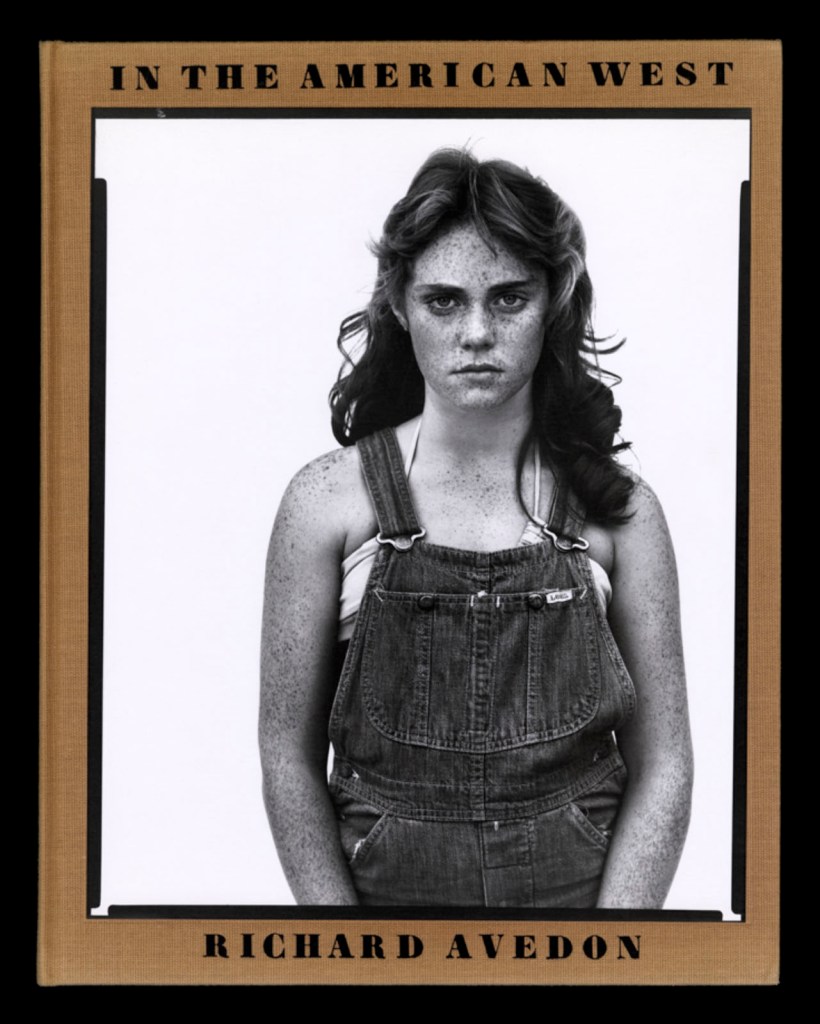

Myths of the American West

This is a magnificent exhibition of the 103 photographs that form American photographer Richard Avedon’s series and subsequent book of the same name, In The American West 1984.

“Avedon spent the next six years, from 1979 to 1984, traveling to 189 towns in 17 states – Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming – and even up into Canada. He conducted 752 sittings, exposing 17,000 sheets of film through his large-format view camera.”1

“For five years, Avedon photographed miners, drovers, showmen, vendors, and vagabonds, alone or in small groups, in front of his view camera against a white background that enhanced their features, postures, and expressions. He thus created a striking portrait of this region and its residents, a departure from traditional representations and glorifications of the myth of the American West.”2

Using relatively small reference prints (40 x 50cm) not originally intended for exhibition made by the photographer at the time to produce the prints for his book, the hanging of this exhibition “on the line”, “follows the book, from the first to the last image… The blank pages are represented on the wall by a gap equivalent to the width of a frame, like a half-space. We have thus reproduced the rhythm of someone leafing through the book. We can see through this that Richard Avedon and Marvin Israel (1924-1984), artistic director, have constructed the rhythm of these images in a very precise manner”3, one which follows “the dynamics of the photograph on the page, and the inter-relationships, scaling and sequencing of groups of photographs.”

Breaking with the code of social documentary photography, Avedon brings to this project all his undoubted skill as a New York fashion photographer, reassigned to the artistic sphere: clarity of purpose, simplicity of representation, aesthetic beauty, clinical detail and contextless backgrounds.

While there is a long history of the use of plain backgrounds in portrait photography dating back to the infancy of the medium, Avedon was one of the first to employ such a technique in contemporary (I’d like to say postmodern) photo-portraits, where the subject is disassociated from their location, job, culture and is posed by the director of the theatrical show.

Over the five years of the project, Avedon worked closely with his subjects, often advertising for people to be photographed, street-casting his sitters, paying them for their time and providing prints of the resultant photographs. He or one of his assistants “took a Polaroid photograph of each of the models intended to pose. Clément Chéroux (curator of the exhibition) notes that, “Comparing these polaroids with Avedon’s portraits shows his ability to transcend the appearance of his models.”4

During the photographic sessions Avedon shot not from behind his camera but to the side, like the director of a play in rehearsal, front of stage. “He had a strong connection with his subjects, mimicking their position, and asking them to respond to a very small gesture by showing himself moving in one direction or another, and I think a lot of the work is in this relationship that he was establishing with the subject. Photographic literature usually focuses on the framing, the composition, but for me, this kind of interaction he was able to develop with the subject is where the work is, where he’s transforming the people that he met into a Richard Avedon photograph.”5

“A conductor of his own composition, Richard Avedon was able to weave an unparalleled fusional relationship with his models, while implacably directing them through his gaze, gestures or voice.”6

Thus, through his imagination, his direction and his creative experience Avedon conjured a subjective view of the American West every bit as much as myth as those cowboys in John Wayne movies, a kind of counter-mythology undercutting the eulogising of the American West, but a staged, fabricated, youthful, desolate, mysterious mythology none the less – a series which captures the ethos of the era (global recession, disease, dis/ease) counter to the one hoped for, “representing a sad, unsmiling America, which does not correspond to the one dreamed of.”7

Think that damned foreigner Robert Frank and his book The Americans, pointing the bone at the belly of the United States of America, holding a mirror up to their reflection8 and they certainly not liking what they saw. Indeed Avedon, while American and respectful of his subjects, could be seen as an interloper from New York exposing through his photographs the underbelly of this vast country colonised through divine providence and Manifest Destiny.

Avedon, while undercutting the myth of the American West through his storytelling, doesn’t seek to document, exploit or misrepresent his subjects, but to subjectively present them as on a theatrical set devoid of scenery – where their very appearance becomes scene / seen. As he himself said, “My concern is… the human predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may simply be my own.”

“Richard Avedon showed his own America, those we do not see, those we pass by without pausing, those who do the work, those who make America work.”9

Neither the series nor the exhibition are without fault, however.

