Exhibition dates: 10th March – 30th November, 2020

Curator: Jeff L. Rosenheim, Joyce Frank Menschel Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Underwater Swimmer, Esztergom, Hungary

1917

Gelatin silver print

1 1/2 in. × 2 in. (3.8 × 5.1cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© 2020 Estate of André Kertész/Higher Pictures

This tiny but iconic masterpiece of twentieth-century photography is the second earliest work in the exhibition, and a gem in the Tenenbaum and Lee collection. Made while André Kertész was convalescing from a gunshot wound received while serving in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I, it prefigures by some fifteen years his renowned mirror distortions produced in Paris. Displaying both Cubist and Surrealist influences, the photograph reveals the artist’s commitment to the spontaneous yet analytic observation of fleeting commonplace occurrences – one of the essential and most idiosyncratic qualities of the medium.

It’s a mystery

There are some eclectic photographs in this posting, many of which have remained un/seen to me before.

I have never seen the above version of Kertész’s Underwater Swimmer, Esztergom, Hungary (1917), with wall, decoration and water flowing into the pool at left. The usual image crops these features out, focusing on the distortion of the body in the water, and the lengthening of the figure diagonally across the picture frame. That both images are from the same negative can be affirmed if one looks at the patterning of the water. Even as the exhibition of Kertész’s work at Jeu de Paume at the Château de Tours that I saw last year stated that their version was a contact original… this is not possible unless the image has been cropped.

Other images by Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Outerbridge Jr., Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, Pierre Dubreuil, Ilse Bing, Bill Brandt, Dora Maar, Joseph Cornell, Nan Goldin, Laurie Simmons, Robert Gober, Rachel Whiteread, Zanele Muholi have eluded my consciousness until now.

What I can say after viewing them is this.

I am forever amazed at how deep the spirit, and the medium, of photography is… if you give the photograph a chance. A friend asked me the other day whether photographs had any meaning anymore, as people glance for a nano-second at images on Instagram, and pass on. We live in a world of instant gratification was my answer to him. But the choice is yours if you take / time with a photograph, if it possesses the POSSIBILITY of a meditation from its being. If it intrigues or excites, or stimulates, makes you reflect, cry – that is when the photographs pre/essence, its embedded spirit, can make us attest to the experience of its will, its language, its desire. In our presence.

The more I learn about photography, the less I find I know. The lake (archive) is deep – full of serendipity, full of memories, stagings, concepts and realities. Full of nuances and light, crevices and dark passages. To understand photography is a life-long study. To an inquiring mind, even then, you may only – scratch the surface to reveal – a sort of epiphany, a revelation, unknown to others. Every viewing is unique, every interpretation different, every context unknowable (possible).

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. When Minor White was asked, what about photography when he dies? When he is no longer there to influence it? And he simply says – photography will do what it wants to do. This is a magnificent statement, and it shows an egoless freedom on Minor White’s part. It is profound knowledge about photography, about its freedom to change.

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

This exhibition will celebrate the remarkable ascendancy of photography in the last century, and Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee’s magnificent promised gift of over sixty extraordinary photographs in honour of The Met’s 150th anniversary in 2020. The exhibition will include masterpieces by the medium’s greatest practitioners, including works by Paul Strand, Dora Maar, Man Ray, and László Moholy-Nagy; Edward Weston, Walker Evans, and Joseph Cornell; Diane Arbus, Andy Warhol, Sigmar Polke, and Cindy Sherman.

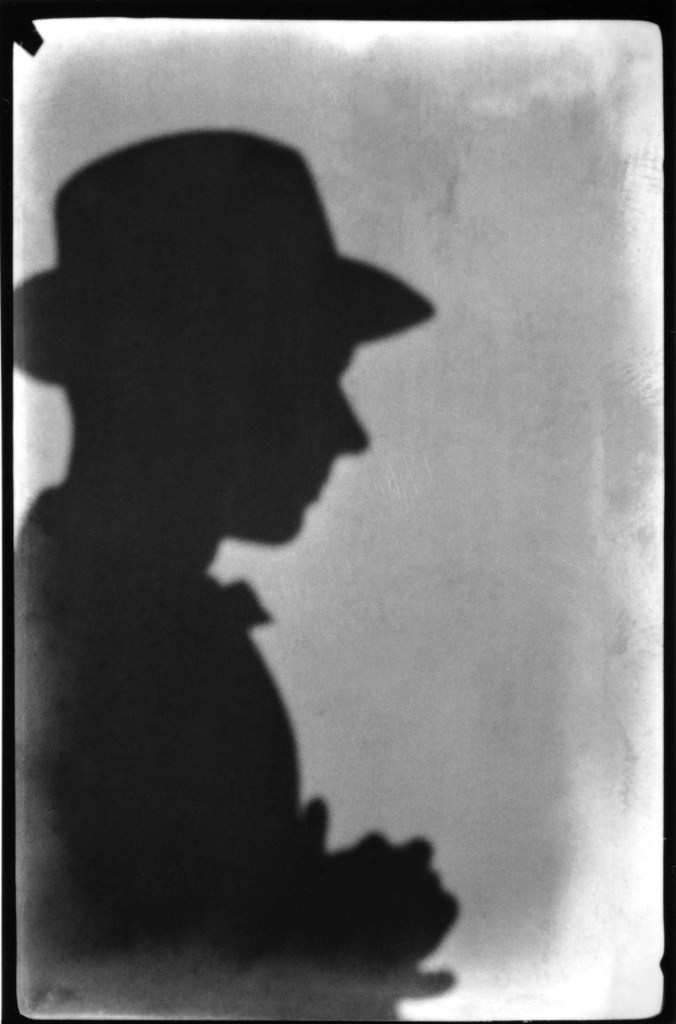

The collection is particularly notable for its breadth and depth of works by women artists, its sustained interest in the nude, and its focus on artists’ beginnings. Strand’s 1916 view from the viaduct confirms his break with the Pictorialist past and establishes the artist’s way forward as a cutting-edge modernist; Walker Evans’s shadow self-portraits from 1927 mark the first inkling of a young writer’s commitment to visual culture; and Cindy Sherman’s intimate nine-part portrait series from 1976 predates her renowned series of “film stills” and confirms her striking ambition and stunning mastery of the medium at the age of twenty-two.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe

1918

Platinum print

9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.1 × 19.1cm)

Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This photograph marks the beginning of the romantic relationship between Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe, which transformed each of their lives and the story of American art. The two met when Stieglitz included O’Keeffe, a then-unknown painter, in her first group show at his gallery 291 in May 1916. A year later, O’Keeffe had her first solo show at the gallery and exhibited her abstract charcoal No. 15 Special, seen in the background here. In the coming months and years, O’Keeffe collaborated with Stieglitz on some three hundred portrait studies. In its physical scope, primal sensuality, and psychological power, Stieglitz’s serial portrait of O’Keeffe has no equal in American art.

Paul Outerbridge Jr. (American, 1896-1958)

Telephone

1922

Platinum print

4 1/2 × 3 3/8 in. (11.4 × 8.5cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A well-paid advertising photographer working in New York in the 1930s, Paul Outerbridge Jr. was trained as a painter and set designer. Highly influenced by Cubism, he was a devoted advocate of the platinum-print process, which he used to create nearly abstract still lifes of commonplace subjects such as cracker boxes, wine glasses, and men’s collars. With their extended mid-tones and velvety blacks, platinum papers were relatively expensive and primarily used by fine-art photographers like Paul Strand, Edward Steichen, and Alfred Stieglitz. This modernist study of a Western Electric “candlestick” telephone attests to Outerbridge’s talent for transforming banal, utilitarian objects into small, but powerful sculptures with formal rigour and startling beauty.