While I believe that Avedon’s exceptional magnum opus In The American West has become one of the truly iconic photographic portrait series of the 20th century it can also be seen as problematic, not in the photographic sense, but in the sense that the photographs did not reflect the diverse reality of the West’s population. While the series may be Avedon’s subjective mythologising of the American West some people, myself included, find the lack of representation of Black Americans, Asian Americans and other ethnicities that have been integral to the development of the American West a point of contention. Are they not those that also do the work, those who also make America work, as much as those Avedon chose to photograph? Indeed there is a “significant demographic blind spot” in the whole series…

The other blind spot is the inability of commentators such as myself to publish some of the preparatory Polaroids that Avedon and his assistants took before posing his subjects. I asked the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson for some of the Polaroids to illustrate this posting and they said that none were available. Since the exhibition promotes the presence of these unpublished documents and the curator Clément Chéroux notes their importance for their ability to compare them with Avedon’s finished portraits, showing “his ability to transcend the appearance of his models,” they become vital to understanding Avedon’s creative process … and it would have been great to see the visualisation of his subjects from beginning to end.

Examples of these Polaroids are rare online but some can be seen in the article “Before And After: Polaroids then Magic from Richard Avedon, In the American West,” on the Flashbak website June 9, 2025.

Finally, in the juxtaposition of Polaroid and finished portrait we can begin to perceive the magical transformation and artistry and humanism of the man, Avedon, as he visualises his ode to the American West, composing his subjects so that they engage with the viewer directly from the photographic frame – the dynamics of the photographs creating iconic images of memorable characters, collectively constructing the rhythm of these images (from dark to light, from sublime to industrial) into an unforgettable sequence of photographs.

Bravo Richard Avedon!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,254

1/ Text from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art website [Online] Cited 10/10/2025

2/ Text from the YouTube website translated from the French by Google Translate [Online] Cited 23/09/2025

3/ Nathalie Dassa. “Richard Avedon: The Living Forces of the American West,” on the Blind Magazine website, May 12, 2025 [Online] Cited 22/09/2025

4/ Karen Strike. “Before And After: Polaroids then Magic from Richard Avedon, In the American West,” on the Flashbak website June 9, 2025 [Online] Cited 10/10/2025

5/ Clément Chéroux quoted in Christina Cacouris. “Richard Avedon’s Rugged American West Comes to Paris,” on the Aperture website, June 26, 2025 [Online] Cited 23/09/2025

6/ Justine Grosset. “Richard Avedon, In the American West,” on the Phototrend website May 5, 2025 [Online] Cited 10/10/2025

7/ Nathalie Dassa, op.cit.,

8/ Holding a mirror up to their reflection, i.e. to hold something up to scrutiny, to reveal an unpleasant truth, or to show something for what it truly is, often with the intent of providing insight or understanding.

9/ Nathalie Dassa, op.cit.,

Many thankx to the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I don’t think the West in these portraits is any more accurate than John Wayne’s West.”

Richard Avedon at the exhibition opening in 1985

“Avedon’s most compelling photographs are about performance – his performance as well as his subjects’ – and depend on the engagement of their personalities. For this reason it is difficult to separate the photographer from the man. Indeed it is partly owing to the ineluctable presence of Avedon’s own psychology that his portraits transcend the mainstream of cultural history.”

Anonymous. “Body of Evidence,” on the Frieze website, 06 March 1994 [Online] Cited 23/09/2025

“Listen carefully to the stories of others and they may tell us something of ourselves. The story of any person exists first in the mind of its teller, perpetually renewing itself as, like smoke in wind, it is constantly shaped and reshaped in the flux of daily life. Narratives constructed from various facts, memories and rumours are added to, subtracted from, come together and fall apart in a continuous reassembling of experience and imagination. The human mind is a place where fact meets fiction, where reality and fantasy mingle easily and endlessly with fabrication, half-truths and invention. As they say, looking at something is no guarantee you will actually see it.”

Glenn Busch from A Man Holds A Fish 2024

Richard Avedon – In the American West

To mark the 40th anniversary of Richard Avedon’s iconic work, In The American West, the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson presents, from April 30 to October 12, 2025, in collaboration with the Richard Avedon Foundation, an exceptional exhibition entirely dedicated to this iconic series.

Between 1979 and 1984, at the request of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas, Richard Avedon traveled the American West and photographed more than 1,000 of its inhabitants. For five years, Avedon photographed miners, drovers, showmen, vendors, and vagabonds, alone or in small groups, in front of his view camera against a white background that enhanced their features, postures, and expressions.

He thus created a striking portrait of this region and its residents, a departure from traditional representations and glorifications of the myth of the American West. The sheer power of the 103 works that make up the final series and the book of the same name make In The American West a pivotal moment in Avedon’s work and a major milestone in the history of photographic portraiture.

The exhibition presented at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson from April 30 to October 12, 2025, displays for the very first time in Europe all the images that appear in the original work, accompanied by previously unpublished documents.

Text from the YouTube website translated from the French by Google Translate [Online] Cited 23/09/2025

Richard Avedon photographing for In The American West

“We have some testimonies about the way that Avedon was working, and we know that he was not behind his camera, he was standing next to it. He had a strong connection with his subjects, mimicking their position, and asking them to respond to a very small gesture by showing himself moving in one direction or another, and I think a lot of the work is in this relationship that he was establishing with the subject. Photographic literature usually focuses on the framing, the composition, but for me, this kind of interaction he was able to develop with the subject is where the work is, where he’s transforming the people that he met into a Richard Avedon photograph.”

Clément Chéroux quoted in Christina Cacouris. “Richard Avedon’s Rugged American West Comes to Paris,” on the Aperture website, June 26, 2025 [Online] Cited 23/09/2025

Installation view of the exhibition Richard Avedon ‘In the American West‘ at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, April – October 2025

“The hanging follows the book, from the first to the last image,” explains Clément Chéroux. “The blank pages are represented on the wall by a gap equivalent to the width of a frame, like a half-space. We have thus reproduced the rhythm of someone leafing through the book. We can see through this that Richard Avedon and Marvin Israel (1924-1984), artistic director, have constructed the rhythm of these images in a very precise manner.”

Nathalie Dassa. “Richard Avedon: The Living Forces of the American West,” on the Blind Magazine website, May 12, 2025 [Online] Cited 22/09/2025

“Here, the works are displayed throughout the building in classic fashion – in a single line – and in unusually small formats (40 × 50 centimetres). “These are the reference prints, made by the photographer at the time, to produce the prints for his book and the enlargements shown in his exhibitions,” explained Clément Chéroux, the foundation’s director. These prints were not intended for exhibition, but nonetheless their remarkable quality allows the public − for the first time in Europe − to discover this exceptional work in its entirety.”

Claire Guillot. “Richard Avedon’s photographs of the American West at Paris’s Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson,” on the Le Monde website, August 13, 2025 [Online] Cited 23/09/2025

Installation views of the exhibition Richard Avedon ‘In the American West‘ at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, April – October 2025

To mark the 40th anniversary of Richard Avedon’s iconic work In the American West, the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, in collaboration with the Richard Avedon Foundation, presents an exclusive exhibition focused on this emblematic series.

Between 1979 and 1984, commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas, Richard Avedon traveled across the American West to photograph over 1,000 of its inhabitants. For five years, Avedon photographed miners, herdsmen, showmen, salesmen and transient people, amongst others with rich histories, alone or in small groups, before his camera, against a white background that enhanced their features, postures and expressions, for a striking portrait of the territory and its residents, in stark contrast to traditional depictions and glorifications of the legend of the American West. The force of the 103 works that compose the book makes In the American West a pivotal event in Avedon’s career, and a milestone in the history of photographic portraits.

For the first time in Europe, the exhibition at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson presents the whole series of images included in the original publication, while also showcasing the stages of its production and reception. The exhibition includes a full selection of engravers prints, which served as reference materials for both the exhibition and the 1985 book, as well as previously unpublished documents, such as preparatory Polaroids, test prints annotated by the photographer, and correspondence between the artist and his models.

To mark this anniversary, Abrams, the book’s original publisher, is reissuing the long out-of-print book.

Richard Avedon short biography

Richard Avedon was born to parents of Russian Jewish heritage in New York City. As a boy, he learned photography, joining the YMHA Camera Club at the age of twelve. Avedon joined the armed forces in 1942 during World War II, serving as Photographer’s Mate Second Class in the Merchant Marine. Making identification portraits of the crewmen with his Rolleiflex twin lens camera – a gift from his father – Avedon advanced his technical knowledge of the medium and began to develop a dynamic style. After two years of service he left the Merchant Marine to work as a photographer, making fashion images and studying with art director Alexey Brodovitch at the Design Laboratory of the New School for Social Research.

In 1945, Avedon set up his own studio and worked as a freelance photographer for various magazines. He quickly became the preeminent photographer used by Harper’s Bazaar.

From the beginning, Avedon made portraits for editorial publication as well: in the pages of Harper’s Bazaar, in Theater Arts, and in Life and Look magazines. From the outset, he was fascinated by photography’s capacity for suggesting the personality and evoking the life of his subjects. Only rarely did he idealize people; instead, he presented the face as a kind of landscape, with total clarity.

Avedon continued to make portraiture and fashion photography for magazine publications throughout his career. After parting ways with Harper’s Bazaar in 1965, he began a long-term relationship with Vogue that continued through 1988. In later years, he established formidable creative partnerships with the French publication Egoiste, and with The New Yorker. In the pages of these periodicals, Avedon reinvigorated his formalist style, investing his imagery with dynamism and theatricality. In addition, he supported his studio by making innovative advertising work for print and broadcast – defining the look of brands like Calvin Klein, Versace, and Revlon.

As his reputation grew and his signature aesthetic evolved, Avedon remained dedicated to extended portraiture projects as a means for exploring cultural, political, and personal concerns. In 1963-1964, he examined the civil rights movement in the American South. During the Vietnam War, he photographed students, countercultural artists and activists, and victims of the war, both in the United States and in Vietnam. In 1976, on a commission for Rolling Stone magazine, he produced The Family, a composite portrait of the American power elite at the time of the country’s Bicentennial election.

In 1985, Avedon created his magnum opus – In the American West. He portrayed members of the working class: butchers, coal miners, convicts, and waitresses, all photographed with precisionist detail, using the large format camera and plain white backdrop characteristic of his mature style. Despite their apparent minimalism and objectivism, however, Avedon emphasised that these portraits were not to be regarded as simple records of people; rather, he said, “the moment an emotion or a fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion.”

Publication

Richard Avedon’s acclaimed work In the American West was first published in 1985 by American publishing house Abrams. For its 40th anniversary, Abrams is republishing the work in its original format.