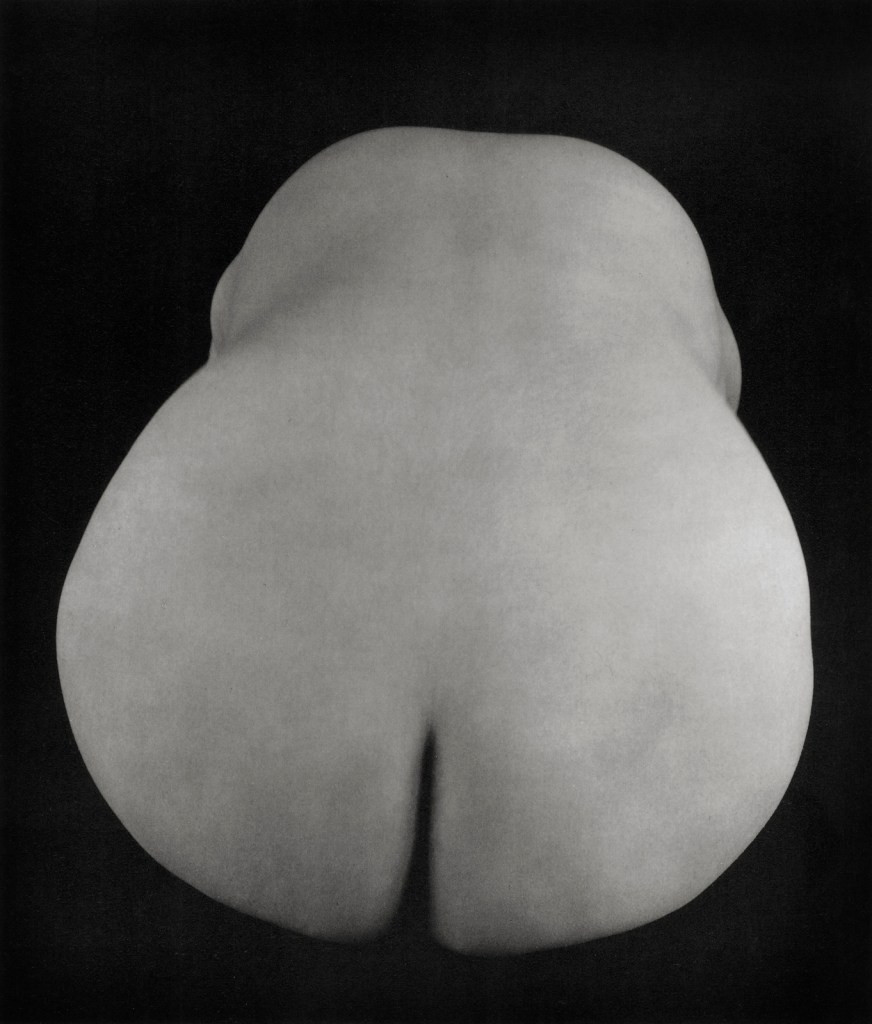

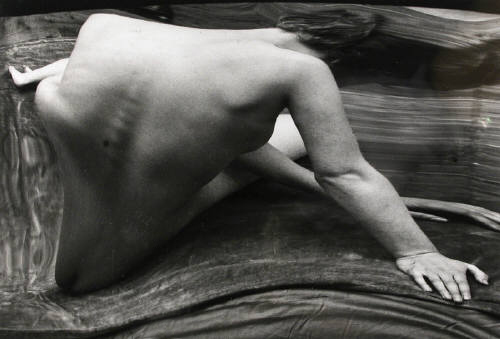

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Nude

1925, printed 1930s

Gelatin silver print

8 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (21.6 × 19cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Edward Weston moved from Los Angeles to Mexico City in 1923 with Tina Modotti, an Italian actress and nascent photographer. They were each influenced by, and in turn helped shape, the larger community of artists among whom they lived and worked, which included Diego Rivera, Jean Charlot, and many other members of the Mexican Renaissance. In fall 1925 Weston made a remarkable series of nudes of the art critic, journalist, and historian Anita Brenner. Depicting her body as a pear-like shape floating in a dark void, the photographs evoke the hermetic simplicity of a sculpture by Constantin Brancusi. Brenner’s form becomes elemental, female and male, embryonic, tightly furled but ready to blossom.