Text from the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

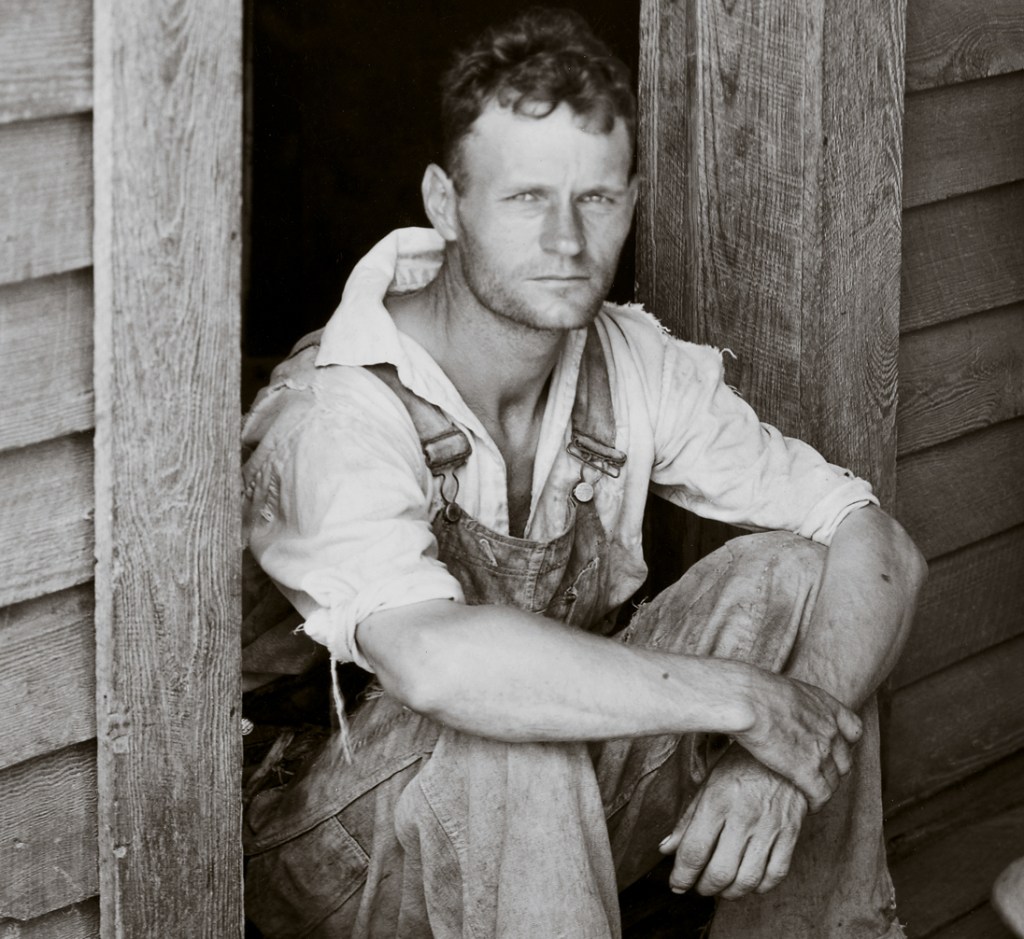

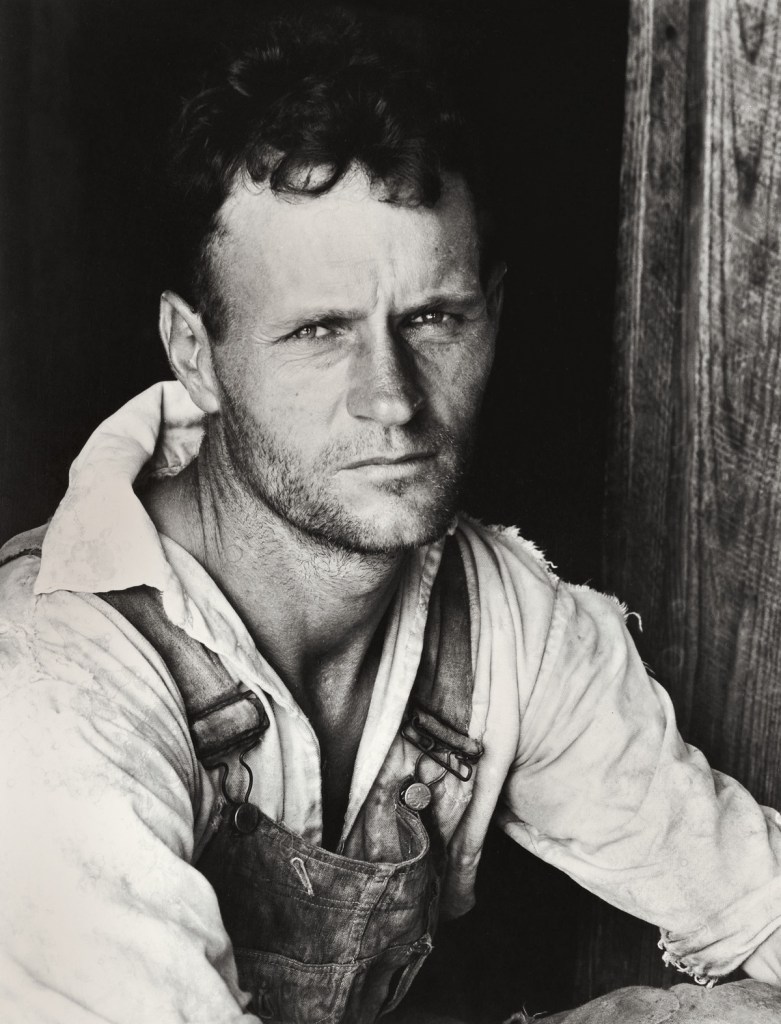

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Roger Tims, Jim Duncan, Leonard Markley, Don Belak, coal miners, Reliance, Wyoming, August 29, 1979

1979

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

“This was the beginning of his emblematic project “In the American West” that took him across 17 US states, where he photographed nearly 1,000 people from 1979 to 1984 and revealed a poor, hardworking America, far removed from the clichés and the myth of the glorious American West. He carried out this series with neither sociological intent nor a concern for objectivity. “This is a fictional West,” he said. “I don’t think the West of these portraits is any more conclusive than the West of John Wayne.””

Claire Guillot. “Richard Avedon’s photographs of the American West at Paris’s Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson,” on the Le Monde website, August 13, 2025 [Online] Cited 23/09/2025

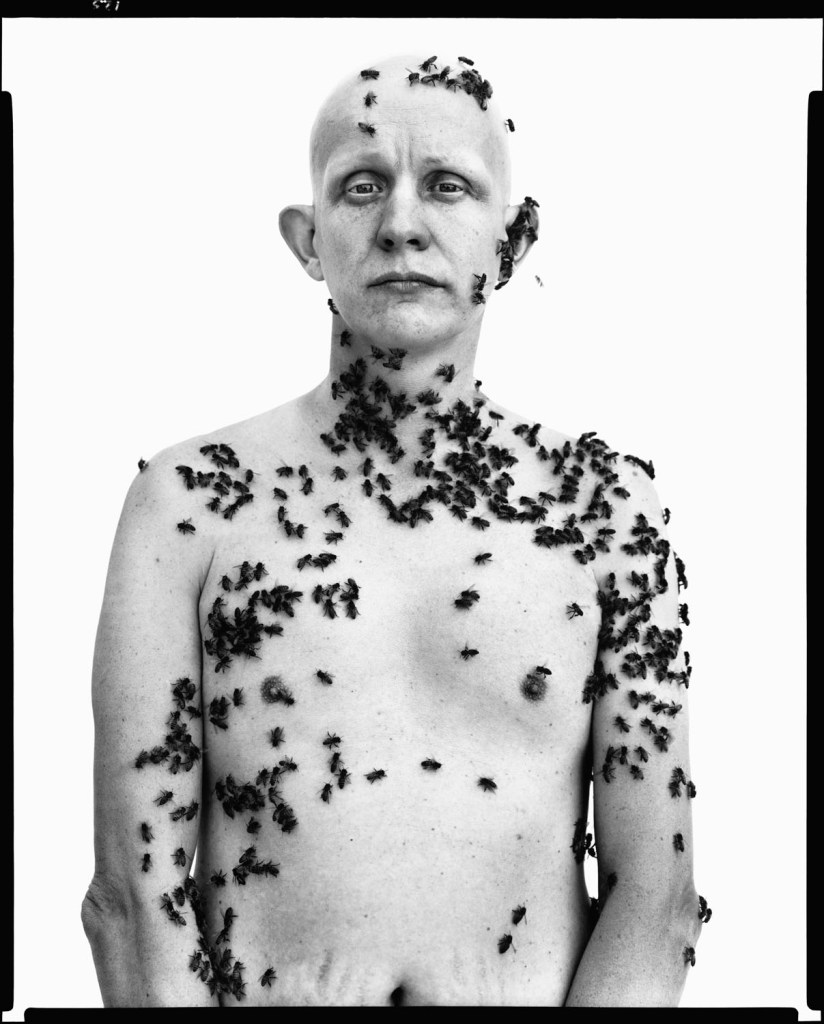

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Ronald Fischer, beekeeper, Davis, California, May 9, 1981

1981

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

“He needed to create disjunctions,” says Clément Chéroux. “The beekeeper remains a great image of the 20th century. After placing an ad, he chose this man suffering from alopecia, who no longer had any hair, no eyebrows. He took him to an entomologist who covered him with queen pheromones to attract bees. Through this staging, he wanted to make the audience understand that nothing is more complex than simplicity.”

Nathalie Dassa. “Richard Avedon: The Living Forces of the American West,” on the Blind Magazine website, May 12, 2025 [Online] Cited 22/09/2025

“The subjective part of the project is clear. And most of the photographs were from encounters where he photographed people he met as they were. He also stated very clearly that a few photographs were set up, and the photograph of the Bee Man is a good example of that. He first published an advertisement in the American Bee Journal to find the type of person he was interested in – we have the advertisement in the exhibition, we found the original magazine where it was published. So, he looked for that person and made some drawings in preparation for the shoot. He clearly had a dream of a specific image that he wanted to realize. And he made clear that he wanted to have this photograph to show the subjective part of the project, that it was not exclusively a documentary project. I think the Bee Man shows us that there isn’t truth on one side and fiction on the other. It’s much more complex.” …

“Just before the Bee Man, we have the coal miners, these very strong dark images and then suddenly you have the white body of Ronald Fisher with all these little bees. We wanted to respect this in the exhibition, the sense that it was not just a collection of twentieth-century photographs of Americans, but it was a group of images, a full sentence.”

Clément Chéroux quoted in Christina Cacouris. “Richard Avedon’s Rugged American West Comes to Paris,” on the Aperture website, June 26, 2025 [Online] Cited 23/09/2025

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

David Beason, shipping clerk, Denver, Colorado, July 25, 1981

1981

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

“The year after [Glenn Busch’s] Working Men was published came fashion photographer Richard Avedon‘s In the American West (New York: Abrams, 1985), the consistent theme of which, as Richard Bolton in Afterimage argues, sees “human experience as manifested in [no]thing but style,” a quality, less sombre, but equally arch, exoticising and stereotyping that is found also in the Small Trades studio series of 1950-51 by Irving Penn.”

James McArdle. “October 8: Prosopography,” on the On This Date In Photography website 08/10/2025 [Online] Cited 08/10/2025

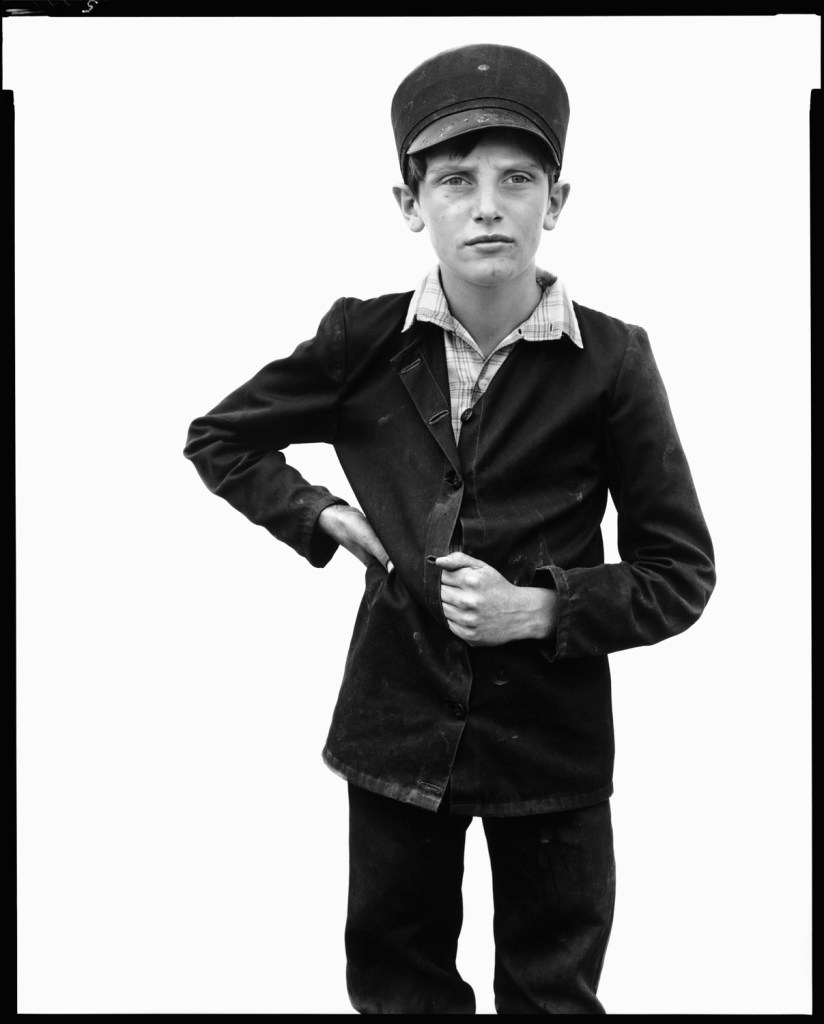

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Jesse Kleinsasser, pig man, Hutterite Colony, Harlowton, Montana, June 23, 1983

1983

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

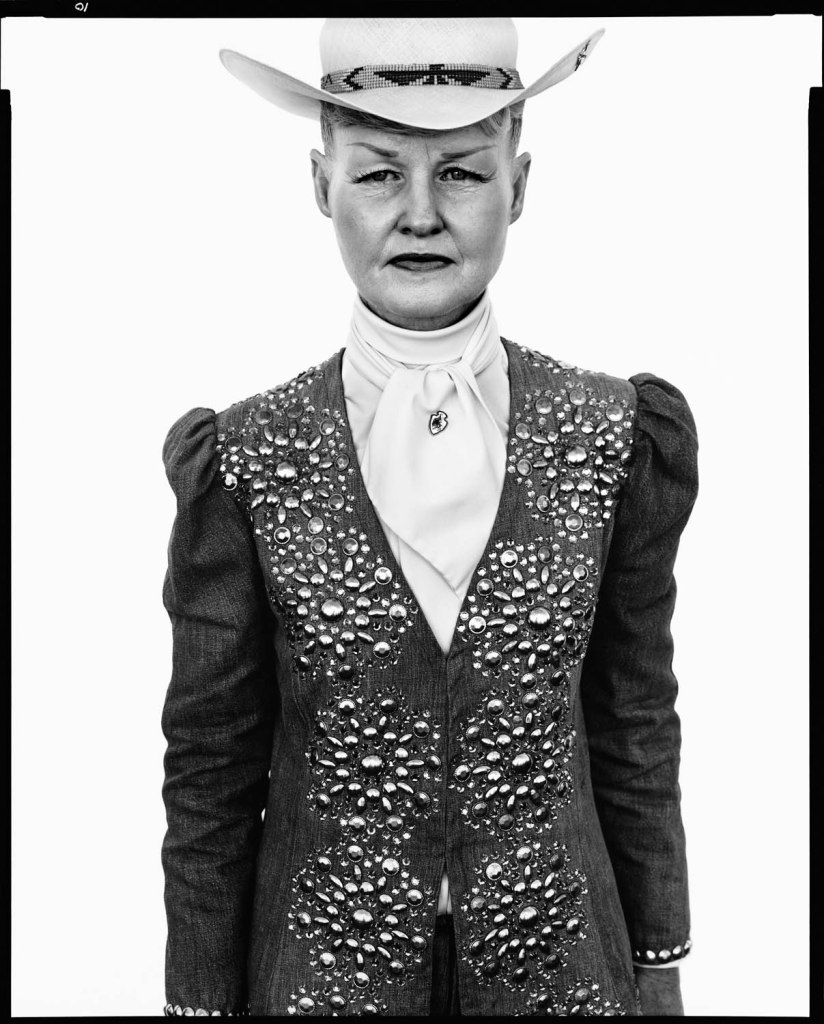

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Ruby Mercer, publicist, Frontier Days, Cheyenne, Wyoming, July 31, 1982