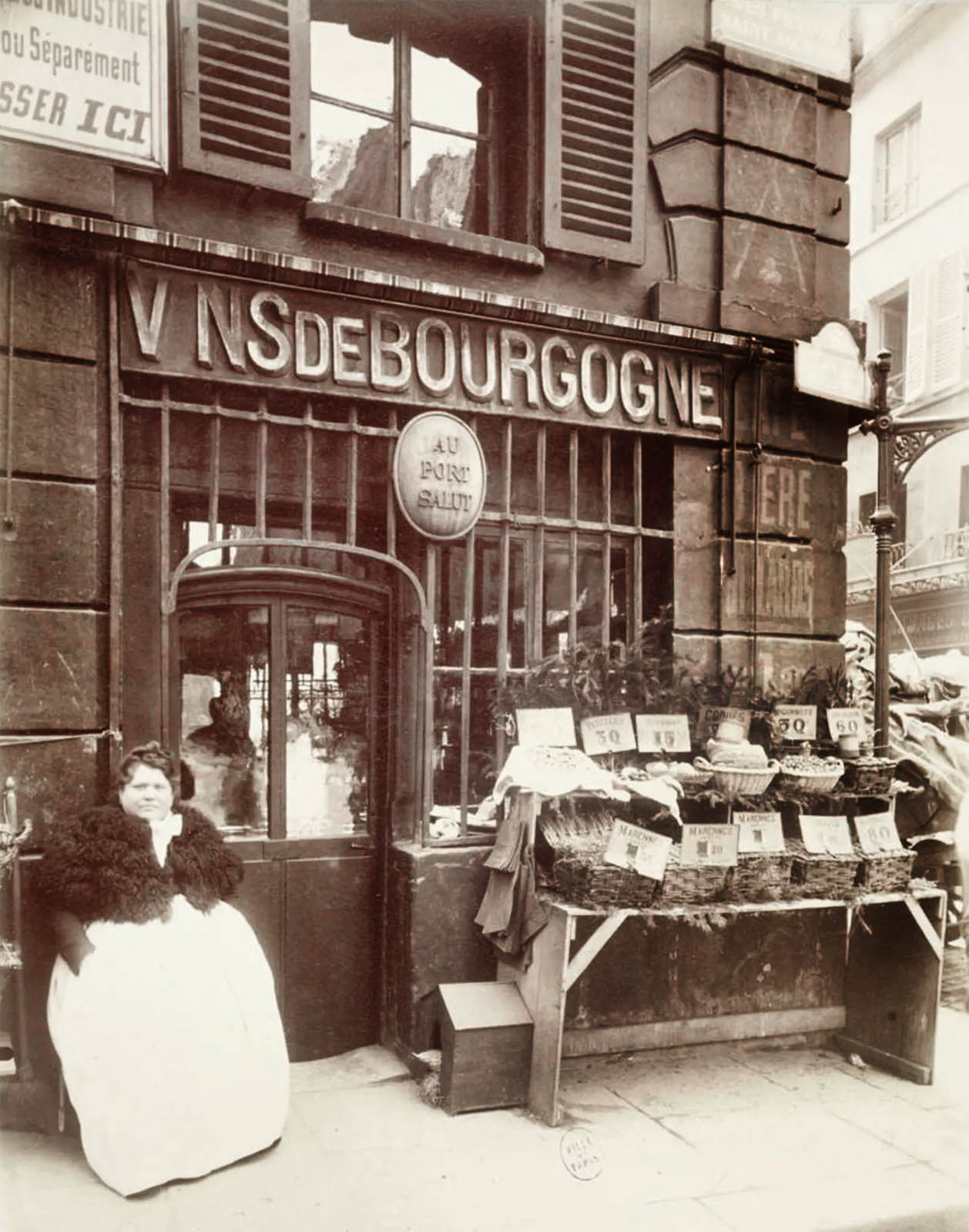

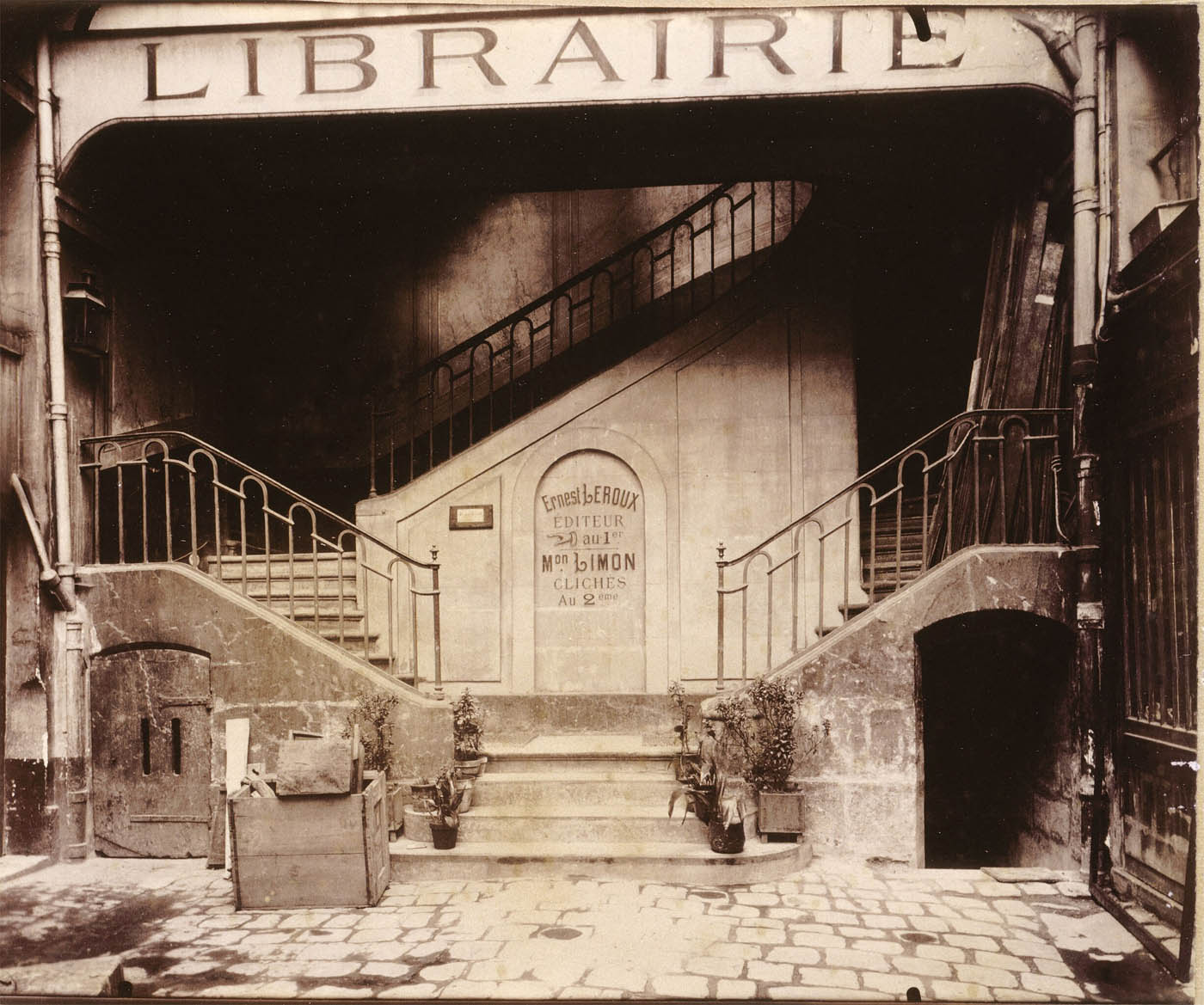

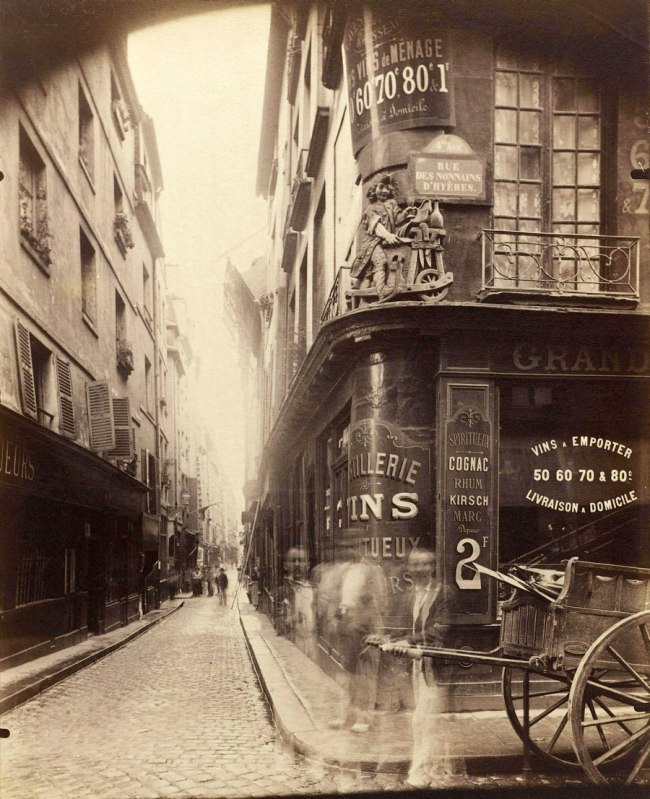

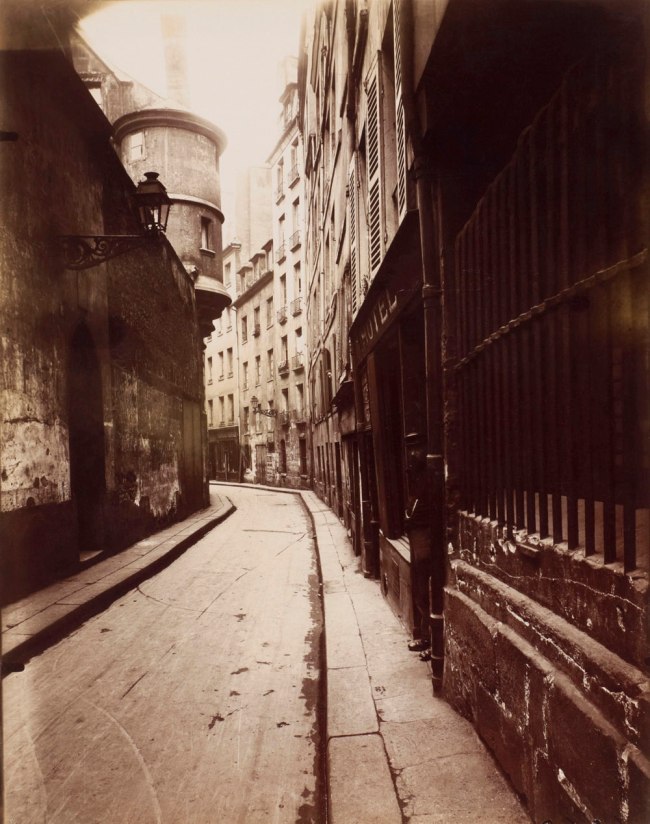

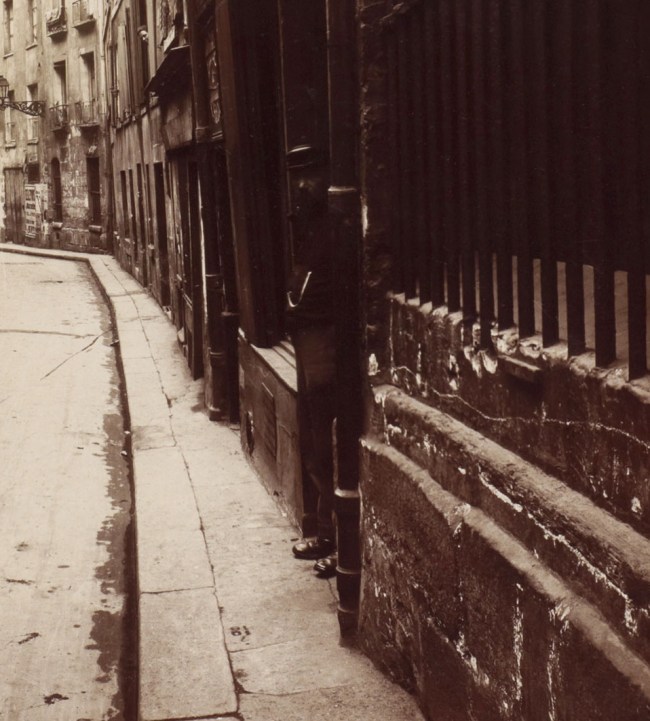

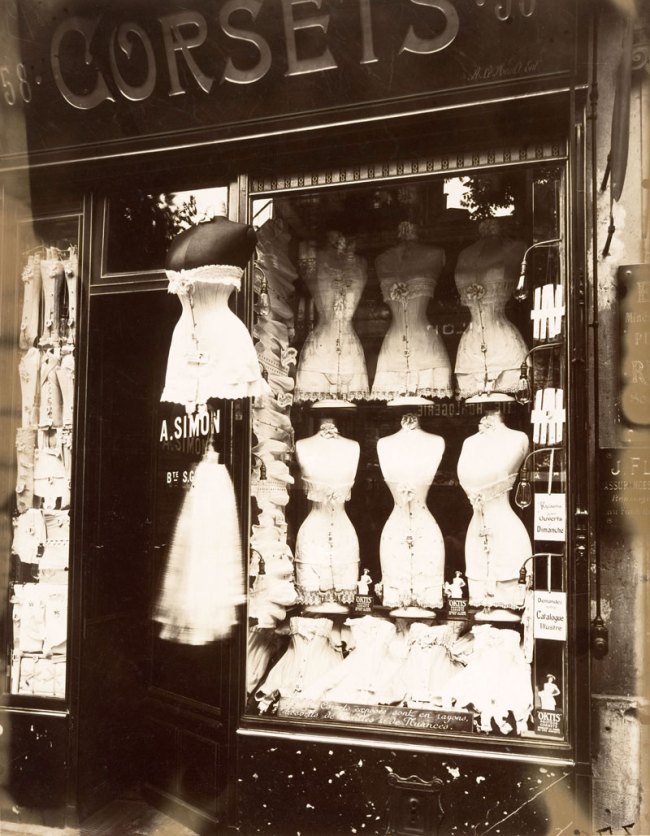

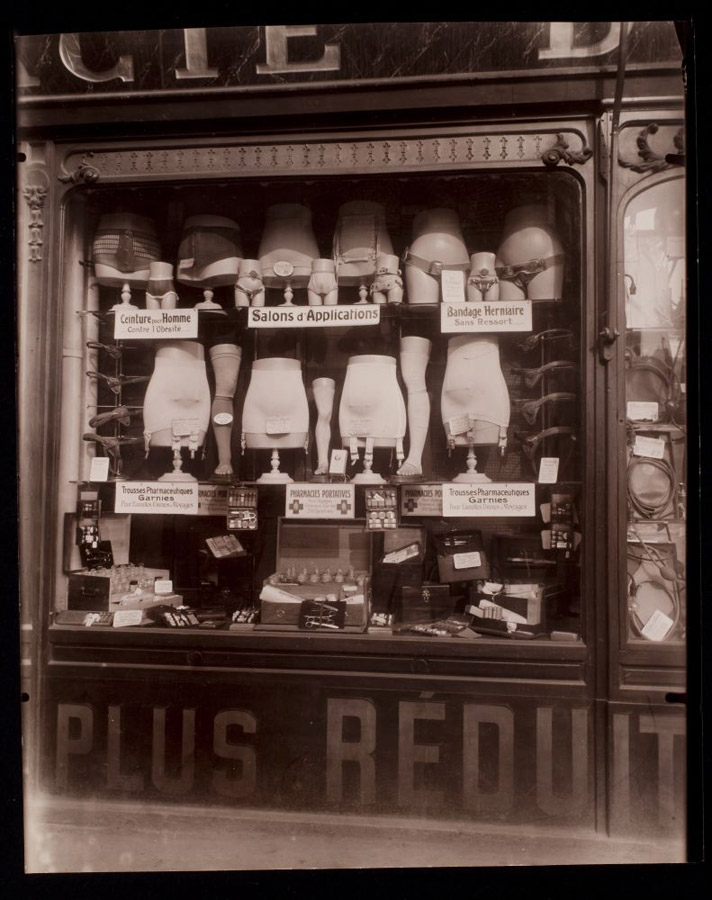

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Boulevard de Strasbourg

1926

Gelatin silver print

8 7/8 in. × 7 in. (22.5 × 17.8cm)

Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Eugène Atget became the darling of the French Surrealists in the mid-1920s courtesy of Man Ray, his neighbour in Paris, who admired the older artist’s seemingly straight forward documentation of the city. Another American photographer, Walker Evans, also credited Atget with inspiring his earliest experiments with the camera. A talented writer, Evans penned a famous critique of his progenitor in 1930: “[Atget’s] general note is a lyrical understanding of the street, trained observation of it, special feeling for patina, eye for revealing detail, over all of which is thrown a poetry which is not ‘the poetry of the street’ or ‘the poetry of Paris,’ but the projection of Atget’s person.”

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Self-portrait, Juan-les-Pins, France, January 1927

1927

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Shadow, Self-Portrait (Right Profile, Wearing Hat), Juan-les-Pins, France, January 1927

1927

Film negative

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

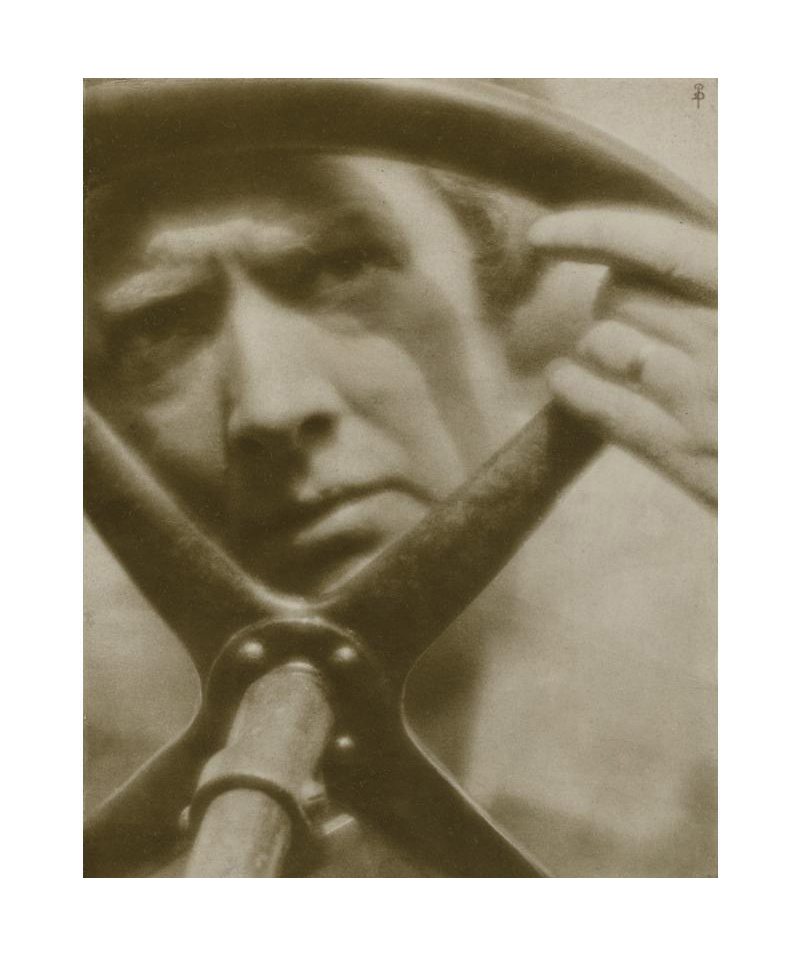

Pierre Dubreuil (French, 1872-1944)

The Woman Driver

1928

Bromoil print

9 7/16 × 7 5/8 in. (24 × 19.3cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Like many other European and American photographers, Pierre Dubreuil was indifferent to the industrialisation of photography that followed the invention and immediate global success of the Kodak camera in the late 1880s. A wealthy member of an international community of photographers loosely known as Pictorialists, he spurned most aspects of modernism. Instead, he advocated painterly effects such as those offered by the bromoil printing process seen here. What makes this photograph exceptional, however, is the modern subject and the work’s title, The Woman Driver. Dubreuil’s wife, Josephine Vanassche, grasps the steering wheel of their open-air car and stares straight ahead, ignoring the attention of her conservative husband and his intrusive camera.

Florence Henri (French, born America 1893-1982)

Windows

1929

Gelatin silver print

14 1/2 × 10 1/4 in. (36.8 × 26cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A peripatetic French American painter and photographer, Florence Henri studied with László Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus in Germany in summer 1927. Impressed by her natural talent, he wrote a glowing commentary on the artist for a small Amsterdam journal: “With Florence Henri’s photos, photographic practice enters a new phase, the scope of which would have been unimaginable before today… Reflections and spatial relationships, superposition and intersections are just some of the areas explored from a totally new perspective and viewpoint.” Despite the high regard for her paintings and photographs in the 1920s, Henri remains largely under appreciated.

![Ilse Bing (German, 1899-1998) '[Rue de Valois, Paris]' 1932 Ilse Bing (German, 1899-1998) '[Rue de Valois, Paris]' 1932](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ilse-bing-rue-de-valois-paris-1932.jpg?w=804)

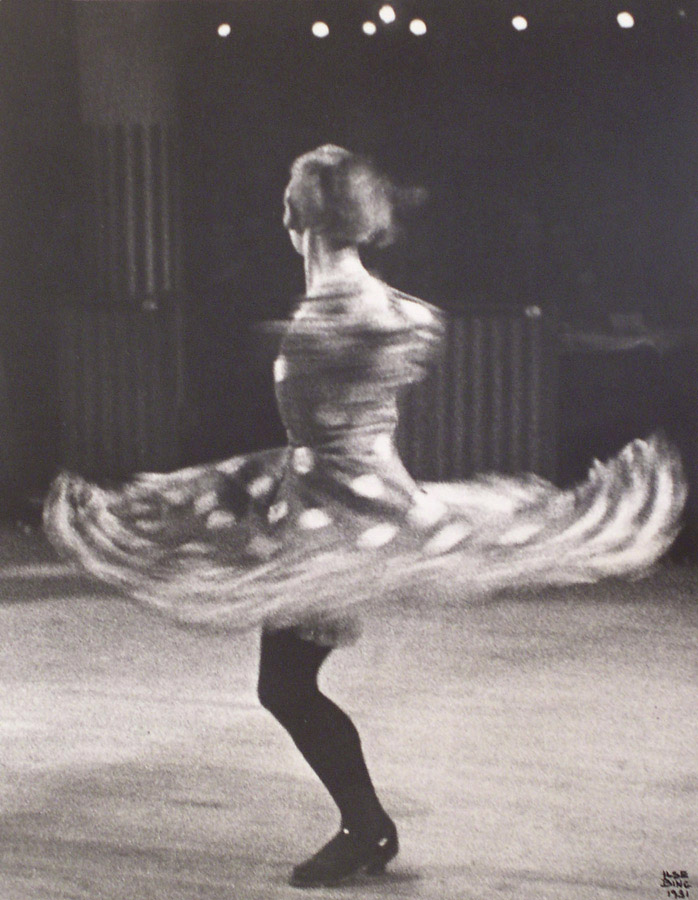

Ilse Bing (German, 1899-1998)

[Rue de Valois, Paris]

1932

Gelatin silver print

11 1/8 × 8 3/4 in. (28.3 × 22.2cm)

Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing trained as an art historian in Germany and learned photography in 1928 to make illustrations for her dissertation on neoclassical architecture. In 1930 she moved to Paris, supporting herself as a freelance photographer for French and German newspapers and fashion magazines. Known in the early 1930s as the “Queen of the Leica” due to her mastery of the handheld 35 mm camera, Bing found the old cobblestone streets of Paris a rich subject to explore, often from eccentric perspectives as seen here. She moved to New York in 1941 after the German occupation of Paris and remained here until her death at age ninety-eight.

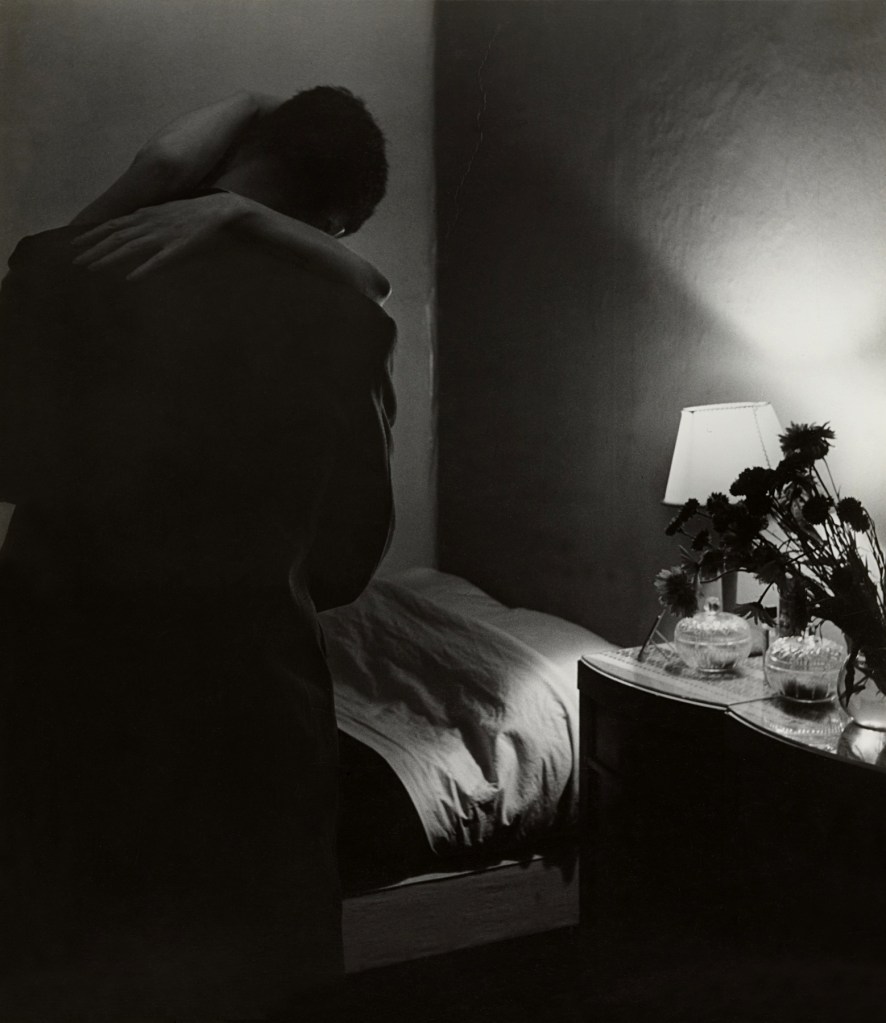

Bill Brandt (British, 1904-1983)