1982

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

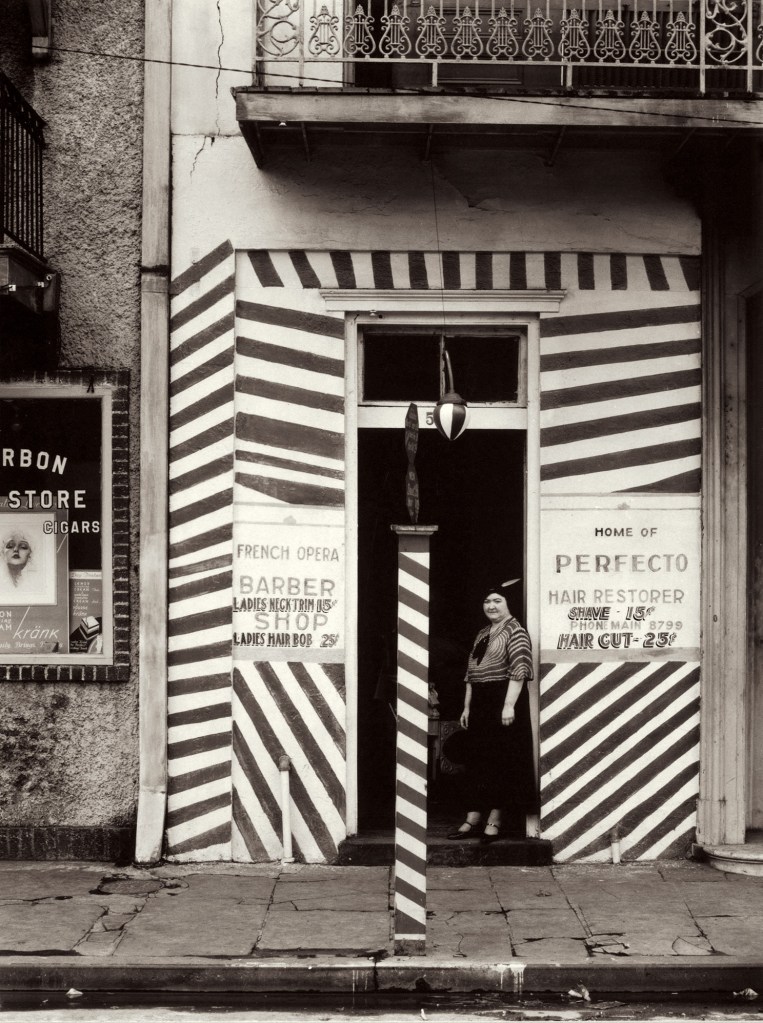

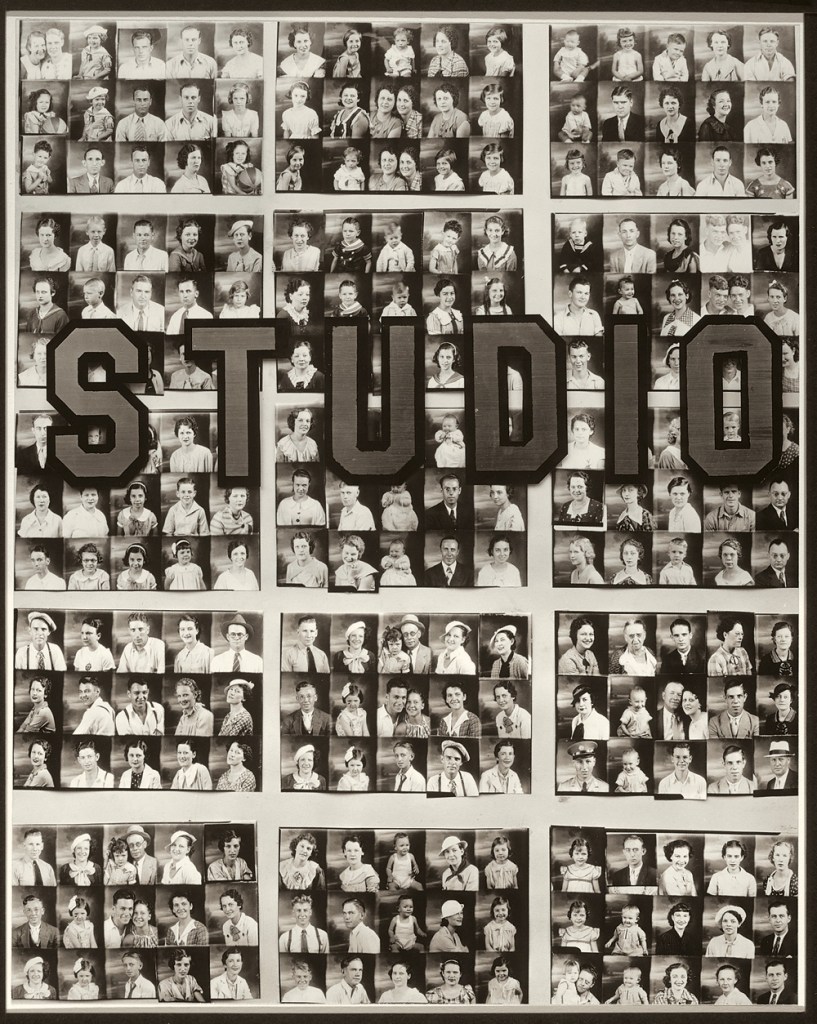

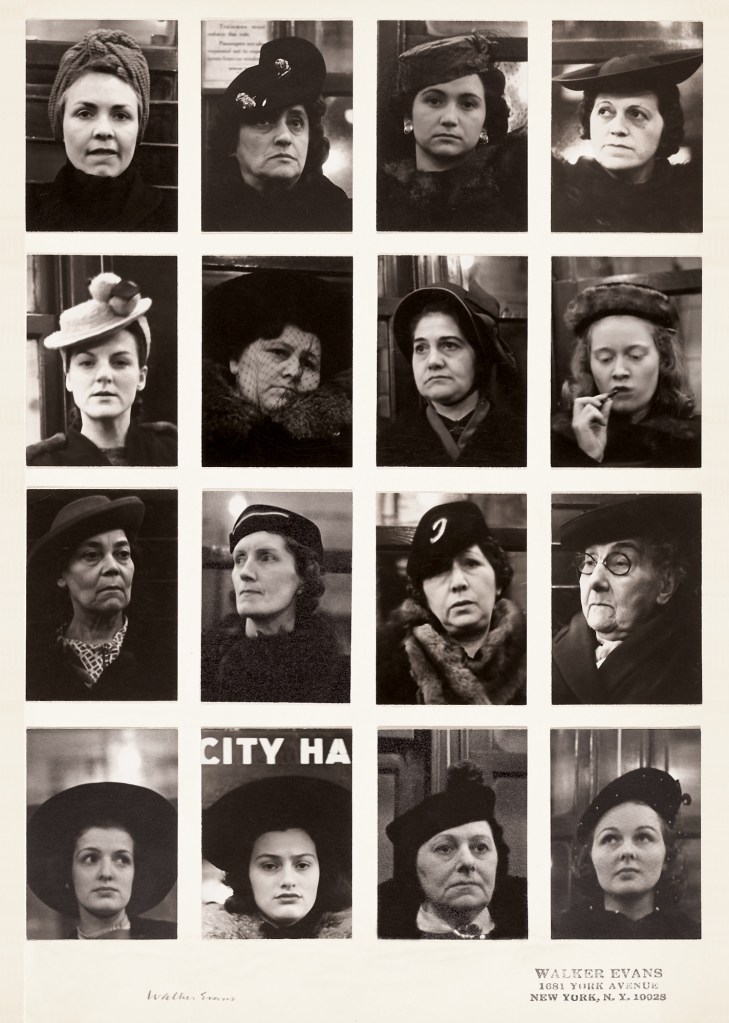

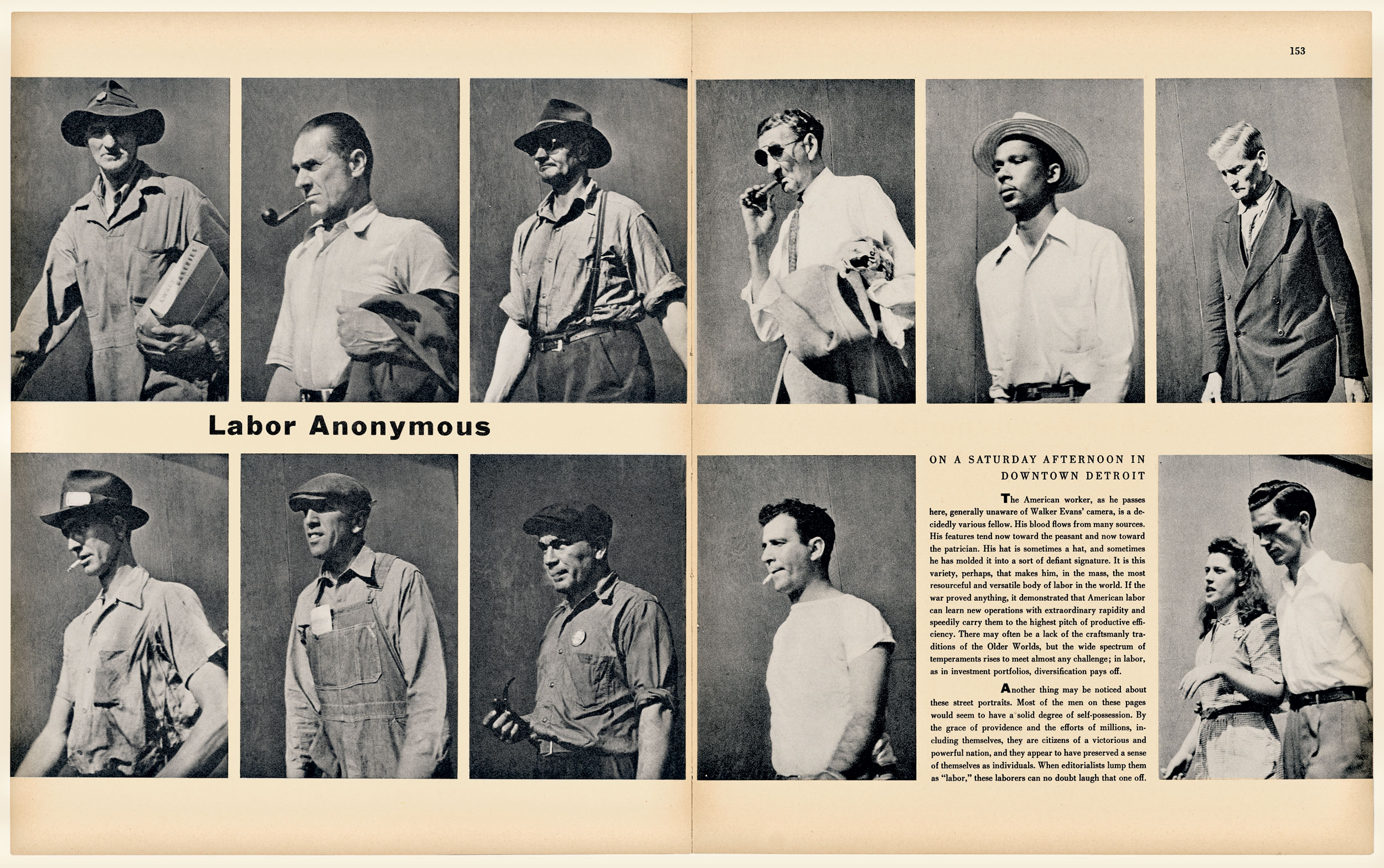

“Avedon was aware of the subjectivity of what he presents. He was also very familiar with art history and pictorial references, such as those of Rembrandt. He made carcasses of sheep and cattle appear like hallucinations among the workers. His photography is therefore no more objective than that of John Wayne’s westerns. And that is what he had been criticised for: representing a sad, unsmiling America, which does not correspond to the one dreamed of. These are the people that Walker Evans and the traveling photographers sought out during the conquest of the West. He demonstrated this paradox. And this is the term Roland Barthes uses for him: the paradox of all great art. Richard Avedon showed his own America, those we do not see, those we pass by without pausing, those who do the work, those who make America work.”

Nathalie Dassa. “Richard Avedon: The Living Forces of the American West,” on the Blind Magazine website, May 12, 2025 [Online] Cited 22/09/2025

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Petra Alvarado, factory worker, on her birthday, El Paso, Texas, April 22, 1982

1982

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

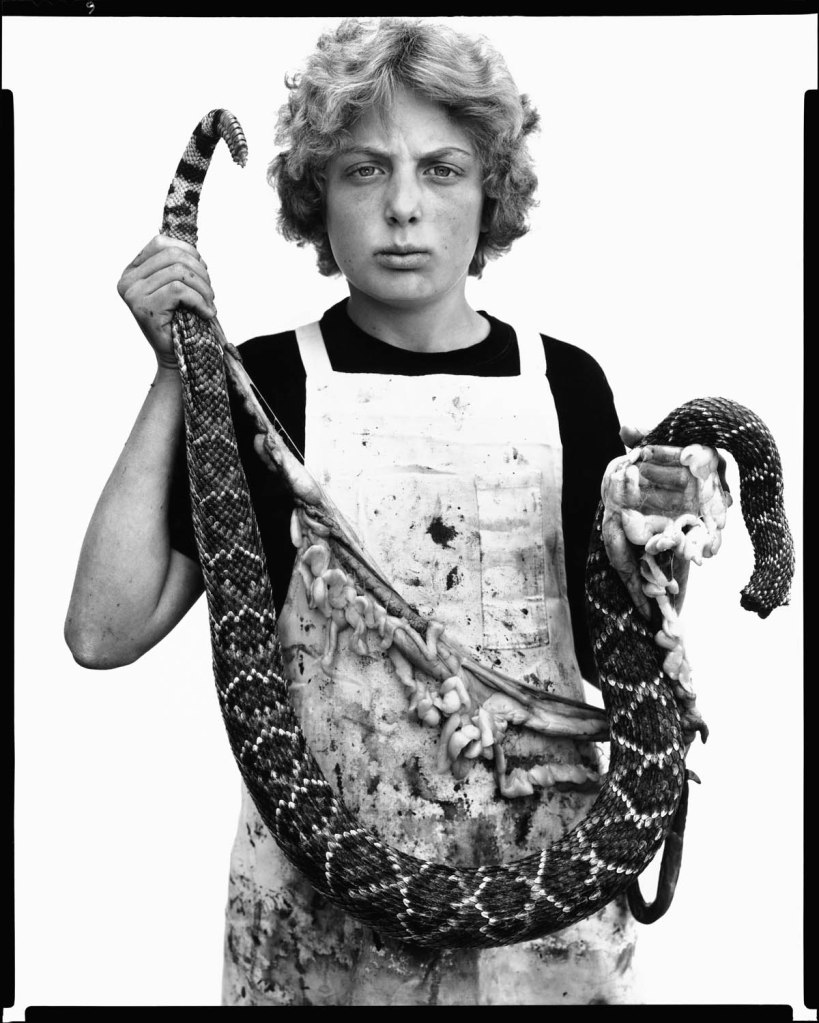

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Boyd Fortin, thirteen year old rattlesnake skinner, Sweetwater, Texas, March 10, 1979

1979

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Avedon took this portrait in 1979 in Texas during the annual snake hunt in the small town of Sweetwater.