Soho Bedroom

1932

Gelatin silver print

8 7/16 × 7 5/16 in. (21.4 × 18.5cm)

Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bill Brandt challenged the standard tenets of documentary practice by frequently staging scenes for the camera and recruiting family and friends as models. In this intimate study of a couple embracing, the male figure is believed to be either a friend or the artist’s younger brother; the female figure is an acquaintance, “Bird,” known for her beautiful hands. The photograph appears with a different title, Top Floor, along with sixty-three others in Brandt’s second book, A Night in London (1938). After the book’s publication, Brandt changed the work’s title to Soho Bedroom to reference London’s notorious Red Light district and add a hint of salaciousness to the kiss.

![Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997) '[Woman and Child in Window, Barcelona]' 1932-1934 Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997) '[Woman and Child in Window, Barcelona]' 1932-1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/dora-maar-woman-and-child-in-window-barcelona.jpg?w=768)

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

[Woman and Child in Window, Barcelona]

1932-1934

Gelatin silver print

11 1/8 × 8 3/8 in. (28.2 × 21.2cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

When Dora Maar first traveled to Barcelona in 1932 to record the effects of the global economic crisis, she was twenty-five and still finding her footing as a photographer. To sustain her practice, she opened a joint studio with the film designer Pierre Kéfer. Working out of his parents’ villa in a Parisian suburb, he and Maar produced mostly commercial photographs for fashion and advertising – projects that funded Maar’s travel to Spain. With an empathetic eye, she documents a mother and her child peering out of a makeshift shelter. Adapting an avant-garde strategy, she chose a lateral angle to monumentalise her subjects.

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Nude

1934

Gelatin silver print

3 5/8 in. (9.2cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

The nude as a subject for the camera would occupy Edward Weston’s attention for four decades, and it is a defining characteristic of his achievement and legacy. This physically small but forceful, closely cropped photograph is a study of the writer Charis Wilson. Although presented headless and legless, Wilson tightly crosses her arms in a bold power pose. Weston was so stunned by Wilson when they first met that he ceased writing in his diary the day after he made this photograph: “April 22 [1934], a day to always remember. I knew now what was coming; eyes don’t lie and she wore no mask… I was lost and have been ever since.” Wilson and Weston immediately moved in together and married five years later.

The exhibition Photography’s Last Century: The Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection celebrates the remarkable ascendancy of photography in the last hundred years through the magnificent promised gift to The Met of more than 60 extraordinary photographs from Museum Trustee Ann Tenenbaum and her husband, Thomas H. Lee, in honour of the Museum’s 150th anniversary in 2020. The exhibition will feature masterpieces by a wide range of the medium’s greatest practitioners, including Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Ilse Bing, Joseph Cornell, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Andreas Gursky, Helen Levitt, Dora Maar, László Moholy-Nagy, Jack Pierson, Sigmar Polke, Man Ray, Laurie Simmons, Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Cindy Sherman, Andy Warhol, Edward Weston, and Rachel Whiteread.

The exhibition is made possible by Joyce Frank Menschel and the Alfred Stieglitz Society.

Max Hollein, Director of The Met, said, “Ann Tenenbaum brilliantly assembled an outstanding and very personal collection of 20th-century photographs, and this extraordinary gift will bring a hugely important group of works to The Met’s holdings and to the public’s eye. From works by celebrated masters to lesser-known artists, this collection encourages a deeper understanding of the formative years of photography, and significantly enhances our holdings of key works by women, broadening the stories we can tell in our galleries and allowing us to celebrate a whole range of crucial artists at The Met. We are extremely grateful to Ann and Tom for their generosity in making this promised gift to The Met, especially as we celebrate the Museum’s 150th anniversary. It will be an honour to share these remarkable works with our visitors.”

“Early on, Ann recognised the camera as one of the most creative and democratic instruments of contemporary human expression,” said Jeff Rosenheim, Joyce Frank Menschel Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs. “Her collecting journey through the last century of picture-making has been guided by her versatility and open-mindedness, and the result is a collection that is both personal and dynamic.”

The Tenenbaum Collection is particularly notable for its focus on artists’ beginnings, for a sustained interest in the nude, and for the breadth and depth of works by women artists. Paul Strand’s 1916 view from the viaduct confirms his break with the Pictorialist past and establishes the artist’s way forward as a cutting-edge modernist; Walker Evans’s shadow self-portraits from 1927 mark the first inkling of a young writer’s commitment to visual culture; and Cindy Sherman’s intimate nine-part portrait series from 1976 predates her renowned series of “film stills” and confirms her striking ambition and stunning mastery of the medium at the age of 22.

Ms. Tenenbaum commented, “Photographs are mirrors and windows not only onto the world but also into deeply personal experience. Tom and I are proud to support the Museum’s Department of Photographs and thrilled to be able to share our collection with the public.”

The exhibition will feature a diverse range of styles and photographic practices, combining small-scale and large-format works in both black and white and colour. The presentation will integrate early modernist photographs, including superb examples by avant-garde American and European artists, together with work from the postwar period, the 1960s, and the medium’s boom in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and extend up to the present moment.

Photography’s Last Century: The Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection is curated by The Met’s Jeff L. Rosenheim, Joyce Frank Menschel Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs.

Press release from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Joseph Cornell (American, 1903-1972)

Tamara Toumanova (Daguerreotype-Object)

October 1941

Construction with photomechanical reproduction, mirror, rhinestones or sequins, and tinted glass in artist’s frame

Dimensions: 5 1/8 × 4 3/16 in. (13 × 10.6cm)

Frame: 9 3/4 × 8 3/4 × 1 7/8 in. (24.8 × 22.2 × 4.8cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© 2020 The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Joseph Cornell is celebrated for his meticulously constructed, magical shadow boxes that teem with celestial charts, ballet stars, parrots, mirrors, and marbles. Into these tiny theatres he decanted his dreams, obsessions, and unfulfilled desires. Here, his subject is the Russian prima ballerina Tamara Toumanova. Known for her virtuosity and beauty, the dancer captivated Cornell, who met her backstage at the Metropolitan Opera and thereafter saw her as his personal Snow Queen and muse.

Tamara Toumanova (Georgian 2 March 1919 – 29 May 1996) was a Georgian-American prima ballerina and actress. A child of exiles in Paris after the Russian Revolution of 1917, she made her debut at the age of 10 at the children’s ballet of the Paris Opera.