The portraits from In the American West may not be romantic images – no pomp and circumstance – but they are dignified. Coal miners, cotton farmers, and cowboys stand tall and proud. Avedon worked quickly, street-casting his subjects alongside his assistant Laura Wilson, setting up white paper backdrops and shooting instinctively. Post-production was another matter entirely: Chéroux’s exhibition showcases the meticulous care that went into each print, with Avedon’s instructions for dodging and burning scrawled across pictures.

Christina Cacouris. “Richard Avedon’s Rugged American West Comes to Paris,” on the Aperture website, June 26, 2025 [Online] Cited 23/09/2025

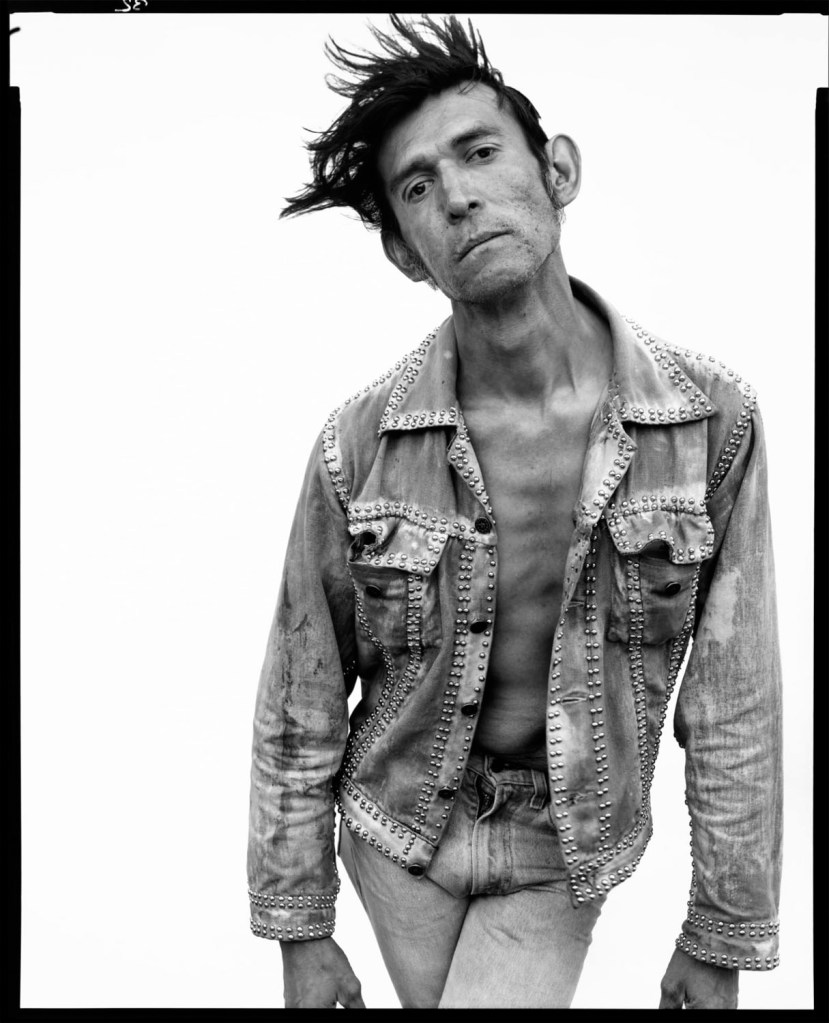

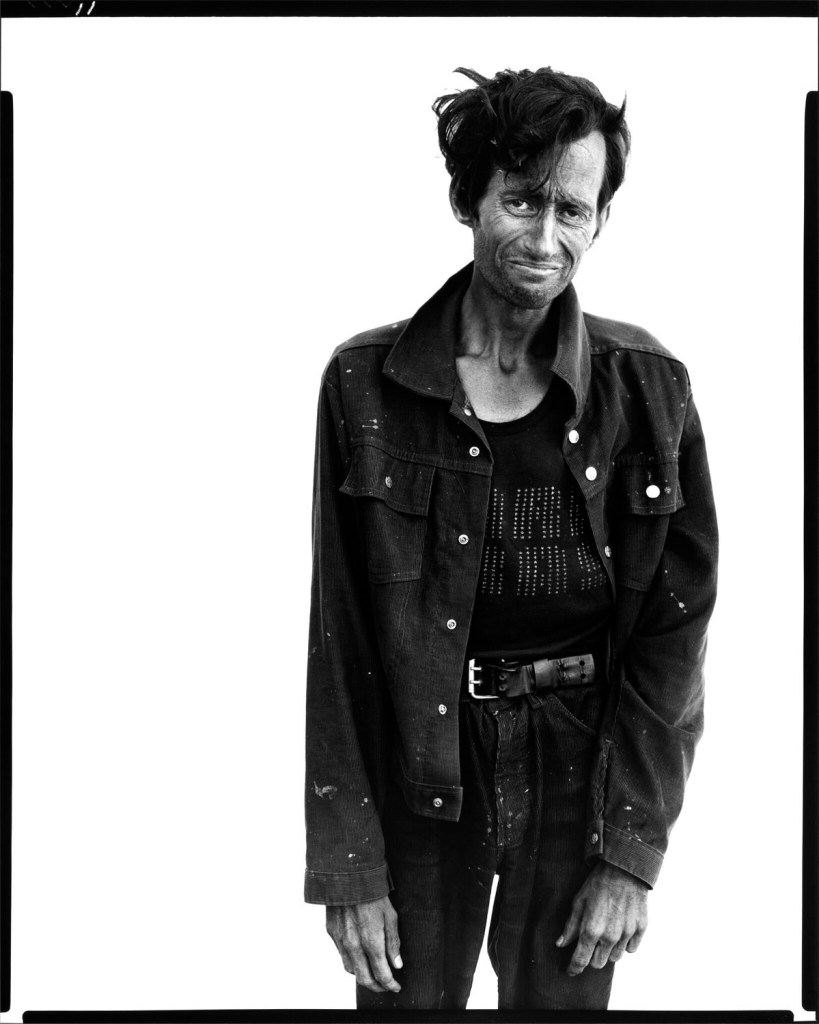

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Richard Garber, drifter, Interstate 15, Provo, Utah, August 20, 1980

1980

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Blue Cloud Wright, slaughterhouse worker, Omaha, Nebraska, August 10, 1979

1979

Gelatin silver print

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Cover of Richard Avedon’s book In The American West

Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

79 rue des Archives

75003 Paris

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday

11am – 7pm

Closed on Mondays

![Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) '[Subway Passengers, New York City]' 1938 Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) '[Subway Passengers, New York City]' 1938](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/walker-evans-subway-passengers-new-york-city-web.jpg)

![Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) 'Untitled [Street scene]' 1950s Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) 'Untitled [Street scene]' 1950s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/walker-evans-untitled-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.