She became known internationally as one of the Baby Ballerinas of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo after being discovered by her fellow émigré, balletmaster and choreographer George Balanchine. She was featured in numerous ballets in Europe. Balanchine featured her in his productions at Ballet Theatre, New York, making her the star of his performances in the United States. While most of Toumanova’s career was dedicated to ballet, she appeared as a ballet dancer in several films, beginning in 1944. She became a naturalised United States citizen in 1943 in Los Angeles, California.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Noto, Sicily, September 5, 1947

September 5, 1947

Gelatin silver print

6 × 6 in. (15.2 × 15.2cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Richard Avedon believed this early street portrait of a young boy in Sicily was the genesis of his long fashion and portrait career. On the occasion of The Met’s groundbreaking 2002 exhibition on the artist, curators Maria Morris Hambourg and Mia Fineman described the work as “a kind of projected self-portrait” in which “a boy stands there, pushing forward to the front of the picture. … He is smiling wildly, ready to race into the future. And there, hovering behind him like a mushroom cloud, is the past in the form of a single, strange tree – a reminder of the horror that split the century into a before and after, a symbol of destruction but also of regeneration.”

Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

Philadelphia

1961

Gelatin silver print

12 1/16 × 17 15/16 in. (30.7 × 45.5cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Philadelphia is the earliest dated photograph from a celebrated series of television sets beaming images into seemingly empty rooms that Lee Friedlander made between 1961 and 1970. The pictures provided a prophetic commentary on the new medium to which Americans had quickly become addicted. Walker Evans published a suite of Friedlander’s TV photographs in Harper’s Bazaar in 1963 and noted: “The pictures on these pages are in effect deft, witty, spanking little poems of hate… Taken out of context as they are here, that baby might be selling skin rash, the careful, good-looking woman might be categorically unselling marriage and the home and total daintiness. Here, then, from an expert-hand, is a pictorial account of what TV-screen light does to rooms and to the things in them.”

Edward Ruscha (American, b. 1937)

Self-Service – Milan, New Mexico

1962

Gelatin silver print

4 11/16 × 4 11/16 in. (11.9 × 11.9cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Ed Ruscha

This intentionally mundane work by the Los Angeles–based painter and printmaker, Ed Ruscha, appears in Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), the first of sixteen landmark photographic books he published between 1963 and 1978. The volume established the artist’s reputation as a conceptual minimalist with a mastery of typography, an appreciation for seriality and documentary practice, and a deadpan sense of humour. Early on, he was influenced by the photographs of Walker Evans. “What I was after,” said Ruscha, “was no-style or a non-statement with a no-style.”

Nan Goldin (American, b. 1953)

Ivy in the Boston Garden: Back

1973

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6cm)

Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

© Nan Goldin

While still in college, Nan Goldin spent two years recording performers at the Other Side, a Boston drag bar that hosted beauty pageants on Monday nights. This black-and-white study of Ivy, Goldin’s friend from the bar, walking alone through the Boston Common is one of the artist’s earliest photographs. The portrait evokes the glamorous world of fashion photography and hints at its loneliness. In all of her photographs, Goldin explores the natural twinning of fantasy and reality; it is the source of their pathos and rhythmic emotional beat. A decade after this elegiac photograph, she conceived the first iteration of her 1985 breakthrough colour series, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, which was presented as an ever-changing visual diary using a slide projector and synchronised music.

Laurie Simmons (American, b. 1949)

Woman/Interior I

1976

Gelatin silver print

5 3/4 × 7 1/2 in. (14.6 × 19.1cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© 2020 Laurie Simmons

Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York

Laurie Simmons began her career in 1976 with a series of enchantingly melancholic photographs of toy dolls set up in her apartment. The accessible mix of desire and anxiety in these early photographs resonates with, and provides a useful counterpoint to, Cindy Sherman’s contemporaneous “film stills” such as Untitled Film Still #48 seen nearby. Simmons and Sherman were foundational members of one of the most vibrant and productive communities of artists to emerge in the late twentieth century. Although they did not all see themselves as feminists or even as a unified group of “women artists,” each used the camera to examine the prescribed roles of women, especially in the workplace, and in advertising, politics, literature, and film.

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled Film Still #48

1979

Gelatin silver print

6 15/16 × 9 3/8 in. (17.6 × 23.8cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A lone woman on an empty highway peers around the corner of a rocky outcrop. She waits and waits below the dramatic sky. Is it fear or self-reliance that challenges the unnamed traveler? Does she dread the future, the past, or just the present? So thorough and sophisticated is Cindy Sherman’s capacity for filmic detail and nuance that many viewers (encouraged by the titles) mistakenly believe that the photographs in the series are reenactments of films. Rather, they are an unsettling yet deeply satisfying synthesis of film and narrative painting, a shrewdly composed remaking not of the “real” world but of the mediated landscape.

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Coral Sea

1983

Platinum print

23 1/8 × 19 1/2 in. (58.8 × 49.5cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This study of a Midway-class aircraft carrier shows a massive warship not actually floating on the ocean’s surface but seemingly sunken beneath it. The rather minimal photograph is among the rarest and least representative works by Robert Mapplethorpe, who is known mostly for his uncompromising sexual portraits and saturated flower studies, as well as for his mastery of the photographic print tradition. Here, he chose platinum materials to explore the subtle beauty of the medium’s extended mid-grey tones. By rendering prints using the more tactile platinum process, Mapplethorpe hoped to transcend the medium; as he said it is “no longer a photograph first, [but] firstly a statement that happens to be a photograph.”

Robert Gober (American, b. 1954)

Untitled (detail)

1988

Gelatin silver print

6 1/2 × 9 7/16 in. (16.5 × 24cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Robert Gober, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Although Robert Gober is not often thought of as a photographer, his conceptual practice has long depended on a camera. From the time of his first solo show in 1984 Gober has documented temporal projects in hundreds of photographs, and today many of his site-specific installations survive as images. His photography resists classification, seeming to split the difference between archival record and independent artwork. Here, across three frames, flimsy white dresses advance and recede into a deserted wood. Gober sewed the garments from fabric printed by the painter Christopher Wool in the course of a related collaboration. Seen together, Gober’s staged photographs record an ephemeral intervention in an unwelcoming, almost fairy-tale landscape.

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Imperial Montreal

1995

Gelatin silver print

20 × 24 in. (50.8 × 61cm)

Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A self-taught expert on the history of photography and Zen Buddhism, Hiroshi Sugimoto posed a question to himself in 1976: what would be the effect on a single sheet of film if it was exposed to all 172,800 photographic frames in a feature-length movie? To visualise the answer, he hid a large-format camera in the last row of seats at St. Marks Cinema in Manhattan’s East Village and opened the shutter when the film started; an hour and a half later, when the movie ended, he closed it. The series (now forty years in the making) of ethereal photographs of darkened rooms filled with gleaming white screens presents a perfect example of yin and yang, the classic concept of opposites in ancient Chinese philosophy.

Andreas Gursky (German, b. 1955)

Prada II

1996

Chromogenic print

65 in. × 10 ft. 4 13/16 in. (165.1 × 317cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Andreas Gursky / Courtesy Sprüth Magers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

To produce this quasi-architectural study of a barren luxury store display, Andreas Gursky used newly available software both to artificially stretch the underlying chemical image and to digitally generate the billboard-size print. At ten feet wide, the work is a Frankensteinian glimpse of what would transform the medium of photography over the next two decades. Gursky seems to have fully understood the Pandora’s box he had opened by using digital tools to manipulate his pictures, which put into question their essential realism: “I have a weakness for paradox. For me… the photogenic allows a picture to develop a life of its own, on a two-dimensional surface, which doesn’t exactly reflect the real object.”

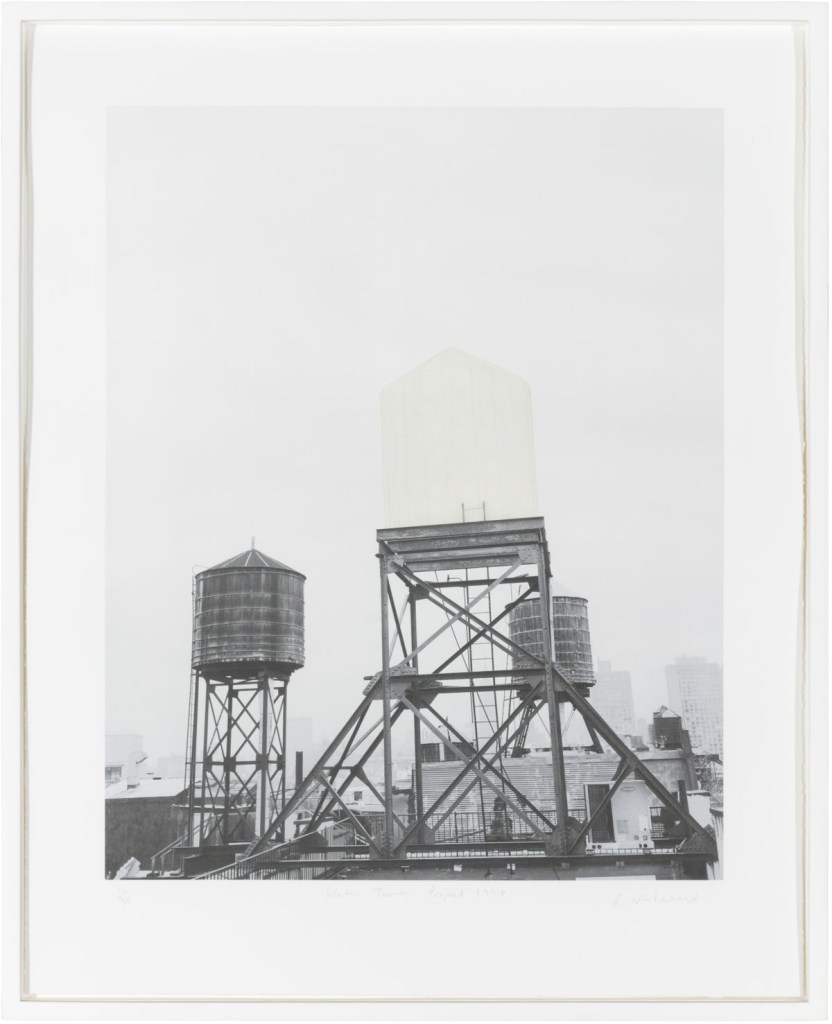

Rachel Whiteread (English, b. 1963)

Watertower Project

1998

Screenprint with applied acrylic resin and graphite

20 in. × 15 15/16 in. (50.8 × 40.5cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Rachel Whiteread

How might one solidify water other than by freezing it? In New York in June 1998, a translucent 12 x 9-foot, 4 1/2-ton sculpture created by Rachel Whiteread landed like a UFO atop a roof at the corner of West Broadway and Grand Street. The artist described the work – a resin cast of the interior of one of the city’s landmark wooden water tanks – as a “jewel in the Manhattan skyline.” This print is a poetic trace of the massive sculpture, which was commissioned by the Public Art Fund. The original work of art holds and refracts light just like the acrylic resin applied to the surface of this print.

Gregory Crewdson (American, b. 1962)

Untitled

2005

Chromogenic print

57 × 88 in. (144.8 × 223.5cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gregory Crewdson describes his highly scripted photographs as single-frame movies; to produce them, he engages teams of riggers, grips, lighting specialists, and actors. The story lines in most of his photographs centre on suburban anxiety, disorientation, fear, loss, and longing, but the final meaning almost always remains elusive, the narrative unfinished. In this photograph something terrible has happened, is happening, and will likely happen again. A woman in a nightgown sits in crisis on the edge of her bed with the remains of a rosebush on the sheets beside her. The journey from the garden was not an easy one, as evidenced by the trail of petals, thorns, and dirt. Even so, the protagonist cradles the plant’s roots with tender regard.

Catherine Opie (American, b. 1961)

Football Landscape #8 (Crenshaw vs. Jefferson, Los Angeles, CA)

2007

Chromogenic print

48 × 64 in. (121.9 × 162.6cm)

Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

High school football is not a conventional subject for contemporary artists in any medium. Neither are freeways nor surfers, each of which are series by the artist Catherine Opie. A professor of photography at the University of California, Los Angeles, Opie spent several years traveling across the United States making close-up portraits of adolescent gladiators as well as seductive, large-scale landscape views of the game itself. Poignant studies of group behaviour and American masculinity on the cusp of adulthood, the photographs can be seen as an extension of the artist’s diverse body of work related to gender performance in the queer communities in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

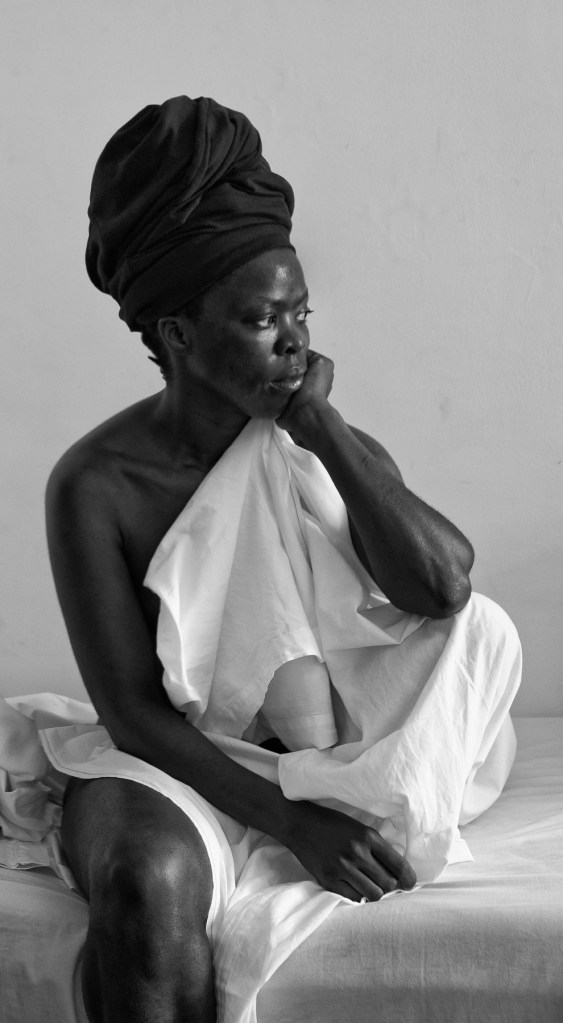

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Vukani II (Paris)

2014

Gelatin silver print

23 1/2 in. × 13 in. (59.7 × 33cm)

Promised Gift of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The South African photographer Zanele Muholi is a self-described visual activist and cultural archivist. In the artist’s hands, the camera is a potent tool of self-representation and self-definition for communities at risk of violence. Muholi has chosen the nearly archaic black-and-white process for most of their portraits “to create a sense of timelessness – a sense that we’ve been here before, but we’re looking at human beings who have never before had an opportunity to be seen.” Challenging the immateriality of our digital age, Muholi has restated the importance of the physical print and connected their work to that of their progenitors. In this recent self-portrait, Muholi sits on a bed, sharing a quiet moment of reflection and self-observation. The title, in the artist’s native Zulu, translates loosely as “wake up.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Thursday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Closed Wednesday

![Adolph de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1949) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912 Adolph de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1949) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-dance-study-web.jpg)

![Morton Schamberg (American, 1881–1918) '[View of Rooftops]' 1917 Morton Schamberg (American, 1881–1918) '[View of Rooftops]' 1917](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/schamberg-view-of-rooftops.jpg?w=815)

You must be logged in to post a comment.